Abstract

Objectives

According to international observations, the incidence of clinical autopsies is declining worldwide, plummeting below 5% in the USA and many European countries. It is an unfavourable trend as, in 7%–12% of cases, recent clinicopathological studies found discrepancies that might have changed the therapy or the outcome if known premortem. As previous large-scale observations have examined varied patient populations, we aimed to focus on the differences between the clinical and pathological diagnostic findings in only patients who had a stroke.

Material and methods

We assessed the postmortem non-neuropathological and neuropathological findings of 534 consecutive patients who had a stroke who passed away. Systemic neoplasms, pneumonias, thromboembolisms and haemorrhagic transformations revealed only by autopsy were considered severe abnormalities; in addition, benign abnormalities important from an educational or scientific point of view were also recorded.

Results

In 26 of the 534 cases (4.9%), the presence of systemic neoplasms had already been confirmed in the clinical stage; however, 8 (1.5%) malignant tumours were only detected during autopsy. Also, 80 (15%) thromboembolic events, 73 (13.6%) pneumonias and 66 (18%) haemorrhagic transformations were only diagnosed at autopsy. Longer hospital stay (from admission to death) resulted in fewer discrepancies between clinical and autopsy diagnosis of thromboembolic events and pneumonias (p<0.01). In 169 cases, benign findings were detected.

Conclusions

While the type of acute stroke is reliably diagnosed with imaging techniques, postmortem autopsies are also important in patients who had a stroke as autopsies may reveal clinically silent diseases (eg, tumour), and contribute to knowing the actual incidence of stroke-related thromboembolic and pneumonia complications.

Keywords: stroke, complication, CT, autopsy

Introduction

The autopsy is the ultimate medical tool used not only to confirm the diagnosis and the appropriateness of the treatment, but also to inform us about what happened between the last clinical examination and the patient’s death. While in the last century, the primary purpose of the autopsy was to reveal what disease had led to the patient’s death, today it is the final and most reliable means for the assessment of treatment effectiveness and side effects, and the analysis of hospital-acquired infections. Also, autopsy continues to play an essential role in the training of medical students, and provides considerable opportunities for advancements in science.

Although these facts are all in favour of traditional autopsy, the rate of autopsied deaths is declining worldwide; the rate is below 5% in the USA, as well as several European countries. This declining trend is worrying: as several scientific societies including the American Society for Quality, Association of Directors of Anatomic and Surgical Pathology1 pointed out, the decrease of autopsies undermines the reliability of epidemiological data, and the controllability of the quality of clinical diagnosis and therapy; also, it adversely affects the education of medical students and limits scientific research. The distortion of mortality statistics is well exemplified by the fact that the cause of out-of-hospital sudden death is most often considered to be of cardiovascular origin; however, as it has been observed in autopsied cases, approximately one-third of these deaths is caused by some other disease.2 3 Since most clinicopathological analyses found in literature reviewed highly varied patient populations, we decided to focus on the postmortem and clinical findings of a more specific population, and examined more than half thousand patients who had an acute stroke.

Material and methods

The stroke unit of the Department of Neurology at the University of Debrecen Clinical Center was founded in 1969, and was the second such unit established in Europe. Its catchment area has not changed since its foundation; and the unit treats 750–840 patients who had a stroke annually. Patients who had an acute stroke are transported directly to the CT laboratory, and the neurologist examines the patient in the CT room. After that, the treatment of the patient is continued in the intensive stroke unit of the Department of Neurology, near the CT laboratory.

In the present study, we compared the postmortem non-neuropathological and postmortem neuropathological findings of 534 consecutive patients who had a stroke who passed away over a period of 10 years and their summaries of the clinical course. The autopsy rate at our clinic was quite high, around 80% in the studied period, which is due to the requirements of the Hungarian health regulations. These regulations state that an autopsy of the deceased does not have to be performed only in cases when all of the following conditions exist: the clinical course and the cause of death can be determined unambiguously by the clinician, and no further significant findings can be expected of an autopsy, and based on the summary of the hospital course the pathologist also deems it unnecessary, and a family member requests that no autopsy be performed.4

In addition to the autopsy of thoracic, abdominal and pelvic organs, body and brain autopsy also included that of the carotids and femoral arteries; and specimens were sliced from the brain after 1 week of formalin fixation. The autopsy practice was in line with the institutional standardised operating procedure, which was in consistent with the latest international standards, and was supervised by senior university consultants. The major requirements are regulated by the regularly reviewed documents of the Department of Pathology at the Clinical Center of the University of Debrecen (document no. SZ024/Chapter 5.2, last revised on 1 September 2021).

Brain autopsies were performed by a neuropathologist. During the comparison of clinical and autopsy diagnoses, we relied on the Goldman et al categories.5 If the summary of the hospital course did not mention a malignancy, pneumonia or a thromboembolic event, but later such an event was detected at autopsy, these abnormalities were classified as class I discrepancies because awareness of their presence would have indicated the initiation of some additional treatment, for example, anticancer, antibiotic or antithrombotic therapy. When we found haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct at autopsy, and only an ischaemic lesion on the last premortem CT scan, we also regarded it as class I discrepancy. Class II postmortem non-neuropathological finding discrepancies included the ones observed when the summary of the hospital course did not mention the diagnosis of a thromboembolic event or pneumonia, but the patients received antithrombotic or antibiotic treatment for some other reasons, for example, prophylaxis. Class III refers to scientifically/educationally useful findings, the knowledge of which would not have altered the treatment. As in addition to cerebral pathology, the outcomes of our patients who had a stroke are also determined by complications (pneumonia and thromboembolic diseases), during the comparison of clinical and autopsy data we focused primarily on these diseases. We also analysed the effect of gender, age and length of hospital stay on the discrepancies between the clinical and autopsy findings. Continuous variables of clinical data were characterised by mean and SD, and percentage distributions were calculated for categorical variables. As it was a univariate analysis, we evaluated the potential associations between categorical variables using Χ2 test. Intercooled Stata V.13 software was used for the analyses.

Postmortem non-neuropathological findings

In 26 (4.9%) out of the 534 cases we studied, systemic tumours had been diagnosed already in the clinical phase, but 8 malignancies were only diagnosed during the autopsy (1.5%). Of the eight patients with malignant tumours (diagnosed by autopsy), three patients died due to parenchymal haemorrhage, and five died due to cardiorespiratory insufficiency, pneumonia or myocardial infarction (table 1).

Table 1.

Thromboembolic complications and direct cause of death in patients who had a stroke with malignancy, based on autopsy findings

| Age and sex | Tumour (histopathology) |

Thromboembolic findings (autopsy) |

Premortem antithrombotic therapy | History of thromboembolic event | Cause of death |

| 76 years female | Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (not otherwise specified type), with metastatic lymph nodes | No | No | Yes (history of deep vein thrombosis) |

Myocardial infarction |

| 69 years female | Colon adenocarcinoma (mucinous type) | No | No | No | Pneumonia |

| 67 years male | Invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the lung, keratinising | No | No | No | Brainstem compression due to parenchymal haemorrhage |

| 62 years female | Papillary thyroid cancer | No | No | No | Brainstem compression due to parenchymal haemorrhage |

| 66 years female | Papillary renal cell carcinoma | No | Yes | Yes (history of myocardial infarction) |

Cardiorespiratory insufficiency |

| 78 years female | Papillary urothelial carcinoma, invasive (pelvic and ureteral), with metastatic lymph nodes | No | No | No | Brainstem compression due to parenchymal haemorrhage |

| 78 years female | Follicular thyroid carcinoma | No | No | No | Myocardial infarction |

| 66 years female | Colon tumour (histological examination was not performed) | Yes | No | No | Cardiorespiratory insufficiency |

During the 534 autopsies, thromboembolic events and pneumonia (not found in the final clinical diagnosis) were detected in 80 (15%) and 73 cases (13.6%), respectively (table 2).

Table 2.

Discrepancies between postmortem non-neuropathological findings and clinical diagnoses, and discrepancies between postmortem neuropathological findings and the last premortem CT scan

| Discrepancy | Postmortem non-neuropathological findings Number (N)=534 |

| Class I discrepancy | 8 (1.5%) malignancies 68 cases of (12.7%) thromboembolic events: in vivo non-diagnosed thrombosis in the femoral vein or in the periprostatic and periuterine venous plexus, embolus in the lung—without any antithrombotic therapy 36 cases of (6.7%) in vivo non-diagnosed pneumonia, without any antibiotic therapy |

| Class II discrepancy | 12 cases of (2.3%) thromboembolic events: in vivo non-diagnosed thrombosis in the femoral vein or in the periprostatic and periuterine venous plexus, embolus in the lung—with prophylactic antithrombotic therapy 37 cases of (6.9%) in vivo non-diagnosed pneumonia, but prophylactic antibiotic therapy |

| Class III discrepancy | 169 (31.6%) benign findings (cysts, myoma, etc) |

|

Postmortem neuropathological findings in patients with ischaemia

Number (N)=189 |

|

| Class I discrepancy | 66 (34.9%) ischaemic lesions on the premortem CT scan, but haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct on brain autopsy |

Thromboembolic events including pulmonary embolism, lower limb thrombosis, and thrombosis in the periprostatic or periuterine venous plexus could be diagnosed in 160 of the 534 cases (either premortem or during the autopsy) (table 3).

Table 3.

Premortem-diagnosed and postmortem-diagnosed thromboembolic events (thrombosis in the femoral vein or in the periprostatic or periuterine venous plexus, embolus in the lung)

| Number of patients | Antithrombotic therapy | Length of hospital stay (from admission until death) | |

| Premortem-diagnosed thromboembolic events | 80 | 31* | 13.0 (8.0–21.0) |

| Postmortem-diagnosed thromboembolic events | 80 | 12† | 8.0 (5.0–13.0) |

*Forty-nine patients did not receive antithrombotic therapy (eg, due to the risk of haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct, enlargement of parenchymal haemorrhage, concomitant systemic bleeding, etc).

†Sixty-eight patients were not administered antithrombotic treatment partly due to the lack of clinical symptoms, and partly due to the fear of haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct and the fact that they had large parenchymal haemorrhage and terminal state.

We analysed whether the patients’ age and gender influenced the likelihood of discrepancies, and found that neither their age nor gender affected the incidence of discrepancies; nevertheless, prolonged clinical stay reduced the likelihood of a pneumonia or thromboembolic event going unrecognised until death (table 4).

Table 4.

Age differences between patients with cancer, thrombosis/embolus and pneumonia diagnosed by the pathologist and the clinician

| Median (IQR), year | P value | |

| Malignancy diagnosed only at autopsy (N=8) | 68.0 (62.0–68.0) | 0.839 |

| Malignancy diagnosed by clinicians (N=26) | 70.5 (63.0–76.0) | |

| Thromboembolic event diagnosed only at autopsy (N=80) | 72.5 (62.5–80.0) | 0.142 |

| Thromboembolic event diagnosed by clinicians (N=80) | 75.0 (69.0–81.0) | |

| Pneumonia diagnosed only at autopsy (N=73) | 71.0 (60.0–79.0) | 0.116 |

| Pneumonia diagnosed by clinicians (N=262) | 73.0 (65.0–81.0) |

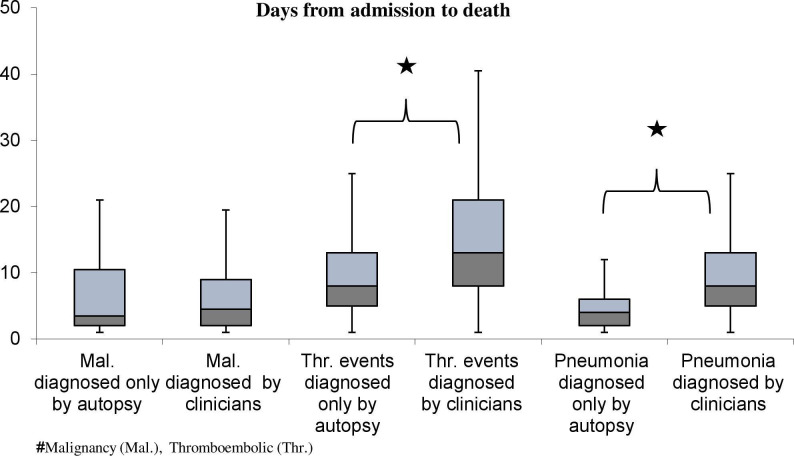

We also examined whether the length of hospital stay had any effect on the detection of tumours, thromboembolic events or pneumonia in the clinical phase (figure 1). The patients whose thromboembolic event (13.0 (8.0–21.0)) or pneumonia (8.0 (5.0–13.0)) had already been diagnosed by clinicians spent significantly longer time at the clinic, compared with the patients whose conditions were only diagnosed by the pathologist (8.0 (5.0–13.0) days in thromboembolic events, 4.0 (2.0–6.0) days in pneumonia).

Figure 1.

Length of hospital stay (from admission to death) of patients with tumours, thromboembolic events or pneumonia diagnosed by pathologists and clinicians. Significant differences between patients with thromboembolism and pneumonia (p<0.01). There was no significant difference in the treatment time of patients with malignancies diagnosed by the clinicians, and the patients whose tumour was diagnosed at autopsy.

Postmortem neuropathological findings

Looking for a relationship between postmortem neuropathological findings results and the immediate cause of death, we found that pneumonia and pulmonary embolism were the most common causes of death in patients with ischaemic lesions or haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct (table 5).

Table 5.

The relationship between postmortem neuropathological findings and the immediate cause of death

| Cause of death (autopsy diagnosis) |

Postmortem neuropathological findings | |||

| Ischaemic lesions N=222 |

Haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct N=99 |

Parenchymal haemorrhage N=172 |

Subarachnoid haemorrhage N=41 |

|

| Herniation (eg, due to haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct or expansion of bleeding) |

31 | 18 | 118 | 32 |

| Cardiorespiratory insufficiency | 44 | 23 | 14 | 2 |

| Myocardial infarction | 11 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 81 | 31 | 24 | 6 |

| Pulmonary embolism | 55 | 22 | 12 | 1 |

| Sepsis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

Comparison between the result of the postmortem neuropathological findings and the last premortem CT scan was possible in 189 ischaemic stroke cases. Sixty-six patients (34.9%) had ischaemia on the last premortem CT scan, while autopsy revealed haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct (class I) (table 2). These patients (66) had a significantly shorter premortem period (6.0 (4.0–10.0) days) compared with those (123 patients) without a haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct at autopsy (11 (6.00–17.00) days, p<0.01).

We compared the platelet count of the group of patients with ischaemia with haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct at autopsy (261.66 G/L, 95% CI (240.70 to 282.62)) with the count of the group whose findings showed ischaemia at autopsy, too (270.38 G/L, 95% CI (253.33 to 287.43)), and found no significant difference. No further haemostasis parameters were available for comparison. Our further novel autopsy findings are listed in table 6.

Table 6.

Findings in the carotid and the vertebrobasilar system observed at brain autopsy

| Brain autopsy findings | N=534 |

| Thrombus in the internal carotid artery | 27 (5%) |

| Hyaline degeneration of the basilar/vertebral artery | 113 (21%) |

| Mild atherosclerosis of the basilar/vertebral artery | 57 (11%) |

| Moderate atherosclerosis of the basilar/vertebral artery | 137 (26%) |

| Severe atherosclerosis of the basilar/vertebral artery | 8 (28%) |

| Basilar/vertebral artery aneurysm | 28 (5%) |

| Thrombus in the basilar artery | 13 (2%) |

| Dissection in the basilar artery/internal carotid artery | 0 |

Discussion

The key message of our study is that even in stroke, when the diagnosis can be established almost immediately with the help of a CT or MRI scan, postmortem autopsy can reveal not only a concurrent disease (eg, systemic tumour), but uncommon causes of stroke as well (eg, paraneoplastic stroke). In addition, this way we can get a more comprehensive picture of the incidence of stroke complications (thrombosis, embolism, pneumonia) and the immediate cause of death. As relatives often object conventional autopsy due to religious or other reasons, new techniques including postmortem angiography, CT, MRI, endoscopy, virtual autopsy and needle autopsy have been developed and introduced.6 The new postmortem techniques can give insights into circumscribed disease processes, and can also provide clues to causes of death; however, their use cannot provide a complete pathogenetic account of disease processes. At present, there are various techniques of postmortem examination that can supplement but not replace conventional autopsy; in addition, their widespread use is hampered by the costs involved.7 8 In our study, the performed autopsy managed to detect malignancies, thromboembolism and pneumonia in 1.5%, 15%, and 13.6% of the cases, respectively. Our observations underline the importance of autopsies in an age when, despite all rational considerations, the number of clinical autopsies is declining dangerously. Of the 700 000 Americans who died in hospitals throughout the USA in 1 year, only 28 000 patients underwent autopsies.9

A recent report10 has found that the incidence of serious errors (affecting outcome or treatment) was nearly 10%. Similar findings were published by Tejerina et al, who reviewed the reports of 834 autopsies, and found a severe (class I–II) discrepancy in 19% of the cases.11 The discrepancy between the clinical and the autopsy findings is not limited to countries with lower quality healthcare. British authors compared the results of 448 clinical summaries and autopsies,12 and found that the sensitivity of clinical summaries (defined as an agreement between the autopsy-confirmed disease and the clinical opinion) was only 47%.

A JAMA review of 53 studies found that in an average US healthcare facility, the incidence of major clinical errors (primary cause of death) ranges from 8.4% to 24.4%, while the incidence of class I errors (affecting outcome) is between 4.1% and 6.7%.13 According to a meta-analysis that analysed the autopsy results of patients treated at an intensive care unit (ICU) (31 studies were reviewed, including a total of 5863 autopsies), 8% of patients had class I and 18% had class II discrepancies, despite the fact that a wide range of diagnostic tools were available in ICUs.14 The authors hypothesised that 34 000 ICU patients die each year due to class I discrepancies in the USA, assuming that the identified class I error was the cause of their death. We would expect the development of clinical diagnostics to minimise the discrepancies between clinical and pathological diagnostics; unfortunately, publications do not fully confirm this theory. Swiss authors compared diagnostic errors before and after 1992 based on autopsies on internal medicine patients. Although the rate of major diagnostic errors decreased from 30% to 7% over time (in 20 years), this number is still high.15

Wittschieber et al analysed data from more than 1800 autopsies conducted in Berlin between 1988 and 2008 and found that the 25.8% incidence of class I discrepancies observed in 1988 decreased significantly to 10.7% by 2008; the frequency of class III discrepancies increased from 13.7% to 27%, though.16 Major discrepancies (class I+II combined) decreased from 43.4% to 27.1%, but the rate of minor discrepancies (class III+IV) increased significantly, from 16.4% to 33.0%. Hospital costs are rising worldwide; therefore, all specialties are focusing on performing specialty-specific examinations only, which in the case of stroke still includes expensive imaging examinations. This worldwide practice may lead to asymptomatic, non-central nervous system tumours remaining undetected in vivo; at the same time, as paraneoplastic complications, systemic tumours can provoke cerebral ischaemia by affecting the coagulation cascade. According to literature, 3%–5% of patients were diagnosed with a malignancy after suffering an ischaemic stroke.17 18 On the basis of their calculations, Navi and Iadecola assumed that 10% of patients who had an ischaemic stroke might be diagnosed with a malignancy, and observed that the most common tumours in patients who had a stroke are lung, gastrointestinal and breast tumours.19 However, we found fewer malignancies in our material (4.9% had already been diagnosed by clinicians and 1.5% were only found postmortem) compared with the above literature findings. The lower tumour incidence in our study is presumably explained by the fact that instead of focusing on the incidence of stroke in patients with malignancies, like Navi and Iadecola, our analysis assessed the prevalence of systemic tumours in patients who had a stroke with a fatal outcome. In our opinion, this might be a reasonable explanation for the 4.9%+1.5% rate we observed.

The prognosis of patients who had a stroke is also influenced (beside the severity of the ischaemic/haemorrhagic lesion) by complications like pneumonia and thromboembolic events, which affect not only mortality, but also survivors’ chances for a good recovery. According to a US study, 47% of critically ill patients who had a stroke develop pneumonia.20 In a clinical study of more than 11 000 patients who had a stroke, 30-day mortality was six times higher in patients with pneumonia compared with those without (26.9% vs 4.4%; p<0.001).21 According to the autopsy-based observations of Bounds et al, the cause of death in 29% of patients with acute ischaemic stroke was pneumonia, while clinicians diagnosed pneumonia in only 11% of the patients.22 Thromboembolic processes are well-known complications in bedridden patients who had a stroke. Bounds et al observed that clinicians recorded pulmonary embolism as the cause of death in only 2% of the cases, whereas autopsy confirmed it in 13% of patients.22 In our study, we noted a similar number of clinically undetected pneumonia (14%) and thromboembolic complications (15%).

We could not find any previous studies evaluating the correlations between age, gender and clinicopathological discrepancies to compare our results with. In our study, we have not found age or gender-dependent differences in the frequency of discrepancies; nevertheless, we found the duration of hospital stay to be significantly shorter in patients whose pneumonia and thromboembolic events failed to be diagnosed premortem. Our observation underlines the necessity to perform all possible non-invasive examinations (eg, imaging examinations, including chest CT and ultrasound; and blood tests for C reactive protein and D-dimer) for the early detection of infection or venous thrombosis in patients who had an acute stroke to ensure timely implementation of adequate therapy.

Stroke specialists need to consider several aspects when making a therapeutic decision. On the one hand, bedridden patients are at an increased risk of thromboembolic events; on the other hand, antithrombotic treatment increases the risk of systemic bleeding and the haemorrhagic transformation of ischaemic stroke. In autopsy reports, the frequency of spontaneous haemorrhagic transformation in ischaemic stroke ranges from 38% to 71%.23 The incidence rate reported in literature only depends on whether CT-reported transformations (13%–43%) or asymptomatic/symptomatic cases (0.6%–20%) were considered.24 25 In an earlier autopsy study conducted at our clinic (in 64 patients with cerebral ischaemia), we found haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct in 38% of the patients.26 This proportion was similar in the present study (in over half thousand patients): we found a rate of 35%. A haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct increases both early and late mortality after ischaemic stroke.27

We found shorter hospital stay until death in patients with haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct (6.0 (4.0–10.0) days) compared with patients who had an ischaemic stroke without haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct at autopsy (11 (6.00–17.00)).

In summary, we have demonstrated on a homogeneous population of patients who had a stroke that traditional body and brain autopsy can provide not only new diagnostic information about clinically non-detected systemic diseases (tumours) but also precise data about stroke or therapy-related complications and the underlying cause of death. Autopsy of the brain, among others, assesses the exact incidence of haemorrhagic transformation of an infarct. Therefore, we sincerely believe that even at the beginning of the 21st century, autopsy is still the ultimate tool of quality control in medicine, and the old saying ‘Mortui docent vivos’ (the dead teach the living) remains to be true.

Footnotes

Contributors: LH, AN and LC participated in designing the study, collecting data, analysing the data and writing the paper. KEN, LH and SM were responsible for data collection and processing. AN did statistical analysis. LC, GM and LO made critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. LC, LO and GM were responsible for study supervision and organisation of the project. LC accepts full responsibility for the finished work and the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: Supported by grants from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund (K120042), by GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00048 (Stay Alive), ELKH-DE Cerebrovascular and Neurodegenerative Research Group.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information. Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, LC (University of Debrecen Faculty of Medicine Department of Neurology, csiba@med.unideb.hu), upon reasonable request.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

Our study was conducted with the University of Debrecen Ethics Committee permission (no. H.0265–2020).

References

- 1. Association of Directors of Anatomic Surgical Pathology, Nakhleh R, Coffin C, et al. Recommendations for quality assurance and improvement in surgical and autopsy pathology. Am J Clin Pathol 2006;126:337–40. 10.1309/2TVBY2D8131FAMAX [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Buja LM, Barth RF, Krueger GR, et al. The importance of the autopsy in medicine: perspectives of pathology colleagues. Acad Pathol 2019;6:237428951983404. 10.1177/2374289519834041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shojania KG, Burton EC, McDonald KM, et al. Overestimation of clinical diagnostic performance caused by low necropsy rates. Qual Saf Health Care 2005;14:408–13. 10.1136/qshc.2004.011973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Act CLIV of 1997 on health, 2021. Available: https://www2.ohchr.org/english/bodies/cescr/docs/E.C.12.HUN.3-Annex10.pdf

- 5. Goldman L, Sayson R, Robbins S, et al. The value of the autopsy in three medical eras. N Engl J Med 1983;308:1000–5. 10.1056/NEJM198304283081704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eriksson A, Gustafsson T, Höistad M, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of postmortem imaging vs autopsy-A systematic review. Eur J Radiol 2017;89:249–69. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2016.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bolliger SA, Filograna L, Spendlove D, et al. Postmortem imaging-guided biopsy as an adjuvant to minimally invasive autopsy with CT and postmortem angiography: a feasibility study. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;195:1051–6. 10.2214/AJR.10.4600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. van den Tweel JG, Wittekind C. The medical autopsy as quality assurance tool in clinical medicine: dreams and realities. Virchows Arch 2016;468:75–81. 10.1007/s00428-015-1833-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Goldman L. Autopsy 2018: still necessary, even if occasionally not sufficient. Circulation 2018;137:2686–8. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marshall HS, Milikowski C. Comparison of clinical diagnoses and autopsy findings: six-year retrospective study. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2017;141:1262–6. 10.5858/arpa.2016-0488-OA [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tejerina E, Esteban A, Fernández-Segoviano P, et al. Clinical diagnoses and autopsy findings: discrepancies in critically ill patients*. Crit Care Med 2012;40:842–6. 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236f64f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sington JD, Cottrell BJ. Analysis of the sensitivity of death certificates in 440 Hospital deaths: a comparison with necropsy findings. J Clin Pathol 2002;55:499–502. 10.1136/jcp.55.7.499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shojania KG, Burton EC, McDonald KM, et al. Changes in rates of autopsy-detected diagnostic errors over time: a systematic review. JAMA 2003;289:2849–56. 10.1001/jama.289.21.2849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Winters B, Custer J, Galvagno SM, et al. Diagnostic errors in the intensive care unit: a systematic review of autopsy studies. BMJ Qual Saf 2012;21:894–902. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schwanda-Burger S, Moch H, Muntwyler J, et al. Diagnostic errors in the new millennium: a follow-up autopsy study. Mod Pathol 2012;25:777–83. 10.1038/modpathol.2011.199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wittschieber D, Klauschen F, Kimmritz A-C, et al. Who is at risk for diagnostic discrepancies? comparison of pre- and postmortal diagnoses in 1800 patients of 3 medical decades in East and West Berlin. PLoS One 2012;7:e37460. 10.1371/journal.pone.0037460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cocho D, Gendre J, Boltes A, et al. Predictors of occult cancer in acute ischemic stroke patients. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2015;24:1324–8. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2015.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Selvik HA, Thomassen L, Bjerkreim AT, et al. Cancer-Associated stroke: the Bergen NORSTROKE study. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra 2015;5:107–13. 10.1159/000440730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Navi BB, Iadecola C. Ischemic stroke in cancer patients: a review of an underappreciated pathology. Ann Neurol 2018;83:873–83. 10.1002/ana.25227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Upadya A, Thorevska N, Sena KN, et al. Predictors and consequences of pneumonia in critically ill patients with stroke. J Crit Care 2004;19:16–22. 10.1016/j.jcrc.2004.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katzan IL, Cebul RD, Husak SH, et al. The effect of pneumonia on mortality among patients hospitalized for acute stroke. Neurology 2003;60:620–5. 10.1212/01.WNL.0000046586.38284.60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bounds JV, Wiebers DO, Whisnant JP, et al. Mechanisms and timing of deaths from cerebral infarction. Stroke 1981;12:474–7. 10.1161/01.STR.12.4.474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Zhang J, Yang Y, Sun H, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation after cerebral infarction: current concepts and challenges. Ann Transl Med 2014;2:81. 10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2014.08.08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jaillard A, Cornu C, Durieux A, et al. Hemorrhagic transformation in acute ischemic stroke. The MAST-E study. MAST-E group. Stroke 1999;30:1326–32. 10.1161/01.str.30.7.1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bang OY, Saver JL, Kim SJ, et al. Collateral flow averts hemorrhagic transformation after endovascular therapy for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke 2011;42:2235–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Szepesi R, Csokonay Ákos, Murnyák B, et al. Haemorrhagic transformation in ischaemic stroke is more frequent than clinically suspected - A neuropathological study. J Neurol Sci 2016;368:4–10. 10.1016/j.jns.2016.06.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. D'Amelio M, Terruso V, Famoso G, et al. Early and late mortality of spontaneous hemorrhagic transformation of ischemic stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2014;23:649–54. 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.06.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information. Data are available upon reasonable request. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, LC (University of Debrecen Faculty of Medicine Department of Neurology, csiba@med.unideb.hu), upon reasonable request.