Abstract

Objective To compare the effectiveness of the early accelerated rehabilitation and delayed conservative rehabilitation protocols after arthroscopic anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, in terms of the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score, pain (according to the Visual Analog Scale), laxity, and stiffness one year postoperatively to determine the best outcome.

Materials and Methods A total of 80 subjects were divided into 2e groups (early accelerated group and delayed conservative group), which were analyzed by the Pearson Chi-squared and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests.

Results One year postoperatively, knee laxity was significantly higher ( p = 0.039) in the early accelerated group compared with the delayed conservative group. Regarding postoperative pain (according to the Visual Analogue Scale) and IKDC scores, both groups presented similar results. The postoperative range of motion was better in the early accelerated group, but this was not statistically significant ( p = 0.36).

Conclusion One year postoperatively, the early accelerated rehabilitation protocol was associated with significant knee laxity compared to the delayed conservative rehabilitation protocol.

Keywords: anterior cruciate ligament injuries, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, rehabilitation

Introduction

Knee injuries are common musculoskeletal problems worldwide, with a prevalence as high as 35 cases for every 100 thousand patients. 1 In any case of trauma to a knee joint, the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is the most common ligament to be injured. 2 Around 200 thousand ACL reconstruction (ACL-R) surgeries are performed annually in the United States. 3 4 In India, ACL-R is usually performed using a hamstring tendon (semitendinosus and gracilis) or a bone-patellar tendon-bone (BPTB) autograft. The former is more commonly used than the BPTB autograft because of the ease of harvesting and lower donor-site morbidity. 5 In order to achieve a successful outcome, postoperative rehabilitation following ACL-R is an essential part of the management. 6 Different surgeons follow different protocols, and consensus is lacking. 7 But these protocols can broadly be divided into early accelerated rehabilitation (EAR) and delayed conservative rehabilitation (DCR). Studies in the Western literature suggest no functional differences between them, whereas other studies advocate for the DCR protocol. 8 9

The purpose of the present study was to compare the effectiveness of the EAR and DCR protocols in the achievement of optimal outcomes by patients undergoing ACL-R surgeries with an autologous hamstring graft in our tertiary health care hospital.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The present prospective, randomized, single-blinded study with two parallel arms was conducted at our tertiary care hospital from April 2019 to April 2020. The institutional ethical committee (T/IM-NF/T&EM/18/45) approved the study, which was registered in India's clinical trial registry (CTRI/2019/02/017726) before patient recruitment.

Study Population

We included adult patients aged between 18 and 60 years admitted for ACL-R. Those with meniscus injuries, multiligament injuries, or associated damages to the back, hip, or ankle joint, as well as bilateral limb injuries, were excluded. We also excluded patients in whom the surgeons failed to harvest a right hamstring graft (minimum width of 9 mm), or any other graft (peroneus, BPTB). Patients with radiological osteoarthritic changes were excluded as well.

Randomization and Allocation Concealment

After fulfilling the eligibility criteria, the patients included were randomized into two groups per computer-generated sequence using an online software randomizer. An independent coordinator (NS) concealed the allocation numbers in sealed envelopes. The baseline characteristics of the patients were taken after group allocation. The independent statistician (CRM) performing the analysis was blinded in the present study.

Sample Size

Based on a previous study by Christensen et al. 10 (2013), we calculated the sample size 39 patients in each group, assuming a significance level of 5% (alpha error) with a 90% probability of achieving statistical significance (power).

Surgical Technique

Two surgeons (SKP or BPP) operated on all included patients. After creating standard arthroscopic portals, an arthroscopic examination was performed in all cases to confirm the diagnosis. Double autologous semitendinosus and gracilis grafts were used in all cases. Depending on the diameter of the harvested graft, bone tunnels were prepared using standard jigs. The femoral side of the graft was fixed with the titanium Endobutton adjustable fixation device (Smith & Nephew, London United Kingdom) through the inside-out technique. A BioScrew (Linvatec Corp., Largo, FL, United States) measuring 1 mm more than the tunnel diameter was used as a fixation device on the tibial side. Any associated meniscal or chondral lesions were properly treated, but these cases were excluded from the study. After thorough lavage of the knee joint, the wound was closed, and an extended knee brace was applied. After the ACL-R, all patients were sent to rehabilitation as per the allocated group.

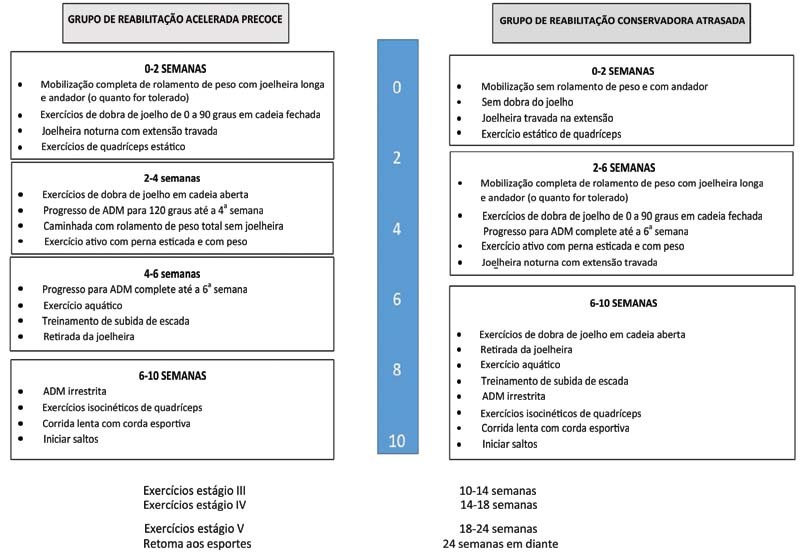

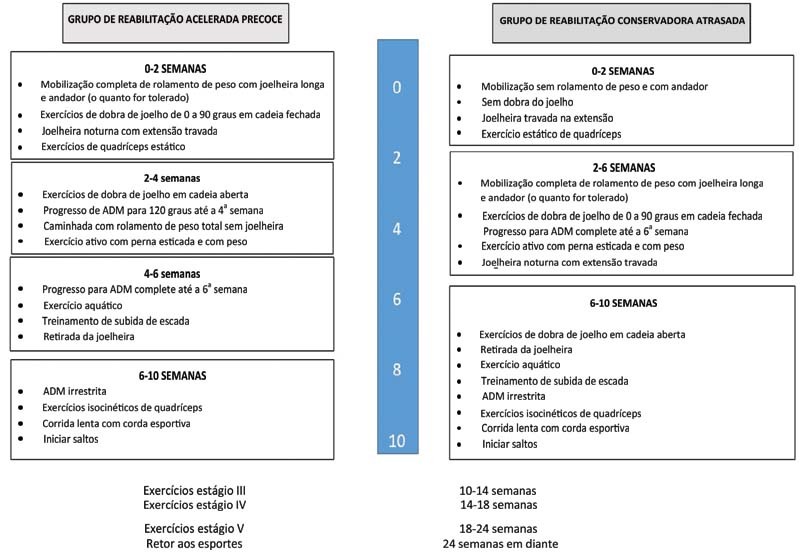

EAR group – The patients performed closed kinetic chain (CKC) range of motion (ROM) exercises, and were submitted to complete weight-bearing mobilization with the long-knee brace from postoperative day one as per tolerance, followed by open kinetic chain (OKC) ROM exercises and full weight-bearing walking without knee braces after two weeks. In two to ten weeks, the patients usually followed a home-based protocol ( Fig. 1 ). After ten weeks, both groups followed the same rehabilitation protocol.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the protocols followed by each study group.

DCR group— The patients kept the leg in an extended knee brace under non-weight-bearing mobilization for the first two weeks. This was followed by CKC ROM exercises and full weight-bearing with the long-knee brace for up to six weeks; OKC ROM exercises and full weight-bearing mobilization without knee braces were only started after six weeks. As per the home-based schedule ( Fig. 1 ), after ten weeks, both groups followed the same rehabilitation protocol, described as follows:

10 to 14 weeks: stage-III exercises

Forward and backward slow running;

Lunges and squats;

Slide board;

Ladder drills;

Aquatic program;

Progressive isokinetic quadriceps;

Progressive hamstring strengthening.

14 to 18 weeks: stage-IV exercises

Jogging;

Begin plyometric and strengthening program;

Kim-com test quadriceps.

18 to 24 weeks: stage-V exercises

Agility training;

Figure-of-eight jogging;

Sport-specific drills, such as figure of eight and carioca, under supervision of a physical therapist;

Continue total body fitness.

24 weeks onwards: return to sports.

Outcome Measures

All patients were followed up at two weeks, six weeks, six months, and one year. Stich removal was performed during the follow up at two weeks. In order to perform the statistical analysis, we measured the outcomes of the two groups during the follow-up visit after one year. The functional outcome was assessed through the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score and analyses of the ROM and laxity of the knee joint; the postoperative pain was assessed through the visual analog scale (VAS).

The IKDC score is obtained by adding the scores on individual items and converting the crude number to a scaled number ranging from 0 to 100. The final score is evaluated as a measure of the functional status, with higher scores representing a higher functional level. Scores < 2 on the VAS were graded as mild pain, from 2to 4, as moderate pain, and > 4, as severe pain. Laxity was measured using an arthrometer (KT1000, Medmetric Corp., San Diego, CA, United States); then, it was compared to that of the normal opposite knee. Anterior tibial translation from 0 to 2 mm is considered no laxity; from 3 mm to 5 mm, grade I; from 6 mm to 10 mm, grade II; and > 10 mm, grade-III laxity. Knee ROM was classified as follows: < 90° – low; between 90° and 120° – moderate; and > 120° –good.

Statistical Analysis

An independent statistician (CRM) performed the statistical analysis using the the R software (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria), version 3.6.1. The categorical variables were expressed as percentages, and the numerical variables (non-parametric), as medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs). The Chi-squared test was used for the bivariate analysis regarding the categorical variables, whereas the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (non-parametric) was used for the categorical and numeric variables.

Results

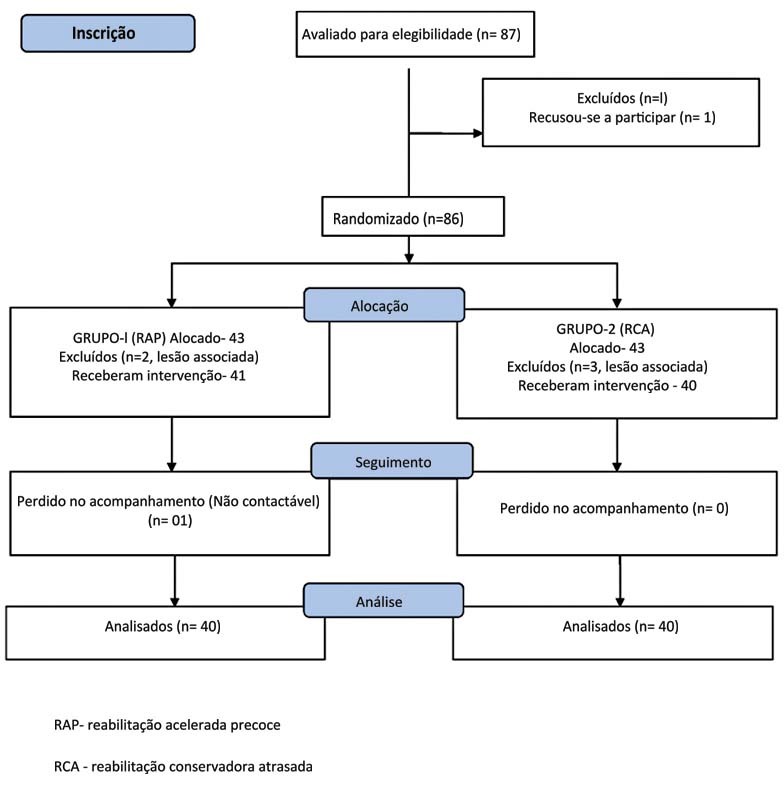

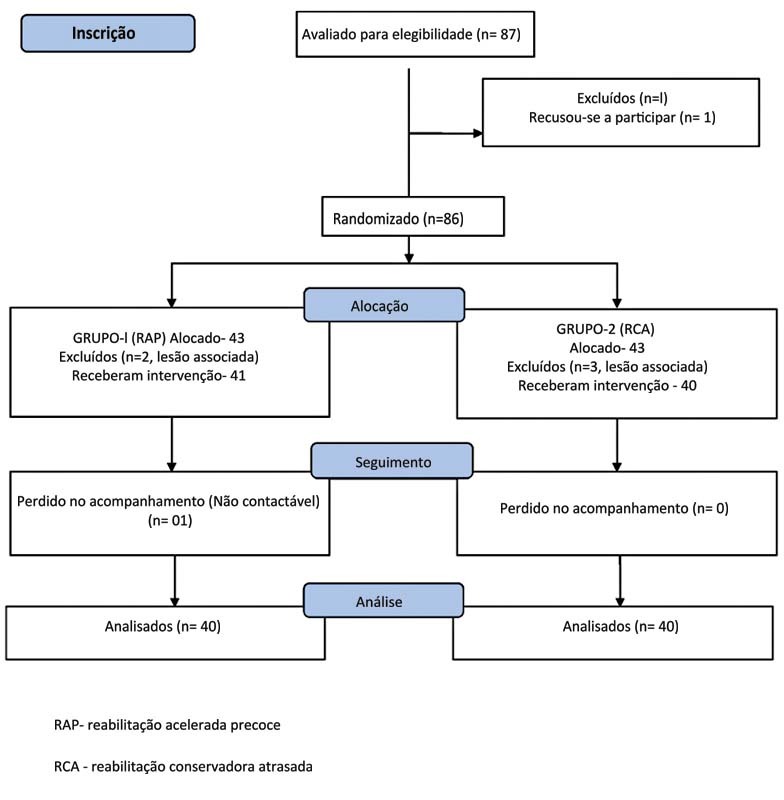

A total of 87 subjects were selected, but 1 patient did not provide consent and was excluded. The remaining 86 patients were divided into 2 groups (of 43 patients each). One patient in the EAR group was lost to follow-up, and two patients had associated meniscus tears; they were excluded. Three patients in the DCR group had associated meniscus tears and were also excluded. Thus, 80 patients (40 patients in each group) were analyzed, as shown in Figure 2 .

Fig. 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram showing randomization and group allocation.

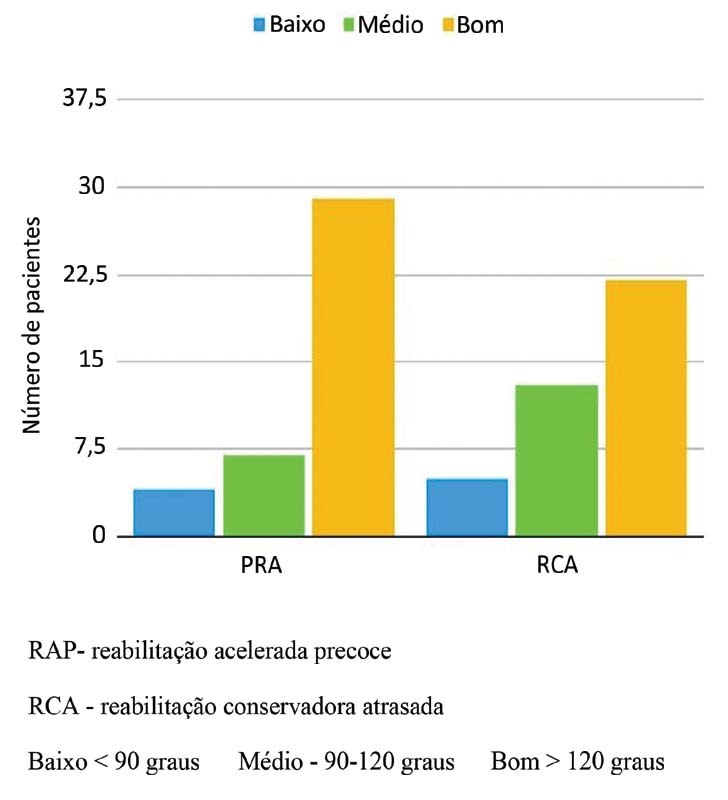

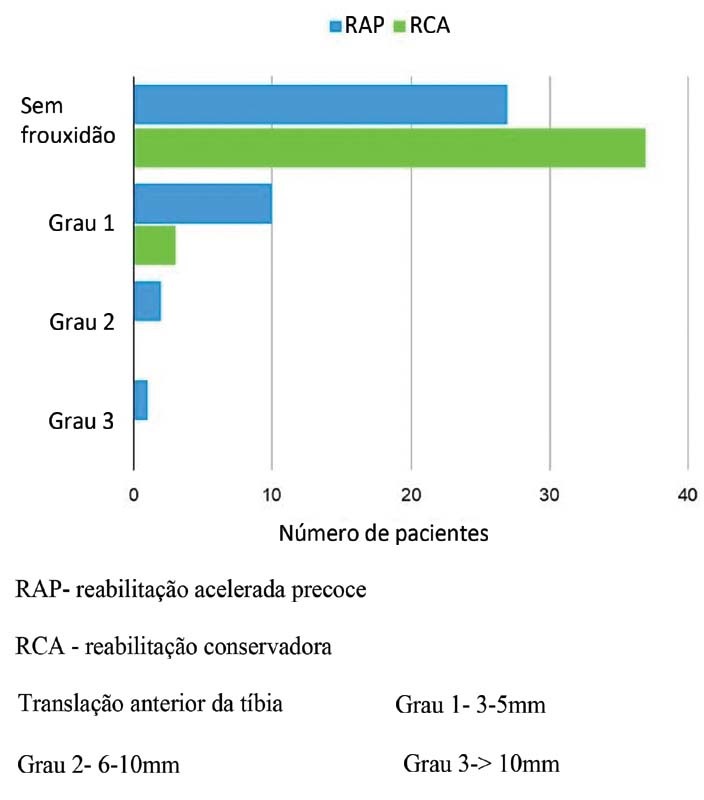

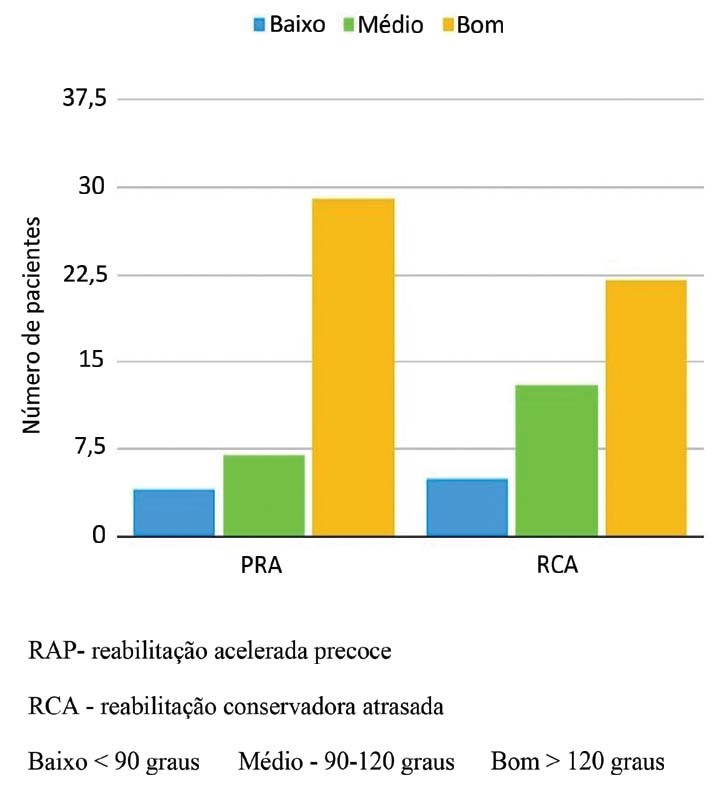

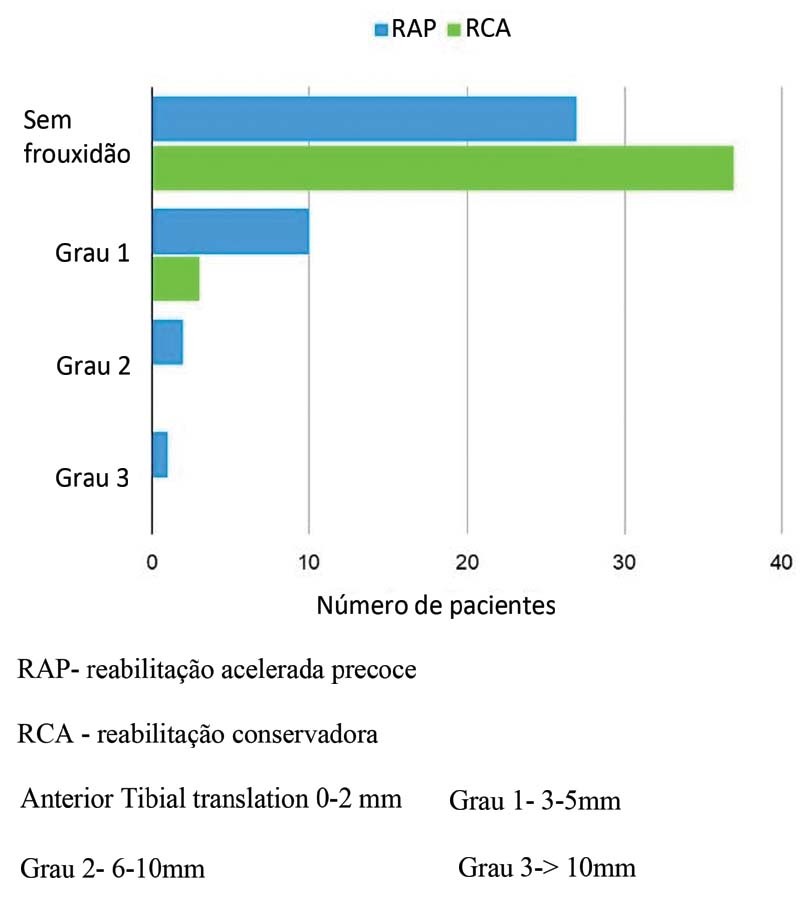

The baseline characteristics of the sample were comparable, as depicted in Tables 1 and 2 . We observed a remarkable improvement in the IKDC score compared to the preoperative values in both groups. During the follow-up after one year, the ROM and the VAS and IKDC scores in both groups were comparable, but this was not statistically significant, as seen in Figure 3 and Table 3 ( p = 0.36, 0.51, and 0.91 respectively). The one-year postoperative laxity was higher in the EAR group in comparison to the DCR group ( p = 0.039; Table 3 and Fig. 4 ).

Table 1. Demographics of the study groups.

| Variables | Early rehabilitation (n = 40) |

Delayed rehabilitation (n = 40) |

p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years: median (IQR) [range] |

34 (28–39) [18–60] | 33 (26–38) [18–60] | 0.66 |

| Male gender: mean (%) | 37 (92.5%) | 36 (90%) | 0.99 |

| Height in cm: median (IQR) [range] |

165.3 (159.1–172) [152–179.2] | 164.8 (158.4–171.8) [151.9–179] | 0.57 |

| Weight in kg: median (IQR) [range] |

65 (58–70) [54.4–82] | 65.6 (60.1–72.2) [53.4–82.6] | 0.76 |

|

BMI in kg/m

2

:

median (IQR) [range] |

24 (22–27) [16–38] | 26 (22.6–27.4) [15.8–29] | 0.43 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2. Preoperative (baseline) characteristics of the study groups.

| Variables | Early rehabilitation (n = 40) |

Delayed rehabilitation (n = 40) |

p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IKDC score: median (IQR) | 49 (45–52.1) | 48.2 (44.8–52.1) | 0.75 |

| Visual Analog Scale score: mean (%) | 0.78 | ||

| Mild | 34 (85%) | 32 (80%) | |

| Moderate | 6 (15%) | 8 (20%) | |

| Severe | 0 | 0 | |

| Range of motion: mean (%) | 0.216 | ||

| < 90° (low) | 0 | 0 | |

| 90°–120° (medium) | 8 (20%) | 15 (37.5%) | |

| > 120° (good) | 32 (80%) | 25 (62.5%) |

Abbreviation: IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee; IQR, interquartile range.

Fig. 3.

Bar diagram showing the postoperative range of motion of the study groups.

Table 3. Postoperative (follow up after one year) characteristics of the study groups.

| Variables | Early rehabilitation (n = 40) |

Delayed rehabilitation (n = 40) |

p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| IKDC score: median (interquartile range) | 89.5 (85.2–92.1) | 89.6 (85.4–92.5) | 0.91 |

| Visual Analog Scale score: mean (%) | 0.51 | ||

| Mild | 38 (95%) | 38 (95%) | |

| Moderate | 1 (2.5%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Severe | 1 (2.5%) | 0 | |

| Range of motion: mean (%) | 0.36 | ||

| < 90° (low) | 4 (10%) | 5 (12.5%) | |

| 90°–120° (medium) | 7 (17.5%) | 13 (32.5%) | |

| > 120° (good) | 29 (72.5%) | 22 (55%) | |

| Laxity score: mean (%) | 0.039* | ||

| No laxity | 27 (67.5%) | 37 (92.5%) | |

| Grade 1 | 10 (25%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Grade 2 | 2 (5%) | 0 | |

| Grade 3 | 1 (2.5%) | 0 |

Abbreviation: IKDC, International Knee Documentation Committee.

Note: *Statistically significant.

Fig. 4.

Bar diagram showing the postoperative laxity of the study groups.

There were three cases of superficial wound infection in our series, one in the EAR group and two in the DCR group. All responded to debridement and serial dressing. There were no cases of deep infection.

Discussion

In the follow-up visit after one year, the knee laxity was significantly higher in the EAR group compared to the DCR group, even as the pain, ROM and functional outcomes remained the same.

Christensen et al. 10 did not find any differences in the subjective IKDC score, knee laxity and ROM between their two study groups. The essential goal of the rehabilitation program following ACL-R should be to restore the full knee ROM. 11 Although there are enough studies in the literature to enable the conclusion that early recovery of the ROM is required to achieve better outcomes following ACL-R, it is still inconclusive whether an accelerated rehabilitation protocol helps achieve this more rapidly. 12 However, the present study demonstrates a higher potential risk of residual laxity with the EAR protocol. Some authors 13 14 have mentioned an increase in the diameter of the bone tunnel after the EAR protocol with semitendinous grafts, but without any conclusive evidence on the anteroposterior and subjective outcomes.

Similarly, Beynnon et al. 15 concluded that there were no significant differences regarding both protocols in terms of muscle strength and knee laxity. In contrast, we recorded substantial anteroposterior laxity during the follow-up after one year in the EAR group. Osteointegration initially occurs with fibrovascular interface tissue between bone and tendon and, subsequently, bony ingrowth takes around three to six weeks. 16 This could be affected by OKC exercises if they start early. Moreover, activities like squatting and cross-leg sitting may strain the newly-reconstructed ACL. Escamilla et al. 17 found that, in early squatting between 0° and 60°, the shear forces were low and primarily restricted by the ACL. With near-maximum knee flexion, the shear forces also peak, putting a lot of stress on the new ACL. 17

Andersson et al. 18 performed a systematic review of four randomized studies. They found that in ACL-R with BPTB graft, early CKC exercises generate lower levels of pain, lower risk of increased laxity, and better self-reported knee function than OKC quadriceps exercises. In contrast, a recent study 19 found no difference between the groups. Glass et al. 20 also advised against using OKC exercises within the first six weeks. All these studies involved BPTB grafts. Heijne et al. 21 compared BPTB and hamstring grafts in early (4 weeks) and late (12 weeks) OKC exercises and found that laxity was higher in the hamstring group. In the present study, patients in the DCR group performed delayed (after six weeks) OKC exercises, and fared better in terms of laxity. Van Grinsven et al. 22 performed a systemic review and found that an accelerated protocol without postoperative bracing does not lead to stability problems, and offers the advantage of reduction in pain, swelling, and inflammation, as well as ROM recovery. Morrissey et al. 23 did not observe differences in the VAS pain scores of the OKC and CKC groups. In the present study, the VAS scores were lower in the EAR group, which performed CKC exercises, both three and six months postoperatively. Kruse et al. 24 have stated that further investigations are warranted in order to draw conclusions regarding the rehabilitation protocol.

Tyler et al. 25 compared immediate weight-bearing as tolerated versus a delay of two weeks; they found a statistically significant difference in anterior knee pain in the delayed group, and concluded that early weight-bearing did not cause harmful effects on stability or function. Schenck et al. 26 compared clinic-based and home-based rehabilitation protocols and found that minimal supervision during rehabilitation could result in equivalent outcomes following ACL-R. We distributed printouts explaining the exercises to our patients, who were free to inquire about any difficulties on any day outside the follow-up visits.

In the present study, the median IKDC score (of 89.5) was similar in both groups one year postoperatively, which is in line with the study by Grindem et al., 27 who found a score of 89/100 score two years postoperatively. However, Hopper et al. 28 found that knee scores continue to improve up to six years after surgery and only attain approximately 86% of their value after one year.

The strength of the present study is that it is the first of its kind conducted in the Indian population. The limitation was the short follow-up, of only one year. Hence, a larger, multicentric, and longer study in the same population may help to validate our findings.

Conclusion

The EAR protocol yields similar ROM, IKDC scores, and postoperative pain relief compared to the DCR protocol. However, at the one-year follow-up visit, we observed significantly higher knee laxity in the EAR group.

Funding Statement

Suporte Financeiro Os autores declaram que não receberam apoio financeiro de fontes públicas, comerciais ou sem fins lucrativos para a realização do presente estudo.

Financial Support The authors declare that thy have not received any financial support from public, commercial, or non-profit sources to conduct the present study.

Conflito de Interesses Os autores declaram não haver conflito de interesses.

Trabalho desenvolvido no Departamento de Trauma e Emergência, AIIMS, Bhubaneswar, Índia.

Work developed at the Department of Trauma and Emergency, AIIMS, Bhubaneswar, India.

Referências

- 1.Muller B, Hofbauer M, Wongcharoenwatana J, Fu F H. Indications and contraindications for double-bundle ACL reconstruction. Int Orthop. 2013;37(02):239–246. doi: 10.1007/s00264-012-1683-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arliani G G, Pereira V L, Leão R G, Lara P S, Ejnisman B, Cohen M. Treatment of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries in Professional Soccer Players by Orthopedic Surgeons. Rev Bras Ortop (Sao Paulo) 2019;54(06):703–708. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1697017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barber-Westin S D, Noyes F R. Factors used to determine return to unrestricted sports activities after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2011;27(12):1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arliani G G, Astur DdaC, Kanas M, Kaleka C C, Cohen M. Anterior cruciate ligament injury: treatment and rehabilitation. current perspectives and trends. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;47(02):191–196. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevanović V, Blagojević Z, Petković A. Semitendinosus tendon regeneration after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: can we use it twice? Int Orthop. 2013;37(12):2475–2481. doi: 10.1007/s00264-013-2034-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beynnon B D, Uh B S, Johnson R J. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind comparison of programs administered over 2 different time intervals. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33(03):347–359. doi: 10.1177/0363546504268406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reinhardt K R, Hetsroni I, Marx R G. Graft selection for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a level I systematic review comparing failure rates and functional outcomes. Orthop Clin North Am. 2010;41(02):249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2009.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holm I, Øiestad B E, Risberg M A, Aune A K. No difference in knee function or prevalence of osteoarthritis after reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament with 4-strand hamstring autograft versus patellar tendon-bone autograft: a randomized study with 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(03):448–454. doi: 10.1177/0363546509350301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bynum E B, Barrack R L, Alexander A H. Open versus closed chain kinetic exercises after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. A prospective randomized study. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23(04):401–406. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Christensen J C, Goldfine L R, West H S. The effects of early aggressive rehabilitation on outcomes after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction using autologous hamstring tendon: a randomized clinical trial. J Sport Rehabil. 2013;22(03):191–201. doi: 10.1123/jsr.22.3.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biggs A, Jenkins W L, Urch S E, Shelbourne K D. Rehabilitation for Patients Following ACL Reconstruction: A Knee Symmetry Model. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2009;4(01):2–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saka T. Principles of postoperative anterior cruciate ligament rehabilitation. World J Orthop. 2014;5(04):450–459. doi: 10.5312/wjo.v5.i4.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vadalà A, Iorio R, De Carli A. The effect of accelerated, brace free, rehabilitation on bone tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction using hamstring tendons: a CT study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(04):365–371. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0219-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iorio R, Vadalà A, Argento G, Di Sanzo V, Ferretti A. Bone tunnel enlargement after ACL reconstruction using autologous hamstring tendons: a CT study. Int Orthop. 2007;31(01):49–55. doi: 10.1007/s00264-006-0118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beynnon B D, Johnson R J, Naud S. Accelerated versus nonaccelerated rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a prospective, randomized, double-blind investigation evaluating knee joint laxity using roentgen stereophotogrammetric analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(12):2536–2548. doi: 10.1177/0363546511422349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen C H. Graft healing in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol. 2009;1(01):21. doi: 10.1186/1758-2555-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escamilla R F, Fleisig G S, Zheng N. Effects of technique variations on knee biomechanics during the squat and leg press. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33(09):1552–1566. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200109000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersson D, Samuelsson K, Karlsson J. Treatment of anterior cruciate ligament injuries with special reference to surgical technique and rehabilitation: an assessment of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(06):653–685. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2009.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdalla R J, Monteiro D A, Dias L, Correia D M, Cohen M, Forgas A. Comparison between the results achieved in anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with two kinds of autologous grafts: patellar tendon versus semitendinous and gracilis. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;44(03):204–207. doi: 10.1016/S2255-4971(15)30069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glass R, Waddell J, Hoogenboom B. The Effects of Open versus Closed Kinetic Chain Exercises on Patients with ACL Deficient or Reconstructed Knees: A Systematic Review. N Am J Sports Phys Ther. 2010;5(02):74–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heijne A, Werner S. Early versus late start of open kinetic chain quadriceps exercises after ACL reconstruction with patellar tendon or hamstring grafts: a prospective randomized outcome study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2007;15(04):402–414. doi: 10.1007/s00167-006-0246-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Grinsven S, van Cingel R E, Holla C J, van Loon C J. Evidence-based rehabilitation following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2010;18(08):1128–1144. doi: 10.1007/s00167-009-1027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrissey M C, Hudson Z L, Drechsler W I, Coutts F J, Knight P R, King J B. Effects of open versus closed kinetic chain training on knee laxity in the early period after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(06):343–348. doi: 10.1007/s001670000161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kruse L M, Gray B, Wright R W. Rehabilitation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(19):1737–1748. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tyler T F, McHugh M P, Gleim G W, Nicholas S J. The effect of immediate weightbearing after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(357):141–148. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schenck R C, Jr, Blaschak M J, Lance E D, Turturro T C, Holmes C F. A prospective outcome study of rehabilitation programs and anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(03):285–290. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(97)90022-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grindem H, Wellsandt E, Failla M, Snyder-Mackler L, Risberg M A. Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury-Who Succeeds Without Reconstructive Surgery? The Delaware-Oslo ACL Cohort Study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(05):2.325967118774255E15. doi: 10.1177/2325967118774255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hooper D M, Morrissey M C, Drechsler W, Morrissey D, King J. Open and closed kinetic chain exercises in the early period after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Improvements in level walking, stair ascent, and stair descent. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(02):167–174. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]