Abstract

DNA aptamers have been widely used as biosensors for detecting a variety of targets. Despite decades of success, they have not been applied to monitor any targets in plants, even though plants are a major platform for providing oxygen, food, and sustainable products ranging from energy fuels to chemicals, and high-value products such as pharmaceuticals. A major barrier to progress is a lack of efficient methods to deliver DNA into plant cells. We herein report a thiol-mediated uptake method that more efficiently delivers DNA into Arabidopsis and tobacco leaf cells than another state-of-the-art method, DNA nanostructures. Such a method allowed efficient delivery of a glucose DNA aptamer sensor into Arabidopsis for sensing glucose. This demonstration opens a new avenue to apply DNA aptamer sensors for functional studies of various targets, including metabolites, plant hormones, metal ions, and proteins in plants for a better understanding of the biodistribution and regulation of these species and their functions.

A thiol-mediated uptake method efficiently delivers a DNA aptamer-based biosensor into plants for glucose detection.

INTRODUCTION

DNA and RNA aptamers have emerged as a major class of biosensors for a variety of targets (1, 2) including metal ions (3), small organic metabolites (4, 5), proteins (6), cells (7), and viruses (8–10). A distinguishing advantage of these sensors is that aptamers for many targets, including targets that do not have natural receptors in biology or emerging targets such as SARS-CoV-2 (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2), can be obtained from screening a large pool of DNA libraries with up to 1015 sequences through systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment (SELEX) (11–14). The resulting aptamers can be readily conjugated to reporters, such as fluorophore/quencher pairs (15), organic dyes (16), or nanoparticles (17), to transduce the conformational changes of aptamers upon target binding into signal changes of reporters (18). Compared to natural receptors such as antibodies, aptamers are much smaller, more stable, and easier for scale-up manufacturing (19, 20). The facile conjugation of the DNA with organelle-directing (21) or optical-responsive (22) groups has allowed spatiotemporal controls of imaging targets in different organelles using light. By virtue of these advantages, aptamer biosensors have been applied to environmental monitoring (23), food safety (24), medical diagnostics (25), and imaging (1). Despite the rapid progress that has been made in DNA aptamer biosensors, including imaging of many targets in mammalian cells (26), they have not been applied to imaging plant cells.

Plants are essential to our daily life because they provide food, oxygen, shelter, and other benefits. In particular, much attention has been received from their emerging role as a major platform to produce sustainable products ranging from energy fuels to chemicals, as well as high-value products such as cosmetics and pharmaceuticals (27). However, the progress in better understanding and genetically engineering biological processes in various plant species, especially economic plant species for improving agriculture traits or economic traits, remains slow, which is largely due to a lack of highly efficient and cost-effective methods to deliver nucleic acids into plant cells. In contrast to the well-established methods of delivering nucleic acids into mammalian cells across the plasma membranes, the presence of plant cell walls made up of mainly cross-linked polysaccharides limits the delivery of nucleic acids into plant cells (28, 29).

Although several delivery systems have been used, including those based on biologicals [e.g., agrobacteria (30)], biolistic particles (31–33) [e.g., tungsten particles (34)], and nanomaterials (e.g., single-wall carbon nanotubes) (35–42), some challenges, such as low transformation or delivery efficiency and potential damage or perturbation of the plant (43, 44), remain. For example, a broccoli riboswitch RNA aptamer was introduced into plant cells with the help of Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101 and was used to detect mRNA transcripts for transgene identification and track an RNA virus invasion in plant cells (45). However, such a reporter system only works for mRNAs at the transcriptional level, limiting its application to other targets, such as metal ions, small molecules, or proteins, which require the delivery of aptamer-based biosensors with modifications (i.e., fluorophores, quenchers, etc.). In addition, DNA nanostructures such as DNA tetrahedrons have recently been reported as effective carriers to deliver small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) into intact plant cells (46), but their low delivery efficiency and instability in low-salt conditions (47) limit usability in broad applications. Therefore, there is still a major demand for developing highly efficient and cost-effective methods to deliver nucleic acids to efficiently bypass the cell walls and pass through membranes of a variety of plants without the aid of external force (43).

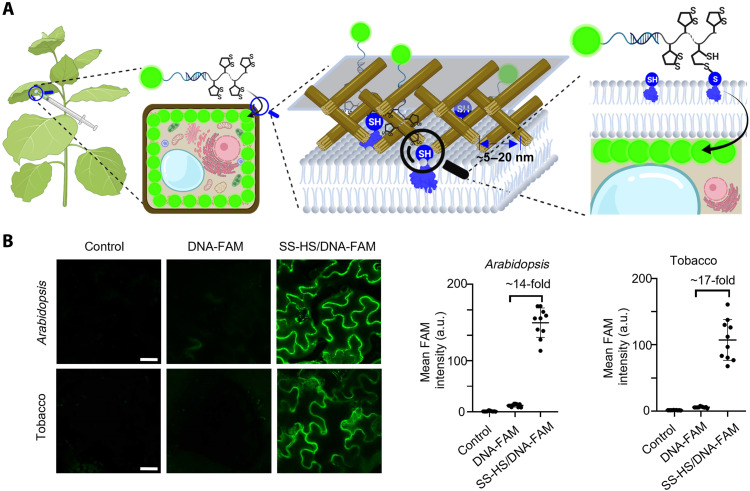

To achieve this goal, we have to overcome two potential barriers for DNA/RNA delivery into the cytoplasm of plant cells, namely, cell walls and plasma membranes, considering the structure of the intact plant cells. Different from the mammalian cells, plant cells have a cell wall composed of cross-linked polysaccharides. The pore size of cell walls ranges from 5 to 20 nm (43, 48) (Fig. 1A), which means that any particles with diameters greater than these pores can be limited in their ability to pass through such a cell wall. Therefore, a delivery system must overcome this barrier in addition to the plasma membrane before entering the cytoplasm (48), and we hypothesize that a plant delivery system with a size < 20 nm would have a better chance to penetrate different matrix pores of cell walls, if not the best. The second barrier, the plasma membrane, is similar to that of mammalian cells, sharing features (49) such as similar cellular uptake pathways and a protein disulfide-thiol interchange activity (50, 51). Thus, we can take advantage of advances made in cargo delivery to mammalian cells and translate them into plant systems, as long as we have a method to overcome the first barrier of the plant cell wall (43).

Fig. 1. Thiol-mediated uptake in plant cells.

(A) Schematic illustration of the infiltration and internalization of SS-HS/DNA-FAM into plant leaf cells through thiol-mediated uptake (all the schemes were created with BioRender.com). (B) Confocal images of Arabidopsis leaf and tobacco leaf infiltrated with control (hybridization buffer), DNA-FAM, and SS-HS/DNA-FAM 24 hours after infiltration. Scale bars, 25 μm. Quantitative comparison of different delivery methods using fluorescence intensity of images on the left side. Means ± SD; n = 10. a.u., arbitrary units.

Thiols or disulfides have been used to facilitate mammalian cell uptake of different cargoes (52) such as drugs (53, 54), proteins (53), antisense oligos (54, 55), siRNA (55), quantum dots (56), liposomes (57), and polysomes (57) through dynamic covalent disulfide exchange with thiol-containing transporters on the cell surface. Of particular interests to this work, the Abe group reported that oligonucleotides with a terminus conjugated with five disulfide units could reach the cytoplasm of HeLa cells within 10 min after being added to the cultured cells (55). Despite the broad applications in other biological systems, thiol-mediated uptake has not been applied to plant systems.

Here, we report the thiol-mediated uptake method as a delivery platform of nucleic acids into plants (Fig. 1A). We found that this method can be applied to Arabidopsis and tobacco. We then compared the delivery efficiency of thiol-mediated uptake with that of a DNA nanostructure–mediated delivery method in plant cells for fluorophore-modified single-stranded DNA delivery and concluded that our method has ~2-fold higher efficiency. Furthermore, we investigated the mechanistic thiol-mediated DNA delivery into plant cells. Last, we demonstrated that a thiol-conjugated glucose DNA aptamer sensor could detect glucose differences between Arabidopsis thaliana wild type (WT) and Arabidopsis double mutant [atsweet11;12, SWEET (Sugar Will Eventually be Exported Transporter)] that accumulates higher sugar relative to the WT (58).

RESULTS

Effective delivery of DNA to plant leaves and roots through thiol-mediated uptake

Encouraged by the success of thiol-mediated uptake in mammalian cells, we synthesized a disulfide-modified helper strand 5′-ACA CGG TCG TT/iSp18//SS/15-3′ (called SS-HS) that contains an 18-atom hexa-ethylene glycol spacer (denoted as /iSp18/) and 15 repeating units of disulfides (denoted as /SS/). Such an oligo has a size of less than 20 nm to meet the cell wall exclusion limit. We then hybridized SS-HS with 5′-CGA CCG TGT AAC CGC TTC CCC GAC TTC C/36-FAM/-3′ (called DNA-FAM) that contains fluorescein (FAM) covalently conjugated to the DNA and provides green fluorescence to monitor the delivery of DNA. The resulting hybridized double-stranded oligo is called SS-HS/DNA-FAM. As shown in fig. S1, the mean fluorescence intensity of the SS-HS/DNA-FAM group is ~21 times higher than that of DNA-FAM without the repeat disulfide units in HeLa cells. This result is consistent with the previous report (55), suggesting that the repeat disulfide units are quite effective in delivering the DNA oligo into the HeLa cells. Then, we moved on to test this method in Arabidopsis and tobacco (Fig. 1A). After infiltrating the leaves for 24 hours, we used confocal microscopy to image the uptake and found that the fluorescence intensity of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in Arabidopsis leaf and tobacco leaf was 14-fold and 17-fold higher than that of DNA-FAM, respectively (Fig. 1B), demonstrating that the repeat disulfide units can enhance the delivery of nucleic acids into plant cells with high efficiency. Furthermore, subcellular localization analysis of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in plant cells indicates that the delivered DNAs are located in the cytosol of Arabidopsis cells (fig. S2). These results support that the repeat disulfide unit–mediated DNA delivery method is efficient and effective in plant leaves.

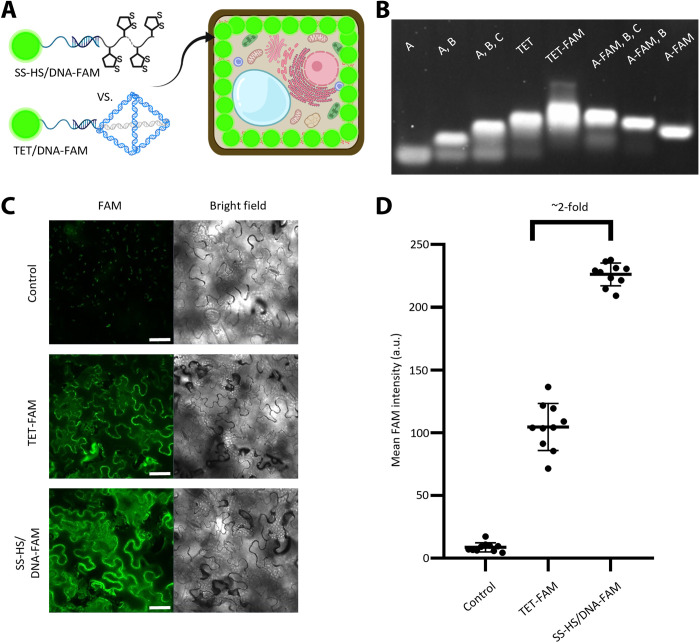

Recently, a three-dimensional DNA tetrahedron has been used as an effective method for the delivery of biomolecules into plants (46). Because our thiol-mediated uptake is a new method for nucleic acids to enter plant cells, its delivery efficiency was compared with that using DNA tetrahedron (Fig. 2A). A DNA tetrahedron labeled with FAM (called TET-FAM) was assembled following the reported method (46), and its formation was confirmed using native polyacrylamide gel (Fig. 2B). To make a fair comparison, we conducted the concentration-dependent fluorescence intensity measurement between TET-FAM and SS-HS/DNA-FAM. As shown in fig. S3, the same concentration of TET-FAM and SS-HS/DNA-FAM resulted in a similar FAM fluorescence intensity, which indicates that FAM fluorescence intensity is positively correlated with either TET-FAM or SS-HS/DNA-FAM accumulation. To provide a better comparison, we infiltrated 1 μM SS-HS/DNA-FAM and 1 μM TET-FAM in tris-acetic-EDTA-Mg2+ buffer to the different spots of the same tobacco leaf. The fluorescence intensity of the SS-HS/DNA-FAM–treated leaf was ~2-fold higher than that of the TET-FAM–treated leaf (Fig. 2, C and D) 24 hours after infiltration, supporting that the thiol-mediated uptake is more efficient than the DNA tetrahedron in DNA delivery.

Fig. 2. Comparison between the DNA nanostructure–mediated delivery method and the thiol-mediated uptake method.

(A) Schematic illustration of the internalization of SS-HS/DNA-FAM and TET-FAM into tobacco leaves. (B) Native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (5%) analysis verifies that the TET-FAM exhibits a similar assembly behavior to the normal TET, resulting in the synthesis of TET-FAM with the same architecture. (C) Confocal images of tobacco leaves infiltrated with control (tris-acetic-EDTA-Mg2+ buffer), TET-FAM, and SS-HS/DNA-FAM 24 hours after infiltration. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D) Fluorescence intensity analysis of confocal images in (C). Means ± SD; n = 10.

Uptake kinetics and mechanism of SS-HS/DNA-FAM

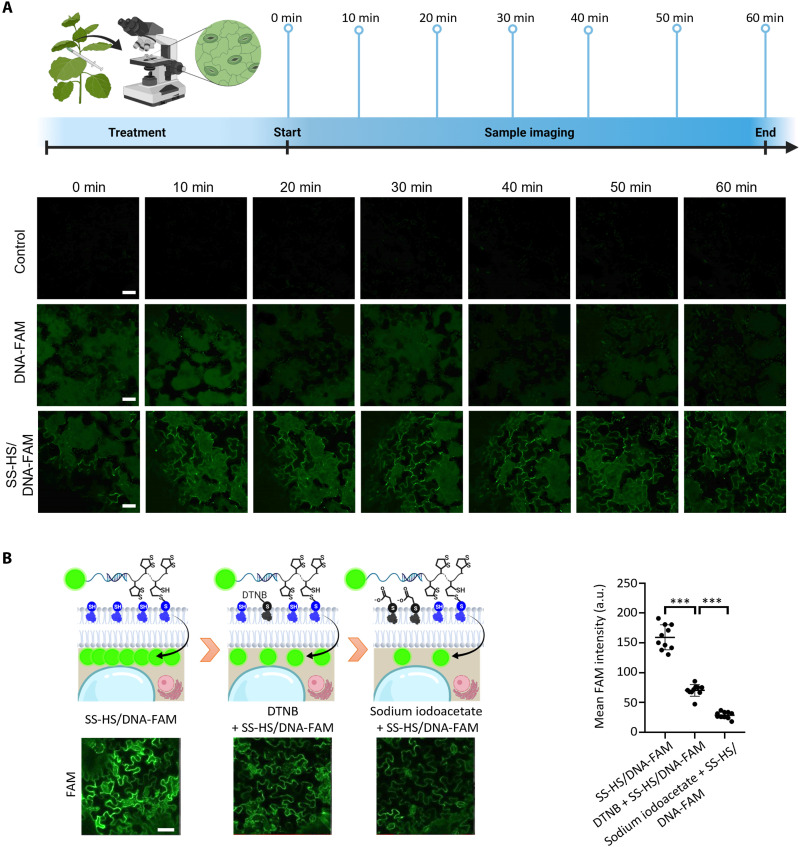

To assess how fast the repeat disulfide unit–assistant DNA delivery can happen, we conducted a time course study of thiol-mediated uptake in plant cells (Fig. 3A). A similar FAM fluorescence intensity of DNA-FAM and SS-HS/DNA-FAM was observed at 0 min after infiltration, which results from the same amount of DNA-FAM and SS-HS/DNA-FAM infiltrated into the cell wall space. A strong fluorescence signal of SS-HS/DNA-FAM could be detected outlining the leaf shape, an indication of successful delivery, at 10 min after infiltration, suggesting that repeat disulfide–modified DNA can enter plant cells quickly, similar to the delivery time of 10 min for HeLa cells reported by the Abe group (55). However, DNA-FAM did not produce a strong fluorescence signal as SS-HS/DNA-FAM showed even 60 min after infiltration (Fig. 3A). The uptake mechanism of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in plant cells might be different from that of the thiol-mediated uptake reported in the mammalian cells. Thus, the uptake mechanism of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in plant cells is further studied. To verify that the uptake process is through thiol-mediated uptake, Ellman’s reagent [5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), a weak thiol-mediated uptake inhibitor] (59) and an irreversible thiol-uptake inhibitor, sodium iodoacetate (a strong thiol-mediated uptake inhibitor) (55), were used to infiltrate the tobacco leaves. Then, the treated tobacco leaves were further infiltrated by SS-HS/DNA-FAM. The fluorescence intensity of the tobacco leaves infiltrated by both inhibitors and SS-HS/DNA-FAM was compared with that of tobacco leaves only infiltrated by SS-HS/DNA-FAM (Fig. 3B). As shown in the confocal images of Fig. 3B, the fluorescence intensity of the tobacco leaves infiltrated by SS-HS/DNA-FAM is more intense than that of the tobacco leaves infiltrated by DTNB + SS-HS/DNA-FAM, and the fluorescence intensity of the tobacco leaves infiltrated by DTNB + SS-HS/DNA-FAM is stronger than that of the tobacco leaves infiltrated by sodium iodoacetate + SS-HS/DNA-FAM. The mean fluorescence intensity was further quantified. The mean fluorescence intensity of DTNB + SS-HS/DNA-FAM decreased to ~44.3% of SS-HS/DNA-FAM, and the fluorescence intensity of sodium iodoacetate + SS-HS/DNA-FAM is decreased to ~18.2% of SS-HS/DNA-FAM, indicating that the uptake process is efficiently inhibited by the thiol-mediated uptake inhibitors. Therefore, we can conclude that the uptake process is through thiol-mediated uptake. Together, these results indicate that the uptake of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in plants is a time-dependent and thiol-mediated process.

Fig. 3. Uptake kinetics and mechanism of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in tobacco leaves.

(A) Schematic illustration of the time course uptake study of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in tobacco leaf cells. Confocal images of tobacco leaf infiltrated with control (hybridization buffer), DNA-FAM, and SS-HS/DNA-FAM 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min after infiltration. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Schematic illustration of the uptake study of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in tobacco leaf, tobacco leaf infiltrated with DTNB (a weak thiol-mediated uptake inhibitor), and tobacco leaf infiltrated with sodium iodoacetate (a strong thiol-mediated uptake inhibitor). Confocal images of the uptake study of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in tobacco leaf, tobacco leaf infiltrated with DTNB, and tobacco leaf infiltrated with sodium iodoacetate (left panel). Scale bar, 50 μm. Quantitative comparison of the uptake study of SS-HS/DNA-FAM in tobacco leaf, tobacco leaf infiltrated with DTNB, and tobacco leaf infiltrated with sodium iodoacetate (right panel). Means ± SD; n = 10; ***P < 0.001, t test.

Application of the thiol-mediated method for delivering a DNA aptamer sensor in plant cells for glucose sensing

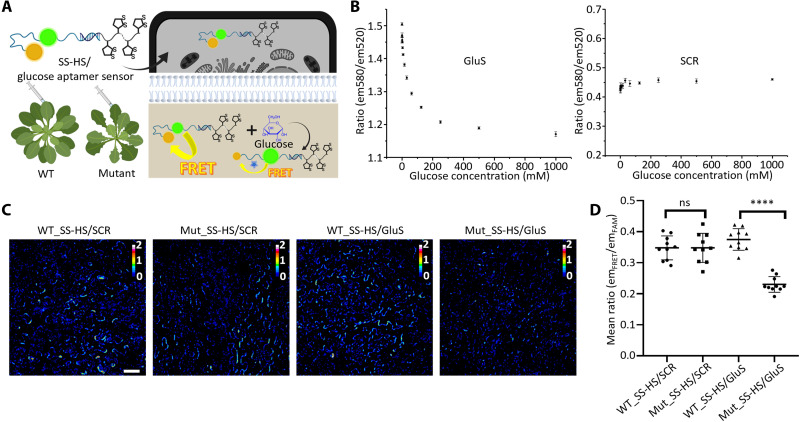

To provide another example of applying the thiol-mediated delivery method, we investigated delivering DNA aptamer glucose sensor to plant cells and evaluated its functional effects by imaging the difference of glucose concentration in leaf cells between WT Arabidopsis and Arabidopsis atsweet11;12 double mutant [glucose concentration in the leaf cells of this mutant has been reported ~2-fold higher than that of the WT Arabidopsis (58)]. Different from protein-based sensors, aptamer-based sensors are more stable under harsh conditions, such as at a high temperature or in organic solvent, and are much smaller to traverse plant cell walls that have a size exclusion limit ranging from 5 to 20 nm. Therefore, aptamer-based sensors have a huge potential to detect many important targets inside plants. For example, the aptamer for glucose reported in 2018 (60) showed high selectivity over other sugars, including galactose and fructose. To test how well this aptamer sensor binds glucose versus sucrose, an abundant sugar in plants, we measured fluorescence signals from the sensor in the presence of glucose, sucrose, galactose, or fructose. As shown in fig. S4, the aptamer sensor exhibited much higher fluorescence in the presence of glucose than any other sugars, confirming the high selectivity of the aptamer sensor to glucose. However, to our knowledge, there is no report of DNA aptamer-based sensors for detecting targets in plant cells (45), probably due to the lack of a proper delivery method. To demonstrate the power of thiol-mediated delivery method to address this major issue, SS-HS was hybridized with a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) sensor for glucose (60) via base pair recognition (SS-HS/GluS) (Fig. 4A). As shown in Fig. 4B, for this particular sensor, when the donor is excited, there is a reversible correlation between the ratio of acceptor emission to donor emission and the concentration of glucose, namely, a higher ratio means a lower glucose level. However, the FRET ratio of the scramble sequence with the same length and guanine-cytosine content will not change with different glucose concentrations. Thus, SS-HS was also hybridized with the scramble sequence as a control (SS-HS/SCR). Encouraged by this result, SS-HS/GluS and SS-HS/SCR were infiltrated into the leaves of WT Arabidopsis and Arabidopsis atsweet11;12 double mutants to sense the glucose concentration difference. Then, the infiltrated leaves were harvested to image for acquiring the emission intensity of the donor (FAM), the FRET, and the acceptor tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA) using confocal microscopy. The obtained data were analyzed and calculated by Fiji. The fluorescence signals of FAM, TAMRA, and FRET could be used to calculate the FRET ratio of the glucose aptamer sensor. As shown in the FRET ratio part of Fig. 4 (C and D), the FRET ratio of WT Arabidopsis leaves infiltrated by SS-HS/GluS is statistically higher than that of atsweet11;12 mutant leaves infiltrated by SS-HS/GluS. In contrast, no obvious change could be found in the FRET ratio images of WT Arabidopsis leaves infiltrated with SS-HS/SCR compared with that of atsweet11;12 mutant leaves infiltrated with SS-HS/SCR. The results suggest that the glucose concentration of atsweet11;12 leaf cells is higher than that of WT leaf cells, which is consistent with the reported glucose concentration difference between atsweet11;12 leaves and WT leaves characterized by gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (58).

Fig. 4. Glucose sensing with glucose aptamer sensor delivered via thiol-mediated uptake in WT Arabidopsis and Arabidopsis atsweet11;12 double mutants.

(A) Schematic illustration of the infiltration, uptake of SS-HS/glucose aptamer sensor, and the glucose aptamer sensor’s FRET ratio change after conformation rearrangement upon binding to glucose in WT Arabidopsis and Arabidopsis atsweet11;12 double mutants. (B) The FRET responses between donor, FAM, and acceptor (TAMRA) were monitored with respect to increasing glucose concentrations for glucose aptamers and scrambled control. Means ± SD; n = 3. em580, emission at 580 nm; em520, emission at 520 nm. (C) The FRET ratio images of WT Arabidopsis leaf cells and atsweet11;12 mutant leaf cells infiltrated by SS-HS/SCR and SS-HS/GluS. Scale bar, 50 μm. (D) Quantification of the FRET ratio images of WT Arabidopsis leaf cells and atsweet11;12 mutant leaf cells infiltrated by SS-HS/SCR and SS-HS/GluS. Means ± SD; n = 10; ****P < 0.0001, t test. ns, not significant.

DISCUSSION

DNA aptamers have been widely applied as biosensors in environmental monitoring, food safety detection, medical diagnostics, and monitoring targets for many years. They are particularly successful in monitoring many targets in mammalian cells but have not been applied to imaging targets in plant cells, largely due to difficulty in delivering them into plant cells. In this work, we rationally designed a small-sized thiol-mediated uptake delivery system that can pass through the plant cell walls that are known to restrict molecules varied from 5 to 20 nm, while taking advantage of cellular uptake pathways of disulfide-thiol interchange in plant cells similar to mammalian cells as reported (50, 51). We found that this delivery method could enable fast and efficient nucleic acid delivery in Arabidopsis and tobacco, and the thiol-mediated uptake in plants is a time-dependent process, which is sensitive to traditional thiol-mediated uptake inhibitors. We were able to deliver glucose DNA aptamer sensors successfully and efficiently into Arabidopsis WT and atsweet11;12 double mutant and observed their difference in glucose level as a readout by FRET ratio differences.

Because aptamers for many targets have already been obtained and aptamers for new targets can be readily obtained through SELEX, the demonstrated success in this work will open a new avenue to develop different DNA aptamer sensors to monitor a wide range of targets—from metabolites to plant hormones, metal ions, and proteins—for better understanding plant biological processes, including spatial and temporal distribution changes in metabolites, protein levels, ion nutrients, and heavy metal contaminations, in response to intrinsic and external stimuli during plant growth and development. In addition, organelle-targeting sensor delivery could potentially be achieved in plants because the success of the DNA aptamer sensors have been shown to monitor many targets in different organelles of mammalian cells with high spatial and temporal resolution (61). In addition to delivering aptamer sensors into plant cells, thiol-mediated delivery can potentially be used to deliver a variety of antisense DNA and RNA molecules plant viruses attenuation or gene knockdown for gene functional studies, especially when the mutation of a gene is lethal or extremely harmful to plants. Therefore, the method developed in this work will have a major impact on other areas of plant research when efficient delivery of nucleic acids is required.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Glucose, Hepes, tris, and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Inc. (St. Louis, USA). The SS-HS sequence was synthesized on an ABI 392 DNA/RNA synthesizer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA), and synthesis reagents were purchased from Glen Research Corporation. Hybridization buffer consists of the following: 50 mM Hepes, 100 mM NaCl, and 5 mM MgCl2 (pH 7.4). Tris-acetic-EDTA-Mg2+ buffer is composed of the following: 40 mM tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA, and 12.5 mM magnesium acetate. Single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides were obtained from and purified either by Integrated DNA Technologies Inc. or using 10% denatured polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gel. All oligonucleotide sequences are listed in table S1.

Plant growth and transformation

A. thaliana (Columbia ecotype) and tobacco Nicotiana benthamiana were grown under the long-day condition (16 hours of light and 8 hours of darkness) in a growth room at 22°C. As regards plasmid constructs and plant transformation, the full-length Arabidopsis SWEET1 coding sequence was cloned into the entry vector pENTR/D-TOPO via Not I and Asc I. Then, SWEET1 was switched to binary vectors pGWB654 via a recombination reaction between attL and attR sites to create 35S:ATSWEET1-mRFP. Arabidopsis plants were transformed with the standard floral dip methods. Transformants were selected on one-half Murashige-Skoog medium (MS) supplemented with glufosinate ammonium (25 μg/ml).

Spectroscopic methods

The DNA concentration of all DNA strands was determined with a NanoDrop One spectrophotometer. FRET measurements were performed on a FluoroMax-2 fluorometer (Horiba Jobin Yvon Inc., Edison, NJ) or a BioTek Synergy H1 hybrid reader (BioTek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA). Confocal microscopy images were recorded with a Zeiss LSM 880 or 710 microscope.

FRET test in vitro

Samples contained 200 nM SS-HS/GluS or SS-HS/SCR in 2× hybridization buffer. The sample solution was then mixed with an equivalent volume of glucose solution and incubated for 40 min at room temperature. The FRET efficiencies were evaluated using the ratio of the fluorescence intensity of TAMRA (emission at 580 nm) to that of FAM (emission at 520 nm) using excitation at 488 nm.

Cell culture

HeLa cells (American Type Culture Collection) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics [penicillin (100 U/ml) and streptomycin (100 U/ml)] at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2.

Cellular uptake studies of single-stranded DNA with the help of disulfide-modified helper DNA strand

HeLa cells were seeded at ~9 × 104 cells per well in a 24-well plate and cultured overnight. Then, the cells were incubated with control (hybridization buffer), FAM-labeled single-stranded DNA solution (DNA-FAM), or FAM-labeled single-stranded DNA hybridized with SS-HS solution (SS-HS/DNA-FAM) at an equivalent concentration of FAM (1 μM) for 3 hours at 37°C. The cells were incubated for 3 hours at 37°C, the medium was removed, and the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline before detachment. The detached cells were ready for flow cytometry (BD LSR II, BD Biosciences) detection.

Thiol-mediated uptake in plant cells

Plant leaves, including Arabidopsis and tobacco, were infiltrated by DNA-FAM and SS-HS/DNA-FAM at an equivalent concentration of FAM (1 μM) for 24 hours. Then, the infiltrated leaves were harvested for confocal imaging using the following setting: exciting wavelength of 488 nm, emission from 48 to 558 nm, and gain 600. For the inhibition studies, two inhibitors including a weak thiol-mediated uptake inhibitor DTNB and a strong thiol-mediated uptake inhibitor sodium iodoacetate were infiltrated into the tobacco leaves before the DNA infiltration. The remaining steps are the same as the regular uptake study.

Subcellular localization of SS-HS/DNA-FAM

The leaves of transgenic Arabidopsis expressing monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP) were infiltrated with 1 μM SS-HS/DNA-FAM for 24 hours. The infiltrated leaves were harvested for confocal imaging. The confocal images were collected using the following setting: exciting wavelength of 488 nm for FAM, emission from 488 to 558 nm, and gain 850; exciting wavelength of 561 nm for RFP, emission from 561 to 656 nm, and gain 820.

Time course study of thiol-mediated uptake in Arabidopsis leaf cells

The leaves of Arabidopsis were infiltrated by control (hybridization buffer), 1 μM DNA-FAM, and 1 μM SS-HS/DNA-FAM. Then, the infiltrated leaves were harvested at 0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, and 60 min for confocal imaging. The confocal images were collected using the following setting: exciting wavelength of 488 nm for FAM, emission from 491 to 625 nm, and gain 550.

Concentration-dependent fluorescence intensity measurement between TET-FAM and SS-HS/DNA-FAM

The FAM fluorescence intensity of TET-FAM and SS-HS/DNA-FAM with different FAM concentrations (125, 250, 500, and 1000 nM) was measured by using a BioTek Synergy H1 hybrid reader (excitation wavelength: 488 nm; emission wavelength: 520 nm).

DNA tetrahedron (TET) synthesis and characterization

TET or FAM-labeled TET was assembled through annealing of four predesigned single-stranded DNA oligonucleotides (A, B, C, and D) or (A-FAM, B, C, and D), respectively. To verify the successful assembly of TET-FAM, 5% native polyacrylamide gel was run to compare the mobility of TET-FAM with that of TET.

Comparison between the DNA nanostructure–mediated delivery method and the thiol-mediated uptake method in plant cells

To compare the delivery efficiency of the DNA nanostructure–mediated delivery method and thiol-mediated uptake in plant cells, tobacco leaves were infiltrated with control (tris-acetic-EDTA-Mg2+ buffer), SS-HS/DNA-FAM, and TET-FAM at different parts of the same leaf at an equivalent concentration of FAM (1 μM) for 24 hours. The infiltrated leaves were harvested for confocal imaging and analyzed by Fiji software. The confocal images were collected using the following setting: exciting wavelength of 488 nm, emission from 488 to 558 nm, and gain 726.9.

Selectivity of the glucose aptamer

The glucose sensing strand and glucose capture strand were hybridized to achieve 50 nM for the sensing strand and 250 nM for the capture strand through the typical annealing procedure (60). The FAM fluorescence in the glucose sensing strand was quenched by the quencher in the glucose capture strand. Different sugars including galactose, fructose, glucose, and sucrose at the final concentration of 800 mM were added to test the selectivity of the glucose aptamer. Once glucose is bound to the glucose sensing strand, it would kick out the capture strand with a quencher, thus recovering the FAM fluorescence. The FAM fluorescence intensities were recorded by using a FluoroMax-2 fluorometer (excitation wavelength: 488 nm; emission wavelength: 520 nm).

Glucose detection in plant cells

The sixth true leaf numbered from the bottom of 6-week-old Arabidopsis WT or atsweet11;12 double mutant was infiltrated at the end of the light period with SS-HS/GluS and SS-HS/SCR at an equivalent concentration of DNA (1 μM) for 24 hours. Then, the infiltrated leaves were harvested for confocal imaging of the donor (FAM) fluorescence, the FRET fluorescence, and the acceptor (TAMRA) fluorescence. The confocal images were captured using the following setting: exciting wavelength of 488 nm for FAM (emission from 495 to 562 nm), gain 880, and for FRET signal (emission from 572 to 650 nm), gain 680; exciting wavelength of 561 nm for TAMRA (emission from 572 to 650 nm), gain 680; and exciting wavelength of 633 nm for chlorophyll (emission from 659 to 759 nm), gain 700. The obtained data were processed following the previous publications using Fiji with some modifications (62–64). Briefly, we calculated the FRET ratio by (FRET · chlorophyll (reverse threshold))/(FAM · chlorophyll(reverse threshold)) · TAMRA (after threshold), which only considered the pixels where the glucose sensors were delivered by minimizing overlapping pixels from both the glucose sensor and chlorophyll. For TAMRA (after threshold), we defined real TAMRA emission signal as 1 (referred as white) and background signal as 0 (referred as black) using auto local threshold (method = Bernsen radius = 15 parameter_1 = 0 parameter_2 = 0 white); then, we divided the value by 255 to convert the initial 8-bit color given to the value range of 0.0 to 1.0. After chlorophyll (after threshold) was inverted, FRET · chlorophyll (reverse threshold) indicated the FRET signal intensity of the pixels without chlorophyll signal. FAM · chlorophyll (reverse threshold) meant the FAM signal intensity of the pixels with no chlorophyll signals showing up. (FRET · chlorophyll (reverse threshold))/(FAM · chlorophyll (reverse threshold)) · TAMRA (after threshold) meant the ratio signals (FRET · chlorophyll (reverse threshold))/(FAM · chlorophyll (reverse threshold)) of the pixels only represented the signals from the glucose sensors delivered. The images produced were displayed in 16-bit color, and the brightness/contrast was adjusted to 0 to 2.0. Then, regions representing the FRET ratios were manually circled (avoiding dot-like background signals), and the average value was calculated on the basis of the selected area.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was funded by the DOE Center for Advanced Bioenergy and Bioproducts Innovation (U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under award number DE-SC0018420). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Energy. We also thank the Robert A. Welch Foundation (grant F-0020) for support of the Lu group research program at the University of Texas at Austin.

Author contributions: Conceptualization: Q.M., Y.L., and L.-Q.C. Experiments: Q.M., X.X., Y.M., M.B., V.G., W.G., J.W., and T.S. Supervision: Y.L. and L.-Q.C. Writing—Original draft: Q.M. and X.X. Writing—Review and editing: Q.M., X.X., Y.M., Y.L., and L.-Q.C.

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S4

Table S1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Song S., Wang L., Li J., Fan C., Zhao J., Aptamer-based biosensors. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 27, 108–117 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamula C. L. A., Guthrie J. W., Zhang H., Li X.-F., Le X. C., Selection and analytical applications of aptamers. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 25, 681–691 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Qu H., Csordas A. T., Wang J., Oh S. S., Eisenstein M. S., Soh H. T., Rapid and label-free strategy to isolate aptamers for metal ions. ACS Nano 10, 7558–7565 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huizenga D. E., Szostak J. W., A DNA aptamer that binds adenosine and ATP. Biochemistry 34, 656–665 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yu H., Alkhamis O., Canoura J., Liu Y., Xiao Y., Advances and challenges in small-molecule DNA aptamer isolation, characterization, and sensor development. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 16800–16823 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou Y., Qi X., Liu Y., Zhang F., Yan H., DNA-nanoscaffold-assisted selection of femtomolar bivalent human α-thrombin aptamers with potent anticoagulant activity. Chembiochem 20, 2494–2503 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shangguan D., Li Y., Tang Z., Cao Z. C., Chen H. W., Mallikaratchy P., Sefah K., Yang C. J., Tan W., Aptamers evolved from live cells as effective molecular probes for cancer study. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 11838–11843 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peinetti A. S., Lake R. J., Cong W., Cooper L., Wu Y., Ma Y., Pawel G. T., Toimil-Molares M. E., Trautmann C., Rong L., Mariñas B., Azzaroni O., Lu Y., Direct detection of human adenovirus or SARS-CoV-2 with ability to inform infectivity using DNA aptamer-nanopore sensors. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh2848 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Song Y., Song J., Wei X., Huang M., Sun M., Zhu L., Lin B., Shen H., Zhu Z., Yang C., Discovery of aptamers targeting the receptor-binding domain of the SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein. Anal. Chem. 92, 9895–9900 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kacherovsky N., Yang L. F., Dang H. V., Cheng E. L., Cardle I. I., Walls A. C., McCallum M., Sellers D. L., DiMaio F., Salipante S. J., Corti D., Veesler D., Pun S. H., Discovery and characterization of spike N-terminal domain-binding aptamers for rapid SARS-CoV-2 detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21211–21215 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellington A. D., Szostak J. W., In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346, 818–822 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tuerk C., Gold L., Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249, 505–510 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellington A. D., Szostak J. W., Selection in vitro of single-stranded DNA molecules that fold into specific ligand-binding structures. Nature 355, 850–852 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho M., Soo Oh S., Nie J., Stewart R., Eisenstein M., Chambers J., Marth J. D., Walker F., Thomson J. A., Soh H. T., Quantitative selection and parallel characterization of aptamers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 18460–18465 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nutiu R., Li Y., Structure-switching signaling aptamers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 125, 4771–4778 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y., Huang J., Yang X., Quan K., Xie N., Ou M., Tang J., Wang K., Aptamer-based FRET nanoflares for imaging potassium ions in living cells. Chem. Commun. 52, 11386–11389 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X., Wang F., Aizen R., Yehezkeli O., Willner I., Graphene oxide/nucleic-acid-stabilized silver nanoclusters: Functional hybrid materials for optical aptamer sensing and multiplexed analysis of pathogenic DNAs. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11832–11839 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang J., Smaga L. P., Satyavolu N. S. R., Chan J., Lu Y., DNA aptamer-based activatable probes for photoacoustic imaging in living mice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17225–17228 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li L., Xu S., Yan H., Li X., Yazd H. S., Li X., Huang T., Cui C., Jiang J., Tan W., Nucleic acid aptamers for molecular diagnostics and therapeutics: Advances and perspectives. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 2221–2231 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn M. R., Jimenez R. M., Chaput J. C., Analysis of aptamer discovery and technology. Nat. Rev. Chem. 1, 0076 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shao Y., Zhao J., Yuan J., Zhao Y., Li L., Organelle-specific photoactivation of DNA nanosensors for precise profiling of subcellular enzymatic activity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 8923–8931 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tan Z., Feagin T. A., Heemstra J. M., Temporal control of aptamer biosensors using covalent self-caging to shift equilibrium. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 6328–6331 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li D., Song S., Fan C., Target-responsive structural switching for nucleic acid-based sensors. Acc. Chem. Res. 43, 631–641 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amaya-González S., De-los-Santos-Álvarez N., Miranda-Ordieres A. J., Lobo-Castañón M. J., Aptamer-based analysis: A promising alternative for food safety control. Sensors 13, 16292–16311 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kacherovsky N., Cardle I. I., Cheng E. L., Yu J. L., Baldwin M. L., Salipante S. J., Jensen M. C., Pun S. H., Traceless aptamer-mediated isolation of CD8+ T cells for chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 3, 783–795 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zheng D., Seferos D. S., Giljohann D. A., Patel P. C., Mirkin C. A., Aptamer nano-flares for molecular detection in living cells. Nano Lett. 9, 3258–3261 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Philippini R. R., Martiniano S. E., Ingle A. P., Franco Marcelino P. R., Silva G. M., Barbosa F. G., dos Santos J. C., da Silva S. S., Agroindustrial byproducts for the generation of biobased products: Alternatives for sustainable biorefineries. Front. Energy Res. 8, 152 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Varner J. E., Lin L.-S., Plant cell wall architecture. Cell 56, 231–239 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jat S. K., Bhattacharya J., Sharma M. K., Nanomaterial based gene delivery: A promising method for plant genome engineering. J. Mater. Chem. B 8, 4165–4175 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newell C. A., Plant transformation technology: Developments and applications. Mol. Biotechnol. 16, 53–65 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y., Liang Z., Zong Y., Wang Y., Liu J., Chen K., Qiu J.-L., Gao C., Efficient and transgene-free genome editing in wheat through transient expression of CRISPR/Cas9 DNA or RNA. Nat. Commun. 7, 12617 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.S. Ueki, S. Magori, B. Lacroix, V. Citovsky, Transient gene expression in epidermal cells of plant leaves by biolistic DNA delivery, in Biolistic DNA Delivery: Methods and Protocols, S. Sudowe, A. B. Reske-Kunz, Eds. (Humana Press, 2013), pp. 17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.R. Banakar, K. Wang, Biolistic transformation of Japonica rice varieties, in Biolistic DNA Delivery in Plants: Methods and Protocols, S. Rustgi, H. Luo, Eds. (Springer US, 2020), pp. 163–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanford J. C., The biolistic process. Trends Biotechnol. 6, 299–302 (1988). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Demirer G. S., Zhang H., Matos J. L., Goh N. S., Cunningham F. J., Sung Y., Chang R., Aditham A. J., Chio L., Cho M.-J., Staskawicz B., Landry M. P., High aspect ratio nanomaterials enable delivery of functional genetic material without DNA integration in mature plants. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 456–464 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lew T. T. S., Park M., Wang Y., Gordiichuk P., Yeap W.-C., Mohd Rais S. K., Kulaveerasingam H., Strano M. S., Nanocarriers for transgene expression in pollen as a plant biotechnology tool. ACS Mater. Lett. 2, 1057–1066 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwak S.-Y., Lew T. T. S., Sweeney C. J., Koman V. B., Wong M. H., Bohmert-Tatarev K., Snell K. D., Seo J. S., Chua N.-H., Strano M. S., Chloroplast-selective gene delivery and expression in planta using chitosan-complexed single-walled carbon nanotube carriers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 447–455 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Demirer G. S., Zhang H., Goh N. S., Pinals R. L., Chang R., Landry M. P., Carbon nanocarriers deliver siRNA to intact plant cells for efficient gene knockdown. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz0495 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lew T. T. S., Park M., Cui J., Strano M. S., Plant nanobionic sensors for arsenic detection. Adv. Mater. 33, 2005683 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Giraldo J. P., Landry M. P., Faltermeier S. M., McNicholas T. P., Iverson N. M., Boghossian A. A., Reuel N. F., Hilmer A. J., Sen F., Brew J. A., Strano M. S., Plant nanobionics approach to augment photosynthesis and biochemical sensing. Nat. Mater. 13, 400–408 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lew T. T. S., Koman V. B., Silmore K. S., Seo J. S., Gordiichuk P., Kwak S.-Y., Park M., Ang M. C.-Y., Khong D. T., Lee M. A., Chan-Park M. B., Chua N.-H., Strano M. S., Real-time detection of wound-induced H2O2 signalling waves in plants with optical nanosensors. Nat. Plants 6, 404–415 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong M. H., Giraldo J. P., Kwak S.-Y., Koman V. B., Sinclair R., Lew T. T. S., Bisker G., Liu P., Strano M. S., Nitroaromatic detection and infrared communication from wild-type plants using plant nanobionics. Nat. Mater. 16, 264–272 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cunningham F. J., Goh N. S., Demirer G. S., Matos J. L., Landry M. P., Nanoparticle-mediated delivery towards advancing plant genetic engineering. Trends Biotechnol. 36, 882–897 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sanzari I., Leone A., Ambrosone A., Nanotechnology in plant science: To make a long story short. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 7, 120 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bai J., Luo Y., Wang X., Li S., Luo M., Yin M., Zuo Y., Li G., Yao J., Yang H., Zhang M., Wei W., Wang M., Wang R., Fan C., Zhao Y., A protein-independent fluorescent RNA aptamer reporter system for plant genetic engineering. Nat. Commun. 11, 3847 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H., Demirer G. S., Zhang H., Ye T., Goh N. S., Aditham A. J., Cunningham F. J., Fan C., Landry M. P., DNA nanostructures coordinate gene silencing in mature plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 7543–7548 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ponnuswamy N., Bastings M. M. C., Nathwani B., Ryu J. H., Chou L. Y. T., Vinther M., Li W. A., Anastassacos F. M., Mooney D. J., Shih W. M., Oligolysine-based coating protects DNA nanostructures from low-salt denaturation and nuclease degradation. Nat. Commun. 8, 15654 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang P., Lombi E., Zhao F.-J., Kopittke P. M., Nanotechnology: A new opportunity in plant sciences. Trends Plant Sci. 21, 699–712 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schwab F., Zhai G., Kern M., Turner A., Schnoor J. L., Wiesner M. R., Barriers, pathways and processes for uptake, translocation and accumulation of nanomaterials in plants—Critical review. Nanotoxicology 10, 257–278 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Morre D. J., de Cabo R., Jacobs E., Morre D. M., Auxin-modulated protein disulfide-thiol-interchange activity from soybean plasma membranes. Plant Physiol. 109, 573–578 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Morré D. J., Jacobs E., Sweeting M., de Cabo R., Morré D. M., A protein disulfide-thiol interchange activity of HeLa plasma membranes inhibited by the antitumor sulfonylurea N-(4-methylphenylsulfonyl)-N′-(4-chlorophenyl)urea (LY181984). Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 1325, 117–125 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gasparini G., Bang E.-K., Montenegro J., Matile S., Cellular uptake: Lessons from supramolecular organic chemistry. Chem. Commun. 51, 10389–10402 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fu J., Yu C., Li L., Yao S. Q., Intracellular delivery of functional proteins and native drugs by cell-penetrating poly(disulfide)s. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 12153–12160 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu C., Qian L., Ge J., Fu J., Yuan P., Yao S. C. L., Yao S. Q., Cell-penetrating poly(disulfide) assisted intracellular delivery of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for inhibition of miR-21 function and detection of subsequent therapeutic effects. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 128, 9418–9422 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shu Z., Tanaka I., Ota A., Fushihara D., Abe N., Kawaguchi S., Nakamoto K., Tomoike F., Tada S., Ito Y., Kimura Y., Abe H., Disulfide-unit conjugation enables ultrafast cytosolic internalization of antisense DNA and siRNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 6611–6615 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Derivery E., Bartolami E., Matile S., Gonzalez-Gaitan M., Efficient delivery of quantum dots into the cytosol of cells using cell-penetrating poly(disulfide)s. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 10172–10175 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chuard N., Gasparini G., Moreau D., Lörcher S., Palivan C., Meier W., Sakai N., Matile S., Strain-promoted thiol-mediated cellular uptake of giant substrates: Liposomes and polymersomes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 2947–2950 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen L.-Q., Qu X.-Q., Hou B.-H., Sosso D., Osorio S., Fernie A. R., Frommer W. B., Sucrose efflux mediated by SWEET proteins as a key step for phloem transport. Science 335, 207–211 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Laurent Q., Martinent R., Lim B., Pham A.-T., Kato T., López-Andarias J., Sakai N., Matile S., Thiol-mediated uptake. JACS Au 1, 710–728 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nakatsuka N., Yang K.-A., Abendroth J. M., Cheung K. M., Xu X., Yang H., Zhao C., Zhu B., Rim Y. S., Yang Y., Weiss P. S., Stojanović M. N., Andrews A. M., Aptamer–field-effect transistors overcome Debye length limitations for small-molecule sensing. Science 362, 319–324 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hong S., Zhang X., Lake R. J., Pawel G. T., Guo Z., Pei R., Lu Y., A photo-regulated aptamer sensor for spatiotemporally controlled monitoring of ATP in the mitochondria of living cells. Chem. Sci. 11, 713–720 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., Tinevez J.-Y., White D. J., Hartenstein V., Eliceiri K., Tomancak P., Cardona A., Fiji: An open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jones A. M., Danielson J. Å., ManojKumar S. N., Lanquar V., Grossmann G., Frommer W. B., Abscisic acid dynamics in roots detected with genetically encoded FRET sensors. eLife 3, e01741 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Xue X., Yu Y.-C., Wu Y., Xue H., Chen L.-Q., Locally restricted glucose availability in the embryonic hypocotyl determines seed germination under abscisic acid treatment. New Phytol. 231, 1832–1844 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S4

Table S1