Abstract

In a time of societal acrimony, psychological scientists have turned to a possible antidote — intellectual humility. Interest in intellectual humility comes from diverse research areas, including researchers studying leadership and organizational behaviour, personality science, positive psychology, judgement and decision-making, education, culture, and intergroup and interpersonal relationships. In this Review, we synthesize empirical approaches to the study of intellectual humility. We critically examine diverse approaches to defining and measuring intellectual humility and identify the common element: a meta-cognitive ability to recognize the limitations of one’s beliefs and knowledge. After reviewing the validity of different measurement approaches, we highlight factors that influence intellectual humility, from relationship security to social coordination. Furthermore, we review empirical evidence concerning the benefits and drawbacks of intellectual humility for personal decision-making, interpersonal relationships, scientific enterprise and society writ large. We conclude by outlining initial attempts to boost intellectual humility, foreshadowing possible scalable interventions that can turn intellectual humility into a core interpersonal, institutional and cultural value.

Subject terms: Psychology, Social behaviour, Human behaviour

Intellectual humility involves acknowledging the limitations of one’s knowledge and that one’s beliefs might be incorrect. In this Review, Porter and colleagues synthesize concepts of intellectual humility across fields and describe the complex interplay between intellectual humility and related individual and societal factors.

Introduction

Intellectual humility involves recognizing that there are gaps in one’s knowledge and that one’s current beliefs might be incorrect. For instance, someone might think that it is raining, but acknowledge that they have not looked outside to check and that the sun might be shining. Research on intellectual humility offers an intriguing avenue to safeguard against human errors and biases. Although it cannot eliminate them entirely, recognizing the limitations of knowledge might help to buffer people from some of their more authoritarian, dogmatic, and biased proclivities.

Although acknowledging the limits of one’s insights might be easy in low-stakes situations, people are less likely to exhibit intellectual humility when the stakes are high. For instance, people are unlikely to act in an intellectually humble manner when motivated by strong convictions or when their political, religious or ethical values seem to be challenged1,2. Under such circumstances, many people hold tightly to existing beliefs and fail to appreciate and acknowledge the viewpoints of others3–6. These social phenomena have troubled scholars and policymakers for decades3. Consequently, interest in cultivating intellectual humility has come from multiple research areas and subfields in psychology, including social-personality, cognitive, clinical, educational, and leadership and organizational behaviour7–11. Cumulatively, research suggests that intellectual humility can decrease polarization, extremism and susceptibility to conspiracy beliefs, increase learning and discovery, and foster scientific credibility12–15.

The growing interdisciplinary interest in intellectual humility has led to multiple definitions and assessments, raising a question about commonality across definitions of the concept. Claims about its presumed societal and individual benefits further raise questions about the strength of evidence that supports these claims.

In this Review, we provide an overview of empirical intellectual humility research. We first examine approaches for defining and measuring intellectual humility across various subfields in psychology, synthesizing the common thread across seemingly disparate definitions. We next describe how individual, interpersonal and cultural factors can work for or against intellectual humility. We conclude by highlighting the importance of intellectual humility and detailing interventions to increase its prevalence.

Defining intellectual humility

Intellectual humility is conceptually distinct from general humility, modesty, perspective-taking and open-mindedness9. Whereas general humility involves how people think about their shortcomings and strengths across domains, intellectual humility is chiefly concerned with epistemic limitations16. In a similar vein, modesty emphasizes increased social awareness and not wanting to monopolize the spotlight or draw too much attention to one’s accomplishments, whereas intellectual humility focuses on recognizing one’s ignorance and intellectual fallibility17. General humility and modesty are also psychometrically distinct from intellectual humility18,19.

There are subtle differences between intellectual humility and perspective-taking. Perspective-taking is the ability to recognize and understand alternative points of view20. By contrast, intellectual humility is the ability to recognize shortcomings or potential limitations in one’s own point of view. Building on perspective-taking, open-mindedness refers to unbiased or fair consideration of different views regardless of one’s beliefs21. Although open-mindedness is theoretically and empirically related to intellectual humility, being open-minded does not always involve considering the limitations of one’s knowledge or beliefs22,23. Although it is distinct from these related phenomena, intellectual humility has multiple definitions, reflecting its use in different fields.

Intellectual humility has a wide range of philosophical roots24–27. Some philosophical accounts focus on attributes of people who frequently exhibit intellectually humble thoughts and behaviour (such as the tendency to recognize one’s fallibility and own one’s limitations)28. Most accounts define intellectual humility as a virtuous balance between intellectual arrogance (overvaluing one’s beliefs) and intellectual diffidence (undervaluing one’s beliefs)28–30. This definition has its roots in the Aristotelian ideal of the Golden Mean — a calibration of particular virtues to the demands of the situation at hand30,31. Because situations vary in their demands, a logical consequence of the Aristotelian approach is that intellectual humility is virtuous only as a dynamic, situation-sensitive construct30–32. Simultaneously, the Aristotelian approach means that the same psychological characteristics attributed to intellectual humility are unlikely to always be virtuous32.

Psychological scientists also define intellectual humility in a myriad of ways. Some scholars approach intellectual humility as a form of metacognition, reflecting how people regulate and reflect on their beliefs and thoughts. This view emphasizes the inherent limitations of human knowledge and beliefs, such as recognizing that beliefs might be wrong and that opinions are based on partial information9,29,33,34. Other scholars approach intellectual humility as a multidimensional phenomenon, advocating that intellectual humility includes a combination of metacognition, valuing other people’s beliefs, admitting one’s ignorance or errors to other people, and being motivated by an intrinsic desire to seek the truth35–37.

Scholars favouring broader accounts of intellectual humility argue that a strict focus on metacognition excludes appreciation for other people’s insights, behavioural responses when one recognizes that they might be wrong or confused, and motives for thinking and acting. In turn, scholars who endorse a metacognitive account of intellectual humility argue that encumbering intellectual humility with multiple features weakens the ability to examine it with conceptual clarity and methodological rigour. For example, multidimensional instruments might be difficult to interpret because a person high in one dimension and low in another could receive the same intellectual humility score as someone with the opposite psychological profile.

Preference for these competing accounts of intellectual humility varies across subfields of psychology, linked to methodological preferences and historical emphasis on social and contextual factors. Cognitive psychologists tend to favour metacognitive accounts that emphasize how people think about evidence, knowledge and beliefs, without much attention to social contexts13. Conversely, developmental, educational and clinical psychologists tend to favour a multidimensional account that considers how real world, cognitive, behavioural and interpersonal factors come together to form intellectual humility38–40. Social and personality psychologists, including those in the applied organizational sciences, consider metacognitive and multidimensional accounts9,33. Rather than endorsing a single definition, these researchers call for a clear distinction when measuring unique features of intellectual humility to reveal how the distinctive features relate to and shape one another41.

A cumulative science of intellectual humility benefits from clear definitions and explicit modelling of relationships between psychological processes and behavioural outcomes. Despite different conceptual approaches, most philosophers and psychologists agree that intellectual humility necessarily includes recognizing one’s ignorance and intellectual fallibility26. Hence, we focus on the metacognitive features of intellectual humility because they have consensus support from the scholarly community. Furthermore, these features are empirically plausible: they are scientifically testable and hence falsifiable. Taking a middle ground between metacognitive and multidimensional accounts, we argue that consideration of interpersonal contexts is beneficial for understanding how intellectual humility manifests, what factors inhibit and promote it, and how intellectual humility can be developed. At the same time, isolating the metacognitive core of intellectual humility permits scholars to identify its contextual and interpersonal correlates and reduces the likelihood of mistakenly labelling distinct processes and outcomes as intellectual humility (the jingle fallacy) or providing distinct names to the same family of metacognitive components of intellectual humility (the jangle fallacy)41. Thus, we define intellectual humility in terms of a metacognitive core composed of recognizing the limits of one’s knowledge and awareness of one’s fallibility (Fig. 1). This core is expressed by demonstrations of intellectual humility through behaviour and valuing the intellect of others.

Fig. 1. Conceptual representation of intellectual humility.

The core metacognitive components of intellectual humility (grey) include recognizing the limits of one’s knowledge and being aware of one’s fallibility. The peripheral social and behavioural features of intellectual humility (light blue) include recognizing that other people can hold legitimate beliefs different from one’s own and a willingness to reveal ignorance and confusion in order to learn. The boundaries of the core and peripheral region are permeable, indicating the mutual influence of metacognitive features of intellectual humility for social and behavioural aspects of the construct and vice versa.

Measuring intellectual humility

Psychological scientists have developed several measures of intellectual humility (Table 1). These measures can be organized in terms of the aspect of intellectual humility they target and the type of measure. In terms of aspect, some measures aim to capture intellectual humility as a trait — the degree to which people are intellectually humble in general — whereas others examine it as a state — the degree to which people are intellectually humble in specific contexts. In both cases, intellectual humility is measured along a continuum rather than as a binary measure.

Table 1.

Definitions and measures of intellectual humility

| Definition | Metacognitive emphasis | Approach | Aspect | Measure type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-dimensional trait of self-oriented and other-oriented facets, characteristic way of responding to new ideas, seeking out new information, being mindful of others’ feelings, and reactions in intellectual engagements135 | Limits of knowledge + fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | Trait | Questionnaire |

| Acknowledging the limitations of one’s knowledge; accurately representing one’s knowledge to other people and being open to others’ input38 | Limits of knowledge | Multidimensional | Trait | Behavioural task |

| Absence of self-enhancement motive and egotistical bias; ability to be objective with respect to one’s beliefs136 | Fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | Trait | Questionnaire |

| Placing an adequate level of confidence in one’s beliefs, revising beliefs when needed and being willing to consider other people’s beliefs35,37 | Limits of knowledge + fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | Trait and State | Questionnaire |

| Having an accurate view of one’s intellectual strengths and weaknesses and being respectful of others’ ideas101 | Limits of knowledge + fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | Trait | Questionnaire |

| The mindset and actions associated with treating one’s own views (such as beliefs, opinions and positions) as fallible137 | Fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | Trait | Questionnaire |

| Recognizing that a particular personal view or belief might be fallible, accompanied by an appropriate attentiveness to limitations in the evidentiary basis of that view or belief and to one’s own limitations in obtaining and evaluating information relevant to it33 | Fallibility awareness | Metacognitive | State | Questionnaire |

| Same as in ref.33 but using a trait rather than belief-specific approach9 | Fallibility awareness | Metacognitive | Trait | Questionnaire |

| The capacity to remain cognitively open to counterarguments, particularly when the counterargument poses some threat42 | Fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | State | Questionnaire |

| Recognizing the limits of one’s knowledge1,49,99 | Limits of knowledge | Metacognitive | State | Questionnaire, content analysis |

| A non-threatening awareness of one’s intellectual fallibility39,138 | Fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | Trait | Questionnaire |

| Having insights about the limits of one’s knowledge and regulating intellectual arrogance in relationships40 | Limits of knowledge | Multidimensional | Trait | Questionnaire |

| Low self-focus and little concern for status, caring most about the intrinsic value of knowledge and truth139 | Fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | Trait | Questionnaire |

| Willingness to recognize the limits of one’s knowledge and appreciate others’ intellectual strengths19 | Limits of knowledge | Multidimensional | Trait | Questionnaire |

| Openness to information that might conflict with one’s personal views and relatively weak needs to enhance one’s ego89 | Limits of knowledge + fallibility awareness | Multidimensional | State | Questionnaire |

Emerging research efforts measure intellectual humility using automated natural language processing techniques, which is promising to sidestep issues concerning self-report biases common to questionnaire measures140. Future work will be able to speak to the validity of this approach for measuring intellectual humility at scale.

One type of measurement is to ask participants to self-report on their intellectual humility in a questionnaire26. Questionnaires are used to assess trait and state (including belief-specific) intellectual humility. Another measurement type relies on behavioural tasks designed to elicit meaningful differences in a particular kind of response. For example, a researcher might ask people to play a game where the goal is to answer questions correctly and see how often participants delegate questions to more knowledgeable peers — an indication that people realize their own knowledge is incomplete (this task has been used to measure intellectual humility in children38). Both of these measurement types can contribute to estimates of trait and state intellectual humility.

Questionnaires

Questionnaires are often used to assess intellectual humility. A trait questionnaire might ask how much a person “[accepts] that [their] beliefs and attitudes may be wrong”9. A belief-specific questionnaire on the issue of gun control might ask how much a person “[recognizes] that [their] views about gun control are based on limited evidence”33. A state questionnaire might ask how intellectually humble a person feels in the moment or how much they “searched actively for reasons why [their] beliefs might be wrong” during a recent disagreement or conflict37. A closely related self-report measure asks people to indicate, for example, their attitude change or depth of understanding. These self-report tasks have been used as indirect measures of intellectual humility42.

Over the last decade, psychological scientists have developed many questionnaire measures of intellectual humility at the trait level26. The popularity of these measures is due to some level of predictive capacity and cost-effectiveness. People seem to be capable of reporting on their trait level of intellectual humility with some degree of accuracy, as supported by small-to-moderate positive correlations between self-reported intellectual humility and peer-reported intellectual humility9,11,19,43. Scores on self-reported trait-level intellectual humility (across different measures) are also positively associated with scores on self-report measures of other epistemic traits, such as intellect and open-mindedness, and to behaviours understood to be central to intellectual humility (including information-seeking, cognitive flexibility, acknowledgement of intellectual failings and argument evaluation)9,11,19,43,44.

Nevertheless, trait-level questionnaires of intellectual humility have limitations. All questionnaires rely on subjective judgements and are therefore vulnerable to response biases. Relevant biases include not accurately recalling one’s past experience, selecting positive responses on the measure by default, seeing oneself more positively than is warranted and focusing on favourable group comparisons when evaluating one’s behaviour. Thus, self-reports of one’s general intellectual humility provides numerous opportunities for error45,46.

Finally, it is difficult to assess socially desirable constructs with self-report measures. Scores obtained via trait-style measures of intellectual humility positively correlate with social desirability bias. In situations where intellectual humility is desirable, such as a job interview, self-report questionnaires make it easy to create a false impression of high intellectual humility47,48. Notably, response biases are attenuated when intellectual humility questionnaires ask people to report how intellectually humble they were in specific interpersonal situations in their lives, highlighting the value of more contextualized assessment of responses to specific situations (or states)49. In particular, reporting on how one searched for information or whether one recognized one’s fallibility during a specific event does not require as much mental effort because of access to specific memory cues, compared to reporting on how intellectually humble one is across many situations. In addition, when recalling a specific situation, a desire to present oneself in a positive light might be trumped by a stronger desire to provide an honest response about a particular event. Thus, questionnaires that ask about intellectual humility in specific situations or relevant to specific events might be less vulnerable to response bias than questionnaires that measure trait-level intellectual humility.

In sum, trait-level questionnaires might seem to be an efficient tool for obtaining an initial, general picture about one’s intellectual humility. However, these scores should be considered in light of their limitations. Although trait measures can be useful for describing typical ways of being in the world, they are not particularly good at detecting variability. Thus, they are not well suited to studying how intellectual humility might vary in daily life or change in response to an intervention. In response to these limitations, some researchers have examined intellectual humility in specific contexts or in response to specific issues. Scholars studying these questions have developed state-specific questionnaires about one’s beliefs, reasoning or behaviour that tap into intellectual humility about specific issues, such as gun control, vaccine mandates or more mundane interpersonal disagreements37,49,50. State measures enable researchers to capture how people’s intellectual humility varies as they move through various contexts and situations37,50,51.

Although individuals differ in their trait-level intellectual humility, they can also demonstrate a high degree of systematic variation depending on the demands of specific contexts. Capturing only global self-perceptions of intellectual humility with a trait measure glosses over this variability and nuance. By contrast, focus on state-specific measures echoes modern personality science, which defines a trait via a person’s profile of states52,53. A person’s profile — when aggregating across state-specific expressions of a characteristic — is typically stable over time. At the same time, state-specific expression of a characteristic will systematically vary across situations. Indeed, daily diary and experience-sampling studies demonstrate substantial within-person variability in intellectual humility37,50.

When researchers are interested in people’s overall patterns of intellectual humility across situations and variability from situation to situation, we recommend integrating state and trait approaches by taking repeated situation-specific assessments. We recommend reports of intellectual humility in the context of specific situations. Ideally, these assessments should be administered multiple times. We suggest using trait-level assessments of intellectual humility only for research focused on people’s global attributions of intellectual humility to themselves (self-reports) or close others (informant reports). A profile of intellectual humility can be further established by modelling responses across multiple situations.

If researchers are solely interested in participants’ general self-perceptions of intellectual humility, trait assessments might be suitable, with the caveats outlined above. Notably, little work has directly compared benefits of trait assessments of intellectual humility to repeated situation-specific assessments of intellectual humility, and further research on this topic is needed.

Behavioural tasks

A key advantage of behavioural tasks over other measures is that their scores do not typically depend on subjective judgements and therefore are not as prone to response biases and faking45,47,48. For example, measuring whether a person delegates a question to a more knowledgeable peer captures a real behaviour in the moment, in contrast to a self-report of a person’s impression of their behaviour in general or in a past situation. In addition, behavioural tasks depend less on language than questionnaires and might therefore be better for assessing intellectual humility in young children or in different cultural contexts. Behavioural tasks also put all participants in the same situation with the same opportunity to exhibit intellectual humility. By comparison, estimates of intellectual humility via questionnaires suffer from the confound of natural variability in the opportunity to be intellectually humble in daily life.

Nonetheless, custom-designed behavioural tasks can be less effective at measuring typical rather than extraordinary performance54. Experimental tasks capture only a small segment of behaviour in an artificial situation contrived by a researcher. A participant might be highly motivated to perform well on the task by displaying high levels of intellectual humility, rendering a score that captures their maximal capacity rather than their typical or externally valid intellectual humility. Behavioural measures also assume that the assessed behaviour is motivated by recognizing one’s ignorance and intellectual fallibility, which might not always be the case. Such behaviour might be motivated by situational pressures or other processes not characteristic of intellectual humility.

Behavioural tasks typically sample situation-specific responses, presenting a challenge for scholars interested in a general, trait-level picture of intellectual humility. It might be possible to administer behavioural tasks multiple times to obtain a more complete picture of someone’s typical behaviour. However, repeated exposure to the same task risks undermining score validity as participants become bored or more familiar with the task procedures.

Overall, behavioural tasks offer a useful measurement approach for assessing intellectual humility, complementing questionnaires. Nevertheless, the development and use of behavioural tasks has lagged behind questionnaires. No research has yet developed a valid intellectual humility behavioural task by performing psychometric testing of theoretically expected associations with other constructs and outcomes, in contrast to the many published studies doing so for questionnaires.

Threats to intellectual humility

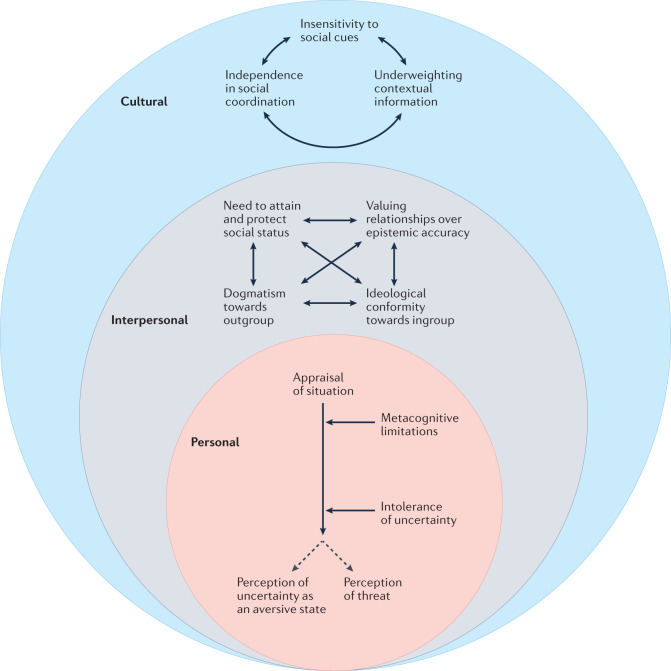

Being intellectually humble involves embracing uncertainty and ambiguity, and entertaining the possibility that even one’s closely held beliefs might be incorrect9. Thus, intellectual humility requires people to deliberately remain flexible in their beliefs11. However, many aspects of human psychology run counter to intellectual humility. We provide a non-exhaustive review of the personal, interpersonal and cultural factors that often work against intellectual humility (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Cultural, interpersonal and individual level threats to intellectual humility.

Threats include various metacognitive limitations, such as biased information search, overestimation of knowledge and failing to recognize unknowns, as well as situational factors. The nesting circles depict an individual (orange) contained within interpersonal (grey) and cultural (blue) spheres; threats apply across these levels. The arrows between the various threats depict the unidirectional (single-tipped) and mutual (double-tipped) influence each threat has on the other threats. The presence of one threat increases the likelihood that the other threats will emerge. Specific threats can further accentuate and interact with processes at other levels in a form of cross-level interaction.

Personal and interpersonal factors

When people try to reason through an issue, they often work hard to find evidence that confirms their initial perspective55–58. This process is often called confirmation or myside bias. Some theorists suggest that reasoning abilities have evolved to justify oneself and defend one’s reputations in front of others, so looking for confirmatory evidence to convince others of one’s good standing is a default strategy59,60. Because confirmatory search probably directs attention to arguments in support of one’s initial beliefs (rather than to the limits of one’s beliefs and their fallibility), this bias might act as a metacognitive limitation that runs counter to intellectual humility in many situations.

Even when a person desires to be intellectually humble, recognizing the limits of one’s knowledge requires overcoming metacognitive limitations that distort self-appraisal. For example, people tend to confidently overestimate how much they know about various phenomena — such as how a zip fastener works, how snow forms or how a helicopter takes flight — and become aware of their lack of knowledge only after failing to explain the phenomenon61–64. Moreover, people often fail to distinguish their knowledge from the knowledge of other people. Simply being aware that others understand how something works can result in people overestimating how much they understand the same phenomenon65. Thus, people struggle to recognize the limits of their knowledge and their fallibility — two core meta-cognitive features of intellectual humility.

Intellectual humility also involves accepting uncertainty about one’s beliefs. Although people differ in their tolerance of uncertainty and ambiguity, many find uncertainty disquieting or avoid it altogether in situations that are personally threatening66. To overcome the threat, people tend to become more self-focused and eager to cling to unambiguous, comforting beliefs, rather than seeking to understand more ambiguous truths34,67. Consequently, personal threats can lead to thinking in terms of extremes and absolutes (‘black and white’ thinking) and an unwillingness to recognize one’s limited perspective and potential fallibility68–71. For example, people who were made to feel highly threatened in an experiment became less comfortable considering opposing political opinions and were more wary of members of political outgroups compared to people who were made to feel only moderately threatened72. Feelings of personal threat might therefore interfere with the ability to exhibit intellectual humility.

Intellectual humility can also be hard to manifest and sustain when acknowledging the limitations of one’s beliefs would risk compromising interpersonal relationships. When members of cultural, religious, political or other social groups conform to the group’s ideology, they feel closer to one another73–76. Thus, people might reflexively adhere to their groups’ beliefs to strengthen relationships with other members of the group77–79. Group solidarity might therefore trump intellectual humility. For example, when embedded within ideologically homogeneous (versus varied) social networks, people become more resistant over time to changing their ideological beliefs — a tendency diametrically opposite to intellectual humility80,81. When a ‘group’s truth’ collides with reality, intellectual humility will be hard to come by.

The motive to attain status within one’s community might also work against intellectual humility82. Group members often gain prestige and rank by fervently endorsing the group’s ideology57,83–85. Espousing the group’s beliefs serves as a form of self-persuasion, further convincing people that the views they endorse must be correct, while moving further away from intellectual humility86–88.

However, fervently endorsing a group’s ideology does not mean that one is unlikely to show intellectual humility in general. People might endorse their group’s political dogmas while also being mindful of their intellectual limitations when arguing with individuals within the group. People become more intellectually humble during interpersonal conflicts when they feel connected to their group compared to situations when they feel disconnected42,89. This insight suggests that one might show little intellectual humility when endorsing group dogmas, while simultaneously displaying intellectual humility with close others (in the group). This situational dependency emphasizes the variability of intellectual humility as a construct.

Cultural factors

Cultural contexts shape how people think and process information90,91 and have the potential to influence whether they think in intellectually humble ways. For instance, people living in societies that emphasize interdependence in social coordination (such as Japan) tend to reflect on the mental states of others more, define the self through relationships with others, and are better able to avoid underweighting contextual information, relative to people living in more independent contexts (such as the USA)92,93. More generally, societies that emphasize interdependence rather than independence are more likely to promote relational goals, pay attention to social cues, define the self as embedded within one’s social environment and display social context vigilance92–95. Furthermore, people in communities that rely on interdependent social coordination for their food, such as fishing or rice farming, display more sensitivity to contextual information than people from communities that rely on individual-focused herding or wheat farming96,97.

Consideration of contextual information and mentalizing might be conducive to greater recognition of the limits of one’s knowledge and awareness of one’s fallibility. Indeed, there is some evidence for within-and between-country differences in intellectual humility. Within China, people from regions that rely on rice farming tend to display greater intellectual humility when reflecting on social conflicts compared to people from regions that rely on wheat farming98. In cross-cultural comparisons, individuals from countries that emphasize social coordination more, such as Japan or China, spontaneously show more intellectual humility in reflections on social conflicts compared to individuals in the USA and Canada99,100.

Overall, intellectual humility can be influenced by many factors, from personal cognitive habits to cultural contexts. Individuals are usually motivated to confirm their prior beliefs, to feel as though they know more than they actually do and to avoid opposing opinions when threatened. A desire to maintain interpersonal bonds can also tempt people to believe blindly in group ‘truths’. Simultaneously, people’s interpersonal and cultural contexts can make them more or less intellectually humble when dealing with others. Feeling accepted by one’s peers might promote intellectual humility during social conflicts. Finally, interdependent cultural contexts that require a high level of social coordination tend to promote ways of thinking that are sensitive to context and conducive to intellectual humility.

Importance of intellectual humility

The willingness to recognize the limits of one’s knowledge and fallibility can confer societal and individual benefits, if expressed in the right moment and to the proper extent. This insight echoes the philosophical roots of intellectual humility as a virtue30,31. State and trait intellectual humility have been associated with a range of cognitive, social and personality variables (Table 2). At the societal level, intellectual humility can promote societal cohesion by reducing group polarization and encouraging harmonious intergroup relationships. At the individual level, intellectual humility can have important consequences for wellbeing, decision-making and academic learning.

Table 2.

Correlates of intellectual humility

| Domain | Variable | Direction | Clarity of evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cognitive | Cognitive ability11,38,39,105 | Mixed | Unclear |

| Dogmatism9,35,140,141 | Negative | Clear | |

| Need for cognition9,18,19,39 | Positive | Clear | |

| Need for cognitive closure19,142 | Mixed | Unclear | |

| Open-minded thinking/intellectual openness/ curiosity2,9,11,19,35,39,43,49,117,118,138,139,143–145 | Positive | Clear | |

| Social | Empathic concern111,146 | Positive | Clear |

| Emotional diversity50,120 | Positive | Clear | |

| Forgiveness of others40,49,50,113 | Positive | Clear | |

| General humility18,19,138 | Positive | Clear | |

| Perspective-taking34,49,50,111,112,120,146 | Positive | Clear | |

| Political orientation9,19,22 | Unrelated | Somewhat clear | |

| Positive perception of person/disagreement22,37,42,102,103,105,113,138,147 | Positive | Clear | |

| Prosociality2,40,109,111 | Positive | Clear | |

| Seeking compromise49,50,112,120 | Positive | Clear | |

| Social desirability2,19,35,39,49,111,138 | Positive | Somewhat clear | |

| Personality | Agreeableness9,18,19,22,35,40,126,139,146 | Positive | Clear |

| Conscientiousness19,22,35,40 | Positive | Somewhat clear | |

| Extraversion22,35,49,139 | Positive | Somewhat clear | |

| Neuroticism35,40,49,139,148 | Negative | Clear | |

| Openness to experience9,18,19,22,35,40,43,49,105,138,139 | Positive | Clear |

Only variables with two or more papers examining them are included (39 papers in total are included). In the ‘Clarity of evidence’ column, ‘Clear’ signifies that the direction of the association of the variable is consistent across manuscripts, ‘Somewhat clear’ signifies that at least one manuscript reports a finding inconsistent with the other manuscripts and ‘Unclear’ signifies that there is no consistency in results reported across manuscripts.

Notably, empirical research has provided little evidence regarding the generalizability of the benefits or drawbacks of intellectual humility beyond the unique contexts of WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic) societies90. With this caveat, below is an initial set of findings concerning the implications of possessing high levels of intellectual humility. Unless otherwise specified, the evidence below concerns trait-level intellectual humility. After reviewing these benefits, we consider attempts to improve an individual’s intellectual humility and confer associated benefits.

Social implications

People who score higher in intellectual humility are more likely to display tolerance of opposing political and religious views, exhibit less hostility toward members of those opposing groups, and are more likely to resist derogating outgroup members as intellectually and morally bankrupt101–103. Although intellectually humbler people are capable of intergroup prejudice104, they are more willing to question themselves and to consider rival viewpoints104. Indeed, people with greater intellectual humility display less myside bias, expose themselves to opposing perspectives more often and show greater openness to befriending outgroup members on social media platforms19,22,102. By comparison, people with lower intellectual humility display features of cognitive rigidity and are more likely to hold inflexible opinions and beliefs9,11.

In addition to being associated with intergroup tolerance, intellectual humility is also associated with engaged cooperation with outgroup members. In both state and trait form, intellectually humbler people are more willing to let outgroup members speak freely and show greater interest in joining bipartisan groups aimed at discussing political issues34,105. Individuals showing greater state intellectual humility are also more cooperative after thinking through their position in a public goods game — in which they have to decide how much to contribute to a common pool that will be redistributed to all players — an effect that contrasts with the typical finding that deliberation leads to greater selfishness106,107. People showing higher intellectual humility are therefore less likely to demonize groups with opposing views and tend to be open to the possibility of engagement and cooperation.

Intellectual humility is also associated with intentions to forgive and reconcile with others who have hurt one or offended one’s beliefs40,108. Furthermore, intellectual humility might support interpersonal cohesion by reducing derogative behaviours during arguments, such as labelling opponents as malicious or unintelligent19,109. Closed-minded thinking can lead individuals to disparage others’ opinions or arguments110. Conversely, intellectual humility is associated with open-mindedness and a willingness to learn about differing perspectives, which might promote respectful debate19.

The willingness to acknowledge one’s intellectual limitations might also have important implications for interpersonal relationships. Intellectual humility is positively associated with multiple values, including empathy, gratitude, altruism, benevolence and universalism, which suggests that people with greater intellectual humility are more likely to value and care about the wellbeing of others111. Intellectual humility might also be instrumental in maintaining interpersonal relationships in the face of social adversity. For example, state intellectual humility is associated with higher positive affect and sense of closeness towards others following an interpersonal conflict112.

Overall, people reporting greater intellectual humility tend to be more open to opposing perspectives and more forgiving of others’ offences. However, because this empirical evidence is cross-sectional, it remains to be seen whether intellectual humility causes these social benefits.

Individual benefits

Intellectual humility might also have direct consequences for individuals’ wellbeing. People who reason about social conflicts in an intellectually humbler manner and consider others’ perspectives (components of wise reasoning) are more likely to report higher levels of life satisfaction and less negative affect compared to people who do not41. Leaders who are higher in intellectual humility are also higher in emotional intelligence and receive higher satisfaction ratings from their followers, which suggests that intellectual humility could benefit professional life113,114. Nonetheless, intellectual humility is not associated with personal wellbeing in all contexts: religious leaders who see their religious beliefs as fallible have lower wellbeing relative to leaders who are less intellectually humble in their beliefs115.

Intellectual humility might also help people to make well informed decisions. Intellectually humbler people are better able to differentiate between strong and weak arguments, even if those arguments go against their initial beliefs9. Intellectual humility might also protect against memory distortions. Intellectually humbler people are less likely to claim falsely that they have seen certain statements before116. Likewise, intellectually humbler people are more likely to scrutinize misinformation and are more likely to intend to receive the COVID-19 vaccine109,117.

Lastly, intellectual humility is positively associated with knowledge acquisition, learning and educational achievement. Intellectually humbler people are more motivated to learn and more knowledgeable about general facts39. Likewise, intellectually humbler high school and university students expend greater effort when learning difficult material, are more receptive to assignment feedback and earn higher grades14,118.

Despite evidence of individual benefits associated with intellectual humility, much of this work is correlational. Thus, associations could be the product of confounding factors such as agreeableness, intelligence or general virtuousness. Longitudinal or experimental studies are needed to address the question of whether and under what circumstances intellectual humility promotes individual benefits. Notably, philosophical theorizing about the situation-specific virtuousness of the construct suggests that high levels of intellectual humility are unlikely to benefit all people in all situations30,31.

Improving intellectual humility

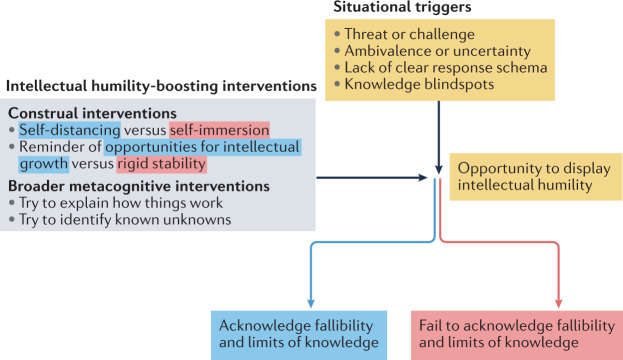

Given the apparent benefits of intellectual humility in various contexts, it might be desirable to increase one’s level of intellectual humility. Daily diary and experience-sampling studies, along with cross-cultural surveys, show that people’s level of intellectual humility systematically varies within and across individuals facing different ecological and situational demands, creating opportunities for intervention34,37,50,119. Initial evidence suggests several promising techniques for boosting intellectual humility (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Psychological strategies to boost intellectual humility.

Process model through which situational triggers (yellow) can produce either greater intellectual humility (blue) or intellectual arrogance (red). The left box (grey) depicts strategies that boost intellectual humility (blue) and strategies that hinder intellectual humility (red). Some construal-based and metacognitive interventions help to boost intellectual humility. Other strategies, such as self-immersion or rigid focus on stability, can result in failure to acknowledge one’s fallibility and the limits of knowledge.

Some experiments have documented short-term gains in intellectual humility following brief reflection, writing or reading exercises that are carefully designed to shift intellectual humility in the moment. Participants showed higher levels of intellectual humility after reflecting on experiences by taking a step back and envisioning themselves from the vantage point of a distant observer (self-distanced), rather than imagining themselves living out a particular situation (self-immersed)34. In other experiments, participants self-reported higher levels of intellectual humility after reflecting on real-life trust betrayal scenarios (involving disagreements or interpersonal conflicts) from a self-distanced rather than a self-immersed perspective1,120.

In a series of studies, people overestimated their self-reported knowledge of a policy less after writing a detailed explanation of how that policy works, thereby recognizing that their knowledge of the policy was less complete than they originally thought (overcoming the ‘illusion of understanding’)63,121,122. Likewise, people reported less confidence when answering a question if they first identified their ‘known unknowns’ by listing two things they did not know123. In another study, simply reading about the benefits of being intellectually humble, as opposed to being highly certain, also boosted self-reported intellectual humility118. Similarly, reading a short, persuasive article about intelligence being a malleable characteristic that can be developed, as compared to a fixed characteristic that is mostly genetically determined, increased self-reported state intellectual humility19. These studies collectively suggest that intellectual humility can be temporary boosted through simple, low-cost techniques.

Though promising, most of these experiments were run on small to medium-sized samples and have not been subject to replication. Two exceptions are the self-distancing effect, which has been replicated in several studies, and research on the illusion of understanding. In the latter domain, the original study showed that writing a detailed explanation of how a policy worked reduced both overestimation of knowledge and attitude extremity121. A close replication of the original study revealed that the manipulation reduced overestimation of knowledge but did not change people’s extreme attitudes124. In addition, the majority of studies reviewed above used self-report questionnaires to measure intellectual humility or other indicators of intellectual humility. Behavioural measures and larger, more representative samples would shed more light on the extent to which brief interventions can boost intellectual humility.

A few intervention studies have sought to measure the effects of intellectual humility training beyond a single session. In a randomized control trial, participants were assigned to a month-long diary activity that was either self-distanced or self-immersed125. Participants in the intervention group wrote daily reflections on important issues from a self-distanced perspective, and those in the comparison group did the same from a self-immersed perspective. Participants in the intervention group showed higher positive change in intellectual humility (coded from written narratives) between time points before and after the intervention125. Two further studies sought to increase intellectual humility through secondary and undergraduate philosophy courses. In one quasi-experimental study, a lesson on intellectual humility was either included at the beginning of a five-week undergraduate philosophy class or not. At the end of the course, students who received the lesson showed greater levels of compromise-seeking in conflicts and were perceived by their peers as having higher intellectual humility than those in a control group. However, the lesson did not increase self-reported intellectual humility126. Likewise, high school and middle school student participants in a week-long philosophy summer camp for at least three years self-reported somewhat higher intellectual humility relative to a control group of students who attended only one or two week-long sessions of the camp, although this difference was not statistically significant127. Critically, neither of the latter two interventions used a randomized design, so selection bias — in which one comparison group systematically differs from the other on a variable other than receiving the intervention — might be responsible for the effects. Overall, research supports the use of self-distanced diary writing to increase intellectual humility. By contrast, evidence remains limited and inconclusive on whether intellectual humility can be increased through classroom instruction.

Summary and future directions

Recognizing one’s ignorance and intellectual fallibility are core features of intellectual humility. Intellectually humbler people seem to be more curious and better liked as leaders, and tend to make more thorough, well informed decisions. Intellectually humbler people also seem to be more open to cooperating with those whose views differ from their own. These habits of mind could be vital for confronting many of the challenges facing societies today, and beneficial to laypeople, policy makers and scientists (Box 1).

Despite the wealth of current insights on intellectual humility, a range of critical themes remain unexplored. One challenge is to understand when exactly intellectual humility becomes too much of a good thing. Arguably, contexts calling for judgement by a certain deadline and/or based on a pre-defined set of existing facts (such as in a legal court, war room or executive business meeting) can benefit from intellectual humility only when permitted by time and the due process of law. In moments that require decisive action, focusing on one’s fallibility and limits of knowledge might not be the best strategy. Intuitions about the bounded utility of intellectual humility are corroborated by qualitative interviews with military personnel and business employees128. Moreover, situational contexts in which intellectual humility helps or does not help remain unexplored. Research identifying when and for whom intellectual humility becomes disadvantageous would help to address this gap.

Most research on intellectual humility has considered humility to be characterized by a relatively stable way in which a particular person behaves across situations32. More work is required to understand how intellectual humility varies within a particular person in different situations and domains and how organizations and cultures differ in intellectual humility. Future work will need to explore the causal links between a culture’s emphasis on interdependence in social coordination and intellectual humility. Studies that measure intellectual humility across multiple domains and in multiple societies99 will also lead to a better understanding of how cultural social coordination might shape intellectual humility in different domains. For example, large threats such as war, natural disasters or pandemics might increase the need for interdependence in social coordination, creating a culture that encourages people to be intellectually humble during social conflict with close friends and family. In turn, this intellectual humility might increase the capacity for social coordination at the expense of intellectual humility with strangers or those who question ideological orthodoxies, to safeguard social coordination from further threat99.

Interventions offer another avenue for future research. It remains to be seen whether interventions to boost intellectual humility can meaningfully address difficult societal problems such as polarization, misinformation and conspiracy beliefs. Perhaps helping individuals become more aware of their intellectual fallibility could address such problems. Intellectual humility interventions might also need to incorporate social-contextual elements, such as changing organizational cultures, to produce meaningful improvements. Future intervention studies should also test whether and how long effects endure and to identify optimal interventions to induce long-lasting change in intellectual humility129.

Future research should also explore the role of larger cultural forces, such as media landscapes and public communication, in promoting or reducing intellectual humility. Public figures are often denigrated in the media for changing their minds or admitting mistakes130. News media also typically avoid reporting areas of uncertainty or ambiguity in favour of definitive stories, even though communicating uncertainty can promote trust in science131–133 (though see ref.134). Individuals might be able to embrace intellectual humility only to the extent that institutions validate and support it. Thus, interventions that normalize intellectual humility in public communication should be studied to determine their potential impact on both individuals and societies.

In the spirit of intellectual humility, we conclude by pointing out that intellectual humility is not a panacea. Although it promises to counter societal incivility and misinformation, intellectual humility is cognitively effortful and is insufficient for addressing many other societal challenges. Moreover, a systemic approach is needed to foster intellectual humility at scale. Such an approach could involve a range of incremental changes that afford each person greater recognition of the limits of their knowledge and awareness of their fallibility. This approach to fostering intellectual humility calls for societal change in educational, scientific and business cultures: away from treating intellectual humility as a weakness and towards treating it as a core value that is celebrated and reinforced. Individual-focused interventions to boost intellectual humility are not likely to be effective in the long term without corresponding societal changes.

Box 1 Intellectual humility in science.

The scientific enterprise is inherently imbued with uncertainty: when new data emerge, older ideas and models ought to be revised to accommodate the new findings. Thus, intellectual humility might be particularly important for scientists for its role in enabling scientific progress. Acknowledging the fallibility of scientific results via replication studies can help scientists to revise their beliefs about evidence for particular scientific phenomena149. Furthermore, scientific claims are typically probabilistic, and communication of the full finding requires communication of the uncertainty intervals around estimates. For example, within psychology, most phenomena are multidetermined and complex. Moreover, most new psychological findings are provisional, with a gap between laboratory observation and application in real-world contexts. Finally, most findings in psychological sciences focus on explaining the past, and are not always well equipped for predicting reactions to critical social issues150. Critically, prediction is by definition more uncertain than (post-hoc) explanation, yet in most instances it is also of greater practical value. Focusing on predictions to test our understanding of causal models in sciences can be a powerful way to foster intellectual humility. In turn, emphasizing the general value of intellectual humility can help scientists to commit to predictions, even if such predictions turn out to be wrong.

Because of uncertainty around individual scientific findings, communication of scientific insights to policy makers, journalists and the public requires scientists to be intellectually humble15. Despite worry by some scientists that communicating uncertainty would lower public trust in science151,152, there is little conclusive evidence to support this claim153. Whereas communicating consensus uncertainty — that is, uncertainty in expert opinions on an issue — can have negative effects on trust, communicating technical uncertainty in estimates or models via confidence intervals or similar techniques has either positive or null effects for perception of scientific credibility154. At the same time, members of the public who show greater intellectual humility are better able to separate scientific facts from misinformed fictions.

Although intellectual humility is fundamental for science, scientists often shy away from reporting complex data patterns, preferring (often unrealistically) clear, ‘groundbreaking’ results15. Recognition of the limits of knowledge and of theoretical models can be beneficial for increasing credibility within the scientific community. Embracing intellectual humility in science via transparent and systematic reporting on limitations of scientific models and constraints on generality has the potential to improve the scientific enterprise155. Within science, intellectual humility could help to reduce the file-drawer problem (the publication bias toward statistically significant or otherwise desirable results) — calibrate scientific claims to the relevant evidence, buffer against exaggeration, prevent motivated cognition and selective reporting of results that affirm one’s hypotheses, and increase the tendency to welcome scholarly critique.

Acknowledgements

The present research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (doctoral scholarship 767-2020-2395 to A.E. and Insight grant 435-2014-0685 to I.G.), by a postgraduate scholarship-doctoral grant PGSD3-547482-2020 from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (to E.A.M.), by an Early Researcher award ER16-12-169 from the Ontario Ministry of Research and Innovation (to I.G.), by the John Templeton Foundation (grant 61942 to T.P., grant 61514 to E.J. and grant 62260 to I.G.) and by the Templeton World Charity Foundation (grant TWCF0355 to E.J. and I.G.).

Author contributions

I.G. conceived the idea for the Review. The authors contributed equally to the conceptual development of the article. T.P., A.E., T.S. and I.G. wrote the first draft. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Psychology thanks Mark Alfano, Cory Clark and Alexa Tullett for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Grossmann I, Kross E. Exploring Solomon’s paradox: self-distancing eliminates the self-other asymmetry in wise reasoning about close relationships in younger and older adults. Psychol. Sci. 2014;25:1571–1580. doi: 10.1177/0956797614535400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krumrei-Mancuso EJ, Newman B. Intellectual humility in the sociopolitical domain. Self Ident. 2020;19:989–1016. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2020.1714711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rokeach, M. The Open and Closed Mind (Basic Books, 1960).

- 4.Finkel EJ, et al. Political sectarianism in America. Science. 2020;370:533–536. doi: 10.1126/science.abe1715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jervis, R. Perception and Misperception in International Politics (Princeton Univ. Press, 2017).

- 6.Tetlock, P. E. Expert Political Judgment (Princeton Univ. Press, 2005).

- 7.Higgins M. The Judgment in Re W (A child): national and international implications for contemporary child and family social work. Br. J. Soc. Work. 2019;49:44–58. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bcy018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapsley D, Chaloner D. Post-truth and science identity: a virtue-based approach to science education. Educ. Psychol. 2020;55:132–143. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2020.1778480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leary MR, et al. Cognitive and interpersonal features of intellectual humility. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2017;43:793–813. doi: 10.1177/0146167217697695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Minson JA, Chen FS, Tinsley CH. Why won’t you listen to me? Measuring receptiveness to opposing views. Manag. Sci. 2020;66:3069–3094. doi: 10.1287/mnsc.2019.3362. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zmigrod L, Zmigrod S, Rentfrow PJ, Robbins TW. The psychological roots of intellectual humility: the role of intelligence and cognitive flexibility. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2019;141:200–208. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2019.01.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowes SM, Costello TH, Ma W, Lilienfeld SO. Looking under the tinfoil hat: clarifying the personological and psychopathological correlates of conspiracy beliefs. J. Pers. 2021;89:422–436. doi: 10.1111/jopy.12588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mellers B, Tetlock P, Arkes HR. Forecasting tournaments, epistemic humility and attitude depolarization. Cognition. 2019;188:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2018.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong IHM, Wong TTY. Exploring the relationship between intellectual humility and academic performance among post-secondary students: the mediating roles of learning motivation and receptivity to feedback. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2021;88:102012. doi: 10.1016/j.lindif.2021.102012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoekstra R, Vazire S. Aspiring to greater intellectual humility in science. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2021 doi: 10.1038/s41562-021-01203-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Banker CC, Leary MR. Hypo-egoic nonentitlement as a feature of humility. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2020;46:738–753. doi: 10.1177/0146167219875144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Park N, Peterson C, Seligman MEP. Strengths of character and well-being. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2004;23:603–619. doi: 10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davis DE, et al. Distinguishing intellectual humility and general humility. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016;11:215–224. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2015.1048818. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Porter T, Schumann K. Intellectual humility and openness to the opposing view. Self Ident. 2018;17:139–162. doi: 10.1080/15298868.2017.1361861. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flavell, J. H. in Piaget’s Theory: Prospects and Possibilities (eds Beilin, H. & Pufall, P. B.) 107–139 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992).

- 21.Baehr J. The structure of open-mindedness. Can. J. Phil. 2011;41:191–213. doi: 10.1353/cjp.2011.0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowes SM, et al. Stepping outside the echo chamber: is intellectual humility associated with less political myside bias? Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2022;48:150–164. doi: 10.1177/0146167221997619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spiegel JS. Open-mindedness and intellectual humility. Theory Res. Educ. 2012;10:27–38. doi: 10.1177/1477878512437472. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballantyne N. Recent work on intellectual humility: a philosopher’s perspective. J. Posit. Psychol. 2021 doi: 10.1080/17439760.2021.1940252. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King, N. L. The Excellent Mind: Intellectual Virtues for Everyday Life (Oxford Univ. Press, 2021).

- 26.Porter T, et al. Clarifying the content of intellectual humility: a systematic review and integrative framework. J. Pers. Assess. 2021;27:1–13. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2021.1975725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snow, N. E. in The Routledge Handbook of Virtue Epistemology (Routledge, 2018).

- 28.Whitcomb D, Battaly H, Baehr J, Howard-Snyder D. Intellectual humility: owning our limitations. Phil. Phenomenol. Res. 2017;94:509–539. doi: 10.1111/phpr.12228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Church, I. M. & Barrett, J. L. in Handbook of Humility 62–75 (Routledge, 2016).

- 30.Ng V, Tay L. Lost in translation: the construct representation of character virtues. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020;15:309–326. doi: 10.1177/1745691619886014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grossmann I, Dorfman A, Oakes H. Wisdom is a social-ecological rather than person-centric phenomenon. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2020;32:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grant AM, Schwartz B. Too much of a good thing: the challenge and opportunity of the inverted U. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2011;6:61–76. doi: 10.1177/1745691610393523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoyle RH, Davisson EK, Diebels KJ, Leary MR. Holding specific views with humility: conceptualization and measurement of specific intellectual humility. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2016;97:165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.043. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kross E, Grossmann I. Boosting wisdom: distance from the self enhances wise reasoning, attitudes, and behavior. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2012;141:43. doi: 10.1037/a0024158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haggard M, et al. Finding middle ground between intellectual arrogance and intellectual servility: development and assessment of the limitations-owning intellectual humility scale. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2018;124:184–193. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Priest M. Intellectual humility: an interpersonal theory. Ergo. 2017 doi: 10.3998/ergo.12405314.0004.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zachry CE, Phan LV, Blackie LE, Jayawickreme E. Situation-based contingencies underlying wisdom-content manifestations: examining intellectual humility in daily life. J. Gerontol. Ser. B. 2018;73:1404–1415. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gby016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Danovitch JH, Fisher M, Schroder H, Hambrick DZ, Moser J. Intelligence and neurophysiological markers of error monitoring relate to children’s intellectual humility. Child Dev. 2019;90:924–939. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krumrei-Mancuso EJ, Haggard MC, LaBouff JP, Rowatt WC. Links between intellectual humility and acquiring knowledge. J. Posit. Psychol. 2020;15:155–170. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1579359. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McElroy SE, et al. Intellectual humility: scale development and theoretical elaborations in the context of religious leadership. J. Psychol. Theol. 2014;42:19–30. doi: 10.1177/009164711404200103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Grossmann I, et al. The science of wisdom in a polarized world: knowns and unknowns. Psychol. Inq. 2020;31:103–133. doi: 10.1080/1047840X.2020.1750917. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jarvinen MJ, Paulus TB. Attachment and cognitive openness: emotional underpinnings of intellectual humility. J. Posit. Psychol. 2017;12:74–86. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2016.1167944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Meagher BR, Leman JC, Heidenga CA, Ringquist MR, Rowatt WC. Intellectual humility in conversation: distinct behavioral indicators of self and peer ratings. J. Posit. Psychol. 2021;16:417–429. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2020.1738536. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ludwig JM, Schumann K, Porter T. Humble and apologetic? Predicting apology quality with intellectual and general humility. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2022;188:111477. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2021.111477. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abrahams L, et al. Social-emotional skill assessment in children and adolescents: advances and challenges in personality, clinical, and educational contexts. Psychol. Assess. 2019;31:460–473. doi: 10.1037/pas0000591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duckworth AL, Yeager DS. Measurement matters: assessing personal qualities other than cognitive ability for educational purposes. Educ. Res. 2015;44:237–251. doi: 10.3102/0013189X15584327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arendasy M, Sommer M, Herle M, Schützhofer B, Inwanschitz D. Modeling effects of faking on an objective personality test. J. Individ. Differ. 2011;32:210–218. doi: 10.1027/1614-0001/a000053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ziegler M, Schmidt-Atzert L, Buhner M, Krumm S. Fakability of different measurement methods for achievement motivation: questionnaire, semi-projective, and objective. Psychol. Sci. 2007;49:291–307. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brienza JP, Kung FYH, Santos HC, Bobocel DR, Grossmann I. Wisdom, bias, and balance: toward a process-sensitive measurement of wisdom-related cognition. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2018;115:1093–1126. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grossmann I, Gerlach TM, Denissen JJA. Wise reasoning in the face of everyday life challenges. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2016;7:611–622. doi: 10.1177/1948550616652206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grossmann I. Wisdom in context. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2017;12:233–257. doi: 10.1177/1745691616672066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fleeson, W. & Jayawickreme, E. in Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (ed. Gawronski, B.) Vol. 63, 69–128 (Elsevier, 2015).

- 53.Mischel W, Shoda Y. A cognitive-affective system theory of personality: reconceptualizing situations, dispositions, dynamics, and invariance in personality structure. Psychol. Rev. 1995;102:246–268. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Enkavi AZ, et al. Large-scale analysis of test–retest reliabilities of self-regulation measures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:5472–5477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1818430116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koriat A, Lichtenstein S, Fischhoff B. Reasons for confidence. J. Exp. Psychol. 1980;6:107–118. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kuhn D, Weinstock M, Flaton R. How well do jurors reason? Competence dimensions of individual variation in a juror reasoning task. Psychol. Sci. 1994;5:289–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1994.tb00628.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kahan, D. M. Ideology, motivated reasoning, and cognitive reflection: an experimental study. Judgm. Decis. Mak.8, 407–424 10.2139/ssrn.2182588 (2013).

- 58.Kunda Z. The case for motivated reasoning. Psychol. Bull. 1990;108:480–498. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mercier H. The argumentative theory: predictions and empirical evidence. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2016;20:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2016.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mercier H, Sperber D. Why do humans reason? Arguments for an argumentative theory. Behav. Brain Sci. 2011;34:57–74. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X10000968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rozenblit L, Keil F. The misunderstood limits of folk science: an illusion of explanatory depth. Cogn. Sci. 2002;26:521–562. doi: 10.1207/s15516709cog2605_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moore DA, Healy PJ. The trouble with overconfidence. Psychol. Rev. 2008;115:502–517. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Meyers EA, Turpin MH, Bialek M, Fugelsant J, Kohler DJ. Inducing feelings of ignorance makes people more receptive to expert (economist) opinion. Judgm. Decis. Mak. 2020;15:909–925. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vitriol JA, Marsh JK. The illusion of explanatory depth and endorsement of conspiracy beliefs. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018;48:955–969. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sloman SA, Rabb N. Your understanding is my understanding: evidence for a community of knowledge. Psychol. Sci. 2016;27:1451–1460. doi: 10.1177/0956797616662271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Grupe DW, Nitschke JB. Uncertainty and anticipation in anxiety: an integrated neurobiological and psychological perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2013;14:488–501. doi: 10.1038/nrn3524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bogdanov M, Nitschke JP, LoParco S, Bartz JA, Otto AR. Acute psychosocial stress increases cognitive-effort avoidance. Psychol. Sci. 2021;32:1463–1475. doi: 10.1177/09567976211005465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Czernatowicz-Kukuczka A, Jaśko K, Kossowska M. Need for closure and dealing with uncertainty in decision making context: the role of the behavioral inhibition system and working memory capacity. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2014;70:126–130. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2014.06.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Jonas, E. et al. in Advances In Experimental Social Psychology Vol. 49 (eds Olson, J. M. & Zanna, M. P.) 219–286 (Academic, 2014).

- 70.Kruglanski AW, et al. The energetics of motivated cognition: a force-field analysis. Psychol. Rev. 2012;119:1–20. doi: 10.1037/a0025488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Webber D, et al. The road to extremism: field and experimental evidence that significance loss-induced need for closure fosters radicalization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2018;114:270–285. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thórisdóttir H, Jost JT. Motivated closed-mindedness mediates the effect of threat on political conservatism. Polit. Psychol. 2011;32:785–811. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9221.2011.00840.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Launay J, Dunbar RIM. Playing with strangers: which shared traits attract us most to new people? PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0129688. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Levitan LC, Verhulst B. Conformity in groups: the effects of others’ views on expressed attitudes and attitude change. Polit. Behav. 2016;38:277–315. doi: 10.1007/s11109-015-9312-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mallinson DJ, Hatemi PK. The effects of information and social conformity on opinion change. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0196600. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Van Bavel JJ, Pereira A. The partisan brain: an identity-based model of political belief. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2018;22:213–224. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Carlson TN, Settle JE. Political chameleons: an exploration of conformity in political discussions. Polit. Behav. 2016;38:817–859. doi: 10.1007/s11109-016-9335-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cheadle JE, Schwadel P. The ‘friendship dynamics of religion,’ or the ‘religious dynamics of friendship’? A social network analysis of adolescents who attend small schools. Soc. Sci. Res. 2012;41:1198–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Garrett RK, Sude D, Riva P. Toeing the party lie: ostracism promotes endorsement of partisan election falsehoods. Polit. Commun. 2020;37:157–172. doi: 10.1080/10584609.2019.1666943. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Levitan LC, Visser PS. The impact of the social context on resistance to persuasion: effortful versus effortless responses to counter-attitudinal information. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2008;44:640–649. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2007.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Visser PS, Mirabile RR. Attitudes in the social context: the impact of social network composition on individual-level attitude strength. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004;87:779–795. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Anderson C, Hildreth JAD, Howland L. Is the desire for status a fundamental human motive? A review of the empirical literature. Psychol. Bull. 2015;141:574–601. doi: 10.1037/a0038781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Anderson C, Brion S, Moore DA, Kennedy JA. A status-enhancement account of overconfidence. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2012;103:718–735. doi: 10.1037/a0029395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Connors EC. The social dimension of political values. Polit. Behav. 2020;42:961–982. doi: 10.1007/s11109-019-09530-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Drummond C, Fischhoff B. Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2017;114:9587–9592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1704882114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schwardmann P, Van der Weele J. Deception and self-deception. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2019;3:1055–1061. doi: 10.1038/s41562-019-0666-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Smith MK, Trivers R, von Hippel W. Self-deception facilitates interpersonal persuasion. J. Econ. Psychol. 2017;63:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.joep.2017.02.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Solda A, Ke C, Page L, Von Hippel W. Strategically delusional. Exp. Econ. 2020;23:604–631. doi: 10.1007/s10683-019-09636-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Reis HT, Lee KY, O’Keefe SD, Clark MS. Perceived partner responsiveness promotes intellectual humility. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2018;79:21–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2018.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature. 2010;466:29. doi: 10.1038/466029a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nisbett, R. E. & Norenzayan, A. in Steven’s Handbook of Experimental Psychology: Memory and Cognitive Processes 3rd edn (eds. Pashler, H. & Medin, D.) Vol. 2, 561–597 (Wiley, 2002).

- 92.Markus HR, Kitayama S. Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychol. Rev. 1991;98:224. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Varnum MEW, Grossmann I, Kitayama S, Nisbett RE. The origin of cultural differences in cognition: the social orientation hypothesis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2010;19:9–13. doi: 10.1177/0963721409359301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Cross SE, Bacon PL, Morris ML. The relational-interdependent self-construal and relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2000;78:791–808. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Schwartz S. A theory of cultural value orientations: explication and applications. Comp. Sociol. 2006;5:137–182. doi: 10.1163/156913306778667357. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Talhelm T, et al. Large-scale psychological differences within China explained by rice versus wheat agriculture. Science. 2014;344:603–608. doi: 10.1126/science.1246850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Uskul AK, Kitayama S, Nisbett RE. Ecocultural basis of cognition: farmers and fishermen are more holistic than herders. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:8552–8556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803874105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wei X-D, Wang F-Y. Southerners are wiser than northerners regarding interpersonal conflicts in China. Front. Psychol. 2020;11:225. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Grossmann I, et al. Aging and wisdom: culture matters. Psychol. Sci. 2012;23:1059–1066. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wei X, Wang F. The influence of culture on wise reasoning in the context of self-friend conflict and its mechanism. Acta Psychol. Sin. 2021;53:1244. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2021.01244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]