Summary

Chronic wounds infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) are characterized by disease progression and increased mortality. We reveal Pf, a bacteriophage produced by Pa that delays healing of chronically infected wounds in human subjects and animal models of disease. Interestingly, impairment of wound closure by Pf is independent of its effects on Pa pathogenesis. Rather, Pf impedes keratinocyte migration, which is essential for wound healing, through direct inhibition of CXCL1 signaling. In support of these findings, a prospective cohort study of 36 human patients with chronic Pa wound infections reveals that wounds infected with Pf-positive strains of Pa are more likely to progress in size compared with wounds infected with Pf-negative strains. Together, these data implicate Pf phage in the delayed wound healing associated with Pa infection through direct manipulation of mammalian cells. These findings suggest Pf may have potential as a biomarker and therapeutic target in chronic wounds.

Keywords: bacteriophage, wounds, microbiology, immunology, Pseudomonas, Pf, filamentous phage

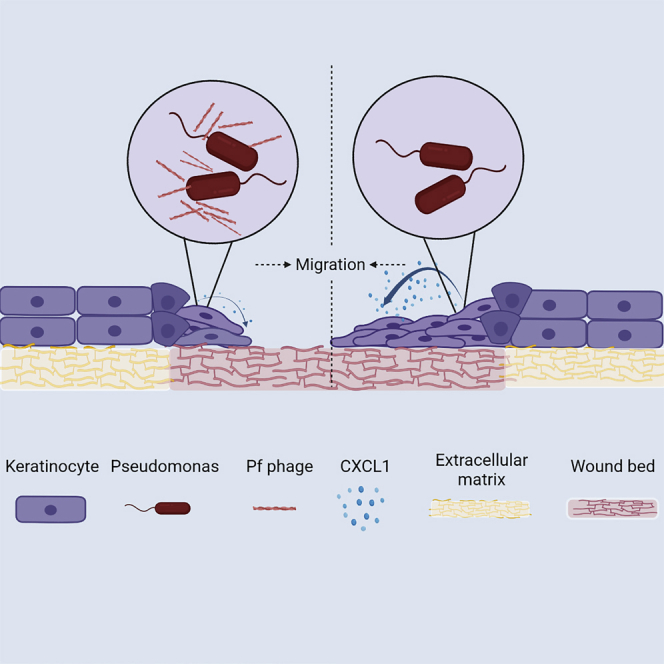

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Pf, a bacteriophage produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa, delays chronic wound healing

-

•

Pf impairs re-epithelization and barrier integrity in animal wound models

-

•

Pf inhibits keratinocyte signaling of CXCL1, contributing to impaired cell migration

-

•

Pf is associated with delayed healing in patients with chronic wound infections

Wounds chronically infected by P. aeruginosa are characterized by poor healing and progression of disease. Bach et al. report that Pf, a bacteriophage expressed by P. aeruginosa, impedes healing by directly inhibiting keratinocyte chemokine expression migration, resulting in impaired wound re-epithelization.

Introduction

Chronic wounds are associated with extensive human suffering and massive economic costs.1,2 Over 6.5 million Americans have chronic wounds, and their care is estimated to cost 25 billion dollars annually.2 Bacterial infections frequently complicate chronic wounds, leading to delayed wound healing,3 increased rates of amputation,4 and extensive morbidity and mortality.5, 6, 7

Wounds infected with the Gram-negative pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Pa) are characterized by poor outcomes.8, 9, 10, 11 Pa is prevalent in infections of burns,12 diabetic ulcers, and post-surgical sites.13 The presence of Pa is associated with delayed wound closure in both humans as well as animal models,3,14, 15, 16 and wounds infected with Pa tend to be larger than those in which Pa is not detected.17,18 This wound chronicity is associated with ineffective bacterial clearance19 and delayed healing.20 In addition to wound infections, Pa is a major human pathogen in other contexts14,19,21 due to increased antibiotic resistance incidence. In recognition of the magnitude of this problem, Pa is deemed a priority pathogen by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC).22 Therefore, there is great interest in identifying novel biomarkers, virulence factors, and therapeutic targets associated with Pa infections.

One such potential target is Pf bacteriophage (Pf phage), a filamentous virus produced by Pa.8,11,23 Unlike lytic bacteriophages used in phage therapy,24,25 Pf typically does not lyse its bacterial hosts. Instead, Pf phage integrates into the bacterial chromosome as prophage and can be produced without destroying their bacterial hosts.26,27 Indeed, the production of phage virions is partially under bacterial control.28 We and others have reported that Pf phages promote Pa fitness by serving as structural elements in Pa biofilms29,30 and contributing to bacterial phenotypes associated with chronic Pa infection, including bacterial aggregation31 and reduced motility.32

Pf phages also impact host immunity in ways that promote chronic infection. We recently reported that Pf phages directly alter cytokine production and decrease phagocytosis by macrophages.32,33 These effects were associated with Pf-triggering maladaptive anti-viral immune responses that antagonize anti-bacterial immunity. Consistent with these effects, Pa strains that produced Pf phage (Pf(+) strains) were more likely than strains that do not produce Pf (Pf(−) strains) to establish wound infections in mice.33 These and other studies implicate Pf phage as a virulence factor in Pa infections.29,34,35

We hypothesized that Pf phage might contribute to the delayed wound healing associated with Pa wound infections. To test this, we first examined the effects of Pf phage on wound healing and barrier function in an in vivo mouse and pig models. We then investigated the mechanism by which Pf phage inhibits wound healing in a well-established in vitro model (keratinocyte scratch assay). Finally, we examined the association between Pf phage and delayed wound healing in a cohort of 36 patients seen at the Stanford Advanced Wound Care Center.

Results

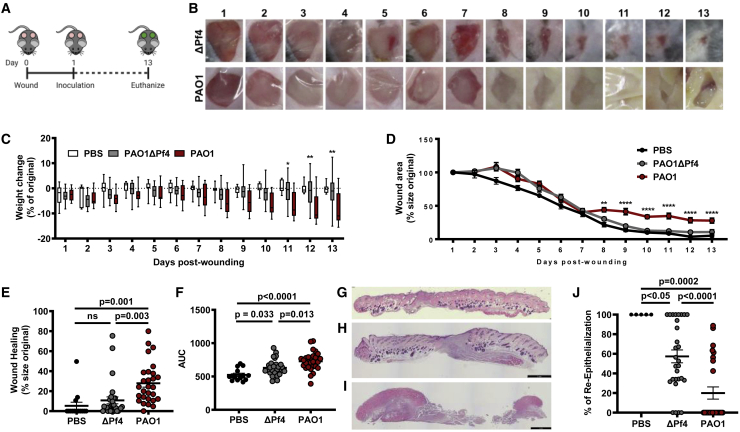

Infection with a Pf(+) strain of Pa causes worse morbidity in a murine chronic-wound infection model

We first examined the impact of a Pf(+) strain of Pa (PAO1) compared with a Pf(−) isogenic strain (PAO1ΔPf4) on morbidity and mortality in a delayed inoculation murine wound infection model. We previously pioneered this model to study the initial establishment of Pa wound infections in otherwise healthy C57BL/6 mice in the absence of foreign material, diabetes, or other forms of immune suppression.33,36 Here, we have adapted this model to study wound healing in the setting of infection over a 2-week time period. In brief, we generated bilateral, full-thickness, excisional wounds on the dorsum of mice. These wounds were then inoculated 24 h later with 4 × 105/mL PAO1, PAO1ΔPf4, or PBS as a control. We then assessed wound size daily through day 13 post-Pa inoculation (day 14 post-wounding). A schematic of this protocol is shown in Figure 1A.

Figure 1.

Pf phages lead to decreased wound healing in murine models

(A) Schematic of the full thickness delayed inoculation chronic Pa wound-infection murine model.

(B) Images of representative mice from PAOΔPf4 and PAO1groups from days 1 to 13 post-wounding.

(C) Weight loss of mice across all days post-wounding (for PAO1 versus PAO1ΔPf4, ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; two-way ANOVA).

(D) Wound healing rates for all wounds across all days from days 1 to 13 post-wounding. n = 28 wounds in PAOΔPf4 and PAO1groups; n = 14 wounds in PBS group. Results are mean % size of original wound ±SE (∗∗p < 0.005 and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA).

(E) Wound healing at day 13 post-wounding measured as percentage of original wound area.

(F) Area-under-curve (AUC) analysis for wound healing rates compiled for all wounds for all days 1–13 post-wounding (n = 28 wounds in PAOΔPf4 and PAO1 groups; n = 14 wounds in PBS group; comparison by one-way ANOVA).

(G) Representative H&E stain of day 13 uninfected PBS wound.

(H) Representative H&E stain of day 13 wound infected with PAO1ΔPf4.

(I) Representative H&E stain of day 13 wound infected with PAO1.

(J) Percent re-epithelialization calculated as ([day 1 epithelial gap−day 13 epithelial gap]/day 1 epithelial gap). Statistics are by one-way ANOVA.

All mice survived the 14-day experiment (Figure S1), and all wounds were infected on day 3 (Figure 1B), regardless of whether they received PAO1 or PAO1ΔPf4. However, by day 13, wounds in the PAO1 group remained inflamed and purulent. In contrast, PAO1ΔPf4 wounds were largely healed (Figure 1B). Moreover, mice inoculated with PAO1 lost significant weight compared with mice that received PAO1ΔPf4 or PBS (Figure 1C). These data confirm Pf phage contributes to worse morbidity in this chronic-wound model, consistent with prior studies showing Pf promotes Pa pathogenesis.23,33

Pf4 phages delay wound healing

We next examined the effect of Pf4, the phage present in PAO1, on wound healing in our in vivo model. Healing was defined as the remaining open wound area as a fraction of the original wound area. Inoculation with PAO1ΔPf4 led to significantly improved wound healing over time compared with infection with PAO1. Indeed, wound healing in many of the mice inoculated with PAO1 plateaued by day 7 (Figure 1D). By day 13, most of the mice from the PAO1ΔPf4 group resolved their infections and healed their wounds completely, whereas most wounds infected with PAO1 persisted (Figure 1E). Similar results were observed when area under the curve (AUC), a measure of cumulative change in wound area, was evaluated (Figure 1F). We then examined wound histology from tissue sections collected on day 13 post-wounding that were collected from these mice. We observed that uninfected wounds and wounds infected with PAO1ΔPf4 exhibited healthy granulation tissue (Figures 1G and 1H), whereas wounds infected with PAO1 had substantial necrotic debris, minimal granulation tissue, and obvious infection (Figure 1I). When the epithelial gap was measured, wounds infected with PAO1 were found to have significantly less re-epithelialization by day 13 compared with PAO1ΔPf4 (Figure 1J).

Taken together, these data indicate that the production of Pf4 phage by PAO1 is associated with increased morbidity, impaired wound healing, and delayed re-epithelialization in this model.

Pf4 phages delay re-epithelialization in the absence of bacterial infection

Because the aforementioned data were collected in the setting of infection, it is difficult to distinguish wound persistence is due to phage-enhanced Pa pathogenesis33 or from a direct inhibition on wound healing by Pf. To elaborate whether Pf directly impairs wound healing, we treated mice with purified Pf4 phage in the absence of bacterial infection. In particular, we administered heat-killed PAO1 (HK-Pa) or PBS to C57BL6 mice 1 day after wounding in the absence or presence of supplemental Pf4 phage. Day 7 rather than day 13 was used in the studies, as wounds healed more rapidly in the absence of live bacterial infections. In addition, wounds were splinted with a silicone ring to prevent healing via contraction, which otherwise happens in mice in the absence of infection.37 A schematic detailing this protocol is shown in Figure S2A. Both the wound area on day 1 (Figure S2B) and the epithelial gap on day 7 post-wounding (Figure S2C) were assessed morphometrically. Representative area demarcations are shown inset into these images.

We observed that supplementation with Pf4 phage is associated with a larger epithelial gap on day 7 when normalized to day 1 wound area (Figure S2D), consistent with direct inhibition of wound healing by Pf4. Further, overall inflammatory cell counts are not altered by Pf phage supplementation (Figures S2E–S2G). We conclude that Pf reduces re-epithelialization of murine wounds in the absence of infection. These studies indicate that Pf4 phage directly antagonizes wound healing.

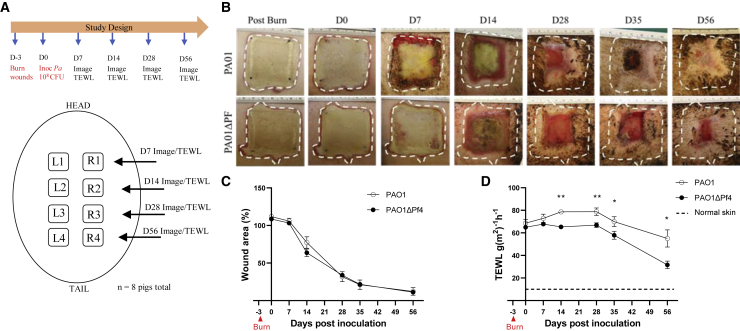

Pf phage inhibits re-epithelialization in a pig wound model

To better understand the impact of Pf4 phage on re-epithelialization, we next examined whether Pf phage alters healing in a porcine burn-wound model. Pig skin is anatomically and physiologically more similar to human skin, relative to rodents.38 Further, while mice largely rely on contraction for wound closure, both pigs and humans heal partial thickness wounds through re-epithelialization.38,39 As such, the porcine wound model has been suggested to more closely mimic human disease and serve as a preferred preclinical model.38,40 Here, eight domestic white pigs were wounded according to previously established protocols.41,42 Each pig received eight dorsal burn wounds, which were then inoculated 3 days later with PAO1 or PAO1ΔPf4 (Figure 2A). At indicated times, images were taken of wounds (Figure 2B) and tissue healing was assessed by digital planimetry (Figures 2B and 2C). In this model, Pf4 does not delay wound healing, as determined by morphometric measurement over time (Figure 2C). The limited inflammatory change noted in Pa-infected pig wounds (Figure 2B), relative to mice (Figure 1B), may account for these disparate results between these two animal-model systems. Further, visual wound area measurements do not account for functional wound healing, including re-establishing epithelial barrier integrity.43

Figure 2.

Pf is associated with increased trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) in pig burn wounds

(A) Schematic for porcine burn-wound model with inoculation of PAO1 or PAOΔPf4.

(B) Representative images of wounds infected with PAO1 or PAOΔPf4 at indicated times.

(C) Wound area as measured by digital planimetry over time. Each independent wound represents one n, with 32 wounds per time point per each treatment group.

(D) Wound area barrier integrity as measured by TEWL over time. Each independent wound represents one n for the experiment, with 6–28 wounds per time point per treatment group. Baseline measurements were done on healthy skin. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01 by unpaired Student’s t test.

While gross morphological differences in wound healing were not appreciated, burn wounds infected with PAO1 revealed decreased expression of keratin 14, a marker expressed in mitotically active basal epithelial cells and is associated with protection against mechanical stress (Figures S3A and S3B).44,45 Further, wounds infected with PAO1 demonstrated reduced keratinocyte proliferation compared with PAO1ΔPf4 (Figures S3C and S3D). These studies indicate that infection with Pf4 results in defects in wound healing and barrier integrity. To further assess skin barrier function following Pf4 infection, trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) studies were performed on wounds at indicated times (Figure 2A). TEWL is a validated, objective, and highly sensitive assessment of skin integrity and wound re-epithelization.41,42 While wounds infected with PAO1ΔPf4 recover barrier function over time and approach that of healthy skin, PAO1-infected wounds, despite apparent wound closure (Figures 2B and 2C), demonstrate persistent water vapor loss consistent with barrier dysfunction (Figure 2D). These studies reveal persistent barrier dysfunction in Pf4-infected wounds, indicating that Pf phage compromises wound re-epithelization.

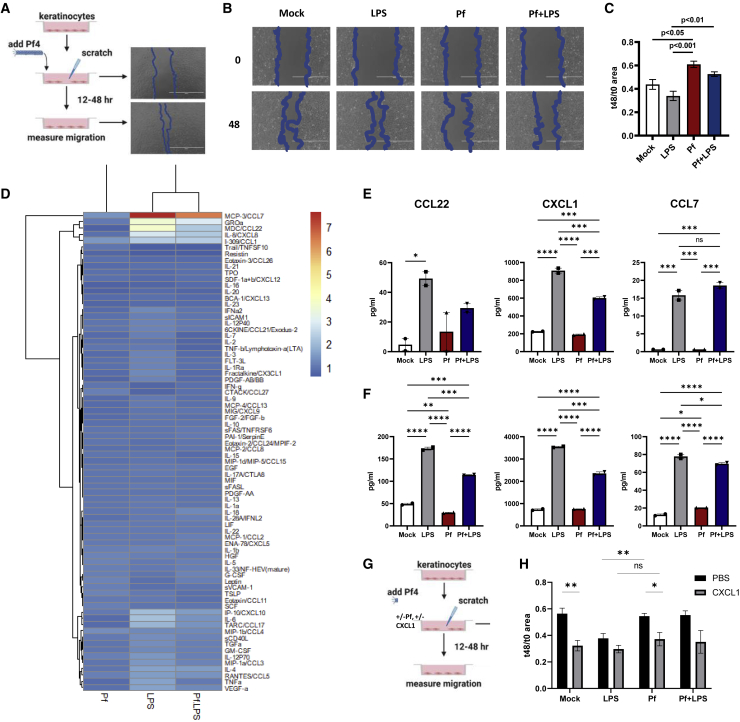

Pf4 phages impair in vitro keratinocyte migration

The TEWL studies reveal impaired barrier integrity in Pf4-infected wounds, consistent with defects in re-epithelization. Because re-epithelialization is mediated by keratinocytes, these findings suggest Pf4 may influence keratinocyte proliferation and/or migration. Direct stimulation of keratinocytes and fibroblasts with Pf4 does not alter cell viability or proliferation (Figure S4). We then assessed whether Pf4 inhibits keratinocytes cell migration in an in vitro model commonly used to study mechanisms related to wound healing.46 A schematic of this protocol is shown (Figure 3A). We demonstrate that treatment of HaCaT keratinocytes with purified Pf4 phage impairs cell migration relative to controls (Figures 3B and 3C). These effects were most pronounced in the setting of bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of the bacterial outer membrane that can be expected to be present wherever Pf phages are expressed by bacteria. These data suggest Pf4 phages directly antagonize keratinocyte migration in response to inflammatory signals associated with bacteria.

Figure 3.

Pf phage impedes keratinocyte migration

(A) Schematic of HaCaT keratinocyte-migration assays.

(B) Representative images of keratinocyte migration at 0 and 48 h following treatment with mock, Pf, LPS, or Pf + LPS.

(C) Effect of Pf (1 × 1010 copy no./mL) and LPS (1 μg/mL) on HaCaT keratinocyte migration, presented as area at 48 h/area at 0 h with decreased area correlating with increased cell migration. Three biological replicates per experiment are shown. Results are representative of three independent experiments. Statistics are by one-way ANOVA.

(D) Heatmaps from Luminex immunoassay performed on supernatant from HaCaT keratinocytes stimulated with Pf and LPS at 48 h. Results are presented as log 2-fold change of concentration compared with PBS control.

(E and F) Interpolated values (pg/mL) of select cytokines and growth factors from Luminex assay of human primary monocytes stimulated with Pf and LPS for 24 h (E) or 48 h (F) are shown. ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01, ∗∗∗p < 0.001, and ∗∗∗∗p < 0.0001 by one-way ANOVA. ns, not significant.

(G) Schematic of keratinocyte migration assays with pretreatment with CXCL1, Pf, and/or LPS.

(H) Effect of CXCL1 supplementation (1 μg/mL) on HaCaT keratinocyte migration, presented as area at 48 h/area at 0 h with decreased area correlating with increased cell migration. Three biological replicates per experiment are shown. Results are representative of three independent experiments. ∗p < 0.05 and ∗∗p < 0.01 by unpaired Student’s t test.

Our previous studies revealed that Pf4 phage suppresses production of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) and other cytokines made in response to LPS by macrophages and monocytes.32,33 To investigate whether Pf4 alters expression of cytokines and chemokines by keratinocytes, we performed a Luminex assay on HaCaT keratinocytes treated with Pf4 phage. While Pf4 does not alter expression of the majority of cytokines and chemokines tested, select inhibition was noted of CXCL1, CCL7, and CCL22, relative to LPS-treated cells (Figures 3D–3F). These data argue Pf4 actively suppresses keratinocyte-derived chemokine production during inflammatory challenge and may contribute to diminished keratinocyte migration and wound re-epithelization.

While CCL7 and CCL22 appear to primarily recruit monocytes and lymphocytes, CXCL1 has been described to promote keratinocyte migration.47 To determine whether Pf4-mediated CXCL1 inhibition impedes keratinocyte migration, CXCL1 or vehicle control was supplemented to keratinocytes in addition to Pf4, LPS, or mock treatment (Figure 3G). Exogenous CXCL1 did not confer additive effects to LPS treatment, which is consistent with elevated endogenous expression of this chemokine in this treatment group (Figure 3H). However, the addition of CXCL1 rescues keratinocyte migration among Pf4-treated cells (Figure 3H). Together, these data indicate that Pf4 phages directly target keratinocytes and inhibit chemokine expression during inflammatory stress to limit cell migration.

Pf phages are abundant in human wounds infected with Pa

In light of the decreased wound healing observed in the presence of Pf4 phage in our in vivo model, we investigated the clinical impact of Pf phage on human chronic Pa wound infections. A total of 113 patients referred to the infectious disease service at the Stanford Advanced Wound Care Center (AWCC) were enrolled from June 2016 to June 2018. Our protocol for screening and classifying these patients is described in Figure S5. Three Pa-positive patients (one who was Pf(+) and two who were Pf(−)) were excluded from the final analysis due to amputation, exposed bone or tendon, or loss to follow-up (Figure S5). Patient characteristics are described in Table S1, and microbiological qualities of the Pa-positive wound isolates are described in Table S2.

Of the Pa-positive patients included in our analysis, Pf prophage (integrated into the bacterial chromosome) was detected in 69% (25/36) of the wounds (Table S1). Pf phage levels ranged from 3.55 × 103 to 2.69 × 108 copies/swab, with a mean of 2.16 × 107 copies/swab in Pf(+) samples. Subjects in the Pf(−) subset were older compared with the Pf(+) subset (61.6 ± 14.7 versus 76.6 ± 14.5; p = 0.008; Table S1). Higher numbers of Pf(+) patients were on antimicrobial treatments compared with Pf(−) patients, though this was not statistically significant (Table S2). There were no significant correlations between Pf phage status and gender, BMI, recurrence of infection, race or ethnicity, co-morbidities, antimicrobial resistance, or co-infection with other bacterial or fungal species (Table S1). This excludes co-infection as a confounding variable. These data indicate that Pf phages are prevalent and highly abundant in chronic wounds in this cohort.

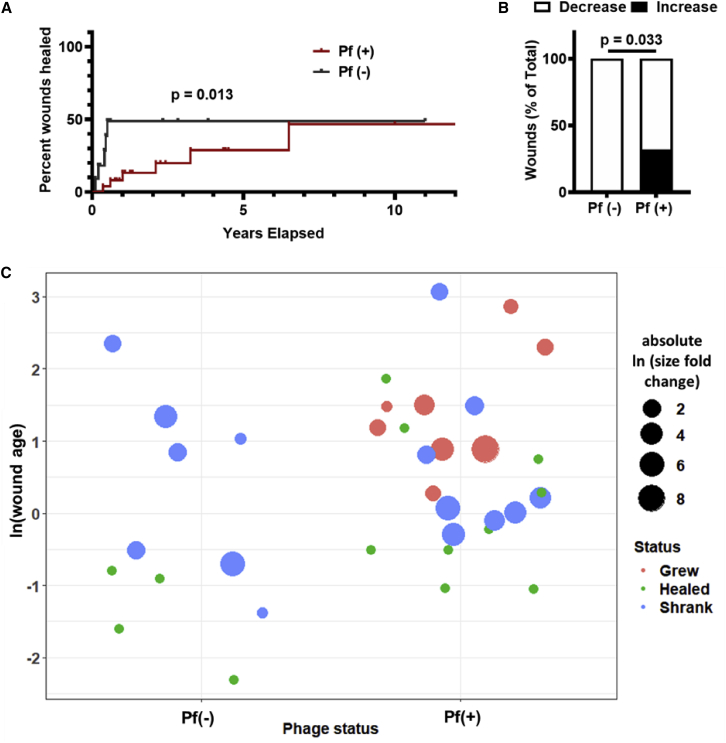

Pf phages are associated with wound progression

To test whether Pf phages inhibit wound healing, we followed this cohort over time for a period of 2 years. We had previously reported in a cross-sectional cohort study of these same patients that wounds infected with Pf(+) strains of Pa were significantly older at the time of enrollment than Pf(−) strains.33 We now asked in a prospective cohort study whether wounds infected with Pf(+) Pa strains versus Pf(−) Pa strains healed over time.

A survival analysis using the endpoint of wound closure showed a significant difference between time to wound closure of the Pf(+) wounds versus Pf(−) wounds (Figure 4A). We further measured changes in wound dimensions over time in the 36 Pa-positive patients, starting with measurements taken at the patient’s initial clinic visit. We found that Pf(+) patients were more likely to experience an increase in wound size over time than patients who were Pf(−) (8/25 versus 0/11, respectively) (Figures 4B and 4C). We observed that all wounds that grew in size over the study period were Pf(+) (Figure 4C). Together, these data indicate that Pf(+) strains of Pa are associated with delayed wound healing.

Figure 4.

Pf phage is associated with more chronic wound infections and increased wound size in humans

(A) Survival analysis of Pf(+) and Pf(−) Pa wound infections, with wound healing as endpoint. Wounds that were not healed by the end of the study were censored. p = 0.013 by Gehan-Breslow-Wilcoxon test.

(B) Pf(+) status is associated with increases in wound size. Pf(−): n = 11; Pf(+): n = 25; p = 0.033 by chi-square test.

(C) Plot showing wound age and change in size. Wounds were plotted based on Pf(−) or Pf(+) phage status and wound age (calculated as ln(wound age in years)). Wound size change is represented as absolute ln fold change, with color indicating whether wound grew (red), healed (green), or shrank (blue).

Discussion

We report that Pf phage impairs wound healing in mice, pigs, and humans. In mice, Pf phage delays healing in both the presence and absence of live Pa, indicative that effects on wound healing are independent of Pf influence on Pa pathogenesis. In pigs, wound infection with a Pf(+) strain of Pa resulted in impaired epithelial barrier integrity. Further, in a prospective cohort study in humans, Pf phage is associated with delayed wound healing and wound size progression. Together, these data strongly implicate Pf phage in delayed wound healing.

These effects of Pf phage on delayed healing are associated with altered keratinocyte chemokine expression and impaired re-epithelialization. In particular, keratinocyte secretion of CXCL1 secretion is inhibited by Pf4 in the setting of inflammatory stress. Re-epithelialization is critical for wound closure, and its failure leaves wounds vulnerable to reinjury, re-infection, and perpetuation.48, 49, 50 Our data are consistent with reports that Pa infections can cause impaired epithelialization,42 although this was not previously attributed to Pf phage.

These studies align well with but are distinct from our earlier reports on Pf phages promoting chronic infection. In those studies, we reported that Pf phage inhibits bacterial clearance through effects on phagocytosis and TNF production, contributing to the establishment of chronic wound infections.33 We likewise reported that Pf promotes chronic lung infections.34 The data presented here indicate that, in tandem with inhibiting anti-bacterial immunity, Pf phages also impair wound re-epithelialization.

This work reveals bacteriophages directly modulate mammalian cells to promote disease. We conclude that Pf phages may serve as a biomarker and therapeutic target for the delayed wound healing that occurs in the context of Pa wound infections. This finding may have particular relevance, given our recent report that a vaccine targeting Pf could prevent initial Pa wound infection.33 Future longitudinal studies in independent cohorts are needed to validate these studies.

Limitations of the study

Limitations of this work include that our prospective cohort study is small in size (36 patients). It will be important to validate these findings in larger, independent cohorts. It will also be important to validate these findings with Pf(+) and Pf(−) Pa clinical isolates, as currently, only lab strains were examined in our preclinical models. Further, our data demonstrating that Pf impairs keratinocyte migration via inhibition of chemokine signaling do not exclude alternative mechanisms by which Pf promotes chronic wounds. Such alternative mechanisms will include promoting formation of biofilms as well as potential steric hindrance of wound closure due to the anionic potential of Pf filaments.29 Finally, an important limitation of this study is the absence of a CXCL1 knockout in vivo wound model to further validate our findings that Pf inhibits CXCL1 expression to impair wound healing.

STAR★Methods

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| mouse monoclonal anti-k14 antibody | abcam | ab9220 |

| rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki67 antibody | abcam | ab16667 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | Obtained from collaborator Patrick Secor | NA |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human wounds | Stanford Advanced Wound Care Center | NA |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| RPMI | HyClone | Cat. No. SH30027.01 |

| DMEM | Hyclone | Cat. No. SH30243.01 |

| DNase I | Roche | Cat. No. 4716728001 |

| Benzonase | Novagen | Cat No. 70746 |

| RNAse A | Thermo Fisher Scientific | No. EN0531 |

| Betadine | Purdue Fredick Company | Cat. No. 19-065534 |

| Resazurin | Fisher | AC18990005 |

| buprenorphine | Zoopharm Pharmacy | na |

| LPS-EB Ultrapure from E. coli O111:B4 | Invitrogen | Cat: tlrl-3pelps |

| CXCL1 | Peprotech | Cat no 250-11 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| CytoTox | Promega | G1780 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| HaCaT human keratinocyte | AddexBio | Cat. No. T0020001 |

| hTERT Lung Fibroblast | ATCC | CRL-4058 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J | The Jackson Laboratory | 000664 |

| Domestic Yorkshire/landrace pigs | NA | NA |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| PAO717 F TTCCCGCGTGGAATGC | This paper | Na |

| PAO717 R CGGGAAGACAGCCACCAA | This paper | Na |

| PAO717 probe AACGCTGGGTCGAAG | This paper | Na |

| rpiU F CAAGGTCCGCATCATCAAGTT | This paper | Na |

| rpiU R GGCCCTGACGCTTCATGT | This paper | Na |

| rpiU probe CGCCGTCGTAAGC | This paper | Na |

| Pf4 F GGAAGCAGCGCGATGAA | This paper | Na |

| PF4 R GGAGCCAATCGCAAGCAA | This paper | Na |

| PF4 probe CAATTGCGCTGGTGAA | This paper | Na |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism | GraphPad Software | NA |

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Paul L. Bollyky (pbollyky@stanford.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique agents.

Experimental model and subject details

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 was used for all experiments. Isogenic phage-free strain PAO1ΔPf4 is derived from strain PAO1 with a complete knockout of Pf4 phage entirely (Rice et al., 2009). In general, bacteria were prepared as follows. Frozen glycerol stocks were streaked on Luria-Bertani (LB) agar and grown overnight at 37°C. An isolated colony was picked and grown overnight at 37°C in LB medium, pH 7.4 under shaking, aerobic conditions. The next day, cultures were diluted to OD600 = 0.05 in 75 mL LB media and cultures were grown until early exponential phase (OD600 ± 0.3). OD600 was measured and the required number of bacteria was calculated, washed, and prepared as described in the experiments.

Cell culture conditions

HaCaT human keratinocyte cell line (AddexBio, Cat. No. T0020001) was cultured in DMEM with 10% FBS, 100 IU penicillin, and 100 ug/mL streptomycin in T-75 flasks (Corning, Cat. No. 430641). All cells were cultured on sterile tissue culture- treated plates (Falcon). Cells were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2 at a 90% humidified atmosphere.

Animal studies

Mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen-free conditions, with free access to food and water, in the vivarium at Stanford University. Male mice between 10-12 weeks of age were used in this study. All mice used for in vivo infection experiments were littermates. Conventional C57BL/6J mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). All experiments and animal use procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care & Use Committee at the School of Medicine at Stanford University. Domestic Yorkshire/landrace cross pigs were purchased from Oak Hill genetics and housed in the vivarium at Indiana University with free access to food and water. Female pigs between 3-4 months of age and 70-80lb were used in wound studies. Before performing the experiment, the pigs are housed in compatible pairs or groups and left to acclimatize for at least 3 days. Pigs were housed individually after wounding to limit dressing and wound manipulation that may interfere with the healing process. To assure that the animals are socially housed, they are put together in the same room which will allow the visual and auditory contacts with the other pigs. All pig experiments were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (SoM-IACUC) under protocol 18048.

Collection of wound swabs from human patients

From 06/2016 to 06/2018, patients visiting the Stanford Advanced Wound Care Center (AWCC) in Redwood City, California with open wounds were swabbed in duplicate over a one square inch area using Levine’s technique, using nylon-flocked wet swabs (Copan Diagnostics, Cat. No. 23-600- 963). Swabs were collected in PBS and stored in −80°C before transport on dry ice. In the laboratory, the swabs in PBS were thawed, vortexed vigorously for 15 seconds, and the contents were aliquoted for quantitation of Pa rpIU gene and Pf prophage gene PAO717, as detailed below. Patients at the Wound Care Center were also swabbed for confirmation by diagnostic laboratory culture for the presence of Pa. Patients were subsequently followed until wounds completely healed or until August 2018. Patients were considered Pa-positive if their swabs had detectable Pa rpIU and their diagnostic cultures were positive. Patients were considered Pf phage-positive if both duplicate wound swabs had detectable levels of Pf phage genes. None of the Pa-negative patients had detectable Pf phage. For patients with multiple wounds, the dominant wound was selected for analysis. Patient enrollment and swab collection were done in compliance with the Stanford University Institutional Review Board for Human Research. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient before swab collection. Details regarding patient age, gender and ethnicity can be found in Table S1.

Human wound closure analysis

Length, width, and depth measurements of the wounds were taken and recorded into the patient’s flowsheet at the start of each visit by the intake nurse. Additional measurements of undermining and tunneling were also taken when applicable. Wound measurements were taken for all patients in the study each time they visited the Stanford Advanced Wound Care Center (AWCC). The AWCC nursing staff is trained in collecting and recording the longest length, width, and depth for each wound. Total volume was calculated for each wound for analysis. Wound healing was defined as a reduction in size compared to the first recorded measurement, whereas wound size increase was defined as an increase in wound volume compared to the first recorded measurement. Informed consent was obtained from patients before images were taken. Patient data was collected from electron medical records (EMR), including patient age, gender, co-morbidities, wound age, and other variables. This included history and physicals, progress notes, and documents uploaded into the EMR, such as the AWCC patient intake questionnaire. Patient flowsheet review was accessed for precise wound measurements and laboratory results were accessed to assess renal function and glycemic control. Microbiologic data were reviewed for antibiotic resistance profiles.

Method details

Materials and reagents

The following chemicals, antibiotics, and reagents were used: RPMI (HyClone, Cat. No. SH30027.01); DMEM (Hyclone, Cat. No. SH30243.01); PBS (Corning Cellgro, Cat. No. 21-040-CV); tryptone (Fluka Analytical, Cat. No. T7293); sodium chloride (Acros Organics, Cat. No. 7647-14-5); yeast extract (Boston BioProducts, Cat. No. P-950); agar (Fisher BioReagents, Cat. No. BP9744); gentamicin (Amresco, Cat. No. E737).

Preparation of heat-killed bacteria

Frozen glycerol stocks were streaked on LB agar as described above. Individual colonies were grown in 5 mL of LB broth the next day for 2 hours to approximately 2 × 108 CFU/mL. The bacterial cultures were centrifuged at 6,000 × g for 5 minutes, and the pellet was washed in 1 mL of PBS three times. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL of PBS and heated for 30 minutes at 90°C under shaking conditions. The preparation was checked for sterility by plating.

Phage purification

This was performed as previously reported (Sweere et al., 2019b). In brief, phages were purified by PEG precipitation only unless noted otherwise. Bacteria were infected with stocks of Pf4 phage at mid-log phase and cultured in 75 mL of LB broth for 48 hours at 37°C under shaking conditions. Bacteria were removed by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 5 minutes, and supernatant was treated with 1 μg/mL DNase I (Roche, Cat. No. 4716728001) for 2 hours at 37°C before sterilization by vacuum filtration through a 0.22 μM filter. In some experiments, supernatant was treated with 250 μg/mL of RNAse A (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Cat. No. EN0531) or 85 U/mL of benzonase (Novagen, Cat No. 70746) for 4 hours at 37°C before sterilization. Pf phage were precipitated from the supernatant by adding 0.5 M NaCl and 4% polyethylene glycol (PEG) 8000 (Milipore Sigma, Cat. No. P2139). Phage solutions were incubated overnight at 4°C. Phage were pelleted by centrifugation at 13,000 × g for 20 minutes, and the pellet suspended in sterile TE buffer (pH 8.0). The suspension was centrifuged for 15,000 × g for 20 minutes, and the supernatant was subjected to another round of PEG precipitation. The purified phage pellets were suspended in sterile PBS and dialyzed in 10- kDa molecular weight cut-off tubing (FisherScientific, Cat. No. 88243) against PBS, quantified by qPCR, diluted at least 10,000× to appropriate concentrations in sterile PBS and filter- sterilized. Three different Pf4 preparations diluted in PBS to working concentrations (1 × 108 Pf4/mL) were tested for endotoxin by Limulus amoebocyte lysate testing at Nelson Labs (Salt Lake City, UT). All three preps had endotoxin levels under the test sensitivity level of 0.05 EU/mL.

Quantification of Pf phage

As several factors can produce plaques on bacterial lawns (other species of phage, pyocins, host defensins, etc.), we quantitated Pf phage using a qPCR assay as previously described.29 In brief, to quantitate Pf prophage in human or mouse wound homogenates and purified Pf phage preparations, bacterial cells and debris were removed by centrifugation at 8,000× g for 10 min. Supernatants were boiled at 100°C for 20 min to denature any phage particles, releasing intact Pf phage DNA. 2 L was used as a template in 20 L qPCR reactions containing 10 L SensiFAST™ Probe Hi-ROX (Bioline, Cat. No. BIO-82020), 200 nM probe, and forward and reverse primers with concentrations depending on the target. Cycling conditions were as follows: 95°C 2 min, (95°C 15 sec., 60°C 20 sec.) x 40 cycles on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). For a standard curve, the sequence targeted by the primers and probe were inserted into a pUC57 plasmid (Genewiz) and tenfold serial dilutions of the plasmid were used in the qPCR reactions. For the human wound swabs, the primers and probe were designed to recognize PAO717, a gene conserved across the Pf phage family (F at 600 nM: TTCCCGCGTGGAATGC; R at 400 nM: CGGGAAGACAGCCACCAA; probe: AACGCTGGGTCGAAG); the Pa 50S ribosomal gene rpIU was used to confirm Pa infection (F at 200 nM: CAAGGTCCGCATCATCAAGTT; R at 200 nM: GGCCCTGACGCTTCATGT; probe: CGCCGTCGTAAGC). For the Pf4 phage purifications, the primers and probe were designed to recognize a Pf4 phage-specific intergenic region between PAO728 and PAO729 (F at 500 nM: GGAAGCAGCGCGATGAA; R at 500 nM: GGAGCCAATCGCAAGCAA; probe: CAATTGCGCTGGTGAA). For the Pf phage purification preparations, levels of Pa 50S ribosomal gene rpIU were measured to correct for contaminating genomic Pa DNA, but those levels were usually negligible.

In vivo murine full-thickness wound infection model

This was done as recently described (Sweere et al., 2019a; Sweere et al., 2019b). In brief, ten-to-twelve-week old male mice were anesthetized using 3% isoflurane, and their backs were shaved using a hair clipper and further depilated using hair removal cream (Nair). The shaved area was cleaned with sterile water and disinfected twice with Betadine (Purdue Fredick Company, Cat. No. 19-065534) and 70% ethanol. Mice received 0.1-0.5 mg/kg slow-release buprenorphine (Zoopharm Pharmacy) as an analgesic. Mice received two dorsal wounds by using 6-mm biopsy punches to outline the wound area, and the epidermal and dermal layer were excised using scissors. For certain experiments, as indicated in the text, a silicone ring was sutured in place around the wound. The wound area was washed with saline and covered with Tegaderm (3M, Cat. No. 1642W). Bacteria were grown as described above and diluted to 1 × 107 CFU/mL in PBS. Mice were inoculated with 40 μL per wound 24 hours post-wounding, and control mice were inoculated with sterile PBS. Mice were weighed daily and given Supplical Pet Gel (Henry Schein Animal Health, Cat. No. 029908) and intraperitoneal injections of sterile saline (Hospira, Cat. No. 0409-4888-10). Upon takedown, wound beds were excised and processed for histological analysis.

Murine wound healing analysis

This was done as previously described (Balaji et al., 2014). In brief, using a dot ruler for standardization, images of both wounds for all mice were taken on each day from Day 1 to Day 13 post-wounding. Images were taken using Canon PowerShot Camera (Item Model No. 1096C001) mounted on a fixed tripod for consistency in the height and angle at which images were taken. Using the images, wound area was measured using Fiji (Image J, National Institutes of Health)51 by tracing the border of the wounded area, as well as the border of a standardized dot measure. For histologic analyses, wounds were harvested, bifurcated, fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, and embedded in paraffin. Wound sections of 5 μm were cut from paraffin-embedded blocks. Immune cell influx, general tissue morphology, epithelial gap and granulation tissue area were measured from hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained sections using morphometric image analysis (Image-Pro, Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD, and Metamorph, Molecular Devices, Downingtown, PA). Images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse microscope, and image analysis was performed using the Nikon Elements software (Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY, USA). The percentage of CD45+ cells to the total cell infiltrate was calculated in 6 high-powered fields (HPFs, 64X) for each wound section. The HPFs were chosen just above the panniculus carnosus and were evenly distributed between the two wound epithelial margins. On a 4× edge-to-edge wound section image, epithelial gap was measured as the distance (in millimeters) between encroaching epithelial margins. The granulation tissue area was measured (in mm2) as the entire cellular region within the epithelial margin. Any sample that did not yield reliable counting due to sample quality was excluded from the analysis for that particular variable. All scoring was done by an independent pathologist.

Porcine full thickness burn wound model

Domestic Yorkshire/landrace cross female pigs 3-4 months of age (70-80lb) were wounded and infected to establish chronic wound biofilm model as described previously.41,42,52 Before performing the experiment, the pigs are housed in compatible pairs or groups and left to acclimatize for at least 3 days. Due to the nature of the experiment and study design, after burn wounding and bandaging the animals will be housed individually to prevent bandage and wound rubbing that will interfere with the healing process. Eight full thickness burn wounds (2 × 2 inch) were made on the dorsum of pigs. On day 3 post-burn, wounds were inoculated with either PAO1, or PAO1ΔPf4 strains (CFU108/mL). Wounds were followed up to 56 days post inoculation. Wounds were dressed with Tegaderm ™ (3M) which was kept in place with V.A.C. drape (Owens & Minor) and then wrapped with Vetrap™ and Elastikon™ (3M). Dressings were changed weekly for the duration of the study. Digital images and trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) was collected on day 0, day 7, day 14 and day 56 post inoculation. Biopsies were collected on days 7, 14, 28, and 56 post infection. The pigs were euthanized at day 56 post inoculation. Biopsies were collected using a 6 mm sterile disposable punch biopsy tool. Each independent porcine wound is considered as one n for the porcine wound experiments. A total of 8 pigs were used for this study. All pig experiments were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (SoM-IACUC) under protocol 18048.

Immunohistochemistry

Porcine wound tissues were collected at d56 post-wounding and immunostained with k14 and ki67 as previously described.53 Briefly paraffin-embedded tissues were cut into 8-μm thick sections. After deparaffinization and hydration, sodium citrate (pH 6.0) antigen retrieval was performed, and sections were blocked with 10% normal goat serum at room temperature, then incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-k14 antibody (ab9220; abcam; 1:400) or rabbit monoclonal anti-Ki67 antibody (ab16667, abcam, 1:200) overnight at 4°C. The specificity of the antibodies was validated using appropriate control. The signal was visualized by subsequent incubation with fluorescence-tagged secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 488–tagged α-mouse, or Alexa Fluor 488–tagged α-rabbit 1:200) and nuclei counter stained with DAPI. Imaging at ×20 was done using Axio Scan.Z1, Zeiss, Germany). K14 fluorescent intensity and ki67 positive cells were analyzed using Zen software (Zen blue 3.2).54

Trans-epidermal water loss (TEWL) measurement

DermaLab Combo™ (cyberDERM inc., Broomall, PA) was used to measure the trans-epidermal water loss from the wounds. TEWL was measured in g (m2)−1 h−1.42 Dermalab Combo consists of a main measuring unit with a computer and a probe. The TEWL probe has two hygro sensors located close to each other in a perpendicular orientation, TEWL is determined from the humidity gradient between the sensors. The probe is placed on the porcine skin/wound surface. The evaporated water released from the skin/wound is detected by the sensors in the probe and measured to provide the TEWL value.

Migration assay

For HaCaT cell migration assays a standard scratch assay was used.55 In brief, cells were seeded at a density of 1x106 cells per well in DMEM 10% FBS in collagen-coated 6-well tissue culture plates. Media was removed and HaCaT cells were then serum starved in DMEM containing only 2% FBS for 24 hours prior to the treatment. A scratch defect was created in the cell monolayer along the diameter in each group using a sterile pipette tip (200 μL tip). Treatment groups included Pf4 bacteriophage with final concentration of 1 × 1010 copy #/mL and/or LPS 1 ug/ml (LPS-EB Ultrapure from E. coli O111:B4 purchased from Invitrogen, Cat: tlrl-3pelps). For supplementation studies, HaCaT cells were treated with CXCL1 (Peprotech, Cat no 250-11) at a final concentration of 1ug/ml in addition to Pf4 or LPS described as above. Photographic images were obtained at 0 and 24-48 hours incubation using an Invitrogen EVOS FL Imaging System. The unfilled scratch defect area was measured at each reference point per well. Data was presented as extent of wound closure, that is, the percentage by which the scratch area has decreased at a given time point for each treatment as compared to the original defect (at 0 hours). All experiments were carried out at minimum in triplicate and the passage number was similar amongst the different groups.

Lactate dehydrogenase and resazurin assays

HaCaT human keratinocyte and hTERT Lung Fibroblast (ATCC CRL-4058) cell lines were seeded at a density of 1x104 cells per well in 96-well tissue culture plates, 24 hours prior to treatment. Cells were treated with Pf4 bacteriophage or LPS with final concentrations ranging from 1 x 108 PFU/mL to 1 x 1011 PFU/mL or 1 ng/mL to 1ug/ml, respectively, for 24 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2. LPS-EB Ultrapure from E. coli O111:B4 was purchased from Invitrogen (Cat: tlrl-3pelps). All experiments were performed in triplicates.

Cytotoxicity, as measured by lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release, was determined from cell-free supernatants using the CytoTox kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Promega, G1780). Percent Cytotoxicity was calculated as follows:

The proliferation of HaCaT and hTERT lung fibroblast cells was determined using the resazurin assay. Resazurin (Fisher Sci, AC18990005) was added to the cells 24 hours after Pf4 or LPS treatment and incubated for ∼1 hour at 37°C and 5% CO2 before fluorescence measurement. The oxidized non-fluorescent blue resazurin reduces to a red fluorescent dye (resorufin) by the mitochondrial respiratory chain in live cells. The number of living cells is directly proportional to the amount of resorufin produced. A microplate reader was used to determine resorufin fluorescence (Excitation: 551nm, Emission: 596nm).

Luminex immunoassay

HaCaT cells were seeded at 1x106 cells per well in DMEM 10% FBS in collagen-coated 6-well tissue culture plates. Media was removed and HaCaT cells were then serum starved in DMEM containing only 2% FBS for 24 hours prior to the treatment. Cells were treated with Pf4 (1x1010 copies/ml) and/or LPS (1 μg/mL). Supernatant was collected at 24 and 48hrs and used for cytokine profiling through Luminex (The Human Immune Monitoring Center, Stanford). Human 63-plex kits were purchased from eBiosciences/Affymetrix and used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations with modifications as described below. Briefly: Beads were added to a 96 well plate and washed in a Biotek ELx405 washer. Samples were added to the plate containing the mixed antibody-linked beads and incubated at room temperature for 1 hour followed by overnight incubation at 4°C on an orbital shaker at 500-600 rpm. Following the overnight incubation plates were washed in a Biotek ELx405 washer and then biotinylated detection antibody added for 75 minutes at room temperature with shaking. Plate was washed as above and streptavidin-PE was added. After incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature wash was performed as above and reading buffer was added to the wells. Each sample was measured in duplicate. Plates were read using a Luminex 200 instrument with a lower bound of 50 beads per sample per cytokine. Custom assay Control beads by Radix Biosolutions are added to all wells.

Quantification and statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were done using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc. La Jolla, CA). All Unpaired T-Tests, Mann-Whitney Test, Fisher’s Exact Tests, and Chi-Square Test were two-tailed. Depicted are Means with Standard Error or Standard Deviation of the population unless otherwise stated. Statistical significance was considered p<0.05. Statistical details are included in figure legends.

Acknowledgments

M.S.B. was supported by the Stanford Bio-X Fellowship. C.R.d.V. was supported by grant T32 AI007502, Doris Duke Physician Scientist Fellowship, and K08AI151089. A.K. was supported by grant T32 AI007502. J.M.S. was supported by the Gabilan Stanford Graduate Fellowship for Science and Engineering and the Lubert Stryer Bio-X Stanford Interdisciplinary Graduate Fellowship. M.H. was supported by funding from NIH grant 1K99EB028838-01A1. P.L.B. was supported by grants R21AI133370, R21AI133240, and R01AI12492093, and grants from Stanford SPARK, the Falk Medical Research Trust, and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation (CFF).

Author contributions

M.S.B. and C.R.d.V. contributed to the study design, conducted experiments, acquired and analyzed data, and prepared the manuscript. A.K. conducted experiments, acquired and analyzed data, and revised the manuscript. J.M.S. and M.C.P. provided methods and assisted in conducting experiments, data analysis, and manuscript revisions. Q.C., S.D., J.D.V.B., M.H., D.L., Q.-L.T., T.D., M.B., V.S., S.B., and S.G.K. conducted experiments and analyzed data. A.H. isolated Pf phage. E.B.B. and G.K. provided methods and assisted in data analysis. N.B. assisted with analysis of wound samples. N.G., S.S.M.-S., M.S.E.M., and C.K.S. assisted with animal studies, imaging, and data analysis. V.C. assisted with collection and analysis of human wound samples. L.N. assisted with statistical analysis. P.R.S., G.A.S., and P.L.B. provided oversight in study design, conducting experiments, data analysis, and manuscript revision.

Declaration of interests

G.A.S. received grants and has an equity and royalty-bearing know-how agreement with Adaptive Phage Therapeutics (APT) and is a principal investigator for clinical trials with APT and Phagelux. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Published: June 21, 2022

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100656.

Supplemental information

Data and code availability

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

References

- 1.Järbrink K., Ni G., Sönnergren H., Schmidtchen A., Pang C., Bajpai R., Car J. Prevalence and incidence of chronic wounds and related complications: a protocol for a systematic review. Syst. Rev. 2016;5:152. doi: 10.1186/s13643-016-0329-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirsner R.S. The wound healing society chronic wound ulcer healing guidelines update of the 2006 guidelines - blending old with new. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24:110–111. doi: 10.1111/wrr.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo S., DiPietro L.A. Factors affecting wound healing. J. Dent. Res. 2010;89:219–229. doi: 10.1177/0022034509359125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gardner S.E., Frantz R.A. Wound bioburden and infection-related complications in diabetic foot ulcers. Biol. Res. Nurs. 2008;10:44–53. doi: 10.1177/1099800408319056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowler P.G. Wound pathophysiology, infection and therapeutic options. Ann. Med. 2002;34:419–427. doi: 10.1080/078538902321012360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clinton A., Carter T. Chronic wound biofilms: pathogenesis and potential therapies. Lab. Med. 2015;46:277–284. doi: 10.1309/lmbnswkui4jpn7so. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scali C., Kunimoto B. An update on chronic wounds and the role of biofilms. J. Cutan. Med. Surg. 2013;17:371–376. doi: 10.2310/7750.2013.12129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowd S.E., Sun Y., Secor P.R., Rhoads D.D., Wolcott B.M., James G.A., Wolcott R.D. Survey of bacterial diversity in chronic wounds using Pyrosequencing, DGGE, and full ribosome shotgun sequencing. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:43. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.James G.A., Swogger E., Wolcott R., deLancey P.E., Secor P., Sestrich J., Costerton J.W., Stewart P.S. Biofilms in chronic wounds. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475x.2007.00321.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirketerp-Møller K., Jensen P.Ø., Fazli M., Madsen K.G., Pedersen J., Moser C., Tolker-Nielsen T., Hoiby N., Givskov M., Bjarnsholt T. Distribution, organization, and ecology of bacteria in chronic wounds. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008;46:2717–2722. doi: 10.1128/jcm.00501-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malic S., Hill K.E., Hayes A., Percival S.L., Thomas D.W., Williams D.W. Detection and identification of specific bacteria in wound biofilms using peptide nucleic acid fluorescent in situ hybridization (PNA FISH) Microbiol. Read Engl. 2009;155:2603–2611. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.028712-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tredget E.E., Shankowsky H.A., Rennie R., Burrell R.E., Logsetty S. Pseudomonas infections in the thermally injured patient. Burns J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj. 2004;30:3–26. doi: 10.1016/j.burns.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Percival S.L., Suleman L., Vuotto C., Donelli G. Healthcare-associated infections, medical devices and biofilms: risk, tolerance and control. J. Med. Microbiol. 2015;64:323–334. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bryers J.D. Medical biofilms. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008;100:1–18. doi: 10.1002/bit.21838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watters C., DeLeon K., Trivedi U., Griswold J.A., Lyte M., Hampel K.J., Wargo M.J., Rumbaugh K.P. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms perturb wound resolution and antibiotic tolerance in diabetic mice. Med. Microbiol. Immunol. 2013;202:131–141. doi: 10.1007/s00430-012-0277-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao G., Usui M.L., Underwood R.A., Singh P.K., James G.A., Stewart P.S., Fleckman P., Olerud J.E. Time course study of delayed wound healing in a biofilm-challenged diabetic mouse model. Wound Repair Regen. 2012;20:342–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475x.2012.00793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gjødsbøl K., Christensen J.J., Karlsmark T., Jørgensen B., Klein B.M., Krogfelt K.A. Multiple bacterial species reside in chronic wounds: a longitudinal study. Int. Wound J. 2006;3:225–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481x.2006.00159.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jesaitis A.J., Franklin M.J., Berglund D., Sasaki M., Lord C.I., Bleazard J.B., Duffy J.E., Beyenal H., Lewandowski Z. Compromised host defense on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms: characterization of neutrophil and biofilm interactions. J. Immunol. 2003;171:4329–4339. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.8.4329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sen C.K., Gordillo G.M., Roy S., Kirsner R., Lambert L., Hunt T.K., Gottrup F., Gurtner G.C., Longaker M.T. Human skin wounds: a major and snowballing threat to public health and the economy. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17:763–771. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475x.2009.00543.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bjarnsholt T., Kirketerp-Møller K., Jensen P.Ø., Madsen K.G., Phipps R., Krogfelt K., Hoiby N., Givskov M. Why chronic wounds will not heal: a novel hypothesis. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:2–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475x.2007.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Høiby N., Ciofu O., Johansen H.K., Song Z j, Moser C., Jensen P.Ø., Molin S., Givskov M., Tolker-Nielsen T., Bjarnsholt T. The clinical impact of bacterial biofilms. Int. J. Oral Sci. 2011;3:55–65. doi: 10.4248/IJOS11026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tacconelli E., Carrara E., Savoldi A., Harbarth S., Mendelson M., Monnet D.L., Pulcini C., Kahlmeter G., Kluytmans J., Carmeli Y., et al. Discovery, research, and development of new antibiotics: the WHO priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and tuberculosis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2018;18:318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Secor P.R., Burgener E.B., Kinnersley M., Jennings L.K., Roman-Cruz V., Popescu M., Van Belleghem J.D., Haddock N., Copeland C., Michaels L.A., et al. Pf bacteriophage and their impact on Pseudomonas virulence, mammalian immunity, and chronic infections. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:244. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gordillo Altamirano F.L., Barr J.J. Phage therapy in the postantibiotic era. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2019;32:e00066-18. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00066-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Górski A., Międzybrodzki R., Węgrzyn G., Jończyk-Matysiak E., Borysowski J., Weber-Dąbrowska B. Phage therapy: current status and perspectives. Med. Res. Rev. 2020;40:459–463. doi: 10.1002/med.21593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rakonjac J., Bennett N.J., Spagnuolo J., Gagic D., Russel M. Filamentous bacteriophage: biology, phage display and nanotechnology applications. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2011;13:51–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roux S., Krupovic M., Daly R.A., Borges A.L., Nayfach S., Schulz F., Sharrar A., Matheus Carnevali P.B., Cheng J.F., Ivanova N.N., et al. Cryptic inoviruses revealed as pervasive in bacteria and archaea across Earth’s biomes. Nat. Microbiol. 2019;4:1895–1906. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0510-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castang S., Dove S.L. Basis for the essentiality of H-NS family members in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:5101–5109. doi: 10.1128/jb.00932-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Secor P.R., Sweere J.M., Michaels L.A., Malkovskiy A.V., Lazzareschi D., Katznelson E., Rajadas J., Birnbaum M., Arrigoni A., Braun K., et al. Filamentous bacteriophage promote biofilm assembly and function. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;18:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tarafder A.K., von Kügelgen A., Mellul A.J., Schulze U., Aarts D.G.A.L., Bharat T.A.M. Phage liquid crystalline droplets form occlusive sheaths that encapsulate and protect infectious rod-shaped bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2020;117:4724–4731. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917726117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Secor P.R., Michaels L.A., Ratjen A., Jennings L.K., Singh P.K. Entropically driven aggregation of bacteria by host polymers promotes antibiotic tolerance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2018;115:10780–10785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1806005115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Secor P.R., Michaels L.A., Smigiel K.S., Rohani M.G., Jennings L.K., Hisert K.B., Arrigoni A., Braun K.R., Birkland T.P., Lai Y., et al. Filamentous bacteriophage produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa alters the inflammatory response and promotes noninvasive infection in vivo. Infect. Immun. 2017;85 doi: 10.1128/iai.00648-16. e00648-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sweere J.M., Van Belleghem J.D., Ishak H., Bach M.S., Popescu M., Sunkari V., Kaber G., Manasherob R., Suh G.A., Cao X., et al. Bacteriophage trigger antiviral immunity and prevent clearance of bacterial infection. Science. 2019;363:eaat9691. doi: 10.1126/science.aat9691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Burgener E.B., Sweere J.M., Bach M.S., Secor P.R., Haddock N., Jennings L.K., Marvig R.L., Johansen H.K., Rossi E., Cao X., et al. Filamentous bacteriophages are associated with chronic Pseudomonas lung infections and antibiotic resistance in cystic fibrosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 2019;11:eaau9748. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aau9748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rice S.A., Tan C.H., Mikkelsen P.J., Kung V., Woo J., Tay M., Hauser A., McDougald D., Webb J.S., Kjelleberg S. The biofilm life cycle and virulence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa are dependent on a filamentous prophage. ISME J. 2009;3:271–282. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Vries C.R., Sweere J.M., Ishak H., Sunkari V., Bach M.S., Liu D., Manasherob R., Bollyky P.L. A delayed inoculation model of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa wound infection. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE. 2020 doi: 10.3791/60599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X., Ge J., Tredget E.E., Wu Y. The mouse excisional wound splinting model, including applications for stem cell transplantation. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:302–309. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan T.P., Eaglstein W.H., Davis S.C., Mertz P. The pig as a model for human wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2001;9:66–76. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-475x.2001.00066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grillo H.C., Watts G.T., Gross J. Studies in wound healing: I. Contraction and the wound contents. Ann. Surg. 1958;148:145–152. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195808000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gordillo G.M., Bernatchez S.F., Diegelmann R., Di Pietro L.A., Eriksson E., Hinz B., Hopf H.W., Kirsner R., Liu P., Parnell L.K., et al. Preclinical models of wound healing: is man the model? Proceedings of the wound healing society symposium. Adv. Wound Care. 2013;2:1–4. doi: 10.1089/wound.2012.0367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Barki K.G., Das A., Dixith S., Ghatak P.D., Mathew-Steiner S., Schwab E., Khanna S., Wozniak D.J., Roy S., Sen C.K. Electric field based dressing disrupts mixed-species bacterial biofilm infection and restores functional wound healing. Ann. Surg. 2019;269:756–766. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000002504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roy S., Elgharably H., Sinha M., Ganesh K., Chaney S., Mann E., Miller C., Khanna S., Bergdall V.K., Powell H.M., et al. Mixed-species biofilm compromises wound healing by disrupting epidermal barrier function. J. Pathol. 2014;233:331–343. doi: 10.1002/path.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wikramanayake T.C., Stojadinovic O., Tomic-Canic M. Epidermal differentiation in barrier maintenance and wound healing. Adv. Wound Care. 2014;3:272–280. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alam H., Sehgal L., Kundu S.T., Dalal S.N., Vaidya M.M. Novel function of keratins 5 and 14 in proliferation and differentiation of stratified epithelial cells. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2011;22:4068–4078. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e10-08-0703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rugg E.L., McLean W.H., Lane E.B., Pitera R., McMillan J.R., Dopping-Hepenstal P.J., Navsaria H.A., Leigh I.M., Eady R.A. A functional ‘knockout’ of human keratin 14. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2563–2573. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.21.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang C.-C., Park A.Y., Guan J.-L. In vitro scratch assay: a convenient and inexpensive method for analysis of cell migration in vitro. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:329–333. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kroeze K.L., Boink M.A., Sampat-Sardjoepersad S.C., Waaijman T., Scheper R.J., Gibbs S. Autocrine regulation of re-epithelialization after wounding by chemokine receptors CCR1, CCR10, CXCR1, CXCR2, and CXCR3. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2012;132:216–225. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barrientos S., Stojadinovic O., Golinko M.S., Brem H., Tomic-Canic M. Perspective article: growth factors and cytokines in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16:585–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475x.2008.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pastar I., Stojadinovic O., Yin N.C., Ramirez H., Nusbaum A.G., Sawaya A., Patel S.B., Khalid L., Isseroff R.R., Tomic-Canic M. Epithelialization in wound healing: a comprehensive review. Adv. Wound Care. 2014;3:445–464. doi: 10.1089/wound.2013.0473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Raja R., Sivamani K., Garcia M.S., Isseroff R.R. Wound re-epithelialization: modulating kerationcyte migration in wound healing. Front. Biosci. J. Virtual Libr. 2007;12:2849–2868. doi: 10.2741/2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schindelin J., Arganda-Carreras I., Frise E., Kaynig V., Longair M., Pietzsch T., Preibisch S., Rueden C., Saalfeld S., Schmid B., et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roy S., Santra S., Das A., Dixith S., Sinha M., Ghatak S., Ghosh N., Banerjee P., Khanna S., Mathew-Steiner S., et al. Staphylococcus aureus biofilm infection compromises wound healing by causing deficiencies in granulation tissue collagen. Ann. Surg. 2020;271:1174–1185. doi: 10.1097/sla.0000000000003053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.El Masry M.S., Chaffee S., Das Ghatak P., Mathew-Steiner S.S., Das A., Higuita-Castro N., Roy S., Anani R.A., Sen C.K. Stabilized collagen matrix dressing improves wound macrophage function and epithelialization. FASEB J. 2019;33:2144–2155. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800352r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhou X., Brown B.A., Siegel A.P., El Masry M.S., Zeng X., Song W., Das A., Khandelwal P., Clark A., Singh K., et al. Exosome-mediated crosstalk between keratinocytes and macrophages in cutaneous wound healing. ACS Nano. 2020;14:12732–12748. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.0c03064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cory G. Scratch-wound assay. Methods Mol. Biol. Clifton NJ. 2011;769:25–30. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-207-6_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

This paper does not report original code.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.