Abstract

The inner ear is a complex and difficult organ to study, and sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is a multifactorial sensorineural disorder with characteristics of impaired speech discrimination, recognition, sound detection, and localization. Till now, SNHL is recognized as an incurable disease because the potential mechanisms underlying SNHL have not been elucidated. The risk of developing SNHL is no longer viewed as primarily due to environmental factors. Instead, SNHL seems to result from a complicated interplay of genetic and environmental factors affecting numerous fundamental cellular processes. The complexity of SNHL is presented as an inability to make an early diagnosis at the earliest stages of the disease and difficulties in the management of symptoms during the process. To date, there are no treatments that slow the neurodegenerative process. In this article, we review the recent advances about SHNL and discuss the complexities and challenges of prevention and intervention of SNHL.

Keywords: age-related hearing loss, genetics, noise-induced hearing loss, prevention and intervention of SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss

Introduction

Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is a common and complex sensorineural disorder with characteristics of impaired speech discrimination, recognition, sound detection, and localization. 1 SNHL has been recognized globally as an area of low and highly variable effective interventions and little systematic data for outcomes. SNHL is generally considered to be a multifactorial progressive disease resulting from complicated interplay of genetic and environmental factors. SNHL affects numerous fundamental cellular processes. 2 Numerous factors including hazardous noise exposure, ototoxic medications, otologic disease history, head trauma, vascular insults, metabolic changes, hormones, diet, and immune system factors are superimposed upon an intrinsic, genetically controlled process.3,4 In our review, we focus on the recent advances about the causes of SHNL and discuss the complexities and challenges of prevention and intervention of SNHL.

Causes of SNHL

Genetics

Genome mutation

Numerous studies have revealed that various predisposing genetic factors are responsible for the hereditary SNHL. 5 In addition, more than 100 gene mutations have been found to account for the onset of SNHL. Heritability studies have suggested that gene mutations contribute to the SNHL, including age-related hearing loss(ARHL). Gene mutations are one of the most common causes of early-onset SNHL. Hereditary SNHL is relatively common among newborns, affecting approximately 1 in 1000 live births. However, it is very difficult to evaluate the exact role of gene mutations in adult-onset SNHL due to the synergistic effect between gene mutations and environments. Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish whether a disabling SNHL is caused by genetic factors or noise, or even both. 6

Decades of studies have tried to illustrate the possible mechanisms of hereditary SNHL: (1) mutation in cdh23 gene is harmful to stereocilia tip link in the organ of Corti and can cause mechanoelectrical transduction dysfunction or even hair cell apoptosis from the base to the apex; 7 (2) some haplotypes of hsp70 genes may increase the susceptibility to noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL); 8 (3) a locus on distal chromosome 10 (ahl4) contributes to the early-onset, rapidly progressing SNHL because of its earlier and more severe hair cell loss, that is, these gene mutations make people susceptible to ARHL; 9 (4) Gipc3 gene mutations disrupt the structure of the stereocilia bundle, which in turn induces the disability of hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons. 10

Mitochondrial DNA mutation

Recent technological advancements in genetics have shown that somatic mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) are also linked to SNHL. 11 Due to the lack of the repair mechanism and histone proteins like genomic DNA, mtDNA is more susceptible to damage by reactive oxygen species (ROS). 12 ROS production results in mtDNA mutations, which in turn leads to SNHL. However, ROS inhibition is a promising strategy for ROS-related SNHL. 13 Thus, we may speculate that ROS-predisposed mtDNA mutations play a major role in the progression of SNHL.

Numerous investigations have been conducted to acknowledge the association between mitochondrial disorders and SNHL. 14 Particularly, the A1555G and C1494 T mutations were associated with both aminoglycoside-induced and non-syndromic hearing loss. 15 The results from animal experiments and human autopsy studies have suggested that somatic mtDNA mutations, such as A3243G, T5655 C, and A14692G, are considered to be a significant underlying factor in the progression of hearing loss. 16 However, mtDNA 4977-bp deletion also occurs in young people and in children with SNHL. Reports have indicated that mtDNA common deletion (CD) occurred not only in individuals with normal hearing but also in young people. The effect of the CD on ARHL is still poorly understood. Based on these controversial results, we propose that mtDNA mutations might also occur in people without ARHL and that CD might not directly induce ARHL. Therefore, the exact mechanism of mtDNA deletion on ARHL needs further basic and clinical studies.

Noise exposure

NIHL17,18 is one of the most common injury or disease in many occupations and recreational places, and it also contributes to the ototoxicity and progression of ARHL. 19 The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 1.2 billion teenagers and young adults aged 12–35 years are all susceptible to NIHL for various reasons, such as playing loud personal music, using firearms without hearing protection, and being exposed to loud sounds during recreational activities. Decades of research have shown that noise exposure results in anatomical, physiological, and neurochemical changes to the auditory system, which in turn lead to hair cell loss, primary auditory neuron damage, threshold elevation, and degraded frequency tuning.20–24 Patients exposed to noise may present with SNHL, tinnitus, and hyperacusis. The mechanisms underlying NIHL are the loss of hair cells, synaptopathy, primary auditory neurons, and lateral wall histopathology in the cochlea. However, hair cell loss could be detected within hours, while primary auditory neurons are thought to be a delayed downstream consequence of hair cell loss and may not be detected for years. 25

Exposure to intense noise can lead to temporary threshold shift (TTS) of which hearing function can fully recover to normal. In addition, it can also result in permanent threshold shift (PTS) which means that auditory acuity fails to restore to pre-exposure level. Ebselen, a novel GPx1 mimic, was safe and effective in preventing both temporary and permanent NIHL in preclinical studies. 26 A recent investigation showed that ribbon synapses and changes could be recovered by the overexpression of the gene encoding neurotrophin3 (Ntf3), which can elicit the regeneration of the synaptic contacts between cochlear nerve terminals and inner hair cells (IHCs). 27 These data confirmed that noised-induced damage is reversible and the study could pave the way for the clinical treatment of NIHL.

Aging

Aging is considered as one of the most important factors that lead to the degenerative processes of the auditory system, especially in adult-onset SNHL. ARHL is generally considered to be a multifactorial progressive disease caused not only by aging on the auditory system but also by the accumulated effects of other numerous factors, such as noise, ototoxic drugs, otologic disease history, trauma, vascular insults, metabolic changes, hormones, diet, and immune system that are superimposed upon an intrinsic, genetically controlled aging process.3,4 The Medline Plus Medical Encyclopedia estimated that ARHL is projected to affect 25% of people aged 65–75 years and 70–80% of people over the age of 75 years. 28 That is, the incidence of ARHL is rapidly increasing, due to the growing number of elderly people worldwide. ARHL usually begins after 60 years of age and presents as bilateral and symmetric SNHL. Moreover, the hearing curve usually presents as a threshold elevation at higher frequencies. 29

The potential mechanisms underlying ARHL are generally attributed to the following two factors: first, the progressive peripheral degeneration leading to the disability of the sound afferent; second, the central degeneration that results in various degrees of central nervous system executive dysfunction. Therefore, the perceptual and cognitive declines resulting from ARHL cannot be explained solely by a dysfunction of peripheral sensory organs, and they frequently translate to slow perceptual processing and difficulty in accurately identifying stimuli. Accumulating evidence from ethology, neurography, and electrophysiological studies postulates that aging is associated with deficits in cognitive control abilities. 30 Etienne et al. examined the effect of intensive auditory training on the primary auditory cortex in older rats. They found a nearly complete reversal of most of the age-related functional and structural cortical changes. 31 In addition, an interesting study demonstrated that a targeted cognitive training approach resulted in enhanced discrimination abilities in both older rats and humans. 32 Therefore, all of the aforementioned studies may be useful for us to think about how the progression of ARHL may be controlled or even recovered since the impairment of auditory cortex can be repaired via adaptive cognitive training approach.

Ototoxic drugs

Numerous investigations have shown that the clinical application of aminoglycoside antibiotics and platinum antitumor drugs is the major cause of ototoxic drug–induced SNHL. Moreover, other ototoxic drugs including doxorubicin (DOXO), aromatic solvent, ouabain, glutamic acid, glutamate analogues, 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (HPβCD), and heavy metals also contribute to ototoxic drug–induced SNHL. 33 Kyle et al. 34 reported that aspirin has a dose-dependent ototoxic side effect in elderly people, but the damage is reversible. Sensory hair cells undergo necroptosis and apoptosis after exposure to ototoxic drugs. 35 In addition, investigators found that salicylates damage the spiral ganglion neurons and their peripheral fibers in a dose-dependent manner. 36 Although no therapy is available for the treatment of ototoxic drug–induced SNHL, it is possible to reduce the incidence of the disease by limiting the application of some of those ototoxic drugs, such as analgesics and aminoglycosides.

Ion homeostasis

Correlative data from morphological and electrophysiological studies support the hypothesis that the disturbance of calcium homeostasis in the cochlea is an important underlying factor for SNHL. Recent studies have shown that voltage-gated calcium influx can load the synaptic cistern to modify the efficacy of cholinergic synaptic inhibition of immature IHCs. The author concluded that IHC calcium electrogenesis modulates the efficacy of efferent inhibition during the maturation of IHC synapses. 37 Moreover, K+ channels and transporters are essential for preserving the sensory structures and supporting transduction. 38 Therefore, maintaining endolymph homeostasis is critical to sustain auditory functions. Belyantseva et al. 39 reported that large sound-evoked changes in K+ flux can lead to osmotic swelling of IHCs. The K+ influx in IHCs leads to a rise in extracellular K+, which can depolarize hair cells. 40

Chronic diseases: diabetes, autoimmune disease

Dysglycemia has been recognized as a risk factor for SNHL. A growing number of evidences demonstrate that dysglycemia may contribute to SNHL. Patients diagnosed with diabetes are more susceptible to SNHL. SNHL may be considered a comorbidity related to diabetes. The possible mechanisms among diabetes and SNHL may be attributed to microvascular disease, acoustic neuropathy, or oxidative stress based on some cohort studies in humans.41,42 The degree of hearing loss may depend on the duration and severity of diabetes. Further studies should focus on preventing diabetes or improving long-term glycemic control in patients with diabetes.

Studies have focused on the interaction between autoimmune disease and SNHL. 43 Immune-mediated SNHL may present in a sudden, chronic, rapidly progressive, or fluctuating form. Moreover, the onset is bilateral and the hearing curve is asymmetric. The mechanism of immune-mediated SNHL is still unclear and may be related to inflammatory macrophages and microglia in cochlea. These cells in the cochlea play an important role in the onset of SNHL due to increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines, ROS, and antigens. The possible mechanisms are as follows:44,45 (1) these proinflammatory cytokines lead to vasculitis of inner ear vessels and reduce the caliber of auditory arteries with a consequent decrease in blood flow; (2) ROS is also responsible for the impairment of hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons; (3) circulating antibodies against inner ear antigens lead to antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity, the activation of the complement system, a direct action of cytotoxic T cells, or immune complex–mediated damage. Cumulative studies have reported that a number of autoimmune diseases are associated with immune-mediated SNHL, such as systemic lupus erythematosus,46,47 Cogan syndrome, 48 sarcoidosis, 49 and rheumatoid arthritis. 50 Corticosteroids are the major therapy for immune-mediated SNHL and may lead to a near-complete hearing restoration. Therefore, it is critical to diagnose the autoimmune disease as early as possible.

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss

Sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL) is defined as SSNHL of at least 30 dB in three sequential frequencies in the standard pure-tone audiogram over 3 days or less. Multiple surveys estimated the incidence of SSNHL at between 5 and 30 cases per 100,000 per year. 51 Population studies have shown that SSNHL is usually unilateral. The incidence of bilateral SSNHL is reported to be less than 5%. 52 SSNHL often presents with sudden drops in hearing, vertigo, tinnitus, and a feeling of ear fullness. The exact causes of the disease are not yet clear, but it is usually attributed to various infective, vascular, and immune facets and so on. Early intervention is generally considered necessary and may be the best chance for the improvement of SSNHL. Delay in dealing with the disease owing to the neglect from the patients and missed hearing assessments may cause serious implications, including permanent SSNHL. 53 Therefore, prompt diagnosis and management are critical for the recovery of SSNHL.

Preventions of SNHL

Difficulties and necessity

SNHL is a universal problem. However, it is also be considered as the ‘invisible disability’ and receives limited public awareness in some places. People usually pay less attention to SNHL compared with other health problems, such as blindness and dementia. Earlier data indicate that the societal and economic burdens will increase if enough resources were not allocated for prevention and therapy of SNHL. The major barriers to widespread use of hearing healthcare included the high costs of hearing healthcare, lack of insurance coverage, the stigma associated with impairment and wearing hearing aids, and limited awareness of hearing health and the range of available options. 54 Therefore, it is necessary to raise awareness of the potential impact of SNHL and to focus on preventing SNHL. Global multidisciplinary and collaborative efforts should be allocated to patients suffering from SNHL. SNHL cannot, and must not, continue to be a silent epidemic.

Current situation

Fortunately, SNHL has received much more attention in recent years.54,55 Focusing on SNHL prevention will vastly improve the quality of life (QOL) of patients and their families and transform the future for society. However, not everyone will be able to make some changes and these changes may not make a difference; in some cases, the causes of SNHL are genetic and difficult to change. Nonetheless, delays in SNHL for a few years for even a small group of people would be an enormous achievement and would enable many more people to receive a high QOL. Electrophysiological, pharmacological, psychological, environmental, and social interventions should be conducted by the WHO, governments, leaders, social institutions, and professors. The World Health Assembly renewed the 1995 resolution on the prevention of hearing impairment, urging member states and the director general of WHO to take specific steps to curtail the disease burden. All of the measures should focus on raising awareness of the importance of SNHL among healthcare measures and ameliorating the present practices and providing new measures for hearing healthcare according the changing conditions for hearing healthcare worldwide. 56

Prevention measures

The incidence and impact of SNHL are staggering, and half SNHL could be prevented with low-cost interventions that include immunization for rubella, mumps, measles, and meningitis. For losses that cannot be prevented, hearing aids or cochlear implants can produce favorable outcomes in most cases, and unprecedented opportunities exist for reducing the costs of these and other treatments. 57

Prenatal genetic diagnosis and newborn hearing screening are universal and make the hearing interventions for babies with serious problems happen as early as possible. Therefore, early access to language for children with SNHL via hearing aids, cochlear implants, or sign language, as well as appropriate support, is needed to ensure normal cognitive, educational, and psychosocial development. Approximately half of all SNHL is preventable through public health strategies such as immunization against childhood diseases. In addition, more than 1 billion young people are globally at risk of developing SNHL through exposure to loud music through personal audio devices. 30 The WHO issued a global standard for manufacturers of personal audio devices to improve their safety. 58 In 2017, Fink DJ proposed that the safe noise exposure level to prevent SNHL is 70 dB time-weighted average for 24 h [Leq(24) = 70]. 59 These standards will result in quiet environments, effectively prevent SNHL, and alleviate developmental and social consequences of SNHL. Meanwhile, professors should speak up about the health dangers of noise.

Doctors should try their best to avoid prescribing ototoxic drugs for patients, especially children, with normal infections since ototoxic drugs could be replaced with other non-ototoxic antibiotics. However, we should use some drugs to protect the inner ear and the subsequent SNHL if ototoxic drugs cannot be avoided. Meanwhile, prompt diagnosis of autoimmune diseases related to SNHL is critical to control the progression of SNHL or even prevent the incidence of autoimmune forms of ear disease. A proper diet which includes reducing the ADI (acceptable daily intake) of carbohydrate and physical exercise can alleviate inner ear impairment in patients with diabetes. Owing to the aforementioned causes of SNHL, we hypothesize that balanced nutrition or even balanced iron homeostasis is helpful for SNHL, and studies should be carried out in the future.

SNHL is the third most prevalent chronic disease in elderly people and leads to negative effects on physical and mental health, which eventually overwhelm families and aggravate socio-economic burdens. Despite the prevalence and negative effects of ARHL, SNHL is not estimated and treated in most older adults. Given the aforementioned factors, it is necessary for primary care physicians to screen and manage adult SNHL. For example, prompt recognition of potentially reversible causes of SNHL, such as SSNHL, ototoxic drug–induced SNHL, and infections of middle/inner ear, may greatly maximize the possibility of hearing function recovery.

Current therapy for SNHL

The development of effective therapeutic strategies to prevent or treat SNHL has proven to be a relatively difficult progress, as demonstrated by the lack of restorative medicines and technologies. 60 Consequently, there is an overwhelming impression between professionals and the public that hearing aids are all that can be done for SNHL. However, SNHL requires concerted counseling, rehabilitative training, environmental accommodations, and training. Therefore, we would like to explore the advantages and limitations associated with currently available strategies for the restoration of SNHL.

Clinical interventions

Hearing device to replace hearing loss

Currently, there are very few treatment options for people with SNHL. With the rapid development of technology, hearing devices appear as a promising approach for the treatment of SNHL. People can partially or even greatly benefit from hearing devices, including hearing aids, middle ear implants, and cochlear implants. Hearing aids were widely used to amplify the signal of sound for patients suffering from a mild or moderate SNHL, whereas middle ear and cochlear implants are suitable for patients whose SNHL cannot be compensated by hearing aids.

The use of hearing aids is the cornerstone of audiologic intervention. Hearing aids are considered sound-amplifying device that is used to compensate for impaired hearing. There is mounting evidence that shows that the QOL status of people with SNHL will be greatly improved after treatment with well-fitted hearing aids which can strengthen the audibility of speech and other sounds and minimize participation restrictions.60,61 Despite the benefits of hearing aid, the use of it is lower than the real incidence of SNHL owing to missed diagnoses, patient refusal, and high costs of the devices and their subsequent service. H Staecker reported that only 14.2% of adults suffering from hearing impairment wear hearing aids. 62 Furthermore, approximately 30% of patients who receive hearing aids refuse to wear them for various reasons, such as stigma, perceived effectiveness, ongoing costs, lack of comfort, and cosmetic appearance. 63 Although there is an obvious benefit of hearing aids, Bojana listed several shortcomings in the current hearing-aid fitting procedures. First, they require the hearing aid users to actively perform a task, which may not be optimal for all types of patients. Second, the pure-tone audiogram does not index supra-threshold processing abilities, as required for arguably the most important hearing-aid outcome: speech understanding. Third, the fitting procedures cannot be re-evaluated in real-time, nor can they adjust to a user’s distinct demands in complex listening conditions. 64 As a result, various investigations should be conducted to solve these questions.

Cochlear implants are now universally used and considered to be the standard of care for patients with severe-to-profound SNHL that cannot be compensated by hearing aids. Many people with SNHL typically benefit from cochlear implants that bypass the cochlea hair cells and provide direct electrical stimulation to the auditory neurons. 65 Cochlear implants often work very well and display substantial benefits in speech perception. Nonetheless, the wide use of cochlear implants is restricted due to their high cost. 66 The cost of the cochlear implant could be reduced by encouraging specialists to prompt the innovations in technology and to supervise competitions between governments. 57 Unfortunately, while many patients have received many benefits from cochlear implants, a number of patients have achieved poor outcomes. Future research on cochlear implants should focus on finding predisposing factors that are responsible for variability in outcomes following implantation. What’s more, studies should find out proper methods to predict patients who will not receive an ideal outcome with cochlear implant and provide effective measures to ameliorate the poor outcome. 67

Auditory brainstem implant (ABI) is a surgically implanted central neural auditory neuroprosthesis that provides a safe and effective auditory rehabilitation for patients with profound SNHL who are not candidates of cochlear implant due to abnormalities of the cochlea and the cochlear nerve. 68 In 2000, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of ABIs in patients diagnosed with neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Recently, it has been reported that the use of ABI was not restricted to only patients with NF2 but was also expanded to non-NF2 patients.69,70 ABIs have similar components as cochlea implant.71–73 The electrical impulse–derived sounds can directly stimulate the nucleus through a soft silicone paddle that is placed along the surface of the brainstem. Although the speech outcomes of patients with ABIs are inferior to those of patients with cochlear implantation 74 and non-tumor patients with ABIs may benefit more from ABIs than NF2 patients, it is effective in the recovery of auditory input and offers hope for a group (population) of patients who would otherwise fail to benefit from the auditory world forever.

Drug treatment

Current promising drugs for SNHL primarily include steroids 75 and neurotrophic factors. Steroids are considered the main treatment for hearing impairment, including SSNHL and autoimmune disease–related SNHL. Moreover, neurotrophic factors were thought to be one of the more effective drug-based therapies for NIHL to repair the ribbon synapse, to prevent the loss of primary auditory neurons, and to facilitate the regrowth of auditory neuron fibers after severe SNHL. 76 In addition, drugs that modify the microcirculation, diuretics, and salicylate are widely used in the treatment of some types of SNHL. Although the wide application of the aforementioned drugs leads to partial hearing function recovery in some patients, there is a lack of randomized, double-blind, case-controlled studies to confirm those reagents as standard therapy.

Pre-clinical intervention

Currently, hearing devices are one of the most important ways to improve hearing performance for many patients. Nevertheless, the effect is limited because although the residual hair cells can be stimulated, they cannot restore the underlying pathology: cell loss in the cochlea and the degeneration of both peripheral and central auditory systems. A cumulative investigation has been carried out over the past decades to explore the novel drugs, progenitor cells, genes, and operant training for the development of SNHL therapy based on the genetic mechanisms and molecular pathways underlying hearing impairment. 77

Hair cell regeneration

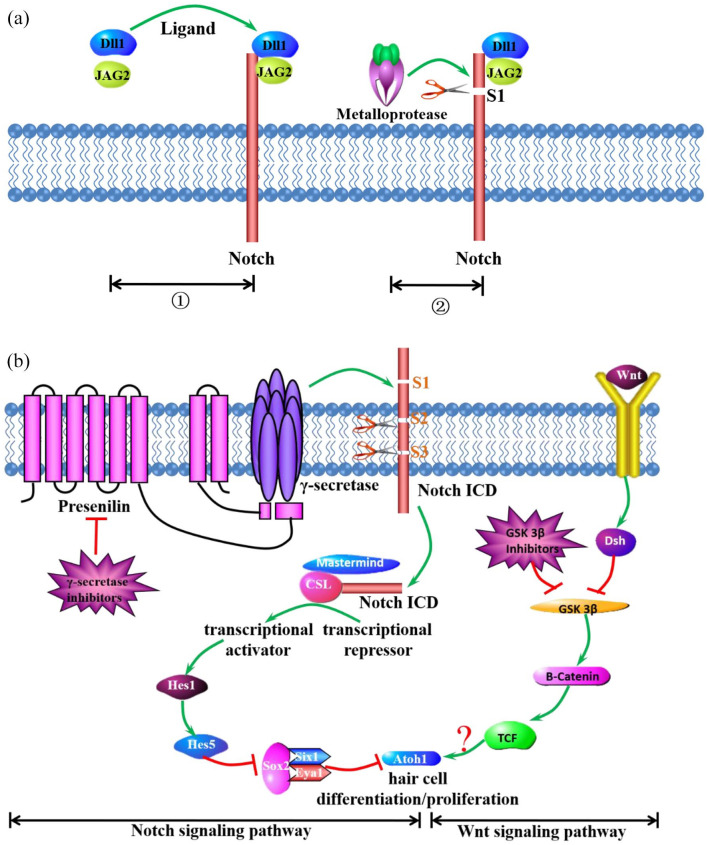

The sensory hair cells in the cochlea serve as mechanoreceptor cells for detecting sound and transmitting their electrical signal to the brain via the auditory nerve. Since mammalian hair cells cannot be replaced, loss of hair cell and subsequent auditory loss lead to a high prevalence of SNHL. Although hair cells cannot regenerate, hair cells and spiral ganglion neurons can be transdifferentiated from various kinds of progenitor cells in the cochlea 78 and transplanted stem cells cultured in vitro 79 or even under the role of gene 80 or RNA delivery. 81 Extensive data are available on gene expression that may lead to hair cell regeneration. 82 Hair cells are specified after the activity of the transcription factors. Many studies have reported that hair cells can be regenerated by local delivery of Atoh1 both in vitro and in vivo. Moreover, while the Wnt signaling pathway plays a major role in promoting hair cell proliferation or differentiation in the organ of Corti, the Notch signaling pathway plays a negative role in hair cell fate. Dll1 and JAG2 are both activators of the notch signal by binding to the DSL region of the two ligands. Then, the notch signal is cleaved into three pieces by γ-secretase, and one piece of the notch signal called the Notch-intraceullar domain (ICD) is released into the intramembrane. Presenilin is the catalytic center of the metalloprotease. The Notch ICD translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with CSL (C-promoter-binding factor). The binding of the Notch ICD and the recruitment of the co-activator protein Mastermind convert CSL from a transcriptional repressor to an activator, which results in the inhibition of hair cell fate.83,84 Wnts binds to the cell surface receptors encoded by the Frizzled gene family, which in turn activates Dsh. The precise role of Dsh activation may turn off the expression of GSK3β and lead to the accumulation of β-catenin, which binds to T-cell factor (TCF) and recruits other proteins to drive Atoh1-mediated hair cell fate. Notch/Atoh1 is counteracting with each other to regulate the Hair Cells/Supporting Cells. 5 Thus, hair cell proliferation or differentiation will be greatly improved if the Notch signaling pathway is inhibited and the Wnt signaling pathway is activated. Nevertheless, both important signaling pathways interacted through the transcription factor, Atoh1 (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The role of Notch and Wnt signaling pathways on Atoh1-mediated hair cell differentiation and proliferation. (a), Dll1 and JAG2 are both activators of the notch signal by binding to the DSL region of the two ligands. Then, the notch signal is cleaved into three pieces by γ-secretase, and one piece of notch signal called Notch intracellular domain (ICD) is released into the intramembrane. Presenilin is the catalytic center of metalloprotease. (b), The Notch ICD translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with CSL (C-promoter-binding factor). The binding of the Notch ICD and the recruitment of the co-activator protein Mastermind convert CSL from a transcriptional repressor to an activator, which results in the inhibition of hair cell death. Wnts binds to the cell surface receptors encoded by the Frizzled gene family, which in turn activates Dsh. The precise role of Dsh activation may turn off the expression of GSK3β and lead to the accumulation of β-catenin, which binds to T-cell factor and recruits other proteins to drive Atoh1-mediated hair cell death. Thus, it is necessary to promote the Wnt signaling pathway and inhibit the Notch signaling pathway to promote Atoh1-mediated hair cell differentiation or proliferation.

Although a growing number of studies have proved the existence of progenitor cells within the cochlea, which have defined capacities to differentiate into hair cells and neurons after cochlea development is complete, those cells fail to divide and form hair cells and neurons to alleviate hearing impairment. Furthermore, difficulty in generating large numbers of progenitor cells has limited genetic and physiological studies on the advancement of potential therapies. Thus, it is necessary to induce reagents to obtain more progenitor cells and stimulate those cells to differentiate into hair cells and neurons. Will McLean and his team found that 2000-fold Lgr5-positive cells could be produced after the stimulation of Wnt signaling by a GSK3b inhibitor and transcriptional activation by a histone deacetylase inhibitor. As a result, these Lgr5-expressing cells differentiate into hair cells at a high yield. 85 Since early studies demonstrated regenerated hair cells in damaged tissues, recent experiments have illustrated that progenitor cell differentiation promotes hearing improvement in animals with SNHL. 86 In addition, while increasing data have shown that progenitor hair cell is available during animal development, only limited information has expanded development for the treatment in humans. In 2013, Heiko Locher et al. 87 were the first to provide notable insights into the onset of hair cell differentiation and innervation within a pre-sensory domain in the human fetal cochlea. Moreover, a recent study not only purified postmitotic hair cell progenitors derived from human fetal cochlea, but also promoted these cells to regain progenitor potential to eventually differentiate to hair cell–like cells in vitro. 88 Thus, these breakthroughs offer a blueprint of inner ear development and guide efforts to obtain more abundant progenitor cell sources to generate hair cells or even provide patients with an effective therapy in the future.

Gene therapy

Genetic factors contribute to approximately half of all cases of SNHL. Although 6000 causative variants in more than 150 genes have been identified, few effective treatment options are available to inhibit the progression of genetic SNHL. 89 Atoh1 expression is critical for cochlear hair cells. Meanwhile, Eya1 and Sox2 are expressed in the cochlear nuclei that require the upregulation of Atoh1 for cochlear nuclei development. 82 Gene intervention, which has recently shown promising outcomes, usually consists of the following methods. First, the basic form of gene therapy is gene replacement, which means that functional cDNA with the correct coding sequence is delivered to specific cell types to complement the non-functional wild-type alleles. 90 Second, gene silencing is another form of gene therapy. Silencing dominant-negative mutant alleles can be achieved at the transcriptional level by RNA interference to prevent mRNA translation. 91 Finally, gene editing has appeared as a new gene therapy approach to prevent hair cell loss and improve hearing function. The CRISPR/Cas9 system can mediate targeted gene disruption or repair, which is linked to genetic SNHL and affects the function of hair cells. 92 Gao et al. 93 developed CRISPR/Cas9-based genome-editing complexes targeting Tmc1Bth to knockdown the dominant mutant allele in the cochlea of neonatal Tmc1Bth/+ mice. The approach improved the hair cell survival rates followed by hearing rehabilitation in the injected ears. This finding effectively relieved a bottleneck in the field and provided a benchmark for future gene therapy. Nonetheless, current gene therapy approaches face potential challenges including stability and target selection, timeliness, immunogenicity, oncogenicity, toxicity to the inner ear, and limitations of viral vectors, so more solid preclinical studies must be conducted prior to further patient application. 90

Caloric restriction and antioxidant enhancement

Oxidative stress is considered one of the most common mechanisms of SNHL, especially in NIHL and ARHL. Although the cellular mechanisms underlying cochlear degeneration have yet to be fully understood, the available evidence implicates that the formation and accumulation of ROS may play an important role in cochlear cell loss over time. Thus, an abundance of experiments focusing on oxidative stress has drawn attention to antioxidant defense and the protective function of antioxidants in SNHL. Numerous studies have indicated that caloric restriction can significantly reduce oxidative damage, enhance antioxidant defense, facilitate the upregulation of the sirtuin pathway, and promote the stress response–induced upregulation of heat shock proteins. We have mentioned the importance of antioxidant defense by caloric restriction and antioxidant enhancement by the application of antioxidants in ARHL. Simultaneously, many studies have reported that both the caloric restriction and antioxidant applications, including Nox3 13 and P62, 94 are also promising approaches for the treatment of NIHL.

Conclusion

According to WHO, by 2050 there will be more than 900 million people (1 in every 10 people) who will suffer from disabling SNHL, which implies an enormous burden for the development of society and economics. Since there are a few sufficient therapeutic options, approximately half of all SNHL is preventable through public health measures such as inclusive action, early intervention, and the positive support from families and society. Nonetheless, the amelioration of auditory function in the remaining half of people with SNHL mainly depends on the development of hearing devices and preclinical approaches, which will be translated to clinic measures as soon as possible. Thus, it is hoped that scientists and clinicians can cooperate and co-ordinate together based on the essential mechanisms that bring basic research to the clinic, which will resolve the damaging effects of SNHL in patients.

Footnotes

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The review was approved by the first affiliated hospital of Sun Yat-sen University. Consent to participate is not required for this review.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Hongmiao Ren: Investigation; Writing – original draft

Bing Hu: Conceptualization; Visualization

Guangli Jiang: Methodology

Availability of data and materials: Data and materials are available from the corresponding auther on reasonable request.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81700908) and Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2016A030310148, 2022A1515011051).

Conflict of interest statement: All of the authors declare that there are no conflicts of interests during the process of research and publication. The subjects’ written consent was approved by the First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University.

ORCID iD: Hongmiao Ren  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6221-6101

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6221-6101

Contributor Information

Hongmiao Ren, Otorhinolaryngology Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510080, Guangdong, P.R. China.

Bing Hu, Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Shenzhen University Health Science Center, Shenzhen, China.

Guangli Jiang, Otorhinolaryngology Hospital, The First Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China.

References

- 1. Cunningham LL, Tucci DL. Hearing loss in adults. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 2465–2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ohmen J, Kang EY, Li X, et al. Genome-wide association study for age-related hearing loss (AHL) in the mouse: a meta-analysis. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2014; 15: 335–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ren HM, Ren J, Liu W. Recognition and control of the progression of age-related hearing loss. Rejuvenation Res 2013; 16: 475–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peixoto Pinheiro B, Vona B, Lowenheim H, et al. Age-related hearing loss pertaining to potassium ion channels in the cochlea and auditory pathway. Pflugers Arch 2021; 473: 823–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Xu J, Li J, Zhang T, et al. Chromatin remodelers and lineage-specific factors interact to target enhancers to establish proneurosensory fate within otic ectoderm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2021; 118: e2025196118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Christensen K, Frederiksen H, Hoffman HJ. Genetic and environmental influences on self-reported reduced hearing in the old and oldest old. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001; 49: 1512–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu S, Li S, Zhu H, et al. A mutation in the cdh23 gene causes age-related hearing loss in Cdh23(nmf308/nmf308) mice. Gene 2012; 499: 309–317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang M, Tan H, Yang Q, et al. Association of hsp70 polymorphisms with risk of noise-induced hearing loss in Chinese automobile workers. Cell Stress Chaperones 2006; 11: 233–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zheng QY, Ding D, Yu H, et al. A locus on distal chromosome 10 (ahl4) affecting age-related hearing loss in A/J mice. Neurobiol Aging 2009; 30: 1693–1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Charizopoulou N, Lelli A, Schraders M, et al. Gipc3 mutations associated with audiogenic seizures and sensorineural hearing loss in mouse and human. Nat Commun 2011; 2: 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gao Z, Yuan YS. Screening for mitochondrial 12S rRNA C1494T mutation in 655 patients with non-syndromic hearing loss: an observational study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2020; 99: e19373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tsutsui H, Kinugawa S, Matsushima S. Mitochondrial oxidative stress and dysfunction in myocardial remodelling. Cardiovasc Res 2009; 81: 449–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mohri H, Ninoyu Y, Sakaguchi H, et al. Nox3-derived superoxide in cochleae induces sensorineural hearing loss. J Neurosci 2021; 41: 4716–4731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kral A, O’Donoghue GM. Profound deafness in childhood. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 1438–1450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Yehya A, Al-Trad B, Bani-Hmoud M, et al. Pharmacogenetic screening of A1555G and C1494T mitochondrial mutations and the use of ototoxic drugs among Jordanians. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021; 25: 5684–5689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tang K, Gao Z, Han C, et al. Screening of mitochondrial tRNA mutations in 300 infants with hearing loss. Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp Seq Anal 2019; 30: 345–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fetoni AR, Paciello F, Rolesi R, et al. Targeting dysregulation of redox homeostasis in noise-induced hearing loss: oxidative stress and ROS signaling. Free Radic Biol Med 2019; 135: 46–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang M, Gao X, Qiu W, et al. The role of the kurtosis metric in evaluating the risk of occupational hearing loss associated with complex noise- Zhejiang Province, China, 2010-2019. China CDC Weekly 2021; 3: 378–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wong AC, Ryan AF. Mechanisms of sensorineural cell damage, death and survival in the cochlea. Front Aging Neurosci 2015; 7: 58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schmiedt RA. Acoustic injury and the physiology of hearing. J Acoust Soc Am 1984; 76: 1293–1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liberman MC, Kiang NY. Single-neuron labeling and chronic cochlear pathology. IV Stereocilia damage and alterations in rate- and phase-level functions. Hear Res 1984; 16: 75–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cunningham LL, Tucci DL. Restoring synaptic connections in the inner ear after noise damage. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 181–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hu N, Rutherford MA, Green SH. Protection of cochlear synapses from noise-induced excitotoxic trauma by blockade of Ca2+-permeable AMPA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2020; 117: 3828–3838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Resnik J, Polley DB. Cochlear neural degeneration disrupts hearing in background noise by increasing auditory cortex internal noise. Neuron 2021; 109: 984–996.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Liang W, Zhao C, Chen Z, et al. Sirtuin-3 protects cochlear hair cells against noise-induced damage via the superoxide dismutase 2/reactive oxygen species signaling pathway. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021; 9: 766512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kil J, Lobarinas E, Spankovich C, et al. Safety and efficacy of ebselen for the prevention of noise-induced hearing loss: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2017; 390: 969–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wan G, Gomez- Casati ME, Gigliello AR, et al. Neurotrophin-3 regulates ribbon synapse density in the cochlea and induces synapse regeneration after acoustic trauma. Elife 2014; 3: e03564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sprinzl GM, Riechelmann H. Current trends in treating hearing loss in elderly people: a review of the technology and treatment options – a mini-review. Gerontology 2010; 56: 351–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yamoah EN, Li M, Shah A, et al. Using Sox2 to alleviate the hallmarks of age-related hearing loss. Ageing Res Rev 2020; 59: 101042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Herrmann B, Maess B, Johnsrude IS. Aging affects adaptation to sound-level statistics in human auditory cortex. J Neurosci 2018; 38: 1989–1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Villers-Sidani E, Alzghoul L, Zhou X, et al. Recovery of functional and structural age-related changes in the rat primary auditory cortex with operant training. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 13900–13905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mishra J, de Villers-Sidani E, Merzenich M, et al. Adaptive training diminishes distractibility in aging across species. Neuron 2014; 84: 1091–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lin X, Luo J, Tan J, et al. Experimental animal models of drug-induced sensorineural hearing loss: a narrative review. Ann Transl Med 2021; 9: 1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kyle ME, Wang JC, Shin JJ. Ubiquitous aspirin: a systematic review of its impact on sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 152: 23–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ruhl D, Du TT, Wagner EL, et al. Necroptosis and apoptosis contribute to cisplatin and aminoglycoside ototoxicity. J Neurosci 2019; 39: 2951–2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wei L, Ding D, Salvi R. Salicylate-induced degeneration of cochlea spiral ganglion neurons-apoptosis signaling. Neuroscience 2010; 168: 288–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zachary S, Nowak N, Vyas P, et al. Voltage-gated calcium influx modifies cholinergic inhibition of inner hair cells in the immature rat cochlea. J Neurosci 2018; 38: 5677–5687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patuzzi R. Ion flow in cochlear hair cells and the regulation of hearing sensitivity. Hear Res 2011; 280: 3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Belyantseva IA, Frolenkov GI, Wade JB, et al. Water permeability of cochlear outer hair cells: characterization and relationship to electromotility. J Neurosci 2000; 20: 8996–9003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Martin P. Active hair-bundle motility of the hair cells of vestibular and auditory organs. In: Manley GA, Fay RR, Popper AN. (eds) Handbook of auditory research, vol. 30. Cham: Springer, 2008, pp. 93–143. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hlayisi V-G, Petersen L, Ramma L. High prevalence of disabling hearing loss in young to middle-aged adults with diabetes. Int J Diab Dev Count 2019; 39: 148–153. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Gupta S, Eavey RD, Wang M, et al. Type 2 diabetes and the risk of incident hearing loss. Diabetologia 2019; 62: 281–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mancini P, Atturo F, Di Mario A, et al. Hearing loss in autoimmune disorders: prevalence and therapeutic options. Autoimmun Rev 2018; 17: 644–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Di Stadio A, Ralli M. Systemic lupus erythematosus and hearing disorders: literature review and meta-analysis of clinical and temporal bone findings. J Int Med Res 2017; 45: 1470–1480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bodienkova GM, Boklazhenko EV. Immunochemical markers of sensorineural hearing loss. Neurochem J 2021; 15: 91–94. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chawki S, Aouizerate J, Trad S, et al. Bilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss as a presenting feature of systemic lupus erythematosus: case report and brief review of other published cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016; 95: e4345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lasso de la Vega M, Villarreal IM, Lopez Moya J, et al. Extended high frequency audiometry can diagnose sub-clinic involvement in a seemingly normal hearing systemic lupus erythematosus population. Acta Otolaryngol 2017; 137: 161–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Maiolino L, Cocuzza S, Conti A, et al. Autoimmune ear disease: clinical and diagnostic relevance in Cogan’s sydrome. Audiol Res 2017; 7: 162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Jardine DA, Recupero WD, Conley GS. An unusual cause of sudden hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015; 141: 91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ahmadzadeh A, Daraei M, Jalessi M, et al. Hearing status in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Laryngol Otol 2017; 131: 895–899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Schreiber BE, Agrup C, Haskard DO, et al. Sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Lancet 2010; 375: 1203–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Oh J-H, Park K, Lee SJ, et al. Bilateral versus unilateral sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2007; 136: 87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fishman JM, Cullen L. Investigating sudden hearing loss in adults. BMJ 2018; 363: k4347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hearing loss: an important global health concern. Lancet 2016; 387: 2351–2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wilkinson P, Ruane C, Tempest K. Depression in older adults A neglected chronic disease as important as dementia. BMJ 2018; 363: 4922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tordrup D, Smith R, Kamenov K, et al. Global return on investment and cost-effectiveness of WHO’s HEAR interventions for hearing loss: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health 2022; 10: e52–e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wilson BS, Tucci DL, Merson MH, et al. Global hearing health care: new findings and perspectives. Lancet 2017; 390: 2503–2515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Prioritising prevention of hearing loss. Lancet 2019; 393: 848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fink DJ. What is a safe noise level for the public? Am J Public Health 2017; 107: 44–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. GBDHL Collaborators. Hearing loss prevalence and years lived with disability, 1990-2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 2021; 397: 996–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Didczuneit-Sandhop B, Jozwiak K, Jolie M, et al. Hearing loss among elderly people and access to hearing aids: a cross-sectional study from a rural area in Germany. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2021; 278: 5093–5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Chien W, Lin FR. Prevalence of hearing aid use among older adults in the United States. Arch Inter Med 2012; 172: 292–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Carroll YI, Eichwald J, Scinicariello F, et al. Vital signs: noise–induced hearing loss among adults – United States 2011-2012. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66: 139–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mirkovic B, Debener S, Schmidt J, et al. Effects of directional sound processing and listener’s motivation on EEG responses to continuous noisy speech: do normal-hearing and aided hearing-impaired listeners differ. Hear Res 2019; 377: 260–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Carlson ML. Cochlear implantation in adults. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1531–1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Saunders JE, Francis HW, Skarzynski PH. Measuring success: cost-effectiveness and expanding access to cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol 2016; 37: e135–e140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Pisoni DB, Kronenberger WG, Harris MS, et al. Three challenges for future research on cochlear implants. World J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2017; 3: 240–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Faes J, De Maeyer S, Gillis S. Speech intelligibility of children with an auditory brainstem implant: a triple-case study. Clin Linguist Phon. Epub ahead of print 5 April 2022. DOI: 10.1080/02699206.2021.1988148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sennaroglu L, Sennaroglu G, Yucel E, et al. Long-term results of ABI in children with severe inner ear malformations. Otol Neurotol 2016; 37: 865–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Tam YC, Lee JWY, Gair J, et al. Performing MRI scans on cochlear implant and auditory brainstem implant recipients: review of 14.5 years experience. Otol Neurotol 2020; 41: e556–e562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Colletti V, Carner M, Miorelli V, et al. Auditory brainstern implant (ABI): new frontiers in adults and children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2005; 133: 126–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Grayeli AB, Bouccara D, Kalamarides M, et al. Auditory brainstem implant in bilateral and completely ossified cochleae. Otol Neurotol 2003; 24: 79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Colletti V, Carner M, Miorelli V, et al. Cochlear implantation at under 12 months: report on 10 patients. Laryngoscope 2005; 115: 445–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Otto SR, Brackmann DE, Hitselberger WE, et al. Multichannel auditory brainstem implant: update on performance in 61 patients. J Neurosurg 2002; 96: 1063–1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Devare J, Gubbels S, Raphael Y. Outlook and future of inner ear therapy. Hear Res 2018; 368: 127–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Muller U, Barr-Gillespie PG. New treatment options for hearing loss. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2015; 14: 346–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Geleoc GSG, Holt JR. Sound strategies for hearing restoration. Science 2014; 344: 596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Oshima K, Grimm CM, Corrales CE, et al. Differential distribution of stem cells in the auditory and vestibular organs of the inner ear. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2007; 8: 18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Abd El, Raouf HHH, Galhom RA, Ali MHM, et al. Harderian gland-derived stem cells as a cytotherapy in a guinea pig model of carboplatin-induced hearing loss. J Chem Neuroanat 2019; 98: 139–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Kim M-A, Ryu N, Kim H-M, et al. Targeted gene delivery into the mammalian inner ear using synthetic serotypes of adeno-associated virus vectors. Molecular therapy. Meth Clin Dev 2019; 13: 197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Ju C, Liu R, Zhang YW, et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-associated lncRNA in osteogenic differentiation. Biomed Pharmacother 2019; 115: 108912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Elliott KL, Pavlinkova G, Chizhikov VV, et al. Development in the Mammalian Auditory System Depends on Transcription Factors. Int J Mol Sci 2021; 22: 4189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kopan R, Ilagan MX. gamma-secretase: proteasome of the membrane. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2004; 5: 499–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Tan P-X, Du SS, Ren C, et al. Radiation-induced cochlea hair cell death: mechanisms and protection. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2013; 14: 5631–5635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. McLean WJ, Yin X, Lu L, et al. Clonal expansion of Lgr5-positive cells from mammalian cochlea and high-purity generation of sensory hair cells. Cell Rep 2017; 18: 1917–1929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. McLean W. Toward a true cure for hearing impairment. Science 2018; 359: 1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Locher H, Frijns JHM, van Iperen L, et al. Neurosensory development and cell fate determination in the human cochlea. Neural Dev 2013; 8: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Roccio M, Perny M, Ealy M, et al. Molecular characterization and prospective isolation of human fetal cochlear hair cell progenitors. Nat Commun 2018; 9: 4027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Carpena NT, Lee MY. Genetic hearing loss and gene therapy. Genomics Inform 2018; 16: e20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Ahmed H, Shubina-Oleinik O, Holt JR. Emerging gene therapies for genetic hearing loss. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2017; 18: 649–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Elbashir SM, Harborth J, Lendeckel W, et al. Duplexes of 21-nucleotide RNAs mediate RNA interference in cultured mammalian cells. Nature 2001; 411: 494–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Hou K, Jiang H, Karim MR, et al. A critical E-box in Barhl1 3’ enhancer is essential for auditory hair cell differentiation. Cells 2019; 8: 458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Gao X, Tao Y, Lamas V, et al. Treatment of autosomal dominant hearing loss by in vivo delivery of genome editing agents. Nature 2018; 553: 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Li P, Bing D, Wang X, et al. New target of oxidative stress regulation in cochleae: alternative splicing of the p62/Sqstm1 gene. J Mol Neurosci 2022; 72: 830–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]