Abstract

Summary

All-cause mortality risk persisted for 5 years after hip fractures in both men and women. There may be gender-specific differences in effect and duration of excess risk for cause-specific mortality after hip fracture.

Introduction

To determine all-cause and cause-specific mortality risk in the first 5 years after hip fracture in an Asian Chinese population.

Methods

The Singapore Chinese Health Study is a population-based cohort of 63,257 middle-aged and elderly Chinese men and women in Singapore recruited between 1993 and 1998. This cohort was followed up for hip fracture and death via linkage with nationwide hospital discharge database and death registry. As of 31 December 2008, we identified 1,166 hip fracture cases and matched five non-fracture cohort subjects by age and gender for each fracture case. Cox proportional hazards and competing risks regression models with hip fracture as a time-dependent covariate were used to determine all-cause and cause-specific mortality risk, respectively.

Results

Increase in all-cause mortality risk persisted till 5 years after hip fracture (adjusted hazard ratio, aHR = 1.58 [95 % CI, 1.35–1.86] for females and aHR = 1.64 [95 % CI, 1.30–2.06] for males). Men had higher mortality risk after hip fracture than women for deaths from stroke and cancer up to 1 year post-fracture but women with hip fracture had higher coronary artery mortality risk than men for 5 years post-fracture. Men had higher risk of death from pneumonia while women had increased risk of death from urinary tract infections. There was no difference in mortality risk by types of hip fracture surgery.

Conclusions

All-cause mortality risk persisted for 5 years after hip fractures in men and women. There are gender-specific differences in effect size and duration of excess mortality risk from hip fractures between specific causes of death.

Keywords: All-cause mortality, Cause-specific mortality, Chinese, Hip fracture, Men, Women

Introduction

Osteoporotic fractures are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality, accounting for 0.83 % of the global burden of non-communicable disease [1]. While the greatest proportion of osteoporotic fractures occurs in Europe (36.6 %), 15.5 % arise from Southeast Asia, and this is close to the estimated prevalence in the North and South America (16.0 %). Although hip fracture account for only 18.2 % of all osteoporotic fractures worldwide, its severe consequences incur a disproportionately larger burden of disability-adjusted life years lost (40 %) as compared to fracture at other sites because of its greater effects on disability and mortality [1].

An international comparison of mortality after hip fracture based on a review of all articles published from 1959 to 1998 (40 years) by Haleem et al. [2] found geographical variations, with 6-month mortality rates of at least 20 % for Scandinavia (20 %), UK (28 %) and Europe (22 %). The mortality rate for North America was 17 % and unusually low at 10 % for Asia. Unfortunately, only three studies from Asia (two from Japan and one from Singapore) contributed to this rate, and they only studied mortality up to 1 year [3–5]. A recent meta-analysis by Haentjens et al. [6] included only studies which examined mortality beyond 1 year after hip fracture and found geographical differences in all-cause mortality rates with the lowest rates in Southeast Asia. Only one paper from Asia (Thailand) was included in that meta-analysis and it was limited to only females [7], reflecting the dearth of post hip fracture mortality data from this region. There is thus a need for more detailed information to determine if these geographical differences in outcome are due to variations in clinico-demographic profiles or differences in treatment methods. To our best knowledge, there has been no Asian study which has examined mortality after hip fractures beyond 2 years post-fracture. Furthermore, there is little data on cause-specific mortality rates after hip fracture and existing studies have been variably or poorly reported so far. Patients with hip fracture may undergo one of two different types of hip fracture surgery, hemiarthroplasty versus open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF). There is a possible increase in risk of mortality that may be attributed to greater immobility with ORIF compared with hemiarthroplasty since patients treated with the former are generally non-weight bearing for 4–6 weeks while those treated with the latter can bear weight immediately after surgery. Difference in mortality rates between types of hip fracture surgery has never been studied in Asian populations.

In this study, we compared the mortality risks between 1,166 participants with incident hip fracture and 5,830 age- and gender-matched non-fracture subjects from a community-based cohort of Chinese women and men in Singapore, the Singapore Chinese Health Study (SCHS). We also determined the all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates up to 5 years after hip fracture using hazard ratios (HR) adjusted for hip fracture as a time-dependent covariate and competing risks, for common causes of death such as cancer, coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke, and those associated with immobility such as pneumonia and urinary tract infection.

Methods

Study population

The SCHS is a community-based cohort of 63,257 Chinese women and men, aged 45–74 years enrolled between April 1993 and December 1998 from government housing estates, where 86 % of the entire Singapore population resided at the time of recruitment [8]. Our cohort subjects were drawn from the two major dialect groups of Chinese in Singapore, the Hokkiens and the Cantonese, who originated from two contiguous prefectures of Fujian and Guangdong, respectively, in southern China. At recruitment, each subject was interviewed face-to-face in their home by a trained interviewer using a structured, scanner-readable questionnaire which requested information on demographics, height and weight, use of tobacco, usual physical activity, medical history and alcohol intake. Incidence of invasive cancer after recruitment was identified via linkage with the nationwide cancer registry. The Institutional Review Boards at the National University of Singapore and the University of Minnesota approved this study, and all subjects who were enrolled gave informed consent.

Identification of hip fracture cases among cohort members was accomplished using the ICD-9 code 820 through record linkage of cohort files with databases of the MediClaim System which has captured inpatient discharge information from all private and public hospitals in Singapore since 1990 [9]. All cases identified via linkage were verified by records of the appropriate surgical procedures or manual review of medical records. As of 31 December 2008, after excluding subjects with history of invasive cancer (n = 1,936) or previous hip fracture (n = 100) that had occurred before recruitment, we identified 1,166 incident hip fracture cases via record linkage among the participants of the SCHS. For the analysis, we only included first hip fracture cases and excluded recurrent cases. These formed a cohort of patients with a hip fracture for the present analysis. To create a comparison cohort of patients without hip fracture, we randomly chose five SCHS participants for each hip fracture case who were matched on age at recruitment (±2 years) and gender to the index case and were alive at the time of hip fracture for the index cases, and also excluding subjects with history of invasive cancer or previous hip fracture at recruitment. Among the incident hip fracture cases, 550 cases (47.2 %) underwent ORIF, 564 cases (48.4 %) underwent hemiarthroplasty, 12 had conservative treatment without any surgery (1.0 %) and the operative procedure could not be determined for the remaining 40 cases (3.4 %). As the numbers of subjects who had conservative treatment was small, we only compared all-cause and cause specific mortality between hemiarthroplasty and ORIF.

Ascertainment of mortality

Primary cause of death was identified through record linkage with the Singapore Registry of Births and Deaths. For the current analysis, we updated mortality data through to 31 December 2009. As of June 2011, only 47 subjects of the whole cohort of 63,257 Chinese women and men were known to be lost to follow-up due to migration out of Singapore (0.07 %). This suggests that emigration among participants is negligible in this cohort and that vital statistics in follow-up is virtually complete. Underlying causes of death were coded according to the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision; codes 140–208 were used for cancer deaths, codes 430–438 for stroke deaths, codes 410–414 for CHD deaths, codes 480–487 for pneumonia deaths and code 599 for urinary tract infection deaths.

Statistical analysis

For each index case with fracture and the corresponding non-fracture subjects, the survival time was calculated from the date of first hip fracture of the index case to the date of death or 31 December 2009, whichever occurred first. The Cox proportional hazards model was used to examine the association of hip fracture with all-cause mortality, and the assumption of proportional hazards was checked for individual covariates as well as globally. As the assumption of proportionality was violated with respect to hip fracture, we thus incorporated it as a time-dependent covariate, and quantified its effect at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and 5 years via the HR estimate [10]. In the analysis of cause-specific mortality, deaths due to causes other than that of interest were regarded as competing risks [11]. To model the time-dependency, we have included an interaction term between hip fracture and the natural logarithm of survival time. The effect of hip fracture on cause-specific mortality was modelled using the competing risks regression and quantified based on the sub-distribution HR [12]. To adjust for the potential confounding effects of other demographic and exposure characteristics on the hip fracture–mortality association, the following variables were included in all regression models: education (no formal education, primary, secondary or higher), dialect (Hokkien, Cantonese), smoking status (never, former, current), body mass index (<20, 20 to <24, 24 to <28, 28+ kg/m2), total ethanol (grams per day), weekly moderate activity (no, yes), self-reported history of physician-diagnosed diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke or CHD at recruitment and incidence of cancer between recruitment and hip fracture date (no, yes).

As each hip fracture case was matched to five non-fracture subjects based on age and gender, we created a cluster variable that specified to which matched set each fracture or non-fracture subject belonged. We then generated the robust variance estimate by specifying the ‘cluster’ option in STATA to define the matched set. The standard errors thus estimated appropriately accounted for intragroup correlation within each matched cluster of one fracture and five non-fracture subjects. These were used for the estimation of the 95 % confidence interval (CI) and statistical inference. Statistical computing was conducted using STATA version 12. All cited P values were two-sided, and values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

During the study period, there were 434 deaths (37 %) that occurred among the 1,166 hip fracture cases compared to 1,297 deaths (22 %) among the 5,830 non-fracture cases. The crude mortality rates were 76.2 per 1,000 person-years among hip fracture cases and 38.5 per 1,000 person-years among non-cases. Table 1 shows the baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the cohort with hip fracture cases (n = 1,166) and the one without hip fracture (n = 5,830). Age and gender were matched between the two cohorts. Subjects with hip fractures were generally less educated, more likely to have a history of physician-diagnosed stroke or diabetes mellitus, have lower BMI and to be daily drinkers. Comparing mortality cases with survivals in this study, mortality cases were more likely to be male, older at time of fracture or entry into this study and less educated. They were also more likely to have ever smoked, drink alcohol daily, have a co-morbid history of stroke, diabetes mellitus, CHD or hypertension, and develop cancer subsequent to recruitment.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study subjects according to hip fracture and mortality status

| Characteristic | Hip Fracture |

Mortality |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n=5,830) | Yes (n=1,166) | P value | No (n=5,265) | Yes (n=1,731) | P value | |

| Mean age at fracture/entry, years (SD) | 72.5 (7.2) | 72.8 (7.2) | 0.179 | 72.0 (7.5) | 74.0 (6.0) | <0.001 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, n (%) | ||||||

| <20 | 824 (14.1) | 188 (16.1) | 0.032 | 738 (14.0) | 274 (15.8) | <0.001 |

| 20 to <24 | 3,307 (56.7) | 674 (57.8) | 2,954 (56.1) | 1,027 (59.3) | ||

| 24 to <28 | 1,256 (21.5) | 239 (20.5) | 1,188 (22.6) | 307 (17.7) | ||

| ≥28 | 443 (7.6) | 65 (5.6) | 385 (7.3) | 123 (7.1) | ||

| Gender, n (%) | ||||||

| Males | 1,665 (28.6) | 333 (28.6) | 1.000 | 1,386 (26.3) | 612 (35.4) | <0.001 |

| Females | 4,165 (71.4) | 833 (71.4) | 3,879 (73.7) | 1,119 (64.6) | ||

| Dialect group, n (%) | ||||||

| Cantonese | 2,768 (47.5) | 522 (44.8) | 0.091 | 2,499 (47.5) | 791 (45.7) | 0.201 |

| Hokkien | 3,062 (52.5) | 644 (55.2) | 2,766 (52.5) | 940 (54.3) | ||

| Level of education, n (%) | ||||||

| No formal education | 2,701 (46.3) | 540 (46.3) | 0.010 | 2,373 (45.1) | 868 (50.1) | <0.001 |

| Primary school (1–6 years) | 2,266 (38.9) | 490 (42.0) | 2,099 (39.9) | 657 (38.0) | ||

| Secondary and above | 863 (14.8) | 136 (11.7) | 793 (15.1) | 206 (11.9) | ||

| History of stroke, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 5,731 (98.3) | 1,119 (96.0) | <0.001 | 5,180 (98.4) | 1,670 (96.5) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 99 (1.7) | 47 (4.0) | 85 (1.6) | 61 (3.5) | ||

| History of diabetes mellitus, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 5,173 (88.7) | 943 (80.9) | <0.001 | 4,739 (90.0) | 1,377 (79.6) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 657 (11.3) | 223 (19.1) | 526 (10.0) | 354 (20.5) | ||

| History of coronary heart disease, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 5,480 (94.0) | 1,098 (94.2) | 0.822 | 5,001 (95.0) | 1,557 (91.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 350 (6.0) | 68 (5.8) | 264 (5.0) | 154 (8.9) | ||

| History of hypertension, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 4,132 (70.9) | 813 (69.7) | 0.431 | 3,801 (72.2) | 1,144 (66.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 1,698 (29.1) | 353 (30.3) | 1,464 (27.8) | 587 (33.9) | ||

| Cancer before fracture/entry, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 5,547 (95.2) | 1,094 (93.8) | 0.061 | 5,065 (96.2) | 1,576 (91.1) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 283 (4.9) | 72 (6.2) | 200 (3.8) | 155 (9.0) | ||

| Cigarette smoking, n (%) | ||||||

| Never smokers | 4,221 (72.4) | 816 (70.0) | 0.105 | 3,997 (75.9) | 1,040 (60.1) | <0.001 |

| Former smoker | 675 (11.6) | 134 (11.5) | 557 (10.6) | 252 (14.6) | ||

| Current smokers | 934 (16.0) | 216 (18.5) | 711 (13.5) | 439 (25.4) | ||

| Weekly physical activity, n (%) | ||||||

| No | 4,409 (75.6) | 907 (77.8) | 0.115 | 3,992 (75.8) | 1,324 (76.5) | 0.574 |

| Yes | 1,421 (24.4) | 259 (22.2) | 1,273 (24.2) | 407 (23.5) | ||

| Daily drinkers, n (%) | 153 (2.6) | 42 (3.6) | 0.032 | 141 (2.7) | 54 (3.1) | 0.044 |

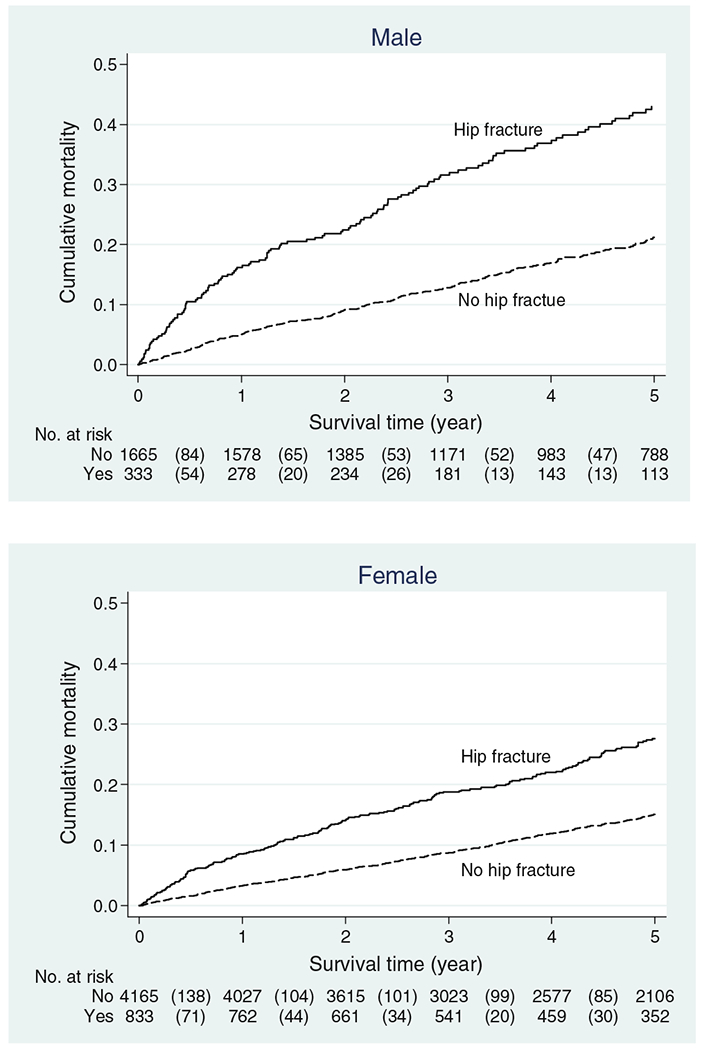

Table 2 lists the unadjusted (crude) HR of hip fractures for all-cause and cause-specific mortality at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and 5 years with hip fracture accounted for as a time-dependent covariate. For all-cause mortality, the crude risk of death 1 year after hip fracture was 2.23 (95 % CI, 1.90–2.60) for females and 2.53 (95 % CI, 2.07–3.09) for males. Table 3 lists the HR of hip fractures for all-cause and cause-specific mortality at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and 5 years post hip fracture, adjusted for other risk factors of mortality, and with hip fracture accounted for as a time-dependent covariate. Figure 1 shows the 5-year cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality among hip fracture and non-fracture subjects for males and females. In both genders, subjects with hip fracture had increased risk of all-cause mortality in the first 5 years after hip fracture as compared to non-fracture subjects. The increase in risk was highest at 3 months after fracture and declined gradually with time. This hip fracture–mortality association was also stronger among men than women though this difference narrowed by 5 years. Five years after hip fracture, a significant increase in risk from all-cause mortality in hip fracture subjects could still be observed for both men (adjusted HR = 1.64; 95 % CI, 1.30–2.06) and women (adjusted HR = 1.58; 95 % CI, 1.35–1.86). For cancer mortality, the increase in risk among hip fracture cases was only observed up to 1 year post hip fracture for both genders. To examine whether patients with pre-existing but undiagnosed hip metastases mainly contributed to increased risk of death in the first post fracture year, we performed sensitivity analysis by excluding deaths within 1 year after hip fracture and found that excess deaths from cancer persisted up to the first post fracture year (adjusted HR = 2.53; 95 % CI, 1.38–4.62 for both genders combined). Hip fracture cases were almost three times as likely to die from stroke compared to non-fracture cases in the first year post fracture, and this increased risk of stroke death was much higher in men compared to women. There was still increased risk at 5 years, although the risk estimate was no longer statistically significant due to relatively small number of stroke deaths. Compared with non-hip fracture subjects, mortality risk from CHD was higher for men only in the first 3 months after hip fracture whereas for women, CHD mortality risk was only higher from 6 months onwards and this increased risk persisted up to 5 years after hip fracture. Compared to their non-fracture counterparts, hip fracture cases were at higher risk of death from pneumonia in both genders; this risk was higher in men than in women from 3 months but the difference narrowed 5 years post-fracture. Furthermore, hip fracture cases also had a more than 2-fold risk of mortality from urinary tract infection for up to 5 years, and this risk was higher in women as compared to men.

Table 2.

Unadjusted (crude) hazard/subdistribution hazard ratios (with 95 % CI) of hip fracture for all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and 5 years

| Cause of death | Hip fracture cases (%)a | Non-hip fracture cases (%)a | 3 months | 6 months | 1 year | 5 years |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-causes | ||||||

| All | 434 (37.2) | 1,297 (22.3) | 3.08 (2.50–3.79) | 2.68 (2.28–3.15) | 2.33 (2.06–2.63) | 1.68 (1.48–1.91) |

| Female | 282 (33.9) | 837 (20.1) | 2.75 (2.11–3.60) | 2.47 (2.01–3.05) | 2.22 (1.90–2.60) | 1.73 (1.48–2.02) |

| Male | 152 (45.7) | 460 (27.6) | 3.68 (2.62–5.16) | 3.05 (2.35–3.96) | 2.53 (2.07–3.09) | 1.64 (1.31–2.06) |

| Cancer | ||||||

| All | 86 (7.4) | 355 (6.1) | 2.49 (1.61–3.88) | 1.99 (1.41–2.81) | 1.59 (1.21–2.09) | 0.94 (0.71–1.25) |

| Female | 49 (5.9) | 210 (5.0) | 2.41 (1.33–4.36) | 1.92 (1.21–3.05) | 1.53 (1.06–2.20) | 0.90 (0.62–1.32) |

| Male | 37 (11.1) | 145 (8.7) | 2.61(1.35–5.04) | 2.10 (1.25–3.53) | 1.69 (1.12–2.56) | 1.02 (0.66–1.59) |

| Stroke | ||||||

| All | 55 (4.7) | 137 (2.4) | 5.07 (12.48–10.35) | 3.84 (2.23–6.61) | 2.91 (1.95–4.34) | 1.53 (1.05–2.21) |

| Female | 37 (4.4) | 103 (2.5) | 3.38 (1.53–7.46) | 2.80 (1.53 –5.14) | 2.32 (1.47–3.65) | 1.49 (0.97 –2.31) |

| Male | 18 (5.4) | 34 (2.0) | 16.94 (2.79–102.75) | 9.70 (2.51–37.55) | 5.56 (2.16–14.28) | 1.52 (0.72– 3.20) |

| Coronary heart disease | ||||||

| All | 85 (7.3) | 272 (4.7) | 2.08 (1.30–3.32) | 1.92 (1.33–2.76) | 1.77 (1.33–2.35) | 1.47 (1.11–1.94) |

| Female | 63 (7.6) | 178 (4.3) | 1.94 (1.04–3.65) | 1.91 (1.17–3.11) | 1.87 (1.29–2.71) | 1.79 (1.31–2.44) |

| Male | 22 (6.6) | 94 (5.7) | 2.37 (1.16–4.86) | 1.81 (1.03–3.18) | 1.38 (0.86–2.22) | 0.74 (0.39–1.40) |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| All | 83 (7.1) | 202 (3.5) | 3.97 (2.37–6.64) | 3.29 (2.20–4.91) | 2.72 (2.00–3.71) | 1.76 (1.30–2.38) |

| Female | 48 (5.8) | 128 (3.1) | 2.20 (1.08–4.47) | 2.11 (1.21–3.68) | 2.03 (1.33–3.11) | 1.86 (1.28–2.71) |

| Male | 35 (10.5) | 74 (4.4) | 8.54 (3.45–21.12) | 5.77 (2. 90–11.46) | 3.89 (2.34–6.47) | 1.57 (0.92–2.65) |

| Urinary tract infection | ||||||

| All | 24 (2.1) | 45 (1.0) | 4.73 (1.97–11.35) | 3.95 (1.99–7.84) | 3.30 (1.91–5.70) | 2.18 (1.17–4.06) |

| Female | 20 (2.4) | 32 (1.0) | 5.44 (2.02–14.67) | 4.58 (2.10–10.00) | 3.85 (2.06–7.19) | 2.58 (1.30–.11) |

| Male | 4 (1.2) | 13 (1.0) | 3.31 (0.44–24.67) | 2.56 (0.57– 11.54) | 1.99 (0.61–6.43) | 1.10 (0.21–5.80) |

The number and percentages of deaths are based on the end of study date which was 31 December 2009

Table 3.

Adjusted subdistribution hazard ratios (with 95 % CI) of hip fracture for all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and 5 years

| Cause of death | Hip fracture cases (%)a | Non-hip fracture cases (%)a | 3 monthsb | 6 monthsb | 1 yearb | 5 yearsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-causes | ||||||

| All | 434 (37.2) | 1,297 (22.3) | 2.82 (2.28–3.47) | 2.46 (2.09–2.89) | 2.14 (1.89–2.44) | 1.56 (1.37–1.79) |

| Female | 282 (33.9) | 837 (20.1) | 2.47 (1.88 –3.23) | 2.22 (1.80–2.75) | 2.01 (1.70–2.36) | 1.58 (1.35–1.86) |

| Male | 152 (45.7) | 460 (27.6) | 3.54 (2.53–4.97) | 2.96 (2.28–3.85) | 2.48 (2.02–3.04) | 1.64 (1.30–2.06) |

| Cancer | ||||||

| All | 86 (7.4) | 355 (6.1) | 2.39 (1.54–3.69) | 1.91 (1.36–2.70) | 1.53 (1.17–2.01) | 0.92 (0.69–1.23) |

| Female | 49 (5.9) | 210 (5.0) | 2.36 (1.31–4.23) | 1.87 (1.19–2.96) | 1.49 (1.04–2.13) | 0.87 (0.59–1.28) |

| Male | 37 (11.1) | 145 (8.7) | 2.54 (1.33–4.86) | 2.07 (1.23–3.46) | 1.68 (1.11–2.55) | 1.04 (0.66–1.63) |

| Stroke | ||||||

| All | 55 (4.7) | 137 (2.4) | 4.81 (2.36–9.82) | 3.63 (2.11–6.27) | 2.74 (1.83–4.11) | 1.43 (0.98–2.10) |

| Female | 37 (4.4) | 103 (2.5) | 3.24 (1.47–7.11) | 2.67 (1.46–4.89) | 2.21 (1.40–3.47) | 1.41 (0.91–2.20) |

| Male | 18 (5.4) | 34 (2.0) | 15.83 (2.62–95.68) | 9.03 (2.33–35.03) | 5.15 (1.97–13.42) | 1.40 (0.63–3.09) |

| Coronary heart disease | ||||||

| All | 85 (7.3) | 272 (4.7) | 1.85 (1.16–2.95) | 1.70 (1.18–2.45) | 1.57 (1.18–2.08) | 1.29 (0.97–1.72) |

| Female | 63 (7.6) | 178 (4.3) | 1.70 (0.91–3.19) | 1.67 (1.02–2.72) | 1.63 (1.12–2.37) | 1.55 (1.12–2.14) |

| Male | 22 (6.6) | 94 (5.7) | 2.19 (1.09–4.43) | 1.68 (0.97–2.92) | 1.28 (0.80–2.06) | 0.69 (0.36–1.33) |

| Pneumonia | ||||||

| All | 83 (7.1) | 202 (3.5) | 3.68 (2.19–6.18) | 3.04 (2.02–4.56) | 2.51 (1.83–3.45) | 1.61 (1.18–2.20) |

| Female | 48 (5.8) | 128 (3.1) | 2.05 (1.00–4.19) | 1.96 (1.12–3.43) | 1.87 (1.21–2.89) | 1.68 (1.13–2.49) |

| Male | 35 (10.5) | 74 (4.4) | 8.18 (3.28–20.39) | 5.53 (2.75–11.15) | 3.74 (2.21–6.34) | 1. 51 (0.88–2.60) |

| Urinary tract infection | ||||||

| All | 24 (2.1) | 45 (1.0) | 4.33 (1.78–10.56) | 3.63 (1.79–7.35) | 3.04 (1.72–5.40) | 2.02 (1.05–3.89) |

| Female | 20 (2.4) | 32 (1.0) | 4.83 (1.75–13.34) | 4.07 (1.80–9.19) | 3.43 (1.76–6.70) | 2.31 (1.11–4.81) |

| Male | 4 (1.2) | 13 (1.0) | 3.28 (0.46–23.37) | 2.58 (0.60–11.08) | 2.02 (0.64–6.40) | 1.15 (0.20–6.57) |

The number and percentages of deaths are based on the end of study date which 31 December 2009

Model was adjusted for education (no formal education, primary, secondary or higher), dialect (Hokkien, Cantonese), smoking status (never, former, current), body mass index (<20, 20 to <24, 24 to <28, 28+ kg/m2 ), total ethanol (grams per day), weekly moderate activity, self-reported history of physician-diagnosed diabetes mellitus, hypertension, stroke or CHD at recruitment and incidence of cancer between recruitment and hip fracture date

Fig. 1.

Cumulative incidence of all-cause mortality according to hip fracture for males and females

We compared the difference in mortality risk in patients with hip fracture who underwent hemiarthroplasty with those who underwent ORIF at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and 5 years, and there was no difference in mortality rates between these two groups at any of the four time-points.

Discussion

After adjusting for other co-morbidities and risk factors, we found hip fracture cases had a higher risk of all-cause mortality compared to non-fracture cases for up to 5 years post fracture. The excess in mortality for 5 years post fracture was contributed by increased risk in deaths from CHD, pneumonia and urinary tract infection.

Most studies reported that the mortality was the highest in the first 3 months post fracture [2, 6]. In a time-to-event meta-analysis of controlled prospective cohort studies by Haentjens et al. [6], it was found that excess all-cause mortality persisted up to 10 years after hip fracture for both genders. Geographical differences in all-cause mortality 1 year after hip fracture was also noted with the lowest rates reported in Southeast Asia. However, this finding was later criticized by LeBlanc et al. as the meta-analysis did not adjust for age and co-morbidities, which could account for much of the increased mortality risk after hip fracture. In the same paper, LeBlanc et al. [13] subsequently demonstrated that the excess in all-cause mortality from hip fracture among US women aged 70–79 years and those aged 80 years and above with good or excellent self-reported health disappeared after 1 year, and these findings were consistent with an earlier study in Norway [14]. However, our study found that even after adjusting for age and co-morbidities, the excess risk of death from all causes persisted up to 5 years after hip fracture for both genders. In their meta-analysis, Haentjens et al. [6] also found that the pooled unadjusted (crude) HR for all-cause mortality 1 year after hip fracture in women and men was highest in Australia (6.09 [95 % CI, 4.37–8.48] and 8.78 [95 % CI, 6.05–12.76], respectively), moderate in Europe (2.90 [95 % CI, 2.52–3.34] and 3.76 [95 % CI, 3.20–4.42], respectively) and low in North and South America (2.55 [95 % CI, 1.96–3.30] and 3.27 [95 % CI, 2.85–3.75], respectively). However, HR for all-cause mortality 1 year after hip fracture in women was the lowest in Southeast Asia at 2.29, which was based on only one study on women. In our study, we found that the crude HR for all-cause mortality 1 year after hip fracture in women was similar to that reported in the Asian study of Haentjens et al.’s meta-analysis [7], and this was also lower than the effect estimates from Australia, Europe and the Americas. Thus, there is a suggestion that the risk of death from all causes among hip fracture subjects is lower in Asia than other parts of the world. However, as these effects estimates are from only two studies, more data from other Asian countries are needed to confirm this observation.

Most research has found greater excess in all-cause mortality after hip fracture in men as compared with women [6, 15]. However, when cause-specific mortality was considered, we found that gender differences in mortality rates after hip fracture were dependent on the cause of death. For example, although risk of mortality from cancer, stroke and pneumonia were generally higher for hip fracture cases among men than among women, risk of mortality from urinary tract infections was higher for women than for men. Similarly, although the excess risk of death from all causes persisted up to 5 years after hip fracture, there were temporal differences in excess mortality risk for different causes of death. For example, while excess mortality risk from pneumonia and CHD after hip fracture persisted up to 5 years for females, excess mortality risk from cancer and stroke were only observed up to 1 year after hip fracture for both genders. The explanation for the greater risk of death from pneumonia and urinary tract infection after hip fracture is relatively straightforward as these are known consequences of immobility which is associated with hip fractures. The greater risk of death from cancer after hip fracture could be due to the some hip fractures being pathological secondary to bony metastases and hence, such patients were already in the late stages of cancer at the time of hip fracture. This hypothesis would also explain why the excess risk from dying from cancer only lasts till the first year after hip fracture. Unfortunately, we do not have access to information on bony metastases at the time of hip fracture to test this hypothesis. However, despite excluding deaths within 1 year after hip fracture, we still found the excess risk from dying from cancer persisted in the first post fracture year, particularly among males The explanation as to why the risk of death from stroke and CHD are higher in hip fracture patients may be related to biological mechanisms linking the osteoporosis process underlying hip fractures and atherosclerosis. As proposed by Kado et al. [16], the cytokine interleukin-6 levels which increase with age [17] stimulates osteoclasts to increase rates of bone remodelling and bone loss [18], and concurrently promotes atherosclerotic plaque formation and possibly rupture [19]. Another hypothesis may involve dysregulation of the metabolism of homocysteine, an amino acid which is increased in homocystinuria, a genetically inherited disease of cystathionine β-synthase deficiency where sufferers experience premature osteoporosis and thromboembolic events such as strokes and myocardial infarctions [20]. A third possibility is based on the observation that mice that were deficient in extracellular matrix Gla protein had extensive atherosclerotic calcification and osteoporosis, thus raising the hypothesis that dysregulation of matrix proteins may lead to abnormal mineralization of bone and arteries [21].

In this study, we also compared mortality risk between types of surgery. There are two main types of hip fractures: femoral neck and pertrochanteric fractures. Generally, while most pertrochanteric fractures are surgically treated with ORIF, displaced femoral neck fractures are treated with hemiarthroplasty and undisplaced femoral neck fractures by ORIF [20]. There is a theoretical risk of greater likelihood of mortality from relative immobility with ORIF than with hemiarthroplasty because patients treated with the former are generally non-weight bearing for 4–6 weeks while those treated with the latter can weight-bear immediately after surgery. However, most studies suggest that there is no difference in mortality rates between type of hip fracture [22] or type of hip fracture surgery [23], although a study among elderly Americans in the US found a modestly lower 3-month mortality rate for hip fracture patients treated with ORIF as compared to hemiarthroplasty [21]. However, these studies were limited to Western populations and difference in mortality rates between types of hip fracture surgery has never been studied in Asian populations. Our finding of no difference in mortality risk between hemiarthroplasty and ORIF at 3 months or any time-point up to 5 years suggests that the 4–6 weeks of non-weight bearing for hip fracture patients treated with ORIF does not have significant effect on short and long term survival, when compared to hemiarthroplasty where patients can weight-bear almost immediately, in our population.

The strength of this study is the use of an established community-based cohort, its large sample size of 1,166 hip fracture patients and 5,830 randomly selected matched non-fracture subjects, reporting of cause-specific mortality rates for both genders, accounting for hip fracture as a time-dependent covariate, and implementation of competing risks analysis to account for competing causes of mortality. Singapore is a small city–state where there is good access to specialized medical care. The outcome of mortality was obtained via linkage with the nationwide death registry and could be considered to be highly comprehensive. Our study is also the only Asian study so far to examine excess mortality after hip fracture beyond 2 years for both genders. Nevertheless, this study has its limitations as we did not have information on post-operative complications, presence of other co-morbidities at the time of hip fracture or functional status. Persons with post-operative complications, cancer with bone metastases and functional deficits are more likely to sustain a hip fracture and have increased mortality risk unrelated to the hip fracture. Moreover, when interpreting mortality on an absolute scale, it should be noted that our study population was restricted to persons aged 45–74 years at baseline so mortality rates would be expected to be lower in studies including subjects younger than 45 years. Lastly, a sensitivity analysis for all-cause mortality using the standard Cox regression model censoring at 3 months showed similar results as the time-varying model based on the natural logarithm of survival time. This suggests that the time-dependent covariate model based on the natural logarithm of survival time fits the data reasonably well.

In conclusion, this study found that even after adjusting for co-morbidities, excess all-cause mortality persist for up to 5 years after hip fracture for both genders in an Asian population. The 1-year mortality risk was similar to other Asian studies and was lower than North and South America, Europe and Australia. There were also differences in the risk of cause-specific mortality between genders and over time. These findings have implications in the management and counselling of patients and their families on short and long-term outcomes after hip fracture. Future research should focus on new strategies and interventions targeted to reduce cause-specific mortality from infections such as pneumonia and urinary tract infections, and hence reduce the global burden of the consequences of osteoporotic hip fractures.

Acknowledgments

We thank Siew-Hong Low of the National University of Singapore for supervising the field work of the Singapore Chinese Health Study and Renwei Wang for the maintenance of the cohort study database. We also thank the Ministry of Health in Singapore for assistance with the identification of hip fracture cases and mortality via database linkages. Finally, we acknowledge the founding, long-standing Principal Investigator of the Singapore Chinese Health Study — Mimi C Yu. This study was supported by the National Medical Research Council, Singapore (NMRC/EDG/0011/2007) and National Institutes of Health, USA (NCI RO1 CA55069, R35 CA53890, R01 CA80205, and R01 CA144034).

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest None

Contributor Information

G. C.-H. Koh, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, National University Health System, Block MD3, #03-20, 16 Medical Drive, 117597, Singapore, Singapore; Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, National University Health System, Singapore, Singapore

B. C. Tai, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, National University Health System, Block MD3, #03-20, 16 Medical Drive, 117597, Singapore, Singapore; Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, National University Health System, Singapore, Singapore

L.-W. Ang, Epidemiology and Disease Control Division, Ministry of Health, Singapore, Singapore

D. Heng, Public Health Group, Ministry of Health, Singapore, Singapore

J.-M. Yuan, Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences, University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute, Pittsburgh, PA, USA; Department of Epidemiology, University of Pittsburgh Graduate School of Public Health, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

W.-P. Koh, Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, National University of Singapore, National University Health System, Block MD3, #03-20, 16 Medical Drive, 117597, Singapore, Singapore; Duke-NUS Graduate Medical School Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

References

- 1.Johnell O, Kanis JA (2006) An estimate of the worldwide prevalence and disability associated with osteoporotic fractures. Osteoporos Int 17:1726–1733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Haleem S, Lutchman L, Mayahi R, Grice JE, Parker MJ (2008) Mortality following hip fracture: trends and geographical variations over the last 40 years. Injury 39:1157–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kyo T, Takaoka K, Ono K (1993) Femoral neck fracture; factors related to ambulation and prognosis. Clin Orthop 292:215–222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kitamura S, Hasegawa Y, Suzuki S, Sasaki R, Iwata H, Wingstrand H, Thorngren KG (1998) Functional outcome after hip fracture in Japan. Clin Orthop Relat Res 348:29–36 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nather A, Seow CS, Iau P, Chan A (1995) Morbidity and mortality for elderly patients with fractured neck of femur treated by hemiarthroplasty. Injury 26:187–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haentjens P, Magaziner J, Colón-Emeric CS, Vanderschueren D, Milisen K, Velkeniers B, Boonen S (2010) Meta-analysis: excess mortality after hip fracture among older women and men. Ann Intern Med 152:380–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jitapunkul S, Yuktanandana P (2000) Consequences of hip fracture among Thai women aged 50 years and over: a prospective study. J Med Assoc Thai 83:1447–1451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hankin JH, Stram DO, Arakawa K, Park S, Low SH, Lee HP, Yu MC (2001) Singapore Chinese Health Study: development, validation, and calibration of the quantitative food frequency questionnaire. Nutr Cancer 39:187–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heng DM, Lee J, Chew SK, Tan BY, Hughes K, Chia KS (2000) Incidence of ischaemic heart disease and stroke in Chinese, Malays and Indians in Singapore: Singapore Cardiovascular Cohort Study. Ann Acad Med Singap 29:231–236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Collett D (2003) Modeling survival data in medical research, 2nd edn. Chapman and Hall, London [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tai BC, Machin D, White I, Gebski V (2001) Competing risks analysis of patients with osteosarcoma: a comparison of four different approaches. Stat Med 20:661–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tai BC, Wee J, Machin D (2011) Analysis and design of randomised clinical trials involving competing risks outcomes. Trials 12:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LeBlanc ES, Hillier TA, Pedula KL, Rizzo JH, Cawthon PM, Fink HA, Cauley JA, Bauer DC, Black DM, Cummings SR, Browner WS (2011) Hip fracture and increased short-term but not long term mortality in healthy older women. Arch Int Med 171:1831–1837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsen L, Sogaard AJ, Meyer HE, Edna T-H, Kopjar B (1999) Survival after hip fracture: short and long-term excess mortality according to age and gender. Osteoporos Int 10:73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kannegaard PN, Van der Mark S, Eiken P, Abrahamsen B, Excess mortality in men compared with women following hip fracture (2010) National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival. Age Ageing 39:203–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kado DM, Browner WS, Blackwell T, Gore R, Cummings SR (2000) Rate of bone loss is associated with mortality in older women: a prospective study. J Bone Miner Res 15:1974–1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ershler WB (1993) Interleukin-6: a cytokine for gerontologists. J Am Geriatr Soc 41:176–181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Papanicolaou DA, Wilder RL, Manolagas SC, Chrousos GP (1998) The pathophysiologic roles of interleukin-6 in human disease. Ann Intern Med 128:127–137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris TB, Ferrucci L, Tracy RP, Chiara C, Wacholder S, Ettinger WH, Heimovitz H, Cohen HJ, Wallace R (1999) Associations of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in the elderly. Am J Med 106:506–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boushey CJ, Beresford SA, Omenn GS, Motulsky AG (1995) A quantitative assessment of plasma homocysteine as a risk factor for vascular disease. Probable benefits of increasing folic acid. JAMA 274:1049–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lu-Yao GL, Baron JA, Barrett JA, Fisher ES (1994) Treatment and survival among elderly Americans with hip fractures: a population-based study. Am J Public Health 84:1287–1291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giversen IM (2007) Time trends of mortality after first hip fractures. Osteoporos Int 18:721–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Skinner P, Riley D, Ellery J, Beaumont A, Coumine R, Shafighian B (1989) Displaced subcapital fractures of the femur: a prospective randomized comparison of internal fixation, hemiarthroplasty and total hip replacement. Injury 20:291–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]