Abstract

Bacillus thuringiensis protein δ-endotoxins are toxic to a variety of different insect species. Larvicidal potency depends on the completion of a number of steps in the mode of action of the toxin. Here, we investigated the role of proteolytic processing in determining the potency of the B. thuringiensis Cry1Ac δ-endotoxin towards Pieris brassicae (family: Pieridae) and Mamestra brassicae (family: Noctuidae). In bioassays, Cry1Ac was over 2,000 times more active against P. brassicae than against M. brassicae larvae. Using gut juice purified from both insects, we processed Cry1Ac to soluble forms that had the same N terminus and the same apparent molecular weight. However, extended proteolysis of Cry1Ac in vitro with proteases from both insects resulted in the formation of an insoluble aggregate. With proteases from P. brassicae, the Cry1Ac-susceptible insect, Cry1Ac was processed to an insoluble product with a molecular mass of ∼56 kDa, whereas proteases from M. brassicae, the non-susceptible insect, generated products with molecular masses of ∼58, ∼40, and ∼20 kDa. N-terminal sequencing of the insoluble products revealed that both insects cleaved Cry1Ac within domain I, but M. brassicae proteases also cleaved the toxin at Arg423 in domain II. A similar pattern of processing was observed in vivo. When Arg423 was replaced with Gln or Ser, the resulting mutant toxins resisted degradation by M. brassicae proteases. However, this mutation had little effect on toxicity to M. brassicae. Differential processing of membrane-bound Cry1Ac was also observed in qualitative binding experiments performed with brush border membrane vesicles from the two insects and in midguts isolated from toxin-treated insects.

The gram-positive, endospore-forming bacterium Bacillus thuringiensis produces parasporal crystalline inclusions that contain polypeptides (δ-endotoxins) that are toxic to a variety of insect species (16). Upon ingestion by an insect larva, these inclusions are solubilized in the alkaline environment of the midgut and are activated by midgut proteases (23, 40). The activated toxins then pass through the peritrophic matrix and subsequently bind to a highly specific receptor(s) on the midgut brush border membrane (14, 15, 41). Perhaps following a conformational change and/or oligomerization, the toxin induces the formation of a lytic pore in the midgut epithelial membrane that results in cell lysis, cessation of feeding, and death of the larva (27).

The ∼130-kDa Cry1 δ-endotoxins undergo extensive proteolysis at both their C and N termini to produce a mature toxic moiety that has a molecular mass of approximately 60 kDa. This relatively protease-resistant toxic core is derived from the N-terminal half of the protoxin by removal of 500 to 600 amino acid residues from the C terminus and the first 27 to 29 N-terminal residues (2, 4, 7, 17, 30, 31, 36, 43). Activated Cry1Ac is generated by cleavages at R28 and K623 in the protoxin (4). It has been postulated that the C-terminal region that is lost through activation directs assembly of the crystal and facilitates efficient solubilization at alkaline pH values (42). It is interesting to note that Cry1Ac activation proceeds through seven specific cleavages, starting from the C terminus and perhaps involving a sequence of conformational changes, to remove the C-terminal half of the protoxin (8). The resulting 10- to 35-kDa protoxin-derived fragments are themselves rapidly proteolysed into peptides, and they apparently play no further role in toxicity. Whether this mechanism of activation is true for all Cry1 δ-endotoxins has not been elucidated to date.

Correct activation of a B. thuringiensis δ-endotoxin is likely to be a prerequisite for toxicity, and insufficient processing or overdigestion of a toxin may render it inactive. The battery of midgut proteases that an insect possesses is therefore likely to be a major determinant of toxin potency. The midgut lumina of lepidopteran insect larvae have been shown to contain a variety of alkaline proteases, mainly members of the serine protease class, that exhibit predominantly trypsinlike and chymotrypsinlike protease activities (9, 19, 20, 28). Such midgut proteases are likely to be responsible for δ-endotoxin activation.

A number of reports have suggested that δ-endotoxin proteolysis is a major determinant of toxicity. It has been demonstrated that a strain of Plodia interpunctella (Indian meal moth) resistant to the δ-endotoxins of B. thuringiensis subsp. entomocidus HD-198 exhibited a lower protoxin activation rate than susceptible insects exhibited due to a decrease in the total proteolytic activity of the gut extract (32, 33). Ingaki et al. (18) found the reverse to be true for Spodoptera litura processing of B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki HD-1. They reported that complete degradation of the toxin by proteases derived from the nonsusceptible organism S. litura was the likely cause of the lack of potency. Similarly, Keller et al. (20) suggested that reduced sensitivity of fifth-instar larvae of Spodoptera littoralis to Cry1C could be attributed to increased degradation of the toxin in the less susceptible larvae. Ogiwara et al. (31) compared the sites of proteolytic cleavage of the δ-endotoxins of B. thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki HD-1 and HD-73. They showed that the sites of N-terminal proteolysis depended on the insect that the proteases were derived from and that the difference may have accounted for the differences in potency. Bai et al. (3) showed that the protease levels in regurgitated gut juice from Pieris brassicae were higher than those found in gut juice from Mamestra brassicae and S. littoralis, and they suggested that this may account for the lack of susceptibility of the latter two insects to B. thuringiensis subsp. thuringiensis. They also showed that P. brassicae had a higher proportion of trypsinlike and chymotrypsinlike proteases than the other two insect species. Haider et al. (13) clearly demonstrated that differential proteolysis could determine the specificity of a toxin. Activation of the Cry1Ab protoxin from B. thuringiensis subsp. aizawai with lepidopteran gut enzymes yielded a 55-kDa protein that was toxic only to Lepidoptera. Further treatment of this 55-kDa polypeptide, or intact protoxin, with dipteran gut proteases resulted in production of a 53-kDa Diptera-specific toxic core.

In this study, we investigated the role of proteolysis in determining the potency of Cry1Ac towards P. brassicae (large white butterfly) and M. brassicae (cabbage moth) larvae. Höfte and Whiteley (16) demonstrated that Cry1Ac was highly active towards P. brassicae, whereas it was relatively inactive against M. brassicae. Here, we demonstrate that differences in the way that Cry1Ac is proteolysed by proteases from the two insects may contribute to the large difference in toxin potency observed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and plasmids.

Escherichia coli TG1 (35) was used for all standard molecular biology techniques. Plasmid pMSV.Cry1Ac (37) was used for expression of Cry1Ac δ-endotoxin crystals in the acrystalliferous strain B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis IPS-78/11 (5).

Site-directed mutagenesis.

Site-directed mutagenesis was performed as described by Smedley and Ellar (37) by using the Altered-Sites in vitro mutagenesis system (Promega) and plasmid pMSV.Cry1Ac as a template. Mutagenic oligonucleotides were synthesized by the Protein and Nucleic Acid Chemistry Facility, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom. Mutant plasmids were transformed into B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis IPS-78/11 by electroporation (5).

Purification of δ-endotoxin inclusions.

δ-Endotoxin inclusions were purified from sporulated cultures of B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis IPS-78/11 containing the desired plasmid as described previously (39). The yield of purified crystals was determined by the method described by Lowry et al. (26) by using bovine serum albumin fraction V (BSA) as a standard.

Toxicity assays.

P. brassicae larvae were reared from eggs that were kindly provided by Horticulture Research International, Wellesbourne, Warwickshire, United Kingdom. M. brassicae larvae were reared from eggs that were obtained from T. Carty, Institute for Virology and Environmental Microbiology, National Environment Research Council, Oxford, United Kingdom. A toxin crystal suspension or solubilized toxin was incorporated into molten artificial diet (50°C) at a range of concentrations. After the diet had set and dried, 20 third-instar larvae per concentration or 40 neonate larvae per concentration were placed on the diet, and mortality was determined after 6 days of incubation at 25°C under a light cycle consisting of 16 h of light and 8 h of darkness. The concentrations of toxin at which 50% of the larvae were killed (LC50s) were determined by Probit analysis (11). To determine Cry1Ac toxicity, bioassays were repeated three times, and an average LC50, with associated 95% confidence intervals, was calculated. In cases where mortality was low, the LC50 could not be determined.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting.

Proteins were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) by using a modification of the method of Laemmli and Favre (22), as described by Thomas and Ellar (39). Proteins were transferred from the gel to nitrocellulose with a Bio-Rad semidry blot apparatus by using a blot buffer containing 39 mM glycine, 48 mM Tris (pH 9.0), 0.0375% (wt/vol) SDS, and 10% (vol/vol) methanol. Toxin was detected by the method described by Knowles et al. (21) or with an ECL Plus chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham).

In vitro toxin processing.

To prepare gut juice, fifth-instar larvae were chilled on ice for 10 min before they were dissected. The peritrophic membrane containing the food bolus was isolated and centrifuged at 30,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. The supernatant was removed and recentrifuged for 20 min at the same speed, and the resulting supernatant was removed and filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size membrane. Cry1Ac protoxin inclusions were solubilized in 50 mM Na2CO3–10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)(pH 10.0) for 30 min at 37°C. A Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad) was performed with the solubilized toxin, and the concentration was subsequently adjusted to 1 mg/ml. Gut juice was added to the solubilized toxin at a concentration of 5% (vol/vol), and a time course at 37°C was followed. Samples (50 μl) were removed at 10 min and 2, 8, and 24 h and separated into soluble and insoluble fractions by centrifugation at 30,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min; then each pellet was washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The extent of toxin proteolysis was determined by SDS–13% PAGE as described above. Protease cleavage sites were determined by N-terminal sequencing of the δ-endotoxin polypeptides following SDS–13% PAGE and transfer of proteins onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. This was done by the Protein and Nucleic Acid Chemistry Facility, Department of Biochemistry, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom.

Qualitative binding assay.

The procedure used for the qualitative binding assay was essentially that of Knowles et al. (21). Cry1Ac was activated with 1% (vol/vol) purified gut juice (see above) for 1 h at 37°C, and this was followed by centrifugation at 30,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min to remove insoluble material. One hundred micrograms of brush border membrane vesicles (BBMV) (44) was incubated with 10 μg of activated toxin in 100 μl (final volume) of PBS containing 1 mg of BSA per ml for 60 min at room temperature without shaking. The mixture was centrifuged at 30,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min, and the resultant BBMV pellet was washed twice with cold PBS containing 1 mg of BSA per ml. Samples of the supernatant containing unbound toxin and the pellet containing toxin bound to membrane were separated by SDS–13% PAGE, followed by immunoblotting as described above.

In vivo toxin processing.

Newly molted fifth-instar larvae of M. brassicae and P. brassicae were starved for 12 h. A 10-mg/ml Cry1Ac toxin crystal suspension (or 10 mg of BSA per ml as a control) was made up in a 25 mM sucrose solution containing approximately 10 mg of cabbage powder per ml. Fifteen microliters of the toxin suspension was fed to the larvae by placing a drop in front of an advancing larva with a micropipette. After the toxin suspension had been completely imbibed, the larvae were incubated at 22°C for either 30 min or 3 h; 10 larvae were used for each treatment. After this the larvae were dissected and separated into three fractions (midgut, insoluble fraction of the food bolus, and soluble fraction of the food bolus) as follows (all subsequent fractionation steps were performed in a cold room at 4°C). To prepare the midgut fraction, midguts were isolated from toxin-treated and BSA-fed larvae and then washed by vortexing them in 500 μl of ice-cold PBS containing an inhibitor cocktail consisting of 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μM leupeptin, 10 μM antipain, 20 μg of (4-amidophenyl)-methanesulfonyl fluoride per ml, and 135 μM l-1-chloro-3-(4-tosylamide)-7-amino-2-heptanone. The midguts were then homogenized in 100 μl of fresh PBS containing the inhibitor cocktail (PBS/inhibitors) and subsequently washed three times by repeated resuspension of the pellet in PBS/inhibitors and centrifugation at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min in a minifuge. The final pellet was resuspended in 100 μl of PBS/inhibitors, and protein was precipitated with 25% trichloroacetic acid (TCA) at −20°C for 2 h, which was followed by centrifugation at 30,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min. The pellet was washed twice with ice-cold acetone, and then the pellet was air dried. The precipitate was then boiled for 5 min in 80 μl of 1× SDS-PAGE loading buffer and separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting performed as described above. To prepare the insoluble fraction of the food bolus, after dissection peritrophic membranes containing the food bolus were removed from the gut, and a 10× PBS/inhibitors solution was added to give a 1× concentration. The sample was then centrifuged at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min in a minifuge, and the supernatant was removed (see below). The pellet was then homogenized in 100 μl of ice-cold PBS/inhibitors and subsequently washed three times by repeated centrifugation at 15,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min in a minicentrifuge and resuspension in PBS/inhibitors. The final pellet was then TCA precipitated and processed in the same way that the midgut membrane sample was processed (see above). To prepare the soluble fraction of the food bolus, after centrifugation of the peritrophic membranes containing the food bolus as described above, the supernatant was removed and centrifuged again at 30,000 × g at 4°C for 15 min in a minifuge. The supernatant was removed, TCA precipitated, and processed in the same way that the midgut membrane fraction was processed (see above).

RESULTS

Toxicity of Cry1Ac against P. brassicae and M. brassicae larvae.

Höfte and Whiteley (16) reported the activities of a number of δ-endotoxins towards P. brassicae and M. brassicae, which demonstrated that Cry1Ac was the most potent toxin against P. brassicae whereas it was relatively inactive against M. brassicae. However, the LC50s for the two insect species were expressed in different units, making direct comparisons difficult. It was therefore essential to obtain bioassay data produced under standardized conditions. Toxicity assays were performed with purified Cry1Ac δ-endotoxin inclusions and third-instar P. brassicae and M. brassicae larvae (LC50s are shown in Table 1).

TABLE 1.

LC50s of Cry1Ac for third instar-larvae of P. brassicae and M. brassicae

| Insect | LC50 (μg of toxin/g of diet) | 95% confidence limits |

|---|---|---|

| P. brassicae | 0.0414 | 0.0205–0.0836 |

| M. brassicae | >100 |

As shown in Table 1, Cry1Ac was at least 2,000 times more toxic towards P. brassicae than towards M. brassicae. Even at a concentration of 100 μg of toxin/g of diet, Cry1Ac was unable to produce 50% mortality in the M. brassicae larvae. The lack of potency of Cry1Ac towards M. brassicae may be due to the inability of the toxin to undergo one or more of the essential steps in its mode of action. Therefore, studies were performed to determine whether toxin processing by midgut proteases from the two insects differed and whether this contributed to the large difference in Cry1Ac potency.

In vitro toxin processing.

Studies of Cry1Ac activation with gut juice derived from P. brassicae and M. brassicae were performed. Soluble and insoluble fractions were isolated and separated by SDS–13% PAGE, which was followed by staining with Coomassie brilliant blue (Fig. 1). It should be noted that on SDS-PAGE gels with the molecular weight markers used, activated Cry1Ac appeared to migrate at a molecular weight lower than that estimated from its amino acid sequence. This anomaly may have been due to aberrant migration of the activated toxin and/or the 47.5-kDa protein marker. For this reason all estimates of the molecular weights of all toxin products were based on data for the soluble activated form of Cry1Ac (bands 1 and 5) having a molecular mass of 60 kDa.

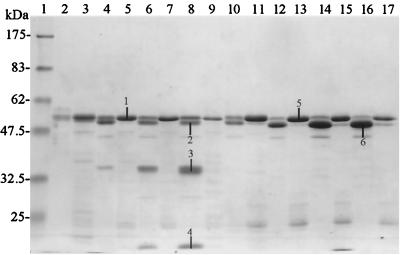

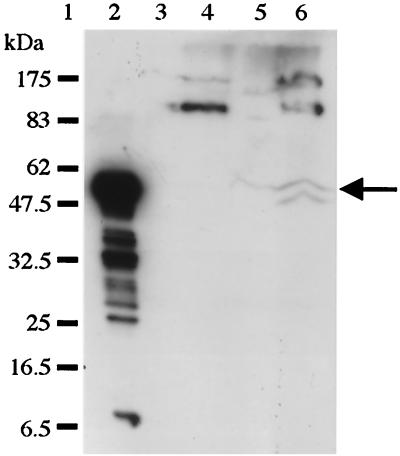

FIG. 1.

Proteolytic activation of Cry1Ac with M. brassicae and P. brassicae gut juice. Solubilized δ-endotoxin inclusions were activated with 5% (vol/vol) gut juice from M. brassicae (lanes 2 to 9) or P. brassicae (lanes 10 to 17). Ten micrograms of toxin was loaded onto a SDS–13% PAGE gel, and electrophoresis was followed by Coomassie brilliant blue staining. Lanes 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, and 16, insoluble toxin fraction; lanes 3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, and 17, soluble toxin fraction. Lane 1 contained molecular weight markers. Toxin was activated for 10 min (lanes 2, 3, 10, and 11), 2 h (lanes 4, 5, 12, and 13), 8 h (lanes 6, 7, 14, and 15), or 24 h (lanes 8, 9, 16, and 17).

As shown in Fig. 1, after 10 min of activation, most of the Cry1Ac was present as a single product having a molecular mass of ∼60 kDa with proteases from M. brassicae and P. brassicae (lanes 3 and 11). N-terminal sequencing of this soluble product (bands 1 and 5) indicated that proteolysis occurred at Arg28 in both cases. As time progressed, more and more of the toxin became insoluble, and after 24 h of incubation the majority of the toxin was present as an insoluble form (lanes 8 and 16). Strikingly, the aggregated material appeared to represent a proteolysed form of the toxin. When protease extract from M. brassicae, the nonsusceptible insect, was used, the insoluble form of the toxin was present as products having molecular masses of ∼60, ∼58, ∼40, and ∼20 kDa (bands 1 to 4, respectively). The N-terminal sequences of these products are shown in Table 2. When protease extract from P. brassicae, the highly susceptible insect, was used, the insoluble form of the toxin was present predominantly as a ∼56-kDa product; a small amount of a ∼60-kDa product was also evident (bands 5 and 6). The N-terminal sequences of these products are also shown in Table 2. Generation of substantial amounts of lower-molecular-weight breakdown products, as observed with M. brassicae proteases, was not observed with P. brassicae proteases.

TABLE 2.

N-terminal sequences of insoluble activated Cry1Ac products as determined with M. brassicae gut juice and P. brassicae gut juicea

| Band | Insect | Molecular mass (kDa) | N-terminal sequenceb | Position of cleavage site in Cry1Acc |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M. brassicae | 60d | 29IETGY | Before α1 |

| 34TPIDI | Before α1 | |||

| 2 | M. brassicae | 58 | 51VPGAG | Between α1 and α2a |

| 3 | M. brassicae | 40d | 51VPGAG | Between α1 and α2a |

| 57VLGLV | In α2a | |||

| 67IFGPS | Between α2a and α2b | |||

| 69GPSQW | Between α2a and α2b | |||

| 4 | M. brassicae | 20 | 424QGFSHRL | Between β9 and β10 |

| 5 | P. brassicae | 60 | 29IETGY | Before α1 |

| 6 | P. brassicae | 56d | 54AGFVL | In α2a |

| 61VDIIW | In α2a | |||

| 69GPSQW | Between α2a and α2b |

N-terminal sequences of Cry1Ac products were generated by using proteases from M. brassicae (bands 1 to 4) or P. brassicae (bands 5 and 6) (see Fig. 1).

The superscript number indicates the N-terminal amino acid in the Cry1Ac sequence.

Secondary-structure prediction based on the three-dimensional structure of Cry1Aa (12).

A mixed amino acid sequence was obtained.

In P. brassicae, the Cry1Ac-susceptible insect, processing occurred at residues Gly53, Leu60, and Phe68, which produced the insoluble ∼56-kDa product (mixed sequence). By contrast, in M. brassicae, the Cry1Ac-resistant species, processing at Phe50 yielded the ∼58-kDa form of the toxin and additional cleavages at Phe56, Gly66, Phe68, and Arg423 produced the insoluble ∼40- and ∼20-kDa forms. M. brassicae proteases were unable to generate a ∼56-kDa form of Cry1Ac. The high proportion of phenylalanine (F) residues that were cleaved by proteases from both insects suggest a possible role for chymotrypsinlike proteases, which exhibit specificity for aromatic and large hydrophobic residues in the P1 position of the protease cleavage site. However, Arg423 is likely to be a trypsinlike protease cleavage site. Although providing no information about processing at the C terminus of the toxin, these data clearly highlight differences in the patterns of Cry1Ac proteolysis in the two insect species.

Qualitative binding of Cry1Ac to BBMV from M. brassicae and P. brassicae.

A qualitative binding assay based on the method described by Knowles et al. (21) was used to investigate the interactions of Cry1Ac with BBMV prepared from M. brassicae and P. brassicae (44). As a control, the assay was also performed in the absence of BBMV. Soluble material containing unbound toxin and insoluble material containing toxin bound to BBMV were analyzed by SDS–13% PAGE, followed by immunoblotting (Fig. 2).

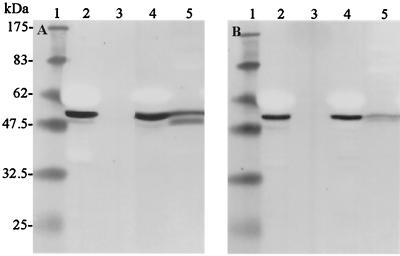

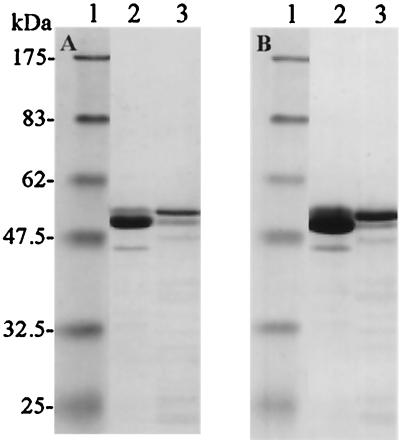

FIG. 2.

Binding of Cry1Ac to P. brassicae and M. brassicae BBMV. Qualitative binding was performed with activated toxin and BBMV from P. brassicae (A) and M. brassicae (B). Twenty microliters of either supernatant or pellet was analyzed by SDS–13% PAGE followed by immunoblotting with anti-Cry1Ac polyclonal antisera. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lanes 2 and 4, soluble material; lanes 3 and 5, insoluble material. Lanes 2 and 3 contained Cry1Ac incubated in the absence of BBMV, and lanes 4 and 5 contained Cry1Ac incubated with BBMV.

As shown in Fig. 2, Cry1Ac interacted with BBMV from both insect species. In the case of P. brassicae, toxin was associated as a distinct doublet with the higher-molecular-mass product comigrating with the free, soluble form of the toxin at 60 kDa and a lower-molecular-mass form having an apparent molecular mass of ∼56 kDa (Fig. 2A, lane 5). When M. brassicae BBMV were used, Cry1Ac was also associated with the membrane as a doublet (Fig. 2B, lane 5); however, this doublet differed from the form of the toxin bound to P. brassicae BBMV in two ways. First, the lower-molecular-mass product of the doublet had an apparent molecular mass of 58 to 59 kDa, compared to the ∼56-kDa product in P. brassicae. Second, whereas the two forms of the toxin doublet were present at similar levels in P. brassicae, in M. brassicae the higher-molecular-mass form represented approximately 90% of the bound toxin. The nicked products that were associated with the BBMV from the two insects were similar to the insoluble forms generated by extended activation of Cry1Ac with purified gut juice (Fig. 1).

Role of membrane-associated and midgut lumen proteases in Cry1Ac binding.

As described above, the forms of Cry1Ac bound to BBMV from P. brassicae and M. brassicae differed. The differences in proteolysis may contribute to the ability of the toxin to irreversibly associate with the membrane and consequently form lytic pores. To determine whether membrane-associated or gut juice-derived proteases were responsible for the specific proteolysis of membrane-bound toxin, qualitative binding was performed by using Cry1Ac activated with either 1% (vol/vol) P. brassicae gut juice or 1% (vol/vol) M. brassicae gut juice incubated with BBMV from both insects (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Role of membrane-associated and midgut lumen proteases in Cry1Ac binding. Cry1Ac activated with either P. brassicae or M. brassicae gut juice was mixed with BBMV from both insects, and qualitative binding assays were performed. Lane 1, prestained molecular weight markers; lanes 2, 4, 6, and 8, Cry1Ac remaining in the supernatant; lanes 3, 5, 7, and 9, Cry1Ac present in the pellet fraction. The following combinations of activated toxin and BBMV were used: lanes 2 and 3, M. brassicae-activated Cry1Ac and M. brassicae BBMV; lanes 4 and 5, P. brassicae-activated Cry1Ac and P. brassicae BBMV; lanes 6 and 7, P. brassicae-activated Cry1Ac and M. brassicae BBMV; and lanes 8 and 9, M. brassicae-activated Cry1Ac and P. brassicae BBMV.

As shown in Fig. 3, the ∼56-kDa, lower-molecular-mass form of the doublet was most obvious when BBMV from P. brassicae were used and was less dependent on the source of the gut juice protease.

In vivo toxin processing.

Most of the studies on toxin activation described previously were carried out in vitro by using purified gut juice preparations. Below we describe a novel experiment that was designed to monitor toxin activation and fate in vivo. The aim of the experiment was to determine whether the cleavage events that were observed in vitro (see above) also occur in the guts of the two insects. Three gut fractions were isolated from toxin-treated and BSA-fed insects and were analyzed by SDS–13% PAGE, followed by immunoblotting: a midgut membrane fraction, an insoluble fraction of the gut including the peritrophic membrane, and a soluble fraction of the gut (Fig. 4).

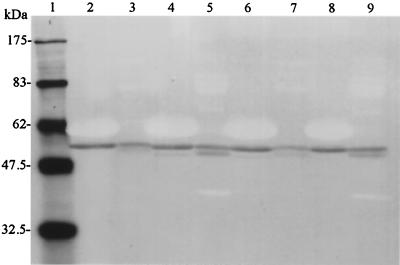

FIG. 4.

In vivo processing of Cry1Ac in P. brassicae and M. brassicae larvae. Immunoblotting of in vivo-activated Cry1Ac was performed. Lanes 1 to 9, samples derived from M. brassicae; lanes 10 to 18, samples derived from P. brassicae. Lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16 contained fractions isolated from insects fed BSA (control); lanes 2, 5, 8, 11, 14, and 17 contained fractions isolated from insects that were fed toxin and incubated for 30 min; and lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, and 18 contained fractions isolated from insects that were fed toxin and incubated for 3 h. Lanes 1 to 3 contained the M. brassicae midgut membrane fraction; lanes 4 to 6 contained the M. brassicae insoluble fraction from the insect gut; lanes 7 to 9 contained the M. brassicae soluble fraction from the insect gut; lanes 10 to 12 contained the P. brassicae midgut membrane fraction; lanes 13 to 15 contained the P. brassicae insoluble fraction from the insect gut; lanes 16 to 18 contained the P. brassicae soluble fraction from the insect gut; and lane 19 contained molecular weight markers.

Figure 4 illustrates the difference between Cry1Ac processing in M. brassicae and Cry1Ac processing in P. brassicae. As in the in vitro experiments described above, Cry1Ac was degraded in the gut of M. brassicae, the nonsusceptible insect, to a ∼40-kDa product (lanes 5 and 6). Interestingly, the ∼20-kDa fragment did not appear to react with anti-Cry1Ac antibody; this may have been due to a lack of epitope on this fragment. Such degradation of Cry1Ac was not evident in the gut of P. brassicae, the highly susceptible insect, confirming that the two insects have different spectra of midgut proteases. However, it is interesting to note that in both insects a considerable amount of Cry1Ac resided in the insoluble fraction, even after 30 min, supporting the hypothesis that both insects have a very fast solubilization and activation mechanism. The effective solubilization and rapid processing suggest that the guts of these insects are likely to exhibit high levels of protease function in a reducing environment (i.e., conditions that are required in vitro for effective solubilization and activation of δ-endotoxin).

The insoluble fraction in P. brassicae was predominantly a nicked product having a molecular mass of ∼56 kDa (Fig. 4, lanes 14 and 15); this product did not appear to be present in the gut of M. brassicae. Interestingly, the soluble forms of Cry1Ac also appeared to be different. In M. brassicae the toxin was present as a single band at ∼60 kDa and there were a number of lower-molecular-mass fragments at 20 to 25 kDa (lanes 8 and 9). In P. brassicae the soluble toxin was present as a doublet similar to that seen in the insoluble fraction, except that the ∼60-kDa higher-molecular-mass product predominated (lanes 17 and 18). It is possible that some ∼56-kDa insoluble material was not removed from the soluble extract during processing of the samples and thus accounted for the presence of the doublet in the P. brassicae sample.

Cry1Ac was not observed in the midgut membrane fraction of either insect (Fig. 4, lanes 2, 3, 11, and 12). This may have been due to the low sensitivity of the antibody detection system. To increase the sensitivity, an ECL Plus chemiluminescence detection kit (Amersham) was employed in an attempt to detect Cry1Ac associated with the membrane (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

ECL Plus detection of membrane-associated Cry1Ac. The membrane fraction from the in vivo processing experiment was detected by using an ECL Plus kit (Amersham) in combination with anti-Cry1Ac polyclonal antisera. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, in vitro-activated Cry1Ac (positive control); lane 3, M. brassicae midgut membrane isolated from BSA-fed insects (control); lane 4, P. brassicae midgut membrane isolated from BSA-fed insects; lane 5, M. brassicae midgut membrane isolated from Cry1Ac-fed insects after 3 h of incubation; lane 6, P. brassicae midgut membrane isolated from Cry1Ac-fed insects after 3 h of incubation. The arrow indicates the position of the membrane-associated toxin.

As shown in Fig. 5, the toxin appeared as a doublet in the P. brassicae membrane (lane 6) and as a single band in the M. brassicae membrane (lane 5, arrow). It is unlikely that this material was contaminating soluble or insoluble toxin due to the thorough washing steps that were used; however, this possibility cannot be ruled out. These membrane-associated forms of Cry1Ac were similar to those bound to BBMV in vitro, and the findings again suggest that proteolysis differs in the two insect species. Several higher-molecular-weight products were observed in the P. brassicae sample; however, these products were also evident in the control.

Construction and analysis of Arg423 mutant toxins.

In an attempt to prevent proteolytic breakdown of the toxin and to determine whether cleavage at Arg423 contributed to the low potency of Cry1Ac towards M. brassicae, site-directed mutagenesis was used to replace Arg423 with Ala, Gln, or Ser. Oligonucleotides were designed that would enable these substitutions and at the same time remove a BglI restriction endonuclease site from the pMSV.Cry1Ac plasmid (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Sequences of oligonucleotides used for mutagenesis of Arg423 in Cry1Ac

| Substitution | DNA sequence of mutagenic oligonucleotide (5′–3′)a |

|---|---|

| R423A | CGTGCCACCTGCGCAAGGATTTAG |

| R423Q | CGTGCCACCTCAACAAGGATTTAGTC |

| R423S | CGTGCCACCTTCCCAAGGATTTAGTC |

The mutated sites are in boldface type.

Analysis of expression by light microscopy and SDS-PAGE suggested that the R423Q and R423S mutants produced stable δ-endotoxin crystals containing a protoxin molecule of the expected size (130 kDa), whereas the R423A mutant was not stable and appeared to be degraded during and/or after expression in B. thuringiensis IPS-78/11 (data not shown).

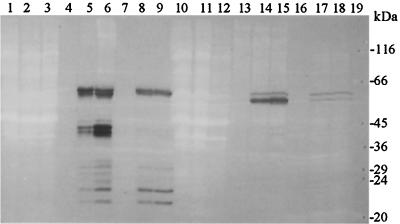

The R423Q and R423S mutants were both soluble in 50 mM Na2CO3–10 mM DTT (pH 10), and activation of these mutants for 24 h with M. brassicae gut juice (5%, vol/vol) resulted in an insoluble ∼58-kDa form and the absence of 40- and 20-kDa breakdown products (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Proteolytic activation of the R423Q and R423S mutants with M. brassicae gut juice. Solubilized R423Q (A) or R423S (B) mutant δ-endotoxin inclusions were activated with 5% (vol/vol) gut juice from M. brassicae for 24 h and separated into insoluble and soluble fractions. Lane 1, molecular weight markers; lane 2, insoluble toxin; lane 3, soluble toxin.

Toxicity of the R423Q and R423S mutants.

Due to differences in the purities of the wild-type Cry1Ac and mutant crystal preparations, toxin crystals were solubilized in 50 mM Na2CO3–10 mM DTT (pH 10) for 1 h before they were incorporated into the artificial diet. Due to the low potency of Cry1Ac towards M. brassicae larvae, a single concentration, 50 μg of toxin/g of diet, was used to challenge neonate M. brassicae larvae (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Toxicities of Cry1Ac and the R423Q and R423S mutants to M. brassicae

| Toxin | % Mortalitya |

|---|---|

| Cry1Ac | 7.5 |

| Cry1Ac R423Q mutant | 12.5 |

| Cry1Ac R423S mutant | 22.5 |

Forty neonate larvae were challenged with 50 μg of toxin/g of diet, and the percentage of mortality was recorded after 6 days.

Neither mutant was able to induce 50% larval mortality in M. brassicae; hence, LC50s could not be determined. However, at the 50-μg/g concentration, the percentage of mortality increased from 7.5% with wild type Cry1Ac to 12.5% with the R423Q mutant and 22.5% with the R423S mutant. The toxicity of these mutants to P. brassicae was not significantly different from the toxicity of wild-type Cry1Ac (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Previously, toxicity data for P. brassicae and M. brassicae have been generated by using different methods (i.e., diet incorporation and leaf dip assays), and this has made comparisons of toxin potencies for these two insect species difficult. Using B. thuringiensis IPS-78/11 purified Cry1Ac toxin inclusions, we performed three independent bioassays and combined the resulting data to obtain mean LC50 with 95% confidence limits. These data demonstrated that Cry1Ac was at least 2,000 times more toxic towards P. brassicae larvae than towards M. brassicae larvae. This difference provides a useful model with which to investigate the factors that contribute to toxin potency and insect resistance.

By using fifth-instar larval gut juice, similarities and differences in Cry1Ac activation were identified for the two insect species. As determined by using proteases from both insects, the N terminus of the ∼60-kDa, activated, soluble form of Cry1Ac occurred at Ile29, a putative trypsinlike cleavage site. This finding is consistent with the findings of Bietlot et al. (4) and suggests that differences in the soluble form of activated Cry1Ac are unlikely to account for differences in toxin potency. In addition to differences in the cleavage positions within domain I of Cry1Ac producing insoluble forms of the toxin, M. brassicae was also shown to process Cry1Ac at Arg423, a trypsinlike cleavage site not recognized by P. brassicae proteases. Arg423 is located towards the C-terminal end of domain II between putative β-sheets 9 and 10, before the exposed loop 3. The importance of the loop regions in toxin binding to insect midgut membranes and in determining activity has been demonstrated (34, 38, 45). Domain III has also been shown to be important in toxin binding to putative midgut receptors (6, 10, 24). If cleavage at Arg423 occurs in vivo, then it is highly likely that removal of loop 3 of domain II and all of domain III would destroy the structural integrity of the toxin molecule and consequently result in an inactive form. Interestingly, both insects generated a ∼60-kDa insoluble form of Cry1Ac with the same N terminus as the soluble toxin (Ile29). It is possible that C-terminal processing induces the toxin to adopt a more open conformation that ultimately produces an insoluble product that comigrates with the soluble form of the toxin during SDS-PAGE. Although providing no information about processing at the C terminus of the toxin, which may also affect potency, these data highlighted clear differences in the pattern of Cry1Ac proteolysis in the two insect species. Although the two insects seem to possess similar arrays of protease classes, the specificities of the proteases themselves seem to differ. The different processing of Cry1Ac in the two insects may contribute to the observed differences in toxin potency, and in the case of M. brassicae, degradation of Cry1Ac may act as a specific resistance mechanism. A similar pattern of toxin proteolysis was observed in vivo, implying that the conditions used in in vitro experiments were representative of the gut environment. It is interesting to note that large proportions of toxin were present in the insoluble fractions of the guts of both insects.

Milne et al. (29) reported that a protein complex present in the midgut of Choristoneura fumiferana (spruce budworm) could inactivate Cry1Aa by precipitation followed by proteolysis, thus accounting for the low potency of this toxin towards this insect. It is possible that a similar resistance mechanism exists in M. brassicae. However, it would be paradoxical if P. brassicae had evolved such a process since this insect is highly susceptible to Cry1Ac. It is unlikely that the insoluble form of the toxin retains activity, since the aggregate would be unable to pass through the peritrophic matrix and subsequently bind to a receptor on the underlying midgut epithelium.

A possible explanation for this paradox is that if proteolysis occurs while the toxin is bound to a specific receptor, then instead of precipitating out of solution, as it does in vitro, it undergoes a conformational change, exposing hydrophobic residues that enable the toxin to oligomerize and/or insert into the hydrophobic membrane. The ability of a toxin to form a pore may therefore be dependent on the sites at which proteolytic nicking occurs, as well as the accessibility of the sites. Domain I of the Cry δ-endotoxins exists as a helical bundle with the hydrophobic faces of the amphipathic helices surrounding a hydrophobic central helix. Proteolytic nicking within domain I may impart greater flexibility to the molecule, perhaps allowing helix pairs from the bundle to act as initiators of membrane insertion (25), or alternatively may induce oligomerization of several nicked toxin molecules. Hence, exposure of hydrophobic segments of the toxin by selective proteolysis when the toxin is close to the membrane may favor irreversible association with the membrane, followed by oligomerization and pore formation.

Knowles et al. (21) showed that Cry1Ac was associated with BBMV from Manduca sexta, Heliothis virescens, and P. brassicae as a doublet. More recently, Aronson et al. (1) showed that binding of Cry1Ac and Cry1Ab to M. sexta and H. virescens BBMV induced oligomerization of toxin molecules. This suggests that toxin proteolysis at the membrane surface may play a role in oligomerization and subsequent toxin insertion into the membrane. However, Aronson et al. (1) did not determine whether the oligomerization of toxin molecules occurs in nonsusceptible insects, such as M. brassicae, and this possibility should be investigated.

In the qualitative binding experiments described in this paper, Cry1Ac was found to bind to BBMV from two insects. The forms of Cry1Ac associated with the midguts of the two insects differed. In M. brassicae, Cry1Ac was bound as a doublet with products having molecular masses of 60 and 58 to 59 kDa, and the higher-molecular-mass form accounted for approximately 90% of the bound toxin. In P. brassicae, the toxin was bound as a distinct doublet with products having molecular masses of 60 and ∼56 kDa that were present in similar amounts. This implies that the two insects are likely to have different Cry1Ac-binding and/or postbinding mechanisms. The generation of a ∼56-kDa form of Cry1Ac may be a prerequisite for activity, and differential processing of membrane-bound Cry1Ac may account for the large difference in toxin potency in these two insect species. The sites at which processing occurs with gut juice may also be recognized by membrane-associated proteases in order to generate the nicked forms of membrane-bound Cry1Ac. The similar sizes of the lower-molecular-weight membrane-associated forms of the toxin and the gut juice-activated nicked toxin products support this possibility. Using a chemiluminescence detection method, we found that Cry1Ac was present as a doublet in midguts from intoxicated P. brassicae larvae and as a single band in the M. brassicae membrane. These findings support the view that differential toxin proteolysis may play a role in membrane binding, and thus toxicity, in vivo.

Formation of the lower-molecular-weight bound products in P. brassicae and M. brassicae BBMV was independent of the source of the gut juice used to activate Cry1Ac. This suggests that proteases associated with the BBMV, not the proteases present in insect gut juice, are likely to be responsible for the proteolytic nicking of Cry1Ac in its bound form. Alternatively, it may suggest that the interaction of Cry1Ac with the P. brassicae receptor(s) and/or membrane may induce a specific conformational change that does not occur during binding to M. brassicae BBMV and exposes amino acids to an increased level of proteolytic attack.

Removal of Arg423, a putative trypsinlike cleavage site within Cry1Ac, prevented degradation of Cry1Ac to the ∼40- and ∼20-kDa fragments with M. brassicae gut juice. Bioassays demonstrated that the potency of the Cry1AcR423S and Cry1AcR423Q mutants was not dramatically increased. This suggests that although degradation of Cry1Ac to ∼40- and 20-kDa products in the gut of M. brassicae may contribute to the low potency of the toxin towards this insect, it is unlikely to be the major determinant. It is probable that other factors, such as binding to a specific functional receptor(s) on the midgut brush border membrane, specific proteolysis within domain I to generate an active hydrophobic form of the toxin, and the propensity of the toxin to insert into the target membrane and induce the formation of a pore, play additional roles in the specificity and potency of Cry1Ac. Modification of the Cry1Ac toxin molecule at sites that control these properties may increase the potency even further.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Trevor Sawyer for technical assistance, Debbie Ellis for help with bioassays, Joe Carroll for advice, and Chris Green for photographic work.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and Horticulture Research International.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aronson A I, Geng C, Wu L. Aggregation of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1A toxins upon binding to target insect larval midgut vesicles. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2503–2507. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.6.2503-2507.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronson J N, Arvidson H C. Toxic trypsin digest fragment from the Bacillus thuringiensis parasporal body. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1987;53:416–421. doi: 10.1128/aem.53.2.416-421.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bai C, Yi S X, Degheele D. Determination of protease activity in regurgitated gut juice from larvae of Pieris brassicae, Mamestra brassicae and Spodoptera littoralis. Meded Fac Landbouwwet Rijksuniv Gent. 1990;55:519–525. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bietlot H P, Carey P R, Pozsgay M, Kaplan H. Isolation of carboxyl-terminal peptides from proteins by diagonal electrophoresis: application to the entomocidal toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis. Anal Biochem. 1989;181:212–215. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bone E J, Ellar D J. Transformation of Bacillus thuringiensis by electroporation. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1989;58:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(89)90033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burton S L, Ellar D J, Li J, Derbyshire D J. N-Acetyl galactosamine on the putative insect receptor aminopeptidase N is recognised by a site on the domain III lectin-like fold of a Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin. J Mol Biol. 1999;287:1011–1022. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chestukhina G C, Kostina L I, Mikhailova A L, Tyurin S A, Klepikova F S, Stepanov V M. The main features of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin molecular structure. Arch Microbiol. 1982;132:159–162. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choma C T, Surewicz W K, Carey P R, Pozsgay M, Raynor T, Kaplan H. Unusual proteolysis of the protoxin and toxin from Bacillus thuringiensis: structural implications. Eur J Biochem. 1990;189:523–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb15518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christeller J T, Liang W A, Markwick N P, Burgess E P J. Midgut protease activities in 12 phytophagous lepidopteran larvae—dietary and protease inhibitor interactions. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;22:735–746. [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Maagd R A, Bakker P L, Masson L, Adang M J, Sangadala S, Stiekema W, Bosch D. Domain III of the Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin Cry1Ac is involved in binding to Manduca sexta brush border membranes and to its purified aminopeptidase N. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:463–471. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finney D J. Probit analysis. 2nd ed. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 1952. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grochulski P, Masson L, Borisova S, Pusztaicarey M, Schwartz J L, Brousseau R, Cygler M. Bacillus thuringiensis CryIA(a) insecticidal toxin crystal structure and channel formation. J Mol Biol. 1995;254:447–464. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1995.0630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haider M Z, Knowles B H, Ellar D J. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis var. colmeri insecticidal δ-endotoxin is determined by differential proteolytic processing of the protoxin by larval gut proteases. Eur J Biochem. 1986;156:531–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hofmann C, Lüthy P, Hutter R, Pliska V. Binding of the delta-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis to brush border membrane vesicles of the cabbage butterfly (Pieris brassicae) Eur J Biochem. 1988;173:85–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb13970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofmann C, Vanderbruggen H, Höfte H, Van-Rie J, Jansens S, Van-Mellaert H. Specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxins is correlated with the presence of high-affinity binding sites in the brush border membranes of target insect midguts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:7844–7848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.21.7844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Höfte H, Whiteley H R. Insecticidal crystal proteins of Bacillus thuringiensis. Microbiol Rev. 1989;53:242–255. doi: 10.1128/mr.53.2.242-255.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Höfte H, Degreve H, Seurinck J, Jansens S, Mahillon J, Ampe C, Vandekerckhove J, Vanderbruggen H, van-Montagu M, Zabeau M, Vaeck M. Structural and functional analysis of a cloned delta-endotoxin of Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. berliner 1715. Eur J Biochem. 1986;161:273–280. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb10443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inagaki S, Miyasono M, Ishiguro T, Takeda R, Hayashi Y. Proteolytic processing of δ-endotoxin of Bacillus thuringiensis var. kurstaki HD-1 in insensitive insect, Spodoptera litura: unusual proteolysis in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate. J Invertebr Pathol. 1992;60:64–68. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jongsma M A, Peters J, Steikema W J, Bosch D. Characterisation and partial purification of gut proteinases of Spodoptera exigua Hübner. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;26:185–193. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keller M, Sneh B, Strizhov N, Prudovsky E, Regev A, Koncz C, Schell J, Zilberstein A. Digestion of delta-endotoxin by gut proteases may explain reduced sensitivity of advanced instar larvae of Spodoptera littoralis to CryIC. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;26:365–373. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(95)00102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knowles B H, Knight P J K, Ellar D J. N-acetyl galactosamine is part of the receptor in insect gut epithelia that recognises an insecticidal protein from Bacillus thuringiensis. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1991;245:31–35. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1991.0084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli U K, Favre M. Maturation of the head of bacteriophage T4. J Mol Biol. 1973;80:575–599. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90198-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lecadet M M, Martouret D. Enzymatic hydrolysis of the crystals of Bacillus thuringiensis by the proteases of Pieris brassicae. I. Toxicity of the different fractions of the hydrolysate for larvae of Pieris brassicae. J Invertebr Pathol. 1967;9:310–321. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee M K, You T H, Gould F L, Dean D H. Identification of residues in domain III of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry1Ac toxin that affect binding and toxicity. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:4513–4520. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.10.4513-4520.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li J, Carroll J, Ellar D J. Crystal structure of an insecticidal δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis at 2.5Å resolution. Nature. 1991;353:815–821. doi: 10.1038/353815a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lowry O H, Rosebrough N J, Farr A L, Randall R J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lüthy P, Ebersold H R. Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxin: histopathology and molecular mode of action. In: Davidson E W, editor. Pathogenesis of invertebrate microbial diseases. Montclair, N.J: Allanheld, Osmun & Co.; 1981. pp. 235–268. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milne R, Kaplan H. Purification and characterization of a trypsin-like digestive enzyme from spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) responsible for the activation of δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1993;23:663–673. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(93)90040-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milne R E, Pang A S D, Kaplan H. A protein complex from Choristoneura fumiferana gut-juice involved in the precipitation of delta-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. sotto. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 1995;25:1101–1114. doi: 10.1016/0965-1748(95)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nagamatsu Y, Itai Y, Hatanaka C, Funatsu G, Hayashi K. A toxic fragment from the entomocidal crystal protein of Bacillus thuringiensis. Agric Biol Chem. 1984;48:611–619. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ogiwara K, Indrasith L S, Asano S, Hori H. Processing of δ-endotoxin from Bacillus thuringiensis subsp. kurstaki HD-1 and HD-73 by gut juices of various insect larvae. J Invertebr Pathol. 1992;60:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0022-2011(92)90084-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oppert B, Kramer K J, Johnson D E, MacIntosh S C, McGaughey W H. Altered protoxin activation by midgut enzymes from a Bacillus thuringiensis resistant strain of Plodia interpunctella. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;198:940–947. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Oppert B, Kramer K J, Beaman R W, Johnson D E, McGaughey W H. Proteinase-mediated insect resistance to Bacillus thuringiensis toxins. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23473–23476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajamohan F, Hussain S R A, Cotrill J A, Gould F, Dean D H. Mutations at domain-II, loop 3, of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIAa and CryIAb delta-endotoxins suggest loop 3 is involved in initial binding to lepidopteran midguts. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25220–25226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schnepf H E, Whiteley H R. Delineation of a toxin-encoding segment of a Bacillus thuringiensis crystal protein gene. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:6273–6280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Smedley D P, Ellar D J. Mutagenesis of three surface-exposed loops of a Bacillus thuringiensis insecticidal toxin reveals residues important for toxicity, receptor recognition and possibly membrane insertion. Microbiology. 1996;142:1617–1624. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-7-1617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith G P, Ellar D J. Mutagenesis of two surface-exposed loops of the Bacillus thuringiensis CryIC δ-endotoxin affects the insecticidal specificity. Biochem J. 1994;302:611–616. doi: 10.1042/bj3020611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas W E, Ellar D J. Mechanism of action of Bacillus thuringiensis var. israelensis insecticidal δ-endotoxin. FEBS Lett. 1983;154:362–368. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80183-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tojo A, Aizawa K. Dissolution and degradation of Bacillus thuringiensis δ-endotoxin by gut juice protease of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1983;45:576–580. doi: 10.1128/aem.45.2.576-580.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Rie J, Jansens S, Höfte H, Degheele D, Van Mellaert H. Receptors on the brush border membrane of the insect midgut as determinants of the specificity of Bacillus thuringiensis delta-endotoxins. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1378–1385. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.5.1378-1385.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wabiko H, Yasuda E. Bacillus thuringiensis protoxin: location of the toxic border and requirement of non-toxic domain for high level in vivo production of the active toxin. Microbiology. 1995;141:629–639. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-3-629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wabiko H, Raymond K C, Bulla L A. Bacillus thuringiensis entomocidal protoxin gene sequence and gene product analysis. DNA. 1986;5:305–314. doi: 10.1089/dna.1986.5.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wolfersberger M G, Lüthy P, Maurer A, Parenti P, Sacchi V F, Giordana B, Hanozet G M. Preparation and partial characterization of amino acid transporting brush border membrane vesicles from the larval midgut of the cabbage butterfly (Pieris brassicae) Comp Biochem Physiol. 1987;86:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu S J, Dean D H. Functional significance of loops in the receptor binding domain of Bacillus thuringiensis CryIIIA δ-endotoxin. J Mol Biol. 1996;255:628–640. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]