Abstract

Mycorrhizal ascomycetous fungi are obligate ectosymbionts that colonize the roots of gymnosperms and angiosperms. In this paper we describe a straightforward approach in which a combination of morphological and molecular methods was used to survey the presence of potentially endo- and epiphytic bacteria associated with the ascomycetous ectomycorrhizal fungus Tuber borchii Vittad. Universal eubacterial primers specific for the 5′ and 3′ ends of the 16S rRNA gene (16S rDNA) were used for PCR amplification, direct sequencing, and phylogenetic analyses. The 16S rDNA was amplified directly from four pure cultures of T. borchii Vittad. mycelium. A nearly full-length sequence of the gene coding for the prokaryotic small-subunit rRNA was obtained from each T. borchii mycelium studied. The 16S rDNA sequences were almost identical (98 to 99% similarity), and phylogenetic analysis placed them in a single unique rRNA branch belonging to the Cytophaga-Flexibacter-Bacteroides (CFB) phylogroup which had not been described previously. In situ detection of the CFB bacterium in the hyphal tissue of the fungus T. borchii was carried out by using 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for the eubacterial domain and the Cytophaga-Flexibacter phylum, as well as a probe specifically designed for the detection of this mycelium-associated bacterium. Fluorescent in situ hybridization showed that all three of the probes used bound to the mycelium tissue. This study provides the first direct visual evidence of a not-yet-cultured CFB bacterium associated with a mycorrhizal fungus of the genus Tuber.

The mycorrhizal ascomycetous fungi belonging to the genus Tuber, commonly called truffles, are obligate ectosymbionts that colonize the roots of gymnosperms and angiosperms (23, 39, 45). Ectomycorrhizal fungi are present in natural and agricultural ecosystems, provide health benefits to plants, and contribute to soil nutrient cycling. The symbiotic development of mycorrhizal fungi on plant roots has been reported to be influenced by bacteria present in the mycorrhizosphere (10, 16, 35, 47). Although various bacterial populations, such as fluorescent Pseudomonas strains and the spore-forming bacteria Micrococcus spp., Moraxella spp., Corynebacterium spp., and Staphylococcus spp., have been isolated from truffles (3, 14, 20), no molecular evidence has been found concerning the relationship between these organisms and their specific locations in the Tuber host tissue. There is also no information concerning the endo- and epiphytic bacteria which throughout life or during part of the life cycle may invade the tissues of the living fungus and cause unapparent and asymptomatic infections throughout the fungal life cycle and thus during production of the mycelium, contact with the host root, and development of the ectomycorrhizae and fruit bodies.

Since at least 95% of all soil bacteria have not been cultured (2, 25, 36), bacteria isolated from truffles could represent only a fraction of the entire natural bacterial community associated with truffles. For this reason in this study we attempted to use a combination of morphological and molecular 16S rRNA-based approaches to survey the presence of potential bacterial endo- and epiphytes associated with the ectomycorrhizal fungus Tuber borchii Vittad. These tools have been used previously to identify endophytic bacteria such as the Burkholderia endosymbiont of Gigaspora margarita (7) and members of the alpha and beta subclasses of the Proteobacteria detected as epibionts in ectomycorrhizae of Fagus sylvatica, Lactarius vellereus, and Lactarius subdulcis (33).

In order to achieve our goal, we used a model for in vitro ectomycorrhizal synthesis developed recently for biotechnological applications (43).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Biological materials: mycelia, mycorrhizal roots, and bacteria.

Four different mycelia (1BO [= ATCC 96540], 10RA, 17BO, and Z43) were isolated from fresh T. borchii fruit bodies collected in natural truffle grounds in central Italy. Dried samples of each specimen are preserved in the herbarium of the Mycology Center of Bologna (Bologna, Italy). The isolates were grown in the dark at 24°C with no agitation in modified Melin-Norkrans nutrient solution (MMN) (pH 6.6) by using the method of Molina (34). Each 100-ml flask contained 70 ml of medium inoculated with fungus cultured in potato dextrose agar plugs, as described by Saltarelli et al. (41). Ectomycorrhizae of T. borchii were obtained aseptically in vitro in a peat-vermiculite nutrient mixture from infection of Tilia platyphyllos Scop. with mycelium strains 1BO, 10RA, 17BO, and Z43 (43). Pseudomonas fluorescens B20 and Bacillus subtilis C15 were isolated on tryptic soy agar (Oxoid) from a T. borchii fruit body collected in central Italy (20).

Morphological observations.

Extreme care was taken to avoid bacterial contamination: all solutions used in this study were filter sterilized, and sterile procedures were used during fixing and/or crushing. Microscopic observations were carried out with each culture of T. borchii mycelium and with the medium used. The mycelium strains were grown in parallel in potato dextrose agar plates on which sterile cover slides were placed. The hyphae growing on the cover slides were directly stained with 4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (0.01 μg/ml). Samples were viewed with a Zeiss Axioskope microscope (Carl Zeiss, Milan, Italy) with contrast phase and epifluorescence and equipped with UV, rhodamine, or fluorescein excitation filter sets.

DNA extraction.

Mycelial genomic DNA was extracted from 1-month-old cultures of T. borchii 1BO, 10RA, 17BO, and Z43 by using the protocol described by Erland et al. (17). Ectomycorrhizal and plant DNA were extracted by using the method of Henrion et al. (24). Bacterial DNA was extracted directly from colonies by using the standard phenol DNA extraction method (42). In order to eliminate the possible presence of contaminants from our templates, DNA from a different clone of the same mycelium strain, 1BO (= ATCC 96540), was extracted in the laboratory of P. Bonfante, University of Turin, Turin, Italy. Furthermore, to confirm the presence of the bacterium in other T. borchii mycelium strains, DNA was extracted from strain B2 (at the University of Urbino, Urbino, Italy), as well as strains A1 and A2 (at Centre INRA, Clermont Ferrand, France), and DNA from a strain of Neurospora crassa was used as a negative control.

PCR conditions.

Before starting our study, we confirmed that the mycelium strains belonged to the species T. borchii Vittad. by using PCR strategies developed in previous work on species-specific identification (5, 6). Once the mycelia were identified as T. borchii, amplification of the 16S rRNA gene (rDNA) of bacteria potentially associated with the ectomycorrhizal fungus was performed in 25-μl (final volume) mixtures by using 100- to 200-ng portions of genomic DNA from mycelia, ectomycorrhizae, nonmycorrhizal roots, and bacteria. Universal eubacterial primers (UP-Forward and UP-Reverse) were used to amplify the 16S rDNA from all samples (Table 1). A specific primer was designed based on the sequence data obtained from mycelium strain 17BO (b-17BO-f [Table 1]). The specificity of primer b-17BO-f was checked with the Ribosomal Database Project (RDP) (31) sequence database, and no matches with other available sequences were found. Primer b-17BO-f was used in combination with UP-Reverse to specifically detect the endophytic bacterium in other T. borchii mycelium strains and in other samples. The PCR conditions were as follows: 30 cycles consisting of denaturation at 94°C for 45 s, annealing at 53°C for 45 s, and elongation at 72°C for 2 min. Amplified products were purified with a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen GmbH, Hilden, Germany) and then digested with TaqI, AluI, and MspI enzymes for restriction fragment length polymorphism analyses. Representative PCR products with identical restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns were chosen for direct sequencing with an ABI Prism cycle sequencing kit (dRhodamine terminator cycle sequencing kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS; Perkin-Elmer).

TABLE 1.

Primers and probes used in the present study

| Primer or probe | Type | Sequence (5′-3′) | Positiona | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primers | ||||

| b-17BO-f | AAC CCT TTC ACG TGT G | 451–465 | This study | |

| UP-Forward | Eubacteria | AGA GTT TGAT YM TGG C | 8–24 | 48 |

| UP-Reverse | Eubacteria | GYT ACC TTG TTA CGA CTT | 1493–1513 | 48 |

| Probes | ||||

| CF319 | Cytophaga-Flexibacter cluster | TGG TCC GTG TCT CAG TAC | 319–336 | 32 |

| EUB338 | Eubacteria | GCT GCC TCC CGT AGG AGT | 338–355 | 1 |

| STBb-654 | GCC CAC ATC ATC TGT ACT | 654–672 | This study |

E. coli numbering (9).

Phylogenetic analysis.

The Check_Chimera program of the RDP was used to search for chimeric sequences. Closely related or phylogenetically relevant sequences were obtained from the RDP database and the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases. Sequences were aligned on the basis of secondary structure by using the RDP data and the sequence alignment editor with SeqPup, version 0.5 (22). Sequences from the RDP database served as the alignment guidelines. Corrected pairwise distances were computed by using the Jukes-Cantor correction (26). A distance matrix was inferred with the DNADIST program, and phylogenetic trees were constructed from the evolutionary distance matrix by using FITCH and from the alignment by using the DNAPAR program for parsimony analysis and DNAML for maximum-likelihood analysis, as implemented in the PHYLIP software package, version 3.5c (18). Bootstrap analyses were based on 200 resamplings of the sequence alignment and were performed with DNABOOT as implemented in PHYLIP, version 3.5c. The TreeView program was used to plot the tree files (37).

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH): oligonucleotide probes.

The 16S rRNA sequence was added to the VERMICON 16S rRNA database containing about 12,000 16S rRNA sequences by using the ARB program package (http: //www.biol.chemie.tu-muenchen.de/pub/ARB/). The ARB_EDIT tool was used for sequence alignment. Probe design was computed by using the appropriate tool in the ARB software package. The nucleotide sequence of the 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probe STBb-654, which is specific for the Cytophaga-Flexibacter-Bacteroides phylogroup (CFB) bacterium described here, is shown in Table 1. This probe was labeled at the 5′ end with Cy3 (MWG Biotech AG, Ebersberg, Germany). Probes specific for the Cytophaga-Flexibacter group (CF319) (32), labeled at the 5′ end with fluorescein, and for the bacterial domain (EUB338) (1), labeled at the 5′ end with fluorescein, were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Cologno Monzese MI, Italy. The probe specifically designed for detecting the CFB bacterium and probe CF319 were used with hyphal tissue homogenates fixed in ethanol and paraformaldehyde (2). All the probes were used with DAPI and/or the EUB338 probe.

In situ hybridization.

Mycelia growing in MMN liquid medium were fixed in formaldehyde–70% ethanol–acetic acid (5:90:5), dehydrated in a graded aqueous ethanol series (70, 80, 95, and 100% ethanol), clarified in xylol, embedded in paraffin wax (56 to 58°C), and cut with a rotary microtome (Top Rotary M, S132 Pablish) (thickness, 8 to 10 μm). The sections were mounted on glass slides, and the paraffin was removed by immersion in xylene for 15 min. Thin sections used for in situ hybridization with fluorescent probes were rehydrated with a graded ethanol series by 5-min incubations in 98%, 80%, and 60% ethanol. The same specimens were homogenized by using a sterile glass pestle and 500 μl of sterile MMN liquid medium, washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline, and fixed in ethanol and paraformaldehyde as described by Amann et al. (2); this was followed by DAPI staining. Homogenized samples consisted of hyphal fragments ranging from 7.3 to 33 μm long. Fixed samples of hyphal tissue homogenate were immobilized on glass slides by air drying and were dehydrated in 60, 80, and 98% (vol/vol) ethanol (3 min each). In situ hybridizations were performed as previously described by Amann et al. (2). The optimal hybridization stringency for probe STBb-654 was obtained by adding formamide to a final concentration of 35%. For combinations of probes with different optimal hybridization stringencies, two hybridizations were done successively; hybridization with the probe which required the higher formamide concentration (EUB338) was performed first, and this was followed by a second hybridization at the lower stringency with the other specific probes (STBb-654 or CF319). Each hybridization set included an unstained sample used as a control for autofluorescence.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The 16S rDNA sequences of T. borchii mycelium bacterial endophytes b-17BO, b-Z43, b-10RA, and b-1BO have been deposited in the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases under accession numbers AF070444, AF233292, AF233293, and AF233294, respectively.

RESULTS

Morphological observations.

DAPI staining revealed several cytoplasmic structures, as well as nuclei, in the 15-day-old cultures of T. borchii mycelia analyzed (1BO [= ATCC 96540], 10RA, 17BO, and Z43). Although several cytoplasmic rounded organelle-like structures and ca. two nuclei for each septum were fluorescent, no external bacteria or bacterium-like organelles were observed.

PCR assays.

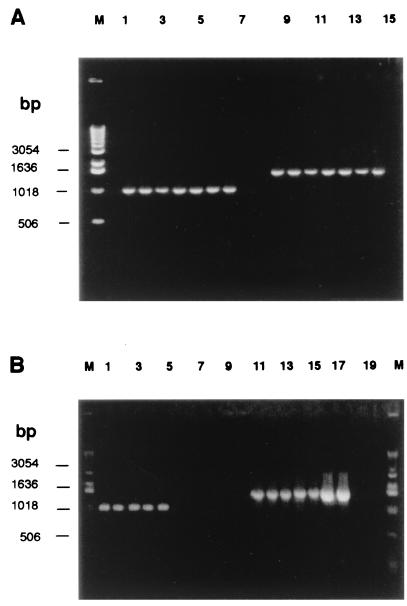

Molecular data obtained by PCR, as well as FISH, provided consistent proof of a bacterial presence in the ectomycorrhizal mycelium of T. borchii Vittad. High-molecular-weight DNA was extracted from the T. borchii Vittad. mycelium strains, and 16S rDNAs were amplified with eubacterium-specific PCR primers. The resulting products were estimated to be approximately 1,500 bp (Fig. 1A). Negative controls with no template consistently gave no amplification products (Fig. 1). Consensus sequence data encompassing 1,457 bp were obtained from the individual strains and were submitted to the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases as b-17BO, b-1BO, b-10RA, and b-Z43. These sequences differed on average by about 1%.

FIG. 1.

PCR experiments. PCR assays were performed to check for the presence of the CFB bacterium in T. borchii Vittad. ectomycorrhizal mycelium. (A) Agarose (1%) gel electrophoresis of PCR products amplified with the b-17BO-f and UP-Reverse primers (lanes 1 to 8) or eubacterial primers UP-Forward and UP-Reverse (lanes 9 to 15). The templates used were T. borchii mycelium strains 1BO (= ATCC 96540) (lanes 1 and 9), 17BO (lanes 2 and 10), 10RA (lanes 3 and 11), Z43 (lanes 4 and 12), B2 (lanes 5 and 13), and A1 (lanes 6 and 14) and 1BO template extracted in the laboratory of P. Bonfante, University of Turin (lanes 7 and 15); no DNA was included in lanes 8 and 16. Lane M contained a fragment size marker (1-kb DNA ladder; GIBCO/BRL). (B) Agarose (1%) gel electrophoresis of PCR products amplified with the b-17BO-f and UP-Reverse primers (lanes 1 to 10) or eubacterial primers UP-Forward and UP-Reverse (lanes 11 to 20). The control templates used were ectomycorrhizae of T. borchii on T. platyphyllos, including ectomycorrhizae of 1BO (lanes 1 and 11), 17BO (lanes 2 and 12), 10RA (lanes 3 and 13), and Z43 (lanes 4 and 14). Mycelium strain 1BO was used as a positive control (lanes 5 and 15). Bacterial strains, including P. fluorescens C5 (lanes 6 and 16) and B. subtilis C15 (lanes 7 and 17), N. crassa (lanes 8 and 18), mycelial growth medium (lanes 9 and 19), and no DNA (lanes 10 and 20) were also used. Lanes M contained a fragment size marker (1-kb DNA ladder; GIBCO/BRL).

A specific primer (b-17BO-f) was designed based on the variable region (positions 451 to 465) of the b-17BO 16S rDNA sequence, in order to check for the occurrence of this bacterium in vitro by using the model recently developed for ectomycorrhizal synthesis of T. borchii mycelium and micropropagated T. platyphyllos Scop. plantlets. This model was developed under controlled sterile conditions (43), in which exposure to bacterial infection or contamination was avoided and influence of other biotic and abiotic factors on the interactions between the fungus and the host was ruled out. Primer b-17BO-f was used in combination with the universal reverse primer in PCR assays performed with T. borchii mycelia and roots of T. platyphyllos Scop. infected with T. borchii. To assess primer specificity and to rule out the possibility that the amplified and sequenced DNA fragments were derived from contaminants, controls were tested with both universal and specific primer sets. Primer b-17BO-f gave a product of the expected length (1,043 bp) for all T. borchii mycelia tested and for roots infected with T. borchii (Fig. 1A). No amplification was obtained from nonmycorrhizal T. platyphyllos roots, N. crassa, P. fluorescens, B. subtilis, and the medium used for mycelium growth. PCR products of the expected length were obtained from the controls when the eubacterial primers were used. T. platyphyllos roots, N. crassa, and the medium gave no amplification products (Fig. 1B). The 1,043-bp band obtained from the four mycelial ectomycorrhizae and the other mycelial strains of T. borchii used as controls (B2, A1, and 1BO) was digested with the TaqI, AluI, and MspI restriction enzymes. Each enzyme provided the same patterns for mycelia and ectomycorrhiza samples (data not shown), suggesting high sequence similarity. This hypothesis was confirmed by the nearly identical sequences obtained (ca. 1% difference).

All of the sequences obtained were of bacterial origin due to the specificity of the UP-Forward primer; however, a search was performed by using the RDP mitochondrial database. This screening analysis revealed a range of similarity values between 13.5 and 14% for 1,281 nucleotides aligned with the mitochondrial rRNA gene sequences of some Aspergillus species (27). A pairwise comparison between the b-17BO sequence and a small-subunit mitochondrial sequence from a fruit body of T. borchii (44) revealed only about 15% similarity. This result ruled out the possibility of mycelial small-subunit mitochondrial gene amplification.

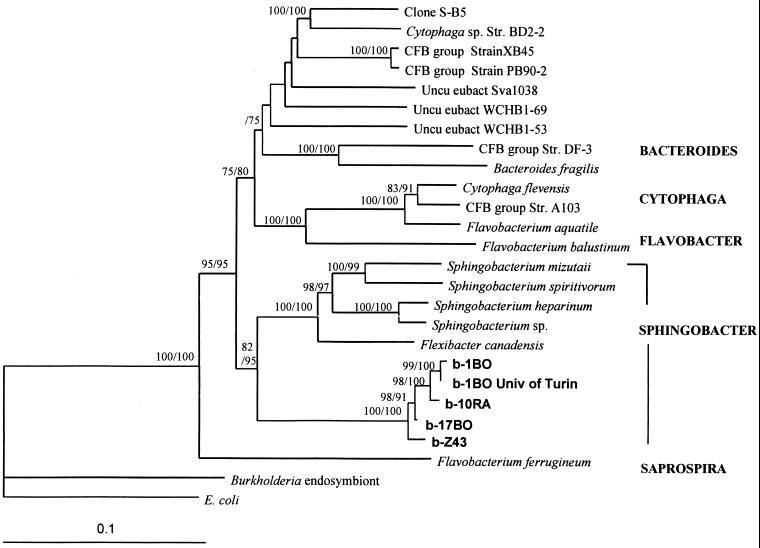

Phylogenetic analysis.

In order to describe the relationship between the presumptive bacterial endo- or epiphyte and previously recognized bacterial taxa, extensive phylogenetic analyses using distance matrix, parsimony, and maximum-likelihood criteria were performed with nearly full-length sequences (length, approximately 1,500 bp). Table 2 shows the 16S rRNA sequences used in the present study. Table 3 shows the evolutionary distances derived from nearly full-length 16S rRNA gene sequences found in different strains of T. borchii mycelia (b-17BO, b-1BO, b-Z43, b-10RA, and b-1BO University of Turin) and closely related eubacterial sequences obtained from the RDP and the DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases (8, 13, 15, 29, 46, 49; C. D. Phelps, L. Kerkhof, and L. Y. Young, DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank databases). Relevant sequences considered representative of the five most well-defined subgroups in the CFB phylum as suggested by Gherna and Woese (21) were also included, as were the 16S rDNAs of a Burkholderia strain (a bacterial endosymbiont of the endomycorrhizal fungus G. margarita, for comparison) and Escherichia coli, which served as an outgroup. Most of the sequences with high levels of similarity (>90%), as determined by the RDP sequence match program, either were partial sequences not useful for phylogenetic analyses (28) or were described as sequences of uncultivated soil bacteria which may not have been identified (19, 30). However, all methods of phylogenetic reconstruction, based on the sequences selected, unambiguously placed the mycelial bacterial sequences in a single new rRNA branch among the Sphingobacter subgroup of the CFB phylum defined by Gherna and Woese (21). The stability of this new branch was verified by bootstrap analysis, and a confidence level of 100% was obtained with all methods. A phylogenetic tree relating the five most well-defined subgroups in the CFB phylum derived from the evolutionary distances in Table 2 is shown in Fig. 2. Trees showing the same affiliation for the T. borchii CFB organism were obtained after complete exclusion or inclusion of both insertions and deletions and/or variable regions.

TABLE 2.

Eubacterial 16S rDNA sequences from T. borchii Vittad. ectomycorrhizal fungi (mycelium strains 1BO, 17BO, 10RA, and Z43) and their close relatives

| Taxon | Accession no. | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| b-17BO | AF070444 | This study |

| b-10RA | AF233293 | This study |

| b-1BO | AF233294 | This study |

| b-1BO University of Turin | This study | |

| b-Z43 | AF233292 | This study |

| Bacteroides fragilis | M11656 | 49 |

| Burkholderia endosymbiont | X89727 | 7 |

| CFB group strain PB90-2 | BSA229236 | 13 |

| CFB group strain A103 | FSU85887 | 8 |

| CFB group strain DF-3 | U41355 | 46 |

| CFB group strain XB45 | BSA229237 | 13 |

| Clone S-B5 | AF029041 | Phelps et al.a |

| Cytophaga flevensis | M58767 | 21 |

| Cytophaga sp. strain BD2-2 | AB015532 | 29 |

| Cytophaga sp. uncultured strain Sva1038 | UCY240979 | 40 |

| Escherichia coli | J01695 | 9 |

| Flavobacterium aquatile | M28236 | 21 |

| Flavobacterium balustinum | M58771 | 21 |

| Flavobacterium ferrugineum | FVBRRDD | 21 |

| Flexibacter canadensis | M62793 | 52 |

| Flexibacter flexilis | M28056 | 52 |

| Sphingobacterium heparinum | M11657 | 49 |

| Sphingobacterium mizutaü | M58796 | 21 |

| Sphingobacterium sp. | AB020206 | Tsukamotob |

| Sphingobacterium spiritivorum | M58778 | 21 |

| Uncultured eubacterium WCHB1-69 | AF050545 | 15 |

| Uncultured eubacterium WCHB1-53 | AF050539 | 15 |

Phelps et al., DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database.

T. Tsukamoto, DDBJ/EMBL/GenBank database.

TABLE 3.

Evolutionary distances among small-subunit rRNAs of various representatives of the CFB phylum

| Organism | Evolutionary distance

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | |

| 1. Escherichia coli | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. Endosymbiont | 0.2059 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3. b-17BO | 0.3093 | 0.3202 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4. b-10RA | 0.3193 | 0.3316 | 0.0129 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5. b-1BO | 0.3171 | 0.3218 | 0.0129 | 0.0243 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 6. b-1BO University of Turin | 0.3375 | 0.3565 | 0.0309 | 0.0293 | 0.0427 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. b-Z43 | 0.3209 | 0.3357 | 0.0169 | 0.0121 | 0.0285 | 0.0210 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8. Strain PB90-2 | 0.2937 | 0.3246 | 0.1813 | 0.1895 | 0.1854 | 0.2043 | 0.1918 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 9. Strain XB45 | 0.2925 | 0.3209 | 0.1803 | 0.1885 | 0.1844 | 0.2032 | 0.1907 | 0.0080 | |||||||||||||||||

| 10. Flavobacterium | 0.3315 | 0.3165 | 0.1979 | 0.2042 | 0.1979 | 0.2237 | 0.2065 | 0.1656 | 0.1646 | ||||||||||||||||

| 11. Cytophaga strain BD-2 | 0.2949 | 0.3183 | 0.1752 | 0.1834 | 0.1752 | 0.2022 | 0.1876 | 0.1062 | 0.1062 | 0.1900 | |||||||||||||||

| 12. Cytophaga strain Sva 1039 | 0.2949 | 0.3218 | 0.1771 | 0.1832 | 0.1781 | 0.2020 | 0.1875 | 0.1145 | 0.1164 | 0.1921 | 0.1099 | ||||||||||||||

| 13. Uncultured strain WCHB1-53 | 0.2892 | 0.3149 | 0.1866 | 0.1949 | 0.1887 | 0.2119 | 0.1971 | 0.1165 | 0.1165 | 0.1850 | 0.1119 | 0.1372 | |||||||||||||

| 14. Uncultured strain WCHB1-69 | 0.2892 | 0.3237 | 0.1764 | 0.1845 | 0.1796 | 0.2024 | 0.1868 | 0.1403 | 0.1384 | 0.2061 | 0.1308 | 0.1509 | 0.1203 | ||||||||||||

| 15. Clone SB5 | 0.2879 | 0.3149 | 0.1639 | 0.1719 | 0.1649 | 0.1916 | 0.1762 | 0.0977 | 0.0958 | 0.1777 | 0.0895 | 0.1218 | 0.1210 | 0.1354 | |||||||||||

| 16. Sphingobacterium sp. | 0.3007 | 0.3118 | 0.1734 | 0.1795 | 0.1716 | 0.1981 | 0.1817 | 0.1772 | 0.1783 | 0.2042 | 0.1732 | 0.1864 | 0.1815 | 0.1744 | 0.1852 | ||||||||||

| 17. Sphingobacterium heparinum | 0.2995 | 0.3155 | 0.1664 | 0.1734 | 0.1666 | 0.1919 | 0.1756 | 0.1844 | 0.1854 | 0.2116 | 0.1803 | 0.1926 | 0.1784 | 0.1754 | 0.1862 | 0.0285 | |||||||||

| 18. Sphingobacterium spiritivorum | 0.3113 | 0.3201 | 0.1736 | 0.1838 | 0.1789 | 0.2028 | 0.1840 | 0.1826 | 0.1805 | 0.2375 | 0.1795 | 0.1826 | 0.1880 | 0.1766 | 0.1814 | 0.1000 | 0.1093 | ||||||||

| 19. Flexibacter canadensis | 0.2991 | 0.3100 | 0.1605 | 0.1696 | 0.1596 | 0.1883 | 0.1718 | 0.1796 | 0.1817 | 0.2126 | 0.1632 | 0.1755 | 0.1829 | 0.1593 | 0.1681 | 0.1025 | 0.1015 | 0.1087 | |||||||

| 20. Sphingobacterium mizutaü | 0.3063 | 0.3268 | 0.1675 | 0.1768 | 0.1770 | 0.1970 | 0.1770 | 0.1687 | 0.1749 | 0.2310 | 0.1770 | 0.1864 | 0.1823 | 0.1688 | 0.1800 | 0.1018 | 0.1018 | 0.0672 | 0.1200 | ||||||

| 21. Bacteroides fragilis | 0.3307 | 0.3512 | 0.2134 | 0.2231 | 0.2136 | 0.2396 | 0.2233 | 0.1749 | 0.1759 | 0.2372 | 0.1789 | 0.1933 | 0.1740 | 0.1924 | 0.1809 | 0.2166 | 0.1966 | 0.2315 | 0.2069 | 0.2248 | |||||

| 22. CFB group strain DF-3 | 0.3381 | 0.3444 | 0.2158 | 0.2276 | 0.2181 | 0.2454 | 0.2289 | 0.1720 | 0.1700 | 0.2093 | 0.1730 | 0.1832 | 0.1834 | 0.1823 | 0.1708 | 0.2147 | 0.2073 | 0.2164 | 0.1932 | 0.2110 | 0.1403 | ||||

| 23. Cytophaga flevensis | 0.3199 | 0.3138 | 0.2008 | 0.2072 | 0.2019 | 0.2260 | 0.2085 | 0.1579 | 0.1589 | 0.0411 | 0.1855 | 0.1762 | 0.1774 | 0.1901 | 0.1793 | 0.2040 | 0.2170 | 0.2246 | 0.2038 | 0.2212 | 0.2253 | 0.2038 | |||

| 24. Flavobacterium aquatile | 0.3236 | 0.3232 | 0.2139 | 0.2204 | 0.2139 | 0.2382 | 0.2227 | 0.1585 | 0.1555 | 0.0537 | 0.1838 | 0.1777 | 0.1748 | 0.1998 | 0.1664 | 0.1969 | 0.2107 | 0.2311 | 0.2182 | 0.2228 | 0.2419 | 0.2178 | 0.0561 | ||

| 25. Flavobacterium balustinum | 0.3313 | 0.3167 | 0.2177 | 0.2266 | 0.2167 | 0.2460 | 0.2290 | 0.1818 | 0.1818 | 0.1659 | 0.1902 | 0.1966 | 0.1758 | 0.1864 | 0.1822 | 0.2036 | 0.2211 | 0.2126 | 0.2087 | 0.2162 | 0.2544 | 0.2248 | 0.1646 | 0.1553 | |

| 26. Flavobacterium ferrugineum | 0.3119 | 0.3194 | 0.2175 | 0.2262 | 0.2199 | 0.2386 | 0.2275 | 0.2262 | 0.2262 | 0.2275 | 0.2132 | 0.2208 | 0.2342 | 0.2254 | 0.2429 | 0.2351 | 0.2328 | 0.2664 | 0.2281 | 0.2668 | 0.2516 | 0.2644 | 0.2239 | 0.2387 | 0.2438 |

All positions used to calculate the distances meet the condition that a known nucleotide is present in all of the sequences analyzed (51). The alignment used was based on sequences from position 177 to position 1457 (E. coli numbering).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic tree for representative 16S rRNA gene sequence from T. borchii mycelium based on nearly complete 16S rRNA sequences. The tree was derived from the evolutionary distances shown in Table 3. The two numbers at each branch node are bootstrap values based on 200 resamplings; the first number is the distance matrix value, and the second number is the parsimony bootstrap value. The sequence of the Burkholderia endosymbiont of G. margarita, an arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus, is included for comparison. Only values greater than 75 are shown. The scale bar represents a 10% difference in nucleotide sequences, as determined by measuring the lengths of the horizontal lines connecting two species. Uncu eubact, uncultivated eubacterium.

CFB bacterium in T. borchii hyphal tissue.

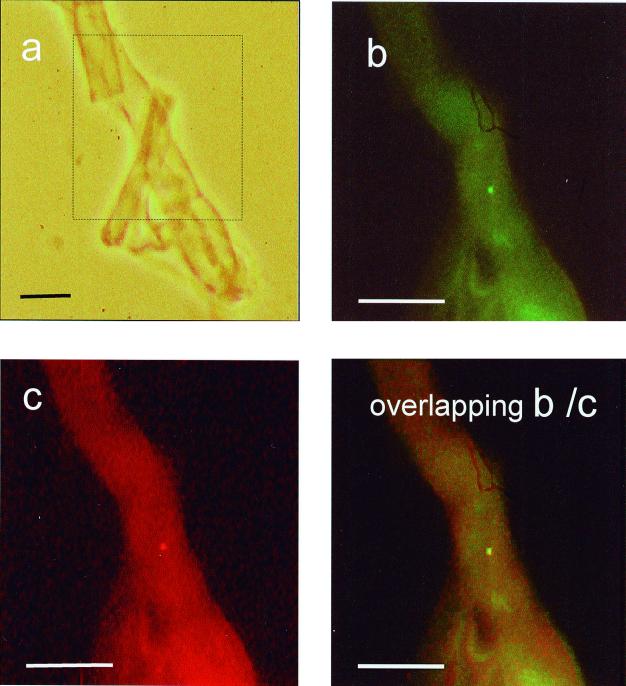

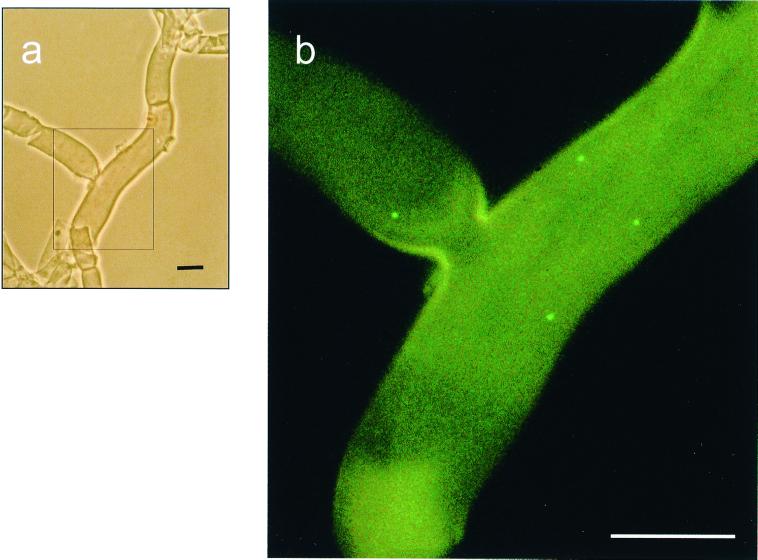

The CFB bacterium in the hyphal tissue of the fungus T. borchii was analyzed by FISH. Mycelium homogenate was stained with DAPI and hybridized with three different 16S rRNA-targeted FISH probes (Table 1); the first probe, EUB338 (positions 338 to 355) (1), was specific for the eubacterial domain, the second probe, CF319 (positions 319 to 336) (2, 32), was specific for the Cytophaga-Flexibacter group, and the third probe, STBb-654 (positions 654 to 672), was specifically designed on the basis of the 16S rDNA sequence (b-17BO) of the bacterium detected by PCR in mycelium strain 17BO. Two sets of hybridization were performed with the 17BO mycelium strain; one set was performed with EUB338 and specific probe STBb-654, and one set was performed with EUB338 and CF319, followed by DAPI staining of the same sample. Each set included an unstained sample used as a control for autofluorescence.

In these experiments the same cell which hybridized with the eubacterial probe (EUB338) was fluorescent with CF319 or STBb-654, and DAPI staining confirmed (Fig. 4) the presence of the CFB bacterium in the 17BO mycelium strain. Double hybridization with the CF319 and EUB338 probes was also carried out with 1BO, 10RA, and Z43, and this analysis showed the presence of fluorescent cells in all of the samples examined. In all of the FISH experiments no autofluorescence from the samples was observed. To clarify the location of the CFB bacterium in the ectomycorrhizal fungus, thin sections of T. borchii mycelium tissue were hybridized with EUB338, the general bacterial probe used for the homogenate. Few cells per septum hybridized with the general bacterial probe. In contrast, the difficulty of determining the exact position of the CFB bacterium with respect to the cytoplasm or the hyphal wall was evident, and it was difficult to determine where the bacterium was located since hybridization was successful in homogenate samples and in sections in which the hyphal wall was heterogeneously fragmented.

FIG. 4.

(a) Phase-contrast micrograph of T. borchii hyphal tissue homogenate. (b) Detail of the same sample after hybridization with fluorescein-labeled eubacterial probe EUB338. (c) Detail of the same sample after hybridization with CY3-labeled probe specific for b-17BO. The panel on the lower right is an overlap of panels b and c showing the same cell hybridizing with both EUB338 and STBb-654 specific for the CFB bacterium. Scale bars, 5 μm.

DISCUSSION

This paper describes molecular characterization of a CFB bacterium that is found in the mycorrhizal T. borchii mycelium and has not been cultured yet. PCR assays demonstrated that this uncultured CFB bacterium is present in all of the mycelia of T. borchii studied and in in vitro ectomycorrhizae. Simultaneous hybridization of the general eubacterial and specific probes with the hyphal tissues revealed rare, small (diameter, 0.3 to 0.5 μm) but viable CFB bacteria within the hyphae (Fig. 3 and 4).

FIG. 3.

Detection of the CFB bacterium associated with T. borchii Vittad. hyphal tissue (mycelial strain 17BO). (a) Phase-contrast micrograph of T. borchii hyphal tissue homogenate. (b) Same sample after hybridization with fluorescein-labeled eubacterial probe EUB338. Fluorescent CFB cells are visible. Scale bars, 5 μm.

Although several recent papers have described numerous bacteria, such as members of the genus Pseudomonas, the Bacillaceae, and the Actinomycetes, living among the hyphae of the fruiting bodies of truffles (3, 14, 20), no molecular characterizations of these bacteria or the microbe-host associations are available. In general, few data for uncultured bacteria in fungi have been presented (11, 12, 50), and only recently have a few phylogenetic studies identified an endophytic bacterium that is the endosymbiont of G. margarita and is a member of the genus Burkholderia (7) and members of the alpha and beta subclasses of the Proteobacteria detected in ectomycorrhizae of F. sylvatica, L. vellereus, and L. subdulcis (33).

To our knowledge, no member of the Cytophagales has been identified previously in ectomycorrhizal symbioses. Although uncultivated CFB bacteria have been detected in soil environments (30), few of these bacteria have been described as symbionts and commensals (25). The discovery of a CFB bacterium in the T. borchii ectomycorrhizal mycelium and molecular characterization of this organism represent a starting point for systematic molecular identification and functional studies of bacterium-fungus-plant symbioses. Concerning phylogenetic position, we found that the overall tree topology is consistent with other 16S rDNA phylogenetic analyses (4, 28, 38, 52), and for all analyses, the bootstrap values supporting the new cluster were significant for all of the criteria used (distance matrix, parsimony, maximum likelihood). However, since few environmental 16S rDNA sequences from soil bacteria are nearly full length, it is not possible to know if the CFB bacterium is closely related to other uncultivated soil bacteria. A decision about rank and a formal description must await the availability of more nearly complete sequences from environmental samples and phenotypic data.

The question of whether the new CFB bacterium is involved in the life cycle of the T. borchii truffle remains to be answered. PCR products obtained by using the specific b-17BO-f primer with templates from the mycelia and ectomycorrhizae and the probes used in the FISH experiment showed that this bacterium is a stable component of the T. borchii mycelium. This study provides the first direct evidence that a not-yet-cultured CFB bacterium is detectable in association with a mycorrhizal fungus of the genus Tuber.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by “Progetto Strategico CNR-Regioni Tuber: Biotecnologia della micorrizazione.”

We thank G. Chevalier (INRA, Clermont Ferrant, France), B. Citterio (University of Urbino), G. Macino (University La Sapienza, Rome, Italy), and L. Garnerio (University of Turin) for providing samples and the Molecular Evolution Workshop '98 staff at the Marine Biological Laboratory, Woods Hole, Mass., for the phylogenetic analyses.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Krumholz L, Stahl D A. Fluorescent-oligonucleotide probing of whole cells for determinative, phylogenetic, and environmental studies in microbiology. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:762–770. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.2.762-770.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bedini S, Bagnoli G, Sbrana C, Leporini C, Tola E, Dunne C, Filippi C, D'Andrea F, O'Gara F, Nuti M P. Pseudomonads isolated from within fruit bodies of T. borchii are capable of producing biological control or phytostimulatory compounds in pure culture. Symbiosis. 1999;26:223–236. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bernadet J F, Segers P, Vancanneyt M, Berthe F, Kesters K, Vandamme P. Cutting a Gordian knot: emended classification and description of the genus Flavobacterium, emended description of the family Flavobacteriaceae, and proposal of Flavobacterium hydatis nom. nov. (basonym, Cytophaga aquatilis Strohl and Tait 1978) Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:128–148. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bertini L, Agostini D, Potenza L, Rossi I, Zeppa S, Zambonelli A, Stocchi V. Molecular markers for the identification of the ectomycorrhizal fungus Tuber borchii. New Phytol. 1998;139:565–570. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bertini L, Potenza L, Zambonelli A, Amicucci A, Stocchi V. RFLP species-specific patterns in the identification of white truffles. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;164:397–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bianciotto V, Bandi C, Minerdi D, Sironi M, Tichy H V, Bonfante P. An obligately endosymbiotic mycorrhizal fungus itself harbors obligately intracellular bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3005–3010. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.8.3005-3010.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bowman J P, McCammon S A, Brown M V, Nichols D S, McMeekin T A. Diversity and association of psychrophilic bacteria in Antarctic sea ice. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3068–3078. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.8.3068-3078.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brosius J, Palmer M L, Kennedy P J, Noller H F. Complete nucleotide sequence of a 16S ribosomal RNA gene from Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:4801–4805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell R, Greaves M P. Anatomy and community structure of the rhizosphere. In: Lynch J M, editor. The rhizosphere. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley & Sons; 1990. pp. 11–34. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang K-P, Dasch G A, Weiss E. Endosymbionts of fungi and invertebrates other than arthropods. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. pp. 833–836. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chanway C P. Endophytes: they're not just fungi! Can J Bot. 1996;74:321–322. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chin K J, Hahn D, Hengstmann U, Liesack W, Janssen P H. Characterization and identification of numerically abundant culturable bacteria from the anoxic bulk soil of rice paddy microcosms. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5042–5049. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.11.5042-5049.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Citterio B, Cardoni P, Potenza L, Amicucci A, Stocchi V, Gola G, Nuti M P. Isolation of bacteria from sporocarps of Tuber magnatum Pico, Tuber borchii Vittad. and Tuber maculatum Vitt.: identification and biochemical characterization. In: Stocchi V, Bonfante P, Nuti M P, editors. Biotechnology of ectomycorrhizae. Molecular approaches. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corporation; 1995. pp. 241–248. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dojka M A, Hugenholtz P, Haack S K, Pace N R. Microbial diversity in a hydrocarbon- and chlorinated-solvent-contaminated aquifer undergoing intrinsic bioremediation. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3869–3877. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3869-3877.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duponnois R, Garbaye J. Some mechanisms involved in growth stimulation of ectomycorrhizal fungi by bacteria. Can J Bot. 1992;68:2148–2152. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Erland S, Henrion B, Martin F, Glover L A, Alexander I J. Identification of the ectomycorrhizal basidiomycete Tylospora fibrillosa Donk by RFLP analysis of the PCR-amplified ITS and IGS regions of ribosomal DNA. New Phytol. 1993;12:525–532. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1994.tb04251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP (phylogeny inference package) version 3.5c. Seattle: Department of Genetics, University of Washington; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felske A, Englen B, Nubel U, Backhaus H. Direct ribosomal isolation from soil to extract bacterial rRNA for community analysis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4162–4167. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4162-4167.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gazzanelli G, Malatesta M, Pianetti A, Baffone W, Stocchi V, Citterio B. Bacteria associated to fruit bodies of the ecto-mycorrhizal fungus Tuber borchii Vittad. Symbiosis. 1999;26:211–222. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gherna R, Woese C R. A partial phylogenetic analysis of the “Flavobacter-Bacteroides” phylum: basis for taxonomic restructuring. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1992;15:513–521. doi: 10.1016/S0723-2020(11)80110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbert D. SeqPup sequence editor version 0.5. Bloomington: Indiana University Biology Department; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harley J L, Smith S E. Mycorrhizal symbiosis. London, United Kingdom: Academic Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henrion B, Chevalier G, Martin F. Typing truffle species by PCR amplification of the ribosomal DNA spacers. Mycol Res. 1994;98:37–43. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hugenholtz P, Goebel M B, Pace N R. Impact of culture-independent studies on the emerging phylogenetic view of bacterial diversity. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:4765–4774. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.18.4765-4774.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kochel H G, Kuntzel H. Nucleotide sequence of the Aspergillus nidulans mitochondrial gene coding for the small ribosomal subunit RNA: homology to E. coli 16S rRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1981;9:5689–5696. doi: 10.1093/nar/9.21.5689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuske C H, Barns S M, Bush J. Diverse uncultivated bacterial groups from soil of the arid southwestern United States that are present in many geographic regions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3614–3621. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3614-3621.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L, Kato C, Horikoshi K. Bacterial diversity in deep-sea sediments from different depths. Biodivers Conserv. 1999;8:659–677. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liesack W, Stackebrandt E. Occurrence of novel groups of the domain Bacteria as revealed by analysis of genetic material isolated from an Australian terrestrial environment. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5072–5078. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.15.5072-5078.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maidak B L, Olsen G J, Larsen N, Overbeek R, McCaughey M J, Woese C R. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:109–110. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.1.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manz W, Amann R I, Ludwig W, Vancanneyt M, Schleifer K H. Application of a suite of 16S rRNA-specific oligonucleotide probes designed to investigate bacteria of the phylum Cytophaga-Flavobacter-Bacteroides in the natural environment. Microbiology. 1996;142:1097–1106. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mogge B, Loferer C, Agerer R, Hutzler P, Hartmann A. Bacterial community structure and colonization patterns of Fagus sylvatica. Ectomycorrhizospheres as determined by fluorescence in situ hybridization and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Mycorrhiza. 2000;5:271–278. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molina R. Pure culture synthesis and host specificity of red alder mycorrhizae. Can J Bot. 1979;57:1223–1228. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mosse B. Honey colored, sessile endogone spores. II. Changes in fine structure during spore development. Arch Microbiol. 1970;74:129–145. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ovreas L, Torsvik V. Microbial diversity and community structure in two different agricultural soil communities. Microb Ecol. 1998;36:303–315. doi: 10.1007/s002489900117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Page R D M. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput Applic Biosci. 1996;12:357–358. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.4.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paster J B, Dewhirst F E, Olsen I, Fraser G. Phylogeny of Bacteroides, Prevotella, and Porphyromonas spp. and related bacteria. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:725–732. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.725-732.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pegler D N, Spooner B M, Young T W K. British truffles. A revision of British hypogeous fungi. Kew, United Kingdom: Royal Botanic Garden; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ravenschlag K, Sahm K, Pernthaler J, Amann R. High bacterial diversity in permanently cold marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:3982–3989. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.9.3982-3989.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Saltarelli R, Ceccaroli P, Vallorani L, Zambonelli A, Citterio B, Malatesta M, Stocchi V. Biochemical and morphological modifications during the growth of Tuber borchii mycelium. Mycol Res. 1998;102:403–409. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sisti D, Zambonelli A, Giomaro G, Rossi I, Ceccaroli P, Citterio B, Benedetti P A, Stocchi V. In vitro mycorrhizal synthesis of micropropagated Tilia platyphyllos Scop. plantlets with Tuber borchii Vittad. mycelium in pure culture. Acta Hortic (ISHS) 1998;457:379–387. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tavaglini J, Bolchi A, Percudani R, Petrucco S, Rossi G L, Ottonello S. Testing a selected region of Tuber mitochondrial small subunit rDNA as molecular marker for evolutionary and bio-diversity studies. In: Stocchi V, Bonfante P, Nuti M P, editors. Biotechnology of ectomycorrhizae. Molecular approaches. New York, N.Y: Plenum Publishing Corporation; 1995. pp. 205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Trappe J M. The orders, families, and genera of hypogeus Ascomycotina (truffles and their relatives) Mycotaxon. 1979;9:297–340. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vandamme P, Vancanneyt M, van Belkum A, Segers P, Quint W G V, Kersters K, Paster B J, Dewhirst F E. Polyphasic analysis of strains from the genus Capnocytophaga and Centers for Disease Control group DF-3. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:782–791. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-3-782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Varese G C, Portinaro S, Trotta A, Scannerini S, Luppi-Mosca A M, Martinotti M G. Bacteria associated with Suillus grevillei sporocarps and ectomycorrhizae and their effects on in vitro growth of the mycobiont. Symbiosis. 1996;21:129–147. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Weisburg W G, Barns M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weisburg W G, Oyaizu Y, Oyaizu H, Woese C R. Natural relationship between Bacteroides and flavobacteria. J Bacteriol. 1985;164:230–236. doi: 10.1128/jb.164.1.230-236.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilson D. Endophyte: the evolution of a term, and clarification of its use and definition. Oikos. 1995;73:274–276. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Woese C R, Gutell R, Gupta R, Noller H F. Detailed analysis of the higher-order structure of the 16S-like ribosomal ribonucleic acids. Microbiol Rev. 1983;47:621–699. doi: 10.1128/mr.47.4.621-669.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Woese C R, Yang D, Mandelco L, Stetter K O. The Flexibacter-Flavobacter connection. Syst Appl Microbiol. 1990;13:161–165. [Google Scholar]