Abstract

Characterizing a pancreatic or periampullary mass lesion as benign or malignant on conventional imaging is difficult due to overlapping morphological features. 18F-FDG PET/CT is a molecular imaging technique with reportedly higher sensitivity and specificity in the differentiation of benign and malignant pancreatic and periampullary masses. In this prospective study, we evaluated the utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with recently diagnosed pancreatic and periampullary masses. Based on FDG uptake pattern, diffuse or absent uptake was considered benign and focal increased uptake as malignant. Among the 32 patients included in the study, pathological examination confirmed 25 as positive for malignancy and the remaining 7 as benign etiology. Based on FDG uptake pattern, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy of the study were 92%, 42.8%, 85.2%, 60%, and 81.3% respectively. 18F-FDG PET/CT had a statistically significant higher detection rate in the evaluation of regional lymph nodes and distant organ metastases compared to radiological imaging. In 7/25 (14%) malignant cases, 18F-FDG PET/CT detected additional distant metastases which were not detected by conventional imaging and thus resulting in change in management from curative resection to palliative therapy. To conculde, 18F-FDG PET/CT uptake pattern can characterize pancreatic and periampullary masses as benign or malignant with a relatively good accuracy. Using 18F-FDG PET/CT for initial staging of pancreatic and periampullary cancer helps in appropriate staging and optimal selection of treatment modality compared to conventional imaging techniques.

Keywords: 18F-FDG PET/CT, Periampullary mass, Pancreatic cancer, Initial staging, Change in management

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer became one of the leading causes of cancer-related mortality with an incidence of 7–9 per 100,000 in men and 5–6.5 per 100,000 in women [1, 2]. It is relatively rare and ranks 13th among all the cancers in incidence rate [3]. But it is very aggressive accounting for 6–7% of all cancer-related deaths and is the fourth most common cause of cancer-related mortality in the world [4].

Periampullary masses include a heterogeneous group of masses which originate from the ampullary epithelium, distal common bile duct, and duodenum surrounding ampulla of Vater. It is often difficult to differentiate and diagnose masses arising from the head of the pancreas from periampullary masses imageologically [5].

Of the various imaging modalities, ultrasonography (USG), computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the main stay of investigations for the initial diagnostic work-up of these patients. These imaging modalities are able to identify abnormalities but are not always able to differentiate malignancy from other benign etiologies like chronic pancreatitis, benign cyst, tuberculosis, autoimmune pancreatitis, etc. [6].

18-Fluoro-2-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (18F-FDG PET/CT) is reported to have higher sensitivity and specificity in the differentiation of benign and malignant pancreatic masses [7]. Also by detecting metastases which are not visualized on routine diagnostic modalities, 18F-FDG PET/CT can result in improved diagnostic and staging work-up and thus reduce surgical morbidity in patients with pancreatic cancer [8].

Malignant cells show increased expression of glucose transporter-I (GLUT-I) on their cell membrane resulting in increased movement of FDG into the cells. In addition, increased hexokinase II expression in these cells along with low glucose-6-phosphatase levels leads to metabolic trapping of FDG within the cancer cells leading to a high target to background ratio [9].

Focal 18F-FDG concentration in tumor can be semi-quantitatively assessed by using standardized uptake value (SUV). The standardized uptake value (SUV) is a well-established semi-quantitative index of metabolic activity in the tumor [10].

Though contrast-enhanced CT is the diagnostic imaging modality of choice for evaluation of pancreatic and periampullary masses, 18F-FDG PET/CT being a whole body imaging survey has the potential to provide additional information about locoregional and distant metastases and therefore can be cost-effective [11].

Material and Methods

This was a prospective clinical study done over a period of 18 months from March 2018 to August 2019 after obtaining approval from the Institute Thesis Protocol Approval Committee and Institute Ethics Committee.

All consecutive patients above 18 years of age with imageologically (USG/CT/MRI) detected pancreatic and periampullary masses referred to the nuclear medicine department for 18F-FDG PET/CT were included in this study. Pregnant women, patients with fasting glucose concentration > 200 mg/dL, and patients who had received any prior treatment were excluded.

Patients with pancreatic or periampullary masses include any solid or cystic lesion causing alteration in the normal contour of the corresponding viscera which was identified by their altered echogenicity or attenuation or signal intensity in USG or CT or MRI respectively. 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed within 2 weeks following the demonstration of lesion by any of the above imaging modalities. While reporting 18F-FDG PET/CT, the nuclear medicine physician was kept blinded to the results of prior imaging findings.

PET/CT Imaging

After an overnight fast (or for at least 4 h), approximately 370 MBq (10 mCi) of 18F-FDG was injected into the patient intravenously. 18F-FDG PET/CT was performed 60 min after injection on a Biograph-6 (SIEMENS) PET/CT scanner with patients in supine position with arms elevated over the head from the skull to the mid-thigh.

PET/CT Interpretation

Diffuse increased FDG uptake in more than one segment of the pancreas or no 18F-FDG concentration was considered benign, and a focal area of increased 18F-FDG uptake was considered malignant. Benign lesion on 18F-FDG PET/CT implies the lesion is non-malignant and includes non-cancerous, cystic, and inflammatory conditions.

Semi-quantitative analysis of 18F-FDG uptake in lesions using maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) is done by drawing a volume of interest (VOI) over the area of the detected lesions with the highest FDG uptake and if there was no increased uptake, VOI was drawn over the lesion detected earlier by conventional imaging.

Statistical Analysis

Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT were calculated considering pathological examination findings as the reference standard. Student’s t test was done to calculate statistical significance between SUVmax values of benign and malignant masses. Statistical significance of 18F-FDG PET/CT in detecting lymph nodes and distant metastases compared to conventional imaging was calculated using McNemar’s test. A p value of < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

A total of 32 patients (16 male and 16 female) were recruited and analyzed in this study. In 9 (28.1%) patients, masses were arising in the periampullary region from either ampulla or distal CBD or duodenum near to ampulla. In the rest of the 23 (71.9%) patients, they were arising from the pancreas forming the group of pancreatic masses.

Pathological Evaluation

In these 32 patients, the pathological diagnosis of lesions was established by FNAC in 5 patients, biopsy in 11 patients, and in the remaining 16 patients who underwent surgery by postoperative histopathological examination.

On pathological examination, 25/32 (78.1%) masses were malignant and the remaining 7/32 (21.9%) masses were benign (Table 1).

Table 1.

Pathological examination findings of the study population

| Site of origin | HPE | No. of patients (n = 32) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Periampullary masses (n = 9) | Ampulla | Ampullary adenocarcinoma | 3 |

| Distal CBD | Cholangiocarcinoma | 3 | |

| Duodenum near ampulla | Duodenal adenocarcinoma | 2 | |

| Duodenal neuroendocrine tumor | 1 | ||

| Pancreatic masses (n = 23) | Head and uncinate process | Adenocarcinoma | 12 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 1 | ||

| Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm | 2 | ||

| Intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN) | 1 | ||

| Body and tail | Adenocarcinoma | 2 | |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 2 | ||

| Chronic pancreatitis | 1 | ||

| Solid pseudopapillary neoplasm | 1 | ||

| Pseudocyst | 1 |

18F-FDG PET/CT Findings

On 18F-FDG PET/CT scan, FDG avidity of the periampullary and pancreatic lesions, range of max.SUV at the primary site and their mean ± SD are described in Table 2 and also individually for each histopathological entity in Table 3.

Table 2.

SUVmax values of primary lesions on 18F-FDG PET/CT

| Origin and type of lesion | n | Mean ± SD | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pancreatic and periampullary masses | Total | 32 | 8.8 ± 4.8 | 0.046 |

| Malignant | 25 | 9.9 ± 4.4 | ||

| Benign | 7 | 6.0 ± 4.3 | ||

| Pancreatic masses | Total | 23 | 8.9 ± 4.3 | 0.028 |

| Malignant | 16 | 10.2 ± 3.8 | ||

| Benign | 7 | 6.0 ± 4.3 | ||

| Periampullary masses | Total | 9 | 8.4 ± 6.1 | –- |

| Malignant | 9 | 8.4 ± 6.1 | ||

| Benign | –- | –- | ||

Table 3.

Mean and range of SUVmax values of primary lesion in each pathological entity

| HPE | n | Max.SUV range | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adenocarcinoma ampulla | 3 | 3.8–19.6 | 12.2 ± 7.9 |

| Adenocarcinoma duodenum | 2 | 5.7–10.9 | 8.8 ± 3.6 |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 3 | 0–12.3 | 5.6 ± 6.2 |

| Adenocarcinoma pancreas | 14 | 3.8–17.4 | 9.7 ± 3.8 |

| NET | 3 | 4.8–9.1 | 6.3 ± 2.4 |

| Chronic pancreatitis | 2 | 2.8–9.7 | 6.2 ± 4.8 |

| SPN | 3 | 6.1–12.9 | 8.5 ± 3.8 |

| IPMN | 1 | 3.9 | - |

| Pseudocyst | 1 | - | - |

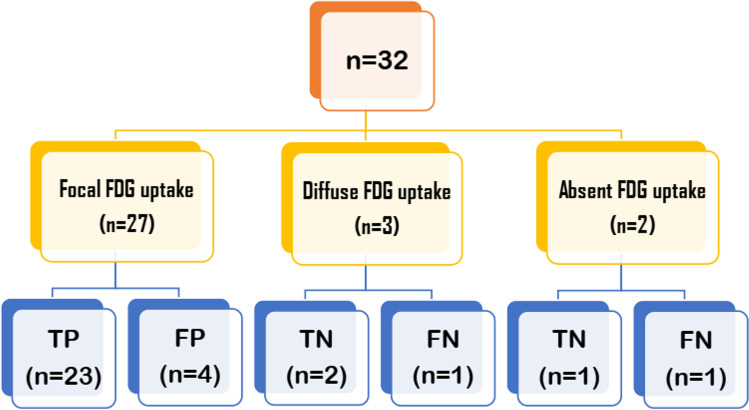

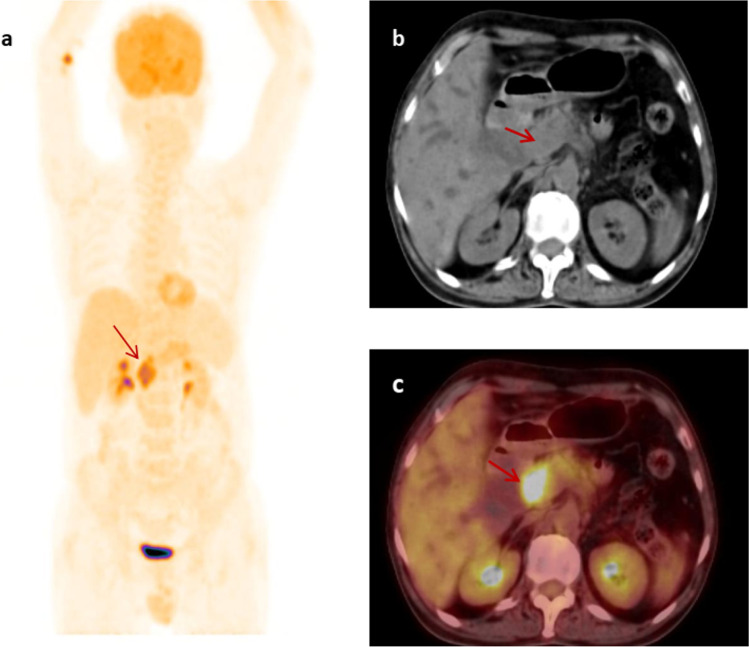

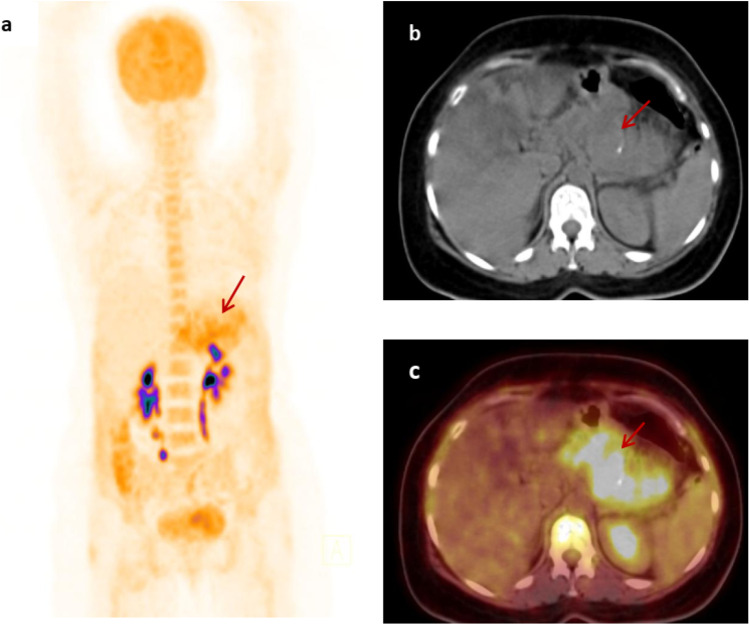

In the present study, 27/32 (84.4%) primary lesions showed focal FDG uptake, 3/32 (9.4%) showed diffusely increased FDG uptake, and 2/32 (6.2%) showed no FDG avidity (Fig. 1). Correlating these findings of 18F-FDG PET/CT based on FDG uptake pattern with that of pathological diagnosis, 23/27 (85.2%) patients who showed focal FDG uptake were found to be true positive for malignancy (Fig. 2) and the remaining 4/27 (14.8%) patients were false positives as they were benign on pathological examination. Two of 3 (66.6%) patients showing diffuse FDG uptake were true negative (Fig. 3) and 1/3 (33.3%) was false negative. Of the two patients with no FDG uptake, 1/2 (50%) was true negative (Fig. 4) and 1/2 (50%) was false negative.

Fig. 1.

Characterization of masses based on FDG uptake pattern. TP true positive, FP false positive, TN true negative, FN false negative

Fig. 2.

Maximum intensity projection (MIP) image (a) and axial (b, c) plain CT and fused PET/CT images respectively of a true positive case showing focal increased 18F-FDG uptake in hypodense lesion in the head of the pancreas with a max.SUV of 9.1 favoring malignant etiology. Postoperative HPE confirmed it as adenocarcinoma

Fig. 3.

MIP image (a) and axial (b, c) plain CT and fused PET/CT images respectively of a true negative case showing diffuse increased FDG uptake in body and tail of pancreas with a max.SUV of 6.3 and a focus of calcification favoring benign etiology. Pathologically, it is confirmed as chronic pancreatitis

Fig. 4.

MIP image (a) and axial (b, c) plain CT and fused PET/CT images respectively of a true negative case showing absent 18F-FDG uptake in hypodense lesion in the body of the pancreas favoring benign etiology. Postoperative HPE confirmed it as pseudocyst

With these findings, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy for 18F-FDG PET/CT in characterizing the periampullary and pancreatic masses into benign and malignant lesions were found to be 92%, 42.8%, 85.2%, 60%, and 81.3% respectively. When it was analyzed for pancreatic masses alone, these parameters were 93.8%, 42.8%, 78.9%, 75%, and 78.3% respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT

| Periampullary and pancreatic masses (n = 32) | Pancreatic masses (n = 23) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 92% | 93.8% |

| Specificity | 42.8% | 42.8% |

| PPV | 85.2% | 78.9% |

| NPV | 60% | 75% |

| Accuracy | 81.3% | 78.3% |

Lesion Detection and Staging

All the 25/32 patients with malignant lesions were staged based on 18F-FDG PET/CT findings and compared with staging done prior by radiological imaging using USG or CT abdomen or MRI (Table 5).

Table 5.

Stage migration post-18F-FDG PET/CT

| S. no | Pre-18F-FDG PET/CT stage | n | Post-18F-FDG PET/CT stage | Upstaging | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA | IB | IIA | IIB | III | IV | ||||

| 1 | IA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (100%) |

| 2 | IB | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 (75%) |

| 3 | IIA | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 (57.1%) |

| 5 | IIB | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 (50%) |

| 6 | III | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 (50%) |

| 7 | IV | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | –- |

| 11 (44%) | |||||||||

Improved detection rate of 18F-FDG PET/CT over radiological imaging was observed in the evaluation of regional lymph nodes (36% vs 16%, p value 0.025), non-regional lymph nodes (20% vs 12%, p value 0.157), and distant organ involvement (36% vs 16%, p value 0.008) (Table 6). In total, upstaging was done in 11/25 (44%) patients.

Table 6.

Lymph nodes and distant organ involvement. S significant, NS not significant

| S. no | Imageological findings | Radiological | 18F-FDG PET/CT | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Regional lymph nodes | 4/25 (16%) | 9/25 (36%) | 0.025 (S) |

| 2 | Non-regional lymph nodes | 3/25 (12%) | 5/25 (20%) | 0.157 (NS) |

| 3 | Distant organs | 7/25 (28%) | 14/25 (56%) | 0.008 (S) |

Impact on Management

Distant metastases were seen in a total of 14/25 (56%) malignant patients on 18F-FDG PET/CT (Table 7). Out of these 14 patients, distant metastases were already previously known by conventional imaging modalities in 7 (28%) patients whereas they were newly identified in the other 7 (28%) patients (Fig. 5). In this group of 7 patients, who were deemed to be resectable after standard work-up, 18F-FDG PET/CT resulted in a change in management to palliative therapy.

Table 7.

Distant organ involvement on 18F-FDG PET/CT

| S. no | Distant organ metastases | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Liver only | 4 (16%) |

| 2 | Bone only | 4 (16%) |

| 3 | Brain only | 1 (4%) |

| 4 | Liver + lung | 1 (4%) |

| 5 | Lung + peritoneum | 1 (4%) |

| 6 | Liver + lung + bone | 1 (4%) |

| 7 | Liver + bone + peritoneum | 1 (4%) |

| 8 | Liver + lung + bone + peritoneum | 1 (4%) |

Fig. 5.

MIP image (a) and axial (b, c) plain CT and fused PET/CT images respectively of a true positive case showing focal increased 18F-FDG uptake in hypodense lesion in the head of the pancreas (red arrows) with a max.SUV of 11.7 favoring malignant etiology. Pathologically, it is confirmed as adenocarcinoma. In addition to it, a solitary hypodense lesion with a rim of increased FDG concentration was noted in the right frontal lobe of the brain (green arrows) with surrounding edema (d, e). Management was changed from curative to palliative therapy

Discussion

Mass lesion in the head of the pancreas can be due to malignancy or secondary to any inflammatory lesion. Hence, pre-operative lesion characterization is very important [12]. 18F-FDG PET/CT is a molecular imaging technique which has significantly changed the diagnostic and management approaches in several malignancies [13]. In pancreatic and periampullary malignancies, 18F-FDG PET/CT is reported to play an important role in initial diagnosis, staging, restaging, and also evaluating the response to treatment [14].

In a meta-analysis, Rijkers et al. reported pooled sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 18F-FDG PET/CT in differentiating pancreatic masses into benign and malignant were 90%, 76%, 89%, and 78% respectively [15]. In the present study, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV of 18F-FDG PET/CT were 92%, 42.8%, 85.2%, and 60% respectively. We observed sensitivity and PPV of our study were comparable to the meta-analysis, but had relatively low specificity and NPV.

In our study, 4 were false positive on PET/CT which includes 3 patients of solid pseudopapillary neoplasm (SPN) and 1 patient of intrapapillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN). Both of these are benign pathologies and presented as focal FDG concentration on 18F-FDG PET/CT.

All the 3 cases of SPN were reported as malignant on PET/CT due to focal increased FDG uptake (Fig. 6). This resulted in reduced specificity of our study as they constituted 42.9% of our benign cases. In a study by Guan et al., focal increased FDG uptake was seen in 13/18 patients with SPN [16]. Increased FDG uptake in SPN was reported to be due to the hypervascularity of the tumor and high density of mitochondria in the tumor cells. Hence, it is difficult to distinguish them from pancreatic cancer on 18F-FDG PET/CT [17].

Fig. 6.

MIP image (a) and axial (b, c) plain CT and fused PET/CT images respectively of a false positive case showing focal increased 18F-FDG uptake in isodense lesion in the tail of the pancreas (red arrows) with a max.SUV of 8.7 favoring malignant etiology based on FDG uptake pattern. But postoperative HPE revealed it as a solid pseudopapillary neoplasm of the pancreas. Symmetrically increased FDG uptake in the bilateral supraclavicular area on the MIP image is due to brown fat uptake (blue arrows)

The other false positive case which showed focal increased FDG uptake was confirmed as IPMN on HPE (Fig. 7). The explanation for focal increased FDG uptake in IPMN is mostly unknown as many PET/CT studies reported excellent specificity of 98–100% in characterizing IPMN [18, 19].

Fig. 7.

MIP image (a) and axial (b, c) plain CT and fused PET/CT images respectively of a false positive case showing increased FDG uptake in large hypodense lesion in the head of the pancreas with a max.SUV of 3.9 favoring malignant etiology based on FDG uptake pattern. But pathological examination revealed it as benign IPMN

Among the 5/32 patients which were considered as benign on PET/CT based on FDG uptake pattern, 2 were false negatives which include cholangiocarcinoma of distal CBD which showed no FDG uptake and another was pancreatic NET which showed diffuse FDG uptake.

In a study of 123 patients with cholangiocarcinoma by Kim et al., most of the false negative cases (13/15, 86.7%) were extrahepatic and infiltrative type. Extrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas often present as an infiltrating type without forming a tumor mass and have a desmoplastic growth pattern due to which FDG concentration is low [20]. This could be the explanation for absent FDG uptake in our case of cholangiocarcinoma in the distal part of CBD.

In the second false negative case which was a pancreatic NET, multiple lesions were located the in head, body, and tail of the pancreas. Most of them coalesced giving an impression of diffuse FDG uptake (Fig. 8). Due to this image appearance, we could not differentiate the mass as benign or malignant based on the uptake pattern. But we observed multiple lymph nodes, liver, lung, peritoneal, and bone metastases suggestive of malignancy.

Fig. 8.

MIP image (a) and axial (b, c) plain CT and fused PET/CT images respectively showing diffusely increased FDG uptake in the pancreas (red arrows) with a max.SUV of 11.2 giving an impression as benign etiology based on FDG uptake pattern. But there were multiple FDG avid regional and non-regional lymph nodes, hypodense lesions in the liver, lytic skeletal lesions, and also lesions in the lung and peritoneum (green arrows) with ascites. Biopsy from the pancreas revealed grade III neuroendocrine tumor

In our study, there was no statistically significant difference in between max.SUV of malignant pancreatic and periampullary masses (p value 0.37) but there was a significant difference in max.SUV of malignant and benign pancreatic masses (p value 0.028) indicating FDG avidity can help in distinguishing malignant from benign masses.

In our study, we compared the findings of the 18F-FDG PET/CT and radiological imaging in the evaluation of regional lymph nodes and distant metastases. We found statistically significant difference in the detection of regional lymph nodes (36% vs 16%, p value 0.025) and distant organ metastases (56% vs 28%, p value 0.008).

Farma et al. studied 82 patients with pancreatic cancer and reported a detection rate of 13% and 9% for regional lymph nodes on 18F-FDG PET/CT and CT abdomen respectively. Lymph nodes were considered to be involved if they were > 1 cm in the short axis [21]. But this factor alone cannot differentiate them as lymph nodes smaller than 1 cm can also be malignant. PET/CT had an advantage over CECT by demonstrating 18F-FDG uptake in equivocal or non-enlarged lymph nodes [22].

In addition to mass lesion characterization and regional lymph node detection, 18F-FDG PET/CT whole body survey detected distant metastases in 56% (14/25) of malignant patients which is 28% higher than CECT. Variable rates of detection of additional metastases on 18F-FDG PET/CT in pancreatic cancer were reported in literature ranging from 8.5 to 29% [8, 11, 23, 24]. Similar to these studies, 28% more cases were detected with distant metastases in our study. This additional detection rate is due to metabolic localization of 18F-FDG and inbuilt whole body imaging ability of PET/CT while CECT was done only for abdominal evaluation [25].

The results of our study indicate the addition of 18F-FDG PET/CT in the routine management of pancreatic and periampullary cancer pre-operatively could result in a change in management from curative resection to palliative chemotherapy in 28% of patients.

Conclusion

The uptake pattern on 18F-FDG PET/CT can characterize pancreatic and periampullary masses as benign or malignant with a relatively good accuracy. Using 18F-FDG PET/CT for initial staging of pancreatic and periampullary cancer helps in appropriate staging and optimal selection of treatment modality compared to conventional imaging techniques.

Limitations

Small sample size. Further studies with a larger sample size are required to validate these results.

Author Contribution

Not applicable.

Funding

The project is funded by Sri Balaji Arogya Vara Prasadini Scheme (SBAVPS), SVIMS.

Data availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The study was performed after obtaining approval from the Institute Thesis Protocol Approval Committee (TPAC No: 413) and Institute Ethics Committee (IEC No: 729).

Consent to Participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Chandra Teja Reddy S, Email: chandratejareddy.dr@gmail.com.

Krishna Mohan V. S, Email: krishna111vs@gmail.com.

Sai Moulika Jeepalem, Email: dr.saimoulika91@gmail.com.

Ranadheer Manthri, Email: ranadheer1502@gmail.com.

Tekchand Kalawat, Email: kalawat.svims@gmail.com.

Venkatarami Reddy V, Email: drvrreddy@rediffmail.com.

Narendra Hulikal, Email: drnarendrah@yahoo.co.in.

Vijaya Lakshmi Devi B, Email: bvijayalakshmidevi@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63(1):11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thapa P. Epidemiology of pancreatic and periampullary cancer. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(5):358–361. doi: 10.1007/s12262-015-1365-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krejs GJ. Pancreatic cancer: epidemiology and risk factors. Dig Dis. 2010;28:355–358. doi: 10.1159/000319414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalady MF, Clary BM, Clark LA, Gottfried M, Rohren EM, Coleman RE, et al. Clinical utility of positron emission tomography in the diagnosis and management of periampullary neoplasms. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:799–806. doi: 10.1007/BF02574503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DeWitt J, Devereaux B, Chriswell M, McGreevy K, Howard T, Imperiale TF, et al. Comparison of endoscopic ultrasonography and multidetector computed tomography for detecting and staging pancreatic cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:753–763. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-10-200411160-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santhosh S, Mittal BR, Bhasin D, Srinivasan R, Rana S, Das A, et al. Role of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in the characterization of pancreatic masses: experience from tropics. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28:255–261. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delbeke D, Rose M, Chapman WC. Optimal interpretation of F-18 FDG imaging of FDG PET in the diagnosis, staging and management of pancreatic carcinoma. J Nucl Med. 1999;40:1784–1792. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pauwels EK, Sturm EJ, Bombardieri E, Cleton FJ, Stokkel MP. Positron-emission tomography with [18F] fluorodeoxyglucose - part I. Biochemical uptake mechanism and its implication for clinical studies. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2000;126:549–59. doi: 10.1007/PL00008465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paesmans M, Berghmans T, Dusart M, Garcia C, Hossein-Foucher C, Lafitte JJ, et al. Primary tumor standardized uptake value measured on fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography is of prognostic value for survival in non-small cell lung cancer: update of a systematic review and meta-analysis by the European Lung Cancer Working Party for the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer Staging Project. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:612–619. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d0a4f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heinrich S, Goerres GW, Schafer M. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography influences on the management of resectable pancreatic cancer and its cost-effectiveness. Ann Surg. 2005;242:235–243. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000172095.97787.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dutta AK, Chacko A. Head mass in chronic pancreatitis: inflammatory or malignant. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;7(3):258–264. doi: 10.4253/wjge.v7.i3.258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperti C, Pasquali C, Decet G. F-18-fluoro-deoxyglucose positron emission tomography in differentiating malignant from benign pancreatic cysts: a prospective study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;16:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahani DV, Bonaffini PA, Catalano OA, Guimaraes AR, Blake MA. State-of-the-art PET/CT of pancreas: current role and emerging indications. Radiographics. 2012;32:1133–1158. doi: 10.1148/rg.324115143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rijkers AP, Valkema R, Duivenvoorden HJ, van Eijck CH. Usefulness of F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography to confirm suspected pancreatic cancer: a meta-analysis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:794–804. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guan ZW, Xu BX, Wang RM, Sun L, Tian JH. Hyperaccumulation of (18)F-FDG in order to differentiate solid pseudopapillary tumors from adenocarcinomas and from neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors and review of the literature. Hell J Nucl Med. 2013;16:97–102. doi: 10.1967/s002449910084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Teja Reddy SC, Reddy VV, Bhargavi D, Deepthi B, Tammineni S, Manthri R, Kalawat T. Synchronous pancreatic solid pseudopapillary neoplasm masquerading as extralymphatic involvement on 18F-fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography in a case of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Indian J Nucl Med. 2019;34(4):309–312. doi: 10.4103/ijnm.IJNM_113_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bertagna F, Treglia G, Baiocchi GL, Giubbini R. F18-FDG-PET/CT for evaluation of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms (IPMN): a review of the literature. Jpn J Radiol. 2013;31:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s11604-012-0176-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hong HS, Yun M, Cho A, Choi JY, Kim MJ, Kim KW, et al. The utility of F-18 FDG PET/CT in the evaluation of pancreatic intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm. Clin Nucl Med. 2010;35:776–779. doi: 10.1097/RLU.0b013e3181e4da32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim JY, Kim MH, Lee TY, Hwang CY, Kim JS, Yun SC, et al. Clinical role of 18F-FDG PET-CT in suspected and potentially operable cholangiocarcinoma: a prospective study compared with conventional imaging. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:1145–1151. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farma JM, Santillan AA, Melis M, Walters J, Belinc D, Chen DT, et al. PET/CT fusion scan enhances CT staging in patients with pancreatic neoplasms. Annals of Surg Oncol. 2008;15(9):2465–2471. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9992-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jha P, Bijan B. PET/CT for pancreatic malignancy: potential and pitfalls. J Nucl Med Technol. 2015;43:92–97. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.114.145458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kauhanen SP, Komar G, Seppanen MP, Dean KI, Minn HR, Kajander SA, et al. A prospective diagnostic accuracy study of 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography, multidetector row computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in primary diagnosis and staging of pancreatic cancer. Ann Surg. 2009;250:957–963. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b2fafa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bang S, Chung HW, Park SW, Chung JB, Yun M, Lee JD, et al. The clinical usefulness of 18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in the differential diagnosis, staging, and response evaluation after concurrent chemoradiotherapy for pancreatic cancer. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:923–929. doi: 10.1097/01.mcg.0000225672.68852.05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asagi A, Ohta K, Nasu J, Tanada M, Nadano S, Nishimura R, et al. Utility of contrast-enhanced FDG-PET/CT in the clinical management of pancreatic cancer: impact on diagnosis, staging, evaluation of treatment response, and detection of recurrence. Pancreas. 2013;42:11–19. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3182550d77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Not applicable.