Abstract

Despite global improvement in annual measles incidence and mortality since 2000, progress toward elimination goals has slowed. The World Health Organization (WHO) European Region (EUR) established a regional goal for measles and rubella elimination by 2015. Romania is one of 13 EUR countries in which measles remains endemic. To identify barriers to meeting programmatic targets and to aid in prioritizing efforts to strengthen measles elimination strategy implementation, the WHO and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed a measles programmatic risk assessment tool that uses routinely collected data to estimate district-level risk scores. The WHO measles programmatic risk assessment tool was used to identify high-risk areas in order to guide measles elimination program activities in Romania. Of the 42 districts in Romania, 27 (64%) were categorized as very high or high risk. Many of the very-high-risk districts were clustered in the western part of the country or were clustered around the capital Bucharest in the southeastern part of the country. The overall risk scores in the very-high-risk districts were driven primarily by poor surveillance quality and suboptimal population immunity. The measles risk assessment conducted in Romania was the first assessment to be completed in a European country. Annual assessments using the programmatic risk tool could provide valuable information for immunization program and surveillance staff at the national level and in each district to guide activities to enhance measles elimination efforts, such as strengthening routine immunization services, improving immunization campaign planning, and intensifying surveillance.

Keywords: Elimination, measles, outbreak, risk assessment, Romania

1. INTRODUCTION

In 2012, the Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) was published and endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) and global partners. This key global document serves as the guide for global immunization efforts and sets a goal for measles elimination by 2020 in five of the six WHO regions.(1) All six WHO regions have set goals for measles elimination by or before 2020.(2) Despite significant improvement in annual incidence and mortality attributed to measles since 2000, progress toward elimination goals has slowed since 2010. Based on current trends in progress and performance, GVAP targets are not likely to be achieved on time and additional focused efforts will be needed to achieve regional elimination goals.(2) To identify barriers to meeting programmatic targets and to aid in prioritizing efforts to strengthen measles elimination strategy implementation, the WHO and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) developed a measles programmatic risk assessment tool. Development of the tool was aided by a group of experts convened by the WHO that included measles elimination program staff from each of the six WHO regional offices. This group met in Geneva in May 2014 to review and inform the tool development. The tool is intended to be used by national program managers to identify districts that are at risk for measles virus transmission, and to provide data to make recommendations to improve programmatic weaknesses.

In September 2010, the 53 member states of the WHO European region (EUR) established a regional goal for measles and rubella elimination by 2015.(3–5) The 2005–2010 EUR Strategic Plan included four strategies related to measles control and elimination: (1) achieve and maintain ≥95% coverage with two doses of measles-containing vaccine (MCV) through high-quality routine immunization services, (2) provide a second opportunity for measles immunization through supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) to populations susceptible to measles, (3) strengthen measles case-based surveillance systems with rigorous case investigation and laboratory testing of suspected cases, and (4) improve availability of high-quality information on the benefits and risks associated with immunization against measles.(6) The following performance indicators were proposed in the 2005–2010 EUR Strategic Plan to measure progress toward regional measles elimination: (1) the number of countries with a measles incidence of <1 per million population, and (2) the number of countries with first dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV1) coverage of ≥95% at national level and ≥90% in all districts.(4,6)

Worldwide during 2000–2014, annual reported measles cases decreased by 73%, and estimated measles mortality declined by 79%.(2) The EUR region experienced similar declines in both measles incidence and mortality over the same time period. In 2014, overall measles incidence in Europe was 19 per million, and measles-related mortality had decreased by 67% since 2000.(2) However, in recent years the EUR region has experienced multiple outbreaks and continued endemic transmission of measles.(3) In 2013 the EUR regional verification committee concluded that 22 (42%) member states have eliminated measles, 14 (26%) have inconclusive status, and 13 (25%) countries remain endemic (including Romania).(7)

Romania is a southeastern European country with an estimated population of 20 million.(8) The country borders the Black Sea to the southeast, and the countries Ukraine, Moldova, Hungary, Serbia, and Bulgaria. The country has a total geographic area of 238,391 km2 with a population density of 90.8 persons per km2,(9) and is administratively divided into 42 districts. The childhood immunization schedule in Romania includes MCV1 given at age 12 months, and a second dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV2) given at age six to seven years (MCV2 was introduced in 1995 and was combined with mumps and rubella antigens as an MMR vaccine in 2005).(10)

Coverage with MCV1 in Romania increased from 83% in 1983 to 97% in 1997, and remained high through 2010 (between 95% and 98% annually) (Fig. 1). Since 2010, MCV1 coverage decreased and was estimated at 89% in 2014.(11) A national coverage survey of children at age 18 months conducted in February 2015 found MCV1 coverage of 87.6%.(12) Annual MCV2 coverage was ≥95% until 2009, when it began to decrease; in 2014, it was estimated at 88%. SIAs were implemented at the subnational level in 2010 and 2011.(13) Both SIAs targeted children aged seven months to seven years. The 2010 campaign reached 2,919 children, and the 2011 campaign—a school-based campaign in areas affected by a measles outbreak—reached 4,500 children.

Fig. 1.

Reported measles cases and estimated coverage with MCV1 and MCV2—Romania, 1980–2014.

Source: WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: monitoring system 2015 global summary. WHO/UNICEF coverage estimates & official country estimates, Sep 2015. WHO/UNICEF coverage estimates are shown. Neither WHO-UNICEF nor country estimates available where line not shown NA = Data not available.

To focus elimination efforts in Romania, the WHO measles programmatic risk assessment tool was used to identify areas not meeting programmatic targets in order to guide and strengthen measles elimination program activities and reduce the risk of future outbreaks.

2. METHODS

The development and methods of the WHO measles programmatic risk assessment tool were described in detail and published previously.(14) The tool assesses overall programmatic risk at the district level based on indicator scores in four categories: (1) population immunity, (2) surveillance quality, (3) program performance, and (4) threat assessment (Table I).

Table I.

Maximum Risk Points by Component of the World Health Organization (WHO) Measles Programmatic Assessment Tool for Risk of Measles Virus Transmission

| Components | Points | Cut-Off Criteria (Risk Points) |

|---|---|---|

| Population immunity | (40) | |

| District MCV1 coveragea | 8 | ≥95% (+0); 90–94% (+2); 85–89% (+4); 80–84% (+6); <80% (+8) |

| Proportion of neighboring districts with <80% MCV1 | 4 | <50% (+0); 50–74% (+2); ≥75% (+4) |

| District MCV2 coveragea | 8 | Same as MCV1 coverage |

| Measles SIA conducted within the past three yearsb | 8 | Yes: ≥95% coverage (+0); 90–94% coverage (+2); 85–89% coverage (+4); <85% coverage (+6); no coverage data (+6); no SIA (+8) |

| Target age group of measles SIA conducted within the past three years | 2 | Wide age group (+0); narrow age group (+2); no SIA (+2) |

| Years since the last measles SIA | 4 | ≤1 year (+0); 2 years (+2); ≥3 years (+4) |

| Proportion of suspected cases who are unvaccinated or have unknown vaccination status | 6 | <20% (+0); >20% (+6) |

| Surveillance quality | (20) | |

| Nonmeasles discarded rate | 8 | ≥2 per 100,000 (+0); <2 per 100,000 (+4); <1 per 100,000 (+8) |

| Proportion of measles cases with adequate investigation | 4 | ≥80% (+0); <80% (+4) |

| Proportion of measles cases with adequate specimens collection | 4 | ≥80% (+0); <80% (+4) |

| Proportion of measles cases with laboratory results available in a timely manner | 4 | ≥80% (+0); <80% (+4) |

| Program performance | (16) | |

| Trends in MCV1 coverage | 4 | Increasing or same (+0); ≤10% decline (+2); >10% decline (+4) |

| Trends in MCV2 coverage | 4 | Same as MCV1 trend |

| MCV1-MCV2 dropout rate | 4 | ≤10% (+0); >10% (+4) |

| DPT1-MCV1 dropout rate | 4 | Same as MCV1-MCV2 dropout rate |

| Threat assessment | (24) | |

| ≥1 measles case reported among children <5 years | 4 | No (+0); yes (+4) |

| ≥1 measles case reported among persons 5–14 years | 3 | No (+0); yes (+3) |

| ≥1 measles case reported among persons ≥15 years | 3 | No (+0); yes (+3) |

| Population density | 4 | 0–50/km2 (+0); 51–100/km2 (+1); 101–300/km2 (+2); 301–1000/km2 (+3); >1000/km2 (+4) |

| ≥1 measles case reported in a bordering district within the past 12 months | 2 | No (+0); yes (+2) |

| Presence of vulnerable groupsc | 8 | No vulnerable groups (+0); one risk point for each vulnerable group present (up to maximum of +8) |

| Total possible points | (100) |

DPT1 = first dose in series for diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus vaccination; MCV1 = first dose in series for measles-containing vaccination;

MCV2 = second dose in series for measles-containing vaccination; SIA = supplementary immunization activity.

Vaccination coverage estimates from surveys if conducted within past three years and includes birth cohorts of recent three years that can be used to replace administrative coverage.

Outbreak response immunization (ORI) campaign coverage data can be considered if an SIA was not conducted within the past three years and if the ORI targeted a geographical area that included the entire district.

Presence of vulnerable groups includes any of the following: (1) migrant population, internally displaced population, slums, or tribal communities; (2) communities resistant to vaccination (e.g., religious, cultural, philosophical reasons); (3) security and safety concerns; (4) areas frequented by calamities/disasters; (5) poor access to health services due to terrain/transportation issues; (6) lack of local political support; (7) high-traffic transportation hubs/major roads or bordering large urban areas (within and across countries); (8) areas with mass gatherings (i.e., trade/commerce, fairs, markets, sporting events, high density of tourists).

The population immunity category assessed susceptibility to measles among the population in each district and had a maximum of 40 risk points. Administrative vaccination coverage data from the district level were used for measures of MCV1 and MCV2 coverage and to calculate the proportion of a district’s bordering districts that have MCV1 coverage <80%. District-level data on vaccination coverage and target age group for the most recent measles SIA campaign, if conducted within the past three years, were used. The proportion of suspected measles cases from the past three years who were unvaccinated or had unknown vaccination status was calculated using case-based surveillance data.

Measles case-based surveillance data included suspected measles cases that were investigated using a case investigation form and laboratory testing of a blood specimen.(15) A suspected measles case was defined as an illness with maculopapular rash and fever and one or more symptoms of cough, coryza, or conjunctivitis, or where a clinician suspected measles. A laboratory-confirmed case was defined as a suspected measles case with a positive laboratory test result for measles-specific immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibodies. The surveillance quality indicators evaluated the capacity to detect and confirm suspected cases rapidly and accurately in a district. The four surveillance quality indicators were calculated using measles case-based surveillance data from the previous calendar year and had a total of 20 possible risk points. They included the nonmeasles nonrubella discarded rate; the proportion of suspected measles cases with adequate investigation; the proportion of cases with adequate specimen collection; and the proportion of cases for whom laboratory results were available in a timely manner. An adequate investigation was defined as a suspected case in case-based surveillance data that was investigated within 48 hours of notification and included all 10 core variables: case identification, date of birth/age, sex, place of residence, vaccination status or date of last vaccination, date of rash onset, date of notification, date of investigation, date of blood sample collection, and place of infection or travel history. Adequate specimen collection was defined as a suspected case with a blood specimen collected within 28 days of rash onset. Timely laboratory results were defined as those available within 10 days of specimen collection.

The program performance indicators assessed aspects of routine immunization (RI) services and had a total of 16 possible risk points. Three-year trends in MCV1 and MCV2 coverage, dropout rates from MCV1 to MCV2, and dropout rates from first dose of diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus vaccine (DPT1) to MCV1 were calculated using administrative vaccination coverage data at the district level.

The threat assessment indicators had a total of 24 possible risk points and included factors that might influence the risk for measles virus exposure and transmission in the population. The indicators included reported measles cases in the past year among persons aged <5 years, 5–14 years, and ≥15 years, measles cases reported in a bordering district within the past 12 months, and district population density. These indicators used measles case-based surveillance data, population census data, and geographic area of each district. Presence of vulnerable groups was the last threat assessment indicator. Vulnerable groups included the following: (1) migrants, internally displaced persons, slum populations, or tribal communities; (2) groups with resistance to vaccination (i.e., religious or cultural issues); (3) those living in areas where there were security and safety concerns; (4) those living in areas with frequent calamities or natural disasters; (5) groups with poor access to health services due to terrain or transportation issues; (6) communities where there was lack of local political support for immunizations; (7) groups residing near high-traffic transportation hubs, major roads, or large urban areas; and (8) groups living near areas with mass gatherings (i.e., trade/commerce, fairs, markets, sporting events, high density of tourists). These data came from local knowledge of vulnerable groups from the national Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) manager or equivalent.

Scores from each of the four indicator categories were totaled to assign an overall risk score for each district. Each district could be assessed a maximum overall score of 100 risk points. Districts were categorized as low, medium, high, or very high risk based on the overall score. Risk category cutoffs were based on a distribution of all possible combinations of scores from each indicator, and were the 50th, 75th, and 90th percentiles of the possible score distribution. Districts with an overall score of ≤47 were categorized as low risk, those with scores of 48–54 were medium risk, those with scores of 55–60 were high risk, and districts with scores of ≥61 were very high risk. We used Romania Ministry of Health (MOH) data that were routinely collected by the immunization and surveillance programs from three years (2012–2014) and MOH shape files for maps to assign overall risk scores by district. Data were managed using Excel (Microsoft Corporation) and mapped using ArcGIS version 10.1 (ESRI).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Measles Epidemiology

The median annual number of measles cases reported in Romania during the 1990s was 5,376 cases (Fig. 1).(11) Recent outbreaks occurred in 2005–2006 and 2010–2012. The 2010–2012 outbreak affected the entire country and included >10,000 cases, mainly among children <1 year and children age 1–9 years who were unvaccinated.(7,10) The elevated number of reported cases continued into 2013.

3.2. Risk Scores

Overall scores for the 42 districts in Romania in 2015 ranged from 44 to 76 points out of a possible 100 points (Table II). Of the 42 districts, 14 (33%) were categorized as very high risk, 13 (31%) were categorized as high risk, 11 (26%) were categorized as medium risk, and four (10%) were categorized as low risk (Figs. 2 and 3). Many of the very high-risk districts were clustered in the western part of the country near the borders with Hungary and Serbia; the two districts with the highest risk scores were Arad (76) and Hunedoara (76). Another cluster of very-high-risk districts was in the southeastern part of the country near Bucharest, the capital. The district of Bucharest was categorized as very high risk (63 risk points), and three other districts in the southeast were very high risk, with 63–68 risk points. All but one of the districts in northern Romania that border Ukraine were medium risk. The four districts that were low risk were in the south and east of the country—Dolj, Teleorman, Tulcea, and Vrancea.

Table II.

Risk Points by District, Romania, 2015

| Risk Category Scores | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | Population Immunity | Surveillance Quality | Program Delivery | Threat Assessment | Total Risk Points | Risk Category |

| Arad | 38 | 20 | 12 | 6 | 76 | VHR |

| Hunedoara | 36 | 20 | 14 | 6 | 76 | VHR |

| Neamt | 36 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 71 | VHR |

| Ialomita | 28 | 20 | 4 | 16 | 68 | VHR |

| Timis | 36 | 20 | 8 | 4 | 68 | VHR |

| Alba | 32 | 12 | 8 | 12 | 64 | VHR |

| Bacau | 30 | 20 | 8 | 6 | 64 | VHR |

| Prahova | 28 | 20 | 10 | 6 | 64 | VHR |

| Satu Mare | 30 | 20 | 8 | 6 | 64 | VHR |

| Bucuresti | 30 | 12 | 8 | 13 | 63 | VHR |

| Caras | 34 | 20 | 8 | 1 | 63 | VHR |

| Constanta | 28 | 20 | 8 | 7 | 63 | VHR |

| Galati | 26 | 20 | 8 | 7 | 61 | VHR |

| Vaslui | 30 | 20 | 8 | 3 | 61 | VHR |

| Cluj | 28 | 20 | 4 | 8 | 60 | HR |

| Brasov | 28 | 20 | 4 | 7 | 59 | HR |

| Ilfov | 24 | 20 | 8 | 7 | 59 | HR |

| Vilcea | 22 | 20 | 4 | 13 | 59 | HR |

| Calarasi | 30 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 58 | HR |

| Salaj | 28 | 20 | 4 | 6 | 58 | HR |

| Sibiu | 26 | 12 | 8 | 11 | 57 | HR |

| Arges | 26 | 20 | 4 | 6 | 56 | HR |

| Covasna | 22 | 20 | 8 | 6 | 56 | HR |

| Gorj | 26 | 20 | 4 | 6 | 56 | HR |

| Suceava | 26 | 20 | 4 | 6 | 56 | HR |

| Dimbovita | 26 | 12 | 6 | 11 | 55 | HR |

| Mehedinti | 26 | 20 | 4 | 5 | 55 | HR |

| Botosani | 26 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 54 | MR |

| Olt | 22 | 12 | 4 | 16 | 54 | MR |

| Buzau | 24 | 12 | 4 | 13 | 53 | MR |

| Harghita | 22 | 20 | 4 | 6 | 52 | MR |

| Iasi | 24 | 20 | 2 | 6 | 52 | MR |

| Maramures | 24 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 52 | MR |

| Braila | 24 | 20 | 2 | 5 | 51 | MR |

| Bistrita | 20 | 20 | 4 | 6 | 50 | MR |

| Giurgiu | 28 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 49 | MR |

| Bihor | 22 | 12 | 4 | 10 | 48 | MR |

| Mures | 26 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 48 | MR |

| Vrancea | 24 | 8 | 4 | 11 | 47 | LR |

| Teleorman | 24 | 8 | 4 | 10 | 46 | LR |

| Dolj | 22 | 12 | 2 | 9 | 45 | LR |

| Tulcea | 16 | 20 | 4 | 4 | 44 | LR |

VHR = very high risk; HR = high risk; MR = medium risk; LR = low risk.

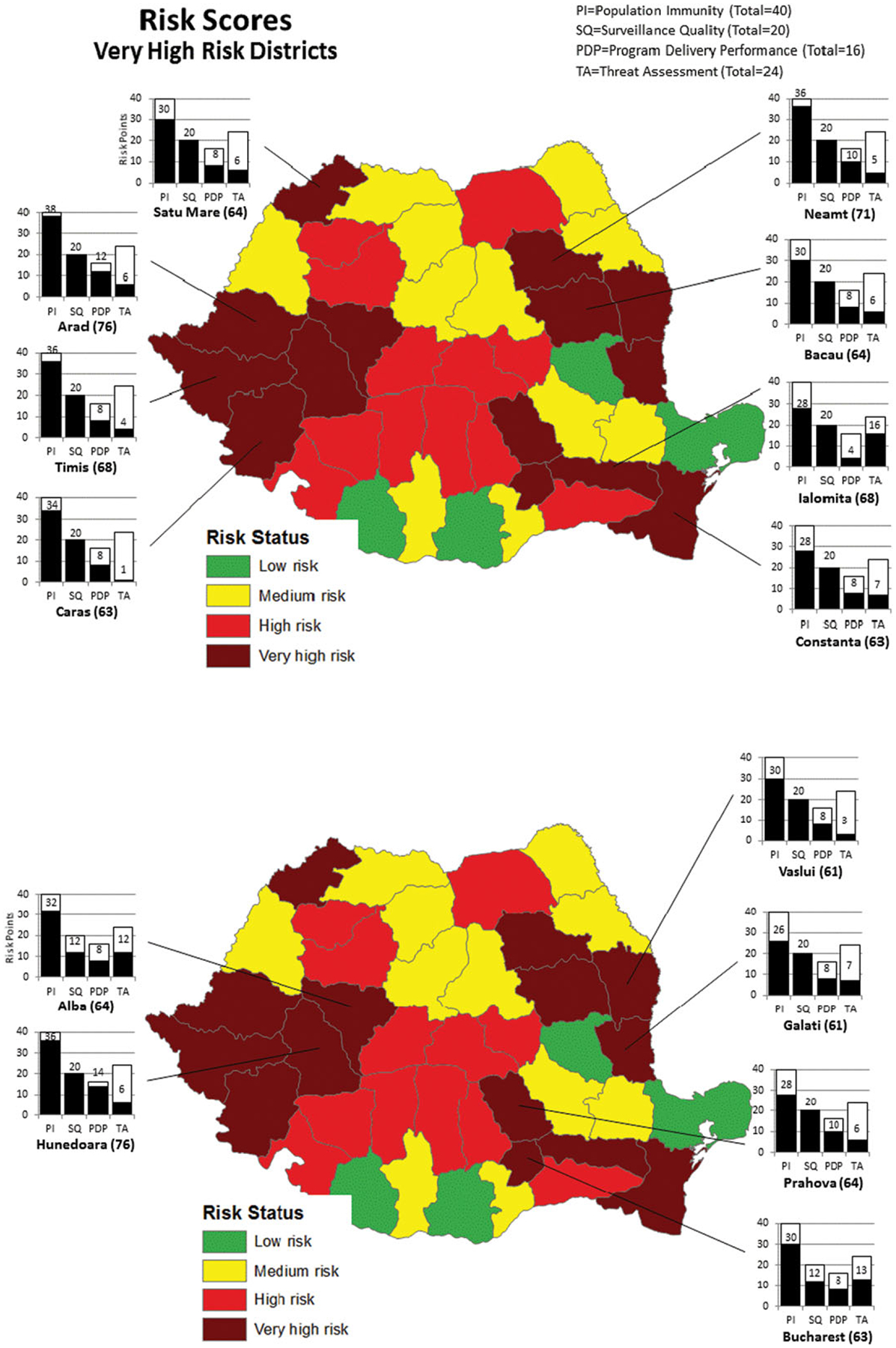

Fig. 2.

Overall risk score breakdowns of very-high-risk districts by risk category—Romania, 2012–2014.

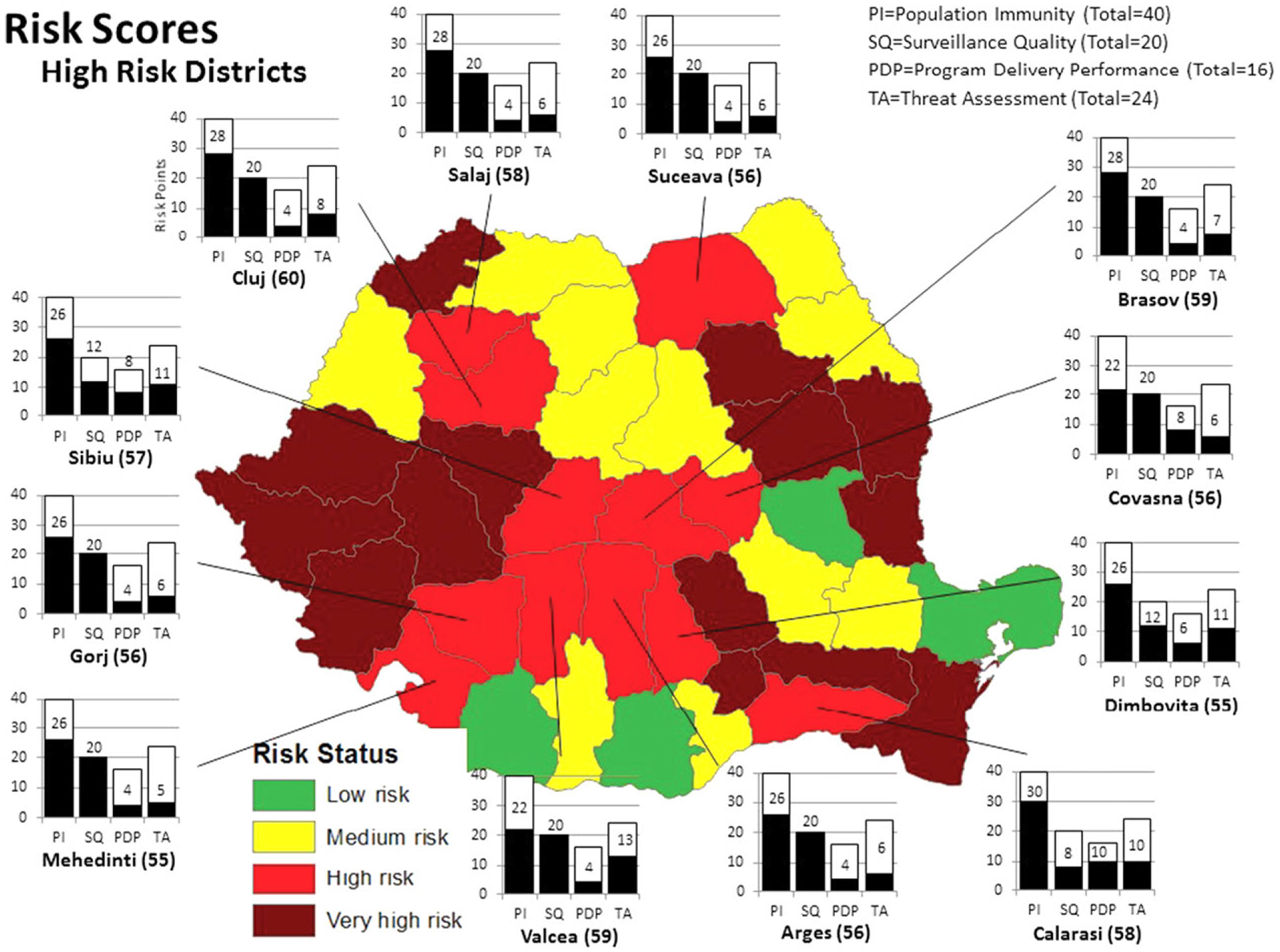

Fig. 3.

Overall risk score breakdowns of high-risk districts by risk category—Romania, 2012–2014.

The overall risk scores in the very-high-risk districts were driven primarily by poor surveillance quality, and to a lesser degree by suboptimal population immunity. Out of the 14 very-high-risk districts, 12 had 20 out of 20 points for surveillance quality (Table II, Figs. 2 and 3). Ten had 30 points or more out of 40 possible points for population immunity. Among the very-high-risk districts, only three had 12 or more points out of a possible 24 for threat assessment.

3.3. Population Immunity

Average MCV1 coverage during 2012–2014 ranged from 72% in Hunedoara to 96% in Bistrita and Giurgiu (Table III). Four of the 42 districts received the maximum eight risk points for three-year average MCV1 coverage that was below 80%. Average MCV2 coverage ranged from 63% (Arad) to 96% (Bistrita, Harghita, Olt, and Tulcea). Eight districts received the maximum eight risk points for three-year average MCV2 coverage that was below 80%. There were no measles SIAs conducted in Romania in the three years prior to the risk assessment, so all districts received the maximum points for SIA indicators.

Table III.

Vaccination Coverage and Dropout Rates by District, Romania, 2012–2014

| MCV1 Coverage (%) | MCV2 Coverage (%) | MCV1-MCV2 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| District | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Average | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Average | Dropout Rate (2014) |

| Alba | 78 | 76 | 71 | 75 | 95 | 90 | 77 | 87 | −8% |

| Arad | 89 | 85 | 79 | 84 | 67 | 66 | 56 | 63 | 28% |

| Arges | 94 | 89 | 88 | 90 | 89 | 93 | 86 | 89 | 3% |

| Bacau | 93 | 89 | 87 | 90 | 89 | 88 | 78 | 85 | 10% |

| Bihor | 94 | 92 | 89 | 92 | 97 | 95 | 95 | 95 | −7% |

| Bistrita | 95 | 98 | 94 | 96 | 98 | 97 | 94 | 96 | 0% |

| Botosani | 91 | 89 | 89 | 90 | 97 | 95 | 86 | 93 | 4% |

| Braila | 84 | 95 | 94 | 91 | 93 | 91 | 88 | 90 | 6% |

| Brasov | 89 | 87 | 85 | 87 | 95 | 88 | 83 | 89 | 3% |

| Bucuresti | 97 | 92 | 91 | 93 | 81 | 77 | 69 | 76 | 25% |

| Buzau | 91 | 94 | 90 | 92 | 94 | 96 | 93 | 95 | −3% |

| Calarasi | 88 | 91 | 88 | 89 | 100 | 87 | 65 | 84 | 26% |

| Caras | 83 | 90 | 91 | 88 | 79 | 75 | 56 | 70 | 38% |

| Cluj | 86 | 87 | 83 | 85 | 91 | 85 | 82 | 86 | 1% |

| Constanta | 97 | 90 | 88 | 92 | 91 | 87 | 77 | 85 | 13% |

| Covasna | 96 | 93 | 94 | 94 | 88 | 87 | 74 | 83 | 21% |

| Dimbovita | 97 | 87 | 97 | 94 | 92 | 88 | 76 | 85 | 22% |

| Dolj | 95 | 95 | 93 | 94 | 94 | 96 | 96 | 95 | −4% |

| Galati | 94 | 92 | 91 | 92 | 91 | 90 | 79 | 87 | 13% |

| Giurgiu | 95 | 96 | 98 | 96 | 71 | 90 | 76 | 79 | 22% |

| Gorj | 92 | 91 | 89 | 91 | 87 | 91 | 81 | 87 | 9% |

| Harghita | 97 | 93 | 94 | 95 | 98 | 95 | 94 | 96 | 0% |

| Hunedoara | 74 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 75 | 78 | 53 | 68 | 26% |

| Ialomita | 90 | 85 | 84 | 86 | 91 | 91 | 85 | 89 | −1% |

| Iasi | 93 | 92 | 89 | 91 | 88 | 93 | 93 | 91 | −4% |

| Ilfov | 95 | 94 | 96 | 95 | 95 | 93 | 68 | 85 | 30% |

| Maramures | 96 | 95 | 90 | 94 | 96 | 96 | 91 | 94 | −2% |

| Mehedinti | 94 | 95 | 89 | 93 | 89 | 92 | 83 | 88 | 6% |

| Mures | 88 | 84 | 84 | 86 | 95 | 94 | 87 | 92 | −4% |

| Neamt | 85 | 78 | 77 | 80 | 88 | 87 | 65 | 80 | 15% |

| Olt | 95 | 94 | 91 | 93 | 98 | 98 | 91 | 96 | 0% |

| Prahova | 89 | 88 | 87 | 88 | 100 | 89 | 76 | 89 | 12% |

| Salaj | 86 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 96 | 95 | 89 | 93 | −10% |

| Satu Mare | 91 | 83 | 82 | 85 | 84 | 86 | 72 | 81 | 12% |

| Sibiu | 96 | 88 | 90 | 92 | 91 | 95 | 73 | 87 | 19% |

| Suceava | 91 | 86 | 82 | 86 | 99 | 87 | 98 | 95 | −20% |

| Teleorman | 100 | 86 | 86 | 91 | 96 | 91 | 93 | 93 | −8% |

| Timis | 83 | 77 | 76 | 79 | 83 | 81 | 71 | 79 | 7% |

| Tulcea | 93 | 98 | 90 | 94 | 99 | 98 | 91 | 96 | −1% |

| Vaslui | 95 | 91 | 89 | 92 | 73 | 88 | 67 | 76 | 24% |

| Vilcea | 96 | 97 | 94 | 95 | 98 | 98 | 86 | 94 | 8% |

| Vrancea | 94 | 96 | 92 | 94 | 96 | 93 | 90 | 93 | 3% |

3.4. Program Delivery

Between 2012 and 2014, almost all districts had a decreasing trend in both MCV1 (37 out of 42, 88%) and MCV2 (39 out of 42, 93%) coverage. The dropout rates for MCV1–MCV2 ranged from −20% in Suceava to 38% in Caras, with a median dropout of 6%. Seventeen districts received four out of four risk points for MCV1–MCV2 dropout of >10%. The dropout rates for MCV1–DPT ranged from −1% in Gorj to 15% in Hunedoara, with a median dropout of 5%.

3.5. Surveillance Quality

Fifteen out of the 42 (36%) districts had at least one suspected measles case during 2014. Of these suspected cases, the percentage that were adequately investigated (investigated within 48 hours of notification and data collected for 10 core variables) ranged from 29% in one district (Ialomita) to 100% in 11 districts. Four districts had timely laboratory results for 100% of suspected cases; seven districts had timely laboratory results for none of their suspected cases. All districts in Romania had a nonmeasles discarded rate of 0, so all districts received the maximum eight risk points for this indicator.

3.6. Threat Assessment

Risk points for threat assessment ranged from 1 to 16, out of a total possible 24 points. Fifteen out of 42 districts had evidence of recent measles cases (in 2014) among those <5 years of age, four districts had evidence of recent measles cases among those 5–14 years of age, and four districts had evidence of recent measles cases among those 15 years of age or older. Only one district (Bucharest) received the maximum risk points for population density >1,000 population per km2. The remainder of districts had a population density of <50 and received zero points (three districts), 50–100 and received one point (29 districts), or 101–300 and received two points (nine districts). Most districts (n = 33, 79%) bordered a district with at least one measles case in the past 12 months; these districts received two risk points each. The median number of vulnerable population groups in districts was three. The most common vulnerable population identified by districts was migrant/internally displaced populations, slum populations, or tribal communities; all but two districts were identified as containing migrant/internally displaced populations, slum populations, or tribal communities. Additionally, 38 districts had communities affected by security and safety concerns, and 36 districts had populations that were resistant to vaccination due to religious or cultural issues.

4. DISCUSSION

The measles risk assessment conducted in Romania was the first such assessment to be completed in a European country. In Romania, 27 of the 42 districts were classified as high risk or very high risk in 2015. Many districts had high risk scores for poor surveillance quality, reflecting a potential gap in the ability of districts to detect and confirm suspected cases rapidly and accurately. Out of 20 possible points, the range of districts’ surveillance quality scores was 8–20, with 29 of the 42 districts having the maximum score of 20. The high surveillance quality risk scores in most districts were influenced by the fact that Romania omits from its measles case-based data suspected cases that are IgM negative. There are no discarded cases recorded; thus, the discarded rate cannot be calculated at the district level. Additionally, the four surveillance quality indicators were defined in a way that if a district did not identify any suspected measles cases, it received maximum risk points for all four of the surveillance indicators. Only 15 out of the 42 districts identified any suspected measles cases during 2014; the remainder of districts received the maximum 20 risk points for the surveillance indicators.

Although vaccination coverage in Romania for first and second doses of MCV was relatively high historically, in recent years coverage for both doses has been falling. During 2011–2014, both MCV1 and MCV2 coverage were below the recommended ≥95% coverage target nationwide, and in 2014 only three districts had MCV1 coverage ≥95%. The districts with the poorest coverage had coverage of 71% and 53% for MCV1 and MCV2, respectively, far below recommended levels for measles elimination. Poor population immunity scores contributed to high overall risk scores for many of Romania’s districts. Waning confidence in vaccines has been identified as a reason for decreasing coverage in recent years.(12) A survey of parents conducted in 2015 found the most common reasons for not getting vaccinated were failure to attend a health-care clinic (37%) and refusal of vaccines (32%).

District risk scores were lowest for the threat assessment indicators (range 1–16 out of 24), with only five (12%) districts having a score of >12. These low scores in threat assessment reflected a lack of measles cases in any age group reported within 12 months before the assessment year in several districts, few identified high-risk groups, and relatively low population density for many districts.

The WHO risk assessment tool has a few limitations. First, the tool’s accuracy is dependent upon the quality of the data that are entered into the tool. The tool was designed to use readily available, routinely collected data including administrative vaccination coverage and SIA coverage data. If these data are poor quality, the risk assignments estimated by the tool may be unreliable. To improve reliability of the risk tool’s results, the highest quality data should be used for all inputs to ensure that estimates of risk are accurate. For example, district-level vaccination coverage estimates from population-based surveys could be used in place of administrative coverage estimates if they are expected to be more accurate. Another limitation of the tool is the lack of data from districts in bordering countries. Romania borders five different countries, across whose borders there is transit and immigration into Romania. Currently, the tool is unable to account for suboptimal vaccination coverage, recent measles cases, or outbreaks reported in neighboring countries. Migration and travel across neighboring countries has been associated with outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases in other countries, and ideally should be accounted for by the measles risk tool.(16)

Based on the results of this measles programmatic risk assessment, risk could be reduced through improvements to the case-based surveillance system in Romania. Surveillance activities should be reinforced at the district level, including reporting and conducting thorough investigations of all identified suspected cases. Zero reporting—regular reporting to the surveillance system even when there are no suspected cases identified—by all districts should be used as a method of continual monitoring of surveillance quality. Because recent decreases in MCV coverage have contributed to high risk scores in districts throughout Romania, targeted efforts to increase coverage to ≥95% should be made. In order to reduce vaccine refusal, pockets of unvaccinated persons need to be identified and should be targeted for future vaccination activities. Efforts should be made to improve parents’ knowledge of and confidence in vaccination benefits for their children in order to increase uptake of measles vaccine. WHOEUR has developed a guide for tailoring immunization programs to improve access, demand, and utilization of routine immunization services, which provides tools to identify susceptible populations and design strategies that are targeted to improve immunization among hard-to-reach populations.(17) This guide could be useful in Romania to develop and implement a communication plan to increase understanding of the importance of vaccination and reduce uninformed vaccine refusals.

Sustained transmission of measles in a country can lead to importation of cases into other countries in the region and beyond, causing outbreaks and hampering elimination efforts. During 2008–2010, a measles outbreak first detected in the ethnic minority Roma population in Germany spread to Bulgaria and then to 11 other countries in Europe, including Romania.(18,19) Although the measles risk tool is designed to measure measles-specific risk, its results may additionally indicate weaknesses in a country’s routine immunization service delivery in general. This is due to the highly infectious nature of measles and a highly effective measles vaccine, allowing for measles epidemiology and susceptibility in the population to expose weaknesses within immunization programs. When there are gaps in immunization coverage in general, measles is frequently the first vaccine-preventable disease detected, indicating areas of low vaccination coverage in the country that need to be addressed. Thus, weaknesses in a country’s immunization program that are highlighted by the risk tool as high-risk status for measles may also be indicative of risk for other vaccine preventable diseases. In Romania, measles outbreaks occurred concurrently with rubella outbreaks during 2011–2012,(10,20) and with mumps outbreaks during 2005–2007.(11)

Annual assessments using the WHO measles programmatic risk tool could provide valuable information for EPI and surveillance staff at the national and district levels to guide activities to enhance measles elimination efforts, such as strengthening routine immunization services, improving SIA planning, and intensifying surveillance. The score breakdowns by indicator category produced by the risk tool allow for a careful and in-depth examination of the main reasons for high risk scores, and information that can be used to determine the specific reasons why a district may be at risk for an outbreak.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank the epidemiologist-physicians from all public health districts in Romania who contributed data to this study.

Funding:

This project was supported by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. This research was supported in part by an appointment to the Research Participation Program at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and CDC.

Footnotes

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Declaration of interests: None of the authors have a commercial or other financial interest associated with the information presented in this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Global Vaccine Action Plan 2011–2020, 2013.

- 2.Perry RT, Murray JS, Gacic-Dobo M, Dabbagh A, Mulders MN, Strebel PM, Okwo-Bele JM, Rota PA, Goodson JL. Progress toward regional measles elimination—Worldwide, 2000–2014. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Report, 2015; 64(44):1246–1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muscat M, Shefer A, Ben Mamou M, Spataru R, Jankovic D, Deshevoy S, Butler R, Pfeifer D. The state of measles and rubella in the WHO European Region, 2013. Clinical Micro-biology and Infection, 2014; 20(Suppl 5):12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Regional Committee for Europe. Sixtieth session. Renewed commitment to elimination of measles and rubella and prevention of congenital rubella syndrome by 2015 and sustained support for polio-free status in the WHO European region 2010. Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/119546/RC60_edoc15.pdf, Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 5.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Implementing the ECDC Action Plan for Measles and Rubella. Available at: http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/measles-rubella-implementing-action-plan.pdf, Accessed March 3, 2016.

- 6.World Health Organization. Eliminating measles and rubella and preventing congenital rubella infection. WHO European region strategic plan 2005–2010. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO Regional Office for Europe. Third meeting of the European Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination (RVC). Available at: http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/275519/3rd-Meeting-European-RVC-Measles-Rubella-Elimination.pdf?ua=1, Accessed December 11, 2015.

- 8.United Nations. Population Division. The World Population Prospects—2012 revision New York, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations. United Nations Statistics Division. Country profile, Romania. Available at: http://data.un.org/CountryProfile.aspx?crName=Romania, Accessed December 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stanescu A, Janta D, Lupulescu E, Necula G, Lazar M, Molnar G, Pistol A. Ongoing measles outbreak in Romania, 2011. Euro Surveillance, 2011; 16(31):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.World Health Organization. WHO vaccine-preventable diseases: Monitoring system. 2015 global summary. Available at: http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/incidences?c=ROU, Accessed December 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.National Centre for Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Control. Vaccination coverage evaluation, February 2015. Romania, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.World Health Organization. Immunization, Vaccines and Biologicals. Data, statistics and graphics. Retrospective measles data on supplementary immunization activities 2000–2015 http://www.who.int/immunization/monitoring_surveillance/data/en/, Accessed December 10, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lam E, Schluter WW, Masresha BG, Teleb N, Bravo-Alcantara P, Shefer A, Jankovic D, McFarland J, Elfakki E, Takashima Y, Perry RT, Dabbagh AJ, Banerjee K, Strebel PM, Goodson JL. Development of a district-level programmatic assessment tool for risk of measles virus transmission. Risk Analysis, 2015; epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Institutul National de Sǎnǎtate Publicǎ Romania. Measles and rubella surveillance methodology. Available at: http://www.cnscbt.ro/index.php/metodologii/rujeola-si-rubeola, Accessed December 10, 2015.

- 16.World Health Organization, United Nations High Commission on Refugees, and UNICEF. Joint statement on general principles on vaccination of refugees, asylum-seekers and migrants in the WHO European region. November 2015.

- 17.World Health Organization, European Regional Office. The guide to tailoring immunization programmes (TIP): Increasing coverage of infant and child vaccination in the WHO European region. 2013.

- 18.Mankertz A, Mihneva Z, Gold H, Baumgarte S, Baillot A, Helble R, Roggendorf H, Bosevska G, Nedeljkovic J, Makowka A, Hutse V, Holzmann H, Aberle SW, Cordey S, Necula G, Mentis A, Korukluoǧlu G, Carr M, Brown KE, Hübschen JM, Muller CP, Mulders MN, Santibanez S. Spread of measles virus D4—Hamburg, Europe, 2008–2011. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 2011; 17(8):1396–1401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Santibanez S, Hübschen JM, Muller CP, Freymuth F, Mosquera MM, Mamou MB, Mulders MN, Brown KE, Myers R, Mankertz A. Long-term transmission of measles virus in central and continental Western Europe. Virus Genes, 2015; 50(1):2–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janta D, Stanescu A, Lupulescu E, Molnar G, Pistol A. Ongoing rubella outbreak among adolescents in Salaj, Romania, September 2011–January 2012. Euro Surveillance, 2012; 17(7):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]