Abstract

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) are rare. Although they originate from Schwann cells or pluripotent neural crest cells, they constitute less than 10% of all soft tissue sarcomas and more than 60% develop on the basis of neurofibromatosis. It is difficult to diagnose MPNST. Although it mostly occurs in the head and neck region or upper extremities, only 1% of cases are located in the retroperitoneal region. The main treatment is surgery, but survival results are not satisfactory even after surgery with R0 resection. They are not sensitive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and tend to recur locally. The mass detected by imaging in a 57-year-old male patient who admitted to hospital with the complaint of abdominal pain was excised with clear surgical margins. The tumor was located in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen and seemed to invade the pancreas and left kidney in the computed tomography images. The patient had no history of neurofibromatosis or radiation. In this study, it was aimed to present our case diagnosed with retroperitoneal MPNST and treated with multiorgan resection, which is a rare entity, and to increase the awareness of clinicians about the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis of this rare tumor.

Keywords: Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, Malignant Schwannoma, Multiorgan Resection, Retroperitoneal tumor

Introduction

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) are rare. Although they originate from Schwann cells or pluripotent neural crest cells, they constitute less than 10% of all soft tissue sarcomas and more than 60% develop on the basis of neurofibromatosis [1]. It is difficult to diagnose MPNST. Although it mostly occurs in the head and neck region or upper extremities, only 1% of cases are located in the retroperitoneal region. The main treatment is surgery, but survival results are not satisfactory even after surgery with R0 resection [2]. There are no specific symptoms or diagnostic criteria for MPNST. Patients usually admit to the hospital with complaints due to the mass effect in the area where the mass is located.

In this study, it was aimed to present our case diagnosed with retroperitoneal MPNST and treated with multiorgan resection, which is a rare entity, and to increase the awareness of clinicians about the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of this rare tumor.

Case Report

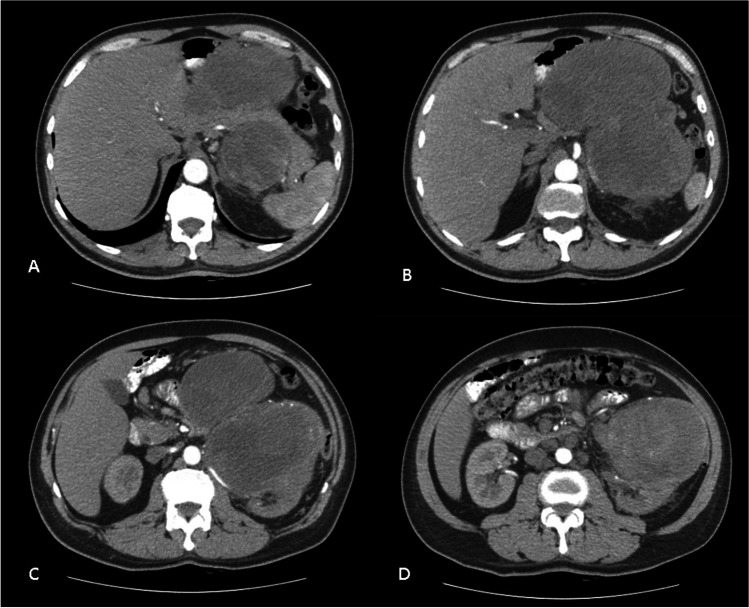

A 57-year-old male patient was admitted to the Generel Surgery Clinic, with the complaint of abdominal pain. The patient, who had no disease except hypertension and atrial fibrillation, had no history of previous surgery. No feature was detected in the family history. On physical examination, a hard fixed mass filling the left upper quadrant of the abdomen was palpated. There were no other features on physical examination. Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography (CT) revealed a 20 × 12 cm heterogeneously enhanced lobulated contoured mass lesion in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, in front of the left kidney, whose borders could not be clearly differentiated from the left kidney. The mass lesion appeared to have surrounded the pancreas from the anterior and posterior and was invading (Fig. 1a–d). The serum tumor markers for α-fetoprotein (AFP), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), and carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19-9) were within the normal ranges. Pathological examination of the core biopsy performed from the mass was reported as a malignant mesenchymal tumor. The patient’s condition was discussed in the multidisciplinary tumor council, and the decision for surgical excision was taken.

Fig. 1.

(a–d) CT scans showing a 20 × 12 cm heterogeneously enhanced lobulated contoured mass lesion in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen, in front of the left kidney, whose borders could not be clearly differentiated from the left kidney. The mass lesion appeared to have surrounded the pancreas from the anterior and posterior and was invading

In the exploratory laparotomy, it was observed that the tumor was originating from the left retroperitoneal region and had invaded the left kidney, the body and tail of the pancreas, the left colon, and the third and fourth parts of the duodenum. The tumor was resected en bloc with left kidney, left colon, the body and tail of the pancreas, and third and fourth parts of duodenum and spleen. Intestinal continuity was achieved by performing duodenojejunostomy and transverso-sigmoidostomy.

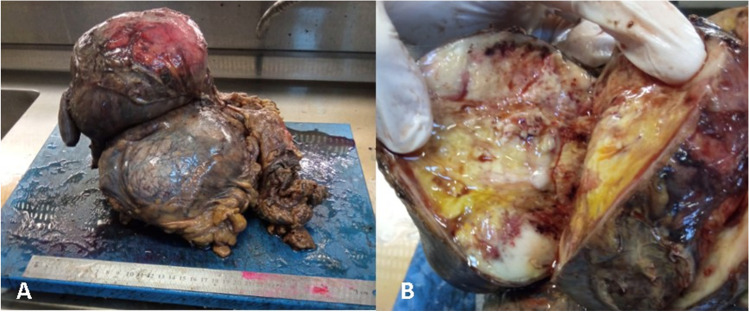

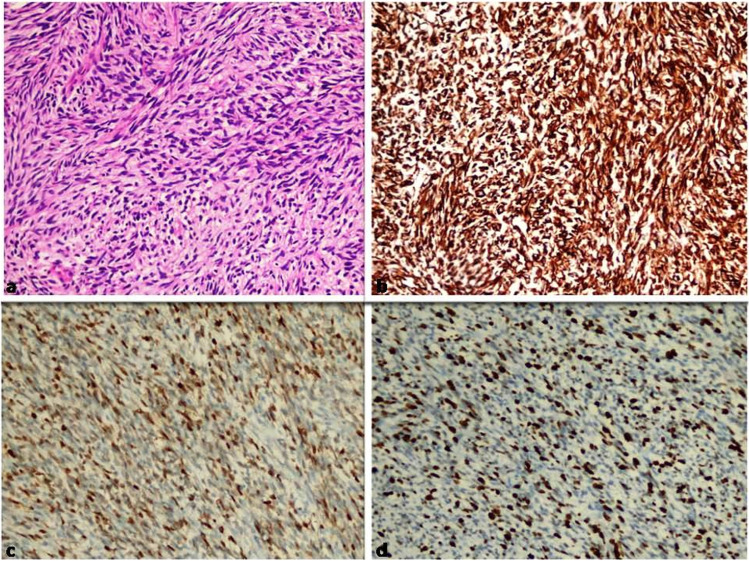

The tumor appeared to have macroscopically invaded the left kidney, left colon, duodenum, and pancreas (Fig. 2a, b). Microscopic evaluation revealed that tumor cells are arranged in fascicles and composed of uniform spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei (Fig. 3a). Necrosis, prominent nuclear pleomorphism, increased cellularity, and high mitotic index were identified. Epithelial tumors and other malignant mesenchymal tumors were considered in differential diagnosis. Performed immunohistochemical stains revealed that neoplastic cells were positive for Vimentin (Fig. 3) and S100 (Fig. 3) while negative for cytokeratin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), Desmin, CD117 (C-kit), CD99, CD34, and SOX10. The Ki-67 proliferation index of the tumor was high (%50–60) (Fig. 3d). According to these results, epithelial tumors, leiomyosarcoma, and malignant gastrointestinal stromal tumor were excluded. Moreover, liposarcoma was considered in differential diagnosis, since it is the most common malignant mesenchymal tumor located in the retroperitoneal region. However, liposarcoma was ruled out by lack of lipoblasts and a proper vascular network. Large neurofibroma or other benign entities such as cellular schwannoma and ancient schwannoma also were considered, but prominent atypia, infiltrative growth pattern, and high mitotic index were not compatible. As a result, the case was diagnosed for high-grade malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPSNT) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

(a, b) The tumor appeared to have macroscopically invaded the left kidney, left colon, duodenum, and pancreas

Fig. 3.

(a) Tumor composed of characterized by uniform spindle cells with hyperchromatic nuclei arranged in fascicles (H&Ex200). (b) Tumor showed diffuse positive staining with vimentin (× 200). (c) Tumor showed positive with focal S-100 (× 200). (d) Tumor showed high Ki-67 proliferation index (× 200)

Discussion

MPNST are rare, highly aggressive tumors that originate from Schwann cells or pluripotent neural crest cells. Although classical MPNST is seen in adults aged 30–60 years, there is no significant difference in incidence between male and female genders [3]. In the literature, there is a case of retroperitoneal MPNST diagnosed at the age of 2 years [4]. MPNST constitute less than 10% of all soft tissue sarcomas and more than 60% develop on the basis of neurofibromatosis (NF) [1]. Ten percent of the patients are cases related to radiotherapy and other causes are not known yet [3, 5]. In the literature, retroperitoneal MPNST without a history of NF or radiation, like our case, is much rarer. Although it mostly occurs in the head and neck region or upper extremities, only 1% of cases are located in the retroperitoneal region. A case of MPNST in the axilla has also been reported [6].

There are no specific symptoms or diagnostic criteria for MPNST. Patients usually admit to the hospital with complaints due to the mass effect in the area where the mass is located. Although there is no specific imaging method or feature for the diagnosis of MPNST, there are publications stating that magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a useful method to distinguish MPNST from neurofibromas [7]. Jia et al. reported a case showing that unexpected 99mTc-DTPA uptake around the kidney on 99mTc-DTPA renal scintigraphy could represent a rare malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor [8].

Retroperitoneal masses constitute a heterogeneous group of lesions, originating in the retroperitoneal space, that pose a diagnostic challenge with view to histology and malignant potential. The majority of cases are malignant tumors, of which approximately 75% are mesenchymal in origin. Primary tumors of the retroperitoneum are mainly lymphoproliferative disorders, soft tissue neoplasms and germ cell tumors. Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) arising in the abdominal cavity usually originate from the gastrointestinal tract and pancreas. NETs found in the retroperitoneum are mainly metastatic. Retroperitoneal paraganglioma usually arise from the adrenal medulla (80–90%), with the remainder (10–20%) arising from the paraaortic region [9].

Before a tumor can be described as primarily retroperitoneal, the possibility that the tumor originates from a retroperitoneal organ must be excluded. Some radiologic signs that are helpful in determining tumor origin include the “beak sign,” the “phantom (invisible) organ sign,” the “embedded organ sign,” and the “prominent feeding artery sign.” When there is no definite sign that suggests an organ of origin, the diagnosis of primary retroperitoneal tumor becomes likely. Among neurogenic tumors, schwannomas are the most common tumor of peripheral nerves. Schwannomas are well encapsulated and contain cells that are identical to Schwann cells. Their MR imaging appearance depends on the types of tissue they contain. Myxoid tissue is hyperintense on T2-weighted images, cellular tissue is hypointense on both T1- and T2-weighted images, and solid fibrous tissue enhances on contrast-enhanced images. Neurofibromas tend to have high signal intensity on T2-weighted MR images and are often multiple and associated with neurofibromatosis. Ganglioneuromas are typically located along the sympathetic chain and tend to be larger, more rounded, and contain calcification more frequently than nerve sheath tumors [10].

Primary retroperitoneal masses originate within the retroperitoneal space, separate from the retroperitoneal organs, and represent a diverse group of neoplasms with often non-specific imaging findings. Familiarity with retroperitoneal anatomy and the radiographic signs to identify an intra-abdominal mass as primary retroperitoneal enable differentiation between primary and secondary masses. The differential diagnosis of primary retroperitoneal masses may be based on the predominant cross-sectional imaging appearance as either cystic or solid and neoplastic and non-neoplastic. Characteristic imaging findings, such as the composition, enhancement pattern, location, and relationship to adjacent structures, may be combined with clinical information to help narrow the differential diagnosis [11].

Most fat-containing retroperitoneal lesions can be characterized on the basis of a patient’s demographics, clinical presentation, and imaging features. When there is any doubt, imaging can guide percutaneous biopsy to obtain tissue for pathologic examination [12].

MPNST are not sensitive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. Therefore, the main treatment option is excision with clear surgical margins [13]. The 5-year survival rates of patients with MPNST who received surgical treatment with and without negative margins were reported 67 and 22%, respectively. However, complete resection with negative margins cannot always be achieved due to unacceptable complications [14]. Our case was treated with multiorgan resection with clear surgical margins.

Although MPNSTs are not very sensitive to radiotherapy, survival and recurrence times were found to be longer in patients who received radiation therapy after surgery. Although it has been advocated in previous studies that patients with > 5 cm, high tumor grade, and positive surgical margins should receive radiotherapy, patients should be selected very carefully. Because radiotherapy increases the risk of developing radiation-related sarcoma, the risk–benefit profile should be carefully discussed for each patient. [14]

A well-planned preoperative examination was necessary to eliminate the risk of inadequate excision and/or damage to adjacent structures. With respect to the surgical approach, surgeons should have a thorough understanding of the anatomical structures of adjacent organs and accompanying vessels. Considering the heterogeneous appearance on imaging and risk of recurrence, en bloc radical excision of the mass is usually recommended, although complete excision of a giant neoplasm is challenging and has a risk of complications. [15]

Conclusion

Retroperitoneal giant MPNSTs are very rare. These lesions can be misdiagnosed as other cystic or solid neoplasms. Complete excision should be considered as the primary treatment. Because of numerous diagnostic and therapeutic issues, the successful treatment of MPNSTs requires detailed preoperative planning and a multidisciplinary approach. Therefore, an initial diagnosis of retroperitoneal MPNSTs is critical for a favorable prognosis. Although retroperitoneal MPNSTs are very rare, they are aggressive tumors. They are not sensitive to chemotherapy and radiotherapy and tend to recur locally. They are diagnosed with symptoms related to the region where they occur, and there is no clear information about their symptoms and recurrence rates. Surgery with clear margins is the main treatment, but due to its invasive nature, it is not always possible to perform R0 surgery. In order to create follow-up and treatment guidelines and to better recognize the disease, quality studies on more cases are needed.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

None

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Türker Acehan, Email: turkeracehan@gmail.com.

Kadir Tomas, Email: kadir_tomas@hotmail.com.

Recep Bedir, Email: bedirrecep@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Agrawal A, Baskaran V, Jaiswal SS, Jayant HB. Would a massive intra-abdominal malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with growth into the inguinal canal and scrotum preclude surgical option? A case report and review of literature. Indian J Surg. 2013;75(6):500–503. doi: 10.1007/s12262-013-0953-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng ZH, Yang YS, Cheng KL, Chen GQ, Wang LP, Li W. A huge malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with hepatic metastasis arising from retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. Oncol Lett. 2012;5(1):123–126. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu M, Liu S, Zhan J, Chen W, Yang P, Zhou H (2020) Case report mixed malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in the inguinal region: a case report. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 13(2):261–265. www.ijcep.com [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Wang J, Yu M, Zhu H, Huang L, Zhu X, Chen C, et al. Retroperitoneal malignant schwannoma in a child. J Int Med Res. 2018;46(10):4315–4322. doi: 10.1177/0300060518787644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martinez AP, Fritchie KJ. Update on peripheral nerve sheath tumors. Surg Pathol Clin. 2019;12(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.path.2018.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kusumoto E, Yamaguchi S, Sugiyama M, Ota M, Tsutsumi N, Kimura Y, et al. Huge epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in the left axilla: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2015;1(1):64. doi: 10.1186/s40792-015-0065-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yotsuya K, Hasegawa T, Yamato Y, Yoshida G, Yasuda T, Banno T, et al. Retroperitoneal neurofibroma and a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with neurofibromatosis type 1: a report of two cases. Spine Surg Relat Res. 2020;4(4):369–373. doi: 10.22603/SSRR.2020-0056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jia X, Gao R, Liang Y, Liang H, Yang A. Retroperitoneal malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor on 99mTc-DTPA renal scintigraphy. Clin Nucl Med. 2019;44(8):648–649. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0000000000002660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marín-Martínez L, Kyriakos G, Sánchez-Gutiérrez D. Pseudotumoral form of schistosomiasis mimicking neuroendocrine tumor: a case report and brief review of the differential diagnosis of retroperitoneal masses. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;37(186):1–8. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2020.37.186.26344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nishino M, Hayakawa K, Minami M, Yamamoto A, Ueda H, Takasu K. Primary retroperitoneal neoplasms: CT and MR imaging findings with anatomic and pathologic diagnostic clues. Radiographics. 2003;23(1):45–57. doi: 10.1148/rg.231025037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scali EP, Chandler TM, Heffernan EJ, Coyle J, Harris AC, Chang SD. Primary retroperitoneal masses: what is the differential diagnosis? Abdom Imaging. 2015;40(6):1887–1903. doi: 10.1007/s00261-014-0311-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shaaban AM, Rezvani M, Tubay M, Elsayes KM, Woodward PJ, Menias CO. Fat-containing retroperitoneal lesions: imaging characteristics, localization, and differential diagnosis. Radiographics. 2016;36(3):710–734. doi: 10.1148/rg.2016150149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.AlQahtani A, AlAli MN, Allehiani S, AlShammari S, Al-Sakkaf H, Arafah MA. Laparoscopic resection of retroperitoneal intra-psoas muscle schwannoma: a case report and extensive literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2020;74:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Du P, Zhu J, Zhang ZD, He C, Ye MY, Liu YX, et al. Recurrent epithelioid malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor with neurofibromatosis type 1: a case report and literature review. Oncol Lett. 2019;18(3):3072–3080. doi: 10.3892/ol.2019.10676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gao C, Zhu FC, Ma BZ, et al. A rare case of giant retroperitoneal neurilemmoma. J Int Med Res. 2020;48(9):0300060520935302. doi: 10.1177/0300060520935302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]