Abstract

Background:

The contribution of the novel biomarkers, HBV RNA and HBcrAg, to characterization of HBV-HIV coinfection is unclear. We evaluated the longitudinal dynamics of HBV RNA and HBcrAg and their association with classical HBV serum biomarkers and liver histology and viral staining.

Methods:

HBV-HIV co-infected adults from 8 North American centers entered a NIH-funded prospective cohort study. Demographic, clinical, serological and virological data were collected at entry and every 24–48 weeks for up to 192 weeks. Participants with HBV RNA and HBcrAg measured ≥2 times (N=95) were evaluated; 56 had paired liver biopsies obtained at study entry and end of follow-up.

Results:

Participants had a median age of 50 years; 97% were on cART. In HBeAg+ participants, there were significant declines in HBV RNA and HBcrAg over 192 weeks that tracked with declines in HBeAg, HBsAg, HBV DNA and HBcAg hepatocyte staining grade (all p<.05). In HBeAg- participants, there were not significant declines in HBV RNA (p=.49) and HBcrAg (p=.63) despite modest reductions in HBsAg (p<.01) and HBV DNA (p=.03). HBV serum biomarkers were not significantly related to change in hepatic activity index, Ishak fibrosis score or hepatocyte HBcAg loss (all p>.05).

Conclusions:

In HBV-HIV coinfected adults on suppressive dually active antiviral therapy use of novel HBV markers reveals continued improvement in suppression of HBV transcription and translation over time. The lack of further improvement in HBV serum biomarkers among HBeAg- patients suggests limits to the benefit of cART and provide rationale for additional agents with distinct mechanisms of action.

Keywords: HBV, HIV, HBV RNA, HBcrAg, serum biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) leads to liver injury ranging from minimal damage to cirrhosis. Historically, histology has been accepted as the gold standard for assessing injury, but liver biopsy carries inherent risks. For this reason, novel serum markers have been introduced in the hopes of accurately reflecting histologic disease severity as well as HBV transcriptional and translational status.

Among these novel noninvasive markers are several serum-based assays: quantitative measures of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg), and HBV RNA and HBV core-related antigen (HBcrAg). Each assay is thought to reflect transcription from cccDNA and translation of viral proteins from transcribed HBV RNA1,2. In a previous analysis of HBV-HIV coinfected adults who underwent liver biopsy at study entry, we demonstrated that HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels reflected persistent transcription and translation with high levels of intrahepatic HBV protein staining despite ostensible viral suppression on antiviral therapy3.

Among participants in the same cohort study who underwent follow-up biopsy approximately 4 years later, we reported that HBsAg and HBeAg levels decreased commensurately with HBV DNA overall and specifically among HBeAg+ participants4. We did not, however, evaluate HBV RNA and HBcrAg over time. Furthermore, it is unknown how these biomarkers correspond to histologic and HBV immunohistologic changes in the setting of HBV suppression. In this follow-up report, we evaluate the longitudinal dynamics of HBV RNA and HBcrAg and their correlation with other HBV biomarkers, and the relationship of these biomarkers with changes in liver histology and viral antigen staining among the same HBV-HIV sample.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Adult patients (>18 years) who were anti-HIV positive and HBsAg positive for at least 6 months were recruited from 8 Hepatitis B Research Network (HBRN) clinical centers in the US and Canada for this prospective cohort study. Detectable HCV RNA and/or HDV RNA < 6 months from entry, decompensated cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were exclusion criteria. Participants underwent evaluation at study entry and every 24 weeks thereafter for up to 192 weeks. Evaluations included liver biopsy on entry and exit (144–192 weeks post-entry), regardless of clinical status but without evidence of decompensated cirrhosis. Nearly all participants were on combination anti-viral therapy (cART) including an anti-HBV nucleos(t)ide analogue. However, cART could be stopped, initiated or changed per standard of care. The institutional review board at each center approved the protocol, and participants gave written informed consent. The study is registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01924455).

One hundred thirty-nine HBV-HIV adults consented and underwent a baseline assessment. Four were discovered to be HBsAg negative via central laboratory testing. Of the 135 HBsAg positive study participants, 40 were excluded from this report due to lack of stored serum available at baseline and at least one follow-up to test HBV RNA and HBcrAg, which was done as an ancillary study, leaving 95 participants, 3 of whom were anti-HCV positive (without detectable HCV RNA <6 months) and 1 of whom was anti-HDV positive at study entry. Among these 95 participants, 43 did not have two required liver biopsies, leaving 56 participants in the paired biopsy subsample.

Assessments

Assessments included demographics, medical history and current health status, with self-report and interviewer-administered questionnaires, physical examination and blood tests as previously described5. Relevant clinical, laboratory, and radiological data were extracted from medical records.

Research blood samples were collected at each assessment. Quantitative HBV DNA, quantitative HBeAg (qHBeAg) and quantitative HBsAg (qHBsAg) were tested centrally by University of Washington, Seattle, WA. Quantitative HBV RNA and HBcrAg were tested centrally by Abbott Diagnostics, Abbott Park, IL. Liver biopsy was performed in standard fashion. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) and Masson trichrome staining was done centrally by University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. The HBRN Pathology Committee centrally scored histological findings including immunostaining for HBsAg and HBcAg. Details regarding serum-based assays, histology and immunostaining are provided in Supplemental Digital Content (SDC) 1, Appendix.

Analysis

Participants were categorized by HBeAg status throughout follow-up (always positive, positive to negative, and always negative). Among each HBeAg group, generalized linear mixed-effects models were used to model the mean (95% confidence interval (CI)) of serum-based HBV markers (qHBeAg, qHBsAg, HBV DNA, HBV RNA, HBcrAg) every 48 weeks and test for a change over time, with each outcome as a repeated measure, time (i.e., days since baseline assessment) as a continuous fixed effect, and random intercept. Correlations between change (last follow-up - baseline value) in HBV RNA and change in HBcrAg, with each other and with change in HBV DNA, qHBeAg and qHBsAg, respectively, were tested with Spearman’s rank correlation, stratified by HBeAg status throughout follow-up.

Among paired biopsies (N=56), changes in intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg staining (grade and patterns) were tested with mixed-effects models (binomial, ordinal logistic or multinomial, as appropriate), with each outcome as a repeated measure, time (days since baseline biopsy) as a continuous fixed effect, and random intercept. Box plots were used to visualize change in HBV RNA and HBcrAg between biopsies by change in intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg staining grades, respectively, stratified by baseline HBeAg status (since very few participants lost HBeAg during follow-up in the biopsy subsample). A change from grade C or B➔A or from C➔B = less; a change from grade A➔ B or C, or from B➔C = more; no change in grade = same. Associations were tested using Kruskal-Wallis.

Among participants in the paired biopsy sample who were positive for HBcAg hepatocytes at entry (N=35), logistic regression models were used to evaluate baseline serum biomarkers of HBV, including HBV RNA and HBcrAg, as predictors of becoming negative. Changes in each serum biomarker of HBV were also evaluated in relation to becoming negative for HBcAg hepatocytes. Likewise, linear regression models were used to test associations between serum biomarkers of HBV with changes in the hepatic activity index (HAI) and Ishak fibrosis score, among the biopsy subsample, with control for days between biopsies.

Analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (Cary NC, 2000). P values are 2-sided 6.

Results

Participant characteristics at study entry (N=95)

At study entry 93% of participants were male, 48% were non-Hispanic Black and 34% non-Hispanic White. Almost all (97%) participants were on dually active cART; 84% had dual complete viral suppression (HBV DNA <1000 IU/mL, HIV RNA <400 copies/mL), 12% had partial suppression (HBV DNA ≥1000 IU/mL, HIV RNA <400 copies/mL); neither virus was suppressed in 5%. Nine (9%) participants had known cirrhosis. Additional baseline characteristics of the full sample, and characteristics of the biopsy subsample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the full HBV-HIV analysis sample and paried biopsy subsample, overall and stratified by HBeAg status

| Full analysis sample |

Biopsy subsample |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n=95 | HBeAg positive n=58 | HBeAg negative n=37 | Total n=56 | HBeAg positive n=33 | HBeAg negative n=23 | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 50 (46, 55) | 49.5 (45, 54) | 51 (47, 56) | 50.5 (46, 54) | 49 (46, 54) | 52 (48, 56) |

| Male, n (%) | 88 (92.6) | 51 (87.9) | 37 (100.0) | 53 (94.6) | 30 (90.9) | 23 (100.0) |

| Race, n (%) | n=93 | n=57 | n=36 | n=54 | n=32 | n=22 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 32 (34.4) | 21 (36.8) | 11 (30.6) | 15 (27.8) | 10 (31.3) | 5 (22.7) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 45 (48.4) | 25 (43.9) | 20 (55.6) | 28 (51.9) | 16 (50.0) | 12 (54.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 5 (5.4) | 2 (3.5) | 3 (8.3) | 4 (7.4) | 1 (3.1) | 3 (13.6) |

| Other | 11 (11.8) | 9 (15.8) | 2 (5.6) | 7 (13.0) | 5 (15.6) | 2 (9.1) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | n=92 | n=56 | n=36 | n=54 | n=32 | n=22 |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 25.8 (22.6, 30.0) | 26.6 (22.5, 31.6) | 25.2 (22.6, 27.3) | 25.8 (22.8, 29.3) | 25.8 (22.2, 30.0) | 25.9 (23.3, 27.1) |

| Estimated years of HBV or HIV | n=89 | n=53 | n=36 | n=51 | n=29 | n=22 |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 21 (15, 28) | 22 (16, 26) | 20 (11.5, 30) | 22 (15, 28) | 21 (16, 25) | 22.5 (15, 30) |

| HBV treatment, n (%) | ||||||

| Tenofovir alone/combination | 84 (88.4) | 52 (89.7) | 32 (86.5) | 51 (91.0) | 31 (93.9) | 20 (87.0) |

| Entecavir alone/combination | 8 (8.5) | 4 (6.8) | 4 (10.8) | 5 (9.0) | 2 (6.1) | 3 (13.0) |

| Lamivudine alone | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| None | 2 (2.1) | 1 (1.7) | 1 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Nucleoside/Nucleotide Reverse Transcriptase Inhibitor use, n (%) | 91 (95.8) | 55 (94.8) | 36 (97.3) | 54 (96.4) | 32 (97.0) | 22 (95.7) |

| ALT (U/L) | n=91 | n=56 | n=35 | n=55 | n=22 | |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 24 (18, 39) | 24 (17, 42.5) | 27 (19, 37) | 24 (18, 36) | 24 (18, 34) | 26.5 (19, 36) |

| AST (U/L) | n=91 | n=56 | n=35 | n=55 | n=22 | |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 28 (22, 41) | 27 (22, 38) | 29 (22, 45) | 27 (21,41) | 27 (22, 32) | 28.5 (21,48) |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL) | n=90 | n=55 | n=35 | n=54 | n=32 | n=22 |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.6) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.8) | 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) |

| Albumin (g/dL) | n=91 | n=56 | n=35 | n=55 | n=22 | |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 4.4 (4.1,4.7) | 4.5 (4.1,4.7) | 4.4 (4.1,4.5) | 4.4 (4.2, 4.7) | 4.4 (4.2, 4.8) | 4.4 (4.1,4.5) |

| Platelets (x103/mm3) | n=93 | n=35 | n=55 | n=22 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 197 (175, 234) | 194 (175, 240) | 200 (167, 226) | 201 (174, 251) | 226 (182, 263) | 198.5 (164, 220) |

| FIB-4 | n=91 | n=56 | n=35 | n=55 | n=22 | |

| Median (25th, 75th) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.7) | 1.5 (1.0, 2.2) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.9) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.6) | 1.8 (1.0, 2.2) |

| HBeAg, n (%) | ||||||

| Positive | 58 (61.1) | 58 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) | 33 (58.9) | 33 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| HBeAg (log10 IU/mL) | n=94 | n=36 | n=55 | n=22 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 0.1 (−0.7, 1.4) | 1.0 (0.1,2.1) | −0.9 (−1.1, −0.6) | 0.0 (−0.7, 1.2) | 0.4 (0.1, 1.7) | −0.8 (−1.1, −0.6) |

| HBsAg (log10 IU/mL) | n=94 | n=36 | n=55 | n=22 | ||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 3.2 (2.8, 3.8) | 3.4 (3.1,4.1) | 2.6 (1.9, 3.3) | 3.1 (2.5, 3.4) | 3.3 (3.1,3.8) | 2.2 (1.7, 3.1) |

| HBV DNA (log10 IU/mL) | ||||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.8) | 1.3 (1.1,3.4) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.7) | 1.2 (1.0, 2.0) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.2) |

| CD4 (cells/mm3) | n=85 | n=53 | n=32 | n=52 | n=31 | n=21 |

| 567 | 567 | 567 | 560 | 516 | 574 | |

| Median (25th, 75th) | (369, 680) | (374, 680) | (354.5, 695.5) | (358.5, 672.5) | (343, 629) | (393, 718) |

| HIV RNA (copies/mL) | n=85 | n=53 | n=32 | n=50 | n=31 | n=19 |

| <20 | 68 (80.0) | 39 (73.6) | 29 (90.6) | 43 (86.0) | 25 (80.6) | 18 (94.7) |

| 20 – <400 | 13 (15.3) | 10 (18.9) | 3 (9.4) | 5 (10.0) | 4 (12.9) | 1 (5.3) |

| 400 – <10000 | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| ≥10000 | 3 (3.5) | 3 (5.7) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| HBV DNA (IU/mL) and HIV | n=85 | n=53 | n=32 | n=50 | n=31 | n=19 |

| RNA (copies/mL) suppression status | ||||||

| Suppressed (HBV DNA <1000, HIV RNA <400) | 71 (83.5) | 39 (73.6) | 32 (100.0) | 43 (86.0) | 24 (77.4) | 19 (100.0) |

| Incompletely suppressed (HBV DNA ≥1000, HIV RNA <400) | 10 (11.8) | 10 (18.9) | 0 (0.0) | 5 (10.0) | 5 (16.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not suppressed (HBV DNA ≥1000, HIV RNA ≥400) | 4 (4.7) | 4 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.0) | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) |

| HBV RNA (log10 U/mL) | ||||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 3.8 (1.8, 5.6) | 5.3 (3.9, 6.6) | 1.4 (0.1,2.2) | 3.5 (1.8, 5.5) | 4.8 (3.6, 6.4) | 1.8 (0.0, 2.5) |

| HBcrAg (log10 U/mL) | ||||||

| Median (25th, 75th) | 5.5 (3.4, 7.0) | 6.3 (5.5, 8.2) | 3.3 (1.9, 4.0) | 5.3 (3.7, 6.5) | 6.3 (5.4, 7.8) | 3.3 (1.9, 4.3) |

Accroymns: ALT, Alanine Aminotransferase; AST, Aspartate aminotransferase; CD4, Cluster of differentiation 4; DNA, Deoxyribonucleic acid; FIB-4, Fibrosis-4; HBcrAg, Hepatitis B core-related antigen; HBV, Hepatitis B virus; HCV, Hepatitis C virus; HDV, Hepatitis D virus; HIV, Human immunodeficiency virus; HBeAg, Hepatitis B e-antigen; HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen; RNA, Ribonucleic acid.

Novel serum-based HBV markers over time

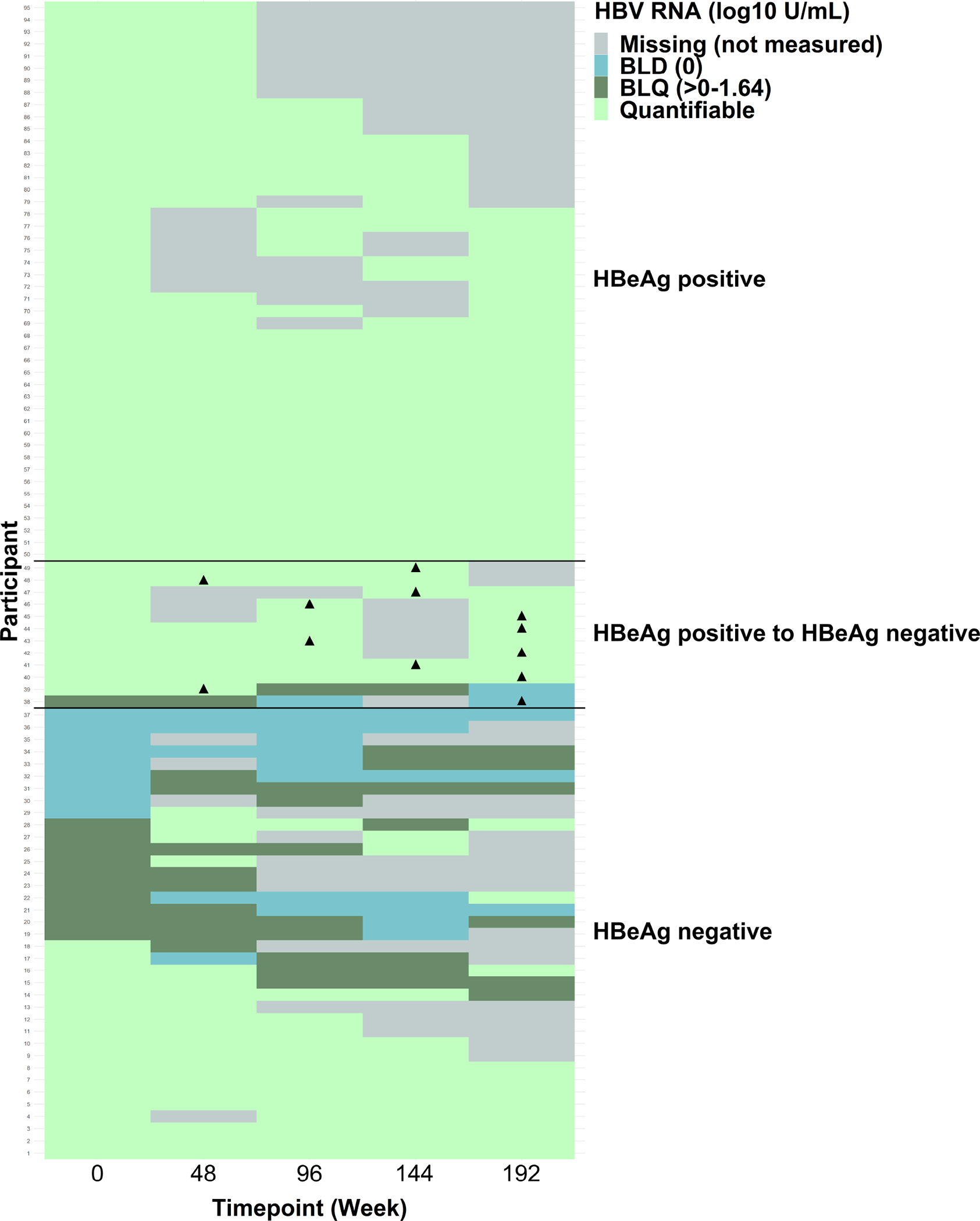

A heat map shows HBV RNA categories (below LLD [BLD], below LLQ [BLQ] and quantifiable) by time point, stratified by HBeAg status throughout follow-up (always positive, positive to negative, and always negative) (Figure 1). Just under half (n=46) were HBeAg positive throughout follow-up; their HBV RNA was always quantifiable. Twelve participants were HBeAg positive at baseline but HBeAg negative at least once during follow-up (2 [16.7%] were first HBeAg negative at week 48, 2 [16.7%] at week 96, 3 [25.0%] at week 144 and 5 [41.7]% at week 192); 10 of these 12 (83%) always had quantifiable HBV RNA, whereas HBV RNA was mostly unquantifiable following HBeAg loss in 1 (8%), and always unquantifiable in another (8%) despite not losing HBeAg until the last assessment. Thirty-seven participants were HBeAg negative throughout follow-up; HBV RNA was never quantifiable in 13 (35%), always quantifiable in 13 (35%), and some combination in the other 11 (30%).

Figure 1.

Heat map of HBV RNA categories by time point, stratified by HBeAg status ▲ Marks the first time the participant was eAg negative in the HBeAg positive to HBeAg negative group

Among the 95 participants, 46 were HBeAg positive throughout follow-up; their HBV RNA was always quantifiable. Twelve participants were HBeAg positive at baseline but were HBeAg negative at least once during follow-up; 10 always had quantifiable HBV RNA, whereas HBV RNA was most often unquantifiable in 1 and always unquantifiable in another. Thirty-seven participants were HBeAg negative throughout follow-up; they had a variety of HBV RNA patterns: HBV RNA was never quantifiable in 13, always quantifiable in 13, and some combination in the other 11.

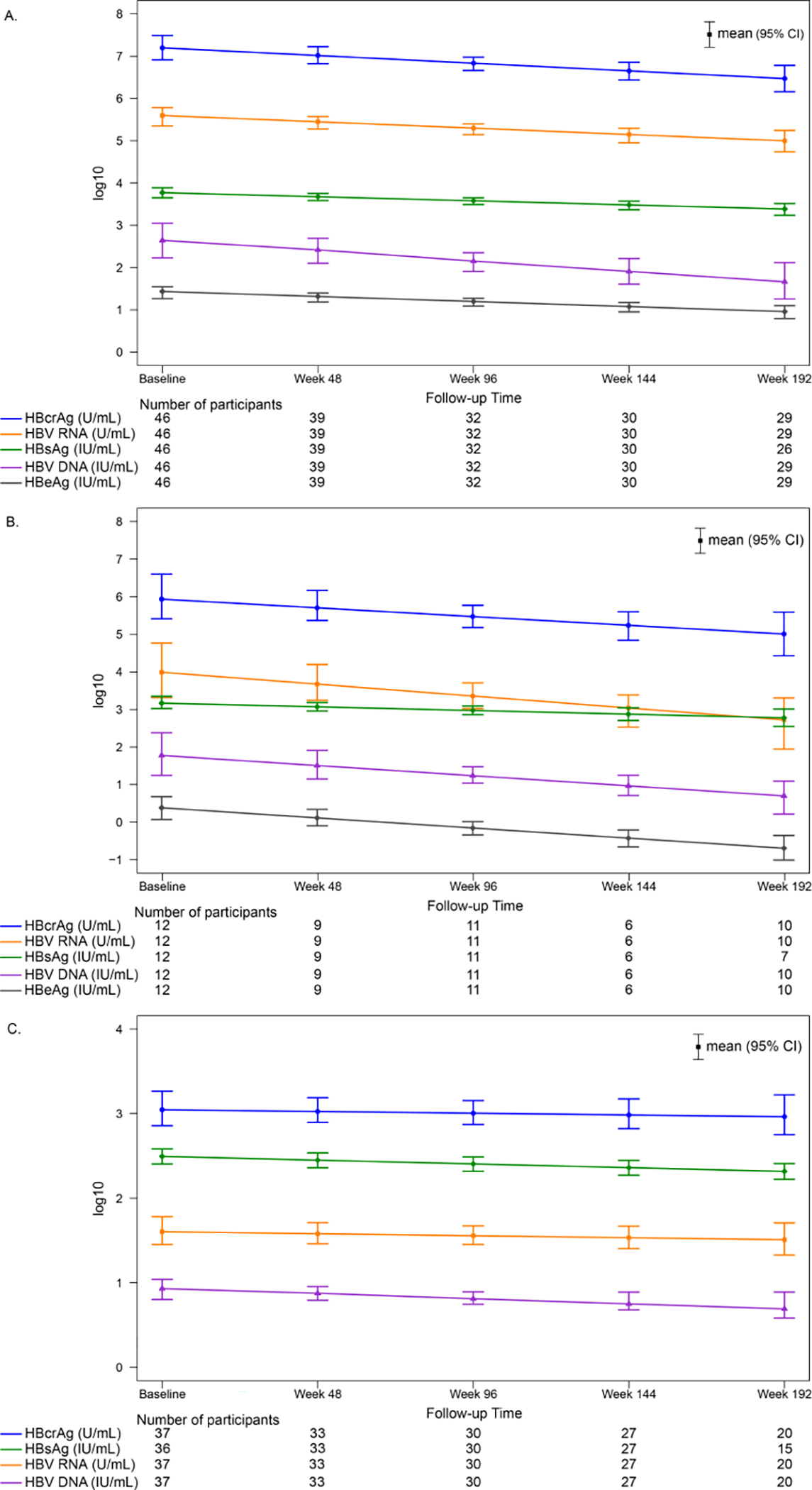

Descriptive statistics of serum-based HBV markers by time point, stratified by HBeAg status, are provided in SDC 2–3 Tables 1–2. The modeled means (95% CI) of HBV RNA, HBcrAg, HBV DNA, qHBeAg and qHBsAg over time (weeks 0–192) are reported in SDC 4, Table 3 and shown in Figure 2. There was a significant decrease in HBV RNA, HBcrAg, HBV DNA, qHBeAg and qHBsAg among HBeAg positive (panel A) and HBeAg positive to negative (panel B) participants (P for all<.05). Among participants who were HBeAg negative throughout the study, there was a significant decrease over time in HBV DNA (P=.03) and qHBsAg (P<.001), but not HBV RNA (P=.49) or HBcrAg (P=.63) (panel C).

Figure 2.

Modeled means (95% CI) of HBV DNA, HBV RNA, HBcrAg, qHBeAg and qHBsAg by time point, stratified by HBeAg status throughout follow-up

A. HBeAg positive

B. HBeAg positive to negative during follow-up

C. HBeAg negative

There was a significant decrease in HBV DNA, HBV RNA, HBcrAg, qHBeAg and qHBsAg among HBeAg positive (panel A) and HBeAg positive to negative (panel B) participants (P for all<.05). Among HBeAg negative participants, there was a significant decrease over time in HBV DNA (P=.03) and qHBsAg (P<.001), but not HBV RNA (P=.49) or HBcrAg (P=.63).

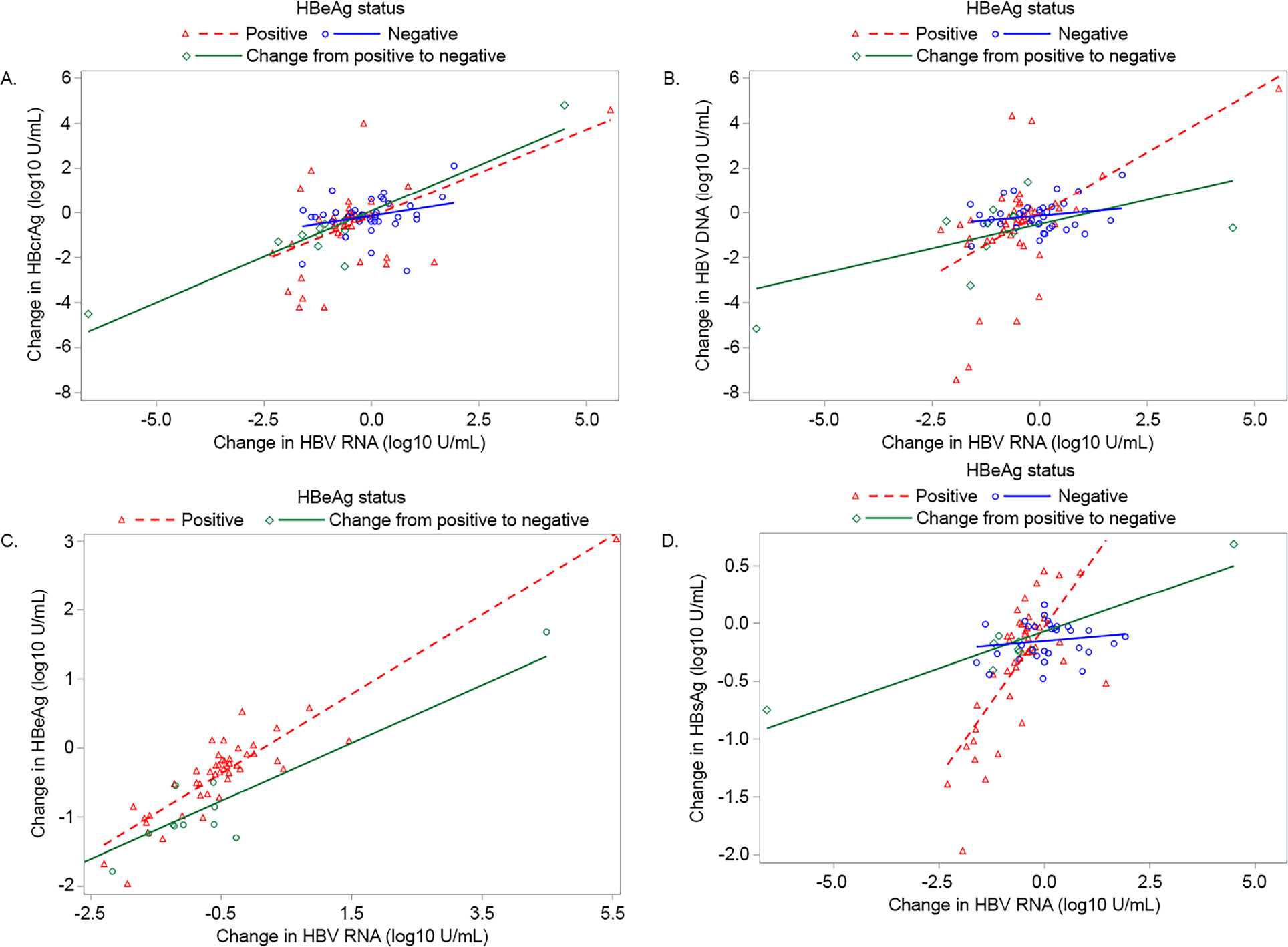

Among participants who were HBeAg positive throughout follow-up, correlations between changes in HBV RNA and HBcrAg (ρ=0.42), HBV DNA (ρ=0.48), qHBeAg (ρ=0.83) and qHBsAg (ρ=0.68), respectively, ranged from low to high (p for all<.01; Figure 3). Correlations were similar in the HBeAg positive to negative group (HBcrAg ρ=0.79; p=.002, HBV DNA ρ=0.52; p=.08, qHBeAg ρ=0.64; p=.02 and qHBsAg ρ=0.52; p=15), whereas among participants who were HBeAg negative throughout follow-up, correlations were weak (P>.20). Correlations between change in HBcrAg with change in HBV DNA, qHBeAg and qHBsAg (reported in SDC 5, Figure 1) were not as strong as with change in HBV RNA, regardless of HBeAg status.

Figure 3.

Correlations between change (last follow-up value - baseline value) in HBV RNA with change in HBcrAg, HBV DNA, qHBeAg and qHBsAg, respectively, stratified by HBeAg status throughout follow-up

A. HBV RNA (log10 U/mL) and HBcrAg (log10 U/mL)

HBeAg positive: n=46, ρ=.42, p=.003

HBeAg positive to negative: n=12, ρ=.79, p=.002

HBeAg negative: n=37, ρ=.20, p=.23

B. HBV RNA (log10 U/mL) and DNA (log10 IU/mL)

HBeAg positive: n=46, ρ=.48, p<.001

HBeAg positive to negative: n=12, ρ=.52, p=.08

HBeAg negative: n=37, ρ=.05, p=0.77

C. HBV RNA (log10 U/mL) and qHBeAg (log10 IU/mL)

HBeAg positive: n=46, ρ=.83, p<.001

HBeAg positive to negative: n=12, ρ=.64, p=.02

D. HBV RNA (log10 U/mL) and qHBsAg (log10 IU/mL)

HBeAg positive: n=43, ρ=.68, p<.001

HBeAg positive to negative: n=9, ρ=.52, p=.15

HBeAg negative: n=31, ρ=.13, p=.49

Intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg staining measures over time

Among the paired biopsy subsample (N=56), median (IQR) total biopsy length was 18 (14–23) mm at study entry and 17 (13–20) mm at follow-up, with 3.6 (3.0–3.7) years between biopsies. Intrahepatic HBcAg and HBsAg staining measures are reported by biopsy time point in Table 2. Fewer participants had hepatocytes positive for HBcAg at end of follow-up (38%) versus baseline (63%; p<.01). The distribution of grades also appeared to decrease over time, with only 7% grade C at follow-up versus 13% at entry (p=.06). At follow-up, over one-third (36%; n=20) of participants had a lower grade of HBcAg staining, while 5% (n=3) had a higher grade. The distribution of HBcAg patterns also changed (p=.02); at follow-up versus baseline fewer had only/predominantly nuclear staining (23% versus 36%) and only/predominantly cytoplasmic staining (14% versus 27%).

Table 2.

IH staining grades and patterns in HBV-HIV Co-infected North American Adults at study entry and approximately 3–4 years later (N=56).

| Baseline n (%) | Follow-up n (%) | Change P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HBcAg staining grade, n (%) | 0.058 | ||

| A (No positive hepatocytes) | 21 (37.5) | 35 (62.5) | |

| B (Less than 10% positive) | 28 (50.0) | 17 (30.4) | |

| C (≥10% positive) | 7 (12.5) | 4 (7.1) | |

| HBcAg staining pattern | 0.02 | ||

| No positive hepatocytes | 21 (37.5) | 35 (62.5) | |

| Only/predominately nuclear | 20 (35.7) | 13 (23.2) | |

| Only/predominately cytoplasmic | 15 (26.8) | 8 (14.3) | |

| HBsAg staining grade, n (%) | 0.63 | ||

| A (No positive hepatocytes) | 13 (23.2) | 16 (28.6) | |

| B (Less than 10% positive) | 33 (58.9) | 32 (57.1) | |

| C (≥10% positive) | 10 (17.9) | 8 (14.3) | |

| HBsAg staining: Granular cytoplasmic- contiguous regions pattern | 0.04 | ||

| No | 36 (64.3) | 45 (80.4) | |

| Yes | 20 (35.7) | 11 (19.6) | |

| HBsAg staining pattern: Granular cytoplasmic-scattered hepatocytes b | 0.44 | ||

| No | 16 (28.6) | 19 (33.9) | |

| Yes | 40 (71.4) | 37 (66.1) | |

| HBsAg staining pattern: Inclusion-like b | 0.03 | ||

| No | 29 (51.8) | 40 (71.4) | |

| Yes | 27 (48.2) | 16 (28.6) | |

| HBsAg staining pattern: Membranous b | 0.21 | ||

| No | 45 (80.4) | 49 (87.5) | |

| Yes | 11 (19.6) | 7 (12.5) |

Changes were tested with mixed-effects models (binomial, ordinal logistic or multinomial, as appropriate) with a repeated outcome, time (i.e., days since first biopsy) as a continuous fixed effect, and random intercept. Median (IQR; range) of time between biopsies was: 3.6 (3.0–3.7; 2.6–4.1) years.

There was no significant difference in percentage of participants with hepatocytes positive for HBsAg (77% at follow-up versus 71% at baseline; p=.44), nor a temporal difference in the distribution of HBsAg staining grades (p=.63). However, HBsAg staining patterns differed by time point (Table 2). Specifically, granular cytoplasmic HBsAg staining of contiguous regions, and inclusion-like HBsAg staining were less common at follow-up (20% versus 36%; p=.04, and 29% versus 48%; p=.03, respectively).

Boxplots showing the distribution of change between baseline and follow-up biopsies in HBV RNA and HBcrAg, respectively, and staining IH HBcAg grade and IH HBsAg grade, respectively, stratified by HBeAg baseline status are provided in SDC 6, Figure 2. Among HBeAg positive participants, there was a larger decrease in HBV RNA (p=.047) and HBcrAg (p=.04) in those with a decrease (versus no change or an increase) in HBcAg staining grade between biopsies, whereas changes in these serum biomarkers did not differ (p>.50) by change in HBsAg staining grade. Among HBeAg negative participants, only 3 participants had a change in HBcAg staining grade (all less) and neither HBV RNA nor HBcrAg differed (p≥.49). While ten participants had a change in HBsAg staining grade (7 less, 3 more) change in HBV RNA did not differ (p=0.55). However, change in HBcrAg differed (p=.045), with the largest decrease in those with an increase in intrahepatic HBsAg stain(SDC 6, Figure 2).

Among participants positive for HBcAg staining at study entry (n=35), associations between baseline participant characteristics and becoming negative for HBcAg staining in hepatocytes are reported in SDC 7, Table 4. No baseline factors were significantly related to becoming negative. However, compared to being HBeAg positive throughout follow-up, HBeAg loss (OR=33.3, 95%CI 3.2–350.9) and being HBeAg negative throughout (OR=14.3, 95%CI, 1.2, 174.8) were associated with higher odds of becoming negative for HBcAg staining in hepatocytes (p<.01).

We previously reported associations between baseline factors and changes in HAI and Ishak fibrosis score, respectively4, but did not evaluate HBV RNA and HBcrAg. Neither baseline HBV RNA, HBcrAg, nor change in serum-based HBV markers were significantly related to either outcome (SDC 7, Table 4).

DISCUSSION

Two novel biomarkers, HBV RNA and HBcrAg, that reflect transcriptional activity of cccDNA, have been evaluated in HBV mono-infection, but few reports exist in HBV-HIV co-infection. In this study we assessed associations between HBV RNA and HBcrAg with other virologic markers and liver histology using a North American HBV-HIV coinfected cohort, the majority of whom were on cART and had HBV replication suppressed. At study entry, among HBeAg positive participants, HBV RNA and HBcrAg were always quantifiable and declined over time. In contrast, among HBeAg negative participants, HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels were generally lower and more variable and did not change significantly over 4 years of follow-up. Changes in HBV RNA were moderately correlated with changes in HBcrAg among HBeAg positive but not HBeAg negative participants. Among participants with paired liver biopsies, there was an overall decline in frequency of HBcAg positive hepatocytes and change in staining pattern. In contrast, there was no significant decline in HBsAg staining grades for hepatocytes but there was a qualitative change with less granular cytoplasmic-contiguous and inclusion-like staining patterns. Interestingly, decline in HBV RNA and HBcrAg were associated with decline in HBcAg staining grade (but not loss of HBcAg hepatocytes) in HBeAg positive but not HBeAg negative participants.

Our results demonstrate a clear relationship between HBV RNA, HBcrAg and by inference, HBV transcription status, in HBeAg positive but not HBeAg negative, predominantly virally suppressed HBV-HIV co-infected participants. The continued detection of HBV RNA and HBcrAg and strong correlation between the two markers in HBeAg positive participants despite viral suppression in the majority suggests ongoing viral transcription from cccDNA. The significant, albeit gradual decline in HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels that tracked with HBsAg and HBV DNA levels suggests that there could be an eventual loss of HBeAg and perhaps development of anti-HBe with continued maintenance antiviral therapy. We could only demonstrate this in a minority of participants perhaps due to relatively short follow-up. These data raise the possibility that monitoring HBV RNA and HBcrAg could predict HBeAg loss in HBV-HIV co-infection, as has been suggested in HBV mono-infection7.

In HBeAg negative participants, we observed no meaningful reductions in HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels. This may be because HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels were already low in many HBeAg negative participants due to reduced amounts of cccDNA and silencing of residual cccDNA8 and may have reached their nadir prior to study enrollment. Minimal decline would be expected, as nucleoside analogues have marginal if any effect on viral transcription. These results suggest that monitoring HBV RNA and HBcrAg during antiviral treatment may not be as informative in HBeAg negative as in HBeAg positive patients.

Analysis of HBcAg and HBsAg immunostains in paired liver biopsies revealed a reduction in the proportion of hepatocytes staining for HBcAg and a near doubling of biopsies lacking HBcAg staining. Moreover, a reduction in HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels was associated with a lower HBcAg staining grade at follow-up in HBeAg positive but not HBeAg negative participants. These findings suggest that clearance of HBcAg requires inhibition of both viral replication and viral transcription through elimination/silencing of cccDNA. This may also be required for resolution of disease as shown by trends in further reduction in inflammation and fibrosis with decline in HBV RNA and HBcrAg in virally suppressed participants. In contrast to the decline in HBcAg, we observed minimal to no change over time in the percentage of participants positive for HBsAg hepatocytes and no relationship between changes in HBV RNA levels and HBsAg staining in both HBeAg positive and negative participants. The presence of detectable HBsAg in the setting of viral suppression, low or undetectable HBV RNA in HBeAg negative participants, and overall poor correlation with HBV RNA levels, suggest that HBsAg may be largely derived from integrated HBV DNA as opposed to cccDNA, as has been suggested in HBeAg negative chimpanzees 9. This raises the question as to whether HBsAg loss may ever be achievable in such patients, but does not exclude the possibility that HBV DNA and persistently HBV RNA negative patients could be safely withdrawn from antiviral therapy10,11. It should be noted that HBV RNA levels can fluctuate from undetectable to detectable, so interpretations and decisions based on HBV RNA levels should occur in the context of serial assessments.

The following study limitations should be considered. Nearly all participants were on long-duration cART containing a potent anti-HBV agent at time of enrollment with excellent HBV DNA suppression and normalized ALT; therefore, pre-treatment HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels could not be determined. We also did not have complete information regarding duration or composition of antiviral therapy for all patients to correlate this with the observed kinetic differences in markers between HBeAg positive and negative groups. We lacked a control group of HBV mono-infected participants to compare changes in HBcAg and HBsAg staining and their relationship to changes in HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels. We defined viral suppression as an HBV DNA cutoff of <1,000 IU/mL which differs from studies in mono-infected patients that have use the level of quantification of current PCR-based assays (<20 IU/ml). Unfortunately, the sample size was too small to conduct a sensitivity analysis to determine if findings would differ in those with lower HBV DNA levels. Additionally, sample size limited our ability to evaluate if and how novel assays changed with HBeAg loss, and how HBeAg status related to HBcAg staining patterns. However, we were able to show that HBeAg status is related to loss of HBcAg hepatocytes. Despite the high frequency of the suppressed phenotype and long treatment, our finding of continued decline in markers of HBV transcription/translation in HBeAg positive patients and a plateau of these markers in HBeAg negative patients is all the more notable for the continued slow/stalled decline in the context of HIV coinfection.

In summary, this study demonstrates that HBV RNA and HBcrAg remain detectable in all HBeAg positive HBV-HIV co-infected participants, suggesting ongoing viral transcription. Declines in these two biomarkers over time appears to be primarily associated with HBeAg loss, given the marked difference in values by HBeAg status, and were correlated with decline in hepatic HBcAg. These data suggest a role for monitoring HBV RNA and HBcrAg in HBeAg positive patients. The minimal decline in levels and weak association between HBV RNA and HBcrAg with HBcAg staining suggest a limited clinical utility in HBeAg negative patients. Although there was not a formal untreated comparator group, these data support the concept that cART should be continued in the absence of HBeAg and HBsAg loss. Persistence of HBsAg staining despite full suppression of replication/transcription/translation suggests integrated HBV as the source for HBsAg. These data underscore the need for additional therapies directed at other HBV targets to accomplish a functional cure of HBV.

Supplementary Material

What You Need to Know.

Background

Most HBV-HIV coinfected adults are on dually active antiviral therapy.

HBeAg, HBsAg and HBV DNA levels are important biomarkers of HBV infection activity.

New serum biomarkers, including HBV RNA and HBcrAg, reflect HBV transcription and may provide more accurate assessment of HBV activity.

Findings

In HBV-HIV coinfected HBeAg+ participants, HBV RNA and HBcrAg levels decreased over 192 weeks.

HBV RNA and HBcrAg decreases corresponded with decreases in HBeAg, HBsAg and HBV DNA.

In HBeAg- participants, HBsAg and HBV DNA, but not HBV RNA and HBcrAg (p≥.05), declined over 192 weeks.

Implications for patient care

These data support that in HIV coinfected adults, HBV infection control continues over time.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Jeffrey Gersch and Mark Anderson, Abbott Diagnostics, who performed the HBV RNA testing.

Potential competing interests

Raymond T. Chung was partially supported by NIH R01AI155140 and has received research grants to his institution from Abbvie, Gilead Sciences, BMS, Roche, Boehringer, and Merck.

Wendy C. King has nothing to disclose.

Marc G. Ghany has nothing to disclose.

Mauricio Lisker-Melman, speakers bureau: AbbVie, Gilead.

Amanda S. Hinerman has nothing to disclose.

Mandana Khalili was partially supported by K24AA022523 and is a recipient of research grant (to her institution) from Gilead Sciences Inc, and Intercept Pharmaceuticals and she has served as consultant for Gilead Sciences Inc

Mark Sulkowski is a consultant and receives research support from Gilead.

Mamta K. Jain: Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Merck, GSK/ViiV

E. Karen Choi has nothing to disclose.

Michael A. Nalesnik has nothing to disclose.

Atul K. Bhan has nothing to disclose.

Gavin Cloherty is an employee and shareholder of Abbott.

David K. Wong: Research Grants to institution: Gilead, BMS, Vertex, Boehringer Richard K. Sterling has received research grants from Gilead, Abbott, Abbvie, Roche to the University. He also has served on the Data Safety Monitoring Boards for Pfizer and AskBio.

Financial support

This study was funded by Abbott Diagnostics as an ancillary study of the Hepatitis B Research Network (HBRN) to Dr. Richard K. Sterling. The authors acknowledge the use of HBRN samples and data as the sole contribution of the HBRN. The HBRN was funded as a Cooperative Agreement between the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) and the following investigators Lewis R. Roberts, MB, ChB, PhD (U01-DK082843), Anna Suk-Fong Lok, MD (U01-DK082863), Steven H. Belle, PhD, MScHyg (U01-DK082864), Kyong-Mi Chang, MD (U01-DK082866), Michael W. Fried, MD (U01-DK082867), Adrian M. Di Bisceglie, MD (U01-DK082871), William M. Lee, MD (U01-DK082872), Harry L. A. Janssen, MD, PhD (U01-DK082874), Daryl T-Y Lau, MD, MPH (U01-DK082919), Richard K. Sterling, MD, MSc (U01-DK082923), Steven-Huy B. Han, MD (U01-DK082927), Robert C. Carithers, MD (U01-DK082943), Mandana Khalili, MD (U01-DK082944), an interagency agreement with NIDDK: Lilia M. Ganova-Raeva, PhD (A-DK-3002–001) and support from the intramural program, NIDDK, NIH: Marc G. Ghany, MD. Additional funding to support this study was provided to Kyong-Mi Chang, MD, the Immunology Center (NIH/NIDDK Center of Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases P30DK50306, NIH Public Health Service Research Grant M01-RR00040), Richard K. Sterling, MD, MSc (UL1TR000058, NCATS (National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, NIH), Mandana Khalili, MD (CTSA Grant Number UL1TR000004), Michael W. Fried, MD (CTSA Grant Number UL1TR001111), and Anna Suk-Fong Lok (CTSA Grant Number UL1RR024986 and U54TR001959.) Additional support was provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc. and Roche Molecular Systems via a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA) through the NIDDK.

Footnotes

Data access

The analytic methods are described in the manuscript methods section. The data and study materials will not be made available to other researchers.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wong DK, Seto WK, Cheung KS, et al. Hepatitis B virus core-related antigen as a surrogate marker for covalently closed circular DNA. Liver Int. 2017;37(7):995–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Giersch K, Allweiss L, Volz T, Dandri M, Lütgehetmann M. Serum HBV pgRNA as a clinical marker for cccDNA activity. J Hepatol. 2017;66(2):460–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lisker-Melman M, Wahed A, Chung R, et al. 742 Active HBV transcription and translation persist despite suppression of viral replication in HIV/HBV co-infected patients receiving dually active antiretroviral therapy. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:S-1290. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sterling RK, King WC, Khalili M, et al. A Prospective Study Evaluating Changes in Histology, Clinical and Virologic Outcomes in HBV-HIV Co-infected Adults in North America. Hepatology. 2021;74(3):1174–1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sterling RK, Wahed AS, King WC, et al. Spectrum of Liver Disease in Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Patients Co-infected with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV): Results of the HBV-HIV Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(5):746–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wasserstein RL, Schirm AL, Lazar NA. Moving to a World Beyond “p < 0.05”. The American Statistician. 2019;73(sup1):1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Bömmel F, Bartens A, Mysickova A, et al. Serum hepatitis B virus RNA levels as an early predictor of hepatitis B envelope antigen seroconversion during treatment with polymerase inhibitors. Hepatology. 2015;61(1):66–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suslov A, Meier MA, Ketterer S, Wang X, Wieland S, Heim MH. Transition to HBeAg-negative chronic hepatitis B virus infection is associated with reduced cccDNA transcriptional activity. J Hepatol. 2021;74(4):794–800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wooddell CI, Yuen MF, Chan HL, et al. RNAi-based treatment of chronically infected patients and chimpanzees reveals that integrated hepatitis B virus DNA is a source of HBsAg. Sci Transl Med. 2017;9(409). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seto WK, Liu KS, Mak LY, et al. Role of serum HBV RNA and hepatitis B surface antigen levels in identifying Asian patients with chronic hepatitis B suitable for entecavir cessation. Gut. 2021;70(4):775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey I, Gersch J, Wang B, et al. Pregenomic HBV RNA and Hepatitis B Core-Related Antigen Predict Outcomes in Hepatitis B e Antigen-Negative Chronic Hepatitis B Patients Suppressed on Nucleos(T)ide Analogue Therapy. Hepatology. 2020;72(1):42–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.