Abstract

Spermatogenesis is a complex, multistep process during which spermatogonia give rise to spermatozoa. Transcription Factor Like 5 (TCFL5) is a transcription factor that has been described expressed during spermatogenesis. In order to decipher the role of TCFL5 during in vivo spermatogenesis, we generated two mouse models. Ubiquitous removal of TCFL5 generated by breeding TCFL5fl/fl with SOX2-Cre mice resulted in sterile males being unable to produce spermatozoa due to a dramatic alteration of the testis architecture presenting meiosis arrest and lack of spermatids. SYCP3, SYCP1 and H1T expression analysis showed that TCFL5 deficiency causes alterations during pachytene/diplotene transition resulting in a meiotic arrest in a diplotene-like stage. Even more, TCFL5 deficient pachytene showed alterations in the number of MLH1 foci and the condensation of the sexual body. In addition, tamoxifen-inducible TCFL5 knockout mice showed, besides meiosis phenotype, alterations in the spermatids elongation process resulting in aberrant spermatids. Furthermore, TCFL5 deficiency increased spermatogonia maintenance genes (Dalz, Sox2, and Dmrt1) but also increased meiosis genes (Syce1, Stag3, and Morc2a) suggesting that the synaptonemal complex forms well, but cannot separate and meiosis does not proceed. TCFL5 is able to bind to the promoter of Syce1, Stag3, Dmrt1, and Syce1 suggesting a direct control of their expression. In conclusion, TCFL5 plays an essential role in spermatogenesis progression being indispensable for meiosis resolution and spermatids maturation.

Subject terms: Spermatogenesis, Meiosis

Introduction

Spermatogenesis is a complex process that implies different cellular mechanisms to generate spermatozoa containing half of the genetic material of the precursor spermatogonia. It can be divided into three different stages: mitosis, meiosis, and spermiogenesis1. In the first step, spermatogonia, which is maintained by a series of mitotic divisions in a proliferative phase, differentiate to primary spermatocytes2. In this process, several extrinsic and intrinsic factors act together to maintain the correct self-renewal or promote differentiation to spermatocytes. Alterations in these pathways lead to early fertility issues3,4. The next phase comprises two consecutive meiotic divisions where primary spermatocytes undergo secondary spermatocytes during meiosis-I and, then generate haploid spermatids as a result of the meiosis-II5. The deregulation of meiosis leads to a meiotic arrest and aberrant spermatogenesis that in most cases produces infertility6,7. Finally, during spermiogenesis, haploid round spermatids suffer a complex structural transformation to become spermatozoa, comprised of the following steps: (1) formation of the acrosome, (2) condensation of the nucleus, (3) development of the sperm flagellum, (4) reorganization of cellular organelles, and (5) reduction of the cytoplasm8.

The meiotic process is the most important phase of spermatogenesis. Here, diploid cells give rise to haploid cells suffering two consecutive divisions following one round of replication and recombining their DNA. The main step involves the prophase-I of meiosis-I. In prophase-I homologous chromosomes recombine and generate genetic diversity. This phase is well known and is divided into 5 stages: (1) leptotene, where chromosome condensation is produced; (2) zygotene, where the pairing of homologous chromosomes starts and synaptonemal complexes, a multi-protein structure that held homologous chromosomes together9, are formed; (3) pachytene, where genetic material derived from paternal and maternal homologous chromosomes is exchanged by recombination of sister chromatids, (4) diplotene, where synaptonemal complexes disassemble, chromosomes separate except at the chiasmata sites, and (5) diakinesis, where chromosomes condense and the nuclear envelope disintegrates10. Formation of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), homologous recognition, synapsis, and meiotic recombination are necessary for the correct progression of prophase-I. At the end of the meiotic prophase-I, the four sister chromatids are visible, the nuclear envelope disappears, and chromosomes arrange on the metaphase plate. The resulting secondary spermatocytes proceed to the second meiotic division, this time without DNA synthesis, resulting in haploid round spermatids.

Transcription factors (TFs) are key players in the control of spermatogenesis. Specifically, some members of the basic Helix Loop Helix (bHLH) family of TFs are well known as a fundamental proteins to the correct development of gametes11,12. Transcription Factor Like 5 (TCFL5) is a bHLH scarcely studied, first described in 1998 in human testis, specifically at the diplotene stage of primary spermatocytes13. Since then, few studies have reported its role during the spermatogenesis process. In mice, TCFL5 binds to the non-canonical E-box region CACGCG of Calmegin (Clgn) promoter14, a chaperon required for sperm mobility and adhesion to zona pellucida15,16. In addition, TCFL5 was found expressed in early and late elongating spermatids co-localizing with α-tubulin and centrioles, respectively. It is not expressed in mature spermatozoa17. TCFL5 is also described as a partner of MEIG1, a protein involved in spermiogenesis18. Recently, it has been related to the lack of TCFL5 expression in human testicular tumors with a pre-meiotic origin19.

To investigate the role of TCFL5 in spermatogenesis, we generated two TCFL5 knockout mouse models. The complete TCFL5 null mice model, using Sox2 promoter-controlled CRE recombinase, led to infertility in male mice. The phenotypic analysis of this model indicates that TCFL5 is necessary for meiosis progression. Besides, the tamoxifen-conditional knockout model shows that TCFL5, in addition to the above, also has a role during the spermiogenesis process. Gene expression analysis suggests that transcription factor TCFL5 could control important genes in spermatogenesis affecting mitosis, meiosis and spermiogenesis. Our data demonstrate the essential role of TCFL5 in spermatogenesis progression being indispensable for meiosis resolution and spermatids maturation.

Material and methods

Tcfl5 knockout mice

Conditional TCFL5 LoxP system (TCFL5fl/fl) mice were created by Cyagen Bioscience using standard procedures. Briefly, a recombinant vector for TCFL5 flanking exon 4 with a LoxP system was transfected in embryonic stem cells (ESC). Selected ESCs were microinjected in blastocysts, followed by chimera production. Germline transmission was confirmed after breeding with wild-type mice. To remove exon 4, two strategies were carried out: (1) Ubiquitous TCFL5 knockout mice were generated crossing with SOX2cre/cre mice (B6.Cg-Edil3Tg(Sox2-cre)1Amc/J, Jackson Laboratory #008454). After Cre deletion, a constitutive TCFL5 knockout mice line was established; (2) Conditional TCFL5 knockout mice dependent on tamoxifen administration were generated crossing with CAGGCRE-ER™ mice (B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-cre/Esr1*)5Amc/J, Jackson Laboratory #004682). Tamoxifen-inducible cre-mediated recombination system is driven by the chicken beta actin promoter/enhancer coupled with the cytomegalovirus (CMV) immediate-early enhancer. Cre recombinase is fused to a G525R mutant form of the mouse estrogen receptor being restricted to cytoplasm and, only after tamoxifen treatment, it access to the nucleus.

All animals were allowed free access to water and food. Animals were euthanized by CO2 inhalation at the end of every experiment. All animal care procedures used in this study were carried out in accordance with ARRIVE guidelines. All animal procedures were performed in strict accordance with the European Commission legislation for the protection of animal used purposes (2010/63/EU). The protocol for the treatment of the animals was approved by the Comité de Ética de la Dirección General del Medio Ambiente de la Comunidad de Madrid, Spain and was supervised by the Ethics Committee of CBMSO (Madrid, Spain).

Histological analysis

Testes and epididymis from 8-week-mice were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin (pH 7.4) and embedded in paraffin. 3 μm paraffin-embedded sections were stained with Hematoxylin–Eosin (HE) or Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) as described previously. Images were taken with an Axioskop2 Plus (Zeiss) coupled to DMC6200 camera (Leica).

Immunofluorescence

Testes from 8 week-mice were decapsulated and seminiferous tubules were fixed and processed for spermatocyte spreading by the drying-down technique previously described20, or processed for squashing as previously reported21. Spread spermatocytes and squashed seminiferous tubules slides were rinsed three times in PBS and blocked with 2% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS for 20 min at room temperature (RT). After blocking, slides were incubated overnight at 4 °C with anti-TCFL5 (Sigma), anti-SYCP3 (Cell Signalling), anti-SYCP1 (Abcam), anti-H1t (Cell Signalling), anti-γH2AX (Cell Signalling), anti-MLH1 (Pharmingen), anti-Pan-cadherin (Cell Signaling) and anti-Tubulin (Cell Signalling) primary antibodies. Then, slides were washed in PBS and incubated for 1 h at RT with their corresponding secondary antibodies against rabbit, mouse, and guinea pig IgGs conjugated with Alexa 555, Alexa 594, and Alexa 488 (Molecular Probes). For actin and flagellar mitochondria immunodetections Alexa 488 Phalloidin (Thermo Fisher) and Mitotracker Red CM-H 2 Xros (Thermo Fisher) were used, respectively. Finally, cells were stained with 1 μg/ml DAPI and mounted using ProLong Glass Antifade Mountant (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images and stacks were taken in sCMOS camera on a Zeiss Axiovert microscope and analyzed using ImageJ (NIH) and Adobe Photoshop CS5.1 software.

TUNEL assay

Apoptotic cells were determined using Click-iT™ Plus TUNEL assay kit (Thermo Fisher). 3 μm formalin fixed paraffin-embedded sections of testis were stained according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Images and stacks were taken in sCMOS camera on a Zeis Axiovert microscope and analyzed using ImageJ (NIH) and Adobe Photoshop CS5.1 software.

Immunohistochemistry and immunohistofluorescence

Testes from 8 week-mice were fixed in 4% phosphate-buffered formalin (pH 7.4) and embedded in paraffin. 3 μm paraffin-embedded sections were incubated with antibodies for immunohistochemistry (IHC) or immunohistofluorescence (IFC): anti-TCFL5 (Sigma), anti-SYCP3 (Cell Signalling) and anti-panCadherin (Cell Signalling), and their corresponding secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP (Envision + Dual link System HRP, Dako) for IHC, or Alexas 594 and 488 (Molecular Probes), for IFC. Finally, IHC sections were developed using DAB solution (Liquid DAB + substrate chromogen system, DAKO K3468), counterstained with Hematoxylin and images were taken with a sCMOS camera on a Zeis Axiovert microscope. IFC sections were counterstained with 1 μg/ml DAPI and images were taken with a LEICA DMD108 Digital Microimaging Device (Leica Microsystems).

Western blot analysis

Protein was obtained from 8-weeks-old mice testes using RIPA cell lysis buffer. Protein concentration was determined using Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Protein was resolved on 10–16% SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (BioRad). Membranes were blocked in 5% BSA in Tris-Buffered-Saline with 0.1% Tween20 (TBS-T). For specific protein detection, membranes were incubated with anti-TCFL5-E1 (custom made antibody against CAGPDGAPEARAKPAVR peptide of exon 1, GenScript), anti-SYCP3 (Cell Signaling) and anti-HSP90 (Santa Cruz) in 5% BSA-TBS-T overnight at 4 °C. After washing the membrane, it was incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at RT. Luminescence signal was detected in Amersham Imager 600 (GE Healthcare).

RNA analysis

RNA was isolated from 8-weeks-old mice testes using TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. 1 μg of total RNA and sorted cells was reverse transcribed using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) following the manufacturer’s recommendation. The resulting cDNA was used both for PCR using GoTaq Flexi DNA Polymerase (Promega) or quantitative PCR (qPCR) using GoTaq 1PCR Master Mix (Promega) with specific primers (Supplementary Table 1), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For qPCR, relative mRNA levels were calculated in accordance with the point where each curve crossed the threshold cycle (Ct) from ABI Prism 7900HT (Applied Biosystems), subtracting the Ct of the 18S housekeeping gene (∆Ct) according to the formula: 2−(∆Ct problem−∆Ct control).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP) analysis

Seminiferous tubules were digested into a single-cell suspension as previously described22. Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed as described23. Briefly, testis single-cell suspension was fixed, cross-linked, and lysed. The cross-linked cell chromatin was sheared by sonication using a Bioruptor Next Gen (Diagenode). Sheared chromatin was incubated with Dynabeads Protein G (Sigma), and anti-TCFL5 (Sigma). Protein–DNA complex was immunoprecipitated using QuadroMACS Separator (Miltenyl Biotec). DNA was isolated and analyzed by PCR and qPCR using specific oligonucleotides (Supplementary Table 1).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v6.0 software (GraphPad Software, LLC). Results were expressed as means ± SEM (Standard Error of the Mean). Student’s t-test was used for differences significance, marked as *p > 0.05, **p > 0.01 and ***p > 0.001.

Results

TCFL5 expression and knockout generation

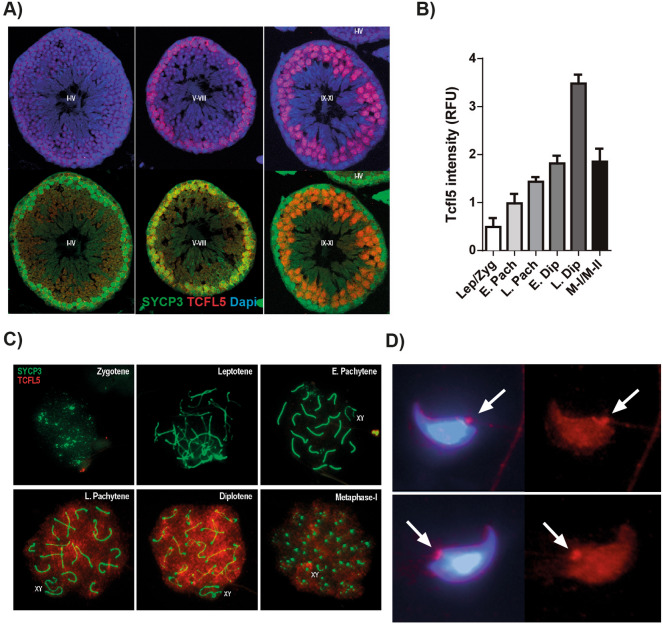

TCFL5 expression has been described during the first meiotic prophase. In order to accurately study the effect of Tcfl5 deletion and infer its function, we first established the detailed distribution and expression levels of TCFL5 during male meiosis-I. For this purpose, we performed double immunostainings in both testis cross-sections and spermatocytes spread, of TCFL5 with SYCP3, a structural component of the axial/lateral elements of the synaptonemal complex that allows identifying the different meiotic-I stages. Immunofluorescence of TCFL5 in cross-sections of WT testis showed TCFL5 staining in stages V-VIII and IX-XI indicating it is expressed in spermatocytes but not in spermatogonia and spermatids (Fig. 1A). More in detail, the analysis of the expression level of TCFL5 in spread spermatocytes showed that TCFL5 expression begins during early pachytene and presents a significant increase at mid/late pachytene reaching its higher expression at diplotene distributed among the whole chromatin (Fig. 1B,C). Then, TCFL5 expression was gradually decreasing in the latter stages of the meiosis-I. In addition, no expression was detected in spermatids from immunofluorescence cross-section, however, testicular spread showed TCFL5 expression in spermatids concentrated at the base of the flagellum (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1.

TCFL5 distribution during meiosis-I. (A) Immunohistofluorescence of seminiferous tubules stages I–IV, V–VIII and IX–X in TCFL5+/+ mice. TCFL5 (red), SYCP3 (green) and nucleus (Dapi, Blue) were detected. TCFL5 is expressed in spermatocytes but neither spermatogonia nor spermatids. (B) Quantification of TCFL5 expression in spread primary spermatocytes. TCFL5 is mostly expressed from late pachytene to diplotene. (C) Representative immunofluorescence of spread primary spermatocytes in TCFL5+/+ mice. SYCP3 (green), TCFL5 (red) and nucleus (Dapi, Blue) were detected. D) Representative immunofluorescence of spermatids. TCFL5 (red) and nucleus (Dapi, Blue) were detected.

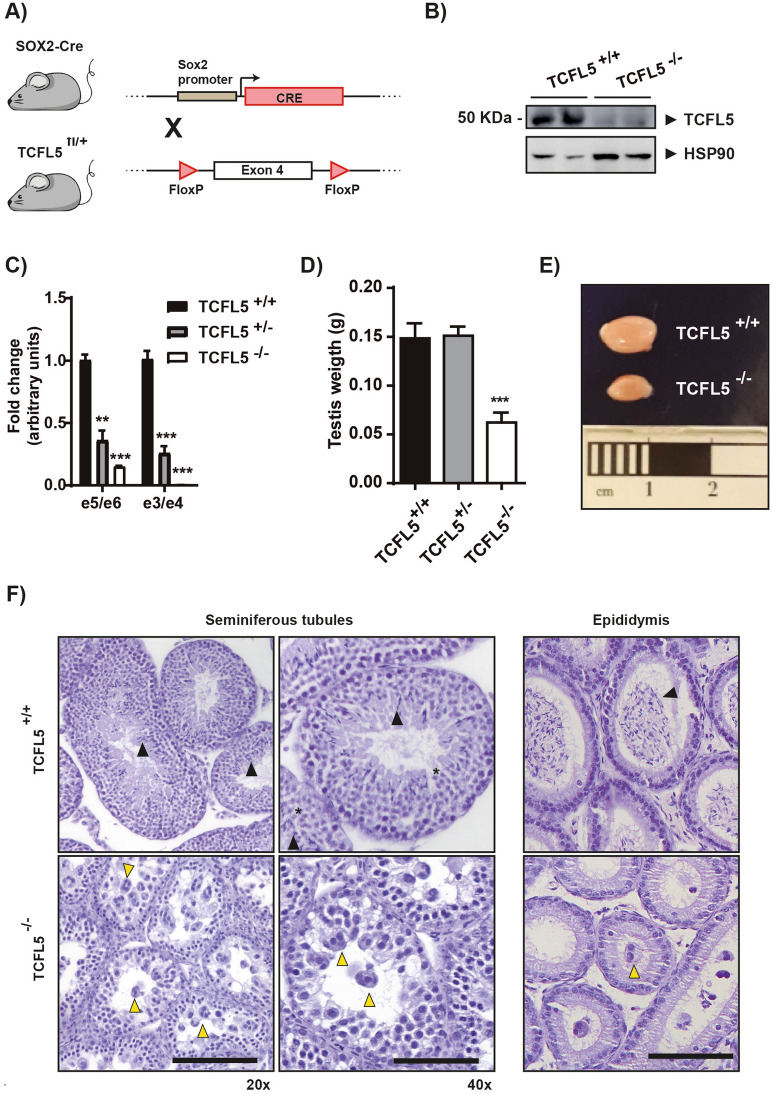

To assess the function of Tcfl5 during in vivo spermatogenesis, we generated a conditional TCFL5 knockout mouse using LoxP system, which was inserted flanking exon 4 (hereafter named TCFL5fl/fl). Exon 4 contains part of the bHLH domain so its deletion produces an aberrant and non-functional protein (Supplementary Fig. 1A). Then, two strategies were carried out to remove exon 4. First, we generated a constitutive Tcfl5 knockout crossing TCFL5fl/fl mice to SOX2-Cre mice24 (Fig. 2A). Sox2 is expressed during the first stages of embryo development. After Cre deletion, pups were crossed to establish a Tcfl5 knockout mice line (hereafter named TCFL5−/−). TCFL5 protein detection confirmed the lack of detectable TCFL5 expression in null mice (Fig. 2B). Moreover, quantitative mRNA expression analysis of the testis demonstrates a complete reduction of e3/e4 expression and a strong reduction of e5/e6, although this was not complete in null mice (Fig. 2C). Heterozygous mice also showed a Tcfl5 expression reduction indicating a gene dosage effect. The second strategy consisted of the generation of conditional Tcfl5 knockout mice dependent on tamoxifen administration in adult mice. To do this, TCFL5fl/fl mice were crossed to Tx-Cre mice25 (hereafter named TCFL5-Tx) (Supplementary Fig. 2A). TCFL5-Tx mice were treated intraperitoneally with tamoxifen for 5 days. Exon 4 recombination was observed specifically in those Tcfl5-Tx mice treated with tamoxifen (Supplementary Fig. 2B). Analysis of the mRNA expression of testis showed that Tcfl5 expression was, as expected, reduced in TCFL5-Tx mice after treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2C).

Figure 2.

TCFL5−/− mice alterations present in testis. (A) Scheme of TCFL5 knockout (TCFL5−/−) mice generation-strategy. TCFL5fl/fl mice were crossed with SOX2-Cre mice to remove exon 4 and generate an aberrant transcript for TCFL5 from the first stage of development. (B) TCFL5 protein detection by WB. TCFL5−/− mice reduce drastically TCFL5 expression. (C) Tcfl5 mRNA expression determined by qPCR using two different primer pairs. TCFL5+/− mice present half the expression of the TCFL5+/+ mice. TCFL5−/− mice reduce drastically Tcfl5 expression. (n = 8), t-test p < 0.01 (**), p < 0.001 (***). (D) Testis weights from TCFL5+/+, TCFL5+/− and TCFL5−/− mice. TCFL5−/− present half the weight of the TCFL5+/+ while TCFL5+/− do not show difference in testis weight. (n = 8), ***p < 0.001. (E) Testis sizes from TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/−. TCFL5−/− present half the size of the TCFL5+/+. (F) Seminiferous tubules architecture and epididymis sections from TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/− mice. TCFL5+/+ mice present no alteration and normal spermatids (black triangle). Abnormal morphology features with multinucleated rounded giant cells (yellow triangle) and no spermatozoa in the TCFL5−/− mice. Scale bar 100 µm in a and b. Zoom 1.5X in a’ and b’.

Recent database entries have shown several sequences for Tcfl5 (Supplementary Table 2). According to this information, the mouse Tcfl5 locus is composed of 7 exons: e1, e2, e3, e4, e4b, e5 and e6. There are at least 4 putative alternative mRNA transcripts: (1) Tcfl5_e6a (the one mostly described in the literature) composed by exons e1, e2, e3, e4, e5, and e6; (2) Tcfl5_e6b composed by exons e1, e2, e3, e4 and e6; (3) Tcfl5_e4b composed by exons e1, e2, e3 and e4b; (4) Tcfl5_e5 composed by the exons e1, e3, e4 and e5 (Supplementary Fig. 1B). We addressed the expression of those Tcfl5 isoforms in testis. Transcript amplification using PCR primers annealing on exons 1 and 6 (e1/e6), and e1/e5 showed that the canonical isoform Tcfl5_e6 was expressed in TCFL5+/+ mouse testis discarding Tcfl5_e6∆ and Tcfl5_e5. Moreover, TCFL5−/− testes lack the full-length transcript, although they show an aberrant mRNA transcript related to exon 4 removal (Supplementary Fig. 1C). Further, amplification of adjacent exons confirmed that the only isoform expressed in testis is the canonical Tcfl5_e6. TCFL5−/− testes exon pattern expression confirmed the presence of aberrant transcripts (Supplementary Fig. 1D).

TCFL5 deficiency produces severe alterations in spermatogenesis

TCFL5−/− mice were viable and did not show visible developmental abnormalities. However, we noticed reproduction problems in both TCFL5+/− and TCFL5−/− mice. After recording mice crosses, we observed that TCFL5+/− mice were fertile, but the number of litters obtained was lower compared to TCFL5fl/fl control mice crosses (Supplementary Fig. 3A). More importantly, TCFL5−/− mice crosses did not produce any litter, suggesting a severe fertility alteration. In addition, the percentage of TCFL5+/− crosses with pups were less (32%) than TCFL5fl/fl crosses (93%) (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Examination of testes of 8-week-old mice revealed that TCFL5−/− testis size was remarkably reduced compared to TCFL5+/− and WT (Fig. 2D,E). Histological analysis of the testes revealed that TCFL5−/− mice presented severe defects in the seminiferous tubules architecture. Cross-sections of TCFL5 null testes showed abnormal morphology features, including multinucleated round giant cells containing primary spermatocytes, and no spermatozoa in the lumen of the seminiferous tubules, which denotes compromised spermatogenesis during meiosis. TCFL5−/− mice lacked spermatozoa in the epididymis and presented some abnormal multinucleated round giant cells (Fig. 2F). Furthermore, epididymis smear showed the complete depletion of sperm in TCFL5−/− mice, indicating the reason for their sterility (Data not shown).

To confirm these results and to have a different insight of the role of TCFL5 in the spermatogenesis process, we delete TCFL5 in adult mice using TCFL5-Tx mice. 8-weeks-old TCFL5-Tx mice were treated intraperitoneally with tamoxifen for 5 days. Mice were sacrificed at 45 days and testes were analyzed. Interestingly, testis size and weight were also lower in treated mice with tamoxifen than in non-treated mice (Supplementary Fig. 2D,E). Moreover, histological analysis of testes showed that tamoxifen treatment of TCFL5-Tx mice induced alterations of the seminiferous tubules structure, similar to those observed in TCFL5−/− testis. Most of the seminiferous tubules in these testes presented multinucleated round giant cells containing primary spermatocytes and a reduced number of elongated spermatids in the lumen (Supplementary Fig. 2F). Altogether, these data corroborate the role of TCFL5 in spermatogenesis progression.

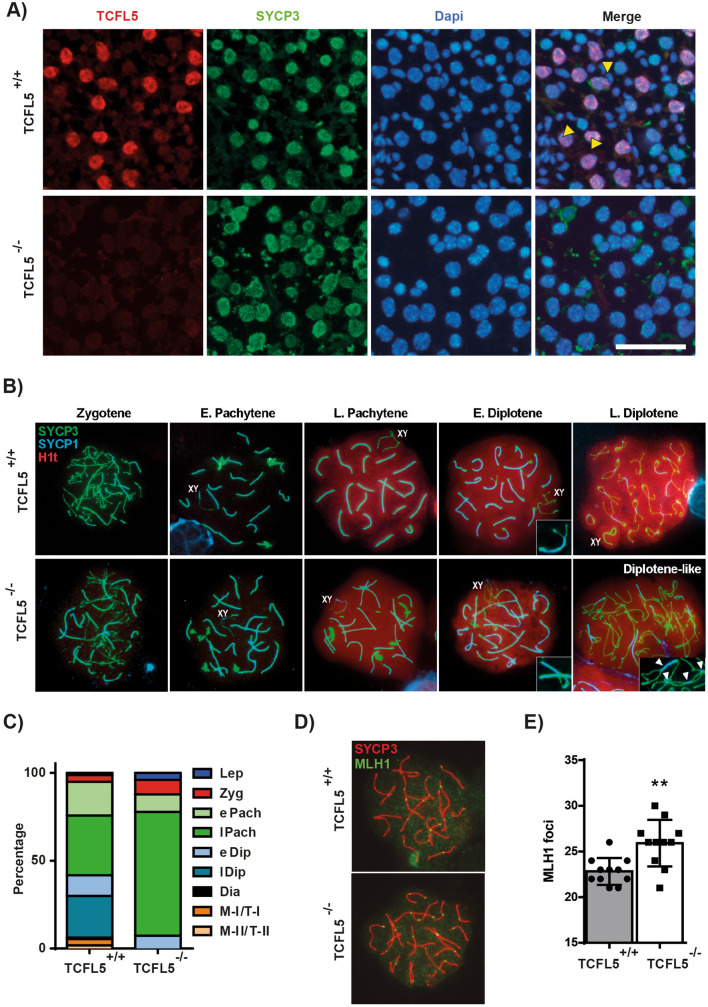

TCFL5 deficiency arrests spermatocytes in the late pachytene stage

To study the effects of Tcfl5 null mice we first confirmed by immunofluorescence the absence of TCFL5 protein in TCFL5−/− spermatocytes. As expected TCFL5 was only detected in the WT mice confirming the lack of TCFL5 expression in TCFL5−/− testis. SYCP3 was detected in both WT and TCFL5−/− primary spermatocytes suggesting that cells enter meiosis (Fig. 3A). In addition, SYCP3 protein expression by western blotting in testis extract from TCFL5−/− did not show changes compared to WT (Supplementary Fig. 4). However, neither round nor elongated nucleus was detected in TCFL5−/− mice suggesting the absence of secondary spermatocytes and spermatids (Fig. 3A), and in consequence, a meiotic arrest. These data demonstrate that TCFL5 deficiency impairs meiosis progression and suggests a possible arrest during meiosis-I.

Figure 3.

TCFL5 deficiency arrest cells in pachytene/diplotene transition. (A) Immunofluorescence of squashed seminiferous tubules in TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/− mice. TCFL5 (red), SYCP3 (green) and nucleus (Dapi, Blue) were detected. TCFL5 was only expressed in TCFL5+/+ mice in cells that express SYCP3. Yellow triangles mark secondary spermatocytes and spermatids absence in TCFL5−/− mice. Scale bar 40 µm. (B) Immunofluorescence of spread spermatocytes in TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/− mice. SYCP3 (green), SYCP1 (blue) and H1t (red) were detected. SYCP3 staining appears disrupted in TCFL5−/− mice. Scale bar 20 µm. (C) Quantification of meiotic stages in TCFL5+/+ (n = 3) and TCFL5−/− mice (n = 3). (D) Immunofluorescence of spread spermatocytes in TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/− mice. SYCP3 (green) and MLH1 (red) were detected. TCFL5−/− mice presented more MLH1 foci. Scale bar 20 µm. (E) MLH1 quantification in TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/− mice. (n = 8), **p < 0.01.

To further investigate the meiosis-I arrest in TCFL5 null mice, we analyzed spermatocytes spreads the distribution pattern of two synaptic proteins: SYCP3 and SYCP1, a transversal filament protein of the central element of the synaptonemal complex (SC)9, and a specific testis marker of late prophase-I, the histone variant H1t. TCFL5−/− chromosomes correctly synapse since zygotene and reach to pachytene stage. SYCP3 appears as thin lines (axial/lateral elements) at zygotene, while thicker lines are observed in pachytene corresponding to the SCs. SYCP1 is accumulated in the synapsed regions since zygotene, as occurs in WT. At pachytene, both markers colocalize at SCs and some SYCP3 extrachromosomal aggregations are observed during early-pachytenes in both conditions. However, at late prophase-I, when H1t is broadly detected throughout the chromatin, the abnormal SYCP3 aggregations remained in TCFL5−/− spermatocytes. Besides, late-pachytene SYCP3 accumulates at the telomeres of each SC in WT spermatocytes but not in TCFL5−/−. Homologous unpairing marks diplotene onset and SYCP1 is lost from desynapsed regions. In WT diplotenes SCs became shorter due to chromosome condensation and SYCP3 accumulates at telomeres. However, TCFL5−/− spermatocytes are not able to completely desynapse, chromosomes remain enlarged and there is no SYCP3 accumulation at telomeres. TCFL5−/− spermatocytes remained in a diplotene-like stage (Fig. 3B).

Quantification analysis of the different meiosis stages in spermatocyte spreads confirmed that TCFL5−/− spermatocytes arrest at early diplotene stage. Interestingly, TCFL5−/− spermatocytes showed a significant accumulation at mid/late pachytene in comparison with WT (Fig. 3C). Altogether, these data confirm that meiosis progression is arrested at pachytene/diplotene transition in TCFL5−/− male mice.

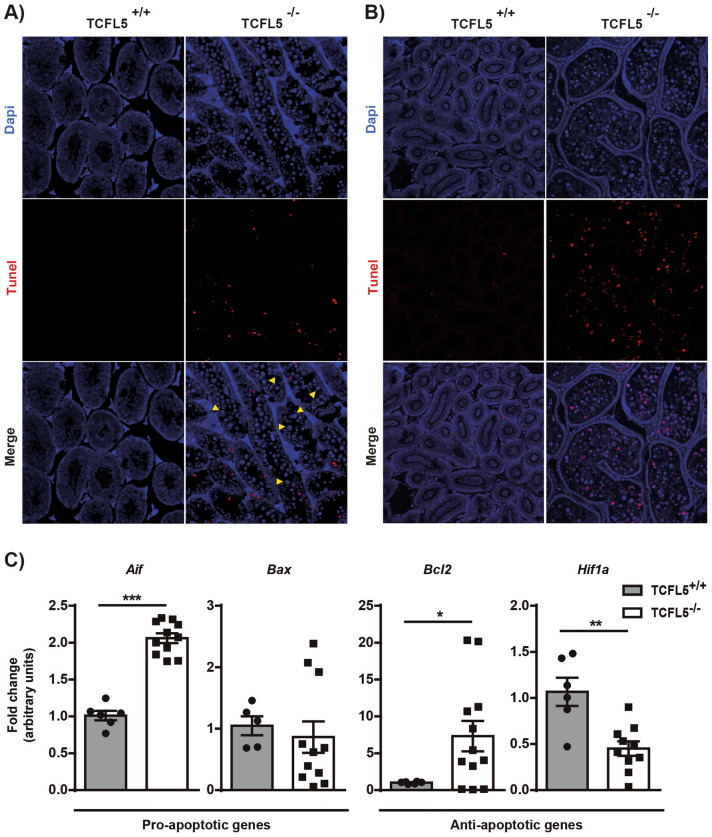

Multinucleated round giant cells were studied more in detail. SYCP3 immunohistochemistry staining revealed that the cells present in the cysts are SYCP3 positive indicating that these cells are in the prophase-I meiotic stage (Supplementary Fig. 5A). Specifically, the analysis of SYCP3 and H1t showed that cells contained in cyst are arrested in late-pachytene and diplotene-like stages (Supplementary Fig. 5B). In addition, pan-cadherin staining showed that these cells are included in the same cytoplasm revealing alterations in cyst conformation and/or cytokinesis process (Supplementary Fig. 5C). TUNEL assay showed that cells contained in cyst were mostly alive in seminiferous tubules (Fig. 4A). However, they enter into apoptosis when they reach the epididymis (Fig. 4B). In this sense, mRNA expression of both pro-apoptotic genes Aif and Bax, and anti-apoptotic genes Bcl2 and Hif1a were altered in the seminiferous tubules extracts of null mice compared to WT mice (Fig. 4C). Altogether, these results suggest that cells contained in aberrant cysts were not able to finish the prophase-I stage and then activate the cell death pathway and spermatocytes are consequently eliminated by apoptosis in TCFL5−/− mice.

Figure 4.

TCFL5 spermatocytes die in the epididymis. (A) TUNEL assay in seminiferous tubules cross-section of TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/− mice. Apoptotic cells (red) and nucleus (Dapi, Blue) were detected. TCFL5−/− mice present apoptotic cells in the seminiferous tubules. Yellow arrows show the live multinucleated round giant cells. (B) TUNEL assay in epididymis cross-section of TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/− mice. Apoptotic cells (red) and nucleus (Dapi, Blue) were detected. TCFL5−/− mice present apoptotic cells in the epididymis. (C) mRNA expression by qPCR of pro-apoptotic genes Aif and Bax, and anti-apoptotic genes Bcl2, and Hif1a in TCFL5+/+ and TCFL5−/− mice. TCFL5 null mice present alterations in the expression of these genes. (n = 8), *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

TCFL5 participate in the regulation of meiotic crossover formation

To further understand the possible causes of late-pachytene arrest, we performed immunolabelings on spread spermatocytes with γH2AX, a marker of unsynapsed chromosomes, recombination foci and sex chromosome inactivation, and MLH1, a marker of mature recombination nodules. As occurs in WT, TCFL5−/− spermatocytes present a normal distribution of γH2AX marker. γH2AX is detectable at leptotene broadly localized throughout the nucleus and remained localized at unsynapsed chromosomes during early prophase-I. At pachytene onset, γH2AX marked the sex body chromatin and recombination foci along the SC marked with SYCP3. As pachytene progresses, γH2AX foci disappear being not detectable at diplotene. The number and pattern of these recombination foci seem not altered in TCFL5−/− pachytenes. However, sexual body condensation of TCFL5−/− late-pachytenes and diplotenes seem to be less condensed than in WT attending to the γH2AX area which is higher in TCFL5−/− mice than WT (Supplementary Fig. 6A,B).

To analyse the final effect of the recombination process we performed double immunostaining of MLH1 and SYCP1. MLH1 is essential for crossover formation and in mice, MLH1 foci appear in mid-pachytene26. Surprisingly, the quantitative analysis of the MLH1 foci showed a significant increase in TCFL5−/− pachytenes (27.62 ± 0.77) compare to WT (22.83 ± 0.44). This recombination foci accumulation could be due to a recombination misregulation in TCFL5−/− spermatocytes (Fig. 3D,E).

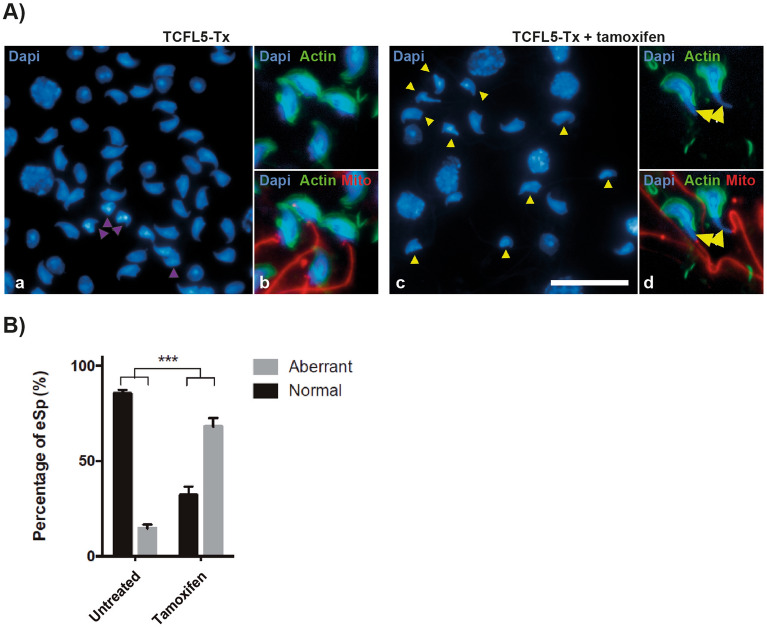

TCFL5 deficiency produces aberrant spermatids

Although TCFL5 null mice completely block meiosis and did not have secondary spermatocytes or spermatids, we observed another defect in TCFL5-Tx mice. TCFL5-Tx mice, contrary to TCFL5−/−, allow assessing if TCFL5 has a role in later stages of spermatogenesis. Interestingly, after tamoxifen treatment, we observed alterations in the morphology of elongated spermatids (Fig. 5A). In this sense, TCFL5-Tx mice produced an average of 4.5-fold more aberrant elongated spermatids than not treated mice (Fig. 5B). This significant increase suggests an important role of TCFL5 also in spermiogenesis.

Figure 5.

TCFL5-Tx treated with tamoxifen produced aberrant elongated spermatids. (A) Squashed eSp stained with DAPI in TCFL5-Tx non-treated and TCFL5-Tx treatesd with tamoxifen. TCFL5-Tx non-treated eSp present normal morphology (purple triangle), while most of TCFL5-Tx eSp present aberrant morphology (yellow triangle). Scale bar 20 µm. Actin (green), Mito (red) and nucleus (Dapi, Blue) were detected. (B) Percentage of elongated spermatids (eSp) in TCFL5-Tx non-treated and TCFL5-Tx treated with tamoxifen (TCFL5-Tx) mice. TCFL5-Tx non-treated mice produced an average of 14.6% aberrant eSp, while TCFL5-Tx treated an average of 67.9%, a 4.6-fold more aberrant eSp than TCFL5-Tx non-treated. (n = 4), t-test p < 0.001 (***).

TCFL5 controls the expression of genes involved in different steps of spermatogenesis

To find potential candidates for TCFL5-related genes, we first obtained the most-Tcfl5 correlated genes from the ARCHS4 web resource, a website that collects RNA-Seq data and analyzes them27 (Supplementary Table 3). Gene ontology and functional categories analysis28,29 showed that genes related to Tcfl5 are mostly implicated in spermatogenesis, specifically in meiosis and spermiogenesis (Supplementary Fig. 7A,B). Syce1 (synapsis), Stag3 (cohesion), and Morc2a (chromatin-remodelling factor) were selected as representative genes of the list associated with meiosis. Interestingly, mRNA expression levels of all these 3 genes were increased in TCFL5−/− mice, supporting the idea of a central role of TCFL5 in this process (Supplementary Fig. 7C). Moreover, the expression of genes implicated in the post-meiotic process, such as Dcaf17, Spata16, and Tekt3 also correlated with that of Tcfl5. The mRNA analysis of correlated Tcfl5 genes showed that TCFL5-Tx mice present lower expression levels of Dcaf17 although this was not statistically significant (Supplementary Fig. 7D). In addition, we also wanted to study other important genes for spermatogenesis such as Sox2, Dalz and Dmrt1. All these genes were upregulated in TCFL5−/− mice suggesting that TCFL5 could act as a negative regulator of these genes (Supplementary Fig. 7E).

To address if TCFL5 could regulate directly these genes more than only correlate, we search for the described TCFL5 binding motif (CACGCG) in the promoter of some of those genes14. We found that Dazl, Dmrt1, Stag3, Syce1, Dcaf17, and Spata16 presented potential TCFL5 binding sites (Supplementary Fig. 7F), indicating a possible direct transcriptional control by TCFL5. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis confirmed that TCFL5 binds to the Dazl, Dmrt1, and Syce1 promoters (Supplementary Fig. 7G,H) suggesting a direct control of these genes by TCFL5.

Discussion

Although TCFL5 was initially identified in human testis13, its role during spermatogenesis has been scarcely studied. In humans, TCFL5 protein expression has been described in primary and secondary spermatocytes and round spermatids19,30. However, there is no consensus on its expression pattern in testis in mice. Siep M. et al. described TCFL5 expression in spermatocytes14, while Shi et al. found it in elongating spermatids17. They explain this difference by attending to the possible presence of several isoforms. Our analysis of the available genetics database indicates at least 4 potential different mRNA isoforms for Tcfl5 in mice. However, our detailed analysis of the transcripts’ expression levels shows that only one mRNA isoform is present in the testicular extract. Furthermore, our immunofluorescence analyses confirm its presence in primary spermatocytes. Specifically, TCFL5 expression appears in the pachytene stage and presents the maximum expression in the diplotene stage. Reduced TCFL5 expression was detected in the following stages of spermatogenesis. This isoform and its expression agree with those described by Siep et al. Indeed, the main effect of TCFL5 knockout mice in spermatogenesis is found in pachytene/diplotene stages. Nonetheless, TCFL5 deficiency also affects spermatids. We described a lower and located expression of TCFL5 at the top of flagellum of spermatids concordant to Shi et al.17.

Regarding meiosis, TCFL5−/− spermatocytes reach a diplotene-like stage, being unable to resolve it and producing cell arrest. SYCP3, SYCP1, H1t, and γH2AX expression revealed that TCFL5−/− cells enter diplotene phase and MLH1 expression showed a higher number of the chiasma points. Even though chromosome desynapsis starts, cells are not able to complete the process. Furthermore, chromosomes at this stage do not correctly condense. These events lead cells to a diplotene-like stage, which cannot be resolved, and spermatocytes finally collapse and die. These results showed a complete block of meiosis impeding the spermatid generation. Supporting this, we found that Tcfl5 is correlated to meiotic genes implicated in different aspects of the process, such as chromosome synapsis (Syce1), sister chromatid cohesion (Stag3), and chromatin remodelling (Morc2a). The expression of these genes in TCFL5 null mice was significantly increased. We found putative TCFL5 binding sites in Stag3, and Syce1 promoters. However, we only confirmed by ChIP the direct control of Syce1 by TCFL5. Altogether, these facts reveal that Syce1 expression is specifically induced by TCFL5 whereas Stag3 and Morc2a expression must be indirectly altered by TCFL5.

SYCE1 is a protein member of the synaptonemical complex31,32 and its deficiency produced meiosis arrest at the pachytene stages due to problems in chromosome synapsis7. In addition, STAG3 is a member of the meiotic cohesin complex allowing the correct chromosome segregation and is specifically expressed in spermatocytes associated to meiosis-specific synaptonemal complex33. In this case, STAG3 null mice produce a premature block in the zygotene stage of meiosis34–36. Our data indicate that these mice reach to pachytene stage with an apparently synaptonemal complex well formed. However, TCFL5 deficient mice present abnormal diplotene-like stages cells, which show the synaptonemal complex desynapsing in an anomalous way. All these data suggest that synaptonemal complex is correctly formed, but cells are not able to desynapse this complex and finally cells die. On the other hand, MORC2 is a member of the microrchidia (MORC) protein family, a chromatin-remodelling factor. Morc2 present two paralogues: Morc2a and Morc2b. Their physiological functions are still unknown but it has been described that MORC2B is also essential for meiosis allowing chromosome recombination37. In this sense, we have observed more MLH1 foci in TCFL5 KO than in WT, indicating a higher number of recombination sites. These results show that TCFL5 acts as a transcription factor regulating genes implicated in meiosis. Although a comprehensive analysis of transcriptome data from TCFL5 knockout is necessary, we propose that TCFL5 could regulate the meiotic transcriptome network and act as an essential transcription factor in the meiosis process as other proteins have been defined such as STRA8 or MEIOSIN38,39.

In TCFL5 null mice, diplotene-like stages keep inside the cysts and reach the epididymis where cells definitively die. That could be related to an alteration in cysts formation. Germ cells form nests of associated cells before entering meiosis, in order to generate interconnected, synchronous cell groups, known as cysts40. Taking into account that alterations in cysts formation and maturation could lead to sterility41,42, TCFL5 could play an important role in the regulation of pre-meiotic cysts formation.

Previously, TCFL5 has been described to interact with MEIG1 and SPAG16 in spermatids17,43. Indeed, Meig1 and Tcfl5 appeared in our most correlated genes list. Both proteins, MEIG1 and SPAG16, have been described as important proteins for spermatids maturation and sperm motility44–47. The fact that TCFL5 interacts with proteins implicated in sperm flagellum formation suggests that TCFL5 could have another role besides as a transcription factor. Our studies have revealed that spermiogenesis is also affected. Due to the striking effect of TCFL5 in meiosis, it is impossible to observe spermatids defects in complete TCFL5 knockout mice. For this reason, conditional TCFL5-Tx mice are a better approach. The induction of TCFL5 deficiency by tamoxifen in mature mice affects all cells present in the testis. A great percentage of spermatids presented rare shapes in these mice. Our analysis of correlation showed that some proteins required for sperm maturation and motility such as Dcaf17, Spata16, and Tekt3 are correlated to Tcfl5. In addition, Dcaf17, and Spata16 present putative TCFL5 binding sites in their promoter. All these proteins produce spermatids arrest, rare sperm shape, and infertility syndrome in humans48–52 suggesting a possible explanation for the spermatid phenotype of TCFL5 null mice. Along these lines, TCFL5 has been described as a regulator of Clgn gene, a chaperone expressed in spermatogenesis14. However, null mice for this protein do not have visible defects in spermatogenesis but the resulting sperm is not able to adhere to zona pellucida. In contrast to our results, it has been recently described that TCFL5+/− mice were infertile due to abnormal spermatids, and thus those authors were unable to generate, TCFL5−/− knock out mice53. The discrepancies with our results may lie in the genetic mechanism used to delete the gene. Nonetheless, we observed a similar defect in spermatids in TCFL5-TX mice.

Interestingly, germ cell maintenance gen Sox254, Dmrt1 and Dalz are increased in TCFL5 knockout mice. In this regard, we observed that TCFL5 negatively regulates SOX2 in human tumor cells55. Thus, it is possible that the constant expression of Sox2 blocks meiosis activating germ cell maintenance signals. Indeed, Dmrt1 is also increased in TCFL5−/− mice and it has been described to be necessary for mitosis maintenance and its loss leads to meiosis entry56,57. Moreover, TCFL5 and DMRT1 have been reported to have an opposite expressions19 and we found that TCFL5 binds to Dmrt1 promoter, suggesting that TCFL5 could be a transcriptional repressor of its expression. In agreement with this repressive role of TCFL5, a comprehensive functional enrichment analysis of male infertility, both in mouse models and in humans has found increased levels of Tcfl558. Although this result may result contradictory, these models are related to Etv5, Pou3f1, and Bcl6b genes which are implicated in the spermatogonial stem cell renewal, being these mice sterile due to a loss of spermatogonia59,60. Thus, Tcfl5 induction could be related to the lack of mitotic maintenance signals that would repress Tcfl5 expression. Dazl is considered a master regulator of spermatogenesis and it is also induced by TCFL5 deficiency and TCFL5 also bound to its promoter. Dazl is required for correct progression through all processes, being one of its functions the spermatogonial stem cells maintenance61.

Here, we described the phenotype caused by TCFL5 deficiency, affecting mouse spermatogenesis. TCFL5 knockout results in azoospermia due to an arrest in the first meiotic prophase at the diplotene stage and conditional TCFL5-Tx results in the generation of abnormal spermatids. Altogether, our results demonstrate that TCFL5 is an essential transcription factor in those processes, involved in both meiosis resolution and spermatids maturation. Thus, TCFL5 binds to the promoter of some important genes in those processes suggesting a direct control of their expression, either inhibiting spermatogonia maintenance genes or activating meiosis genes and may play a master switch role. Overall, TCFL5 phenotype in spermatogenesis could be explained by attending to all these effects. Thus, TCFL5 may be a master regulator controlling several key steps in spermatogenesis.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to María Chorro and Beatriz Barrocal for their technical assistance. SOX2-Cre and CRE-ERTM mice were a kind gift from Dr. Cesar Cobaleda (Centro de Biología Molecular Severo Ochoa) and the guinea pig anti-H1t antibody was kindly provided by Dr. Jesús Page (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid).

Author contributions

J.G.-M., I.B., and M.C.M. performed the experiments. J.G.-M, I.B., K.S., N.G. and M.F. designed the study and analyzed the data. J.G.-M., I.B., and M.F. wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from “Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación” (SAF2016-75988-R and PID2019-104760RB-I00) “Comunidad de Madrid (S2017/BMD-3671. INFLAMUNE-CM), Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias” (BIOIMID) to M.F and Institutional grants from “Fundación Ramón Areces” and “Banco de Santander”.

Data availability

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. Mice Tcfl5 sequences used in this study are deposited in NCBI (Accession number: 277353, NM_178254.3, BC108399.1, XM_006500653.1, AK132721.1, AY234363.1 and XM_006500652.1), Ensemble (Accession number: ENSMUST00000131881, ENSMUST0000037877, ENSMUST00000131881, ENSMUST00000161425), Vega (Accession number: OTTMUSG00000016345, OTTMUST00000039295, OTTMUST0000086954) and Uniprot (Accession number: Q32NY8, Q3V133, Q810E9, ESQ5K1) databases. Functional categories, gene ontology and correlation analysis in this database was performed 2020/04/15 and can be found here: ARCHS4 website, https://maayanlab.cloud/archs4/. Original gels/blots are available in Supplementary Fig. 8.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-15167-w.

References

- 1.Cheng CY, Mruk DD. The biology of spermatogenesis: The past, present and future. Philos. Trans. R Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010;365(1546):1459–1463. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mei XX, Wang J, Wu J. Extrinsic and intrinsic factors controlling spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Asian J. Androl. 2015;17(3):347–354. doi: 10.4103/1008-682X.148080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oatley JM, Avarbock MR, Telaranta AI, Fearon DT, Brinster RL. Identifying genes important for spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal and survival. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103(25):9524–9529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603332103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen C, Ouyang W, Grigura V, Zhou Q, Carnes K, Lim H, et al. ERM is required for transcriptional control of the spermatogonial stem cell niche. Nature. 2005;436(7053):1030–1034. doi: 10.1038/nature03894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Griswold MD. Spermatogenesis: The commitment to meiosis. Physiol. Rev. 2015;96(1):1–17. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schramm S, Fraune J, Naumann R, Hernandez-Hernandez A, Höög C, Cooke HJ, et al. A novel mouse synaptonemal complex protein is essential for loading of central element proteins, recombination, and fertility. PLoS Genet. 2011;7(5):e1002088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bolcun-Filas E, Hall E, Speed R, Taggart M, Grey C, de Massy B, et al. Mutation of the mouse Syce1 gene disrupts synapsis and suggests a link between synaptonemal complex structural components and DNA repair. PLoS Genet. 2009;5(2):e1000393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O'Donnell L. Mechanisms of spermiogenesis and spermiation and how they are disturbed. Spermatogenesis. 4(2), e979623. 10.4161/21565562.2014.979623 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Page SL, Hawley RS. The genetics and molecular biology of the synaptonemal complex. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2004;20:525–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.19.111301.155141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Handel MA, Schimenti JC. Genetics of mammalian meiosis: Regulation, dynamics and impact on fertility. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11(2):124–136. doi: 10.1038/nrg2723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toyoda S, Yoshimura T, Mizuta J, Miyazaki J. Auto-regulation of the Sohlh1 gene by the SOHLH2/SOHLH1/SP1 complex: Implications for early spermatogenesis and oogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(7):e101681. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hsu SH, Hsieh-Li HM, Li H. Dysfunctional spermatogenesis in transgenic mice overexpressing bHLH-Zip transcription factor, Spz1. Exp. Cell Res. 2004;294(1):185–198. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maruyama O, Nishimori H, Katagiri T, Miki Y, Ueno A, Nakamura Y. Cloning of TCFL5 encoding a novel human basic helix-loop-helix motif protein that is specifically expressed in primary spermatocytes at the pachytene stage. Cytogenet. Cell Genet. 1998;82(1–2):41–45. doi: 10.1159/000015061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siep M, Sleddens-Linkels E, Mulders S, van Eenennaam H, Wassenaar E, Van Cappellen WA, et al. Basic helix–loop–helix transcription factor Tcfl5 interacts with the Calmegin gene promoter in mouse spermatogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(21):6425–6436. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikawa M, Wada I, Kominami K, Watanabe D, Toshimori K, Nishimune Y, et al. The putative chaperone calmegin is required for sperm fertility. Nature. 1997;387(6633):607–611. doi: 10.1038/42484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ikawa M, Nakanishi T, Yamada S, Wada I, Kominami K, Tanaka H, et al. Calmegin is required for fertilin alpha/beta heterodimerization and sperm fertility. Dev. Biol. 2001;240(1):254–261. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Y, Zhang L, Song S, Teves ME, Li H, Wang Z, et al. The mouse transcription factor-like 5 gene encodes a protein localized in the manchette and centriole of the elongating spermatid. Andrology. 2013;1(3):431–439. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-2927.2013.00069.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li W, Tang W, Teves ME, Zhang Z, Zhang L, Li H, et al. A MEIG1/PACRG complex in the manchette is essential for building the sperm flagella. Development. 2015;142(5):921–930. doi: 10.1242/dev.119834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth LM, Michal M, Michal M, Cheng L. Protein expression of the transcription factors DMRT1, TCLF5, and OCT4 in selected germ cell neoplasms of the testis. Hum. Pathol. 2018;82:68–75. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters AH, Plug AW, van Vugt MJ, de Boer P. A drying-down technique for the spreading of mammalian meiocytes from the male and female germline. Chromosome Res. 1997;5(1):66–68. doi: 10.1023/A:1018445520117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Page J, Suja JA, Santos JL, Rufas JS. Squash procedure for protein immunolocalization in meiotic cells. Chromosome Res. 1998;6(8):639–642. doi: 10.1023/A:1009209628300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gaysinskaya V, Bortvin A. Flow cytometry of murine spermatocytes. Curr. Protoc. Cytom. 2015;72:7.44.1–7.44.24. doi: 10.1002/0471142956.cy0744s72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gómez-del Arco P, Kashiwagi M, Jackson AF, Naito T, Zhang J, Liu F, et al. Alternative promoter usage at the Notch1 locus supports ligand-independent signaling in T cell development and leukemogenesis. Immunity. 2010;33(5):685–698. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hayashi S, Lewis P, Pevny L, McMahon AP. Efficient gene modulation in mouse epiblast using a Sox2Cre transgenic mouse strain. Mech. Dev. 2002;119(Suppl 1):S97–101. doi: 10.1016/S0925-4773(03)00099-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi S, McMahon AP. Efficient recombination in diverse tissues by a tamoxifen-inducible form of Cre: A tool for temporally regulated gene activation/inactivation in the mouse. Dev. Biol. 2002;244(2):305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Froenicke L, Anderson LK, Wienberg J, Ashley T. Male mouse recombination maps for each autosome identified by chromosome painting. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;71(6):1353–1368. doi: 10.1086/344714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lachmann A, Torre D, Keenan AB, Jagodnik KM, Lee HJ, Wang L, Silverstein MC, Ma'ayan A. Massive mining of publicly available RNA-seq data from human and mouse. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1366. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03751-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Bioinformatics enrichment tools: Paths toward the comprehensive functional analysis of large gene lists. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(1):1–13. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4(1):44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn J, Park YJ, Chen P, Lee TJ, Jeon YJ, Croce CM, et al. Comparative expression profiling of testis-enriched genes regulated during the development of spermatogonial cells. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(4):e0175787. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costa Y, Speed R, Öllinger R, Alsheimer M, Semple CA, Gautier P, et al. Two novel proteins recruited by synaptonemal complex protein 1 (SYCP1) are at the centre of meiosis. J. Cell Sci. 2005;118(12):2755–2762. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dunne OM, Davies OR. Molecular structure of human synaptonemal complex protein SYCE1. Chromosoma. 2019;128(3):223–236. doi: 10.1007/s00412-018-00688-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lara-Pezzi E, Pezzi N, Prieto I, Barthelemy I, Carreiro C, Martínez A, et al. Evidence of a transcriptional co-activator function of cohesin STAG/SA/Scc3. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(8):6553–6559. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Llano E, Gomez-H L, García-Tuñón I, Sánchez-Martín M, Caburet S, Barbero JL, et al. STAG3 is a strong candidate gene for male infertility. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014;23(13):3421–3431. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Bijl N, Röpke A, Biswas U, Wöste M, Jessberger R, Kliesch S, et al. Mutations in the stromal antigen 3 (STAG3) gene cause male infertility due to meiotic arrest. Hum. Reprod. 2019;34(11):2112–2119. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dez204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Winters T, McNicoll F, Jessberger R. Meiotic cohesin STAG3 is required for chromosome axis formation and sister chromatid cohesion. EMBO J. 2014;33(11):1256–1270. doi: 10.1002/embj.201387330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shi, B., Xue, J., Zhou, J., Kasowitz, S.D., Zhang, Y., Liang, G., et al. MORC2B is essential for meiotic progression and fertility. 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Ishiguro KI, Matsuura K, Tani N, Takeda N, Usuki S, Yamane M, et al. MEIOSIN directs the switch from mitosis to meiosis in mammalian germ cells. Dev. Cell. 2020;52(4):429–445.e10. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kojima ML, de Rooij DG, Page DC. Amplification of a broad transcriptional program by a common factor triggers the meiotic cell cycle in mice. Elife. 2019;8:e43738. doi: 10.7554/eLife.43738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Matova N, Cooley L. Comparative aspects of animal oogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2001;231(2):291–320. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.0120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenbaum MP, Iwamori T, Buchold GM, Matzuk MM. Germ cell intercellular bridges. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2011;3(8):a005850. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a005850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Greenbaum MP, Iwamori N, Agno JE, Matzuk MM. Mouse TEX14 is required for embryonic germ cell intercellular bridges but not female fertility. Biol. Reprod. 2009;80(3):449–457. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.070649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Z, Shen X, Jones BH, Xu B, Herr JC, Strauss JF. Phosphorylation of mouse sperm axoneme central apparatus protein SPAG16L by a testis-specific kinase, TSSK2. Biol. Reprod. 2008;79(1):75–83. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.066308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Z, Shen X, Gude DR, Wilkinson BM, Justice MJ, Flickinger CJ, et al. MEIG1 is essential for spermiogenesis in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(40):17055–17060. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906414106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z, Kostetskii I, Tang W, Haig-Ladewig L, Sapiro R, Wei Z, et al. Deficiency of SPAG16L causes male infertility associated with impaired sperm motility. Biol. Reprod. 2006;74(4):751–759. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.049254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan N, Pelletier D, McAlear TS, Croteau N, Veyron S, Bayne AN, et al. Crystal structure of human PACRG in complex with MEIG1 reveals roles in axoneme formation and tubulin binding. Structure. 2021;29(6):572–586.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2021.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li W, Huang Q, Zhang L, Liu H, Zhang D, Yuan S, et al. A single amino acid mutation in the mouse MEIG1 protein disrupts a cargo transport system necessary for sperm formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2021;297(5):101312. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2021.101312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ali A, Mistry BV, Ahmed HA, Abdulla R, Amer HA, Prince A, et al. Deletion of DDB1- and CUL4-associated factor-17 (Dcaf17) gene causes spermatogenesis defects and male infertility in mice. Sci. Rep. 2018;8(1):9202. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27379-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dam AHDM, Koscinski I, Kremer JAM, Moutou C, Jaeger AS, Oudakker AR, et al. Homozygous mutation in SPATA16 is associated with male infertility in human globozoospermia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2007;81(4):813–820. doi: 10.1086/521314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujihara, Y., Oji, A., Larasati, T., Kojima-Kita, K., Ikawa, M. Human globozoospermia-related gene Spata16 is required for sperm formation revealed by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated mouse models. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 18(10) (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Roy A, Lin YN, Agno JE, DeMayo FJ, Matzuk MM. Tektin 3 is required for progressive sperm motility in mice. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009;76(5):453–459. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhao Y, Gao N, Li X, El-Ashram S, Wang Z, Zhu L, et al. Identifying candidate genes associated with sperm morphology abnormalities using weighted single-step GWAS in a Duroc boar population. Theriogenology. 2020;1(141):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2019.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu, W., Zhang, Y., Qin, D., Gui, Y., Wang, S., Du, G., et al. Transcription factor-like 5 is a potential DNA/RNA-binding protein essential for maintaining male fertility in mice. J. Cell Sci. jcs.259036 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Ibtisham F, Wu J, Xiao M, An L, Banker Z, Nawab A, et al. Progress and future prospect of in vitro spermatogenesis. Oncotarget. 2017;8(39):66709–66727. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galán-Martínez, J., Stamatakis, K., Sánchez-Gómez, I., Vázquez-Cuesta, S., Gironés, N., Fresno, M. Isoform-specific effects of transcription factor TCFL5 on the pluripotency-related genes SOX2 and KLF4 in colorectal cancer development. Mol. Oncol. (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Matson CK, Murphy MW, Griswold MD, Yoshida S, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. The mammalian doublesex homolog DMRT1 is a transcriptional gatekeeper that controls the mitosis versus meiosis decision in male germ cells. Dev. Cell. 2010;19(4):612–624. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang T, Oatley J, Bardwell VJ, Zarkower D. DMRT1 is required for mouse spermatogonial stem cell maintenance and replenishment. PLoS Genet. 2016;12(9):e1006293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Razavi SM, Sabbaghian M, Jalili M, Divsalar A, Wolkenhauer O, Salehzadeh-Yazdi A. Comprehensive functional enrichment analysis of male infertility. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):15778. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu X, Goodyear SM, Tobias JW, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL. Spermatogonial stem cell self-renewal requires ETV5-mediated downstream activation of Brachyury in Mice1. Biol. Reprod. 2011;85(6):1114–1123. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.111.091793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jamsai D, Clark BJ, Smith SJ, Whittle B, Goodnow CC, Ormandy CJ, et al. A missense mutation in the transcription factor ETV5 leads to sterility, increased embryonic and perinatal death, postnatal growth restriction, renal asymmetry and polydactyly in the mouse. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(10):e77311. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, Liang Z, Yang J, Wang D, Wang H, Zhu M, et al. DAZL is a master translational regulator of murine spermatogenesis. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2019;6(3):455–468. doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwy163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are publicly available. Mice Tcfl5 sequences used in this study are deposited in NCBI (Accession number: 277353, NM_178254.3, BC108399.1, XM_006500653.1, AK132721.1, AY234363.1 and XM_006500652.1), Ensemble (Accession number: ENSMUST00000131881, ENSMUST0000037877, ENSMUST00000131881, ENSMUST00000161425), Vega (Accession number: OTTMUSG00000016345, OTTMUST00000039295, OTTMUST0000086954) and Uniprot (Accession number: Q32NY8, Q3V133, Q810E9, ESQ5K1) databases. Functional categories, gene ontology and correlation analysis in this database was performed 2020/04/15 and can be found here: ARCHS4 website, https://maayanlab.cloud/archs4/. Original gels/blots are available in Supplementary Fig. 8.