Abstract

Introduction

Information on the off–label use of Long–Acting Injectable (LAI) antipsychotics in the real world is lacking. In this study, we aimed to identify the sociodemographic and clinical features of patients treated with on– vs off–label LAIs and predictors of off–label First– or Second–Generation Antipsychotic (FGA vs. SGA) LAI choice in everyday clinical practice.

Method

In a naturalistic national cohort of 449 patients who initiated LAI treatment in the STAR Network Depot Study, two groups were identified based on off– or on–label prescriptions. A multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to test several clinically relevant variables and identify those associated with the choice of FGA vs SGA prescription in the off–label group.

Results

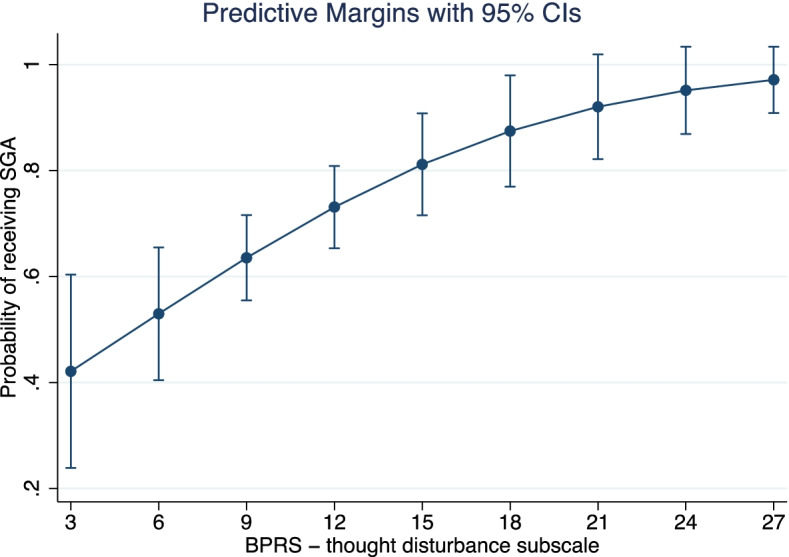

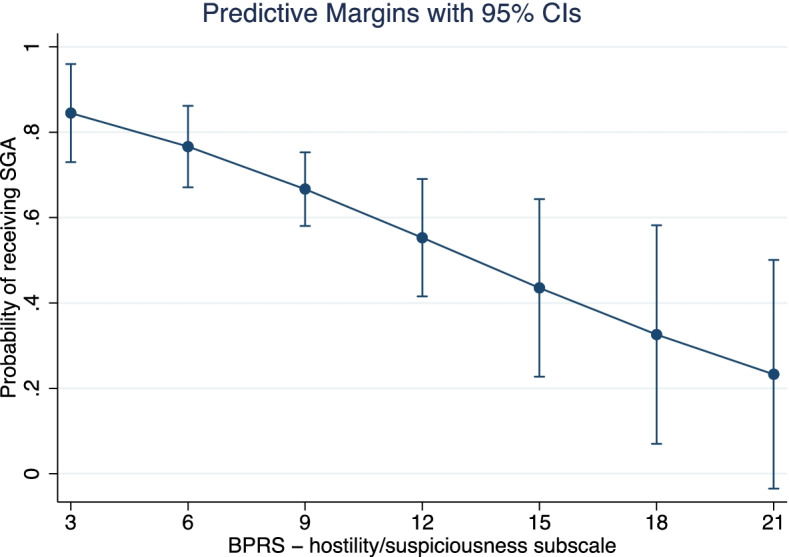

SGA LAIs were more commonly prescribed in everyday practice, without significant differences in their on– and off–label use. Approximately 1 in 4 patients received an off–label prescription. In the off–label group, the most frequent diagnoses were bipolar disorder (67.5%) or any personality disorder (23.7%). FGA vs SGA LAI choice was significantly associated with BPRS thought disorder (OR = 1.22, CI95% 1.04 to 1.43, p = 0.015) and hostility/suspiciousness (OR = 0.83, CI95% 0.71 to 0.97, p = 0.017) dimensions. The likelihood of receiving an SGA LAI grew steadily with the increase of the BPRS thought disturbance score. Conversely, a preference towards prescribing an FGA was observed with higher scores at the BPRS hostility/suspiciousness subscale.

Conclusion

Our study is the first to identify predictors of FGA vs SGA choice in patients treated with off–label LAI antipsychotics. Demographic characteristics, i.e. age, sex, and substance/alcohol use co–morbidities did not appear to influence the choice towards FGAs or SGAs. Despite a lack of evidence, clinicians tend to favour FGA over SGA LAIs in bipolar or personality disorder patients with relevant hostility. Further research is needed to evaluate treatment adherence and clinical effectiveness of these prescriptive patterns.

Keywords: Long-acting injectable antipsychotics, Schizophrenia, Bipolar disorder, Personality disorder, Off-label

Introduction

Antipsychotic drugs are classically distinguished in First–Generation (FGA, also called “typical” or “conventional”) and Second–Generation Antipsychotics (SGA, also called “atypical”) based on their mechanism of action and side effects profile [1]. All available formulations are licensed internationally for use in patients diagnosed with Schizophrenia (SCZ), but some regulatory agencies have extended their use to other conditions. Off-label prescription of antipsychotics is very common in clinical practice [2–6], having been estimated to occur in at least one every five patients for oral SGAs [7]. However, reliable data on off-label use of other formulations in clinical practice are lacking. Long–Acting Injectable (LAI) or “depot” formulations have been employed for decades in the treatment of patients with low adherence to oral antipsychotics [7, 8]. International guidelines have recently begun to support their use in first–episode psychosis [6], perhaps leading to an increase in prescription that is likely to also expand their off–label use.

Beyond their established role in the treatment of SCZ, risperidone and aripiprazole LAI are considered a safe and effective alternative to oral medications in the management of Bipolar Disorder (BD) [9]. These two SGA LAIs have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for maintenance in BD, whereas none have been approved by the European Medical Agency (EMA) for treatment beyond SCZ. Coherently, the Italian Medicines Agency (AIFA) licensed SGA LAI antipsychotics only for SCZ, although three FGA LAIs have long–standing extensions to patients with schizoaffective disorder (haloperidol) and manic states (zuclopenthixol and fluphenazine).

Two recent surveys explored attitudes of Italian psychiatrists towards off–label prescription of both oral and LAI SGAs [10, 11]. The main motivation for prescribing off–label SGAs was the presence of published evidence in the literature (51.5%), followed by a patient’s lack of response to previous on–label treatment (37.1%). In descending order, aripiprazole, olanzapine, risperidone, and paliperidone LAIs were all considered appropriate for the long-term maintenance treatment of BD [10]. Off–label SGA LAI prescription has also been proposed for the treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD), although no antipsychotic has been approved internationally for this condition and clinicians appear to consider their use inappropriate for these patients [11]. Despite this information, very little is known on the factors that lead clinicians to choose a LAI when commencing treatment in everyday clinical practice. Given the relative poverty of available evidence on LAI use beyond SCZ, and the safety concerns related to off–label antipsychotics, real–world data on prescriptive patterns seem necessary. In particular, the characterization of patients who receive FGA or SGA LAIs off–label may contribute to interpret current practice and to shape future recommendations.

In a large, observational cohort, we have previously shown that patients who receive a novel prescription of any SGA LAI are likely to be younger, occupied, have a diagnosis of either SCZ or BD and have more affective symptoms than those who receive an FGA LAI [12]. Given the relatively sparse knowledge on the everyday off–label use of LAI formulations, we designed an exploratory study in the same cohort with the following objectives:

To identify sociodemographic and clinical features of patients treated with on– or off–label LAI prescriptions.

To identify predictors of off–label FGA or SGA LAI choice in everyday clinical practice.

Materials and method

Study design

This STAR Network Depot study was designed according to the STROBE (STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology) Statement as a multicentre, longitudinal observational study that has been described in detail elsewhere [12]. The protocol was approved by the local Ethics Committees of all participating centres and is publicly available at the Open Science Framework (OSF) online repository (https://osf.io/wt8kx/). All patients who initiated any LAI treatment over a 12–month time span within a consortium comprising 35 territory and university mental health departments in Italy (STAR Network – Servizi Territoriali Associati per la Ricerca), were consecutively screened for inclusion. After screening, each participant was followed up after 6 and 12 months. Inclusion criteria were: (1) participants over 18 years of age, (2) signed informed consent for voluntary participation, and (3) a new prescription of an LAI antipsychotic. Patients who had previously been administered LAIs were only included if the previous one had been suspended for at least 3 months. The recruitment period lasted from December 2015 to May 2017.

For the specific aims of this study, only cross-sectional baseline data were retrieved for all recruited patients. Table 1 shows the diagnostic prescriptive labelling of all LAI antipsychotics retrieved, according to which we compared sociodemographic and clinical variables of two experimental samples (on-label vs off-label). In an exploratory subgroup analysis, we then identified sociodemographic and clinical predictors of FGA vs SGA choice in those who received an off-label prescription.

Table 1.

List of compounds used as LAI treatment and their on– / off–label indications based on diagnoses in the study cohort

| Pharmaceutical Compound | Dosage | Schizophrenia | Bipolar Disorder | Major depression | Obsessive compulsive Disorder | Personality Disorder | Neurodevelopmental Disorder | Neurocognitive Disorder | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haloperidol Decanoatea (FGA) | 12,5–300 mg/monthly | ON LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL |

| Zuclopenthixol Decanoateb (FGA) | 100–600 mg/biweekly | ON LABEL | ON LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL |

| Fluphenazine Decanoatec (FGA) | 12,5–100 mg/biweekly | ON LABEL | ON LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL |

| Risperidone LAId (SGA) | 25–50 mg/biweekly | ON LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL |

| Paliperidone Palmitated (SGA) | 25–150 mg/monthly | ON LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL |

| Olanzapine Pamoated (SGA) | 300–405 mg/monthly | ON LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL |

| Aripiprazole LAId (SGA) | 400 mg/monthly | ON LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL | OFF LABEL |

aHaloperidol Decanoate is licensed for the maintenance treatment of Schizophrenia and Schizoaffective Disorder

bZuclopenthixol Decanoate is licensed for acute and chronic Schizophrenia and other dissociative syndromes characterized by symptoms such as hallucination, agitation, psychomotor excitement, hostility, aggressiveness and affective disturbances. Manic phase of manic–depressive psychosis

cFluphenazine decanoate is licensed for the treatment of Schizophrenia and manic syndromes

dAll SGA LAIs are licensed for the maintenance treatment of adults diagnosed with Schizophrenia

All licensing information refers to the Italian Medicines Agency (Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco, AIFA), FGA First–Generation Antipsychotic, SGA Second–Generation Antipsychotic

Clinical assessment

The following sociodemographic and clinical variables were collected upon inclusion: age, sex, education, year of first contact with any psychiatric service, diagnosis, alcohol and other psychoactive substance use, and number and characteristics of hospitalizations in the previous 6 months. At baseline, all patients were assessed with the Italian version of the Brief Psychiatry Rating Scale (BPRS) [13, 14]. A score range from 31 to 40 indicates mild symptoms, from 41 to 52 moderate symptoms, and above 52 severe symptoms [15]. Besides the total score, the following five symptom dimensions were assessed: anxious/depressive symptoms, thought disorder, withdrawal/retardation, hostility/suspiciousness, and activation [16]. The first three dimensions are composed of 4 items each, with each dimension score calculated out of 28; the last two are composed of 3 items each, with each dimension score calculated out of 21.

Additionally, Kemp’s 7-point was employed as a measure of treatment acceptance [17]. Patients were also asked to complete the validated Italian version of the Drug Attitude Inventory 10-items (DAI-10) [18].

Study population

We previously reported a total of 451 patients (M–F 60.8–39.2%; mean age = 41.6 ± 12.9 years) recruited [12, 19]. In this sample, 251 (55.7%) were diagnosed with SCZ, whereas 81 with BD (18.0%), 74 with schizoaffective disorder (16.4%), 27 with any personality disorder (6.0%) and the rest with a minority of other conditions (3.9%). Given the pragmatic nature of the study, no structured interview was used to confirm diagnoses, which were formulated by participating recruiters based on DSM–5 criteria [20]. For the aims of this study, two groups (on–label vs off–label) were identified by dividing the cohort as shown in Table 2. The World Health Organization broadly defines “off-label” as the use of any medication for an unapproved indication, age group, dosage, duration, or route of administration. Here, off–label use was only considered for unapproved indication at the time of initial prescription. All LAI prescriptions for patients diagnosed within the DSM–5 “Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders” clustering [20] were considered on–label. Therefore, patients diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder were considered on–label for any LAI prescription although only haloperidol decanoate is specifically licensed for this condition in Italy.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients (n = 449) treated with a Long Acting Injection (LAI) drug, divided in on–label and off–label prescription

| ON LABEL | OFF LABEL | SIG | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | p = 0.000 | ||

| SCZ (n = 331) | 331 (100%) | 0 | |

| Schizophrenia | 251 (100%) | 0 | |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 74 (100%) | 0 | |

| Organic Psychosis | 4 (100%) | 0 | |

| Substance-related psychosis | 2 (100%) | 0 | |

| NO-SCZ (n = 118) | 4 (3.4%) | 114 (96.6%) | |

| Bipolar Disorder | 4 (4.9%) | 77 (95.1%) | |

| OCD | 0 | 4 (100%) | |

| Personality disorder | 0 | 27 (100%) | |

| Neurodevelopment disorder | 0 | 4 (100%) | |

| Neurocognitive disorder | 0 | 2 (100%) | |

| Age* | 40.97 ± 12.65 | 44.11 ± 13.18 | p = 0.0334 |

| Previous LAI therapy | p = 0.14 | ||

| Yes (n = 135) | 107 (79.3%) | 28 (20.7%) | |

| No (n = 314) | 228 (72.6%) | 86 (27.4%) | |

| Drug category | p = 0.52 | ||

| FGA (n = 135) | 98 (72.6%) | 37 (27.4%) | |

| SGA (n = 314) | 237 (75.5%) | 77 (24.5%) | |

| Gender | p = 0.044 | ||

| Male (n = 272) | 212 (77.9%) | 60 (22.1%) | |

| Female (n = 177) | 123 (69.5%) | 54 (30.5%) | |

| Alcohol | p = 0.021 | ||

| Yes (n = 65) | 41 (63.1%) | 24 (36.9%) | |

| No (n = 384) | 294 (76.6%) | 90 (23.4%) | |

| Substance Misuse | p = 0.26 | ||

| Yes (n = 90) | 63 (70%) | 27 (30%) | |

| No (n = 359) | 272 (75.8%) | 87 (24.2%) | |

| BPRS total* | 50.45 ± 14.66 | 45.12 ± 14.09 | p = 0.0013 |

| BPRS anxiety depression* | 10.44 ± 4.36 | 10.88 ± 4.25 | p = 0.33 |

| BPRS anergy* | 9.83 ± 4.27 | 8.01 ± 3.56 | p = 0.0001 |

| BPRS thought disturbances* | 12.88 ± 5.37 | 9.91 ± 4.89 | p = 0.0000 |

| BPRS activation* | 7.64 ± 3.35 | 7.63 ± 3.35 | p = 0.91 |

| BPRS hostility* | 9.68 ± 4.46 | 8.69 ± 4.40 | p = 0.0474 |

| Kemp’s 7 total* | 4.81 ± 1.44 | 4.74 ± 1.43 | p = 0.64 |

| DAI-10 total* | 1.78 ± 5.39 | 2.57 ± 5.24 | p = 0.15 |

SCZ Schizophrenia Spectrum patients, NO-SCZ patients with a diagnosis not included in the schizophrenia spectrum, OCD obsessive compulsive disorder, FGA First Generation Antipsychotic, SGA Second Generation Antipsychotic, SIG significance

All reported values are frequencies, except for *(mean ± standard deviation). In bold p-values below 0.05

Two patients were excluded from the analysis because the study group could not be assigned due to the missing diagnosis variable. Therefore, the analysed sample includes 449 patients.

Statistical analysis

We summarised the baseline variables for the recruited sample, as well as for the on–label and off–label groups. To compare the on–label and off–label groups and highlight their differences, we analysed continuous variables with a Mann-Whitney U test, and categorial variables with a Chi2 test.

Finally, we ran a multivariate logistic regression analysis to test a number of clinically relevant variables and identify those associated with a different prescription (FGA vs SGA, dependent variable) in the off–label sub-group. The list of the investigated independent variables is sex (female, male), age (continuous), recent use of psychoactive substances (yes, no), recent alcohol use (yes, no), the first treatment with a LAI antipsychotic (yes, no), BPRS subscales (continuous), DAI-10 scale (continuous), and the Kemp’s 7-point scale (continuous). The goodness-of-fit of the resulting model was analysed with a Hosmer-Lemeshow test, while the model was interpreted with the McKelvey-Zavoina pseudo-R2. We performed the statistical analyses using Stata 14 [21].

Results

On–label vs off–label prescription

Comparative data between the two samples of patients treated with on– and off–label LAIs can be viewed in Table 2. Of 449 patients, 335 (74.6%) belonged to the on–label group and 114 (25.4%) to the off–label one. Almost all the patients in the on–label group (98.8%) presented a SCZ-spectrum diagnosis, whereas most patients in the off–label group had a BD diagnosis (67.5%). The off–label group did not include any patient with a SCZ-spectrum diagnosis. The two groups differed significantly in terms of age and sex, as patients in the on–label group were relatively younger (40.97 ± 12.65 vs 44.11 ± 13.18, p < 0.05) and more frequently male (63.3% vs 52.6%, p < 0.05). The use of alcohol, but not illicit substances, was found to be more frequent in patients with off–label prescriptions (23% vs 12.2% respectively, p < 0.05).

No statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of FGA vs SGA use. One hundred and seven patients (31.9%) in the on–label group had a previous LAI therapy, compared to 28 (24.6%) in the off–label group.

When BPRS scores were compared between the two groups, total score and anergy, thought disturbances, and hostility dimensions scores were found to significantly differ, being higher in the on–label group. As shown in Table 2, neither DAI-10 scores nor Kemp’s 7-point scales revealed any significant differences between the two groups.

Off–label FGA vs SGA prescription

The analysis on the off–label subgroup showed that the preference in choosing between FGA vs SGA LAIs was significantly associated with the BPRS thought disorder and BPRS hostility/suspiciousness dimensions (Table 3), with ORs of 1.22 (CI95% 1.04 to 1.43, p = 0.015) and 0.83 (CI95% 0.71 to 0.97, p = 0.017), respectively. In this population, the likelihood of receiving an SGA LAI grew steadily with the increase of the BPRS thought disturbance score. Figure 1 shows the predictive margins of SGA prescription for each thought disturbance score, calculated for each observation in the data and then averaged. Conversely, a preference towards prescribing an FGA was observed with higher scores at the BPRS hostility/suspiciousness subscale. Figure 2 shows the predictive margins of FGA prescription for each hostility/suspiciousness score, calculated for each observation in the data and then averaged. The model showed acceptable measures in terms of goodness-of-fit (H-L Chi2 p = 0.7185) with an MZ pseudo-R2 of 31.5%, BIC = 182.214.

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis comparing the preference in choosing FGA vs SGA drugs in the off-label subgroup

| OR [CI95%] | SIG | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 0.979 [0.942–1.016] | 0.270 |

| Sex | 0.356 | |

| Male | (ref) | |

| Female | 0.630 [0.236–1.681] | |

| Substance Misuse | 0.271 | |

| No | (ref) | |

| Yes | 0.480 [0.130–1.774] | |

| Alcohol | 0.521 | |

| No | (ref) | |

| Yes | 1.464 [0.458–4.678] | |

| First administration | 0.359 | |

| No | (ref) | |

| Yes | 1.491 [0.502–4.430] | |

| BPRS anxiety depression | 1.102 [0.958–1.267] | 0.173 |

| BPRS anergy | 0.920 [0.791–1.070] | 0.279 |

| BPRS thought disturbances | 1.217 [1.039–1.426] | 0.015* |

| BPRS activation | 0.913 [0.731–1.140] | 0.423 |

| BPRS hostility | 0.830 [0.711–0.967] | 0.017* |

| DAI-10 total | 1.001 [0.905–1.106] | 0.987 |

| Kemp’s 7 total | 1.311 [0.896–1.919] | 0.896 |

P value of the model = 0.0358, OR Odds Ratio, IC Confidence Interval, SIG significance

Fig. 1.

Likelihood of receiving an SGA based on BPRS thought disturbances score. The larger confidence interval suggests greater uncertainty for lower scores

Fig. 2.

Likelihood of receiving an SGA based on BPRS hostility score. The larger confidence interval suggests greater uncertainty for higher scores

Discussion

The reported study revealed several differences between patients who received on–label and off–label prescriptions of a new LAI antipsychotic. In the off–label group, BD was the most frequent diagnosis, followed by personality disorders. Since all the included LAIs are licenced for SCZ, all patients with a SCZ–spectrum diagnosis were included in the on–label group. This may have contributed to the observed differences between the two samples. For example, the difference observed in terms of alcohol use between the on– and off–label groups could be ascribed to relatively lower alcohol consumption in SCZ patients compared to those with mood and personality disorders [21]. However, alcohol use is strongly associated with impulsivity and behavioural abnormalities [22] and might encourage the choice of a LAI treatment, albeit off–label. Likewise, the greater intensity of symptoms observed in the on–label group might reflect a relatively worse psychopathology in SCZ patients compared to those with BD and personality disorders when a new LAI is prescribed. Several sub-items – anergy, hostility, and thought disturbances – were higher in the on–label group compared to the off–label one. Indeed, compared to those with other diagnoses, SCZ patients typically present more negative symptoms, thought disturbances and hostility driven by a substantial lack of insight.

Although the BPRS may not fully capture the extent of clinical symptoms presented by patients with mood and personality disorders, our findings suggest off–label LAIs are prescribed in these patients despite a relatively lower intensity of psychopathology compared to SCZ patients who begin a new on–label LAI. Previous studies have shown that LAI treatment in BD is a viable option for patients with low treatment adherence or an unstable illness with predominant manic recurrences [23]. A panel of experts recently suggested that BD patients with co–morbid substance use disorder, family history of bipolar illness, and use of multiple medications may be particularly good candidates for LAI antipsychotic treatment [24].

Of note, females were relatively more present in the off–label group, perhaps reflecting the epidemiology of clinical diagnoses in this sample. Indeed, female sex is relatively more represented in cohorts of patients with mood and personality disorders compared to SCZ [25, 26]. The finding of a slightly older mean age in the off–label group could suggest that off–label LAI prescription is delayed in these patients’ clinical course, perhaps due to uncertainty on safety and effectiveness.

Our study is also the first to identify sociodemographic, clinical features and predictors of FGA vs SGA choice in patients treated with off–label LAI antipsychotics. In general, we found that SGA LAIs were more commonly prescribed in everyday practice, without significant differences in their on– and off–label use. In the off–label group, we identified predictors of FGA or SGA LAI choice in everyday clinical practice. Among several tested variables, demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex) and comorbidities, such as alcohol and substance use, seem not to influence the choice towards FGAs or SGAs. A higher mean score in the hostility/suspiciousness symptom dimension was associated with an increased likelihood of receiving an FGA compared to an SGA LAI prescription. Hostility implies a tendency to feel anger towards people, which has been associated with aggressiveness in a variety of mental disorders [27]. Hence, this association might underline the clinical tendency to judge FGAs more efficient than SGAs for the treatment of aggressiveness, with the latter preferred to address mood and positive symptoms. Indeed, LAIs are known to significantly reduce the hostility, aggressiveness, and frequency of violent episodes in SCZ spectrum diagnoses [28]. However, the literature on this topic is poor and recent studies failed to show significant differences between FGAs and SGAs [29, 30]. If the choice of an FGA is supported by well-established practical experience and economic consideration, the tolerability profile might favour SGAs. Indeed, a recent retrospective chart review study of 157 cases with SCZ spectrum diagnoses suggested prescriber choice should be guided by factors such as side–effect profile, patient acceptability and price [31]. Nonetheless, a class profile of tolerability could be misleading because specific compounds have been associated with very different side effect profiles [32]. In the same cohort, we have previously shown that clinicians are more inclined to prescribe paliperidone palmitate than aripiprazole monohydrate to subjects with higher symptom severity [31], although the latter might be superior in terms of tolerability and healthcare costs [33, 34].

Notably, neither the clinician–rated adherence to treatment nor the patient–rated attitude towards medication differentiated on– and off–label prescription groups. Likewise, neither appeared to predict the choice of administering FGA vs SGA in the off–label group. Taken together, these findings suggest that low adherence and negative attitude towards medication are defining aspects of patients who receive a new LAI prescription, independent of its licensing or generation.

Study limitations

This study has several limitations. First, we only examined cross-sectional data at the time of a novel LAI prescription, so efficacy and tolerability could not be evaluated. Future analyses of longitudinal modifications will be useful to have an insight of the course of the off–label prescriptions in our cohort. Second, clinical diagnoses were not confirmed through a structured interview, so some variability can be expected to have occurred across sites. Moreover, a large group of patients with diagnoses other than SCZ were considered on–label if their diagnosis fell within the DSM-5 “Schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders” clustering. In particular, 74 patients with schizoaffective disorder were considered on–label although no SGA LAI has specifically been licensed for this diagnosis. Nonetheless, we chose to include patients with this controversial diagnosis in a SCZ grouping, in line with both DSM–5 [20] and ICD–11 [35]. Third, it was not possible to ascertain whether and to what extent legal practices for the off–label prescription of drugs were employed, and if adequate information was provided to the patients. Further studies to assess this issue might be relevant, considering possible risks of the frequent use of off–label medications in vulnerable populations of patients with severe mental disorders. Fourth, no information was available on the mood episode or dominant polarity of BD and schizoaffective disorder patients, which might have influenced the prescriber’s choice of FGA vs SGA LAI. Finally, the characteristics of centres involved in the Italian STAR Network were heterogeneous and different local availability of drug formulations might have affected the choice of treatment.

Conclusion

Both FGA and SGA LAIs are frequently prescribed off–label in real–world clinical practice, particularly in people diagnosed with BD and personality disorders. Although no previous evidence supports a larger benefit of FGA LAIs when addressing hostility, clinicians tend to privilege them over newer compounds when initiating off–label LAI treatment, whereas SGA LAIs are generally preferred in patients with more severe thought disturbances. Future analyses on the study cohort follow-up data will be fundamental to evaluate treatment adherence and the clinical effectiveness of these prescriptive choices.

Acknowledgements

Edoardo G. Ostinelli is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Professorship to Professor Andrea Cipriani (grant RP-2017-08-ST2-006), by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration Oxford and Thames Valley (ARC OxTV) at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust, by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford cognitive health Clinical Research Facility and by the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre (grant BRC-1215-20005). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. Caroline Zangani is supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford cognitive health Clinical Research Facility and by the NIHR Oxford Health Biomedical Research Centre (grant BRC-1215-20005). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the UK National Health Service, the NIHR, or the UK Department of Health.

STAR Network Depot Investigators

The STAR Network Depot Investigators are: Corrado Barbui5, Michela Nosè5, Marianna Purgato5, Giulia Turrini5, Giovanni Ostuzzi5, Maria Angela Mazzi5, Davide Papola5, Chiara Gastaldon5, Samira Terlizzi5, Federico Bertolini5, Alberto Piccoli5, Mirella Ruggeri5, Pasquale De Fazio11, Fabio Magliocco11, Mariarita Caroleo11, Gaetano Raffaele11, Armando D′Agostino1,2, Edoardo Giuseppe Ostinelli1,7,8,9, Margherita Chirico1,2, Simone Cavallotti2, Emilio Bergamelli1,2, Caroline Zangani1,7,8,9, Claudio Lucii12, Simone Bolognesi13, Sara Debolini12, Elisa Pierantozzi12, Francesco Fargnoli12, Maria Del Zanna12, Alessandra Giannini12, Livia Luccarelli12, Alberto De Capua12, Pasqua Maria Annese12, Massimiliano Cerretini12, Fiorella Tozzi12, Nadia Magnani14, Giuseppe Cardamone14, Francesco Bardicchia14, Edvige Facchi14, Federica Soscia14, Spyridon Zotos15, Bruno Biancosino16, Filippo Zonta17, Francesco Pompei18, Camilla Callegari19, Daniele Zizolfi19, Nicola Poloni19, Marta Ielmini19, Ivano Caselli19, Edoardo Giana19, Aldo Buzzi19, Marcello Diurni19, Anna Milano19, Emanuele Sani19, Roberta Calzolari19, Paola Bortolaso20, Marco Piccinelli20, Sara Cazzamalli20, Gabrio Alberini20, Silvia Piantanida20, Chiara Costantini20, Chiara Paronelli20, Angela Di Caro20, Valentina Moretti21, Mauro Gozzi21, Chiara D’Ippolito21, Silva Veronica Barbanti21, Papalini Alessandro21, Mariangela Corbo10, Giovanni Martinotti10, Ornella Campese10, Federica Fiori10, Marco Lorusso10, Lucia Di Capro10, Daniela Viceconte10, Valerio Mancini10, Francesco Suraniti22, Maria Salvina Signorelli22, Eugenio Rossi23, Pasqualino Lupoli23, Marco Menchetti24, Laura Terzi25, Marianna Boso26, Paolo Risaro27, Giuseppe De Paoli27, Cristina Catania27, Ilaria Tarricone28, Valentina Caretto28, Viviana Storbini28, Roberta Emiliani28, Beatrice Balzarro28, Giuseppe Carrà6, Francesco Bartoli6, Tommaso Tabacchi6, Roberto Nava6, Adele Bono6, Milena Provenzi6, Giulia Brambilla6, Flora Aspesi6, Giulia Trotta6, Martina Tremolada6, Gloria Castagna6, Mattia Bava6, Enrica Verrengia6, Sara Lucchi6, Maria Ginevra Oriani29, Michela Barchiesi29, Monica Pacetti30, Andrea Aguglia3,4, Andrea Amerio3,4, Mario Amore3,4, Gianluca Serafini3,4, Laura Rosa Magni31, Giuseppe Rossi31, Rossella Beneduce31, Giovanni Battista Tura31, Laura Laffranchini31, Daniele Mastromo32, Farida Ferrato32, Francesco Restaino32, Emiliano Monzani32, Matteo Porcellana32, Ivan Limosani32, Lucio Ghio33, Maurizio Ferro33, Vincenzo Fricchione Parise34, Giovanni Balletta34, Lelio Addeo34, Elisa De Vivo34, Rossella Di Benedetto34, Federica Pinna35, Bernardo Carpiniello35, Mariangela Spano10, Marzio Giacomin10, Damiano Pecile36, Chiara Mattei37, Elisabetta Pascolo Fabrici38, Sofia Panarello38, Giulia Peresson38, Claudio Vitucci38, Tommaso Bonavigo38, Monica Pacetti30, Giovanni Perini5, Filippo Boschello5, Stefania Strizzolo39, Francesco Gardellin39, Massimo di Giannantonio10, Daniele Moretti40, Carlo Fizzotti40, Edoardo Cossetta40, Luana Di Gregorio41, Francesca Sozzi41, Giancarlo Boncompagni28, Daniele La Barbera42, Giuseppe Colli42, Sabrina Laurenzi43, Carmela Calandra22, Maria Luca22.

Affiliations

11Psychiatric Unit, Department of Health Sciences, University ‘Magna Graecia’, Catanzaro, Italy.

12Mental Health Department, USL Toscana sudest-Siena, Siena, Italy.

13Division of Psychiatry, Department of Molecular Medicine, University of Siena, Siena, Italy.

14Mental Health Department, USL Toscana sudest-Grosseto, Grosseto, Italy.

15Integrated Department of Mental Health and Pathological Addictions, Ferrara, Italy.

16Department of Mental Health, Ferrara, Italy.

17Mental health Department, ULSS7 Pedemontana-Treviso, Treviso, Italy.

18Mental Health Department, ULSS6 Euganea, Padova, Italy.

19Department of Medicine and Surgery, Section of Psychiatry, University of Insubria, Varese, Italy.

20Università degli Studi dell’Insubria, Dipartimento di Salute Mentale e Dipendenze-ASST Settelaghi Varese, Varese, Italy.

21Mental Health Department, USL Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy.

22Department of Mental Health, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria “Policlinico - Vittorio Emanuele”, Catania, Italy.

23Mental Health Department, USL Reggio Emilia, Reggio Emilia, Italy.

24Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

25Department of Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences DIBINEM, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy.

26Department of Applied Health and Behavioral Sciences, Section of Psychiatry, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy.

27Department of Mental Health, ASST Pavia, Pavia, Italy.

28Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, Bologna University, Italy.

29Department of Mental Health, ASUR Marche, Ancona, Italy.

30Department of Mental Health, USL Forlì, Forlì, Italy.

31Unit of Psychiatry, St. John of God Clinical Research Centre, Brescia, Italy.

32Dipartimento Salute Mentale e Dipendenze, ASST Grande Ospedale Metropolitano Niguarda Milano, Milano, Italy.

33Department of Neuroscience, Ophthalmology and Genetics, Psychiatry Section, University of Genoa, Genoa, Italy.

34Department of Mental Health, ASL Avellino, Avellino, Italy.

35Section of Psychiatry, Department of Medical Sciences and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Italy.

36Department of Mental Health, ASST Mantova, Mantova, Italy.

37Centro di salute mentale Fermo, ASL Unica Regionale Marche, Fermo, Italy.

38Department of Mental Health, Azienda Sanitaria Universitaria Giuliano Isontina, Trieste, Italy.

39Department of Mental Health, ULSS 6 Vicenza, Vicenza, Italy.

40Departmen of Mental Health, ASL2 @Savonese@, Savona, Italy.

41Department of Mental Health “ Val d’Adige, Valle dei Laghi, Vallagarina e Altipiani Cimbri”, ASSP Trento, Trento, Italy.

42Department of Experimental Biomedicine and Clinical Neuroscience, University of Palermo, Palermo, Italy.

43Department of Mental Health, Civitanova Marche Hospital, ASUR Marche, Civitanova Marche, Italy.

Authors’ contributions

A.D’A. coordinated local recruitment at his site, designed this substudy and wrote the manuscript, A. A. coordinated local recruitment at his site and contributed to the first draft of the manuscript, C.B. designed the STAR Network Depot study, F.B. and G.C. coordinated local recruitment at their site, M.C. recruited participants at her site, S.C. and E.G.O. recruited participants at their site and ran statistical analyses, C.Z. managed the literature search and prepared Tables 1-3, G. M and G.O. coordinated local recruitment at their site. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The STAR Network Depot Study was conducted independently of industry funding or support.

Availability of data and materials

The full dataset is available from the Dryad Digital Repository, doi:10. 5061/dryad.q49p6d8.

Declarations

Competing of interests

Giovanni Martinotti has been a consultant and/or a speaker and/or has received research grants from Angelini, Doc Generici, Janssen, Lundbeck, Otsuka, and Pfizer. Edoardo G. Ostinelli has received research and consultancy fees from Angelini Pharma. The other authors declare no competing interests that are directly relevant to the content of this article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committee of the coordinating centre (Ethics Committee for Clinical Trials of the Provinces of Verona and Rovigo, protocol n. 57622 of the 09/12/2015) and of each participating centre. Participants provided signed informed consent for voluntary participation. All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Armando D’Agostino, Email: armando.dagostino@unimi.it.

STAR Network Depot Investigators:

Corrado Barbui, Michela Nosè, Marianna Purgato, Giulia Turrini, Giovanni Ostuzzi, Maria Angela Mazzi, Davide Papola, Chiara Gastaldon, Samira Terlizzi, Federico Bertolini, Alberto Piccoli, Mirella Ruggeri, Pasquale De Fazio, Fabio Magliocco, Mariarita Caroleo, Gaetano Raffaele, Armando D’Agostino, Edoardo Giuseppe Ostinelli, Margherita Chirico, Simone Cavallotti, Emilio Bergamelli, Caroline Zangani, Claudio Lucii, Simone Bolognesi, Sara Debolini, Elisa Pierantozzi, Francesco Fargnoli, Maria Del Zanna, Alessandra Giannini, Livia Luccarelli, Alberto De Capua, Pasqua Maria Annese, Massimiliano Cerretini, Fiorella Tozzi, Nadia Magnani, Giuseppe Cardamone, Francesco Bardicchia, Edvige Facchi, Federica Soscia, Spyridon Zotos, Bruno Biancosino, Filippo Zonta, Francesco Pompei, Camilla Callegari, Daniele Zizolfi, Nicola Poloni, Marta Ielmini, Ivano Caselli, Edoardo Giana, Aldo Buzzi, Marcello Diurni, Anna Milano, Emanuele Sani, Roberta Calzolari, Paola Bortolaso, Marco Piccinelli, Sara Cazzamalli, Gabrio Alberini, Silvia Piantanida, Chiara Costantini, Chiara Paronelli, Angela Di Caro, Valentina Moretti, Mauro Gozzi, Chiara D’Ippolito, Silva Veronica Barbanti, Papalini Alessandro, Mariangela Corbo, Giovanni Martinotti, Ornella Campese, Federica Fiori, Marco Lorusso, Lucia Di Capro, Daniela Viceconte, Valerio Mancini, Francesco Suraniti, Maria Salvina Signorelli, Eugenio Rossi, Pasqualino Lupoli, Marco Menchetti, Laura Terzi, Marianna Boso, Paolo Risaro, Giuseppe De Paoli, Cristina Catania, Ilaria Tarricone, Valentina Caretto, Viviana Storbini, Roberta Emiliani, Beatrice Balzarro, Giuseppe Carrà, Francesco Bartoli, Tommaso Tabacchi, Roberto Nava, Adele Bono, Milena Provenzi, Giulia Brambilla, Flora Aspesi, Giulia Trotta, Martina Tremolada, Gloria Castagna, Mattia Bava, Enrica Verrengia, Sara Lucchi, Maria Ginevra Oriani, Michela Barchiesi, Monica Pacetti, Andrea Aguglia, Andrea Amerio, Mario Amore, Gianluca Serafini, Laura Rosa Magni, Giuseppe Rossi, Rossella Beneduce, Giovanni Battista Tura, Laura Laffranchini, Daniele Mastromo, Farida Ferrato, Francesco Restaino, Emiliano Monzani, Matteo Porcellana, Ivan Limosani, Lucio Ghio, Maurizio Ferro, Vincenzo Fricchione Parise, Giovanni Balletta, Lelio Addeo, Elisa De Vivo, Rossella Di Benedetto, Federica Pinna, Bernardo Carpiniello, Mariangela Spano, Marzio Giacomin, Damiano Pecile, Chiara Mattei, Elisabetta Pascolo Fabrici, Sofia Panarello, Giulia Peresson, Claudio Vitucci, Tommaso Bonavigo, Monica Pacetti, Giovanni Perini, Filippo Boschello, Stefania Strizzolo, Francesco Gardellin, Massimo di Giannantonio, Daniele Moretti, Carlo Fizzotti, Edoardo Cossetta, Luana Di Gregorio, Francesca Sozzi, Giancarlo Boncompagni, Daniele La Barbera, Giuseppe Colli, Sabrina Laurenzi, Carmela Calandra, and Maria Luca

References

- 1.Huhn M, Nikolakopoulou A, Schneider-Thoma J, Krause M, Samara M, Peter N, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 32 oral antipsychotics for the acute treatment of adults with multi-episode schizophrenia: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet. 2019;394(10202):939–951. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31135-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindström L, Lindström E, Nilsson M, Höistad M. Maintenance therapy with second generation antipsychotics for bipolar disorder - a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2017;213:138–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maher AR, Theodore G. Summary of the comparative effectiveness review on off-label use of atypical antipsychotics. J Manag Care Pharm. 2012;18(Suppl 5B):S1–20. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2012.18.S5-B.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhou X, Keitner GI, Qin B, et al. Atypical antipsychotic augmentation for treatment-resistant depression: a systematic review and network Meta-analysis. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;18(11):pyv060. doi: 10.1093/ijnp/pyv060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paolini E, Mezzetti FA, Pierri F, Moretti P. Pharmacological treatment of borderline personality disorder: a retrospective observational study at inpatient unit in Italy. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2017;21(1):75–79. doi: 10.1080/13651501.2016.1235202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hui CLM, Lam BST, Lee EHM, et al. A systematic review of clinical guidelines on choice, dose, and duration of antipsychotics treatment in first- and multi-episode schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2019;31(5–6):441–459. doi: 10.1080/09540261.2019.1613965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Driessen J, Baik SH, Zhang Y. Trends in off-label use of second-generation antipsychotics in the Medicare population from 2006 to 2012. Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67:898–903. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirschner M, Theodoridou A, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Patients’ and clinicians’ attitude towards long-acting depot antipsychotics in subjects with a first episode of psychosis. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2013;3(2):89–99. doi: 10.1177/2045125312464106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keramatian K, Chakrabarty T, Yatham LN. Long-acting injectable second-generation/atypical antipsychotics for the management of bipolar disorder: a systematic review. CNS Drugs. 2019;33(5):431–456. doi: 10.1007/s40263-019-00629-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aguglia A, Serafini G, Nebbia J, et al. Off-label use of second-generation antipsychotics in borderline personality disorder: a survey of Italian psychiatrists. J Personal Disord. 2019;33:445. doi: 10.1521/pedi_2019_33_445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salvi V, Cerveri G, Aguglia A, et al. Off-label use of second generation antipsychotics in bipolar disorder: a survey of Italian psychiatrists. J Psychiatr Pract. 2019;25(4):318–327. doi: 10.1097/PRA.0000000000000405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostuzzi G, Mazzi MA, Terlizzi S, et al. Factors associated with first- versus second-generation long-acting antipsychotics prescribed under ordinary clinical practice in Italy. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201371. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morosini PL, Casacchia M. Traduzione italiana della Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, versione 4.0 ampliata (BPRS 4.0) Riv Riabil Psichiatr Psicosociale III. 1995;3:199–228. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zanello A, Berthoud L, Ventura J, Merlo MC. The brief psychiatric rating scale (version 4.0) factorial structure and its sensitivity in the treatment of outpatients with unipolar depression. Psychiatry Res. 2013;210(2):626–633. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leucht S, Kane JM, Kissling W, Hamann J, Etschel E, Engel R. Clinical implications of brief psychiatric rating scale scores. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:366–371. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.4.366.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shafer A. Meta-analysis of the brief psychiatric rating scale factor structure. Psychol Assess. 2005;17:324–335. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kemp R, Hayward P, Applewhaite G, et al. Compliance therapy in psychotic patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1996;312:345–349. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7027.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi A, Arduini L, de Cataldo S, Stratta P. Subjective response to neuroleptic medication. A validation study of the Italian version of the drug attitude inventory (DAI) Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2001;10:107. doi: 10.1017/S1121189X00005182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartoli F, Ostuzzi G, Crocamo C, Corbo M, D’Agostino A, Martinotti G, et al. Clinical correlates of paliperidone palmitate and aripiprazole monohydrate prescription for subjects with schizophrenia spectrum disorders: findings from the STAR network depot study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;35(4):214–220. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5. Washington, DC: Author; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 21.StataCorp . Stata statistical software: release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castillo-Carniglia A, Keyes KM, Hasin DS, Cerdá M. Psychiatric comorbidities in alcohol use disorder. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(12):1068–1080. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30222-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boyce P, Irwin L, Morris G, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics as maintenance treatments for bipolar disorder-a critical review of the evidence. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20(Suppl 2):25–36. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tohen M, Goldberg JF, Hassoun Y, et al. Identifying profiles of patients with bipolar I disorder who would benefit from maintenance therapy with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4):OT19046AH1. doi: 10.4088/JCP.OT19046AH1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riecher-Rössler A. Sex and gender differences in mental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(1):8–9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30348-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.ten Have M, Verheul R, Kaasenbrood A, et al. Prevalence rates of borderline personality disorder symptoms: a study based on the Netherlands mental health survey and incidence Study-2. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:249. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0939-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perlini C, Bellani M, Besteher B, Nenadić I, Brambilla P. The neural basis of hostility-related dimensions in schizophrenia. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2018;27(6):546–551. doi: 10.1017/S2045796018000525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dick DM, Smith G, Olausson P, et al. Understanding the construct of impulsivity and its relationship to alcohol use disorders. Addict Biol. 2010;15(2):217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2009.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mohr P, Knytl P, Voráčková V, et al. Long-acting injectable antipsychotics for prevention and management of violent behaviour in psychotic patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2017;71(9):10. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McEvoy JP, Byerly M, Hamer RM, et al. Effectiveness of paliperidone palmitate vs haloperidol decanoate for maintenance treatment of schizophrenia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311(19):1978–1987. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.4310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen J, Jensen SO, Friis RB, et al. Comparative effectiveness of risperidone long-acting injectable vs first-generation antipsychotic long-acting injectables in schizophrenia: results from a nationwide, retrospective inception cohort study. Schizophr Bull. 2015;41:627–636. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leucht S, Huhn M, Davis JM. Should ‘typical’, first-generation antipsychotics no longer be generally used in the treatment of schizophrenia? Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2021. 10.1007/s00406-021-01335-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 33.Stone JM, Roux S, Taylor D, Morrison PD. First-generation versus second-generation long-acting injectable antipsychotic drugs and time to relapse. Ther Adv Psychopharm. 2018;8(12):333–336. doi: 10.1177/2045125318795130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patel R, Chesney E, Taylor M, Taylor D, McGuire P. Is paliperidone palmitate more effective than other long-acting injectable antipsychotics? Psychol Med. 2018;48:1616–1623. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization . International classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th Revision) 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The full dataset is available from the Dryad Digital Repository, doi:10. 5061/dryad.q49p6d8.