Abstract

The effect of habituation at reduced water activity (aw) on heat tolerance of Salmonella spp. was investigated. Stationary-phase cells were exposed to aw 0.95 in broths containing glucose-fructose, sodium chloride, or glycerol at 21°C for up to a week prior to heat challenge at 54°C. In addition, the effects of different aws and heat challenge temperatures were investigated. Habituation at aw 0.95 resulted in increased heat tolerance at 54°C with all solutes tested. The extent of the increase and the optimal habituation time depended on the solute used. Exposure to broths containing glucose-fructose (aw 0.95) for 12 h resulted in maximal heat tolerance, with more than a fourfold increase in D54 values. Cells held for more than 72 h in these conditions, however, became as heat sensitive as nonhabituated populations. Habituation in the presence of sodium chloride or glycerol gave rise to less pronounced but still significant increases in heat tolerance at 54°C, and a shorter incubation time was required to maximize tolerance. The increase in heat tolerance following habituation in broths containing glucose-fructose (aw 0.95) was RpoS independent. The presence of chloramphenicol or rifampin during habituation and inactivation did not affect the extent of heat tolerance achieved, suggesting that de novo protein synthesis was probably not necessary. These data highlight the importance of cell prehistory prior to heat inactivation and may have implications for food manufacturers using low-aw ingredients.

The genus Salmonella includes important international food-borne pathogens and has been reported in approximately 30,000 cases of food-borne illness each year in England and Wales since 1990, with a decline in the number of cases over the last 2 years (4). Reported cases are likely to represent only a fraction of the true numbers, and a recent study by the Public Health Laboratory Service (PHLS) in England has indicated that infectious intestinal disease is often underreported (43). This study indicated that, for every case reported to PHLS Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre, there are 3.2 cases of Salmonella infection in the community. Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium definitive type (DT) 104 is the second most prevalent serotype isolated from human cases after S. enterica serovar Enteritidis phage type (PT) 4 (PHLS Communicable Disease Surveillance Centre, unpublished data for 1990–94; 16). DT104 is of particular concern due to the severity of human disease caused, its multiple-drug resistance, and its extensive animal reservoirs (42), and PT4 is clearly of interest due to the large numbers of cases associated with it. These and other Salmonella serotypes have caused food poisoning outbreaks associated with low-water-activity (aw) foods (3, 15, 19, 27, 39). The processing of certain foods containing low-aw ingredients is known to involve heat treatments, and it is in such situations that a knowledge of the effect of prior exposure to low aw on the heat tolerance of Salmonella spp. is required.

Measured heat tolerance is known to depend on the conditions during heat inactivation and cell recovery (35, 40). The prehistory of Salmonella spp. prior to challenge at high temperature has also proved critical to subsequent survival data. Factors such as growth temperature and age of culture (12), broth type (17), pH of incubation conditions (17, 23), and whether cells are washed (17) are all important. One such factor that may also be important is the incubation of bacteria in conditions where water is limited prior to heat challenge.

Although it is well known that aw during heat inactivation has a profound effect on heat tolerance (40), little is known about the effect of exposure to non-growth-permitting low aw (e.g., <0.96 for Salmonella spp.) prior to heat challenge. Early work showed that the heat tolerance of Escherichia coli increased when cells were incubated in the presence of 50% (wt/vol) sucrose (14). In Listeria spp., habituation in broth with added NaCl (9% [wt/vol], corresponding to aw 0.94) led to increased heat tolerance in low-aw broths, and this was also demonstrated in a food system (24). It has also been shown that air-dried Salmonella cells, in which aw is lowered without the use of solutes, become more heat tolerant (28). Thus, Salmonella spp. contaminating a low-aw food ingredient (e.g., spices) may be more heat tolerant than expected.

In this study, the effect of habituation of Salmonella cells at low aw on their ability to survive a subsequent combination of lethal heat and low aw was investigated. Habituation over an extended time period was chosen to simulate real situations, such as the contamination of a food ingredient prior to heat processing. This study examines habituation at low aw prior to heat challenge in a systematic manner, investigating the effect of habituation time and solute. This is believed to be the first publication to report that the time taken for Salmonella to reach optimal habituation at a defined aw varies with respect to solute and to demonstrate that this habituation is likely to be independent of de novo protein synthesis and RpoS expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Salmonella strains and preparation of cultures.

DT104 strain 30 (44), PT4 strain LA5, and PT4 strain EAV54 were used in this study. Strain 30 was isolated from cattle feces. LA5 is from a natural chicken infection (1). Strain EAV54 is an otherwise isogenic rpoS mutant of LA5 (1), kindly provided by M. J. Woodward, Veterinary Laboratory Agency, Weybridge, United Kingdom. Salmonella strains were recovered from storage at −20°C on Protect beads (Mast Diagnostics). A bead was streaked onto 5% horse blood agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. Stationary-phase cultures were prepared by inoculation of 9 ml of tryptone soya broth (TSB; Oxoid, Hampshire, United Kingdom) and incubation at 37°C. After 3 h, 1 μl of the initial broth was transferred into 9 ml of TSB before incubation at 37°C for 15 h by which time the cultures had reached early stationary phase (22).

Preparation of reduced-aw broths.

AnalaR grades of glucose, fructose, NaCl, and glycerol (BDH, Leicestershire, United Kingdom) were used as humectants to produce reduced-aw TSB. TSB base was supplemented with glucose-fructose (in equal portions), NaCl, or glycerol, and deionized water was added such that the final aw would be lower than the required value. The broths were steamed for 30 min to avoid caramelization. The pH of the broths was adjusted to pH 6.5 ± 0.2, using HCl and NaOH, with pH measured with a pH meter (PHM93; Radiometer, Copenhagen, Denmark). The broths were then adjusted using TSB (also adjusted to pH 6.5 using HCl and NaOH) to give the required aw values (0.91, 0.93, 0.95, 0.97, and 0.99) ± 0.003. An aw of 0.95 is equivalent to approximately 32% (wt/vol) glucose-fructose, 8% (wt/vol) NaCl, or 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. The aw of the broths was measured using an Aqualab CX-3T (Labcell, Hampshire, United Kingdom) water activity meter at 25°C. The water activity meter works on the “dew point” principle, involving the detection of condensation on a mirror during cooling-heating cycles. An aliquot of each batch of broth was incubated at 37°C to ensure that no viable microorganisms remained.

Measurement of heat tolerance.

One hundred and fifty microliters of a stationary-phase Salmonella culture was inoculated into 15 ml of TSB, with or without added humectant. This gave an initial cell density of approximately 107 CFU ml−1. These broths were then incubated under the conditions described below prior to heat challenge. The heat challenge was performed by injecting cultures into a submerged heating coil (8) held at either 54 or 60°C (± 0.1°C) measured with a mercury thermometer (Zeal, London, United Kingdom). At predetermined time intervals, 0.2 ml of the culture was ejected from the coil and an immediate 10-fold dilution was made in 1.8 ml of maximum recovery diluent to reduce the broth temperature and minimize further cell death. Further 10-fold dilutions were made in maximum recovery diluent as appropriate. Viable counts were performed using the method of Miles and Misra (31) with recovery on horse blood agar and incubation for 48 h at 37°C.

Habituation of DT104 at low aw.

An aw of 0.95 was chosen for the majority of habituation studies, since that was the lowest aw at which habituation can proceed for 100 or more h without significant cell death or growth (29). Cultures of DT104 strain 30 were prepared as above and incubated at 21°C in TSB at aw 0.95 for up to 168 h prior to heat challenge at 54 or 60°C. For TSB with glucose-fructose, the pH values were measured during the habituation. To investigate other aws, DT104 strain 30 was inoculated into TSB containing glucose-fructose at aw 0.91, 0.93, 0.95, and 0.97, and it was habituated for 48 h at 21°C prior to heat challenge at 54°C in these media. Control cultures were heat challenged at the appropriate aw without habituation or habituated for 48 h in broth with no added solute (aw 0.99).

Involvement of protein synthesis during habituation of DT104 at aw 0.95.

Cultures were prepared as above using DT104 strain 30 and were heat challenged at 54°C in triplicate after habituation for 48 h at 21°C in TSB containing glucose-fructose at aw 0.95, in the presence of 100 μg of chloramphenicol per ml or 15 μg of rifampin per ml to inhibit protein synthesis. This strain of DT104 had previously been found to be sensitive to both antibiotics (data not shown). The control cultures were habituated in TSB at aw 0.95 in the absence of antibiotic.

Habituation of PT4 at aw 0.95.

PT4 strain LA5 was inoculated into TSB containing glucose-fructose at aw 0.95. The cells were heat challenged at 54°C before and after habituation for 48 h at aw 0.95 (glucose-fructose) at 21°C.

Involvement of RpoS expression during habituation of PT4 at aw 0.95.

The PT4 rpoS mutant strain EAV54 was inoculated into TSB at aw 0.95 (glucose-fructose) and heat challenged at 54°C before and after habituation for 48 h in this medium at 21°C.

Data analysis.

For each habituation time and solute combination, heat challenge was carried out at least in triplicate and for some as many as six times. Values for decimal reduction time (D values [26; time required to kill one log concentration of bacteria]) were calculated to summarize much of the data. Data analysis was performed with Microsoft Excel 97. Statistical significance was calculated using a t test on two samples, assuming equal variance.

RESULTS

Habituation of DT104 at low aw prior to heat challenge at 54 or 60°C.

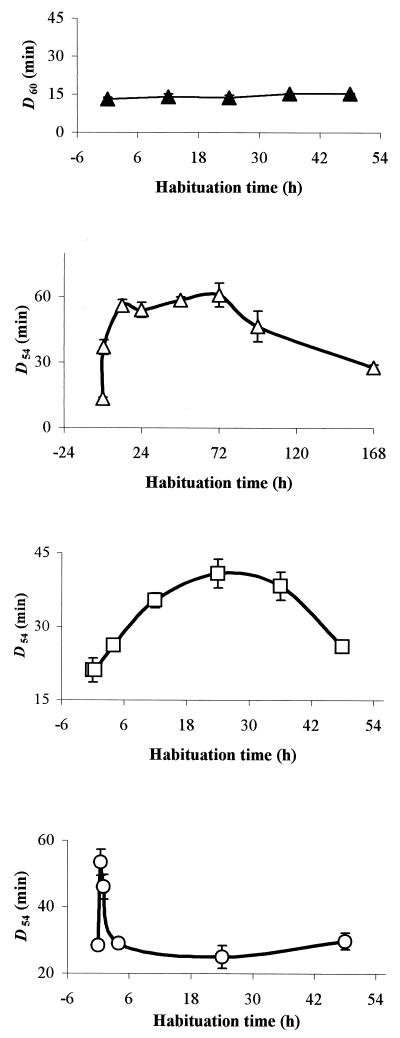

Habituation at aw 0.95 prior to heat challenge resulted in increased heat tolerance at 54°C. The extent of this increase depended on the humectant used and the incubation time. After habituation of cells in TSB containing glucose-fructose (aw 0.95), maximal heat tolerance (>4-fold increase in D54 [the time necessary to kill one log concentration of bacteria at 54°C]) was observed after approximately 12 h, although a significant increase was seen after only 30 min (P = 0.002) (Fig. 1). The pH of cultures exposed to TSB containing glucose-fructose (aw 0.95) did not decrease until after 100 h (data not shown), suggesting that the increased heat tolerance was not a result of acid-induced cross-protection to heat. When sodium chloride was the humectant, maximal heat tolerance was observed after approximately 24 h, and the increase in heat tolerance (∼2-fold increase in D54) was significantly lower than with glucose-fructose (P = 0.003). When glycerol was the humectant, the measured increase in heat tolerance was similar to that seen with NaCl but occurred after only 30 min (Fig. 1). After maximal heat tolerance had been achieved, further incubation in low-aw media caused a decline in tolerance for all humectants examined (Fig. 1). In contrast to the data obtained at 54°C, habituation in TSB containing glucose-fructose (aw 0.95) had no significant effect on measured death rates at 60°C (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Inactivation rates for DT104 strain 30 at 54°C (open symbols) or 60°C (closed symbols), following habituation at aw 0.95 for different durations prior to heat challenge. Humectants used to reduce aw were glucose-fructose (triangles), NaCl (squares), and glycerol (circles).

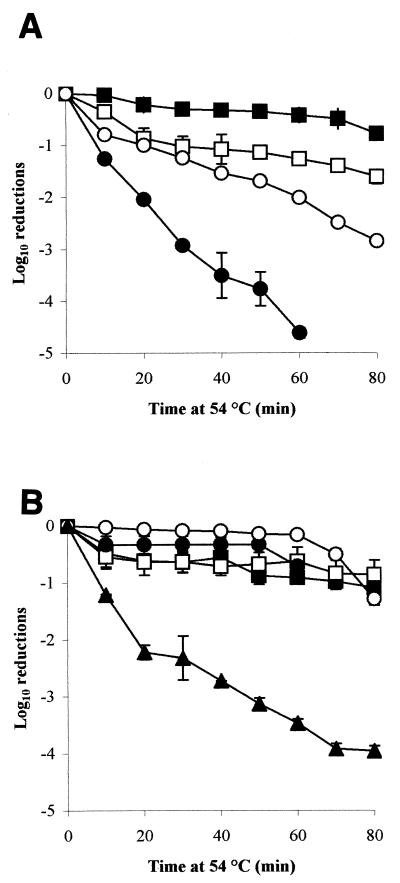

Media in the aw range 0.91 through 0.99 were examined to see whether culture under these conditions brought about similar increases in heat tolerance compared to that seen following habituation at aw 0.95 (Fig. 1). Cells were heat challenged in the medium in which they were habituated. These experiments revealed an interesting relationship between aw and heat tolerance. When cells were challenged in a medium without prior habituation at reduced aw, heat tolerance was greatest at aw 0.91 and lowest at aw 0.95 while an intermediate level of tolerance was observed at aw 0.93 and 0.97 (Fig. 2A). When cells were habituated in the low-aw media for 48 h prior to heat challenge, a different pattern emerged. Salmonella cells habituated at aw 0.91, 0.93, 0.95, and 0.97 exhibited similar heat tolerance, but control cultures incubated for 48 h at aw 0.99 prior to heat challenge were far more heat sensitive (Fig. 2B). The cells that were originally most heat sensitive (i.e., those at aw 0.95) therefore showed the greatest increase in heat tolerance.

FIG. 2.

The rate of inactivation of DT104 strain 30 at 54°C, following habituation at aw 0.91 (closed square), 0.93 (open square), 0.95 (closed circle), 0.97 (open circle), or 0.99 (closed triangle), achieved using glucose-fructose for 0 h (A) or 48 h (B).

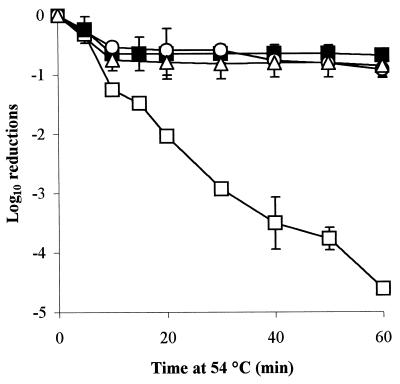

Protein synthesis and low-aw-induced heat tolerance at 54°C in DT104.

Inhibition of protein synthesis using either chloramphenicol or rifampin had no significant effect on the induction of heat tolerance by habituation in TSB containing glucose-fructose (aw 0.95) when the challenge temperature was 54°C (Fig. 3), despite being present throughout habituation and inactivation.

FIG. 3.

The rate of inactivation of DT104 strain 30 at 54°C, following habituation at aw 0.95 (glucose-fructose) for 48 h in the presence of protein synthesis inhibitors, chloramphenicol (open circles), and rifampin (open triangles). Controls were habituated with no protein synthesis inhibitors (closed squares) or with no habituation (open squares).

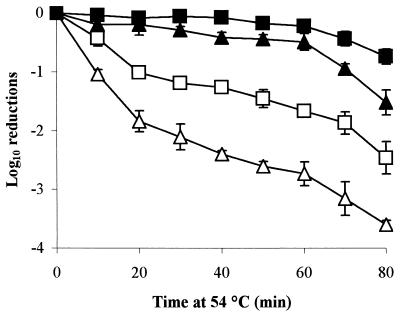

Habituation of PT4 at aw 0.95 prior to heat challenge at 54°C and involvement of RpoS expression.

Habituation of PT4 strain LA5 at aw 0.95 results in a clear increase in heat tolerance at 54°C; thus the effect of low-aw habituation is not limited to DT104 strain 30 (Fig. 4). RpoS expression was not required for habituation to occur, since the rpoS mutant, EAV54, showed significantly enhanced heat tolerance after 48 h of incubation at aw 0.95 (P = 0.017) (Fig. 4). This enhanced heat tolerance was similar to the increase seen in LA5, even though rpoS mutants are inherently less heat tolerant (30).

FIG. 4.

The rate of inactivation of PT4 strain LA5 (squares) and rpoS mutant EAV54 (triangles) at 54°C, following habituation for 48 h at aw 0.95 (glucose-fructose [closed symbols]) or with no habituation (open symbols).

DISCUSSION

It is well documented that transient conditioning to a sublethal stress (habituation) can induce tolerance to a more extreme stress and that habituation to one type of stress may cross-protect to others. In this investigation, we have demonstrated that habituation to low aw at 21°C can increase the heat tolerance in DT104 and PT4 and that the extent of heat protection afforded is dependent on the humectant used, habituation time, and challenge temperature. The effects of the three humectants were very different at the same aw; thus it would appear that the cells are not reacting to aw per se. Following habituation for only 30 min in TSB containing glucose-fructose (aw 0.95), a significant increase in heat tolerance at 54°C was observed, and after 12 h, a >4-fold increase in the D54 value was seen. In contrast, habituation with NaCl or glycerol at this aw had less effect on heat tolerance (with D54 values increasing only twofold). The increase in heat tolerance when glycerol is the humectant is rapid but very short lived. Habituation with NaCl caused a slower rise in heat tolerance than either glucose-fructose or glycerol, with tolerance being maximized after approximately 24 h. In all cases, after maximal heat tolerance had been achieved, further incubation at low aw caused a decline in D54 values.

It has previously been reported that at the same aw, the heat tolerance of Salmonella spp. differs according to the solute used (17). In our study, it appeared that the extent of heat tolerance at 54°C resulting from habituation at low aw is also affected by the solute. Glycerol is rapidly permeable (18), entering the cell very quickly, and accordingly the optimal habituation time is very short. Glycerol does not cause plasmolysis of the cell to the extent that sugars and NaCl can, and this could be a reason for its transient protective effect against heat (18). Sodium chloride is ionic and consequently disruptive to cellular activities (11, 18). The decline in heat tolerance after prolonged incubation at low aw may relate to energy expenditure required in maintaining homeostasis (11, 25, 32). We have excluded the possibility that cells in broth may enter log phase after a certain time and thus become more sensitive to heat, since there is no significant increase in cell numbers in the broths until 168 h, when the decrease in heat resistance has already occurred.

In the current study we have grown Salmonella spp. in a standard microbiological broth (aw 0.99) and then habituated the stationary-phase cells at non-growth-permitting low aw. Some very early investigations indicated that heat resistance of Escherichia coli increased when that bacterium was incubated even for a short time in 50% sucrose, but after 7 h a return to normal resistance was observed (14). This pattern is consistent with our findings, although the time taken to return to normal resistance is shorter than predicted from our data, possibly due to different effects exerted by different sugars. In Listeria spp., habituation in broth with added NaCl (9% [wt/vol], corresponding to an aw of 0.94) led to increased survival in low-aw broths at 60°C, and this was also demonstrated in a food system (24). This is a similar pattern to that seen in this study with Salmonella spp. at 54°C. Cells dried for 48 h showed increased resistance, but no further increase was seen with longer periods of dehydration (28). Therefore, the habituation effect observed in this study may apply to air-dried cells in addition to cells in a liquid where available water is limited by the addition of a solute.

Other studies have examined the heat tolerance of bacteria following prior growth at less extreme levels of reduced aw (0.96 through 0.98). Even at these growth-permitting aws (reduced using various solutes), there was usually some effect on heat tolerance (7, 9, 17), and when an increase was not observed, this could be explained in terms of the experimental protocol.

The lack of effect of habituation on heat tolerance at 60°C in this study may reflect different targets for cell death at the higher temperature compared with 54°C. Previous work demonstrated that neither adaptation to high sugar concentrations or growth at an elevated temperature resulted in increased heat tolerance at 65 or 58°C, respectively (10, 45).

During habituation and heat challenge at aws 0.91 through 0.99, cells cultured at aw 0.95 developed from being the most heat-sensitive population to among the most heat-resistant population. It has been reported that solutes can cause a decrease in heat resistance when present at relatively low levels, whereas at high concentration they may afford considerable protection to heat (33). Baird-Parker et al. (5) reported a decrease in heat resistance for certain Salmonella strains at about aw 0.94, but below this, the heat resistance increased. These findings were reflected in this study in nonhabituated controls at aws 0.91 through 0.97 (Fig. 2). After habituation, the cultures at aw 0.91 through 0.97 all exhibited similar heat tolerance.

The experiments with the rpoS mutant indicated that RpoS expression is not required for the observed increase in heat tolerance following habituation in glucose-fructose. Despite evidence that proteins produced at low aw can protect against heat challenge (6), habituation occurred in the presence of chloramphenicol and rifampin. Thus, RpoS expression and de novo protein synthesis are unlikely to have a major role in low-aw-induced heat tolerance, unless the required proteins can be synthesized in the presence of ribosome inhibitors (as has been reported with certain other proteins [13, 36]). It may be that existing cell proteins can modify their structure and function when environmental conditions change, as demonstrated for certain heat shock proteins (37, 38). The solutes used in this study are also likely to produce substantial osmotic stress, leading to the accumulation of compatible solutes. Such accumulation may be independent of protein synthesis and can result in increased heat tolerance (20). Finally, targets for heat inactivation may be directly protected by the solutes, possibly in a temperature-dependent manner.

This work has possible important implications for the design of experimental protocols and for food manufacturing and processing. In earlier studies, a low-aw habituation stage was built with the same duration for each solute (34). The new results presented here indicate that an optimal habituation time for one solute may give no benefit for another and that the habituation step should be tailored to the solute type. In addition, exposure of Salmonella spp. to low aw could reduce the effectiveness of any subsequent heat processing. This will be of particular concern to food manufacturers whose processing conditions involve a heat treatment step and, in particular, when ingredients that are dry or have a high solute concentration are to be processed.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge funding from Nabisco, Inc., and the Public Health Laboratory Service.

We thank R. Rowbury for helpful discussions and M. J. Woodward for the rpoS mutant strain used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen-Vercoe E, Dibb-Fuller M, Thorns C J, Woodward M J. SEF17 fimbriae are essential for the convoluted colonial morphology of Salmonella enteritidis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;153:33–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Angeles González-Hevia M, Flor Gutierrez M, Carmen Mendoza M. Diagnosis by a combination of typing methods of a Salmonella typhimurium outbreak associated with cured ham. J Food Prot. 1996;59:426–428. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.4.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anonymous. An outbreak of Salmonella agona due to contaminated snacks. Commun Dis Rep CDR Wkly. 1995;5:29. , 32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous. The rise and fall of salmonella? Commun Dis Rep Wkly. 1999;9:29. , 32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baird-Parker A C, Boothroyd M, Jones E. The effect of water activity on the heat resistance of heat sensitive and heat resistant strains of salmonellae. J Appl Bacteriol. 1970;33:515–522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1970.tb02228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianchi A A, Baneyx F. Hyperosmotic shock induces the sigma32 and sigmaE stress regulons of Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:1029–1038. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calhoun C L, Frazier W C. Effect of available water on thermal resistance of three nonsporeforming species of bacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1966;14:416–420. doi: 10.1128/am.14.3.416-420.1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole M B, Jones M W. A submerged-coil heating apparatus for investigating thermal inactivation of micro-organisms. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1990;11:233–235. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotterill O J, Glauert J. Thermal resistance of salmonellae in egg yolk products containing sugar or salt. Poult Sci. 1969;48:1156–1166. doi: 10.3382/ps.0481156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corry J E L. The effect of sugars and polyols on the heat resistance of salmonellae. J Appl Bacteriol. 1974;37:31–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1974.tb00412.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Csonka L N, Epstein W. Osmoregulation. In: Neidhardt F C, et al., editors. Escherichia coli and Salmonella: cellular and molecular biology. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1996. pp. 1210–1223. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dega C A, Goepfert J M, Amundson C H. Heat resistance of salmonellae in concentrated milk. Appl Microbiol. 1972;23:415–420. doi: 10.1128/am.23.2.415-420.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Etchegaray J P, Inouye M. CspA, CspB, and CspG, major cold shock proteins of Escherichia coli, are induced at low temperature under conditions that completely block protein synthesis. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1827–1830. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.6.1827-1830.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fay A C. The effect of hypertonic sugar solutions on the thermal resistance of bacteria. J Agric Res. 1934;48:453–468. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gill O N, Sockett P N, Bartlett C L R, Vaile M S B. Outbreak of Salmonella napoli infection caused by contaminated chocolate bars. Lancet. 1983;i:574–577. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92822-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynn M K, Bopp C, Dewitt W, Dabney P, Mokhtar M, Angulo F J. Emergence of multidrug-resistant Salmonella enterica serotype typhimurium DT104 infections in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1333–1338. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805073381901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goepfert J M, Iskander I K, Amundson C H. Relation of the heat resistance of salmonellae to the water activity of the environment. Appl Microbiol. 1970;19:429–433. doi: 10.1128/am.19.3.429-433.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gould G W. Mechanisms of action of food preservation procedures. Elsevier Science Publishers Ltd.; 1989. Drying, raised osmotic pressure and low water activity; pp. 97–117. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenwood M H, Hooper W L. Chocolate bars contaminated with Salmonella napoli: an infectivity study. Br Med J. 1983;286:1394. doi: 10.1136/bmj.286.6375.1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hengge-Aronis R, Klein W, Lange R, Rimmele M, Boos W. Trehalose synthesis genes are controlled by the putative sigma factor encoded by rpoS and are involved in stationary-phase thermotolerance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7918–7924. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.24.7918-7924.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Humphrey T J. Heat resistance in Salmonella enteritidis PT4: the influence of storage temperatures before heating. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;69:493–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Humphrey T J, Slater E, McAlpine K, Rowbury R J, Gilbert R J. Salmonella enteritidis phage type 4 isolates more tolerant of heat, acid, or hydrogen peroxide also survive longer on surfaces. Appl Env Microbiol. 1995;61:3161–3164. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.8.3161-3164.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Humphrey T J, Richardson N P, Gawler A H L, Allen M J. Heat resistance of Salmonella enteritidis PT4: the influence of prior exposure to alkaline conditions. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1991;12:258–260. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jørgensen F, Stephens P J, Knochel S. The effect of osmotic shock and subsequent adaptation on the thermotolerance and cell morphology of Listeria monocytogenes. J Appl Bacteriol. 1995;79:274–281. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joshi A K, Ahmed S, Ames G F. Energy coupling in bacterial periplasmic transport systems. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:2126–2133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katzin L I, Sandholzer L A, Strong M E. Application of the decimal reduction time principle to a study of the resistance of coliform bacteria to pasteurization. J Bacteriol. 1943;45:265–269. doi: 10.1128/jb.45.3.265-272.1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Killalea D, Ward L R, Roberts D, de Louvois J, Sufi F, Stuart J M, Wall P G, Susman M, Schweiger M, Sanderson P J, Fisher I S T, Mead P S, Gill O N, Bartlett C L R, Rowe B. International epidemiological and microbiological study of outbreak of Salmonella agona infection from a ready to eat savoury snack. I. England and Wales and the United States. Br Med J. 1996;313:1105–1107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7065.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kirby R M, Davies R. Survival of dehydrated cells of Salmonella typhimurium LT2 at high temperatures. J Appl Bacteriol. 1990;68:241–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1990.tb02570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mattick K L, Jørgensen F, Legan J D, Cole M B, Porter J, Lappin-Scott H M, Humphrey T J. Survival and filamentation of Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis PT4 and Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium DT104 at low water activity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1274–1279. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1274-1279.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCann M P, Kidwell J P, Matin A. The putative ς factor KatF has a central role in development of starvation-mediated general resistance in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:4188–4194. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.13.4188-4194.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miles A A, Misra S S. The estimation of bactericidal power of blood. J Hyg. 1938;38:732–749. doi: 10.1017/s002217240001158x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mimmack M L, Gallagher M P, Pearce S R, Hyde S C, Booth I R, Higgins C F. Energy coupling to periplasmic binding protein-dependent transport systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8257–8261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mossel D A A, Corry J E L, Struijk C B, Baird R M. Essentials for the microbiology of foods. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1995. Factors affecting the fate and activities of microorganisms in foods; pp. 63–110. [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Donovan-Vaughan C E, Upton M E. Proceedings of the Seventeenth International Conference of the International Committee on Food Microbiology and Hygiene, Veldhoven, The Netherlands. Foundation Food Micro '99. 1999. The combined effect of reduced water activity (Aw) and heat on the survival of Salmonella typhimurium; p. 85. Zeist, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riemann H. Effect of water activity on the heat resistance of Salmonella in “dry” materials. Appl Microbiol. 1968;16:1621–1622. doi: 10.1128/am.16.10.1621-1622.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowbury R J, Goodson M. An extracellular acid stress-sensing protein needed for acid tolerance induction in Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:49–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sherman M Y, Goldberg A L. Heat shock in Escherichia coli alters the protein-binding properties of the chaperonin GroEL by inducing its phosphorylation. Nature. 1992;357:167–169. doi: 10.1038/357167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sherman M Y, Goldberg A L. Heat shock of Escherichia coli increases binding of DnaK (the hsp70 homolog) to polypeptides by promoting its phosphorylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8648–8652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shohat T, Green M S, Merom D, Gill O N, Reisfeld A, Matas A, Blau D, Gal N, Slater P E. International epidemiological and microbiological study of an outbreak of Salmonella agona infection from a ready to eat savoury snack. II. Israel. Br Med J. 1996;313:1107–1109. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7065.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sumner S S, Sandros T M, Harmon M C, Scott V N, Bernard D T. Heat resistance of Salmonella typhimurium and Listeria monocytogenes in sucrose solutions of various water activities. J Food Sci. 1991;56:1741–1743. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trollmo C, Andre L, Blomberg A, Adler L. Physiological overlap between osmotolerance and thermotolerance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1988;56:321–326. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wall P G, Morgan D, Lamden K, Ryan M, Griffen M, Threlfall E J, Ward L R, Rowe B. A case control study of infection with an epidemic strain of multiresistant Salmonella typhimurium DT104 in England and Wales. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev. 1994;4:R130–R135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wheeler J G, Cowden J M, Sethi D, Wall P G, Rodrigues L C, Tompkins D S, et al. Study of infectious intestinal disease in England: rates in the community, presenting to GPs, and reported to national surveillance. Br Med J. 1999;318:1046–1050. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7190.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Williams A, Davies A C, Wilson J, Marsh P D, Leach S, Humphrey T J. Contamination of the contents of intact eggs by Salmonella typhimurium DT104. Vet Rec. 1998;143:562–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xavier I J, Ingman S C. Increased D-values for Salmonella enteritidis following heat shock. J Food Prot. 1997;60:181–184. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-60.2.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]