Significance

Biomolecular condensates are highly diverse systems spanning not only homogeneous liquid droplets but also gels, glasses, and even multiphase architectures that contain various coexisting liquid-like and/or gel-like inner phases. Multiphase architectures form when the different biomolecular components in a multicomponent condensate establish sufficiently imbalanced intermolecular forces to sustain different coexisting phases. While such a requirement seems, at first glance, impossible to fulfil for a condensate formed exclusively of chemically identical proteins (i.e., single component), our simulations predict conditions under which this may be possible. During condensate aging, a sufficiently large imbalance in intermolecular interactions can emerge intrinsically from the accumulation of protein structural transitions—driving even single-component condensates into nonequilibrium liquid-core/gel-shell or gel-core/liquid-shell multiphase architectures.

Keywords: biomolecular condensates, multiscale modeling multiphase condensates, liquid–liquid phase separation, hollow condensates

Abstract

Phase-separated biomolecular condensates that contain multiple coexisting phases are widespread in vitro and in cells. Multiphase condensates emerge readily within multicomponent mixtures of biomolecules (e.g., proteins and nucleic acids) when the different components present sufficient physicochemical diversity (e.g., in intermolecular forces, structure, and chemical composition) to sustain separate coexisting phases. Because such diversity is highly coupled to the solution conditions (e.g., temperature, pH, salt, composition), it can manifest itself immediately from the nucleation and growth stages of condensate formation, develop spontaneously due to external stimuli or emerge progressively as the condensates age. Here, we investigate thermodynamic factors that can explain the progressive intrinsic transformation of single-component condensates into multiphase architectures during the nonequilibrium process of aging. We develop a multiscale model that integrates atomistic simulations of proteins, sequence-dependent coarse-grained simulations of condensates, and a minimal model of dynamically aging condensates with nonconservative intermolecular forces. Our nonequilibrium simulations of condensate aging predict that single-component condensates that are initially homogeneous and liquid like can transform into gel-core/liquid-shell or liquid-core/gel-shell multiphase condensates as they age due to gradual and irreversible enhancement of interprotein interactions. The type of multiphase architecture is determined by the aging mechanism, the molecular organization of the gel and liquid phases, and the chemical makeup of the protein. Notably, we predict that interprotein disorder to order transitions within the prion-like domains of intracellular proteins can lead to the required nonconservative enhancement of intermolecular interactions. Our study, therefore, predicts a potential mechanism by which the nonequilibrium process of aging results in single-component multiphase condensates.

Cells compartmentalize their interiors and regulate critical biological functions using both membrane-bound organelles and membraneless biomolecular condensates (1–3). Condensates are ubiquitous mesoscopic assemblies of biomolecules that demix from the cytoplasm or nucleoplasm through liquid–liquid phase separation (1–5). A dominant factor that enables biomolecules to phase separate is their multivalency: their ability to form multiple weak associative interactions (6–8). Although not always present among phase-separating proteins (9), intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs)—often characterized by amino acid sequences of low complexity termed low-complexity domains (10, 11)—have emerged as important contributors to the multivalency and phase separation capacity of many naturally occurring proteins (2, 3, 6). When low-complexity domains have a high aromatic content, such as that found in prion-like domains (PLDs) (12, 13), they can aggregate (fibrillation) and form amyloids (10, 11, 14). Consistently, protein condensates that contain PLDs—for instance, the RNA-binding proteins Fused in Sarcoma (FUS), Trans-activation response DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43), and heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNPA1)—can undergo a further phase transition from functional liquid-like states to less dynamic reversible hydrogel structures or even irreversible gel-like states sustained by fibrillar aggregates (11, 15–23). Transitions from liquid-like condensates to gel-like structures are implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia (24–26).

Within both liquid-like and gel-like condensates, proteins interconnect forming percolated networks (27, 28). However, gels can be distinguished from liquids by the prevalence of long-lived interprotein interactions, which confer local rigidity to the network (27, 29). The loss of the liquid-like character of a condensate over time [i.e., during aging (15, 25)] can be modulated by amino acid sequence mutations, posttranslational modifications, application of mechanical forces, and protein structural transitions, among many other factors (15–17, 20–22, 30–32). These factors are expected to, directly or indirectly, increase the proportion of long-lived protein contacts within the condensate, which gives rise to complex mesoscale properties and network rigidity (27, 33).

Besides being highly diverse in terms of their material properties, condensates also vary significantly in their internal architectures (34). Multicomponent condensates can present various internal coexisting phases. The nucleolus (35), paraspeckles (35–37), and stress granules (38, 39) are all examples of hierarchically organized condensates with multiple coexisting phases or layers. Intranuclear droplets combining a dense liquid spherical shell of acetylated TDP-43—with decreased RNA-binding affinity—and an internal liquid core rich in Heat Shock Protein 70 (HSP70) chaperones were recently observed (40). Multicomponent multiphase condensates can also present internal low-density “bubbles” or a “hollow” space surrounded by an outer denser phase (41–43). Examples of these include the germ granules in Drosophila (41), the condensates formed from intracellular overexpression of TDP-43 (42), and in vitro RNA–protein vesicle-like condensates (43).

The multiphase behavior of condensates has been recapitulated in vitro: for instance, in the liquid-core/gel-shell condensates formed by the Lge1 and Bre1 proteins (44), different multiphasic complex coacervates (45, 46), and multilayered RNA–protein systems (47, 48). In all these cases, the emergence of a multilayered or multiphase organization is connected to the diversity in the properties of the biomolecular components within these condensates (28, 44, 46, 49). Physicochemical diversity is key as it allows subsets of components to establish preferential interactions with one another, leading to segregation into multiple layers inside the condensates, which are typically ordered according to their relative interfacial free energies (50). Indeed, simulations and mean-field theory have shown that multicomponent mixtures of species with sufficiently different valencies and/or binding affinities (51) are likely to segregate into multiple coexisting liquid phases with different compositions (52) or form multilayered architectures (46, 49, 50). For instance, simulations of a minimal coarse-grained model recently showed that the diversity in the network of interactions in mixtures of unphosphorylated and phosphorylated FUS proteins can give rise to multiphase condensates (53). In agreement with this idea, competing interactions among protein–RNA networks have been shown to drive the formation of multiphase condensates with complex material properties (51). Experiments and simulations have further demonstrated that the different condensed liquid phases within multiphase condensates are hierarchically organized according to their relative surface tensions, critical parameters, viscosities, and densities (35, 46, 49, 50). Motivated by these observations, here we explore the fundamental question of whether or not it is possible for single-component condensates to transition into a multiphase architecture as they age. We conceptualize condensate aging as a nonequilibrium process where the intermolecular forces among proteins exhibit gradual nonconservative changes over time.

Progressive dynamical arrest of single-component condensates has been observed in vitro and in cells for proteins with PLDs marked by low-complexity aromatic-rich kinked segments (LARKS) (8, 10–20, 54, 55). In these cases, formation of interprotein β-sheets by LARKS peptides drives gradual fibrillation at the high protein concentrations present within condensates (18, 19, 23). In such a situation, an imbalance in the intermolecular forces among proteins inside the condensate is introduced and accumulates dynamically, resulting in nonequilibrium behavior. That is, rather than permanently establishing only weak, transient attractive interactions, some LARKS begin to assemble into interlocking structures, which are strengthened due to the contribution of multiple hydrogen bonds and π–π interactions, leading to the formation of crossed β-sheet amyloid structures (20). Such a disorder to order transition within condensates highlights how subtle changes in the local behavior of proteins can result in large-scale transformations of the mesoscale condensate structure.

Here, we investigate conditions that can dynamically alter the balance of intermolecular forces among proteins within single-component homogeneous condensates, driving them out of equilibrium and yielding multiphase architectures. To do so, we develop a multiscale modeling approach that allows us to connect multiple important scales of condensate formation, growth, equilibration, and nonequilibrium maturation. Our approach combines atomistic simulations of peptides with sequence-dependent coarse-grained simulations of protein condensates and a minimal model for protein condensates that age progressively. The minimal protein model is coupled to a dynamical nonequilibrium algorithm that mimics the progressive accumulation of interprotein crossed β-sheets during aging. As a proof of concept, we focus on the naturally occurring phase-separating protein FUS because it exhibits a liquid to gel transition during aging (15, 30) and contains LARKS regions that can undergo a disorder to order transition to form β-sheet–rich structures. Our simulations predict that FUS condensates can transition from equilibrium homogeneous condensed liquid phases into nonequilibrium liquid-core/gel-shell multiphase architectures due to the gradual enhancement in local protein interactions. Such enhancement can be provided, for instance, by an increase in cross–β-sheet content within LARKS regions of FUS proteins. Our simulations also demonstrate that the molecular organization of the gel-like phase (e.g., whether the arrested state exposes more or less hydrophobic regions of the protein to the surface) significantly influences the relative interfacial free energy of the various protein phases; hence determining the ordering of the various phases within multiphase condensates. Furthermore, the molecular organization is also influenced by the aging mechanism (e.g., which protein regions transition to form long-lived bonds dictates the preferential localization of residues that accumulate at the core or the surface of the gel phase). These findings highlight how variations in the binding strength among proteins due, for instance, to secondary structural changes can result in nonequilibrium arrested multiphase condensates in single-component protein systems. These results further corroborate the idea that PLDs can act as modulators of prion-like protein phase behavior and thereby, can tune collective interactions among adhesive amino acid motifs that result in condensate structural transformations that are observable at the mesoscale (12, 13).

Results and Discussion

Multiscale Model of Single-Component Multiphase Condensates.

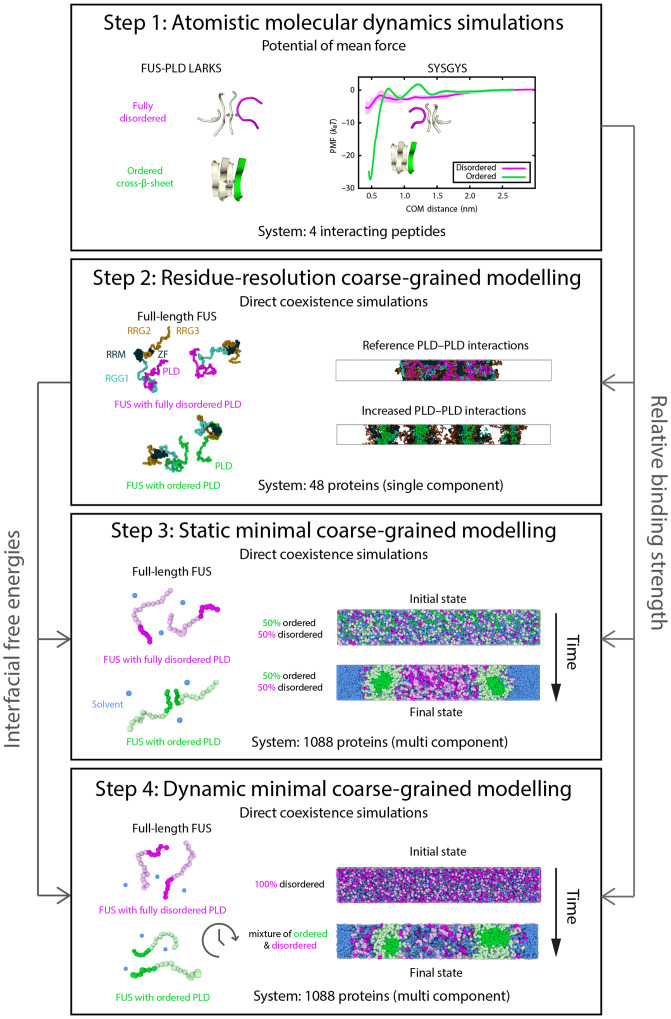

To provide mechanistic insights into the physical and molecular determinants that could drive single-component condensates to age into multiphase architectures, we designed a multiscale simulation approach that allows us to understand how subtle atomistic details of interacting proteins in solution impact the thermodynamic mechanisms of condensate formation and aging (Fig. 1). Molecular simulations are powerful in dissecting the mechanisms, driving forces, and kinetics of phase separation and providing structural details of biomolecules within condensates (56, 57). All-atom and coarse-grained modeling approaches are now well-established tools used in conjunction with experiments to investigate biomolecular phase separation (28, 58–62). Our multiscale modeling strategy leverages advantages of these two levels of modeling. 1) Atomistic representations are used to describe the effects of chemical composition and protein structure in modulating interprotein interactions, albeit in relatively small systems, and 2) coarse-grained models are developed and applied to consistently extrapolate such effects into the emergence of collective phenomena, such as condensate formation and aging. Specifically, our approach integrates atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of interacting peptides (Step 1 in Fig. 1); amino acid–resolution coarse-grained simulations of protein condensates with implicit solvent [i.e., using our Mpipi protein model (63), which describes with near-quantitative accuracy the phase behavior of proteins] (Step 2 in Fig. 1); and a bespoke minimal coarse-grained model of protein condensates, in explicit solvent, that undergo aging over time. In addition, to describe the nonequilibrium process of condensate aging, we develop a dynamical algorithm that introduces dissipation through nonconservative interprotein interactions. Specifically, the dynamical algorithm considers the gradual accumulation of stronger interprotein bonds and local rigidification of the interacting protein segments due to interprotein disorder to order transitions inside the condensate (Steps 3 and 4 in Fig. 1). While our approach is fully transferable to other protein systems, as a proof of concept, we use it to investigate the aging behavior of single-component FUS condensates.

Fig. 1.

Visual summary of the multiscale computational approach employed in this work and divided into four steps explaining how the information from each step flows into the other steps. (Step 1) Atomistic PMF calculations (using umbrella sampling) are performed (for the different FUS short peptides that can undergo disorder to order transitions) to compare the free energy of binding when the sequences remain disordered vs. when they are structured. (Step 2) With the information of the relative binding strength obtained in step 1, the Mpipi coarse-grained model (63) is used to investigate the effect of increased PLD–PLD interactions in the interfacial free energy, molecular contacts, and droplet organization of FUS condensates. We find that strengthened PLD–PLD interactions drive the exposure of positively charged RGG2 and RGG3 domains to the droplet interface, thus lowering their surface tension. (Step 3) We develop a tailored minimal protein model to investigate FUS condensation in much larger system sizes (i.e., more than 20 times larger than with the Mpipi model). We design our tailored model based on the results from steps 1 and 2 and observe the formation of steady-state multiphase FUS architectures. Finally in step 4, we design a dynamic algorithm where instead of starting from a fixed concentration of structured vs. disordered FUS proteins, the disorder to order transitions spontaneously emerge over time depending on the protein concentration environment, and we swap the identity of proteins from being disordered to structured (with the same parameters as in step 3) according to the PLD local coordination number. With this approach, nonequilibrium multiphase condensates are also observed, consistent with findings of step 3.

A Disorder to Order Structural Transition Diversifies the Interactions among Chemically Identical FUS Proteins.

One of the proposed mechanisms used to explain aging of RNA-binding proteins, like FUS, is their ability to undergo structural transitions within their LARKS. It has been observed that LARKS within the PLD of FUS (e.g., regions SYSGYS, SYSSYGQS, and STGGYG) can form pairs of kinked cross–β-sheets, which assemble into ladders and yield reversible fibrils that sustain hydrogels (19). Peptides at each step of the LARKS ladder form hydrogen bonds with adjacent peptides in the next step of the ladder. In addition, stacking of aromatic side chains stabilizes both the ladder and the individual β-sheets at each step. We, therefore, hypothesized that the formation of cross–β-sheets among these critical LARKS in FUS–PLD could introduce sufficient physicochemical diversity into single-component FUS condensates to induce a multiphase organization.

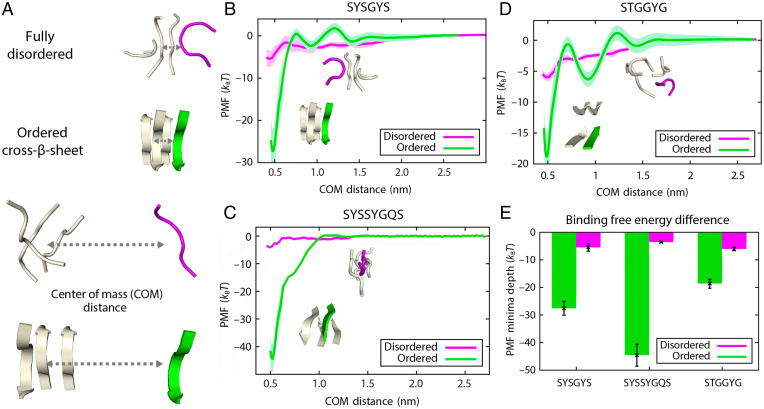

To investigate this hypothesis, we first use atomistic MD simulations to compute the differences in interaction strength of FUS–PLD LARKS due to disorder to order transitions (Step 1 in Fig. 1). As done previously for Aβ-peptides (64), we perform atomistic umbrella sampling MD simulations to quantify the changes in the relative binding strengths (or potential of mean force [PMF]) among LARKS peptides when they are disordered vs. when they stack to form the kinked β-sheet structures resolved crystallographically (Fig. 2A) (19). Following ref. 65, we compute the intermolecular binding strengths for three different FUS LARKS sequences (SYSGYS, SYSSYGQS, STGGYG) using two different force fields: a99SB-disp (66) (Fig. 2) and CHARMM36m (67) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). For each case, we calculate the free energy cost of dissociating a single peptide from a system containing four identical peptides. A total of four peptides is the smallest system size that considers the energetic cost of breaking both the step–step interactions and the peptide–peptide interactions within one step of the LARKS ladders (i.e., there are two interacting peptides at each step of the ladder) upon single-peptide dissociation.

Fig. 2.

The disorder to order transition strengthens intermolecular interactions among FUS LARKS. (A) Schematic of atomistic PMF simulations of LARKS-forming peptides in their disordered (magenta) and ordered states (green). The starting configurations for all simulations consisted of four stacked peptides. PMFs are calculated by estimating the free energy needed to remove one peptide (the “dissociating” peptide) from the stack as a function of the center of mass (COM) distance. The example shown is the peptide SYSGYS (Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID code 6BWZ). (B–D) Plots of PMF vs. COM for homotypic pairs of FUS LARKS-forming peptides SYSGYS (PDB ID code 6BWZ), SYSSYGQS (PDB ID code 6BXV), and STGGYG (PDB ID code 6BZP), respectively, before (magenta) and after (green) undergoing the disorder to order structural transition. For the SYSGYS and STGGYG ordered systems, the PMFs display two barriers each (i.e., each shows a first barrier at a COM distance of around 0.75 nm and a second barrier at a COM distance of around 1.25 nm), which are contributed by the desolvation energy (primary and secondary shells) and the steric repulsion among the dissociating peptide and the remaining stacked peptides. In contrast, independently of the force field used (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), the SYSSYGQS ordered system does not present noticeable steric repulsion among the dissociation path, and consistently, it does not show energetic barriers at increasing values of the COM distance. Statistical errors (mean ± SD) are shown as bands obtained by bootstrapping the results from n = 5 independent simulations. (E) Variation in the free energy minimum (as obtained from the profiles in B–D).

Independently of the force field used, the energetic cost of dissociating one of the peptides is approximately four to eight times larger when these display canonical stacking, forming kinked β-sheet structures with two LARKS per step, vs. when they are disordered. That is, when the four LARKS remain fully disordered, their binding interaction strengths are weak (∼2 to 8 ), which suggests that thermal fluctuations can frequently break these interactions (Fig. 2 B–D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). In contrast, when the LARKS peptides form β-sheets, their interaction strength increases to 15 to 45 in total, depending on the LARKS sequence (Fig. 2 B–D and SI Appendix, Fig. S1). The increase is most noticeable in the SYSSYGQS system, likely due to the presence of glutamine (Q; i.e., within the β-sheet structure, Q exhibits an ideal orientation to act as an additional sticker by interacting strongly with both serine [S] and tyrosine [Y]) (68). A summary of the relative interaction strengths for the three LARKS sequences is provided in Fig. 2E and SI Appendix, Fig. S1.

Overall, our atomistic simulations suggest that the intermolecular interactions among PLDs within FUS condensates would be significantly strengthened upon formation of LARKS fibrillar-like ladders. However, in agreement with experiments, we find that the strength of interaction among such ordered LARKS is only sufficiently strong to sustain reversible hydrogels that dissolve upon salt treatment or heating but not irreversible amyloids (19). Irreversible amyloid fibrils would require larger binding energies (e.g., of the order of 50 to 80 ) (19, 64, 69).

Based on the striking differences in the binding strength between FUS LARKS with β-sheets and those where the peptides remained fully disordered, we next investigated if a binary protein mixture composed of two distinct FUS conformational ensembles (i.e., with ordered vs. with disordered LARKS) within the same condensate might give rise to a multiphase condensate morphology. In other words, we asked if two-phase coexistence within a single-component FUS condensate could emerge when a fraction of the FUS proteins has transitioned from having fully disordered PLDs to having PLDs that form interprotein cross–β-sheets.

Strengthening of PLD Interactions Dramatically Transforms the Molecular Organization of FUS Condensates.

To determine the mesoscale implications of strengthening selected interprotein bonds due, for instance, to an intermolecular disorder to order transition, we perform amino acid–resolution coarse-grained simulations. In particular, we ask if such strengthening can give rise to FUS condensates with sufficiently different mesoscale properties from those of FUS condensates with standard interactions.

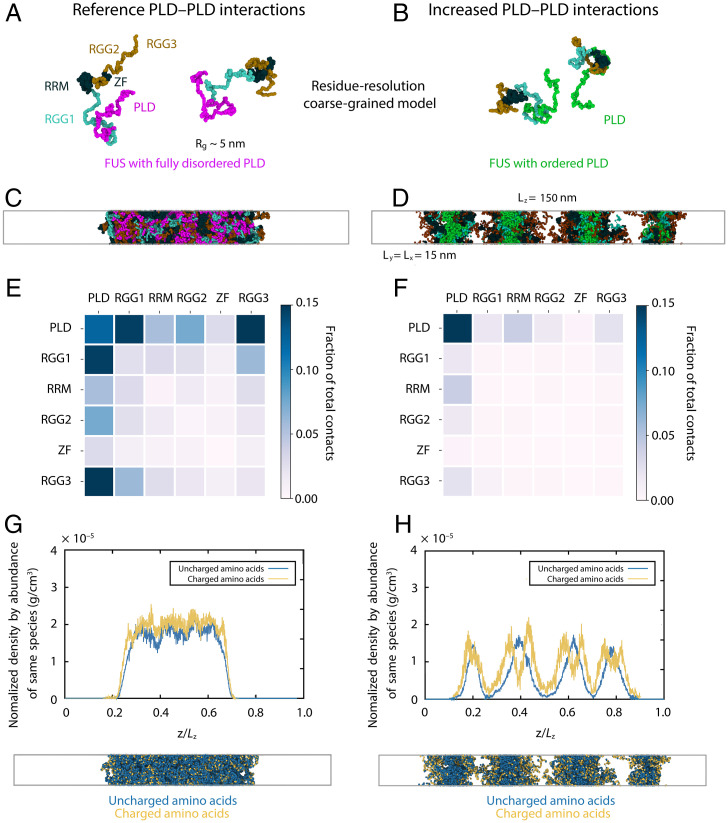

First, we use our Mpipi residue-resolution coarse-grained model (63) (Step 2 in Fig. 1), which recapitulates experimental phase separation propensities of FUS mutants (10). With Mpipi, we characterize the molecular organization of single-component FUS condensates with standard (i.e., fully disordered and weakly interacting) PLD regions. Next, to probe the differences in the phase behavior of FUS proteins with PLDs that establish interprotein β-sheets, we increase the PLD–PLD interactions as suggested by our atomistic PMFs. A representation of these residue-resolution coarse-grained models for FUS is shown in Fig. 3A, with the 526-residue FUS protein sectioned into its PLD region (residues 1 to 165), three disordered RGG-rich regions (RGG1: residues 166 to 267; RGG2: residues 371 to 421; and RGG3: residues 454 to 526), and two globular regions (an RNA recognition motif [RRM]: residues 282 to 371 and a zinc finger (ZF) domain: residues 422 to 453).

Fig. 3.

Strengthened PLD interactions give rise to multiphase condensate organization in coarse-grained MD simulations. (A and B) Residue-resolution coarse-grained models for FUS with fully disordered PLD (A) and with ordered PLD (i.e., with cross–β-sheet elements in the PLDs; B). Representative snapshots of FUS replicas as obtained via direct coexistence MD simulations are shown. Amino acid beads are colored according to the domains of FUS, with one bead representing each amino acid: PLD (residues 1 to 165) in magenta (A) or green (B), RGG1 (residues 166 to 284) in cyan, RGG2 (residues 372 to 422) and RGG3 (residues 454 to 526) in ochre, and RRM (residues 285 to 371) and ZF (residues 423 to 453) in dark blue. The single-protein radius of gyration (Rg) of FUS within the dilute phase (and therefore, with reference PLD–PLD interactions) at the same conditions of the rest of simulations () is also included. (C and D) Snapshots of direct coexistence simulations with reference interaction strengths among PLDs (C) and increased interactions strengths among PLDs (D). The simulation box sides included in D also apply for C, G, and H; 48 FUS proteins were included in the simulations. The color code is the same as in A and B. (E and F) Frequency of contacts between FUS domains within condensates for simulations with standard interaction strengths among PLDs (E) and increased interactions strengths among PLDs (F). Heat maps are color coded and scaled from white to dark blue. The statistical uncertainty in the fraction of molecular contacts is 0.01. (G and H) Normalized density of charged (yellow) and uncharged (blue) species across the long side of the simulation box estimated over the coarse-grained equilibrium ensemble for simulations with standard interaction strengths among PLDs (C) and increased interactions strengths among PLDs (D). Density uncertainty corresponds to 5%. The snapshots from direct coexistence simulations (Lower) are the same as in C and D but color coded according to the charge state of the amino acid residues.

For each of these coarse-grained parameterizations, we conduct residue-resolution direct coexistence simulations (70–72) of tens of interacting full-length FUS molecules and estimate the influence of modulating the intermolecular interactions among PLDs on FUS phase separation (Step 2 in Fig. 1). The direct coexistence method enables simulating a protein-enriched condensed liquid phase in contact with a protein-poor diluted liquid phase in one simulation box and thus, can determine whether a system phase separates at a given set of conditions.

Consistent with previous observations (73), FUS condensates formed by standard proteins with fully disordered PLDs display a homogeneous molecular architecture (Fig. 3 C and G) (i.e., all FUS domains are randomly positioned throughout the condensate). In contrast, FUS condensates containing strengthened PLD–PLD interactions (Fig. 3 D and H) exhibit a micelle-like heterogeneous organization with a PLD-rich hydrophobic core and a charge-rich interface (i.e., the positively charged RGG2 and RGG3 regions are effectively exposed to the solvent). As a result, the surface tension (γ) of FUS condensates with strengthened PLD–PLD interactions ( mJ/m2) is considerably lower than that of the condensates formed by standard FUS proteins ( mJ/m2). Accordingly, FUS condensates with strengthened PLD–PLD interactions can stabilize multiple droplets in the same simulation box (Fig. 3 D and H), as observed previously for condensates with a surfactant-rich interface (50).

The Presence of Distinct FUS Structural Ensembles Supports the Formation of Hollow Liquid-Core/Gel-Shell Condensates.

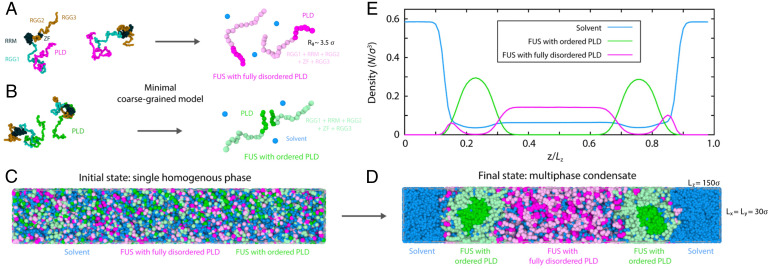

To investigate the phase behavior of a multicomponent condensate that contains both FUS proteins with fully disordered PLDs (termed “disordered” FUS herein) and FUS proteins where the PLDs form interprotein cross–β-sheets (termed “ordered” FUS herein), we developed a minimal model (Step 3 in Fig. 1). A minimal model significantly reduces the degrees of freedom of the system and hence, the computational cost while retaining essential physicochemical information. Such a reduction is required because simulations of multicomponent condensates must consider a larger number of proteins (∼103) than those of single-component systems to address the additional finite-size effects associated with approximating the overall composition of the system (i.e., the relative number of copies of each component).

In our minimal model, full-length FUS proteins are each represented as a chain of 20 beads (i.e., 6 beads for FUS–PLD and 14 beads for the RGG1, RRM, RGG2, ZF, and RGG3 regions). To distinguish between disordered and ordered FUS proteins, our minimal model considers the following three key physicochemical differences between them based on the results from our atomistic and residue-resolution simulations. 1) While disordered FUS proteins are modeled as fully flexible chains, we increase the local rigidity among PLD beads within ordered FUS proteins to mimic the structural effect of cross–β-sheet formation. 2) We parameterize the strengths of interactions among pairs of ordered and disordered FUS domains differently. In each case, we set the strength of interactions among individual FUS regions (e.g., PLD–PLD, PLD–RGG1, RGG1–RGG1, etc.) using the relative frequencies of interactions obtained in their respective residue-resolution simulations (i.e., the disordered FUS minimal model according to the contact maps of the single-component standard FUS simulations [Fig. 4A] and the ordered FUS model based on the contact maps of the single-component FUS simulations where the PLD–PLD interactions were increased based on our atomistic results [Fig. 4B]). 3) To recover the lower surface tension we observe in our residue-resolution simulations for single-component ordered FUS condensates, we assign a higher hydrophilicity to the charged-rich FUS regions (i.e., RGG1, RGG2, and RGG3 regions) than to the other FUS domains and incorporate a compatible minimal explicit solvent model. As a test, we run two separate simulations of single-component FUS condensates, one using the minimal model for ordered FUS and the other using the minimal model for disordered FUS (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). This test reveals that the minimal model is able to recapitulate both the micelle-like (for ordered FUS) and the homogeneous (for disordered FUS) condensate organizations that we predicte with the residue-resolution simulations using similar system sizes and simulation conditions (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

Fig. 4.

A disorder to order transition within PLDs drives multiphase organization in FUS condensates. (A and B) Minimal coarse-grained models for FUS with fully disordered PLDs (A) and with ordered PLDs (i.e., with cross–β-sheet elements in the PLDs; B). Representative snapshots of FUS replicas as obtained via direct coexistence MD simulations are shown. Here, one bead represents ∼26 amino acids. PLD: magenta (A) or green (B); RGG1, RRM, RGG2, ZF, and RGG3: light magenta (A) or light green (B). Solvent (water) is depicted by blue beads. The radius of gyration (Rg) of the minimal FUS coarse-grained protein in the dilute phase is ∼3.5 σ (information about reduced units is in SI Appendix). (C and D) Snapshots of direct coexistence simulations of a mixture of 50% FUS proteins with fully disordered PLDs and 50% FUS proteins with cross–β-sheet elements in their PLDs and explicit solvent. The initial state is shown in C, and the final state is in D; 1,088 FUS proteins were included in the simulations. (E) Density profile (in reduced units) of FUS species and explicit solvent across the long side of the simulation box estimated over the coarse-grained final state (as obtained in D). FUS proteins with fully disordered PLDs: magenta; FUS proteins with ordered PLDs (i.e., with kinked cross–β-sheets): green; solvent (water): blue.

Using these two minimal FUS protein models, we now perform direct coexistence simulations of a mixture of 50% disordered FUS proteins and 50% ordered FUS proteins in explicit water/solvent. By starting from a homogeneous mixed phase (Fig. 4C), the system readily demixed into a phase-separated condensate with an inhomogeneous organization (Fig. 4D). Evaluation of the density profile of the steady-state system reveals the formation of a liquid-core/gel-shell (i.e., hollow) multiphase condensate architecture. Specifically, such condensates are hierarchically organized with a low-density core) made of disordered FUS proteins, and a high-density surrounding shell composed of ordered FUS species (Fig. 4E). The lower density of the inner FUS phase with disordered PLDs also exhibits moderately higher water content. Our simulations further reveal that FUS proteins in the outer shell are less mobile than in the inner core as gauged by their reduced mean squared displacement (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). We verified that variations in the stoichiometry of the disordered FUS proteins vs. ordered FUS proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), as well as in the simulation system size and box shape (SI Appendix, Fig. S8), negligibly affect the organization of the liquid-core/gel-shell multiphase condensates. Together, our simulations predict that FUS condensates, which contain both a population of proteins that remain fully disordered and bind weakly and a population of proteins that establish strong PLD–PLD interactions (i.e., due to the ordering and stacking into kinked cross–β-sheet fibrillar-like LARKS ladders), can self-assemble into multiphase architectures.

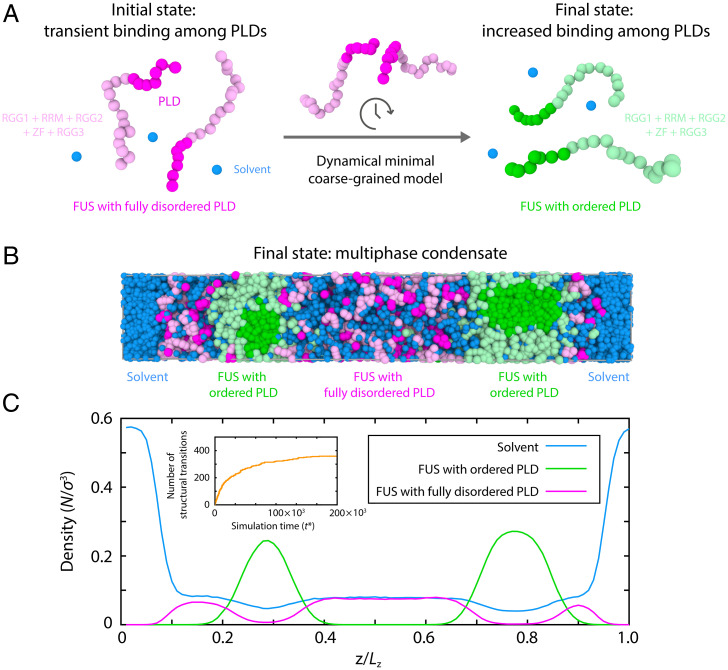

Aging Simulations Predict Multiphase Condensate Formation from Single-Component Systems.

The highly concentrated environments of biomolecular condensates may serve as seeding grounds for disorder to order transitions that occur in FUS–PLD LARKS (Step 4 in Fig. 1) or other mechanisms that produce local enhancement of interprotein interactions. To gain deeper insights into the mechanism of FUS multiphase condensate formation and aging, we next developed a dynamical algorithm that approximates the effects of the gradual accumulation of interprotein β-sheet structures in a time-dependent manner and as a function of the local protein density. Specifically, the effects considered are: strengthening of interprotein bonds, local protein rigidification, and changes in the molecular organization of the condensed phase. Rather than imposing a fixed concentration of disordered and ordered FUS proteins in the simulation a priori (as done in the previous section), this algorithm enables us to study the progressive emergence of multiphase FUS condensates during aging.

We again perform direct coexistence simulations using our minimal FUS protein model but now starting from a system containing 100% of standard FUS proteins with disordered PLDs in explicit solvent. As time progresses, our dynamical algorithm triggers disorder to order transitions within the PLD of selected FUS proteins. The structural transitions emerge when high local fluctuations of protein densities are found within the condensate (Fig. 5A). Specifically, transitions of LARKS into kinked cross–β-sheets are enforced and recapitulated by modulating the binding interaction strength of PLD–PLD interactions by a factor of eight (according to our atomistic PMF simulations) when a PLD is in close contact with four other PLDs and still possesses enough free volume around it to undergo a disorder to order structural transition (i.e., solvent mediated) (20, 74) (justification and details can be found in the SI Appendix). An important feature of this dynamic algorithm is that it allows us to explore aging as a nonequilibrium process where the strength of interprotein interactions in the system is nonconservative (i.e., transitions from the strongly-interacting ordered LARKS state back to the weakly-binding disordered state are forbidden).

Fig. 5.

An aging model predicts multiphase FUS condensates. (A) Schematic illustration of the dynamical algorithm for triggering disorder to cross–β-sheet transitions in the minimal coarse-grained model of FUS. This algorithm fosters disorder to order transitions by increasing the PLD–PLD interaction strengths by a factor of eight (according to our atomistic PMF simulations) when FUS–PLDs are in close contact with four other PLD–FUS domains and still possess enough surrounding free volume to undergo the transition into kinked cross–β-sheets. PLD: magenta or green; RGG1, RRM, RGG2, ZF, and RGG3: light magenta or light green. Solvent (water) is depicted as blue beads. (B) Snapshot of direct coexistence simulations using the dynamical algorithm at a quasi-kinetically arrested state after structural transitions have saturated. (C) Density profile (in reduced units) of FUS species and explicit solvent across the long side of the simulation box estimated over the coarse-grained quasistationary state (as obtained in B). (Inset) Number of structural transitions in FUS–PLD domains as a function of simulation time (). The plateau region was used to calculate the snapshots and density profiles in B and C, respectively. FUS proteins with fully disordered PLDs: magenta; FUS proteins with ordered PLDs (i.e., with kinked cross–β-sheet elements): green; solvent (water): blue.

Triggering the dynamic algorithm drives the initially homogeneous condensate to adopt a nonequilibrium multiphase architecture with a high-density outer shell and a low-density inner core (Fig. 5 B and C). The resulting multiphase architecture is equivalent to the one obtained in the previous section when mixing a priori ordered and disordered FUS proteins at fixed concentrations (cf. Fig. 4). Comparing the phase diagram (in the plane of reduced temperature vs. density) of standard FUS proteins (i.e., with fully disordered FUS proteins; static model) with that of FUS proteins that can age progressively over time (i.e., simulated with our dynamical algorithm) reveals only a moderate increase in the global density of the condensate upon aging but almost no change in the maximum temperature at which phase separation is observed (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Regarding the aging mechanism, our dynamic algorithm predicts an initial steep increase in the rate of disorder to order transitions for FUS inside the newly formed condensate due to the high probability of local high-density fluctuations (Fig. 5 C, Inset and phase diagram in SI Appendix, Fig. S6). Once the multiphase condensate begins to form, the rate of emergence of structural transitions decays rapidly until a quasi-dynamically arrested state is reached. The dominant factor slowing down the rate of structural transitions comes from the formation of the low-density inner core (i.e., the lower densities in such a region significantly decrease the probability that clusters of four or more peptides would form). As the multiphase architecture consolidates even further, a slight speedup to the rate of transitions comes from the increasing numbers of ordered FUS proteins that become available at the newly formed shell–core interphase. These exposed ordered proteins can target disordered proteins from the low-density phase and drive them to undergo disorder to order transitions. However, the latter speedup is frustrated by the slower dynamics of the ordered FUS proteins and by the steric barrier that FUS domains adjacent to the ordered PLD regions pose. Reduced dynamics are also observed when significant modifications to the parameter set of the dynamic algorithm controlling the emergence rate of structural transitions are applied (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

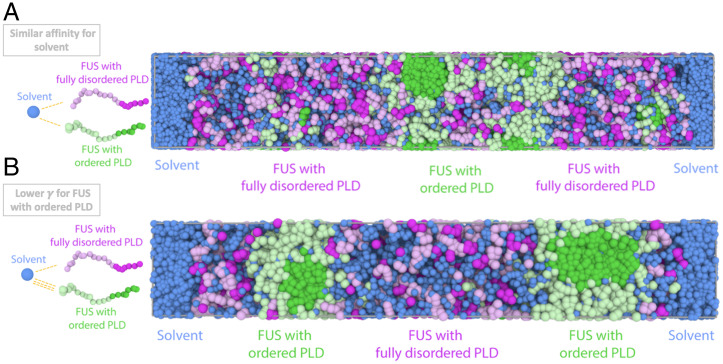

Formation of Liquid-Core/Gel-Shell vs. Gel-Core/Liquid-Shell Condensates.

While FUS forms hollow condensates (Fig. 5B)—with a liquid-core/gel-shell architecture—we reasoned that other proteins may form different steady-state multiphase architectures combining gels and liquids. Indeed, in the previous sections we show that the specific liquid-core/gel-shell architecture of FUS multiphase condensates is dictated by the amino acid sequence of FUS and the molecular organization of the various FUS domains inside its gel phase (i.e., as strong LARKS–LARKS bonds form, the charged-rich RGG regions of FUS are pushed toward the surface of the gel, making the gel more hydrophilic than the inner liquid core).

To investigate how the liquid and gel phases may organize in condensates formed by other proteins beyond FUS or in FUS undergoing a different aging mechanism, we let the surface of the gel be equally hydrophilic than that of the liquid-like condensed phase. For this, we devise a set of control simulations where we now define all domains within our minimal protein model as equally hydrophilic. Using this model (parameterization is in SI Appendix, Tables S1 and S2), we perform two types of direct coexistence simulations: 1) for a system where we mix a priori 50% of fully disordered proteins with 50% ordered proteins with structured LARKS and 2) for a system that is formed initially by 100% disordered proteins and where a protein region can dynamically undergo disorder to order transitions (as in Fig. 5). Importantly, these simulations predict that the condensates will now exhibit a nonequilibrium multiphase gel-core/liquid-shell architecture (Fig. 6A) (i.e., where the gel-like aged phase is now preferentially located in the core of the multiphase condensate and the liquid forms an outer shell around it). These simulations suggest that the specific ordering of the gel and liquid phases is determined by the relative hydrophilicity of the coexisting gel and liquid phase surfaces. Given equal hydrophilicity of both gel and liquid surfaces, the gel, unsurprisingly, accumulates at the core due to the stronger protein–protein interactions that sustain it and the lower surface tension of the liquid-like phase with the surrounding solvent (50).

Fig. 6.

Equal hydrophilicity for structured and disordered PLD FUS proteins causes the gel-like phase to relocate at the core of multiphase condensates. Final state comparison between a control simulation with the dynamical algorithm (A) where we set the same solvent–protein interactions regardless of protein type (for both ordered and disordered PLDs) and (B) the dynamical algorithm simulations from Fig. 5 where FUS with ordered PLDs presents lower surface tension due to the exposure of their RGG regions to the interface of the droplets. (A, Left and B, Left) Schematic illustrations of solvent–protein interactions. (A, Right) Snapshot of the quasi-kinetically arrested state of a direct coexistence simulation where fully disordered FUS and FUS with ordered PLDs exhibit equal hydrophilicity (i.e., they have the same affinity for water). (B, Right) Snapshot of the quasi-kinetically arrested state of a direct coexistence simulation where FUS with ordered PLDs has a preferential interaction with water and thus, a higher hydrophilicity.

Aging of condensates that start as single-component liquid-like systems and transition into multiphase architectures can be promoted not only by disorder to order structural transitions but also by other changes that strengthen the protein–protein interactions over time (e.g., in the microenvironment [e.g., pH, salt, pressure], in the patterns of posttranslational modifications, or in the condensate composition). Regardless, the interplay between the timescales of protein self-diffusion and the accumulation of disorder to order transitions (or the key factor strengthening biomolecular interactions) determines the properties of the aged condensate and can give rise to a wide range of steady-state morphologies and architectures, beyond those considered here.

Gradual maturation of solid-like condensates from liquid-like droplets due to disorder to order transitions or protein aggregation, as those reported in refs. 11 and 15–23, requires that the timescales of protein self-diffusion are the fastest. That is, when protein diffusion is slower than (or comparable with) the rates at which disorder to order transitions occur, we expect to observe the formation of kinetically arrested nuclei that grow into an aspherical solid-like structure. Aging of liquid condensates into the liquid-core/gel-shell or gel-core/liquid-shell architectures we report here also necessitates that the rate of accumulation of stronger protein–protein interactions is slower than the timescales of protein self-diffusion. Importantly, relative experimental β-sheet transition barriers suggest typical timescales of the order of hundreds of nanoseconds (75–77); protein self-diffusion timescales are of the order of hundreds of milliseconds (78); and fluctuation timescales of high-density protein concentration gradients, which lead to gradual rigidification of phase-separated condensates, are in the range of minutes (33).

Conclusions

In this study, we explore the formation of liquid-core/gel-shell and gel-core/liquid-shell multiphase architectures in single-component protein condensates. Combining atomistic simulations with coarse-grained simulations at two resolutions, we predict that an equilibrium homogeneous single-component protein condensate can age into a nonequilibrium multiphase condensate, where a liquid-like phase is in coexistence with an arrested gel-like phase, due to the advent over time of imbalanced homotypic protein–protein interactions. Strikingly, our simulations propose that such critical imbalanced interactions can emerge intrinsically within single-component protein condensates (i.e., even in the absence of chemical modifications or external stimuli) from a gradual accumulation of interprotein β-sheets. We further find that the specific ordering of the liquid-like and gel-like phases in the condensate is dictated by the molecular organization of proteins within each of the two different coexisting phases because that modulates the properties and interfacial free energies of the various interfaces involved (i.e., condensate–solvent and gel–liquid).

During the aging of single-component FUS condensates, we find that accumulation of disorder to order structural transitions among the PLDs, which give rise to interprotein β-sheet ladders, can sufficiently enhance the strength of PLD–PLD interactions and drive the transformation of the condensate into a nonequilibrium liquid-core/gel-shell multiphase architecture. Furthermore, we observe that despite the inner liquid-like core and outer arrested gel-like shell being composed of chemically identical FUS proteins (i.e., only distinguished by the structure of their PLDs and hence, the strength of PLD–PLD interactions), each phase exhibits strikingly different molecular organization. That is, the liquid-like low-density phase at the core of the FUS multiphase condensates is structurally homogeneous as it is sustained by weak and transient interactions among FUS proteins that can diffuse freely across the whole phase. By contrast, the molecular organization of the arrested gel-like high-density FUS shell is heterogeneous—i.e., PLD regions form a hydrophobic core due to strengthened PLD–PLD interactions mediated by kinked cross–β-sheets, and the charge-rich RGG2 and RGG3 domains preferentially expose their positively charged side chains to the solvent. Consistently with the liquid-core/gel-shell architecture, we observe that the FUS gel phase has a more hydrophilic interface due to its higher surface charge density than the lower-density liquid phase. In contrast, in protein systems where the gel phase has equal or lower hydrophilicity than the liquid, we predict that the condensates will form instead a nonequilibrium gel-core/liquid-shell architecture, as that organization increases the enthalpic gain for condensate formation and lowers the interfacial free energy density of the overall system.

Importantly, our findings suggest that the accumulation of disorder to order protein structural transitions, hence molecular-scale processes, can modulate mesoscale phase behavior of protein condensates and lead to the emergence of nonequilibrium multiphase architectures in single-component protein systems during aging. This finding is significant as it demonstrates that multiphasic organization can arise not only from multicomponent systems that contain two or more different molecular entities (e.g., two different biomolecules) but also, from a single-component system that is driven out of equilibrium by the intrinsic onset of imbalanced intermolecular forces. While in our example, imbalanced intermolecular interactions are introduced by distinct FUS structural ensembles (FUS–PLD in a fully disordered vs. an ordered state), there are several other scenarios from which heterogeneity can arise [e.g., amino acid sequence mutations, application of mechanical forces (16), and posttranslational modifications (53)]. The ability of imbalanced intermolecular forces to drive single-component mixtures toward complex nonequilibrium architectures has been recently demonstrated for a solution of chiral tetramer model molecules that can transition between two enantiomeric states and form steady-state arrested microphase domains (79)—akin to the nonequilibrium aged multiphase condensates we report here for naturally occurring proteins.

The prediction that nonequilibrium multiphase condensates can emerge from single-component protein systems is interesting from a fundamental point of view, as it highlights how structural disorder to order transitions can give rise to significant physicochemical diversity within a condensate without changing the chemical makeup of its biomolecular components. We speculate that such transformations in single-component systems may have widespread physiological and pathological implications: for example, in the establishment of core–shell structures (e.g., in stress granules) (38), in the formation of multilayered compartments of the FUS family protein TDP-43 with vacuolated nucleoplasm-filled internal space (42), or in other hierarchically organized subcellular condensate structures where molecules may undergo a structural change or experience some other chemical or physical alteration (46).

More broadly, the multiscale modeling strategies developed in this study can be extended to probe the underlying thermodynamic mechanisms and kinetics of other complex equilibrium and nonequilibrium condensate architectures and shed light on how molecular-level features influence the biophysical properties of compartments in cellular function and dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

In this work, we develop a multiscale approach to connect fine atomistic features of proteins to the process of condensate aging. Our method combines descriptions of proteins at three levels of resolution: 1) atomistic PMF simulations of interacting peptides using two different force fields [a99SB-disp (66) and CHARMM36m (67)], 2) sequence-dependent coarse-grained simulations of phase-separated protein condensates (63), and 3) a tailor-made minimal model of dynamically aging condensates where the intermolecular forces among proteins are nonconservative. Our MD simulations of condensates are done with the direct coexistence method, which simulates the condensed and diluted phases in the same simulation box separated by an interface. Full details on the atomistic PMF simulations, the residue-resolution coarse-grained model and direct coexistence simulations, estimation of the number of molecular contacts, the minimal coarse-grained model, and the dynamical algorithm and local order parameter as well as the simulation details for all resolution models are provided in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results received funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Framework Programme through Future and Emerging Technologies Grant NanoPhlow 766972 (to G.K. and T.P.J.K.), Marie Skłodowska-Curie Grant MicroSPARK 841466 (to G.K.), the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007-2013 through ERC Grant PhysProt 337969 (to T.P.J.K.), and ERC Grant InsideChromatin 803326 (to R.C.-G.). A.G. acknowledges funding from Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) Grant EP/N509620/and the Winton Programme. We further thank the Oppenheimer Research Fellowship (J.R.E.), the Emmanuel College Roger Ekins Fellowship (J.R.E), the King’s College Research Fellowship (J.A.J.), the Herchel Smith Funds (G.K.), the Wolfson College Junior Research Fellowship (G.K.), the Newman Foundation (T.P.J.K.), the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (T.P.J.K.), and the Winton Advanced Research Fellowship (R.C.-G.).

We also acknowledge funding from Wellcome Trust Collaborative Award 203249/Z/16/Z (to T.P.J.K.). The simulations were performed using resources provided by the Cambridge Tier-2 system operated by the University of Cambridge Research Computing Service (https://www.hpc.cam.ac.uk/) funded by EPSRC Tier-2 Capital Grant EP/P020259/1.

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: G.K. is an employee and T.P.J.K. is a member of the board of directors at Transition Bio.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. R.B. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2119800119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All relevant data are provided in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Hyman A. A., Weber C. A., Jülicher F., Liquid-liquid phase separation in biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 30, 39–58 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shin Y., Brangwynne C. P., Liquid phase condensation in cell physiology and disease. Science 357, eaaf4382 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banani S. F., Lee H. O., Hyman A. A., Rosen M. K., Biomolecular condensates: Organizers of cellular biochemistry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 285–298 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boeynaems S., et al., Protein phase separation: A new phase in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 28, 420–435 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brangwynne C. P., Tompa P., Pappu R., Polymer physics of intracellular phase transitions. Nat. Phys. 11, 899–904 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gomes E., Shorter J., The molecular language of membraneless organelles. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 7115–7127 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin E. W., et al., Valence and patterning of aromatic residues determine the phase behavior of prion-like domains. Science 367, 694–699 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li P., et al., Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature 483, 336–340 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Larson A. G., et al., Liquid droplet formation by HP1α suggests a role for phase separation in heterochromatin. Nature 547, 236–240 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang J., et al., A molecular grammar governing the driving forces for phase separation of prion-like RNA binding proteins. Cell 174, 688–699 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molliex A., et al., Phase separation by low complexity domains promotes stress granule assembly and drives pathological fibrillization. Cell 163, 123–133 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franzmann T. M., Alberti S., Prion-like low-complexity sequences: Key regulators of protein solubility and phase behavior. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 7128–7136 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gotor N. L., et al., RNA-binding and prion domains: The Yin and Yang of phase separation. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 9491–9504 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.March Z. M., King O. D., Shorter J., Prion-like domains as epigenetic regulators, scaffolds for subcellular organization, and drivers of neurodegenerative disease. Brain Res. 1647, 9–18 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patel A., et al., A liquid-to-solid phase transition of the als protein fus accelerated by disease mutation. Cell 162, 1066–1077 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen Y., et al., Biomolecular condensates undergo a generic shear-mediated liquid-to-solid transition. Nat. Nanotechnol. 15, 841–847 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakami T., et al., Als/ftd mutation-induced phase transition of FUS liquid droplets and reversible hydrogels into irreversible hydrogels impairs RNP granule function. Neuron 88, 678–690 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murray D. T., et al., Structure of FUS protein fibrils and its relevance to self-assembly and phase separation of low-complexity domains. Cell 171, 615–627 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes M. P., et al., Atomic structures of low-complexity protein segments reveal kinked β sheets that assemble networks. Science 359, 698–701 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo F., et al., Atomic structures of FUS LC domain segments reveal bases for reversible amyloid fibril formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 341–346 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guenther E. L., et al., Atomic-level evidence for packing and positional amyloid polymorphism by segment from TDP-43 RRM2. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 311–319 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gui X., et al., Structural basis for reversible amyloids of hnRNPA1 elucidates their role in stress granule assembly. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–12 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kato M., et al., Cell-free formation of RNA granules: Low complexity sequence domains form dynamic fibers within hydrogels. Cell 149, 753–767 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.St George-Hyslop P., et al., The physiological and pathological biophysics of phase separation and gelation of RNA binding proteins in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and fronto-temporal lobar degeneration. Brain Res. 1693 (Pt A), 11–23 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberti S., Dormann D., Liquid–liquid phase separation in disease. Annu. Rev. Genet. 53, 171–194 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alberti S., Hyman A. A., Biomolecular condensates at the nexus of cellular stress, protein aggregation disease and ageing. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 196–213 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harmon T. S., Holehouse A. S., Rosen M. K., Pappu R. V., Intrinsically disordered linkers determine the interplay between phase separation and gelation in multivalent proteins. eLife 6, e30294 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Espinosa J. R., et al., Liquid network connectivity regulates the stability and composition of biomolecular condensates with many components. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 13238–13247 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jadrich R., Schweizer K. S., Percolation, phase separation, and gelation in fluids and mixtures of spheres and rods. J. Chem. Phys. 135, 234902 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qamar S., et al., Fus phase separation is modulated by a molecular chaperone and methylation of arginine cation-πinteractions. Cell 173, 720–734.e15 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bock A. S., et al., N-terminal acetylation modestly enhances phase separation and reduces aggregation of the low-complexity domain of RNA-binding protein fused in sarcoma. Protein Sci. 30, 1337–1349 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Monahan Z., et al., Phosphorylation of the FUS low-complexity domain disrupts phase separation, aggregation, and toxicity. EMBO J. 36, 2951–2967 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jawerth L., et al., Protein condensates as aging Maxwell fluids. Science 370, 1317–1323 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fare C. M., Shorter J., (Dis)solving the problem of aberrant protein states. Dis. Model. Mech. 14, dmm048983 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feric M., et al., Coexisting liquid phases underlie nucleolar subcompartments. Cell 165, 1686–1697 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brangwynne C. P., Mitchison T. J., Hyman A. A., Active liquid-like behavior of nucleoli determines their size and shape in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 4334–4339 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West J. A., et al., Structural, super-resolution microscopy analysis of paraspeckle nuclear body organization. J. Cell Biol. 214, 817–830 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jain S., et al., Atpase-modulated stress granules contain a diverse proteome and substructure. Cell 164, 487–498 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guillén-Boixet J., et al., RNA-induced conformational switching and clustering of g3bp drive stress granule assembly by condensation. Cell 181, 346–361.e17 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu H., et al., HSP70 chaperones RNA-free TDP-43 into anisotropic intranuclear liquid spherical shells. Science 371, eabb4309 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kistler K. E., et al., Phase transitioned nuclear Oskar promotes cell division of Drosophila primordial germ cells. eLife 7, e37949 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt H. B., Rohatgi R., In vivo formation of vacuolated multi-phase compartments lacking membranes. Cell Rep. 16, 1228–1236 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alshareedah I., Moosa M. M., Raju M., Potoyan D. A., Banerjee P. R., Phase transition of RNA-protein complexes into ordered hollow condensates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 15650–15658 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gallego L. D., et al., Phase separation directs ubiquitination of gene-body nucleosomes. Nature 579, 592–597 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mountain G. A., Keating C. D., Formation of multiphase complex coacervates and partitioning of biomolecules within them. Biomacromolecules 21, 630–640 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu T., Spruijt E., Multiphase complex coacervate droplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 2905–2914 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boeynaems S., et al., Spontaneous driving forces give rise to protein-RNA condensates with coexisting phases and complex material properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116, 7889–7898 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaur T., et al., Sequence-encoded and composition-dependent protein-RNA interactions control multiphasic condensate morphologies. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–16 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fisher R. S., Elbaum-Garfinkle S., Tunable multiphase dynamics of arginine and lysine liquid condensates. Nat. Commun. 11, 4628 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sanchez-Burgos I., Joseph J. A., Collepardo-Guevara R., Espinosa J. R., Size conservation emerges spontaneously in biomolecular condensates formed by scaffolds and surfactant clients. Sci. Rep. 11, 15241 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dar F., Pappu R. V., Multidimensional phase diagrams for multicomponent systems comprising multivalent proteins. Biophys. J. 118, 213a (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jacobs W. M., Frenkel D., Phase transitions in biological systems with many components. Biophys. J. 112, 683–691 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ranganathan S., Shakhnovich E., Emergence of order in condensates composed of multi-valent, multi-domain proteins. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2021). 10.1101/2021.11.15.468745 (Accessed 15 February 2022). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Garaizar A., Espinosa J. R., Joseph J. A., Collepardo-Guevara R., Kinetic interplay between droplet maturation and coalescence modulates shape of aged protein condensates. Sci. Rep. 12, 4390 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ranganathan S., Shakhnovich E. I., Dynamic metastable long-living droplets formed by sticker-spacer proteins. eLife 9, e56159 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dignon G. L., Zheng W., Mittal J., Simulation methods for liquid-liquid phase separation of disordered proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 23, 92–98 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Paloni M., Bailly R., Ciandrini L., Barducci A., Unraveling molecular interactions in liquid-liquid phase-separation of disordered proteins by atomistic simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 9009–9016 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benayad Z., von Bülow S., Stelzl L. S., Hummer G., Simulation of fus protein condensates with an adapted coarse-grained model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 17, 525–537 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zheng W., et al., Molecular details of protein condensates probed by microsecond long atomistic simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 11671–11679 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Krainer G., et al., Reentrant liquid condensate phase of proteins is stabilized by hydrophobic and non-ionic interactions. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–10 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dignon G. L., Zheng W., Kim Y. C., Best R. B., Mittal J., Sequence determinants of protein phase behavior from a coarse-grained model. PLOS Comput. Biol. 14, e1005941 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Garaizar A., Espinosa J. R., Salt dependent phase behavior of intrinsically disordered proteins from a coarse-grained model with explicit water and ions. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 125103 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Joseph A. J., et al., Physics-driven coarse-grained model for biomolecular phase separation with near-quantitative accuracy. Nat. Comput. Sci. 1, 732–743 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Šarić A., Chebaro Y. C., Knowles T. P. J., Frenkel D., Crucial role of nonspecific interactions in amyloid nucleation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 111, 17869–17874 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Samantray S., Yin F., Kav B., Strodel B., Different force fields give rise to different amyloid aggregation pathways in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 60, 6462–6475 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Robustelli P., Piana S., Shaw D. E., Developing a molecular dynamics force field for both folded and disordered protein states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E4758–E4766 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang J., et al., CHARMM36m: An improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods 14, 71–73 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kapcha L. H., Rossky P. J., A simple atomic-level hydrophobicity scale reveals protein interfacial structure. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 484–498 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Michaels T. C. T., et al., Chemical kinetics for bridging molecular mechanisms and macroscopic measurements of amyloid fibril formation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 69, 273–298 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ladd A., Woodcock L., Triple-point coexistence properties of the Lennard-Jones system. Chem. Phys. Lett. 51, 155–159 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 71.García Fernández R., Abascal J. L., Vega C., The melting point of ice Ih for common water models calculated from direct coexistence of the solid-liquid interface. J. Chem. Phys. 124, 144506 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Espinosa J. R., Sanz E., Valeriani C., Vega C., On fluid-solid direct coexistence simulations: The pseudo-hard sphere model. J. Chem. Phys. 139, 144502 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Welsh T. J., et al., Surface electrostatics govern the emulsion stability of biomolecular condensates. Nano Lett. 22, 612–621 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Guenther E. L., et al., Atomic structures of TDP-43 LCD segments and insights into reversible or pathogenic aggregation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 25, 463–471 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kathuria S. V., et al., Minireview: Structural insights into early folding events using continuous-flow time-resolved small-angle X-ray scattering. Biopolymers 95, 550–558 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Huang J. J. T., Larsen R. W., Chan S. I., The interplay of turn formation and hydrophobic interactions on the early kinetic events in protein folding. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 48, 487–497 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kubelka J., Hofrichter J., Eaton W. A., The protein folding ‘speed limit’. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 14, 76–88 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Strom A. R., et al., Phase separation drives heterochromatin domain formation. Nature 547, 241–245 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Uralcan B., Longo T. J., Anisimov M. A., Stillinger F. H., Debenedetti P. G., Interconversion-controlled liquid-liquid phase separation in a molecular chiral model. J. Chem. Phys. 155, 204502 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are provided in the article and/or SI Appendix.