Short abstract

Suicide is a major public health challenge that disproportionately affects service members and veterans. Researchers have been studying veteran suicide rates and prevention strategies, but there are opportunities to improve risk identification, evaluation, support, and treatments and interventions. These strategies must include community-based efforts to reach veterans outside the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs system.

Keywords: Suicide, Veterans Health Care

Abstract

Suicide is a major public health challenge that disproportionately affects service members and veterans. Researchers have been studying veteran suicide rates and prevention strategies, but there are opportunities to improve risk identification, evaluation, support, and treatments and interventions. These strategies must include community-based efforts to reach veterans outside the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs system.

Suicide is a major public health issue and among the top ten causes of death in the United States. Unfortunately, for more than a decade, the suicide rate has been rising in the general U.S. population and especially among veterans, men and women who risked their lives for the country. This article presents data on the magnitude of the problem, identifies particularly noteworthy issues and trends, highlights recent advances, and identifies gaps that deserve increased attention from both researchers and policymakers. In its 2018–2024 strategic plan, the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) identified preventing veteran suicide as its highest clinical priority, and the RAND Epstein Family Veterans Policy Research Institute is committed to helping VA—and the country—achieve this critical goal.

Magnitude of the Problem

In 2018, 6,435 veterans and 40,075 nonveteran adults died by suicide. But because there are many more nonveterans in the population, the rate of suicide among veterans was 32.0 per 100,000, compared with 17.2 per 100,000 for nonveterans (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020b).

Trends over Time

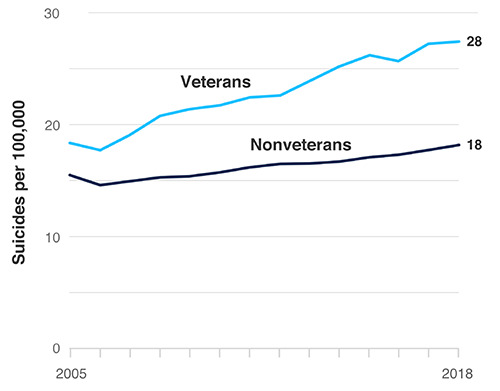

For the past 12 years, suicide rates have been consistently higher among veterans than nonveterans. Furthermore, since 2005, the suicide rate has risen faster among veterans than it has for nonveteran adults. Figure 1 shows age- and sex-adjusted rates over time (which are better for comparing between groups); as of 2019, adjusted rates of suicide were 27.5 per 100,000 for veterans and 18.2 per 100,000 for nonveterans (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020b).

Figure 1.

Age- and Sex-Adjusted Suicide Rates Among Veterans and Nonveterans, 2005–2018

SOURCE: Data from U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020b, data appendix.

Pressing Issues

The greatest difference in suicide rates between veterans and nonveterans is among those ages 18–34.

In 2018, the suicide rate among veterans 18–34 years old was 45.9 per 100,000—higher than in any other age group in either population and almost three times higher than for nonveterans in the same age bracket (16.5 per 100,000). This equated to 874 suicide deaths among veterans ages 18–34 (796 men and 78 women) in 2018.

The largest number of veterans who die by suicide are between 55 and 74 years old.

In 2018, 2,587 veterans ages 55–74 died by suicide, a rate of 30.4 per 100,000 (compared with 17.0 per 100,000 among nonveterans in the same age bracket).

The difference in suicide rates between veterans and nonveterans is greater among women than men, but for both veterans and nonveterans, rates are higher among men.

In 2018, the suicide rate for veteran women was 14.8 per 100,000 (291 deaths), almost twice the rate for nonveteran women (7.6 per 100,000). The difference was greatest among women ages 18–34 (veterans: 21.8; nonveterans: 6.8 per 100,000). That same year, the suicide rate among veteran men was 1.2 times the rate among nonveteran men (33.8 versus 29.0 per 100,000). For men, the difference was also greatest among 18- to 34-year-olds (veterans: 51.5; nonveterans: 26.4 per 100,000).

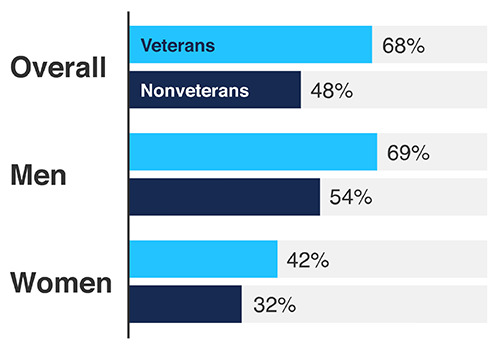

Veterans who die by suicide are more likely to use a firearm than civilians who die by suicide.

In 2018, 68.2 percent of veterans who died by suicide used a firearm, compared with 48.2 percent of nonveterans. Figure 2 shows these proportions overall and for men and women.

Figure 2.

Percentage of Veterans and Nonveterans Who Died by Suicide, Firearm Use, 2018

SOURCE: Data from U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020b, data appendix.

Veterans with mental health diagnoses have a significantly elevated suicide risk.

By many measures, the mental health care provided by VA through the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is higher-quality than the care available through private providers, and, in some areas, it might be improving (O'Hanlon et al., 2017; U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020b). However, the rate of suicide among VHA patients with a mental health or substance use disorder diagnosis was 57.2 per 100,000—more than double the rate among those without these diagnoses.

Specifically, suicide rates were highest among VHA patients diagnosed with opioid use disorder or bipolar disorder (both between 120 and 130 suicide deaths per 100,000), followed by schizophrenia and substance use disorders overall (both between 80 and 100 deaths per 100,000), anxiety (67 per 100,000), depression (66.4 per 100,000), and posttraumatic stress disorder (between 50 and 60 per 100,000). There is also evidence that veterans with traumatic brain injuries are at increased risk of suicide compared with those without these injuries (Hostetter et al., 2019).

There is mixed evidence about the role of combat exposure in suicide risk. In one study, among all service members who deployed from 2001 to 2007, deployment was not associated with increased suicide risk between 2001 and 2009 (Reger et al., 2015). However, among those who served in the active-duty Army between 2004 and 2009, suicide risk was elevated during active service for currently and previously deployed soldiers (Schoenbaum et al., 2014).

Data on Veteran Suicide

In 2012, VA and the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) collaborated to create the VA/DoD Mortality Data Repository. Each year, VA and DoD generate a list of all veterans, nonveteran VA patients (such as the eligible dependents of veterans), and active-duty military personnel, which is matched to the National Death Index maintained by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This produces a data set with causes of death for all veterans each year, regardless of their eligibility or use of VA benefits (Hoffmire et al., 2020).

Notable Advances in Research and Practice

The rate of veteran suicide, reflecting thousands of lives lost each year, warrants greater attention from VA, other federal agencies, state and local governments, and organizations that serve veterans. There have been some notable advances in research and practice that might help reduce suicide among veterans.

Emerging evidence suggests that screening and risk assessments for suicide can be lifesaving.

Screening all patients for suicide risk in mental health, emergency, and primary care settings can detect those who might be thinking about harming themselves, discern their current level of risk, and provide opportunities to offer appropriate care—ultimately reducing suicide attempts (Miller et al., 2017). Screening can be conducted efficiently using validated tools, such as the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) tool, across health care settings (Roaten et al., 2018; National Institute of Mental Health, undated; Thom, Hogan, and Hazen, 2020). As part of its National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide, VA developed Risk ID, a three-stage suicide screening process that has been implemented successfully in VA settings (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018; Bahraini et al., 2020).

VA's ReachVet program can identify veterans at risk of suicide who would have otherwise been missed.

VA's ReachVet program applies statistical algorithms to clinical data to produce a monthly list of veterans with the highest probability of dying by suicide (Reger et al., 2019). A coordinator at each VA facility receives the list of at-risk patients and alerts the veterans’ health care providers.

VA is expanding its Caring Contacts program based on promising evidence that such contacts can save lives.

Caring contacts are brief, personal, nondemanding follow-up messages sent to patients after they receive care. These messages have been linked to decreased suicide attempts (Motto and Bostrom, 2001). VA now sends follow-up letters to veterans who receive care at a VA facility or call the Veterans Crisis Line and choose to identify themselves to the call responder (U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2020a). VA researchers are testing the approach with other patient populations, including those seen in VA emergency departments (Landes et al., 2019).

Community-based initiatives could yield promising approaches to preventing veteran suicide.

Several efforts have recently been launched to promote community-based approaches to suicide prevention. The CDC's community prevention framework has seven components, ranging from providing economic support to promoting connectedness and creating a protective environment (Stone et al., 2017). In partnership with VA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration recently issued a challenge (and is providing assistance) to governors and mayors across the United States to create and implement suicide prevention plans targeting service members, veterans, and their families. As of November 2020, 27 states and 18 communities were participating in the program (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2020). Prior community-based initiatives similar in structure but focused on youth suicide prevention have produced promising results (Garraza et al., 2015, 2018, 2019).

Directions for Future Research

Researchers have been engaged in multiple research efforts to address veteran suicide, and many studies are ongoing. There remains much to explore to better understand why veterans take their lives and how policies and practices could enable effective interventions.

Although VA has implemented various suicide prevention strategies, not all veterans are eligible or opt to receive care through VA. Among veterans who died by suicide in 2018, 63 percent (4,057 of 6,435) did not have an encounter with VHA in the year of their death or the year prior. However, many may have been receiving care outside of VA; among the general insured population, as many as 83 percent of those who die by suicide had a health care visit in the year before their death (Ahmedani et al., 2014). There is a need for more research on veterans’ non-VA health care encounters and for studies to develop, test, inform, and evaluate community-based efforts to reach veterans outside of VA.

There are groups of veterans that are hard to reach and may be at increased risk of suicide, including those who are involved in the criminal justice system; those who are experiencing homelessness; those who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ); those who have received other-than-honorable discharges from the military; and veterans who are isolated or lonely. Veterans could fall into more than one of these groups. There is a need for research to identify whether and to what extent specific veteran subpopulations are at heightened risk for suicide and whether unique supports are needed to address their risk.

There are gaps in most U.S. communities’ ability to effectively intervene with individuals in crisis. They often rely on legal interventions or unnecessary hospitalizations that either delay or increase suicide risk (Hogan and Goldman, 2021). There is a need for more research to evaluate the harms of current crisis responses, particularly among high-risk veteran subpopulations; to identify novel solutions for responding to crises; and to evaluate the effectiveness of promising new approaches.

Additional Resources

For those needing support for themselves or a loved one, help is available from the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-888-273-TALK (8255) with an option to “press 1” to access the Military and Veterans Crisis Line.

RAND research has examined a wide range of topics related to suicide prevention among veterans and military personnel (https://www.rand.org/topics/suicide.html).

VA's suicide prevention website includes resources for veterans and the most recent state- and national-level data on veteran suicide (https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/).

The National Action Alliance for Suicide Prevention is a public-private partnership dedicated to advancing the National Strategy for Suicide Prevention (https://theactionalliance.org/).

Established by a 2019 executive order, VA PREVENTS is a three-year effort to develop and implement a comprehensive national roadmap for suicide prevention (https://www.va.gov/prevents/).

See the following for more information on suicide risk factors among veterans.

Veterans involved in the criminal justice system:

Emily R. Edwards, Molly Gromatsky, D. R. Gina Sissoko, Erin A. Hazlett, Sarah R. Sullivan, Joseph Geraci, and Marianne Goodman, “Arrest History and Psychopathology Among Veterans at Risk for Suicide,” Psychological Services, October 29, 2020.

Veterans experiencing homelessness:

Ryan Holliday, Shawn Lu, Lisa A. Brenner, Lindsey L. Monteith, Maurand M. Cappelletti, John R. Blosnich, Diana P. Brostow, Lillian Gelberg, Dina Hooshyar, Jennifer Koget, D. Keith McInnes, Ann E. Montgomery, Robert O'Brien, Robert A. Rosenheck, Susan Strickland, Gloria M. Workman, and Jack Tsai, “Preventing Suicide Among Homeless Veterans: A Consensus Statement by the Veterans Affairs Suicide Prevention Among Veterans Experiencing Homelessness Workgroup,” Medical Care, Vol. 59, Suppl. 2, April 1, 2021, pp. S103–S105.

LGBTQ veterans:

Taylor L. Boyer, Ada O. Youk, Ann P. Haas, George R. Brown, Jillian C. Shipherd, Michael R. Kauth, Guneet K. Jasuja, and John R. Blosnich, “Suicide, Homicide, and All-Cause Mortality Among Transgender and Cisgender Patients in the Veterans Health Administration,” LGBT Health, Vol. 8, No. 3, April 2021, pp. 173–180.

Kristine Lynch, Elise Gatsby, Benjamin Viernes, Karen C. Schliep, Brian W. Whitcomb, Patrick R. Alba, Scott L. DuVall, and John R. Blosnich, “Evaluation of Suicide Mortality Among Sexual Minority US Veterans from 2000 to 2017,” JAMA Network Open, Vol. 3, No. 12, December 1, 2020, article e2031357.

Veterans who have received other-than-honorable discharges from the military:

Mark A. Reger, Derek J. Smolenski, Nancy A. Skopp, Melinda J. Metzger-Abamukang, Han K. Kang, Tim A. Bullman, Sondra Perdue, and Gregory A. Gahm, “Risk of Suicide Among US Military Service Members Following Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom Deployment and Separation from the US Military,” JAMA Psychiatry, Vol. 72, No. 6, June 2015, pp. 561–569.

Veterans experiencing isolation or loneliness:

Alan R. Teo, Heather E. Marsh, Christopher W. Forsberg, Christina Nicolaidis, Jason I. Chen, Jason Newsom, Somnath Saha, and Steven K. Dobscha, “Loneliness Is Closely Associated with Depression Outcomes and Suicidal Ideation Among Military Veterans in Primary Care,” Journal of Affective Disorders, Vol. 230, April 1, 2018, pp. 42–49.

Notes

Funding for this publication was made possible by a generous gift from Daniel J. Epstein through the Epstein Family Foundation, which established the RAND Epstein Family Veterans Policy Research Institute in 2021.

References

- Ahmedani Brian K., Simon Gregory E., Stewart Christine, Beck Arne, Waitzfelder Beth E., Rossom Rebecca, Lynch Frances, Owen-Smith Ashli, Hunkeler Enid M., Whiteside Ursula, Operskalski Belinda H., Coffey M. Justin, and Solberg Leif I. “Health Care Contacts in the Year Before Suicide Death,”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014 June;Vol. 29(No. 6):870–877. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3. pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahraini Nazanin, Brenner Lisa A., Barry Catherine, Hostetter Trisha, Keusch Janelle, Post Edward P., Kessler Chad, Smith Cliff, and Matarazzo Bridget B. “Assessment of Rates of Suicide Risk Screening and Prevalence of Positive Screening Results Among US Veterans After Implementation of the Veterans Affairs Suicide Risk Identification Strategy,”. JAMA Network Open. 2020 October 21;Vol. 3(No. 10) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.22531. article e2022531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraza Lucas Godoy, Boyce Simone Peart, Walrath Christine, Goldston David B., and McKeon Richard. “An Economic Evaluation of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Suicide Prevention Program,”. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2018 February;Vol. 48(No. 1):3–11. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12321. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraza Lucas Godoy, Kuiper Nora, Goldston David B., McKeon Richard, and Walrath Christine. “Long-Term Impact of the Garrett Lee Smith Youth Suicide Prevention Program on Youth Suicide Mortality, 2006–2015,”. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2019 October;Vol. 60(No. 10):1142–1147. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13058. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garraza Lucas Godoy, Walrath Christine, Goldston David B., Reid Hailey, and McKeon Richard. “Effect of the Garrett Lee Smith Memorial Suicide Prevention Program on Suicide Attempts Among Youths,”. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 November;Vol. 72(No. 11):1143–1149. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1933. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmire Claire A., Barth Shannon K., and Bossarte Robert M. “Reevaluating Suicide Mortality for Veterans with Data from the VA-DoD Mortality Data Repository, 2000–2010,”. Psychiatric Services. 2020 June;Vol. 71(No. 6):612–615. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900324. pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan Michael F., and Goldman Matthew L. “New Opportunities to Improve Mental Health Crisis Systems,”. Psychiatric Services. 2021 February 1;Vol. 72(No. 2):169–173. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202000114. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostetter Trisha A., Hoffmire Claire A., Forster Jeri E., Adams Rachel Sayko, Stearns-Yoder Kelly, and Brenner Lisa A. “Suicide and Traumatic Brain Injury Among Individuals Seeking Veterans Health Administration Services Between Fiscal Years 2006 and 2015,”. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2019 September–October;Vol. 345:E1–E9. doi: 10.1097/HTR.0000000000000489. No. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landes Sara J., Kirchner JoAnn E., Areno John P., Reger Mark A., Abraham Traci H., Pitcock Jeffery A., Bollinger Mary J., and Comtois Katherine Anne. “Adapting and Implementing Caring Contacts in a Department of Veterans Affairs Emergency Department: A Pilot Study Protocol,”. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. 2019 October 10;Vol. 5 doi: 10.1186/s40814-019-0503-9. article 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Ivan W., Camargo Carlos A., Jr., Arias Sarah A., Sullivan Ashley F., Allen Michael H., Goldstein Amy B., Manton Anne P., Espinola Janice A., Jones Richard, Hasegawa Kohei, and Boudreaux Edwin D. “Suicide Prevention in an Emergency Department Population: The ED-SAFE Study,”. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 June;Vol. 74(No. 6):563–570. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0678. pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motto J. A., and Bostrom A. G. “A Randomized Controlled Trial of Postcrisis Suicide Prevention,”. Psychiatric Services. 2001 June;Vol. 52(No. 6):828–833. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.6.828. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Mental Health. “Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) Toolkit,”. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-conducted-at-nimh/asq-toolkit-materials/ webpage, undated. As of May 2021:

- O'Hanlon Claire, Huang Christina, Sloss Elizabeth, Price Rebecca Anhang, Hussey Peter, Farmer Carrie, Gidengil Courtney. “Comparing VA and non-VA Quality of Care: A Systematic Review,”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2017 January;Vol. 32(No. 1):105–121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3775-2. pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger Greg M., McClure Mary Lou, Ruskin David, Carter Sarah P., and Reger Mark A. “Integrating Predictive Modeling into Mental Health Care: An Example in Suicide Prevention,”. Psychiatric Services. 2019 January 1;Vol. 70(No. 1):71–74. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800242. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reger Mark A., Smolenski Derek J., Skopp Nancy A., Metzger-Abamukang Melinda J., Kang Han K., Bullman Tim A., Perdue Sondra, and Gahm Gregory A. “Risk of Suicide Among US Military Service Members Following Operation Enduring Freedom or Operation Iraqi Freedom Deployment and Separation From the US Military,”. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 June;Vol. 72(No. 6):561–569. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.3195. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roaten Kimberly, Johnson Celeste, Genzel Russell, Khan Fuad, and North Carol S. “Development and Implementation of a Universal Suicide Risk Screening Program in a Safety-Net Hospital System,”. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety. 2018 January;Vol. 44(No. 1):4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.07.006. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenbaum Michael, Kessler Ronald C., Gilman Stephen E., Colpe Lisa J., Heeringa Steven G., Stein Murray B., Ursano Robert J., Cox Kenneth L. ARMY STARRS Collaborators. “Predictors of Suicide and Accident Death in the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS): Results From the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS),”. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 May;Vol. 71(No. 5):493–503. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.4417. for the. pp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone Deb, Holland Kristin, Bartholow Brad, Crosby Alex, Davis Shane, and Wilkins Natalie. Preventing Suicide: A Technical Package of Policy, Programs, and Practices. Atlanta, Ga.: Division of Violence Prevention, National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. “Governor's and Mayor's Challenges to Prevent Suicide Among Service Members, Veterans, and Their Families,”. https://www.samhsa.gov/smvf-ta-center/mayors-governors-challenges webpage, last updated November 10, 2020: As of May 2021:

- Thom Robyn, Hogan Charlotte, and Hazen Eric. “Suicide Risk Screening in the Hospital Setting: A Review of Brief Validated Tools,”. Psychosomatics. 2020 January–February;Vol. 611:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2019.08.009. No. pp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. National Strategy for Preventing Veteran Suicide, 2018–2028. 2018. Washington, D.C.

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “VA Launches Program to Send Caring Letters to 90,000 Veterans,”. Oct 5, 2020a. press release,

- U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. 2020 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report. Nov, 2020b. Washington, D.C.