Abstract

Work-family conflict has become one of the most prominent challenges of modern-day work and a prominent research topic. However, the “family” in the work-family interface has been undertheorized, while research focuses on the workplace factors and individual characteristics in relation to work-family conflict (WFC). Placing the family at the center of theorizing, we adopt the Contextual Model of Family Stress (CMFS) as an overarching framework, which conceptualizes the family as a complex system comprising the family members, the environment in which they are situated, and their interactions with the environment and with one another. Guided by CMFS, we theorized WFC as a disturbance to the family’s structural and psychological contexts, which creates strain on the family well-being. Furthermore, we argued that family strain could produce strain and stress back to the focal workers, which reduces their voice behaviors at work. We further argue that workers’ work-family segmentation preference will shape their experience of WFC and moderate the indirect effect of WFC on employee voice behavior through family well-being. We collected data across two multi-wave, time-lagged surveys in America (M-Turk, N = 330) and in China (organization employees, N = 209). We found that employee-rated family well-being mediates the negative relationship between WFC and voice behavior, and the indirect relationship is stronger as the employees’ preference for segmentation is higher. The results open up a promising avenue for more nuanced inquiry into the family system framework and its role in the work-family interface.

Keywords: Work-family conflict, Family well-being, Voice behavior

Our lives are shaped by multiple roles in various contexts and social relationships (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000; Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985), among which work and family are arguably two critical domains. Each domain carries its own role expectations and prescriptions (Burke & Reitzes, 1981; Burke & Stets, 2009). Work-family conflict (WFC) occurs when fulfilling the role in one domain interferes with fulfilling roles in the other domain (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985). The Covid-19 pandemic illustrated vividly various ways work and family roles clash and workers’ struggle not to drop the ball on either. Therefore, it is no surprise that WFC remains a prominent subject for academics and practitioners alike.

Vast amounts of research on WFC took place over the past few decades (see Allen et al., 2020; French et al., 2018; Nohe et al., 2015; Reichl et al., 2014; Amstad et al., 2011 for reviews). Interestingly, despite the name that gives equal weight to work and family, WFC research has largely overlooked the family domain in both theoretical and empirical development. Conceptually, the family domain has been examined largely through workers’ role expectations or responsibilities within the domain (Ashforth et al., 2000; Edwards & Rothbard, 2000). This personal role-centric approach allows the examination of workers’ management of the role expectations across the two domains (e.g., Byron, 2005; Edwards & Rothbard, 2000). Recent research on the dynamics between couples shifted the focus from individuals to spouses and their mutual influence on one another (e.g., Hammer et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2020). Still, our behavioral and relationship patterns are embedded in larger social structures, such as families (Stryker & Burke, 2000), which consist much more than individual members and spousal relationships. Rather, the family structure has its own structural and social properties, separate from that of the individual members (e.g., the family value or stress does not belong to a particular member). Moreover, the social and structural properties of families deeply affect and are affected by family members’ own behaviors and interactions with one another. Therefore, studying the work-family interface requires that scholars take a more expanded view of “what is in a family.” In this regard, research specifying and theorizing the family’s unique characteristics has been severely lacking (one notable exception is research on family demands, which is still largely theorized as time-based role demand for the focal worker.

Relatedly, this conceptual abstraction also led to the largely abstract measurement of family-related constructs. A scan of the WFC literature reveals that family satisfaction (e.g., Allen et al., 2020; Ford et al., 2007) and its several variations (e.g., relationship satisfaction [Wilson et al., 2018]; marital satisfaction [Heller & Watson, 2005; Judge et al., 2006]; family relationship satisfaction are among the most studied family-related constructs. Nonetheless, the measurement of these constructs has two major limitations.1 One concerns the specificity of the measure. Most articles adopted a global evaluation of satisfaction without considering different aspects within the family. Therefore, the more nuanced, unique characteristics may be left unexamined. The other limitation regards the person-centric perspective of the items, which emphasizes how the focal workers feel themselves (e.g., “I am satisfied with my family”), rather than an evaluation of a specific aspect of the family (e.g., “the family is well-functioning”).

Therefore, we believe that the time is ripe to expand our perspective on WFC to explore the nuanced structural characteristics of the family domain. Toward this end, we argue that the Contextual Model of Family Stress (CMFS; Boss, 2002; Boss et al., 2016) may be particularly relevant and helpful to dissect the family domain. CMFS positions the family as the reference point for family stress, instead of individual members. It posits that family stress is caused by disturbances (e.g., WFC) in the equilibrium within the family system, a multifaceted entity comprising of family members, their relationships, and layers of family context (social, economic, etc.). As such, it provides a useful lens to examine alternative mechanisms through which individual workers’ WFC affects aspects of the family system, which might then affect the workers.

Guided by the CMFS framework, one of the constructs that capture the complex functioning of the family domain is family well-being as proposed by Noor and colleagues (Noor et al., 2014). It refers to the holistic, balanced development of family members’ physical, mental, and spiritual well-being, and the harmonious relationship among family members (Mellor et al., 2014; Noor, et al., 2014). Specifically, we want to investigate how workers’ WFC will impact family well-being. Recognizing the bidirectional influences between work and family (Byron, 2005; Frone et al., 1997), we focus on the work-to-family conflict aspect of WFC in our theorizing, in line with the original theorization on work-family conflict (e.g. Greenhaus & Powell, 2003).

Moreover, voice behavior is also of particular interest. It refers to “discretionary communication of ideas, suggestions, concerns, or opinions about work-related issues with the intent to improve organizational or unit functioning” (Morrison, 2011, p. 375). As such, it is often considered one type of organizational citizenship behavior (OCB; Van Dyne & LePine, 1998) as it voluntarily promotes organizations’ collective interest beyond the formal boundary of job requirements (Podsakoff et al., 2000). Moreover, it is not only vital to organizational success (e.g., Morrison, 2014), but also increasingly crucial for workers’ performance evaluation (Bolino & Turnley, 2005). Yet, previous research on the antecedents of voice behavior mostly focused on individual and workplace-related contextual factors (see reviews by Chamberlin et al., 2017; Morrison, 2014), while family characteristics, arguably important contextual factors for workers, remain largely neglected.2 Therefore, another goal of the study is to examine the linkage between workers’ family well-being and their voice behavior at work.

Finally, CMFS emphasizes that the impact of a stressor depends not only on the stressor itself but also on how each member interprets the stressor. We argue that one important factor is the workers’ segmentation preference, the extent they wish to separate or integrate their work domain and family domain (Ashforth et al., 2000; Kreiner, 2006; Rothbard et al., 2005). Particularly, while previous research showed that stronger segmentation preference may reduce WFC (e.g., Park et al., 2011) or attenuate other factors’ influence on WFC (e.g., Xin et al., 2018), we want to investigate the other side of the coin: given a certain level of WFC, how will segmentation preference moderate the effect of WFC, in this case, on family well-being and voice behavior?

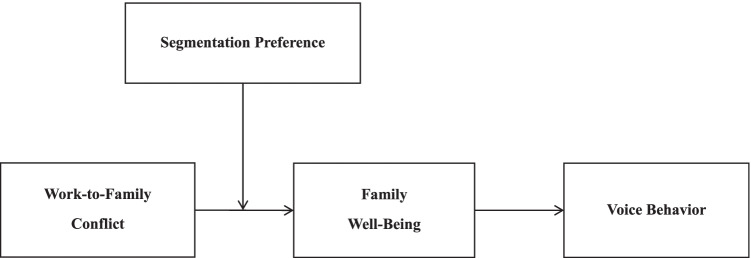

The overall moderated mediation model, shown in Fig. 1, was tested progressively across two three-wave time-lagged field surveys through Amazon M-Turk and in a field survey in China, respectively. Through the study, we aim to make two main contributions. First, by introducing the Contextual Model of Family Stress (Boss, 2002) as the overarching framework, the study offers an expanded theoretical framework on the work-family interface. While previous research largely conceptualized WFC as intra-person role conflict, in the CMFS framework, it is conceptualized as disturbances to the family system equilibrium (Boss, 2002), which then affects family members (the focal workers themselves, in this case). This family-oriented approach complements the current role-based framework and Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 2002) by providing an alternative explanatory logic situated in the family context, which allows future exploration and specification of other family-centric mechanisms of WFC.

Fig. 1.

Overall theoretical model

Relatedly, this study also helps validates an alternative conceptualization and measurement of family well-being. While previous research mostly measured family well-being through a global evaluation (e.g. Edwards & Rothbard, 1999; Kalliath et al., 2017), guided by CMFS, we adopted a more structured and detailed conceptualization and measurement (Mellor et al., 2014; Noor et al., 2014) that specify various dimensions of family functioning (e.g., positive and negative family functioning, such as trust and care towards one another; tolerance, such as patience for each other; and parental understanding, such as understanding children’s need; Mellor et al., 2014), which is integral in the family system. This approach provides a promising alternative to capture the complex family domain and helps inspire future research on more family-oriented constructs.

Furthermore, the study expands our knowledge of the family-based contextual antecedents of voice behavior. As organizations increasingly focus on the contextual performance of employees beyond the scope of routine task performance (Christian et al., 2011; Demerouti, Bakker, et al., 2014; Demerouti, Xanthopoulou, et al., 2014), voice behavior quickly gained prominence in management research (Chamberlin et al., 2017). Towards this end, research on the individual and workplace contextual antecedents of voice behavior gradually reaches saturation, while examination of the potential impact of family context remains scarce. The family context is closely tied to workplaces (Edwards & Rothbard, 2000), and workers’ family systems invariably affect the workers as they enter the workplace. As a result, this omission prevents us from gaining critical insights regarding the driving factors of voice behaviors. By examining the link between holistic family well-being on voice behaviors, we aim to expand the scope of the antecedents to voice behavior and highlight the instrumental role of family functioning in workers’ management of the work-family interface. Relatedly, in introducing CMFS as the guiding theoretical framework, this paper also opens up a new promising avenue of research on the family-oriented antecedents of voice behavior, complementing the currently prevailing person-centric perspectives.

Theory and Hypotheses

In this part, we will first review the core tenets of the Contextual Model of Family Stress (CMFS), and then gradually build the causal links from work-to-family conflict to family well-being, and then, to voice behavior. Thereafter, we will articulate the role of segmentation preference as a boundary condition to the previous causal relationship. See Fig. 1 for the complete model.

WFC and CMFS

Originally articulated by Boss (2002), the Contextual Model of Family Stress shares some theoretical roots (e.g., Identity Theory [Burke & Stets, 2009] and Symbolic Interactionism [Blumer, 1980; Goffman, 1959]) with traditional work-family interface research. What makes it unique is the perspective that family is a separate system, one that consists of family members but is also separate from the members themselves (e.g. Satir, 1988). From a family system perspective (Boss, 2002; Boss et al., 2016), the essence of family is the interactions among members, and while all members contribute to the family dynamic, the family dynamic is more than its parts contributed by individual members (Boss, 2002), and the potential interactions one has within the family domain would be complex and multifaceted, which go beyond individual role performance or the dyadic relationship with the spouse. These are the two main focuses of previous research.

Instead, a family consists of its external and internal structures. The external structure refers to the culture, history, economy, development, and heredity factors, most or all of which are outside the family’s control. The family has more control over its internal environment, however, which consists of the structural context, psychological context, and philosophical context (Boss et al., 2016). Structural context refers to membership and role assignments, routines and family activities, etc. Psychological context refers to the perceptions within the family (such as care, trust, and respect towards one another, and towards the family) and appraisal of events. Philosophical context refers to the higher-level values and beliefs within the family unit. While all environmental components affect the family functioning in different ways, for the purpose of this study, we choose to focus on the internal structure of a family, especially structural and psychological contexts, as they are most sensitive and malleable in reaction to external events.3

In this regard, WFC is considered as a stressor event, a disturbance that may break the existing equilibrium in the family. From a normative standpoint, the interference from work to family violates the norms and principles of the family (its structural and philosophical contexts), making workers fail to meet the expectations within the family unit (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985), thus creating strains on the relationships among family members. For example, the interference may violate the family rituals (e.g., tucking the kids in bed on time) and break off the routine (e.g., a regular family time before or after meals, such as the family game night or movie nights) which could negatively affect family stability. Or, as Yoon et al. (2015) demonstrated, missing a family meal may also add to the stress level of the family. Furthermore, the violation may also raise a concern about the boundary of the family (i.e., where do we draw the line?), the membership (i.e., are you truly a member of the family?), and the role assignments within the family (i.e., can you shoulder the responsibilities?).

As a result, WFC may shock the structural and psychological contexts of the internal family structure and lead to the family’s experience of an ambiguous loss (the absence of the worker in the family life; Boss, 2007), thus causing (at least temporarily) stress and strain within the family system. It is worth noting that the impact of the stressors on the family system may not necessarily be linear but travel through a complicated process to influence one or more of the internal family contexts. Therefore, while workers’ stress (e.g., WFC) contributes to the overall family stress and may break the equilibrium, the resulting stress level of the family may be qualitatively different from that of the workers, which underlines the unique contribution of the family system and the importance of theorizing about it.

Some research did indicate the potential negative consequences of such stress and strain caused by WFC. For example, Huffman et al. (2017) found that WFC could increase the distress level among the couple.4 We go beyond the individual and couple-focused outcomes and emphasize that work-to-family conflict could affect broader family contexts, which are separate from individual members (Satir, 1988). The construct of family well-being proposed by Noor and colleagues (Noor et al., 2014) consists of positive family functioning (e.g., caring for each other), negative family functioning (fighting among family members), tolerance (e.g., be patient with one another), and parental understanding (e.g., understand children’s need). Their conceptualization of family well-being taps into the structural and psychological contexts of a family and captures the spirit of the family as a system.

Therefore, we argue that focal workers’ WFC could lead to both physical (Greenhaus, Allen, & Spector, 2006) and emotional strain (Dettmers, 2017) among the family members, then deterioration of the family’s structural (e.g., routine, family time, responsibilities) and psychological contexts (e.g., respect, trust), eventually causing an increase in the stress level in the family that drives the family system more dysfunctional and less harmonious. Therefore, work-to-family conflict may cause the experience of lower level of family well-being. Thus:

Hypothesis 1. Work-to-family conflict is negatively associated with one’s experience of family well-being.

When the family’s instrumental and psychological contexts are pressured by the stressor, WFC in this case, the family is strained. The concept of family strain refers to the phenomenon where families still function but are shaken by the stressor, due to a mismatch between the pressure caused by the stressor and the family resources available to cope with the pressure (Boss et al., 2016). Family resources are the economic, social, psychological, and physical assets to respond to stressor events, such as WFC (Boss et al., 2016). In this case, as WFC disrupts the family routine and responsibility assignment and creates cracks in the relationships between members, the families may scramble to rearrange the family structure and repair the relationships, at least in the short run.5

The strained family environment may in turn put pressure on family members, the focal workers included, who are concerned and distracted by the fallout in the family. As a result, negative emotions may ensue (Liu et al., 2012), and work engagement decreases as well (e.g. Liu et al., 2015; Scott et al., 2015). Furthermore, even as workers themselves may adjust quickly to the strain alone, the family system may take a longer time to adjust and adapt (Boss et al., 2016). As workers are connected to the family system, they cannot be spared from the lingering wound in the family and would share the strain when they engage in the home environment. Therefore, individual coping and adjustment may not be as effective, or not as quickly.

This individual strain passed on from the family system would, in turn, impact one’s performance at work (Amstad et al., 2011; Eby et al., 2005). Just as Boss (2007)’s assertation that resources are integral to families’ coping with stress and strain, resources are equally crucial for individuals for goal completion (Hobfoll, 1989). Moreover, family members engage in a two-way resource exchange with the family; the family could be enriching or depleting members’ own resources (Rothbard, 2001). As Conservation of Resources Theory (Hobfoll, 1989) posits, people feel stress when resources are lost or threatened to be lost. Therefore, as the strain on family well-being prevents resource enrichment but demands that workers divert more resources to cope with the strain of the family, these workers may experience both physical and emotional exhaustion, which in turn affects workers’ resource allocation at work (Hobfoll et al., 2018; Trougakos et al., 2015; Demerouti, Bakker, et al., 2014; Demerouti, Xanthopoulou, et al., 2014).

However, in further delineating the impact of lower family well-being on performance, we argue that, due to different natures of work, one’s performance would not take the hit evenly. Specifically, the strain should hit hardest those performance areas that are particularly challenging and demanding, while simpler or easier tasks may not be affected as much (Dahm et al., 2015). Employee voice behavior, in particular, is one such area of demanding performance at work. Bolino and Turnley (2005) argued that voice behaviors may involve not only extra time but also extra physical and mental energy. Moreover, voice behavior often involves suggestions that break the status quo; hence, voice behavior is inherently riskier (Ng & Feldman, 2012; Van Dyne et al., 1995) and more stress-inducing (Tziner & Sharoni, 2014). Therefore, voice behavior may be particularly sensitive to the workers’ own stress and resource reserve for coping. Indeed, a previous meta-analysis showed a negative relationship between workers’ stress and voice behavior (Ng & Feldman, 2012). Therefore, when the strain on family well-being already distracts and puts pressure on the workers, they may be less likely to engage in voice behaviors, even though the potential positive outcome of voice behavior may possibly grant the employees more resources (Ng & Feldman, 2012). Thus:

Hypothesis 2. Experience of family well-being is positively associated with voice behavior.

Throughout the argument above, we illustrate how WFC may break the equilibrium of the family system, creating a strain on the family well-being, which subsequently strains the employees so that they are less likely to perform voice behavior at work. Central to this perspective is the role of the family as a system. When the family system equilibrium is broken by the disturbance (in this case, WFC), the system reacts to the disturbance independent of the reactions of the individual family members (Boss et al., 2016). In this case, we argue that family well-being serves as one mechanism through which the disturbance disrupts the family structural and psychological contexts, which then triggers subsequent strain on individual resources for the focal workers, which eventually hurts their performance on challenging voice behaviors in the work domain.

It is worth noting that although there are few studiesexamining the link between WFC and voice behavior, some studies (e.g., Beham, 2011; Bragger et al., 2005; Tziner & Sharoni, 2014) showed that WFC is negatively related to organizational citizenship behavior (OCB), of which voice behavior is conceptualized as a part (Coleman & Borman, 2000). Yet, the findings were inconsistent (e.g., Webster, Edwards, and Smith [2019] found that workers who showed higher levels of WFC did not suffer in OCB). Part of the inconsistent findings may be due to the fact that these studies utilized a general measure of OCB (without specifying the voice construct). Given that some OCB sub-dimensions are more affiliative (helping behaviors, compliance) and voice behavior is more challenging (Graham & Van Dyne, 2006; Van Dyne, et al., 1995), the link between WFC and different aspects of OCB may not be uniform, and we may expect the negative association between WFC and voice behavior to be particularly salient. Thus:

Hypothesis 3. Perceived family well-being mediates the negative relationship between work-to-family conflict and subsequent voice behavior.

Individual Segmentation Preference

As much as the disturbance of WFC may disrupt the family routine and throw the family off the equilibrium, the exact impact of the disturbance also depends on the perception or the appraisal of the disturbance (Hill, 1971). That is to say, the same disturbance may affect different people and families differently (Hill, 1958). In the CMFS framework, the perception of the stressor events is central to understanding the impact of those events (Boss et al., 2016). Particularly, as the focal person struggling with WFC, the worker’s own perception of WFC is instrumental in the level of strain the WFC brings to the family. According to CMFS, people interpret events according to their own values or beliefs (e.g., how things should work out; Boss et al., 2016). If the disturbance event fits the narratives based on their own values and beliefs, the events may cause less stress to the family. On the contrary, if the disturbance contradicts their values, this misfit may exacerbate the stress and strain on the family.

One important personal value in this context may be the desired ways to negotiate the boundary between work and family domains. Workers could define the boundary between work roles and family roles (Allen et al., 2014; Ashforth et al., 2000), from entirely separate (segmentation) to completely overlapping (integration). Moreover, they also display a spectrum of preferences for the level of segmentation they prefer (Kreiner, 2006). This segmentation preference reflects individuals’ own personal values of who they want to be (Higgins, 1987; Markus & Nurius, 1986) and should remain stable over time (Kreiner, et al., 2009). Therefore, the segmentation preference between the two domains comes to affect how workers make sense of the actual boundary (Kreiner et al., 2009; Rothbard et al., 2005). That is, workers’ reaction to the actual boundary depends on whether it aligns with their preferred boundary.

In this case, if workers have a low segmentation preference, they may not mind as much the interference of work into family life. They may be used to or have adapted to the interference, or they may be ready to embrace it (Zhang et al., 2019). This mindset makes the WFC less threatening to the family with a smaller impact on the family structures, routines, and relationships. On the contrary, if the workers have a very high segmentation preference, even a small degree of interference might be perceived as threatening. As a result, they will try hard to separate the work domain from the family domain (Kreiner et al., 2009). Therefore, when they are still hit with WFC despite trying hard to avoid it, they may be more frustrated and stressed with the situation (the family might be too). This heightened stress may then translate into more destruction to the family structure and cause more division between the focal worker and the family members. In sum, we argue that with the same WFC level, the higher the workers’ segmentation preference, the bigger the impact of WFC on family well-being. Thus:

Hypothesis 4: Individual segmentation preference moderates the indirect relationship of work-to-family conflict and voice behavior through the experience of family well-being, so that the effect is stronger for those with higher segmentation preference.

Method

The model and hypothesis are tested via two progressive studies. In study 1, we conducted a three-wave, time-lagged field survey on the Amazon Mechanical-Turk platform. In study 2, we collected multi-source data (with paired employees and their supervisors) from China via three waves of a time-lagged survey to replicate and extend the findings in study 1. In both studies, we utilize PROCESS macro in SPSS to systematically test the hypothesis and apply the bootstrapping technique and the criteria of 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals to determine the indirect effect and conditional indirect effect (Hayes, 2012).

Study 1

Research Design and Sample

In this study, we chose the online platform of Amazon Mechanical-Turk to complete the data collection, due to its wide accessibility to the public and the possibility to target people in a variety of industries in a cost-effective way. We asked participants a broad set of demographic questions at wave 1 and later examined their responses to detect any potential biases in the demographic composition. We conducted 3 waves of surveys on the platform, 2 weeks apart between two waves. On wave 1, we measured participants’ work-to-family conflict, as well as their demographic information. On wave 2, we measured their perceived family well-being, and their segmentation preference, and on wave 3, we measured their voice behavior at work.

At wave 1, 578 participants were retained, out of 600 collected (I had to delete unusable data, such as a large number of missing answers or filler answers; same below). At wave 2, 440 subjects were retained (76% retention rate). After wave 3, 364 subjects were retained (83% retention rate). Overall, I was able to retain 63% of participants across three waves, which is acceptable considering the online platform nature and the 2-week intervals between each wave. Moreover, after deleting people who failed at least one attention check question in each survey, the sample size decreased from 364 to 330 (about a 10% decrease). Of all the variables used in the analysis later, all have 330 responses, except age, which only recorded 327 responses, and education, which recorded 329 responses.

The final sample for analysis consists of 330 working adults (52.1% male) with an average age of 36.31 (SD = 9.78). The racial composition was Caucasian leaning. A percentage of 71.2% of participants self-identified as white, 10.9% black or African American, 7.6% Hispanic, 7% Asian, 1.2% Native American, and 2.1% as other ethnicities. Moreover, all participants graduated high school, 50.5% have bachelor’s degrees, and 15.2% have master’s degrees and above. Considering that only 33.4% of adults 25 years and older hold a bachelor’s degree in the US during the last census (Wilson, 2017), the sample was better educated than the general public. Moreover, 36.6% participants reported household income below $50,000, 26.6% had household income between $50,000 and $70,000, and 37.2% had income higher than $70,000. Given the $61.372 medium household income in the USA during the last census (Davidson, 2018), the sample roughly reflected the average household financial situation. Lastly, 39.7% of participants had never married, and 48.5% were married at the time of the study, which roughly matched the marriage rate of 50% in the USA. Overall, the retained sample did not appear to deviate significantly from the average demographic patterns in the public.

Furthermore, we ran the attrition analysis following Goodman and Blum (1996) to verify whether the attrition from the study was nonrandom. We used multi-nominal logistic regression on SPSS 24. We coded groups with different completion patterns (only the first survey completed, the first two surveys completed, or all three surveys completed) as dependent variables. Demographic variables were entered as independent variables. The result showed that none of the demographic variables was a significant predictor of attrition, except ethnicity. Detailed cross-tab analysis showed that Asians and Hispanics were more likely to complete all three surveys than other ethnicities (75% and 70%, respectively). In contrast, 64% of Caucasian participants and 48% of black or African American participants completed all three surveys. In a later analysis, I controlled for ethnicity when testing the model. Results showed that ethnicity was not a significant predictor in the models, and the resulting pattern did not change whether I included ethnicity or not. Therefore, the result suggests that the nonrandom attrition due to ethnicity should not pose a serious threat to the validity of the result.

Measurement

We adopted a 7-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = “strongly disagree” to 7 = “strongly agree”) for each measurement scale. The measures were in English.

Work-to-Family Conflict

Work-to-family conflict was measured with 4 items based on Kopelman et al. (1983). The original scale consisted of two dimensions of work-to-family and family-to-work conflicts. We only used the work-to-family conflict part of the scale. A sample item is “My family dislikes how often I am preoccupied with my work while I am home.” The scale showed good overall reliability, Cronbach alpha = 0.88.

Segmentation Preference

Segmentation preference was measured with 4 items based on Kreiner (2006). A sample item is “I don’t like work issues creeping into my home life”. The scale showed good overall reliability, Cronbach alpha = 0.88.

Family Well-Being

Family well-being was measured based on a modified version of the Chinese Family Assessment Instrument by Mellor et al. (2014). The original scale consists of 18 items. We modified the items for this study to reflect the different cultures between the western world and China. The resulting scale consisted of 8 items. Sample items include “Family members are willing to tolerate each other” and “Family members give emotional support to each other.” The scale showed good overall reliability, Cronbach alpha = 0.96.

Voice Behavior

Voice behavior is measured with 9 items from Liu et al. (2010). Sample items include “I speak up and influence the supervisor regarding issues that affect the organization” and “I suggest my supervisor to introduce new structures, technologies, or approaches to improve efficiency.” The scale showed good overall reliability, Cronbach alpha = 0.93.

Control Variables

Because work-to-family conflict may affect men and women differently (e.g., Duxbury & Higgins, 1991), we controlled for participant gender in hypothesis testing. Furthermore, as people may slowly adapt to the work-family conflict, the effect of WFC may be weaker for those who have more experience with it than those with less experience with it. Therefore, we controlled for participants’ age. Moreover, since ethnicity was a factor of attrition in the survey, I controlled for participants’ race in the study as well. Education, income, and marital status were also entered into the analysis as control variables, as they were frequently selected in previous research.

Result

In analyzing the data, we first conducted confirmatory factor analysis in MPlus (Muthen & Muthen, 2017) to ensure the discriminatory validity of the constructs we use in the survey. After obtaining satisfactory results, we moved on to hypothesis testing via PROCESS in SPSS. Specifically, the PROCESS macro allowed bootstrapping method to calculate the confidence intervals, which we adopted as criteria for the significance of the indirect effect (Hayes, 2012).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To establish the discriminatory validity across the main measurement scales, we conducted a CFA test using MPlus 7.0. The resulting 4-factor solution shows good fit, RMSEA = 0.05 [95%CI = (0.04, 0.06), p = 0.47], CFI = 0.96, SRMR = 0.04. Furthermore, we also tested the fit of alternative models and ran the model comparison test. The result showed that the proposed model fit is better than any other alternative model. Therefore, we retained the 4-factor solution and proceeded with hypothesis testing.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics and the variable correlations. The correlation between work-to-family conflict and family well-being was weak and not significant (r = − 0.09, ns). The correlation between family well-being and voice was significant, r = 0.20, p < 0.05. Moreover, the correlation between WFC and voice behavior was not significant (r = 0.03, ns). Regarding the control variables, only gender and income were correlated with model variables. We tested the model with and without participants’ gender and income, which led to identical patterns. To maintain the model parsimony (Becker, 2005), in the subsequent hypothesis testing section, we only show results with the model variables.

Table 1.

Study 1 descriptive statistics

| Mean | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Gender | N/A | |||||||||

| 2. Age | 36.31 | 0.09 | ||||||||

| 3. Ethnicity | N/A | 0.02 | − 0.08 | |||||||

| 4. Education | N/A | 0.00 | 0.04 | − 0.05 | ||||||

| 5. Income | N/A | − 0.10 | .14* | − 0.05 | .36* | |||||

| 6. Marital status | N/A | .15* | .46* | − 0.07 | .12* | 0.06 | ||||

| 7. WFC | 3.96 | 0.03 | − 0.07 | − 0.03 | 0.01 | − 0.06 | 0.06 | |||

| 8. Family well-being | 5.76 | 0.00 | 0.04 | − 0.07 | 0.06 | .17* | − 0.04 | − 0.09 | ||

| 9. Voice | 4.87 | − .17* | − 0.01 | − 0.04 | − 0.08 | 0.08 | − 0.01 | 0.03 | .20* | |

| 10. Segmentation preference | 5.60 | .15* | 0.09 | − 0.09 | − 0.04 | 0.06 | − 0.01 | 0.05 | .23* | − 0.01 |

*p < .05

Hypothesis Testing

To test the moderated mediation model, we used SPSS PROCESS add-on based on Preacher et al. (2007). Following the recommendation by Hayes (2012), we used bootstrapping technique with a sample size of 10,000 to test for indirect effect and the conditional indirect effect (moderated mediation effect).

To test hypotheses 1 to 3, we adopted model 4 in PROCESS. The result (see Table 2) showed that work-to-family conflict was significantly associated with perception of family well-being, b = − 0.08 (se = 0.04), p < 0.05. Thus, hypothesis 1 was supported. Meanwhile, supporting hypothesis 2, family well-being was significantly associated with voice behavior, b = 0.21 (se = 0.06), p < 0.01. Furthermore, the unconditional indirect effect of WFC on voice through family well-being was also significant, b = − 0.02, 95% bias-corrected CI = (− 0.04, − 0.0002). Therefore, hypothesis 3 was also supported.

Table 2.

Study 1 regression result

| Family well-being | Voice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| b | se | b | se | b | se | b | se | |

| Constant | 4.86* | 0.32 | 5.76* | 0.06 | 3.82* | 0.44 | 3.66* | 0.34 |

| Work-to-family conflict (WFC) | − 0.08* | 0.04 | − 0.08* | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| Segmentation preference (SP) | .22* | 0.05 | 0.22* | 0.05 | − .06* | 0.05 | − 0.07 | 0.05 |

| Family well-being | .21* | 0.06 | .21* | 0.06 | ||||

| WFC*SP | 0.01 | 0.03 | − 0.02 | 0.04 | ||||

| Indirect effect | Index of moderated mediation | |||||||

| − 0.02 | ||||||||

| 95% CI = (− .04, − .001) | 95% CI = (− .02,.02) | |||||||

WFC and SP were mean centered in the regression models 2 and 4

*p < .05

To test hypothesis 4, we adopted model 8 in PROCESS, also with a bootstrapping sample of 10,000 to calculate the confidence interval of the conditional indirect effect. Before the analysis, WFC and segmentation preference was mean-centered. The result (see Table 2) showed that the interaction between work-to-family conflict and segmentation preference was not significant in predicting family well-being, b = 0.01 (se = 0.03), p = 0.85. Furthermore, the index of moderated mediation = 0.001, 95% bias-corrected CI = (− 0.02, 0.02). Therefore, hypothesis 4 was not supported.

Discussion

Although study 1 did not provide sufficient support for all of our hypotheses, it did provide a lot of useful insights. First, supporting hypotheses 1 to 3, the result showed that WFC was negatively associated with family well-being, and family well-being was positively associated with subsequent voice behavior. However, in this study, workers’ segmentation preference was not found to moderate the indirect effect between work-to-family conflict and voice behaviors through family well-being. We suspect that the primary reason is that in this sample, participants tended to have rather high levels of segmentation preference (M = 5.60, SD = 1.20). As a result, there may not be enough variance in the sample to properly detect the moderation effect, especially when the moderation effect may not potentially be evenly present in the entire spectrum of segmentation preference (Bauer & Curran, 2005). Another reason could be that the 2-week interval may be a bit too long to detect the proposed mechanisms since the effect could be more fleeting, as evidenced by research employing the experience sampling method (e.g., Ilies, Scott, & Judge, 2006; Shockley & Allen, 2013). Yet another reason could be that the online study setting provided a weak environment where participants’ attention level was low. Furthermore, all three surveys were self-report, which could give rise to common method bias (Podsakoff et al., 2003), making the result a little bit hard to dissect. Given the limitations of the first study, we designed study 2 to conduct another 3-wave time-lagged field survey that avoids some of the pitfalls of study 1, while strengthening the external validity of the empirical tests.

Study 2

Research Design and Sample

In this study, we recruited participants who are married employees with direct supervisors from four companies in the manufacturing and real estate industry in southern China. The HR department of each company helped recruit participants, and distribute and collect surveys. To mitigate the potential effect of common method bias (Podsakoff, et al., 2003), again we adopted a temporally lagged survey design and divided the data collection into three waves, but with 10 days between phases (instead of 14 days as in study 1). We chose 10 days between surveys to mitigate the memory and spillover effect (Podsakoff et al., 2003), and to adequately capture the potentially fleeting effect of work-to-family conflicts occurring in the participants’ families. Similar to study 1, in wave 1, we collected data on participants’ WFC and segmentation preference; in wave 2, we surveyed their evaluation of family well-being; and in wave 3, we surveyed the supervisors of those employees who completed both wave 1 and 2, regarding their voice behavior.

In the first wave, we distributed 374 surveys and got back 325 effective responses (86.9% response rate). In the second wave, 294 out of the 325 participants filled out the survey (90.5% response rate). In the third phase, 209 supervisors responded to our survey (71.1% response rate). The final sample consists of those 209 participants and their corresponding supervisors. A percentage of 41.15% of the sample comprised of females. A percentage of 43.06% of participants fell between ages 21 to 30, and 30.62 fell between ages 31 to 40 (due to privacy concerns, we could only get data about participants’ age bracket, not specific age).

Measurement

For each of the measurement scales we used, we translated them from English to Chinese to suit the reading and language habits of the participants. Furthermore, we adopted a 5-point Likert scale for each measurement. The items are exactly the same as in study 1, except for the measurement for family well-being, for which we modified the scale for Chinese participants.

WFC

WFC was measured with 4 items based on Kopelman et al. (1983). Sample items include “my work takes up time that I'd like to spend with my family” and “my job makes it difficult to be the kind of spouse or parent I’d like to be.” The scale showed good overall reliability, with Cronbach alpha = 0.80.

Segmentation Preference

Segmentation preference was measured with 4 items based on Kreiner (2006). Sample items include “I don’t like work issues creeping into my home life” and “I like to be able to leave work behind when I go home.” The scale showed good overall reliability, with Cronbach alpha = 0.83.

Family Well-Being

Family well-being was measured based on a modified version of the Chinese Family Assessment Instrument by Mellor et al. (2014). The scale consists of 12 items, capturing three core dimensions of family well-being: positive family functioning (sample items include “family members give emotional support to each other”), negative family functioning (sample items include “family members are constantly fighting”), and tolerance among family members (sample items include “family members are patient with each other”). The scale showed good overall reliability, with Cronbach alpha = 0.93.

Voice Behavior

Voice behavior is measured with 9 items from Liu et al. (2010). Sample items include “this person speaks to the supervisor with new ideas for projects or changes in procedures” and “this person develops and makes recommendations to the supervisor concerning issues that affect our organization.” The scale showed good overall reliability, with Cronbach alpha = 0.94.

Control Variables

Similar to study 1, we controlled for participants’ gender and age. Moreover, as all surveyed employees were married, marital status was not relevant anymore. Instead, we controlled for the number of children participants had while filling out the survey, recognizing the time and resources required for childcare (Boyar et al., 2008).

Result

The data analytical approach was similar to study 1. We first conducted confirmatory factor analysis in AMOS to ensure the discriminatory validity of the constructs we use in the survey. After obtaining satisfactory results, we moved on to hypothesis testing via PROCESS in SPSS, with bootstrapping technic and confidence intervals to evaluate the indirect and conditional indirect effects (Hayes, 2012).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To establish the discriminatory validity across the main measurement scales, we conducted a CFA test using AMOS 22.0. The resulting 4-factor solution shows good fit, RMSEA = 0.07, IFI = 0.96, CFI = 0.96. Furthermore, we tested the fit of alternative models and conducted the model comparison test to determine the model superiority. Results showed that the proposed model fits better than any other factor solution. Therefore, we retained the 4-factor solution and proceeded with subsequent analysis.

Descriptive Statistics

Table 3 shows the descriptive statistics and the variable correlations. In line with the predictions, work-to-family conflict was negatively associated with family well-being (r = − 0.18, p < 0.05), and family well-being was positively associated with employee voice (r = 0.23, p < 0.05). The correlation between work-to-family conflict and voice was not significant (r = − 0.08, ns). Regarding the control variables, gender, age, education, and the number of children did not significantly correlate with model variables. Again, we tested the model with and without the control variables, and both resulted in identical patterns. To maintain the model parsimony (Becker, 2005), in the following, we only show results with the model variables.

Table 3.

Study 2 descriptive statistics

| Mean | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Work-to-family conflict | 2.51 | ||||||

| 2. Segmentation preference | 3.60 | 0.11 | |||||

| 3. Family well-being | 4.18 | − 0.18* | 0.06 | ||||

| 4. Voice | 3.47 | − 0.08 | − 0.03 | 0.23* | |||

| 5. Gender | 0.51 | − 0.05 | − 0.10 | − 0.07 | − 0.05 | ||

| 6. Age | 2.88 | − 0.04 | − 0.03 | − 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.06 | |

| 7. Number of children | 1.15 | 0.06 | − 0.04 | − 0.04 | 0.00 | − 0.05 | 0.49* |

*p < .05

Hypothesis Testing

To test the moderated mediation model, we used SPSS PROCESS macro based on Preacher et al. (2007). Following the recommendation by Hayes (2012), we used bootstrapping technique with a sample size of 10,000.

To test hypotheses 1 to 3, we adopted model 4 in PROCESS. The result (see Table 4) showed that work-to-family conflict was significantly associated with the perception of family well-being, b = − 0.13, p < 0.01. Also, family well-being was significantly associated with voice behavior, b = 0.29, p < 0.01. Furthermore, the indirect effect of work-to-family conflict on voice through family well-being was significant, b = − 0.04, 95% bias-corrected CI = (− 0.09, − 0.002). Therefore, hypotheses 1 to 3 were supported.

Table 4.

Study 2 regression result

| Family well-being | Voice | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| b | se | b | se | b | se | b | se | |

| Constant | 4.32* | 0.19 | 4.20* | 0.03 | 2.50* | 0.48 | 2.49* | 0.40 |

| Work-to-family conflict (WFC) | − 0.13* | 0.05 | − 0.12* | 0.05 | − 0.05 | 0.07 | − 0.04 | 0.07 |

| Segmentation preference (SP) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | − .03 | 0.06 | − 0.04* | 0.06 |

| Family well-being | .29* | 0.09 | 0.24* | 0.09 | ||||

| WFC*SP | − 0.17* | 0.06 | − 0.23* | 0.08 | ||||

| Indirect effect | Index of moderated mediation | |||||||

| − 0.04 | ||||||||

| 95% CI = (− .09, − .002) | 95% CI = (− .01, − 0.001) | |||||||

WFC and SP were mean centered in the regression models 2 and 4

*p < .05

To test the moderated mediation effect in hypothesis 4, we again adopted model 8 in SPSS PROCESS with bootstrapping sample of 10,000. Like in study 1, we also mean-centered WFC and segmentation preference. The result (see Table 4) showed that the interaction between work-to-family conflict and segmentation preference was significant in predicting family well-being, b = − 0.17, p = 0.01. Furthermore, the index of moderated mediation was significant, 95% bias-corrected CI = (− 0.12, − 0.004). Probing of the conditional indirect effect at 1 SD at, above, and below the mean level of segmentation preference demonstrated that the conditional indirect effect increased as the segmentation preference increased, consistent with our hypothesis. Moreover, the indirect effect was only significant among those with high-level (above 1 SD) segmentation preferences, and not among those with low or mid-levels of segmentation preference (see Table 4). Therefore, hypothesis 4 was supported. Table 5 shows the comparison of conditional indirect effects.

Table 5.

Study 2 conditional indirect effect

| Mediator: family well-being | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Segmentation preference | Indirect effect | SE (boot) | LLCI (boot) | ULCI (boot) | |

| Low segmentation | − 0.72 | − 0.0000 | 0.02 | − 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Mid segmentation | 0.00 | − 0.03 | 0.02 | − 0.07 | 0.0001 |

| High segmentation | 0.72 | − 0.06 | 0.03 | − 0.13 | − 0.01 |

| Index of moderated mediation | |||||

| Mediator | Index of moderated mediation | SE (boot) | LLCI (boot) | ULCI (boot) | |

| Family well-being | − 0.04 | 0.03 | − 0.10 | − 0.001 | |

Signficant indirect effects and significance of index of moderated mediation are marked Bold

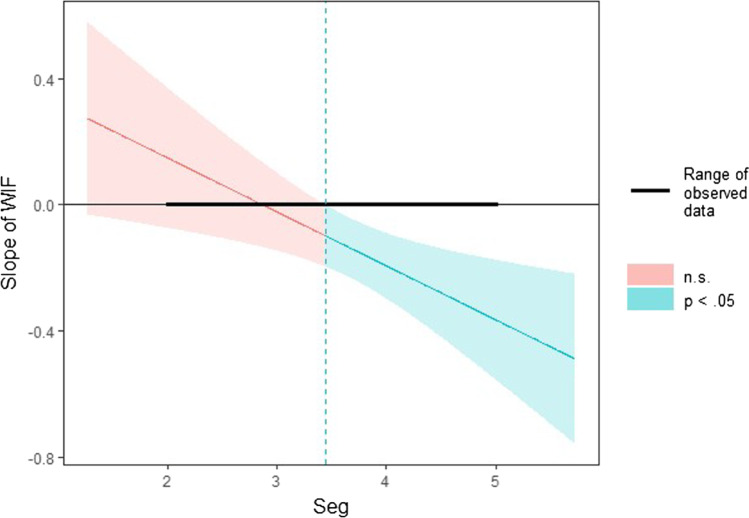

To further demonstrate the relationship between the moderator levels and the associated conditional indirect effects, we utilized the Johnson-Neyman (J-N) plot (Johnson & Neyman, 1936) to visualize the conditional indirect effects across the available range of segmentation preferences (shown in Fig. 2). The plot illustrates the confidence intervals for all conditional indirect effects, resulting in a lower-bound curve and upper-bound curve surrounding the value of conditional indirect effects. Previous research advocated for the J-N technique as a complementary alternative to the traditional “pick-a-point” approach to demonstrate moderating effects (e.g., Bauer & Curran, 2005; Hayes & Matthes, 2009), especially when the moderator is a continuous variable and the choice of moderator values to probe conditional indirect effects is largely arbitrary (e.g., 1 SD above and below the mean; Spiller et al., 2013). Figure 2 shows not only the value of conditional indirect effect decreasing (and gradually turning negative, as predicted) as segmentation preference is higher but also the range of segmentation preference levels where the conditional indirect effects are significant (blue shade area in the plot; when the CIs do not include 0), which in this study are values close to and above the mean level. As the segmentation level goes down, the conditional indirect effect becomes smaller and gradually turns non-significant. Therefore, the Johnson-Neyman plot provides additional support for hypothesis 4.

Fig. 2.

Johnson-Neyman plot of regions of significance

Discussion

In study 2, using field surveys administered by the organization’s HR personnel, we were able to test the proposed model in a stronger environment than in study 1. Moreover, we shortened the intervals between surveys from 2 weeks to 10 days to better capture the potentially transient effect of work-to-family conflict. We were also able to have other-rated measures of voice behavior, which strengthened the robustness of the model. The result from study 2 supported our theoretical model. Particularly, the result showed the moderating role of segmentation preference in the indirect effect of WFC on voice behavior through family well-being. We believe that a broader range of high and low scores of segmentation preference in the sample helped illustrate the moderation effect. Taken together, study 2 allowed us to test the model in a better way, extended the findings from study 1, and the results were strengthened.

General Discussion

Decades of research into the phenomenon of work-family conflict yielded a rather consistent picture of its broad range of antecedents (Allen et al., 2020; Byron, 2005; Michel et al., 2011) and outcomes (Allen et al., 2000; Amstad et al., 2011). However, much of the insights were gained through the predominant worker role-centric research lens which focused on the focal workers’ role conflicts as the catalyst of WFC. Yet, one largely neglected area of inquiry is the role of family, specifically various family characteristics that could also factor into the consideration. Taking a family system perspective (Hill, 1958; Satir, 1988) born out of the family psychology and sociology literature, we offer an alternative theoretical framework based on the Contextual Model of Family Stress (Boss, 2002; Boss et al., 2016) to examine the mechanisms of work-family conflict and its impact on workers’ on-the-job behaviors. Through this framework, we were able to position the family system as the central narrative (as opposed to individuals’ own thoughts and feelings as the central focal lens) and utilize the interaction between the focal workers and their family system to explain how work-family conflict disrupts the equilibrium of the family system, causing strains in the system that lower the family’s well-being, and how the system then casts strain back onto focal workers and reduce their voice behavior. This central mechanism was supported across two studies. Furthermore, study 2 also demonstrated the importance of individual perception and beliefs, high segmentation preference in this case, in exacerbating the reactions to WFC regarding its impact on family well-being.

The result across the two studies supports the theoretical underpinning of CMFS, and advances CMFS as a promising alternative framework for WFC research. Traditionally, the theorizing of WFC primarily resides on the individual and the relational level (e.g., between couples). Expanding on the scope of research and guided by CMFS, we specify that such disturbances also impact the family system, above and beyond the individual members in the family. By demonstrating that the impact of the disturbance events could transmit through a multi-dimensional construct of family well-being, we demonstrate a new way to dissect WFC which is complementary to the current individual and relational approach.

Furthermore, the moderated mediation effect shows the importance of individual interpretation of the disturbance events, which underlines the complexity of the family coping under CMFS. CMFS posits that, although the disturbances affect all family members, the resulting family dynamic does not impact each family member equally in the same way. The interpretation of disturbances by family members is critical in the interpretation and the reaction to the disturbance. In this case, the preference for segmentation taps into workers’ expectations regarding their ideal work-family dynamic, which influences their appreciation and evaluation of the disturbance events. The result supports these key propositions of CMFS and offers more nuances into the discussion of WFC and its negative yet non-universal effects.

Given the lack of detailed attention given to the family context in managerial work-family interface research, it could prove very fruitful to shift more attention to this important domain. Doing so could also complement the prevailing logic of role conflict and boundary management (Byron, 2005; Edwards & Rothbard, 2000) in dissecting the work-family interface, and provide opportunities to connect on a much deeper level the work domain and the family domain. We detail some key theoretical and practical implications below.

Theoretical Implication

In this paper, we explore a well-researched question—that is, how work-to-family conflict affects work-related behaviors—from a new angle. The study offered theoretical contribution in three main areas. First and foremost, we established the relevance and usefulness of the Contextual Model of Family Stress (Boss et al., 2016) in the inquiry of work-family interface, and a more comprehensive conceptualization and measurement of family well-being (Moller et al., 2014). This paper identified a previously largely neglected area in the work-family interface research, that is, the nature and role of family. Although contextual factors matter for the work-family interface (which, after all, is the interaction between two contexts), previous research devoted most attention to the work context, and the theorization of the family context has been surprisingly lacking in comparison (e.g. Allen et al., 2020; Amstad et al., 2011; Nohe et al., 2015). When family contexts are examined, it is often examined from an intra-personal, role conflict–based perspective from the focal employees, or the impact from and to the spouses (e.g., Westman & Etzion, 2005). Even a broader categorization of social support (e.g., French et al., 2018) does not quite capture the intricate dynamics within a family but focused mostly on overall family support or support from the spouses. At the same time, however, family is much more than the sum of the individual members and individual relationships, and the family as a layered system could impact individuals above and beyond the influences from family members in the family (Boss et al., 2016). Therefore, we cannot ignore the potential impact of the family system as we investigate the interference from work to family.

Moreover, this research also shows the relevance and promise of the CMFS in the continuing research of the work-family interface. To our knowledge, this research is among the first endeavors to adopt the CMFS theoretical lens to examine the work-family interface in management research. Given CMFS’s broad scope, the current research only utilized a very small part of the theory. We believe that further examination of the work-family interface could benefit tremendously by adopting this family-centered framework, which could help discover a host of important but previously ignored constructs.

For example, while family well-being spans across the family’s psychological context, it is only one of the internal contexts (Boss, 2002) and the family’s philosophical context also deserves scholarly attention. In CMFS, the philosophical context refers broadly to the values and beliefs within the family. As families went through the pandemic and economic turmoil in the last 2 years, family resilience (Walsh, 2003) could become a subject of great interest to researchers. Similarly, the political ideology of the family could also play an important role in shaping workers’ opinions and attitudes towards work and various workplace policies. Or, researchers could examine the impact of the structural context of the family on work-family interface, such as family composition (e.g., nuclear families versus multigenerational households) and structural change (e.g., newborn child, death, divorce). In particular, previous research on the work-family interface tends to focus on traditional nuclear families among heterosexual couples (either explicitly or implicitly). Yet, families of non-traditional couples (e.g., couples of LGBTQ population, childless families) or single parents may have different family dynamics (Moore & Stambolis-Ruhstorfer, 2013; Nomaguchi, 2012), thus members may experience different sets of WFC-related challenges.

Conceptualizing family as a dynamic system also allows for theorizing family coping and adjustment on the temporal dimension. For example, using the time-lagged survey method, we were only able to capture the snapshots of WFC and the family well-being in the short run. At the same time, the family system is not static but reacts to the disturbances such as WFC. Therefore, as time goes by, the impact on family well-being may bounce back due to adjustment or continue deteriorating due to maladaptation (Boss et al., 2016). Therefore, taking a longitudinal perspective may help gain insights into the family system characteristics that facilitate smooth adaptation. In this regard, one way is to explore the broader family external contexts, such as ethnical, cultural, economic, and historic backgrounds, and how these contextual factors could continuously shape and affect how families react to such disturbances. For example, a family from lower socioeconomic status may resort to extra work for survival, which could create more divisions within the family.

Furthermore, in this study, guided by the CMFS framework, we also adopted a more holistic conceptualization and measurement of family well-being. This is significant since most management studies on family well-being approached the topic from the perspective of domain satisfaction, that is, how satisfied one is with the home life (e.g., Judge et al., 2006; Wilson et al., 2018), or how well the family responsibilities are fulfilled (Frone et al., 1997). The former lacks the nuances by taking a global measure (mostly adapted from the general job satisfaction measurement), while the latter represents a rather narrow view of family functions. Therefore, to properly study the family system and its various components, measurements with better specification and precision are helpful. The family well-being measures adopted in this study (Mellor et al., 2014; Noor et al., 2014) aim to contribute in this regard, by specifying the more concrete aspects of family life, particularly regarding the family’s structural and psychological contexts, such as positive functioning, negative functioning, and tolerance towards one another.

Given the lack of previous scholarly attention to these family-oriented constructs, future research could benefit by developing and adopting more theory-driven, nuanced measures that capture various aspects of the family system. Even the measurement of family well-being could be further specified. For example, the current measurement captures two dimensions of family functioning (i.e., positive and negative), while the concept of family functioning also entails sub-concepts such as trust, conflict, and care, each of which may be worth examining alone and thus could be measured separately. Similarly, the current measurement of family well-being also captures the idea of tolerance among family members. However, we could further delineate different aspects of tolerance, such as tolerance regarding personal habits and that towards political views, which might not always be the same and might engender different family dynamics. Moreover, although the current multifaceted conceptualization of family well-being is an improvement over the general, more generic one, it is by no means the only viable or the best conceptualization. Future research endeavors to revise and enrich the concept could also prove fruitful.

Finally, this study also represents one of the first inquiries into the link between WFC and voice behavior. Previous research on employees’ voice behavior heavily focused on the work context and individual characteristics as antecedents (Chamberlin et al., 2017; Morrison, 2014). Family context, in comparison, was largely ignored. As contextual performance is increasingly valued by employers (e.g., Bolino & Turnley, 2005), and voice behavior is among the more challenging aspects of contextual performance (Graham & Van Dyne, 2006), research on voice behavior becomes increasingly important (Morrison, 2014). As such, shifting the focus from work to family context may prove a fruitful avenue to continue exploring the contextual factors facilitating employee voice behavior. For example, the family environment (e.g., the philosophical context) for speaking up may shape the perception and preference for speaking up at the workplace, above and beyond all workplace factors. Or, family social networks and related family activities may determine the opportunities for practicing voicing one’s opinion. Furthermore, significant family experiences may also affect the content of employee voice behavior as well. For example, having multiple young children may propel employees to advocate for flexible work schedules, while experiencing or witnessing substance abuse at home may bias the employees’ preference on drug policy in the organization. In sum, we believe that by focusing on the family context, particularly being guided by a holistic theory on the family system such as CMFS may provide abundant opportunities to advance research in voice behavior.

Managerial Implication

As the current pandemic illustrates vividly for us, work-family conflicts affect the well-being of everyone. Increasingly, we learn the negative effects of work-family conflict, both inside and outside of the workplaces (Amstad et al., 2011). This paper demonstrates how the family system may be a separate mechanism beyond workers, their spouses, and the workplace that influences the workers’ performance, such as voice behavior. Therefore, more than ever, it is of significant managerial interest to reduce the work-life conflict of employees. Previous research has offered numerous ways for employers to offer work-family support to employees (Masterson et al., 2021). A key implication from this study is that, when designing these policies and procedures to ease employees’ WFC, it is important to consider the employees’ specific family contexts, since these contextual factors from the family system affect employees’ performance. It requires that managers recognize the relevance and impact of the family system so that they could better understand the potential family issues of their employees and better assist them. For example, the birth of a child may not only mean that the employee may need more time at home, or that it may distract the employee from work, but also that the new addition to the family could change the family’s bonds between members and the family values, which could affect workers’ career aspirations.

Moreover, when designing work-family policies, it also helps managers understand the complexity and idiosyncrasy of each employee’s respective family system, so that they could accommodate more family situations and even customize the policies according to the employees’ unique family backgrounds. The one-size-fits-all approach to work-family policies may not be the best approach. Instead, policies with built-in flexibility and consideration of unique family contexts may satisfy more employees. For example, if money is a big concern versus time, organizations could have policies to trade holiday time for more pay, or vice versa.

At the same time, this paper also highlights that employees may appraise the same level of WFC differently, depending on their own segmentation preference. It seems that those who do not place a high value on work-family segmentation may be affected less by WFC. It may have implications for the recruitment and selection process. For example, if managers are putting together a special project team for an intense work period (such as the auditing jobs that have busy seasons), they may want to ask about employees’ own segmentation preferences, so that managers may anticipate the bigger challenge of WFC for certain employees, and thus allocating tasks or assigning roles accordingly. Furthermore, the impact of individual differences such as segmentation preference also highlights the importance of understanding employees’ family situation as well as their relations to the family in management decisions and approaches.

Limitation and Future Research Directions

As with every other paper, this paper is not without limitations. First of all, in the study, we controlled for gender, and the number of children (in study 2) and did not theorize the specific interaction between gender and the family system. As a result, we were not able to dissect the influence of gender or more nuanced family status on the link between WFC and the family system. Indeed, gender and family characteristics are considered important moderating factors in the discussion of WFC (e.g., Ford et al., 2007). Particularly, given that a recent meta-analysis (Shockley et al., 2017) found little association between gender and WFC, it is worth considering whether the family system may be the potentially moderating factor. That is, although all workers may experience the WFC similarly when it occurs, males and females may interact with the family’s structure in a different fashion. For example, they may occupy different roles in the family system, and they may perceive the same events in the family differently (Boss et al., 2016). Or, the family’s larger context, such as social, economic, and historic backgrounds, may also be relevant in delineating the gender-specific effects.

Moreover, as CMFS indicates, there are many contextual properties in the family system that could have bearing on the family well-being. We were able to control for the number of children and the marital status in the second study, yet we were not able to control for more nuanced structural properties, such as whether they live with elderly family members who need extensive care, whether the couples contribute equally in terms of financial resources, or whether they live close to or interact frequently with extended families. Future research could incorporate more family system components into the study or implement a more rigorous control to better specify the relationships.

Furthermore, in this study, we only surveyed the focal employees themselves for evaluation of WFC and the family well-being and did not explore or specify other family members’ input. In this regard, we departed from previous research that asked about workers’ own global evaluation of family satisfaction, by asking workers about specific aspects of their family structural and psychological contexts. More importantly, by adopting a referent-shift style of survey questions (i.e., the question items are asking about the “family,” rather than the items that start with “I feel” or “I am”), we tried to shift the workers’ focus to the family when answering the questions. Previous research indicates that shifting the referent point, even at the individual level, creates conceptually different constructs from the self-centered question items (Baltes et al., 2009; Wallace et al., 2016). To further reduce the risk of common method bias, we also temporally separated the measures of WFC, family well-being, and voice behavior.

We adopted this approach with abundant methodological considerations. In the CMFS framework, the family members’ perception and interpretation of the stressor are key to understanding their reactions to and the impact of the stressors (Boss et al., 2016). Therefore, although the system may be a higher-level phenomenon, the individual perceptions of the phenomenon are still critical to the actual lived experiences and mediate the influence of the system on the individuals. Furthermore, French and colleagues (2018) also illustrated that the social support perceptions have a stronger relationship to the workers’ experience of WFC than actual support behaviors.

Nonetheless, as CMFS posits, the family system takes input from but resides beyond individual family members. As such, a multi-level research approach that gathers data from multiple family members may be helpful in systematically examining the family dynamic. Yet, the construct of family well-being as conceptualized lacks theoretical ground to be elevated to a higher-level variable for measurement. For example, Klein and Kozlowski (2000) emphasized internal agreement as a prerequisite for creating high-level variables. In this regard, in CMFS (Boss et al., 2016), family members are not assumed to agree on their perceptions of the characteristics of the family system. On the contrary, the potential differences between family members’ perceptions are the key to understanding the family dynamic. Some empirical findings also suggest that family members may not always agree (Ilies et al., 2020; Mellor et al., 2014). Therefore, the internal agreement between family members may not exist or be as meaningful.

As such, we believe that future research should first try to crystalize the mechanism of the family system formation. Knowing so would shed light on the most appropriate way to operationalize the family system constructs and measure the contextual factors with more precision. Therefore, a qualitative approach that could help dive deep into the different perspectives of family members and their mutual influences could be enlightening, especially when disagreements between family members are common.

Finally, in this study, we theorized about the effect of work-to-family conflict on general voice behaviors at the workplace. However, voice behaviors may have different targets, and one could argue that the WFC could have different effects on voice behaviors, depending on whether the target of the voice is upward voice lateral (Morrison, 2014). Perhaps upward voice consumes more resources than lateral (Ng & Feldman, 2012), and the detrimental effect caused by the work-to-family conflict is larger. Future research could test the relationships with more specific voice scales.

Conclusion

Work-family conflict has increasingly become one of the prominent challenges of modern-day work. In this study, we adopt the Contextual Model of Family Stress Theory to explain how work-family conflict could negatively affect family well-being, which then contributes to employees’ voice behavior. Moreover, in this study, we argue that a person’s work-family segmentation preference will shape the person’s experience of the conflict and that the preference moderates the effect of work-family conflict on employee voice behavior. These findings open up new avenues for future research on the impact of work-family conflict through more family system dimensions as well as more family-centric boundary conditions.

Funding

This research was in part supported by a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Foundation of the Ministry of Education in China (No. 18YJA630062), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (No. 2020A1515010507).

Footnotes

The measurement of family demand also suffers from similar limitations. Some studies of family demand did use objective measures, such as the size of the family (e.g., Masuda, Sortheix, Beham & Naidoo, 2019), the number of children or dependents (e.g., Boyar, Maertz, Mosley, & Carr, 2008), or the number of hours spent at work/home (e.g., Voydanoff, 1988). Nonetheless, they are often examined as proxies for individual time-based demands, and undertheorized as stand-alone family characteristics (e.g., the meaning of the higher number of children in the family could mean higher demands, but it could also mean more joy and support).

Liu, Kwan & Wang (2012) tested a model of positive spillover from work to family and voice behavior. However, the guiding framework from their study was social exchange theory between mentors and protégé, with the individual’s satisfaction and reciprocity as the conduit of the relationships. The family context’s unique characteristics were not specified.

The philosophical context emphasizes on the shared value among family members, which tend to be more stable than the other two, and less susceptible to more mundane, chronic stressors such as WFC.

They actually theorized how WFC may affect the whole family, yet they focused on the couple as a proxy for the family.

The families may become more resilient over certain challenges in the long run, by functionally adapting and making adjustments (Boss et al., 2016). However, in the immediate aftermath, such remedies may not be readily available.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Allen TD, Herst DE, Bruck CS, Sutton M. Consequences associated with work-to-family conflict: A review and agenda for future research. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2000;5(2):278–308. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.5.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD, Cho E, Meier LL. Work–family boundary dynamics. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior. 2014;1:99–121. [Google Scholar]

- Allen TD, French KA, Dumani S, Shockley KM. A cross-national meta-analytic examination of predictors and outcomes associated with work–family conflict. Journal of Applied Psychology. 2020;105(6):539–576. doi: 10.1037/apl0000442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amstad FT, Meier LL, Fasel U, Elfering A, Semmer NK. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 2011;16(2):151–169. doi: 10.1037/a0022170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashforth BE, Kreiner GE, Fugate M. All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review. 2000;25(3):472–491. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes BB, Zhdanova LS, Parker CP. Psychological climate: A comparison of organizational and individual level referents. Human Relations. 2009;62(5):669–700. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Curran PJ. Probing interactions in fixed and multilevel regression: Inferential and graphical techniques. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2005;40(3):373–400. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr4003_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister RF, Vohs KD, Tice DM. The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16(6):351–355. [Google Scholar]