Abstract

Salmonellae have been some of the most frequently reported etiological agents in fresh-produce-associated outbreaks of human infections in recent years. PCR assays using four innovative pairs of primers derived from hilA and sirA, positive regulators of Salmonella invasive genes, were developed to identify Salmonella enterica serotype Montevideo on and in tomatoes. Based on examination of 83 Salmonella strains and 22 non-Salmonella strains, we concluded that a pair of hilA primers detects Salmonella specifically. The detection limits of the PCR assay were 101 and 100 CFU/ml after enrichment at 37°C for 6 and 9 h, respectively. When the assay was validated by detecting S. enterica serotype Montevideo in and on artificially inoculated tomatoes, 102 and 101 CFU/g were detected, respectively, after enrichment for 6 h at 37°C. Our results suggest that the hilA-based PCR assay is sensitive and specific, and can be used for rapid detection of Salmonellae in or on fresh produce.

Salmonellae are some of the most prevalent food-borne pathogens in United States. They are estimated to cause approximately 1.5 million cases of infection, 15,000 hospitalizations, and 500 deaths annually (25). Historically, salmonellosis has most often been associated with consumption of contaminated foods of animal origin, such as poultry, eggs, meat, and dairy products. Changes in agronomic practices and dietary habits and increased importation of fresh produce are thought to contribute to the increased numbers of outbreaks associated with fruits and vegetables in recent years (3). Outbreaks of salmonellosis have been linked to tomatoes (12; R. C. Wood, C. Hedberg, and K. White, Abstr. Epidemic Intelligence Service 40th Annu. Conf., p. 69, 1991), seed sprouts (23, 28; C. A. Van Beneden, W. E. Keene, D. H. Werker, A. S. King, P. R. Cieslak, K. Hedberg, R. A. Strang, A. Bell, and D. Fleming, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. K47, p. 259, 1996), watermelons (8, 10, 16), cantaloupes (11; A. A. Ries, S. Zaza, C. Langkop, R. V. Tauxe, and P. A. Blake, Program Abstr. 30th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. 915, p. 238, 1990), orange juice (K. Cook, D. Swerdlow, T. Dobbs, J. Wells, N. Puhr, G. Hlady, C. Genese, L. Finelli, B. Toth, D. Bodager, K. Pilot, and P. Griffin, Abstr. 36th Intersci. Conf. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother., abstr. K49, p. 259, 1996), and apple cider (9).

Consumption of fresh tomatoes was epidemiologically linked to 176 cases of Salmonella javiana infection in Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, and Wisconsin in 1990 (Wood et al., Abstr. Epidemic Intelligence Service 40th Annu. Conf.). In 1993, tomatoes were identified as the vehicle for a multistate outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype Montevideo infection (12). Zhuang et al. (32) described conditions that influence survival and growth of S. enterica serotype Montevideo on the surfaces of intact tomatoes. Rapid growth occurred in chopped ripe tomatoes (pH 4.1 ± 0.1) at the ambient temperature. S. enterica serotype Enteritidis, S. enterica serotype Infantis, and S. enterica serotype Typhimurium have been reported to grow in fresh cut tomatoes (pH 3.99 to 4.37) at 22 and 30°C (4).

Contamination of fresh produce with salmonellae may occur at any point along the farm-to-table continuum, and salmonellae probably occur intermittently at low levels together with the diverse natural flora. Thus, rapid and sensitive methods for detecting salmonellae are in great demand in order to assure produce safety. One of the most promising methods for detecting salmonellae is based on the PCR, which combines simplicity with specificity and sensitivity for detecting the pathogens in food. Several PCR assays have been developed by targeting various Salmonella genes, such as invA (29, 31), 16S rRNA (19), agfA (14), and viaB (18), and virulence-associated plasmids (24, 30). These PCR assays are used mainly for detecting salmonellae in poultry, meat, and milk samples (5, 7, 13, 22). Few of the assays have been used to detect the pathogens in fresh produce.

Invasion is an important factor influencing the virulence of Salmonella spp. The invasive phenotype is determined by a large cluster of genes in Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI1) (26), which is present in all invasive strains of Salmonella (15). One of the SPI1 virulence genes, hilA, is a positive transcriptional regulator of several invasion genes (6). sirA, however, is a gene that is located outside SPI1 (21) and is known as a global regulator of invasion genes as well as several other genes that mediate enteropathogenesis (2).

In this study, PCR assays were developed by using primers derived from hilA and sirA. The specificities and sensitivities of the assays were evaluated by using pure cultures and were validated by detecting salmonellae in and on artificially contaminated tomatoes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

Eighty-three Salmonella strains and 22 non-Salmonella strains (Table 1) used in this study were obtained from the laboratory collections of Jinru Chen and Larry Beuchat at the Center for Food Safety and Quality Enhancement, University of Georgia. Before they were subjected to PCR, strains were retrieved from frozen stock cultures and grown in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) at 37°C for 16 to 18 h. Stock cultures were maintained on BHI agar at 4°C throughout the study.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Taxon | Serogroup | Serotype | No. of strains |

|---|---|---|---|

| Salmonella strains | B | Agona | 2 |

| Brandenburg | 2 | ||

| Bredeney | 2 | ||

| Heidelberg | 2 | ||

| Indiana | 2 | ||

| Reading | 2 | ||

| Saintpaul | 2 | ||

| Schwarzengrund | 2 | ||

| Typhimurium | 4 | ||

| C | Braenderup | 2 | |

| Choleraesuis | 1 | ||

| Haardt | 2 | ||

| Hadar | 2 | ||

| Hartford | 1 | ||

| Infantis | 3 | ||

| Kentucky | 1 | ||

| Mbandaka | 2 | ||

| Montevideo | 2 | ||

| Muenchen | 1 | ||

| Newport | 2 | ||

| Ohio | 2 | ||

| Oranienburg | 2 | ||

| Tennessee | 2 | ||

| Thompson | 2 | ||

| D | Baildon | 1 | |

| Berta | 2 | ||

| Dublin | 1 | ||

| Enteritidis | 17 | ||

| Panama | 2 | ||

| Sendai | 1 | ||

| E | Anatum | 3 | |

| F | Rubislaw | 1 | |

| G | Cubana | 1 | |

| Poona | 1 | ||

| I | Gaminara | 1 | |

| J | Michigan | 1 | |

| N | Urbana | 2 | |

| R | Johannesburg | 2 | |

| Non-Salmonella strains | |||

| Aeromonas sobria | 1 | ||

| Escherichia coli ATCC 10789 | 1 | ||

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 | 2 | ||

| Enterobacter aerogenes | 1 | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1 | ||

| Serratia marcescens | 1 | ||

| Shigella dysenteriae non-type I | 1 | ||

| Shigella sonnei | 3 | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 2 | ||

| Proteus vulgaris | 1 | ||

| Pseudomonas fluorescens | 1 | ||

| Yersinia enterocolitica | 7 |

DNA preparation.

Both crude DNA and purified DNA were used in the PCR assays. Crude DNA was prepared by boiling bacterial cell suspensions. One milliliter of an overnight bacterial culture was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 2 min (model 5415C microcentrifuge; Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany). Pellets were resuspended in 200 μl of sterile distilled water, boiled for 10 min, and centrifuged as described above. A 5-μl aliquot was used as a template for PCR. When purified DNA was prepared, a DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Specificity of PCR assays for Salmonella strains.

Four oligonucleotide primers (Table 2) derived from hilA (GenBank accession no. U25352) and sirA (GenBank accession no. U67869) were designed in this study and were synthesized by GIBCO BRL (Rockville, Md.). The specificities of all primers were tested by using 83 Salmonella strains and 22 non-Salmonella strains.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers designed and used in this study

| Primer | Target gene | Sequence (5′-3′) | PCR amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HILA1 pair | hilA | ||

| Up | CGA CGC GGA AGT TAA CGA AG | 972 | |

| Down | TCC TCC AAC TGA CCA GCC AT | ||

| HILA2 pair | hilA | ||

| Up | CTG CCG CAG TGT TAA GGA TA | 497 | |

| Down | CTG TCG CCT TAA TCG CAT GT | ||

| SIRA1 pair | sirA | ||

| Up | AAG TTG TCG GTG AAG CGT GC | 330 | |

| Down | TCT GAC TGA GCG CCA TCT GC | ||

| SIRA2 pair | sirA | ||

| Up | GCC GTA CTA ACG CCG TTG AC | 430 | |

| Down | TAG CGA TAG CTG TTC ACC GT |

Each 50-μl PCR mixture contained PCR buffer, deoxynucleoside triphosphates (0.05 mM each), primers (0.25 μM each), Taq polymerase (1 U; Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Ind.), and DNA template (5 μl, equivalent to approximately 107 CFU/ml). PCR were performed with DNA thermal cycler (model 480; Perkin-Elmer, Norwalk, Conn.) by using one cycle at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 2 min, 62°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min and final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR amplicons were analyzed by gel electrophoresis on a 1% agarose (GIBCO BRL) gel in 1× TBE buffer (0.089 M Tris-borate, 0.002 M EDTA; pH 8.0). The gel was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized with the Gel Doc System 2000 (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.).

Limits of detection of HILA2-based PCR.

S. enterica serotype Montevideo G4639, isolated from a patient infected in the 1993 tomato outbreak (32), was used for the sensitivity study and for artificial inoculation of tomatoes. The organism was grown at 37°C for 16 to 18 h in BHI broth with shaking in an incubator shaker (model G-24; New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, N.J.). Cells were harvested when the culture optical density at 600 nm was approximately 1.0 (Novaspec II spectrophotometer; Pharmacia Biotech, Cambridge, United Kingdom), plated on BHI agar, and incubated at 37°C for 24 h before colonies were counted. The cultures were serially diluted to give suspensions containing 100 to 109 CFU/ml in 10-fold increments. Crude DNA was prepared and amplified by PCR. Purified DNA from the S. enterica serotype Montevideo culture was diluted to the equivalent of 100 to 109 CFU/ml for PCR amplification.

The effect of enrichment time on sensitivity was investigated. Salmonella cultures (109 CFU/ml) were serially diluted to give 100 to 108 CFU/ml. One-hundred microliters was transferred to 900 μl of BHI broth, which was then incubated at 37°C with shaking for 3, 6, and 9 h. The cell cultures were harvested and the DNA were amplified by PCR by using the procedures described above.

PCR detection with artificially contaminated tomatoes.

Raw, ripe Roma tomatoes whose average weight was 75 g were purchased from a local grocery store and divided into two groups for surface or internal inoculation. S. enterica serotype Montevideo was grown in BHI broth at 37°C for 16 to 18 h with shaking and was harvested when the optical density at 600 nm reached 1.0, which corresponded to 109 CFU/ml. The culture was serially diluted in sterile 0.1% peptone water, and 50 μl was used for inoculation. Negative controls consisted of sterile distilled water instead of a cell suspension.

For surface contamination, each tomato was inoculated with 50 μl of an S. enterica serotype Montevideo suspension. The sizes of the inocula ranged from 100 to 105 CFU per tomato. Each inoculum was deposited in small drops to facilitate distribution and rapid drying. Inoculated tomatoes were then placed in a laminar flow hood and air dried for 2 h at 22 ± 1°C. Each tomato was placed in a stomacher bag with 20 ml of sterile 0.1% peptone water and massaged by hand for 2 min. The rinse water was transferred into 50-ml Falcon centrifuge tubes and centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min (model 5810R centrifuge; Eppendorf). The pellets were resuspended in sterile 0.1% peptone water. Five milliliters of suspension was combined with 5 ml of BHI broth for enrichment. Cells were harvested after 6 h of enrichment, and a PCR was performed. Plate counts were obtained by using BHI agar and bismuth sulfite agar (Difco) to estimate the numbers of cells.

For internal inoculation, S. enterica serotype Montevideo was injected into tomatoes around the stem scar areas by using a 20-μl pipette tip; the sizes of the inocula were ca. 100, 101, 102, 103, 104, and 105 CFU/tomato. Each inoculated tomato was placed into a stomacher filter bag with 50 ml of sterile 0.1% peptone water and stomached for 1 min at normal speed by using a Stomacher 400 (Seward, London, United Kingdom). The liquid portion was transferred into a 50-ml Falcon centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min; the supernatant fluid was centrifuged at 3,000 × g for 5 min before it was transferred to a second tube and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min. Plate counting and PCR were done as described above.

RESULTS

Specificity of the PCR assay for bacterial cultures.

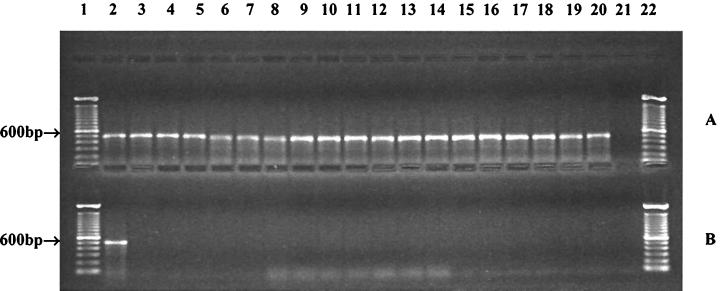

Four pairs of primers (HILA1, HILA2, SIRA1, and SIRA2) were evaluated, and one of them, HILA2, detected only Salmonella. All 83 Salmonella strains tested positive, whereas non-Salmonella strains were not detected. Figure 1 shows representative PCR products from Salmonella and non-Salmonella strains obtained with HILA2. The other three pairs of primers, HILA1, SIRA1, and SIRA2, generated nonspecific bands (data not shown). HILA1 yielded nonspecific bands with Yersinia enterocolitica, whereas SIRA1 produced nonspecific products from Escherichia coli, Shigella sonnei, Y. enterocolitica, and Pseudomonas fluorescens. The false-positive results obtained with SIRA2 were associated with E. coli, Shigella sonnei, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Serratia marcescens, and Y. enterocolitica.

FIG. 1.

Specificity of HILA2-based PCR assay for Salmonella: gel electrophoresis of PCR products in 1% agarose in 1× TBE buffer. (A) Salmonella strains. Lanes 1 and 22, 100-bp DNA ladders (GIBCO BRL); lanes 2 through 20, PCR products amplified from S. enterica serotype Anatum, S. enterica serotype Baildon, S. enterica serotype Cubana, S. enterica serotype Enteritidis, S. enterica serotype Gaminara, S. enterica serotype Hartford, S. enterica serotype Heidelberg, S. enterica serotype Infantis, S. enterica serotype Michigan, S. enterica serotype Montevideo, S. enterica serotype Muenchen, S. enterica serotype Newport, S. enterica serotype Oranienburg, S. enterica serotype Panama, S. enterica serotype Poona, S. enterica serotype Saintpaul, S. enterica serotype Thompson, S. enterica serotype Typhimurium, and S. enterica serotype Typhimurium DT 104, respectively; Lane 21, negative control. (B) Non-Salmonella strains. Lanes 1 and 22, 100-bp DNA ladders (GIBCO BRL); lane 2, S. enterica serotype Typhimurium; lanes 3 through 20, the negative results obtained with Aeromonas sobria (lane 3), Escherichia coli ATCC 10789 (lane 4), Escherichia coli O157:H7 (lanes 5 and 6), Enterobacter aerogenes (lane 7), Klebsiella pneumoniae (lane 8), Serratia marcescens (lane 9), Shigella dysenteriae non-type I (lane 10), Shigella sonnei, (lanes 11 through 13), Staphylococcus aureus, (lanes 14 and 15), Proteus vulgaris (lane 16), Pseudomonas fluorescens (lane 17), Yersinia enterocolitica (lanes 18 through 20); lane 21, negative control.

Limits of detection of PCR assay for Salmonella cultures.

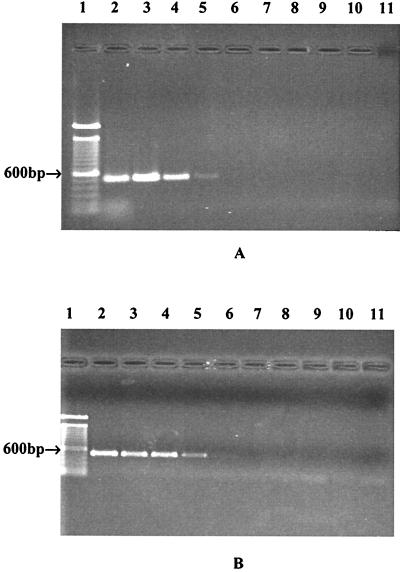

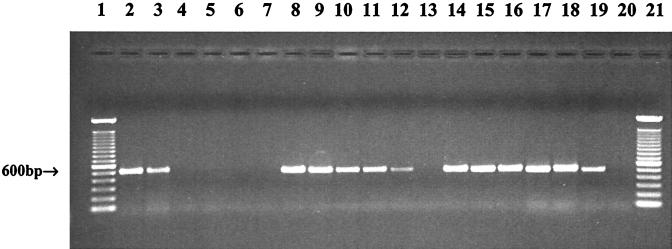

The sensitivity of the HILA2-based PCR assay was investigated. Figure 2A shows that crude DNA from a suspension containing 105 CFU/ml yielded positive amplification, whereas pure DNA extracted with the Qiagen kit provided better sensitivity, with a detection limit of 104 CFU/ml (Fig. 2B). The detection limits were as low as 101 and 100 CFU/ml with 6- and 9-h enrichments, respectively (Fig. 3).

FIG. 2.

Limits of detection of HILA2-based PCR assay. (A) PCR products amplified from crude DNA. Lane 1, 100-bp DNA ladders; lanes 2 through 10, 108, 107, 106, 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, and 100 CFU/ml, respectively; lane 11, negative control. (B) PCR products amplified from purified DNA. Lane 1, 100-bp DNA ladders; lanes 2 through 10, DNA equivalent to 108, 107, 106, 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, and 100 CFU/ml, respectively; lane 11, negative control.

FIG. 3.

Limits of detection of HILA2-based PCR assay with different enrichment times. Cell cultures containing 109 CFU/ml were serially diluted to concentrations of 108 to 100 CFU/ml, and 100-μl portions of the dilutions were transferred to 900-μl portions of BHI broth, which were then incubated at 37°C with shaking for 3, 6 and 9 h. The cells were treated, and DNA was amplified by PCR. Lanes 1 and 21, 100-bp DNA ladders; lanes 2 through 7, PCR products from preparations containing 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, and 100 CFU/ml, respectively, after 3 h of enrichment; lanes 8 through 13, PCR products from preparations containing 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, and 100 CFU/ml respectively, after 6 h of enrichment; lanes 14 through 19, PCR products from preparations containing 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, and 100 CFU/ml, respectively, after 9 h of enrichment; Lane 20, negative control.

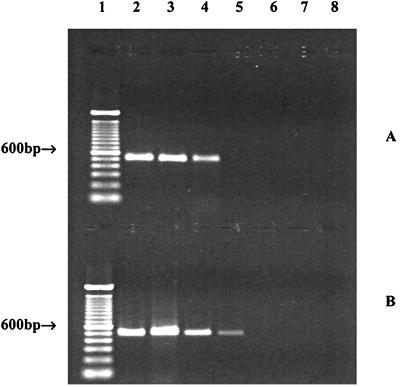

PCR detection with artificially contaminated tomatoes.

S. enterica serotype Montevideo was recovered from inoculated tomatoes. Similar counts were obtained on BHI agar and bismuth sulfite agar. Without enrichment, the detection limit was 105 CFU/tomato for surface-inoculated tomatoes (data not shown). When samples were enriched in BHI broth at 37°C for 6 h, the detection limits were 102 and 103 CFU/tomato for Salmonella on and in tomatoes, respectively (Fig. 4). Since the average weight of the tomatoes was 75 g, the detection limits were equivalent to 101 and 102 CFU/g for Salmonella on and in tomatoes, respectively.

FIG. 4.

Use of HILA2-based PCR assay to detect S. enterica serotype Montevideo on and in artificially inoculated tomatoes. Tomatoes were inoculated with different levels of S. enterica serotype Montevideo, and cells were then recovered and enriched for 6 h. Crude DNA was prepared and subjected to PCR amplification. (A) Detection of S. enterica serotype Montevideo in tomatoes. (B) Detection of S. enterica serotype Montevideo on tomato surfaces. Lane 1, 100-bp DNA ladders; lanes 2 to 7, PCR products amplified from preparations containing 105, 104, 103, 102, 101, and 100 CFU/tomato, respectively; lane 8, negative control.

DISCUSSION

Various sets of primers for PCR detection of salmonellae have been described previously (14, 18, 19, 24, 29, 30, 31). Gooding and Chaudary (17) recently conducted a comparison study of primers with different test panels of Salmonella and non-Salmonella strains and different PCR conditions and found that there were variations with regard to the specificities of the primers. The results of our study indicate that the HILA2 primer set is very specific for Salmonella strains, whereas the HILA1, SIRA1, and SIRA2 primers generated false-positive results for non-Salmonella strains.

The lack of specificity of SIRA primers may be explained by the roles of sirA genes in the pathogenicity of Salmonella. It has been reported that all serovars of S. enterica encode a type III protein secretion system within a pathogenicity island (SPI1) at centisome 63 on the chromosome and that this system is essential for pathogenicity (15). HilA is a transcriptional regulator of the ompR-toxR family encoded within SPI1 and controls expression of other SPI1 genes (6). sirA, located outside SPI1, is an activator of hilA (21), which is also known to be a global regulator of several other genes mediating enteropathogenesis (2). In addition, sirA appears to be a housekeeping regulator that has been adapted to virulence gene regulation in a variety of non-Salmonella bacteria, such as Escherichia, Erwinia, Pseudomonas, and Vibrio strains (1). E. coli possesses a sirA gene but does not contain hilA or SPI1 (2). Therefore, it was understandable that the SIRA primer sets were not specific for Salmonella.

Although both crude DNA and purified DNA worked well in PCR, the detection limits were somewhat different. Crude DNA obtained after cells were boiled could be detected in suspensions containing 105 CFU/ml, whereas the threshold of detection for extracted DNA increased 1 log in a suspension containing 104 CFU/ml. Due to the longer preparation time, DNA was prepared by boiling in further studies. If fresh produce is contaminated with Salmonella, low numbers of cells would be present, and thus enrichment would be required for detection.

Tomatoes, which have been implicated as sources of Salmonella infection in several multistate outbreaks (12; Wood et al., Epidemic Intelligence Service 40th Annu. Conf.), were chosen as a model in this study. The HILA2 primer set was found to detect S. enterica serotype Montevideo on tomatoes. Fresh produce may contain a natural microflora that reflects the production and harvest environments. Lactic acid bacteria and Citrobacter, Enterobacter, Erwinia, Pseudomonas, and Flavobacterium strains are frequently associated with plant products (20). Ogunjimi et al. (27) reported that endogenous polyphenol, which is ubiquitous in plant products, interfered with immuno-PCR detection of E. coli O157:H7. Moreover, ripe tomatoes have a pH range of 4.0 to 4.4. These factors may have an impact on PCR detection of Salmonella in inoculated tomatoes. The results of this study showed that in the presence of a natural biota, S. enterica serotype Montevideo was recovered after centrifugation, and as little as 101 and 102 CFU/g could be detected on and in tomatoes, respectively, after 6 h of enrichment. The detection limit for samples that were subjected to internal inoculation may have been affected by sample treatment. Smaller populations of bacteria (<102 CFU/g) may not be accessible to PCR due to physical interference and thus would not be detected by the procedure used in this study.

Our results demonstrate that HILA2 is very specific for Salmonella. The PCR assay based on the HILA2 primer may also be used to detect salmonellae on other fresh produce.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmer B M M, Heffron F. Salmonella typhimurium recognition of intestinal environments: response. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7:222–223. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01524-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahmer B M M, Van Reeuwijk J, Watson P R, Wallis T S, Heffron F. Salmonella SirA is a global regulator of genes mediating enteropathogenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:971–982. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altekruse S F, Cohen M L, Swerdlow D L. Emerging foodborne disease. Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3:285–293. doi: 10.3201/eid0303.970304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asplund K, Nurmi E. The growth of salmonellae in tomatoes. Int J Food Microbiol. 1991;13:177–182. doi: 10.1016/0168-1605(91)90059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bailey J S. Detection of Salmonella cells within 24–26 hrs in poultry samples with the PCR BAX system. J Food Prot. 1998;61:792–795. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-61.7.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajaj V, Hwang C, Lee C A. hilA is a novel ompR/toxR family member that activates expression of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes. Mol Microbiol. 1995;18:715–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.mmi_18040715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bennett A R, Greenwood D, Tennant C, Banks J G, Betts R P. Rapid and definitive detection of Salmonella in foods by PCR. Lett Appl Microbiol. 1998;26:437–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1472-765x.1998.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blostein J. An outbreak of Salmonella javiana associated with consumption of watermelon. J Environ Health. 1991;56:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Salmonella typhimurium outbreak traced to a commercial apple cider—New Jersey. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1975;24:87–88. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Salmonella oranienburg gastroenteritis associated with consumption of precut watermelons, Illinois. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1979;28:522–523. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multi-state outbreak of Salmonella poona infections—United States and Canada. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1991;40:549–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multi-state outbreak of Salmonella serotype Montivideo infections. Publication EPI-AID 93–97. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen S, Yee A, Griffiths M, Larkin C, Yamashiro C T, Behari R, Paszko-Kolva C, Rahn K, De Grandis S A. The evaluation of a fluorogenic polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of Salmonella species in food commodities. Int J Food Microbiol. 1997;35:239–250. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1605(97)01241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doran J L, Collinson S K, Burian J, Sarlos G, Todd E C D, Munro C K, Kay C M, Banser P A, Peterkin P I, Kay W W. DNA-based diagnostic test for Salmonella species targeting agfA, the structural gene for thin aggregative fimbriae. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2263–2273. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.9.2263-2273.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Galán J E. Molecular genetic bases of Salmonella entry into host cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:263–271. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gayler G E, MacCready R A, Reardon J P, McKernan B F. An outbreak of salmonellosis traced to watermelon. Public Health Rep. 1955;70:311–313. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gooding C M, Choudary P V. Comparison of different primers for rapid detection of Salmonella using the polymerase chain reaction. Mol Cell Probes. 1999;13:341–347. doi: 10.1006/mcpr.1999.0257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashimoto Y, Itho Y, Fujinaga Y, Khan A Q, Sultana F, Miyake M, Hirose K, Yamamoto H, Ezaki T. Development of nested PCR based on the ViaB sequence to detect Salmonella typhi. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:775–777. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.775-777.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iida K, Abe A, Matsui H, Danbara H, Wakayama S, Kawahara K. Rapid and sensitive method for detection of Salmonella strains using a combination of polymerase chain reaction and reverse dot-blot hybridization. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;114:167–172. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06568.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jay J M. Modern food microbiology. 5th ed. New York, N.Y: Chapman & Hall; 1996. Fresh and fermented fruit and vegetable products; pp. 149–176. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnston C, Peguse D A, Hueck C J, Lee C A, Miller S I. Transcriptional activation of Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes by a member of the phosphorylated response-regulator superfamily. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:715–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.d01-1719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kimura B, Kawasaki S, Fujii T, Kusunoki J, Itoh T, Flood S J A. Evaluation of TaqMan PCR assay for detecting Salmonella in raw meat and shrimp. J Food Prot. 1999;62:329–335. doi: 10.4315/0362-028x-62.4.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahon B E, Pönkä A, Hall W, Komatsu K, Beuchat L, Dietrich S, Siitonen A, Cage G, Lambert-Fair M, Hayes P, Bean N, Griffin P, Slutsker L. An international outbreak of Salmonella infections caused by alfalfa sprouts grown from contaminated seed. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:876–882. doi: 10.1086/513985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mahon J, Lax A. A quantitative polymerase chain reaction method for the detection in avian faeces of salmonellas carrying the spvR gene. Epidemiol Infect. 1993;111:455–464. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mead P S, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig L F, Bresee J S, Shapiro C, Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:607–625. doi: 10.3201/eid0505.990502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mills D M, Bajaj V, Lee C A. A 40 kb chromosomal fragment encoding Salmonella typhimurium invasion genes is absent from the corresponding region of the Escherichia coli K-12 chromosome. Mol Microbiol. 1995;15:749–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02382.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogunjimi A A, Choudary P V. Adsorption of endogenous polyphenols relieves the inhibition by fruit juices and fresh produce of immuno-PCR detection of Escherichia coli O157:H7. FEMS Immuno Med Microbiol. 1999;23:213–220. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Mahony M, Cowden J, Smyth B, Lynch D, Hall M, Rowe B, Teare E L, Tettmar R E, Coles A M, Gilbert R J, Kingcott E, Bartlett C L R. An outbreak of Salmonella saint-paul infection associated with bean sprouts. Epidemiol Infect. 1990;104:229–235. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800059392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rahn K, De Grandis S A, Clarke R C, McEwen S A, Galan J E, Ginocchio C, Curtiss III R, Gyles C L. Amplification of an invA gene sequence of Salmonella typhimurium by polymerase chain reaction as a specific method of detection of Salmonella. Mol Cell Probes. 1992;6:271–279. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(92)90002-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rexach L, Dilasser F, Fach P. Polymerase chain reaction for Salmonella virulence-associated plasmid genes detection: a new tool in Salmonella epidemiology. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:33–43. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800057393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang H, Blais B W, Yamazaki H. Rapid confirmation of polymyxin-cloth enzyme immunoassay for group D salmonellae including Salmonella enteritidis in eggs by polymerase chain reaction. Food Control. 1995;6:205–209. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhuang R Y, Beuchat L R, Angulo F J. Fate of Salmonella montevideo on and in raw tomatoes as affected by temperature and treatment with chlorine. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1995;61:2127–2131. doi: 10.1128/aem.61.6.2127-2131.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]