Abstract

Objective

We investigated the educational value of implementing a web‐based e‐learning program into a medical student emergency medicine rotation. We created “UltrasoundBox,” a browser‐based application where students interpret ultrasound (US) images. Our goal was to assess how this form of e‐learning performs when compared to more passive, lecture‐based online US education. We also assessed the how the students interpreted the addition this learning modality to the rotation.

Methods

This is a randomized, controlled study to assess the educational outcomes of implementing UltrasoundBox compared to lecture‐based US education. Fourth‐year medical students on their emergency medicine rotation were enrolled in the study. Students randomized to the control arm were instructed to watch widely available educational lecture videos. Students randomized to the intervention arm received access to UltrasoundBox and were instructed to complete the clinical modules. Both groups completed the same standardized US examination before and after the trial. All the trial participants were given a survey to complete after the trial.

Results

We enrolled 42 students, with 23 in the control group and 19 in the intervention group. On the post‐intervention examination, the control and intervention groups were found to have mean examination scores of 61.6% and 73.6% respectively, with a statistically significant difference of 12% (95% confidence interval 1.611 to 5.56; p < 0.0005). A total of 92% of survey respondents in the intervention group indicated that UltrasoundBox was an effective tool in meeting the intended learning objectives, while only 36.8% of the control group indicated this for the online lectures (p < 0.005).

Conclusions

We found that medical students using the web‐based e‐learning platform UltrasoundBox achieved better scores on the examination when compared to the medical students using existing online lecture‐based US educational resources. The students reported that the addition of UltrasoundBox added educational value to the rotation.

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasound (US) is an effective means of enhancing medical student education. US has been found to enhance the learning of core topics such as physiology and anatomy. 1 , 2 , 3 There has been an overall positive reception of its implementation. 4 , 5 As such, US implementation into undergraduate medical education has gone from an elective niche to mainstream adoption into medical school curricula nationwide. Yet, despite widespread agreement on the educational benefit, actual creation and implementation of US curricula into undergraduate medical education has been inconsistent. 6 Results from the American Institute of Ultrasound in Medicine indicate that only 66 of 222 Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)‐accredited schools have any structured US instruction, with only 25 of them having a 4‐year curriculum. 7 The most significant barriers to implementation include lack of time and financial support. 6 Implementing an US curriculum requires significant investment into equipment, infrastructure, and consistent trained faculty time to spend with the learners.

E‐learning platforms offer a solution to the barriers. The benefits of such a platform have already been described previously to improve education and increase accessibility to education in a cost‐effective manner. 8 , 9 , 10 However, empiric evidence to guide how these tools can be implemented alongside existing educational methods for US education is lacking. To that end, we created and implemented the use of the e‐learning platform UltrasoundBox into an existing emergency medicine rotation and assessed its educational impact. 11

UltrasoundBox is a browser‐based, interactive, e‐learning platform that teaches US. We developed this tool to teach medical students the ability to interpret and clinically integrate US images and clips. It is different from many existing e‐learning platforms in that it requires learners to actively work through clinical cases. Active learning techniques help improve knowledge retention and create a better understanding of the content. 12 This is distinct from e‐learning platforms that use online lectures, which learners passively watch.

To assess this form of e‐learning platform’s impact on educational outcomes, we conducted a randomized controlled trial using a traditional teaching method as the control. Our goal was to assess how UltrasoundBox performs when compared to the currently widely available, online, lecture‐based US educational resources in teaching medical students point‐of‐care US. Our primary outcome was to see if the intervention group performed better on a posttrial examination. Our secondary goal was to assess if the students’ reception of this tool in their regular curriculum was better than the control.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This is a prospective, randomized controlled trial. The participants were medical students from various different medical schools on their emergency medicine rotation at an urban teaching hospital in New York City. All students on the rotation between the months of July 2021 to October 2021 were offered to participate in the trial on the first day of their rotation. We had calculated a priori that with a power of 80% and two‐sided alpha of 5% that we would need n = 54 with 27 students in each group to detect an effect size of 79%. Based on an average of 12–16 students rotating during 4 weeks in previous years, we had estimated that we would be able to enroll 60 students between July and October.

The emergency medicine rotation is 4 weeks long. All the students received an introduction to US lecture along with 1–2 h of hands‐on scanning time in the applications of echocardiogram (ECHO), extended focused assessment with sonography in trauma (eFAST), and biliary on the first day of their rotation. Otherwise, they received no additional specific US education during the rotation. If they consented, they were randomized into either the control group or the intervention group. The control group was asked to watch widely available US educational videos produced by the Academy of Emergency Ultrasound (AEUS) covering the topics of renal, ECHO, eFAST, and biliary. 13 The total runtime of the videos is approximately 2 h. The content covered by the videos is the same as that covered by the cases on UltrasoundBox. The intervention group was asked to use UltrasoundBox and complete 100 cases. This consisted of 25 cases in topics of ECHO, renal, biliary, and eFAST. We had both groups take an US examination pre‐ and posttrial. The same examination was used pre‐ and posttrial for both groups.

The US examination used was developed internally at our hospital for the purpose of this trial. We created it by amalgamating the quizzes and examinations used in previous years for the emergency medicine residents at our teaching hospital. The test covered the topics of ECHO, renal, biliary, and eFAST. It had 30 questions, with 10 ECHO, eight eFAST, seven billiary, and five renal questions. All the questions were multiple choice. Most of the questions had associated images that required the examinee to interpret. There was no skill demonstration aspect of the test. The results of the examination were not factored into the rotation evaluation or grade.

UltrasoundBox is an online web application designed and developed by this author. 11 While using the program, students are presented with clinical cases. For each case, one or multiple US images and video clips are presented. The students are then asked to analyze these media to generate an interpretation of the images and then use their interpretation to answer one to three clinical questions in the context of the clinical scenario given in the case. Upon submitting their interpretation and answers, they are provided with an expert interpretation of the images and correct answers to the clinical questions, along with educational materials specific to that clinical case.

The randomization was performed using a randomization list generated before the rotation started using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS). Each month the medical student roster was listed in alphabetical order by last name and numbered 1 to 12. Each number corresponded to a preset randomization based on the list generated in SPSS. We entered the collected data into spreadsheet format and used a statistical software package (GraphPad Prism Version 9.3.1) to perform the statistical analysis. Unpaired two‐tailed t‐test was calculated between the intervention and control groups for both the pre‐ and the posttrial results. Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the survey responses of the intervention and control group for questions that both groups answered. Our hospital’s institutional review board determined that this study is exempt from review.

RESULTS

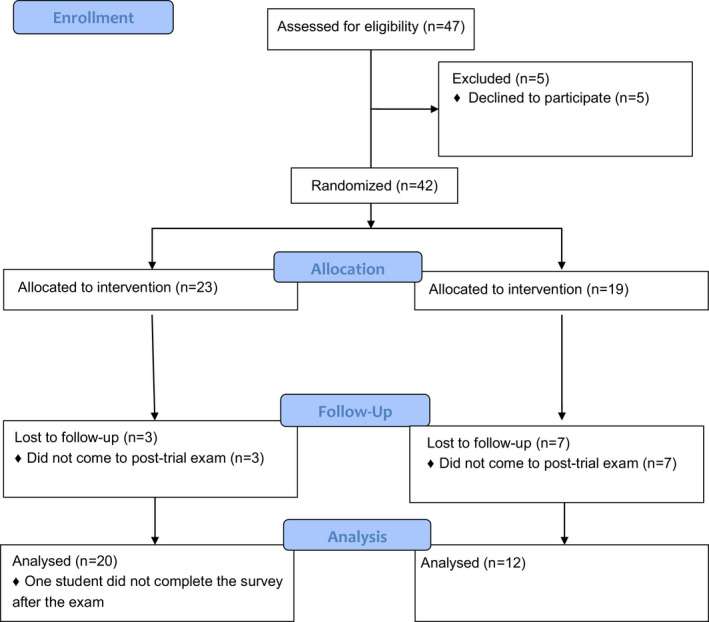

A total of 47 students eligible for this trial rotated in the emergency medicine department between the months of July and October 2021 (Figure 1). All the eligible students were fourth‐year medical students intending to apply or applied for residency in emergency medicine.

FIGURE 1.

Description of trial enrollment.

The mean examination score of the pretrial control group was 58.7%. The mean score of the pretrial intervention group was 61.93%. There was no statistically significant difference between the two pretrial groups (95% confidence interval [CI] –0.41 to 2.35; p = 0.1631). The posttrial mean examination score of the control group was 61.6%. The posttrial intervention group mean score was 73.6%, with a difference of 12% between the two posttrial groups, which was statistically significant (95% CI 1.611 to 5.56; p < 0.0005).

There was no statistically significant difference between the pre‐ and posttrial control groups (95% CI –0.49 to 2.277; p = 0.2012). The posttrial intervention group mean was higher than that of the pretrial intervention group (95% CI 1.536 to 5.473; p < 0.005).

Results of the survey questions that both groups answered are shown in Table 1. All 12 of the intervention group survey respondents indicated that they would recommend UltrasoundBox to a colleague as an effective training tool for point‐of‐care US. A total of 92% of survey respondents in the intervention group indicated that UltrasoundBox was an effective tool in meeting the intended learning objectives, while only 36.8% of the control group indicated this for the online lectures (p < 0.005). The intervention group spent an average of 174 min on the online platform during their rotation. They completed an average of 37.6 cases out of the 100 within the database (37.6%).

TABLE 1.

Survey results

| Sample characteristic | Group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention (n = 12) | Control (n = 19) | ||

| Q: Have you ever used an online question bank to supplement your medical education? |

Yes = 12 (100%) No = 0 (0%) |

Yes = 17 (89.5%) No = 2 (10.5%) |

p = 0.501 |

| Q: Do you agree with the statement that ultrasound is an important part of a medical student emergency medicine rotation? |

Strongly agree = 10 (83.3%) Agree = 1 (8.3%) Neutral = 0 (0%) Disagree = 0 (0%) Strongly disagree = 1 (8.3%) |

Strongly agree = 14 (73.7%) Agree = 4 (21.1%) Neutral = 0 (0%) Disagree = 0 (0%) Strongly disagree = 1 (5.3%) |

p = 1.0 |

| Q: What prior experience do you have with sonography? |

Significant experience = 1 (8.3%) Some experience = 0 (0%) Minimal experience = 9 (75%) None = 2 (16.6%) |

Significant experience = 2 (10.5%) Some experience = 2 (10.5%) Minimal experience = 13 (68.4%) None = 2 (10.5%) |

p = 1.0 |

| Agreement with effectiveness of modality to meet intended learning objectives |

Strongly agree = 3 (25%) Agree = 8 (66.6%) Neutral = 0 (0%) Disagree = 0 (0%) Strongly disagree = 1 (8.3%) |

Strongly agree = 2 (10.5%) Agree = 5 (26.3%) Neutral = 11 (58%) Disagree = 1 (5.26%) Strongly disagree = 0 (0%) |

p < 0.005 |

When the control group was asked if the time requirement to complete the videos was reasonable in the context of the rotation, 12 out of 19 indicated that it is. The total run time of the required videos was 116 min.

DISCUSSION

We found that the integration of UltrasoundBox into an existing emergency medicine rotation curriculum improved educational outcomes. The students in the intervention group had improved posttrial examination scores versus the students in the control group, who showed no educational improvement. Additionally, more students in the intervention group found UltrasoundBox to effectively teach US than in the control group. This indicates that the learners found UltrasoundBox to be an effective learning tool and agreed with its added educational value in the rotation, which is similar to surveys of medical students in previous studies for similar tools. 4 , 5 Moreover, we were able to create and implement the use of UltrasoundBox into an existing emergency medicine rotation at no financial cost. The average total time requirement to use UltrasoundBox was 174 min, which broken up over a 4‐week rotation is an average of 43.5 min per week. This was 58 min longer than that of the control group, or an additional 14.5 min per week during the rotation.

Owing to its nature of being a free e‐learning platform, it would take no additional financial resource to implement UltrasoundBox into any education setting worldwide. The ability to integrate additional US teaching into existing curricula with minimal resource requirements could help accelerate overall implementation of US education into undergraduate medical educational curricula. Moreover, similar resources are already heavily used by medical students on their own time, and they have no difficulty in adopting these resources into their education. For instance, all the students already had experience with other e‐learning platforms, with nearly every student having indicated on our survey that they had used Uworld during their studies.

Research on the effectiveness of e‐learning platforms, how they should be developed, and how they can be integrated into existing educational structures is currently lacking. Further studies should investigate whether these educational interventions influence the learner’s behavior and clinical knowledge in a sustained way and if there is a measurable improvement in patient outcomes in the clinical setting.

LIMITATIONS

The test we used to assess learning outcomes was created using our own existing emergency medicine resident examinations and was not validated prior to use in this trial, potentially limiting its generalizability. The questions, however, test core US topics that emergency medicine residents are expected to learn. The same examination was used for the pre‐ and posttrial assessment, potentially allowing for learning to occur due to retesting. However, the students were not told that the same examination was going to be administered after the rotation. Moreover, no improvement took place in the control group pre‐ and posttrial, indicating that no learning occurred from retesting. The students in the intervention group only completed an average of 37.6 cases out of the 100 assigned. It is possible that the potential effect size could have been larger had they completed more of the assigned cases. It is also unclear how many of the students in the control group watched all the assigned videos, as they did not perform any better on the posttest versus the pretest. As such, it is not possible to ascertain how much time the control group spent watching the videos. Yet, this also highlights the potential difficulty of trying to implement additional passive learning in the form of online videos into existing curricula. Lastly, 37% of the participants in the intervention group were lost to follow‐up and did not complete ethe examination or survey, potentially introducing selection bias.

CONCLUSIONS

We were able to integrate the e‐learning resource UltrasoundBox into an existing emergency medicine rotation with minimal additional resource utilization. Our study demonstrated that our e‐learning platform UltrasoundBox led to improved educational outcomes when compared to existing online educational resources.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no potential conflicts to disclose.

Perice L, Naraghi L, Likourezos A, Singh H, Haines L. Implementation of a novel digital ultrasound education tool into an emergency medicine rotation: UltrasoundBox. AEM Educ Train. 2022;6:e10765. doi: 10.1002/aet2.10765

Supervising Editor: Dr. Holly Caretta‐Weyer

REFERENCES

- 1. Hoppmann RA, Rao VV, Poston MB, et al. An integrated ultrasound curriculum (iUSC) for medical students: 4‐year experience. Crit Ultrasound J. 2011;3(1):1‐12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bahner DP, Royall NA. Advanced ultrasound training for fourth‐year medical students: a novel training program at The Ohio State University College of Medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88(2):206‐213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Knobe M, Münker R, Sellei RM, et al. Peer teaching: a randomised controlled trial using student‐teachers to teach musculoskeletal ultrasound. Med Educ. 2010;44(2):148‐155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hoppmann RA, Rao VV, Bell F, et al. The evolution of an integrated ultrasound curriculum (iUSC) for medical students: 9‐year experience. Crit Ultrasound J. 2015;7(1):18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Afonso N, Amponsah D, Yang J, et al. Adding new tools to the black bag–introduction of ultrasound into the physical diagnosis course. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(11):1248‐1252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bahner DP, Goldman E, Way D, Royall NA, Liu YT. The state of US education in U.S. medical schools: results of a national survey. Acad Med. 2014;89(12):1681‐1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Glass C, Sarwal A, Zavitz J, et al. Scoping review of implementing a longitudinal curriculum in undergraduate medical education: the Wake Forest experience. Ultrasound J. 2021;13(1):23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sinclair P, Kable A, Levett‐Jones T. The effectiveness of internet‐based e‐learning on clinician behavior and patient outcomes: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implem Rep. 2015;13(1):52‐64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cuca C, Scheiermann P, Hempel D, et al. Assessment of a new e‐learning system on thorax, trachea, and lung US. Emerg Med Int. 2013;2013:145361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Amesse LS, Callendar E, Pfaff‐Amesse T, Duke J, Herbert WNP. Evaluation of computer‐aided strategies for teaching medical students prenatal ultrasound diagnostic skills. Med Educ Online. 2008;13:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. UltrasoundBox. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://Ultrasoundbox.com

- 12. Wolff M, Wagner MJ, Poznanski S, Schiller J, Santen S. Not another boring lecture: engaging learners with active learning techniques. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(1):85‐93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. AEUS Narrated Lecture Series. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://www.saem.org/about‐saem/academies‐interest‐groups‐affiliates2/aeus/education/aeus‐narrated‐lecture‐series