Significance

The development of a simple, versatile, and highly efficient nucleic acid detection assay is of utmost importance for the detection and control of infectious diseases. In this study, a photocontrolled CRISPR detection technology was developed to solve the compatibility problems of nucleic acid amplification–based CRISPR detection. We further showed that the sensitivity of the photocontrolled CRISPR detection technology was more than two orders of magnitude better than that of the conventional one-pot CRISPR detection technology. In addition, the photocontrolled CRISPR detection technology is as simple as the conventional technology, except that it requires a 30-s ultraviolet irradiation step. Overall, this work clears a key hurdle in the commercial application of nucleic acid amplification–based CRISPR technology.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas12a, nucleic acid detection, RPA, PC linker, one-pot assay

Abstract

CRISPR diagnostics based on nucleic acid amplification faces barriers to its commercial use, such as contamination risks and insufficient sensitivity. Here, we propose a robust solution involving optochemical control of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) activation in CRISPR detection. Based on this strategy, recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) and CRISPR-Cas12a detection systems can be integrated into a completely closed test tube. crRNA can be designed to be temporarily inactivated so that RPA is not affected by Cas12a cleavage. After the RPA reaction is completed, the CRISPR-Cas12a detection system is activated under rapid light irradiation. This photocontrolled, fully closed CRISPR diagnostic system avoids contamination risks and exhibits a more than two orders of magnitude improvement in sensitivity compared with the conventional one-pot assay. This photocontrolled CRISPR method was applied to the clinical detection of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA, achieving detection sensitivity and specificity comparable to those of PCR. Furthermore, a compact and automatic photocontrolled CRISPR detection device was constructed.

Rapid, sensitive, and specific nucleic acid testing is the most effective way to control the spread of infectious diseases. Existing nucleic acid tests still rely heavily on the PCR method, a technique invented 37 years ago (1). The PCR method has good sensitivity and specificity, but its application scenarios are usually limited to central laboratories. The COVID-19 pandemic has awakened us to the fact that there is a great need for nucleic acid tests, which are in demand almost everywhere in the world (2–4). In view of this, the development of new-generation nucleic acid detection technology will focus on improved ease of use, more flexible application scenarios, and better parameters (speed, sensitivity, and specificity) (5, 6).

One achievement in this respect is the invention and improvement of isothermal nucleic acid amplification (INA) technologies, such as loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) (7, 8), recombinase polymerase amplification (RPA) (9), strand displacement amplification (SDA) (10, 11), helicase-dependent isothermal DNA amplification (HDA) (12, 13), and exponential amplification reaction (EXPAR) (14). INA only requires simple temperature control modules; therefore, it has significant advantages in the development of more portable devices. In addition, INA is usually faster than PCR. However, two key factors affecting the widespread adoption of INA are its sensitivity and specificity, which are hardly comparable to those of PCR. One recent encouraging development is that the combination of INA and CRISPR detection has shown significant potential to remove the obstacles to their application (15–29). CRISPR technology was originally developed for gene editing but has recently shown great molecular diagnostic application potential due to the discovery of trans cleavage mechanisms in Cas12 and Cas13 systems (16, 18, 26, 30–34). These advantages are reflected in the following aspects. 1) The reaction temperature of the CRISPR system is usually compatible with INA. For example, the optimum reaction temperature of Cas12a and Cas13a is 37 °C, which is compatible with RPA. Cas12b (35–37), a more heat-resistant CRISPR system, is compatible with LAMP technology in terms of reaction temperature. 2) Cas12 and Cas13 systems have an extremely efficient trans cleavage mechanism (up to 10,000-fold trans cleavage efficiency mediated by cis recognition) (32, 34). This unique signal amplification capability is very beneficial for improving the detection sensitivity of INA technology (16, 18, 19, 26). 3) The cis recognition–mediated trans cleavage mechanism is highly sequence-dependent, which gives CRISPR detection excellent specificity (16, 26, 31–33). Therefore, the CRISPR assay can improve the specificity of the conventional INA assay, which is often plagued by nonspecific amplification or primer dimer formation (38, 39).

Despite the highly intensive development, CRISPR diagnostic technology based on INA still faces challenges in clinical application. One of the major problems is the inhibition of INA by CRISPR cis and trans cleavage, resulting in low detection efficiency. For example, in the widely developed RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a approach, because both RPA and the CRISPR-Cas12a system act on the same targeted region, CRISPR-Cas12a cis cleavage results in the loss of the nucleic acid template used for isothermal amplification. On the other hand, the activation of the trans cleavage of the CRISPR-Cas12a system also leads to the degradation of single-chain INA primers, which also leads to negative effects on amplification efficiency. Some early CRISPR diagnostic techniques, such as SHERLOCK (18, 19), DETECTOR (16), and HOLMES (26), separated the nucleic acid amplification and CRISPR detection steps to achieve high detection sensitivity. However, this scheme not only complicates the operation procedure but also suffers from cross-contamination caused by liquid transfer. Very recently, several studies have attempted to address this problem by integrating INA and CRISPR detection into a closed system. These include physical isolation of INA systems and CRISPR assays (40–44), optimization of CRISPR component concentrations to reduce INA inhibition (45), or design of crRNA independent of protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sites for one-pot detection (46). While progress has been made, these methods still require either extra operational steps or complex microfluidic designs, or their universality has not been demonstrated.

Photocontrolled techniques allow control of chemical reactions in a very fast (usually a few seconds) and contactless manner. This strategy has been widely employed to spatiotemporally regulate the CRISPR-Cas9 system to prevent off-target reactions (47–58). However, to the best of our knowledge, the exploitation of photocontrolled technology in the CRISPR detection field has not been reported. In addition, whether similar photocontrolled techniques used with CRISPR-Cas9 will also be able to control Cas12 and Cas13 systems with cis and trans cleavage mechanisms is unknown. Here, we propose an optochemical technique to build robust CRISPR diagnostic methods. In this technique, the CRISPR-Cas12a system is blocked by a photocleaved linker containing CRISPR RNA (crRNA) to silence the nucleic acid sequence. Therefore, in the one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a system, the silent CRISPR-Cas12a system does not interfere with RPA. When RPA is complete, the CRISPR-Cas12a detection system can be activated rapidly (a few seconds) by light irradiation. This photoresponsive CRISPR-Cas12a detection system ensures that all components are added to a closed system in one step and thus avoids the risk of contamination. This photoresponsive detection system also separates RPA and CRISPR-Cas12a detection in the time dimension, thus ensuring high detection efficiency. It is demonstrated that this improved CRISPR diagnostic technique is at least two orders of magnitude more sensitive than the conventional one-pot method and comparable to the conventional two-step method. The sensitivity and specificity of the method were equal to those of qRT-PCR based on the comparative analysis of 60 clinical COVID-19 samples. Furthermore, a compact and automatic photocontrolled CRISPR-Cas12a detection device was constructed.

Results

Construction of a Photocontrolled CRISPR-Cas12a System.

Previous studies have shown that gene editing by the CRISPR-Cas9 system can be regulated by light irradiation (47–65). These regulatory systems are based either on blocking Cas9 protein function via site-specific installation of a photocaged amino acid (55, 58–64) or on silencing of its guide RNA (47–54, 56, 57). Unlike the Cas9 system, the Cas12 system presents both cis DNA recognition cleavage and trans cleavage mechanisms (16, 26, 33). Recently, a light-controlled method was developed for modulating the expression of Cas12a and its gene-editing ability (66), but the direct light regulation of the cis and trans cleavage activity of the Cas12 systems has not been reported. Considering the great potential of the Cas12a system for next-generation nucleic acid detection, we sought to achieve light regulation of its cis and trans cleavage activity to construct a photocontrolled CRISPR-Cas12a system.

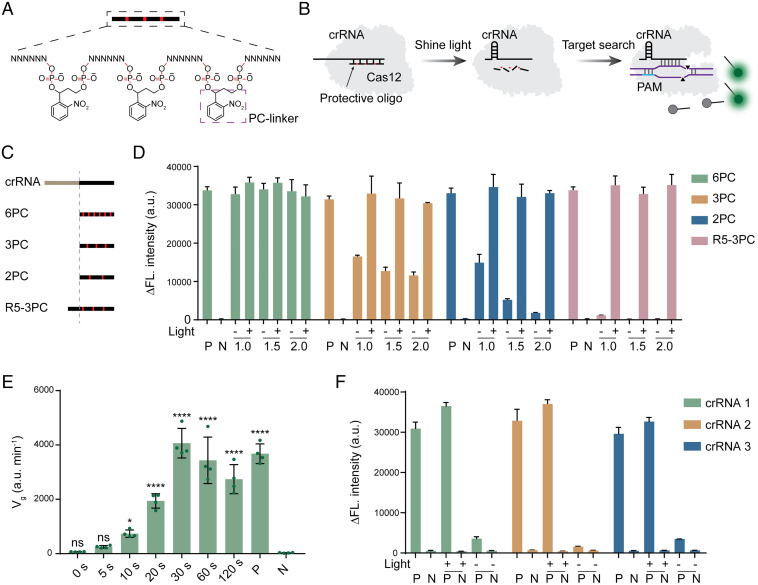

Considering the convenience of nucleic acid chemical synthesis, we designed nucleic acid strands containing photocleavable (PC) linkers to silence the crRNA of the Cas12 system (Fig. 1A). We used LbCas12a (67), the most effective Cas12 detection system reported thus far, as the model to confirm its validity (Fig. 1B). The crRNA of the LbCas12a system contains a 21-base-length repetitive (R) region and a spacer (S) region ∼20 bases in length (16). We first evaluated whether crRNA activity could be blocked by destroying the crRNA structure using complementary DNA. We designed single-stranded DNAs that were completely or partially paired with the R region, partially paired with the S region, or partially paired with both the R and S regions to evaluate their blocking effect (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Using a well-approved fluorescence method (Fig. 1B), we found that none of these designed DNA sequences could completely block the trans cleavage activity of the Cas12 system (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Since blocking the R region of crRNA alone does not appear to effectively inhibit Cas12 activity, we attempted to block the S region with RNA sequences. Due to the low effective cleavage of the RNA target by the Cas12 system (68), we could design single-stranded RNAs that were fully paired to the S region of the crRNA. In the subsequent experiments, four protective RNAs (p-RNAs) (6PC, 3PC, 2PC, and R5-3PC) were designed to evaluate their blocking effect (Fig. 1C). Three of these RNA sequences, containing 6, 3, and 2 PC linkers, were 20 bases in length and were fully paired to the S region of the crRNA. The RNA sequence had three PC linkers and contained five additional bases that complemented the R region. Using a fluorescent LbCas12a assay, it was found that 6PC had almost no blocking effect and that 3PC and 2PC only exhibited partial blocking even if the concentration ratio was excessive (Fig. 1D). R5-3PC almost completely blocked the activity of Cas12a at two concentration ratios, and the trans cleavage activity of the Cas12a protein was not activated (Fig. 1D). A noncomplementary p-RNA did not silence Cas12a activity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Further experimental data demonstrated that the p-RNA was degraded and separated from the crRNA under light irradiation (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). It is worth noting that Cas12a activity could be completely restored with all the p-RNA sequences under 365-nm light irradiation (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Design and validation of the photocontrolled CRISPR-Cas12a detection concept. (A) Structural diagram of protective oligonucleotides. Protective oligonucleotides are linked by a spaced PC linker. (B) Design of the photocontrolled CRISPR-Cas12a detection concept. Protective oligonucleotides are designed to be partially paired with crRNA, thus disrupting the structure of crRNA. Disorganized crRNA will not mediate the recognition and cleavage of target DNA by the Cas12a system. The PC linker breaks when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) light at 365 nm. Destructive protector nucleotides are separated from crRNA, thus restoring the function of CRISPR-Cas12a detection. (C) Four p-RNAs are designed to silence crRNA. Three were designed to be completely complementary to the spacer sequence of crRNA but with varied numbers of PC linkers (6PC, 3PC, and 2PC). A sequence is designed to complement the spacer sequence with three PC linkers and with an additional 5 bases complemented to the repeat region of crRNA (R5-3PC). (D) Evaluation of the crRNA silencing and photoresponse efficiency of four p-RNAs. In each p-RNA test, the concentration ratio of p-RNA and crRNA was set as 1:1, 1.5:1, and 2:1, respectively. A corresponding target DNA (1 nM) is used for CRISPR-Cas12a detection; “−” indicates without light irradiation, and “+” indicates light radiation. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) (n = 3 technical replicates). (E) Effect of light irradiation time on recovery efficiency of CRISPR-Cas12a detection. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) (n = 4 technical replicates). ****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; ns, not significant. (F) Validation of the universality of the p-RNA design. Three crRNAs with different spacer sequences were designed to identify the generality of the silencing efficiency of R5-3PC. P and N represent positive and negative control without p-RNA and light irradiation treatment. Δfluorescence (ΔFL.) intensity represents the difference between the 60-min fluorescence value and the initial fluorescence value. a.u., arbitrary units. Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) (n = 3 technical replicates).

After completing the design of the p-RNA sequence, we next evaluated the optimal time of light irradiation. The results showed that 30 s was enough to obtain full recovery of Cas12a activity (Fig. 1E). Furthermore, we wondered whether such an R5-3PC p-RNA design strategy would be universal to other crRNAs. We evaluated three additional CRISPR-Cas12a detection systems containing different crRNAs and designed corresponding p-RNAs based on the R5-3PC rule. The results showed that these systems exhibited good performance in photoinduced activity recovery, which preliminarily proved the universality of the design criterion (Fig. 1F). We further demonstrated that this photochemical control method is wavelength-selective. No significant disinhibition phenomenon was observed after irradiating the p-RNA–crRNA complex with ambient light for 8 h, indicating that this control strategy is stable under daily operation and storage (SI Appendix, Fig. S4).

Development of a Photocontrolled One-Pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA Assay.

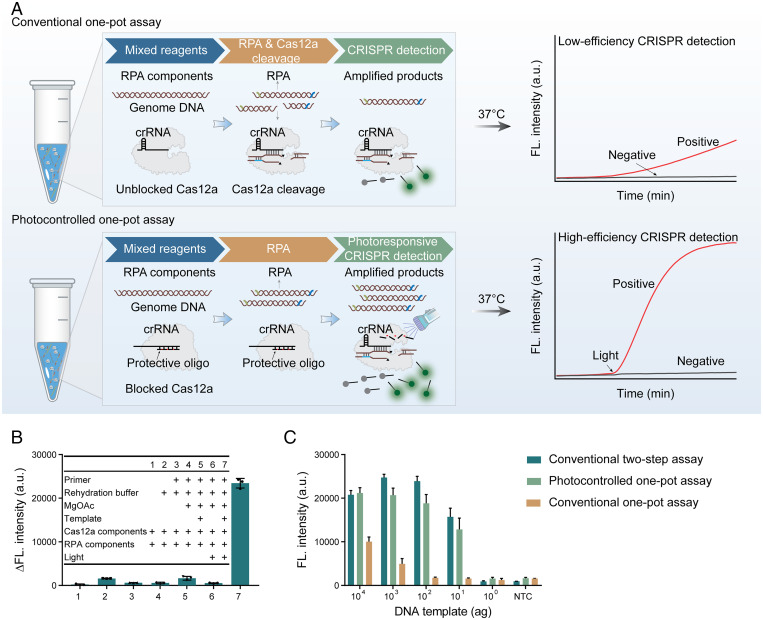

Nucleic acid detection technology based on the CRISPR-Cas12a system has developed rapidly in recent years (20, 22, 27, 28). In particular, the combination of CRISPR-Cas12a and INA can improve the sensitivity and specificity of conventional methods. However, a key problem hindering its applicability is the incompatibility of these two reactions. Specifically, for example, in the conventional one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA assay, the cis and trans cleavage reaction of the CRISPR-Cas12a system will result in the destruction of the template and primer for the RPA reaction, resulting in inefficient detection (Fig. 2A). Physical segmentation of the RPA reaction and CRISPR-Cas12a detection easily leads to aerosol contamination and complicates the operation procedure. Here, we developed a photocontrolled one-pot CRISPR detection method to address this application challenge. In this one-pot approach, the CRISPR-Cas12a system is temporarily blocked, so the RPA reaction is not affected. After the RPA reaction is completed, the CRISPR-Cas12a system is activated rapidly under 365-nm light irradiation. Such a detection system is efficient because it combines the advantages of RPA and CRISPR-Cas12a detection (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Development of the photocontrolled one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA assay. (A) Design and comparison of the conventional RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA assay and photocontrolled RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA assay. For the conventional one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA assay, cis recognition and cleavage of target DNA by CRISPR-Cas12a will lead to the loss of template and primer for the RPA reaction and thus lead to low detection efficiency. For the photocontrolled one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA assay, CRISPR-Cas12a detection is temporarily silenced and can be rapidly activated by light irradiation when the RPA reaction is complete. The photocontrolled assay has high detection efficiency because the RPA reaction is not affected. (B) Reaction component deletion experiments for corroborating the photocontrolled one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA assay concept. Δfluorescence intensity represents the difference between the 90-min fluorescence value and the initial fluorescence value. (C) Comparison of the detection efficiency of the photocontrolled one-pot assay, the conventional two-step assay, and the conventional one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a DNA assay using gradient diluted plasmid DNA as a template. NTC, nontemplate control (n = 3 technicalreplicates). Data are represented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.) (n = 3 technical replicates).

Next, we validated this photocontrolled CRISPR detection concept using reaction component deletion experiments. The results showed that CRISPR-based detection can only be initiated by light irradiation and that the response is very specific (Fig. 2B). We predicted that photocontrolled CRISPR detection will improve the sensitivity of the conventional one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay. In view of this, we used gradient diluted plasmid DNA as a template to test the efficiency of the conventional and photocontrolled RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a methods in parallel. The results showed that both the photocontrolled CRISPR method and the conventional two-step method could reliably detect plasmid DNA at as low as 10 attogram (ag), while the conventional one-pot CRISPR method could only detect plasmid DNA at 103 ag (Fig. 2C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The results indicated that the photocontrolled method was at least two orders of magnitude more sensitive than the conventional one-pot method, and its sensitivity was equivalent to that of the conventional two-step method. It is worth noting that these same gradients of diluted DNA templates were also tested using a commercial SYBR dye–based PCR kit, obtaining a sensitivity of 100 ag (SI Appendix, Fig. S6). These data indicated that the photocontrolled RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a method was an order of magnitude more sensitive than the SYBR-based PCR method for DNA detection.

Development of a Photocontrolled One-Pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a Assay for SARS-CoV-2 RNA Detection.

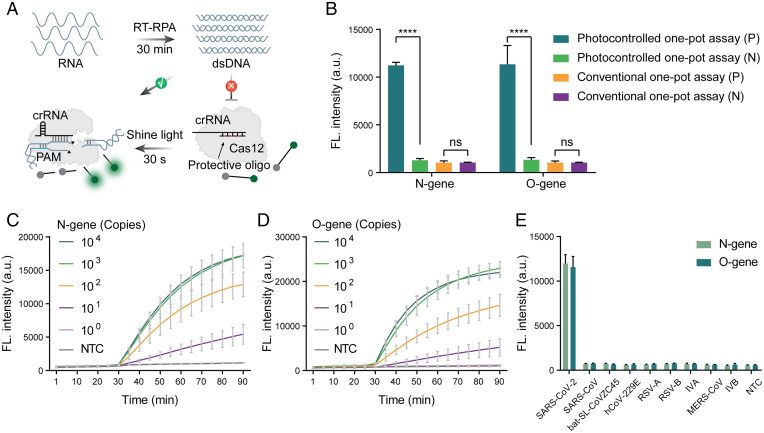

Due to the significant improvement in sensitivity of the photocontrolled CRISPR detection method, we applied it to develop a severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) RNA detection method. Similar to DNA detection, RNA detection can also be performed using RPA reactions in addition to adding reverse transcriptase to the system. In the photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay, the reverse-transcription RPA (RT-RPA) reaction can be performed in advance so that the initial amplification products are not cut by the CRISPR-Cas12a system, giving the method high detection efficiency (Fig. 3A). We used 100 copies of the O gene and N gene of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, which are difficult to detect by the conventional one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay, as the test template to evaluate the improved efficiency. The results showed that even at such a low template concentration, the photocontrolled method obtained significant detection signals (Fig. 3B). Two gene templates with gradient dilution were further tested, and 10 copies of both genes could be reliably detected (Fig. 3 C and D). The same gene templates were then detected with a China Food and Drug Administration (CFDA)–approved SARS-CoV-2 qRT-PCR kit, and a limit of detection of 10 copies was obtained (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), which indicates that the photocontrolled CRISPR detection method was similar in detection efficiency to the clinically used PCR kit. To evaluate the analytical specificity of this developed SARS-CoV-2 RNA assay, we performed RNA template testing for other respiratory viruses by employing an RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay system corresponding to O and N gene detection. The results showed that it was difficult to distinguish bat-SL-CoVZC45 and SARS-CoV from SARS-CoV-2 using only RPA primers for the N gene (SI Appendix, Fig. S8). However, in combination with the CRISPR assay, excellent assay specificity was obtained for all detected respiratory virus RNAs (Fig. 3E).

Fig. 3.

Development of the photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection. (A) Workflow of SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection using the photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay. (B) Comparison of the detection efficiency between the photocontrolled and conventional one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assays in analyzing 100 copies of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. ****P < 0.0001; ns, not significant. (C and D) Photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay for detection of gradient diluted N gene (C) and O gene (D) of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. (E) The specificity of the photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay in the analysis of SARS-CoV-2 RNA against other coronaviruses and human respiratory virus (SARS-CoV, bat-SL-CoVZC45, hCoV-229E, RSV-A, RSV-B, IVA, IVB, and MERS-CoV). Values represent mean ± SEM from three replicates.

Clinical SARS-CoV-2 RNA Sample Detection.

The analytical sensitivity of the photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay was further compared with that of a CFDA-approved qRT-PCR method, conventional one-pot assay, and conventional two-step assay for the detection of clinical SARS-CoV-2 RNA samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). A total of 19 clinical RNA samples collected in Wuhan during 2020 were tested. Due to limited sample volume, only the O gene was detected by three CRISPR-based methods. Cycle threshold (Ct) values obtained by a CFDA-approved qRT-PCR diagnostic kit for the detection of O genes were used to indicate the relative concentration of RNA samples and for the determination of negative and positive results. As recommended by the kit, samples with measured Ct values less than or equal to 38 were considered positive. Ct values between 38 and 40 were considered suspiciously positive or weakly positive; thus, remeasurement was recommended. A Ct value greater than 40 was considered negative. As shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S9 and Table S1, the Ct value obtained by qRT-PCR showed that 16 of 19 tested samples were positive, 2 samples were suspiciously positive, and 1 sample was negative. The conventional one-step method was not effective in clinical low-concentration sample analysis (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). It can also be seen that both the photocontrolled one-pot assay and conventional two-step assay worked well for most of these samples (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). However, a suspiciously positive sample with a Ct value of 39.46 was not successfully identified by the photocontrolled one-pot assay, while the conventional two-step assay failed to detect these two suspiciously positive samples (sample IDs 1 and 2, with Ct values of 38.12 and 39.46, respectively).

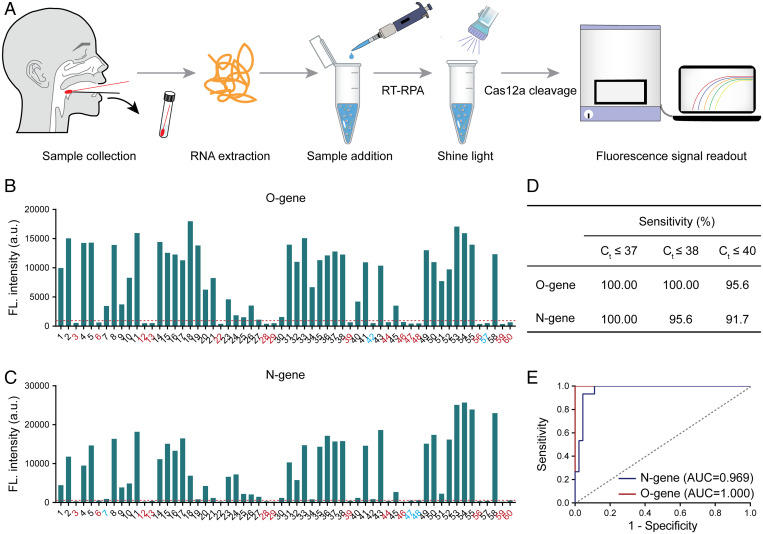

To further evaluate the clinical detection performance, the photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay was employed for O gene and N gene analysis in an additional 60 clinical SARS-CoV-2 RNA samples (Fig. 4A). According to the results of qRT-PCR, the Ct value range of the N gene was 19.07 to 39.16, and that of the O gene was 20.11 to 40.39 (SI Appendix, Figs. S10–S12 and Table S2). The fluorescence signal intensities for the O gene and N gene with the photocontrolled one-pot assay are shown in Fig. 4 B and C, respectively. The identification of positive and negative samples was based on a set of threshold values, which represent the mean plus 3 SDs of the nontemplate control. Compared with the qRT-PCR detection method, the photocontrolled method reliably detected all samples with Ct values less than or equal to 37 (Fig. 4D). We achieved 100 and 95.6% sensitivity for samples with Ct values less than or equal to 38 for the analysis of the O gene and N gene, respectively (Fig. 4D). A detection sensitivity greater than 90% was also obtained when Ct values were less than or equal to 40 (Fig. 4D). It should be noted that samples with Ct values between 38 and 40 required remeasurement. However, due to the lack of sufficient clinical sample volume, these data were only obtained via a single measurement. Regardless, the photocontrolled method achieved a sensitivity that was very close to that of the gold standard qRT-PCR assay. Using a Ct value of 38 as the judgment criterion, the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of the photocontrolled method showed an AUC (area under the curve) of 1.0 and 0.969 for the O gene and N gene, respectively, in this study (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a assay for detection of clinical SARS-CoV-2 RNA samples. (A) Schematic of clinical diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 by the current developed photocontrolled CRISPR technique. SARS-CoV-2 RNAs extracted from clinical nasopharyngeal swab samples were added to the RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a kit tubes. The RT-RPA and CRISPR-Cas12a reactions then work sequentially by light regulation. Detection results are obtained by evaluating real-time fluorescence signal readout. (B and C) The developed photocontrolled CRISPR technique is employed for the detection of the O gene (B) and N gene (C) in 60 clinical SARS-CoV-2 RNA samples. Negative samples are highlighted in red. Suspiciously positive samples are highlighted in blue. (D) The sensitivity of the photocontrolled CRISPR technique was evaluated by clinically approved qRT-PCR kits based on measured Ct values. (E) ROC curve analysis of the detection accuracy in clinical applications. The threshold lines (red dotted lines) in B and C represent the threshold for a positive sample, which was calculated from the mean plus 3 SDs of NTC.

Construction of a Compact Photocontrolled CRISPR Detection Device.

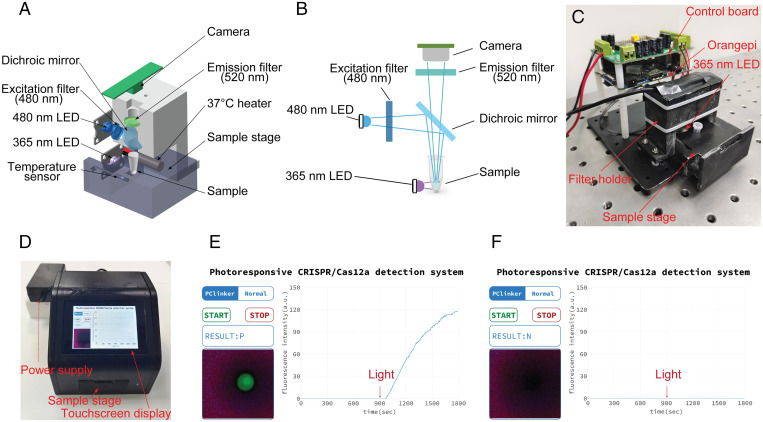

Based on the above experimental results, we proved that the photocontrolled CRISPR detection technology achieved a significant improvement in sensitivity compared with the conventional CRISPR detection method. The photocontrolled CRISPR-Cas12a assay did not significantly increase the complexity of detection procedures compared with the conventional one-pot version. In the next experiment, we demonstrated that a CRISPR detection instrument with photocontrolled technology was very easy to construct. To facilitate the promotion and commercialization of this technology, we designed and constructed a compact photocontrolled CRISPR detection system. The core components and optical paths of the detection system are shown in Fig. 5 A and B. In brief, the device mainly includes an optical system and a temperature control system. In the optical system, we used a 480-nm light-emitting diode (LED) light source as the fluorescence excitation module and a 365-nm LED as the optical module for cleavage of the PC linker. These two light sources were fitted to the lateral position of the test tube to illuminate the detection system. An imaging camera was mounted directly above the test tube to output visual photos and real-time fluorescence curves. The temperature control module was located at the orientation to control the optimal temperature for RPA and CRISPR detection. Timing control for all these components was accomplished through a single-board computer.

Fig. 5.

Construction of a compact photocontrolled CRISPR-Cas12a detection device. (A) Simplified schematic diagram of the optical system, heating system, and imaging modules. (B) Schematic diagram of the optical path of the optical system. (C) Internal structure of the instrument. (D) Physical photo of the assembled detection device. (E) A typical detection result based on the photoresponsive CRISPR-Cas12a detection system. An automatic procedure consisted of 15 min of isothermal amplification, 30 s of 365-nm light irradiation, and then 14 min 30 s of CRISPR-Cas12a detection. The results can be directly observed by fluorescence imaging of the reaction tube or by monitoring fluorescence curves. (F) Test results using negative samples under the same conditions.

We used three-dimensional (3D) printing technology to prepare all the brackets and shells for fixing and assembling these components (Fig. 5C). To simplify the operation, we designed a touchscreen-based man–machine interface. After the test tube is put into the sample table and the START button is clicked, the following RPA amplification (15 min), 365-nm ultraviolet (UV) excitation (30 s), and CRISPR detection (14 min 30 s) procedures (Fig. 5D) are performed automatically. The display interface of a typical detection result is shown in Fig. 5E. In this photocontrolled detection system, fluorescence imaging photos of a test tube and real-time results of fluorescence curve changes are both displayed on the touchscreen panel, and the corresponding negative control test results are shown in Fig. 5F.

Discussion

At present, nucleic acid testing remains the most effective way to prevent and control COVID-19 and, potentially, new infectious diseases in the future (3–5). There is still an urgent need to develop nucleic acid detection technology that can be used independent of central laboratories and in multiple application scenarios. Compared with PCR, INA is faster and only requires simple detection instruments, but it is usually less sensitive and specific than PCR. CRISPR is expected to revolutionize the current nucleic acid detection technology, but there are still obstacles to its commercial application. For example, combining the CRISPR-Cas12a assay with INA, such as RPA, improves its sensitivity and specificity, but these two reactions need to be performed in a stepwise manner due to low reaction compatibility (16). Such a two-step reaction strategy would be difficult to commercialize due to the complexity of testing procedures and contamination risks. Sensitivity is often very low when RPA and CRISPR-Cas12a are integrated into a single-tube system (45). Although subsequent studies demonstrated that sensitivity could be improved by intensive optimization of the reaction system (45, 69, 70), the detection efficiency of the CRISPR system was still significantly reduced. It is well-known that the trans cleavage mechanism of the Cas12 and Cas13 systems is very efficient, and thousands of substrate single-stranded DNAs or RNAs can be cleaved after cis recognition of a single target DNA or RNA (32, 34). Therefore, in principle, CRISPR detection technology will be ultrasensitive if the compatibility of the CRISPR detection system and isothermal amplification can be addressed.

In this study, we invented a photocontrolled CRISPR detection technology to solve this problem. In this design, CRISPR-Cas12a activity is blocked by a PC linker containing a protective nucleic acid strand to temporarily silence the function of crRNA. In this way, in a one-pot RPA and CRISPR detection system, the two reactions can be separated in time to avoid the amplification inhibition caused by the CRISPR cleavage reaction. We successfully screened out a general p-RNA (R5-3PC) based on this design principle and achieved almost complete inhibition and photoregulated restoration of crRNA activity in the CRISPR-Cas12a system. Our experiments also demonstrated that this principle can be universally adopted for inhibiting and restoring crRNA targeting other nucleic acids. Because only 30 s of light irradiation is required to achieve full activity recovery, the introduction of light control does not significantly increase the time of each detection reaction when compared with conventional CRISPR detection systems. Without the need for direct contact, photocontrolled CRISPR detection technology is very simple to adopt, and the steps of lid opening and liquid transfer are not needed.

The introduction of photocontrolled technology is very significant in improving the sensitivity of DNA and RNA detection. We tested the plasmid DNA derived from the P72 gene sequence of the African swine fever virus and demonstrated an increase of two to three orders of magnitude in sensitivity compared with a conventional one-pot assay. These sensitivity values are also an order of magnitude higher than those of the qPCR technique with SYBR dye. A sample with a target of 100 copies of SARS-CoV-2 RNA, which is difficult to detect using the conventional one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a method, could be detected by the photocontrolled one-pot RT-RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a method with high signal quality. Nevertheless, we believe that there is room for efficiency improvement by systematic optimization of reaction components, such as RPA primer and crRNA sequences, reaction ions, pH, and component concentrations.

The clinical detection efficiency and accuracy of the photocontrolled CRISPR detection system have also been demonstrated. In comparison with the conventional two-step CRISPR detection system, the photocontrolled one-pot CRISPR detection system showed slightly better sensitivity for the O gene detection of 19 clinical SARS-CoV-2 samples. However, in the conventional two-step assay, the RT-RPA products need to be transferred into the LbCas12a cleavage reaction system by opening the lid of the reaction tube, which complicates the testing procedures and increases the risk of aerosol contamination. In addition, further experiments demonstrated that the photocontrolled CRISPR assay achieved satisfactory sensitivity and specificity by simultaneously analyzing the O gene and N gene in 60 clinical SARS-CoV-2 RNA samples. Setting a Ct value of 38 as a positive criterion, the photocontrolled CRISPR method achieved a sensitivity of 100% for the O gene and 95.6% for the N gene. Considering that the existing photocontrolled CRISPR detection system is still in the early stages of development, we believe that an equal or even superior detection performance to PCR will be achieved when all reagents and reaction conditions are carefully optimized.

The photocontrolled strategy is a simple, versatile, and efficient solution to the compatibility problems of INA and CRISPR detection. This advance clears a key hurdle in the commercial application of CRISPR technology. In addition, we showed the successful construction of a photocontrolled CRISPR detection device for potential future commercial applications. We demonstrated that the photocontrolled CRISPR detection step can be easily automated. Finally, although this study only showed the improvement of one-pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a technology, it is obvious that the current photocontrolled technique can also be applied to other isothermal amplification techniques, such as LAMP and EXPER, and other CRISPR detection systems, such as CRISPR-Cas13.

Materials and Methods

Materials Used for Biological Experiments.

All the DNA and RNA sequences were purchased from Sangon Biotech and are listed in SI Appendix, Table S3. All the plasmids were synthesized by Tsingke Biotechnology and are shown in SI Appendix, Table S3. SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase (200 U/μL) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. RNase H and NEBuffer 2.1 (10×) were purchased from NEB. TaKaRa Taq HS Perfect Mix, TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus), T7 RNA polymerase, recombinant RNase inhibitor, recombinant DNase I, and RNase-free water were purchased from Takara. NTP mixture was purchased from Sangon Biotech. 2019-nCoV RNA reference material (high concentration) used for measuring sensitivity was purchased from the National Institute of Metrology, Beijing, China. Pseudoviruses (human coronavirus 229E [hCoV-229E] pseudovirus, respiratory syncytial virus type A [RSV-A] pseudovirus, respiratory syncytial virus type B [RSV-B] pseudovirus, influenza A virus [IVA] pseudovirus, influenza B virus [IVB] pseudovirus, and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus [MERS-CoV] pseudovirus) used for measuring specificity were purchased from the National Standard Material Platform, Henan, China. The TwistAmp Basic Kit used for RPA (RT-RPA) was purchased from TwistDx. The MagZol Reagent Kit used for the RNA extraction from the pseudovirus was purchased from Magen Biotechnology. The QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit used for the SARS-CoV-2 RNA extraction was purchased from Qiagen. The COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) Nucleic Acid Test Kit used for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 clinical samples was a product from Wuhan Easy Diagnosis Biomedicine. LbCas12a protein was purchased from Guangzhou Bio-lifesci. The fluorescence signal was recorded by a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III (Takara).

Materials Used for the Construction of the Photocontrolled CRISPR Detection Device.

The 480- and 365-nm LEDs were purchased from Shenzhen Huataitong Electronic; 480- and 520-nm band-pass filters and dichroic mirrors were purchased from Hebei Guangli Technology. The camera (HBV-5640AF) was purchased from Shenzhen Huibo Shijie Technology. The shell of this device was 3D printed by Shenzhen Kuaima 3D Technology. The base and sample stage of this device were produced by Zhongshan Xiaoma Handboard Model Design. The open-source single-board computer (Orangepi PC Plus) was purchased from Shenzhen Xunlong Software. The filter holder was fabricated by 3D printing, and the apparatus (LG-192) was purchased from Guangzhou Lingjing Technology.

Preparation of the Protective crRNA.

All the sequences used are listed in SI Appendix, Table S3. Five microliters of 100 µM crRNA was annealed with various protective oligos by adding either 1× (5 µL 100 µM), 1.5× (7.5 µL 100 µM), or 2× (10 µL 100 µM) of protective oligo in the presence of 1× NEBuffer 2.1 containing 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris⋅HCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 100 µg/mL BSA (pH 7.9) and the volume was adjusted to 50 µL with RNase-free water. The mixture was heated to 70 °C in a heat block for 5 min and then transferred to room temperature for natural cooling. Finally, the annealed products (p-crRNA) were stored at −20 °C for further use.

Fluorescent LbCas12a Assay.

Annealing of the double-stranded DNA target.

All the sequences are listed in SI Appendix, Table S3. Five microliters of 100 μM target F was annealed with 5 μL 100 μM target R in the presence of 1× NEBuffer 2.1 and the volume was adjusted to 50 µL with RNase-free water. The mixture was heated to 70 °C in a heat block for 5 min and then transferred to room temperature for natural cooling. Finally, the annealed products (double-stranded DNA [dsDNA] target) were stored at −20 °C for further use.

CRISPR-Cas12a assay.

Briefly, a mixture with a final concentration of 50 nM LbCas12a, 10 nM crRNA, 50 nM FQ probe, and varied target DNA concentrations in 1× NEBuffer 2.1 was prepared and the volume was adjusted to 20 µL with RNase-free water. Then, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The fluorescence signals of the mixture were recorded every minute by a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III.

Photocontrolled CRISPR-Cas12a assay.

Briefly, a mixture with a final concentration of 50 nM LbCas12a, 10 nM p-crRNA, 50 nM FQ probe, and varied target DNA concentrations in 1× NEBuffer 2.1 was prepared and the volume was adjusted to 20 µL with RNase-free water. The mixture was then irradiated with a UV lamp (λ 365 nm, 35 W) for 30 s. Finally, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 1 h. The fluorescence signals were recorded every minute by a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III.

Detection of Plasmid DNA by qPCR.

The qPCR reaction of plasmid DNA was performed using TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus). A 10-μL qPCR reaction system contained 1× TB Green Premix Ex Taq II (Tli RNase H Plus), 500 nM forward and reverse primers, 2 μL plasmid DNA, and RNase-free water. The qPCR thermal cycling program was set as follows: 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of amplification reaction at 95 °C for 5 s and 59 °C for 30 s. Dissociation curves were carried out at the end of the qPCR procedure as follows: 95 °C for 15 s, 59 °C for 30 s, and 95 °C for 15 s. Fluorescence signals were recorded in each cycle by a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III.

Preparation of RNA Sequences for Specificity Evaluation.

RNA sequences derived from other related viruses used for measuring specificity were prepared by two different methods. The RNA sequences of pseudoviruses (hCoV-229E, RSV-A, RSV-B, IVB, MERS-CoV) were extracted using the MagZol Reagent Kit following the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA sequences of SARS-CoV and bat-SL-CoVZC45 were made in-house by in vitro transcription of DNA plasmids (shown in SI Appendix, Table S3). PCR was performed to amplify the genome fragments of SARS-CoV and bat-SL-CoVZC45 in the plasmid. A 50-μL PCR system contained 300 nM forward (containing T7 promoter sequences) and reverse primers, 25 μL TaKaRa Taq HS Perfect Mix, 2 μL plasmid template, and RNase-free water. Then, the PCR amplification products were used as a template for in vitro transcription at 37 °C for 4 h. A 50-μL in vitro transcription reaction system consisted of 2 mM NTP mixture, 50 U recombination RNase inhibitor, 250 U T7 RNA polymerase, and 2 μL DNA template. The RNA products were treated with recombinant DNase I and purified by an RNA Clean & Concentrator Kit for further use.

Collection and Extraction of Clinical Samples.

Nasopharyngeal and throat swab samples from suspected SARS-CoV-2 patients were collected by trained medical professionals in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China, during 2020. A QIAamp Viral RNA Mini Kit was used to extract SARS-CoV-2 RNA from these clinical samples in a biological safety protection third-level laboratory. After clinical nucleic acid detection, these samples were saved in the Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention for clinical study use. The use of clinical SARS-CoV-2 RNA samples for the current study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hubei Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention/Academy of Preventive Medicine (2020-061-01). To ensure the safety of patient privacy, waivers of the patients’ informed consent were approved by the ethics committee.

Detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA by qRT-PCR.

qRT-PCR amplification was performed by a CFDA-approved COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) Nucleic Acid Test Kit. For clinical sample detection, a 12.5-μL qRT-PCR reaction system contained 10 μL PCR solution and 2.5 μL clinical samples. The qRT-PCR thermal cycling program was set as follows: 50 °C for 15 min, 95 °C for 30 s, followed by 40 cycles of amplification reaction at 95 °C for 3 s, 60 °C for 40 s. Fluorescence signals were recorded in each cycle by a CFX96 Touch Deep Well Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). The criteria in this nucleic acid test kit are claimed as Ct value ≤38 is positive, 38< Ct value ≤40 is suspiciously positive, and Ct value >40 is negative.

Conventional One-Pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a Assay.

The DNA detection system was prepared separately as components A, B, and C. The detailed procedure is shown below. First, 29.5 µL primer-free rehydration buffer was added to one RPA pellet to make a suspended RPA mixture. Then, components A, B, and C were prepared. Five microliters of component A consists of 1 µL 10× NEBuffer 2.1, 1 µL 2 µM LbCas12a, 1 µL 2 µM crRNA, 1 µL 8 µM FQ probe, and 1 µL RNase-free water; 9.5 µL component B consists of 0.48 µL 10 µM forward primer, 0.48 µL 10 µM reverse primer, 5.9 µL suspended RPA mixture, 2 µL template DNA, and RNase-free water; component C contains 0.5 µL 280 mM magnesium acetate. Component B was first added to the bottom of the eppendorf (EP) tube. Components A and C were then added on the wall of the EP tube, respectively. After mixing components A, B, and C, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 90 min, and the fluorescence signal of the mixture was recorded with a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III.

The RNA detection system was the same as the above DNA detection system, except that 0.1 µL 200 U/µL SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase and 0.2 µL 5,000 U/mL RNase H were supplemented in component B.

Conventional Two-Step RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a Assay.

The DNA detection system was divided into two steps: RPA and CRISPR-Cas12a detection. The RPA procedure is shown below. First, 29.5 µL primer-free rehydration buffer was added to one RPA pellet to make a suspended RPA mixture. Then, a 9.5-µL amplification reaction mixture containing 0.48 µL 10 µM forward primer, 0.48 µL 10 µM reverse primer, 5.9 µL suspended RPA mixture, 2 µL template DNA, and RNase-free water was prepared and added to the bottom of the EP tube. Finally, 0.5 µL 280 mM magnesium acetate was added on the wall of the same EP tube. After centrifugation, the components were mixed and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Then, the LbCas12a detection was performed using the RPA product as the target. The 15-µL LbCas12a detection reaction mixture contains 1.5 µL 10× NEBuffer 2.1, 1 µL 2 µM LbCas12a, 1 µL 2 µM crRNA, 1 µL 8 µM FQ probe, 2 µL RPA products, and RNase-free water. The mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 60 min, and the fluorescence signal of the mixture was recorded with a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III.

The RNA detection system was the same as the above DNA detection system, except that 0.1 µL 200 U/µL SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase and 0.2 µL 5,000 U/mL RNase H were supplemented in the amplification reaction mixture.

Photocontrolled One-Pot RPA-CRISPR-Cas12a Assay.

The DNA detection system was prepared separately as components A, B, and C. The detailed procedure is shown below. First, 29.5 µL primer-free rehydration buffer was added to one RPA pellet to make a suspended RPA mixture. Then, preparation of components A, B, and C followed. Five microliters of component A consists of 1 µL 10× NEBuffer 2.1, 1 µL 2 µM LbCas12a, 1 µL 2 µM p-crRNA, 1 µL 8 µM FQ probe, and 1 µL RNase-free water; 9.5 µL component B consists of 0.48 µL 10 µM forward primer, 0.48 µL 10 µM reverse primer, 5.9 µL suspended RPA mixture, 2 µL template, and RNase-free water. Component C consists of 0.5 µL 280 mM magnesium acetate. Component B was first added to the bottom of the EP tube. Components A and C were then added on the wall of the EP tube, respectively. After mixing components A, B, and C, the mixture was transferred into the Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III for RPA at 37 °C for 30 min. Subsequently, the mixture was irradiated for 30 s with a UV lamp (λ 365 nm, 35 W). Then, the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for another 60 min, and the fluorescence signal of the mixture was recorded with a Thermal Cycler Dice Real-Time System III.

The RNA detection system was the same as the above DNA detection system, except that 0.1 µL 200 U/µL SuperScript IV reverse transcriptase and 0.2 µL 5,000 U/mL RNase H were supplemented in component B.

Fabrication of the Compact Photocontrolled CRISPR Detection Device.

A compact photocontrolled CRISPR detection device was designed using CATIA software. The size of the device is 126 × 126 × 120 mm. This device integrated three important functions: temperature control, photoexcitation, and fluorescence signal recording. Five main modules are contained in this device to achieve the above three functions, as follows. 1) A constant temperature control system. 2) Optical components; 480- and 365-nm LEDs, 480- and 520-nm band-pass filters, and dichroic mirrors are included. The 480-nm LED is used for fluorescence excitation, the 365-nm LED is used for PC-linker cleavage, the 480-nm band-pass filter is used for filtering stray light, the 520-nm band-pass filter is used for reducing the background, and the dichroic mirror is used for changing the excitation light path. 3) The camera module is used to collect the fluorescence. 4) An open-source single-board computer (Linux 5.4 System) is used to control the screen and camera for generating curves according to the collected pictures. 5) A control board, designed by Altium Designer software, is used to control the temperature and start the LED source.

To realize the intelligent operation of the device, an app was designed with Qt software. The app of the instrument has two main functions, as follows. 1) Fluorescence signal analysis. First, the images are captured by calling the Open CV library function at the speed of five frames per second and separating the green channel of each frame. Then, the color values of the green channel of all pixels are summarized. Finally, the average value of five frames is taken as the fluorescence intensity within 1 s. 2) Timing control. The serial port commands are used to control the timing sequence of each component. The workflow of the app is set as follows: Send a command to the control board > the microcontroller on the control board is started and the temperature is maintained at 37 °C > 480-nm LED is lit at the same time > 15 min later, the 365-nm LED is lit for 30 s > 14 min 30 s later, the heat-controlled system and LED light are switched off. The fluorescence signals are recorded throughout the detection process except for the UV irradiation procedures.

The detection procedure is automatic. The prepared reaction tube is put into the sample stage and the START button is clicked to start the whole program including the RPA (RT-RPA), UV irradiation, and fluorescence signal record. The detection results are reported within 30 min.

Code Availability.

The codes used for fluorescence signal analysis and timing control in the homemade device are available on Zenodo at https://zenodo.org/record/6620613#.Yp_3y6hBzIU (71).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32150019, 91959128, and 21874049), the Key Research and Development Plan of Hubei Province (2020BCA090), and the Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (2021A1515220164).

Footnotes

Competing interest statement: M.H. and X.Z. are named inventors of patent application no. 202210078298.2. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2202034119/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

The codes used in this article are available on Zenodo (71). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Mullis K., et al. , Specific enzymatic amplification of DNA in vitro: The polymerase chain reaction. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 51, 263–273 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y., Kang H., Liu X., Tong Z., Combination of RT-qPCR testing and clinical features for diagnosis of COVID-19 facilitates management of SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. J. Med. Virol. 92, 538–539 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Udugama B., et al. , Diagnosing COVID-19: The disease and tools for detection. ACS Nano 14, 3822–3835 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng W., et al. , Molecular diagnosis of COVID-19: Challenges and research needs. Anal. Chem. 92, 10196–10209 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weissleder R., Lee H., Ko J., Pittet M. J., COVID-19 diagnostics in context. Sci. Transl. Med. 12, eabc1931 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDermott A., Inner workings: Researchers race to develop in-home testing for COVID-19, a potential game changer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117, 25956–25959 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Notomi T., et al. , Loop-mediated isothermal amplification of DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 28, E63 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mori Y., Nagamine K., Tomita N., Notomi T., Detection of loop-mediated isothermal amplification reaction by turbidity derived from magnesium pyrophosphate formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 289, 150–154 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piepenburg O., Williams C. H., Stemple D. L., Armes N. A., DNA detection using recombination proteins. PLoS Biol. 4, e204 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walker G. T., Little M. C., Nadeau J. G., Shank D. D., Isothermal in vitro amplification of DNA by a restriction enzyme/DNA polymerase system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 392–396 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walker G. T., et al. , Strand displacement amplification—An isothermal, in vitro DNA amplification technique. Nucleic Acids Res. 20, 1691–1696 (1992). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An L., et al. , Characterization of a thermostable UvrD helicase and its participation in helicase-dependent amplification. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28952–28958 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vincent M., Xu Y., Kong H., Helicase-dependent isothermal DNA amplification. EMBO Rep. 5, 795–800 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Ness J., Van Ness L. K., Galas D. J., Isothermal reactions for the amplification of oligonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4504–4509 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaminski M. M., et al. , A CRISPR-based assay for the detection of opportunistic infections post-transplantation and for the monitoring of transplant rejection. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 601–609 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen J. S., et al. , CRISPR-Cas12a target binding unleashes indiscriminate single-stranded DNase activity. Science 360, 436–439 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang D., et al. , CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted multicolor biosensor for semiquantitative point-of-use testing of the nopaline synthase terminator in genetically modified crops by unaided eyes. ACS Synth. Biol. 9, 3114–3123 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gootenberg J. S., et al. , Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 356, 438–442 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gootenberg J. S., et al. , Multiplexed and portable nucleic acid detection platform with Cas13, Cas12a, and Csm6. Science 360, 439–444 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminski M. M., Abudayyeh O. O., Gootenberg J. S., Zhang F., Collins J. J., CRISPR-based diagnostics. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 5, 643–656 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joung J., et al. , Detection of SARS-CoV-2 with SHERLOCK one-pot testing. N. Engl. J. Med. 383, 1492–1494 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chertow D. S., Next-generation diagnostics with CRISPR. Science 360, 381–382 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Myhrvold C., et al. , Field-deployable viral diagnostics using CRISPR-Cas13. Science 360, 444–448 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Broughton J. P., et al. , CRISPR-Cas12-based detection of SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Biotechnol. 38, 870–874 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patchsung M., et al. , Clinical validation of a Cas13-based assay for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 RNA. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 1140–1149 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li S. Y., et al. , CRISPR-Cas12a-assisted nucleic acid detection. Cell Discov. 4, 20 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Y., Li S., Wang J., Liu G., CRISPR/Cas systems towards next-generation biosensing. Trends Biotechnol. 37, 730–743 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yue H., Huang M., Tian T., Xiong E., Zhou X., Advances in clustered, regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-based diagnostic assays assisted by micro/nanotechnologies. ACS Nano 15, 7848–7859 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li L., et al. , HOLMESv2: A CRISPR-Cas12b-assisted platform for nucleic acid detection and DNA methylation quantitation. ACS Synth. Biol. 8, 2228–2237 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zetsche B., et al. , Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell 163, 759–771 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Abudayyeh O. O., et al. , C2c2 is a single-component programmable RNA-guided RNA-targeting CRISPR effector. Science 353, aaf5573 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.East-Seletsky A., et al. , Two distinct RNase activities of CRISPR-C2c2 enable guide-RNA processing and RNA detection. Nature 538, 270–273 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li S. Y., et al. , CRISPR-Cas12a has both cis- and trans-cleavage activities on single-stranded DNA. Cell Res. 28, 491–493 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Swarts D. C., Jinek M., Mechanistic insights into the cis- and trans-acting DNase activities of Cas12a. Mol. Cell 73, 589–600.e4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shmakov S., et al. , Discovery and functional characterization of diverse class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. Mol. Cell 60, 385–397 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teng F., et al. , Repurposing CRISPR-Cas12b for mammalian genome engineering. Cell Discov. 4, 63 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strecker J., et al. , Engineering of CRISPR-Cas12b for human genome editing. Nat. Commun. 10, 212 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tian B., Minero G. A. S., Fock J., Dufva M., Hansen M. F., CRISPR-Cas12a based internal negative control for nonspecific products of exponential rolling circle amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, e30 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rolando J. C., Jue E., Barlow J. T., Ismagilov R. F., Real-time kinetics and high-resolution melt curves in single-molecule digital LAMP to differentiate and study specific and non-specific amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, e42 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pang B., et al. , Isothermal amplification and ambient visualization in a single tube for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 using loop-mediated amplification and CRISPR technology. Anal. Chem. 92, 16204–16212 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang R., et al. , opvCRISPR: One-pot visual RT-LAMP-CRISPR platform for SARS-Cov-2 detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 172, 112766 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yin K., et al. , Dynamic aqueous multiphase reaction system for one-pot CRISPR-Cas12a-based ultrasensitive and quantitative molecular diagnosis. Anal. Chem. 92, 8561–8568 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang B., et al. , Cas12aVDet: A CRISPR/Cas12a-based platform for rapid and visual nucleic acid detection. Anal. Chem. 91, 12156–12161 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen Y., et al. , Contamination-free visual detection of SARS-CoV-2 with CRISPR/Cas12a: A promising method in the point-of-care detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 169, 112642 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen Y., Mei Y., Zhao X., Jiang X., Reagents-loaded, automated assay that integrates recombinase-aided amplification and Cas12a nucleic acid detection for a point-of-care test. Anal. Chem. 92, 14846–14852 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ding X., et al. , Ultrasensitive and visual detection of SARS-CoV-2 using all-in-one dual CRISPR-Cas12a assay. Nat. Commun. 11, 4711 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gu C., et al. , Chemical synthesis of stimuli-responsive guide RNA for conditional control of CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 12, 9934–9945 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhang Y., et al. , Optical control of a CRISPR/Cas9 system for gene editing by using photolabile crRNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 20895–20899 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zou R. S., Liu Y., Wu B., Ha T., Cas9 deactivation with photocleavable guide RNAs. Mol. Cell 81, 1553–1565.e8 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou W., et al. , Spatiotemporal control of CRISPR/Cas9 function in cells and zebrafish using light-activated guide RNA. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 59, 8998–9003 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang Y., Liu Y., Xie F., Lin J., Xu L., Photocontrol of CRISPR/Cas9 function by site-specific chemical modification of guide RNA. Chem. Sci. (Camb.) 11, 11478–11484 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang S., et al. , Light-driven activation of RNA-guided nucleic acid cleavage. ACS Chem. Biol. 15, 1455–1463 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Moroz-Omori E. V., et al. , Photoswitchable gRNAs for spatiotemporally controlled CRISPR-Cas-based genomic regulation. ACS Cent. Sci. 6, 695–703 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jain P. K., et al. , Development of light-activated CRISPR using guide RNAs with photocleavable protectors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 12440–12444 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hemphill J., Borchardt E. K., Brown K., Asokan A., Deiters A., Optical control of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 5642–5645 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carlson-Stevermer J., et al. , CRISPRoff enables spatio-temporal control of CRISPR editing. Nat. Commun. 11, 5041 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Y., et al. , Very fast CRISPR on demand. Science 368, 1265–1269 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhou W., Deiters A., Conditional control of CRISPR/Cas9 function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 5394–5399 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nihongaki Y., Yamamoto S., Kawano F., Suzuki H., Sato M., CRISPR-Cas9-based photoactivatable transcription system. Chem. Biol. 22, 169–174 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nihongaki Y., et al. , CRISPR-Cas9-based photoactivatable transcription systems to induce neuronal differentiation. Nat. Methods 14, 963–966 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhou X. X., et al. , A single-chain photoswitchable CRISPR-Cas9 architecture for light-inducible gene editing and transcription. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 443–448 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hoffmann M. D., et al. , Optogenetic control of Neisseria meningitidis Cas9 genome editing using an engineered, light-switchable anti-CRISPR protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 49, e29 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nihongaki Y., Kawano F., Nakajima T., Sato M., Photoactivatable CRISPR-Cas9 for optogenetic genome editing. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 755–760 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Polstein L. R., Gersbach C. A., A light-inducible CRISPR-Cas9 system for control of endogenous gene activation. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 198–200 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Modell A. E., Siriwardena S. U., Shoba V. M., Li X., Choudhary A., Chemical and optical control of CRISPR-associated nucleases. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 60, 113–121 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X., et al. , A far-red light-inducible CRISPR-Cas12a platform for remote-controlled genome editing and gene activation. Sci. Adv. 7, eabh2358 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zetsche B., et al. , Multiplex gene editing by CRISPR-Cpf1 using a single crRNA array. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 31–34 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Li J., et al. , Discovery of the Rnase activity of CRISPR-Cas12a and its distinguishing cleavage efficiency on various substrates. Chem. Commun. (Camb.) 58, 2540–2543 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Qian J., et al. , An enhanced isothermal amplification assay for viral detection. Nat. Commun. 11, 5920 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nguyen L. T., Smith B. M., Jain P. K., Enhancement of trans-cleavage activity of Cas12a with engineered crRNA enables amplified nucleic acid detection. Nat. Commun. 11, 4906 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.M. Hu, et al., Photocontrolled crRNA activation enables robust CRISPR-Cas12a diagnostics-Source Code. Zenodo. https://zenodo.org/record/6620613#.Yp_3y6hBzIU. Deposited 7 June 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The codes used in this article are available on Zenodo (71). All other study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.