Short abstract

This study provides an independent assessment of the breadth, scope, and impact of health services and primary care research funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs from FYs 2012 to 2018. The authors identify research gaps and offer recommendations for maximizing the outcomes and value of future investments in health services and primary care research by federal agencies.

Keywords: Biomedical Research, Health Care Program Evaluation, Health Care Quality, Primary Care

Abstract

This study presents the results of a congressionally mandated, independent assessment of federally funded health services research (HSR) and primary care research (PCR) spanning the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) from FYs 2012 to 2018. Through technical expert panels, stakeholder interviews, and a systematic environmental scan of research grants and contracts funded by HHS and the VA, the authors characterize the distinct contributions of agencies in these departments to the federal HSR and PCR enterprise. The authors also identify opportunities to improve detection and coordination of overlap in agency research portfolios, the impacts of HSR and PCR and how they cumulate across research portfolios, and gaps in research funding, methods, and dissemination. The authors offer recommendations to maximize the outcomes and value of future investments in federal HSR and PCR to better guide and serve the needs of a complex and rapidly changing U.S. health care system.

Background

On March 23, 2018, when H.R. 1625, the Consolidated Appropriations Act 2018, became law, Congress directed and authorized the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) to contract with an independent entity for a study on health services research (HSR) and primary care research (PCR) supported by federal agencies. AHRQ contracted with the RAND Corporation to conduct this study, beginning on September 19, 2018.

The goal of the study was to provide an independent assessment of the current breadth, scope, and impact of HSR and PCR supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ (HHS's) 11 operating divisions and the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) since fiscal year 2012. In support of this goal, the study was to identify research gaps and propose recommendations to AHRQ for maximizing the outcomes, value, and impact of HSR and PCR investments during the next five to 20 years and beyond, including strategies for better coordination and potential consolidation of research agendas.

The Need for This Study

The value of HSR has been well documented. Since its emergence as an independent field of study in the 1960s, HSR has helped establish an evidence base to support decisionmaking and improvements in the quality, safety, effectiveness, and efficiency of health care in the United States. HSR findings have been used to improve the design of health care benefits, inform health care policy, and help providers and patients make better decisions about health care.

PCR has also emerged as a distinct field in its own right, addressing a central component of the health care system. The Council of Academic Family Medicine and other organizations have identified key characteristics of primary care, which highlight the importance of PCR, including its ability to touch the lives of all Americans, focus on the whole person, give attention to common conditions often not treated in hospitals or specialty clinics, and provide evidence that is critical for the delivery of high-quality primary care (Wittenberg, undated).

Consistent with this broad acknowledgment of the many meaningful contributions of HSR and PCR to improving health care, there has been growing recognition of the need to better understand the impact of HSR and PCR and to prioritize potential future directions of research among federal agencies and other stakeholders. A 2018 conference on HSR sponsored by the National Academy of Medicine called for “a set of activities required to transform the field,” including an expanded vision of HSR, a taxonomy of issues and priorities for action, tools and insights to use in effecting change, the development of data infrastructure, and the creation of a “working network” of stakeholders—including patients—in research (National Academies of Medicine, 2018). Although there has been less investment in planning for the future of PCR, there is a growing recognition that primary care is “too important to fail” (Meyers and Clancy, 2009), and that planning for research that effectively supports the goals of primary care is critically important.

Research Questions

The current study attempts to build on the work done to date in examining future directions for HSR and PCR. Based on the goal of the study, the RAND team worked with AHRQ to develop a set of five key research questions:

What is the breadth and focus of federal agency research portfolios in HSR and PCR?

What is the overlap among federal agency research portfolios and the coordination that occurs between federally funded HSR and PCR?

What are the impacts of federally funded HSR and PCR and challenges to assessing and achieving impacts?

What are the gaps in federally funded HSR and PCR and approaches to prioritizing gaps?

What are options for improving the outcomes, value, and impact of future federally funded HSR and PCR?

To answer these questions, the RAND team formed two technical expert panels (TEPs) constituted of stakeholder leaders in the fields of HSR and PCR, conducted interviews with key informants from five stakeholder groups in HSR and PCR, and performed an environmental scan and portfolio analysis to enumerate and catalog federally funded HSR and PCR projects from October 1, 2011 through September 30, 2018.

Federal Agency Portfolios in HSR and PCR Have Distinct Focus Areas Based on Their Individual Congressional Authorizations, Missions, and Operational Needs

Study participants and federal agency points of contact identified eight agencies in the scope of the study with portfolios of research in HSR and PCR, according to the definitions of the study: the Administration for Community Living (ACL), AHRQ, the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

These agencies have developed research portfolios of HSR and PCR around focus areas that address the requirements of their individual congressional authorizations, missions, and operational needs. The agency portfolios differ along three key dimensions—scope of the health care system examined, research objectives, and research audiences—which reflect distinct agency emphases in HSR and PCR. For example, study participants from the range of stakeholders noted AHRQ as the only federal agency that has a statutory authorization to generate HSR and mission to do so across the U.S. health care system. It is also the agency authorized to serve as the home for federal PCR. Study participants further emphasized the unique focus of AHRQ's research portfolio on system-based outcomes (e.g., making health care safer, higher quality, more accessible, equitable, and affordable) and approaches to implementing improvements throughout health care settings and populations in the United States.

NIH's portfolio of HSR and PCR addresses a similarly broad scope of health care but tends to be organized around specific diseases, body systems, or populations. The CDC's portfolio of HSR and PCR is organized around diseases, conditions, and injuries, but focuses on prevention and health promotion spanning community and health care settings. The portfolios of other agencies tend to focus on specific health care settings or other populations (e.g., CMS on Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries, VHA on veterans’ health care and health, and ACL on community-living elderly and disabled individuals), or research audiences (e.g., ASPE on federal policymakers).

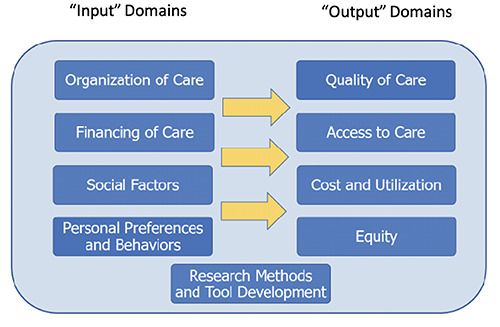

To differentiate the topical areas of focus within agency's HSR and PCR portfolios, the study team worked iteratively with AHRQ and the study's TEPs to develop the research domain framework shown in Figure 1. The framework includes four domains of health care “outputs” typically of interest to health care policymakers and other stakeholders, four domains of health care “inputs,” and a domain of research methods and tool development integral to the advancement of HSR and PCR and implementation of research evidence into practice.

Figure 1.

Research Domain Framework for HSR and PCR

Results of the environmental scan and portfolio analysis's systematic enumeration of HSR and PCR projects confirmed a number of these distinctive focus areas of agency research portfolios, including AHRQ's relative emphasis on Patient Safety, Health Information Technology (HIT) Applications and Tools, and Evidence Review and Synthesis; CMS on Cost and Utilization and on Financing of Care; CDC on Prevention; and ACL on Social Factors. At the same time, the scan results showed other agency portfolios to include projects in these areas, albeit to a lesser extent, as well as strong emphasis across all agencies on the research domains of Quality of Care and Organization of Care. While the qualitative results from TEP and interview participants indicated how agencies would be expected to approach these topics differently, the relatively broad categories of the scan analysis were not able to detect these distinctions. Thus, the study next addressed the question of the degree to which research funded by agencies in similar topic areas is complementary or redundant, and the extent and ways in which federal HSR and PCR funding is coordinated among agencies.

Agency-Funded HSR and PCR on Similar Topics Is Largely Complementary, but Potential Overlap in Portfolios Needs to Be Identified More Proactively

Study participants across various stakeholder groups noted that overlap in research funding— that is, when agencies fund research in the same topic area—is generally complementary and advantageous rather than redundant. Complementary research includes instances when agencies fund projects addressing different facets of a research topic, as well as when agencies devote or combine resources for similar projects on an underfunded topic in an additive fashion.

Several interview participants pointed to coordination of research portfolios as a more problematic issue than redundancy. Participants observed that agencies acted to address redundancy in research portfolios and worked to ensure that funding of the research reflected the distinct roles and added value of each agency after such redundancies were recognized. Participants also observed federal agencies to be adept at utilizing appropriate and effective mechanism for coordination—formal and informal—once overlaps in portfolios were recognized. Informal coordination mechanisms include personal staff connections and networks, which were also considered critical facilitators of formal coordination.

However, study participants commented on the lack of systematic processes for proactively identifying potential overlap in HSR and PCR portfolios across agencies. The process of discovering overlaps was said to be “sporadic,” “accidental,” or “anecdotal” and to occur “by happenstance.” Individual study participants also noted research areas they considered to lack sufficient coordination. Challenges to coordination of HSR and PCR portfolios mentioned by study participants included the breadth and volume of research activities across the federal HSR and PCR enterprise, differing time frames of research among agencies, and the lack of targeted funding for a lead agency to coordinate PCR in particular.

Federally Funded HSR and PCR Have Resulted in Wide-Ranging Impacts, Which Are Often Cumulative Across Agency Portfolios

Health services and primary care in the United States are complex, multilevel, and layered systems in which the process of change is not always well understood and effecting positive change often requires leveraging multiple strategies. Understanding how HSR and PCR can and have had impact on these systems is important for assessing the contributions of federally funded research to the fields of HSR and PCR and for informing the prioritization of research gaps.

Based on existing frameworks of research impact as well as discussions with TEP and interview participants, we identified six categories of impact, which we illustrate with examples of federally funded HSR and PCR: (1) scientific impact, (2) professional knowledge and practice impact, (3) health care systems and services impact, (4) policy impact, (5) patient impact, and (6) societal impact. It is unlikely for a single research project to generate impact across all categories, and the impacts of specific projects may not always occur in a linear order. However, the types of impacts identified represent a progression from interim research impacts (i.e., on scientific knowledge, professional practice, health care systems, and policy) to direct outcomes for patients and wider outcomes for society. As such, they represent a general guiding framework for assessing the accumulated impact of portfolios of research within an agency or that span agencies.

In addition to identifying types of impact, study participants noted important challenges to assessing impact, including the difficulty of tracing the accumulation of impacts across specific projects or sets of projects within a portfolio, especially when research is funded by multiple agencies. Impact may take time to accumulate and be realized, which further complicates attribution to specific projects or sources of funding. Moreover, many types of impact are by their nature difficult to systematically measure. Study participants also called attention to challenges in achieving HSR and PCR impact. These barriers included a lack of investment in high-risk studies and various disconnects between research and implementation.

The Variety of Gaps in HSR and PCR Reflect the Challenge of Improving U.S. Health Care, Which Requires New Research Approaches and Strategies for Prioritizing Research Needs

TEP and interview participants identified a wide range of pressing research gaps in HSR and PCR. These gaps are driven by the complexity and rapidly changing landscape of the U.S. health care system. Many of these gaps are related to specific “inputs” and “outputs” of health care services in the study's research domain framework (Figure 1). However, many of the gaps also reflect the difficulty of understanding the linkages between health care inputs and outputs to produce important outcomes, and the limitations of currently used research approaches to generate and disseminate evidence in ways that positively impact real-world health care systems and practice. At the same time, these gaps also represent opportunities to find new ways to use research to solve problems and improve the health care system, and ultimately the nation's collective health.

Our analysis highlighted key gaps, that is, research gaps that were raised by multiple study participants within a perspective or across stakeholder perspectives. Study participants noted that many of these gaps have been the subject of research studies sponsored by federal agencies and other funders, but that further research is needed, or different research approaches are required to make a positive impact on health care delivery and health outcomes.

Table 1 lists the key cross-cutting gaps in research approaches that impede the impact of HSR and PCR for improving real-world health care systems and practice.

Table 1.

Key Cross-Cutting Gaps in Research Approaches to HSR and PCR Identified by Study Participants

| Research Domain | Gaps in HSR and PCR |

|---|---|

| Cross-Cutting | Examining health care outcomes for a fuller range of populations and settings

Following change in implementation and outcomes of health care interventions over time Communicating results that are actionable by health care delivery stakeholders Producing relevant and timely results for health care delivery improvement Using theory to connect findings and advance knowledge on health care change Leveraging digital health and linking various new sources of health care–related data |

Table 2 summarizes the key research domain gaps raised by study participants for HSR.

Table 2.

Key HSR Gaps Identified by Study Participants

| Research Domain | Gaps in HSR on … |

|---|---|

| Organization of Care | Health care workforce needs, composition, and roles in new delivery models∗

Reducing burdens of health IT on health care providers∗ |

| Financing of Care | Effects of evolving models of financing on the range of health care outcomes

Effects of health care payment models on different patient populations |

| Social Factors | Role of health care systems in addressing social determinants of health∗

Effect of social factors on demand for health care services∗ |

| Personal Preferences and Behaviors | Integrating patient preferences into care∗

Addressing health and health care misinformation∗ |

| Quality of Care | Developing harmonized measures to meaningfully, accurately, and feasibly assess quality of care∗ |

| Access to Care | Identifying both root causes and evidence-based solutions for barriers to access∗ |

| Cost and Utilization | Challenge of lowering cost while improving care∗

Reducing waste in health care∗ Costs of new care therapies and delivery models∗ Reducing costs across the health care system |

| Equity | Solutions to reduce disparities in health care |

Similar gap included in key PCR gaps (Table 3).

Table 3 lists key research domain and cross-cutting gaps for PCR. The asterisk in Tables 2 and 3 denotes gaps that were similar for both HSR and for PCR, though often exhibiting distinct aspects.

Table 3.

Key PCR Gaps Identified Study Participants

| Research Domain | Gaps in PCR on … |

|---|---|

| Organization of Care | Health care workforce needs, composition, and roles in new delivery models for primary care∗

Reducing burdens of health IT on primary care providers∗ |

| Financing of Care | Effects of evolving models of financing on primary care delivery and outcomes∗

Effects of health care payment models on different patient populations∗ |

| Social Factors | Role of health care systems in addressing social determinants of health∗

Effect of social factors on demand for primary care services∗ |

| Personal Preferences and Behaviors | Integration of patient preferences in primary care∗

Addressing health and health care misinformation∗ |

| Quality of Care | Developing primary care–specific measures that capture quality in ways meaningful to patients and providers∗ |

| Access to Care | Identifying both root causes and evidence-based solutions for barriers to access∗ |

| Cost and Utilization | Challenge of lowering cost while improving care∗

Decreasing underutilization as well as overutilization in primary care∗ Costs of new delivery models for primary care (e.g., PCMH)∗ |

| Equity | Role of primary care in addressing equity |

| Cross-Cutting PCR Gaps | The core functions of primary care

Primary care transformation and role in the wider health care system |

Similar gap included in key HSR gaps (Table 2).

Study participants and Federal Advisory Group members emphasized the need to prioritize research gaps to effectively and efficiently allocate limited research funding. Criteria for prioritization mentioned included the potential impact of the research, the potential to address a gap in an underfunded research area, the potential to address foundational areas of research, and the timeliness of the research. Federal Advisory Group members also noted that, within federal agencies, an important criterion for prioritization is the alignment of an issue with the agency's mission, comparative advantage, and expertise in funding research on the topic.

Recommendations

The findings above document the distinct focus areas of federal agency HSR and PCR portfolios, which have been developed based on the agencies’ congressional authorizations, missions, and operational needs. They have also examined how agencies coordinate research funding on similar topics in complementary ways according to their distinct focus areas and expertise, and how federally funded HSR and PCR have had a wide range of impacts that are often cumulative across research portfolios. At the same time, the study has identified the need for federal agencies to more proactively recognize areas of potential overlap in research portfolios, to improve the communication, relevance, and timeliness of research results, and to prioritize the myriad gaps in research in order to keep pace with and guide the complex and rapidly changing U.S. health care system.

We propose three sets of recommendations to improve the impact of federally funded HSR and PCR based on our review of the key study results and suggestions of study participants:

Cross-cutting recommendations on approaches to research, dissemination, and implementation of federally funded HSR and PCR (Table 4)

Recommendations to improve the impact of HSR (Table 5)

Recommendations to improve the impact of PCR (Table 6).

Table 4.

Cross-Cutting Recommendations on Approaches to Research, Dissemination, and Implementation

| Recommendations | Suggested Action Steps |

|---|---|

| Improve the relevance and timeliness of HSR and PCR | Create funding mechanisms that support more rapid, engaged research approaches, such as embedded research and learning health systems models, and dissemination of their results.

Expand funding to refine mixed qualitative and quantitative methods suited to generating evidence on the implementation of change in complex health care systems. |

| Encourage innovation in HSR and PCR | Create funding mechanisms that support innovative high-risk, high-reward research. |

| Improve translation of HSR and PCR into practice | Train and assist researchers in effectively communicating results in formats actionable for health care delivery stakeholders.

Fund research to identify the most effective channels to communicate research results for different users of HSR and PCR. Require researchers to consider implementation issues earlier in the study development and proposal process and explicitly apply theories of change to help connect disparate results. Expand funding for the synthesis of evidence across research studies on topics of interest to health care delivery and other users of HSR and PCR. |

Table 5.

Recommendations to Improve Impact of HSR

| Recommendations | Suggested Action Steps |

|---|---|

| Identify HSR priorities for agencies to effectively allocate research funding | Initiate a strategic planning process across federal agencies to prioritize HSR areas for funding investments. |

| Proactively identify potential overlap in agency HSR portfolios | Establish a review process and data systems to proactively identify areas of potential HSR overlap across agencies. |

| Maintain a funded entity to address core HSR needs and coordinate federal HSR efforts | Maintain AHRQ as an independent agency within HHS to serve as the funded hub of federal HSR. |

Table 6.

Recommendations to Improve Impact of PCR

| Recommendations | Suggested Action Steps |

|---|---|

| Identify PCR priorities for agencies to effectively allocate research funding | Initiate a strategic planning process across federal agencies specifically dedicated to prioritizing PCR areas for funding investments. |

| Proactively identify potential overlap in agency PCR portfolios | Establish a review process to proactively identify areas of potential PCR overlap across agencies. |

| Fund an entity to address core primary care research needs and coordinate federal PCR efforts | Provide targeted funding for a hub for federal PCR. |

Our first set of recommendations in Table S.4 addresses three key gaps in research approaches for both HSR and PCR identified by study participants: (1) improve relevance and timeliness of research, (2) increase innovation in research, and (3) improve translation of research into practice. We suggest specific steps for each recommendation.

Our second set of recommendations in Table 5 focuses on improving the impact of federally funded HSR and addresses three key themes identified by study participants related to: (1) prioritization of the many ongoing and emergent research gaps in HSR, (2) coordination of federally funded HSR by proactively identifying potential overlap in agency research portfolios, and (3) alignment of federally funded HSR through continued support of AHRQ as an independent agency within HHS to serve as the funded hub of federal HSR.

Our third set of recommendations in Table 6 focuses on improving the impact of federally funded PCR. These recommendations also address key themes identified by study participants related to prioritization, coordination, and alignment of federal agency research portfolios, but attending to the distinct needs of the PCR field. First, a separate interagency prioritization process for PCR would ensure that core primary care research needs are attended to, incorporate the specific stakeholders needed to inform prioritization, and span clinical research as well as HSR. Second, a process to proactively identify potential overlap in federal agency PCR portfolios would focus on coordination of PCR to maximize the impact of the limited resources available for federally funded PCR and rely on staff from different agencies expert in federal PCR portfolios. Last, with respect to alignment of federal PCR efforts, we recommend providing funding for a hub of federal PCR that includes targeted funding for both research on core functions of primary and coordination of PCR across federal agency research portfolios.

Conclusion

This study has identified a number of important gaps in HSR and PCR, many of which are driven by the complexity and rapidly changing landscape of the U.S. health care system. As in the past, there is a great opportunity for federally funded HSR and PCR to have meaningful impact and guide understanding of new models of care delivery and payment, inform health care stakeholders on best practices for implementing specific health care innovations and interventions, and disseminate and promote health system change.

The study also has identified opportunities to improve approaches to research funding and methods to ensure that federally funded HSR and PCR can keep pace with and continue to guide change in health care delivery systems. Additionally, it has offered separate recommendations for HSR and PCR to improve the outcomes and value of federal research investments, including strategies for better prioritizing, coordinating, and aligning agency research portfolios. The results of the study provide a balanced, evidence-based understanding of federally funded HSR and PCR that policymakers can use in shaping the future of the federal HSR and PCR enterprise.

Notes

This research was funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and conducted by the Payment, Cost, and Coverage Program within RAND Health Care.

References

- Meyers D. S., and Clancy C. M. “Primary Care: Too Important to Fail,”. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009 February 17;Vol. 150(No. 4):272–273. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-4-200902170-00009. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whicher, Rosengren, Siddiqui, , and Simpson, , editors. National Academies of Medicine. The Future of Health Services Research: Advancing Health Systems Research and Practice in the United States. Washington, D.C.: National Academies of Medicine; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenberg Hope. Letter to Policymakers, Council of Academic Family Medicine. https://www.stfm.org/media/1664/cafm-primary-care-research-unique-role.pdf undated. As of November 13, 2018: