Abstract

A chemostat coculture of the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio oxyclinae and the facultatively aerobic heterotroph Marinobacter sp. strain MB was grown for 1 week under anaerobic conditions at a dilution rate of 0.05 h−1. It was then exposed to an oxygen flux of 223 μmol min−1 by gassing the growth vessel with 5% O2. Sulfate reduction persisted under these conditions, though the amount of sulfate reduced decreased by 45% compared to the amount reduced during the initial anaerobic mode. After 1 week of growth under these conditions, sulfate was excluded from the incoming medium. The sulfate concentration in the growth vessel decreased exponentially from 4.1 mM to 2.5 μM. The coculture consumed oxygen effectively, and no residual oxygen was detected during either growth mode in which oxygen was supplied. The proportion of D. oxyclinae cells in the coculture as determined by in situ hybridization decreased from 86% under anaerobic conditions to 70% in the microaerobic sulfate-reducing mode and 34% in the microaerobic sulfate-depleted mode. As determined by the most-probable-number (MPN) method, the numbers of viable D. oxyclinae cells during the two microaerobic growth modes decreased compared to the numbers during the anaerobic growth mode. However, there was no significant difference between the MPN values for the two modes when oxygen was supplied. The patterns of consumption of electron donors and acceptors suggested that when oxygen was supplied in the absence of sulfate and thiosulfate, D. oxyclinae performed incomplete aerobic oxidation of lactate to acetate. This is the first observation of oxygen-dependent growth of a sulfate-reducing bacterium in the absence of either sulfate or thiosulfate. Cells harvested during the microaerobic sulfate-depleted stage and exposed to sulfate and thiosulfate in a respiration chamber were capable of anaerobic sulfate and thiosulfate reduction.

Ecological evidence indicates that high levels of sulfate-reducing bacteria and high rates of sulfate reduction occur in the oxic layers of cyanobacterial mats (3, 5, 6, 11, 20, 21, 23, 24, 25). On the other hand, sulfate-reducing bacteria have been traditionally considered strict anaerobes (22). No pure culture of sulfate-reducing bacteria is known to grow or to reduce sulfate in the presence of high concentrations of oxygen. Although some strains have been shown to reduce oxygen (8, 19), no growth by aerobic respiration has been demonstrated even for the oxygen-tolerant isolates (17). However, Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough was found to be capable of slow linear aerobic growth in sulfate-containing medium in the presence of very low concentrations of oxygen (up to 0.07% O2 in the gassing mixture, corresponding to 0.95 μM) (14).

Desulfovibrio oxyclinae was isolated from the oxic zone of a hypersaline cyanobacterial mat from Solar Lake in Sinai, Egypt, and was previously shown to be capable of utilizing oxygen as a preferred electron acceptor instead of sulfate (16). This organism was previously reported to grow in close association with a microaerophilic heterotrophic Arcobacter sp. (24). D. oxyclinae was capable of growing and reducing sulfate in a defined coculture with a facultatively aerobic heterotroph, Marinobacter sp. strain MB, in a continuous culture system under gassing with increasing oxygen concentrations up to 20% (P. Sigalevich, M. V. Baev, A. Teske, and Y. Cohen, submitted for publication). It was, however, not clear to what degree the growth of D. oxyclinae in the presence of oxygen was maintained by aerobic respiration. In order to determine this, electron acceptors other than molecular oxygen were to be excluded from the growth medium. In this paper we report for the first time the growth of D. oxyclinae in a chemostat coculture with Marinobacter sp. strain MB under microaerobic, sulfate- and thiosulfate-depleted conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth medium.

A synthetic growth medium which was used in all continuous culture experiments contained (per liter) 50.0 g of NaCl, 1.0 g of KCl, 2.5 g of MgCl2 · 6H2O, 0.5 g of K2HPO4, 1.0 g of NH4Cl, 0.08 g of CaCl2 · 2H2O, 1.0 g of sodium citrate, 1 ml of a vitamin solution, 1 ml of a vitamin B12 solution, 1 ml of a thiamine solution, 10 ml of an ascorbate-thioglycolate reducing solution, (27), and 1 ml of SL7 mineral solution (2). Lactate (19 mM) was used as a carbon source. For sulfate-reducing growth modes, sodium sulfate was added as a sterile stock solution to a final concentration of 8 mM.

Bacterial strains.

D. oxyclinae P1B (= DSM 11498) was isolated previously in our laboratory from the oxic zone of Solar Lake mats (16). Marinobacter sp. strain MB (M. V. Baev, A. Teske, P. Sigalevich, and Y. Cohen, unpublished data) was obtained by us from the same environment. A comparison of 16S ribosomal DNA sequences (positions 1 to 1350) demonstrated that this strain exhibited 99% sequence similarity with the type strain of Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus (12).

Continuous culture experiments.

Growth experiments were carried out in a 0.45-liter laboratory fermentor (Bioflo; New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, N.J.) equipped with a pH control and oxygen-monitoring device (B. Braun, Melsungen, Germany). The pH was maintained at 7.4 ± 0.2 by titration with 1 N HCl and 1 N NaOH. The concentration of dissolved oxygen in the growth vessel was monitored with a polarimetric oxygen electrode (Ingold, Urdorf, Switzerland). The mixing rate was 200 rpm. The temperature was maintained at 35°C.

For the anaerobic growth mode, the culture was gassed with nitrogen. For the microaerobic modes, the growth vessel was gassed with a mixture containing 90% N2, 5% O2, and 5% CO2. The rate of supply of gas in all cases was 0.1 liter min−1.

In preparation for the continuous culture experiment, Marinobacter sp. strain MB was grown aerobically overnight on 20 mM acetate. D. oxyclinae was grown anaerobically on 20 mM lactate and 10 mM Na2SO4 for 2 days. Each culture was harvested by centrifugation, washed with the synthetic medium with no carbon source added, and diluted to the same turbidity. The fermentor was then inoculated with equal volumes of the Marinobacter sp. strain MB and D. oxyclinae cell suspensions. After 24 h of anaerobic batch incubation, the medium flow was set at 0.05 h−1, and this value was maintained throughout the experiments described below.

Each growth mode was maintained for at least 7 days. At the onset of sampling the chemostat was at a steady state, as indicated by stable cell counts. Samples from the steady-state fermentor were taken daily for 4 to 5 days.

The sequence of experimental setups was as follows: (i) anaerobic growth in the presence of 8 mM sulfate and gassing with nitrogen maintained for 8 days; (ii) microaerobic growth in the presence of 8 mM sulfate with an oxygen flux of 223 μmol min−1 maintained for 7 days; and (iii) microaerobic sulfate-depleted growth maintained for 10 days. During the last stage the incoming medium contained no sulfate, and the sulfate concentration in the steady-state fermentor decreased exponentially from 100 μM on the third day of this mode to 2.5 μM on the seventh day.

Enumeration of D. oxyclinae and Marinobacter sp. strain MB in the coculture.

The total cell numbers in each sample were determined by microscopic counting of at least 500 cells in Petroff-Hausser chamber. The number of viable sulfate-reducing cells was determined by the most-probable-number (MPN) method by using eight replicate fivefold dilutions on Nunclon (Roskilde, Denmark) 96-well plates. Defined multipurpose medium with an ascorbate-thioglycolate reducing solution (28) supplemented with 50 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O per liter was used. The multiwell plates were incubated in an anaerobic hood.

For direct microscopic determination of the proportion of D. oxyclinae cells, in situ hybridization was used. The cells were harvested by centrifugation, fixed for 12 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, and treated as described by Manz et al. (19). The resulting slides were then hybridized with rhodamine-labeled probe DSV 698 (19). Prior to mounting, the slides were stained for 10 min with 1 μg of DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) per ml. Microscopic examination was performed with a Zeiss Axiovert 135 epifluorescent microscope equipped with filter set 26 (excitation at 575 to 625 nm, 645-nm blocking filter, emission at 660 to 710 nm) for counting the rhodamine-stained cells of D. oxyclinae and with filter set 02 (excitation at 365 nm, 395-nm blocking filter, emission at 420 nm) for counting the total number of DAPI-stained cells. At least 500 cells were counted for each sample.

Sulfate reduction in the coculture.

The rates of sulfide production were determined by using a reaction chamber with built-in electrodes for oxygen, sulfide, and pH, which allowed concomitant measurement of the rates of aerobic respiration, sulfide production, and sulfide consumption (7). Prior to measurement, the samples were aseptically washed with sterile medium without carbon and sulfur sources. The resulting thick cell suspension was incubated under nitrogen for 30 min. Protein concentrations were determined after the measurements.

Analytical procedures.

Protein determination was performed by the Lowry method (18). Elemental sulfur, which interferes with this reaction, was not found in the samples. Sulfate was determined by the turbidimetric method (1), as modified by H. Cypionka (personal communication). Sulfide was determined colorimetrically (4). Organic acids were determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (26).

RESULTS

The growth parameters of the coculture were examined under three growth modes: anaerobic in the presence of sulfate, microaerobic in the presence of sulfate, and microaerobic under sulfate depletion. The results are presented in Table 1 and Fig. 1. Each value is an average based on the values for four or five samples.

TABLE 1.

Growth parameters of the D. oxyclinae-Marinobacter sp. strain MB coculture in the presence and absence of sulfate

| Concn of SO4 supplied (mM) | % of O2 in gas | Residual concn (mM) in culture liquid

|

Protein concn (mg liter−1) | Amt of protein per cell (pg) | Total no. of cells (108 cells ml−1) |

D. oxyclinae

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulfate | Acetate | Citrate | Lactate | MPN (108 cells ml−1) | % | |||||

| 8 | 0 | 0 | 15.6 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.3 | 46.9 ± 2.4 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.8 (0.6–3.1)a | 86 |

| 8 | 5 | 3.6 ± 1.1 | 14.3 ± 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 134.3 ± 12.3 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 6.5 ± 0.5 | 0.8 ± 0.6 (0.4–1.4) | 69.5 |

| 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 135.7 ± 8.5 | 0.17 ± 0.06 | 8.4 ± 2.1 | 0.6 ± 0.2 (0.4–1.5) | 34.4 |

The values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals.

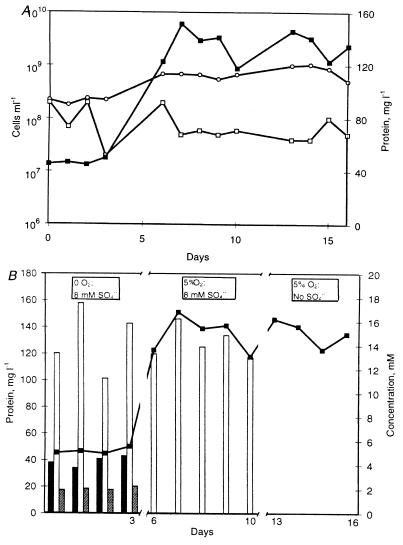

FIG. 1.

(a) Microscopic cell counts (○), MPN counts of D. oxyclinae (□), and protein concentrations (■) in the coculture. (b) Concentrations of lactate (solid bars), acetate (open bars), citrate (cross-hatched bars), and protein (■) in the coculture.

During the anaerobic, sulfate-reducing stage the chemostat was designed to be sulfate limited. Indeed, all of the 8 mM sulfate was consumed. Of the 19 mM lactate added to the medium, 4.4 ± 0.3 mM residual lactate was found; 15.6 ± 0.8 mM lactate was oxidized to acetate. The 3.7 mM citrate included in the medium as part of a phosphate-citrate buffer was not consumed during this growth mode. D. oxyclinae accounted for the majority of the cells in the coculture. The relative abundance of D. oxyclinae determined by in situ hybridization was 86%, and this value was in agreement with independent cell counts obtained by using differential inhibition of cell division by nalidixic acid (15, 23a). The cell numbers, protein content, and composition of the coculture were similar to those previously reported for this coculture under anaerobic conditions (23b) (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

When the chemostat was switched to the microaerobic, sulfate-reducing mode by gassing with 5% O2, a drop in sulfate reduction was observed. Only 55% of the sulfate was consumed. All oxygen introduced into the growth vessel was consumed, and no dissolved oxygen was detected in the fermentor. Both lactate and citrate were consumed completely. The concentration of acetate was similar to that observed during the anaerobic growth mode. The total cell numbers and protein concentration increased significantly, by 2.9-fold. The average protein content per cell did not change compared to the content in the anaerobic mode. D. oxyclinae accounted for 69.5% of the total cells, compared to 86% in the anaerobic mode (Fig. 1 and Table 1). The proportion of D. oxyclinae cells found under the same oxygen flux conditions in coculture experiments by means of differential inhibition by nalidixic acid was 64% (23a).

At the onset of the next stage, sulfate was excluded from the incoming medium. All other growth conditions did not change. During the steady state of the sulfate-depleted mode the sulfate levels were 3 ± 1 μM. These sulfate concentrations did not support dissimilatory sulfate reduction. D. oxyclinae was previously found to be unable to reduce sulfate at these concentrations even under anaerobic conditions (16). Nevertheless, the need for an assimilatory sulfur source was met. As in the previous growth mode, all oxygen was consumed and dissolved oxygen was not detected in the fermentor. During this sulfate-depleted microaerobic mode all lactate, citrate, and acetate were consumed, and no organic acids were found in the medium (Fig. 1B). This indicates that complete oxidation to CO2 occurred. Compared to the data obtained during the previous stage, the total cell numbers increased slightly, while the protein concentration did not change. Hence, the calculated protein content per cell decreased somewhat. The MPN counts of D. oxyclinae were half those found in the anaerobic mode and similar to those observed during the microaerobic, sulfate-reducing growth mode (Fig. 1A). If no growth of D. oxyclinae occurred under sulfate depletion conditions, the viable cell numbers would have decreased exponentially due to washout from 5.8 × 107 to 9 × 103 cells ml−1 in the last sample taken after 6 days of sulfate depletion. D. oxyclinae continued to grow at a rate of 0.05 h−1, though the growth yield was somewhat lower. The proportion of D. oxyclinae cells in the coculture was 34.4% ± 1.9% and did not change throughout the experiment.

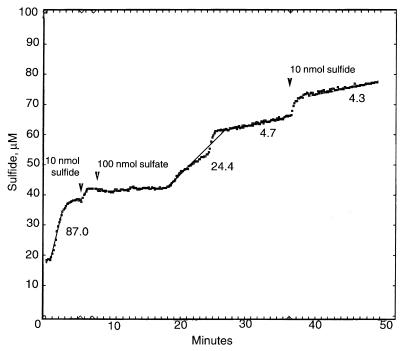

Reduction of sulfur compounds by the coculture retrieved from the sulfate-free chemostat on the fifth day of this growth mode was observed in the respiration chamber after addition of an excess amount of lactate, followed by addition of thiosulfate and sulfate (Fig. 2). Since the proportion of D. oxyclinae cells in the coculture was known, it was possible to calculate the rates of sulfate and thiosulfate reduction per milligram of D. oxyclinae protein, assuming that the protein content per cell was the same for both organisms. The rate of thiosulfate reduction was 79.7 nmol mg−1 min−1, while the rate of sulfate reduction, 24.5 nmol mg−1 min−1, was substantially lower. All of the sulfate introduced was accounted for as sulfide, yet only 1 mol of sulfide was produced per mol of thiosulfate introduced. These rates were substantially lower than the rates observed in pure anaerobic cultures of D. oxyclinae for both sulfate reduction and thiosulfate reduction (180 to 200 nmol mg−1 min−1) (16). The capacity for both thiosulfate and sulfate reduction was inhibited but not lost after prolonged growth under sulfate-depleted conditions.

FIG. 2.

Sulfide production by the cells of the coculture on the fifth day of the microaerobic, sulfate-depleted mode, as observed in the respiration chamber. The sample was washed and incubated in oxygen-free mineral medium supplemented with 1,000 nmol of lactate. Before measurement, the sample was incubated for 20 min with 100 nmol of thiosulfate. The arrowheads indicate the times of addition of 100 nmol of sulfate and two calibration pulses (10 nmol of sulfide each). The numbers below the line indicate the rates of sulfide production (in nanomoles per milligram of D. oxyclinae protein per minute).

DISCUSSION

In order to understand the metabolic activities of the different organisms constituting a coculture, a method for determining their relative levels is essential. The two approaches used in the study of cocultures of D. oxyclinae and Marinobacter sp. strain MB were differential inhibition by nalidixic acid (23a) and in situ hybridization. The results obtained with these methods were found to be in good agreement with each other. Only in situ hybridization data are presented in this paper.

Since D. oxyclinae is a marine organism, it has a low affinity for sulfate, with a KS for sulfate of 0.8 mM. The affinity of this organism for thiosulfate is considerably higher (KS, 10 μM). Hence, thiosulfate may be an important electron acceptor under natural sulfate limitation conditions. Experiments with axenic chemostat cultures of D. oxyclinae revealed the possibility that incomplete sulfide oxidation is coupled to thiosulfate reduction when the cultures are exposed to oxygen (23b), yet D. oxyclinae was found to persist throughout the microaerobic, sulfate-depleted stage of the experiment when sulfate concentrations were 3 ± 1 μM and thiosulfate was not detected.

Growth of D. oxyclinae under microaerobic, sulfate-depleted conditions was maintained by sulfate- and thiosulfate-independent processes. Since D. oxyclinae was found to be able to grow slowly by fermenting pyruvate but not lactate (16), this growth could not be caused by fermentation. Neither D. oxyclinae nor Marinobacter sp. strain MB was found to be capable of using ferric iron as the sole electron acceptor (data not shown). Likewise, D. oxyclinae does not grow anaerobically on media containing thioglycollate as the only sulfur species. Oxygen was therefore the only electron acceptor available to D. oxyclinae under these conditions, and aerobic respiration was the only possible mechanism for persistent growth of D. oxyclinae in this steady-state continuous culture.

The rate of oxygen supply did not change from the microaerobic, sulfate-reducing stage to the microaerobic, sulfate-depleted stage. In the last growth mode all of the organic carbon sources were completely oxidized, presumably by Marinobacter sp. strain MB since D. oxyclinae cannot metabolize either acetate or citrate (16). Although during this stage oxygen was completely consumed, this apparently did not limit the process. Given the persistence of D. oxyclinae in the continuous culture, the oxygen consumption by the coculture was expected to be higher than that by the axenic aerobic culture of Marinobacter sp. strain MB. Indeed, in pure batch cultures of Marinobacter sp. strain MB supplemented with the nutrients at the concentrations found in the chemostat and aerated with the same gas mixture, residual dissolved oxygen was always present at concentrations up to 35 μM (data not shown).

Like all desulfovibrios, D. oxyclinae is capable of oxidizing lactate only incompletely, to acetate. The possible pathways for acetate production in this system were (i) lactate fermentation by Marinobacter sp. strain MB; (ii) incomplete anaerobic oxidation of lactate by D. oxyclinae coupled to sulfate reduction; (iii) incomplete aerobic oxidation of lactate by Marinobacter sp. strain MB; and (iv) incomplete aerobic oxidation of lactate by D. oxyclinae. Marinobacter sp. strain MB in cocultures with D. oxyclinae performed incomplete lactate oxidation only in the presence of lower oxygen fluxes (23a). D. oxyclinae was therefore responsible for all of the 14.3 mM acetate found in the coculture during the microaerobic, sulfate-reducing stage. Considering the amount of sulfate consumed, only 8.8 mM acetate could have been produced via sulfate reduction.

Although sulfate-depleted conditions do not occur in the natural habitat of D. oxyclinae, the ability to grow aerobically may still be beneficial. The sulfate reduction rate in cocultures of D. oxyclinae with Marinobacter sp. strain MB was previously shown to be impaired by increasing the oxygen flux (23a). It is therefore possible that in the upper layers of cyanobacterial mats during daytime D. oxyclinae grows aerobically.

Aerobic growth was not observed in axenic cultures of D. oxyclinae. The cells of Marinobacter sp. strain MB decreased the concentration of dissolved oxygen in cocultures. This organism is well adapted to aerobic environments and could possibly ameliorate their toxic effects on D. oxyclinae. While D. oxyclinae is catalase positive and can therefore detoxify peroxides (16), superoxide dismutase activity has not previously been reported in this organism, although it was found in Desulfovibrio gigas (10). While superoxide dismutase is not the only enzyme that allows anaerobic bacteria to detoxify superoxides, superoxide reductase has been found only in thermophilic archaea (13). Characterization of superoxide dismutases in D. oxyclinae and in defined cocultures of D. oxyclinae and Marinobacter sp. strain MB is now being investigated.

This is the first report of a sulfate-reducing bacterium growing in the absence of sulfate and thiosulfate and in the presence of oxygen. D. oxyclinae is seemingly a facultatively sulfate-reducing bacterium capable of aerobic respiration by incomplete oxidation of lactate to acetate. This metabolic reaction may occur even in the presence of sulfate, as implied by the growth of this organism when sulfate reduction activity is impaired by oxygen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was financially sponsored by grant I-252-131.09 from the German-Israel Science Foundation (GIF), by grant 03F0151A from the Red Sea Program for Marine Sciences of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), and by grant Ru 458/18 from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn, Germany.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Public Health Association. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biebl H, Pfennig N. Isolation of members of the family Rhodospirillaceae. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1981. pp. 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canfield D E, Des Marais D J. Aerobic sulfate reduction in microbial mats. Science. 1991;251:1471–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.11538266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cline J D. Spectrophotometric determination of hydrogen sulfide in natural waters. Limnol Oceanogr. 1969;14:454–458. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cohen Y. Oxygenic photosynthesis, anoxygenic photosynthesis, and sulfate reduction in cyanobacterial mats. In: Klug M G, Reddy C A, editors. Current perspectives in microbial ecology. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1984. pp. 435–441. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen Y, Helman Y, Sigalevich P. Light-driven sulfate reduction and methane emission in hypersaline cyanobacterial mats. NATO Adv Study Inst Ser G. 1994;35:421–427. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cypionka H. Sulfate transport. Methods Enzymol. 1994;243:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dannenberg S, Kroder M, Dilling M, Cypionka H. Oxidation of H2, organic compounds and inorganic sulfur compounds coupled to reduction of O2 or nitrate by sulfate-reducing bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 1992;158:93–99. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dilling W, Cypionka H. Aerobic respiration in sulfate-reducing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1990;71:123–128. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dos Santos W G, Pacheco I, Liu M-Y, Teixeira M, Xavier A V, LeGall J. Purification and characterization of an iron superoxide dismutase and a catalase from the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio gigas. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:796–804. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.3.796-804.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fründ C, Cohen Y. Diurnal cycles of sulfate reduction under oxic conditions in cyanobacterial mats. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:70–77. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.1.70-77.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gauthier M J, Lafay B, Christen R, Fernandez L, Acquaviva M, Bonin P, Bertrand J-C. Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus gen. nov., sp. nov., a new, extremely halotolerant, hydrocarbon-degrading marine bacterium. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:568–576. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-4-568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jenny F E, Jr, Verhagen M F J M, Cui X, Adams M W W. Anaerobic microbes: oxygen detoxification without superoxide dismutase. Science. 1999;286:306–309. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5438.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson M S, Zhulin I B, Gapuzan E R, Taylor B L. Oxygen-dependent growth of the obligate anaerobe Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:5598–5601. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.17.5598-5601.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kogure K, Simudu U, Taga N. A tentative direct microscopical method for counting living marine bacteria. Can J Microbiol. 1979;25:415–420. doi: 10.1139/m79-063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krekeler D, Sigalevich P, Teske A, Cypionka H, Cohen Y. A sulfate-reducing bacterium from the oxic layer of a microbial mat from Solar Lake (Sinai), Desulfovibrio oxyclinae sp. nov. Arch Microbiol. 1997;167:369–375. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krekeler D, Teske A, Cypionka H. Strategies of sulfate-reducing bacteria to escape oxygen stress in a cyanobacterial mat. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:89–96. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manz W, Eisenbrecher M, Neu T R, Szewzyk U. Abundance and spatial organization of Gram-negative sulfate-reducing bacteria in activated sludge investigated by in situ probing with specific 16S rRNA targeted oligonucleotides. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 1998;25:43–61. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minz D, Fishban S, Green S J, Muyzer G, Cohen Y, Rittmann B E, Stahl D A. Unexpected population distribution in a microbial mat community: sulfate-reducing bacteria localized to the highly oxic chemocline in contrast to a eukaryotic preference for anoxia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4659–4665. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4659-4665.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Minz D, Flax J L, Green S J, Muyzer G, Cohen Y, Wagner M, Rittmann B E, Stahl D A. Diversity of sulfate-reducing bacteria in oxic and anoxic regions of a microbial mat characterized by comparative analysis of dissimilatory sulfite reductase genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4666–4671. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4666-4671.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Postgate J R. The sulfate-reducing bacteria. 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Revsbech N P, Jorgensen B B, Blackburn T H, Cohen Y. Microelectrode studies of the photosynthesis and O2, H2S and pH profiles of a microbial mat. Limnol Oceanogr. 1983;28:1062–1074. [Google Scholar]

- 23a.Sigalevich P, Baev M V, Teske A, Cohen Y. Sulfate reduction and possible aerobic metabolism of the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio oxyclinae in a chemostat coculture with Marinobacter sp. strain MB under exposure to increasing oxygen concentrations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5013–5018. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.11.5013-5018.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23b.Sigalevich P, Meshorer E, Helman Y, Cohen Y. Transition from anaerobic to aerobic growth conditions for the sulfate-reducing bacterium Desulfovibrio oxyclinae results in flocculation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:5005–5012. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.11.5005-5012.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teske A, Sigalevich P, Cohen Y, Muyzer G. Molecular identification of bacteria from a coculture by denaturating gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S ribosomal DNA fragments as a tool for isolation in pure cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4210–4215. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4210-4215.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teske A, Ramsing N B, Habicht K, Fukui M, Küver J, Jørgensen J, B B, Cohen Y. Sulfate-reducing bacteria and their activities in cyanobacterial mats of Solar Lake (Sinai, Egypt) Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:2943–2951. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.8.2943-2951.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tusseau D, Benoit C. Routine high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of carboxylic acids in wines and champagne. J Chromatogr. 1987;395:323–333. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)94121-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Widdel F, Hansen T A. The dissimilatory sulfate- and sulfur-reducing bacteria. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 583–624. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Widdel F. The genus Desulfotomaculum. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1991. pp. 1792–1799. [Google Scholar]