Abstract

The rulAB locus confers tolerance to UV radiation and is borne on plasmids of the pPT23A family in Pseudomonas syringae. We sequenced 14 rulA alleles from P. syringae strains representing seven pathovars and found sequence differences of 1 to 12% within pathovar syringae, and up to 15% differences between pathovars. Since the sequence variation within rulA was similar to that of P. syringae chromosomal alleles, we hypothesized that rulAB has evolved over a long time period in P. syringae. A phylogenetic analysis of the deduced amino acid sequences of rulA resulted in seven clusters. Strains from the same plant host grouped together in three cases; however, strains from different pathovars grouped together in two cases. In particular, the rulA alleles from P. syringae pv. lachrymans and P. syringae pv. pisi were grouped but were clearly distinct from the other sequenced alleles, suggesting the possibility of a recent interpathovar transfer. We constructed chimeric rulAB expression clones and found that the observed sequence differences resulted in significant differences in UV (wavelength) radiation sensitivity. Our results suggest that specific amino acid changes in RulA could alter UV radiation tolerance and the competitiveness of the P. syringae host in the phyllosphere.

The pPT23A plasmid family encompasses the majority of native plasmids identified in the plant-pathogenic bacterium Pseudomonas syringae; these plasmids share a gene (repA) required for plasmid replication and, in most cases, additional areas of homology (16, 30, 35, 38). pPT23A-type plasmids are diverse in size, and multiple plasmids sharing large regions of repeated sequences may be present in the same cell (3, 8, 30, 35). Plasmids in the pPT23A family can encode determinants of importance in host-pathogen interactions such as the coronatine biosynthesis locus, which increases virulence, and the avirulence genes avrD, avrPphC, and avrPphF, which affect host range (1, 21, 46). Additional sequences known to be encoded on plasmids of the pPT23A family include the stbCBAD locus involved in plasmid stability (18), copper resistance determinants (6) and the streptomycin resistance transposon Tn5393 (39), and insertion sequence elements including IS51, IS801, IS870, and IS1240 (1, 18, 30). A common feature of all of these determinants is that functional loci encoding these traits are typically limited in distribution to small groups of P. syringae pathovars.

Given the distribution of the pPT23A plasmid family throughout P. syringae pathovars, it is likely that these plasmids encode a “backbone” of traits of general importance to the P. syringae species. We are interested in the evolution of the pPT23A plasmid family in P. syringae, including determining the range of pathovars encompassed by particular plasmid lineages, characterizing genes encoded on these plasmids, and delineating the importance of horizontal transfer in pPT23A plasmid biology. In a previous study, we suggested that subgroups of pPT23A-like plasmids formed stable cohesive lineages as defined by Riley and Gordon (32), and further genetic evidence implied that individual plasmids had resided within their host strain for long time periods (39). Thus, to further understand the biology of the pPT23A plasmid family, it was desirable to study a locus that is widely distributed among P. syringae pathovars and might encode a trait of general importance.

One such locus is the rulAB operon, a homolog of the umuDC mutagenic DNA repair system first described in Escherichia coli (37). This operon encodes tolerance to UV radiation (UVR) and was recently cloned and characterized from a pPT23A-like plasmid from P. syringae pv. syringae (41). In contrast to other known pPT23A family loci, functional copies of the rulAB determinant are widely distributed and have recently been described in at least 14 pathovars of P. syringae (42). rulAB+ P. syringae strains vary widely in their tolerance to UVR (42), and we wished to determine if specific sequence alterations accounted for these observations. A functional rulAB locus is critical for the maintenance of population size on leaf surfaces that are irradiated with UV-B radiation (42). The importance of epiphytic population growth on leaf surfaces to the epidemiology of most P. syringae-host interactions (19) may explain the wide distribution of the rulAB determinant.

Our objectives in this study were (i) to compare sequences of rulA both within the pathovar syringae and among six other pathovars and (ii) to determine if the observed sequence differences affect the contribution of rulA to rulAB-mediated UVR tolerance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids utilized in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains were grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA) (Difco), respectively. P. syringae strains were grown at 28°C on King's medium B (24) or Luria-Bertani medium. When necessary, media were supplemented with the following antibiotics at the indicated concentrations (in micrograms per milliliter): ampicillin, 75; carbenicillin, 200; gentamicin, 50; kanamycin, 25; and rifampin, 100. Triparental matings, using the helper plasmid pRK2013, were done to mobilize plasmid constructs into P. aeruginosa PAO1.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study and relevant characteristics

| Strain | Relevant characteristic(s) | Source or referencea |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH10B | Plasmid-free strain used for cloning | 17 |

| P. aeruginosa PAO1 | UV-sensitive, plasmid-free host | AMC |

| Pseudomonas syringae | ||

| pv. lachrymans 1188-1 | Isolated from zucchini; California | DAC |

| pv. maculicola 438 | Isolated from crucifers; California | CLB |

| pv. phaseolicola 0886-19 | Isolated from bean; location unknown | CLB |

| pv. pisi 1086-2 | Isolated from pea; location unknown | CLB |

| pv. savastanoi 0886-21 | Isolated from olive; location unknown | CLB |

| pv. syringae | ||

| 4918 | Isolated from butterfly pea; Uganda | ICMP |

| 5D425 | Isolated from apricot; California | DCG |

| 8B48 | Isolated from ornamental pear; Oklahoma | GWS |

| A2 | Isolated from ornamental pear; Oklahoma | 38 |

| B86-17 | Isolated from bean; New York | DEL |

| BBS32-5 | Isolated from bean; Colorado | DEL |

| HS191 | Isolated from millet; Australia | AKV |

| pv. tomato | ||

| OK-1 | Isolated from tomato; Oklahoma | CLB |

| PT14 | Isolated from tomato; California | CLB |

AKV, A. K. Vidaver; CLB, C. L. Bender; AMC, A. M. Chakrabarty; DAC, D. A. Cooksey; DCG, D. C. Gross; DEL, D. E. Legard; GWS, G. W. Sundin; ICMP, International Collection of Microorganisms from Plants.

TABLE 2.

Bacterial plasmids used in this study and relevant characteristics

| Plasmida | Relevant characteristic(s) |

|---|---|

| pBluescript SK(+) | Apr; cloning vector |

| pCR2.1 | Vector for direct cloning of Taq PCR products |

| pET-5a | Apr; expression vector |

| pJB321 | Apr; broad-host-range cloning vector |

| pJJK20 | E. coli umuDC promoter amplified from pRW154 and ligated into pET-5a as SphI-XbaI |

| pJJK21 | rulAB coding sequence from B86-17 ligated into pJJK20 as NdeI-BamHI |

| pRK2013 | Helper plasmid for triparental matings |

| pRW154 | Source of the E. coli umuDC promoter |

| p183-1 | rulA PCR product from strain HS191 in pCR2.1 |

| p191-1 | rulA PCR product from strain 4918 in pCR2.1 |

| p201-1 | rulA PCR product from strain BBS32-5 in pCR2.1 |

| p202-1 | rulA PCR product from strain B86-17 in pCR2.1 |

| p202-2 | rulA coding sequence from p202-1 ligated into pJJK21 as NdeI-HindIII |

| p202A-202B | Cassette containing rulA from B86-17, rulB from B86-17, and UV-inducible umuDC promoter ligated into pJB321 as SalI-BamHI |

| p205-1 | rulA PCR product from strain 5D425 in pCR2.1 |

| p205-2 | rulA coding sequence from p205-1 ligated into pJJK21 as NdeI-HindIII |

| p205A-202B | Cassette containing rulA from 5D425, rulB from B86-17, and UV-inducible umuDC promoter ligated into pJB321 as SalI-BamHI |

| p216-1 | rulA PCR product from strain 1086-2 in pCR2.1 |

| p216-2 | rulA coding sequence from p216-1 ligated into pJJK21 as NdeI-HindIII |

| p216A-202B | Cassette containing rulA from 1086-2, rulB from B86-17, and UV-inducible umuDC promoter ligated into pJB321 as SalI-BamHI |

| p219-1 | rulA PCR product from strain 0886-19 in pCR2.1 |

| p223-1 | rulA PCR product from strain OK-1 in pCR2.1 |

| p240-1 | rulA PCR product from strain 8B48 in pCR2.1 |

| p241-1 | rulA PCR product from strain A2 in pCR2.1 |

| p241-2 | rulA coding sequence from p241-1 ligated into pJJK21 as NdeI-HindIII |

| p241A-202B | Cassette containing rulA from A2, rulB from B86-17, and UV-inducible umuDC promoter ligated into pJB321 as SalI-BamHI |

| p244-1 | rulA PCR product from strain 0886-21 in pCR2.1 |

| p244-2 | rulA coding sequence from p244-1 ligated into pJJK21 as NdeI-HindIII |

| p244A-202B | Cassette containing rulA from 0886-19, rulB from B86-17, and UV-inducible umuDC promoter ligated into pJB321 as SalI-BamHI |

| p366-1 | rulA PCR product from strain PT14 in pCR2.1 |

| p366-2 | rulA coding sequence from p366-1 ligated into pJJK21 as NdeI-HindIII |

| p366A-202B | Cassette containing rulA from PT14, rulB from B86-17, and UV-inducible umuDC promoter ligated into pJB321 as SalI-BamHI |

| p377-1 | rulA PCR product from strain 1188-1 in pCR2.1 |

Sources or references for the following plasmids are as indicated: pBluescript SK(+), Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.; pCR2.1, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.; pET-5a, Promega, Madison, Wis.; pJB321, reference 5; pRK2013, reference 12; and pRW154, reference 20. All other plasmids were generated in this study.

UV sensitivity characterization.

We used either UV-B or UV-C radiation in our UV sensitivity experiments. The UV-B sensitivity of the P. syringae strains following a dose of 590 J m−2 (biologically effective dose calculated using the DNA damage action spectrum of Setlow [36]) was determined; this survival value can be compared to those of P. syringae strains assayed previously (42). UV-C radiation also was used because the higher-energy UV-C wavelengths more readily distinguish differences in the UV sensitivity of individual strains.

We grew cells to late log phase (OD600=1.3) in LB medium containing carbenicillin. The cells were pelleted, washed in 0.85% NaCl, and resuspended at a concentration that was 10-fold less than that of the growth culture in 15 ml of 0.85% NaCl in a sterile glass petri dish (100 by 15 mm). The cell suspensions were exposed to UV-B radiation (maximum output at 302 nm) from an XX-15M UV lamp (Ultraviolet Products, Upland, Calif.) or to UV-C radiation (254 nm) from an XX-15S UV lamp. In either case, lamps were placed horizontally at a fixed height above the suspensions and turned on 15 min prior to use to allow for stabilization of the UV output. The output of the UV-B lamp was filtered through cellulose diacetate (Kodacel; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, N.Y.) to remove wavelengths below 290 nm. The energy output of the lamps was monitored with a UV-X radiometer fitted with the appropriate wavelength sensor (Ultraviolet Products) and determined to be 3.0 J m−2 s−1 for UV-B and 1.5 J m−2 s−1 for UV-C. Cells were continuously mixed during UVR exposure to eliminate survival due to shading. After irradiation, surviving cells were enumerated by dilution plating conducted under dark conditions to minimize photoreactivation.

Genetic and molecular biology techniques.

Standard molecular biology techniques were utilized. Indigenous pPT23A-like plasmids were isolated from P. syringae strains as described previously (38). Nucleotide sequencing was done using the Big Dye kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.) following the instructions of the manufacturer; sequence reactions were run at the Genetic Technologies Center, Texas A&M University. Oligonucleotides were obtained from Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, Md. The rulA nucleotide and derived amino acid sequences were aligned using the program Clustal W (43). The derived amino acid sequences were analyzed phylogenetically using the Protpars program of PHYLIP (11) as previously described (23). The derived amino acid sequence of rumA, a closely related homolog of rulA from Klebsiella pneumoniae (25), was included as the outgroup.

Genetic analysis of the rulA locus.

rulA was amplified from 14 P. syringae strains via PCR using plasmid preparations as the template and the primers rul2 (5′-CGTTAACTGTACGTCCATACAG-3′) and rul4 (5′-CGAATTGCAATCGACCAG-3′). The rul2 primer encompassed the consensus LexA-binding site upstream of the rulA coding sequence, and the rul4 primer is the reverse complement of a sequence within rulB that is highly conserved among rulB homologs from E. coli (41). Standard PCR conditions were utilized (35), except the annealing temperature was lowered to 37°C to account for possible sequence divergence at the primer sites. The size of individual amplified fragments was checked on 1.2% agarose gels, and the fragments were ligated directly into the vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). The resulting clones were utilized as source material for nucleotide sequencing.

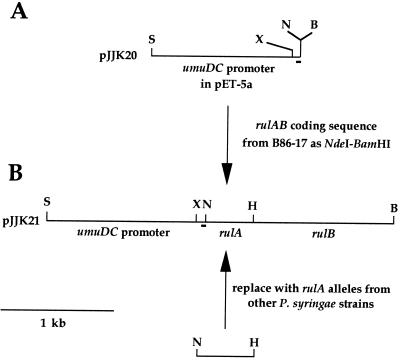

We made chimeric rulAB constructs utilizing pJJK21 (Fig. 1), a construct in the expression vector pET-5a (5) containing the rulAB coding sequence from P. syringae pv. syringae B86-17. rulAB was amplified via PCR from pB86-17A, the single indigenous plasmid harbored by strain B86-17, using the primers rulAB NdeI 5′ (5′-GGATTCCATATGAACGTCAAAATACTCGG-3′) and 3′ rulB TAA BamHI (5′-GATCGGATCCTTACTTTACAACCCACAGCTG-3′), and ligated as an NdeI-BamHI fragment into pJJK20. pJJK20 contains the SOS-inducible umuDC promoter from E. coli, which was amplified from pRW154, using the primers umu Pro 5′ SphI (5′-GATCGCATGCGAGCAATTGCGTCGC-3′) and umu Pro 3′ (5′-GTACTCTAGACTGCCTGAAGTTATACTG-3′), and ligated as an SphI-XbaI fragment into the expression vector pET-5a upstream of the NdeI site. The translational start site of the rulA coding sequence was the ATG sequence within the NdeI site; this site was located with optimal spacing from a Shine-Dalgarno sequence present on pET-5a.

FIG. 1.

Map and construction of chimeric rulAB expression clones. (A) Insertion of the umuDC promoter region from pRW154 as a SalI-XbaI fragment into pET-5a creating pJJK20. (B) Insertion of the rulAB coding sequence from P. syringae pv. syringae B86-17 as an NdeI-BamHI fragment, creating pJJK21, and replacement of the rulA allele with rulA alleles from other P. syringae strains inserted as NdeI-HindIII fragments. Restriction sites relevant for the construction are shown: B, BamHI; H, HindIII; N, NdeI; S, SalI; X, XbaI. The position of the Shine-Dalgarno sequence of pET-5a is indicated by the underscored bar.

We amplified rulA alleles from P. syringae pv. savastanoi 0886-21, P. syringae pv. syringae 5D425, 7B12, and BBS32-5, and P. syringae pv. tomato PT14 by PCR using the primers rulA 5′ NdeI (5′-GGATTCCATATGAACGTCAAAATACTCGG-3′) and rul4, digested them with NdeI-HindIII, and ligated them into pJJK21 without the rulA determinant originally present in this construct. We used primers 216 5′ NdeI (5′-GGAATTCCATATGAACGTAAAAATTCTCGGC-3′) and 216 HindIII 3′ rulA (5′-CCCAAGCTTGTTACGCCATGTCGCACAACG-3′) to amplify the rulA locus from P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2 because of extensive nucleotide sequence differences within rulA. This process altered one nucleotide in the P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2 rulA sequence to generate the HindIII site used in the cloning. The presence of the correct rulA locus within each chimeric construct was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing. Each of the resulting cassettes containing the umuDC promoter, artificial Shine-Dalgarno sequence, and the chimeric rulAB locus was excised with SalI and BamHI, ligated into pJB321, and mobilized into P. aeruginosa PAO1 for analysis.

We determined the UV sensitivity of P. aeruginosa PAO1 containing each chimeric rulAB construct. The E. coli umuDC promoter is functional in PAO1 in a UV damage-inducible fashion (J. J. Kim and G. W. Sundin, unpublished data). UV sensitivity assays using UV-C radiation were done as described above, and each experiment was performed three times. The UV sensitivity data were evaluated using an analysis of variance based on UV-C dose, and differences among the survival values were assessed using the Student-Newman-Keuls test.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The individual rulA nucleotide sequences generated in this study have been deposited in GenBank (accession numbers U43696 and AF251481 to AF251493).

RESULTS

Sequence diversity within rulA alleles.

We determined a UV tolerance phenotype for each strain except P. syringae pv. lachrymans 1188-1 and P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2, which were both highly UV sensitive (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Relevant characteristics of P. syringae strains utilized in the present study relating to rulAB carriage and nucleotide sequence alterations of rulA

| Straina | % survival following UV-B doseb | Nucleotide sequence differences with rulA from pPSR1 |

|---|---|---|

| Psl 1188-1 | 3 ± 1 | 50 |

| Psm 438 | 51 ± 12 | 37 |

| Psph 0886-19 | 62 ± 13 | 34 |

| Pspi 1086-2 | 2 ± 1 | 53 |

| Psv 0886-21 | 66 ± 13 | 31 |

| Pss A2 | 60 ± 17 | 0 |

| Pss BBS32-5 | 67 ± 17 | 23 |

| Pss B86-17 | 72 ± 19 | 23 |

| Pss 5D425 | 70 ± 18 | 26 |

| Pss 8B48 | 80 ± 15 | 28 |

| Pss HS191 | 71 ± 11 | 34 |

| Pss 4918 | 77 ± 12 | 30 |

| Pst OK-1 | 75 ± 23 | 34 |

| Pst PT14 | 60 ± 7 | 34 |

Abbreviations: Psl, P. syringae pv. lachrymans; Psm, P. syringae pv. maculicola; Psph, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola; Pspi, P. syringae pv. pisi; Pss, P. syringae pv. syringae; Pst, P. syringae pv. tomato; Psv, P. syringae pv. savastanoi.

The biologically effective (36) dose of UV-B radiation delivered (maximum output at 302 nm) was 590 J m−2, delivered using an XX-15M lamp. Results are the means ± standard deviations of three experiments per strain.

At the nucleotide level, intrapathovar sequence divergence ranged from 5 to 8% and interpathovar divergence was as high as 13% when the rulA alleles were compared to rulA from P. syringae pv. syringae A2 (Table 3). Thirty-two of the 141 amino acids (23%) were polymorphic among the strains (data not shown). A twofold-larger proportion of polymorphic sites (39%) was observed within the first 25 amino acids of the rulA sequence than in the remaining 116 amino acids (19%). The amino acids Ala25-Gly26 define a putative cleavage site where homologs of RulA such as UmuD are truncated to an activated form (36), implying that alterations in the first 25 amino acids of RulA may be more tolerated. A matrix of amino acid substitutions among the strains showed that the minimum and maximum number of amino acid differences observed among single strain pairs was 1 (1%) and 14 (10%), respectively (Table 4). The average number of amino acid differences among the sequence collection was 9% within the putative 25-amino-acid leader region and 4% within the remainder of the sequence (Table 4). rulA alleles from some P. syringae pv. syringae strains were more similar to those from other pathovars than to other strains from within the pv. syringae (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Amino acid alterations between rulA alleles from 14 P. syringae strains

| Strainb | No. of amino acid alterationsa

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pss A2 | Pss BBS32-5 | Pss B86-17 | Pss 5D425 | Pss 8B48 | Pss 4918 | Pss HS191 | Psm 438 | Psph 0886-19 | Psv 0886-21 | Pst OK-1 | Pst PT14 | Psl 1188-1 | Pspi 1086-2 | |

| Pss A2 | 1+2 | 1+3 | 2+3 | 3+3 | 2+5 | 2+7 | 1+3 | 0+4 | 1+3 | 2+3 | 2+3 | 4+6 | 4+7 | |

| Pss BBS32-5 | 1+2 | 0+1 | 1+3 | 2+3 | 3+5 | 1+6 | 0+3 | 1+4 | 0+3 | 1+3 | 1+3 | 3+6 | 3+7 | |

| Pss B86-17 | 1+3 | 0+1 | 1+4 | 2+4 | 3+6 | 1+7 | 0+4 | 1+5 | 0+4 | 1+4 | 1+4 | 3+7 | 3+8 | |

| Pss 5D425 | 2+3 | 1+3 | 1+4 | 3+4 | 4+4 | 2+6 | 1+2 | 2+3 | 1+2 | 2+2 | 2+2 | 2+5 | 2+6 | |

| Pss 8B48 | 3+3 | 2+3 | 2+4 | 3+4 | 5+6 | 3+8 | 2+4 | 3+5 | 2+4 | 3+4 | 3+4 | 5+7 | 5+8 | |

| Pss 4918 | 2+5 | 3+5 | 3+6 | 4+4 | 5+6 | 4+8 | 3+4 | 2+3 | 3+4 | 4+4 | 4+4 | 6+7 | 6+8 | |

| Pss HS191 | 2+7 | 1+6 | 1+7 | 2+6 | 3+8 | 4+8 | 1+6 | 2+7 | 1+4 | 2+6 | 2+6 | 4+9 | 4+10 | |

| Psm 438 | 1+3 | 0+3 | 0+4 | 1+2 | 2+4 | 3+4 | 1+6 | 1+3 | 0+2 | 1+2 | 1+2 | 3+5 | 3+6 | |

| Psph 0886-19 | 0+4 | 1+4 | 1+5 | 2+3 | 3+5 | 2+3 | 2+7 | 1+3 | 1+3 | 2+3 | 2+3 | 4+6 | 4+7 | |

| Psv 0886-21 | 1+3 | 0+3 | 0+4 | 1+2 | 2+4 | 3+4 | 1+4 | 0+2 | 1+3 | 1+2 | 1+2 | 3+5 | 3+6 | |

| Pst OK-1 | 2+3 | 1+3 | 1+4 | 2+2 | 3+4 | 4+4 | 2+6 | 1+2 | 2+3 | 1+2 | 0+2 | 2+5 | 2+6 | |

| Pst PT14 | 2+3 | 1+3 | 1+4 | 2+2 | 3+4 | 4+4 | 2+6 | 1+2 | 2+3 | 1+2 | 0+2 | 2+5 | 2+4 | |

| Psl 1188-1 | 4+6 | 3+6 | 3+7 | 2+5 | 5+7 | 6+7 | 4+9 | 3+5 | 4+6 | 3+5 | 2+5 | 2+5 | 0+3 | |

| Pspi 1086-2 | 4+7 | 3+7 | 3+8 | 2+6 | 5+8 | 6+8 | 4+10 | 3+6 | 4+7 | 3+6 | 2+6 | 2+4 | 0+3 | |

The first number presented in each column entry is the number of sequence differences in the putative 25-amino-acid RulA leader region. The second number is the number of sequence differences in the remaining 116 amino acids of the protein. The sum of each column entry represents the total number of amino acid differences in the entire protein.

Abbreviations: Psl, P. syringae pv. lachrymans; Psm, P. syringae pv. maculicola; Psph, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola; Pspi, P. syringae pv. pisi; Pss, P. syringae pv. syringae; Pst, P. syringae pv. tomato; Psv, P. syringae pv. Savastanoi.

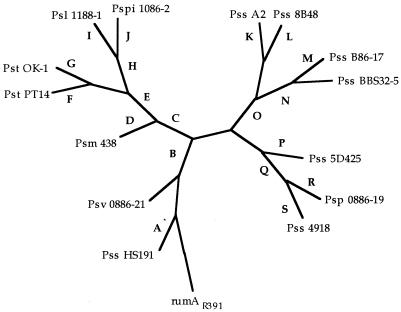

We generated a cladogram that differentiated the sequences into several subgroups (Fig. 2). Amino acid differences are shown as unique characters on the cladogram, and multiple changes may be associated with a single branching point (11). Three of the subgroups (P. syringae pv. tomato OK-1 and PT14, P. syringae pv. syringae A2 and 8B48, and P. syringae pv. syringae B86-17 and BBS32-5), contained strains that were isolated from the same plant host. In two other cases, however, subgroups (P. syringae pv. lachrymans 1188-1 and P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola 0886-19, and P. syringae pv. syringae 4918) contained strains from different pathovars and different hosts (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Radial cladogram resulting from a Protpars program of PHYLIP (11) analysis based on amino acid dissimilarities of 14 sequences of rulA from P. syringae using the homolog rumA from plasmid R391 as an outgroup. Abbreviations Psl, P. syringae pv. lachrymans; Psm, P. syringae pv. maculicola; Psph, P. syringae pv. phaseolicola; Pspi, P. syringae pv. pisi; Pss, P. syringae pv. syringae; Pst, P. syringae pv. tomato; Psv, P. syringae pv. savastanoi. The letters (arbitrarily beginning with Pss HS191) indicate the amino acid change(s) from the A2 allele at the nearest branch point. Amino acid changes are noted in single letter code for the residue in the A2 rulA allele, followed by the residue in the alleles further away from the branching point: A, M1V, D58N, V74F, P95L, Q103H; B, L91V; C, V96L, S97C; D, R79A; E, L18F; F, F39S; G, D70G; H, C10S, T20S, K80T, P118A, E125D; I, V54A; J, F39S, H106D; K, S97 (unique amino acid to Pss A2, C in other alleles); L, N2K, R8W, Q37H, F139S; M, E140G; N, D59Y; O, V96 (unchanged from A2 allele); P, E126D; Q, I121V; R, A65G; S, P17S, Y19C, D42Y, H120Q.

Functional analysis of individual rulA alleles.

We tested rulA alleles from strains representing six distinct branches of the rulA cladogram (Fig. 2). Since the constructs were identical except for the rulA allele, our assumption was that expression of rulAB from each construct was similar. Each chimeric rulAB construct had greater UV tolerance (P = 0.05) than that of PAO1 containing the vector pJB321 at each of five UV-C doses (Table 5). Significant differences in survival were observed among the alleles at four of the five UV-C doses employed (Table 5). The magnitude of survival differences increased with increasing UV-C dose, and the largest difference observed was a fourfold difference at 60 J m−2 between the rulA alleles from P. syringae pv. syringae 5D425 and P. syringae pv. savastanoi 0886-21 (Table 5). The rulA allele from P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2 was functional in these experiments, although its parental host strain is UV sensitive (Table 3).

TABLE 5.

Comparison of UV sensitivities of P. aeruginosa PAO1 containing various chimeric rulAB constructs or the vector pJB321.

| Source of rulAb | Mean % survival following irradiation with 254 nm UV-C dose of a:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 J m−2 | 24 J m−2 | 36 J m−2 | 48 J m−2 | 60 J m−2 | |

| Pathovar syringae 5D425 p205A-202B | 88 A | 67 AB | 49 A | 31 A | 14 A |

| Pathovar pisi 1086-2 p216A-202B | 86 A | 77 A | 47 A | 26 A | 9 B |

| Pathovar syringae A2 p241A-202B | 87 A | 77 A | 32 B | 21 B | 5 CD |

| Pathovar tomato PT14 p366A-202B | 85 A | 55 B | 29 B | 17 BC | 6 C |

| Pathovar savastanoi 0886-21 p244A-202B | 82 A | 50 B | 31 B | 17 BC | 4 D |

| Pathovar syringae B86-17 | |||||

| p202A-202B | 81 A | 50 B | 29 B | 13 C | 7 BC |

| pJB321 | 30 B | 4 C | 0.4 C | 0.1 D | 0.01 E |

Within a column, means not followed by the same letter are significantly different at P = 0.05, following an analysis of variance and the Student-Newman-Keuls test. Calculated R2 values (α = 0.05) for each comparison (56 df) were as follows: for 12 J m−2 14.6; for 24 J m−2, 15.4; for 36 J m−2, 7.0; for 48 J m−2, 5.4; for 60 J m−2, 2.6.

Six unique amino acid substitutions were noted among the rulA alleles examined (amino acid changes are noted in single-letter code for the original residue, followed by the residue in the unique allele): pathovar syringae 5D425, E125D; pathovar syringae A2, C97S; pathovar pisi 1086-2, K80T; pathovar savastanoi 0886-21, L91V; pathovar syringae B86-17, D58Y and E141G.

DISCUSSION

We compared rulA sequences from seven pathovars of P. syringae, as a prelude to larger-scale plasmid analyses, in an effort to define plasmid lineages within the P. syringae species. Considerable intra- and interpathovar sequence divergence was evident within the rulA gene of P. syringae, a gene which, together with rulB, encodes tolerance to UVR through a mutagenic DNA repair system. The maximum nucleotide sequence differences observed were 12% within the pathovar syringae (8B48 and HS191) and 15% between two pathovars (P. syringae pv. syringae HS191 and P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2). The minimum sequence difference observed was 1.2% between the two bean isolates of P. syringae pv. syringae, a value that is relatively high when other interstrain sequence comparisons of plasmid-borne P. syringae genes are considered (4, 44, 46). The percent divergence among rulA alleles observed in our study is similar to that observed for four chromosomal loci of P. syringae examined by Sawada et al. (33). In their study, comparisons of partial sequences of gyrB, hrpL, hrpS, and rpoD from 19 pathovars showed overall nucleotide differences ranging from approximately 4 to 15% (33).

Sequence comparisons of plasmid-borne P. syringae genes have been reported for the avirulence gene avrD (three pathovars), a 650-bp region internal to the coronafacate ligase (cfl) gene within the coronatine biosynthetic cluster (four pathovars), and the efe gene encoding the ethylene-forming enzyme (five pathovars) (4, 23, 44, 46). In contrast to results with gyrB, hrpL, hrpS, rulA, and rpoD, relatively few sequence differences were observed, even among pathovars. For example, the nucleotide sequence difference observed within the cfl gene ranged from <1 to 3%, and the efe alleles were virtually identical (< 1% sequence difference) with one exception (4, 44). Based on these comparisons, we think that the avrD, cfl, and efe genes have been disseminated more recently than rulAB among P. syringae pathovars. Alternatively, the avrD, cfl, and efe loci might be subject to strong selection pressure and unable to tolerate significant sequence alterations.

We utilized UV-B (290 to 320 nm) and UV-C (<290 nm) radiation interchangeably in our UV sensitivity analyses. The amount and spectral quality of UV-B (290 to 320 nm) radiation reaching the earth's surface is affected by geographic and physical factors and may range from 1 to >10 kJ m−2 day−1 (28). In contrast, higher-energy UV-C wavelengths are completely screened by the stratospheric ozone layer and do not reach the earth's surface; however, UV-C wavelengths more readily distinguish differences in the UV sensitivity of individual strains. In previous experiments, we have shown that rulAB confers a phenotype of UV tolerance to both UV-C and UV-B wavelengths (41, 42); such comparability is predicted because the biological effects of both UV-B and UV-C radiation are due mainly to direct DNA damage (13).

A UV-B dose of 590 J m−2 differentially affected the survival of the P. syringae strain collection (Table 3). The rulA alleles from the UV-sensitive strains P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2 and P. syringae pv. lachrymans 1188-1 differed by only three amino acids (2%), and possessed several unique subsititutions compared to the others (data not shown). The rulA from P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2 could confer UV tolerance in conjunction with the P. syringae pv. syringae B86-17 rulB allele at levels similar to that of the other alleles in the experiment (Table 5). We concluded that the UV sensitivity of P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2 was due to the presence of a nonfunctional rulB allele, analogous to the weakly functional efe allele borne on a plasmid in P. syringae pv. pisi (44). Alternatively, the UV sensitivity of strain 1086-2 could be due to the presence or absence of another genetic locus that increases the strain's UV sensitivity. Such a situation occurs on the IncJ plasmid R391, which bears the rulAB homolog rumABR391 (25) yet sensitizes its host bacterium to UV irradiation (31). Recently, a natural rulB-disruption mutant, containing a 4.5-kb insertion including the avrPpiA1 gene, was discovered in a Race 2 strain of P. syringae pv. pisi (2). We are currently analyzing the rulB alleles from P. syringae pv. pisi 1086-2 and P. syringae pv. lachrymans 1188-1 to determine if similar insertions have occurred.

We found that the six rulA alleles conferred different levels of UV tolerance to the P. aeruginosa PAO1 host. The magnitude of differences in survival increased with increasing UV-C dose, suggesting that some chimeric rulAB alleles were functionally better equipped to handle an increased load of DNA damage. The significant differences in survival observed at higher UV-C doses among the rulA alleles from P. syringae pv. savastanoi 0886-21 and P. syringae pv. syringae 5D425, A2, and B86-17 could be due to unique amino acid alterations (e.g., L91V in 0886-21, E126D in 5D425, C97S in A2, and D58Y and E141G in B86-17) since these alleles were otherwise very similar. However, we did not include the rulB alleles from these strains; thus, it is possible that the differences in survival observed due to differences in rulA could be masked by sequence differences in the rulB alleles. We wish to determine if the differences in UV survival observed affect the area on a leaf surface that can be colonized. It is known that rulAB significantly affects strain survival on leaf surfaces in the presence of UV-B radiation (42). Our current focus is to determine if subtle differences in rulAB activity can significantly impact the phyllosphere fitness of competing rulAB+strains.

rulAB appears to be important to the general biology of a wide range of P. syringae strains, and rulAB-mediated UV tolerance enables P. syringae strains to maintain population size in the phyllosphere (42). The attainment of large population sizes on individual leaves is an important prerequisite to disease incidence in some cases (19). Thus, from an ecological standpoint, it is likely that the ability of P. syringae to overcome UV stress is an important feature for its successful occupation of the phyllosphere habitat. That such a trait would be plasmid borne is consistent with Eberhard's hypothesis which states that plasmids tend to bear genes of importance in local adaptations (10). rulAB-mediated UV tolerance may be required only at certain times within the P. syringae life cycle, as strains are not constantly exposed to solar UVR.

Although extensive intrapathovar diversity occurs within P. syringae, and in particular within pathovar syringae (7, 9, 15, 26, 40, 45), some pathovars such as pathovars actinidiae and tomato are strikingly homogenous, with little observed genetic diversity (9, 34). Most P. syringae pathovars are distinct and readily distinguishable (27, 29). Indeed, comparison of sequence relatedness at the genome level has shown some pathovars (e.g., pathovars savastanoi and avellanae) are sufficiently different that reclassification into species separate from P. syringae has been proposed (14, 22). The rulA sequence variation is similar to that seen in previous studies utilizing chromosomal loci; i.e., there was considerable intrapathovar variation within P. syringae pv. syringae, and sequences from P. syringae pv. tomato were very closely related. Thus, we think that the rulAB locus has been evolving for a long period of time within P. syringae, probably mostly borne on plasmids of the pPT23A family. Further large-scale plasmid analyses are needed to unravel the evolutionary history of the pPT23A plasmid family, including identifying lineages and the pathovars that they occupy and examining the effect of residence within distinct pathovars and the effect of host plants on the ultimate composition of the plasmid genome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the researchers listed in Table 1 and Jae Kim and Roger Woodgate for bacterial strains and plasmids.

This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (NRICGP 9702832 and NRICGP 1999-02518) and the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alarcon-Chaidez F J, Penaloza-Vazquez A, Ullrich M, Bender C L. Characterization of plasmids encoding the phytotoxin coronatine in Pseudomonas syringae. Plasmid. 1999;42:210–220. doi: 10.1006/plas.1999.1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arnold D L, Jackson R W, Vivian A. Evidence for the mobility of an avirulence gene, avrPpiA1, between the chromosome and plasmids of races of Pseudomonas syringae pv. pisi. Mol Plant Pathol. 2000;1:195–199. doi: 10.1046/j.1364-3703.2000.00019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beck von Bodman S, Shaw P D. Conservation of plasmids among plant-pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae isolates of diverse origins. Plasmid. 1987;17:240–247. doi: 10.1016/0147-619x(87)90032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bereswill S, Bugert P, Volksch B, Ullrich M, Bender C L, Geider K. Identification and relatedness of coronatine-producing Pseudomonas syringae pathovars by PCR analysis and sequence determination of the amplification products. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2924–2930. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.8.2924-2930.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blatny J M, Brautaset T, Winther-Larsen H C, Haugan K, Valla S. Construction and use of a versatile set of broad-host-range cloning and expression vectors based on the RK2 replicon. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:370–379. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.370-379.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooksey D A. Genetics of bactericide resistance in plant pathogenic bacteria. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1990;28:201–219. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cournoyer B, Arnold D, Jackson R, Vivian A. Phylogenetic evidence for a diversification of Pseudomonas syringae pv. pisi race 4 strains into two distinct lineages. Phytopathology. 1996;86:1051–1056. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curiale M S, Mills D. Molecular relatedness among cryptic plasmids in Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. Phytopathology. 1983;73:1440–1444. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denny T P, Gilmour M N, Selander R K. Genetic diversity and relationships of two pathovars of Pseudomonas syringae. J Gen Microbiol. 1988;134:1949–1960. doi: 10.1099/00221287-134-7-1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eberhard W G. Evolution in bacterial plasmids and levels of selection. Q Rev Biol. 1990;65:3–22. doi: 10.1086/416582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Felsenstein J. PHYLIP—phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Figurski D H, Helinski D R. Replication of an origin containing derivative of plasmid RK2 dependent on a plasmid function provided in trans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;79:1648–1652. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedberg E C, Walker G C, Siede W. DNA repair and mutagenesis. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardan L, Bollet C, Abu Ghorrah M, Grimont F, Grimont P A D. DNA relatedness among the pathovar strains of Pseudomonas syringae subsp. savastanoi Janse (1982) and proposal of Pseudomonas savastanoi sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:606–612. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gardan L, Cottin S, Bollet C, Hunault G. Phenotypic heterogeneity of Pseudomonas syringae van Hall. Res Microbiol. 1991;142:995–1003. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(91)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbon M J, Sesma A, Canal A, Wood J R, Hidalgo E, Brown J, Vivian A, Murillo J. Replication regions from plant-pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae plasmids are similar to ColE2-related replicons. Microbiology. 1999;145:325–334. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grant S G, Jessee J, Bloom F R, Hanahan D. Differential plasmid rescue from transgenic mouse DNAs into Escherichia coli methylation-restriction mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4645–4649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanekamp T, Kobayashi D, Hayes S, Stayton M M. Avirulence gene D of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato may have undergone horizontal gene transfer. FEBS Lett. 1997;415:40–44. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01089-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hirano S S, Upper C D. Population biology and epidemiology of Pseudomonas syringae. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1990;28:155–177. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ho C, Kulaeva O I, Levine A S, Woodgate R. A rapid method for cloning mutagenic DNA repair genes: isolation of umu-complementing genes from multidrug resistance plasmids R391, R446b, and R471a. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:5411–5419. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.17.5411-5419.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jackson R W, Athanassopolous E, Tsiamis G, Mansfield J W, Sesma A, Arnold D L, Gibbon M J, Murillo J, Taylor J D, Vivian A. Identification of a pathogenicity island, which contains genes for virulence and avirulence, on a large native plasmid in the bean pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pathovar phaseolicola. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:10875–10880. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janse J D, Rossi P, Angelucci L, Scortichini M, Derks J H J, Akermans A D L, De Vrijer R, Psallidas P G. Reclassification of Pseudomonas syringae pv. avellanae as Pseudomonas avellanae (spec. nov.) the bacterium causing canker of hazelnut (Corylus avellanae L.) Syst Appl Microbiol. 1996;19:589–595. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keith L W, Boyd C, Keen N T, Partridge J E. Comparison of avrD alleles from Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1997;10:416–422. doi: 10.1094/MPMI.1997.10.3.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.King E O, Ward N K, Raney D E. Two simple media for the detection of pyocyanin and fluorescein. J Lab Clin Med. 1954;44:301–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kulaeva O I, Wootton J C, Levine A S, Woodgate R. Characterization of the umu-complementing operon from R391. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2737–2743. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2737-2743.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Legard D E, Aquadro C F, Hunter J E. DNA sequence variation and phylogenetic relationships among strains of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae inferred from restriction site maps and restriction fragment length polymorphism. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:4180–4188. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.12.4180-4188.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Louws F J, Fulbright D W, Stephens C T, de Bruijn F J. Specific genomic fingerprints of phytopathogenic Xanthomonas and Pseudomonas pathovars and strains generated with repetitive sequences and PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2286–2295. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.7.2286-2295.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madronich S, McKenzie R L, Bjorn L O, Caldwell M M. Changes in biologically active ultraviolet radiation reaching the Earth's surface. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1998;46:5–19. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(98)00182-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manceau C, Horvais A. Assessment of genetic diversity among strains of Pseudomonas syringae by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of rRNA operons with special emphasis on P. syringae pv. tomato. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:498–505. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.2.498-505.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Murillo J, Keen N T. Two native plasmids of Pseudomonas syringae pathovar tomato strain PT23 share a large amount of repeated DNA including replication sequences. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:941–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pembroke J T, Stevens E. The effect of plasmid R391 and other IncJ plasmids on the survival of Escherichia coli after UV irradiation. J Gen Microbiol. 1984;130:1839–1844. doi: 10.1099/00221287-130-7-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riley M A, Gordon D M. A survey of Col plasmids in natural isolates of Escherichia coli and an investigation into the stability of Col plasmid lineages. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:1345–1352. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-7-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sawada H, Suzuki F, Matsuda I, Saitou N. Phylogenetic analysis of Pseudomonas syringae pathovars suggests the horizontal gene transfer of argK and the evolutionary stability of hrp gene cluster. J Mol Evol. 1999;49:627–644. doi: 10.1007/pl00006584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sawada H, Takeuchi T, Matsuda I. Comparative analysis of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae and pv. phaseolicola based on phaseolotoxin-resistant ornithine carbamytransferase gene (argK) and 16S–23S rRNA intergenic spacer sequences. App1. Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:282–288. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.1.282-288.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sesma A, Sundin G W, Murillo J. Closely related plasmid replicons in the phytopathogen Pseudomonas syringae show a mosaic organization of the replication region and an altered incompatibility behavior. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1998;64:3948–3953. doi: 10.1128/aem.64.10.3948-3953.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Setlow R B. The wavelengths of sunlight effective in producing skin cancer: a theoretical analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1974;71:3363–3366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.9.3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smith B T, Walker G C. Mutagenesis and more: umuDC and the Escherichia coli SOS response. Genetics. 1998;148:1599–1610. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.4.1599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sundin G W, Bender C L. Ecological and genetic analysis of copper and streptomycin resistance in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1018–1024. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.4.1018-1024.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sundin G W, Bender C L. Molecular analysis of closely-related copper- and streptomcyin-resistance plasmids in Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Plasmid. 1996;35:98–107. doi: 10.1006/plas.1996.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sundin G W, Demezas D H, Bender C L. Genetic and plasmid diversity within natural populations of Pseudomonas syringae with various exposures to copper and streptomycin bactericides. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:4421–4431. doi: 10.1128/aem.60.12.4421-4431.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sundin G W, Kidambi S P, Ullrich M, Bender C L. Resistance to ultraviolet light in Pseudomonas syringae: sequence and functional analysis of the plasmid-encoded rulAB genes. Gene. 1996;177:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(96)00273-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sundin G W, Murillo J. Functional analysis of the Pseudomonas syringae rulAB determinant in tolerance to ultraviolet B (290–320 nm) radiation and distribution of rulAB among P. syringae pathovars. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:75–87. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Clustal W—improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weingart H, Volksch B, Ullrich M S. Comparison of ethylene production by Pseudomonas syringae and Ralstonia solanacearum. Phytopathology. 1999;89:360–365. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.1999.89.5.360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Young J M. Pathogenicity and identification of the lilac pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae van Hall 1902. Ann Appl Biol. 1991;118:283–298. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yucel I, Boyd C, Debnam Q, Keen N T. Two different classes of avrD alleles occur in pathovars of Pseudomonas syringae. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact. 1994;7:131–139. doi: 10.1094/mpmi-7-0131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]