Abstract

Background

Medical gender affirmation (i.e., hormone use) is one-way transgender (trans) people affirm their gender and has been associated with health benefits. However, trans people face stigmatization when accessing gender-affirming healthcare, which leads some to use non-prescribed hormones (NPHs) that increase their risk for poor health.

Purpose

We examined whether healthcare policy stigma, as measured by state-level trans-specific policies, was associated with NPHs use and tested mediational paths that might explain these associations. Because stigmatizing healthcare policies prevent trans people from participation in healthcare systems and allow for discrimination by healthcare providers, we hypothesized that healthcare policy stigma would be associated with NPHs use by operating through three main pathways: skipping care due to anticipated stigma in healthcare settings, skipping care due to cost, and being uninsured.

Methods

We conducted analyses using data from the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. The analytic sample included trans adults using hormones (N = 11,994). We fit a multinomial structural equation model to examine associations.

Results

Among trans adults using hormones, we found that healthcare policy stigma was positively associated with NPHs use and operated through insurance coverage and anticipating stigma in healthcare settings. The effect sizes on key predictor variables varied significantly between those who use supplemental NPHs and those who only use NPHs suggesting the need to treat NPHs use as distinct from those who use supplemental NPHs.

Conclusions

Our work highlights the importance of healthcare policy stigma in understanding health inequities among trans people in the USA, specifically NPHs use.

Keywords: Transgender, Hormone use, Gender affirmation, Structural stigma, Policy, Insurance

Among transgender adults using hormones, we found that stigmatizing healthcare policies were positively associated with non-prescribed hormones use and operated through insurance coverage and anticipating stigma in healthcare settings.

Introduction

Gender affirmation is the social process by which one’s gender identity, expression, or role is recognized and affirmed [1]. Transgender (trans) individuals, including gender nonbinary people, experience gender affirmation in many ways. Gender affirmation is comprised of four different but interconnected dimensions: social, psychological, legal, and medical [2]. Specifically, Reisner et al. [2] describe social affirmation as interpersonal recognition (e.g., using the correct name and pronouns), psychological affirmation as the internal felt sense of self-actualization (e.g., validation of self), legal affirmation as the recognition by legal systems of one’s gender (e.g., legal name and gender marker changes), and medical affirmation as the use of medical technologies to affirm one’s gender (e.g., hormones, gender affirmation surgery, and puberty blockers). The majority of research has focused on medical gender affirmation, specifically hormone use [3, 4]. Hormone use, like other forms of gender affirmation, has been associated with a range of positive health outcomes, including reductions in suicidal ideation, binge-drinking, drug use, anxiety, and depression and an increase in quality of life among trans people who use them for medical gender affirmation [4–7].

Hormone use needs and receipt vary within trans populations. For example, 20% of participants in a large national survey indicated they did not want hormones, and among those who wanted hormones, only half had ever accessed them [8]. Notably, many people are unable to access hormones from a licensed medical professional and turn to non-prescribed hormones (NPHs). Not being able to access prescribed hormones (PHs) can force people to go without or to access NPHs by purchasing them online, obtaining them from friends, or acquiring them via some other non-licensed source [9–11]. Furthermore, merely having access to a doctor does not guarantee access to hormones, as doctors may refuse to prescribe hormones, insurance may refuse to cover hormone prescriptions, or people may be unable to afford hormones due to out-of-pocket costs or lack of insurance [8]. Moreover, structural stigma may affect the availability of hormones by operating as an impediment to accessing PHs, which is discussed below [12].

Given the aforementioned barriers, trans people have developed alternative ways to access the healthcare they need, including hormones; however, some of these alternatives may be risky [13]. Access to PHs is important because NPHs significantly increase the risk of poor health outcomes due to improper dosing and the lack of monitoring [14, 15]. While the long-term effects of any hormone use are unclear, some studies have shown an increased risk for adverse cardiometabolic indicators after beginning hormone therapy [16]; therefore, the current medical guidelines recommend that doctors closely monitor their patients’ cardiometabolic health while taking hormones [17]. For example, some formulations of oral estrogen increase the risk of venous thromboembolism and are therefore no longer prescribed by most clinicians; however, trans people who use non-prescribed estrogen often take high dosages of these formulations, increasing their risk for venous thromboembolism [18]. Furthermore, some people may use high doses of NPHs in conjunction with PHs because they believe this will achieve faster results, placing them at risk of adverse health effects [15]. Researchers have also speculated that NPHs may increase the risk of HIV infection due to sharing needles or parenteral administration, although no study has formally linked these two [19].

Stigma as a Social Determinant of Health

There has been an increasing recognition that stigma is a fundamental cause of population health inequities among trans populations [10, 20, 21]. Hatzenbuehler et al. [22] define stigma as “the cooccurrence of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination in a context in which power is exercised.” In the USA, the dominant and pervasive ideology on gender is that men and women are biologically distinct and inherently possess certain psychological and behavioral traits derived from reproductive functions [23]. This ideology conflates gender with sex, creating what we refer to as the gender/sex fallacy [23]. The gender/sex fallacy alienates people whose gender identity or expression are discordant with the gender typically aligned with their sex assigned at birth, or whose gender identity or expression does not align with the man-woman binary. Further, the gender/sex fallacy provides a rationale for stigmatization, promoting the discrimination and stereotyping of trans people [10].

The majority of research regarding stigma in trans populations has focused on interpersonal or individual forms of stigma, such as victimization (e.g., physical or emotional abuse a trans person encounters), internalized stigma (e.g., internalizing negative societal messages about oneself as a trans person), or anticipating and avoiding stigma (e.g., the presumption that one might be victimized and avoids instances where victimization may be a threat) [21, 24]. While interpersonal and individual stigma is critical to understanding the health of trans people, these are not the only means by which stigma impacts health. White Hughto et al. [10] argue that we must consider how stigma operates across multiple levels, including structural forms of stigma, such as policies that limit the resources, opportunities, and wellbeing of trans people. For example, stigmatizing policies may act as structural impediments that constrain trans peoples’ access to hormones by mandating that Medicaid cannot cover trans-related care, even if a doctor deems medical interventions necessary [25]. Furthermore, religious exemption laws allow doctors to deny trans people any healthcare services so long as they claim this exemption [26]. Religious exemption laws not only affect access to hormones but also to any healthcare service for trans people. Together, these policies result in healthcare policy stigma, which we conceptualize as stigma resulting from policies that govern healthcare systems and demean, devalue, and restrict the healthcare of trans people.

Thus, healthcare policy stigma is a specific form of structural stigma that may constrain the ability of trans people to access care that meets their gender affirmation needs by operating through two pathways: anticipated stigma and cost. Healthcare policy stigma may allow violence and discrimination in medical settings to go unchecked, increasing individuals’ fear or anticipation of encountering stigma in healthcare contexts and driving healthcare avoidance [27]. Additionally, healthcare policy stigma may increase the out-of-pocket cost for accessing hormones by allowing insurers to refuse to cover hormone-related care. Lastly, healthcare policy stigma may influence trans people’s insurance rates as some may choose not to participate in a healthcare system that is not built to meet their needs [13]. Thus, healthcare policy stigma may be a critical factor for understanding why people use NPHs.

Purpose and Hypotheses

The purpose of this paper is to examine whether healthcare policy stigma is associated with using NPHs and test possible mediational pathways in a sample of trans people who use hormones. Previous research demonstrates associations between state-level policies and health among transgender populations [20, 28, 29] including findings that demonstrate that state-level policy stigma is associated with decreases in hormone use for medical gender affirmation [12]. However, this study builds on this work to demonstrate, for the first time, the mechanisms through which state-level policy stigma may work to influence NPHs use. Importantly, the literature on NPHs has predominantly treated NPHs use as a dichotomous outcome: any NPHs use versus no NPHs use [9, 30]. Simply treating NPHs use as a dichotomous outcome may not capture people who supplement their PHs with NPHs, suggesting a third group [15]. Given that risk factors for only using NPHs may be different from those who supplement their PHs with NPHs, this paper seeks to understand whether healthcare policy stigma is differentially associated with exclusive NPHs use or supplemental NPHs use.

We posit that healthcare policy stigma operates through two pathways to contribute to any form of NPHs use: skipping care due to cost and anticipating stigma. Figure 1 presents the conceptual model to be tested. First, we hypothesize that living in a state with high levels of healthcare policy stigma will be associated with skipping care due to anticipated stigma and cost, which will increase the chances of using supplemental NPHs and using only NPHs compared to those who only use PHs.

Fig. 1.

Multinomial model predicting non-prescribed hormone use.

Note: Model controlled for gender identity, race/ethnicity, age, education, Census region, unemployment, sex work, physical/verbal abuse, engagement with other trans people, experiencing homelessness, and family support. Medicaid expansion was included as a control when predicting uninured.

Second, we hypothesize that healthcare policy stigma will be associated with a higher probability of being uninsured and skipping needed healthcare due to cost. Trans people may be less likely or able to participate in a healthcare system that allows for discrimination and will be more likely to pay out of pocket for their care. We posit that, in turn, increases in the uninsured rate and skipping care due to cost will increase the likelihood of both supplemental NPHs use and only using NPHs compared to those who only use PHs.

Materials and Methods

This study is a secondary data analysis of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey (USTS), conducted among a national sample of trans people in the USA and sponsored by the National Center for Transgender Equality [8]. Data were collected in August and September of 2015. The National Center for Transgender Equality worked with over 400 organizations across the USA to recruit nearly 28,000 respondents via social media and email. While these data were collected in 2015, they remain the largest source of information on NPHs use in trans populations in the USA. Surveys were completed on web-enabled devices (e.g., computers, tablets, and smartphones) and were made accessible to respondents with disabilities using screen readers. Surveys were available in English and Spanish. For more information on methods, see the 2015 USTS report [8]. The original data collection was approved by the University of California Los Angeles Institutional Review Board and the secondary analyses were ruled exempt by the University of Michigan Institutional Review Board.

Sample

The National Center for Transgender Equality recruited 27,715 people for the project. Eligibility for the project included (a) identifying as trans or some other gender-diverse individual, (b) being at least 18 years of age, and (c) living in the USA. We then limited our analytic sample to those who reported currently using hormones (n = 12,044). Respondents who identified as cross-dressers were removed from the sample because their experiences are fundamentally different than those with other trans identities (n = 20). Respondents who lived on a military base or one of the U.S. territories at the time of data collection were also removed from the sample because we could not calculate a healthcare policy stigma score for these areas and the means of accessing hormones on a military base is different than in the rest of the USA (n = 30). Our final overall sample included 11,994 respondents.

Measures

NPHs use

Current NPHs use was coded into three nominal categories: currently using PHs, supplemental NPHs, and NPHs. Respondents were asked “Where do you currently get your hormones?” and selected one of three responses. Those who chose “I only go to licensed professionals (like a doctor) for hormones” were coded as PHs only. Those who chose “In addition to licensed professionals, I also get hormones from friends, online, or other non-licensed sources” were coded as supplemental NPHs. And those who chose “I ONLY get hormones from friends, online, or other non-licensed sources” were coded as NPHs only.

Healthcare policy stigma

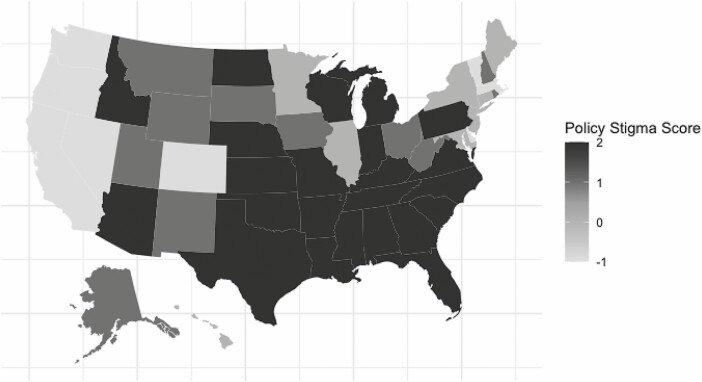

Healthcare policy stigma is a cumulative measure of the severity of policy-level factors that demean, devalue, and restrict the care of trans people. We created the state-specific healthcare policy stigma variable by tallying the total number of policies that were supportive of trans people and those that were unsupportive in 2015, the year data were collected. The policies underlying this composite are (a) private insurance protections for trans people, (b) whether or not Medicaid covers trans-specific healthcare, (c) state-wide nondiscrimination protections, and (d) religious exemption laws. This measure is adapted from Goldenberg et al.’s state-level trans-specific policies measure [12, 31]. These four policies were chosen because they are relevant to healthcare utilization in that they either stigmatize trans people, restrict access to healthcare services, or provide legal protections in healthcare settings. We gave supportive policies a score of minus one, while we gave unsupportive policies a score of plus one, while states that did not have an explicit policy were held unchanged. In total, the potential scores range from −2 to 2; however, the observed ranges for this variable in the data were −1 to 2. Higher scores indicate states with stigmatizing policies toward trans people. One point was subtracted from a state’s score if that state had private insurance nondiscrimination policies or if that state had a state-wide nondiscrimination policy. States were given one point if that state restricted trans healthcare for Medicaid populations or had any religious exemption laws. For a map of state-specific values for this variable, see Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Map of state-specific policy stigma values.

Mediators

Skipped care due to anticipated stigma was coded as a dichotomous variable (i.e., “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but did not because you thought you would be disrespected or mistreated as a trans person?”). Anyone who indicated “yes” to the question was coded as one, while those who indicated “no” were coded as zero. Uninsured was coded as a dichotomous variable, with those having no form of insurance (e.g., private insurance, Medicaid, and Medicare) being coded as one and those with any insurance being coded as zero. Skipped care due to cost was coded as a dichotomous variable (i.e., “Was there a time in the past 12 months when you needed to see a doctor but could not because of cost?”). Anyone who indicated “yes” to the question was coded as one, while those who indicated “no” were coded as zero.

Covariates

While reporting current gender identity, respondents chose one of six options: cross-dresser, woman, transgender woman, man, transgender man, or nonbinary/genderqueer. We excluded respondents who chose “cross-dresser” and created a three-level variable: (a) trans woman/woman; (b) trans man/man; and (c) gender nonbinary/genderqueer. Given the small number of persons of color (n = 2,063), the race was coded as a dichotomous variable for those who identify as “white” and those who identified as a person of color (i.e., 5% Hispanic, 5% Biracial, 3% Black, 2% Asian/Pacific Islander, and 1% Native American). While this approach is not ideal, the small cell sizes for NPHs use when cross-tabulated by race made it impossible to include the multi-category covariate. Age was collected and used as a continuous variable age in years at the time of data collection. Unemployment was coded as a dichotomous variable with those who were currently unemployed but looking for work being coded as one and all else being coded as zero. The Highest level of education was coded into four categories: less than high school, high school graduate, some college, and college graduate.

In addition to cost, lack of insurance, and anticipated stigma [9, 13, 27, 32], prior studies have also shown that NPHs use is correlated with lifetime sex work, experiencing homelessness, verbal or physical victimization, having a network of other trans people who use hormones, and family rejection [9, 13, 19, 27, 30, 33]. To control for these additional factors, we relied on measures collected by the USTS that mapped onto these constructs. Consistent with prior studies using this data source to examine medical gender affirmation [31], respondents were asked whether they had ever engaged in sex or sexual activity for money or worked in the sex industry, such as erotic dancing, webcam work, or porn films. Individuals who responded “yes” were coded as one for the variable sex work and zero if they responded “no.” The variable experiencing homelessness was coded as one for those respondents who reported experiencing homelessness in the past year and zero for those who reported “no.” Respondents reported whether they experienced physical or verbal abuse due to their gender identity in the past year. The variable physical or verbal abuse was coded as one for those who had reported experiencing either physical or verbal abuse due to their gender identity in the past year and zero for those who reported they did not experience either. Trans engagement was coded as one for those who reported socializing with trans people in person and zero for those who reported not socializing with trans people in person. Family support was coded into three categories: (a) those who are not out to their family, (b) those who reported their family was unsupportive of their gender identity, and (c) those who reported either not having a family, having a supportive family, or a family that was neither supportive nor unsupportive. Although there may be important differences in the third category of the family support variable, the sample sizes were too small to analyze these groups separately. Because a lack of family support and disclosure have both been associated with adverse outcomes, we coded this variable to examine differences between those with negative family experiences and those who were not out to their family and compared them participants with more neutral or positive family experiences [34].

To control for variation in NPHs use resulting from state-level and geographic factors other than healthcare policies, we included census region and Medicaid expansion as covariates. Census region was used to group states together by geographical location based on the taxonomy used by the Census that classifies states into either the Midwest, Northeast, South, or West. Although imperfect, we included the Census region as a control because states in similar regions tend to have similar political and social climates. Medicaid expansion was one provision of the Affordable Care Act aimed at reducing the uninsured rate. This statute allowed for states to opt into increasing the number of people eligible to receive Medicaid in exchange for more federal funding [35]. Medicaid expansion has been shown to significantly decrease the uninsured rates in states that have expanded Medicaid [35]. We controlled for Medicaid expansion using a categorical variable identifying whether a state had expanded Medicaid before the data were collected; states were coded as one if they expanded Medicaid and zero if they did not.

Statistical Analyses

We tested the conceptual model outlined in Fig. 1 (covariates are omitted to reduce clutter). The model was evaluated using the Mplus 8.0 software for structural equation modeling. The model was fit using robust (Huber-White) maximum likelihood algorithms. The uninsured skipped care due to cost, and skipped care due to anticipated stigma mediators are dichotomous and were estimated using a logit function. NPHs use was treated as a three-level nominal outcome that was regressed onto all variables, except Medicaid expansion, using a multinomial logit function with numerical integration. The referent group for the multinomial equation was those who only use NPHs. Multinomial equations yield coefficients that estimate local odds whereas our interest was with marginal probabilities for each of the three NPHs use categories. We used the methods described in Muthén, Muthén, and Asparouhov [36] to estimate the relevant marginal probabilities where all covariates were held constant at their respective mean values (i.e., we used a form of marginal effects analysis at the mean), but where the component probabilities of the marginal effects analysis at the mean were used to form relative risk ratios rather than probability differences using the MODEL CONSTRAINT command in Mplus.

The initial fit of the model revealed global ill-fit due to the need for correlated disturbances between skipping care due to trans stigma and the other two mediators. We, therefore, added parameters to the model to reflect these covariances. No other localized sources of model ill fit were noted. Missingness was not a major issue with these data. Missing data were treated using the default full information maximum likelihood methods in Mplus. Data were missing for the variables sex work (n = 9), skipped care due to anticipated stigma (n = 13), trans engagement (n =6), currently experiencing homelessness (n = 53), uninsured (n = 30), skipped care due to cost (n = 45), and family support (n = 22).

We report the results using profile analyses where we varied selected values on key predictors while holding all other variables constant at their mean values. The advantage of this approach is that it allows us to focus on probabilities and relative risk ratios, which are more interpretable and less misleading than odds ratios. The estimation algorithms do not permit the estimation of total effects from traditional structural equation modeling, so our focus was on contrasts between substantively meaningful predictor profiles.

Results

Table 1 presents unadjusted tabulations of demographics by hormone use. Among the respondents, 11,004 (92%) currently accessed hormones only from a licensed doctor (PHs use), 255 (2%) currently accessed hormones only from some other source (NPHs use), and 735 (6%) accessed hormones from both a licensed doctor and some other source (supplemental NPHs use). Without adjusting for covariates, on average, as age increased individuals were slightly more likely to use NPHs. Compared to white people, people of color were slightly more likely to use either supplemental NPHs or only NPHs. On average, those with higher levels of education were less likely to use either supplemental NPHs or only NPHs. Compared to trans women/women and nonbinary/genderqueer individuals, trans men/men were significantly less likely to use both supplemental NPHs and only NPHs. Table 2 reports the targeted predictor profile contrasts. We discuss each set of contrasts, in turn. To view the full results from the structural equation model, see the Online Supplement.

Table 1.

Respondent Demographics by Hormone Use

| PHs only (n = 11,004) | Supplemental NPHs (n = 735) | NPHs only (n = 255) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n or M | % or SD | n or M | % or SD | n or M | % or SD | Significance | |

| Age (in years) | 35 | 14 | 35 | 13 | 38 | 14 | F(2, 11,991) = 6.09; p = .002 |

| Race | |||||||

| White | 9,154 | 92% | 576 | 6% | 201 | 2% | x2(2) = 14; p = .001 |

| People of color | 1,850 | 90% | 159 | 8% | 54 | 3% | |

| Education | |||||||

| <High school | 95 | 89% | 6 | 6% | 6 | 6% | x2(6) = 23; p = .001 |

| High school graduate | 395 | 91% | 32 | 7% | 7 | 2% | |

| Some college | 1,746 | 94% | 80 | 4% | 27 | 1% | |

| BA+ | 671 | 95% | 24 | 3% | 8 | 1% | |

| Gender | |||||||

| Trans men/men | 4,710 | 97% | 145 | 3% | 18 | 0% | x2(4) = 275; p < .001 |

| Trans women/women | 5,411 | 88% | 508 | 8% | 209 | 3% | |

| Nonbinary/genderqueer | 883 | 89% | 82 | 8% | 28 | 3% | |

PHs prescribed Hormones; NPHs non-prescribed hormones.

Table 2.

Profile Analyses: Direct Effects

| Profile contrast | Profile 1 probability | Profile 2 probability | Relative risk | p values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: uninsured | ||||

| ME(no) vs. ME(yes) | 0.118 | 0.073 | .616 (.521, 712) | <.001 |

| PS(−1) vs. PS(2) | 0.044 | 0.079 | 1.802 (1.418, 2.186) | <.001 |

| Outcome: skip care due to cost | ||||

| Uninsured(no) vs. uninsured(yes) | 0.201 | 0.597 | 2.964 (2.669, 3.258) | <.001 |

| PS(−1) vs. PS(2) | 0.187 | 0.285 | 1.524 (1.361, 1.687) | <.001 |

| Outcome: skip care due to stigma | ||||

| PS(−1) vs. PS(2) | 0.108 | 0.147 | 1.357 (1.117, 1.596) | .004 |

| Outcome: PHs only | ||||

| Uninsured(no) vs. uninsured(yes) | 0.947 | 0.894 | .944 (.929, .959) | <.001 |

| Anti stig(no) vs. anti stig(yes) | 0.953 | 0.91 | .955 (.945, .965) | <.001 |

| Skip cost(no) vs. skip cost(yes) | 0.95 | 0.926 | .974 (.965, .983) | <.001 |

| PS(−1) vs. PS(2) | 0.941 | 0.947 | 1.007 (.995, 1.018) | .345 |

| Outcome: supplemental NPHs | ||||

| Uninsured(no) vs uninsured(yes) | 0.045 | 0.070 | 1.536 (1.271, 1.801) | .001 |

| Anti stig(no) vs. anti stig(yes) | 0.04 | 0.075 | 1.886 (1.621, 2.152) | <.001 |

| Skip cost(no) vs. skip cost(yes) | 0.041 | 0.065 | 1.565 (1.345, 1.785) | <.001 |

| PS(−1) vs. PS(2) | 0.053 | 0.042 | .797 (.628, .965) | .077 |

| Outcome: NPHs only | ||||

| Uninsured(no) vs. uninsured(yes) | 0.007 | 0.036 | 4.903 (3.751, 6.055) | <.001 |

| Anti stig(no) vs. anti stig(yes) | 0.007 | 0.014 | 2.002 (1.480, 2.524) | <.001 |

| Skip cost(no) vs. skip cost(yes) | 0.008 | 0.01 | 1.157 (.869, 1.445) | .352 |

| PS(−1) vs. PS(2) | 0.007 | 0.011 | 1.691 (1.019, 2.363) | .036 |

All other vars are mean centered. Estimates are from full multinomial models. Anti stig skipping care due to anticipated stigma; ME Medicaid expansion; NPHs non-prescribed hormones; PHs prescribed hormones; PS healthcare policy stigma; skip cost skipping care due to cost.

Predicting the Probability of Being Uninsured

On average, the uninsured rate was an estimated 4.5% lower in states that expanded Medicaid compared to those which did not (p < .001). On average, states with the lowest healthcare policy stigma score had an uninsured rate of 4.4% compared to those with the highest scores which had a rate of 7.9%. This is a difference of 3.5% and was statistically significant below p = .001.

Predicting the Probability of Skipping Care Due to Cost

On average and holding all other variables at their means, those who were uninsured were nearly three times more likely to skip care due to cost than those who were insured: 60% and 20% respectively (p < .001). On average, 19% of people skipped care due to cost in states with the lowest healthcare policy stigma scores compared to states with the highest scores where 29% skipped care due to cost (p <.001).

Predicting the Probability of Skipping Care Due to Stigma

On average and holding all other variables at their means, people in states with the lowest healthcare policy stigma score skipped care due to anticipated stigma at a rate of 10.8% compared to those in states with the highest score at a rate of 14.7%. Thus, those in the most stigmatizing states were nearly 1.4 times more likely to skip care due to anticipated stigma than their counterparts in states with the lowest stigma scores (p = .004)

Predicting the Probability of Using Only PHs

While continuing to look at the direct effect of the covariates and holding the other covariates at their means, we found that those who were uninsured were slightly less likely to only use PHs than their insured counterparts, 89% to 95% respectively (p < .001). We also found that those who skipped care due to anticipated stigma in healthcare settings were slightly less likely to only use PHs than their counterparts who did not skip care due to anticipated stigma: 91% to 95% respectively (p < .001). We found that those who skipped care due to cost were slightly less likely to only use PHs than their counterparts who did not, 93% to 95% respectively (p < .001). Lastly, we did not find that healthcare policy stigma had any significant direct effect on the probability of only using PHs.

Predicting the Probability of Supplemental NPH Use

We found that those who were uninsured were more likely to use supplemental NPHs than their insured counterparts: 7% to 5% respectively (p = .001). Those who skipped care due to anticipated stigma in healthcare settings were more likely to use supplemental NPHs than their counterparts who did not skip care due to anticipated stigma: 8% to 4% respectively (p < .001). Those who skipped care due to cost were more likely to use supplemental NPHs than their counterparts who did not: 7% to 4% respectively (p < .001). However, this did not reach statistical significance when analyzing local odds (p = .079); thus, the results should be interpreted with caution. Lastly, we found that healthcare policy stigma had a negative direct effect on the probability of supplemental NPHs, although statistical significance remained suspect (Relative Risk Ratio = .797, p = .077).

Predicting the Probability of Using Only NPHs

Those who were uninsured were more likely to only use NPHs than their insured counterparts: 4% to 0.7% respectively (p < .001). Those who skipped care due to anticipated stigma in healthcare settings were more likely to only use NPHs than their counterparts who did not skip care due to anticipated stigma: 1.4% to 0.7% respectively (p < .001). We did not find that those who skipped care due to cost were statistically more or less likely to only use NPHs than their counterparts who did not skip care due to cost. Lastly, we found a direct effect from healthcare policy stigma to only using NPHs. Those in states with the greatest healthcare policy stigma were more likely to only use NPHs than those in states with the least healthcare policy stigma: 1.1% to 0.7% respectively (p = .036).

Testing the Mediational Chains From Healthcare Policy Stigma to Hormone Use Type

The pattern of results for the profile analyses implies statistically significant mediation effects using the logic of joint significance tests as described in Fritz and MacKinnon [37]; Fritz et al. [38]. For example, given that healthcare policy stigma was statistically associated with an increase in the uninsured rate and being uninsured was, in turn, statistically associated with an increase in supplemental NPHs use and only using NPHs, under the property of the joint significance test, healthcare policy stigma was associated with an increase in using supplemental NPHs and only using NPHs as operating through insurance coverage. Similarly, given that healthcare policy stigma was statistically associated with an increase in skipping care due to anticipating stigma and skipping care due to anticipating stigma was statistically associated with an increase in supplemental NPH use and only using NPHs, under the property of the joint significance test, healthcare policy stigma was associated with an increase in using supplemental NPHs and only using NPHs as operating through anticipated stigma. Lastly, given that healthcare policy stigma was statistically associated with an increase of skipping care due to cost and skipping care due to cost was statistically associated with an increase in supplemental NPHs use, under the property of the joint significance test, healthcare policy stigma was associated with an increase in using supplemental NPHs as operating through anticipated stigma. Again, this last mediational chain was not statistically significant when analyzing local odds (p = .079). The pathway from healthcare policy stigma to using only NPHs was not significant.

Table 3 reports the predicted probabilities for the cumulative effect of the best versus the worst outcomes from the full multinomial model using profile analyses. The probabilities for the best-case group is the estimated probability of PHs use only, supplemental NPHs use, and NPHs use only when the control variables are mean-centered and the pathway variables are set to their most favorable values (e.g., uninsured, skipping care due to stigma, and skipping care due to cost are all equal to 0; Medicaid expansion is set to 1, and healthcare policy stigma is set to −1). The probabilities for the worst-case group are the estimated probability of using PHs only, supplemental NPHs use, and NPHs use only when the control variables are mean-centered and the pathway variables are set to their least favorable values (e.g., reverse-scored values from above).

Table 3.

Profile Analyses: Best- Versus Worst-Case

| Profile contrast | Best-case probability | Worst-case probability | Relative risk | p values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome: uninsured | ||||

| 0.038 | 0.117 | 3.10 (2.504, 3.696) | <.001 | |

| Outcome: skip care due to cost | ||||

| 0.162 | 0.663 | 4.093 (3.622, 4.564) | <.001 | |

| Outcome: skip care due to stigma | ||||

| 0.108 | 0.147 | 1.357 (1.117, 1.596) | <.001 | |

| Outcome: PHs only | ||||

| 0.958 | 0.793 | .827 (.793, .862) | <.001 | |

| Outcome: Supplemental NPHs | ||||

| 0.037 | 0.126 | 3.381 (2.439, 4.324) | <.001 | |

| Outcome: NPHs only | ||||

| 0.005 | 0.081 | 17.965 (9.084, 26.847) | <.001 |

All other vars are mean centered. Estimates are from full multinomial models. PHs prescribed hormones; NPHs non-prescribed hormones.

We found that the best-case probabilities were positively associated with desired outcomes and negatively associated with undesirable outcomes. Of particular note, compared to the best-case scenario, the worst-case scenario showed an 18-fold increase in the probability of using NPHs only (0.5% to 8%) and a 3-fold increase in using supplemental NPHs (4% to 13%). Each of these findings was statistically significant below a p value of .001.

Discussion

Our findings are consistent with other studies that demonstrate that structural stigma, specifically healthcare policies, is associated with medical gender affirmation practices of trans people in the USA [4, 31]. Our study extends the existing literature on NPHs use by positing and testing a conceptual model for NPHs use that accounts for the interplay of structural and individual stigma [10]. We show that healthcare policy stigma is associated with NPHs use and operates, in part, through avoiding healthcare due to stigma and cost, as well as insurance coverage in a sample of adults accessing hormones in the USA. We found that NPHs use should be treated as, at least, a three-category variable: PHs use, supplemental NPHs use, and NPHs use. Given our findings, the field would benefit from research that focuses on the distinctions between those who use only NPHs and those who use supplemental NPHs to understand how healthcare policy stigma contributes to adverse health outcomes among trans people in the USA.

Our analyses support our conceptual framework that healthcare policy stigma is positively associated with NPHs use and operates, in part, through insurance coverage and anticipated trans stigma. Compared to trans people accessing hormones in states with higher healthcare policy stigma, those in states with less healthcare policy stigma had a lower likelihood of using NPHs. Furthermore, our analyses partly confirm our second hypothesis, that skipping care due to cost and anticipated stigma would mediate the association between healthcare policy stigma and NPHs use. However, we found that skipping care due to cost was only associated with supplemental NPHs use and not significantly associated with using only NPHs. While seemingly counter-intuitive, this may be because people are prioritizing trans-related care over other forms of healthcare and thus the relationship between insurance remains while the effect for skipping care due to costs is diminished. However, future research is warranted to better understand these associations. While the rate of using either supplemental NPHs or only NPHs in this sample is small, our best-case versus worst-case analyses show just how sensitive these figures are to the main variables in our conceptual model. The rate of those using only NPHs increases as much as 18-fold when comparing the best-case to the worst-case. Thus, the variables outlined in our conceptual model are appropriate when predicting NPHs use and should be considered in further research.

Prior literature has treated NPHs use as a dichotomous phenomenon (e.g., any NPHs use vs. none). Notably, we found different direct associations between our structural variables, insurance coverage and healthcare policy stigma, and using only NPHs and using supplemental NPHs. Treating NPHs use as a dichotomous phenomenon, therefore, masks important conceptual differences as to why individuals might only use NPHs or supplement their PHs with NPHs. For example, we find that being uninsured increased the likelihood a person would use only NPHs nearly 500%, but increased supplemental NPH use by only 50%. This finding suggests that insurance coverage plays a larger role for those who only use NPHs than those who supplement their PHs with NPHs.

Consistent with prior research, we found that trans women were at a higher risk of NPU compared to other groups [9], which may be due to limited access to insurance and engagement in care [7]. Those who use supplemental NPHs are engaged in traditional healthcare systems which often require insurance coverage, while those who only use NPHs may be less likely to engage in care due to their uninsured status. Furthermore, we found a significant direct effect from healthcare policy stigma to using only NPHs, but not using supplemental NPHs. While this finding suggests we adequately accounted for the pathways from healthcare policy stigma to supplemental NPHs use, it also suggests that our conceptual model does not account for all possible mediators between healthcare policy stigma and using only NPHs. One mediator that may be relevant to understanding the effect of healthcare policies on the use of NPHs use is access to PHs. While the USTS does not specifically assess factors associated with accessing PHs, such as the ability to access a pharmacy, others have documented inconsistent access to trans-competent pharmacological care amongst trans individuals that may be influential in understanding NPHs use [39]. Exploring potential mediators between healthcare policy stigma and using only NPHs may prove an important topic for future research. Mixed-methods research may be particularly useful in exploring potential mediators (e.g., interpersonal interactions and intrapersonal factors such as cognitions, preferences, and behaviors) that might be driving the use of NPHs only as opposed to supplemental NPHs use.

A notable finding we had not hypothesized was how the association between healthcare policy stigma and the probability of being uninsured would compare to that of Medicaid expansion. Remarkably, compared to states with the most healthcare policy stigma, states with the least healthcare policy stigma have a lower predicted uninsured rate of 3.5%; while states that have passed Medicaid expansion have a lower predicted uninsured rate of 4.5%. This finding suggests that trans-specific healthcare policies are nearly as influential at insuring trans people than gender-blind policies like Medicaid expansion. Our findings suggest healthcare systems, including state policies, that are not explicitly designed to protect trans people (e.g., do not cover gender-affirming care or protect from discrimination and victimization) may result in avoidance of care or trans people may be shut out from participation. This finding supports prior research by Glick et al. [13] that trans people often go outside of mainstream healthcare services for their care, like accessing hormones from non-licensed sources, if they are not supported by mainstream institutions.

Notably, we found that nonbinary adults were at higher risk for NPHs use compared to trans men and trans women. It is plausible that nonbinary individuals may turn to NPH because the current World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) Standards of Care may be too restrictive and reinforce normative binary conceptualizations of gender conceptualization of gender identity and expression [40]. WPATH’s Standards of Care are currently being updated to be more inclusive of nonbinary patients [41]. It is also plausible that providers may not have knowledge or competency regarding proper care for nonbinary people, which may reinforce binary conceptualizations of gender [42]. These findings suggest future research is warranted to better understand NPHs use among nonbinary individuals to help inform clinical practice and training.

Existing studies suggest the need for policies that protect trans people from discrimination in healthcare settings given the evidence that discrimination against trans people in healthcare settings is related to adverse physical and mental health outcomes [43]. Our research builds on this work to demonstrate the importance of trans-specific public policy to not only addressing NPHs use but also to insuring trans people. In June 2020, the Department of Health and Human Services finalized a rule that removed existing protections from healthcare discrimination for an estimated 1.4 million trans adults [44, 45]. This rule allows healthcare facilities, insurers, and providers to deny care to trans people simply because of their gender identity [45].

Our findings suggest that it is plausible a lack of trans-inclusive healthcare policies may increase the number of trans people who are uninsured, skip care due to stigma and cost, and who use NPHs. Trans-inclusive policies that guarantee adequate access to safe, effective hormones are crucial to ensuring health equity for trans people. While documenting the potential effects of harmful policies is an important step, it is by no means the last. Public health practitioners must work to create interventions that meaningfully reduce structural stigma and build political coalitions to enact policies that protect trans people.

Beyond practical implications, this study also suggests a few implications for researchers working with categorical variables and cross-sectional data. Chiefly, our findings highlight the importance of thinking critically about how to operationalize categorical variables. Researchers ought to carefully examine their categorical variables and exhaust combinations relevant to their research topic. Our analyses also showcase the ability to conduct preliminary mediational research in a cross-sectional setting. While we are unable to “prove” causality in this study due to its cross-sectional nature, we were able to test whether our conceptual model is plausible given our data. This is an important first step in examining our conceptual model and testing our hypotheses, especially in situations where it is unethical to conduct cause-probing studies (e.g., randomized control trials). In this way, cross-sectional mediational analyses allow for testing the plausibility of mediational models without the unethical methods required to “proving” them.

Limitations

These findings should be interpreted within the context of the following limitations. The USTS is a convenience sample, which limits generalizability. The study also relies on self-reported data of sensitive topics (e.g., NPHs use, sex work) such that there may be social desirability bias. Furthermore, there is reason to believe the number of people reporting NPHs use and being insured may be smaller in our sample than in the overall population given that the study recruited some participants via medical centers; thus, these individuals may be actively engaging in mainstream healthcare settings. Furthermore, the USTS sample is predominantly non-Hispanic white, which made it impossible to conduct analyses on specific racial and ethnic categories. The small number of people of color also limited our ability to conduct interaction analyses between race/ethnicity and gender identity groups. When predicting the probability of supplemental NPHs use, some have shown that body satisfaction, or how happy a person is with their physical body, may be a key indicator of supplemental NPHs use [46]. Our inability to control for individuals’ body satisfaction maybe masking differences or acting as a confounder in our analyses. Future research should consider other risk factors for those who use supplemental NPHs: this is particularly important given that, at least in this sample, more individuals use supplemental NPHs than rely on NPHs alone. Logistic and multinomial logistic modeling have limitations in that the estimated effects are dependent on values of the covariates given the nonlinear nature of the modeling [47]. The generalizability of the results must therefore be viewed cautiously. Additionally, formal mediational and total effects analysis is difficult with nominal outcomes and dichotomous mediators. Future research would benefit from developing continuous measures of these constructs for use in more traditional structural equation models, such as how often a participant uses NPHs. Lastly, as the data are cross-sectional, causality cannot be determined from this study.

Conclusions

These findings demonstrate a pathway from healthcare policy stigma to NPHs use, with more inclusive policies being protective against NPHs use. We found that this association is partially mediated by insurance coverage, skipping care due to anticipated stigma, and skipping care due to cost. However, our research also demonstrates that these mediational factors vary in importance when predicting supplemental NPHs use versus predicting NPHs use only. This highlights the importance of tailoring interventions to address the specific needs of trans people who are using NPHs. For example, interventions that focus on those using supplemental NPHs may be best served by focusing on anticipated stigma, while interventions focusing on those who only use NPHs need to consider how being uninsured limits one’s ability to access PHs. Due to these kinds of differences, our work stresses the importance of treating NPHs use as at least three categories: PHs use only, supplemental NPHs use, and NPHs use only.

Our findings also demonstrate the importance of trans-inclusive policies and insurance coverage among trans populations. We found that stigmatizing policies were associated with an increase in the likelihood of trans people being uninsured. This suggests that to lower the uninsured rates of trans people, states cannot simply enact gender-blind policies aimed at insuring entire populations, such as Medicaid expansion, but must also consider trans-specific protections. Finally, this study also connects individual-level forms of stigma, such as avoiding healthcare services due to fear of discrimination, with structural forms of stigma, such as states’ healthcare policy environments. Policies that stigmatize trans people are highly associated with how trans people navigate healthcare; the more stigmatizing a state’s policies are, the more likely trans people may be to go without the care they need. In this way, policies “get under the skin” because they may lead people to use NPHs, which can have serious consequences for their health. Future research using longitudinal designs must consider the limits of trans individuals’ health behaviors in the presence of pernicious forms of structural stigma, such as stigmatizing healthcare policies, that constrain their ability to access safe hormones.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Landon Hughes was supported by the Rackham Merit Fellowship, the National Institute on Aging (T32 AG000221), and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Development (T32 HD00733931). We thank the U.S. Trans Survey (USTS) team and all of the individuals who participated in the study.

Contributor Information

Landon D Hughes, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Kristi E Gamarel, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Wesley M King, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Tamar Goldenberg, Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, USA.

James Jaccard, Silver School of Social Work, New York University, New York, NY, USA.

Arline T Geronimus, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, USA; Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, USA.

Compliance With Ethical Standards

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Authors Landon D. Hughes, Kristi E. Gamarel, Wesley M. King, Tamar Goldenberg, James Jaccard, and Arline T. Geronimus declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

References

- 1. Sevelius JM. Gender affirmation: a framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles. 2013;68:675–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Reisner SL, Radix A, Deutsch MB. Integrated and gender-affirming transgender clinical care and research. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(suppl 3):S235–S242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. King WM, Gamarel KE. A scoping review examining social and legal gender affirmation and health among transgender populations. Transgend Health. 2020:6(1):5–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. White Hughto JM, Reisner SL. A systematic review of the effects of hormone therapy on psychological functioning and quality of life in transgender individuals. Transgend Health. 2016;1:21–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Keo-Meier C, Fitzgerald KM, Pardo ST, Babcock J. The effects of hormonal gender affirmation treatment on mental health in female-to-male transsexuals. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2011;15:281–299. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Murad MH, Elamin MB, Garcia MZ, et al. Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72:214–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wilson EC, Chen YH, Arayasirikul S, Wenzel C, Raymond HF. Connecting the dots: examining transgender women’s utilization of transition-related medical care and associations with mental health, substance use, and HIV. J Urban Health. 2015;92:182–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L, Anaf M.. The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Clark K, Fletcher JB, Holloway IW, Reback CJ. Structural inequities and social networks impact hormone use and misuse among transgender women in Los Angeles County. Arch Sex Behav. 2018;47:953–962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: a critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:222–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. White Hughto JM, Rose AJ, Pachankis JE, Reisner SL. Barriers to gender transition-related healthcare: identifying underserved transgender adults in Massachusetts. Transgend Health. 2017;2:107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Goldenberg T, Reisner SL, Harper GW, Gamarel KE, Stephenson R. State‐level transgender‐specific policies, race/ethnicity, and use of medical gender affirmation services among transgender and other gender‐diverse people in the United States. Milbank Q. 2020;98(3):802–846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Glick JL, Andrinopoulos KM, Theall KP, Kendall C. “Tiptoeing around the system”: alternative healthcare navigation among gender minorities in New Orleans. Transgend Health. 2018;3:118–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Meriggiola MC, Gava G. Endocrine care of transpeople part II. A review of cross-sex hormonal treatments, outcomes and adverse effects in transwomen. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2015;83:607–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Moore E, Wisniewski A, Dobs A. Endocrine treatment of transsexual people: a review of treatment regimens, outcomes, and adverse effects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3467–3473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Streed CG Jr, Harfouch O, Marvel F, Blumenthal RS, Martin SS, Mukherjee M. Cardiovascular disease among transgender adults receiving hormone therapy: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;167:256–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Martinez C, Rikhi R, Haque T, et al. Gender identity, hormone therapy, and cardiovascular disease risk. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2018;45(5):100396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Asscheman H, T’Sjoen G, Lemaire A, et al. Venous thrombo-embolism as a complication of cross-sex hormone treatment of male-to-female transsexual subjects: a review. Andrologia. 2014;46:791–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:713–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Perez-Brumer A, Hatzenbuehler ML, Oldenburg CE, Bockting W. Individual- and structural-level risk factors for suicide attempts among transgender adults. Behav Med. 2015;41:164–171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Testa RJ, Habarth J, Peta J, Balsam K, Bockting W. Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2015;2:65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:813–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. West C, Zimmerman DH. Doing gender. Gend Soc. 1987;1:125–151. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Prof Psychol Res Pract. 2012;43:460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Bakko M, Kattari SK. Transgender-related insurance denials as barriers to transgender healthcare: differences in experience by insurance type. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35:1693–1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Perone AK. Protecting health care for transgender older adults amidst a backlash of U.S. federal policies. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2020;63:743–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rotondi NK, Bauer GR, Scanlon K, Kaay M, Travers R, Travers A. Nonprescribed hormone use and self-performed surgeries: “do-it-yourself” transitions in transgender communities in Ontario, Canada. Am J Public Health. 2013;103: 1830–1836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Du Bois SN, Yoder W, Guy AA, Manser K, Ramos S. Examining associations between state-level transgender policies and transgender health. Transgend Health. 2018;3:220–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gleason HA, Livingston NA, Peters MM, Oost KM, Reely E, Cochran BN. Effects of state nondiscrimination laws on transgender and gender-nonconforming individuals’ perceived community stigma and mental health. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2016;20:350–362. [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Haan G, Santos GM, Arayasirikul S, Raymond HF. Non-prescribed hormone use and barriers to care for transgender women in San Francisco. LGBT Health. 2015;2:313–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goldenberg T, Reisner SL, Harper GW, Gamarel KE, Stephenson R. State policies and healthcare use among transgender people in the U.S. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59:247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stroumsa D, Crissman HP, Dalton VK, Kolenic G, Richardson CR. Insurance coverage and use of hormones among transgender respondents to a national survey. Ann Fam Med. 2020;18:528–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Van Schuylenbergh J, Motmans J, Defreyne J, Somers A, T’Sjoen G. Sexual health, transition-related risk behavior and need for health care among transgender sex workers. Int J Transgend. 2019;20:388–402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gamarel KE, Watson RJ, Mouzoon R, Wheldon CW, Fish JN, Fleischer NL. Family rejection and cigarette smoking among sexual and gender minority adolescents in the USA. Int J Behav Med. 2020;27:179–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Courtemanche C, Marton J, Ukert B, Yelowitz A, Zapata D. Early impacts of the Affordable Care Act on health insurance coverage in Medicaid expansion and non-expansion states: impacts of the Affordable Care Act. J Pol Anal Manage. 2017;36:178–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Muthén B, Muthén L, Asparouhov T. Categorical dependent variable. In: Regression and Mediation Analysis Using Mplus. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fritz MS, Mackinnon DP. Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychol Sci. 2007;18:233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fritz MS, Taylor AB, Mackinnon DP. Explanation of two anomalous results in statistical mediation analysis. Multivariate Behav Res. 2012;47:61–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lewis NJW, Batra P, Misiolek BA, Rockafellow S, Tupper C. Transgender/gender nonconforming adults’ worries and coping actions related to discrimination: Relevance to pharmacist care. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76:512–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Castañeda C. Developing gender: the medical treatment of transgender young people. Soc Sci Med. 2015;143:262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Radix A. Standards of Care Version 8 Update. Boston, MA: Fenway Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Korpaisarn S, Safer JD. Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers: a major barrier to care for transgender persons. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2018;19:271–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reisner SL, Hughto JM, Dunham EE, et al. Legal protections in public accommodations settings: a critical public health issue for transgender and gender-nonconforming people. Milbank Q. 2015;93:484–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ, Brown TNT.. How Many Adults Identify as Transgender in the United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Janssen A, Voss R, Written on behalf of the Gender Development Program at the Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. Policies sanctioning discrimination against transgender patients flout scientific evidence and threaten health and safety. Transgend Health. 2020;1:61–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Radix AE, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Gamarel KE. Satisfaction and healthcare utilization of transgender and gender non-conforming individuals in NYC: a community-based participatory study. LGBT Health. 2014;1:302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Norton EC, Dowd BE, Maciejewski ML. Odds ratios—current best practice and use. JAMA. 2018;320:84–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.