Abstract

Purpose

To describe postdischarge opioid dispensing after Cesarean delivery (CD) in 49 hospitals in British Columbia (BC) and assess opportunities for opioid stewardship.

Methods

Using the BC Ministry of Health’s Hospital Discharge Abstract Database, we linked 135,725 CDs performed in 2004–2016 and 30,919 CDs performed in 2017–2019 (length of stay ≤ four days) by deidentified Personal Health Numbers to data on medications dispensed from all BC community pharmacies (PharmaNet). We excluded patients with cancer and those to whom opioids have been dispensed in the year before. We measured trends in annual percentages of patients dispensed opioids within seven days (opioid rate), with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), stratified by hospital and opioid type, adjusted for length of stay, and for autocorrelation within hospital using generalized linear modeling.

Results

The opioid dispensation rate dropped from 31% (95% CI, 30 to 33) in 2004 to 16% (95% CI, 15 to 17) in 2016, where it remained through 2019. Five hospitals showed steep reductions from over 40% to under 10% within two to three years, but in most hospitals the opioid dispensation rate decreased slowly—11 had little reduction and three showed increases. Codeine dispensing dropped from 31% in 2004–2008 by 4% per year, while tramadol and hydromorphone dispensing rose. After 2015, rates were stable (hydromorphone, 8%; tramadol, 6%; codeine, 3%; and oxycodone, 0.5%).

Conclusion

After Health Canada’s 2008 warning against codeine use by breastfeeding mothers, post-CD opioid dispensing declined disjointedly across BC hospitals. Rates did not decrease further after the opioid overdose epidemic was declared a public health emergency in BC in 2016. The present study highlights opportunities for quality improvement and opioid stewardship through monitoring using administrative databases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12630-022-02271-8.

Keywords: Cesarean delivery, epidemiology, opioids, postoperative analgesia, prescription dispensing

Résumé

Objectif

Décrire la délivrance d’opioïdes après le congé après un accouchement par césarienne dans 49 hôpitaux de la Colombie-Britannique (C.-B.) et évaluer les occasions de régulation des opioïdes.

Méthode

À l’aide de la base de données sur les congés des patients du ministère de la Santé de la Colombie-Britannique, nous avons relié 135 725 accouchements par césarienne réalisés en 2004-2016 et 30 919 accouchements par césarienne réalisés en 2017-2019 (durée de séjour ≤ quatre jours) en utilisant les numéros de carte santé personnels dépersonnalisés aux données sur les médicaments délivrés par toutes les pharmacies communautaires de la Colombie-Britannique (PharmaNet). Nous avons exclu les patientes atteintes de cancer et celles à qui des opioïdes avaient été délivrés l’année précédente. À l’aide d’une modélisation linéaire généralisée, nous avons mesuré les tendances en pourcentages annuels de patientes ayant reçu des opioïdes dans les sept jours (taux d’opioïdes), avec des intervalles de confiance (IC) à 95 %, stratifiés par hôpital et par type d’opioïdes, ajustés en fonction de la durée de séjour et des autocorrélations entre des taux de chaque hôpital.

Résultats

Le taux de délivrance d’opioïdes est passé de 31 % (IC 95 %, 30 à 33) en 2004 à 16 % (IC 95 %, 15 à 17) en 2016, où il est resté jusqu’en 2019. Cinq hôpitaux ont montré des réductions importantes, passant de plus de 40 % à moins de 10 % en deux à trois ans, mais dans la plupart des hôpitaux, le taux de délivrance d’opioïdes a diminué lentement – 11 ont affiché une faible réduction et trois ont montré des augmentations. La délivrance de codéine a diminué de 4 % par année, à partir de 31 % en 2004-2008, tandis que la délivrance de tramadol et d’hydromorphone a augmenté. Après 2015, les taux étaient stables (hydromorphone, 8 %; tramadol, 6 %; codéine, 3 %; et oxycodone, 0,5 %).

Conclusion

Suite à la mise en garde de Santé Canada en 2008 contre la consommation de codéine par les mères qui allaitent, la délivrance d’opioïdes post-césarienne a diminué de façon inconstante dans les hôpitaux de Colombie-Britannique. Les taux n’ont pas diminué davantage après que l’épidémie de surdose d’opioïdes a été déclarée urgence de santé publique en Colombie-Britannique en 2016. La présente étude met en évidence les possibilités d’amélioration de la qualité et de régulation des opioïdes en procédant à une surveillance via les bases de données administratives.

The devastating impact of the opioid epidemic, having claimed more than 9,000 Canadian lives since 2016,1 has prompted a national emergency and exposed systemic deficiencies in the Canadian healthcare system.2 In North America, aggressive marketing for synthetic opioids such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, and fentanyl has been identified as an important contributor to physicians’ overprescribing of opioids for postoperative pain3 and an increase in opioid-related toxicity deaths across Canada.4

Cesarean delivery is the most common inpatient surgery performed in Canada, with more than 105,000 procedures in 2018–2019 nationwide.5 The overall Cesarean delivery in Canada rate is approximately 29% of all childbirths; the province of British Columbia (BC) has the highest rate at 37%.6 Many factors have influenced post-Cesarean delivery opioid prescribing in Canada, including numerous quality improvements promoting nonopioid alternatives and minimizing unnecessary opioid use after Cesarean delivery.7–12 There have also been key incidents, such as a 2006 case report and subsequent 2008 Health Canada recommendation for safety of codeine during breastfeeding, which was followed by a drop in codeine prescribing and a rise in the use of other opioids post partum in BC.13,14 There have been more recent specific recommendations in North America against certain opioids such as the 2018/2019 US Food and Drug Administration and American Society of Anesthesiologists’ recommendations against tramadol for breastfeeding patients, the ramifications of which have yet to be studied.15,16 As well, a recent study by Reed et al. in the USA showed that variations in post-Cesarean analgesia were largely influenced by hospital, rather than by patient characteristics or current recommendations.17 Location of practice and physician level of experience have also been posited to impact opioid prescribing in Canadian obstetric delivery.18 Moreover, multiple studies have shown that opioids prescribed in this manner often exceed patients’ needs.12,19,20

The Surgical Quality Outcome Reports (SQOR) study and the SQOR Extension study, which aimed to show the feasibility of rapid monitoring of surgical outcomes using administrative data, provided an opportunity to study the variation in opioid dispensing rates among hospital types and locations after Cesarean delivery. Both studies had access to all records of opioids dispensed from community pharmacies in BC, in contrast, for example, to an Ontario study that was not able to track trends in tramadol prescribing, because tramadol was not a controlled substance.21 We sought to identify patterns of variation among hospitals, by type or location, that might guide strategies for quality improvement, such as feedback of performance metrics to surgeons.

Methods

Data sources

We conducted a retrospective historical cohort analysis of parturients undergoing Cesarean delivery between 2004 and 2019 in BC. The BC Ministry of Health’s administrative data were initially extracted by PopulationData BC as a batch covering 2004–2016 for the SQOR study. The observation window was extended to include 2017–2019 via the Ministry’s SQOR Extension study covering 2004–2019, with direct access to the Ministry’s continuously updated data warehouse called Healthideas. Both studies were approved by The University of British Columbia’s Clinical Research Ethics Board (Vancouver, BC, Canada; #H14-01717 and #H20-00340). Data were not linkable between the SQOR and SQOR Extension studies.

We used Cesarean delivery codes, 5.MD.60.xx in the Canadian Classification of Health Interventions (CCI) codes,22 (Electronic Supplementary Materials [ESM] eTable 1) to extract records of hospital discharge abstract data (DAD)23 from all BC hospitals, from 2004 to 2016 (to 2019 in the SQOR Extension study). Using person-specific deidentified study identification numbers based on BC’s Personal Health Number (which differed between SQOR and SQOR Extension studies), we linked the DAD extracts with records of prescription opioid (ESM eTable 2) dispensing from BC PharmaNet24 (the province’s central data system for all community pharmacies, which covers dispensations to all people except those in acute care hospitals). For demographic variables and exclusions, DAD and PharmaNet were also linked to diagnoses in BC Medical Services Plan (MSP)25 billings from physicians, and to demographics and medical plan enrollment data in a population registry called the “consolidation file.”26

Selection and description of participants

Both the SQOR and SQOR Extension studies excluded patients who had been dispensed opioids or had a diagnosis code for cancer (ESM eTable 3) during the year before their Cesarean deliveries, or who were less than 14 years of age, or discharged five or more days after delivery. The SQOR study excluded second Cesarean deliveries in any single calendar year, while SQOR Extension was limited to first Cesarean deliveries in the entire observation window, from 2004 to 2019. Perfect replication of SQOR by SQOR Extension was not possible because the Ministry terminated SQOR Extension early to fund COVID-19 studies.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the percentage of patients dispensed any opioid within seven days after discharge from hospital. Secondary outcomes were opioid type and the quantity of opioid first dispensed (number of tablets). We stratified opioids by the most common types (including combinations with pain medications, such as acetaminophen-codeine, but excluding cough medicines): codeine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, tramadol, and other.

Analysis

We contrasted annual percentages by charting them with their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and calculating percent differences, or differences between differences, with their 95% CIs. The mean opioid dispensing rate differences between the SQOR cohort and SQOR Extension cohort in the 2015–2016 period were used to calculate adjusted rates in the 2017–2019 period, representing expected rates in the SQOR cohort (shown by * in Figs). We grouped hospitals by type using the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) hospital peer group criteria27—Teaching Hospitals, Community—Large Hospitals, Community—Medium Hospitals, or Community—Small Hospitals (ESM eTable 4). We compared shapes of trends among hospitals that showed steep reductions within windows of two years, as would be expected if there were a hospital policy introduced to reduce opioids, and contrasted them with hospitals that moved in the opposite direction. To assess potential confounding by trends in length of stay in hospital, and to adjust the CIs for autocorrelation over time of rates for each hospital, we used generalized linear modeling of the logits of the percentages, allowing for random variation among hospitals’ trends by adjusting for autocorrelation within hospital as a random effect. When exploring changes in quantity of opioids dispensed, we widened the CIs with a Bonferroni adjustment corresponding to five tests.

For the SQOR study, we used SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) for extractions, exclusions, analyses (SAS software’s GLIMMIX procedure for generalized linear modeling), and graphing trends and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for reformatting SAS graphics (including selected 95% CIs), for extending SQOR trends using SQOR Extension trends, and for computing odds ratios. For the SQOR Extension study, we used Golden 6 (Benthic Software; Franklin, MA, USA) for extractions, Oracle SQL Developer version 4.1.4 (Oracle Corporation; Austin, TX, USA) for cohort formation, and RStudio (R Core Team 2016; Boston, MA, USA) for analyses.

Results

From a total of 171,992 Cesarean deliveries, the SQOR cohort, after exclusions, comprised 135,725 deliveries, supplemented with 30,919 from the SQOR Extension study in 2017–2019 (Table 1). The majority (53%) of deliveries were at teaching hospitals, and two-thirds of patients who were dispensed postdischarge opioids received their first opioids on the day of discharge (Table 1). The mean (SD) age of parturients was 31 (5) years and remained similar throughout the study period.

Table 1.

Cohort characteristics

| SQOR cohort characteristics (2004–2016) | n/total N (%) |

| Second Cesarean deliveries in same year (excluded) | 40/171,992 (0%) |

| No opioid dispensing, cancer, or Cesarean delivery in the previous year | 144,871/171,992 (84%) |

| Length of hospital stay 0–4 days | 135,725/171,992 (79%) |

| SQOR Extension cohort characteristics (2004–2019) | n/total N (%) |

| Second Cesarean deliveries in period 2004–2019 (excluded) | 40,773/185,332 (22%) |

| No opioid dispensing or cancer in the previous year | 165,218/185,332 (89%) |

| Length of hospital stay, 1–4 days | 146,835/185,332 (79%) |

| Cesarean deliveries 2017–2019 | 30,919/185,332 (17%) |

| CIHI hospital peer group*27 | n/total N (%) |

| Teaching Hospitals | 71,646/135,725 (53%) |

| Community—Large Hospitals | 43,581/135,725 (32%) |

| Community—Medium Hospitals | 13,359/135,725 (10%) |

| Community—Small Hospitals | 7,139/135,725 (5%) |

| Days from Cesarean delivery to discharge | Mean (SD) |

| 2004–2009 | 3.1 (0.8) |

| 2010–2014 | 2.9 (0.8) |

| 2015–2019 | 2.7 (0.8) |

| Time of first opioid dispensing | n/total N (%) |

| Day before discharge | 267/135,725 (0.2%) |

| Same day as discharge | 22,519/135,725 (17%) |

| Day after discharge | 6,097/135,725 (5%) |

| Day 2–7 after discharge | 3,861/135,725 (3%) |

| Day 8–30 after discharge | 1,032/135,725 (0.8%) |

*Canadian Institute for Health Information. Indicator Library: Peer Group Methodology, November 2019. Available from URL: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/peer-group-methodology_en.pdf (accessed April 2022)

CIHI = Canadian Institute for Health Information; SD = standard deviation; SQOR = surgical quality outcome reports

Hospital types

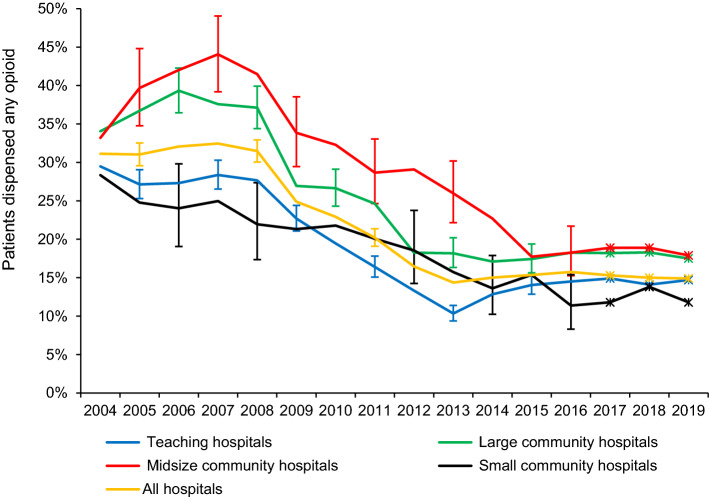

The overall opioid dispensing rate declined from an average of 31% (95% CI, 30 to 33) in 2004–2008 to 16% (95% CI, 15 to 17) in 2013–2016 (Fig. 1). The ranking of hospital types by mean opioid rates in 2004–2008 was medium community > large community > teaching > small community hospitals, but their rates converged by 2015–2016 (Fig. 1). From 2007 until 2013, the downward slopes measured as annual odds ratios were slightly steeper for teaching and large community hospitals than for midsize and small community hospitals, after adjusting for length of stay (Table 2). Nevertheless, when we allowed for randomness among hospitals’ trends, the CIs widened greatly and the estimates of the slope changed (Table 2), indicating that diversity among hospitals’ trends within each grouping is substantial.

Fig. 1.

Mean percentage of patients dispensed opioids from community pharmacies within seven days after discharge post-Cesarean delivery in British Columbia. Error bars (not shown for all points to enhance visual clarity) indicate 95% confidence intervals. Canadian Institute for Health Information hospital peer groups are defined in ESM eTable 4. *Estimated rates 2017–2019, based on trends observed in the Surgical Quality Outcome Reports Extension study

Table 2.

Hospital characteristics by CIHI hospital peer group

| CIHI hospital peer group*27 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Teaching Hospitals | Community—Large Hospitals | Community—Medium Hospitals | Community—Small Hospitals | |

| Number of hospitals | 7 | 12 | 13 | 17 |

|

Cesarean deliveries from 2007 to 2013, n |

34,539 | 24,142 | 7,450 | 3,927 |

|

Any opioid dispensed, %, mean of hospitals’ means |

||||

| in 2007, mean (SD) | 38 (22) | 35 (22) | 36 (22) | 28 (26) |

| in 2013, mean (SD) | 18 (17) | 22 (21) | 27 (24) | 11 (16) |

| Annual reduction in percent, 2007–2013, mean (SD) of hospitals’ mean reductions | 2.5 (3.0) | 1.7 (3.5) | 1.7 (3.5) | 2.0 (3.3) |

| Annual reduction in odds, 2007–2013, mean odds ratio (95% CI) adjusted for: | ||||

| No covariates | 0.87 (0.86 to 0.88) | 0.86 (0.85 to 0.87) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.94) | 0.94 (0.91 to 0.96) |

| Length of stay only | 0.87 (0.86 to 0.88) | 0.87 (0.86 to 0.88) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.94) | 0.92 (0.90 to 0.95) |

| Length of stay and first-order autocorrelation within hospital as a random effect | 0.87 (0.72 to 1.07) | 0.79 (0.67 to 0.94) | 0.83 (0.72 to 0.96) | 0.82 (0.71 to 0.94) |

|

Distribution of hospitals by mean annual change, 2007–2013 |

||||

| 1.5% to 5.0% | 0 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| -1.4% to 1.4% | 4 | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| -5.0% to -1.5% | 1 | 4 | 6 | 6 |

| Less than -5.0% | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 |

*Canadian Institute for Health Information. Indicator Library: Peer Group Methodology, November 2019. Available from URL: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/peer-group-methodology_en.pdf (accessed April 2022)

CI = confidence intervals; CIHI = Canadian Institute for Health Information; SD = standard deviation

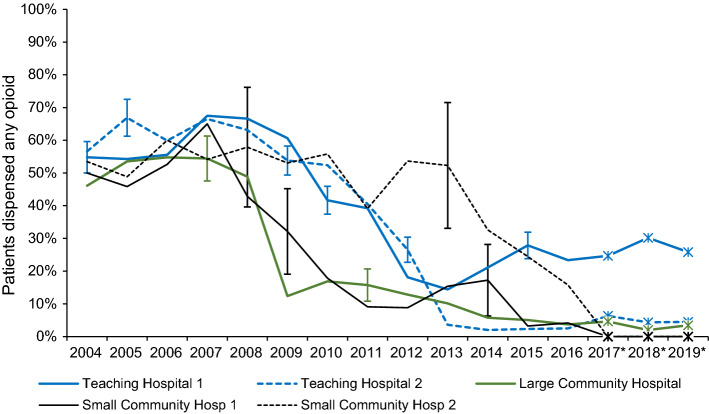

Electronic Supplementary Material eFig. 1 illustrates the diversity of trends in the period of change 2007–2013, by individual hospital grouped by type. Table 2 groups them into nine hospitals that were decreasing rapidly (annual drops of -10% to -5%), 17 that were decreasing slowly (-5.0% to -1.5%), 16 that were stationary, and seven that were increasing. Figure 2 shows the shape of the curves of the five fastest dropping hospitals: two teaching, one large community, and two small community hospitals with 40% drops within two years, two in 2008–2009, two in 2011–2012, and one in 2014–2015. The pairs with simultaneous reductions were not geographic neighbors. These hospitals all started with opioid dispensing rates over 40% in 2004–2008, and all but one (teaching) had reduced rates to below 10% by 2019. In contrast, the curves of the four fastest increasers are shown in ESM eFig. 2: one midsize and three small community hospitals with opioid dispensing rates increasing over the 16-year period at an average of 2.4% per year (95% CI, 0.4 to 4.4) after adjusting for trends in length of stay and autocorrelation over time within hospital.

Fig. 2.

Mean percentage of patients dispensed opioids from community pharmacies within seven days after discharge post-Cesarean delivery in British Columbia at five hospitals with sudden and steep reductions. Vertical error bars (not shown for all points to enhance visual clarity) indicate 95% confidence intervals. The red box highlights sharp declines of prescription rates, spanning a period from 2007 to 2015; the height of the box indicates a large drop from ~ 50% to < 10%. *Estimated rates 2017–2019, based on trends observed in the Surgical Quality Outcome Reports Extension study

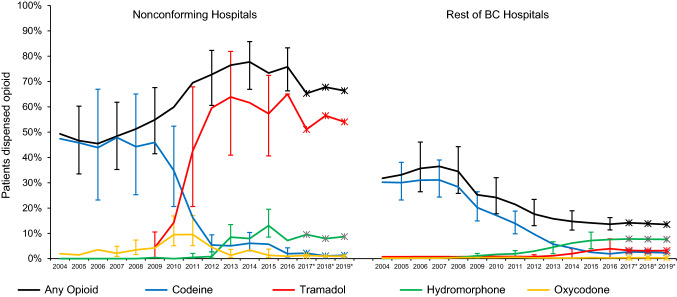

Opioid types

Three of the four hospitals with increasing opioid dispensing rates—two of them geographic neighbors—had large increases in tramadol dispensations, which were more than the replaced codeine, after adjusting for trends in length of stay and autocorrelation over time within hospital (Fig. 3A). During the transition when codeine to tramadol were about equal in BC in 2010–2011, there was also a transient increase in dispensation of oxycodone. After 2012, hydromorphone rates for these three hospitals also increased, but no more so than for the remainder of BC hospitals (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Mean percentages of patients dispensed opioids from community pharmacies within seven days after discharge post-Cesarean delivery (A) at four nonconforming hospitals and (B) at all other BC hospitals. Vertical error bars (not shown for all points to enhance visual clarity) indicate 95% confidence intervals. *Estimated rates 2017–2019, based on trends observed in the Surgical Quality Outcome Reports Extension study

The SQOR Extension study indicated that dispensing rates for different opioid types remained relatively stable from 2015 to 2019: hydromorphone 8%, tramadol 6%, oxycodone 0.5%, and codeine 3% to 2%. Electronic Supplementary Material eFig. 3 shows a metric from SQOR Extension data that did change after 2016, a doubling in preference (from 20% to 40%) for smaller quantities (< 25 tablets per prescription) of the less potent opioids, codeine and tramadol.

Discussion

In this historical cohort analysis of patients undergoing Cesarean delivery across 48 hospitals in BC from 2004 to 2019, we found that the overall rate of postdischarge opioid dispensations decreased by half from 2007 to 2013. This is consistent with the CIHI 2019 report on nationwide opioid prescriptions.28

Hospital types

Higher opioid prescribing overall in large and medium community hospitals might be associated with pharmaceutical marketing, which targets larger hospitals more intensely. The role of opioid marketing in the North American opioid crisis has been illustrated by the magnitude of the Purdue and McKinsey lawsuits,29–31 which led to payouts in the billions for the defendants’ roles in promoting opioid products. Slightly lower rates in teaching hospitals might reflect greater exposure to evidence and recent scientific findings. Lower exposure to pharmaceutical industry marketing in small community hospitals might explain differences in prescribing related to more remote geographical location and length of practice, factors shown to affect prescribing in a recent study.18

Although the mean rates decreased steadily within each hospital type, and by some measures teaching hospitals and large community hospitals decreased faster than the others, there was so much variation within the types of hospital that the differences between types must be regarded as less meaningful than the differences within types. Consistent with the USA study by Reed et al. showing variations in post-Cesarean analgesia clustered by hospital,17 we found large between-hospital variation and relatively low between-year within-hospital variation. For example, we observed only one large community hospital that had a large drop in 2008, the year of Health Canada’s advisory.14 This suggests an absence of policies for coordinated changes in prescribing opioids within hospitals in those years. On 4 April 2016, BC’s Provincial Health Officer declared a public health emergency concerning the rise in overdose deaths.2 This was not followed by further overall reductions or major shifts between opioid types in the present cohort.

Opioid types

Similar to results previously reported on postpartum patients in BC,13 we found a major drop in codeine and rise in tramadol dispensations following Health Canada’s advisory in 2008 against codeine in breastfeeding mothers.14 Several factors could have contributed to tramadol’s increased popularity, including lack of triplicate-prescription requirement in BC, inclusion in the World Health Organization pain ladder, and physician perception of efficacy and relative safety.32,33 Since 2005, when tramadol marketing started in Canada, Canadian public health boards repeatedly (in 2007, 2009, and 2017) expressed intent to reschedule tramadol as a controlled substance, to no avail, until the recent announcement that tramadol will be rescheduled starting in 2022.34,35 Tramadol has been marketed as a nonnarcotic throughout this period, despite recognition of the risk for persistent use in surgery patients and potential danger in breastfeeding mothers.15,36

Overall, the variations in postdischarge opioid dispensing rates after Cesarean delivery across different BC hospitals are echoed by the nationwide lack of synchronicity among opioid dispensing trends.37 This indicates opportunities for quality improvement guided by coordinated educational initiatives, such as the recent innovative opioid stewardship program at Vancouver’s St. Paul’s Hospital.38 Given that individual patient indications for Cesarean delivery vary39–41 and physician expertise is essential to evaluate each patient’s treatment needs, monitoring of prescribing rates should be not only at the level of hospitals but also include nonpunitive prescribing feedback reports to individual prescribers, which can be a cost-effective approach to prescribing improvement, particularly with BC’s PharmaNet data.42 Other approaches to opioid stewardship include multifactor improvement strategies such as Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) and shared decision-making models,43–46 which can be rapidly evaluated using administrative databases with the methods we have employed.

Limitations

Our findings should be interpreted in light of limitations of administrative databases. The outcome metrics were based on dispensations—filled prescriptions; we assumed that unfilled prescriptions represented a small fraction that remained steady over time. If this assumption is false, overall declines might be partially due to patients rather than prescribers, but they are unlikely to confound concurrent comparisons among hospitals and opioid types. Patient experiences—pain scores, quantities of tablets consumed, adverse events, individual health service use, patient satisfaction—were beyond the scope of the study, which was limited to administrative databases. We focused on variations among hospitals because numerous quality improvement initiatives in BC, such as ERAS, are organized via hospitals. Nevertheless, we lacked information on local opioid guidelines in each hospital over the time period. We did not explore associations with individual physicians’ demographics or practice characteristics, nor any shift in characteristics of patients undergoing Cesarean delivery over the 16 years, because they could not account for trends in the vicinity of 5% per year. A limitation of the SQOR study—having only nine months of observations after the April 2016 declaration of the public health emergency—was rectified using the Ministry’s SQOR Extension study, yet exact replication of SQOR by SQOR Extension was not possible because the Ministry terminated SQOR Extension early to fund COVID-19 studies. While SQOR used a seven-day window after discharge, SQOR Extension used a 30-day window, but this added only 0.8% additional new opioid users from eight to 30 days (Table 1), a small contamination that would cancel out when examining rate differences. The extra points in the figures for 2017–2019 (indicated by asterisks), based on applying the SQOR Extension study’s trends to the SQOR study, are presented without CIs because the added uncertainty of the extrapolation could not be computed without access to SQOR Extension data. The Bonferroni correction of the CIs of the SQOR Extension trends in tablet numbers was a post hoc adjustment, so the CIs must be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Postdischarge opioid dispensing rates after Cesarean delivery dropped gradually by half from 2007 to 2013. After a Health Canada advisory in 2008, codeine use declined across most hospitals, but in a few hospitals codeine’s historical use was more than replaced by tramadol. After the BC government declared the opioid overdose epidemic to be a public health emergency in 2016, we observed no further reductions in overall opioid dispensation rates, only a shift to smaller quantities of tablets per dispensing of codeine or tramadol. The variation in opioid dispensation rates and timing of responses to warnings among hospitals, and the persistence of “high-tramadol” hospitals point to a need for quality improvement, especially in BC where population-wide PharmaNet data enable rapid low-cost monitoring of postdischarge dispensing. Overall, the present study highlights opportunities for quality improvement and opioid stewardship through monitoring using administrative databases.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Kimia Ziafat and Stefanie Polderman contributed equally to drafting the manuscript and to analysis and interpretation of data. Noushin Nabavi contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. Roanne Preston contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of grant funding and data, study management, interpretation of data, and revisions to the manuscript. Anthony Chau contributed to conception and design, analysis and interpretation of data, and manuscript writing. Michael Krausz and Stephan Schwarz contributed to the convening of the author group, conceptualization and design, funding, interpretation of data, and manuscript writing. Malcolm Maclure contributed to all aspects, including study conception and design; acquisition of grant funding and data; study management; analysis and interpretation of data; and writing and revising the manuscript.

Funding statement

This research was funded by a grant from the Partnerships for Health System Improvement of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research grant (funding number: 0407004979) and by the Ministry of Health of British Columbia. Dr. Maclure was supported as the BC Chair in Patient Safety at The University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC, Canada) by an endowment from the BC Ministry of Health (Victoria, BC, Canada) and as Scholar-in-Residence in the BC Ministry of Health’s Partnerships and Innovation Division, 2018–2020. Dr. Krausz holds the UBC-Providence Leadership Chair for Addiction Research (Vancouver, BC, Canada). Dr. Schwarz holds the Dr. Jean Templeton Hugill Chair in Anesthesia, supported by the Dr. Jean Templeton Hugill Endowment for Anesthesia Memorial Fund at The University of British Columbia (Vancouver, BC, Canada).

Disclosures

Dr. Stephan K. W. Schwarz is the Editor-in-Chief of the Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie; he had no involvement in the handling of this manuscript. All other authors declare no other associations.

Disclaimers

The views expressed in this article are of the authors’ own accords and do not represent the official position of any institution or funder.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Philip M. Jones, Deputy Editor-in-Chief, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Data availability statement

If approved by the study hospitals through data sharing agreements, unidentified data can be made available for use by other researchers.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Kimia Ziafat and Stefanie Polderman have contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Government of Canada. Canada’s opioid crisis. Available from URL: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/publications/healthy-living/canada-opioid-crisis.pdf (accessed April 2022).

- 2.Provincial Health Services Authority. Public health emergency in BC 2017. Available from URL: http://www.bccdc.ca/about/news-stories/stories/public-health-emergency-in-bc (accessed April 2022).

- 3.Fischer B, Argento E. Prescription opioid related misuse, harms, diversion and interventions in Canada: a review. Pain Physician 2012; 15: ES191–203. [PubMed]

- 4.Gomes T, Khuu W, Martins D, et al. Contributions of prescribed and non-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: population based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ 2018; 362. 10.1136/bmj.k3207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hospital stays in Canada 2022. Available from URL: https://www.cihi.ca/en/hospital-stays-in-canada (accessed April 2022).

- 6.Canadian Institute for Health Information. QuickStats: childbirth indicators by place of residence 2020. Available from URL: https://apps.cihi.ca/mstrapp/asp/Main.aspx?evt=2048001&documentID=029DB170438205AEBCC75B8673CCE822&Server=apmstrextprd_i&Project=Quick+Stats& (accessed April 2022).

- 7.Cargill Y, Martel M-J, Clinical Practice Obstetrics Committee. Postpartum maternal and newborn discharge. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2007; 29: 357–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Pan PH. Post cesarean delivery pain management: multimodal approach. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2006;15:185–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Munishankar B, Fettes P, Moore C, McLeod GA. A double-blind randomised controlled trial of paracetamol, diclofenac or the combination for pain relief after caesarean delivery section. Int J Obst Anesth. 2008;17:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gold S, Figueiro-Filho E, Agrawal S, Selk A. Reducing the number of opioids consumed after discharge following elective Cesarean delivery: a randomized controlled trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;42:1116–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2020.02.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hansen CK, Dam M, Steingrimsdottir GE, et al. Ultrasound-guided transmuscular quadratus lumborum block for elective cesarean section significantly reduces postoperative opioid consumption and prolongs time to first opioid request: a double-blind randomized trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2019 doi: 10.1136/rapm-2019-100540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gwacham NI, Goral J, Miller R, Pitera R, Cinicolo L. Use of multi-modal analgesia in enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) for Cesarean sections to reduce the use of opioids [OP02-1B] Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000662880.08512.6b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smolina K, Weymann D, Morgan S, Ross C, Carleton B. Association between regulatory advisories and codeine prescribing to postpartum women. JAMA. 2015;313:1861–1862. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.3642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Government of Canada. Important safety information on tylenol with codeine in nursing mothers and ultra-rapid metabolizers of codeine - for health professionals - recalls and safety alerts 2008. Available from URL: https://www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/recall-alert-rappel-avis/hc-sc/2008/14526a-eng.php (accessed April 2022).

- 15.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDE drug safety communication: FDA restricts use of prescription codeine pain and cough medicines 2018. Available from URL: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/drug-safety-and-availability/fda-drug-safety-communication-fda-restricts-use-prescription-codeine-pain-and-cough-medicines-and (accessed April 2022).

- 16.American Society of Anesthesiologists’ Committee on Obstetric Anesthesia. Statement on Resuming Breastfeeding after Anesthesia 2019. Available from URL: https://www.asahq.org/standards-and-guidelines/statement-on-resuming-breastfeeding-after-anesthesia (accessed April 2022).

- 17.Reed SE, Tan HS, Fuller ME, et al. Analgesia after Cesarean delivery in the United States 2008–2018: a retrospective cohort study. Anesth Analg. 2021;133:1550–1558. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000005587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris M, McDonald EG, Marrone E, et al. Postpartum analgesia in new mothers (PAIN) study: a survey of Canadian obstetricians’ post-delivery opioid-prescribing practices. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2020;43:957–966. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2020.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateman BT, Cole NM, Maeda A, et al. Patterns of opioid prescription and use after Cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:29–35. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Osmundson SS, Schornack LA, Grasch JL, Zuckerwise LC, Young JL, Richardson MG. Postdischarge opioid use after Cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:36–41. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zipursky J, Pang A, Paterson M, et al. Trends in postpartum opioid prescribing: a time series analysis. JOGC. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2021.02.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Version 2022 ICD-10-CA/CCI classiciations, Canadian coding standards and related products 2022. Available from URL: https://www.cihi.ca/en/version-2022-icd-10-cacci-classifications-canadian-coding-standards-and-related-products (accessed April 2022).

- 23.Population Data BC. Discharge abstracts database (hospital separations) data set 2022. Available from URL: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/health/dad (accessed April 2022).

- 24.Population Data BC. PharmaNet data set 2022. Available from URL: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/health/pharmanet (accessed April 2022).

- 25.Population Data BC. Medical services plan data set 2022. Available from URL: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/health/msp (accessed April 2022).

- 26.Population Data BC. Central demographics file (MSP registration and premium billings, client roster and census geodata/consolidation file (MSP registration and premium billing) data set 2022. Available from URL: https://www.popdata.bc.ca/data/demographic/consolidation_file (accessed April 2022).

- 27.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Your health system 2021. Available from URL: http://yourhealthsystem.cihi.ca/static/assets/hsp_pro/build/download/All_Results_Export.xlsx (accessed April 2022).

- 28.Canadian Institute for Health Information. Opioid prescribing in Canada: how are practices changing? 2019. Available from URL: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/opioid-prescribing-canada-trends-en-web.pdf (accessed April 2022).

- 29.Alam A, Juurlink DN. The prescription opioid epidemic: an overview for anesthesiologists. Can J Anesth. 2016;63:61–68. doi: 10.1007/s12630-015-0520-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forsythe M, Bogdanich W. McKinsey settles for nearly $600 million over role in opioid crisis 2021. Available from URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/03/business/mckinsey-opioids-settlement.html (accessed April 2022).

- 31.Persaud N. Will the new opioid guidelines harm more people than they help? No. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64:102–104. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grond S, Sablotzki A. Clinical pharmacology of tramadol. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43:879–923. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200443130-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radbruch L, Grond S, Lehmann KA. A risk-benefit assessment of tramadol in the management of pain. Drug Saf. 1996;15:8–29. doi: 10.2165/00002018-199615010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Government of Canada. Amending the narcotic control regulations (tramadol) 2019. Available from URL: https://canadagazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p1/2019/2019-04-20/html/reg2-eng.html (accessed April 2022).

- 35.Government of Canada. Regulations amending the narcotic control regulations (tramadol) 2021. Available from URL: https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2021/2021-03-31/html/sor-dors43-eng.html (accessed April 2022).

- 36.Thiels CA, Habermann EB, Hooten WM, Jeffery MM. Chronic use of tramadol after acute pain episode: cohort study. BMJ. 2019 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fischer B, Jones W, Vojtila L, Kurdyak P. Patterns, changes, and trends in prescription opioid dispensing in Canada, 2005–2016. Pain Physician. 2018;21:219–228. doi: 10.36076/ppj.2018.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.British Columbia Centre for Substance Use, Providence Health Care. St. Paul’s Hospital opioid stewardship program: 6 month program report January-June 2020. Available from URL: https://www.bccsu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/10/OpioidStewardshipProgram-Final.pdf (accessed April 2022).

- 39.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations: non-clinical interventions to reduce unnecessary caesarean sections 2018. Available from URL: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/non-clinical-interventions-to-reduce-cs/en/ (accessed April 2022). [PubMed]

- 40.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (College), Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary Cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2014; 210: 179–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (College), Society for Materinal-Fetal Medicine, Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ. Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery 214; 210: 179–93. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Dormuth CR, Carney G, Taylor S, Bassett K, Maclure M. A randomized trial assessing the impact of a personal printed feedback portrait on statin prescribing in primary care. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2012;32:153–162. doi: 10.1002/chp.21140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonnie RJ, Ford MA, Phillips JK. Evidence on Strategies for Addressing the Opioid Epidemic. In: Bonnie RJ, Ford MA, Phillips JK, editors. Pain Management and the Opioid Epidemic: Balancing Societal and Individual Benefits and Risks of Prescription Opioid Use. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2017. pp. 267–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Peahl AF, Smith R, Johnson TRB, Morgan DM, Pearlman MD. Better late than never: why obstetricians must implement enhanced recovery after Cesarean. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221(117):e1–117. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Prabhu M, McQuaid-Hanson E, Hopp S, et al. A shared decision-making intervention to guide opioid prescribing after Cesarean delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130:42–46. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shinnick JK, Ruhotina M, Has P, et al. Enhanced recovery after surgery for Cesarean delivery decreases length of hospital stay and opioid consumption: a quality improvement initiative. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38:e215–e223. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1709456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lester SA, Kim B, Tubinis MD, Morgan CJ, Powell MF. Impact of an enhanced recovery program for Cesarean delivery delivery on postoperative opioid use. Int J Obstet Anesth. 2020;43:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijoa.2020.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

If approved by the study hospitals through data sharing agreements, unidentified data can be made available for use by other researchers.