Abstract

This research examines the role of commercial banks in influencing customers’ perceived financial well-being under the basic psychological need theory and the impact of customers’ perception of financial health on their bank loyalty. We firstly conducted in-depth interviews to explore bank-related factors that could help satisfy the needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence that a bank customer may have in their financial life. A structural equation model linking personalization of service offerings, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, communication, service quality, customer satisfaction, perceived financial well-being and customer loyalty is tested using data collected from 391 Vietnamese individual bank customers. The results indicate that the personalization of service offerings, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, and service quality could help enhance financial well-being among bank customers. This could be explained by the impacts of these factors in either satisfying customers’ psychological needs or enhancing overall customer satisfaction with banking services. Further, we also find that financial well-being not only positively affects customer loyalty but also moderates the relationship between customer satisfaction and bank loyalty. This research provides crucial strategies for commercial banks to improve financial well-being among their customers and hence, further increase customer retention and lifetime value.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1057/s41264-022-00170-z.

Keywords: Personalization, Interpersonal adaptive behaviour, Service quality, Communication, Customer satisfaction, Customer loyalty, Financial well-being

Introduction

In today’s uncertain world where individuals are frequently exposed to socio-economic shocks, the perception of financial health becomes paramount to gear their emotions and behaviour in positive directions (Hojman et al. 2016). Financial well-being is defined as an individual’s ability to maintain the current and anticipated desired living standards while freely making financial decisions (Brüggen et al. 2017). According to this concept, an individual’s financial health is manifested by the level of stress or satisfaction with the current financial situation and the ability to meet the intended future spending needs (Losada-Otálora and Alkire 2019). Previous studies show that favourable perceptions of financial health can affect individuals’ mental health and social behaviour as well as their financial decisions in a positive way, hence, contributing to the country’s socio-economic development and vice versa (Hojman et al. 2016; Serido et al. 2013). The perceived financial well-being should be distinguished from the actual financial health which is measured by objective variables such as the amount of money saved, liquidity or assets available for the present and the future (Morduch and Schneider 2017). Since feeling about financial health is considered to have a more important meaning in predicting behaviours (Hojman et al. 2016), this study gives a primary focus on perceived financial well-being.

The literature about perceived financial well-being has been well established with two strands of research. The first examines the determinants of one’s perception of their financial health. Most previous studies assess the impact of personal characteristics such as demographic factors, the ability to control spending, or financial literacy on perceived financial health (Chatterjee et al. 2019; Ponchio et al. 2019; Riitsalu and Murakas 2019). Others find the linkage between how an individual uses specific financial services, such as cash advances, loans from banks or credit cards and their subjective financial well-being (Braun Santos et al. 2016; Chan et al. 2012; Limbu and Sato 2019; Norvilitis and Mao 2013). However, there are very few studies investigating the role of commercial banks, as the providers of financial solutions, in influencing their customers’ perceived financial health. The most recent research by Losada-Otalora and Alkire (2019) only addresses the impact of banking information transparency on the perceived financial health of customers by minimizing information risk and supporting financial decision-making. The second research strand focuses on the consequences of perceived financial well-being. Again, most previous studies examine the personal consequences of financial well-being on individuals’ mental health and social behaviour (Hojman et al. 2016; Serido et al. 2013), overall life satisfaction (Netemeyer et al. 2018), purchasing choices (Hampson et al. 2018; Paylan and Kavas 2021), and performance outcome in the workplace (Cox et al. 2009).

Financial life is an inevitable dimension of subjective well-being (Diener 1984). Previous works on subjective well-being assert that not only money or objective income (Easterlin 1995; Ng and Diener 2014) but also one’s perception of financial confidence and security, a subjective appraisal, or feelings about the ability to either meet basic needs or afford expected purchases, is also a crucial domain of subjective well-being (Cummins et al. 2003; Moghaddam 2008; Netemeyer et al. 2018). According to the basic psychological need theory, one of the six mini-theories of the self-determination theory, the satisfaction of three fundamental psychological needs, including autonomy, relatedness, and competence serves as a psychological nutrient that is essential for individuals’ well-being (Ryan and Deci 2000; Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013). In addition, based on the bottom-up theory, subjective well-being is also driven by the satisfaction with consumption of goods and services such as consumer goods (Christopher et al. 2007), mobile data services (Choi et al. 2007). In this study, we argue that banking services are born to enhance financial management effectiveness and resolve individuals’ financial problems. Moreover, bank customers also have psychological needs that are expected to be satisfied (Chung‐Herrera 2007). Therefore, banking activities or performance during the process of service delivery that could help satisfy those psychological needs could contribute to the overall customer satisfaction that, in turn, enhance financial well-being. Nevertheless, there is a lack of literature that fully explore bank-related factors that could help satisfy the customers’ psychological needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competence and how those factors could contribute to financial well-being. Moreover, according to Luhmann and Hennecke (2017), people with higher levels of subjective well-being would demonstrate less desire for change. Instead, they tend to maintain the behaviours associated with the current state as a loss avoidance strategy (Rothman 2000; Rothman et al. 2004). Given that perceived financial heal is a domain of subjective well-being, if the banks could support their customers to reach their desired level of financial state, the customers are likely willing to stay with the banks to sustain their current favourable perceived financial well-being. This evokes an idea of examining the relationship between perceived financial well-being and bank loyalty.

In response to these research gaps, we aim to answer two primary questions regarding “how commercial banks could enhance their customers’ perceived financial well-being” and “in doing so, whether the banks could enhance their customer loyalty?”. Due to this research’s novelty, upon the theoretical underpinnings of the basic psychological need theory, we firstly conducted qualitative research with in-depth interviews to explore bank-related factors that could satisfy customers’ needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence in their financial life. A quantitative survey was then implemented on 391 Vietnamese bank customers to test the conceptual model. The findings indicate that the personalization of service offerings, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, and service quality could help enhance financial well-being among bank customers. This could be explained by the impacts of these factors in either satisfying customers’ psychological needs in their financial life or enhancing overall customer satisfaction with banking services. This, in turn, mitigates one’s current financial stress and strengthens their belief about financial security for future consumption. Further, we find that financial well-being not only positively affects customer loyalty but also moderates the relationship between customer satisfaction and bank loyalty.

This research has at least three significant contributions. First, we enrich the existing knowledge about the determinants of perceived financial well-being. Specifically, this study extends Losada-Otálora and Alkire (2019) to reveal that commercial banks could help improve their customers’ perceived financial well-being in many ways rather than the provision of transparent information. Second, while Kiymaza and Öztürkkal (2019) find the relationship between financial needs and subjective financial well-being, this paper presents the first attempt to examine how commercial banks could influence subjective financial health by satisfying those financial needs. Third, we also contribute to the research strand regarding the consequences of perceived financial well-being by affirming the positive linkage between this variable and bank loyalty. Fourth, we provide a fresh perspective in explaining the fundamental satisfaction-loyalty path in bank marketing, through the mediation of financial well-being. Fifth, we further provide insights into the interrelationship between bank-related factors and subjective financial health by separately retesting the conceptual model for the subsample of private banks’ customers and that of state-owned banks’ customers. This would help the two banking sectors tailor their strategies to enhance perceived financial well-being of their customers and in turn, attain benefits from customer retention. This study provides a scientific base for not only guiding but also motivating banks to support their bank customers to feel better about their financial health, as a way to enhance customer lifetime value and enhance the sector’s contribution to society at large.

Theoretical background and hypothesis development

The concept of financial well-being

Given the multi-dimensional impacts of financial health, financial well-being has been examined from various lenses such as management, economics, finance, and psychology (Brüggen et al. 2017; Gutter and Copur 2011; Greninger 1996; Netemeyer et al. 2018; Shim et al. 2009). Nevertheless, there is hardly a universally accepted definition and measurement of this construct.

The most fundamental debate about financial well-being is whether the concept should include objective or subjective dimensions or both (Brüggen et al. 2017; Xiao and Porto 2017). This will further guide the measurement of this variable. Specifically, the objective financial well-being indicates “the extent to which someone is able to meet all their current commitments and needs comfortably and has the financial resilience to maintain this in the future” through proxies such as credit ratio or borrowing-to-income ratio and income (Kempson et al. 2017, p. 19). Meanwhile, subjective financial well-being reflects “the perception of being able to sustain current and anticipated desired living standards and financial freedom” (Brüggen et al. 2017, p. 2). Across different research domains, while some studies examine an individual’s financial well-being based on merely objective measures (Schmeiser and Seligman 2012), others predict perceived financial health upon both subjective and objective dimensions (Shim et al. 2009). However, financial well-being is increasingly conceptualized as a purely subjective construct (Brüggen et al. 2017; Gerrans et al. 2014; Losada-Otalara and Alkire 2019) due to several reasons. First, Diener (1984) argued that financial well-being or well-being at large encompasses individuals’ experiences in life, therefore, it should be measured subjectively with both cognitive and affective aspects. Objective measures, therefore, could not depict financial well-being. Secondly, while social impacts are the fundamental concern when examining financial well-being, subjective financial well-being is found to have greater effects on individuals’ life quality compared to objective one (Judge et al. 2010). Finally, given the complex nature of financial well-being, the subjective conceptualization is believed to be more comprehensive since it could reflect sophisticated non-financial issues while the objective measure could not (Brüggen et al. 2017). In other words, a subjective approach is more appropriate to explore the complex nature of financial well-being, as the perception of being able to sustain current anticipated desired living standards and financial freedom (Brüggen et al. 2017). In practice, there is always a possibility of a disconnection between an individual’s actual financial state and their perceived financial state (Magni et al. 2018). Nevertheless, only the subjective financial well-being could anticipate desired living standards and reflect the scope of financial well-being from “keeping the current financial status” up to “achieving financial freedom” (Brüggen et al. 2017, p. 2). Based on the above discussion, this research adopts the subjective approach to examine financial well-being. Following the definition of subjective financial well-being as proposed by Brüggen et al. (2017), this construct could be proxied by both current money management stress (i.e., individuals’ satisfaction or feelings of being stressed about their current financial situation), expected future financial security (i.e., feelings about the longer-term security of one’s financial status) (Gerrans et al. 2014; Losada-Otalara and Alkire 2019; Netemeyer et al. 2018).

The satisfaction of psychological needs and subjective financial well-being

The basic psychological need theory

The basic psychological need theory, one of the six mini-theories of the self-determination theory, has been commonly utilized to explain how the satisfaction of psychological need serves as a psychological nutrient that is essential for individuals’ well-being (Ryan and Deci 2000; Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013). In this framework, a person may have three primary psychological needs, including autonomy, relatedness, and competence (Deci and Ryan 2000). Autonomy refers to one’s experience of willingness to engage in certain behaviours. As their actions, feelings, and thoughts are self-endorsed, the satisfaction of autonomy provides them with a sense of authenticity and integrity. Autonomy frustration leads to the sense of pressure or the feeling of being pushed. Relatedness denotes the need to be connected and significant to other people through the experience of warmth, bonding, and care. When frustrated, one could face a sense of exclusion and loneliness. Competence, also known as self-efficacy, refers to the experience of effectiveness and mastery. This psychological need is satisfied when one successfully uses their skills and expertise to deal with certain situations, otherwise one would experience a sense of ineffectiveness or helplessness (Ryan and Deci 2000).

Based on an exploratory study across various service sectors, Chung—Herrera (2007) argues that in the financial service industry, customers also have psychological needs that are expected to be satisfied. The linkage between the satisfaction of psychological needs and financial behaviours is affirmed in previous studies. Xiao and Anderson (1997) assert that the purchase of bonds and stocks is associated with spiritual needs in one’s financial life. Lee and Hanna (2015) add that the saving decision is also motivated by the psychological needs of human beings. Those financial behaviours, in turn, would directly influence financial well-being (Brüggen et al. 2017). Previous works also find the association between the need for competence, as featured by the sense of being in control of personal finances and financial well-being (Muir et al. 2017; Vlaev and Elliott 2013). In this study, we, therefore, examine the role of commercial banks in enhancing customers’ perceived financial well-being through the satisfaction of psychological needs.

When applying a general perspective to a specific context, adaptations are needed. To adapt the basic psychological need theory in developing hypotheses and the conceptual model, we conducted in-depth interviews with 32 bank customers who are using various banking services and products, including debit cards, credit cards, insurance, saving and borrowing services. The information collected from the interviews was merged and conceptualized with both the basic psychological need theory and the literature in bank marketing to explore relevant bank-related factors that may be associated with the satisfaction of autonomy, relatedness, and competence in one’s financial life. This serves to formulate hypotheses and define the conceptual model. To proceed and make clear the basis for our adaptations, the following section regarding hypothesis development will incorporate the arguments supported by the theoretical background and findings from the qualitative phase where applicable.

Bank-related factors and the satisfaction of psychological needs

Customers use banking services and products for not only immediate consumption that helps satisfy material needs but also for their financial security of future consumption that is more inclined to psychological needs (Xiao and Noring 1994). In this regard, by satisfying the needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competency in one’s financial life, commercial banks could enhance their customer satisfaction. Based on the theoretical concepts of autonomy, relatedness, and competence, the interview began by asking questions to explore bank-related factors that may help satisfy those psychological needs of bank customers.

First, banking activities that help satisfy the need for autonomy in one’s financial life were identified by asking “How could your bank help you feel freedom or autonomy in your everyday financial decisions?”. The personalization of service offerings emerged from the participants’ answers as the relevant banks’ initiative that could help satisfy their customers’ need for autonomy (See Table 1). Rooted in the one-to-one marketing perspective, personalization, also known as service offering adaptation refers to the customization of service offerings to fit customer needs (Peppers and Rogers 1993). According to Ball et al. (2006), personalization is a feature of products and services that creates competitive advantages for the company by providing more value to customers. Findings from our interview research further indicate that personalization not only offers more functional value by better serving the unique needs of customers but also enriches psychological value to them by meeting their needs for autonomy. Specifically, the customized experience of banking services provides customers with a sense of integrity and interdependence in either making financial decisions or resolving financial issues in the way they want.

Table 1.

Bank-related factors that are linked to the satisfaction of psychological needs

| Psychological needs | Relevant constructs | Core ideas |

|---|---|---|

| Autonomy | Personalization | Flexible policies that allow customization |

| Adaptation of services to meet unique needs | ||

| Relatedness | Interpersonal adaptive behaviour | Being treated as a unique individual |

| Having financial concerns listened to and respected | ||

| Personal care | ||

| Communication | Being informed | |

| Receiving advice | ||

| Satisfactory relationship with banks | ||

| Competency | Service quality | Reliable products and services |

| Willingness to help with financial problems | ||

| Security | ||

| Communication | Good quality of information | |

| Good advice |

A few examples of quotes that featured the linkage between personalization and autonomy are as follows:

My banks have some flexible policies to adapt my unique financial needs…whenever I encounter financial issues, I could find solutions from my banks’ support that are tailor-made to my specific problems.

…that’s when banking services are customized to me so that I could make decisions as I wish….

...I feel that my specific needs and requirements are respected…those customized services support me a lot to be independent in my financial decisions…

Second, to explore bank-related factors that indicated the association between banking activities and the need for relatedness in financial life, participants were asked “How does your bank help you feel connected and being care in financial management?”. Banks’ communication activities and interpersonal adaptive behaviour shown by banks’ front staff who directly interact with the customers demonstrate the most relevant attributes pertaining to the sense of relatedness. Interpersonal adaptive behaviour is another dimension of service customization, in addition to service offering adaptation (Gwinner et al. 2005). This concept refers to the customization of the customer-front staff interaction process via the interpersonal elements, such as personal customer dialogue, presentation style, and social behaviour (Gwinner et al. 2005; Román and Iacobucci 2010). On the other hand, as an integral part of a marketing mix program, communication refers to the banks’ ability to keep in touch and build satisfactory customer relationships by providing them with timely and trustworthy information as well as valuable advice (Ball et al. 2004; Oly Ndubisi and Kok Wah 2005; Oly Ndubisi 2007). Our findings reveal that customers’ sense of relatedness is aroused from not only the personal treatment of bank employees but also the connection with banks through information exchange and consultancy. Some examples of quotes that depict the connection between interpersonal adaptive behaviour and one’s need for relatedness are as follows:

I feel not alone in resolving financial issues since my bank’s employees are willing to provide personalized treatment to me….

...they are always available to connect with me on a personal basis and listen to my unique financial concern…

Some employees in my bank act as friends of mine who care and take efforts to understand my specific financial issues…

My bank provides a point of information provider…they are always there to give me advice and support so that I am not alone with my financial problem…

I always receive updated information about new products and services from my bank that suits my financial concern…

Third, initiatives from banks that could satisfy the need for competence in financial management were identified through their responses to the question “How does your bank enhance your capacity to manage your financial life?”. Two primary attributes were reported, including banks’ communication activities and service quality. First, the interview results reveal that the banking services and products themselves could empower customers’ self-efficacy in financial management. In this regard, service quality, or consumer’s judgment about overall service excellence (Bolton and Drew 1991; Parasuraman et al. 1988; Zeithaml 1988), is associated with the extent to which bank customers’ sense of competence in financial life is enhanced. Second, our findings also indicate that information and advice provided by banks through communication programs represent other sources of financial self-efficacy. Some examples of quotes that indicate the relevance between either communication or service quality and one’s financial self-efficacy are as follows:

…more confident due to the employment of reliable banking services.…

Good sources of information and advice from banks support me a lot in my financial decisions…

The excellent banking services themselves empower me to manage my financial life…

Majority of my financial management relies on banking services and products…feel helpless and frustrated when my bank says no to my issue or could not deliver the services as promised

My financial assets are in banks…I believe in my bank’s ability to keep it safe and support me to conduct transactions fast and smoothly whenever I want

The linkages between personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, communication, service quality, and customer satisfaction have been studied in previous works. Rooted from the understanding of each customer’s needs to satisfy their demand efficiently and knowledgeably, personalized service offerings provide customers with the “right” value and meet or even surpass their unique expectations (Riecken 2000). Moreover, the attainment of desired outcomes also creates customer delight, a type of positive affect (Arnold et al. 2005; Barnes et al. 2010). Similarly, customers’ positive emotions may also result from the behaviour of employees, which, in turn favourably influence customer evaluations (Bock et al. 2016). Personalization and interpersonal adaptive behaviour, therefore, may provide a central route to customer satisfaction (Ball et al. 2006; Peppers and Rogers 1993; Rust et al. 2000). The linkage between communication and customer satisfaction is also highlighted by Ball et al. (2004) in the banking service context. Specifically, either one-way or in-person communication could enhance customer value through the exchange of clear, transparent, and valuable information. In addition, service quality is another crucial determinant of customer satisfaction that could be explained by its influence on the perceived value of the service (Bolton and Drew 1991; Ball et al. 2004, 2006; Chang and Wildt 1994; Holbrook 1994; Sirdeshmukh et al. 2002).

Based on the findings from the qualitative research phase and the existing literature, we hypothesize that:

H1a

Personalization positively affects customer satisfaction.

H1b

Interpersonal adaptive behaviour positively affects customer satisfaction.

H1c

Communication positively affects customer satisfaction.

H1d

Service quality positively affects customer satisfaction.

Customer satisfaction and perceived financial well-being

Subjective well-being is all about “how and why people experience their lives in positive ways” (Diener 1984). This concept encompasses both cognitive and affective components (van Praag et al. 2003) and represents an overall assessment of one’s state in various life domains, such as job, physical health, relationships, and wealth, weighted by the perceived value of each domain (van Praag et al. 2003). The cognitive dimension includes judgements of one’s satisfaction with life while the affective aspect indicates how frequently he or she experiences positive emotions (Diener et al. 2010). Financial standing is a crucial dimension of a person’s subjective well-being (Diener 1984). Previous works on subjective well-being consider money or objective income as the only measure of subjective financial well-being (Easterlin 1995; Ng and Diener 2014). The need theory asserts that money is strongly related to well-being since it could help satisfy material needs (Biswas-Diener and Diener 2001; Howell et al. 2006). However, Xiao and Noring (1994) argue that besides the financial need for immediate consumption that satisfies basic needs at the bottom of the pyramid, says physiological needs, there exists another type of financial need for future consumption that is associated with higher-level needs, such as security needs. This is closely associated with the perception of financial confidence and security or feelings about the ability to either meet basic needs or afford future purchases. Perceived financial well-being, hence, is a crucial domain of subjective well-being (Cummins et al. 2003; Moghaddam 2008; Netemeyer et al. 2018). In this study, we, therefore, treat perceived financial well-being as subjective well-being in one’s financial life.

According to the bottom-up theory, one’s life satisfaction and emotions are influenced by situational or environmental factors, including places, things, activities, roles, and relationships as primary life domains (Choi et al. 2007). Previous studies find that subjective well-being could be positively affected by leisure satisfaction (Wang et al. 2008) and job satisfaction (Sironi 2019; Steiner and Truxillo 1987; Weziak-Bialowolska et al. 2020), and even satisfaction with the consumption of goods and services such as consumer goods (Christopher et al. 2007), mobile data service (Choi et al. 2007) and automobile consumption (Wang 2008). In this regard, perceived financial well-being, as satisfaction and emotions that individual forms in their financial life, maybe also affected by situational and environmental factors, such as financial activities, relationships with financial institutions, and the use of financial products and services.

Banking services are designed to support customers’ financial life by empowering their financial capabilities and helping them better manage their financial assets. While some banking services such as credit cards and lending services could alleviate financial stress by providing immediate finance, other services such as savings, pension funds, and insurance may encourage financially sound behaviours that ensure financial security for future needs. In addition, financial advice provided by banks is also a good source of reference that, together with other banking products and services, supports bank customers to stabilize vulnerable life situations and overcome financial shocks (Brüggen et al. 2017). Satisfaction with banking services implies the good use of financial services and an easy relationship with banks that may contribute to a positive affective state and favourable experience in one’s financial life. This, in turn, could contribute to the enhancement of perceived financial well-being.

H2

Customer satisfaction positively affects perceived financial well-being.

The mediating role of customer satisfaction in the impacts of personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, communication, and service quality on financial well-being

Given that subjective well-being is the perception of being able to sustain current and anticipated desired living standards with financial freedom (Brüggen et al. 2017), this construct is closely related to the psychological needs in terms of autonomy, relatedness, and competence. The concept of financial well-being is intricately linked with the sense of being in control of personal finances (Muir et al. 2017; Vlaev and Elliott 2013). This psychological need, indeed, reflects the “competency” aspect of one’s financial life. On the other hand, financial freedom is also an important dimension of perceived financial well-being. It implies that the individual feels free from being forced or stressed about constraints when making financial decisions for necessities or baseline expenses (Cazzin 2011). The concept of financial freedom is, therefore, directly associated with the need for autonomy. The need for relatedness in one’s financial life is almost neglected in previous works. In this study, we argue that since individuals could seek financial support or advice from external sources, the sense of being connected in terms of financial activities may help reduce stress and strengthen confidence about either current or future financial state and hence, lead to more favourable attitude towards financial well-being.

The linkage between the extent to which a commercial bank could satisfy its customers’ psychological needs through personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, communication, and service quality and bank customers’ perceived financial well-being was further explored in the qualitative research phase. Specifically, in the in-depth interview, participants were asked “How does your bank help you to reduce your current financial stress and ensure future financial security?”. Personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, communication, and service quality emerged as four primary factors that contribute to subjective financial well-being in different ways. A few examples of answers are as follows:

I feel assured about my ability to meet future financial needs since I always help my bank listen to my issues and am willing to customize the services to adapt to my unique needs

Whenever I feel stressed about my financial situation, I could seek advice from bank employees who always try to understand and help me with personal treatment

I think selecting a bank with good services is everything to me. There are always suitable products and services that provide solutions for financial issues…of course, provided that the bank should keep its promise…

My bank acts as a personal consultant to me in my financial life and even more than that…I highly appreciate the information and advice from bank employees that support me a lot to deal with my concern and neutralize my financial stress…

I used to worry about who would help me when I need financial support…now I feel more independent and confident in my ability to overcome financial problems since I know that my bank is available to support me with suitable and reliable products and services that are born for me…

The qualitative findings indicate that when customers are satisfied with banking services that are not only of high quality but also personalized to their distinct needs, they become more confident and less stressed about their current financial needs and future financial security. The satisfaction with banking services arouses a sense of effectiveness and makes them believe in their self-efficacy in resolving their financial issues, overcoming financial constraints, and reaching standards of livings as they expect. As being in control of their financial state and financial freedom are enhanced, the satisfied bank customers may form a more favourable perception of their financial well-being. On the other hand, interpersonal adaptive behaviour and communication may influence perceived financial well-being by satisfying the need for relatedness. Specifically, the satisfactory dialogue with bank employees where customers receive special and attentive treatment and valuable information provides the experience of bonding and care. This, in turn, reduces their financial stress and builds confidence in their self-efficacy in resolving financial issues as they know that banks would always listen and support them.

Based on the theoretical arguments and findings from the interview research, we hypothesize that customer satisfaction (where the needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competency in one’s financial life are satisfied through the experience of banking products and services) plays a central role in the impacts of personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, communication, and service quality on perceived financial well-being.

H3a

Customer satisfaction mediates the relationship between personalization and perceived financial well-being.

H3b

Customer satisfaction mediates the relationship between interpersonal adaptive behaviour and perceived financial well-being.

H3c

Customer satisfaction mediates the relationship between communication and perceived financial well-being.

H3d

Customer satisfaction mediates the relationship between service quality and perceived financial well-being.

Perceived financial well-being and customer loyalty

This study also attempts to expand the existing knowledge about the consequences of maintaining customers’ financial well-being in the banking service context by examining the relationship between perceived financial well-being and customer loyalty. Contemporary theories assert that one’s motivation to change is initiated by perceived discrepancies between a current state and the desired state (Carver and Scheier 1990, 2001) or their needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness are not fulfilled (Deci and Ryan 2000; Ryan and Deci 2008; Sheldon and Gunz 2009). In other words, dissatisfaction or the negative affective state resulting from such perceived discrepancies motivates people to change as a way to reduce these discrepancies. On the other hand, the self-regulatory model depicts that those who are satisfied with a current state tend to maintain behaviours associated with this state as a way to avoid the possibility of an alternative undesired state (Rothman 2000; Rothman et al. 2004). This behaviour is also known as “the prevention focus” based on the self-regulatory focus theory (Higgins 1997, 1998) or “loss-avoidance behaviour” (Baltes and Baltes 1990; Ebner et al. 2006; Freund et al. 2012). Regarding subjective well-being, Luhmann and Hennecke (2017) contend that people with low levels of subjective well-being are more inclined to change life circumstances that are perceived as unsatisfactory. Meanwhile, those with high levels of subjective well-being have less desire for change to maintain the favourable discrepancies between the current and the desired state.

In this study, we argue that customers who are satisfied with their financial well-being would less likely switch to other banks since continuing current banking services and products may represent behaviour that helps maintain their good state of financial health. In contrast, those who are stressed with their financial situations and worried about their financial security are more likely to seek new financial service providers to approach a better financial state.

H4

Perceived financial well-being positively affects customer loyalty.

The mediating role of perceived financial well-being in the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty

According to the principle of social exchange theory, social exchange regards “voluntary actions of individuals that are motivated by the return they are expected to bring from others” (Blau 1964). In this regard, previous studies assert that customer satisfaction could help enhance customer loyalty by discouraging the intention to switch (Bruhn and Grund 2000; Mohsan et al. 2011; Olajide and Israel 2013; Patterson 2004). Specifically, the more rewards customers gain from their relationship with a brand, the more switching costs they must bear if they change their service providers (Patterson 2004). A good perception of financial health could be a psychological reward that a customer could obtain from the satisfaction of current banking services and products that, in turn, discourage the switching behaviour. In this regard, the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty could be explained from the psychological perspective, through the mediation effect of financial well-being.

H5

Perceived financial well-being mediates the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty.

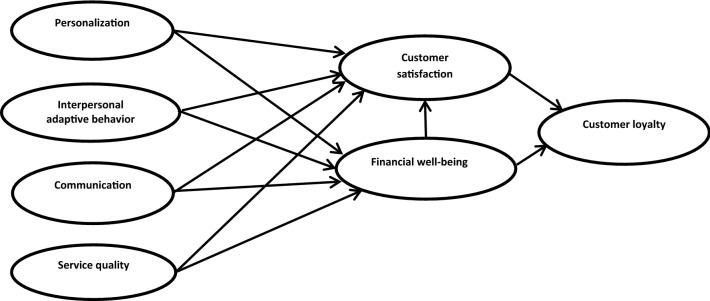

The conceptual model is presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model (Model 1)

Methodology

Since previous studies which apply the basic psychological need theory in examining banks’ initiatives to enhance their customers’ perceived financial well-being are non-existent, this study first conducted in-depth interviews in June 2021 to explore bank-related factors that help satisfy the needs of autonomy, relatedness, and competency in one’s financial life. 32 bank customers were invited to join the interview. They were selected to ensure diversity in terms of their experiences with banking services and education levels (that may influence their financial literacy). Table 2 presents the characteristics of the participants.

Table 2.

Participants’ profiles for the in-depth interview

| Characteristic | Number | |

|---|---|---|

| Experience in using banking services | Less than 3 years | 8 |

| From 3 to 5 years | 10 | |

| More than 5 years | 14 | |

| Type of banking services and products | Debit cards | 32 |

| Credit cards | 20 | |

| Borrowing | 19 | |

| Saving | 16 | |

| Insurance | 11 | |

| Education level | Not attained secondary education yet | 2 |

| Secondary education | 5 | |

| Tertiary education | 18 | |

| Above tertiary education | 7 | |

Before the interview, we sent out an invitation to each participant, clearly stating our purposes and obtaining their consent. We prepared a list of open-ended questions in advance so that an interviewer in each session utilized those questions to guide and encourage the participants to share their ideas on the preset topics. Each interview was conducted within 30 min, face to face via Zoom. Upon the participants’ approval, their answers during the interview sessions were recorded and deleted as soon as the research was done. The findings from the interview research were used to develop the research hypotheses and define the conceptual model. (Figs. 2 and 3)

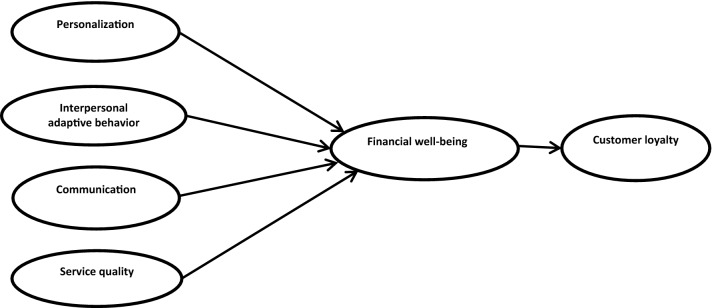

Fig. 2.

Modified model (Model 2)

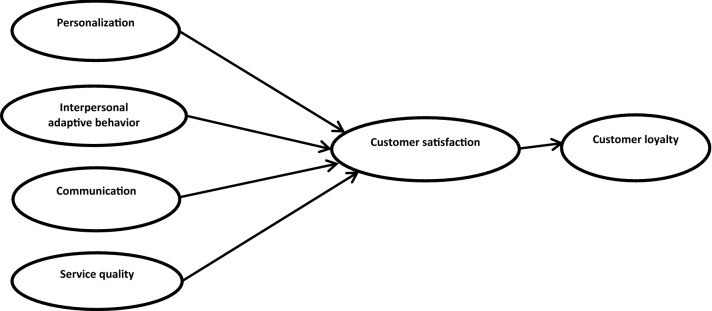

Fig. 3.

Modified model (Model 3)

To test the proposed model, we employed the survey method to collect quantitative data. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, an online questionnaire was utilized for data collection. Measurement scales of personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, service quality, communication, customer satisfaction, and customer loyalty were adapted from previous works in the field of bank marketing to ensure face validity. The response format to measure latent variables was based on a 5-point Likert scale. Based on the conceptualization of subjective financial well-being proposed by Brüggen et al. (2017) and its primary sub-dimensions (Netemeyer et al. 2018), this study employs measurement properties of perceived financial well-being as validated by Gerrans et al. (2014) and Losada-Otalara and Alkire (2019). The 5-item scale captures all key dimensions of subjective financial well-being, including one’s perception of stress or satisfaction associated with their current financial state and their self-efficacy to meet future financial demands, both planned and unexpected.

The translation and adjustment of the measurement items were evaluated and approved by experts in bank marketing to ensure face validity. Next, we conducted a pilot test on 20 Vietnamese bank customers from all walks of life to ensure the questionnaire’s comprehension; easy-to-understand language and phraseology; ease of answering; practicality and length of the survey (Hague et al. 2004). The final measurement properties are shown in Table 3. The quantitative survey was conducted from August to September of 2021. First, among 39 major commercial banks in Vietnam (including both state-owned and joint-stock commercial banks), we select the 11 most popular commercial banks which together account for above 90% of the market share in the Vietnam banking sector. Due to regulations about customer database privacy, we could not have access to the full list of customers in these 11 banks. Therefore, a convenience sampling method was employed to draw an initial sample for this study. Specifically, with the support of banking staff, the online questionnaire was sent to 1100 customers of those 11 banks via their emails. Out of 428 filled questionnaires (that indicates the response rate of 38.9%), 391 ones are usable while the remaining 37 ones demonstrate a high probability of response bias (most answers were fixed to a single response, either “Neutral” or “Agree”).

Table 3.

Measurement properties

| Construct | Variable items and codes | Sources of adaptation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Personalization (PER) | PER1 | The product or service was “tailor-made” for me | Bock et al. (2016) |

| PER2 | The product or service was customized to my needs | ||

| PER3 | My bank adapted the type of service to meet my unique needs | ||

| PER4 | My bank offered products and services that I couldn't find in another bank | ||

| PER5 | If I switched to other banks, I wouldn't obtain products and services as customized as I have now | ||

| Interpersonal adaptive behaviour (ADT) | ADT1 | The employee treated me as a unique individual | Bock et al. (2016) |

| ADT2 | The employee tried to “get-to-know” me | ||

| ADT3 | The employee provided me with personal treatment | ||

| ADT4 | The employee communicated with me on a personal basis | ||

| ADT5 | The employee treated me as an individual and not just a number | ||

| Service quality (SER) | SER1 | Services in my bank are usually flawless | Parente et al. (2015) |

| SER2 | When I have a problem, my bank shows interest in solving it | ||

| SER3 | My bank handles my information in a confidential and private manner | ||

| SER4 | My bank’s processes are fast and reliable | ||

| SER5 | Services provided by my bank are delivered as promised | ||

| SER6 | Overall, the quality of services provided by my bank is very good | ||

| Communication (COM) | COM1 | I have an easy and satisfactory relationship with my bank | Ball et al. (2006), Zehir et al. (2011) |

| COM2 | The bank keeps me constantly informed of new products and services that could be in my interest | ||

| COM3 | The bank provides me with good advice | ||

| COM4 | My bank provides me with clear and transparent information | ||

| COM5 | I am happy with the advertising and promotions of this brand | ||

| Customer satisfaction (SAT) | SAT | 5-point Likert scale, from “completely dissatisfied”, “dissatisfied”, “neutral”, “satisfied”, and “completely satisfied” | Bruhn and Grund (2000) |

| Perceived financial well-being (WB) | WB1 | How frequently do you find yourself just getting by financially and living from payslip to payslip? (1 = “All the time” and 5 = “Never” | Gerrans et al. (2014), Losada-Otálora and Alkire (2019) |

| WB2 | How often do you worry about being able to meet normal monthly living expenses? (1 = “Worry all the time” and 5 = “Never worry”) | ||

| WB3 | How do you feel about your current financial situation? (1 = “Feel completely overwhelmed” and 5 = “Feel very comfortable”) | ||

| WB4 | How satisfied are you with your present financial situation? (1 = “Completely dissatisfied” and 5 = “Completely satisfied” | ||

| WB5 | How confident are you that you could find the money to pay for a financial emergency that costs about twice your weekly income? (1 = “No confidence” and 5 = “High confidence”) | ||

| Customer loyalty (LOY) | LOY1 | When considering banking products or services, I consider this bank as my first choice | Beerli et al. (2004), Harris and Goode (2004) |

| LOY 2 | In the future, if I were to need banking products or services, I would contact this company first | ||

| LOY 3 | I would favour the offerings of this bank before others | ||

| LOY 4 | I do not like to change to another bank because I value the selected bank | ||

| LOY 5 | I would always recommend my bank to someone who seeks my advice | ||

The sample structure is shown in Table 3. The research sample is dominated by the age segment from 18 to 49 years old (82.61%) and the female segment (56.01%). About 90.54% of respondents had completed secondary education and above and more than half of them completed tertiary education. The income distribution is relatively proportionate among three segments, including below 10 million VND and above (38.11%); from 10 to less than 15 million VND (35.55%) and above 15 million VND (26.34%). In general, the sampling structure of this study reflects almost all key demographic features of the Vietnamese population who uses banking services as indicated in the Vietnam–Global Financial Inclusion (Global Findex) database proposed by the World Bank (2018). The similarities of this sample to the World Bank database imply the acceptable sample representativeness.

Results

Assessment of measurement model

Based on the guidance for using structural equation modelling (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Churchill 1979), the measurement properties were checked for their reliability and validity before the data could be used for testing research hypotheses. First, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted on AMOS 22 to test the convergent validity of measurement items used for each latent variable. The CFA results for multi-item constructs including personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, communication, service quality, financial well-being, and customer loyalty (See Table 4) reveal that all factor loadings were statistically significant and higher than the threshold value of 0.4. According to Nunnally and Bernstein (1994), all measurement scale items of the six constructs were retained for further exploratory factor analysis (EFA) on SPSS with the principal factor as the extraction method followed by a varimax rotation. The EFA results demonstrated six factors emerged subjected to how these constructs were initially measured. We, therefore, confirmed the construct validity and the unidimensionality of the measurement properties (Straub 1989).

Table 4.

Sampling profile for the quantitative surveyMeasurement properties

| Characteristics | Sampling structure | Population structurea (Percentage) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | Percentage | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 172 | 43.99 | 42.5 |

| Female | 219 | 56.01 | 57.5 |

| Age | |||

| 18–25 | 89 | 22.76 | 12.7 |

| 26–35 | 126 | 32.23 | 25.98 |

| 36–49 | 108 | 27.62 | 23.18 |

| 50–64 | 54 | 13.81 | 22.77 |

| > 64 | 14 | 3.58 | 15.37 |

| Education | |||

| Not attained secondary education yet | 37 | 9.46 | 9.8 |

| Secondary education | 119 | 30.43 | 56.9 |

| Tertiary education | 192 | 49.10 | 33.5 |

| Above tertiary education | 43 | 11.00 | |

| Monthly disposable income | |||

| < VND 5 millionb | 31 | 7.93 | 39.3 |

| VND 5—less than 10 million | 118 | 30.18 | |

| VND 10- less than 15 million | 139 | 35.55 | 60.7 |

| VND 15—less than 20 million | 82 | 20.97 | |

| ≥ VND 20 million | 21 | 5.37 | |

| Employment | |||

| Have a job | 214 | 54.73 | N/A |

| Unemployment | 126 | 32.23 | |

| Retired | 51 | 13.04 | |

aThe overall population structure is extracted from Vietnam–Global Financial Inclusion (Global Findex) database, as published by theWorld Bank (2018)

bEquivalent to 218.81 USD based on the exchange rate (transfer rate) quoted by Vietcombank on the 1st of August 2021 (1USD = 22,850 VND)

The reliability of the six constructs was evaluated through the calculation of Cronbach’s alpha. According to figures shown in Table 5, all the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were greater than 0.7, indicating that the internal consistency or reliability of the constructs was acceptable. On the other hand, the results of the discrimination test as shown in Table 6 revealed that Average Variance Extracted (AVE) indicators of all latent variables, except that for personalization, were greater than the cut-off value of 0.5. Although the AVE indicator of personalization is slightly smaller than 0.5, like other AVE values for the remaining variables, it is much greater than the square of correlations between each of the two constructs. The convergent validity and discriminant validity of the six constructs were, therefore, confirmed (Anderson and Gerbing 1988; Fornell and Larcker 1981).

Table 5.

Sampling profile for the quantitative surveyMeasurement properties

| Construct scale items | Mean | Standard deviation | Factor loading | t-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PER1 | 3.17 | 0.631 | 0.495 | 8.745 |

| PER2 | 3.16 | 0.677 | 0.713 | 12.259 |

| PER3 | 3.21 | 0.672 | 0.651 | 11.318 |

| PER4 | 3.18 | 0.680 | 0.739 | 12.61 |

| PER5 | 2.99 | 0.692 | 0.722 | – |

| ADT1 | 2.76 | 0.690 | 0.743 | 17.221 |

| ADT2 | 3.00 | 0.742 | 0.742 | 17.18 |

| ADT3 | 2.77 | 0.745 | 0.821 | 20.021 |

| ADT4 | 2.68 | 0.854 | 0.647 | 14.15 |

| ADT5 | 2.78 | 0.750 | 0.887 | – |

| SER1 | 3.08 | 0.854 | 0.434 | 9.851 |

| SER2 | 3.59 | 0.717 | 0.666 | 12.261 |

| SER3 | 3.30 | 0.821 | 0.81 | 18.178 |

| SER4 | 3.33 | 0.821 | 0.873 | 15.484 |

| SER5 | 3.41 | 0.817 | 0.956 | 15.198 |

| SER6 | 3.23 | 0.858 | 0.702 | – |

| COM1 | 3.80 | 0.743 | 0.648 | 12.713 |

| COM2 | 3.30 | 0.836 | 0.793 | 15.62 |

| COM3 | 3.18 | 0.847 | 0.636 | 12.375 |

| COM4 | 3.19 | 0.886 | 0.658 | 12.859 |

| COM5 | 3.56 | 0.826 | 0.832 | – |

| FWB1 | 3.30 | 0.795 | 0.759 | – |

| FWB2 | 3.30 | 0.804 | 0.804 | 16.321 |

| FWB3 | 3.16 | 0.826 | 0.716 | 13.951 |

| FWB4 | 3.26 | 0.827 | 0.888 | 18.229 |

| FWB5 | 3.26 | 0.813 | 0.857 | 17.516 |

| LOY1 | 2.84 | 0.704 | 0.554 | – |

| LOY2 | 2.92 | 0.788 | 0.786 | 11.444 |

| LOY3 | 3.13 | 0.847 | 0.73 | 11.011 |

| LOY4 | 2.98 | 0.815 | 0.974 | 11.998 |

| LOY5 | 2.93 | 0.794 | 0.814 | 12.785 |

Measurement model fit details: CMIN/df 1.912, p .000, RMR 0.033, GFI 0.884, CFI 0.946, AGFI 0.860, RMSEA 0.048, PCLOSE 0.695, “–” denotes loading fixed to 1

Table 6.

Reliability and correlation of constructs

| PER | ADT | SER | COM | FWB | LOY | Reliability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PER | 1 | 0.797 | |||||

| ADT | 0.110 | 1 | 0.873 | ||||

| SER | 0.102 | 0.069 | 1 | 0.886 | |||

| COM | 0.134 | 0.098 | 0.101 | 1 | 0.852 | ||

| FWB | 0.107 | 0.133 | 0.118 | 0.071 | 1 | 0.903 | |

| LOY | 0.049 | 0.057 | 0.023 | 0.034 | 0.054 | 1 | 0.871 |

In addition, a CFA on the six-factor model also demonstrated a good model fit (CMIN/df = 1.912; p = 0.000; RMR = 0.033; GFI = 0.884; CFI = 0.946; AGFI = 0.860; RMSEA = 0.048; PCLOSE = 0.695).

Based on the above results, we decided to retain the original pool of measurement properties as shown in Table 7 to further test the research hypotheses.

Table 7.

Average Variance Extracted and discriminant validity test

| PER | ADT | SER | COM | FWB | LOY | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PER | 0.498 | |||||

| ADT | 0.0121 | 0.630 | ||||

| SER | 0.0104 | 0.0048 | 0.607 | |||

| COM | 0.0180 | 0.0096 | 0.0102 | 0.589 | ||

| FWB | 0.0114 | 0.0177 | 0.0139 | 0.0050 | 0.651 | |

| LOY | 0.0024 | 0.0032 | 0.0005 | 0.0012 | 0.0029 | 0.636 |

The numbers in bold represent AVE values

Descriptive statistics and differences among demographic segments

Appendix 1 presents the descriptive statistics for PER, ADT, SER, COM, SAT, WB, and LOY. Detailed frequencies of responses are provided in Appendix 2. In general, the majority of respondents evaluate their banks’ abilities to personalize products and services and demonstrate interpersonal adaptive behaviour, service quality and communication quality at medium levels (mostly ranked as 3 based on the Likert scale). Despite the Covid-19 crisis, it is interesting to see that most respondents feel neutral about their financial health. Likewise, the majority of the respondents are generally happy with their banks and demonstrate a medium or above the medium level of loyalty (mostly rank as 3 and 4 based on the Likert scale).

To provide more insights into the differences among demographic groups regarding their banking experience, we further conducted an independent sample t-test for potential differences between males and females, and One-way ANOVA tests for testing differences among age, income, education and employment status groups regarding their perceptions towards each construct in the conceptual model. The estimation results of those tests are presented in Appendices 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7, respectively. The statistics indicate that there is no significant difference among all of these demographic groups regarding their perceptions towards neither banking experiences, their satisfaction and loyalty to their current banks, or financial well-being, except for interpersonal adaptive behaviour among education groups (See Appendix 6). Specifically, the descriptive statistics of interpersonal adaptive behaviour across education levels show that bank customers who have not attained secondary education yet evaluate their banks’ abilities to demonstrate interpersonal adaptive behaviour at the highest levels, as compared to other education groups. In contrast, those who attain above tertiary education are the most demanding segment regarding interpersonal adaptive behaviour. They rank this feature at the lowest level, compared to other counterparts. (See Panel B, Appendix 6).

Hypothesis testing for the whole sample

SEM analysis was adopted to allow both direct and indirect hypothesized relationships as shown in Fig. 1 to be tested (Oh 1999). The path analysis was conducted in AMOS 22 for estimating the significance and magnitude of each hypothesized relationship. The model fit indicators as resulted in AMOS 22 show that the proposed model demonstrates a reasonably good fit to the data.

According to statistical results shown in Table 8, all the three factors including personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, and service quality have direct positive impacts on customer satisfaction which, in turn, positively affects perceived financial well-being (Accept H1a, H1b, H1d, and H2). Meanwhile, there is no significant relationship between communication and neither customer satisfaction nor financial well-being found (reject H1c and H3c). On the other hand, the estimation results also affirm the direct positive effect of financial well-being on customer loyalty (accept H4).

Table 8.

Path coefficients for the whole sample

| Construct path | Model 1 (original) | Model 2 (without SAT) | Model 3 (without FWB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PER→SAT | 0.303* | – | 0.304* |

| ADT→SAT | 0.199* | – | 0.200* |

| SER→SAT | 0.242** | – | 0.241** |

| COM→SAT | 0.013 | – | 0.013 |

| SAT→FWB | 0.582** | – | – |

| PER→FWB | 0.103* | 0.260* | – |

| ADT→FWB | 0.097** | 0.209** | – |

| SER→FWB | 0.043 | 0.223** | – |

| COM→FWB | 0.007 | 0.013 | – |

| SAT→LOY | 0.079 | – | 0.091** |

| FWB→LOY | 0.271** | 0.175** | – |

| Fit indices | – | ||

| CMIN/df | 2.058 | 1.915 | 1.923 |

| CFI | 0.938 | 0.945 | 0.949 |

| GFI | 0.873 | 0.883 | 0.898 |

| AGFI | 0.848 | 0.860 | 0.875 |

| RMR | 0.037 | 0.038 | 0.043 |

| RMSEA | 0.052 | 0.048 | 0.049 |

| PCLOSE | 0.235 | 0.686 | 0.639 |

“–” means the construct path between the two variables is not examined since one of them was removed from the original model

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001

In order to test the mediation effects of customer satisfaction in the impacts of personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, and service quality on perceived financial well-being, we follow mediating analysis as suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986). Specifically, path coefficients resulting from the original model (Model 1) and that of Model 2 (where customer satisfaction is absent) were compared to test for mediating conditions.

Results shown in Table 8 indicate that:

When customer satisfaction is absent (Model 2), all personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, and service quality positively affect perceived financial well-being.

In the original model (Model 1), both personalization and interpersonal adaptive behaviour have positive impacts on perceived financial well-being. However, those relationships are significantly weaker compared to that of Model 2 (without customer satisfaction).

Service quality demonstrates an insignificant effect on perceived financial well-being as customer satisfaction is included in the model.

These results indicate that customer satisfaction partially mediates the relationships between either personalization or interpersonal adaptive behaviour and perceived financial well-being while totally mediates the impact of service quality on perceived financial well-being (accept H3a, H3b, and H3d).

Similarly, Model 3 where financial well-being is absent is constructed to test the mediation role of this variable in the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty, following the guidance of Baron and Kenny (1986). The estimation results as shown in Table 8 indicate that both customer satisfaction and perceived financial well-being have positive impacts on customer loyalty. However, the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty is significantly weaker when financial well-being is included in the model (Model 1) as compared to that when this variable is absent (Model 3). We, therefore, conclude that financial well-being partially mediates the relationship between customer satisfaction and customer loyalty (accept H5).

Hypothesis testing for subsamples of private banks’ customers and public banks’ customers

In order to provide more insights into the interrelationships among constructs, we separate the sample into the subsample of private banks’ customers (165 observations) and that of public banks’ customers (226 observations) and compare the factor ranks for the two subsamples. Tables 9 and 10 present the path coefficients for the two subsamples.

Table 9.

Path coefficients for the subsample of private banks’ customers

| Construct path | Model 1 (original) | Model 2 (without SAT) | Model 3 (without FWB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PER→SAT | 0.273* | – | 0.273* |

| ADT→SAT | 0.116 | – | 0.115 |

| SER→SAT | 0.218* | – | 0.217* |

| COM→SAT | 0.065 | – | 0.065 |

| SAT→FWB | 0.557** | – | – |

| PER→FWB | 0.063 | 0.229* | – |

| ADT→FWB | 0.076** | 0.164** | – |

| SER→FWB | 0.020 | 0.205* | – |

| COM→FWB | 0.002 | 0.013 | – |

| SAT→LOY | 0.067 | – | 0.034 |

| FWB→LOY | 0.174* | 0.083* | – |

| Fit indices | – | ||

| CMIN/df | 1.493 | 1.478 | 1.462 |

| CFI | 0.942 | 0.942 | 0.949 |

| GFI | 0.811 | 0.814 | 0.836 |

| AGFI | 0.773 | 0.777 | 0.798 |

| RMR | 0.049 | 0.049 | 0.051 |

| RMSEA | 0.055 | 0.054 | 0.053 |

| PCLOSE | 0.181 | 0.230 | 0.311 |

“–” means the construct path between the two variables is not examined since one of them was removed from the original model

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001

Table 10.

Path coefficients for the subsample of public banks’ customers

| Construct path | Model 1 (original) | Model 2 (without SAT) | Model 3 (without FWB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PERSAT | 0.305* | – | 0.307* |

| ADT→SAT | 0.250* | – | 0.251* |

| SER→SAT | 0.248** | – | 0.246** |

| COM→SAT | 0.049 | – | 0.040 |

| SAT→FWB | 0.571** | – | – |

| PER→FWB | 0.117* | 0.253* | – |

| ADT→FWB | 0.087 | 0.212** | – |

| SER→FWB | 0.044 | 0.174** | – |

| COM→FWB | 0.011 | 0.015 | – |

| SATLOY | 0.050 | – | 0.135** |

| FWBLOY | 0.298* | 0.253** | – |

| Fit indices | – | ||

| CMIN/df | 1.974 | 1.851 | 1.862 |

| CFI | 0.903 | 0.915 | 0.921 |

| GFI | 0.85 | 0.827 | 0.846 |

| AGFI | 0.777 | 0.793 | 0.810 |

| RMR | 0.041 | 0.042 | 0.046 |

| RMSEA | 0.066 | 0.061 | 0.062 |

| PCLOSE | < 0.001 | 0.003 | 0.008 |

“–” means the construct path between the two variables is not examined since one of them was removed from the original model

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.001

In the original model (Model 1), personalization and service quality have significant positive effects on customer satisfaction only among customers of private banks. Meanwhile, not only personalization and service quality but also interpersonal adaptive behaviour positively influence the satisfaction of the public banks’ customers. Customer satisfaction is found to have a significant positive impact on perceived financial well-being for two subsamples. Similarly, customers of either private or public banks who have better perceived financial well-being demonstrate significantly higher loyalty to their current banks.

In comparison between coefficients as yielded from Model 1 (the original model) and that of Model 2 (where customer satisfaction is absent), it is found that:

Personalization has a significant positive effect on customer satisfaction in two subsamples. For customers of the private banks, the positive impacts of this construct on perceived financial well-being (as in Model 2) become insignificant when customer satisfaction is included (as in Model 1). Likewise, for the subsample of public banks’ customers, the contribution of this construct to perceived financial well-being (as in Model 2) is still significant but weaker when customer satisfaction is included (as in Model 1).

For both two subsamples, service quality has a significant positive effect on customer satisfaction. In addition, the positive impact of this construct on perceived financial well-being (as in Model 2) becomes insignificant when customer satisfaction is included (as in Model 1).

Interpersonal adaptive behaviour significantly and positively affects satisfaction among customers from the public banks only. For this customer segment, the positive impact of this construct on perceived financial well-being (as in Model 2) becomes insignificant when customer satisfaction is included (as in Model 1).

Based on the mediating conditions as suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986), it is concluded that customer satisfaction totally mediates the impact of personalization on perceived financial well-being among private banks’ customers and partially mediates such a relationship among public banks’ customers. Similarly, the relationship between service quality and perceived financial well-being is totally mediated by customer satisfaction in both two subsamples. For the segment of public banks’ customers, customer satisfaction totally mediates the effect of interpersonal adaptive behaviour on perceived financial well-being. In contrast, communication has no significant impact on neither customer satisfaction nor financial well-being for the two subsamples. Although interpersonal adaptive behaviour does not affect the satisfaction of private banks’ customers, it significantly and positively influences the perceived financial well-being of this customer segment. The relationship between interpersonal adaptive behaviour and perceived financial well-being, therefore, does exist among customers of private banks but is not mediated by customer satisfaction.

In comparison between coefficients as yielded from Model 1 and that of Model 3 (where financial well-being is absent), it is found that satisfaction has a significant positive impact on customer loyalty among public banks’ customers only (as in Model 3). This relationship turns out to be insignificant when perceived financial well-being is included (as in Model 1). Based on the mediating conditions as suggested by Baron and Kenny (1986), financial well-being totally mediates the relationship between customer satisfaction and bank loyalty. Nevertheless, in the private bank sector, customer satisfaction demonstrates no significant influence on bank loyalty in both two models.

Discussion and managerial implication

This study expands the existing knowledge about determinants of perceived financial well-being to give insights into how perceived financial well-being could be influenced by contextual factors rather than individual factors as examined in numerous previous studies. Specifically, under the basic psychological need theory (Ryan 1995; Ryan and Deci 2000; Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013), this research extends the findings of Losada-Otálora and Alkire (2019) to examine the combined impacts of personalization, interpersonal adaptive behaviour, communication, and service quality on perceived financial well-being and the mediating effect of customer satisfaction in these relationships. We also extend the existing knowledge regarding the behavioural consequences of perceived financial well-being in the context of the banking sector by examining the direct relationship between perceived financial well-being and customer loyalty as well as the mediating role of perceived financial well-being in the satisfaction-loyalty linkage. The results show that the personalization of service offerings, interpersonal adaptive behaviour of bank employees and service quality help satisfy bank customers’ needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence in their financial life. On the one hand, this directly helps reduce current financial stress and ensure financial security for future consumption, hence, enhancing the subjective perception of financial well-being. On the other hand, this also enriches customer satisfaction towards the experience of financial products and services, a crucial domain of financial life, thus, indirectly contributing to the satisfaction of the financial state in general. These findings are consistent with the core propositions of basic psychological need theory (Ryan and Deci 2000; Vansteenkiste and Ryan 2013) and the linkage between customer satisfaction and well-being as suggested by Choi et al. (2007), Christopher et al. (2007) and Wang (2008). While most previous studies focus on individual factors such as demographic characteristics, the ability to control spending, financial needs, or financial literacy when examining determinants of perceived financial health (Chatterjee et al. 2019; Gutter and Copur 2011; Kiymaza and Öztürkkal 2019; Ponchio et al. 2019; Riitsalu and Murakas 2019; Shim et al. 2009) or the use of specific financial services, such as cash advance, loans from banks or credit cards (Chan et al. 2012; Norvilitis and Mao 2013; Yam and Shintaro 2018; Braun Santos et al. 2016), our findings are notable that they reveal the crucial role of commercial banks, as providers of financial services on perceived financial well-being with controllable bank-related factors. Further, one’s favourable perception of financial well-being discourages them from changes, instead, gears them towards loyalty to current banks that could help them maintain a positive financial state as they desire. This tendency is consistent with “the prevention focus” as mentioned in the self-regulatory focus theory (Higgins 1997, 1998) or “the loss-avoidance behaviour”, as featured in the self-regulatory model (Baltes and Baltes 1990; Ebner et al. 2006; Freund et al. 2012; Rothman 2000; Rothman et al. 2011). As financial life is also a crucial domain of subjective well-being, our finding is also consistent with Luhmann and Hennecke (2017) who affirms that those with high levels of subjective well-being have less desire for change. Moreover, in line with the social exchange theory (Blau 1964), we find that the satisfaction of psychological needs in one’s financial life could enhance perceived financial well-being. The positive emotion resulting from achieving the desired level of financial health would, in turn, act as a psychological reward for staying with current banks that discourages switching behaviours. In this regard, our findings affirm that perceived financial well-being also takes the role of a mediator that helps explain the fundamental path in bank marketing, from customer satisfaction to loyalty. This finding is relatively in line with a popular strand of research which employs the mediating role of switching costs to justify the relationship between customer satisfaction and loyalty (Chiguvi and Guruwo 2017; Edward and Sahadev 2011; Hoang and Nguyen 2018; Ngo et al. 2019; Nguyen et al. 2020; Willys 2018).

To give more insights into the interrelationship between bank-related factors and financial well-being, we retest the conceptual model for the subsample of private banks’ customers and that of public banks’ customers. The results show that the personalization of service offerings, interpersonal adaptive behaviour of bank employees, and service quality help enhance the subjective financial well-being among customers of both private and state-owned banks. For both two segments, the ability to personalize banking services and products demonstrates the strongest determinant of subjective financial health, as compared to interpersonal adaptive behaviour and service quality. Among customers of public banks, those relationships could be explained by their effects on overall customer satisfaction. However, in the case of private banks’ customers, the positive impact of interpersonal adaptive behaviour on perceived financial well-being is not mediated by the level to which customers’ needs are satisfied. These findings indicate that for private banks, satisfying customers’ financial needs is not the key to ensuring their perceived financial well-being, as in the case of state-owned banks. Instead, there exists a different mechanism underlying the relationship between interpersonal adaptive behaviour and subjective financial health. Interestingly, perceived financial well-being is merely a mediator in the satisfaction-loyalty linkage among public banks’ customers. Meanwhile, it works as a key determinant of customer loyalty, instead of customer satisfaction, for the segment of private banks’ customers. The finding of an insignificant impact of customer satisfaction on bank loyalty, as found among customers of private banks, is consistent with Mohsan et al. (2011). This may be because state-owned banks have dominated the Vietnam banking sector and attained customer trust as the best choice for financial services. Therefore, bank customers use state-owned banks mostly to meet their financial needs. Correspondingly, satisfying them is the central route to customer retention. Meanwhile, private banks, as the second-best choice, are likely selected by customers who have a higher tendency for variety-seeking behaviour (Sheorey et al. 2014; Shirin 2011). Those customers tend to look for diverse banking experiences rather than become loyal to a specific bank even when their financial needs are satisfied.

On the policy front, this research offers important inösights for bank marketing practitioners from the societal marketing perspective. Specifically, financial well-being, as an inner state, is not only shaped by various individual factors but also influenced by commercial banks, as the provider of financial services. Since positive feeling about financial health could promote socially responsible behaviours, enhancing perceived financial well-being not only bring about immediate satisfaction and offer long-run benefits to the customers but also create value for the society at large. In addition, supporting customers to reach the desired state of their financial life should be included in the retaining programs of commercial banks for capturing more lifetime customer value. Enhancing customers’ perception of financial health is even more crucial to building customer loyalty in the private bank sector where satisfying customers is not enough to retain them. This work suggests several ways for either the private or state-owned banks to increase perceived financial health of their customers. First, the banking products and services themselves provide tools and solutions for customers’ financial needs, either immediate or future consumption. Therefore, ensuring reliable and consistent service quality is a simple strategy to satisfy customers and arouse a sense of effectiveness that makes them believe more in their self-efficacy in sustaining good financial health, with the use of banking services. Second, besides necessary strict banking regulations and procedures, commercial banks should leave rooms for customization to adapt to specific wants and concerns of customers where possible. Through personalization, the banks could make customers confident that every personal financial issue could be resolved by using banking services and products that are highly customized for them. This may create a sense of freedom and mastery in which bank customers strongly believe in their abilities to control financial conditions without constraints and hence, form more favourable subjective financial well-being. Third, commercial banks should provide training programs to their front staff and encourage them to demonstrate interpersonal adaptive behaviours during the process of customer interaction. This proactive strategy could enrich customer experience of relatedness that could neutralize their worry about financial problems. Specifically, the provision of personal treatment and care would make the customers believe that their financial issues could be shared, listened to, and resolved by their banks. In other words, the banks act as “good friend” who is always there for them and can help them reduce stress. In fact, all these strategies are aligned to every bank’s fundamental business objective since they help enhance both customer satisfaction and loyalty—key marketing metrics that drive sustainable revenue growth.

Limitations and future research