Abstract

A sustainable approach for C–C cross-coupling reaction at room temperature in water has been developed to avoid tedious Pd separation, reduce the carbon footprint, and save energy. Another important aspect is the catalyst recycling and easy product separation. α,γ-Hybrid peptides were designed to selectively use as a ligand for C–C cross-coupling catalysts as well as to form organogels. The peptides form antiparallel sheet-like structures in the solid state. The peptide containing m-aminobenzoic acid, glycine, and dimethylamine forms a whitish gel in toluene, and co-gelation with Pd(OAc)2 results in light brown gel, which acts as a biphasic catalyst for Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling at room temperature in water by mild shaking. The organic–inorganic hybrid gel was characterized by rheology, field-emission scanning electron microscopy, transmission electron microscopy, and energy-dispersive X-ray analyses. On completion of the cross-coupling reaction, the basic aqueous layer (containing products) above the gel can be simply decanted and the intact organic–inorganic hybrid gel can be recycled by topping-up fresh reactants multiple times. The reaction permitted a range of different substitution patterns for aryl and heterocyclic halides with acid or phenol functional groups. Both electron-donating- and electron-withdrawing-substituted substrates exhibited good results for this transformation. The findings inspire toward a holistic green technology for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction and an innovative avenue for catalyst recycling and product isolation.

Introduction

C–C cross-coupling is one of the popular reactions for the synthesis of drugs, pesticides, polymers, and liquid crystals.1−6 For a sustainable environment, “green” approaches in C–C coupling are important.7−9 In this regard, water replaces the toxic organic solvents.10,11 Recycle and reuse of catalysts are also desirable from environmental and economic points of view.12 Hence, the development of a green process for C–C coupling with enhanced reactivity and selectivity and catalyst recycling at room temperature is highly challenging.13−16 In the 1970s, the biphasic process for the facile separation of the catalyst solvated in the aqueous phase and the product present in the organic layer has been developed.17,18 However, typical solids do not impart the nonpolar environments frequently needed for organic reactions in the biphasic process. In the reaction medium, the metal, appropriate ligands, and solvents exhibit the required geometry and maintain the transition state of the reaction.19−21 Supramolecular gel can mimic such an ecology and may provide a “solvent”-like local environment to show the catalytic functionality.22−25

Since catalyst recycling is highly challenging in homogeneous catalysis,26,27 we attempt to find a simple method for product separation and catalyst recycling at room temperature (RT) and under mild conditions. We adopt the concept of biphasic catalysis that allows easy separation of the layers and catalyst recycling.28,29 In benchmark investigation, we use an eco-friendly self-assembling peptide-based organogel and water as the biphasic operation medium for C–C cross-coupling. Previously, we have reported that Pd-embedded magnetic nanoparticles can be used as catalysts for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling.30 We have also discussed the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction using gold nanoparticles.31 Herein, we develop an environment-friendly, efficient, and easy method for synthesizing Pd-embedded organic–inorganic hybrid gel (Figure 1). The α,γ-hybrid peptides containing m-aminobenzoic acid, glycine, and dimethylamine form sonication-induced opaque whitish gel in toluene. The cogelation with Pd(OAc)2 results in light brown gel. We report the comprehensive characterization of the organic–inorganic hybrid gel by rheology, powder X-ray diffraction, field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray analyses. Further, we have used this Pd-embedded organic–inorganic hybrid gel as a catalyst for the C–C cross-coupling at RT in water by mild shaking only (Figure 1). On completion of the cross-coupling reactions, the aqueous basic layer above the gel can be simply decanted and the intact gel is reusable for multiple cycles. The products can be collected by acidification of the decanted basic layer and filtration (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic presentation of the peptides 1–3, self-assembly to fibers, Pd-embedded fibers as a cross-coupling catalyst, and the strategy for sustainable biphasic C–C cross-coupling reaction, product isolation, and catalyst recycling at room temperature.

Experimental Section

Synthetic Procedure of the Peptide

The peptides had been synthesized by a traditional method in the solution state. The amino acid had been protected by methyl esterification of the acid part, and the amine part had been protected by the tert-butoxycarbonyl (Boc) group. The acid and amine were coupled by using dicyclohexylcarbodiimide as a coupling agent and hydroxybenzotriazole to stop the recemization. The products were purified by column chromatography using silica gel (100–200 mesh size), and n-hexane and ethyl acetate solution at different ratios were used as the eluent. The characterization of intermediates and final products of a reaction was done by proton nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) (400 MHz Jeol and 500 MHz Bruker spectrometer) spectroscopy, 13C NMR (100 and 125 MHz) spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) spectroscopy analyses. Further, the single crystals of peptides 1–3 were analyzed by X-ray crystallography. For details, see the Supporting Information.

NMR Experiments

For characterization of the products, NMR spectroscopy had been performed using a 400 MHz Jeol or 500 MHz Bruker spectrometer. Samples for NMR analysis were prepared in DMSO-d6 or CDCl3 solvent of a 1–10 mM range of concentration.

FT-IR Experiments

For the FT-IR study in the solid state, a KBr disk with the compound was prepared, and the experiment had been performed with a Perkin Elmer Spectrum RX1 spectrophotometer.

Mass Spectrometry Experiment

Mass spectrometry of the peptides was performed with a Waters Corporation Q-T of Micro YA263 mass spectrometer using electrospray ionization (positive-mode).

Absorption Spectroscopy Experiment

The peptides’ UV–vis absorption spectra were measured with a Perkin Elmer UV/vis spectrometer (Lambda 35), and a quartz cell having a 1 cm path length was used for the measurment.

Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscopy

FE-SEM images had been carried out to study the morphologies of the peptides. Peptide solution was drop-cast on a glass cover slip and desiccated. Gold coating was done for the prepared samples, and the images of the morphologies were snapped using a Jeol Scanning Microscope-JSM-6700F instrument.

Transmission Electron Microscopy

TEM images of the peptides had been taken to study the morphologies of the gel, which was synthesized using peptide 1. A little amount of the gel was put on a copper grid and desiccated. TEM images were taken using a JEM2100 Plus TEM instrument.

Gelation Process

The peptide 3 (15 mg) was taken in the solvent (1 mL), and then, heating was done to dissolve it, followed by sonication of the gel. Then, 10 mg of peptide 1 and 0.1 mg (0.0004 mmol) of Pd(OAc)2 were taken in 500 μL of solvent. Then, the combination was heated to dissolve and then sonicated for 15 min, and the Pd-doped gel was made.

Rheological Analysis

To study the mechanical strength of the organogel, rheological experiments had been carried out using an Anton Paar modular compact rheometer (MCR 102 Instrument). A steel parallel plate of an 8 mm diameter was used to perform the experiment. A Peltier circulator thermo cube was affixed with a rheometer to maintain the temperature precisely at 25 °C throughout the experiment. Then, we have measured the storage (G′) and loss (G″) moduli of the organogel using this setup.

X-ray Crystallography Analysis

Single and transparent crystals of peptides 1–3 had been obtained from different solutions through solvent evaporation. A Bruker APEX-2 CCD diffractometer was used to measure the data with MoKα (peptide 2) or CuKα (peptides 1 and 3) radiation. A Bruker SAINT package was used to analyze the data. SHELX97 was used for solving and refinement of the structure. Nonhydrogen atoms were refined by anisotropic thermal parameters. The data for the crystals of peptides 1–3 are reported in CCDC 2080597 (1), 2080595 (2), and 2080601 (3), respectively.

Formation and Immobilization of Pd Nanoparticles

First, 10 mg of peptide 1 and 0.1 mg (0.0004 mmol) of Pd(OAc)2 were taken in 500 μL of solvent. Then, the solution was heated to dissolve and then sonicated for 15 min, and the Pd-doped gel was formed. Here, peptide 1 acts as a reducing agent that can reduce Pd(II) to Pd(0). The urea moiety can act as a reducing agent. Peptide 1 contains a semiurea type moiety, which acts as a reducing agent here. Hence, through the gel formation process, by heating and sonication with compound 1 and Pd(II), Pd(II) reduces to Pd(0). We did not remove any Pd(II), so the residual Pd(II) also is in the gel matrix.

Results and Discussion

The necessity to perform C–C coupling reactions at RT with low-cost ligands and low catalyst loading will help to minimize the requirement of palladium, which will reduce cost and be beneficial for the environment.32,33 Moreover, these types of sustainable coupling processes can be used with minimum effort for the recycling of palladium. Hence, we are looking for a ligand that will form a separate phase, take part in the reaction, and entrap the palladium and can be recycled for multiple cycles without any processing. For the ligand, we have designed both chiral and achiral α,γ-hybrid peptide-based organogelators (Figure 1).34 The α,γ-hybrid peptides 1, 2, and 3 (Scheme S1) were designed to selectively use as a ligand for C–C cross-coupling catalysts as well as to form gel in aromatic solvents through noncovalent interactions. The design principle was that the achiral Gly with the smallest size should have a minimum interference on the peptide folding and assembly. The comparatively bulky and chiral Ala will affect peptide conformation as well as self-assembly. The Phe analogue may impart additional π–π interactions. Moreover, the amide groups will include hydrogen bonding and can serve for C–C cross-coupling catalyst preparation. Target peptides 1–3 were synthesized by solution-phase coupling following a high purity, as depicted by 1H NMR, 13C NMR, FT-IR spectroscopy, and mass spectrometry (MS) investigations (see the Supporting Information).

The α,γ-hybrid peptides 1, 2, and 3 were also analyzed by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. Colorless crystals of peptides 1, 2, and 3 suitable for X-ray crystallography were obtained from the corresponding methanol–water solutions by slow evaporation. The asymmetric unit contains one molecule of achiral peptide 1. The torsion angles (ϕ1 160.67°, ψ1 −148.34°, ϕ2 92.18°, and ψ2 −171.54°) of peptide 1 indicate for an extended backbone conformation (Figure S1, ESI†). The packing diagram shows that the peptide 1 molecules form intermolecular hydrogen-bonded antiparallel sheet-like structures (Figure 2a) along the crystallographic b direction. By replacing Gly with l-Ala, peptide 2 also adopts an extended backbone conformation (ϕ1 −170.22°, ψ1 148.33°, ϕ2 −84.59°, and ψ2 161.99°) (Figure S2, ESI†). In higher-order assembly, the peptide 2 molecules developed an antiparallel sheet-like structure stabilized by multiple intermolecular hydrogen bonds (Figure S4a, ESI†) along the crystallographic c direction. Hence, the incorporation of chirality and enhanced hydrophobicity have little effect on the structure and assembly. Peptide 3 having l-Phe also depicts a kink-like conformation (ϕ1 −155.36°, ψ1 47.28°, ϕ2 −101.83°, and ψ2 126.52°) (Figure S3, ESI†). From the packing diagram, the peptide 3 molecules form intermolecular hydrogen-bonded antiparallel sheet-like structures (Figure S4b, ESI†) along the crystallographic a direction. The sheet-like structure is also stabilized by T-shape π–π stacking interaction between m-aminobenzoic acid and the Phe side chain (Figure S4b, ESI†). The hydrogen bonding parameters of peptides 1, 2, and 3 are listed in Table S1.

Figure 2.

(a) Chemical diagram and (b) antiparallel sheet-like structure of peptide 1. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dotted lines. Carbon is gray, nitrogen is blue, and oxygen is red.

The α,γ-hybrid peptide 1 forms a sonication-induced strong organogel in xylene, toluene, chlorobenzene, and 1,2-dichlorobenzene.35 The stuff was preliminarily categorized as a gel, as it did not obey gravitational flow upon turning the tube upside-down at RT (Figures 3a and S5, ESI†). The minimum gelation concentration (MGC) was 10 mg/mL in chlorobenzene and 15 mg/mL in toluene. The α,γ-hybrid peptides 2 and 3 form sonication-induced gel at high concentrations (MGC 20 mg/mL). Hence, hereafter we will focus only on α,γ-hybrid peptide 1.

Figure 3.

(a) Peptide 1 sonication-induced gel in toluene. (b) Storage modulus and loss modulus vs angular frequency for a 3 wt % peptide 1 gel in toluene at RT. (c) FE-SEM image showing an entangled fiber morphology in the gel. (d) Sonication-induced Pd-embedded peptide 1 hybrid gel in toluene; (e) dynamic storage modulus and loss modulus of the Pd-embedded peptide 1 hybrid gel. (f) TEM image showing Pd nanoparticles embedded in the peptide 1 gel matrix; inset: Pd nanoparticles on the surface of the gel fibers.

Infrared spectroscopy is an excellent technique to examine the self-assembly nature of the peptides in gel.36 The FT-IR spectra (Figure S6, ESI†) of peptide 1 xerogel exhibit a N–H stretching frequency at 3232 cm–1 for hydrogen-bonded N–H and amide peaks at 1681, 1617, and 1533 cm–1 indicating the presence of H-bonded antiparallel sheet-like structures.36 Peptide 2 exhibits a peak at 3239 cm–1 for N–H stretching frequencies. The amide bands have appeared at 1699, 1612, and 1526 cm–1 (Figure S6, ESI†). Peptide 3 exhibits N–H stretching frequencies at 3200 cm–1 for hydrogen-bonded N–H and amide peaks at 1696, 1599, and 1512 cm–1 (Figure S6, ESI†), indicating the presence of H-bonded antiparallel kink-like structures.

The organogel formed by α,γ-hybrid peptide 1 in 1,2-dichlorobenzene is so steady that the gel is perhaps suspended by holding one edge and can be sculpted into any self-supporting geometrical form.37 Also, a big organogel block of peptide 1 can be cut up into multiple pieces (Figure S7, ESI†).38,39 The organogel formed by α,γ-hybrid peptide 1 showed significant self-healing nature. Several small blocks of gel could amalgamate into a continuous, stable self-supporting bar (Figure S7, ESI†).38,39 The fusion of a rhodamine 6G-doped block with an undoped block confirmed the diffusion of dye through the undoped gel block, which suggested the dynamic trafficking of dissolved peptide 1 molecules over the merging interface (Figure S7, ESI†). To know about the structural evolution on sonication of the α,γ-hybrid peptide 1, X-ray diffraction experiments have been carried out with xerogels from toluene (Figure S8, ESI†). On comparing the spectra with the crystal, it is clear that sonication has significant impact on the structure and assembly of peptide 1. Rheology provides the information regarding the tertiary structure (the kind of network) presence in a gel. The elastic response (G′, storage modulus) and the viscous response (G″, loss modulus) of gel were investigated as a function of shear strain at 25 °C and frequency 10 rad s–1. For peptide 1 gel, G′ was approximately an order of magnitude larger than G″ (Figure 3b). Hence, the gel has elastic nature due to the physical crosslink. G′ and G″ have not intersected each other, which suggests that the gel is stable and rigid. Moreover, we have employed FE-SEM to examine the morphology of the gel. The FE-SEM images of the peptide 1 xerogel from toluene show an entangled unbranched fiber morphology (Figure 3c). The fibers have diameters ca. 400 nm and several micrometers in length (Figure 3c). These fiber networks immobilize the solvents and help to form a gel.

The sonication-induced organogelation of peptide 1 in the presence of Pd(OAc)2 results in a light brown color opaque gel (Figure 3d). This is due to the formation of Pd from the reduction of Pd(OAc)2 by peptide 1. Rheology experiments show that the storage modulus (G′) was an order of magnitude greater than the loss modulus (G″) and G′ and G″ have not crossed each other, which suggests for astable and elastic gel with the physical crosslink (Figure 3e). Strain sweeps show almost no change (Figures S9 and 10, ESI†). The TEM image depicts that highly dispersed Pd nanoparticles are supported on the α,γ-hybrid peptide 1 self- assembled fibers (Figure 3f). The Pd nanoparticles are on the surface of the fibers (Figure 3f, inset). EDX confirmed the presence of Pd (Figure S11, ESI†).

The concept of using the Pd nanoparticle-embedded peptide-based organic–inorganic hybrid gel as a catalyst for the C–C cross-coupling by contact with the aqueous phase arose in the milieu of the self-healing and dynamic nature of the gel.40 We proposed simple addition of reactants in water over the hybrid gel followed by mild shaking for 6 h (Figure 4a). On completion of the cross-coupling reactions, the aqueous layer above the gel can simply decant and the intact gel is reusable for multiple cycles (Figure 4a). We have opted for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling41−50 (Figure 4b) for this purpose. First Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction between 4-bromobenzoic acid and phenylboronic acid was performed to test the catalytic performance of the Pd-embedded peptide-based hybrid gel. The Suzuki–Miyaura reaction was accomplished using water as the solvent and base NaOH. Figure 4c exhibits the catalytic conversion by the Pd-embedded organic–inorganic hybrid gel with time at RT. Also, 88% conversion of 4-bromobenzoic acid was observed after 210 min. The catalytic performance provides further affirmation that the Pd nanoparticles are not completely fixed in the self-assembled peptide fibers. As the gel has self-healing properties and is dynamic in nature, the exposed active Pd on gel fibers catalyzes the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling. To probe the stability of the Pd-embedded organic–inorganic hybrid gel, a chain of recycling experiments for the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling of 4-bromobenzoic acid and phenylboronic acid were performed. As shown in Figure 4d, the catalytic activity of the Pd-embedded organic–inorganic hybrid gel is significant even after 5 cycles. Figure S12, ESI†, shows the proposed reaction pathway.1

Figure 4.

(a) Catalytic reaction. Decant: removal of the aqueous layer above the hybrid gel. Refill: addition of a fresh reactant in water over the hybrid gel; (b) Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction at RT; (c) 4-biphenylcarboxylic acid formation rate in the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling (λmax 265 nm); (d) recycling of the catalyst by decanting the aqueous reaction mixture and addition of fresh reactants in water.

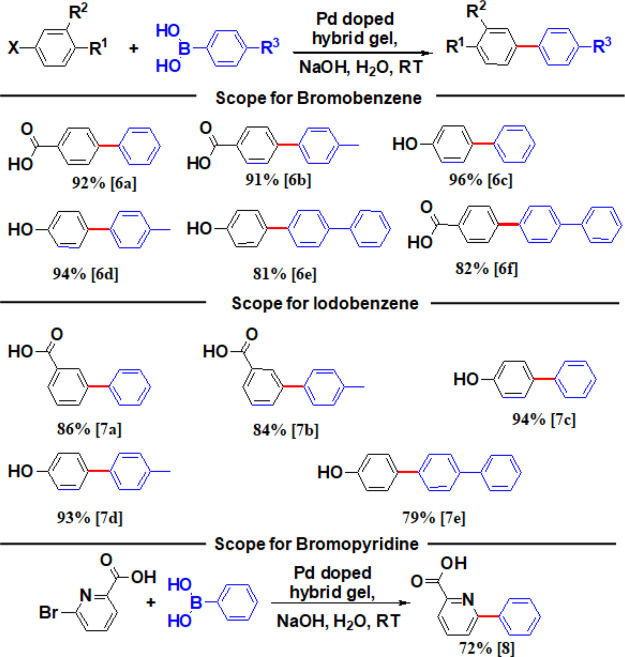

On completion of cross-coupling reactions, the products dissolved in the basic aqueous layer can be simply decanted and the intact gel is recyclable for multiple cycles. This biphasic method is efficient at RT, saves energy, and avoids tedious celite-sinter funnel-based Pd separation. We have performed the leaching test by ICP-MS and hot filtration techniques. The leaching test showed that Pd is in the solution. However, according to the hot filtration test, the solution of Pd is not able to catalyze the reaction. Hence, from this, we can conclude that Pd leaches as Pd(II), which is not an active catalyst for the reaction. For the ICP-MS test, we have used Pd in 10% HCl as a standard. The result shows that almost 6.67% Pd leaching happens after 3 cycles of reaction. With the optimized reaction conditions, we have tried to figure out the scopes of this reaction (Figure 5). The reaction permitted a range of different substitution patterns for aryl halides with acid or phenol functional groups. Both electron-donating- and electron-withdrawing-substituted aromatic, heteroaromatic, and heterocyclic halides were all good substrates for this transformation. Aryl halides with para-substitution exhibited good yields, but the meta-substitution yielded moderate yields (Figure 5). From Figure 5, it can be observed that the aryl bromide provided better yields than aryl iodide. Also, we have performed a summative comparison of studies of these different reactions and incorporated the results in Tables S6–S8.

Figure 5.

Substrate scope for Suzuki–Miyaura coupling reaction using the organic–inorganic hybrid gel at RT in water by mild shaking (0.1 mmol scale). For detailed reaction conditions, see Table S5. The isolated yield after chromatography is shown.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed an ecofriendly, efficient but simple method for the Pd-embedded organic–inorganic hybrid gel, which is catalytically active and recyclable for Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction at RT in water by mild shaking only. The organic–inorganic hybrid gel was characterized by rheology, FE-SEM, TEM, and EDX analyses. On completion of cross-coupling reactions, the products in the basic aqueous layer can be simply decanted and the intact gel is recyclable multiple times. This biphasic method is efficient at RT, is sustainable, saves energy, and avoids tedious celite-sinter funnel-based Pd separation. The reaction has a wide scope of different substitution patterns for aromatic and heteromatic halides with acid or phenol functional groups. In comparison with traditional Pd catalysis, this simple sustainable process does not use a large amount of organic solvents as well as energy and thus helps to reduce the carbon footprint and may be adoptable to produce life-saving drugs and commodity chemicals in the large scale.

Acknowledgments

S.R.C. and S.K.N. acknowledge the CSIR, India for research fellowship. The authors thank IISER-Kolkata for the instrumental facility. D.H. acknowledges support from CSIR, India (Grant No. 02(0404)/21/EMR-II).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.2c01360.

Synthesis and characterization of compounds, 1H NMR, 13C NMR, solid-state FTIR spectra, and Figures S1–S57 (PDF)

Author Contributions

S.R.C. has synthesized the compounds. S.K.N. has analyzed the compounds, and D.H. has written the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Rana S.; Biswas J. P.; Paul S.; Paik A.; Maiti D. Organic synthesis with the most abundant transition metal–iron: from rust to multitasking catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 243–472. 10.1039/D0CS00688B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaura N.; Yamada K.; Suzuki A. A new stereospecific cross-coupling by the palladium-catalyzed reaction of 1-alkenylboranes with 1-alkenyl or 1-alkynyl halides. Tetrahedron Lett. 1979, 20, 3437–3440. 10.1016/S0040-4039(01)95429-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miyaura N.; Suzuki A. Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Organoboron Compounds. Chem. Rev. 1995, 95, 2457–2483. 10.1021/cr00039a007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barder T. E.; Walker S. D.; Martinelli J. R.; Buchwald S. L. Catalysts for Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling Processes: Scope and Studies of the Effect of Ligand Structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 4685–4696. 10.1021/ja042491j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korch K. M.; Watson D. A. Cross-Coupling of Heteroatomic Electrophiles. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 8192–8228. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J.; Hu B.; Wu W.; Hu M.; Liu T. L. Nickel-Catalyzed Electrochemical C(sp3)–C(sp2) Cross-Coupling Reactions of Benzyl Trifluoroborate and Organic Halides. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60, 6107–6116. 10.1002/anie.202014244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooshmand S. E.; Heidari B.; Sedghi R.; Varma R. S. Recent advances in the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction using efficient catalysts in eco-friendly media. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 381–405. 10.1039/C8GC02860E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Das M. K.; Bobb J. A.; Ibrahim A. A.; Lin A.; AbouZeid K. M.; El-Shall M. S. Green Synthesis of Oxide-Supported Pd Nanocatalysts by Laser Methods for Room-Temperature Carbon–Carbon Cross-Coupling Reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 23844–23852. 10.1021/acsami.0c03331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinxterhuis E. B.; Giannerini M.; Hornillos V.; Feringa B. L. Fast, greener and scalable direct coupling of organolithium compounds with no additional solvents. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 11698. 10.1038/ncomms11698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke C. J.; Tu W. C.; Levers O.; Brohl A.; Hallet J. P. Green and Sustainable Solvents in Chemical Processes. Chem. Rev. 2018, 118, 747–800. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y. Multicomponent reactions in unconventional solvents: state of the art. Green Chem. 2012, 14, 2091–2128. 10.1039/C2GC35635J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nahra F.; Cazin C. S. J. Sustainability in Ru- and Pd-based catalytic systems using N-heterocyclic carbenes as ligands. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3094–3142. 10.1039/C8CS00836A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannalire R.; Pelliccia S.; Sancineto L.; Novellino E.; Tron G. C.; Giustiniano M. Visible light photocatalysis in the late-stage functionalization of pharmaceutically relevant compounds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 766–897. 10.1039/D0CS00493F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witham C. A.; Huang W.; Tsung C.-K.; Kuhn J. N.; Somorjai G. A.; Toste F. D. Converting homogeneous to heterogeneous in electrophilic catalysis using monodisperse metal nanoparticles. Nat. Chem. 2010, 2, 36–41. 10.1038/nchem.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykakis I. N.; Psyllaki A.; Stratakis M. Oxidative Cycloaddition of 1,1,3,3-Tetramethyldisiloxane to Alkynes Catalyzed by Supported Gold Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 10426–10429. 10.1021/ja2045502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astruc D.; Lu F.; Aranzaes J. R. Nanoparticles as Recyclable Catalysts: The Frontier between Homogeneous and Heterogeneous Catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 7852–7872. 10.1002/anie.200500766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornils B.; Kuntz E. G. Introducing TPPTS and related ligands for industrial biphasic processes. J. Organomet. Chem. 1995, 502, 177–186. 10.1016/0022-328X(95)05820-F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casalnuovo A. L.; Calabrese J. C. Palladium-Catalyzed Alkylations in Aqueous Media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 4324–4330. 10.1021/ja00167a032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorczyński A.; Harrowfield J. M.; Patroniak V.; Stefankiewicz A. R. Quaterpyridines as Scaffolds for Functional Metallosupramolecular Materials. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 14620–14674. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R.; Buchwald S. L. Palladium-Catalyzed Suzuki–Miyaura Cross-Coupling Reactions Employing Dialkylbiaryl Phosphine Ligand. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 1461–1473. 10.1021/ar800036s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stille J. K. The Palladium-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions of Organotin Reagents with Organic Electrophiles. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1986, 25, 508–524. 10.1002/anie.198605081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panja S.; Adams D. J. Stimuli responsive dynamic transformations in supramolecular gels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 5165–5200. 10.1039/D0CS01166E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okesola B. O.; Smith D. K. Applying low-molecular weight supramoleculargelators in an environmental setting – self-assembled gels as smart materials for pollutant removal. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 4226–4251. 10.1039/C6CS00124F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escuder B.; Rodríguez-Llansola F.; Miravet J. F. Supramolecular gels as active media for organic reactions and catalysis. New J. Chem. 2010, 34, 1044–1054. 10.1039/B9NJ00764D. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. D.; Steed J. W. Gels with sense: supramolecular materials that respond to heat, light and sound. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 6546–6596. 10.1039/C6CS00435K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y. B.; Conrad C. L.; Heck K. N.; Said I. A.; Powell C. D.; Guo S.; Reynolds M. A.; Wong M. S. Room-Temperature Catalytic Treatment of High-Salinity Produced Water at Neutral pH. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 10356–10363. 10.1021/acs.iecr.0c00521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Busch M.; Wodrich M. D.; Corminboeuf C. Linear scaling relationships and volcano plots in homogeneous catalysis – revisiting the Suzuki reaction. Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 6754–6761. 10.1039/c5sc02910d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowothnick H.; Blum J.; Schomäcker R. Suzuki Coupling Reactions in Three-Phase Microemulsions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 1918–1921. 10.1002/anie.201005263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár A. Efficient, Selective, and Recyclable Palladium Catalysts in Carbon–Carbon Coupling Reactions. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 2251–2320. 10.1021/cr100355b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar R.; Sasmal S.; Podder D.; Haldar D. Solvent Assisted Room Temperature Synthesis of Magnetically Retrievable and Reusable Dipeptide Stabilized Nanocrystals for Suzuki-Miyaura Cross-Coupling. Macromol. Symp. 2016, 369, 67–73. 10.1002/masy.201600061. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sasmal S.; Debnath M.; Nandi S. K.; Haldar D. A urea-modified tryptophan based in situ reducing and stabilizing agent for the fabrication of gold nanoparticles as a Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling catalyst in water. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 1380–1386. 10.1039/C8NA00273H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Zhang L.; Wang N.; Su D. S. Palladium nanoparticles embedded in the inner surfaces of carbon nanotubes: synthesis, catalytic activity, and sinter resistance. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 12634–12638. 10.1002/anie.201406490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng Y. L.; Newman S. G. Cross-coupling reactions with esters, aldehydes, and alcohols. Chem. Commun. 2021, 57, 2591–2604. 10.1039/D0CC08389E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan T.; Xu Y.; Fei J.; Xue H.; Li X.; Wang C.; Fytas G.; Li J. The Ultrafast Assembly of a Dipeptide Supramolecular Organogel and its Phase Transition from Gel to Crystal. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2019, 58, 11072–11077. 10.1002/anie.201903829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maity S.; Kumar P.; Haldar D. Sonication-induced instant amyloid-like fibril formation and organogelation by a tripeptide. Soft Matter 2011, 7, 5239–5245. 10.1039/C1SM05277B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moretto V.; Crisma M.; Bonora G. M.; Toniolo C.; Balaram H.; Balaram P. Comparison of the Effect of Five Guest Residues on the β-Sheet Conformation of Host (L-Val)n Oligopeptides. Macromolecules 1989, 22, 2939–2944. 10.1021/ma00197a010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Mynar J. L.; Yoshida M.; Lee E.; Lee M.; Okuro K.; Kinbara K.; Aida T. High-water-content mouldable hydrogels by mixing clay and a dendritic molecular binder. Nature 2010, 463, 339–343. 10.1038/nature08693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes-Caparrós A. M.; Canales-Galarza Z.; Barrow M.; Dietrich B.; Läuger J.; Nemeth M.; Draper E. R.; Adams D. J. Mechanical Characterization of Multilayered Hydrogels: A Rheological Study for 3D-Printed Systems. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 1625–1638. 10.1021/acs.biomac.1c00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidyasagar A.; Handore K.; Sureshan K. M. Soft Optical Devices from Self-Healing Gels Formed by Oil and Sugar-Based Organogelators. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2011, 50, 8021–8024. 10.1002/anie.201103584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz D. D.; Kühbeck D.; Koopmans R. J. Stimuli-responsive gels as reaction vessels and reusable catalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 427–448. 10.1039/C005401C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Li S.; Cao J.; Wang Y.; Yang W.; Zhang L.; Liu Y.; Qiu J.; Tao S. A Hierarchical-Structured Impeller with Engineered Pd Nanoparticles Catalyzing Suzuki Coupling Reactions for High-Purity Biphenyl. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 17429–17438. 10.1021/acsami.0c22284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei X.; Li Y.; Lu L.; Jiao H.; Gong W.; Zhang L. Highly Dispersed Pd Clusters Anchored on Nanoporous Cellulose Microspheres as a Highly Efficient Catalyst for the Suzuki Coupling Reaction. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 44418–44426. 10.1021/acsami.1c12850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K.; Liu J.; Zhang F.; Zhang Q.; Jiang H.; Tong M.; Xiao Y.; Phan N. T. S.; Zhang F. Primary Amine-Functionalized Mesoporous Phenolic Resin-Supported Palladium Nanoparticles as an Effective and Stable Catalyst for Water-Medium Suzuki–Miyaura Coupling Reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2019, 11, 41238–41244. 10.1021/acsami.9b11459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm T. H.; Bogdan A.; Hofmann C.; Löb P.; Shifrina Z. B.; Morgan D. G.; Bronstein L. M. Proof of Concept: Magnetic Fixation of Dendron-Functionalized Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Containing Palladium Nanoparticles for Continuous-Flow Suzuki Coupling Reactions. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2015, 7, 27254–27261. 10.1021/acsami.5b08466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fakhri P.; Nasrollahzadeh M.; Jaleh B. Graphene oxide supported Au nanoparticles as an efficient catalyst for reduction of nitro compounds and Suzuki–Miyaura coupling in water. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 48691–48697. 10.1039/C4RA06562J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baran T.; Nasrollahzadeh M. Facile synthesis of palladium nanoparticles immobilized on magnetic biodegradable microcapsules used as effective and recyclable catalyst in Suzuki-Miyaura reaction and p-nitrophenol reduction. Carbohydr. Polym. 2019, 222, 115029 10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazaei A.; Khazaei M.; Nasrollahzadeh M. Nano-Fe3O4@SiO2 supported Pd(0) as a magnetically recoverable nanocatalyst for Suzuki coupling reaction in the presence of waste eggshell as low-cost natural base. Tetrahedron 2017, 73, 5624–5633. 10.1016/j.tet.2017.05.054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohazzab B. F.; Jaleh B.; Issaabadi Z.; Nasrollahzadeh M.; Varma R. S. Stainless steel mesh-GO/Pd NPs: catalytic applications of Suzuki–Miyaura and Stille coupling reactions in eco-friendly media. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 3319–3327. 10.1039/C9GC00889F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M.; Bidgoli N. S. S.; Issaabadi Z.; Ghavamifar Z.; Baran T.; Luque R. Hibiscus Rosasinensis L. aqueous extract-assisted valorization of lignin: Preparation of magnetically reusable Pd NPs@Fe3O4-lignin for Cr(VI)reduction and Suzuki-Miyaura reaction in eco-friendly media. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 148, 265–275. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.01.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasrollahzadeh M.; Issaabadi Z.; Varma R. S. Magnetic Lignosulfonate-Supported Pd Complex: Renewable Resource-Derived Catalyst for Aqueous Suzuki–Miyaura Reaction. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 14234–14241. 10.1021/acsomega.9b01640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.