Abstract

Background

Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia (JET) is an arrhythmia originating from the AV junction, which may occur following congenital heart surgery, especially when the intervention is near the atrioventricular junction.

Objective

The aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to compare the effectiveness of amiodarone, dexmedetomidine, and magnesium in preventing JET following congenital heart surgery.

Methods

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement, where 11 electronic databases were searched from the date of inception to August 2020. The incidence of JET was calculated with the relative risk of 95% Confidence Interval (CI). Quality assessment of the included studies was assessed using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement.

Results

Eleven studies met the predetermined inclusion criteria and were included in this meta-analysis. Amiodarone, dexmedetomidine, and magnesium significantly reduced the incidence of postoperative JET [Amiodarone: risk ratio 0.34; I2= 0%; Z=3.66 (P=0.0002); 95% CI 0.19-0.60. Dexmedetomidine: risk ratio 0.34; I2= 0%; Z=4.77 (P<0.00001); 95% CI 0.21-0.52. Magnesium: risk ratio 0.50; I2= 24%; Z=5.08 (P<0.00001); 95% CI 0.39-0.66].

Conclusion

All three drugs have shown promising results in reducing the incidence of JET. Our systematic review found that dexmedetomidine is better in reducing the length of ICU stays as well as mortality. In addition, dexmedetomidine also has the least pronounced side effects among the three. However, it should be noted that this conclusion was derived from studies with small sample sizes. Therefore, dexmedetomidine may be considered as the drug of choice for preventing JET.

Keywords: Amiodarone, congenital heart surgery, dexmedetomidine, junctional ectopic tachycardia, magnesium, prophylaxis

1. INTRODUCTION

Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia (JET) is an arrhythmia originating from the AV junction, which may occur following congenital heart surgery with an incidence between 1.3 and 27.3% [1-3]. A higher incidence of JET was observed when the intervention was in proximity to the atrioventricular node and bundle of His. Despite being a self-limiting tachyarrhythmia, JET, along with atrioventricular dissociation and postoperative systolic and diastolic ventricular dysfunction, may alarmingly diminish cardiac output, thus increasing morbidity and mortality. Several prophylactic schemes, including pharmacologic treatments to lower ventricular rate and re-establish atrioventricular synchrony, have been proposed [4-6]. Most studies used either dexmedetomidine, amiodarone, or magnesium sulfate. However, it has not been established which of the three is the most effective in reducing the incidence of JET. Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis is to compare the effectiveness of each drug in preventing postoperative JET.

2. METHODS

2.1. Search Strategy

This meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis (PRISMA) statement [7]. We did a systematic search in PubMed, Cochrane, ProQuest, Scopus, ScienceDirect, BMJ, EBSCO, Springer, Lancet, PlosOne, and Google Scholar databases using the combination of keywords: (“junctional ectopic tachycardia” AND (“prophylaxis” OR “prophylactic” OR “prevent” OR “prevention”) AND (“amiodarone” OR “magnesium” OR “dexmedetomidine”)). The database search was conducted independently in August 2020 by three reviewers (BM, C, and MS) who contributed equally.

2.2. Study Criteria

The inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) clinical trial or cohort study, either randomized or non-randomized, (ii) assessed the incidence of Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia (JET) in CHD surgeries, and (iii) compared the effectiveness of anti-arrhythmic drugs (either amiodarone, magnesium, or dexmedetomidine) with a controlled group as prophylaxis for JET in CHD surgeries. Furthermore, studies were excluded if at least one of the following criteria was met: (i) study was not published in English or Bahasa Indonesia, (ii) study was in the form of editorial, case report, review, meta-analysis, and (iii) the full-text article was irretrievable.

2.3. Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

The literature screening and reviewing, followed by data extraction were completed independently by three reviewers (BM, C, and MS). The following information was extracted from each article: study characteristics (first author, year of publication, study design, location), patient characteristics (number of patients in each group and total subjects, weight, body surface area, types of congenital heart disease, types of surgery), interventions (drugs used, routes of administration, loading and maintenance dose, duration, timing), clinical outcomes (incidence of JET, length of intensive care unit/ICU stay, mortality rate), adverse events related to intervention, additional treatments for JET, and surgeries associated with JET. Quality assessment of the included studies was assessed by three reviewers (BM, C, and MS) using the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2010 statement [8]. Any disagreements in the data extraction and quality assessment were resolved by discussion between the reviewers to achieve consensus.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Dichotomous outcomes (reported with incidence) were calculated with the relative risk of 95% confidence interval (CI). Random-effects models were used to analyze the data, considering the possible clinical inconsistency in results and the baseline characteristics. P-values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant for hypothesis testing and all statistical analyses were done using REVMAN (version 5.4; Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK) [9].

3. RESULTS

3.1. Search Results

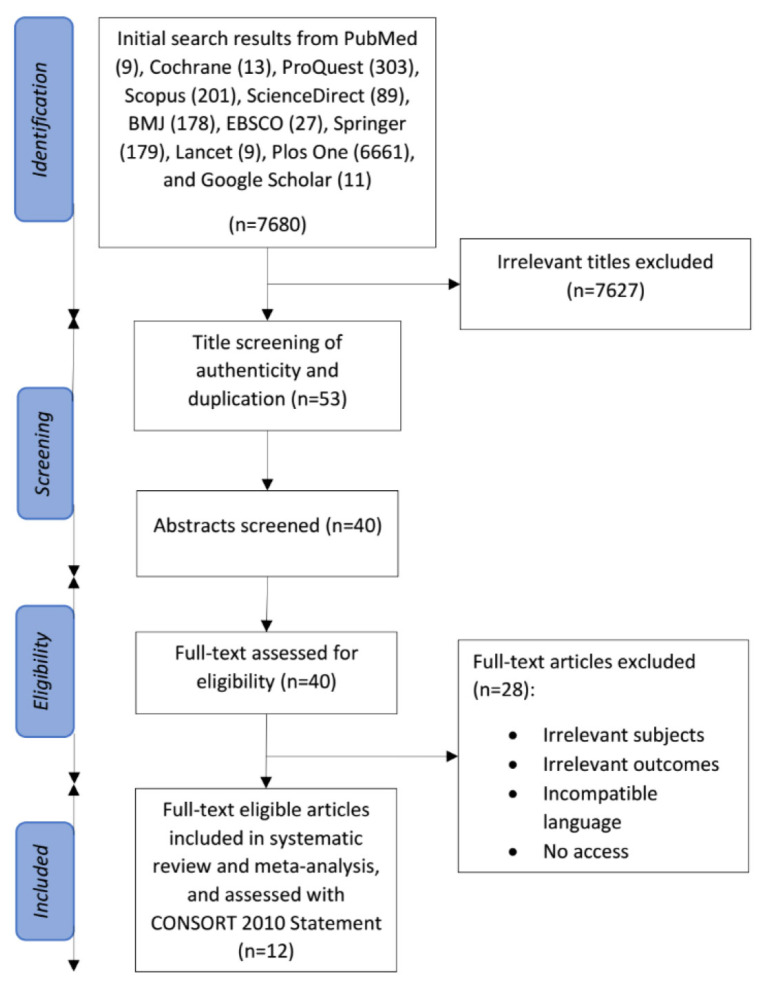

Fig. (1) shows the PRISMA flow diagram for the literature screening and selection process in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The individual systematic searches initially yielded 7680 potential studies from the databases explored. Studies with irrelevant titles were excluded, leaving 53 studies that were screened for authenticity and duplication. Forty studies were eligible for abstract and full-text assessment, from which 29 studies were excluded due to irrelevant subjects and outcomes, incompatible language, and no access to the full-text articles. Finally, eleven studies met the predetermined criteria for inclusion and were included in this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Fig. (1).

Flow diagram of studies included in the systematic review and meta-analysis [7].

3.2. Study Characteristics

The studies included in this systematic review and meta- analysis were published between 2000 and 2019 in the USA, Egypt, and India. The included participants were 3063 patients in total and their characteristics were matched for pediatric patients who underwent surgeries for CHDs. The types of CHDs were mostly Tetralogy of Fallot (ToF) and other defects such as Atrial Septal Defect (ASD), Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD), Atrioventricular Septal Defect (AVSD), critical Pulmonary Stenosis (PS), single ventricle anatomy, outflow obstruction defects, and primary valvular heart defects. ToF repair was the most common type of surgery in the included studies, followed by ASD closure, VSD closure, and other surgeries. The duration of follow-up varied between studies, 8 hours after weaning from CPB [10], 24 hours postoperative [11], 5 days postoperative [12], and 3 months postoperative [13], but other studies did not report the duration of the follow-up. The age and gender distributions of the patients are shown in Table 1. Other detailed characteristics of the studies and patients are also summarized in this table.

Table 1.

Summary of study design and patient characteristics of included studies.

| S.No. | Study (Year) | Study Design | Location | Intervention | No. of Patients | Age | Weight (kg) | BSA (m2/kg) | Type of CHD | Type of Surgery | Duration of Follow-up | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F/M | N | Total | |||||||||||

| 1 | Amrousy (2016) | Prospective study | Tanta University Hospital, Egypt | Control: 5% Aqueous dextrose saline |

23/29 | 52 | 117 | 16.6 ± 7.3 m | 10.9 ± 1.9 | N/A | VSD, ASD, AVSD, ToF, critical PS | ASD closure, VSD closure, ToF repair | 5 d postoperative |

| Amiodarone | 28/37 | 65 | 15.7 ± 6.6 m | 11.5 ± 2.2 | |||||||||

| 2 | Imamura (2012) | Retrospective chart review | Arkansas Children's Hospital, USA | Control: No intervention |

N/A | 43 | 63 | 5.1 ± 7.0 m | 5.9 ± 2.3 | N/A | ToF | Primary ToF repair | N/A |

| Amiodarone | N/A | 20 | 2.7 ± 1.8 m | 5.3 ± 1.5 | |||||||||

| 3 | Jadon (2019) | Prospective study | Advanced Cardiac Centre, Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India | Control: No intervention |

N/A | 25 | 50 | 11.346 ± 8.54 y | N/A | 0.902 ± 0.438 | ToF | Intracardiac repair of ToF | 3 m postoperative |

| Amiodarone | N/A | 25 | 9.16 ± 8.22 y | 0.817 ± 0.425 | |||||||||

| 4 | Amrousy (2017) | Randomized controlled trial | Tanta University Hospital, Egypt | Control: Normal saline |

12/18 | 30 | 90 | 18.3 ± 5.4 m | 12.6 ± 1.7 | N/A | VSD, ASD, AVSD, ToF, critical PS | ASD closure, VSD closure, ToF repair | N/A |

| Dexmedetomidine | 20/40 | 60 | 17.3 ± 4.1 m | 12.4 ± 1.1 | |||||||||

| 5 | Gautam (2017) | Retrospective cohort study | University of Texas Health Houston, USA | Control: No intervention |

15/20 | 35 | 134 | 0.7 (0.0-15.1) y | 7.2 (2.7-86) | N/A | VSD, ToF, AVSD, others | VSD patch closure, AVSD repair, ToF repair/TA patch, ToF repair/no TA patch | N/A |

| Dexmedetomidine | 54/45 | 99 | |||||||||||

| 6 | Kadam (2015) | Randomized controlled trial | Mumbai, India | Control: Fentanyl | 20/27 | 47 | 94 | 120.98 w | 10.19 | N/A | ToF | ToF repair | N/A |

| Dexmedetomidine | 18/29 | 47 | 152.27 w | 11.69 | |||||||||

| 7 | Rajput (2014) | Randomized double-blind controlled trial | New Delhi, India | Control: Placebo (saline) |

34/76 | 110 | 220 | 2.71 ± 1.44 y | 10.62 ± 4.36 | N/A | ToF | Intracardiac repair of ToF | 8 h after weaning from CPB |

| Dexmedetomidine | 24/86 | 110 | 2.77 ± 1,57 y | 10.0 ± 4.12 | |||||||||

| 8 | Dorman (2000) | Randomized double-blind controlled trial | Medical University of South Carolina, USA | Control: Placebo (saline) |

7/8 | 15 | 28 | 4.3 ± 4.1 y | N/A | N/A | N/A | ASD repair, VSD repair, Fontan, Hemi- Fontan | 24 h postoperative |

| Magnesium | 5/8 | 13 | 4.9 ± 4.2 y | ||||||||||

| 9 | He (2015) |

Historical retrospective chart review | Children' National Medical Center, Washington, DC, USA | Control: No intervention |

344/406 | 750 | 1088 | 144 (1-13369) d |

5.5 (1.4-94) | 0.31 (0.13-1.94) |

N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Magnesium | 161/177 | 338 | 196 (0.5-17431) d |

6.3 (2.0-103) |

0.34 (0.16-2.24) |

||||||||

| 10 | He (2018) |

Historical prospective observational cohort study | Children's National Health System, Washington, DC, USA | Control: No intervention |

253/287 | 540 | 1080 | 6 (2-25) m | 6.1 (4.0-10.9) |

0.33 (0.24-0.50) |

Conotruncal/VSD, Single ventricle anatomy, ASD, Outflow obstruction defects, Primary valvular heart defects or miscellaneous | N/A | N/A |

| Magnesium | 262/278 | 540 | 5 (2-24) m | 5.7 (4.0-11.4) |

0.31 (0.25-0.51) |

||||||||

| 11 | Manrique (2010) |

Randomized double-blind controlled trial | Children's Hospital of Pittsburgh, USA | Control: Placebo | 11/18 | 29 | 99 | 3 (0-17) y | 14.6 (2.3-69) |

0.6 (0.18-1.7) |

N/A | Fontan, Sano, ToF repair, ASD closure, Mitral valve repair, VSD closure, Ross procedure, Lung transplant, Septostomy, RV-PA conduit, RVOT repair, AVC repair, Aortic arch and VSD repair, PAPVC repair, Subaortic stenosis repair, VSD and ASD closure, Aortic aneurysm repair, ToF, VSD-MAPCA repair, Arterial switch, Glenn, Truncus repair, Aortic translocation, Aortic valve repair, TAPVR, Mustard modified | N/A |

| Magnesium 25 mg/kg | 17/13 | 30 | 1.54 (0-17) y | 8.1 (2.1-85) | 0.4 (0.17-1.98) |

||||||||

| Magnesium 50 mg/kg | 18/22 | 40 | 1.37 (0-11) y | 7.0 (1.4-51) | 0.36 (0.14-1.4) |

||||||||

BSA, body surface area; CHD, congenital heart disease; F/M, female/male; USA, United States of America; VSD, ventricular septal defect; ASD, atrial septal defect; AVSD, atrioventricular septal defect; ToF, tetralogy of Fallot; PS, pulmonary stenosis; TA, transannular; RV-PA, right ventricle to the pulmonary artery; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; AVC, atrioventricular canal; PAPVC, partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection; MAPCA, major aortopulmonary collateral artery; TAPVR, total anomalous pulmonary venous return; d, days; w, weeks; m, months; y, years; N/A, not available.

All studies compared the effectiveness of anti-arrhythmic drugs as prophylaxis for JET with control (no intervention, placebo/saline, or fentanyl). Three studies [12-14] used amiodarone, four studies [10, 15-17] used dexmedetomidine, and four studies used magnesium [11, 18-20] as an anti-arrhythmic to prevent postoperative JET. In most of the studies, drugs were administered via intravenous (IV) injection or infusion, except for one study, in which amiodarone [13] was administered orally, and in three studies, in which magnesium [18-20] was administered via the Cardiopulmonary Bypass (CPB) circuit. The anti-arrhythmic drugs were administered preoperatively (7 days before surgery) in 1 study [13], intraoperatively at the initiation of the rewarming period in 4 studies [14, 18-20] and immediately after cessation of CPB in 1 study [11], both postoperatively and intraoperatively at the time of anesthesia induction in 2 studies [12, 15], after the insertion of arterial blood pressure (ABP) and Central Venous Pressure (CVP) monitoring lines in 2 studies [10, 17], and before incision, after CPB in 1 study [16].

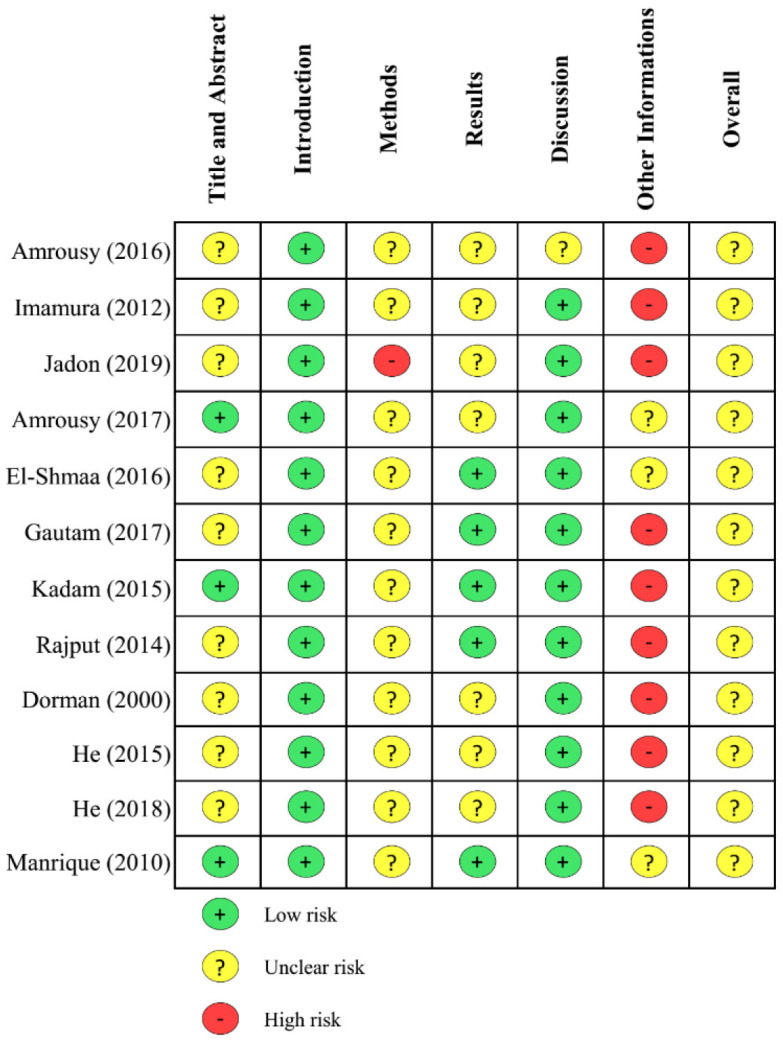

Amiodarone was continuously infused at a rate of 10-15 μg/kg/min for 72 hours after a loading dose of 5 mg/kg (duration of 20 or 30 min) in one study [12], infused at a rate of 2 mg/kg/d for 2 days without a loading dose in 1 study [14], and administered orally with a dose of 2 mg/kg in 1 study [13]. Dexmedetomidine was continuously infused at a rate of 0.5 or 0.75 μg/kg/h (duration: 48 h, 72 h, or up to weaning from ventilator) after a loading dose of 0.5 or 1 μg/kg (duration of 10, 15 or 20 minutes) in 3 studies [10, 15, 17] or infused intraoperatively at a rate of 1 μg/kg/h, continued postoperatively at a rate of 0.5-1 μg/kg/h (titrated until level of sedation for 12 hours) [16]. A loading dose of magnesium was administered via IV (30 mg/kg) in one study [11] and via the CPB circuit (25 or 50 mg/kg) in 3 studies [18-20]. The quality assessment of the included studies is shown in detail in Fig. (2).

Fig. (2).

Summary of quality assessment using the CONSORT statement [8]. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3.3. Effect of Anti-arrhythmic Drugs on Incidence of JET

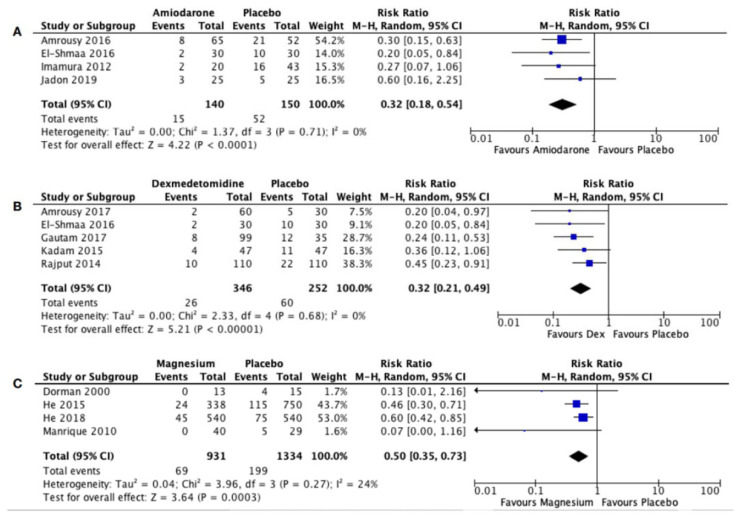

The incidence of JET is lower in the amiodarone group (12.3%, 10%, and 12%) compared to the control group (40.4%, 37%, and 20%) in the studies conducted by Amrousy et al. (2016), Imamura et al. (2012), and Jadon et al. (2019), respectively [12-14]. Studies using dexmedetomidine also showed lower incidences of JET in the dexmedetomidine group (3.3%, 8%, 8.51%, and 9.1%) compared to the control group (16.7%, 35%, 23.4%, and 20%) in the studies done by Amrousy et al. (2017), Gautam et al. (2017), Kadam et al. (2015), and Rajput et al. (2014), respectively [10, 15-17]. The incidence of JET was significantly reduced by amiodarone [12-14] (3 studies; relative risk 0.34, 95% CI 0.19-0.60; P=0.0002; I2 = 0%; Fig. 3A) and dexmedetomidine [10, 15-17] (4 studies; relative risk 0.33, 95% CI 0.21-0.52; P<0.00001; I2 = 0%; Fig. 3B).

Fig. (3).

Forest plot for the incidence of Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia after administration of (A) Amiodarone, (B) Dexmedetomidine, and (C) Magnesium [9]. CI: Confidence Interval; M-H: Mantel-Haenszel.

There was a significant difference in the incidence of JET between the magnesium group and the control group [11, 18-20] (4 studies; relative risk 0.50, 95% CI 0.39-0.66; P<0.00001; I2 = 24%; Fig. 3C). Incidences of JET were lower in the magnesium group (0%, 7.1%, and 8%) than in the control group (27%, 15.3%, and 14%) in the studies conducted by Dorman et al. (2000), He et al. (2015), and He et al. (2018) [11, 18, 19]. Manrique et al. (2010) compared the use of magnesium in two different doses (25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg) and found that the incidence of JET was the lowest in the magnesium 50 mg/kg group (0%), followed by 25 mg/kg of magnesium (6.7%), and the highest in the control group (17.9%) [20].

3.4. Effect of Anti-Arrhythmic Drugs on Length of ICU Stay

Amrousy et al. (2016) reported that the length of ICU stay was shorter in the amiodarone group (2.8 ± 2.1 d) compared to the control group (3.7 ± 2.9 d) [12]. Imamura et al. (2012) reported otherwise, where the ICU stay was longer in the amiodarone group (7.2 ± 4.9 d) than in the control group (7.0 ± 5.0 d) [14]. Amrousy et al. (2017) reported shorter ICU stay in the dexmedetomidine group (1.8 ± 0.7 d) compared to the control group (4.2 ± 1.2 d) [15]. Rajput et al. (2014) also reported shorter ICU stay in the dexmedetomidine group (1.18 ± 0.37 d) compared to the control group (1.68 ± 0.42 d) [10]. However, the length of ICU stay was longer in the dexmedetomidine group (4.36 ± 2.68 d) compared to the control group (4.12 ± 2.11 d) in the study by Kadam et al. (2015) [17]. The study by He et al. (2015) reported that the length of stay in the magnesium group (3 (1-198) d) was shorter than in the control group (4 (1-212) d) [18]. On the other hand, Manrique et al. (2010) showed that the ICU stay was longer in the magnesium group (1.30 ± 1.13 d in magnesium 25 mg/kg and 1.23 ± 0.91 d in magnesium 50 mg/kg) compared to the control group (1.08 ± 0.75 d) [20].

3.5. Effect of Anti-arrhythmic Drugs on Mortality

The mortality rate was lower in the amiodarone group (3.1%) compared to the control group (7.7%) in the study by Amrousy et al. (2016) [12]. On the other hand, Imamura et al. (2012) showed no mortality in both the amiodarone or control group [14]. Amrousy et al. (2017) reported a lower mortality rate in the dexmedetomidine group (1.7%) compared to the control group (6.7%) [15]. However, Kadam et al. (2015) showed similar mortality rates between the dexmedetomidine and the control group (2.2% and 2.1%, respectively) [17]. In a study by Rajput et al. (2014), there was no mortality in both the dexmedetomidine and the control group [10]. One study on magnesium by He et al. (2015) reported a lower mortality rate in the magnesium group (3.6%) than in the control group (5.3%) [18].

3.6. Adverse Events

The most reported adverse events in the included studies were bradycardia and hypotension, which were experienced by only a small percentage of patients. A study by Amrousy et al. (2016) reported adverse events with the use of amiodarone, including bradycardia (6.2%) [12]. Bradycardia was experienced by 12% of patients receiving oral amiodarone in the study by Jadon et al. (2019) [13]. On the other hand, Imamura et al. (2012) reported no adverse event on both the amiodarone and the control group [14]. Bradycardia and hypotension were reported by Amrousy et al. (2017) to be lower in patients receiving dexmedetomidine (1.7%) than in patients receiving normal saline (3.3%) [15]. Manrique et al. (2010) reported that there were no adverse events in both the control and the magnesium group [20]. Other studies did not provide information regarding adverse events which might occur during their experiments (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of interventions and clinical outcomes in the included studies.

| S.No. | Study (Year) | Drug Used (Route) | Loading Dose (Duration) | Maintenance Dose (Duration) | Incidence of Intra-/Postoperative JET | Outcome | Adverse Events (%) | Timing of Drug Administration | Additional Treatment for JET | Surgery Associated with JET (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of ICU stay (days) | Mortality (%) | ||||||||||

| 1 | Amrousy (2016) | Control | - | - | 21/52 (40.4%) | 3.7 ± 2.9 | 7.7 | Bradycardia (3.8), hypotension (3.8) | At the time of anesthesia induction and postoperative | N/A | VSD closure (6), ASD closure (3), VSD +ASD closure (2), ToF repair (5), AVSD repair (3), PS (2) |

| AMIO (IV) | 5 mg/kg diluted in 5% aqueous dextrose solution (30 minutes) | 10-15 μg/kg/min 72 h postoperatively | 8/65 (12.3%) | 2.8 ± 2.1 | 3.1 | Bradycardia (6.2), hypotension (3.1) | |||||

| 2 | Imamura (2012) | Control | - | - | 16/43 (37%) | 7.0 ± 5.0 | - | - | Intraoperative (at the time of rewarming during CPB) | amiodarone | Primary ToF repair (18) |

| AMIO (IV) | - | 2mg/kg/d (2 d) | 2/20 (10%) | 7.2 ± 4.9 | |||||||

| 3 | Jadon (2019) | Control | - | - | 5/25 (20%) | N/A | N/A | - | Preoperative (7 d before surgery) |

amiodarone IV | Intracardiac repair of ToF (8) |

| AMIO (oral) | 2mg/kg | - | 3/25 (12%) | Bradycardia (12) | |||||||

| 4 | Amrousy (2017) | Control | - | - | 5/30 (16.7%) | 4.2 ± 1.2 | 6.7 | Bradycardia (3.3), hypotension (3.3) | At the time of anesthesia induction and postoperative | N/A | N/A |

| DEX (IV) | 0.5 μg/kg diluted in 100 mL normal saline (20 minutes) | 0.5 μg/kg/h 48 h postoperatively | 2/60 (3.3%) | 1.8 ± 0.7 | 1.7 | Bradycardia (1.7), hypotension (1.7) | |||||

| 5 | Gautam (2017) | Control | - | - | 12/35 (35%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Intraoperative (before incision, after CPB) and postoperative | Anti-arrhythmic use, cooling treatment, atrial overdrive pacing | VSD patch closure (5), AVSD repair (2), ToF repair/TA patch (7), ToF repair/no TA patch (3), other (3) |

| DEX (IV) | - | intraoperative:1 μg/kg/h, postoperative: 0.5-1μg/kg/h titrated until level of sedation (12 h) | 8/99 (8%) | ||||||||

| 6 | Kadam (2015) | Control | - | - | 11/47 (23.40%) | 4.12 ± 2.11 | 2.1 | N/A | Intraoperative (after insertion ABP and CVP monitoring lines) and postoperative | N/A | N/A |

| DEX (IV) | 1 μg/kg (15 minutes) |

0.75 μg/kg/h during CPB and 48 h postoperative | 4/47 (8.51%) | 4.36 ± 2.68 | 2.2 | ||||||

| 7 | Rajput (2014) | Control | - | - | 22/110 (20%) | 1.68 ± 0.42 | - | N/A | Intraoperative (after insertion ABP and CVP monitoring lines) and postoperative | mild hypothermia, reduction in inotropes, magnesium, digoxin, and amiodarone | Intracardiac repair of ToF (32) |

| DEX (IV) | 0.5 μg/kg (10 minutes) |

0.5 μg/kg/h (throughout operation up to weaning from ventilator in ICU) | 10/110 (9.1%) | 1.18 ± 0.37 | |||||||

| 8 | Dorman (2000) | Control | - | - | 4/15 (27%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Intraoperative (immediately after cessation of CPB) | magnesium 25-50 mg/kg | ASD repair (1), VSD repair (1), Fontan (1), Hemi-Fontan (1) |

| Mg (IV) | 30 mg/kg as 5% solution in saline (10 minutes) | 0/13 (0%) | potassium 0.3 mEq/kg (2) | ||||||||

| esmolol infusion + hypothermia (1) | |||||||||||

| 9 | He (2015) |

Control | - | - | 115/750 (15.3%) | 4 (1-212) | 5.3 | N/A | Intraoperative (at the beginning of rewarming) | N/A | N/A |

| Mg sulfate (into CPB circuit) | 25 mg/kg | 24/338 (7.1%) | 3 (1-198) | 3.6 | |||||||

| 10 | He (2018) |

Control | - | - | 75/540 (14%) | N/A | N/A | N/A | Intraoperative (administered into CPB circuit at the beginning of rewarming) | N/A | N/A |

| Mg sulfate (into CPB circuit) | 50 mg/kg | - | 45/540 (8%) | ||||||||

| 11 | Manrique (2010) | Control | - | - | 5/29 (17.9%) | 1.08 ± 0.75 | N/A | - | Intraoperative (at the initiation of the rewarming period) | cooling to 34°C + amiodarone IV (5 mg/kg over 30 minutes, followed by infusion of 15 mg/kg/day) | Fontan (1), Sano (1), ToF repair (1), VSD closure (1), Lung transplant (1), RV-PA conduit (1), Aortic arch, and VSD repair (1) |

| Mg sulfate (into CPB circuit) | 25 mg/kg (max 2 g) | 2/30 (6.7%) | 1.30 ± 1.13 | ||||||||

| 50 mg/kg (max 2 g) | 0/40 (0%) | 1.23 ± 0.91 | |||||||||

JET, Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia; ICU, Intensive Care Unit; AMIO, Amiodarone; DEX, Dexmedetomidine; Mg, Magnesium; IV, Intravenous; VSD, Ventricular Septal Defect; ASD, Atrial Septal Defect; ToF, Tetralogy of Fallot; AVSD, Atrioventricular Septal Defect; PS, Pulmonary Stenosis; CPB, Cardiopulmonary Bypass; TA, Transannular; ABP, Arterial Blood Pressure; CVP, Central Venous Pressure; RV-PA, Right Ventricle to the pulmonary artery; h, hours; d, days; N/A, not available.

3.7. Surgery Associated with JET and Additional Treatment for JET

The most common surgeries associated with JET was ToF repair in 1 patient [20], 5 patients [12], 8 patients [13], 10 patients (7 with and 3 without transannular/TA patch) [16], 18 patients [14], and 32 patients [10]. Amrousy et al. (2016) also reported VSD closure (6), ASD closure (3), ASD and VSD closure (2), AVSD repair (3), and PS (2) associated with JET [12]. The study by Gautam et al. (2017) found that 5, 2 and 3 patients who developed JET had undergone VSD patch closure, AVSD repair, and other surgeries, respectively [16]. Each of the four patients in Dorman et al. (2000) who later developed JET had undergone ASD repair, VSD repair, Fontan, and Hemi-Fontan [11]. Manrique et al. (2010) also reported different types of surgeries in each patient that developed JET, which were Fontan, Sano, VSD closure, lung transplant, right ventricle-pulmonary artery (RV-PA) conduit, and aortic arch with VSD repair [20].

In the event that JET occurred postoperatively, two studies treated it using amiodarone [13, 14]. One other study also used intravenous amiodarone (5 mg/kg over 30 min, followed by infusion at a rate of 15 mg/kg/day) combined with cooling to 34oC [20]. Gautam et al. (2017) treated JET with anti-arrhythmic drugs, cooling treatment, and atrial overdrive pacing [16]. Magnesium was used in two studies as treatment of JET: one study [10] combined magnesium with mild hypothermia, while the other [11] used magnesium with a dose of 25-50 mg/kg and potassium of 0.3 mEq/kg in 2 patients, as well as an esmolol infusion combined with hypothermia in one patient (Table 2).

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Type of Heart Surgery in Correlation to the JET Incidence

JET is a common complication of congenital heart surgery, especially in those that took place in the area adjacent to the AV node. Rekawek et al. (2007) found that among 21 of their patients who experienced post-surgical JET, five of them had perimembranous ventricular septal defects, five had complete atrioventricular septal defects, two had Tetralogy of Fallot, and two had transposition of the great arteries with ventricular septal defects [21]. This result was consistent with that of Amrousy et al. (2016), in which 6 patients with VSD closure experienced JET, followed by 5 patients with ToF repair [12]. However, Abdelaziz et al. (2014) found that JET was most commonly found after ToF repair (52.0% of all ToF repairs), followed by Senningoperation and AV canal repair [1]. This result was similar to a study by Gautam et al. (2017) [16], in which 10 ToF patients experienced JET, followed by 5 patients with VSD repair.

JET seems to occur more frequently with ToF and VSD repair, where there is mechanical trauma around the area of the proximal conduction tissue caused by suture placement or stretch injury [2]. The direct trauma or infiltration of blood and inflammatory cells to the AV node (either to the central fibrous body or the proximal conduction system) may produce irritable foci and is thought to be the underlying mechanism of enhanced automaticity of JET [22, 23]. In addition, multiple approaches are usually required for a repair. Thus, the accumulation of potential trauma may have an additive effect on JET [23, 24]. For ToF repair, relieving right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (by resecting muscle bundles within the right ventricle) or VSD closure requires an approach from the right atrium, which needs more traction on the heart. The same goes for AVSD repair, where traction is applied to obtain considerable trans-atrial exposure [4].

4.2. Prophylactic Drugs in JET

4.2.1. Amiodarone

Amiodarone is a class III antiarrhythmic agent which blocks sodium and potassium channel, with a mild antisympathetic action. It is prophylactically given to patients who underwent primary ToF repair with a reduction of JET incidence [25-27]. The standard dosing regimen is intravenous 300 mg in 20 minutes to 2 hours through central vein access followed by 900 mg over the next 24 hours with the maximum dose of 1200 mg in 24 hours [13, 14]. Imamura et al. (2012) found no significant adverse events following prophylactic IV amiodarone prior to small subjects, lower doses of IV amiodarone, and shorter study duration [14]. In our meta- analysis involving 3 studies with 200 subjects undergoing cardiac surgery, preoperative amiodarone could reduce the incidence of JET.

4.2.2. Dexmedetomidine

Dexmedetomidine is a highly selective α2-adrenoceptor agonist, used mainly for its sedative and analgesic effects [28]. However, a growing amount of literature shows that dexmedetomidine has anti-arrhythmic effects as well, in which it exerts depressive effects on the AV node. Compared to amiodarone, dexmedetomidine has less pronounced side effects, which include hypotension, nausea, bradycardia, and dry mouth [29]. A loading dose of 1 µg/kg in 10 minutes is recommended, followed by a post-operative maintenance dose of 0.6 µg/kg/h, titrated up to 1 µg/kg/h [28].

Amrousy et al. (2017) found that the use of dexmedetomidine significantly reduced the incidence of JET from 16.7% to 3.3% [15]. These findings were consistent with the studies by Gautam et al. (2017), Kadam et al. (2015), and Rajput et al. (2014), where the incidence of JET reduced by 6-27% [10, 16, 17]. In addition, Amrousy et al. (2017) also found that the length of ICU stay was significantly reduced by 2-3 days with the use of dexmedetomidine [15]. In fact, compared to amiodarone and magnesium, dexmedetomidine had the best effect in reducing ICU stay. The same goes for mortality rates, where Amrousy et al. (2017) found that mortality rates of 6.7% reduced to as much as 1.7%[15]. Three studies [10, 16, 17] reported that there were no adverse effects with the use of dexmedetomidine, except in one study by Amrousy et al. (2017) [15], where only 1.7% (1 out of 60 patients) experienced bradycardia and hypotension.

4.2.3. Magnesium

Intravenous magnesium has been widely used as a preventive measure and treatment for cardiac arrhythmias due to its minimal negative inotropic effect and high therapeutic- to-toxic ratio. Magnesium ions regulate the functioning of ion channels, especially the potassium channels in cardiac cells, where they allow potassium ions to enter the cell more readily. Thus, a magnesium deficiency can cause reduced intracellular potassium, shifting the membrane potential of cardiac cells and potentially causing cardiac arrhythmias [30]. An infusion of magnesium helps to stabilize membrane potential and reduce catecholamine-induced pacemaker activity, which may be the reason for reduced automaticity, thus preventing the occurrence of JET [11].

He et al. (2015) stated that there were no significant differences in the length of ICU stay (p=0.458) and mortality rates (p=0.247) between the group that was given magnesium, and the group that was not [18]. These results were consistent with that of Manrique et al. (2010), where the use of magnesium had no significant effect on mortality (p=0.500) [20]. However, four studies stated that the incidence of postoperative JET reduced significantly by 6-27% with the use of magnesium as prophylaxis for JET [11, 18-20]. Manrique et al. (2010) compared two different doses of magnesium infusion - 25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg. Their results suggested that the effect of magnesium may be dose-related [20]. However, their study used a small sample size and the findings were contradicted to that of He et al. (2018) [19], where they also compared 25 mg/kg and 50 mg/kg of magnesium and found no significant reduction in JET risk with the use of a higher dose (p=0.792).

4.4. Comparison Between Prophylactic Drugs for JET

This meta-analysis found that all three drugs significantly reduce the incidence of postoperative JET (amiodarone: RR 0.31, 95% CI 0.18-0.52; dexmedetomidine: RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.21-0.49; magnesium: RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.39-0.66; Fig. 3). However, Amrousy et al. (2017) [15] reported that dexmedetomidine significantly lowers the mortality rate of patients with congenital heart surgery (from 6.7% to 1.7%), whereas other studies showed that amiodarone and magnesium do not lower the mortality rate significantly. In addition, dexmedetomidine and amiodarone also reduce the length of ICU stay by 1-3 days, while magnesium does not reduce the length of ICU stay significantly.

LIMITATION

The studies included in this systematic review and meta- analysis were not all randomized controlled trials, some were cohort studies as well. There were no studies that directly compare the effects of amiodarone, dexmedetomidine, and magnesium with the same baseline characteristics. Furthermore, data on the length of ICU stay and mortality were not adequate to be included in the meta-analysis. The mode of administration and dosage of drugs also vary from one study to another, which may affect the final results. Further studies to address these limitations are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank all those who have supported them in this systematic review and meta-analysis. The authors are especially grateful to the Department of Cardiology and Vascular Medicine, Faculty of Medicine Universitas Indonesia, for their guidance in teaching the authors about research methodology, as well as their assistance in the proofreading of this article.

CONCLUSION

From our meta-analysis, we found that all three drugs are able to reduce the incidence of JET. Our systematic review found that dexmedetomidine is better in reducing the length of ICU stays as well as mortality. In addition, dexmedetomidine also has the least pronounced side effects among the three. However, it should be noted that this conclusion was derived from studies with small sample sizes. However, dexmedetomidine may be considered as the drug of choice for preventing JET.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

STANDARD OF REPORTING

PRISMA guidelines were followed.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available on the publisher’s website along with the published article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdelaziz O., Deraz S. Anticipation and management of junctional ectopic tachycardia in postoperative cardiac surgery: Single center experience with high incidence. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2014;7(1):19–24. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.126543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mildh L., Hiippala A., Rautiainen P., Pettilä V., Sairanen H., Happonen J.M. Junctional ectopic tachycardia after surgery for congenital heart disease: Incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2011;39(1):75–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chelo D., Ateba N.A., Tchoumi J.C.T., et al. Early postoperative arrhythmias after cardiac surgery in children at the shisong cardiac center, Cameroon. Delta Med Col J. 2018;6(1):22–28. doi: 10.3329/dmcj.v6i1.35964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dodge-Khatami A., Miller O.I., Anderson R.H., Goldman A.P., Gil-Jaurena J.M., Elliott M.J., Tsang V.T., De Leval M.R. Surgical substrates of postoperative junctional ectopic tachycardia in congenital heart defects. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2002;123(4):624–630. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.121046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pfammatter J-P., Bachmann D.C.G., Wagner B.P., Pavlovic M., Berdat P., Carrel T., Pfenninger J. Early postoperative arrhythmias after open-heart procedures in children with congenital heart disease. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 2001;2(3):217–222. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200107000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yildirim S.V., Tokel K., Saygili B., Varan B. The incidence and risk factors of arrhythmias in the early period after cardiac surgery in pediatric patients. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2008;50(6):549–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., PRISMA Group Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010 doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Manager R. Version 5.4, The Cochrane Collaboration. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rajput R.S., Das S., Makhija N., Airan B. Efficacy of dexmedetomidine for the control of junctional ectopic tachycardia after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. Ann. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2014;7(3):167–172. doi: 10.4103/0974-2069.140826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorman B.H., Sade R.M., Burnette J.S., Wiles H.B., Pinosky M.L., Reeves S.T., Bond B.R., Spinale F.G. Magnesium supplementation in the prevention of arrhythmias in pediatric patients undergoing surgery for congenital heart defects. Am. Heart J. 2000;139(3):522–528. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(00)90097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amrousy D.E., Elshehaby W., Feky W.E., Elshmaa N.S. Safety and efficacy of prophylactic amiodarone in preventing early Junctional Ectopic Tachycardia (JET) in children after cardiac surgery and determination of its risk factor. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2016;37(4):734–739. doi: 10.1007/s00246-016-1343-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jadon M., Kynta R.L., Thingnam S.K.S. Effectiveness of oral amiodarone in prevention of perioperative junctional ectopic tachycardia in patients of tetralogy of fallot undergoing intracardiac repair. Int. J. Sci. Res. (Ahmedabad) 2019;8(10):81–83. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imamura M., Dossey A.M., Garcia X., Shinkawa T., Jaquiss R.D. Prophylactic amiodarone reduces junctional ectopic tachycardia after tetralogy of Fallot repair. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2012;143(1):152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El Amrousy D.M., Elshmaa N.S., El-Kashlan M., Hassan S., Elsanosy M., Hablas N., Elrifaey S., El-Feky W. Efficacy of prophylactic dexmedetomidine in preventing postoperative junctional ectopic tachycardia after pediatric cardiac surgery. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3):e004780. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautam N.K., Turiy Y., Srinivasan C. Preincision initiation of dexmedetomidine maximally reduces the risk of junctional ectopic tachycardia in children undergoing ventricular septal defect repairs. J. Cardiothorac. Vasc. Anesth. 2017;31(6):1960–1965. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2017.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kadam S.V., Tailor K.B., Kulkarni S., Mohanty S.R., Joshi P.V., Rao S.G. Effect of dexmeditomidine on postoperative junctional ectopic tachycardia after complete surgical repair of tetralogy of Fallot: A prospective randomized controlled study. Ann. Card. Anaesth. 2015;18(3):323–328. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.159801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He D., Sznycer-Taub N., Cheng Y., McCarter R., Jonas R.A., Hanumanthaiah S., Moak J.P. Magnesium lowers the incidence of postoperative junctional ectopic tachycardia in congenital heart surgical patients: Is there a relationship to surgical procedure complexity? Pediatr. Cardiol. 2015;36(6):1179–1185. doi: 10.1007/s00246-015-1141-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He D., Aggarwal N., Zurakowski D., Jonas R.A., Berul C.I., Hanumanthaiah S., Moak J.P. Lower risk of postoperative arrhythmias in congenital heart surgery following intraoperative administration of magnesium. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018;156(2):763–770.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2018.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manrique A.M., Arroyo M., Lin Y., El Khoudary S.R., Colvin E., Lichtenstein S., Chrysostomou C., Orr R., Jooste E., Davis P., Wearden P., Morell V., Munoz R. Magnesium supplementation during cardiopulmonary bypass to prevent junctional ectopic tachycardia after pediatric cardiac surgery: A randomized controlled study. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2010;139(1):162–169.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.07.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rekawek J., Kansy A., Miszczak-Knecht M., Manowska M., Bieganowska K., Brzezinska-Paszke M., Szymaniak E., Turska-Kmieć A., Maruszewski P., Burczyński P., Kawalec W. Risk factors for cardiac arrhythmias in children with congenital heart disease after surgical intervention in the early postoperative period. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2007;133(4):900–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kylat R.I., Samson R.A. Junctional ectopic tachycardia in infants and children. J. Arrhythm. 2019;36(1):59–66. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alasti M., Mirzaee S., Machado C., Healy S., Bittinger L., Adam D., Kotschet E., Krafchek J., Alison J. Junctional ectopic tachycardia (JET). J. Arrhythm. 2020;36(5):837–844. doi: 10.1002/joa3.12410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Batra A.S., Mohari N. Junctional ectopic tachycardia: Current strategies for diagnosis and management. Prog. Pediatr. Cardiol. 2013;35:49–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ppedcard.2012.11.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vassallo P., Trohman R.G. Prescribing amiodarone: An evidence-based review of clinical indications. JAMA. 2007;298(11):1312–1322. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.11.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Epstein A.E., Olshansky B., Naccarelli G.V., Kennedy J.I., Jr, Murphy E.J., Goldschlager N. Practical management guide for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Am. J. Med. 2016;129(5):468–475. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Florek J.B., Girzadas D. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2020. Amiodarone. updated 2020 Aug 23. Internet. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482154/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.Weerink M.A.S., Struys M.M.R.F., Hannivoort L.N., Barends C.R.M., Absalom A.R., Colin P. Clinical pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dexmedetomidine. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2017;56(8):893–913. doi: 10.1007/s40262-017-0507-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cools E., Missant C. Junctional ectopic tachycardia after congenital heart surgery. Acta Anaesthesiol. Belg. 2014;65(1):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cieslewicz A., Jankowski J., Korzeniowska K., et al. The role of magnesium in cardiac arrhythmias. J. Elem. 2012;18(2):317–327. doi: 10.5601/jelem.2013.18.2.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material is available on the publisher’s website along with the published article.