Abstract

Getah virus (GETV) is a mosquito-borne virus of the genus Alphavirus in the family Togaviridae and, in recent years, it has caused several outbreaks in animals. The molecular basis for GETV pathogenicity is not well understood. Therefore, a reverse genetic system of GETV is needed to produce genetically modified viruses for the study of the viral replication and its pathogenic mechanism. Here, we generated a CMV-driven infectious cDNA clone based on a previously isolated GETV strain, GX201808 (pGETV-GX). Transfection of pGETV-GX into BHK-21 cells resulted in the recovery of a recombinant virus (rGETV-GX) which showed similar growth characteristics to its parental virus. Then three-day-old mice were experimentally infected with either the parental or recombinant virus. The recombinant virus showed milder pathogenicity than the parental virus in the mice. Based on the established CMV-driven cDNA clone, subgenomic promoter and two restriction enzyme sites (BamHI and EcoRI) were introduced into the region between E1 protein and 3′UTR. Then the green fluorescent protein (GFP), red fluorescent protein (RFP) and improved light-oxygen-voltage (iLOV) genes were inserted into the restriction enzyme sites. Transfection of the constructs carrying the reporter genes into BHK-21 cells proved the rescue of the recombinant reporter viruses. Taken together, the establishment of a reverse genetic system for GETV provides a valuable tool for the study of the virus life cycle, and to aid the development of genetically engineered GETVs as vectors for foreign gene expression.

Keywords: Getah virus (GETV), Reverse genetic system, Expression vector

Highlights

-

•

Generation and recovery of a CMV-driven infectious cDNA clone of GETV isolate, GX201808 (pGETV-GX).

-

•

The recombinant virus showed milder pathogenicity than the parental virus in a mouse model.

-

•

The Getah virus infectious clone can be used as a vector for expressing reporter genes.

1. Introduction

Getah virus (GETV) was first isolated from Culex mosquitoes in Malaysia in 1955 (Porterfield, 1975), and it has been found in a variety of mosquito and animal species (Bannai et al., 2016; Bryant et al., 2005; Chang et al., 2006; Kamada et al., 1980; Ksiazek et al., 1981; Li et al., 2017b; Nemoto et al., 2015; Sugiyama et al., 2009; Weaver, 2005). GETV can cause clinical symptoms such as transient fever, rash and swollen legs in horses (Brown and Timoney, 1998; Kamada et al., 1980; Sentsui and Kono, 1985) and it has also been known to cause reproductive disorders in pregnant sows as well as fever, loss of appetite, diarrhea and other symptoms including death in piglets (Kumanomido et al., 1988; Shibata et al., 1991; Yago et al., 1987; Yang et al., 2018). Recent reports indicate that it can also cause fever in cattle (Liu et al., 2019) and lethal infections in blue foxes (Shi et al., 2019). In China, GETV was first identified from mosquitos in Hainan in 1964 (Li et al., 1992), since then mosquito-bearing GETVs have been detected in many provinces (Li et al., 2017b). Serological surveys have shown that infections have occurred in multiple vertebrate species, including pigs (Ren et al., 2020; Xing et al., 2020; Yang et al., 2018), horses (Lu et al., 2019), cattles (Liu et al., 2019), blue foxes (Shi et al., 2019) and poultry (Li et al., 2019).

GETV belongs to the genus Alphavirus in the family Togaviridae (Fukunaga et al., 2000). Its genome is a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA of approximately 11.7 kb in length with the genome organization of an alphavirus from 5′ to 3': 5′ untranslated region (UTR), open reading frame (ORF) 1, 26 subgenomic promoter (SGP), ORF2, and 3′UTR (Zhai et al., 2008). The ORF1, situated within two-thirds of the 5′ of the genome, encodes four nonstructural proteins (nsp1–4) that comprise the viral transcriptase-replicase complex. The ORF2, which is in frame the one-third of the 3′ end of the genome, encodes the viral structural proteins (C–6K-E2-E3-E1) under the control of the 26SGP, and these are translated from sub-genomic (26S) RNA (Gould et al., 2010; Pfeffer et al., 1998).

At present, the knowledge regarding GETV tropism and pathogenesis is limited. Little progress has been made toward the development of rapid and quantitative tools to study the various aspects of the virus life cycle and viral determinants of GETV pathogenesis. Reverse genetics is a powerful tool that has been used to decipher the biological properties of viruses and infectious full-length cDNA clones have been established for several alphaviruses, such as Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus, Ross River virus, Semliki Forest virus, Sindbis virus, Chikungunya virus and Rubella virus (Anishchenko et al., 2004; Davis et al., 1989; Kuhn et al., 1991; Liljestrom et al., 1991; McKnight et al., 1996; Rice et al., 1987; Schoepp et al., 2002; Simpson et al., 1996; Vanlandingham et al., 2005; Wang et al., 1994).

In a previous study, we were able to isolate a swine-originated GETV strain (GX201808) from pregnant sows exhibiting reproductive disorders in 2018 (Ren et al., 2020). Here, we report the establishment of a full-length infectious cDNA clone based on the previously isolated GETV, GX201808. Using the established CMV-driven cDNA clone, a reporter expression cassette containing a sub-genomic promoter (26SGP) and GFP, RFP or iLOV was inserted to the region between E1 protein and the 3′UTR. The establishment of a reverse genetic system of GETV provides a new mean for further study of this virus and also can be used as a vector for the expression of heterologous genes.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell, virus, plasmids and antibodies

PK-15 and BHK-21 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) as described in our previous study (Wang et al., 2020). BHK-21 cells were used for the initial transfection with DNA plasmids for recovery of recombinant viruses and virus passages. PK-15 cells were used for plaque assays. The GETV isolate, GX201808 (GenBank no. MT269657), was isolated from the sera of pregnant sows exhibiting reproductive disorders in 2018 in Guangxi Province, China (Ren et al., 2020). Polyclonal antibodies against E2 (anti-GETV-E2 PcAb) were generated as described previously (Ren et al., 2020).

2.2. Construction of GETV full-length infectious cDNA clone

Viral RNA of plaque purified GX201808 was extracted using the Viral DNA/RNA Mini Prep kit (Axygen AXY) according to instructions provided by the manufacturer and this was used for synthesis of cDNA with random hexamers. Four fragments (S1, S2, S3 and S4) covering the whole genome of the virus were amplified by RT-PCR with PrimeSTAR®DNA Polymerase (Takara Bio, Inc., Dalian, China). The infectious cDNA clone was established using the four pairs of primers listed in Supplementary Table S1.

In order to introduce two additional enzyme digestion sites (PacI and MluI) into the pBR322 vector, a fragment was amplified by PCR using vector pBR322 as a template with primers PBR322PacI-381F and PBR332MluI-978R. The fragment was then digested with BamHI and NruI and ligated into similarly digested pBR322, resulting a modified pBR322-BM vector. The fragment containing a CMV promoter flanked with a PacI site at the 5′ end and two sites (XbaI and NruI) at the 3′ end were amplified by PCR with primers CMV-F and CMV-X-NR (Supplementary Table S1). The fragment containing bovine growth hormone polyadenylation signal (BGH) sequence and two enzymes digestion sites (MluI and NruI) was amplified by PCR with primers BGH-MluI-F and BGH-NruI-R.

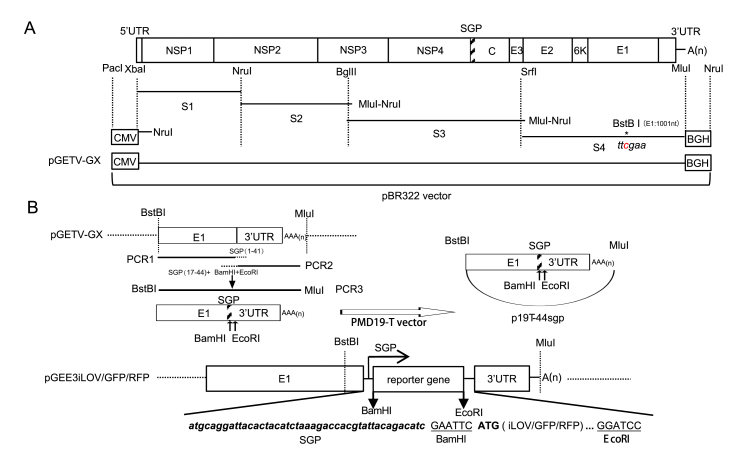

The procedure used for the construction of a full-length cDNA clone of GX201808 is shown in Fig. 1A. Briefly, the CMV fragment was digested with PacI and NruI and then ligated into a similarly digested pBR322-BM using T4 DNA ligase, generating a pBR322-CMV plasmid. Using the same strategy, the remaining PCR fragments were digested with the appropriate restriction enzymes (XbaI and NruI for S1, NruI for S2, BglII and MluI for S3, SrfI and MluI for S4 and MluI and NruI for BGH) and then ligated into a similarly digested recombinant plasmids obtained in the previous steps. The nucleotide at the 1001th position in the E1 gene was mutated from G to C by PCR with the designed primers TY-BstbI-TB-F and TY-MluI-R to create a restriction enzyme site (BstBI), which was subsequently used as a genetic marker to distinguish the cloned virus from the parental one. The CMV-launched infectious clone of GETV strain GX201808 produced was named pGETV-GX. The entire nucleotide sequence of the infectious clone pGETV-GX was determined in order to confirm its integrity by using primers as described in our previous study (Ren et al., 2020).

Fig. 1.

The diagram of recombinant plasmids construction. A Strategy for the construction of a full-length CMV-launched infectious clone based on the GETV isolate, GX201808. Four fragments covering the whole genome of GETV GX201808 strain were amplified and then were assembled successively into the pBR322 vector by using the unique restriction enzymes indicated for each fragment. A CMV promoter was placed at the 5′ end of the viral genome and BGH signal sequences were placed at the 3′ end of the genome. B Strategy for the construction of GETV full-length infectious reporter clones. The sub-genomic promoter (SGP) and the restriction enzyme sites (BamHI and EcoRI) were introduced between E1 protein and the 3′UTR of pGETV-GX. The reporter genes (GFP, RFP or iLOV) were amplified and then were assembled successively into the pBR322 vector by using unique restriction enzymes. The two introduced unique restriction enzyme sites, BamHI and EcoRI, are underlined. The introduction of SGP is indicated by bold italic text.

The construction strategy for reporter genes expression based on pGETV-GX is shown in Fig. 1B. To construct recombinant viruses expressing reporter genes, the sub-genomic promoter and the restriction enzyme sites (BamHI and EcoRI) were inserted to the region between E1 protein and the 3′UTR of pGETV-GX. Briefly, the fragment PCR1 was amplified by PCR using pGETV-GX as a template with primers TY-BstbI-F and 44 sgp 3′UTR-R. The fragment PCR2 was amplified by PCR using pGETV-GX as template with 44 sgp 3′UTR-F and TY-MluI-R. The second round of fusion PCR3 was performed using PCR1 and PCR2 fragments as the templates with primers TY-BstbI-F and TY-MluI-R. The resulting fusion PCR products containing a sub-genomic promoter and two restriction enzyme sites (BamHI and EcoRI) were cloned into a simple PMD19-T vector, creating a shuttle plasmid p19T-44sgp.

Different reporter genes (iLOV, GFP and RFP) were then cloned into the p19T-44sgp plasmid by using restriction enzyme sites BamHI and EcoRI, which generated shuttle plasmids p19T-44-iLOV, p19T-44-GFP and p19T-44-RFP, respectively. The expression cassettes within p19T-44-iLOV, p19T-44-GFP or p19T-44-RFP containing the sub-genomic promoter and reporter genes were released by BstBI and MluI and then cloned into the pGETV-GX vector, creating pGEE3iLOV, pGEE3GFP and pGEE3RFP recombinant plasmids.

2.3. DNA transfection and virus passage

The recombinant plasmids were purified with the Endo-free Plasmid Mini Kit II (Omega, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions. BHK-21 cells were transfected with 2 μg recombinant plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) according to instructions provided by the manufacturer. For virus rescue, 300 μL of the BHK-21 cell culture supernatants were harvested at 48 h post transfection (hpt) and served as the passage 0 (P0) of the rescued virus. The P0 virus was then inoculated into fresh BHK-21 cells. When 80% cytopathic effects (CPE) were observed, the supernatants were harvested from the cell cultures and designated as passage 1 (P1). Using the same protocol, 10 subsequent passages were produced and designated P1 to P10.

2.4. Indirect immunofluorescence assay

BHK-21 cell monolayers were used for assessing GETV E2 protein expression as described previously (Ren et al., 2020). BHK-21 cells were inoculated with either parental or rescued viruses at 0.1 multiplicity of infection (MOI). At 24 hpi, the infected cells were washed twice with PBS, followed by fixation in cold methanol, and then blocked with 1% BSA (bovine serum albumin fraction V; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) at room temperature. The BHK-21 cells were incubated with anti-GETV-E2 PcAb (1:100) at 37 °C for 2 h. After washing with PBS five times, the cells were treated with either goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488, green) or goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594, red) for 1 h at 37 °C and then washed five more times with PBS. The cell nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co. Ltd.). Finally, images were captured using an Olympus inverted fluorescence microscope equipped with a camera.

2.5. Plaque assay

Viral plaque assays were performed using PK-15 cells grown to 100% confluency in six-well plates as described previously (Ren et al., 2020). Briefly, serial 10-fold dilutions were made with mixtures of 100 μL of viral samples and 900 μL of EMEM. PK-15 cells were inoculated with 300 μL of each dilution. After 1 h inoculation, the cell monolayers were overlaid with a 3 mL mixture of EMEM, containing 2% FBS and 1% low melting agarose (Cambrex, Rockland, ME, USA). The cells were incubated for 2 days at 37 °C in 5% CO2. After careful removal of the media, the cells then were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 6 h, and then stained for 15 min with 3 mL of staining solution containing 25% formaldehyde and 0.5% crystal violet. Visible plaques were observed after washing the plates with tap water.

2.6. Multi-step growth curve

BHK-21 cell monolayers in 6-well plates were infected with the rescued (P3) and parental viruses (P3) at an MOI of 0.1. After 1 h incubation at 37 °C, the BHK-21 cells were washed three times with PBS and then cultured in DMEM containing 2% FBS (Gibco, USA). At 6, 12, 18, 24, 36 and 48 hpi, 300 μL of cell supernatants were collected. The virus titers at indicated time points were determined by calculating the TCID50 in BHK-21 cells using the Reed-Muench method. Each experiment was repeated independently three times and the SD was calculated.

2.7. Genetic stability of recombinant viruses

To test the stability of reporter genes in the recombinant viruses, these viruses were passaged serially in BHK-21 cells at an MOI of 0.1 from the first (P1) to the tenth passage (P10). The viral RNA samples obtained were extracted and then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the Viral DNA/RNA Mini Prep kit (Axygen AXY) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Genetic stability of exogenous reporter genes from the passaged recombinant viruses were verified by RT-PCR with the primers TY-BstbI-F and MluI-4R. The PCR products were subsequently cloned and sequenced.

2.8. Experimental infection of mice

The animal experiments were carried out in accordance with the guidelines issued by Animal Care & Welfare Committee of Guangxi University (GXU2019-043). Thirty three-day-old suckling Kunming mice (Charles River, Beijing) were randomly divided into three groups of ten. Two groups of mice were inoculated with 30 μL 106 PFU/mL of parental and cloned viruses by the intracerebral (IC) route, respectively. Mice in the control group were inoculated intra-cerebrally with 30 μL DMEM. The suckling mice were housed under optimal conditions. Each group of mice was observed daily from 0 dpi to 7 dpi for determination of morbidity (body weight and behavioral changes) and mortality (survival).

2.9. Viral detection, virus titration and histopathological examination

Brain tissues from mice were collected for viral detection, virus titration and histopathological examination. The brain samples were processed in PBS (0.1 g/300 μL, weight/volume). 200 μL of each sample was used for extraction of RNA using the Prep Body Fluid Viral DNA/RNA Mini Prep kit (Axygen AXY). RT-PCR was then performed to detect GETV using primers as described in a previous study (Li et al., 2017a). Virus titrations of brain tissues suspensions were performed by endpoint limiting dilution. Each sample was subjected to ten-fold serial dilutions in DMEM media containing 2% FBS and then these were inoculated into monolayers of BHK-21 cells cultured in 96-well plates. The virus titers were determined by calculating the TCID50 in BHK-21 cells using the Reed-Muench method. For histopathology examination, tissues of brain sections were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, rimmed, processed and embedded in paraffin. Then 4–6 μm sections were cut and fixed on microscope slides, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

2.10. Statistical analysis

The mean virus titers, survival rates and body weight of mice in each group infected with cloned and parental viruses were analyzed for significant differences between groups by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) (Statistical Analysis System; SAS 9.1 for windows; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). A P-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1. Construction of a full-length infectious cDNA clone of Getah virus

Four fragments covering the whole genome of the GETV strain, GX201808, were cloned into the pBR322 vector as described in the Methods and are shown in Fig. 1A. The full-length cDNA clone contains a CMV promoter at the 5′ end of the viral genome, the 11691 nt full-length genome of GETV GX201808, a 15 nt poly (A) tail at the 3′ end of the genome, followed by BGH signal sequences. The resulting infectious clone of the recombinant GETV GX201808 strain was named pGETV-GX. Sequence comparison between the DNA sequences of pGETV-GX (P1) and the full-length sequences of the parental GETV GX201808 strain showed seven nucleotide differences (Table 1). A nucleotide G at position 10972 in the E1 gene was mutated artificially into a C to create a BstBI restriction enzyme site that could be used as a genetic marker. There were also a T3735 to C3735 mutation in the NSP2 gene, C6827 to T6827 and G7120 to A7120 mutations in the NSP4 gene, a C8406 changed to T8406 in the E3 gene as well as G10777 to A10777 and G10780 to A10780 mutations in the E1 gene. The changes of the amino acids caused by these nt mutations are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the nucleotide and amino acid differences between the infectious cDNA clone, pGETV-GX (P1), and the parental virus GX201808

| Nucleotide position within the GETV genome | GX201808 | pGETV-GX | Amino acid change | Gene position |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3735 | T | C | I→I | NSP2 |

| 6827 | C | T | P→L | NSP4 |

| 7120 | G | A | E→K | NSP4 |

| 8406 | C | T | H→Y | E3 |

| 10777 | G | A | G→E | E1 |

| 10780 | G | A | S→N | E1 |

| 10972 | G | C | W→S | E1 |

3.2. Generation and characterization of recombinant virus derived from the Getah virus full-length cDNA clone

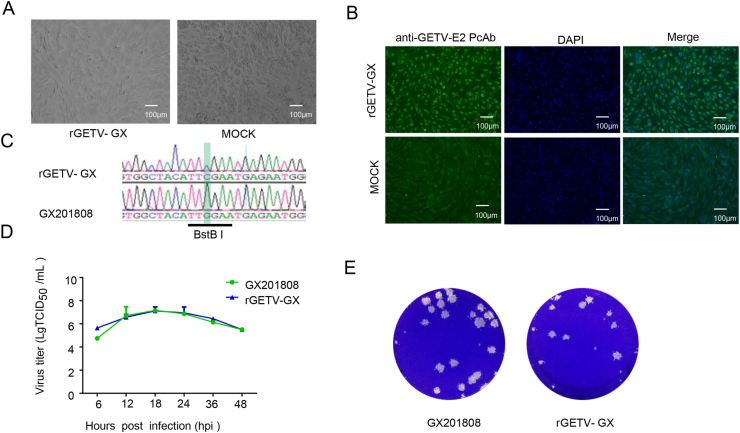

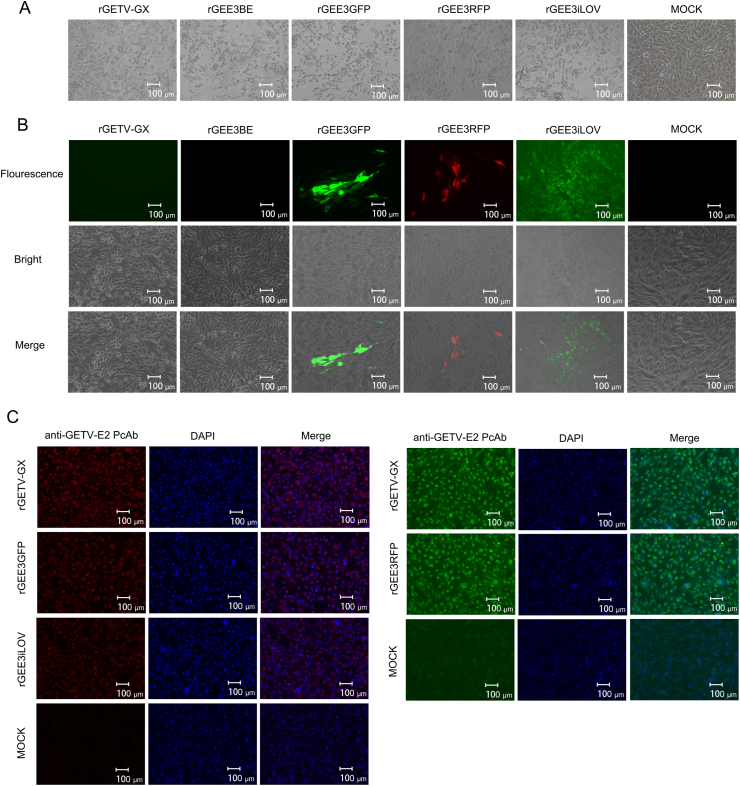

The full-length infectious cDNA clone, pGETV-GX, was directly used for DNA plasmid transfection into BHK-21 cells. The supernatants of the transfected cells were harvested at 48 hpt and served as the passage 0 (P0) virus which was then used to inoculate fresh BHK-21 cells for serial passages. Typical CPE were observed in BHK-21 cells at 24 hpi (Fig. 2A). IFA was performed to detect the expression of E2 protein in the rescued virus. As shown in Fig. 2B, there was positive intracellular expression of E2 protein in the rGETV-GX-infected cells but not in mock-infected BHK-21 cells. To exclude the possibility that the recovered virus was due to contamination by the parental virus, the introduced genetic marker in E1 of the cloned virus (P3) was amplified and sequenced. The results showed the genetic marker at position 10972 nucleotide in the E1 gene of the cloned virus was retained (Fig. 2C), confirming that the cloned virus is capable of replication. The growth kinetics of the cloned (P3) and parental viruses were compared. BHK-21 cells were infected with each of the virus types at an MOI of 0.1 and harvested at 6, 12, 18, 24, 36 and 48 hpi. The results showed that the cloned virus possessed growth kinetics similar to that of the parental virus, as shown in Fig. 2D. Plaque morphology of these viruses was further determined. As shown in Fig. 2E, the plaque size produced by the cloned virus was slightly smaller than that of the parental virus. These results indicate that the cloned virus possesses in vitro growth properties similar to those of the parental virus.

Fig. 2.

Recovery and characterization of recombinant virus derived from the Getah virus full-length cDNA clone. A Cytopathic effects in BHK-21 cells infected with the cloned virus rGETV-GX for 36 hpi. B IFA analysis of the E2 protein expression in BHK-21 cells. BHK-21 cells infected with rGETV-GX were fixed and stained using an anti-GETV-E2 PcAb and goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488, green). Scale bar = 100 μm. C Identification of the genetic marker in the rescued virus. The PCR fragment containing the genetic marker, BstBI, was amplified using RT-PCR from RNA extracted from the recombinant virus. The PCR products were then sequenced. The BstBI restriction site sequence is underlined. D Growth curves of the cloned and parental viruses. BHK-21 cells were infected with recovered or parental viruses at an MOI of 0.1. The viral titers were determined as TCID50 and the values obtained were the means of three independent experiments. E Plaque morphology of GETV GX201808 and cloned viruses. Monolayers of PK-15 cells in six-well plates were infected with cloned or parental viruses. The cell monolayers were overlaid with 1% agarose and stained with crystal violet at 48 hpi.

In order to determine the genetic stability of the genomes of the cloned viruses, these were serially passaged five times (P1 through P5) in BHK-21 cells. The full-length genome of P5 recovered virus was sequenced. Sequence comparison between pGETV-GX and the P5 recovered virus showed 3 nucleotide differences. There was a G3469 to A3469 mutation in the NSP2 gene. In addition, G10637 to A10637 and C11039 to T11039 mutations were found in the E1 gene. The changes of the resultant amino acids caused by these nucleotide mutations are shown in Supplementary Table S2.

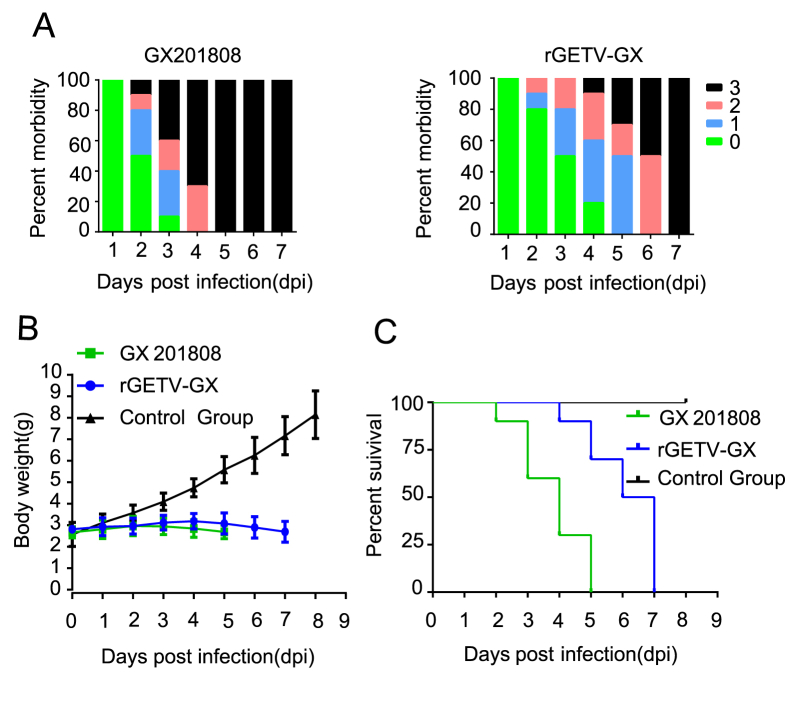

3.3. Pathogenicity of the parental and cloned Getah viruses in mice

Thirty three-day-old suckling mice were randomly divided into three groups and infected with either parental GX201808 virus (n = 10; group 1), cloned rGETV-GX virus (n = 10; group 2) or DMEM as a negative control (n = 10; group 3). All mice in groups 1 and 2 developed clinical symptoms, including respiratory distress, lethargy, diarrhea, hind limb weakness and difficulties in movement (Fig. 3A). Slow weight gain followed by weight loss was also observed in these mice (Fig. 3B). None of the mice in group 3 inoculated with DMEM showed any clinical symptoms or weight loss. Suckling mice in the parental virus group started to die at 2 dpi and all the mice died by 5 dpi. Suckling mice in the cloned virus group started to die at 4 dpi and all the mice died by 7 dpi (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Pathogenicity of the parental and cloned Getah viruses in mice. Two groups of mice (n = 10 in each group) were inoculated intracerebrally with 30 μL 106 PFU/mL of parental and cloned viruses, respectively. Mice in the control group were inoculated intracerebrally with 30 μL DMEM. A The morbidity of the parental and cloned Getah viruses infected mice (Clinical Score: 0-healthy, 1-Depression, lethargy, respiratory distress, 2-limb paralysis and diarrhea, 3-Moribund or death). B Comparison of the average body weights among different groups of mice. C Survival curves of 3-day old mice after inoculation of the parental or rescued viruses. All ten mice in the control group remained alive and in healthy condition.

Total RNA from the brain samples of mice infected with both parental and recombinant viruses were determined by RT-PCR. As shown in Fig. 4A, the expected bands were detected in all mice from Groups 1 and 2. The infectious GETV particles in the brain samples of all the mice were quantified by TCID50. As showed in Fig. 4B, the infectious viruses were detected in parental GX201808 virus (group 1) infected and rGETV-GX (group 2) infected mice brains. The levels of viral titer in the brains of mice from group 1 (average level, 8.21 × 104 TCID50/0.1 g) was slightly higher than those from group 2 (6.88 × 104 TCID50/0.1 g). But the difference between the two groups was not significant (P > 0.05). A pathological examination of brain samples was carried out in mice from Groups 1 and 2, as well as in the control group. Histopathological results showed that cerebellar nerve cells of mice in group 1 and 2 were observed varying degrees of degeneration or necrosis, uneven or dense cytoplasmic, nucleus condense or dissolution, and sparse or vacuolar degeneration of nerve fibers (Fig. 4C). But these histopathological changes were not observed in the control group (Fig. 4C). These results indicated that both parental and cloned viruses could infect and replicate in mice, while cloned virus displayed a milder form of pathogenicity compared to the parental virus in this mouse model.

Fig. 4.

Detection of parent and cloned Getah viruses in mice. A Agarose gel pictures showing the specific DNA fragment generated by RT-PCR using the RNA extracted from brain tissues of mice infected with parental and cloned viruses. M, DNA ladder. Numbers 1 to 10 represent brain tissues of different mice. B Infectious virus titers were quantified by a TCID50 assay. Parental virus and cloned viruses were extracted from brain samples of mice. C Histopathological analysis (hematoxylin and eosin staining) of brain tissues from mice infected with parental virus and cloned viruses, as well as control group. Scale bar = 100 μm.

3.4. The Getah virus infectious clone as a vector for expressing reporter genes

BamHI and EcoRI sites were inserted between E1 and 3′UTR of the infectious clone, pGETV-GX, in order to be able to insert heterogenous genes conveniently into the genome. A synthetic SGP sequence was inserted immediately before the BamHI site for the transcription of the introduced foreign genes. The resulting clone was designated pGEE3BE (Fig. 1B). Subsequently, different reporter genes (iLOV, GFP and RFP) were inserted into the pGEE3BE plasmid by using the introduced BamHI and EcoRI sites, creating recombinant plasmids pGEE3GFP, pGEE3RFP and pGEE3iLOV. BHK-21 cells were then transfected with the recombinant plasmids. After the supernatants collected from transfected cells were inoculated into fresh BHK-21 cells, CPE were observed at 24 hpi as shown in Fig. 5A. The live GFP, RFP and iLOV-expressing cells were visible in cells inoculated with rGEE3GFP, rGEE3RFP and rGEE3iLOV, but not in rGETV-GX, rGEE3BE and mock-infected BHK-21 cells (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Recovery and expression of GETV with insertion of a reporter gene in E1 and 3′UTR. A Cytopathic effects in BHK-21 cells infected with the reporter viruses and recombinant virus, rGETV-GX. B Expression of reporter auto-fluorescence. BHK-21 cells were seeded in six-well plates and infected with reporter viruses. At 18 hpi, live cells were imaged with a fluorescence microscope. C IFA of BHK-21 cells infected with the reporter viruses and cloned virus, rGETV-GX. The IFA analysis was performed at 24 h after infection using an anti-GETV-E2 PcAb as primary antibody and goat anti-rabbit H&L IgG as secondary antibody. To avoid fluorescence interference, IFA analysis of rGEE3iLOV and rGEE3GFP used goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 594, red) as secondary antibody. IFA analysis of rGEE3RFP used goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (Alexa Fluor® 488, green) as secondary antibody. rGETV-GX used two secondary antibodies as controls. Scale bar = 100 μm.

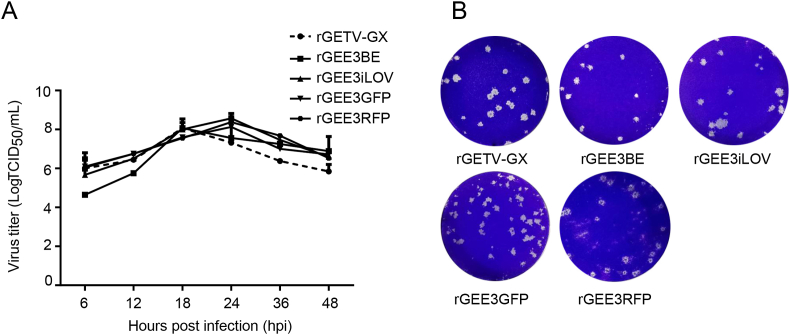

In order to confirm the expression of E2 proteins, cells infected with recombinant viruses were incubated with anti-GETV-E2 PcAb and then stained with green or red secondary antibodies of goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L. As shown in Fig. 5C, the E2 proteins could be detected in BHK-21 cells infected by rGETV-GX, rGEE3BE, rGEE3GFP, rGEE3RFP and rGEE3iLOV but not in mock-infected BHK-21 cells. To determine the replication characteristics of reporter viruses, multi-step growth kinetics and plaques of the recombinant viruses were analyzed. The multiple-step growth curves displayed similarities of the growth behavior between the cloned and parental virus. However, the time points for appearance of the peak titers of the reporter viruses delayed compared to the parental virus (Fig. 6A). The recombinant viruses showed plaque phenotypes which were similar to those of the parental virus in PK-15 cells (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Growth kinetics and plaque morphology of recombinant GETVs with insertion of a reporter gene in E1 and 3′UTR. A Multi-step growth kinetics of reporter viruses in BHK-21 cells. Cells in six-well plates were infected with reporter viruses or cloned virus, rGETV-GX, at an MOI of 0.1, and the virus titers of the culture supernatants collected at the indicated time points after infection were determined by TCID50. Average titers with standard deviations (error bars) from three independent experiments are shown. B Comparison of viral plaque morphology among different recombinant viruses. BHK-21 cells in six-well plates were infected with ten-fold serially diluted recombinant viruses, cultured in EMEM containing 1% agarose overlay, fixed at 2 d.p.i., and stained with 1% crystal violet.

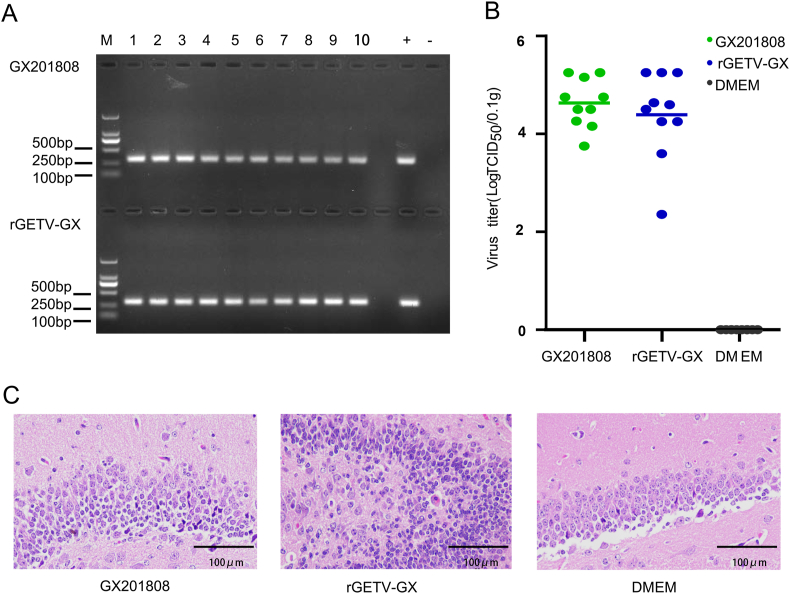

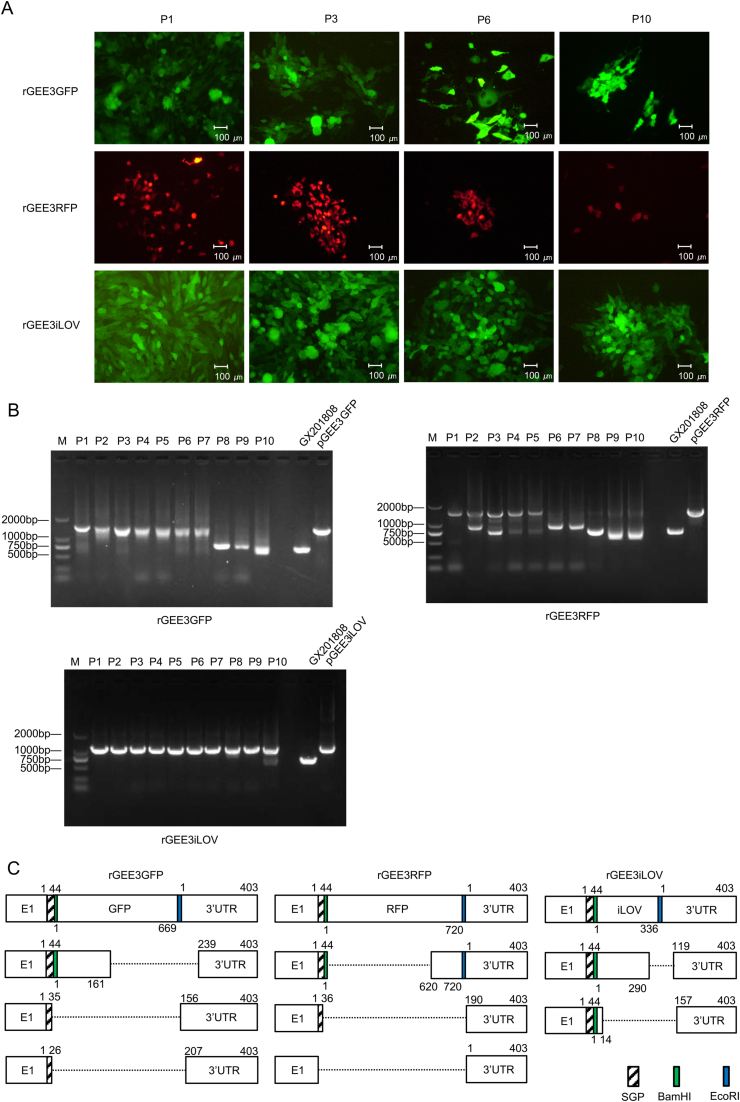

3.5. The reporter GETVs are genetically unstable

In order to determine the genetic stability of reporter genes in the genomes of the recombinant viruses, the viruses were serially passaged ten times (P1 through P10) in BHK-21 cells. The P1, P3, P6 and P10 of each reporter virus was used to infect BHK-21 cells, and live cells were imaged at 24 hpi to evaluate the expression of reporter proteins. As shown in Fig. 7A, green fluorescence was detected in most of the BHK-21 cells inoculated with P1, P3 and P6 rGEE3GFP reporter virus. And the number of cells showing green fluorescence markedly decreased in BHK-21 cells cultures infected with P10 rGEE3GFP virus. Similarly, red fluorescence was also detected in the BHK-21 cells infected with P1, P3 and P6 rGEE3RFP reporter virus but decreased dramatically with P10 virus.

Fig. 7.

The reporter GETVs are genetically unstable. A Analysis of the stability of reporter genes in the genomes of recombinant viruses in cells. Expression of reporter auto-fluorescence during serial passages of reporter viruses. BHK-21 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and infected with P1, P3, P6 and P10 viruses. At 24 hpi, live cells were imaged with a fluorescence microscope. B Agarose gel pictures showing the DNA fragment covering the reporter gene insertion region as generated by RT-PCR using the RNA extracted from cells infected with P1–P10 reporter viruses. C Diagram of nucleotide deletions detected in the genomes of passaged reporter viruses. Internal deletions found in the genomes of rGEE3GFP, rGEE3RFP and rGEE3iLOV after these viruses were passaged in cells. The E1, reporter genes and 3′UTR sequences are indicated by white boxes. The introduced SGP, BamHI restriction site and EcoRI restriction site are indicated by the black, green and blue boxes, respectively. The numbers above the boxes indicate the nucleotide boundaries of the inserts, 3′UTR and internal deletions. The deleted regions are indicated by the dotted lines.

All of the BHK-21 cells infected by P1, P3, P6 and P10 rGEE3iLOV reporter virus showed strong green fluorescence signals. To further confirm the stability of these reporter viruses, the genomic region containing the reporter gene insertions of P1–P10 reporter viruses and the parental virus were amplified by RT-PCR and then sequenced. As shown in Fig. 7B, an expected 0.72 kb band was detected from the RT-PCR products of GX201808 parental virus. A 1.49 kb PCR product was obtained using P1–P7 rGEE3GFP virus or pGEE3GFP plasmid as a template and a small DNA fragment of 0.72 kb was obtained for the P8–P10 rGEE3GFP virus. A smaller PCR product of 0.72 kb became apparent and gradually stabilized in addition to the 1.55-kb DNA fragment when using the P1–P10 RT-PCR products of rGEE3RFP virus as templates. Each of the P1–P9 rGEE3iLOV RNAs extracted from BHK-21 cells displayed a specific band of 1.16 kb. In addition to this band, a small DNA fragment of 0.72 kb was obtained using P10 rGEE3iLOV RT-PCR products as the template. These results indicate that the reporter viruses are not stable during passaging in BHK-21 cells.

The smaller sized PCR products generated from the passaged reporter viruses (rGEE3GFP, rGEE3RFP and rGEE3iLOV) were cloned into a pMD18-T vector and then sequenced. The sequences of the smaller sized PCR products were aligned to the respective parental reporter virus sequence. The results showed that the three different rGEE3GFP, rGEE3RFP and rGEE3iLOV reporter viruses produced nucleotides deletions of different lengths. The reporter virus genomes contained different patterns of nucleotide deletions that included not only the entire reporter genes, but also the introduced SGP and restriction sites and up to 238 nucleotides in the 3′UTR region (Fig. 7C).

4. Discussion

In the present study, we successfully developed a reverse genetic system for the GETV strain, GX201808. The established CMV-driven cDNA clone (pGETV-GX) was both replication competent and infectious. The full-length infectious cDNA system for GETV is under the control of a CMV promoter. Viral genomic RNA transcripts could be produced after transfection of the full-length GETV DNA plasmid into permissive cells. BGH added at the end of GETV genome can maintain the integrity of the 3′ terminal of GETV genome. It increases the rescue efficiency of the GETV infectious clone and also reduces labor and experimental costs of the process (Aubry et al., 2015; Perrotta and Been, 1991). Compared with parental virus, the GETV cDNA clone contains 7 nucleotide mutations located in NSP2, NSP4, E3 and E1 genes, which resulted in six amino acids changes to the protein sequence. These mutations may have been introduced during the process of the amplification and cloning of GETV RNA genome or due to the appearance of RNA quasispecies of the parental virus.

In infected cells, the growth kinetics of the cloned rGETV-GX virus was found to be similar to parental virus. Mice infected with either cloned or parental viruses showed similar clinical symptoms, mortality, and histopathologic features in brain samples. However, the time of death for mice in the cloned virus group was delayed compared to the parental virus group. Previous studies have shown that mutations in key sites can indeed affect the replication ability and virulence of alphaviruses (Davis et al., 1986, 1991; Ferguson et al., 2015; Kinney et al., 1993). Whether the in vivo pathological differences were caused by the 6 nt mutations in the cloned virus genome needs further study.

Reverse genetic systems are valuable tools to study the various aspects of the virus life cycle and can also be developed as vectors in order to express heterogenous genes. Several strategies have been adopted to express exogenous genes in alphaviruses (Sun et al., 2014). The most common strategy is the double-sub-genomic promoter (DSP) design (Caley et al., 1999; Pugachev et al., 1995). In this strategy, a novel sub-genomic promoter is inserted either between E1 protein and 3′UTR or immediately after the nonstructural proteins in the genome sequence. The foreign gene of interest would be placed under the control of the introduced sub-genomic promoter, allowing the synthesis of sub-genomic (sg) mRNA for expression of the foreign protein. In this study, we placed an additional sub-genomic promoter and different reporter genes (GFP, RFP and iLOV) in the region between the E1 protein and 3′UTR of GETV genome based on the established GETV infectious clone. The GFP, RFP and iLOV-tagged GETV were found to be both replicative competent and infectious. The insertion of the reporter gene impaired viral replication in cells slightly, which may lead to the delayed appearance of the peak virus titers.

The stability of foreign gene expression in DSP-based expression vectors should be monitored carefully, as stable expression of these genes is important during cell culture and vaccine applications. In this study, the reporter genes in the GETV genome were found to be genetically unstable after successive passages in cultured cells. The number of cells showing green and red fluorescence decreased markedly in BHK-21 cell cultures infected with either P10 rGEE3GFP or P10 rGEE3RFP virus. However, all of the BHK-21 cells infected with P10 rGEE3iLOV reporter virus which carried a smaller size of reporter gene (iLOV; 336 nucleotides) showed strong green fluorescence signals. The reason for this may be that the length and structure of the different reporter genes within alphaviruses produce different expression levels of the different reporter genes (Thomas et al., 2003).

Mutants with deletions in the reporter genes emerged in all three reporter viruses. Recombinant viruses expressing the RFP gene were more likely to produce deletion mutants in this gene compared to the reporter genes. Deletions in the RFP gene were detected in the P1–P10 RFP reporter virus RNA samples. Nucleotide deletions in the GFP gene in GFP reporter virus occurred at P1 and became dominant by P8–P10. GETV mutants with deletions in the iLOV genes emerged at P10. In a previous study, firefly luciferase (fLuc; 1650 nucleotides) and nanoLuc (nLuc; 513 nucleotides) were inserted between the E1 protein and 3′UTR of four different alphaviruses. The results showed that nLuc expression was substantially more stable than fLuc expression during repeated rounds of infection in vitro regardless of the type of virus used (Sun et al., 2014). The phenomenon of instability for double sub-genomic viruses has also been described in several alphaviruses species (Brault et al., 2004; Higgs et al., 1995, 1999; Pierro et al., 2003; Pugachev et al., 1995; Vanlandingham et al., 2005). The duplicated 26S promoter involving recombination events may account for instability of some DSP-based alphavirus vectors (Pugachev et al., 2000).

The reporter virus genomes contained different patterns of nucleotide deletions, including partial or entire nucleotides deletions of the reporter genes as well as the introduced SGP and restriction sites. Interestingly, a large fragment deletion of up to 238 nucleotides was detected in genomes of the 3′UTR of passaged reporter viruses. Numerous studies have shown that natural or engineered nucleotide deletions in the 3′UTR of several alphaviruses may contribute to the adaptive potential and transmission by mosquito vectors (Chen et al., 2013; Filomatori et al., 2021; Garcia-Moreno et al., 2016; Hawman et al., 2017; Hyde et al., 2015; Kuhn et al., 1990). The biological properties of nucleotide deletions in 3′UTR of passaged reporter viruses need to be further studied. Although these reporter genes exhibit instability during multiple passages in cell culture, VP7 protein of bluetongue virus inserted at the same position in the Sindbis virus could induce a similar level of VP7-specifific antibodies in vaccinated mice, compared with fusion into structural proteins which have higher expression stability. Similar results were also displayed by another study in Sindbis virus (Pugachev et al., 1995). It shows stabilities of exogenous genes might not be able to influence the immune responses to the expressed proteins in vivo (Thomas et al., 2003). Therefore, it appears that the stability of the recombinant viruses is not necessarily a critical factor for the induction of immunity in cell culture.

5. Conclusions

We successfully developed a reverse genetic system for an emerging GETV and determined the growth and pathogenic properties of the parental and cloned viruses. Furthermore, we inserted three reporter genes between the E1 protein and the 3′UTR in the genome of GETV based on the established infectious cDNA clone. We believe that the establishment of a reverse genetic system for GETV will provide a useful tool for further study of this virus as well as to aid the development of a new alphavirus vector.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The animal experiments were approved by the Animal Experiment Committee of Guangxi University with the approval number (GXU2019-043).

Author contributions

Zuzhang Wei: conceptualization, project administration, and writing (review and editing). Tongwei Ren: investigation, data curation, methodology and writing-original draft. Xiangling Min: data curation and methodology. Qingrong Mo: data curation and methodology. Yuxu Wang: formal analysis. Hao Wang: formal analysis. Kang Ouyang: formal analysis and investigation. Ying Chen: formal analysis and supervision. Weijian Huang: investigation, formal analysis and validation.

Conflict of interest

The research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships. The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi Province (No. 2018GXNSFDA281021) and the Foundation of Guangxi University (No. XGZ130959). We are grateful to Dr. Dev Sooranna of Imperial College London for English language edits of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.virs.2022.03.007.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Anishchenko M., Paessler S., Greene I.P., Aguilar P.V., Carrara A.S., Weaver S.C. Generation and characterization of closely related epizootic and enzootic infectious cDNA clones for studying interferon sensitivity and emergence mechanisms of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus. J. Virol. 2004;78:1–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.1.1-8.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubry F., Nougairède A., Gould E.A., de Lamballerie X. Flavivirus reverse genetic systems, construction techniques and applications: a historical perspective. Antivir. Res. 2015;114:67–85. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannai H., Ochi A., Nemoto M., Tsujimura K., Yamanaka T., Kondo T. A 2015 outbreak of Getah virus infection occurring among Japanese racehorses sequentially to an outbreak in 2014 at the same site. BMC Vet. Res. 2016;12:98. doi: 10.1186/s12917-016-0741-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault A.C., Foy B.D., Myles K.M., Kelly C.L.H., Higgs S., Weaver S.C., Olson K.E., Miller B.R., Powers A.M. Infection patterns of o'nyong nyong virus in the malaria-transmitting mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol. Biol. 2004;13:625–635. doi: 10.1111/j.0962-1075.2004.00521.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C.M., Timoney P.J. Getah virus infection of Indian horses. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 1998;30:241–252. doi: 10.1023/a:1005079229232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant J.E., Crabtree M.B., Nam V.S., Yen N.T., Duc H.M., Miller B.R. Isolation of arboviruses from mosquitoes collected in northern Vietnam. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2005;73:470–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caley I.J., Betts M.R., Davis N.L., Swanstrom R., Johnston R.E.J.V. Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus vectors expressing HIV-1 proteins: vector design strategies for improved vaccine efficacy. Vol. 17. 1999. p. 3124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.Y., Huang C.C., Huang T.S., Deng M.C., Jong M.H., Wang F.I. Journal of Veterinary Diagnostic Investigation: Official Publication of the American Association of Veterinary Laboratory Diagnosticians, Inc. vol. 18. 2006. Isolation and characterization of a Sagiyama virus from domestic pigs; pp. 156–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R., Wang E., Tsetsarkin K.A., Weaver S.C. Chikungunya virus 3' untranslated region: adaptation to mosquitoes and a population bottleneck as major evolutionary forces. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis N.L., Fuller F.J., Dougherty W.G., Olmsted R.A., Johnston R.E.J.P. A single nucleotide change in the E2 glycoprotein gene of Sindbis virus affects penetration rate in cell culture and virulence in neonatal mice. Vol. 83. 1986. pp. 6771–6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis N.L., Powell N., Greenwald G.F., Willis L.V., Johnson B.J., Smith J.F., Johnston R.E.J.V. Attenuating mutations in the E2 glycoprotein gene of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus: construction of single and multiple mutants in a full-length cDNA clone. Vol. 183. 1991. p. 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis N.L., Willis L.V., Smith J.F., Johnston R.E. In vitro synthesis of infectious venezuelan equine encephalitis virus RNA from a cDNA clone: analysis of a viable deletion mutant. Virology. 1989;171:189–204. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M.C., Saul S., Fragkoudis R., Weisheit S., Cox J., Patabendige A., Sherwood K., Watson M., Merits A., Fazakerley J.K.J. Ability of the encephalitic arbovirus Semliki forest virus to cross the blood-brain barrier is determined by the charge of the E2 glycoprotein. Vol. 89. 2015. pp. 7536–7549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filomatori C.V., Merwaiss F., Bardossy E.S., Alvarez D.E. Impact of alphavirus 3'UTR plasticity on mosquito transmission. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021;111:148–155. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga Y., Kumanomido T., Kamada M. Getah virus as an equine pathogen. Vet Clin N Am-Equine. 2000;16:605–617. doi: 10.1016/s0749-0739(17)30099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Moreno M., Sanz M.A., Carrasco L.J.S.R. A viral mRNA motif at the 3′-untranslated region that confers translatability in a cell-specific manner. Implications for Virus Evolution. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19217. doi: 10.1038/srep19217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould E.A., Coutard B., Malet H., Morin B., Jamal S., Weaver S., Gorbalenya A., Moureau G., Baronti C., Delogu I., Forrester N., Khasnatinov M., Gritsun T., de Lamballerie X., Canard B. Understanding the alphaviruses: recent research on important emerging pathogens and progress towards their control. Antivir. Res. 2010;87:111–124. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawman D.W., Carpentier K.S., Fox J.M., May N.A., Sanders W., Montgomery S.A., Moorman N.J., Diamond M.S., Morrison T.E. Mutations in the E2 glycoprotein and the 3’ untranslated region enhance chikungunya virus virulence in mice. J. Virol. 2017;91:e00816–17. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00816-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S., Olson K.E., Klimowski L., Powers A.M., Carlson J.O., Possee R.D., Beaty B.J. Mosquito sensitivity to a scorpion neurotoxin expressed using an infectious Sindbis virus vector. Insect Mol. Biol. 1995;4:97–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.1995.tb00013.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgs S.S., Oray C., Myles K.K., Olson K., Beaty B.J.B. Infecting larval arthropods with a chimeric, double subgenomic Sindbis virus vector to express genes of interest. Vol. 27. 1999. pp. 908–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyde J.L., Chen R., Trobaugh D.W., Diamond M.S., Weaver S.C., Klimstra W.B., Wilusz J.J.V.R. The 5′ and 3′ ends of alphavirus RNAs. Non-coding is not non-functional. 2015;206:99–107. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada M., Ando Y., Fukunaga Y., Kumanomido T., Imagawa H., Wada R., Akiyama Y. Equine Getah virus infection: isolation of the virus from racehorses during an enzootic in Japan. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1980;29:984–988. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1980.29.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinney R.M., Chang G.J., Tsuchiya K.R., Sneider J.M., Trent D.W.J.J. Attenuation of Venezuelan equine encephalitis virus strain TC-83 is encoded by the 5'-noncoding region and the E2 envelope glycoprotein. Vol. 67. 1993. p. 1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ksiazek T.G., Trosper J.H., Cross J.H., Basaca-Sevilla V. Isolation of Getah virus from nueva ecija province, republic of the Philippines. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1981;75:312–313. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(81)90346-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R.J., Hong Z., Strauss J.H.J.J. Mutagenesis of the 3' nontranslated region of Sindbis virus. RNA. 1990;64:1465–1476. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.4.1465-1476.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn R.J., Niesters H.G., Hong Z., Strauss J.H. Infectious RNA transcripts from Ross River virus cDNA clones and the construction and characterization of defined chimeras with Sindbis virus. Virology. 1991;182:430–441. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(91)90584-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumanomido T., Wada R., Kanemaru T., Kamada M., Hirasawa K., Akiyama Y. Clinical and virological observations on swine experimentally infected with Getah virus. Vet. Microbiol. 1988;16:295–301. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(88)90033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.D., Qiu F.X., Yang H., Rao Y.N., Calisher C.H. Isolation of Getah virus from mosquitos collected on Hainan Island, China, and results of a serosurvey. Southeast Asian J. Trop. Med. Publ. Health. 1992;23:730–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Fu S., Guo X., Li X., Li M., Wang L., Gao X., Lei W., Cao L., Lu Z., He Y., Wang H., Zhou H., Liang G. Serological survey of Getah virus in domestic animals in yunnan province, China. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2019;19:59–61. doi: 10.1089/vbz.2018.2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.Y., Fu S.H., Guo X.F., Lei W.W., Li X.L., Song J.D., Cao L., Gao X.Y., Lyu Z., He Y., Wang H.Y., Ren X.J., Zhou H.N., Wang G.Q., Liang G.D. Identification of a newly isolated Getah virus in the China-Laos border, China. Biomed. Environ. Sci. : BES. 2017;30:210–214. doi: 10.3967/bes2017.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.Y., Liu H., Fu S.H., Li X.L., Guo X.F., Li M.H., Feng Y., Chen W.X., Wang L.H., Lei W.W., Gao X.Y., Lv Z., He Y., Wang H.Y., Zhou H.N., Wang G.Q., Liang G.D. From discovery to spread: the evolution and phylogeny of Getah virus. Infect. Genet. Evol. : J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evolut. Genet. Infect. disea. 2017;55:48–55. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2017.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liljestrom P., Lusa S., Huylebroeck D., Garoff H. In vitro mutagenesis of a full-length cDNA clone of Semliki Forest virus: the small 6,000-molecular-weight membrane protein modulates virus release. J. Virol. 1991;65:4107–4113. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.8.4107-4113.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Zhang X., Li L.X., Shi N., Sun X.T., Liu Q., Jin N.Y., Si X.K. First isolation and characterization of Getah virus from cattle in northeastern China. BMC Vet. Res. 2019;15:320. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-2061-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G., Ou J., Ji J., Ren Z., Hu X., Wang C., Li S. Emergence of Getah virus infection in horse with fever in China, 2018. Front. Microbiol. 2019;10:1416. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKnight K.L., Simpson D.A., Lin S.C., Knott T.A., Polo J.M., Pence D.F., Johannsen D.B., Heidner H.W., Davis N.L., Johnston R.E. Deduced consensus sequence of Sindbis virus strain AR339: mutations contained in laboratory strains which affect cell culture and in vivo phenotypes. J. Virol. 1996;70:1981–1989. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1981-1989.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemoto M., Bannai H., Tsujimura K., Kobayashi M., Kikuchi T., Yamanaka T., Kondo T. Getah virus infection among racehorses, Japan, 2014. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21:883–885. doi: 10.3201/eid2105.141975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrotta A.T., Been M.D. A pseudoknot-like structure required for efficient self-cleavage of hepatitis delta virus RNA. Nature. 1991;350:434–436. doi: 10.1038/350434a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer M., Kinney R.M., Kaaden O.R. The alphavirus 3'-nontranslated region: size heterogeneity and arrangement of repeated sequence elements. Virology. 1998;240:100–108. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierro D.J., Myles K.M., Foy B.D., Beaty B.J., Olson K.E. Development of an orally infectious Sindbis virus transducing system that efficiently disseminates and expresses green fluorescent protein in Aedes aegypti. Insect Mol. Biol. 2003;12:107–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2003.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porterfield J.S. The basis of arbovirus classification. Med. Biol. 1975;53:400–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugachev K.V., Mason P.W., Shope R.E., Frey T.K.J.V. Double-subgenomic Sindbis virus recombinants expressing immunogenic proteins of Japanese encephalitis virus induce significant protection in mice against. Lethal JEV Infect. 1995;212:587–594. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugachev K.V., Tzeng W.P., Frey T.K.J.J. Development of a rubella virus vaccine expression vector: use of a picornavirus internal ribosome entry site increases stability of expression. Vol. 74. 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren T., Mo Q., Wang Y., Wang H., Nong Z., Wang J., Niu C., Liu C., Chen Y., Ouyang K., Huang W., Wei Z. Emergence and phylogenetic analysis of a Getah virus isolated in southern China. Front. Veterin. Sci. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fvets.2020.552517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice C.M., Levis R., Strauss J.H., Huang H.V. Production of infectious RNA transcripts from Sindbis virus cDNA clones: mapping of lethal mutations, rescue of a temperature-sensitive marker, and in vitro mutagenesis to generate defined mutants. J. Virol. 1987;61:3809–3819. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.12.3809-3819.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoepp R.J., Smith J.F., Parker M.D. Recombinant chimeric western and eastern equine encephalitis viruses as potential vaccine candidates. Virology. 2002;302:299–309. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sentsui H., Kono Y. Reappearance of Getah virus infection among horses in Japan. Nihon juigaku zasshi. Jpn. J. Vet. Sci. 1985;47:333–335. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.47.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi N., Li L.X., Lu R.G., Yan X.J., Liu H. Highly pathogenic swine Getah virus in blue foxes, eastern China, 2017. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2019;25:1252–1254. doi: 10.3201/eid2506.181983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata I., Hatano Y., Nishimura M., Suzuki G., Inaba Y. Isolation of Getah virus from dead fetuses extracted from a naturally infected sow in Japan. Vet. Microbiol. 1991;27:385–391. doi: 10.1016/0378-1135(91)90162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson D.A., Davis N.L., Lin S.C., Russell D., Johnston R.E. Complete nucleotide sequence and full-length cDNA clone of S.A.AR86 a South African alphavirus related to Sindbis. Virology. 1996;222:464–469. doi: 10.1006/viro.1996.0445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama I., Shimizu E., Nogami S., Suzuki K., Miura Y., Sentsui H. Serological survey of arthropod-borne viruses among wild boars in Japan. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 2009;71:1059–1061. doi: 10.1292/jvms.71.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Gardner C.L., Watson A.M., Ryman K.D., Klimstra W.B.J.J. Stable, high-level expression of reporter proteins from improved alphavirus expression vectors to track replication and dissemination during encephalitic and arthritogenic disease. Vol. 88. 2014. pp. 2035–2046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas J.M., Klimstra W.B., Ryman K.D., Heidner H.W.J.J. Sindbis virus vectors designed to express a foreign protein as a cleavable component of the. Viral Struct. Polypr. 2003;77:5598–5606. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.10.5598-5606.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanlandingham D.L., Tsetsarkin K., Hong C., Klingler K., Mcelroy K.L., Lehane M.J., Higgs S.J.I.B., Biology M. Development and characterization of a double subgenomic chikungunya virus infectious clone to express heterologous genes in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Vol. 35. 2005. pp. 1162–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.Y., Dominguez G., Frey T.K. Construction of rubella virus genome-length cDNA clones and synthesis of infectious RNA transcripts. J. Virol. 1994;68:3550–3557. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3550-3557.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Niu C., Nong Z., Quan D., Chen Y., Kang O., Huang W., Wei Z. Emergence and phylogenetic analysis of a novel Seneca Valley virus strain in the Guangxi Province of China. Res. Vet. Sci. 2020;130:207–211. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver S.C. Host range, amplification and arboviral disease emergence. Arch. virol. Suppl. 2005:33–44. doi: 10.1007/3-211-29981-5_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing C., Jiang J., Lu Z., Mi S., He B., Tu C., Liu X., Gong W. Isolation and characterization of Getah virus from pigs in Guangdong province of China. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1111/tbed.13567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yago K., Hagiwara S., Kawamura H., Narita M. A fatal case in newborn piglets with Getah virus infection: isolation of the virus. Nihon juigaku zasshi Japn. J. Veterin. Sci. 1987;49:989–994. doi: 10.1292/jvms1939.49.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T., Li R., Hu Y., Yang L., Zhao D., Du L., Li J., Ge M., Yu X. An outbreak of Getah virus infection among pigs in China, 2017. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2018;65:632–637. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai Y.G., Wang H.Y., Sun X.H., Fu S.H., Wang H.Q., Attoui H., Tang Q., Liang G.D. Complete sequence characterization of isolates of Getah virus (genus Alphavirus, family Togaviridae) from China. J. Gen. Virol. 2008;89:1446–1456. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.83607-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.