Abstract

Background

A quantitative assessment of the dementia-friendliness of a community can support planning and evaluation of dementia-friendly community (DFC) initiatives, internal review, and national/international comparisons, encouraging a more systematic and strategic approach to the advancement of DFCs. However, assessment of the dementia-friendliness of a community is not always conducted and continuous improvement and evaluation of the impact of dementia-friendly initiatives are not always undertaken. A dearth of applicable evaluation tools is one reason why there is a lack of quantitative assessments of the dementia-friendliness of communities working on DFC initiatives.

Purpose

A scoping review was conducted to identify and examine assessment tools that can be used to conduct quantitative assessments of the dementia-friendliness of a community.

Design and methods

Peer-reviewed studies related to DFCs were identified through a search of seven electronic databases (MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Embase, EMCare, HealthSTAR, and AgeLine). Grey literature on DFCs was identified through a search of the World Wide Web and personal communication with community leads in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Characteristics of identified assessment tools were tabulated, and a narrative summary of findings was developed along with a discussion of strengths and weaknesses of identified tools.

Results

Forty tools that assess DFC features (built environment, dementia awareness and attitudes, and community needs) were identified. None of the identified tools were deemed comprehensive enough for the assessment of community needs of people with dementia.

Keywords: dementia-friendly, baseline assessment, measurement of dementia-friendliness, survey, questionnaire, dementia-friendly community

Introduction

The recognition of dementia as an urgent global public health issue (World Health Organization, 2017) has led to a growth in dementia-friendly community (DFC) initiatives around the world (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2017). A DFC is focused on the inclusion of people with dementia and on stigma reduction so that persons with dementia feel better understood, respected, and supported and can remain engaged in their communities for as long as possible (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016b; Alzheimer Society of Saskatchewan, 2017).

For DFCs to be supportive and safe for people with dementia, built and social environments in the community need to be considered (Courtney-Pratt et al., 2018; Sturge et al., 2021). For example, when the social environment is disempowering and stigmatizing, people living with dementia may lose motivation to participate in occupations that are meaningful to them (Teitelman et al., 2010) and may avoid asking for help (Milby et al., 2017). Dementia awareness campaigns can help combat stigma and increase awareness of how to support someone living with dementia, making the social environment more supportive for people with dementia (Hebert & Scales, 2019; Sturge et al., 2021). Similarly, implementing environmental design principles (such as enhanced lighting and appropriate use of colors) can improve walkability and safety (Kerr et al., 2012), making the built environment more supportive for people with dementia. As described by people living with dementia, DFC characteristics include (Alzheimer’s Australia, 2014; City of Burnaby, 2017; Wu et al., 2019):

• community awareness about dementia;

• dementia training for health and community organizations;

• support to remain living at home;

• access to timely-diagnosis and to adequate and affordable home health care;

• dementia-specific recreational and social programs;

• age and dementia-friendly environmental features such as legible signage to help people with cognitive impairment navigate their community safely;

• inclusive public transportation such as accessible bus stops; and

• availability of respite care for caregivers.

When developing a DFC initiative, most communities follow a similar process: forming a steering group; identifying and prioritizing community needs; developing a dementia-friendly action plan(s); implementing and monitoring the progress of the plan(s); and evaluating the plan’s impact (Shannon et al., 2019). To evaluate the plan’s impact, assessment of the dementia-friendliness of the community before and after implementation of the plan(s) is needed.

In the published literature, quantitative and qualitative methods have been used to assess the dementia-friendliness of a community. Qualitative methods are typically used to understand processes and reasons why an intervention (such as a DFC initiative) resulted in the observed impact/outcome, when engaging marginalized communities or when quantitative tools may be difficult to administer (Rao & Woolcock, 2003). Qualitative methods in the reviewed literature have included focus groups and walking interviews (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016a; Alzheimer’s Society UK, 2013; Alzheimer Society of Saskatchewan, 2017) and they have been used to elicit information about the experience of living with dementia, such as the impact of stigma on community participation and access to care (Alzheimer’s Society UK, 2013). Quantitative methods are typically used to measure changes and impact over time, drawing inferences from observed statistical relations, and gathering responses on a broad range of topics (Rao & Woolcock, 2003). Quantitative methods in the reviewed literature have included surveys, which have been used to gather information on a broad range of topics such as transportation and community services (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016a).

Public documents and research articles are available to guide stakeholders in the planning of a DFC initiative (see, e.g., Heward et al., 2017; World Health Organization, 2021). However, little attention has been paid to the evaluation of DFC initiatives, resulting in a lack of guidance about how to assess dementia-friendliness. As described in a scoping review of characteristics and foci of DFCs in England by Buckner et al.(2019), commonly used impact indicators include the number of “Dementia Friends” (i.e., someone that learns about dementia by watching an educational video (Alzheimer’s Society UK, 2017a)) and “Dementia Friend Champions” (i.e., volunteers who teach others how to support people with dementia (Alzheimer’s Society UK, 2017c)); number of dementia-friendly businesses and activities; and the recognition of the community as dementia-friendly by the local Alzheimer’s Society (Buckner et al., 2019). These indicators provide useful information about community interest in working towards becoming “dementia-friendly”; however, they do not provide an indication of change in the dementia-friendliness of the community (such as evidence of barriers to participation being removed) and impact of the initiative on the well-being of people impacted by dementia. Similarly, in an integrative review of international research conducted on DFC initiatives, Shannon et al.(2019) found that a baseline assessment of the dementia-friendliness of a community is not always conducted, and continuous improvement and evaluation of the impact of dementia-friendly initiatives are not always undertaken (Shannon et al., 2019; Turner & Morken, 2016). Possible explanations for why DFC initiatives have not focused on evaluation include complexity of the initiatives (Shannon et al., 2019) and a lack of applicable evaluation tools (Hebert & Scales, 2019).

Although qualitative methods can elicit rich and detailed information about the experiences of people with dementia, such as community enablers and barriers, this information is subjective and does not provide a comprehensive or generalizable cross-section of the population of people living with dementia. In recognition of this, some communities have utilized surveys to assess the dementia-friendliness of their community, which has allowed them to obtain responses from a larger sample and the ability to measure change over time. However, in the absence of established DFC assessment tools, communities have developed their own tools (e.g., surveys) to assess how dementia-friendly their community is (see, e.g., Alzheimer’s Society UK, 2013). While self-developed DFC surveys allow assessment to be tailored to the needs of a particular community, without a rigorous method of survey construction it is difficult to evaluate the accuracy of the assessments. As a result of a lack of confidence in an assessment’s findings, tools cannot be used to evaluate progress within a single community in response to initiatives and to conduct comparisons between communities.

In the process of designing tools to assess the impact of interventions, validity, reliability, and responsiveness to change are important factors to consider (Gadotti et al., 2006). Validity refers to the extent to which the assessment tool measures what it intends to measure (Rossi et al., 2004). Reliability refers to the extent to which the measurement is consistent and reproducible (Rossi et al., 2004). Responsiveness to change refers to the ability for a tool to pick up changes over time in what is being measured (Husted et al., 2000). Without demonstrated validity, reliability and responsiveness to change, a baseline quantitative assessment has little utility as an evaluation tool, as it is not guaranteed to capture the impact of an initiative over time.

A quantitative assessment can support planning, internal review, evaluation of impact, and national/international comparisons, encouraging a more systematic and strategic approach to the advancement of DFCs (Buckner et al., 2019). The integrative and scoping reviews about DFCs conducted by Shannon et al.(2019) and Buckner et al.(2019) identified a lack of outcome and impact evaluations in existing DFC initiatives. A dearth of applicable evaluation tools has been cited as a reason for the lack of assessments of dementia-friendliness (Hebert & Scales, 2019). There is a need for quantitative assessment tools and guidance for community leaders and stakeholders on how to select or construct assessments of dementia-friendliness. To build on this work, the aims of this scoping review were to (1) identify assessment tools that have been developed to conduct quantitative assessments of the dementia-friendliness of a community; (2) review DFC domains covered in the identified tools to assess whether they are sufficiently comprehensive to evaluate the dementia-friendliness of a community; (3) investigate whether identified assessment tools have been assessed for reliability, validity, and/or responsiveness to change; and (4) describe how identified assessment tools have been used in local contexts and in research. This research will provide guidance to stakeholders working on DFC initiatives that wish to determine baseline dementia-friendliness, measure progress and/or evaluate the impact of their initiative. Findings from this review will be of use to dementia-friendly researchers, community leaders and stakeholders.

Review question(s)

1. What assessment tools have been developed to quantitatively assess the dementia-friendliness of a community?

2. Are the identified tools sufficiently comprehensive to use in assessing dementia-friendly features in a community?

3. Have the identified tools been assessed for reliability, validity, and/or responsiveness to change?

4. How have the identified tools been used in research and in practice related to DFCs?

Methods

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute methodology for scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2020). This method is based on the earlier work of Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and Levac, Colquhoun and O’Brien (2010). As recommended by Levac and colleagues (2010), to validate and enhance the results of the review and make them more useful for end-users, a consultation phase was included. The scoping review protocol was registered within the Open Science Framework (registration https://osf.io/zbvy5/) and it is being reported in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018).

Inclusion criteria

Concept

In this review, we considered studies and reports that identify tools that have been designed to assess the dementia-friendliness of a community by evaluating one or more of the following DFC domains (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016a; World Health Organization, 2007):

• transportation;

• housing;

• outdoor spaces and buildings;

• businesses;

• legal and advanced care planning services;

• financial services;

• dementia awareness;

• care throughout the continuum;

• memory loss supports and services;

• emergency planning and first response;

• respect and social inclusion;

• independent living;

• civic participation and engagement;

• dementia-accessible community activities social; and

• quality of life;

The domains were informed by the Alzheimer’s Disease International key outcomes of DFCs (awareness and understanding of dementia; increased social and cultural engagement for the person with dementia; legal and other measures in place to empower people with dementia to protect their rights; increased health and community services that respond to the needs of people with dementia; and actions to improve indoor and outdoor spaces; Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016a), and the World Health Organization (WHO) age-friendly domains (outdoor spaces and buildings; transportation; housing; social participation; respect and social inclusion; civic participation and employment; community support and health services; World Health Organization, 2007).

Context

In this review, community refers to a geographic location. Assessment tools that have been developed to investigate dementia-friendly environments in healthcare organizations, such as long-term care homes, were not included in this review.

Types of sources

In this review, we considered peer-reviewed studies, policy papers, websites, and grey literature on published organizational reports. Only quantitative assessment tools were considered. Proprietary tools under copyright were included in the review if they could be viewed without paying a fee.

Search strategy

Assessment tools were identified through three channels: (1) a search of peer-reviewed articles related to DFCs; (2) World Wide Web search of grey literature on DFC initiatives; and (3) personal communication with community leads. All searches were conducted between January 2021 and April 2021.

Peer-reviewed literature

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with a health science librarian at McMaster University, Canada. In keeping with the Joanna Briggs Institute method, a three-step search strategy was used. An initial search of MEDLINE and CINAHL was undertaken using the keywords: dementia or Alzheimer, (community or communities) OR (neighbourhoods or neighborhoods), inclusive or friendly, rating scale or evaluation tool or assessment, or evaluation. This initial search was followed by an analysis of the text words contained in the title and abstract of retrieved articles, and of the index terms used to describe the articles. A second search using all relevant identified keywords and index terms was undertaken across all seven included databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Embase, EMCare, HealthSTAR, and AgeLine. Third, the reference lists of all identified articles were searched for additional studies.

Only studies written in English were reviewed. We did not limit the date of the search as we recognized that, as a relatively new topic, most of the identified sources would be relatively recent.

World Wide Web search of grey literature

In Shannon et al.’s (2019) integrative review, research about DFCs was found to have been conducted in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. Grey literature sources from these countries were identified by a search of the World Wide Web using Google advanced search functions. In addition, the United States has a national Dementia Friendly America (Dementia Friendly America, 2015) which is a network of communities working towards becoming dementia-friendly. As this network has a wide reach, we also identified grey literature sources from the United States. Sources included toolkits, reports, and DFC websites. The terms used in the search included dementia-friendly community report, dementia-friendly community assessment, dementia-friendly assessment, dementia-friendly community toolkit, and dementia-friendly community survey.

Personal communication with community leads

Grey literature sources were also identified through personal communication with community representatives from communities that have conducted DFC initiatives in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Community representatives were identified in DFC websites, reports, and through the research team’s network. Snowball sampling to identify other community representatives was also used. Community representatives were asked whether and how they had measured the dementia-friendliness of their community. If they had conducted an assessment, they were asked which tool(s) they had used, or had considered using, for their assessment.

Selection of sources of evidence

Following the search, all identified citations were collated and uploaded into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, n.d.) and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by LGD and VM using the inclusion criteria for the review. In cases where it was not clear whether the source met the inclusion criteria, the document was retrieved and included for the full-text review. The full text of selected documents was retrieved and assessed in detail against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by LGD and VM. Sources that did not include a quantitative tool, did not focus on DFCs, or included a tool identified elsewhere were excluded. Disagreements that arose between reviewers were resolved through the involvement of LL.

To investigate how the tools found in peer-reviewed articles have been used in research related to DFCs, the database in which the article was found and Google Scholar were used to identify all manuscripts that have cited the article. The title and abstract of all “cited by” manuscripts were scanned and those related to DFCs underwent a full-text review. The names of all identified tools were also searched in Google to investigate whether these have been used in the grey literature or by other communities working on a DFC initiative.

Charting the data

To assess and compare the assessment tools, every question in each tool was categorized by LGD and VM according to the domain of dementia-friendliness it addressed (refer to eligibility criteria). For questions that had multiple sub-questions, the sub-questions were treated as separate items. During the review, four domains were added to the extraction tool (indoor spaces; participation in leisure activities; healthcare services; and communication and information) as many of the identified tools had questions associated with these areas. In addition, information about tool developers; year the tool was created; languages in which the tool is available; country in which the tool was developed; whether people with dementia were involved in tool development; whether theory guided tool development; reliability, validity,, and responsiveness to change of the tool (when available); number of demographic questions; and number of open-ended questions were extracted.

Collating, summarizing, and reporting results

After completion of the data extraction, the characteristics of all assessment tools included in this scoping review were tabulated. Details about the author(s), type of tool, year of publication, country of origin, developers, psychometric properties (if any), target population, and type of questions included were compiled. A narrative summary describing how the results relate to the review’s objectives was developed along with a discussion of strength and weaknesses of identified tools.

Consultation with stakeholders

The objectives of the consultation phase were to share findings with stakeholders and discuss the meaning and significance of the findings. Stakeholders working on developing and implementing a DFC initiative in urban and rural communities were invited to participate in the consultation. LGD presented the search strategy and preliminary findings to attendees, which was followed by a discussion of the results.

Results

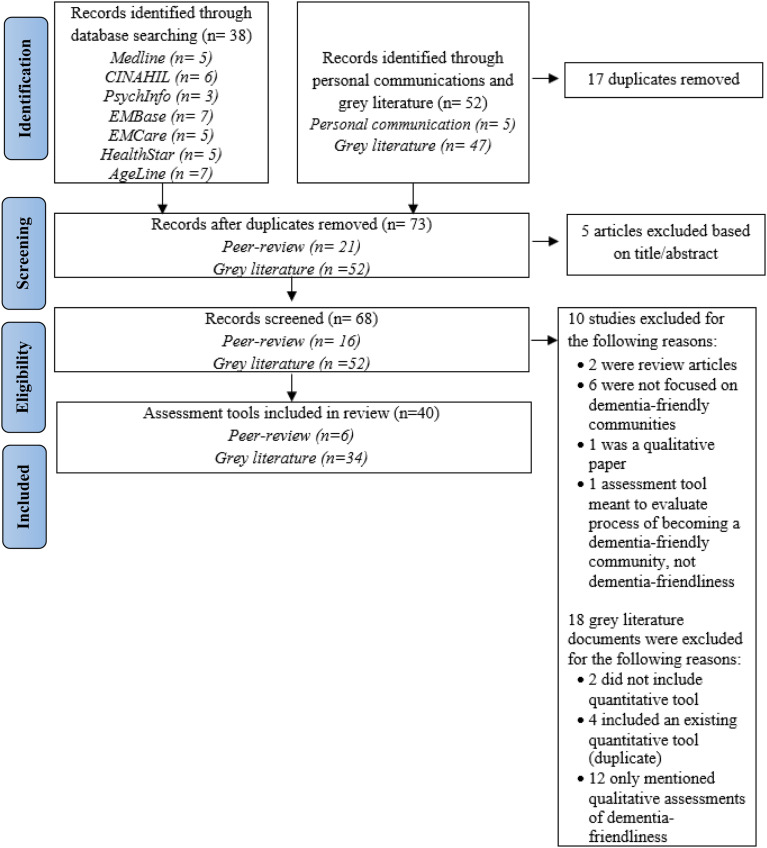

A total of 38 abstracts were identified in the database search. After the removal of duplicates, 21 articles remained. Five articles were excluded after title and abstract review. A total of 16 articles underwent full-text review. Four conflicts were identified at the full-text stage and a third reviewer was involved to resolve the conflicts. A total of 6 peer-reviewed articles were selected for final inclusion (Darlington et al., 2020; Fleming et al., 2017; Griffiths et al., 2018; Mitchell & Burton, 2006; Read et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2019) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA diagram of scoping review process.

A total of 42 grey literature sources were identified through the World Wide Web search. Four reports (Catenbury District Health Board, 2015; Dementia Australia, 2016; 2018; National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center, 2019) included multiple assessment tools (e.g., one checklist for indoor spaces and one for outdoor spaces). Each assessment tool was assessed independently and was considered as an individual source, for a total of 47 independent sources. After the exclusion of sources that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 31 sources remained. Seven of the sources mentioned the use of quantitative assessment tools but did not include the tool in their report. LGD contacted the authors of those reports and three of them shared their assessment tool with the research team (City of New Westminister, 2016; City of North Vancouver, 2016; City of Richmond, 2019). A total of 29 grey literature sources were deemed to meet the criteria for final inclusion (Figure 1).

Sixteen community representatives were contacted by LGD (Canada n = 5, New Zealand n = 1, Australia n = 2, the United Kingdom n = 5, and the United States n = 3). Five assessment tools were identified through this method and included in the review (Central Coast Council, 2017; Community Partners in Action Innisfail, 2020; Dementia-Friendly Rotorua Steering Group, 2017; Hamilton Council on Aging, 2020; National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center, 2019). None of the identified tools were proprietary tools under copyright. After compiling all sources, 40 unique tools that were developed to quantitatively assess the dementia-friendliness of a community were identified (Figure 1).

Characteristics of included tools

The 40 tools included were developed between 2006 and 2020, with 33 developed between 2016 and 2020. Table 1 provides a summary of the characteristics of the 40 tools identified. Eighteen of the tools are checklists for indoor and/or outdoor dementia-friendly environments, and twenty-two are related to living in the community with dementia or dementia attitudes and knowledge. Fourteen of the tools were developed in Australia, eight in the United States, eight in the United Kingdom, seven in Canada, two in New Zealand, and one in Taiwan. Approximately 50% of the tools were developed for “other” target populations (e.g., architects). The most frequent developers of tools were not-for-profit organizations (47.5%), followed by researchers (30%), and local government (22.5%). The development of the Dementia Community Attitudes Questionnaire (Read et al., 2020) was guided by the tripartite model of attitude (Breckler, 1984; Rosenberg, 1960). An existing theory or framework was not reported to have guided the development of any other of the tools identified.

Table 1.

Tool characteristics.

Involvement of people living with dementia in tool development

Nineteen of the assessment tools were developed with the input of people living with dementia. However, level of involvement varied. The development of two of the tools (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, 2017b; 2017a) was led by people living with dementia. Three of the tools (Alzheimer’s Australia NSW, 2011; Mitchell & Burton, 2006; Wu et al., 2019) were developed based on an initial consultation with people living with dementia. After the consultations, people living with dementia were engaged throughout the development of items and piloted the tool. Fourteen of the tools (Alzheimer Society of British Columbia, 2016; City of New Westminister, 2016; City of North Vancouver, 2016; City of Richmond, 2019; Community Partners in Action Innisfail, 2020; Darlington et al., 2020; Dementia-Friendly Rotorua Steering Group, 2017; Dementia Australia, 2018; Fleming et al., 2017; Hamilton Council on Aging, 2020; Read et al., 2020) were developed based on existing tools and relevant research and involved people living with dementia in the review of drafts. Six of the tools (ACT on Alzheimer’s, 2015; Griffiths et al., 2018; National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center, 2019) did no engage people living with dementia in tool development.

Assessment of dementia-friendly community domains

Understanding which DFC domains are currently being assessed can help determine whether existing tools are sufficiently comprehensive to be considered for use in assessing DFC features. This can be done by determining the number of items per dementia-friendly domain. Table 2 provides a summary of the total number of questions per tool, including the number of items per dementia-friendly domain, number of open-ended questions, number of demographic questions, and year when the tool was developed. The total number of questions varied between 6 and 113, with the minimum and maximum number of questions per domain ranging from 0 to 55, respectively. Some of the tools had an even distribution of questions per domain (see, e.g., Darlington et al., 2020), while others heavily weighted certain domains over others (see, e.g., Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, 2017b). Only one tool had questions related to the financial services domain (Dementia Friendly Community Marinette, 2016) and only three addressed the independent living (ACT on Alzheimer’s, 2015; Darlington et al., 2020; Dementia Australia, 2016) and emergency planning and first response (ACT on Alzheimer’s, 2015; Dementia Friendly Community Marinette, 2016; Hamilton Council on Aging, 2020) domains. None of the tools had questions that represented all domains of dementia-friendliness. The five domains covered by the greatest number of tools included: outdoor spaces and buildings; dementia awareness/attitudes; civic participation and engagement; transportation; and dementia-specific community activities/services. None of the tools included questions associated with domains of: legal and advanced care planning services; care throughout the continuum; and memory loss supports and services. Where used, open-ended questions included: what respondents had stopped doing because of their dementia; recommendations for making their community dementia-friendly; and perceived barriers to participation. Of the 14 tools that included demographic questions, only four (ACT on Alzheimer’s, 2015; Darlington et al., 2020; Hamilton Council on Aging, 2020; Harder+Copmany Community Research, 2016) included questions about ethnic background.

Table 2.

Summary of assessment tools included in the review.

| Assessment tool | Domains (numbers in each cell represent the number of items within each DFC domain in the tool) | Number of open-ended questions | Number of demographic questions | Total number of questions in tool | Year | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | Q | R | |||||

| 1. Dementia-friendly community indicators (Wu et al., 2019) | 4 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 33 | 2019 | ||||||||||||

| 2. A checklist for designing dementia-friendly outdoor environments (Mitchell & Burton, 2006) | 48 | 48 | 2006 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. Adolescent Attitudes Towards Dementia Scale (Griffiths et al., 2018) | 23 | 23 | 2017 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 4. Dementia-Friendly Communities Environment Assessment tool (Fleming et al., 2017) | 37 | 37 | 2017 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5. National evaluation of dementia-friendly communities (Darlington et al., 2020) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 42 | 2020 | ||||||||

| 6. Dementia Community Attitudes Questionnaire (Read et al., 2020) | 10 | 10 | 2020 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7. Alzheimer’s WA dementia friendly communities audit and planning tool (Alzheimer’s WA, 2016) | 14 | 8 | 6 | 18 | 2 | 48 | 2016 | |||||||||||||||

| 8. Dementia Friendly Community Survey, Marinette (Dementia Friendly Community Marinette, 2016) | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 24 | 2016 | ||||||||

| 9. Age and dementia friendly community survey, San Diego (Harder+Copmany Community Research, 2016) | 15 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 7 | 1 | 11 | 6 | 12 | 1 | 21 | 97 | 2016 | |||||||||

| 10. Is this outside public space dementia-inclusive? (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, 2017b) | 55 | 2 | 57 | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 11. Creating dementia-friendly communities: Outdoor areas and buildings (Dementia Australia, 2018) | 19 | 19 | 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 12. Creating dementia-friendly communities: Indoor areas (Dementia Australia, 2018) | 19 | 19 | 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 13. Creating dementia-friendly communities: Social engagement (Dementia Australia, 2018) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 16 | 2018 | ||||||||||||

| 14. Creating dementia-friendly communities: Employment, volunteering and study (Dementia Australia, 2018) | 11 | 1 | 12 | 2018 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 15. Is this inside public space dementia-inclusive? (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, 2017a) | 76 | 2 | 78 | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 16. Dementia-friendly community questionnaire Rotorua (Dementia-Friendly Rotorua Steering Group, 2017) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 19 | 2 | 2 | 19 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 62 | 2017 | ||||||||

| 17. Dementia-friendly outdoor environment checklist, BC (Alzheimer Society of British Columbia, 2016) | 40 | 40 | 2016 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 18. Good dementia-design checklist, Christchurch (Catenbury District Health Board, 2015) | 15 | 15 | 2015 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 19. Checklist for Transport Providers, Christchurch (Catenbury District Health Board, 2015) | 6 | 6 | 2015 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 20. Creating dementia-friendly communities: Outdoor environments (Dementia Australia, 2016) | 1 | 14 | 15 | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 21. Creating dementia-friendly communities: Indoor environments (Dementia Australia, 2016) | 18 | 18 | 2016 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 22. Creating dementia-friendly communities: Social engagement (Dementia Australia, 2016) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 2016 | ||||||||||||||

| 23. Dementia-friendly survey: community members (Dementia Australia, 2016) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 17 | 1 | 1 | 45 | 2016 | |||||||||

| 24. Dementia-friendly survey: Business (Dementia Australia, 2016) | 9 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 13 | 2016 | ||||||||||||||||

| 25. Dementia-friendly Richmond Public Engagement Survey (City of Richmond, 2019) | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 23 | 6 | 7 | 48 | 2019 | |||||||||||

| 26. Community survey Central Coast (Central Coast Council, 2017) | 1 | 2 | 31 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 13 | 57 | 2017 | ||||||||||||

| 27. Dementia and age-friendly outdoor design checklist (Alzheimer’s Australia NSW, 2011) | 10 | 5 | 2 | 17 | 2011 | |||||||||||||||||

| 28. Dementia friendly business self-assessment checklist (The Brenda Strafford Foundation, 2019) | 3 | 5 | 3 | 49 | 1 | 61 | 2019 | |||||||||||||||

| 29. Community-needs assessment (ACT on Alzheimer’s, 2015) | 6 | 6 | 2 | 9 | 3 | 13 | 34 | 27 | 2 | 7 | 4 | 113 | 2015 | |||||||||

| 30. Physical environment checklist (Alzheimer’s Society UK, 2017b) | 3 | 54 | 57 | 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 31. Dementia-Friendly North Shore: Public Perception Survey (City of North Vancouver, 2016) | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 10 | 2016 | |||||||||||||

| 32. Dementia-friendly New West community survey (City of New Westminister, 2016) | 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 14 | 8 | 35 | 2016 | ||||||||||||

| 33. Empowering dementia-friendly communities, Hamilton, Haldimand-Public Consultations (Hamilton Council on Aging, 2020) | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 44 | 2020 | |||||||

| 34. Checklist for dementia-friendly environments (Innovations in Dementia, 2012) | 15 | 15 | 2012 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 35. Dementia-Friendly Physical Environments Checklist (Dementia Action Alliance, n.d) | 20 | 20 | N/A | |||||||||||||||||||

| 36. Innisfail Dementia Friendly Community Questionnaire (Community Partners in Action Innisfail, 2020) | 6 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 18 | 2020 | ||||||||||||||

| 37. Brief Tool for Dementia-Friendly Education and Training Sessions-Individual Trainings: Pre-Workshop Questions (National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center, 2019) | 7 | 7 | 2019 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 38. Brief Tool for Dementia-Friendly Education and Training Sessions-Individual Trainings: Post-Workshop Questions (National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center, 2019) | 16 | 1 | 17 | 2019 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 39. Brief Tool for Dementia-Friendly Education and Training Sessions-Organizational or Sector Trainings: Pre-Workshop Questions (National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center, 2019) | 7 | 1 | 8 | 2019 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 40. Brief Tool for Dementia-Friendly Education and Training Sessions-Organizational or Sector Trainings: Post-Workshop Questions (National Alzheimer’s and Dementia Resource Center, 2019) | 19 | 1 | 20 | 2019 | ||||||||||||||||||

DFC domains: A) Transportation, B) Housing, C) Outdoor spaces and buildings, D) Businesses, E) Legal and advanced care planning services, F) Financial services, G) Dementia awareness/attitudes, H) Care throughout the continuum, I) Memory loss supports and services, J) Emergency planning and first response, K) Respect and social inclusion, L) Independent living, M) Civic participation and engagement, N) Dementia-specific community activities/services, O) Indoor spaces, P) Participation in leisure activities, Q) Healthcare, and R) Communication and information.

Psychometric properties

Only three tools (Fleming et al., 2017; Griffiths et al., 2018; Read et al., 2020) had validity and reliability information available. None reported responsiveness to change. Griffiths et al. (2018) reported internal consistency of three subscales (Personal Sacrifice α = .79; Empathy with People with Dementia α = .69; and Perceptions of Dementia α = .61) and convergent validity (r = .47, p < .001). Fleming et al. (2017) reported inter-rater reliability and internal consistency by assessing different “touch points” along a journey to a destination (approach to entry, entry space, route to the destination, destination, route from the destination). Inter-rater reliability ranged from r = .65–.90 and internal consistency from α = .59–.82. Read et al. (2020) reported internal consistency of three factors (Engagement = α 0.855; Challenges = α 0.785; and Decision-making α = 0.709). An expert reference group assessed the content validity of Read et al.’s (2020) scale, and face validity was assessed by asking participants (including people living with dementia) if the questions were acceptable and easily understood.

Uptake of identified assessment tools

We were only able to find uptake information for four of the tools (ACT on Alzheimer’s, 2015; Dementia Action Alliance, n.d.; Griffiths et al., 2018; Mitchell & Burton, 2006). Mitchell and Burton’s (2006) checklist for designing dementia-friendly outdoor environments was found to be used in one study (Biglieri, 2018). Biglieri (2018) investigated the financial feasibility of implementing Mitchell and Burton’s (2006) recommendations and concluded that applying recommendations was financially feasible. Three studies (Farina, Hughes, Griffiths, & Parveen, 2020; Farina, Griffiths, Hughes, & Parveen, 2020; Griffiths, Cheong, Saw, & Parveen, 2020) used Griffiths and colleagues Adolescent Attitudes Towards Dementia Scale (A-ADS; Griffiths et al., 2018). The scale was used to evaluate the impact of an education session on adolescents’ experiences and perceptions of dementia (Farina et al., 2020) and on pharmacy and medicine undergraduate students in Malaysia (Griffiths et al., 2020). In addition, the A-ADS scale was further validated and a brief version of the scale created (Farina et al., 2020). Table 3 provides a summary of studies that used these two tools.

Table 3.

Summary of studies that have used identified tools.

| Authors | Year | Title | Aim | Sample | Setting | Tool used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biglieri. | 2018 | Implementing dementia-friendly land use planning: An evaluation of current literature and financial implications for Greenfield development in suburban Canada | To validate the build environment recommendations made by Burton & Mitchel (2006) through planning and dementia literatures, as well as through financial feasibility and planning policy implementation analysis. | Planning and dementia literatures. Financial feasibility was assessed using pro forma analysis. | Town of Whitby, a midsize suburban municipality in Ontario, Canada. | Mitchell & Burton (2006) |

| Farina, Hughes, Griffiths & Parveen. | 2020 | Adolescents’ experiences and perceptions of dementia | To evaluate the impact of a Dementia Friends class (a 6-minute interactive class about dementia) on adolescents’ experiences and perceptions of dementia. | Adolescents in school years 9–13 (typically aged 13–18) | Four schools across Sussex, England | Griffiths et al. (2018) |

| Griffiths, Cheong, Saw & Parveen. | 2020 | Perceptions and attitudes towards dementia among university students in Malaysia | To evaluate the impact of a one-hour education session for pharmacy and medicine undergraduate students. | Pharmacy and medicine undergraduate students. | University in Malaysia. | Griffiths et al. (2018) |

| Farina, Griffiths, Hughes & Parveen. | 2020 | Measuring adolescent attitudes towards dementia: The revalidation and refinement of the A-ADS | To further validate the A-ADS and to investigate if it was possible to reduce the number of items in the A-ADS without affecting its validity. | Adolescents (ages 13–18) attending secondary schools. | South East England secondary schools. | (Griffiths et al., 2018) |

According to what we found in our searches, the ACT on Alzheimer’s (2015) Community Needs Assessment has been used by approximately 40 communities in the United States and the Dementia-Friendly Physical Environments Checklist by the Dementia Action Alliance (Dementia Action Alliance, n.d.) by approximately 49 establishments in the United Kingdom. Establishments included medical practices, religious facilities, retirement homes, retail businesses, airports, libraries, recreation centers, and museums. Lastly, it is worth noting that the checklist for dementia-friendly environments developed by Innovations in Dementia (2012) informed the development of the Dementia Australia (2018) and Canterbury District Health Board (2015) checklists. Similarly, the checklist by the Alzheimer Society of British Columbia (Alzheimer Society of British Columbia, 2016) was informed by Mitchell and Burton’s (2006) checklist.

Dementia knowledge attitude scales

In our search, we identified assessment tools designed to measure dementia knowledge and attitudes towards people living with dementia (Annear et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2018; Lundquist & Ready, 2008; O’Connor & McFadden, 2010; Read et al., 2020; Shanahan et al., 2013). Read et al.’s (2020) Dementia Community Attitudes Questionnaire was the only one included in the scoping review as it was specifically developed to support DFC initiatives.

Consultation

LGD held three consultation sessions. Seven stakeholders participated in the consultations. Participants included healthcare providers (a geriatrician, a nurse, and a social worker), two researchers, an executive of an Alzheimer Society, and a community member living with dementia. Significance of the findings was discussed. Participants recognized that most of the identified tools were developed by not-for-profit organizations and highlighted the need for partnerships between people living with dementia, researchers and not-for-profit organizations. Similarly, participants identified the need for funding bodies to support quality improvement efforts so that appropriate resources are allocated to evaluation. In addition, in the three consultation sessions, the importance of co-designing tools with people living with dementia was highlighted. Participants raised the concern that in not involving people living with dementia in all stages of tool development there is a risk that questions included in the tool may not reflect community priorities, as identified by people living with dementia.

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to identify and examine quantitative tools that assess the dementia-friendliness of a community. Forty tools that quantitatively assess the dementia-friendliness of a community were identified. Most of the identified tools (82.5%) were developed between 2016 and 2020, making it evident that there is an increased interest in having tools that assess domains of dementia-friendliness. In Canada (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2019), the United States (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2018), the United Kingdom (Department of Health, 2015), Australia (Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council, 2015), and New Zealand (Alzheimers New Zealand, 2015), governments have identified DFCs as an area of focus in national dementia plans, which has resulted in an emergence of DFC initiatives. However, the emergence of DFC initiatives has led to an overlap in efforts, where individual communities create a new tool, with little awareness of similar tools already in existence. In addition, majority of the identified tools do not meet the standards of rigorous methodology for survey construction.

The tools identified in this review can be divided into three categories, specifically, tools that assess: the built environment; dementia awareness and attitudes; and community needs of people with dementia.

Built environment

DFC initiatives have been critiqued for focusing on attributes of the built environment, as opposed to the social environment (Førsund et al., 2018; Hebert & Scales, 2019; Lin et al., 2015). This critique is supported by the number of checklists (45%) developed to enhance indoor and outdoor physical spaces (Alzheimer’s Australia NSW, 2011; Alzheimer’s Society UK, 2017b; Alzheimer’s WA, 2016; Alzheimer Society of British Columbia, 2016; Catenbury District Health Board, 2015; Dementia Action Alliance, n.d.; Dementia Australia, 2018; Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, 2017b, 2017a; Innovations in Dementia, 2012; Mitchell & Burton, 2006; The Brenda Strafford Foundation, 2019). Enhancing the built environment improves accessibility making it easier for people with dementia to navigate public spaces. However, to support independence and safety, enhancement of the social environment is also needed. For example, it is estimated that 30%–70% of people with dementia become lost at least once during the course of the disease (Bowen et al., 2011; Pai & Lee, 2016). In qualitative studies conducted in the United Kingdom (Bartlett & Brannelly, 2019) and in Sweden (Olsson et al., 2013), people living with dementia were asked how they deal with becoming confused when navigating familiar spaces. In both studies, participants reported relying on community members to help them find their way home if they were to get lost (Bartlett & Brannelly, 2019; Olsson et al., 2013), emphasizing the need for dementia awareness to reduce stigma, and public education on how to support people living with dementia. Only two of the tools that assess the built environment (Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project, 2017a; 2017b) include items related to the social environment (e.g., staff seem friendly). Although the built environment may be easier to assess than the social environment, we believe that tools that assess the dementia-friendliness of the built environment should also consider social aspects of the environment as this would provide a more comprehensive assessment of the dementia-friendliness of public spaces.

Fleming et al.’s (2017) Dementia-Friendly Communities Environment Assessment Tool is the only tool in this category that has been assessed for reliability and validity. None of the tools have been assessed for responsiveness to change. To ensure that tools that assess the built environment are valid, reliable and can detect change, future research about these tools should focus on conducting psychometric testing. This would increase their utility in research and in evaluation of DFC initiatives.

Dementia awareness and attitudes

Two peer-reviewed tools (Griffiths et al., 2018; Read et al., 2020) that assess dementia awareness and attitudes were identified and both have been assessed for reliability of validity. Read et al.’s (2020) Dementia Community Attitudes Questionnaire is a ten-item questionnaire that assesses community attitudes towards people living with dementia. Read et al. (2020) conducted preliminary psychometric testing and had promising results; however, to establish convergent validity, further testing is needed. Similarly, Griffith et al. (2018) conducted preliminary psychometric testing on the Adolescent Attitudes Towards Dementia Scale with adolescents in the United Kingdom, but further validation is needed with adolescents from other countries. Future research on tool development for the assessment of dementia-friendliness should focus on conducting psychometric testing of these scales, including testing for responsiveness to change.

To increase the relevance and utility of research outcomes, engagement of people with dementia in research has become increasingly common (Gove et al., 2017; Miah et al., 2019). Similarly, involvement of people with dementia is a core element of DFC initiatives (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016a). Six of the identified tools were developed without input from people with dementia. These six tools primarily assess attitudes towards dementia and outcomes of education and training sessions. Even though tools that assess dementia awareness and/or attitudes towards people with dementia are developed for the general public or a specific audience (such as healthcare providers), to ensure that items in the tool reflect the stigma that people with dementia experience, people living with dementia should be involved in their development.

As described by Alzheimer’s Disease International (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016a), reduction of social stigma surrounding dementia and empowerment of people with dementia are two key objectives of DFC initiatives; therefore, the development and uptake of valid and reliable tools that measure stigma towards people living with dementia is important. Five tools identified in the search (Annear et al., 2017; Baker et al., 2018; Lundquist & Ready, 2008; O’Connor & McFadden, 2010; Shanahan et al., 2013) were not included in the final review as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. However, these tools could be used to evaluate dementia-friendly projects aimed at targeting stigma and raising awareness of dementia. Other reviews have been conducted on the use of dementia knowledge scales to support dementia awareness campaigns and education programs (Resciniti et al., 2020; Spector et al., 2012; Sullivan & Mullan, 2017). Although these tools can support the evaluation of increased knowledge of dementia and stigma reduction, to increase our understanding of the impact of initiatives that address dementia attitudes and awareness, future research should focus on evaluating whether and how those initiatives impact the well-being of people living with dementia, including increased community engagement since stigma can often impact social inclusion (Hung et al., 2021).

Community needs of people with dementia

Two peer-reviewed tools (Read et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2019) that assess community needs of people with dementia were identified. Neither tool evaluates all DFC domains nor have they been assessed for validity, reliability, or responsiveness to change. After reviewing the tool by Wu et al. (2019), it was determined that the authors created a list of DFC indicators rather than an assessment tool. These indicators could be used as a basis for tool development. Read et al.’s (2020) tool was developed to assess the experience of living with dementia in a community with an existing dementia-friendly initiative, so it would not be suitable for a baseline assessment of dementia-friendliness.

Three of the DFC domains that we had included in our data extraction tool are not assessed by any of the identified tools: legal and advanced care planning services; care throughout the continuum; and memory loss supports and services. Thus, based on our inclusion criteria, none of the identified tools could be used to assess all DFC domains; stakeholders that wish to assess all DFC domains would need to use multiple assessment tools. In addition, only one tool (Dementia Friendly Community Marinette, 2016) included a question that assessed the financial services domain. In two studies—a systematic review and meta-analysis (Curnow et al., 2019) and a scoping review (Morrisby et al., 2018)—that investigated the evidence of needs of people with dementia, memory and money management were identified as two of the top five needs. Given that memory and money management support have been identified by people with dementia as priorities, it is important for tools aimed at assessing community needs of people with dementia to evaluate if these priority needs are being met by existing programs and services. Similarly, it is estimated that less than 40% of people with dementia worldwide have the opportunity to participate in advanced care planning (Sellars et al., 2019). In a recent umbrella review of effectiveness of advanced care planning for people with dementia (Wendrich-van Dael et al., 2020), advanced care planning was found to be associated with decreased hospitalizations and increased concordance between care received and prior wishes. To ensure that people with dementia can participate fully in decisions that affect them from point of diagnosis to palliative care, assessment tools should include questions related to legal and advanced care planning services.

We encourage people living with dementia, national Alzheimer Society associations, and researchers to collaborate on developing and validating questionnaires that assesses different domains of dementia-friendliness. This collaboration would ensure that questions reflect community priorities of people living with dementia and it could also enhance uptake of assessment tools. An important objective of DFCs is to ensure that the community needs of people with dementia are being met and respected, one way of doing that is by recognizing and respecting their human rights (Alzheimer’s Disease International, 2016a); therefore, we encourage tool development to be guided by existing charters of rights for people with dementia (see, e.g., Charter of Rights for People with Dementia and their Carers in Scotland; Alzheimer Scotland, 2009; Canadian Charter of Rights for people with dementia; Alzheimer Society of Canada, 2018). In addition, only 14 of the tools included demographic questions, of which only four included questions related to ethnic background (ACT on Alzheimer’s, 2015; Darlington et al., 2020; Hamilton Council on Aging, 2020; Harder+Copmany Community Research, 2016). Individuals from ethnic minorities have been found to have higher prevalence of dementia (House of Commons All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia, 2013), to experience shame and stigma of dementia within their communities (Mukadam et al., 2011), and to be at a higher risk of underdiagnosis than white Caucasians (Tsoy et al., 2021). To ensure that DFC initiatives address the needs of ethnic minorities, we encourage that tools include demographic questions that capture participants’ ethnic background. When analyzing the data, comparing responses by ethnicity would provide a better understanding of community needs of individuals from ethnic minorities. These results could be used to develop a targeted DFC action plan that adequately addresses the needs of ethnic minorities.

Need for a dementia-friendly community framework

The three domains not covered by any of the identified tools are also domains not included in the age-friendly community framework proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO; World Health Organization, 2007). Out of the dementia-specific domains included in this review, dementia awareness/attitudes and dementia-specific community activities/services are the two most often covered by the tools (covered in 20 and 14 tools, accordingly). However, the other dementia-specific domains (emergency planning and first response; independent living; financial services; legal and advanced care planning services; care throughout the continuum; and memory loss supports and services) are rarely or not at all covered. Research shows that not all age-friendly communities are necessarily dementia-friendly (Turner & Morken, 2016); therefore, tools meant to assess the degree to which communities are dementia-friendly need to expand beyond the eight age-friendly community domains proposed by the WHO. An absence of an overarching framework equivalent to the one available for communities pursing age-friendliness has resulted in communities around the world using various frameworks and approaches to develop their DFC initiative (Turner & Morken, 2016). Thus, a comprehensive DFC framework is needed to support a systematic approach to the development and assessment of DFC initiatives, including the development of a quantitative tool that captures all DFC domains identified in the framework.

It is worth noting that even though we did not include a domain associated with caregiver support, we acknowledge that it is important for DFC initiatives to consider enhancing supports for caregivers. Approximately 60% of people with dementia live at home and require support while living there (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2018; Harrison et al., 2019). Caregivers of people with dementia have reported higher levels of stress than caregivers of persons with a physical disability (Ory et al., 1999; Sörensen & Conwell, 2011). Moreover, in a systematic review and meta-analysis (Toot et al., 2017), caregiver burden was found to be associated with an increased risk of nursing home placement for people with dementia. Given the significant impact that caregiver support has on dementia care and the health of the caregiver, we encourage the inclusion of questions related to availability and quality of existing caregiver services and supports in DFC assessment tools.

Although in this scoping review we focused on quantitative assessment tools, we believe that a mixed-methods approach (e.g., surveys and interviews) would provide the most comprehensive approach to the assessment of dementia-friendliness in a community. A qualitative assessment would complement quantitative data by capturing more rich information about the distinct cultural, ethnic and gender factors that impact the experience of living with dementia in the community. A mixed-methods approach also provides the opportunity to engage people that may find it difficult to complete a quantitative assessment or that prefer to voice their opinions in other ways (such as through interviews), increasing accessibility and representation of participants.

Limitations

This review was limited to English-language, peer-reviewed and grey literature. While a rigorous search method was performed, it is possible that relevant literature was missed. We limited our outreach to community representatives from primarily English-Speaking countries (Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand); it is possible that relevant community surveys in other countries or not known to our representatives were missed. Moreover, all the tools included in this review were developed in high-income countries, which limits the transferability of the findings to low- and middle-income countries. The community needs of individuals with dementia who live in low- and middle-income countries may differ from the needs of people living in high-income countries, as well as types of DFC interventions that are implemented; different assessment tools may therefore be needed to assess the dementia-friendliness of those communities.

Conclusion

In this scoping review, we identified 40 tools that assess DFC features (built environment, dementia awareness and attitudes, and community needs). Thirty-four of the identified tools were found in the grey literature, suggesting that there is a lack of published peer-reviewed research on quantitative assessment tools to support the evaluation of dementia-friendliness of a community. None of the identified tools were deemed comprehensive enough for the assessment of community needs of people with dementia. In an effort to minimize the number of tools available and encourage a more systematic and strategic approach to the advancement of DFCs, future research in this domain should be focused on adapting existing tools in order to include all DFC domains and on conducting psychometric testing to allow for comparisons to be made within and across communities. In addition, to ensure that tools developed are relevant, accessible, and useful, we recommend the involvement of people with dementia in tool development; the inclusion of demographic questions that capture the diversity of community members; and the development of partnerships between researchers, people with dementia, and national Alzheimer Society associations for the development, uptake, and psychometric testing of the tools.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Julie Richardson for her constructive criticism of the scoping review protocol.

Biography

Laura Garcia Diaz, MSc: Dual degree (MSc OT, PhD) candidate, School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University. Laura Garcia Diaz is a dual degree candidate (MSc Occupational Therapy/PhD Rehabilitation Sciences) in the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University. To support a more systematic approach to the development, implementation, and evaluation of dementia-friendly communities, Laura’s work focuses on evaluation research.

Evelyne Durocher, OT, PhD: Assistant Professor, School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University. Evelyne Durocher is Occupational Therapist and Assistant Professor in the School of Rehabilitation Science at McMaster University. Her current research focuses on ethics and rehabilitation practice, specifically relating to questions of justice, vulnerability and equity in healthcare services for older adults. Her goal is to improve the health and social care experiences of older adults, family members, and healthcare professionals.

Paula Gardner, PhD: Asper Research Chair in Communications and Associate Professor, Department of Communication Studies and Media Arts, McMaster University. Paula Gardner is an associate professor in the Department of Communication Studies and Multimedia, the Asper Chair in Communications, and the director of the Pulse Lab at McMaster University. Her research interests include feminist media studies, digital culture, and biometric technological practices. Paula’s media background allows her to explore research using various production mediums. The ABLE project (Arts Based Therapies Enabling Longevity for Geriatric Outpatients) brings together researchers from five McMaster Faculties to develop technologies that will enhance the cognitive, physical and emotional health of frail older adults.

Carrie McAiney, PhD: Associate Professor, School of Public Health Sciences, University of Waterloo, Schlegel Research Chair in Dementia, Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging. Carrie McAiney is Associate Professor in the School of Public Health Sciences at the University of Waterloo, and the Schlegel Research Chair in Dementia and Scientific Director of the Murray Alzheimer Research and Education Program at the Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging. As a health services researcher, Carrie works collaboratively with persons living with dementia, family care partners, providers and organizations to co-design, implement and evaluate interventions and approaches to enhance the well-being of persons living with dementia and family and friend care partners.

Vishal Mokashi, Undergraduate student, School of Life Sciences, McMaster University. Vishal Mokashi is an undergraduate student in the Faculty of Life Science at McMaster University. He is currently pursuing his Bachelor of Science. His current research interests include the evaluation of dementia-friendly communities, validating algorithms to identify individuals living with dementia and identifying socioeconomic factors that can potentially lead to caregiver burnout.

Lori Letts, OT, PhD, Professor, School of Rehabilitation Science, McMaster University. Lori Letts is Professor in the School of Rehabilitation at McMaster University. Lori’s current research focuses on older adults with chronic illnesses and finding ways to help them to live with and manage their conditions while being active community-dwellers. Lori’s research has her involved in work in primary care and other community settings. She is also involved in research to identify and intervene in preventative ways so that people’s engagement in occupation and health is optimized.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Laura Garcia Diaz https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6990-2107

Carrie McAiney https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7864-344X

References

- ACT on Alzheimer’s . (2015). Dementia friendly communities toolkit: Community needs assesment. https://www.actonalz.org/assess [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Scotland . (2009). Charter of rights for people with dementia and their carers in Scotland. https://www.alzscot.org/sites/default/files/images/0000/2678/Charter_of_Rights.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Society of British Columbia . (2016). Dementia-friendly communities local government toolkit. https://archive.alzheimer.ca/sites/default/files/files/bc/advocacy-and-education/dfc/dfc_toolkit_v.jan2016.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Society of Canada . (2018). Canadian charter of rights for people with dementia. https://archive.alzheimer.ca/sites/default/files/files/national/advocacy/charter/as_charter-of-rights-for-people-with-dementia.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer Society of Saskatchewan . (2017). Dementia friendly communities: Municipal toolkit. https://healthdocbox.com/Senior_Health/68171370-Dementia-friendly-communities-municipal-toolkit.html [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Australia . (2014). Living with dementia in the community: Challenges and opportunities. https://www.dementia.org.au/sites/default/files/DementiaFriendlySurvey_Final_web.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Australia NSW . (2011). Building dementia and age-friendly neighbourhoods. https://www.dementiaaction.org.uk/assets/0000/8251/20110803-NSW-PUB-DementiaFriendlyNeighbourhoods.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International . (2016. a). Dementia friendly communities: Key principles. https://www.alzint.org/u/dfc-principles.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International . (2016. b). World Alzheimer report 2016 improving healthcare for people living with dementia coverage, QualIty and costs now and in the future. www.daviddesigns.co.uk [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Disease International . (2017). Dementia friendly communities: Global developments. https://www.alzint.org/u/dfc-developments.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimers New Zealand . (2015). Achieving a dementia friendly New Zealand. https://www.alzheimers.org.nz/getattachment/Who-We-Are/About-us/Alz-NZ-Strategy-Achieving-a-Dementia-Friendly-NZ.pdf/ [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society UK . (2013). Building dementia-friendly communities: A priority for everyone. https://actonalz.org/sites/default/files/documents/Dementia_friendly_communities_full_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society UK . (2017. a). Become a dementia friend. https://www.dementiafriends.org.uk/WEBArticle?page=become-dementia-friend [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society UK . (2017. b). Dementia-friendly business guide. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/get-involved/dementia-friendly-communities/making-organisations-dementia-friendly/businesses [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Society UK . (2017. c). What is a dementia friends champion? https://www.dementiafriends.org.uk/WEBArticle?page=what-is-a-champion#.X9fgSthKhPY [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s WA . (2016). Guidelines for the development of dementia-friendly communities: Alzheimer’s WA dementia friendly communities audit and planning tool . https://www.alzheimerswa.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/Webready-DFC-guidelines-rebrand-July-2017_V2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Annear M. J., Toye C., Elliott K. E. J., McInerney F., Eccleston C., Robinson A. (2017). Dementia knowledge assessment scale (DKAS): Confirmatory factor analysis and comparative subscale scores among an international cohort. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 168. 10.1186/s12877-017-0552-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O’Malley L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Australian Health Ministers Advisory Council . (2015). National framework for action on dementia 2015-2019. https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/01/national-framework-for-action-on-dementia-2015-2019_0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Baker J. R., Low L. F., Goodenough B., Jeon Y. H., Tsang R. S. M., Bryden C., Hutchinson K. (2018). The kids insight into dementia survey (KIDS): Development and preliminary psychometric properties. Aging and Mental Health, 22(8), 947–953. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1320703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett R., Brannelly T. (2019). On being outdoors: How people with dementia experience and deal with vulnerabilities. Social Science and Medicine, 235, 112336. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biglieri S. (2018). Implementing dementia-friendly land use planning: An evaluation of current literature and financial implications for greenfield development in suburban Canada. Planning Practice & Research, 33(3), 264–290. 10.1080/02697459.2017.1379336 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen M. E., Mckenzie B., Rowe M. A. (2011). Prevalence of and antecedents to dementia-related missing incidents in the community. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 31(6), 406–412. 10.1159/000329792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckler S. J. (1984). Empirical validation of affect, behavior, and cognition as distinct components of attitude. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47(6), 1191–1205. 10.1037/0022-3514.47.6.1191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckner S., Darlington N., Woodward M., Buswell M., Mathie E., Arthur A., Lafortune L., Killett A., Mayrhofer A., Thurman J., Goodman C. (2019). Dementia friendly communities in England: A scoping study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(8), 1235–1243. 10.1002/gps.5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canadian Institute for Health Information . (2018). Dementia in Canada. https://www.cihi.ca/en/dementia-in-canada [Google Scholar]

- Catenbury District Health Board . (2015). Developing a dementia-friendly Christchurch: Perspectives of people with dementia. https://ageconcerncan.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Developing_a_Dementia-Friendly_Christchurch.pdf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Central Coast Council . (2017). Dementia-friendly central Coast framework. https://www.centralcoast.tas.gov.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Dementia-Friendly-Central-Coast-Framework.pdf [Google Scholar]

- City of Burnaby . (2017). Burnaby dementia-friendly community action plan. https://www.burnaby.ca/Assets/Burnaby+Dementia-Friendly+Community+Action+Plan.pdf [Google Scholar]

- City of New Westminister . (2016). Dementia-friendly community action plan 2016. https://www.newwestcity.ca/database/files/library/City_of_New_West_Dementia_Friendly_Community_Action_Plan_Report_2016_8_2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- City of North Vancouver . (2016). Dementia-friendly North shore action plan. https://www.cnv.org/city-services/planning-and-policies/initiatives-and-policies/dementia-friendly-north-shore-action-plan#:∼:text=The goal of the Dementia,as possible in our community [Google Scholar]

- City of Richmond . (2019). Dementia-friendly community plan. https://www.richmond.ca/__shared/assets/Dementia-Friendly_Community_Action_Plan_201954645.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Community Partners in Action Innisfail . (2020). Innisfail dementia friendly community questionnaire. Unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- Courtney-Pratt H., Mathison K., Doherty K. (2018). Distilling authentic community-led strategies to support people with dementia to live well. Community Development, 49(4), 432–449. 10.1080/15575330.2018.1481443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curnow E., Rush R., Maciver D., Górska S., Forsyth K., Orska S. G. (2019). Exploring the needs of people with dementia living at home reported by people with dementia and informal caregivers: a systematic review and Meta-analysis. Aging & Mental Health, 25(3), 397–407. 10.1080/13607863.2019.1695741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darlington N., Arthur A., Woodward M., Buckner S., Killett A., Lafortune L., Mathie E., Mayrhofer A., Thurman J., Goodman C. (2020). A survey of the experience of living with dementia in a dementia-friendly community. Dementia (London, England), 20(5), 1711–1722. 10.1177/1471301220965552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Action Alliance . (n.d.). Dementia friendly physical environments checklist. https://www.dementiaaction.org.uk/assets/0000/4336/dementia_friendly_environments_checklist.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Australia . (2016). Creating dementia-friendly communities: A toolkit for local governments. https://www.dementia.org.au/sites/default/files/NATIONAL/documents/Dementia-friendly-communities-toolkit-for-local-government.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Australia . (2018). Creating dementia-friendly communities: Community toolkit. https://www.dementiafriendly.org.au/sites/default/files/resources/The-Dementia-friendly_Community-Toolkit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project . (2017. a). Is this inside public space dementia-inclusive? A checklist for use by dementia groups. https://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Inside-checklist.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project . (2017. b). Is this outside public space dementia-inclusive? A checklist for use by dementia groups. https://www.dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/Outside-checklist.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Dementia Friendly America . (2015). https://www.dfamerica.org/

- Dementia Friendly Community Marinette . (2016). Dementia friendly community survey. http://dfcwi.com/dementia-friendly-community-survey/ [Google Scholar]

- Dementia-Friendly Rotorua Steering Group . (2017). Building a dementia-friendly community: First steps for a dementia-friendly Rotorua. https://www.rotorualakescouncil.nz/Rotorua2030/portfolios/people/Documents/Final_Dementia-friendly Rotorua Report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health . (2015). Prime Minister’s challenge on dementia 2020 implementation plan. www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/ [Google Scholar]

- Farina N., Griffiths A. W., Hughes L. J., Parveen S. (2020. b). Measuring adolescent attitudes towards dementia: The revalidation and refinement of the A-ADS. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(2), 374–385. 10.1177/1359105320953479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farina M., Hughes L., Griffiths A., Parveen S. (2020. a). Adolescents’ experiences and perceptions of dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 24(7), 1175–1181. 10.1080/13607863.2019.1613343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming R., Bennett K., Preece T., Phillipson L. (2017). The development and testing of the dementia friendly communities environment assessment tool (DFC EAT). International Psychogeriatrics, 29(2), 303–311. 10.1017/S1041610216001678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Førsund L. H., Grov E. K., Helvik A. S., Juvet L. K., Skovdahl K., Eriksen S. (2018). The experience of lived space in persons with dementia: A systematic meta-synthesis. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 33. 10.1186/s12877-018-0728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadotti I., Vieira E., Magee D. (2006). Importance and clarification of measurement properties in rehabilitation. Revista Brasileira de Fisioterapia, 10(2), 137–146. 10.1590/s1413-35552006000200002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gove D., Diaz-Ponce A., Georges J., Moniz E., Moniz-Cook E., Mountain G., Chattat R., Europe A. (2017). Alzheimer Europe’s position on involving people with dementia in research through PPI (patient and public involvement). Aging & Mental Health, 22(6), 723–729. 10.1080/13607863.2017.1317334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A. W., Cheong W. L., Saw P. S., Parveen S. (2020). Perceptions and attitudes towards dementia among university students in Malaysia. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 1–7. 10.1186/s12909-020-1972-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths A. W., Parveen S., Shafiq S., Oyebode J. R. (2018). Development of the adolescent attitudes towards dementia scale (A-ADS). International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(8), 1139–1145. 10.1002/gps.4907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton Council on Aging . (2020). Empowering dementia-friendly communities: Hamilton, Haldimand. https://coahamilton.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/HCOA_WWH_EN_June2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Harder+Copmany Community Research . (2016). Age and dementia friendly community survey. https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/Age-and-Dementia-Friendly-San-Diego-Baseline-Survey-V2_Long-Version_20....pdf [Google Scholar]

- Harrison K. L., Ritchie C. S., Patel K., Hunt L. J., Covinsky K. E., Yaffe K., Smith A. K. (2019). Care settings and clinical characteristics of older adults with moderately severe dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(9), 1907–1912. 10.1111/jgs.16054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert C. A., Scales K. (2019). Dementia friendly initiatives: A state of the science review. Dementia, 18(5), 1858–1895. 10.1177/1471301217731433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heward M., Innes A., Cutler C., Hambidge S. (2017). Dementia-friendly communities: challenges and strategies for achieving stakeholder involvement. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 858–867. 10.1111/HSC.12371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House of Commons All-Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia, S. (2013). Dementia does not discriminate: The experiences of black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/appg_2013_bame_report.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hung L., Hudson A., Gregorio M., Jackson L., Mann J., Horne N., Berndt A., Wallsworth C., Wong L., Phinney A. (2021). Creating dementia-friendly communities for social inclusion: A scoping review. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 7, 1–13. 10.1177/23337214211013596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husted J. A., Cook R. J., Farewell V. T., Gladman D. D. (2000). Methods for assessing responsiveness: A critical review and recommendations. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(5), 459–468. 10.1016/S0895-4356(99)00206-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Innovations in Dementia . (2012). Developing dementia-friendly communities: Learning and guidance for local authorities. https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/developing-dementia-frien-411.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Kerr J., Rosenberg D., Frank L. (2012). The role of the built environment in healthy aging: Community design, physical activity, and health among older adults. Journal of Planning Literature, 27(1), 43–60. 10.1177/0885412211415283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Levac D., Colquhoun H., O’Brien K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 169. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin S.-Y., Marcus Lewis F., Williamson J. (2015). Dementia friendly, dementia capable, and dementia positive: Concepts to prepare for the future. Gerontologist, 55(2), 237–244. 10.1093/geront/gnu122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist T. S., Ready R. E. (2008). Young adult attitudes about Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 23(3), 267–273. 10.1177/1533317508317818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]