Abstract

Mitochondria, inherited maternally, are energy metabolism organelles that generate most of the chemical energy needed to power cellular various biochemical reactions. Deciphering mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) is important for elucidating vital activities of species. The complete chloroplast (cp) and nuclear genome sequences of Populus simonii (P. simonii) have been reported, but there has been little progress in its mitogenome. Here, we assemble the complete P. simonii mitogenome into three circular-mapping molecules (lengths 312.5, 283, and 186 kb) with the total length of 781.5 kb. All three molecules of the P. simonii mitogenome had protein-coding capability. Whole-genome alignment analyses of four Populus species revealed the fission of poplar mitogenome in P. simonii. Comparative repeat analyses of four Populus mitogenomes showed that there were no repeats longer than 350 bp in Populus mitogenomes, contributing to the stability of genome sizes and gene contents in the genus Populus. As the first reported multi-circular mitogenome in Populus, this study of P. simonii mitogenome are imperative for better elucidating their biological functions, replication and recombination mechanisms, and their unique evolutionary trajectories in Populus.

Keywords: Populus simonii, mitochondrial genome, fission, multi-circular molecule, comparative analysis

Introduction

Mitochondria are membrane-bound organelles only present in the cytoplasm of most eukaryotic (plants, animals, and fungi) cells. The primary function of mitochondria is to generate Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) by oxidative phosphorylation and produce metabolic intermediates for various cellular processes, hence it is popularly known as the “powerhouse” or “energy factory” of the cell (Krömer et al., 1988; Klingenberg, 2008). The outer mitochondrial membrane serves as a signal transmission platform, providing a scaffold for many critical proteins involved in cellular signaling (Liu et al., 1996; Mignotte and Vayssiere, 1998). Plant mitochondria are signaling organelles that participate in multiple biological processes, including programmed cell death, proliferation, respiration, and metabolic adaptation (similar to animal mitochondria) (Mignotte and Vayssiere, 1998; Chandel, 2021). Additionally, they also participate in conferring male sterility (Liberatore et al., 2016; Kim and Zhang, 2018; Siqueira et al., 2018). Plant mitochondria are well-known for their extreme variation in genome size, mutation rates, structural complexity, and ability to incorporate foreign DNA (Petersen et al., 2020). With the rapid development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) and third-generation sequencing (TGS) technologies, especially the emergence of Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) and Oxford Nanopore, an increasing number of plant organelle genomes have been assembled and submitted to NCBI GenBank. Up to February 2022, over 6800 complete plant chloroplast and plastid genomes have been deposited in GenBank Organelle Genome Resources1, but only 437 plant mitogenomes have been assembled. Among the assembled plant mitogenomes, 229 (more than half in total) were submitted in the past 5 years (2017–2021). The huge difference in the numbers of released mitochondrial and chloroplast genomes indicates that plant mitogenome is very complicated and difficult to assemble (Bi et al., 2020).

Plant mitogenomes are conventionally depicted as circular molecules, much like the circular chromosomes in animal mitochondria and bacteria (Kozik et al., 2019). However, the increased availability of plant mitogenomes have revealed that the in vivo structure of plant mitogenome is far more complex than a single circular chromosome model would suggest (Sloan, 2013). For example, the cucumber (Cucumis sativus) mitogenome was assembled into one large circular chromosome (1556 kb) and two small circular chromosomes (45 and 84 kb), of which only the large chromosome has protein-coding capability (Alverson et al., 2011). The copy number of the large chromosome is approximately twice as abundant as the two small chromosomes, suggesting the independent replication of the three mt chromosomes in cucumber plant cells (Alverson et al., 2011; Wu Z. Q. et al., 2020). Additionally, the Amborella trichopoda (A. trichopoda) mitogenome was found to have five circular chromosomes with lengths ranging from 119 to 3179 kb (Rice et al., 2013). For the holoparasitic plant, Lophophytum mirabile, the whole mitogenome (822 kb) was divided into 54 separate circular chromosomes with lengths ranging from 7.2 to 580 kb (Sanchez-Puerta et al., 2017). The largest and most complex multi-chromosomal mitogenomes have been found in the genus Silene, whose mitogenomes are often very large (>6000 kb) and contain a large number of circular chromosomes (Sloan et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2015a,b). However, dozens of the “empty” chromosomes in the Silene multi-chromosomal mitogenomes exhibit no protein-coding capability. Recently, the mitogenome of another holoparasitic plant, Rhopalocnemis phalloides, has been reported to consist of 21 minicircular chromosomes ranging from 4.95 to 7.86 kb with a shared region containing the replication origin, and replicates via a rolling circle mechanism (Yu et al., 2022). With extensive sampling of Silene noctiflora from 24 different populations, Wu and Sloan predicted that the dominating pattern of the multi-chromosomal variations should be the chromosome loss events after large ancestral expansions (Wu and Sloan, 2019). However, they could not get the conclusive result only from the limited genomic data. The multi-chromosomal mitogenome have also been found in many other species, but none was reported in genus Populus. Up to the present, only four Populus mitogenomes have been released, including Populus tremula (Kersten et al., 2016), P. davidiana (Choi et al., 2017), P. alba (Brenner et al., 2019), and P. tremula × P. alba (Kersten et al., 2016), all of which were assembled into the typical single circular structure. Accurate characterizations of plant mitogenome structures are imperative for better elucidating their biological functions, replication and recombination mechanisms, and their unique evolutionary trajectories (Kozik et al., 2019).

Populus simonii Carrière, commonly known as Chinese Cottonwood, is a fast-growing deciduous tree with shiny green, diamond-shaped leaves, mainly distributed from Qinghai to the east coast and from the Heilongjiang River to the Yangtze River (Wei et al., 2012). It is a major industrial tree species for building, urban landscaping, pulping, furniture, ecological protection, and biofuels (Yang et al., 2021). Chinese Cottonwood is also a primary tree species in preventing desertification, reducing soil erosion, counteracting wind damage, and fixing sand dunes in Northeast, North and Northwest China. Additionally, considering its drought resistance, barren tolerance, wide adaptability, strong rooting ability and interspecific cross-compatibility, P. simonii has been regarded as one of the best parents for breeding poplar clone varieties (Wu H. et al., 2020). Recently, the complete chloroplast (NC_037418.1) and nuclear (GCA_007827005.2) genome sequences of P. simonii have been released (Wu H. et al., 2020), but its mitogenome sequence is currently not available, hindering the development of new varieties with wider adaptive and commercial traits. In this study, we assembled the complete multi-circular P. simonii mitogenome based on the WGS data from the PacBio Sequel platform. Each chromosome of the P. simonii mitogenome has protein-coding capability. As the first reported multi-circular mitogenome in Populus, this study of P. simonii mitogenome will not only provide an important genetic resource for the comparative and functional genomic research in Populus, but also furnish an effective assembly strategy for other plant species, especially for species with difficulties in assembly.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material, DNA Extraction and Genome Sequencing

The male P. simonii seeds provided by Luoning Bureau of Forest, Henan Province, China and planted at the Xiashu Forest Farm of Nanjing Forestry University, Jurong, Jiangsu Province, China. Fresh leaves were collected and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, followed by preserving the leaves at –80°C in the laboratory prior to DNA extraction. The total genomic DNA was extracted from leaves using the CTAB protocol (Arseneau et al., 2017), and a library with an insert size of 20 kb was constructed using a BluePippin DNA size selection instrument (Sage Science, Beverly, MA, United States) with a lower size limit of 10 kb. The prepared library was sequenced on the PacBio Sequel platform (Pacific Biosciences, United States) at Frasergen Technologies Corporation, Wuhan, China. After the removal of adapter sequences using SMRTlink (v7.0.12), the remaining sequences were used for genome assembly and error correction. Additionally, to collect the contigs assembled by the PacBio sequencing data, we also sequenced the same genomic DNA afore-described on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing platform at Biomarker Technologies Corporation, Beijing, China.

Mitochondrial Genome Assembly

PacBio Sequel and Illumina HiSeq 2000 hybrid strategies were applied to assemble the whole mitogenome of P. simonii. The PacBio long reads were used to de novo assemble the draft mitogenome, and the Illumina short reads were used to polish the draft mitogenome. Since the raw PacBio reads contain high systematic error rate, Canu v2.1.1 was used to correct the raw sequencing data prior to the initial assembly (Koren et al., 2017). The error-corrected long reads were then fed to Newbler v3.0 assembler for de novo assembling the P. simonii mitogenome. Since Newbler v3.0 can only assemble sequencing reads with a length less than 30 kb, the overlong reads (>30 kb) were first disconnected into two or more shorter reads using local Perl scripts. Then, Newbler was used to assemble the preprocessed reads with the following parameters: -cpu 20, -het, -sio, -m, -urt, -large, and -s 100 (Bi et al., 2016; Ye et al., 2017). Next, BlastN was applied to extract the potential mitochondrial contigs using other three Populus mitogenomes (P. alba, P. davidiana, and P. tremula) as references (Altschul et al., 1990), and all potential mitochondrial contigs were then confirmed based on their read depths (Supplementary Figure S1). Using Perl scripts3, the potential mitochondrial contigs were connected to construct the draft assembly graph based on the file “454ContigGraph.txt,” which generated from Newbler v3.0 and recorded all the relatedness of contig connections (Wang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2011). According to read depths of these connected contigs, some false links and forks were manually removed, and finally 14 contigs were obtained to assemble the P. simonii mitogenome (Figure 1).

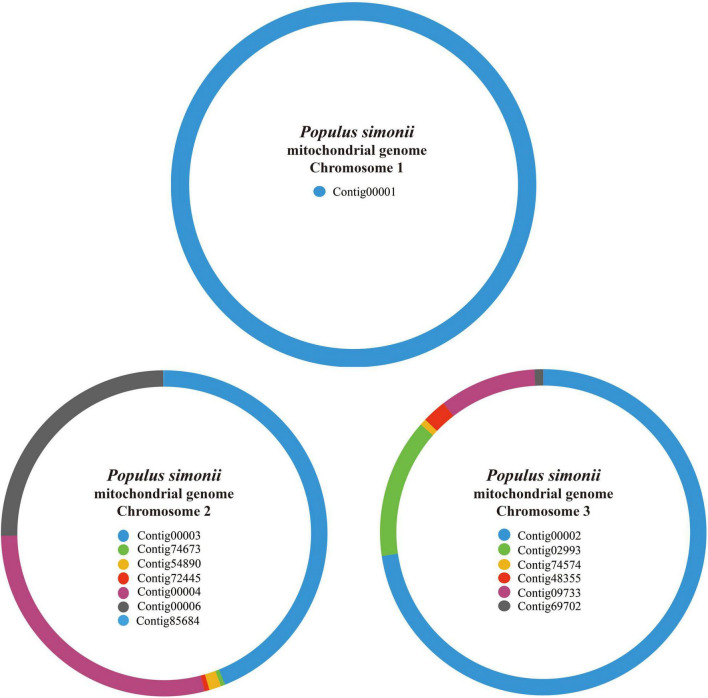

FIGURE 1.

The assembly graph of P. simonii mitogenome. The mt contigs chosen from Newbler are represented by different color blocks. The P. simonii mtChr1 is composed of only one contig, while mtChr2 and mt Chr3 are composed of seven and six contigs, respectively.

Mitogenome Verification and Correction

To ensure the correct assembly of the three chromosomes in P. simonii mitogenome, another de novo assembler SmartDenovo was used to assemble the P. simonii mitogenome (Liu et al., 2021). Mitochondrial contigs were identified by searching the assembled contigs against the three chromosomes generated from Newbler using BlastN. The aligned results showed that three contigs (utg1588, utg1107, and utg5276) belonged to the P. simonii mitogenome. All the three contigs were found to be self-assembled into a single circular chromosome by searching themselves using BlastN, which validates the multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii. Additionally, we used BlastN to acquire the break sites between the P. tremula mitogenome and three P. simonii mitochondrial chromosomes, and then extracted the sequences of 500 bp on both sides of the break sites. Then, BlastN was used to aligned the error-corrected PacBio reads to the break sites (500 bp on both sides) to determine the multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii.

To improve the accuracy of the mitogenome assembly, the draft mitogenome was polished with both PacBio long reads and Illumina short reads. For PacBio long reads correcting, all the PacBio clean reads were mapped onto the draft mitogenome using minimap2 (Li, 2018), and then the errors were corrected using racon4 with default parameters. For Illumina short reads correction, BWA mem (v0.7.17) (Li and Durbin, 2009) was used to map all the pair-end (PE) reads of the same individual onto the mitogenome of P. simonii that generated from correcting processes of the PacBio long reads. Then, SAMtools (v1.11) (Danecek et al., 2021) was used to convert the output files to BAM format, and Pilon (v1.23) (Walker et al., 2014) was applied to further correct the mitogenome with default parameters.

Mitogenome Annotation

The public MITOFY analysis web server5 (Alverson et al., 2010) was employed to predict the protein-coding genes, tRNA and rRNA genes of the complete P. simonii mitogenome. The putative protein-coding genes (PCGs) were manually checked and adjusted by referring to other Populus mitogenomes, including P. alba, P. tremula, and P. davidiana. The tRNA and rRNA genes were confirmed using tRNAscan-SE v1.21 (Schattner et al., 2005) and RNAmmer 1.2 Server (Lagesen et al., 2007). Finally, the annotations of PCGs, tRNA and rRNA genes were integrated and manually reviewed using MacVector v18.0. The online program GeSeq6 were used to visualize the multi-circular genome map of P. simonii mitogenome (Tillich et al., 2017).

Whole-Genome Alignment and Repeat Analyses in Populus

To verify the fission of P. simonii mitogenome from other Populus mitogenomes, the nucmer program of MUMmer v3.23 (Kurtz et al., 2004) was used to align the mitogenomes of P. simonii, P. davidiana (NC_035157.1), and P. alba (NC_041085.1) against the P. tremula mitogenome (NC_028096.1). Then, the delta-filter program of MUMmer was used to filter the alignments from nucmer with the minimum alignment identity of 80% and minimum alignment length of 100 bp. Mummerplot was used to visualize the alignment results produced by mummer and delta-filter by using the GNU gnuplot utility.

The simple sequence repeats (SSRs) of the P. simonii mitogenome were detected using the online Microsatellite identification tool7 with an SSR motif length of 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 bases and thresholds of 8, 4, 4, 3, 3, and 3 repeat numbers, respectively (Beier et al., 2017). The tandem repeats were detected using the online tool Tandem Repeats Finder v4.098 with default parameters (Benson, 1999). The dispersed repeats were detected using online REPuter program9 with the minimal repeat size of 30 bp and hamming distance of 3 (Kurtz et al., 2001).

Phylogenetic Analysis

To accurately infer the phylogenetic relationships of P. simonii, the conserved PCGs from the mitogenomes of P. simonii and 34 other plants were used to construct the phylogenetic tree. These observed mitogenomes were downloaded from NCBI, and the accession numbers and abbreviations were listed in Supplementary Table S1. A local Perl script was used to identify the conserved PCGs of all observed mitogenomes10. The selected 22 PCGs (atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, atp9, ccmB, ccmC, ccmFc, ccmFn, cob, cox1, cox2, cox3, nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, and nad9) were concatenated into a single dataset of FASTA format, and then aligned using Muscle software with default settings (Edgar, 2004). Subsequently, IQ-TREE v2.1.4 (Minh et al., 2020) was used to construct the maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic tree with the following settings: -m MFP -B 1000 –bnni -T AUTO. The best evolutionary model was chosen as ‘GTR+F+R4’ according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) scores generated from IQ-TREE. The bootstrap value (%) in which the associated taxa clustered together was inferred from 1000 replications.

Results

Genome Assembly of the Multi-Circular Mitogenome of Populus simonii

For PacBio Sequel platform, a total of 604,419 PacBio reads representing ∼7.6 Gb were generated, with an average read length of 12,589 bp, and the longest read length was 112,390 bp (Supplementary Table S2). To correct the draft mitogenome generated from PacBio sequencing data, a total of 327 million PE reads representing 32.7 Gb were also generated using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 sequencing platform. After the overlong reads were cut into two or more shorter reads using local Perl scripts, 663,890 reads were obtained for subsequent assembly. The de novo assembly of Newbler generated 90,449 contigs, and the longest contig was 312,303 bp (Supplementary Table S2). After removing false links and some wrong forks from horizontal gene transfer (HGT), 14 contigs were obtained to construct the draft contig connection graph of P. simonii mitogenome (Figure 1). As shown in Table 1, the genome coverage of each mitochondrial contig was approximately 70×, and only Contig85684 (1036.3×) and Contig69702 (113.7×) showed some anomalies, of which the former belonged to cp-derived sequences and partial sequences of the latter belonged to dispersed repeats. The mitogenome was composed of three circular chromosomes, and the largest one (length: 312,303 bp) was assembled by only one contig (Contig00001), the second one (length: 282,737 bp) was assembled by seven contigs (Contig00003, Contig00004, Contig00006, Conti54890, Contig72445, Contig74673, and Contig85684), and the shortest one (length: 185,980 bp) was assembled by six contigs (Contig00002, Contig02993, Contig74574, Contig48355, Contig09733, and Contig69702).

TABLE 1.

Newbler assembled contigs of P. simonii mitogenome.

| Chromosome | Contig name | Coverage (×) | Number of reads | Length (bp) |

| mtChr1 | Contig00001 | 73.3 | 1,931 | 312,303 |

| mtChr2 | Contig00003 | 70.4 | 757 | 124,150 |

| Contig00004 | 61.1 | 455 | 81,303 | |

| Contig00006 | 71.3 | 444 | 71,063 | |

| Contig54890 | 68.9 | 98 | 3,376 | |

| Contig72445 | 88.1 | 109 | 1363 | |

| Contig74673 | 73.3 | 79 | 1191 | |

| Contig85684a | 1036.2 | 1,059 | 291 | |

| mtChr3 | Contig00002 | 72.6 | 927 | 135,137 |

| Contig02993 | 71.7 | 197 | 25,710 | |

| Contig09733 | 65.7 | 144 | 17,871 | |

| Contig48355 | 67 | 99 | 4,456 | |

| Contig69702 | 113.7 | 123 | 1,607 | |

| Contig74574 | 82.3 | 96 | 1199 | |

| Average/Total | 14 | 75.3b | 6,518 | 781,020 |

acp-derived.

bThe average coverage of 13 mt contigs without one cp-derived contig.

To validate the assembly of the multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii, we used BlastN to acquire the break sites between the P. simonii and P. tremula mitogenomes (Supplementary Figure S2), and then mapped all the error-corrected PacBio reads to the break sites (500 bp on both sides). A total of 719 PacBio reads were found to be similar to the sequences around the break sites (identity > 95%, length > 450 bp), but almost none of them spanned more than 60% of the entire sequences (Supplementary Table S3), suggesting that the multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii was assembled accurately. Subsequently, a more accurate multi-circular mitogenome was obtained after polishing with both PacBio long reads and Illumina short reads.

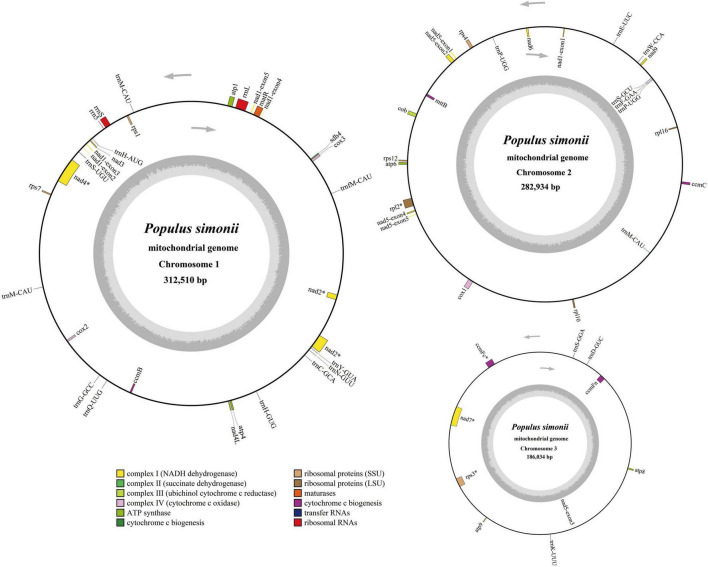

Genomic Features of the Populus simonii Mitogenome

The multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii has been submitted to NCBI Genome Database under the GenBank accessions: MZ905370, MZ905371, and MZ905372. The whole P. simonii mitogenome was assembled into three circular chromosomes, with an atypical multi-circular conformation rather than the typical single circular structure in most plant mitogenomes (Guo et al., 2017). The largest circular chromosome (mtChr1) was 312,510 bp in length, the second one (mtChr2) was 282,934 bp in length, and the shortest one (mtChr3) was 186,034 bp in length (Figure 2). The P. simonii mitogenome (Size: 781,478 bp, GC content: 44.78%) was similar in size and GC content to that of other Populus mitogenomes (Table 2), such as P. tremula (Size: 783.4 kb, GC content: 44.75%), P. alba (Size: 838.4 kb, GC content: 44.82%), and P. davidiana (Size: 781.5 kb, GC content: 44.82%).

FIGURE 2.

Circular maps of the multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii. Genomic features on transcriptionally clockwise and counterclockwise strands are drawn on the inside and outside of the three circles, respectively. GC content of each chromosome is represented on the inner circle by the dark gray plot. The asterisks (*) besides genes denote intron-containing genes.

TABLE 2.

General mitogenomic features of four representative plants in the genus Populus.

| Feature | P. simonii | P. alba | P. davidiana | P. tremula |

| Genome size (bp) | 781,478 | 838,420 | 779,361 | 783,442 |

| GC content (%) | 44.78 | 44.82 | 44.82 | 44.75 |

| No. of PCGs | 33 | 34 | 34 | 34 |

| No. of tRNA genes | 21 | 22 | 22 | 22 |

| No. of rRNA genes | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| No. of exons | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| No. of introns | 17 | 17 | 17 | 17 |

| Coding regions (bp) | 64,483 (8.25%) | 63,781 (7.61%) | 64,099 (8.22%) | 64,153 (8.19%) |

| tRNA | 1,583 | 1,663 | 1,663 | 1,663 |

| rRNA | 5,365 | 5,369 | 5,369 | 5,373 |

| PCGs | 30,237 | 29,694 | 30,063 | 30,063 |

| Cis-spliced introns (bp) | 27,298 | 27,055 | 27,004 | 27,054 |

| Intergenic regions (bp) | 716,995 (91.75%) | 774,639 (92.39%) | 715,262 (91.78%) | 719,289 (91.81%) |

There are 57 genes annotated in the P. simonii mitogenome, including 33 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 21 tRNA genes and 3 rRNA genes (Table 2). Since this mitogenome did not have large repeated regions, all the annotated genes were single-copy genes, except for two tRNA genes (trnM-CAU and trnP-UGG). The total length of coding sequences (PCGs, tRNA and rRNA genes) was 64,483 bp, accounting for 8.25% of the whole P. simonii mitogenome, while more than 90% of the mitogenome belonged to intergenic regions. The physical locations, gene length, and functional types of annotated genes were shown in Supplementary Table S4 and Figure 2. In the P. simonii mitogenome, most of the PCGs use ATG as the start codon, while mttB and rpl16 cannot determine their start codons. It is unknown whether RNA-editing will likely correct these undetermined start codons. All the PCGs used TAA, TAG or TGA as stop codons, suggesting that there is no RNA-editing event happened in the stop codons (Ye et al., 2017).

All three chromosomes of the P. simonii mitogenome had protein-coding capability, in which most of the PCGs were annotated on a single chromosome, while nad1 and nad5 were separated by two different chromosomes (Figure 2). The exon1 of nad1 was located on mtChr2, while the other four exons were located on mtChr1. The exon3 of nad5 was located on mtChr3, while the other four exons were located on mtChr2. The number of introns was reported variably in different land plants (Mower, 2020). In P. simonii mitogenome, 8 protein-coding genes were identified harboring 17 cis-spliced introns with 27,298 bp in length (Supplementary Table S4), including three genes contained one intron (rpl2, ccmFc, and rps3), two genes contained two introns (nad1 and nad5), two genes contained three introns (nad2 and nad4), and one gene (nad7) contained four introns.

Analyses of Genomic Syntenic Regions and Rearrangements in Populus

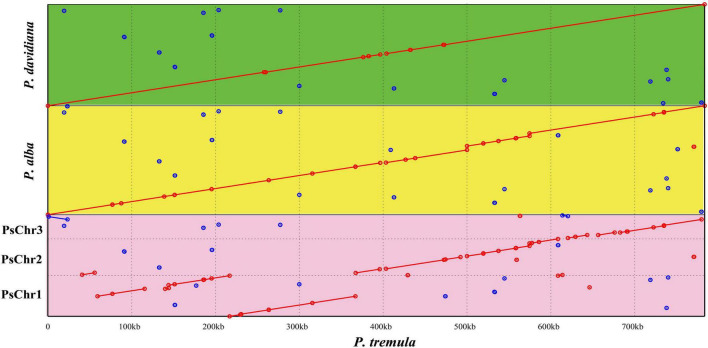

Using the nucmer program of MUMmer v3.23, the mitochondrial evolution in Populus was investigated by detecting the syntenic regions and rearrangements between P. tremula mitogenome and other three mitogenomes, including P. simonii, P. alba, and P. davidiana. Between the mitogenomes of P. tremula and P. simonii, 56 local colinear blocks (LCBs) were detected accounting for 89% (695,519 bp) of the whole P. simonii mitogenome (Figure 3 and Supplementary Table S5). Between the mitogenomes of P. tremula and P. alba, 41 LCBs were detected accounting for 92.65% (776,825 bp) of the whole P. alba mitogenome. Between the mitogenomes of P. tremula and P. davidiana, 25 LCBs were detected accounting for 99.11% (772,408 bp) of the whole P. davidiana mitogenome. Since over 99% sequences of the P. davidiana mitogenome were co-linear with P. tremula, the differentiation of P. tremula and P. davidiana must be very recent. The dot plot further illustrated the sequence rearrangements in four mitogenomes. As clearly illustrated in Figure 3, there were only two large-scale rearrangements underwent between the mitogenomes of P. tremula and P. davidiana, at least 4 large-scale rearrangements occurred between the mitogenomes of P. tremula and P. alba, and at least 13 large-scale rearrangements occurred between the mitogenomes of P. tremula and P. simonii. The arrangements detected among four Populus mitogenomes did not disrupt the gene clusters, because the gene clusters were mostly located in syntenic regions.

FIGURE 3.

Mitogenomic syntenic analyses among four Populus species. The P. tremula mitogenome was set as reference. PsChr1, PsChr2, and PsChr3 represent the three circular chromosomes of P. simonii mitogenome. The green, yellow, and pink rectangular region represent the syntenic regions of P. tremula vs. P. davidiana, P. tremula vs. P. alba, and P. tremula vs. P. simonii, respectively. The red and blue lines refer direct and inverted syntenic regions, respectively.

Analyses of Repeat Elements in Populus simonii Mitogenome

The variable genome size and structure of plant mitogenomes can be explained by variable repeat sequences, composing of SSRs, tandem repeats, and dispersed repeats. SSRs, also known as microsatellite DNA, which are DNA fragments consisting of tandem-repeated short units of 1–6 base pairs in length that are very useful molecular markers in identifying genetic diversity and unknown species. Using the online Microsatellite identification tool, 708 SSRs were identified in P. simonii mitogenome, including 296 mono-, 273 di-, 29 tri-, 89 tetra-, 16 penta-, and 5 hexa-nucleotide repeats (Supplementary Table S6). The total number of SSRs of P. simonii mitogenome was similar to those of other three Populus mitogenomes, but a little higher than those of other plants in Malpighiales, probably due to the different genome sizes. The repeat units of A/T, AG/CT, and AAAG/GTTT were found to be more prevalent than other repeat types in mononucleotide, dinucleotides, and tetranucleotides, respectively. Tandem repeats, also known as minisatellite DNA, are defined classically as tandem repeats of larger than 10 bp in length. They are widely distributed in eukaryotic genome and in some prokaryotes (Cheng et al., 2021). Using the online tool Tandem Repeats Finder, 7, 5, and 2 tandem repeats with lengths ranging from 13 bp to 33 bp in mtChr1, mtChr2, and mtChr3 were detected, respectively (Supplementary Table S7). Except for one tandem repeat located in coding region (rrnL), the others were all distributed in the intergenic spacers.

Besides SSRs and tandem repeats, a total of 322 dispersed repeats with lengths > 30 bp were detected in the P. simonii mitogenome using REPuter software (Table 3). The total length of dispersed repeats was 32,635 bp, accounting for 4.18% of the whole mitogenome. As shown Table 3, most of the repeats were 30 to 49 bp long (227 repeats, 70.5%), and the longest repeat was only 297 bp, with no repeats longer than 300 bp. Large repeats play crucial roles in genomic structure changes, and pairwise direct and inverted large repeats (>500 bp) may produce subgenomic or isomeric conformations (Bi et al., 2020). Since there were no repeats longer than 300 bp in the P. simonii mitogenome, no other subgenomic or isomeric conformations were detected. Due to the lack of large repeats in Populus mitogenomes (P. simonii, P. alba, P. davidiana, and P. tremula), the sizes and gene numbers of the four Populus mitogenomes were very conserved, and no multi-copy protein-coding genes in Populus mitogenomes were identified. By contrast, we identified 7, 4, 2 and 1 large repeats in Passiflora edulis (Pa. edulis), Manihot esculenta (M. esculenta), Ricinus communis (R. communis), and Salix suchowensis (S. suchowensis) mitogenomes, respectively. The Pa. edulis mitogenome contained the most repetitive sequences (total repeat length: 202,676 bp, 29.78% of the whole mitogenome), followed by M. esculenta (60,294 bp, and 8.83%) and S. suchowensis (50,339 bp, 7.81%).

TABLE 3.

Comparison of dispersed repeats in nine Malpighiales plant mitogenomes.

| Species | Repeat size (bp) |

Longest repeat (bp) | Total repeat length (bp) | Proportion of genome (%) | ||||||

| 30–49 | 50–69 | 70–99 | 100–149 | 150–199 | 200–499 | >500 | ||||

| P. simonii | 227 | 49 | 24 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 297 | 32,635 | 4.18 |

| P. alba | 242 | 43 | 30 | 19 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 308 | 35,485 | 4.23 |

| P. davidiana | 219 | 36 | 27 | 15 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 286 | 31,665 | 4.06 |

| P. tremula | 217 | 40 | 26 | 15 | 7 | 5 | 0 | 308 | 32,056 | 4.09 |

| S. suchowensis | 140 | 30 | 14 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 15,592 | 50,339 | 7.81 |

| S. brachista | 134 | 30 | 13 | 9 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 392 | 20,555 | 3.38 |

| M. esculenta | 189 | 52 | 25 | 22 | 9 | 9 | 4 | 32,495 | 60,294 | 8.83 |

| P. edulis | 177 | 53 | 37 | 20 | 13 | 17 | 7 | 4,930 | 202,676 | 29.78 |

| R. communis | 116 | 24 | 24 | 17 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 4,289 | 31,114 | 6.19 |

Phylogenetic Analyses

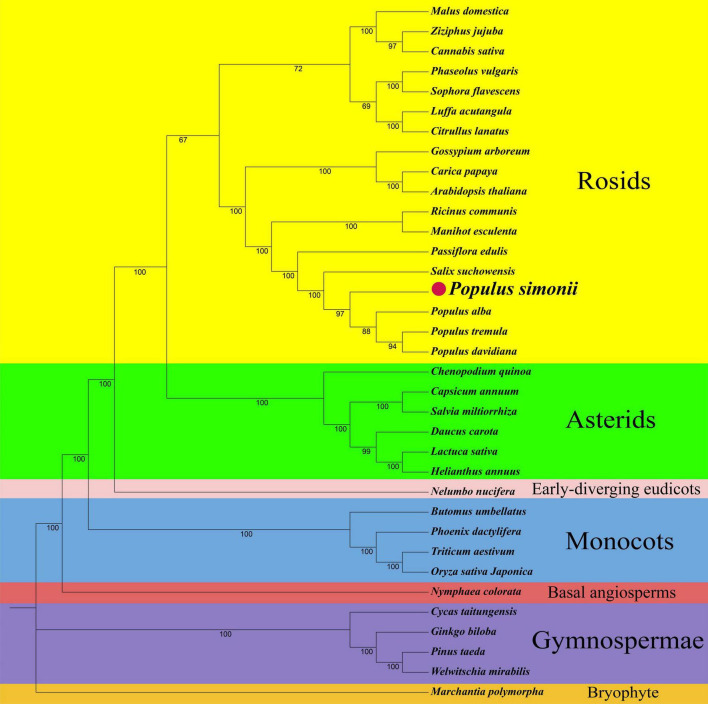

Phylogenetic analyses were performed based on the conserved PCGs of P. simonii and other 34 land plants, including 18 rosids, 6 asterids, one early-diverging eudicot of Nelumbo nucifera, four monocots, one basal angiosperm of Nymphaea colorata, 4 gymnosperms, and one plant (Marchantia polymorpha) in bryophyte. The abbreviations and GenBank accession numbers of all observed plants were listed in Supplementary Table S1. The maximum-likelihood (ML) tree strongly supported the separation of P. simonii and other three Populus plants with 97% bootstrap value, as well as the separation of rosids and asterids, the separation of eudicots and monocots (100%), and the separation of angiosperms and gymnosperms (100%) (Figure 4). The topology was highly similar to the APG IV system (Group Angiosperm Phylogeny, 2016).

FIGURE 4.

The phylogenetic relationships of P. simonii with other 34 represented land plants. Numbers on each node are bootstrap support values. Colors indicate the families of each species.

Frequent Protein-Coding Genes Loss and Acquisition in Land Plant Mitogenomes

The land plant mitogenomes have functionally diverse repertoires of 43 protein-coding genes, which is likely to be the full set of PCGs in the common ancestor of land plant mitogenomes. The plants in liverwort and moss have retained nearly all of the ancestral repertoire, while hornworts and some angiosperms have lost one-third or more of these ancestral genes (Supplementary Table S8). Strikingly, four mitochondrial genes involving the cytochrome c maturation (ccm) pathway have been retained in most land plants but lost in hornworts and ferns during land plant evolution. The genes encoding ATP synthase (atp1, atp4, atp6, atp8, and atp9), ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase (cob), cytochrome c oxidase (cox1, cox2, and cox3), and NADH dehydrogenase (nad1, nad2, nad3, nad4, nad4L, nad5, nad6, nad7, and nad9) were largely conserved among all land plant mitogenomes. The rpl6 and rps8 genes have been lost from all seed plants during the evolution, while rps2 and rps11 have been lost from most eudicot plants after the differentiation of eudicots and monocots. Significantly, the rps14 gene was conserved in P. alba, P. tremula, and P. davidiana, but lost from the P. simonii mitogenome. To evaluate the absence pattern of rps14 gene during the evolution of P. simonii, the rps14 genes of P. alba, P. tremula and P. davidiana mitogenomes were used as query to search for homologous sequences in its chloroplast (NC_037418.1) and nuclear genomes (GCA_007827005.2) using BlastN. However, homologous sequences were not found in cp and nuclear genomes, suggesting that rps14 gene was completely lost from P. simonii mitogenome during the divergence of P. simonii and other plants in the genus Populus.

Discussion

Mitochondrial Genome Size Variation

After several years of sequencing and study, it is now very clear that plant mitogenome is an evolutionarily dynamic entity exhibiting incredible diversity across plants in terms of size, gene content, and genome structure (Petersen et al., 2020). The primary explanations for the size variations in plant mitogenomes are the proliferation of repeat elements, the incorporation of foreign sequences, and gain or loss of large intra-genetic segments (Wu Z. Q. et al., 2020). Previous study of several mitogenomes of Zea mays found their size varied from 536 to 740 kb with large repeat elements (0.5–120 kb) accounting for most of the size variations (Allen et al., 2007). Another study estimated that approximately 20% of the mitogenome of Malus domestica was imported from other cellular compartments, including nucleus and chloroplast (Goremykin et al., 2012). Additionally, the mitogenome A. trichopoda was found to contain a large number of sequences transferred horizontally from green algae, mosses and other angiosperms (Rice et al., 2013).

In genus Populus, the mitogenome sizes are very conserved (Table 2), ranging from 779 kb (P. davidiana) to 838 kb (P. alba). Comparative repeat analyses of four Populus mitogenomes (Table 3) showed that there were no repeats larger than 350 bp in Populus mitogenomes, probably contributing to the stability of genome sizes, gene contents, and genome structures in the genus Populus. The extremely complex repeat patterns should be responsible for the various mitogenome sizes in plant species, however, mitogenome size is by no means only determined by repeats. The frequent transfers of foreign DNA among chloroplast, mitochondrion and nuclear can also contribute to the variable mitogenome sizes (Bergthorsson et al., 2003).

Variation in Protein-Coding and tRNA Genes Among Plant Mitogenomes

Mitochondrial PCGs are largely conserved among liverworts and mosses, but vary substantially among and within land plants due to frequent losses and acquisitions of genes encoding ribosomal proteins and, to a lesser extent, genes involved in cytochrome c maturation and oxidative phosphorylation (Mower, 2020). With rare exception, most lineages of observed plants have retained between 30 and 41 (Marchantia polymorpha and Scapania ornithopodioides) PCGs in their mitogenomes, with functions ranging from oxidative phosphorylation to the maturation, translation, and transport of proteins (Burger et al., 2012). As shown in Supplementary Table S8, the genes encoding ribosome proteins (rpl- and rps- genes) and succinate dehydrogenases (sdh3 and sdh4) among the observed 44 plant mitogenomes were particularly prone to lose from plant mitogenomes, whereas genes encoding oxidative phosphorylation subunits were much more likely to be retained during the angiosperm evolution (Adams, 2003; Park et al., 2015; Bi et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2018).

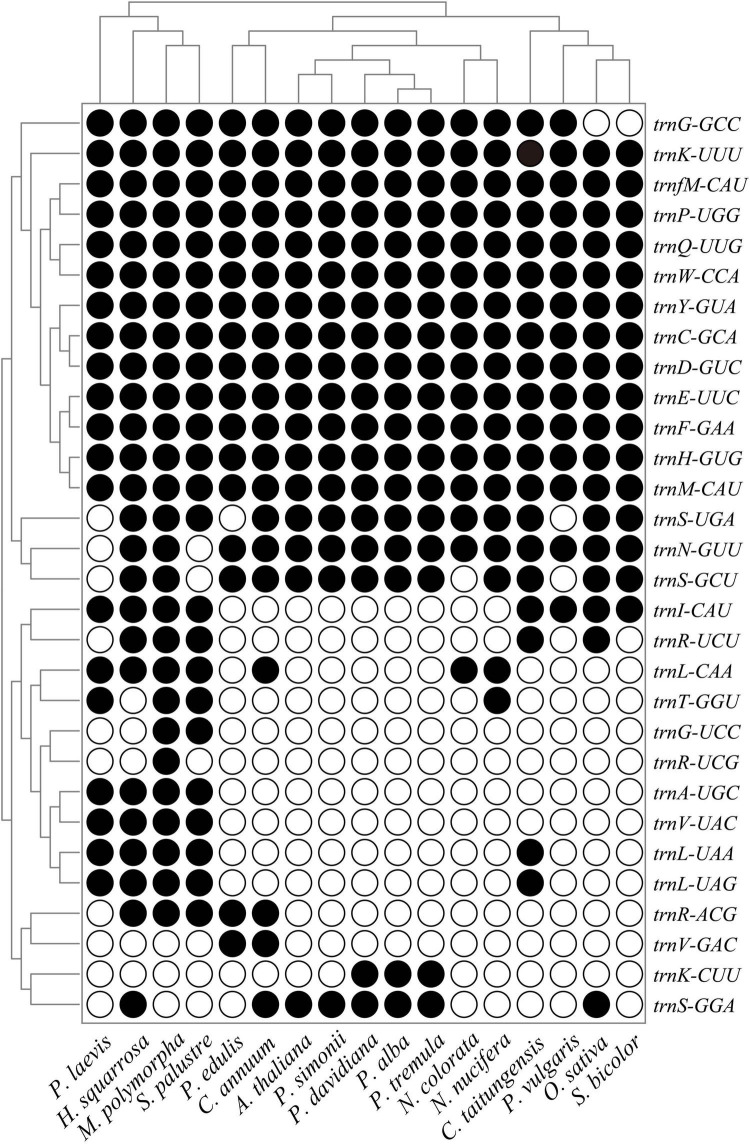

The loss and acquisition patterns of tRNA genes in land plants were also investigated in this study. Twelve tRNA genes (trnC-GCA, trnD-GUC, trnE-UUC, trnF-GAA, trnH-GUG, trnK-UUU, trnM-CAU, trnfM-CAU, trnP-UGG, trnQ-UUG, trnW-CCA, and trnY-GUA) were very conserved during the land plant evolution, while the other tRNA genes were prone to loss from one or more plant mitogenomes (Figure 5). In contrast to other plant mitogenomes in Populus, the rps14 and trnK-CUU were lost from P. simonii, where trnK-CUU was transferred into its nuclear genome, and rps14 was complete lost from P. simonii mitogenome during evolution. These lost genes can experience different fates; they may be completely lost from the cell (Adams, 2003), or functionally substituted by the same functional genes from plastids, nuclei, or the cytosol (Lei et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2021). Previous studies have reported that most mitochondrial lost tRNA genes were generally compensated by the corresponding cp-derived tRNA genes, such as trnH-GUG, trnN-GUU, trnS-GGA, and trnW-CCA (Bi et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2021). Additionally, some lost genes (rps2, rps11, and rps19) were transferred to the nucleus during evolution, which was the main pathway for PCGs loss in plant mitogenomes (Adams et al., 2002; Park et al., 2015). Frequent intracellular gene transfers among nucleus, chloroplast and mitochondrion promoted the movement of genetic material in organisms, and enabled the nucleus to control the organelle by encoding organelle-destined proteins and tRNA genes (Woodson and Chory, 2008).

FIGURE 5.

Mitochondrial tRNA gene contents among 17 representative plants. Black circle, gene is present; White circle, gene is absent. Species names are abbreviated as shown in Supplementary Table S1.

Multi-Chromosomal Structure in Plant Mitogenomes

Plant mitogenomes are conventionally depicted as circular molecules (Kozik et al., 2019), however, the increased availability of plant mitogenomes have revealed that the in vivo structure of plant mitogenome is far more complex than a single circular molecule would suggest (Sloan, 2013). The multi-chromosomal mitogenomes have been detected in many species, including ferns, gymnosperms, basal angiosperms, eudicots, and monocots. The mitogenome of the whisk fern Psilotum nudum (genome size: 629 kb) was assembled into two circular chromosomes (Guo et al., 2017). The largest mitogenomes sequenced to date are mainly from Gymnosperm species, but the number of chromosomes cannot be resolved accurately at his time due to their incomplete assemblies (Nystedt et al., 2013; Jackman et al., 2015). The mitogenome of the basal angiosperm A. trichopoda (genome size: ∼3900 kb) was detected to consist of five circular chromosomes ranging from 118.7 to 3179.3 kb (Rice et al., 2013). The number of chromosomes varies widely among eudicots, with the largest being the mitogenome of Silene conica (>128 chromosomes), while the number of chromosomes is concentrated between 2 and 5 in other multi-chromosomal eudicots (Wu, Z. Q. et al., 2020), such as Actinidia chinensis (Actinidiaceae) (Wang et al., 2019), C. sativus (Cucurbitaceae) (Alverson et al., 2011), Camellia sinensis (Ericaceae) (Zhang et al., 2019), Fallopia multiflora (Ericaceae) (Kim and Kim, 2018), Solanum tuberosum (Solanaceae) (Varre et al., 2019), and so on. For monocots, the number of multi-chromosomes were found to contain 2 or 3 chromosomes, while the mitogenome of Gastrodia elata (Orchidaceae) was assembled into 19 chromosomes (Yuan et al., 2018).

Unlike the fungal and animal multi-chromosomal mitogenomes in which the functional genes are distributed evenly between chromosomes, many chromosomes in plant multi-chromosomal mitogenomes do not contain any functional genes. For example, 20 out of 59 chromosomes in the S. noctiflora mitogenome were found to contain no functional genes (Wu et al., 2015a). All functional genes of the C. sativus mitogenome were found in the large chromosome, while none was detected in the other two small chromosomes (Alverson et al., 2011). In this study, we found that all three chromosomes of the P. simonii mitogenomes contain functional genes, and two protein-coding genes (nad1 and nad5) were detected to be separated by two different chromosomes. Further transcriptome studies are needed to verify whether these two genes can be properly expressed in plant mitochondria.

The Prospects of Plant Mitogenome Research

Because of the incorporation of foreign DNA, the proliferation of repeat elements, and the frequent gain or loss of intragenomic segments, the number of complete plant mitogenomes is far fewer than that of chloroplast genomes and animal mitogenomes. With the limited number of plant mitogenomes, it is difficult to investigate the dominant pattern of variation in multi-chromosomal mitogenomes at both inter- and intraspecific levels. Wu and Sloan predicted that the primary pattern of the multi-chromosomal variations should be the chromosome loss events after large ancestral expansions (Wu and Sloan, 2019), however, they could not get the conclusive result only from the limited genomic data. In this study, the P. simonii mitogenome was assembled into three circular chromosomes, with an atypical multi-chromosomal mitogenome rather than the typical single circular structure in other sequenced Populus mitogenomes. Therefore, Populus can be stand as a superb model genus to explore the evolutionary pattern and the drivers for the variation of multi-chromosomal structures. Many questions remain about the molecular factors and mechanisms of the variation of multi-chromosomal structures in plants, for example, what potentially novel mechanisms regulate and control the replication and segregation of multi-chromosomal mitogenomes during cell division? How do they achieve fusions of the inner and outer membranes? Why these “empty” mitochondrial chromosomes retained, and what purpose do they play at different stages of development? In the near future, RNA-seq, small RNA-seq and multigenerational studies involving controlled crosses may shed light on these questions.

Plant mitochondria have many features that distinguish them from fungal and animal mitochondria, such as abundance, smallness, fast movement, and roles in cytoplasmic male sterility (Arimura, 2018). These plant-specific features provide many challenging and exciting opportunities for future research. With the continuing development of long-read sequencing method, such as PacBio and Oxford Nanopore sequencing, more and more accurate mitogenome structures can be acquired in the near future, which are imperative for better elucidating their biological functions, replication and recombination mechanisms, and their unique evolutionary trajectories (Kozik et al., 2019).

Conclusion

In this study, we assembled the multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii, which was reported in genus Populus for the first time. Whole-genome alignment analyses found that the four Populus mitogenomes shared more than 90% local colinear blocks, indicating the fission of poplar mitogenome in P. simonii must be very recent. There were no repeats longer than 350 bp in four Populus mitogenomes, probably contributing to the stability of genome sizes and gene contents in genus Populus. The gene loss of rps14 gene and horizontal transfer of trnK-UUU gene need to be studied to elucidate their specific mechanisms in the future. Further phylogenetic analyses based on P. simonii and other 34 plant mitogenomes provide new clues for phylogenetic relationships, especially for Salicaceae and Malpighiales. In summary, as the first reported multi-circular mitogenome in Populus, this study of P. simonii mitogenome will provide not only an important atypical mitogenome resource for the comparative and functional genomic research in Populus, but also a reliable clue for the research of their unique evolutionary trajectories.

Data Availability Statement

The PE and PacBio sequencing data of P. simonii have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository under SRR3204721 and SRR9887262, respectively. The multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii is available in NCBI Nucleotide Database under the GenBank accessions: MZ905370, MZ905371, and MZ905372. All the other mitogenome sequences used in this study are available in the NCBI Genome Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/organelle/) under the GenBank accessions listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Author Contributions

CB: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, software, visualization, writing of original draft, writing of review and editing. YQ: data curation, resources, and software. JH: validation and funding acquisition. KW: validation and formal analysis. NY: writing of review and editing, methodology, and software. TY: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing of review and editing. All authors: contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Chunfa Tong for providing the samples and sequencing data. We also thank Lin Huang for help of polishing the final version of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported by the Key Research and Development Project of Jiangsu Province, China (BE2021366) and Natural Science Foundation of China (31901331).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpls.2022.914635/full#supplementary-material

The distribution of contig length and read depth in the de novo assembly by Newbler v3.0.

Comparison of P. tremula and P. simonii mitochondrial genomes. PsChr1, PsChr2, and PsChr3 represent the three circular molecules of P. simonii mitogenome, respectively.

References

- Adams K. (2003). Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: gene loss and transfer to the nucleus. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 29 380–395. 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00194-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams K. L., Qiu Y. L., Stoutemyer M., Palmer J. D. (2002). Punctuated evolution of mitochondrial gene content: high and variable rates of mitochondrial gene loss and transfer to the nucleus during angiosperm evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99 9905–9912. 10.1073/pnas.042694899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen J. O., Fauron C. M., Minx P., Roark L., Oddiraju S., Lin G. N., et al. (2007). Comparisons among two fertile and three male-sterile mitochondrial genomes of maize. Genetics 177 1173–1192. 10.1534/genetics.107.073312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul S. F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E. W., Lipman D. J. (1990). Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215 403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverson A. J., Rice D. W., Dickinson S., Barry K., Palmer J. D. (2011). Origins and recombination of the bacterial-sized multichromosomal mitochondrial genome of cucumber. Plant Cell 23 2499–2513. 10.1105/tpc.111.087189 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alverson A. J., Wei X., Rice D. W., Stern D. B., Barry K., Palmer J. D. (2010). Insights into the evolution of mitochondrial genome size from complete sequences of Citrullus lanatus and Cucurbita pepo (Cucurbitaceae). Mol Biol Evol 27 1436–1448. 10.1093/molbev/msq029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arimura S. I. (2018). Fission and fusion of plant mitochondria, and genome maintenance. Plant Physiol. 176 152–161. 10.1104/pp.17.01025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arseneau J. R., Steeves R., Laflamme M. (2017). Modified low-salt CTAB extraction of high-quality DNA from contaminant-rich tissues. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 17 686–693. 10.1111/1755-0998.12616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beier S., Thiel T., Munch T., Scholz U., Mascher M. (2017). MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics 33 2583–2585. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. (1999). Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27 573–580. 10.1093/nar/27.2.573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergthorsson U., Adams K. L., Thomason B., Palmer J. D. (2003). Widespread horizontal transfer of mitochondrial genes in flowering plants. Nature 424 197–201. 10.1038/nature01743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi C., Lu N., Xu Y., He C., Lu Z. (2020). Characterization and analysis of the mitochondrial genome of common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) by comparative genomic approaches. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:3778. 10.3390/ijms21113778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bi C., Paterson A. H., Wang X., Xu Y., Wu D., Qu Y., et al. (2016). Analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the diploid cotton Gossypium raimondii by comparative genomics approaches. Biomed. Res. Int. 2016:5040598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenner W. G., Mader M., Muller N. A., Hoenicka H., Schroeder H., Zorn I., et al. (2019). High level of conservation of mitochondrial RNA editing sites among four populus species. G3 Genes Genomes Genet. 9 709–717. 10.1534/g3.118.200763 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burger G., Jackson C. J., Waller R. F. (2012). Unusual Mitochondrial Genomes and Genes. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Chandel N. S. (2021). Mitochondria. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 13:a040543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Y., He X., Priyadarshani S., Wang Y., Ye L., Shi C., et al. (2021). Assembly and comparative analysis of the complete mitochondrial genome of Suaeda glauca. BMC Genomics 22:167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi M. N., Han M., Lee H., Park H. S., Kim M. Y., Kim J. S., et al. (2017). The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of Populus davidiana Dode. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2 113–114. 10.1080/23802359.2017.1289346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danecek P., Bonfield J. K., Liddle J., Marshall J., Ohan V., Pollard M. O., et al. (2021). Twelve years of SAMtools and BCFtools. Gigascience 10:giab008. 10.1093/gigascience/giab008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R. C. (2004). MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32 1792–1797. 10.1093/nar/gkh340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goremykin V. V., Lockhart P. J., Viola R., Velasco R. (2012). The mitochondrial genome of Malus domestica and the import-driven hypothesis of mitochondrial genome expansion in seed plants. Plant J. 71 615–626. 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2012.05014.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Group Angiosperm Phylogeny. (2016). An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 181, 1–20. 10.1111/boj.12385 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo W., Zhu A., Fan W., Mower J. P. (2017). Complete mitochondrial genomes from the ferns Ophioglossum californicum and Psilotum nudum are highly repetitive with the largest organellar introns. New Phytol. 213 391–403. 10.1111/nph.14135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackman S. D., Warren R. L., Gibb E. A., Vandervalk B. P., Mohamadi H., Chu J., et al. (2015). Organellar genomes of white spruce (Picea glauca): assembly and annotation. Genome Biol. Evol. 8 29–41. 10.1093/gbe/evv244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kersten B., Faivre Rampant P., Mader M., Le Paslier M. C., Bounon R., Berard A., et al. (2016). Genome sequences of Populus tremula chloroplast and mitochondrion: implications for holistic poplar breeding. PLoS One 11:e0147209. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C. K., Kim Y. K. (2018). The multipartite mitochondrial genome of Fallopia multiflora (Caryophyllales: Polygonaceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 3 155–156. 10.1080/23802359.2018.1437796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y. J., Zhang D. (2018). Molecular control of male fertility for crop hybrid breeding. Trends Plant Sci. 23 53–65. 10.1016/j.tplants.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klingenberg M. (2008). The ADP and ATP transport in mitochondria and its carrier. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1778 1978–2021. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren S., Walenz B. P., Berlin K., Miller J. R., Bergman N. H., Phillippy A. M. (2017). Canu: scalable and accurate long-read assembly via adaptive k-mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Res 27 722–736. 10.1101/gr.215087.116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozik A., Rowan B. A., Lavelle D., Berke L., Schranz M. E., Michelmore R. W., et al. (2019). The alternative reality of plant mitochondrial DNA: one ring does not rule them all. PLoS Genet. 15:e1008373. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1008373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krömer S., Stitt M., Heldt H. W. (1988). Mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation participating in photosynthetic metabolism of a leaf cell. FEBS Lett. 226 352–356. 10.1016/0014-5793(88)81453-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., Choudhuri J. V., Ohlebusch E., Schleiermacher C., Stoye J., Giegerich R. (2001). REPuter: the manifold applications of repeat analysis on a genomic scale. Nucleic Acids Res. 29 4633–4642. 10.1093/nar/29.22.4633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz S., Phillippy A., Delcher A. L., Smoot M., Shumway M., Antonescu C., et al. (2004). Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol. 5:R12. 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagesen K., Hallin P., Rodland E. A., Staerfeldt H. H., Rognes T., Ussery D. W. (2007). RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res. 35 3100–3108. 10.1093/nar/gkm160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei B., Li S., Liu G., Chen Z., Su A., Li P., et al. (2013). Evolution of mitochondrial gene content: loss of genes, tRNAs and introns between Gossypium harknessii and other plants. Plant Syst. Evol. 299 1889–1897. 10.1007/s00606-013-0845-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li H. (2018). Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34 3094–3100. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Durbin R. (2009). Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25 1754–1760. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberatore K. L., Dukowic-Schulze S., Miller M. E., Chen C., Kianian S. F. (2016). The role of mitochondria in plant development and stress tolerance. Free Radic Biol. Med. 100 238–256. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.03.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Wu S., Li A., Ruan J. (2021). SMARTdenovo: a de novo assembler using long noisy reads. Gigabyte 2021 1–9. 10.46471/gigabyte.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X., Kim C. N., Yang J., Jemmerson R., Wang X. (1996). Induction of apoptotic program in cell-free extracts: requirement for dATP and cytochrome c. Cell 86 147–157. 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80085-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignotte B., Vayssiere J. L. (1998). Mitochondria and apoptosis. Eur. J. Biochem. 252 1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minh B. Q., Schmidt H. A., Chernomor O., Schrempf D., Woodhams M. D., von Haeseler A., et al. (2020). IQ-TREE 2: new models and efficient methods for phylogenetic inference in the genomic era. Mol. Biol. Evol. 37 1530–1534. 10.1093/molbev/msaa015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mower J. P. (2020). Variation in protein gene and intron content among land plant mitogenomes. Mitochondrion 53 203–213. 10.1016/j.mito.2020.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt B., Street N. R., Wetterbom A., Zuccolo A., Lin Y. C., Scofield D. G., et al. (2013). The Norway spruce genome sequence and conifer genome evolution. Nature 497 579–584. 10.1038/nature12211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S., Grewe F., Zhu A., Ruhlman T. A., Sabir J., Mower J. P., et al. (2015). Dynamic evolution of Geranium mitochondrial genomes through multiple horizontal and intracellular gene transfers. New Phytol. 208 570–583. 10.1111/nph.13467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen G., Anderson B., Braun H. P., Meyer E. H., Moller I. M. (2020). Mitochondria in parasitic plants. Mitochondrion 52 173–182. 10.1016/j.mito.2020.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice D. W., Alverson A. J., Richardson A. O., Young G. J., Sanchez-Puerta M. V., Munzinger J., et al. (2013). Horizontal transfer of entire genomes via mitochondrial fusion in the angiosperm Amborella. Science 342 1468–1473. 10.1126/science.1246275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Puerta M. V., Garcia L. E., Wohlfeiler J., Ceriotti L. F. (2017). Unparalleled replacement of native mitochondrial genes by foreign homologs in a holoparasitic plant. New Phytol. 214 376–387. 10.1111/nph.14361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schattner P., Brooks A. N., Lowe T. M. (2005). The tRNAscan-SE, snoscan and snoGPS web servers for the detection of tRNAs and snoRNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 33 W686–W689. 10.1093/nar/gki366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siqueira J. A., Hardoim P., Ferreira P. C. G., Nunes-Nesi A., Hemerly A. S. (2018). Unraveling interfaces between energy metabolism and cell cycle in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 23 731–747. 10.1016/j.tplants.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan D. B. (2013). One ring to rule them all? Genome sequencing provides new insights into the ‘master circle’ model of plant mitochondrial DNA structure. New Phytol. 200 978–985. 10.1111/nph.12395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan D. B., Alverson A. J., Chuckalovcak J. P., Wu M., McCauley D. E., Palmer J. D., et al. (2012). Rapid evolution of enormous, multichromosomal genomes in flowering plant mitochondria with exceptionally high mutation rates. PLoS Biol. 10:e1001241. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillich M., Lehwark P., Pellizzer T., Ulbricht-Jones E. S., Fischer A., Bock R., et al. (2017). GeSeq – versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45 W6–W11. 10.1093/nar/gkx391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varre J. S., D’Agostino N., Touzet P., Gallina S., Tamburino R., Cantarella C., et al. (2019). Complete sequence, multichromosomal architecture and transcriptome analysis of the Solanum tuberosum mitochondrial genome. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20:4788. 10.3390/ijms20194788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker B. J., Abeel T., Shea T., Priest M., Abouelliel A., Sakthikumar S., et al. (2014). Pilon: an integrated tool for comprehensive microbial variant detection and genome assembly improvement. PLoS One 9:e112963. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L., Beyer S. T., Cronk Q. C., Walus K. (2011). Delivering high-resolution landmarks using inkjet micropatterning for spatial monitoring of leaf expansion. Plant Methods 7:1. 10.1186/1746-4811-7-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Li D., Yao X., Song Q., Wang Z., Zhang Q., et al. (2019). Evolution and diversification of kiwifruit mitogenomes through extensive whole-genome rearrangement and mosaic loss of intergenic sequences in a highly variable region. Genome Biol. Evol. 11 1192–1206. 10.1093/gbe/evz063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Zhang R., Yun Q., Xu Y., Zhao G., Liu J., et al. (2021). Comprehensive analysis of complete mitochondrial genome of Sapindus mukorossi Gaertn.: an important industrial oil tree species in China. Ind. Crops Prod. 174:114210. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.114210 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z., Du Q., Zhang J., Li B., Zhang D. (2012). Genetic diversity and population structure in Chinese indigenous poplar (Populus simonii) populations using microsatellite markers. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 31 620–632. 10.1007/s11105-012-0527-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Woodson J. D., Chory J. (2008). Coordination of gene expression between organellar and nuclear genomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9 383–395. 10.1038/nrg2348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H., Yao D., Chen Y., Yang W., Zhao W., Gao H., et al. (2020). De novo genome assembly of Populus simonii further supports that Populus simonii and Populus trichocarpa belong to different sections. G3 (Bethesda) 10 455–466. 10.1534/g3.119.400913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Sloan D. B. (2019). Recombination and intraspecific polymorphism for the presence and absence of entire chromosomes in mitochondrial genomes. Heredity (Edinb) 122 647–659. 10.1038/s41437-018-0153-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Q., Cuthbert J. M., Taylor D. R., Sloan D. B. (2015a). The massive mitochondrial genome of the angiosperm Silene noctiflora is evolving by gain or loss of entire chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 10185–10191. 10.1073/pnas.1421397112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Q., Stone J. D., Storchova H., Sloan D. B. (2015b). High transcript abundance, RNA editing, and small RNAs in intergenic regions within the massive mitochondrial genome of the angiosperm Silene noctiflora. BMC Genomics 16:938. 10.1186/s12864-015-2155-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z. Q., Liao X. Z., Zhang X. N., Tembrock L. R., Broz A. (2020). Genomic architectural variation of plant mitochondria—A review of multichromosomal structuring. J. Syst. Evol. 60 160–168. 10.1111/jse.12655 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X., Li J., Guo T., Guo B., Chen Z., An X. (2021). Comprehensive analysis of the R2R3-MYB transcription factor gene family in Populus trichocarpa. Ind. Crops Prod. 168:113614. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2021.113614 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ye N., Wang X., Li J., Bi C., Xu Y., Wu D., et al. (2017). Assembly and comparative analysis of complete mitochondrial genome sequence of an economic plant Salix suchowensis. PeerJ 5:e3148. 10.7717/peerj.3148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu R., Sun C., Zhong Y., Liu Y., Sanchez-Puerta M. V., Mower J. P., et al. (2022). The minicircular and extremely heteroplasmic mitogenome of the holoparasitic plant Rhopalocnemis phalloides. Curr. Biol. 32 470–479 e5. 10.1016/j.cub.2021.11.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Jin X. H., Liu J., Zhao X., Zhou J. H., Wang X., et al. (2018). The Gastrodia elata genome provides insights into plant adaptation to heterotrophy. Nat. Commun. 9:1615. 10.1038/s41467-018-03423-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., Li W., Gao C. W., Zhang D., Gao L. Z. (2019). Deciphering tea tree chloroplast and mitochondrial genomes of Camellia sinensis var. assamica. Sci Data 6:209. 10.1038/s41597-019-0201-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Zhang X., Hu S., Yu J. (2011). An efficient procedure for plant organellar genome assembly, based on whole genome data from the 454 GS FLX sequencing platform. Plant Methods 7:38. 10.1186/1746-4811-7-38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao N., Wang Y., Hua J. (2018). The roles of mitochondrion in intergenomic gene transfer in plants: a source and a pool. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19:547. 10.3390/ijms19020547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The distribution of contig length and read depth in the de novo assembly by Newbler v3.0.

Comparison of P. tremula and P. simonii mitochondrial genomes. PsChr1, PsChr2, and PsChr3 represent the three circular molecules of P. simonii mitogenome, respectively.

Data Availability Statement

The PE and PacBio sequencing data of P. simonii have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) repository under SRR3204721 and SRR9887262, respectively. The multi-circular mitogenome of P. simonii is available in NCBI Nucleotide Database under the GenBank accessions: MZ905370, MZ905371, and MZ905372. All the other mitogenome sequences used in this study are available in the NCBI Genome Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome/organelle/) under the GenBank accessions listed in Supplementary Table 1.