Abstract

Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is the most severe and disabling form of tuberculosis (TB), with at least 100,000 cases per year and a mortality rate of up to 50% in individuals co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). To evaluate the efficacy and safety of an intensified anti-tubercular regimen and an anti-inflammatory treatment, the INTENSE-TBM project includes a phase III randomised clinical trial (TBM-RCT) in four countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Within this framework, we designed a comprehensive capacity-building work package ensuring all centres had, or would acquire, the ability to conduct the TBM-RCT and developing a network of skilled researchers, clinical centres and microbiology laboratories. Here, we describe these activities, identify strengths/challenges and share tools adaptable to other projects, particularly in low- and lower-middle income countries with heterogeneous settings and during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Despite major challenges, TBM-RCT initiation was achieved in all sites, promoting enhanced local healthcare systems and encouraging further clinical research in SSA. In terms of certified trainings, the achievement levels were 95% (124/131) for good clinical practice, 91% (39/43) for good clinical laboratory practice and 91% (48/53) for infection prevention and control. Platform-based research, developed as part of capacity-building activities for specific projects, may be a valuable tool in fighting future infectious diseases and in developing high-level research in Africa.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40121-022-00667-z.

Keywords: Africa, Capacity building, Clinical research, HIV, INTENSE-TBM, Tuberculous meningitis

Plain Language Summary

The INTENSE-TBM project aimed to design a comprehensive work-package on capacity building, ensuring all centres would acquire the ability to conduct a phase III randomised clinical trial on TBM in sub-Saharan Africa, to reduce tuberculous meningitis mortality and morbidity in patients with/without HIV-1 co-infection. Therefore, the INTENSE-TBM project is an example of how an international clinical research consortium can provide opportunities to enhance local capacity building and promote centres without previous experience in clinical research. This article provides practical approaches for implementing effective capacity-building programmes. We highlight how to overcome limitations imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic to successfully complete clinics, laboratory set-ups and personnel training, so as to optimise resources and empower African institutions on a local level. At the same time, our experience shows how capacity-building programmes can deliver long-lasting impact that extends beyond the original aims of the project (e.g. HIV and TB), and support local health systems in fighting other infectious disease (e.g. COVID-19). Research projects in low- and lower-middle income countries with heterogeneous settings could stand to benefit the most.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40121-022-00667-z.

Key Summary Points

| Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is the most severe and disabling form of tuberculosis. |

| The INTENSE-TBM project includes a phase III randomised clinical trial on TBM in sub-Saharan Africa. Using a factorial design, the INTENSE-TBM is evaluating the efficacy of an intensified anti-tubercular treatment (increased rifampicin dose and added linezolid during intensive phase vs. WHO standard regimen) and an anti-inflammatory treatment (aspirin vs. placebo), with a view to reducing TBM mortality and morbidity in patients co-infected/not co-infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). |

| We aimed to design a comprehensive work-package on capacity building, ensuring all centres would acquire the ability to conduct a phase III randomised clinical trial on TBM in sub-Saharan Africa. |

| The initiation of the INTENSE-TBM clinical trial was achieved at all sites - despite major challenges imposed by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic - enhancing local healthcare systems and encouraging further clinical research in sub-Saharan Africa. |

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) is one of the worldwide leading causes of death from a single infectious agent. A quarter of the world’s population carries Mycobacterium tuberculosis (M.tb), of whom about 10% progress to active TB. According to the latest global report [1], ten million people became ill with the disease in 2020; among these, 8% were people living with human immunodeficiency virus (PLWH), a population with a higher risk of developing the disease. The most common clinical presentation is pulmonary TB, which affects the lungs, although other organs are susceptible to extrapulmonary TB. The most severe and disabling form of TB is tuberculous meningitis (TBM), which causes illness in at least 100,000 people each year. In areas of high TB/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence, as many as 50% of TBM cases may be in patients co-infected with HIV type 1 (HIV-1), in which the mortality rate can also approach 50%, with severe disability frequently affecting survivors [2–4]. Indeed, TBM outcomes reflect the existing gaps in TB healthcare, which more severely impact PLWH: from incidence to diagnosis (inadequate or unavailable tools), from diagnosis to treatment (delays/subsequent only to neurological damage) and from treatment initiation to successful outcome (suboptimal treatment, inadequate management of drug toxicities and insufficient integration of TB/HIV services) [2–6]. The way forward, therefore, urgently requires investment via clinical research and capacity building [3, 4, 7–9].

INTENSE-TBM (https://intense-tbm.org/) is a 5-year international project with the aim to improve the overall care of patients with TBM. It includes a phase III multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial (‘TBM-RCT’; ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04145258) in four countries in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Using a factorial design, the INTENSE-TBM is evaluating the efficacy of an intensified anti-tubercular treatment (increased rifampicin dose and added linezolid during intensive phase vs. WHO standard regimen) and an anti-inflammatory treatment (aspirin vs. placebo), with a view to reducing mortality and morbidity in patients with TBM co-infected/not co-infected with HIV.

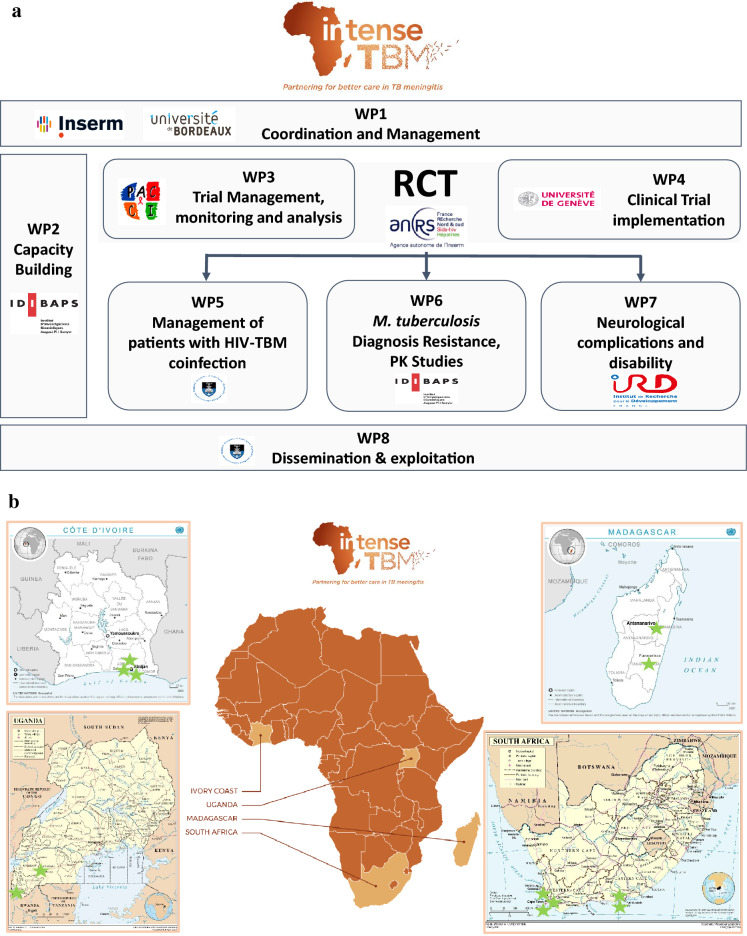

The project encompasses eight highly interactive work programmes (Fig. 1a), each led or co-led by an SSA partner. With a focus on capacity building, the second workpackage (WP2-CB) coordinates and organises the activities, approaches, strategies and methodologies that will help researchers, clinical centres and laboratories enhance performance, foster development and achieve two main objectives: (1) align participating centres’ capacity (infrastructure, equipment, network) and capabilities (skills, training, know-how) with INTENSE-TBM criteria, and (2) develop a network of skilled researchers, clinical centres and microbiology laboratories not only to facilitate TBM-RCT roll-out but also to conduct future clinical research. To achieve these aims, WP2-CB was structured around four main tasks: (1) establishing clinical centres; (2) establishing microbiology laboratories; (3) conducting training on good clinical practice/good clinical laboratory practice (GCP/GCLP); and (4) conducting training on infection prevention and control (IPC).

Fig. 1.

a Work-packages in the INTENSE-TBM project. INTENSE-TBM is organised in 8 work-packages (WP). WP1 is related to the overall coordination and management of the project. WP2 is a longitudinal package with the aim to provide the required infrastructures, resources and trainings before, during and after the randomised controlled trial (RCT), with the ultimate aim that the created capacities be permanently used to reinforce the local health systems in these countries. WP3 and WP4 are related to the clinical trial implementation and development. WP5–8 are related to specific clinical, laboratory or research issues. INTENSE-TBM project website: https://intense-tbm.org/. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04145258. HIV Human immunodeficiency virus, PK pharmacokinetics, TBM tuberculous meningitis, b African sites participating in the INTENSE-TBM clinical trial.

INTENSE-TBM began on 1 January 2019, and initial patient recruitment was expected in the first half of 2020. However, this period saw the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic imposing huge challenges on healthcare services worldwide; these were acutely felt in developing countries and significantly delayed the initiation of research projects. In this article, we report on our capacity-building activities (development/successful completion), identifying our strengths and challenges and describing our tools and how they are adaptable to other projects, particularly in low- and lower-middle income countries (LMIC) with their heterogeneous settings and in the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

This article is based on authors’ knowledge and experiences prior to conducting clinical research and, therefore, it does not contain any data from human participants or animals. Written consent was obtained from the individuals shown in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Research laboratory built at the Centre d’Infectiologie Charles Mérieux (CICM) in Madagascar. Picture taken during remote study initiation visit

Clinical Research in Heterogeneous, COVID-19 Contexts

The INTENSE-TBM is designed to be conducted in 12 clinical centres in four SSA countries: three in the Ivory Coast, two in Madagascar, five in South Africa and two in Uganda (Fig. 1b). Centres were selected according to the experience of clinicians in TBM management, participatory feasibility and geographical distribution (TB/HIV burden varies across western, eastern and southern Africa). Most sites were already experienced in clinical research (n = 10), whereas others (n = 2) required comprehensive development. Further, our in-detail evaluation of the sites identified a high level of heterogeneity, both among countries and within each participating country, between referral and regional centres. In the light of these features, our capacity-building activities had to be tailored to each individual centre, taking into close account geographical location, levels of infrastructure and resource centralisation, network access to other institutions and existing international collaborations.

In addition to these structural factors, the COVID-19 pandemic also forced centres to suspend many aspects of their activities and adapt to the prevailing circumstances, including:

staff shortages;

restrictions on air-traffic and at borders;

delays in receiving equipment;

supply shortages;

local movement restrictions;

missed deadlines for external quality programmes and equipment maintenance;

resorting to remote technical support and monitoring visits;

resorting to online training;

lockdowns, making it difficult for patients to attend facilities and raising the fear of attending such facilities.

in Cape Town (South Africa), the research ethical committee also suspended non-COVID-19 trials and the faculty banned non-COVID-19 laboratory research.

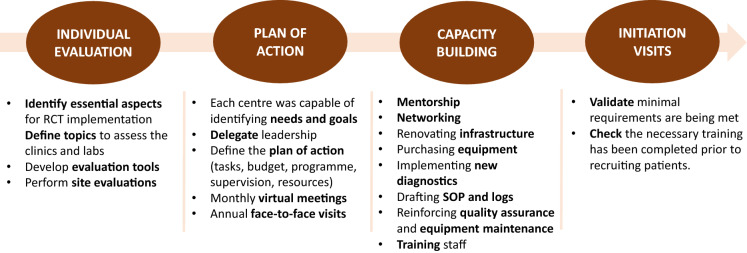

Methodological Approach for Capacity Building

To ensure capacity building was tailored, the activities relating to site preparation were divided into four phases (Fig. 2). This ensured that, despite the differences among centres, all centres met the same criteria and the requirements for INTENSE-TBM development. By the end of phase 1, the essential aspects of TBM-RCT implementation were defined and evaluation tools were developed. In phase 2, each centre was empowered to identify its own needs and to define its own action plan in accordance with those needs. In this way, we delegated leadership to each national country team, supporting and monitoring their activities through monthly virtual meetings and annual face-to-face visits which were scheduled up to project completion. In phase 3, the following strategies were applied:

mentorship from experienced research institutions (national and international);

networking among sites, such as resource optimisation and sample transfer;

infrastructure renovation;

purchasing equipment;

supporting implementation of diagnostic techniques;

drafting standard operational procedures (SOP) and logbooks;

reinforcing quality assurance;

reinforcing equipment maintenance;

training staff.

Fig. 2.

Methodological approach to capacity building. SOP Standard operational procedure

In phase 4, initiation visits were conducted to check that sites complied with all the requirements and that training had taken place prior to recruiting the first patients.

Specific Capacity-Building Tasks

As described in the Introduction, WP2-CB was structured around four main tasks, explained in the following subsections.

To Establish Clinical Centres

The INTENSE-TBM project began in February 2021, and currently all 12 sites have been successfully initiated (Fig. 1b).

Ivory Coast

Patient recruitment in the Ivory Coast is being carried out by three university hospitals located in the capital city of Abidjan, although research is conducted at the Service des Maladies Infectieuses et Tropicales (SMIT) and the Centre de Diagnostic et de Research sur le SIDA et les autres maladies infectieuses (CeDReS), also located in Abidjan. SMIT and CeDRes are supported by Mereva, a bilateral clinical trial unit between Ivory Coast (PAC-CI, Treichville Hospital and Abidjan University) and France (Bordeaux University and INSERM). The existence of these previous international collaborations presumably led to the main capacity building interventions being readily achieved, and this country was the first to have all sites operational in February 2021.

Madagascar

Two university hospitals in two regions in Madagascar were selected for INTENSE-TBM participation, both of which already part of collaborations with the Centre d’Infectiologie Charles Mérieux de Madagascar (CICM) and the Institut Pasteur de Madagascar (IPM). These latter two national research institutions granted access to HIV viral load and M. tb culture resources, albeit only through physical presence in the capital city of Antananarivo. Indeed, the main challenges in this context were lack of experience in clinical trials, resource decentralisation, infrastructure deficits and travel times between regional and reference centres. At the time of writing, both sites are up and running (Antananarivo in January 2021 and Fianarantsoa in July 2021).

South Africa

There are five participating hospitals in South Africa, all in the region of Cape Town and Port Elizabeth. These institutions work closely with the University of Cape Town (UCT), which has an established clinical research team and recognised researchers in HIV/TB whose work includes the LASER-TBM (NCT03927313) phase II clinical trial evaluating the safety and tolerability of increased dosages of rifampicin and adjunctive linezolid with or without aspirin for HIV-associated TBM. It is this trial that will supply the relevant safety information to INTENSE-TBM. Given this context, all capacity-building activities were in place: INTENSE-TBM activities would follow on from the LASER-TBM trial. All five sites were initiated between March and June 2021.

Uganda

The INTENSE-TBM involve two regional reference hospitals in Uganda, one in Mbarara at the Mbarara Regional Reference Hospital (MRRH) and one in Kabale at the Kabale Regional Reference Referral Hospital (KRRH). MRRH is the teaching hospital of the Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST). MUST hosts the Epicentre Uganda Research Centre of the research organisation Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF)-Epicentre, and this collaboration has been conducting clinical research on HIV/TB for more than 10 years. Conversely, KRRH has never participated in clinical trials and therefore has required comprehensive training, infrastructure renovation, additional resources (including essentials, such as internet, stable power supply) and systems for quality control and documentation. MRRH was the first site initiated (August 2021), followed by KRRH (February 2022), with the delay due to institutions and local borders being temporarily closed due to COVID-19.

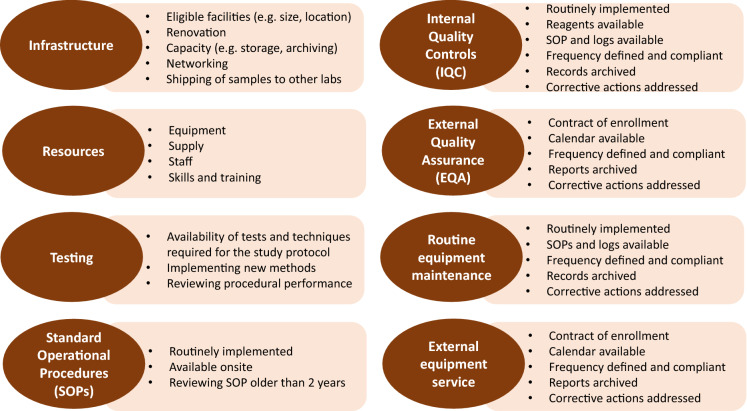

To Establish Microbiology Laboratories

Minimum requirements (Fig. 3) for compliance with the study protocol, standard guidelines and GCLP were defined to standardise laboratory performance and to ensure confidence in the research to be conducted. [10–12].

Fig. 3.

Requirements applied to laboratory standardisation

Ivory Coast

The analytical procedures in the Ivory Coast are centralised at CeDReS, a reference laboratory involved in international research, which already had the infrastructure, equipment and resources to participate in the INTENSE-TBM. In terms of procedure, Xpert MTB/RIF (a WHO-recommended first-line TB diagnosis test, which is PCR-based and allows simultaneous M.tb-DNA/rifampicin-resistance detection) [13] was upgraded to the more sensitive Ultra version [14], and drug susceptibility testing (DST) for pyrazinamide was introduced. Overall, capacity-building activity focused on enhancing quality, maintenance and documentation systems. Notably, 42% (15/36) of the required standard operating procedures (SOPs) had to be drafted, and 58% (21/36) needed reviewing as they were > 2 years old. CeDReS was already enrolled in an external quality assurance programme, and its equipment was being serviced annually by accredited technicians, despite the challenge of procuring this service domestically.

Madagascar

The main challenges in Madagascar were related to renovating infrastructure, purchasing equipment, establishing laboratory networks, providing training and introducing diagnostic techniques. A research laboratory was built at CICM (Fig. 4). BACTEC MGIT960 (a WHO reference phenotypic method for M.tb bacteriological confirmation and DST, based on liquid culture) [15] was introduced at IPM, and Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra was scaled-up in the regional TB laboratories. The regional sites underwent significant renovations, particularly the regional TB laboratory, all of which were necessary to improve staff well-being and ensure the proper functioning of the installations.

South Africa

The laboratories were already operational in South Africa and were conducting a similar trial. Therefore, our approach was simply to adapt those procedures to the INTENSE-TBM trial.

Uganda

MSF-Epicentre already acts as a reference laboratory in Uganda, and it satisfied the infrastructure and resource criteria for the INTENSE-TBM trial, such as presence of staff with experience in clinical research. All diagnostic tests are available, except for the HIV viral load test and M.tb DST; both will be tested at the national reference laboratory. In this context, capacity building translated into providing support to the implementation of INTENSE-TBM and at the same time upgrading laboratory performance. By contrast, Uganda’s second site had never participated in clinical research, receives little external support and faces the common problems of regional districts (excessive workloads, limited staffing and resources, frequent supply interruptions, unstable power supply, lack of internet, etc.). Work is currently ongoing to complete the capacity-building activities at KRRH. At the time of writing, only rapid diagnostic tests are done. A referral system for samples to be tested at MSF-Epicentre has also been put in place.

To Provide training on GCP and GCLP Training

GCP is an international ethical and scientific quality standard for designing, conducting, recording and reporting trials that involve the participation of human subjects. This standard provides assurance that the rights, the safety and the well-being of subjects are protected, and that trial data are credible [16]. GCLP applies GCP principles to laboratory practice regarding sample analysis, and ensuring the reliability and integrity of data generated by analytical laboratories [12]. Accordingly, GCP and/or GCLP certification (valid for 3 years) was a requirement for all staff involved in INTENSE-TBM. Where GCP certification was unavailable, alternative GCP training modalities were offered depending on previous experience: (1) online (through the Training and Resources in Research Ethics Evaluation); (2) on-site (according to national availability of accredited institutions); (3) hybrid (local team working face-to-face on-site and external experts working online). Regarding GCLP, not one person was found to be certified, and online training was recommended through the Global Health Network. GCP and GCLP certification achievement levels were 95% (124/131) and 91% (39/43), respectively, reflecting the sites at initiation.

To provide Training on IPC

IPC is a practical approach to protecting patients and healthcare workers from harm due to avoidable/preventable infections [17, 18]. This specialised training was provided to all sites by the Infection Control African Network, which is based in South Africa, because difficulties in procuring the service were reported in the other countries. Due to budgetary concerns (and lately pandemic-related restrictions), it was decided to deliver the bilingual French/English course online, covering the essential contents of IPC with a focus on TB. In total, 91% (48/53) of healthcare workers completed the course successfully.

The overview of activities initially planned and the modifications introduced to face the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Overview of activities initially planned and modifications introduced to face the COVID-19 pandemic

| List of activities | Before COVID-19 | After COVID-19 |

|---|---|---|

| Meetings |

Routine meetings online Annual investigators meeting centralised in 1 country (e.g. kick-off meeting in Ivory Coast) |

All meetings online Budget saved will cover part of the COVID-19 unexpected expenses |

| Visits and monitoring activities |

On-site displacement of national/international staff On-site evaluation visits Online monthly monitoring On-site annual monitoring On-site opening visits |

Local leadership On-site monitoring by national team On-line monitoring by international team Hybrid (online/on-site) opening visits (Fig. 4) |

| Establishing clinical centres and microbiology laboratories |

On-site displacement of external experts Hands-on training Staff internship in other national/international institutions Shared working platform and source of resources on the Cloud |

Local leadership Remote technical advice (hands-on training cancelled and internships postponed) Remote monitoring tools Increased of activities reporting and procedures documentation |

| Trainings |

Specialised training (GCP, GCLP, IPC) adapted by country according to previous knowledge and resources available (on-site/online/hybrid) On-site technical trainings On-site study initiation trainings |

Resorted to online trainings Large-scale webinars with local researchers on-site and external experts online |

COVID-19 Coronavirus disease 2019, GCP good clinical practice, GCLP good clinical laboratory practice, ICP infection prevention and control

Discussion: Lessons Learned and Tools for Sharing

Developing new strategies to tackle TBM and other emerging or re-emerging diseases, including COVID-19, requires clinical research [19–21]. The major global burden of communicable diseases is borne by SSA, but, in stark contrast, this region is only a minor beneficiary of clinical research funding [19, 21, 22]. Although highly competitive institutions have increased their presence in some countries in the region, many other countries lack such research capacity and are left behind; hence, resources remain centralised and significant disparities persist both between and within countries [20, 23]. In this context, clinical research combined with capacity building is an effective strategy to promote fairer resource distribution, to redress healthcare inequalities and to achieve minimum research capacity. These three features are crucial to the fight against endemic diseases and the prevention of future outbreaks [19–21, 23]. Moreover, research platforms developed for a given disease (e.g. TBM) may later serve in tackling others (e.g. COVID-19).

It is of concern that several African countries have documented a rise in infectious diseases during the COVID-19 pandemic [24–26]. A major factor driving this increase was the reallocation of existing resources from endemic diseases to COVID-19 and the overwhelming of healthcare systems [24–26]. In the field of TB and HIV, the WHO warns about the backward trend in the preventive and control programmes [1, 27]; similar concerns are raised with other infectious diseases that are emerging and re-emerging in SSA [28–30], with the prediction that the long-term consequences are still to come due to late diagnosis and treatment. Although infectious disease outbreaks have long posed a public health threat, especially in Africa, little attention has been given to strengthening the health surveillance systems [24, 28, 30, 31].

According to United Nations Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 17: “Partnerships for the Goals” [22, 32], humanity’s way forward requires strong global partnerships to enhance North–South and South-South cooperation, if we are to meet all other SDG targets, including SDG 3: “Good health and well-being” [22, 33]. This approach has been adopted by the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP), which promotes international consortia that are owned and co-led by European and African scientists. EDCTP aims to eliminate gaps in research by nurturing teams and synergetic networks that provide mutual assistance in promoting skills, experience, expertise and infrastructure, and that are collectively capable of conducting high-level clinical trials, even in complex settings [19, 34–36]. The INTENSE-TBM project is a good example of how the international consortium represents an opportunity to drive local capacity-building programmes, particularly by creating prosperous collaborations and attracting research funding.

Conducting capacity-building activities to create homogeneous, highly competitive and long-lasting consortia has always been a major challenge [37], but it has become even more complicated in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the INTENSE-TBM consortium had been mostly successful in overcoming the usual difficulties, the pandemic had serious consequences on the project’s research agenda, such as delays in initiation, and led us to consider innovative strategies to push forward the project despite the disruption of the national and international healthcare systems and our inability to travel on-site as expected.

In order to be sustainable, capacity building requires a long-term perspective, as it is expensive and time-consuming [19, 38]. With this in mind, we invested in developing capacity (infrastructure, equipment, resources, staff, networks) and capability (mentorship, skills, certified training, know-how), knowing that these will last beyond the lifespan of the project and enhance healthcare systems, ensure positive spill-overs to local institutions and attract further clinical research. In order to be effective, capacity-building interventions and support should be site specific, thereby reflecting the disparities in research capacity and experience among countries, regions and institutions [20, 21, 23, 37]. This approach optimises and equitably distributes resources where they are needed, and is inclusive when strengthening sites where clinical research has never been performed. Another key element of capacity-building programmes is professional development (e.g. mentorship, knowledge exchange, professional internships, training) [23, 39, 40]. Not only does professional development programmes improve clinical expertise and overall confidence in the study being conducted, but they also help to promote career advancement and to retain scientists. Despite the difficulties in procuring specialised training services (e.g.,GCP/GCLP, IPC) in some countries, we were able to demonstrate the feasibility of dispensing large-scale training in a hybrid format with local researchers on-site and external experts online.

The dissemination of reports on capacity-building programmes may provide useful practical guides for implementing clinical trials in other resource-limited settings and for raising the barriers perceived by donors and partners [20, 21]. In our case, some challenges were underestimated, potentially compromising the conduct of the trial at some sites; however, we were able to identify temporary solutions that kept the centers on track and that were in line with the goal of helping scale-up and decentralise national healthcare and clinical research.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced us to innovate and dematerialise many activities, causing us to reflect on the optimisation of resources. Remote activities (Table 1) were revealed to be feasible, largely cheaper, more sustainable and respectful of local and global environments; however, they required more paperwork and working hours to ensure good planning and to avoid overwhelming the staff on-site. In our case, even site initiation visits were successfully performed remotely (Fig. 4), with the sponsor and international managers guiding the visit online and the principal investigators and country managers conducting the visit on-site.

The ongoing COVID-19 crisis highlights the need for global health research, and national healthcare systems may indirectly benefit from capacity building related to clinical trials. In this regard, strengthening research capacity in LMIC may form the foundations for their self-reliance in the fight against endemic diseases and in coping with future health emergencies [19, 41, 42]. Many of platforms developed as part of INTENSE-TBM will continue to exist after the trial and may contribute to tackling new potential threats from infectious diseases.

In conclusion, the INTENSE-TBM project designed and developed a comprehensive capacity-building programme and has demonstrated its effectiveness by initiating the TBM-RCT at all planned sites, despite the COVID-19 pandemic. Capacity building develops infrastructure, provides resources, transfers knowledge, fosters capabilities and creates networks of skilled researchers—in the present case to ensure optimal conditions for conducting the TBM-RCT, to improve HIV/TB standards of care and to promote further clinical research in SSA. This is why capacity building must extend beyond the lifespan of individual projects and why this approach should be advocated for enhancing and decentralising healthcare services and clinical research.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Funding

INTENSE-TBM project is part of the EDCTP2 Programme supported by the European Union (Grant RIA2017T-2019) and is sponsored by Inserm–ANRS (ANRS 12398 INTENSE-TBM). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript. No funding or sponsorship was received for the publication of this article.

Medical Writing and Editorial Assistance

We thank Mr. Maxwell Crisp for language style and editing. Funding was obtained from the EDCTP2 Programme (Grant RIA2017T-2019).

Author Contributions

EA-V, FE, VM, AC, FB and JA have contributed to the conceptualisation, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation and data curation. EA-V and JA have contributed to the visualisation, formal analysis and original draft preparation. All authors have contributed to the funding acquisition, resources, investigation, manuscript review and editing.

List of Investigators

INTENSE-TBM list of investigators and study team members included as a Electronic Supplementary Material file.

Prior Presentation

Preliminary results of this work were presented as part of the Master’s degree of Eva Ariza-Vioque, Master of AIDS, University of Barcelona, Spain, under the supervision of Prof. Juan Ambrosioni and Prof. José M. Miró.

Disclosures

José-María Miró has received consulting honoraria and/or research grants from Angelini, Contrafect, Genentech, Gilead Sciences, Janssen, Lysovant, Medtronic, MSD, Pfizer and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work. Alexandra Calmy has received research and unrestricted educational grants, or both, from Gilead Sciences, MSD, BMS and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work. Juan Ambrosioni has participated in advisory boards and received consulting honoraria or research grants, or both, from Gilead Sciences, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and ViiV Healthcare, outside the submitted work. Eva Ariza-Vioque, Frédéric Ello, Holy Andriamamonjisoa, Vanessa Machault, Julià Gonzàlez-Martin, Maria-Camila Calvo-Cortes, Serge Eholié, Guie Annick Tchabert, Timothée Ouassa, Mihaja Raberahona, Rivonirina Rakotoarivelo, Haingo Razafindrakoto, Lalaina Rahajamanana, Robert J. Wilkinson, Angharad Davis, Mpumi Maxebengula, Fatima Abrahams, Conrad Muzoora, Noor Nakigozi, Dan Nyehangane, Deborah Nanjebe, Hassan Mbega, Rodney Kaitano, Maryline Bonnet, Pierre Debeaudrap, Xavier Anglaret, Niaina Rakotosamimanana and Fabrice Bonnet have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on authors knowledge and experiences prior to conducting clinical research and, therefore, it does not contain any data from human participants or animals. Written consent was obtained from the individuals appearing in Fig. 4.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A. Calmy, F. Bonnet and J. Ambrosioni contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2021. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240037021. Accessed 19 Feb 2022.

- 2.Wilkinson RJ, Rohlwink U, Misra UK, et al. Tuberculous meningitis. Nat Rev Neurol. 2017;13(10):581–598. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thwaites GE, van Toorn R, Schoeman J. Tuberculous meningitis: more questions, still too few answers. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(10):999–1010. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seddon JA, Tugume L, Solomons R, Prasad K, Bahr NC. The current global situation for tuberculous meningitis: epidemiology, diagnostics, treatment and outcomes. Wellcome Open Res. 2019;4(167):1–15. doi: 10.12688/wellcomeopenres.15535.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naidoo P, Theron G, Rangaka MX, et al. The South African tuberculosis care cascade: estimated losses and methodological challenges. J Infect Dis. 2017;216(suppl_7):S702–S713. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang MG, Luo L, Zhang Y, Liu X, Liu L, He JQ. Treatment outcomes of tuberculous meningitis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2019;19(1):200. doi: 10.1186/s12890-019-0966-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tenforde MW, Gertz AM, Lawrence DS, et al. Mortality from HIV-associated meningitis in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2020;23(1):e25416. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stop TB Partnership. Global plan to end TB: 2018–2022. 2019. http://www.stoptb.org/global/plan/plan1822.asp. Accessed 6 Oct 2021.

- 9.World Health Organization. Global strategy for tuberculosis research and innovation. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240010024. Accessed 6 Oct 2021.

- 10.World Health Organization. Implementing tuberculosis diagnostics. Policy framework. 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/162712/9789241508612_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 6 Oct 2021.

- 11.Global Laboratory Initiative-Stop TB Partnership. Mycobacteriology laboratory manual. 2014. https://www.who.int/tb/laboratory/mycobacteriology-laboratory-manual.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2021.

- 12.World Health Organization. Good clinical laboratory practice (GCLP). 2009. https://www.who.int/tdr/publications/documents/gclp-web.pdf. Accessed 6 Oct 2021.

- 13.World Health Organization. WHO consolidated guidelines on tuberculosis. Module 3: diagnosis—rapid diagnostics for tuberculosis detection, 2021 update. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240029415. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

- 14.Cresswell FV, Tugume L, Bahr NC, et al. Xpert MTB/RIF Ultra for the diagnosis of HIV-associated tuberculous meningitis: a prospective validation study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20(3):308–317. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30550-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization. Guidance for the surveillance of drug resistance in tuberculosis. 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240018020. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

- 16.World Health Organization. Handbook for good clinical research practice (GCP): guidance for implementation. 2005. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/43392/924159392X_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

- 17.World Health Organization. WHO guidelines on tuberculosis infection prevention and control, 2019 update. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311259/9789241550512-eng.pdf. Accessed 7 Oct 2021. [PubMed]

- 18.World Health Organization. Practical guidelines for infection control in health care facilities. 2004. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/206946/9290222387_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

- 19.Nyirenda T, Bockarie M, Machingaidze S, et al. Strengthening capacity for clinical research in sub-Saharan Africa: partnerships and networks. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;110:54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.06.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kilmarx PH, Maitin T, Adam T, et al. A mechanism for reviewing investments in health research capacity strengthening in low-and middle-income countries. Ann Glob Heal. 2020;86(1):92. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tupasi T, Gupta R, Danilovits M, et al. Building clinical trial capacity to develop a new treatment for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(2):147–152. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.154997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Addo-Atuah J, Senhaji-Tomza B, Ray D, Basu P, Loh FH, Owusu-Daaku F. Global health research partnerships in the context of the sustainable development goals (SDGs) Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2020;16(11):1614–1618. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morel T, Maher D, Nyirenda T, Olesen OF. Strengthening health research capacity in sub-Saharan Africa: mapping the 2012–2017 landscape of externally funded international postgraduate training at institutions in the region. Glob Health. 2018;14(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s12992-018-0395-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bassey EE, Hasan MM, Costa ACDS, et al. Typhoid fever and COVID-19 pandemic in Nigeria: a call for coordinated action. Einstein (Sao Paulo). 2021;19:eCE6796. doi: 10.31744/einstein_journal/2021CE6796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ismail Z, Aborode AT, Oyeyemi AA, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on viral hepatitis in Africa: challenges and way forward. Int J Health Plan Manag. 2022;37(1):547–552. doi: 10.1002/hpm.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uwishema O, Okereke M, Onyeaka H, et al. Threats and outbreaks of cholera in Africa amidst COVID-19 pandemic: a double burden on Africa’s health systems. Trop Med Health. 2021;49(1):93. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00376-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Global progress report on HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections, 2021. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240027077. Accessed 8 Jun 2022.

- 28.Khan FMA, Hasan MM, Kazmi Z, et al. Ebola and COVID-19 in Democratic Republic of Congo: grappling with two plagues at once. Trop Med Health. 2021;49(1):67. doi: 10.1186/s41182-021-00356-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohan A, Temitope RA, Çavdaroğlu S, et al. Measles returns to the Democratic Republic of Congo: a new predicament amid the COVID-19 crisis. J Med Virol. 2021;93(10):5691–5693. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okonji OC, Okonji EF, Mohanan P, et al. Marburg virus disease outbreak amidst COVID-19 in the Republic of Guinea: a point of contention for the fragile health system? Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2022;13:100920. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aborode AT, Hasan MM, Jain S, et al. Impact of poor disease surveillance system on COVID-19 response in Africa: time to rethink and rebuilt. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal. 2021;12:100841. doi: 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). SDG 17: partnerships for the goals. https://www1.undp.org/content/oslo-governance-centre/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-17-partnerships-for-the-goals.html. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

- 33.United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). SDG 3: Good health and well-being. https://www1.undp.org/content/oslo-governance-centre/en/home/sustainable-development-goals/goal-3-good-health-and-well-being.html. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

- 34.Zumla A, Makanga M, Nyirenda T, et al. Genesis of EDCTP2. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(1):11–13. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)71034-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zumla A, Petersen E, Nyirenda T, Chakaya J. Tackling the tuberculosis epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa—unique opportunities arising from the second European Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP) programme 2015–2024. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;32:46–49. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2014.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.European & Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP). Annual report 2020. 2021. http://www.edctp.org/web/app/uploads/2021/07/EDCTP-Annual-Report-2020-3.pdf. Accessed 7 Oct 2021.

- 37.Larkan F, Uduma O, Lawal SA, van Bavel B. Developing a framework for successful research partnerships in global health. Glob Health. 2016;12(1):17. doi: 10.1186/s12992-016-0152-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schluger N, Karunakara U, Lienhardt C, Nyirenda T, Chaisson R. Building clinical trials capacity for tuberculosis drugs in high-burden countries. PLoS Med. 2007;4(11):e302. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Whitworth JA, Kokwaro G, Kinyanjui S, et al. Strengthening capacity for health research in Africa. Lancet. 2008;372:1590–1593. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61660-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lang TA, White NJ, Hien TT, et al. Clinical research in resource-limited settings: enhancing research capacity and working together to make trials less complicated. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4(6):e619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Norton A, Sigfrid L, Aderoba A, et al. Preparing for a pandemic: highlighting themes for research funding and practice—perspectives from the Global Research Collaboration for Infectious Disease Preparedness (GloPID-R) BMC Med. 2020;18(1):273. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01755-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosenthal PJ, Breman JG, Djimde AA, et al. COVID-19: shining the light on Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102(6):1145–1148. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.