Abstract

Soil treated with linuron for more than 10 years showed high biodegradation activity towards methoxy-methyl urea herbicides. Untreated control soil samples taken from the same location did not express any linuron degradation activity, even after 40 days of incubation. Hence, the occurrence in the field of a microbiota having the capacity to degrade a specific herbicide was related to the long-term treatment of the soil. The enrichment culture isolated from treated soil showed specific degradation activity towards methoxy-methyl urea herbicides, such as linuron and metobromuron, while dimethyl urea herbicides, such as diuron, chlorotoluron, and isoproturon, were not transformed. The putative metabolic intermediates of linuron and metobromuron, the aniline derivatives 3,4-dichloroaniline and 4-bromoaniline, were also degraded. The temperature of incubation drastically affected degradation of the aniline derivatives. Whereas linuron was transformed at 28 and 37°C, 3,4-dichloroaniline was transformed only at 28°C. Monitoring the enrichment process by reverse transcription-PCR and denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) showed that a mixture of bacterial species under adequate physiological conditions was required to completely transform linuron. This research indicates that for biodegradation of linuron, several years of adaptation have led to selection of a bacterial consortium capable of completely transforming linuron. Moreover, several of the putative species appear to be difficult to culture since they were detectable by DGGE but were not culturable on agar plates.

Contamination of surface water and groundwater by pesticides is a major environmental concern. General agricultural application of pesticides and point locations (e.g., rinsate wastes from farming operations) are important sources of contamination. In addition, many pesticide-formulating retailers have sites sufficiently contaminated to qualify as Superfund sites (11, 18). Phenylurea herbicides are among the most widely used herbicides in noncrop areas, as well as in tree crops (20). Given the potential carcinogenic risk of these herbicides (12, 17), there is a serious need to develop remediation processes to eliminate or minimize contamination of surface water and groundwater. Biodegradation could be a reliable and cost-effective technique for pesticide abatement. In this context, I isolated an enrichment culture capable of degrading the herbicide linuron and 3,4-dichloroaniline (3,4-DCA). The latter is considered the main intermediate metabolite in the degradation of several herbicides. The enrichment culture was derived from an orchard that was regularly treated with linuron for more than 10 years. Samples of untreated soil collected from the same location did not express any degradation activity (5). In the current study denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) was used to monitor bacterial populations in the enrichment cultures over time and in response to different physiological conditions, such as the temperature of incubation and the composition of the culture medium. Application of DGGE in microbial ecology has attracted great interest in the last few years (10). This technique is suitable for studying and monitoring enrichment cultures (6, 15, 22). Teske et al. (19) have used DGGE to identify the bacterial composition of a coculture capable of sulfate reduction after exposure to oxic and microoxic conditions. DGGE was used to show changes in bacterial species composition in enrichment cultures prepared with various dilutions of inoculum (6). The aim of the present study was to understand the enrichment process with bacterial strains capable of degrading the herbicide linuron and its intermediate metabolite 3,4-DCA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Soil.

Soil samples were taken from the Royal Research Station of Gorsem (Sint-Truiden, Belgium), an orchard that has been regularly treated with different urea herbicides since 1987. Details of the soil properties and the soil-sampling procedures have been described previously (5).

Enrichment cultures.

Five grams of soil was added to 95 ml of minimal medium containing (per liter of MilliQ water) 93.50 mg of MgSO4 · 6H2O, 5.88 mg of CaCl2 · 2H2O, 1.15 mg of ZnSO4 · 7H2O, 1.16 mg of H3BO3, 1.69 mg of MnSO4 · H2O, 0.24 mg of CoCl2 · 6H2O, 0.10 mg of MoO3, 2.78 mg of FeSO4 · 7H2O, and 0.37 mg of CuSO4 · 5H2O. The pH was adjusted to about 7.0 by using a phosphate buffer (10 mM KH2PO4, 10 mM Na2HPO4). Linuron was added as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen. The concentration of linuron in the enrichment medium was initially 25 mg/liter and was gradually increased in subsequent flasks to a maximum of 500 mg/liter. The first enrichment cultures were inoculated with soil treated with linuron or with the untreated soil. The other pesticides tested were diuron, chlorotoluron, metobromuron, and isoproturon, each at a concentration of 25 mg/liter. 3,4-DCA was also tested at a concentration of 25 mg/liter.

The disappearance of herbicides was monitored by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. The HPLC system consisted of a Kontron liquid chromatograph equipped with a DEGASYS DG-1310 system to degas the mobile phase, three Kontron 325 high-pressure pumps, a Kontron MSI 660 injector with a 20-μl loop, a Kontron DAD 495 diode array detector, and a 450 MT2/DAD software system. The column was a Hypersil Green Environment 5U column (Alltech, Deerfield, Ill.). The mobile phase was CH3OH–0.1 M NH4H2PO4 (pH 3.8) (70:30), the flow rate was 0.8 ml/min, and the UV detector was set at 210 nm. Products were identified by comparison with authentic standards.

Nucleic acid extraction and PCR amplification.

DNA extraction from soil and PCR amplification of 16S rRNA genes with the primers set (primers P63 and P518) were performed by using the protocols described previously (4, 5). Colonies isolated on agar plates were boiled for 10 min in 200 μl of Milli-Q water before the PCR was performed. For liquid enrichment cultures, RNA extraction was performed with TRIZOL (Life Technologies, Rockville, Md.) used according to the manufacturer's instructions. Reverse transcription (RT)-PCR was performed with rTh DNA polymerase and a buffer kit obtained from Perkin-Elmer. The RT reaction mixtures (20 μl) contained 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 90 mM KCl, 1 mM MnCl2, each deoxynucleoside triphosphate at a concentration of 200 μM 0.75 μM primer P518 (7), and 5 U of rTh DNA polymerase. After addition of 1 μl of an RNA sample to each mixture, the mixtures were incubated for 15 min at 70°C. Following the RT reaction, 80 μl of each PCR mixture, containing 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.3), 100 mM KCl, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.75 mM ethylene bis(oxyethylenenitrilo)tetraacetic acid, 5% (vol/vol) glycerol, and 0.15 μM primer P63-GC (5), was added. The samples were amplified by using 35 cycles consisting of 95°C for 10 s plus 60°C for 15 s. The reaction was stopped after incubation at 7 min at 60°C.

DGGE.

DGGE analyses were based on the protocol described previously (5). The polyacrylamide gels were made with a 40 to 55% denaturant gradient (100% denaturant contained 7 M urea and 40% [vol/vol] formamide). Electrophoresis was performed overnight at 60°C and 45 V. DNA fragments were excised from each DGGE gel and sequenced as previously described (5).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Enrichment of a microbial culture that degrades linuron.

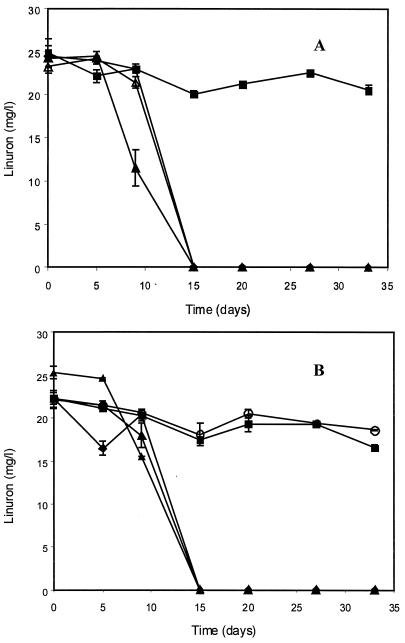

Five grams of soil that was either treated with linuron or not treated was inoculated into liquid medium containing 25 mg of linuron per liter. Whereas total transformation of linuron was observed in enrichments inoculated with treated soil, no disappearance of this herbicide was seen in enrichments inoculated with untreated soil (Fig. 1). The results were highly reproducible as the samples collected in March 1998 and August 1998 gave the same results (Fig. 1). Mixing treated and untreated soil samples in different proportions showed that the degradation ability was found only in the treated soil. In addition, autoclaved samples of the treated soil did not express any degradation activity, which clearly indicated the biological origin of the degradation capacity (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Transformation of linuron in enrichment cultures inoculated with linuron-treated and untreated soil samples obtained in May 1998 (A) and August 1998 (B). Flasks were inoculated with 5 g of untreated soil (▪), 5 g of linuron-treated soil (▴), 1 g of linuron-treated soil plus 4 g of untreated soil (▵), 0.1 g of linurom-treated soil plus 4.9 g of untreated soil (♦), and 5 g of autoclaved linuron-treated soil (○). The error bars indicate standard deviations based on triplicate measurements. Where they are not visible, the error bars are smaller than the symbol.

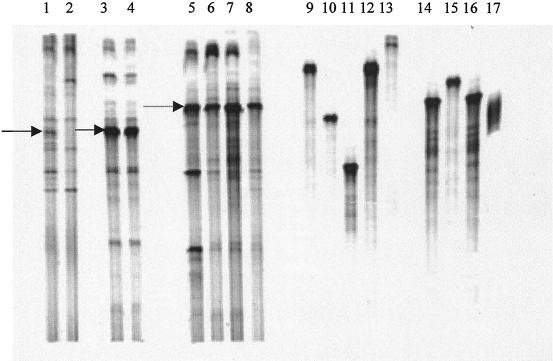

DGGE fingerprints of 10-day-old enrichment cultures inoculated with linuron-treated soil and untreated soil are shown in Fig. 2 (lanes 1 and 2). Differences in band patterns suggested that some species became more prevalent in the linuron-degrading culture. After several transfers into minimal medium containing linuron as the sole source of carbon and nitrogen, a stable DGGE fingerprint was obtained. The DGGE patterns obtained after RT-PCR, which targets more active bacteria with high rRNA contents, indicated that after several transfers there was still substantial diversity in the enriched bacterial consortium (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4). The enrichment culture was plated on several different solid media, including nutrient agar, (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.), R2A medium (Difco), minimal medium containing linuron as the sole carbon and nitrogen source (MMNL), and minimal medium without any carbon or nitrogen source (MMN0). The DGGE fingerprints of the colony mixtures recovered from each solid medium by resuspension in 2 ml of saline solution are shown in Fig. 2, lanes 5 through 8. There was a difference between the pattern obtained with the liquid culture (Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4) and the patterns obtained with the various solid media (Fig. 2, lanes 5 through 8). Indeed, the most intense DGGE fragments detected in liquid medium (e.g., the fragment corresponding to the Variovorax paradoxus-like strain [Fig. 2, lanes 3 and 4]) were not detected with the colonies which grew on solid media (Fig. 2, lanes 5 through 8). On the other hand, species that were absent in the liquid medium became very abundant after plating and appeared to be Pseudomonas putida-like (Fig. 2, lanes 5 through 8). Moreover, the diversity of the enrichment cultures on solid media, as estimated by the number of DGGE bands, decreased compared with the diversity of the liquid enrichment cultures. Interestingly, the resuspended colony mixtures were unable to degrade linuron, whereas the liquid culture degraded the herbicide completely within 4 days. It is important to note that MMN0 was prepared with several pure agar and agarose solidifying agents, including Noble agar (Difco), Ultrapure agarose (Life Technologies, Paisely, Scotland), and electrophoresis grade agarose (ICN Biomedicals Inc., Aurora, Ohio). Despite these efforts there was always a background of bacterial colonies on all MMN0 plates.

FIG. 2.

Lanes 1 and 2, DGGE fingerprints of the first enrichment cultures inoculated with linuron-treated and untreated soil, respectively; lanes 3 and 4, duplicate DGGE fingerprints of the bacterial culture that degraded linuron after 15 transfers; lanes 5 through 8, DGGE fingerprints of mixed bacterial colonies recovered from different solid media (nutrient agar, R2A agar, MMNL, and MMN0, respectively); lanes 9 through 17, DGGE fragments corresponding to different strains isolated on R2A agar. Solid and dashed arrows indicate fragments that correspond to fragments of Variovorax species (97%) and P. putida (99%), respectively.

Separate colonies, which were subjected to DGGE (Fig. 2, lanes 9 through 17), were also picked and tested to determine their capacity to degrade linuron. None of the isolated colonies, either separately or in artificial combinations, were capable of degrading linuron. This work showed that a shift in microbial community structure during transfer from successful liquid enrichment cultures to solid media could explain the failure to easily isolate individual strains that degrade herbicides. To my knowledge, this is the first report that shows a clear plating bias during enrichment of herbicide-degrading bacteria. Similarly, using an in situ hybridization technique, Wagner et al. (21) showed that probing activated sludge with oligonucleotides specific for the Proteobacteria reveals the inadequacy of culture-dependent methods for describing microbial communities, since culture-dependent community structure analysis of activated sludge produced partially to heavily biased results.

Many reports have indicated that degradation of herbicides requires mixed bacterial cultures (1, 2, 7, 8, 16). This explains the difficulties encountered by several groups in isolating pure cultures of herbicide-degrading strains. An illustration comes from the study of Roberts et al. (14), who tried to isolate pure strains capable of degrading linuron from an enrichment culture able to do so. These authors reported that none of the isolates on mineral medium with linuron or any synthetic mixture of isolates from the mixed culture degraded the compound. Thus, it was suggested that some carryover of nutrients occurred during the plating procedures. Nonetheless, after years of unsuccessful efforts, a pure strain that is capable of transforming diuron to 3,4-DCA was isolated recently (3), and several strains that degrade atrazine have also been isolated in recent years (9, 13). An intriguing point gleaned from studies of mixed and pure cultures is that most identified bacteria with a key role in degrading herbicides belong to the genus Pseudomonas and are species which generally grow easily on solid media. The ubiquity of pseudomonads in degradation processes has been attributed to a great diversity of exchangeable genetic elements in this genus; these elements are both plasmid borne and genomic and carry catabolic genes. Almost a decade ago, Sayler et al. (16) stated that one of the reasons why the majority of catabolic plasmid-bearing strains that had been studied so far were Pseudomonas-like species could be the enrichment and isolation methods used, which favored the growth of pseudomonads.

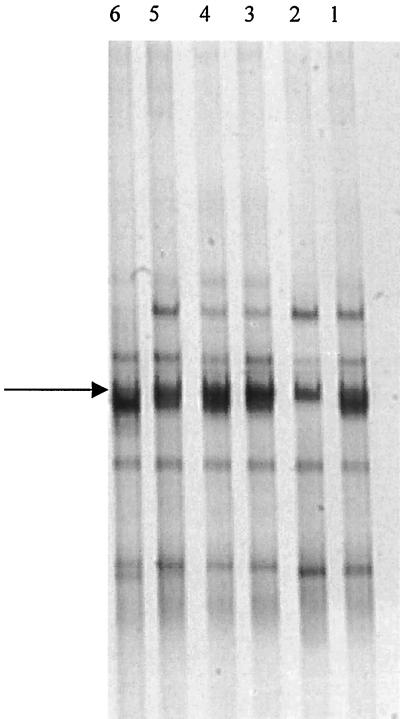

In an attempt to isolate a pure strain, serial liquid dilution series were prepared by using MMNL. Dilutions ranging from 100 to 10−10 were incubated at 28°C for more than 2 months with 25 mg of linuron per liter as the only source of carbon and nitrogen. The degradation of linuron was monitored regularly, and the dilutions that showed total transformation of linuron were subjected to DGGE analysis. The results indicated that no degradation occurred at dilutions beyond the 10−5 dilution. Thus, only 100 to 10−5 dilutions were subjected to DGGE analysis after complete degradation of linuron. Figure 3 shows that stable, similar mixtures of DGGE bands were obtained with all dilutions except the 10−5 dilution, in which one DGGE band seemed to disappear.

FIG. 3.

Lanes 1 through 6, DGGE fingerprints for serial dilutions ranging from 100 to 10−5, respectively. The arrow indicates the fragment corresponding to Variovorax-like species.

Effect of temperature on degradation of linuron.

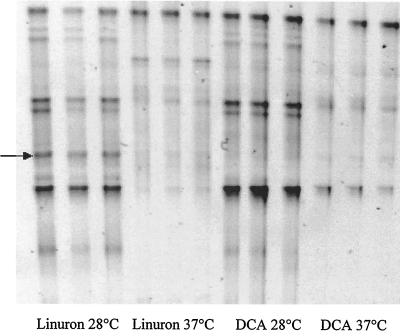

In addition to molecular monitoring of the enrichment culture, the effect of temperature on transformation of linuron was investigated. During enrichment, which was always carried out at 28°C, no intermediate metabolites were detected in the enrichments that degraded linuron. However, when the temperature of incubation was changed, HPLC analyses showed the appearance of an intermediate metabolite that had the same retention time as 3,4-DCA. Figure 4 shows the effect of temperature on degradation of linuron and 3,4-DCA. 3,4-DCA appeared only at 4, 20, and 37°C. The rate of transformation of linuron by the mixed bacterial culture was affected at 20°C and decreased at 4°C. On the other hand, whereas no difference was noted for transformation of linuron at 28 and 37°C, transformation of 3,4-DCA was affected at 37°C. The mass balance for the aromatic ring showed 100% accumulation of 3,4-DCA when the temperature of incubation was shifted from 28 to 37°C. To confirm the finding that 3,4-DCA transformation was influenced by the temperature of incubation, the enrichment culture was inoculated into minimal medium with 3,4-DCA as sole carbon and nitrogen source. Total transformation of 25 mg of 3,4-DCA per liter was observed after 4 days of incubation at 28°C, whereas no significant disappearance was seen when samples were incubated at 37°C for 3 weeks. A similar effect was also observed with 4-bromoaniline, the intermediate metabolite of metobromuron (data not shown). These data suggest that different bacterial species are involved in the transformation of linuron and 3,4-DCA. This hypothesis was supported by the DGGE patterns obtained with liquid cultures incubated at 28 and 37°C with linuron or 3,4-DCA as the sole carbon and nitrogen source (Fig. 5). Certain DGGE bands, including the one corresponding to the Variovorax-like species (Fig. 5), disappeared at 37°C. The difference in the DGGE patterns observed with linuron and 3,4-DCA at different temperatures of incubation, together with the results of DGGE monitoring of dilution series (Fig. 3), in which similar mixtures of 16S ribosomal DNA genes were always detected after linuron degradation, strongly supports the hypothesis that several strains are involved in complete transformation of linuron. As no pure strain capable of complete mineralization of urea herbicides has been isolated so far, my findings, together with those of previous studies, support the concept that consortia are required for complete transformation of urea herbicides.

FIG. 4.

Effect of temperature on degradation of linuron and its intermediate metabolite 3,4-DCA by the enrichment culture. The error bars indicate standard deviations based on triplicate measurements. Where they are not visible, the error bars are smaller than the symbol.

FIG. 5.

Triplicate DGGE analyses of enrichment cultures incubated at 28 and 37°C with 25 mg of linuron per liter or of 3,4-DCA (DCA) per liter as the sole carbon and nitrogen source. The arrow indicates the fragment corresponding to Variovorax-like species.

Degradation of urea herbicides by the enrichment culture.

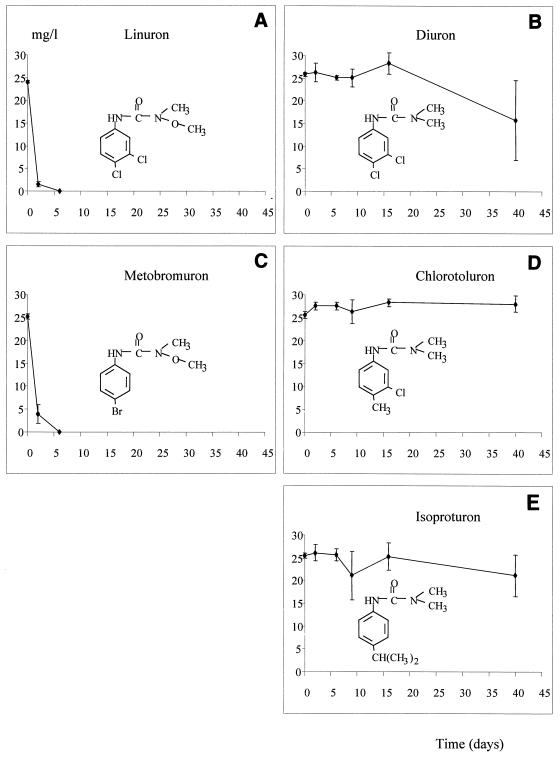

The ability of the enrichment culture to degrade several urea herbicides was also investigated. Figure 6 shows the time course degradation profiles for different urea herbicides. Herbicides that contain a methoxy-methyl amino group were rapidly degraded by the enrichment culture (Fig. 6A and C). In contrast, herbicides that contain a dimethyl-amino urea group were degraded slowly (Fig. 6B) or not at all (Fig. 6D and E).

FIG. 6.

Degradation of different urea herbicides by the enrichment culture.

The difference in degradation of different urea herbicides by the enrichment culture could be explained by the fact that different enzymes are involved in biotransformation of urea herbicides (5). Assuming that the first step consists of breaking the acylamide bond, it seems that there is a wide spectrum of aryl acyl amidases. I suggest that the enrichment culture used in this study contains a specific enzyme capable of transforming N′-methoxy-methyl urea herbicides, such as linuron and metobromuron. This enzyme seems not to be involved in transformation of 1,1-dimethyl urea herbicides, such as diuron, isoproturon, and chlorotoluron. The hypothesis that there are different enzymes involved in transformation of aryl acyl compounds is supported by the results obtained by Roberts et al. (14), who enriched a stable mixed bacterial culture capable of degrading the herbicide linuron. This culture was also able to degrade related herbicides, such as monolinuron, but was unable to degrade the 1,1-dimethyl-substituted urea compounds, such as monuron and diuron. However, it is important to note that the ring substituents may affect degradation capacity. The enrichment culture developed by Roberts et al. (14) was capable of degrading linuron but not metobromuron. The same result was obtained recently by Cullington and Walker (3), who showed that a single strain was able to transform diuron and linuron to 3,4-DCA but was not able to transform metobromuron. These authors suggested that ring chlorination, particularly at the 4 position, appears to greatly enhance rates of degradation. However, my results do not confirm this suggestion, since linuron and metobromuron were degraded at similar rates. Together, the data suggest that several pathways are most likely involved in biodegradation of urea herbicides.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grant G.O.A. 1997–2002 from the Ministerie van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap, Bestuur Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (Belgium).

I thank Siska Maertens for her excellent technical assistance and E. M. Top for her help in editing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Assaf N A, Turco R F. Accelerated biodegradation of atrazine by a microbial consortium is possible in culture and soil. Biodegradation. 1994;5:29–35. doi: 10.1007/BF00695211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook A M. Biodegradation of s-triazine xenobiotics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1987;46:93–116. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cullington J E, Walker A. Rapid biodegradation of diuron and other phenylurea herbicides by a soil bacterium. Soil Biol Biochem. 1999;31:677–686. [Google Scholar]

- 4.El Fantroussi S, Mahillon J, Naveau H, Agathos S N. Introduction and PCR detection of Desulfomonile tiedjei in soil microcosms. Biodegradation. 1997;8:125–133. doi: 10.1023/a:1008262426800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.El Fantroussi S, Verschuere L, Verstraete W, Top E M. Effect of phenylurea herbicides on soil microbial communities estimated by 16S rRNA gene fingerprints and community-level physiological profiles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:982–988. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.3.982-988.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson C R, Roden E E, Churchill P F. Changes in bacterial species composition in enrichment cultures with various dilutions of inoculum as monitored by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:5046–5048. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.12.5046-5048.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiménez L, Breen A, Thomas N, Federle T W, Sayler G S. Mineralization of linear alkylbenzene sulfonate by a four-member aerobic bacterial consortium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1566–1569. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.5.1566-1569.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lappin H M, Greaves M P, Slater J H. Degradation of the herbicide mecoprop [2-(2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxy)propionic acid] by a synergistic microbial community. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1985;49:429–433. doi: 10.1128/aem.49.2.429-433.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mandelbaum R T, Wackett L P, Allan D L. Isolation and characterization of a Pseudomonas sp. that mineralizes the s-triazine herbicide atrazine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:1451–1457. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.4.1451-1457.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muyzer G, Smalla K. Application of denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE) and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (TGGE) in microbial ecology. Antonie Leeuwenhoek J Microbiol. 1998;73:127–141. doi: 10.1023/a:1000669317571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Myrick C. Pesticide waste management: technology and regulation, from a symposium sponsored by the Division of Agrochemicals at the Fourth Chemical Congress of North America, New York, New York, 25–30 August 1991. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society; 1992. Site assessment and remediation for retail agrochemical dealers; pp. 224–233. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pasquini R, Scassellati-Sforzolini G, Dolara P, Pampanella L, Villarini M, Caderni G, Fazi-Fatigoni M C. Assay of linuron and a pesticide mixture commonly found in the Italian diet, for promoting activity in rat liver carcinogenesis. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;75:170–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1994.tb00342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Radosevich M, Traina S J, Hao Y, Tuovinen O H. Degradation and mineralization of atrazine by a soil bacterial isolate. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:297–301. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.1.297-302.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts S J, Walker A, Parekh N R, Welch S J, Waddington M J. Studies on a mixed bacterial culture from soil which degrades the herbicide linuron. Pestic Sci. 1993;39:71–78. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santegoeds C M, Nold S C, Ward D M. Denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis used to monitor the enrichment culture of aerobic chemoorganotrophic bacteria from a hot spring cyanobacterial mat. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:3922–3928. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.3922-3928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sayler G S, Hooper S W, Layton A C, Henry King J M. Catabolic plasmids of environmental and ecological significance. Microb Ecol. 1990;19:1–20. doi: 10.1007/BF02015050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scassellati-Sforzolini G, Pasquini R, Moretti M, Villarini M, Fatigoni C, Dolara P, Monarca S, Caderni G, Kuchenmeister F, Schmezer P, Pool-Zobel B L. In vivo studies on genotoxicity of pure and commercial linuron. Mutat Res. 1997;390:207–221. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(97)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shelton D R, Khader S, Karns J S, Pogell B M. Metabolism of twelve herbicides by Streptomyces. Biodegradation. 1996;7:129–136. doi: 10.1007/BF00114625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Teske A, Sigalevich P, Cohen Y, Muyzer G. Molecular identification of bacteria from a coculture by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of 16S ribosomal DNA fragments as a tool for isolation in pure cultures. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:4210–4215. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.11.4210-4215.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomlin C. The pesticide manual. 10th ed. Farnham, Surrey, United Kingdom: BCPC; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wagner M, Amann R, Lemmer H, Schleifer K H. Probing activated sludge with oligonucleotides specific for proteobacteria: inadequacy of culture-dependent methods for describing microbial community structure. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1520–1525. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1520-1525.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward D M, Ferris M J, Nold S C, Bateson M M. A natural view of microbial biodiversity within hot spring cyanobacterial mat communities. Microbiol Rev. 1998;62:1353–1370. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1353-1370.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]