Abstract

Introduction

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI), a significant predictor of suicide, is more frequent in sexual minorities (e.g., lesbian, gay, and bisexual) than in heterosexuals. The Minority Stress Model proposed that sexual minority stigma (SMS) may lead to maladaptive behaviors, including NSSI. However, the potential mechanism underlying the relationship between SMS and NSSI remains unclear. Therefore, the current study will examine the relationship between SMS and NSSI, and explore the serial mediating roles of sexual orientation concealment (SOC), self-criticism, and depression.

Methods

A total of 666 individuals who self-identified as sexual minorities (64.0% male, Mage = 24.49 years, SD = 6.50) completed questionnaires of SMS, SOC, self-criticism, depression, and NSSI, in 2020.

Results

The findings indicated that (1) SMS, SOC, self-criticism, depression, and NSSI were positively correlated; (2) SOC, self-criticism, and depression independently played partial mediating roles between SMS and NSSI; and (3) SOC, self-criticism, and depression played serial mediating roles between SMS and NSSI.

Conclusions

The current study supported the relation between SMS and NSSI among Chinese sexual minorities, and also implied a potential mechanism underlying the relation. Specifically, SMS was related to increased NSSI by higher SOC, self-criticism, and depression. SOC had dual-edged effects on NSSI.

Policy Implications

To reduce NSSI and other psychological problems among sexual minorities, policy makers should take more measures to eliminate SMS. Specifically, policy makers are encouraged to provide more support for changing sexual minorities’ living environment, such as repealing bills that could cause SMS and popularizing the knowledge about sexual orientation.

Keywords: Sexual minority stigma, Nonsuicidal self-injury, Sexual orientation concealment, Self-criticism, Depression

Introduction

Nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) is defined as one’s behaviors that intentionally and directly damage their own body without suicidal intent (Nock, 2009). NSSI has been a subject of clinicians’ and researchers’ recognition (Liu et al., 2019; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) due to its associations with adverse psychological outcomes, including comorbid psychopathology (Buelens et al., 2020) and even suicidal behaviors (You & Lin, 2015). Certain populations, such as sexual minorities (e.g., lesbian, gay, and bisexual, Hottes et al., 2016), showed an especially high prevalence of NSSI (Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2017). For example, Batejan et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis and found that on average, 40.5% of sexual minority participants reported a history of NSSI, compared to 24.4% of heterosexual participants. Considering the high prevalence of NSSI in sexual minorities, the current study aims to explore the risk factors for NSSI in this group.

Sexual Minority Stigma and NSSI

Growing evidence suggests that sexual minority stigma may be a fundamental cause of higher NSSI prevalence among sexual minorities (Jackman et al., 2018). Sexual minority stigma (SMS) refers to the rejection and discrimination from others caused by sexual minority identity (Meyer, 2003). In recent years, the public acceptance of minority sexual orientations has been increasing. For example, the UK launched the “Marriage (Same-sex Couples)” Act in 2013. However, in China, a relatively conservative and collectivistic country (Su & Zheng, 2021), sexual minorities still experience high SMS (Decamp & Bakken, 2016). Specifically, the Chinese culture emphasizes family, and expects all people to have heterosexual marriages and children (Li et al., 2021). Thus, sexual minorities would frequently encounter rejection and discrimination in China (Chan & Leung, 2021). Such high SMS would make them live in a hostile environment (Liu et al., 2019) and endure intense social stresses, thus leading them more susceptible to psychological problems (e.g., NSSI). Previous empirical studies supported the relationship between SMS and NSSI (Busby et al., 2020; Smith et al., 2020; Staples et al., 2018).

Despite the evidences for the relation between SMS and NSSI, the potential mechanism underlying the relationship remains largely unclear. According to the Minority Stress Theory proposed by Meyer (2003), minority stresses that are uniquely experienced by sexual minorities include distal stresses (the external, objective stresses, e.g., SMS) and proximal stresses (the internal, subjective stresses, e.g., sexual orientation concealment) (Staples et al., 2018). The distal stresses would contribute to proximal stresses, thus increasing the risks of maladaptive behaviors (i.e., distal stresses → proximal stresses → maladaptive behaviors; Liu et al., 2021; Meyer, 2003). In this study, we aimed to examine the mediating role of sexual orientation concealment as a proximal stress underlying the path from SMS to NSSI.

Sexual Minority Stigma, Sexual Orientation Concealment, and NSSI

Sexual orientation concealment (SOC) is common in sexual minorities (Hetrick & Martin, 1987). Goh et al. (2019) have found that more than half of sexual minorities (51.1%) would choose to conceal their sexual orientation during interpersonal interactions. Those with SOC may subtly keep their sexual orientation undetectable or even explicitly claim they are heterosexual (Cohen et al., 2016). According to the Minority Stress Theory, SOC may be due to SMS (Meyer, 2003). Sexual minorities with high SMS believe that their sexual orientation may expose them to negative evaluations or teasing (Oshana et al., 2020). Thus, they may choose to conceal their sexual orientation. Numerous studies have revealed that the higher degree of SMS, the higher motivation for SOC (Goffman, 1963; Goh et al., 2019). The relation from SMS to SOC may be even stronger in China, because the collectivistic culture emphasizes interpersonal relationships, and Chinese sexual minorities may be more likely to conceal their sexual orientation for maintaining relationships and avoiding discrimination (Sun et al., 2021).

Although SOC may be useful in helping sexual minorities avoid SMS (Goh et al., 2019; Pachankis et al., 2020), there is an attached cost of SOC. SOC may act as an internal stressor, damaging sexual minorities’ mental health (Hatzenbuehler, 2009; Meyer, 2003) and rendering them susceptible to NSSI. Specifically, those with SOC may be highly alert to notice whether, when, or how their sexual orientation is disclosed (Pachankis et al., 2020). Such high vigilance may increase their likelihood of engaging in NSSI (O’ Connor & Kirtley, 2018), because NSSI could immediately distract them from the constant alert and release their stresses (Selby et al., 2008). Thus, we reasonably predict that SMS will lead to SOC, which will then further contribute to NSSI.

Self-Criticism and Depression in Sexual Minorities

Hatzenbuehler (2009) proposed the psychological mediation framework, stating that the negative psychological processes may play a mediating role in the relationship between the minority stresses and maladaptive behaviors (i.e., minority stresses → negative psychological processes → maladaptive behaviors). Minority stresses (e.g., SMS and SOC) may exacerbate the negative cognitions (e.g., self-criticism) and negative emotions (e.g., depression) among sexual minorities, and may further lead to the engagement of NSSI (Pachankis et al., 2020).

Regarding negative cognitions, we focus on the role of self-criticism. Self-criticism refers to the automatic, negative self-evaluation. Those with high self-criticism tend to focus on their own inadequacies, and even loathe themselves (Gilbert et al., 2004; Gong et al., 2019). Sexual minorities experienced higher levels of self-criticism than heterosexuals (Nappa et al., 2021), which may result from the following two reasons. On the one hand, self-criticism may derive from SMS. According to the Social Learning Theory (Bandura et al., 1977), sexual minorities may internalize the negative other-evaluations (i.e., SMS) as negative self-evaluations (Liu et al., 2021). On the other hand, SOC caused by SMS may also make sexual minorities more susceptible to self-criticism. Those with SOC may sometimes keep their sexual minority identity undetected (Oshana et al., 2020). Such concealing behavior may provoke them into self-criticism. As such, sexual minorities with high self-criticism are more likely to engage in NSSI for self-punishment (Gong et al., 2019; Hooley & Franklin, 2018). Thus, we hypothesize that SOC and self-criticism would mediate the relationship between SMS and NSSI.

When exploring the potential mechanism underlying the relationship between minority stresses and NSSI, we cannot ignore depression as a negative emotion. Argyriou et al. (2021) conducted a meta-analysis and revealed the increased depression rates in sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals. The increased rates may be due to two major reasons. First, according to the Minority Stress Theory, SMS and SOC, both as minority stresses, would increase the risk for depression (Meyer, 2003). Previous studies have found that sexual minorities who experienced SMS and SOC were at higher risks of depression (Cohen et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2021). Second, high self-criticism caused by SMS and SOC may also aggravate depression in sexual minorities (Aruta et al., 2021; Joeng & Turner, 2015; Mongrain & Leather, 2006). Given that depression is a proximal risk factor for NSSI (Barrocas et al., 2015; Taliaferro & Muehlenkamp, 2017), we will examine the pathways of “SMS → SOC → depression → NSSI” and “SMS → SOC → self-criticism → depression → NSSI.”

The Current Study

Although the higher risk of NSSI in sexual minorities has been widely recognized, there are limited studies in exploring the mechanisms of NSSI in sexual minorities. Thus, the current study aims to clarify the mechanism of NSSI among sexual minorities (in this article, we include homosexuals and bisexuals) by proposing the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. Sexual minority stigma would be positively associated with NSSI (i.e., SMS → NSSI).

Hypothesis 2. Sexual orientation concealment would play a mediating role in the relationship between sexual minority stigma and NSSI (i.e., SMS → SOC → NSSI).

Hypothesis 3. Sexual minority stigma would affect NSSI through a serial mediation of sexual orientation concealment and self-criticism (i.e., SMS → SOC → self-criticism → NSSI).

Hypothesis 4. Sexual minority stigma would affect NSSI through a serial mediation of sexual orientation concealment and depression (i.e., SMS → SOC → depression → NSSI).

Hypothesis 5. Sexual minority stigma would affect NSSI through a serial mediation of sexual orientation concealment, self-criticism, and depression (i.e., SMS → SOC → self-criticism → depression → NSSI).

Method

Procedure and Participants

The data collection for this study took place in August 2020. We integrated the questionnaires about study variables through “Wenjuanxing” (a professional survey website, www.sojump.com). And then we posted the whole questionnaire on the WeChat Official Account of the Beijing LGBT Center, which is a non-profit organization dedicated to changing the living environment of Chinese sexual minorities. Before conducting the survey, we obtained participants’ informed consent. Although adolescents under 18 years old may be included, informed consent was not obtained from their guardians for two reasons. One was that our study was completely anonymous, making it impossible to contact their parents. The other was that some adolescents still had not disclosed their sexual orientation to their parents.

In addition, participants were informed of the anonymity of their filling process and the confidentiality of their answers, as well as the right to stop filling in at any time and for any reason. If participants experienced psychological discomfort during or after completing the questionnaire, they could seek mental health services through the Beijing LGBT Center. Meanwhile, this study provided the participants with an incentive that for each completed questionnaire, the research team will donate 3¥ to the Beijing LGBT Center. And this incentive was presented in a tweet on the WeChat Official Account of the Beijing LGBT Center. The entire procedure was approved by the ethics committee of the first author (No., SCNU-PSY-2021–265).

The questionnaire was completed by 925 individuals. We deleted the data from 259 participants for the following reasons: 16 of them spent more than 1904.67 s (i.e., Mtime + 3 SD), 67 spent less than 300 s, and 176 participants indicated their self-orientation as asexual, pansexual, uncertain, and the others. Finally, 666 sexual minority individuals were included as the final participants.

Materials

Sexual Minority Stigma

This study used the China Homosexuality Stigma Scale (Neilands et al., 2008) to measure SMS perceived by sexual minorities in the past year. The scale includes three dimensions (i.e., perceived stigma, enacted stigma, and other stigmas). The perceived stigma subscale has three items (e.g., How often have you heard that homosexuals are not normal?), the enacted stigma subscale has six items (e.g., How often has your family not accepted you because of your homosexuality?), and the other stigma subscale only has one item (i.e., How often have you been made fun of or called names for being homosexuals?). All items were rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 (never), 2 (sometimes), 3 (often), to 4 (always). Given that the participants of this study would include bisexual populations, the subjects of the items were changed to “homosexuals or bisexuals.” Higher sum scores indicated higher levels of SMS. The original scale has shown good reliability and validity among sexual minority men and women in previous studies (Chakrapani et al., 2017; Ding et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021), and the Cronbach’s alpha of the revised scale was 0.72 in this study.

Sexual Orientation Concealment

The Sexual Orientation Concealment Scale (Schrimshaw et al., 2013) was adopted to assess SOC. The scale originally measured the concealment of same-sex sexual behaviors (e.g., I haven’ t shared with anyone that I have sex with other men). However, some researchers suggested that having sex with men does not identify one’s sexual minority identity (Meyer & Wilson, 2009). Thus, according to previous studies (Li et al., 2021), we modified the scale to measure the concealment of “liking people of the same sex” (e.g., I haven’ t shared with anyone that I like people of the same sex). All seven items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Higher sum scores showed higher levels of SOC. In our sample, the Cronbach’s alpha of the modified scale was 0.89.

Self-Criticism

The Inadequate self (IS) and Hated self (HS) subscales of “The Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale” (FSCRS; Gilbert et al., 2004) were used to assess sexual minorities’ self-criticism in the past year. The IS subscale has 9 items (e.g., I remember and dwell on my failings), focusing on self-criticism caused by caring about inadequacies; the HS subscale has 5 items (e.g., I do not like being me), focusing on self-criticism caused by self-loathing (Leboeuf et al., 2020). Each item was rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all like me) to 5 (extremely like me). According to previous studies (Lear et al., 2020), higher sum scores of the 14 items indicated higher levels of self-criticism. This 14-item scale has shown high reliability and validity in a study of thirteen international samples (Júlia et al., 2019), and the Cronbach’s alpha of the scale in this study was 0.92.

Depression

This study used the Depression subscale of the Chinese version of the short Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) to measure depressive symptoms in the past year. The 7-item scale was rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all like me) to 3 (extremely like me). Higher sum scores indicated higher depression. The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale was 0.91 in the current study.

NSSI

The NSSI behavior in this study includes a total of 12 categories (i.e., self-cutting, burning, carving words or pictures on the skin, scratching the skin to bleeding, inserting objects into the nail or skin, hair pulling, biting to bleeding, erasing skin, dripping acid onto skin, scrubbing skin using bleach or cleaner, hitting the head or other body parts violently to cause bruising, and punching to bruising), deriving from the Deliberate Self-Harm Inventory (DSHI; Gratz, 2001) and the Ottawa Self-Injury Inventory (OSI; Martin et al., 2013). The question presented in the questionnaire was “In the past one year, have you engaged in the following behaviors to deliberately harm yourself, but without suicidal intent?” Participants were asked to report the frequencies they engaged in the above behaviors by a 6-point scale ranging from 0 (never), 1 (once), 2 (twice), 3 (three times), 4 (four times), to 5 (five times or more). Higher sum scores indicated more frequent NSSI behaviors. The Cronbach’s alpha of this scale in this study was 0.84.

Analysis Plan

The preliminary analyses were conducted by SPSS 23.0 (IBM Corp, 2016). First, we examined the missing data in the study. Among all study variables, only SMS and SOC had missing values. Specifically, among the 666 participants, one participant missed on SOC and 13 participants missed on SMS. The Little’s MCAR test showed that the data were missing completely at random, χ2 (445) = 383.726, p = 0.984. Thus, we replaced the missing data with means (Golam et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). Second, we performed descriptive statistics, skewness and kurtosis tests, and Spearman correlation analysis for the main variables. As the skewness and kurtosis of NSSI (skewness = 3.454 and kurtosis = 13.179) exceeded the acceptable range (i.e., skewness < 3 and kurtosis < 10, Kline, 2016), we corrected it by log transformation (skewness = 1.616 and kurtosis = 1.413) and used the corrected data in the subsequent analyses. Third, the differences of demographic variables in NSSI scores were examined by the unpaired t test (for demographic variables with two categories, including gender, sexual orientation, and family location) and univariate ANOVAs (for demographic variables with more than two categories, including stable intimate relationship, employment status, educational level, and subjective economic level).

Finally, we tested the serial mediation models under the structural equation modeling framework by using Mplus 7.0 (Muthen & Muthen, 2017). To verify the order of the mediators (SOC, self-criticism, depression), we constructed five competing models by reversing the mediators (model 1: SMS → SOC → depression → self-criticism → NSSI; model 2: SMS → self-criticism → SOC → depression → NSSI; model 3: SMS → self-criticism → depression → SOC → NSSI; model 4: SMS → depression → SOC → self-criticism → NSSI; Model 5: SMS → depression → self-criticism → SOC → NSSI), and compared the fit indices of the above competing models and the proposed model (SMS → SOC → self-criticism → depression → NSSI). We used the following criteria to evaluate model fit (Browne & Cudeck, 1992): comparative fit index (CFI) values and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) values above 0.90, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) less than 0.08. A bias-corrected bootstrap method based on 1000 samples was used to estimate the standard errors of the indirect effects. In this method, the 95% bias correction (BC) confidence interval (CI) excluding zero indicated the significance of the path. The Wald chi-square tests were used to compare the differences in the indirect effect size. Age, gender, and sexual orientation were included as covariates in examining the proposed serial mediation model. In all our analyses, the significance level was 0.05 (i.e., a = 0.05).

Results

Participants

The final sample included 666 sexual minority participants aged from 12 to 59 (64.0% males, 36.0% females, which all refer to their sex assigned at birth; Mage = 24.49 years, SD = 6.50). Among the male participants, 90.8% (n = 387) identified as gay, 9.2% (n = 39) as bisexual. Among the female participants, 45.4% (n = 109) identified as lesbian, 54.6% (n = 131) as bisexual. In terms of subjective economic level, 12.6% (n = 84) of the participants perceived their economic levels as below the local average, 18.8% (n = 125) perceived their economic levels as above the local average, and the others (n = 457) perceived their economic levels as comparable to the local average. More demographic information and its details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristic and differences on NSSI scores (N = 666)

| Characteristics | N (%) | Mean ± SD | t/F | df | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 426 (64.00) | 0.163 ± 0.341 | − 6.027 | 367.777 | 0.000*** |

| Female | 240 (36.00) | 0.380 ± 0.498 | ||||

| Sexual orientation | Homosexual | 496 (74.50) | 0.204 ± 0.390 | − 3.650 | 251.546 | 0.000*** |

| Bisexual | 170 (25.50) | 0.351 ± 0.474 | ||||

| Family location | Rural | 138 (20.70) | 0.208 ± 0.384 | − 1.048 | 664 | 0.295 |

| City | 528 (79.30) | 0.250 ± 0.426 | ||||

| Stable intimate relationship | One year | 172 (25.80) | 0.207 ± 0.418 | 0.401 | 2 | 0.670 |

| Over 1 year | 77 (11.60) | 0.234 ± 0.423 | ||||

| No | 417 (62.60) | 0.257 ± 0.415 | ||||

| Employment status | Students at school | 319 (47.90) | 0.310 ± 0.468 | 1.459 | 3 | 0.225 |

| Working within the Institution | 97 (14.60) | 0.143 ± 0.325 | ||||

| Working outside the Institution | 188 (28.20) | 0.164 ± 0.334 | ||||

| Others | 62 (9.30) | 0.274 ± 0.439 | ||||

| Educational level | Elementary school and below | 1 (0.20) | 1.255 ± (-) | 1.991 | 4 | 0.094 |

| Junior high school | 27 (4.10) | 0.607 ± 0.571 | ||||

| High school | 104 (15.60) | 0.376 ± 0.486 | ||||

| Undergraduate | 419 (62.90) | 0.211 ± 0.392 | ||||

| Master and above | 115 (17.30) | 0.134 ± 0.306 | ||||

| Economic level | Lower than the local average Level | 84 (12.60) | 0.287 ± 0.401 | 0.110 | 2 | 0.896 |

| At the local average level | 457 (68.60) | 0.240 ± 0.420 | ||||

| Higher than the local average level | 125 (18.80) | 0.216 ± 0.420 | ||||

***p < 0.001

Descriptive Statistics

In our sample, the 12-month prevalence of NSSI was 31.08% (n = 207). Among all participants engaging in NSSI, 40.10% (n = 83) have only taken one method of NSSI, and 20.77% (n = 43) have engaged in NSSI only once. Hair pulling (58.45%) was the most common way of NSSI, followed by scratching the skin to bleeding (37.20%), self-cutting (36.72%), biting to bleeding (35.27%), hitting the head or other body parts violently to cause bruising (28.50%), carving words or pictures on the skin (28.02%), punching to bruising (19.81%), inserting objects into the nail or skin (17.39%), erasing skin (16.43%), and burning (5.31%). In this study, no participants used dripping acid onto skin, or scrubbing skin using bleach or cleaner.

Table 1 presents the prevalence of NSSI in different demographic characteristics. We found that sexual minority women (M = 0.380, SD = 0.498) had more frequent NSSI (t = −6.027, p < 0.001) than sexual minority men (M = 0.163, SD = 0.341); bisexuals (M = 0.351, SD = 0.474) had more frequent NSSI (t = −3.650, p < 0.001) than homosexuals (M = 0.204, SD = 0.390).

Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics (i.e., mean, SD, skewness, and kurtosis) of all research variables, as well as the correlations between them. We found significant correlations between SMS, SOC, self-criticism, depression, and NSSI (r ranging from 0.232 to 0.691). Only the correlation between SOC and NSSI was not significant (r = 0.020, p = 0.191). Age was significantly and negatively associated with self-criticism (r = −0.213, p < 0.001) and NSSI (r = −0.251, p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlations among the study variables

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | - | |||||

| SMS | 0.060 | - | ||||

| SOC | 0.029 | 0.332*** | - | |||

| Self-criticism | − 0.213*** | 0.330*** | 0.243*** | - | ||

| Depression | 0.062 | 0.311*** | 0.232*** | 0.691*** | - | |

| NSSI | − 0.251*** | 0.176*** | 0.020 | 0.423*** | 0.411*** | - |

| Mean | 24.488 | 17.755 | 17.610 | 42.976 | 5.375 | 2.458 |

| SD | 6.497 | 4.183 | 6.697 | 11.017 | 5.312 | 6.074 |

| Skewness | 1.110 | 1.008 | 0.385 | 0.120 | 1.108 | 3.454 |

| Kurtosis | 1.907 | 1.762 | − 0.367 | − 0.196 | 0.512 | 13.179 |

SMS sexual minority stigma, SOC sexual orientation concealment, NSSI nonsuicidal self-injury

***p < 0.001

Thus, age, sexual orientation, and gender were controlled for in the following model tests.

Mediation Analysis

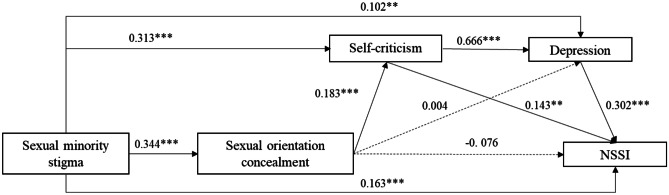

We used Mplus 7.0 to test the proposed serial mediation model and other competing models while controlling for age, gender, and sexual orientation. The model fit indices are presented in Table 3. The proposed model showed the greatest model fit, χ2 (6) = 29.931, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.976, RMSEA = 0.077 [0.051, 0.106], SRMR = 0.026, and was chosen for the subsequent analysis. The standardized path coefficients for the proposed serial mediation model are presented in Fig. 1. The effect sizes of the various indirect pathways between SMS and NSSI are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

Model fit indexes for the conceptual model and the five alternative mediation models

| df | χ2 (df) | CFI | RMSEA | SRMR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The proposed model | 6 | 29.931 | 0.976 | 0.077 | 0.026 |

| Model 1 | 6 | 41.130 | 0.965 | 0.094 | 0.040 |

| Model 2 | 6 | 39.960 | 0.967 | 0.091 | 0.030 |

| Model 3 | 6 | 38.960 | 0.967 | 0.091 | 0.030 |

| Model 4 | 6 | 41.130 | 0.965 | 0.094 | 0.040 |

| Model 5 | 6 | 47.962 | 0.958 | 0.102 | 0.043 |

The proposed model: SMS → SOC → self-criticism → depression → NSSI

Model 1: SMS → SOC → depression → self-criticism → NSSI

Model 2: SMS → self-criticism → SOC → depression → NSSI

Model 3: SMS → self-criticism → depression → SOC → NSSI

Model 4: SMS → depression → SOC → self-criticism → NSSI

Model 5: SMS → depression → self-criticism → SOC → NSSI

Fig. 1.

Standardized path coefficients for the proposed multiple mediation model. Note. Potential confounding variables were controlled in the model as covariates, including gender, age, and sexual orientation. The solid lines indicated significant coefficients, while dashed lines indicated insignificant coefficients. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

Table 4.

Direct and indirect effects

| β | SE | p | 95% BC CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect of SMS on NSSI | 0.163 | 0.041 | 0.000 | 0.084, 0.239 |

| Total indirect effect | 0.135 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.091, 0.182 |

| Indirect effect via SOC | − 0.026 | 0.013 | 0.040 | − 0.052, − 0.002 |

| Indirect effect via SOC and self-criticism | 0.009 | 0.004 | 0.013 | 0.003, 0.018 |

| Indirect effect via SOC and depression | 0.000 | 0.003 | 0.906 | − 0.007, 0.007 |

| Indirect effect via SOC, self-criticism, and depression | 0.013 | 0.004 | 0.002 | 0.005, 0.018 |

| Indirect effect via self-criticism | 0.045 | 0.016 | 0.004 | 0.015, 0.079 |

| Indirect effect via self-criticism and depression | 0.063 | 0.013 | 0.040 | 0.042, 0.091 |

| Indirect effect via depression | 0.031 | 0.011 | 0.004 | 0.012, 0.054 |

SMS sexual minority stigma, SOC sexual orientation concealment, NSSI nonsuicidal self-injury

The results showed that the direct path from SMS to NSSI was positive (β = 0.163, p < 0.001, 95% CI = [0.084, 0.239]), consistent with hypothesis 1. However, the indirect effect of the “SMS – SOC – NSSI” pathway was negative, b = −0.026, SE = 0.013, 95% CI = [−0.052, −0.002]. Thus, we found an inconsistent mediation model in which the direct effect and indirect effect had opposite signs, and suggested that SOC may have some protective effect on NSSI. But the other paths containing SOC were positive, such as the path “SMS – SOC – self-criticism – NSSI” (b = 0.009, SE = 0.004, 95% CI = [0.003, 0.018]) and the path “SMS – SOC – self-criticism – depression – NSSI” (b = 0.013, SE = 0.004, 95% CI = [0.006, 0.020]). Thus, we conducted the Wald chi-square test to further compare the indirect effect sizes of these pathways. The results showed that the effect sizes of the “SMS – SOC – self-criticism – NSSI” path (Wald [χ2] = 8.645, p < 0.01) and “SMS – SOC – self-criticism – depression – NSSI” path (Wald [χ2] = 9.528, p < 0.01) were both significantly stronger than that of the “SMS – SOC – NSSI” path. Therefore, in the current study, we found that SOC exerted dual-edged effects on NSSI among sexual minorities, and its adverse effects may outweigh its protective effects.

Meanwhile, the independent mediation effects of self-criticism (b = 0.045, SE = 0.016, 95% CI = [0.016, 0.079]) and depression (b = 0.031, SE = 0.011, 95% CI = [0.012, 0.054]) were all significant. And the serial mediation effect of self-criticism and depression (b = 0.063, SE = 0.012, 95% CI = [0.042, 0.091]) were also significant.

Discussions

Previous studies have suggested that sexual minorities experienced high SMS in China (Chan & Leung, 2021), but the potential impact of SMS on Chinese sexual minorities has rarely been explored. Thus, we examined the potential impact of SMS on NSSI and the mediating roles of SOC, self-criticism, and depression among Chinese sexual minorities. Next, we will discuss our findings in detail.

First, in the current study, the prevalence of NSSI among sexual minorities was 31.08%, which was consistent with those in previous studies (Taliaferro et al., 2017; Liu et al., 2019). Hair pulling was the most common NSSI method in the sample. The result is inconsistent with previous results that self-cutting was the most common NSSI method in general populations (Lin et al., 2018; Tatnell et al., 2018). This inconsistency may be due to that sexual minorities are more likely to engage in NSSI behaviors that would not cause scars, because visible scars would exacerbate the perceived stigma of sexual minorities.

Consistent with previous research (Monto et al., 2018), our results showed that sexual minority females reported more frequent NSSI than sexual minority males. The gender difference may be partially due to females’ high emotional intensity and reactivity (Gao et al., 2021; Ueno, 2010), both of which are vulnerability factors for NSSI (O’Connor et al., 2012). Group difference of sexual orientations also existed in NSSI frequencies, with bisexuals more frequently engaging in NSSI than homosexuals. In fact, a growing body of research suggested that bisexuals were at higher risk for maladaptive behaviors (Nystedt et al., 2019; Plöderl & Tremblay, 2015), because they may experience discrimination from both homosexuals and heterosexuals (Dodge et al., 2016).

Second, we found SOC’s dual-edged effects on mental health among sexual minorities. SOC had a negative association with NSSI and a positive association with self-criticism. Its negative association with NSSI may be due to that SOC temporarily keeps sexual minorities away from SMS, making them feel relatively secure and thus alleviating their risks of NSSI. Indeed, our study is not the first empirical article that identified the protective effect of SOC on sexual minorities’ mental health, as Huebner and Davis (2005) had found that more SOC in the workplace could predict fewer psychological problems. The positive association between SOC and self-criticism may derive from that sexual minorities sometimes claim themselves as “heterosexual.” Such denial about sexual orientation may result in self-criticism (Bagley & Tremblay, 1997). Furthermore, we attempted to find out the combined effect of SOC by comparing the indirect effect sizes. The results showed that the effect sizes of the “SMS – SOC – self-criticism – NSSI” path and the “SMS – SOC – self-criticism – depression – NSSI” path were both significantly greater than that of the “SMS – SOC – NSSI” path. This may suggest that although SOC may be an effective way to escape SMS, the internal stress of SOC may have counterproductive negative effects on sexual minorities (e.g., lead to more self-criticism and depression) and finally increase the risks of engaging in NSSI.

Last but not least, one of our important findings was the serial mediation model effect, such that SMS was indirectly related to NSSI through SOC, self-criticism, and depression in Chinese sexual minorities. The finding is supported by the Minority Stress Theory (Meyer, 2003) and the psychological mediation framework (Hatzenbuehler, 2009). Specifically, Chinese society places high values on collective norms. Thus, to conform to the majority, Chinese sexual minorities are more likely to use SOC for avoiding SMS (Li et al., 2021). However, SOC would make them internally stressful, and then increase the risk of NSSI by aggravating their self-criticism and depression (Feinstein et al., 2020; Williams et al., 2017). For example, sexual minorities with SOC may be vigilant about whether their sexual minority identities are disclosed. This vigilance may put them in ego depletion (Hatzenbuehler, 2009) and further lead to cognitive biases, such as negatively evaluating themselves (i.e., self-criticism) and underestimating their abilities (i.e., a typical symptom of depression; Fischer et al., 2007). Especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, social distancing measures and stay-at-home orders may cause sexual minorities with high SOC to receive less social support, further leading to self-criticism, and depression (Suen et al., 2020). Thus, they may engage in NSSI to cease their negative thoughts and emotions (Nock, 2010).

When we explored the serial mediation model, however, we found that the indirect effect of SOC and depression in the relationship between SMS and NSSI was not significant. It might be largely attributed to the nonsignificant direct pathway from SOC to depression. To date, the relationship between SOC and depression shows mixed results — from positive to negative to null (Pachankis et al., 2020). In addition to possible reasons such as the different assessment methods used in previous studies (Pachankis et al., 2020), it is also possible that there are complex negative psychological processes mediating the relationship between SOC and depression (Li et al., 2021), such as self-criticism in the current study. Therefore, future studies can further explore the relationship between SOC and depression.

Limitation

Several limitations of the current study should be acknowledged. First, the current study used a cross-sectional design, which was unable to discover the temporal or causal relationship among study variables (Maxwell et al., 2011). Future studies could use longitudinal or quasi-experimental designs to partly address this limitation. Second, all variables we assessed were collected by participants’ self-report, which may influence the results due to recall bias or social desirability. Future research is encouraged to use multiple-method assessment. Third, we used non-probability-based sampling, which could affect the assessment of study variables. For example, non-probability sampling may cause us to recruit fewer participants with high SOC who would be more cautious in deciding whether to participate in the survey. To overcome the methodological challenge, future studies are encouraged to adopt probability-based sampling. Fourth, this study focused on the mechanism of NSSI in sexual minorities, but did not explore how to alleviate the occurrence of NSSI. In future studies, the protective factors for preventing NSSI in sexual minorities can be further explored. Finally, the participants in this study were all recruited from China, a typically collectivistic country. Research findings need to be generalized with consideration of cultural differences.

Implications

This study has both theoretical and practical implications. Regarding theoretical implications, to our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the potential mechanism of NSSI from the integrated pathway of “external stress - proximal stress - cognition - emotion - maladaptive behavior,” especially in sexual minorities. The findings show the importance of minority stresses (SMS and SOC) and negative psychological processes (self-criticism and depression) on the engagement in NSSI, which could help researchers gain more understanding of the mechanisms of NSSI in sexual minorities.

Regarding practical implications, the positive relation from SMS to NSSI among sexual minorities suggests the urgency of de-stigmatizing sexual minorities. Policy and law makers should dedicate themselves to enhancing social acceptance of sexual minorities, such as repealing bills that could cause SMS (e.g., the “Don’t Say Gay Bill” in the USA) and greatly popularizing the knowledge about sexual orientation. Meanwhile, policy and law makers are encouraged to protect the fundamental rights of sexual minorities, such as developing more inclusive school policies for sexual minority adolescents and more supportive workplace policies for sexual minority adults. Besides, our findings may also help clinicians better understand sexual minorities’ engagement in NSSI and then adopt more effective treatments. For example, since SMS and SOC are difficult to overcome in a short-term period, clinicians could adopt Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to reduce sexual minorities’ self-criticism and depression to effectively prevent or treat NSSI (Craig et al., 2013; Satterfield & Crabb, 2010).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Research Center for Crisis Intervention and Psychological Service of Guangdong Province, South China Normal University, and the base of psychological services and counseling for “Happiness” in Guangzhou. In addition, the authors are grateful to Beijing LGBT Center for the support and help of the data collection.

Author Contribution

Danrui Chen conceived of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and drafted the manuscript; Jiefeng Ying participated in the design of the study, and helped revise the manuscript; Xinglin Zhou, Huijiao Wu, and Yunhong Shen managed the literature searches and helped revise the manuscript; Jianing You participated in the design of the study and helped revise the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 31771228), the National Social Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 19ZDA360), and the Special Funds for the Cultivation of Guangdong College Students’ Scientific and Technological Innovation (“Climbing Program” Special Funds) (Grant No. pdjh2021b0145). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

All the participants provided the informed consent.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Argyriou A, Goldsmith KA, Rimes KA. Mediators of the disparities in depression between sexual minority and heterosexual individuals: A systematic review. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2021;50:1–35. doi: 10.1007/s10508-020-01862-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aruta JJBR, Antazo BG, Paceño JL. Self-stigma is associated with depression and anxiety in a collectivistic context: The adaptive cultural function of self-criticism. Journal of Psychology. 2021;155(2):238–256. doi: 10.1080/00223980.2021.1876620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley C, Tremblay P. Suicidal behaviors in homosexual and bisexual males. Crisis. 1997;18(1):24–34. doi: 10.1027/0227-5910.18.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A, Adams NE, Beyer J. Cognitive processes mediating behavioral change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1977;35(3):125–139. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.35.3.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrocas AL, Giletta M, Hankin BL, Prinstein MJ, Abela JRZ. Nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescence: Longitudinal course, trajectories, and intrapersonal predictors. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2015;43(2):369–380. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batejan KL, Jarvi SM, Swenson LP. Sexual orientation and non-suicidal self-injury: A meta-analytic review. Archives of Suicide Research. 2015;19(2):131–150. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2014.957450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociological Methods and Research. 1992;21:230–258. doi: 10.1177/0049124192021002005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buelens, T., Costantini, G., Luyckx, K., & Claes, L. (2020). Comorbidity between non-suicidal self-injury disorder and borderline personality disorder in adolescents: A graphical network approach. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11(11). 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.580922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Busby DR, Horwitz AG, Zheng K, Eisenberg D, Harper GW, Albucher RC, King CA. Suicide risk among gender and sexual minority college students: The roles of victimization, discrimination, connectedness, and identity affirmation. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 2020;121:182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2019.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KKS, Leung DCK. The impact of mindfulness on self-stigma and affective symptoms among sexual minorities. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;286(1):213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrapani V, Vijin PP, Logie CH, Newman PA, Shunmugam M, Sivasubramanian M, Samuel M. Understanding how sexual and gender minority stigmas influence depression among trans women and men who have sex with men in India. LGBT Health. 2017;4(3):217–226. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2016.0082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen JM, Blasey C, Barr Taylor C, Weiss BJ, Newman MG. Anxiety and related disorders and concealment in sexual minority young adults. Behavior Therapy. 2016;47(1):91–101. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig SL, Austin A, Alessi E. Gay affirmative cognitive behavioral therapy for sexual minority youth: A clinical adaptation. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2013;41(3):258–266. doi: 10.1007/s10615-012-0427-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Decamp W, Bakken NW. Self-injury, suicide ideation, and sexual orientation: Differences in causes and correlates among high school students. Journal of Injury and Violence Research. 2016;8(1):15–24. doi: 10.5249/jivr.v8i1.545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding C, Chen X, Wang W, Yu B, Yang H, Li X, Deng S, Yan H, Li S. Sexual minority stigma, sexual orientation concealment, social support and depressive symptoms among men who have sex with men in China: A moderated mediation modeling analysis. AIDS and Behavior. 2020;24(1):8–17. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02713-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge B, Herbenick D, Friedman MR, Schick V, Fu TC, Bostwick W, Bartelt E, Muñoz-Laboy M, Pletta D, Reece M, Sandfort TGM. Attitudes toward bisexual men and women among a nationally representative probability sample of adults in the United States. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):1–19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein BA, Xavier Hall CD, Dyar C, Davila J. Motivations for sexual identity concealment and their associations with mental health among bisexual, pansexual, queer, and fluid (Bi+) individuals. Journal of Bisexuality. 2020;20(3):324–341. doi: 10.1080/15299716.2020.1743402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer P, Greitemeyer T, Frey D. Ego depletion and positive illusions: Does the construction of positivity require regulatory resources? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33(9):1306–1321. doi: 10.1177/0146167207303025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Q, Guo J, Wu H, Huang J, Wu N, You J. Different profiles with multiple risk factors of nonsuicidal self-injury and their transitions during adolescence: A person-centered analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;295(6):63–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert P, Clarke M, Hempel S, Miles JNV, Irons C. Criticizing and reassuring oneself: An exploration of forms, styles and reasons in female students. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2004;43(1):31–50. doi: 10.1348/014466504772812959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Touchstone; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Golam K, Solomon T, Jordi H, Rehan S. Handling incomplete and missing data in water network database using imputation methods. Sustainable and Resilient Infrastructure. 2020;5(6):365–377. doi: 10.1080/23789689.2019.1600960. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz KL. Measurement of deliberate self-harm: Preliminary data on the deliberate self-harm inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23(4):253–263. doi: 10.1023/a:1012779403943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goh JX, Kort DN, Thurston AM, Benson LR, Kaiser CR. Does concealing a sexual minority identity prevent exposure to prejudice? Social Psychological and Personality Science. 2019;10(8):1056–1064. doi: 10.1177/1948550619829065. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gong T, Ren Y, Wu J, Jiang Y, Hu W, You J. The associations among self-criticism, hopelessness, rumination, and NSSI in adolescents: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Adolescence. 2019;72(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML. How does sexual minority stigma “get under the skin”? A Psychological Mediation Framework. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135(5):707–730. doi: 10.1037/a0016441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick ES, Martin AD. Developmental issues and their resolution for gay and lesbian adolescents. Journal of Homosexuality. 1987;14(1–2):25–43. doi: 10.1300/J082v14n01_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Franklin JC. Why do people hurt themselves? A new conceptual model of nonsuicidal self-injury. Clinical Psychological Science. 2018;6(3):428–451. doi: 10.1177/2167702617745641. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hottes TS, Bogaert L, Rhodes AE, Brennan DJ, Gesink D. Lifetime prevalence of suicide attempts among sexual minority adults by study sampling strategies: A systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106(5):e1–e12. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner DM, Davis MC. Gay and bisexual men who disclose their sexual orientations in the workplace have higher workday levels of salivary cortisol and negative affect. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30(3):260–267. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3003_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Jackman KB, Dolezal C, Levin B, Honig JC, Bockting WO. Stigma, gender dysphoria, and nonsuicidal self-injury in a community sample of transgender individuals. Psychiatry Research. 2018;269:602–609. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joeng JR, Turner SL. Mediators between self-criticism and depression: Fear of compassion, self-compassion, and importance to others. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2015;62(3):453–463. doi: 10.1037/cou0000071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Júlia H, Martin K, Gilbert P, Troop NA, Kupeli N. Multiple group IRT measurement invariance analysis of the forms of self-criticising/attacking and self-reassuring scale in thirteen international samples. Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. 2019;37:411–444. doi: 10.1007/s10942-019-00319-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. The Guilford Press; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lear Mary K., Luoma Jason B., Chwyl Christina. The influence of self-criticism and relationship closeness on peer-reported relationship need satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences. 2020;163:110087. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2020.110087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leboeuf I, Mahanga J, Rusinek S, Delamillieure P, Gheysen F, Andreotti E, Antoine P. Validation of the French version of the Forms of Self-Criticizing/Attacking and Self-Reassuring Scale. Stress and Health: Journal of the International Society for the Investigation of Stress. 2020;36(1):31–36. doi: 10.1002/smi.2909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Wang Y, Xing J. Two sources of autonomy support and depressive symptoms among Chinese gay men: The sequential mediating effect of internalized homonegativity and rumination. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;280:373–380. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M, You J, Wu YW, Jiang Y. Depression mediates the relationship between distress tolerance and nonsuicidal self-injury among adolescents: One-year follow-up. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2018;48(5):589–600. doi: 10.1111/sltb.12382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Chui H, Chung MC. The moderating effect of filial piety on the relationship between perceived public stigma and internalized homophobia: A national survey of the Chinese LGB population. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2021;18(1):160–169. doi: 10.1007/s13178-020-00446-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R. T., Sheehan, A. E., Walsh, R. F. L., Sanzari, C. M., Cheek, S. M., & Hernandez, E. M. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 74(7). 10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995;33(3):335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Cloutier PF, Levesque C, Bureau JF, Lafontaine MF, Nixon MK. Psychometric properties of the functions and addictive features scales of the Ottawa Self-Injury Inventory: A preliminary investigation using a university sample. Psychological Assessment. 2013;25(3):1013–1018. doi: 10.1037/a0032575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell SE, Cole DA, Mitchell MA. Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal mediation: Partial and complete mediation under an autoregressive model. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2011;46(5):816–841. doi: 10.1080/00273171.2011.606716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, I. H., & Wilson, P. A. (2009). Sampling lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 23–31. 10.1037/a0014587

- Mongrain M, Leather F. Immature dependence and self-criticism predict the recurrence of major depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2006;62(6):705–713. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monto MA, McRee N, Deryck FS. Nonsuicidal self-injury among a representative sample of US adolescents, 2015. American Journal of Public Health. 2018;108(8):1042–1048. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen, L. K., & Muthen, B. (2017). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables, user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Nappa MR, Bartolo MG, Pistella J, Petrocchi N, Costabile A, Baiocco R. “I do not like being me”: The impact of self-hate on increased risky sexual behavior in sexual minority people. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00590-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Neilands TB, Steward WT, Choi KH. Assessment of stigma towards homosexuality in China: A study of men who have sex with men. Archives of Sexual Behavior. 2008;37(5):838–844. doi: 10.1007/s10508-007-9305-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Why do people hurt themselves?: New insights into the nature and functions of self-injury. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2009;18(2):78–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01613.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nock MK. Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2010;6:339–363. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nystedt T, Rosvall M, Lindström M. Sexual orientation, suicide ideation and suicide attempt: A population-based study. Psychiatry Research. 2019;275:359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2019.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, R. C., & Kirtley, O. J. (2018). The integrated motivational-volitional model of suicidal behavior. Crisis, 373(1754). 10.1098/rstb.2017.0268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- O’Connor RC, Rasmussen S, Hawton K. Distinguishing adolescents who think about self-harm from those who engage in self-harm. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2012;200(4):330–335. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.097808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshana A, Klimek P, Blashill AJ. Minority stress and body dysmorphic disorder symptoms among sexual minority adolescents and adult men. Body Image. 2020;34:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE, Jackson SD, Fetzner BK, Bränström R. Supplemental material for sexual orientation concealment and mental health: A conceptual and meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2020;146(10):831–871. doi: 10.1037/bul0000271.supp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plöderl, M., & Tremblay, P. (2015). Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. International Review of Psychiatry, 27(5), 367–385. 10.3109/09540261.2015.1083949 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Satterfield JM, Crabb R. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression in an older gay man: A clinical case study. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2010;17(1):45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimshaw EW, Siegel K, Downing MJ, Parsons JT. Disclosure and concealment of sexual orientation and the mental health of non-gay-identified, behaviorally bisexual men. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81(1):141–153. doi: 10.1037/a0031272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selby EA, Anestis MD, Joiner TE. Understanding the relationship between emotional and behavioral dysregulation: Emotional cascades. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2008;46(5):593–611. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DM, Wang SB, Carter ML, Fox KR, Hooley JM. Longitudinal predictors of self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in sexual and gender minority adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2020;129(1):114–121. doi: 10.1037/abn0000483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staples JM, Neilson EC, Bryan AEB, George WH. The role of distal minority stress and internalized transnegativity in suicidal ideation and nonsuicidal self-injury among transgender adults. Journal of Sex Research. 2018;55(4–5):591–603. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1393651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Zheng L. Sexual orientation and gender differences in sexual minority identity in China: Extension to asexuality. Current Psychology. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s12144-021-01354-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suen YT, Chan RCH, Wong EMY. Effects of general and sexual minority-specific COVID-19-related stressors on the mental health of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in Hong Kong. Psychiatry Research. 2020;292:113365. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Hoyt WT, Tarantino N, Pachankis JE, Whiteley L, Operario D, Brown LK. Cultural context matters: Testing the minority stress model among Chinese sexual minority men. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2021;68(5):526–537. doi: 10.1037/cou0000535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taliaferro LA, Muehlenkamp JJ. Nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidality among sexual minority youth: Risk factors and protective connectedness factors. Academic Pediatrics. 2017;17(7):715–722. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatnell R, Hasking P, Newman L. Multiple mediation modelling exploring relationships between specific aspects of attachment, emotion regulation, and non-suicidal self-injury. Australian Journal of Psychology. 2018;70(1):48–56. doi: 10.1111/ajpy.12166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno K. Same-sex experience and mental health during the transition between adolescence and young adulthood. Sociological Quarterly. 2010;51(3):484–510. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2010.01179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Li M, Hu N, Zhu E, Hu J, Liu X, Yin J. K-means clustering with incomplete data. IEEE Access. 2019;7:69162–69171. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2910287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kei C, Qiang L, Guangyu W. The impact of sexual minority stigma on depression: The roles of resilience and family support. Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s13178-021-00558-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Williams SL, Mann AK, Fredrick EG. Proximal minority stress, psychosocial resources, and health in sexual minorities. Journal of Social Issues. 2017;73(3):529–544. doi: 10.1111/josi.12230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- You J, Lin M. Predicting suicide attempts by time-varying frequency of nonsuicidal self-injury among Chinese community adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2015;83(3):524–533. doi: 10.1037/a0039055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.