Dear Editor,

From 2003 to 2019, humanity faced five public-health emergencies. The 2020 COVID-19 pandemic gravely affected public health, mental health, economical, educational, societal, and geopolitical spheres. To tackle global emergencies, all nations must collaboratively devise, implement, and revise countermeasures to prevent unfavorable consequences and fatalities. While eradicating SARS-CoV-2 may be impossible, the COVID-19 pandemic cannot be defeated if a single world citizen remains unvaccinated, and if political and geostrategic tensions continue.

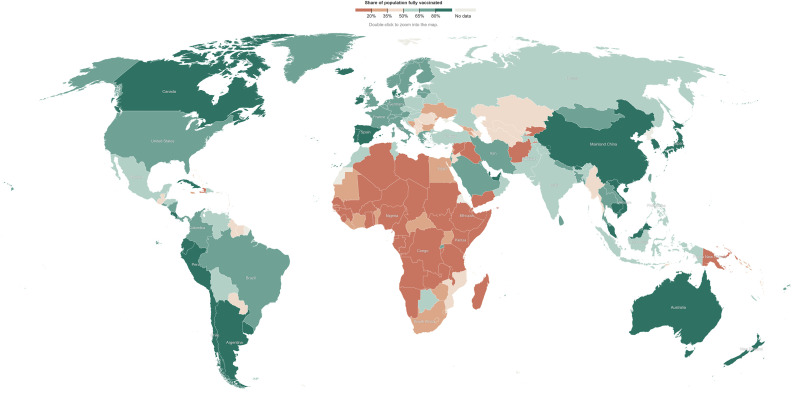

To date, WHO has coordinated diverse and timely counteractions aiming to control the pandemic. The best example is the COVAX program (COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access) which was designed to help WHO accelerate equitable access to COVID-19 tests, treatments, and vaccines. A 2022 May update on the global vaccination status (https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/world/covid-vaccinations-tracker.html) shows that 5.18 billion people (67.5%) have received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine; however, such statistics highlight discrepant vaccine distribution and availability worldwide (Fig. 1 ). Factors including vaccine nationalism, queue-jumping by high-income countries, and geostrategic rivalries had undermined the equitable vaccine distribution, especially among low-income and lower middle-income countries. Vaccine inequity could be alleviated by science-diplomats urging policymakers to accelerate immunization in the low-income countries, for example, in Africa.

Fig. 1.

Low COVID-19 vaccination rate among the African countries (updated on May 28, 2022; source: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/world/covid-vaccinations-tracker.html).

The race by pharmaceutical companies to produce vaccines using different platforms and the fierce competition for vaccine validation and commercialization internationally may have also jeopardized vaccine equity globally. During the past 2.5 years of the pandemic, different strategies have been used to develop a prophylactic vaccine against SARS-CoV-2, including targeting the viral S-protein. Similarly, many of the regulatory strategies to validate the proposed vaccines, particularly during the latest trial stages of vaccine development [1], were uncoordinated. Clearly regulatory and safety assessments including protocol review, ethical issues, and regulatory approvals before final vaccine validation demand time. However, intentional delays to deprive some countries of vaccine supplies were documented [2].

Despite WHO's efforts, some countries combatted the COVID-19 pandemic independently without cooperating. Duplicated studies or clinical trials represent lack of international collaboration and wastage of human and financial resources. Research into hydroxychloroquine as a potential treatment for COVID-19 exemplifies misguided, dictatorial leadership, wasted and duplicated research efforts, and large amounts of wasted funding. Moreover, geostrategic rivalries among high-income countries about leading and guiding the world during the pandemic [3] have clarified that such countries cannot solely defeat SARS-CoV-2. Unilateral decisions will cause undesirable and catastrophic consequences, for example, following emergence of Omicron—the latest recognized SARS-CoV-2 variant—many nations restricted international flights from South Africa in the beginning of 2022 when, in fact, many individuals were already infected with Omicron globally. Although the South African authorities promptly reported the Omicron variant, similar transparent actions by many other countries could have prevented the rise in Omicron cases.

The unprecedented impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic have inevitably highlighted the importance of international collaboration, potentially using science diplomacy [4]. Thus, along with public-health authorities, politicians, and officials, scientist-diplomats or diplomat-scientists are essential to guide and facilitate decision-making during the pandemic. Science diplomacy is a main branch of the new diplomacy that, by accessing research data and new information, can shape scientifically informed decision-making. In January 2020, the Royal Society, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) noted three interrelated activities under “science diplomacy” (https://www.aaas.org/programs/center-science-diplomacy). “Diplomacy for science” underpins achieving scientific and technical international cooperation by diplomatic efforts and resources. “Science in diplomacy” uses the scientific knowledge to advise and inform foreign policy. “Science for diplomacy” uses international scientific and technical collaborations to foster international diplomatic relations. To remove obstacles and generate constructive international relations, the three pillars of science diplomacy should be applied. Multilateral research and rapid data-sharing on various aspects of the biologic features of SARS-CoV-2, for example, are promising avenues for collaboration. Collaborations could include sharing the SARS-CoV-2 genetic sequencing information, and knowledge on clinical management and treatment of severe COVID-19 or long COVID-19. In January 2020, approximately 100 academic journals, societies, institutes, and companies agreed—as informed by the 2016 Statement on Data Sharing in Public Health Emergencies—to make data on COVID-19 publicly available, at least until the outbreak lasts.

In conclusion, international efforts need to be coordinated by high-income countries, superpowers, and all other nations through their contributions to WHO. Importantly, management of the pandemic should rest with WHO, and geostrategic disputes must not guide the vaccine supply and distribution to different countries. WHO has consistently warned against pursuit of nationalism. Inequities recognized during the management of the COVID-19 pandemic must be rectified by science diplomacy. Persuading and informing governments, politicians, and policymakers to respond prudently against the pandemic have never been more critical. We suggest that international cooperation should 1) maintain and support WHO's independence to devise and implement surveillance programs for monitoring the spread of the virus from one country to another; and 2) to avoid manipulating international funding resources over political disputes and regional interests; this will weaken WHO directly. Thus, science diplomacy should be used to effectively control the pandemic while SARS-CoV-2 had already taught humanity to act together.

Please state whether ethical approval was given, by whom and the relevant Judgement's reference number

This article does not require any human/animal subjects to acquire ethics approvals.

Please state any sources of funding for your research

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author contribution

Farid Rahimi: Conceptualization, writing – Review & editing. Amin Talebi Bezmin Abadi: Conceptualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. All authors critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript before submitting.

Please state any conflicts of interest

None.

Research registration Unique Identifying number (UIN)

-

1.

Name of the registry: Not applicable.

-

2.

Unique Identifying number or registration ID: Not applicable.

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked): Not applicable.

Guarantor

Both authors.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

References

- 1.Kaur S.P., Gupta V. COVID-19 Vaccine: a comprehensive status report. Virus Res. 2020;288 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2020.198114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter D.J., Abdool Karim S.S., Baden L.R., Farrar J.J., Hamel M.B., Longo D.L., Morrissey S., Rubin E.J. Addressing vaccine inequity – Covid-19 vaccines as a global public good. N. Engl. J. Med. 2022;386:1176–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2202547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhao S. Rhetoric and reality of China's global leadership in the context of COVID-19: implications for the US-led world order and liberal globalization. J. Contemp. China. 2020;30:233–248. doi: 10.1080/10670564.2020.1790900. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bahi R. The geopolitics of COVID-19: US-China rivalry and the imminent Kindleberger trap. Rev. Economics Political Sci. 2021;6:76–94. doi: 10.1108/reps-10-2020-0153. [DOI] [Google Scholar]