Abstract

Anaerobic degradation of 2-methylnaphthalene was investigated with a sulfate-reducing enrichment culture. Metabolite analyses revealed two groups of degradation products. The first group comprised two succinic acid adducts which were identified as naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid and naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid by comparison with chemically synthesized reference compounds. Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid accumulated to 0.5 μM in culture supernatants. Production of naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid was analyzed in enzyme assays with dense cell suspensions. The conversion of 2-methylnaphthalene to naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid was detected at a specific activity of 0.020 ± 0.003 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1 only in the presence of cells and fumarate. We conclude that under anaerobic conditions 2-methylnaphthalene is activated by fumarate addition to the methyl group, as is the case in anaerobic toluene degradation. The second group of metabolites comprised 2-naphthoic acid and reduced 2-naphthoic acid derivatives, including 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-naphthoic acid, octahydro-2-naphthoic acid, and decahydro-2-naphthoic acid. These compounds were also identified in an earlier study as products of anaerobic naphthalene degradation with the same enrichment culture. A pathway for anaerobic degradation of 2-methylnaphthalene analogous to that for anaerobic toluene degradation is proposed.

Aromatic hydrocarbons were considered to be recalcitrant in the environment under anoxic conditions until the first evidence of anaerobic BTEX degradation was reported in 1985 (17). Toluene turned out to be the most easily degradable aromatic hydrocarbon, and various pure bacterial strains have been isolated since then. Toluene can be degraded with nitrate, ferric iron, or sulfate as the electron acceptor, under fermentative conditions, and by phototrophic bacteria (7, 8, 20, 21, 25, 32). The pathway of toluene degradation has been investigated in detail for denitrifying bacteria of the genera Azoarcus and Thauera, and it was shown that the first degradation step is the addition of fumarate to the toluene methyl group (3, 4, 9, 13). The reaction is catalyzed by benzylsuccinate synthase, which belongs to the glycyl radical enzyme family. The benzylsuccinate synthase reaction appears to be representative of the degradation pathways of a number of environmental pollutants, such as m-xylene, o-xylene, and m-cresol, which all exhibit the addition of fumarate to the methyl group as the initial activation reaction (2, 16, 24). Further steps in anaerobic toluene degradation include a coenzyme A (CoA) transferase reaction of benzylsuccinate with succinyl-CoA, generating benzylsuccinyl-CoA and succinate (19). In the following reactions, benzylsuccinyl-CoA is probably oxidized through beta-oxidation to benzoyl-CoA, which enters the benzoyl-CoA degradation pathway.

Anaerobic degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons has been demonstrated in a few microcosm studies (5, 6, 18, 23, 27), and recently, naphthalene-degrading denitrifying and sulfate-reducing cultures were reported (1, 10, 22, 26, 33). In experiments with one marine and one freshwater culture, 2-naphthoic acid was the major metabolite of anaerobic naphthalene degradation and was generated by incorporation of bicarbonate into the carboxyl group (22, 33). The further degradation pathway might proceed via reduction of the aromatic ring system in analogy to the benzoyl-CoA degradation pathway, as reduced 2-naphthoic acid derivatives have been identified in culture supernatants (22).

Here we report on the anaerobic degradation of 2-methylnaphthalene by a sulfate-reducing enrichment culture from a freshwater sediment. Metabolites were extracted from culture supernatants and analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). The first enzyme reaction in the anaerobic 2-methylnaphthalene degradation pathway, catalyzed by naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate synthase, was identified in dense cell suspensions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation of bacteria.

A 2-methylnaphthalene-degrading, sulfate-reducing bacterial culture was enriched from a contaminated aquifer as described earlier (22). Subcultures were inoculated with 10% volume of the liquid phase in 100-ml serum bottles half filled with carbonate-buffered, sulfide-reduced freshwater medium, pH 7.4, with trace element solution SL10 (29, 30). Solid 2-methylnaphthalene crystals were added (2 to 4 mg/50 ml) together with 10 mM sulfate as the electron acceptor. The bottles were flushed with N2-CO2 (80/20), closed with Viton rubber stoppers (Maag Technik, Dübendorf, Switzerland), and incubated at 30°C in the dark.

Analysis of metabolites.

Sample preparation, gas chromatographic analysis, and GC-MS measurements were performed as described previously (22). Culture growth was stopped with 100 mM NaOH, and samples were stored at −20°C until metabolite analysis. Naphthalene was extracted with hexane from the alkaline sample. After acidification to pH 2.0 with 6 M hydrochloric acid, the water phase was extracted three times with dichloromethane to isolate carboxylic acids and aromatic alcohols. The combined dichloromethane extracts were concentrated by vacuum evaporation, dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate, and derivatized with ethereal diazomethane. The solvent was removed by a gentle stream of nitrogen, and products were transferred to hexane and analyzed by GC-MS.

GC-MS measurements were performed with a Hewlett Packard 6890 gas chromatograph coupled with a Quattro II mass spectrometer (Micromass, Attrincham, United Kingdom). The chromatograph was equipped with a 30-m capillary column (0.32-mm inside diameter, 0.25-μm film thickness; DB-5; J & W Scientific), and helium was used as the carrier gas. The temperature program was 80°C (5 min, isothermal), 80 to 310°C (4°C/min), and 310°C (10 min, isothermal).

The following MS conditions were applied: ionization mode, EI+; ionization energy, 70 eV; emission current, 200 μA; source temperature, 180°C; mass range, m/z 50-400.

For identification of metabolites, instrumental library searches applying the National Institute of Standards and Technology/National Institutes of Health/U.S. Environmental Protection Agency mass spectral database, comparison with published mass spectra, and coinjection with commercially available authentic reference compounds were carried out. Reference compounds for GC-MS analyses were obtained from Fluka (Buchs, Switzerland). Decahydro-2-naphthoic acid was synthesized by reduction of 2-naphthoic acid with hydrogen as described earlier (22).

Synthesis of naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid.

Synthesis of naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid (compound VI in Fig. 1 and 2) was performed according to references 11 and 28. Sodium metal (2.2 g of sodium, 96 mmol) was dissolved in absolute methanol (70 ml of methanol) at 0°C under nitrogen, followed by addition of diethylsuccinate (22.4 g, 128 mmol). Naphthalene-2-carbaldehyde (10 g, 64 mmol) (Fluka) was dissolved in absolute methanol (40 ml) and added dropwise within 40 min to the diethylsuccinate-methanol solution, which was heated under reflux cooling. After 2 h, NaOH (2 M, 160 ml) was added, and the mixture was heated for a further 6 h. The solution was concentrated by evaporation, HCl (37%, 40 ml) was added, and the aqueous phase was extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The combined organic layers were washed with saturated NaCl (twice, 50 ml each time), dried over MgSO4, and concentrated under vacuum. After the addition of hexane (30 ml) and benzene (30 ml), yellowish crystals precipitated. They were collected by filtration and recrystallized with 30 ml of ethanol (yield, 14.1 g [86%]; melting point, 188 to 189°C). The product was identified with 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (dimethyl sulfoxide [(NMR) DMSO]-d6): δ 3.5 (s, 2H), 7.5–7.6 (m, 2H), 7.9–8.0 (m, 6H), 12.6 (br s, 2H). NMR spectra were collected on a Bruker AC250 instrument (Bruker Analytik, Rheinstetten, Germany). Elemental analysis gave a C value of 69.9% and an H value of 4.7%. According to the formula C15H12O4, a C value of 70.3% and an H value of 4.7% were expected. GC-MS analysis revealed two peaks (relative amounts, 1:34) with identical mass spectra which are attributed to the E and Z isomers of naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid (Fig. 1).

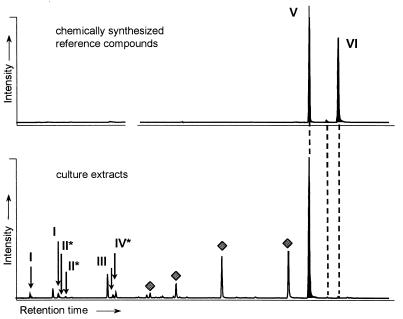

FIG. 1.

Partially reconstructed GC-MS total ion chromatograms. Top, chemically synthesized naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid (V) and naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid (VI) (as dimethyl esters). Bottom, methylated extracts from supernatants of cultures grown with 2-methylnaphthalene. I, isomers of decahydro-2-naphthoic acid; II, isomers of octahydro-2-naphthoic acid; III, 2-naphthoic acid; IV, 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-naphthoic acid.  , fatty acid methyl ester. Compounds marked with an asterisk are tentatively identified according to their mass spectra.

, fatty acid methyl ester. Compounds marked with an asterisk are tentatively identified according to their mass spectra.

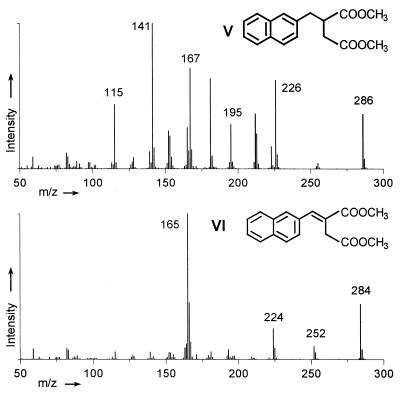

FIG. 2.

Mass spectra of the chemically synthesized reference compounds naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid (V) and naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid (VI) (as dimethyl esters).

Synthesis of naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid.

Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid (compound V in Fig. 1 and 2) was formed by catalytic reduction of naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid (7 g, 27.3 mmol) with palladium on activated carbon (0.7 g, 10% Pd) (Fluka), at a hydrogen pressure of 100 kPa for 40 h (11). The reaction mixture was filtered to remove the catalyst, and the filtrate was concentrated under vacuum. Addition of hexane (1 ml) resulted in precipitation of yellowish white crystals (6.3 g, 90%; melting point, 165 to 167°C). The product was identified with 1H NMR (DMSO-d6): δ 2.2–2.3 (m, 1H), 2.4–2.5 (m, 1H), 2.9–3.1 (m, 3H), 7.3–7.4 (m, 1H), 7.4–7.5 (m, 2H), 7.7 (s, 1H), 7.8–7.9 (m, 3H), 12.3 (s, 2H). Elemental analysis gave a C value of 69.3% and an H value of 5.6%. According to the formula C15H14O4, a C value of 69.8% and an H value of 5.4% were expected. GC-MS analysis revealed only one single peak (Fig. 1).

Enzyme tests.

Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate synthase was measured in dense cell suspensions which were prepared in the absence of dioxygen. Cells (150 ml) grown with 2-methylnaphthalene were collected by centrifugation under anoxic conditions (30 min, 16,000 × g) and resuspended in 1 ml of potassium phosphate buffer, 20 mM, pH 7.0, in a glove box. The buffer was reduced with 1 mM titanium(III) citrate (31). The cell suspension was injected into a 4-ml glass vial which was closed with a silicon rubber stopper and flushed with N2. 2-Methylnaphthalene (200 μM) was solubilized in the same titanium(III)-reduced potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, with or without 2 mM fumarate, and incubated for 2 days at 30°C in half-filled closed glass vials under N2 to achieve equilibrium between the water and gas phases. The 2-methylnaphthalene-containing buffer (1 ml) was added to the cell suspension, and 2 ml of the gas phase was withdrawn with a syringe and exchanged with 2 ml of the gas phase from the 2-methylnaphthalene-containing buffer vial. The reaction vial was incubated at 30°C in the dark. Samples of 150 μl were taken with a syringe through the stopper, and 100 μl was mixed with 400 μl of ethanol (99.8%) and subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis after removal of precipitates by centrifugation (5 min, 15,000 × g). Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid concentrations were determined by HPLC analysis on a Beckman System Gold equipped with a C18 reversed-phase column and UV detection at 206 nm. Eluent was isocratic acetonitrile–100 mM ammonium phosphate buffer, pH 3.5 (40/60).

RESULTS

Growth with 2-methylnaphthalene.

A sulfate-reducing culture that was enriched with naphthalene as the sole carbon and energy source was able to grow with crystalline 2-methylnaphthalene but not with 1-methylnaphthalene (22). The culture did not grow with 300 μM toluene as the sole carbon and energy source within 100 days of observation, either in the presence or in the absence of the solid adsorber resin Amberlite XAD7. XAD7 was used to provide the cells with toluene at a continuously low concentration, below toxic levels (30 to 50 μM). The identified metabolites naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid and naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid (see below) could also not be used as carbon sources at a concentration of 40 mg/liter.

Identification of metabolites.

GC-MS analysis of metabolites from supernatants of 2-methylnaphthalene-grown cultures revealed two groups of metabolites. The first group consisted of the major metabolite naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid and of naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid (Fig. 1). Both compounds were identified by GC coinjection and comparison of the mass spectra with chemically synthesized reference substances (Fig. 2). The chromatogram of chemically synthesized naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid revealed two separate peaks with identical mass spectra probably representing the E and Z isomers. Both peaks were identified in culture supernatants (Fig. 1). The absolute configuration of the compounds was not determined. Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid accumulated in culture supernatants up to 0.5 μM, as determined by HPLC.

The second group of metabolites was identified as 2-naphthoic acid and a series of reduced derivatives (Fig. 1) (for mass spectra see reference 22). 5,6,7,8-Tetrahydro-2-naphthoic acid and two isomers of octahydro-2-naphthoic acid were tentatively identified by their mass spectra. The most reduced metabolites were two decahydro-2-naphthoic acid isomers (decalin-2-carboxylic acid). The compounds were identified by their mass spectra and by coelution with the chemically synthesized reference compounds (22).

Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate synthase activity.

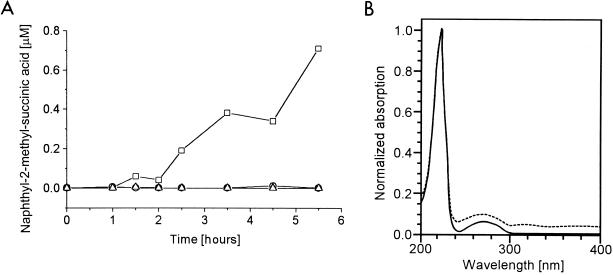

The first reaction step in anaerobic 2-methylnaphthalene degradation was analyzed in dense cell suspensions. In the presence of 2-methylnaphthalene and fumarate, a continuous production of naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate was observed (Fig. 3A). Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate was identified by HPLC with a diode array detector, by coelution with the chemically synthesized reference compound, and by its UV–visible-light absorption spectrum (Fig. 3B). Production of naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate was observed neither in the absence of cells nor in the absence of fumarate, indicating that fumarate is added to the methyl group of 2-methylnaphthalene as the first reaction step. The specific naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate synthase activity of three independent cell suspension experiments was 0.020 ± 0.003 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1. This represents 2.5% of the substrate turnover rate in the growing culture.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of the naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate synthase reaction in dense cell suspensions catalyzing the addition of fumarate to 2-methylnaphthalene. (A) Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid production in the presence of cells and 1 mM fumarate (□), with fumarate in the absence of cells (○), and in the presence of cells without fumarate (▵). (B) Absorption spectra of the naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid fraction eluting from the HPLC reversed-phase column at 7.8 min. Solid line, absorption spectrum of the chemically synthesized naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid; dashed line, absorption spectrum of the compound produced in dense cell suspensions.

DISCUSSION

In this study we report on the anaerobic degradation of 2-methylnaphthalene by a sulfate-reducing enrichment culture and the identification of the first enzyme in the pathway, naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate synthase.

The 2-methylnaphthalene-degrading culture was enriched with naphthalene as sole carbon and electron source and sulfate as the electron acceptor (22). Subsequent substrate utilization tests revealed that the culture could also utilize 2-methylnaphthalene as a growth substrate.

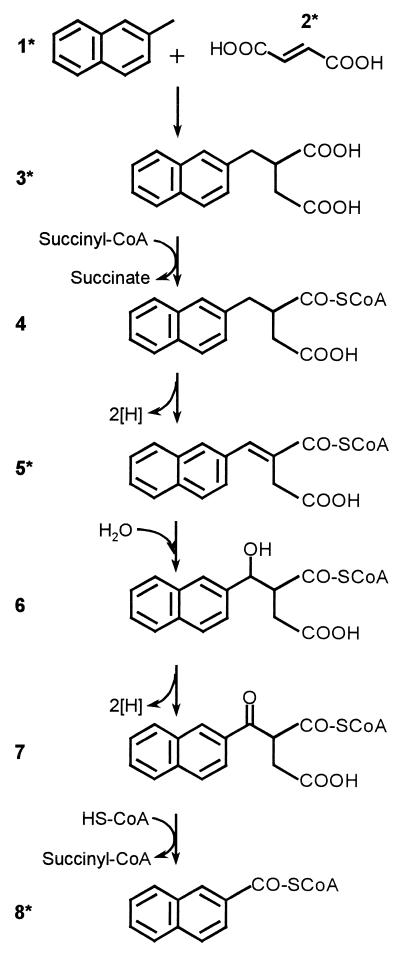

In culture supernatants two groups of metabolites could be identified by GC-MS analysis. The first series consisted of naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid and naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid. Both compounds are structural analogs of the first metabolites in anaerobic toluene degradation, benzylsuccinic acid and phenylitaconic acid (13). Thus, it is very likely that naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate is generated by the addition of fumarate to the methyl group of 2-methylnaphthalene, a mechanism similar to the benzylsuccinate synthase reaction. Indeed, a fumarate addition to the methyl group of 2-methylnaphthalene to yield naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid could be confirmed in cell suspension experiments. The reaction with 2-methylnaphthalene depended on the presence of cells and fumarate. In the presence of all reactants, the specific activity was 0.020 ± 0.003 nmol min−1 mg of protein−1. The naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate synthase activity in the enzyme test represented 2.5% of the substrate turnover rate in the growing culture, which is comparable to data for the similar enzyme benzylsuccinate synthase obtained by other authors (4). As the culture was not able to grow with toluene as the sole carbon and energy source the measured enzyme reaction is not only a side reaction of a toluene-degrading capacity of the culture but an activity specifically related to 2-methylnaphthalene degradation. The second identified metabolite was naphthyl-2-methylene-succinic acid, which is probably generated by beta-oxidation of naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid. A first step therein may be a CoA-dependent activation by a succinyl-CoA transferase. This type of reaction has been shown for anaerobic toluene degradation by the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica (19).

The second group of metabolites consisted of 2-naphthoic acid and reduced derivatives such as 5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-2-naphthoic acid, octahydro-2-naphthoic acid, and decahydro-2-naphthoic acid. These compounds were identified in an earlier study as metabolites of anaerobic naphthalene degradation by the same culture (22). In addition, some of these metabolites have been identified from a marine sulfate-reducing culture growing with naphthalene as the carbon source (33). As the two cultures were able to grow with 2-naphthoic acid as the sole source of carbon and energy, 2-naphthoic acid is likely to be a central intermediate in anaerobic degradation of naphthalene and 2-methylnaphthalene. The presence of the reduced derivatives indicates that the further degradation pathway of 2-naphthoic acid is probably initiated by ring reduction, in analogy to the anaerobic benzoyl-CoA pathway, perhaps after CoA-dependent activation (12, 14, 15). However, in the anaerobic benzoyl-CoA degradation pathway the aromatic ring is not completely reduced before water addition to initiate ring cleavage. Likewise, ring fission of the bicyclic system must not necessarily proceed via decahydro-2-naphthoic acid. The more reduced compounds may as well be dead-end metabolites. Nevertheless, the identification of common metabolites of both substrates suggests that anaerobic degradation of naphthalene and that of 2-methylnaphthalene share a common degradation pathway which is initiated by a reduction of the polycyclic aromatic ring system. At present, we do not know if ring cleavage is initiated from a monoaromatic ring system or if both rings are reduced before water addition.

Based on the present data, we propose an upper pathway for anaerobic degradation of 2-methylnaphthalene which is analogous to anaerobic degradation of toluene and other methylbenzenes (Fig. 4) (13, 19). In a first activation step, fumarate is added to the methyl group of 2-methylnaphthalene by naphthyl-2-methyl-succinate synthase, probably through a radical mechanism, in analogy to anaerobic toluene degradation. Naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid is likely to be activated by a succinyl-CoA-dependent CoA transferase and subsequent oxidation to yield naphthyl-2-methylene-succinyl-CoA. The following sequence of reactions proceeds via beta-oxidation and leads to the central intermediate 2-naphthoic acid CoA-ester.

FIG. 4.

Proposed scheme of the upper pathway of anaerobic 2-methylnaphthalene (1) degradation to the central intermediate 2-naphthoic acid (8). 2, fumaric acid; 3, naphthyl-2-methyl-succinic acid; 4, naphthyl-2-methyl-succinyl-CoA; 5, naphthyl-2-methylene-succinyl-CoA; 6, naphthyl-2-hydroxymethyl-succinyl CoA; 7, naphthyl-2-oxomethyl-succinyl-CoA. Compounds marked with an asterisk were identified in the present study as free acids.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Bernhard Schink for continuous support.

Financial support by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft for parts of this work is gratefully acknowledged (grants Mi 157/11-3 and Schi 180/7-3).

Footnotes

Publication 101 of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft priority program 546, Geochemical Processes with Long-Term Effects in Anthropogenically Affected Seepage and Groundwater.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bedessem M E, Swoboda-Colberg N G, Colberg P J S. Naphthalene mineralization coupled to sulfate-reduction in aquifer-derived enrichments. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152:213–218. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beller H R, Spormann A M. Anaerobic activation of toluene and o-xylene by addition to fumarate in denitrifying strain T. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:670–676. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.670-676.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beller H R, Spormann A M. Benzylsuccinate formation as a means of anaerobic toluene activation by the sulfate-reducing strain PRTOL1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3729–3731. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3729-3731.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biegert T, Fuchs G, Heider J. Evidence that anaerobic oxidation of toluene in the denitrifying bacterium Thauera aromatica is initiated by formation of benzylsuccinate from toluene and fumarate. Eur J Biochem. 1996;238:661–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1996.0661w.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coates J D, Anderson R T, Lovley D R. Oxidation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons under sulfate-reducing conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:1099–1101. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.1099-1101.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coates J D, Woodward J, Allen J, Philip P, Lovley D R. Anaerobic degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkanes in petroleum-contaminated marine harbor sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3589–3593. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3589-3593.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dolfing J, Zeyer J, Binder-Eicher P, Schwarzenbach R P. Isolation and characterization of a bacterium that mineralizes toluene in the absence of molecular oxygen. Arch Microbiol. 1990;154:336–341. doi: 10.1007/BF00276528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans P J, Mang D T, Kim K S, Young L Y. Anaerobic degradation of toluene by a denitrifying bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:1139–1145. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.4.1139-1145.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frazer A C, Ling W, Young L Y. Substrate induction and metabolite accumulation during anaerobic toluene utilization by the denitrifying strain T1. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:3157–3160. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.9.3157-3160.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galushko A, Minz D, Schink B, Widdel F. Anaerobic degradation of naphthalene by a pure culture of a novel type of marine sulphate-reducing bacterium. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:415–420. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harada H, Yamaguchi T, Iyobe A, Tsubaki A, Kamijo T, Jizuka K, Ogura K, Kiso Y. A practical synthesis of the ((2R)-3-(morpholinocarbonyl)-2-(1-naphtylmethyl)propionyl)-L-histidine moiety (P4-P2) in renin inhibitors. J Org Chem. 1990;55:1679–1682. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harwood C S, Burchardt G, Herrmann H, Fuchs G. Anaerobic metabolism of aromatic compounds via the benzoyl-CoA pathway. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;22:439–458. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heider J, Spormann A M, Beller H R, Widdel F. Anaerobic bacterial metabolism of hydrocarbons. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;22:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koch J, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Fuchs G. Products of enzymatic reduction of benzoyl-CoA, a key reaction in anaerobic aromatic metabolism. Eur J Biochem. 1993;211:649–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koch J, Fuchs G. Enzymatic reduction of benzoyl-CoA to alicyclic compounds, a key reaction in anaerobic aromatic metabolism. Eur J Biochem. 1992;205:195–202. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16768.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Krieger C J, Beller H R, Reinhard M, Spormann A M. Initial reactions in anaerobic oxidation of m-xylene by the denitrifying bacterium Azoarcus sp. strain T. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6403–6410. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6403-6410.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhn E P, Colberg P J, Schnoor J L, Wanner O, Zehnder A J B, Schwarzenbach R P. Microbial transformation of substituted benzenes during infiltration of river water to groundwater: laboratory column studies. Environ Sci Technol. 1985;19:961–968. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langenhoff A A M, Zehnder A J B, Schraa G. Behavior of toluene, benzene, and naphthalene under anaerobic conditions in sediment columns. Biodegradation. 1996;7:267–274. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leutwein C, Heider J. Anaerobic toluene-catabolic pathway in denitrifying Thauera aromatica: activation and β-oxidation of the first intermediate, (R)-(+)-benzylsuccinate. Microbiology. 1999;145:3265–3271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-11-3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lovley D R, Lonergan D J. Anaerobic oxidation of toluene, phenol, and p-cresol by the dissimilatory iron-reducing organism, GS-15. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1990;56:1858–1864. doi: 10.1128/aem.56.6.1858-1864.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meckenstock R U. Fermentative toluene degradation in anaerobic defined syntrophic cocultures. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;177:67–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13715.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meckenstock R U, Annweiler E, Michaelis W, Richnow H H, Schink B. Anaerobic naphthalene-degradation by a sulfate-reducing enrichment culture. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:2743–2747. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.7.2743-2747.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Milhelcic J R, Luthy R G. Degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon compounds under various redox conditions in soil-water systems. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1988;54:1182–1187. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.5.1182-1187.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Müller J A, Galushko A S, Kappler A, Schink B. Anaerobic degradation of m-cresol by Desulfobacterium cetonicum is initiated by formation of 3-hydroxybenzylsuccinate. Arch Microbiol. 1999;172:287–294. doi: 10.1007/s002030050782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rabus R, Nordhaus R, Ludwig W, Widdel F. Complete oxidation of toluene under strictly anoxic conditions by a new sulfate-reducing bacterium. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;59:1444–1451. doi: 10.1128/aem.59.5.1444-1451.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rockne K J, Chee-Sanford J C, Sanford R A, Hedlund B P, Staley J T, Strand S E. Anaerobic naphthalene degradation by microbial pure cultures under nitrate-reducing conditions. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1595–1601. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1595-1601.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rockne K J, Strand S E. Biodegradation of bicyclic and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in anaerobic enrichments. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:3962–3967. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stobbe H. Monoarylfulgensäuren und ihre Fulgide. Liebigs Ann Chem. 1911;380:26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Widdel F, Bak F. Gram-negative mesophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. Vol. 4. New York, N.Y: Springer Verlag; 1992. pp. 3352–3378. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Widdel F, Kohring G W, Mayer F. Studies on dissimilatory sulfate-reducing bacteria that decompose fatty acids. III. Characterization of the filamentous gliding Desulfonema limicola gen. nov., and Desulfonema magnum sp. nov. Arch Microbiol. 1983;134:286–294. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zehnder A J B, Wuhrmann K. Titanium (III) citrate as a nontoxic oxidation-reduction buffering system for the culture of obligate anaerobes. Science. 1976;194:1165–1166. doi: 10.1126/science.793008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zengler K, Heider J, Rosello-Mora R, Widdel F. Phototrophic utilization of toluene under anoxic conditions by a new strain of Blastochloris sulfoviridis. Arch Microbiol. 1999;172:204–212. doi: 10.1007/s002030050761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang X, Young L Y. Carboxylation as an initial reaction in the anaerobic metabolism of naphthalene and phenanthrene by sulfidogenic consortia. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:4759–4764. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.12.4759-4764.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]