Abstract

Introduction

Dyspnoea is common in patients with giant paraoesophageal hernia (PEH). Pulmonary aspiration has not previously been recognised as a significant contributory factor. Aspiration pneumonia in association with both gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) and PEH has a high mortality rate. There is debate about routine anti-reflux measures with surgical repair. Reflux aspiration has been examined in a consecutive cohort using scintigraphic scanning and symptoms.

Methods

Reflux aspiration scintigraphy (RASP) results and symptoms were evaluated in consecutive patients with PEH managed in our service between January 2012 and March 2017.

Results

PEH was diagnosed in 96 patients. Preoperative reflux pulmonary scanning was performed in 70 patients: 54 were female (77.1%) and the mean age was 68 years (range 49–85). Dyspnoea was the most common symptom (77.1%), and a symptomatic history of aspiration was seen in 18 patients (25.7%). Clinical aspiration was confirmed by RASP in 13 of these cases. Silent RASP aspiration occurred in a further 27 patients without clinical symptoms. RASP was negative in five patients with clinical symptoms of aspiration. No aspiration by either criterion was present in 27 patients. Dysphagia was negatively related to aspiration on RASP (p<0.01), whereas dyspnoea was not (p=0.857).

Conclusion

GORD, dyspnoea and silent pulmonary aspiration are frequent occurrences in the presence of giant PEH. Subjective aspiration was the most specific and positive predictor of pulmonary aspiration. Dyspnoea in PEH patients may be caused by pulmonary aspiration, cardiac compression and gas trapping. The high rate of pulmonary aspiration in PEH patients may support anti-reflux repair.

Keywords: Giant hiatus hernia, Paraoesophageal hiatus hernia, Gastro-oesophageal reflux, Pulmonary aspiration, Dyspnoea

Introduction

Hiatal hernia (HH) is defined as herniation of the stomach and the gastroesophageal junction above the diaphragm through the oesophageal hiatus, and is further classified into four types (Table 1).1 Giant hiatus hernias have been defined as paraoesophageal hernias (PEHs) with more than 30% of the stomach present in the chest. Mortality from life-threatening complications such as gastric volvulus and aspiration has been reported to reach 16% at 4 years.1 As the PEH component becomes larger, it can inhibit heartburn by oesophageal kinking or compression (Figure 1), congruent with the lesser clinical experience of heartburn in this patient group. Pulmonary aspiration of refluxate is likely to be the cause of dyspnoea in these patients, and has been implicated in pulmonary diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), pneumonia and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).2–4 Reflux aspiration pneumonia has been found to have a 23% mortality rate.5 Noth et al found that IPF was more prevalent in patients with HH compared with either COPD or asthma.6

Table 1 .

Definition of hiatus hernia

| Type | Definition | N=70 |

|---|---|---|

| 1 Sliding | Gastroesophageal junction is above the diaphragm | – |

| 2 Paraoesophageal | Gastric fundus herniates through the diaphragmatic hiatus | – |

| 3 Mixed paraoesophageal | Combination of type 1 and type 2 | 55 |

| 4 Paraoesophageal giant hiatus hernia | Large paraoesophageal hernia with other organ within hernia sac (ie omentum, colon) | 15 |

Figure 1 .

Barium meal. Paraoesophageal hiatus hernia showing oesophageal kinking (white arrow) and oesophageal compression (black arrow)

The rate of aspiration in patients with PEH remains unknown; however, a high rate of dyspnoea has recently been recognised. PEH may present with symptoms of heartburn and regurgitation similar to gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD),7 which has a high prevalence of 25%.8 The Montreal classification is the international standard for defining GORD and incorporates patient symptomatology independent of endoscopic findings.9 When the gastric contents contaminate the proximal oesophagus, atypical symptoms of cough, wheeze or throat-clearing may emerge and can cause recurrent pulmonary infection and aspiration pneumonia.10 Pulmonary symptoms and disease are therefore a recognised clinical picture in reflux disease and HH.

Although lesser degrees of GORD may be caused by transient lower oesophageal sphincter relaxation, the more substantial problem arises from derangement of the native anti-reflux mechanism, such as in PEH or HH. This may lead to increased frequency and volume of reflux, ‘flooding’ of the oesophagus and subsequent proximal reflux events and pulmonary complications.11

The clinical diagnosis of pulmonary reflux aspiration can be supported by biomarker tests such as pepsin and bile salt in bronchoscopic alveolar lavage, or suggested by oesophageal impedance testing or pharyngeal pH measures of acidity (Restech).12 However, the standard distal oesophageal 24-h pH study was found to have poor sensitivity of 24% and specificity of 65% in detecting the likelihood of aspiration when compared with direct identification of aspiration events by pulmonary scintigraphy.13 Similarly, impedance reflux studies indirectly assess the potential risk of pulmonary contamination by identification of proximal oesophageal reflux episodes. Indirect tests such as chest X-ray, pulmonary computed tomography scanning and bronchoscopy may show changes that infer reflux-related pulmonary events.2

Conventionally, pulmonary aspiration is diagnosed by likelihood rather than certainty. The refinement of a validated and controlled scintigraphic scan has now made the identification of reflux-aspiration events more certain because the isotope can be identified in the lung with as little as 0.1MBq in the refluxate. This does not occur in a normal control group.14,15

Surgical repair of PEH involves dissection of the hernia sac and anterior/posterior cruroplasty to restore the tension-free intra-abdominal position of the stomach and distal oesophagus. Anti-reflux surgery (fundoplication) creates a flap valve to restore an anti-reflux barrier of the cardio-oesophageal junction in the correct intra-abdominal anatomical position, to reduce GORD.16 There is substantial debate in surgical circles regarding the utility of routine anti-reflux surgery during repair of symptomatic PEH. There is only one randomised controlled trial that compared simple repair and repair with fundoplication; this study showed a quality-of-life benefit with fundoplication.16 Reflux symptomatology is seen in half of patients reported in a series of PEH7 and the prospect of dyspnoea being related to pulmonary contamination would present a further reason for routine anti-reflux surgery during PEH repair. The possibility of pulmonary symptoms being secondary to reflux pulmonary aspiration in patients with giant hiatus hernia warrants evaluation of pulmonary aspiration.

Methods

A cohort of consecutive patients from a database collected prospectively between 1 January 2012 and 31 March 2017 was utilised. Patient inclusion criteria were: diagnosis of large PEH (type 3–4 HH containing >30% stomach), prospectively completed patient reflux symptom sheet and completion of preoperative reflux aspiration scintigraphy (RASP). The results of patients without RASP were not included in the study. The results of echocardiograms undertaken at the time of patient referral were examined retrospectively. All other data were stored prospectively in a password-protected computer database, approved by Concord Hospital institutional ethics committee (CH62/6/2011-092).

The reflux symptom sheet proforma was populated at the initial visit and missing data (symptoms) were sought from consultant letters. Typical and atypical reflux symptoms, and entrapment symptoms were recorded. Symptoms were not self-reported but assessed by the operating surgeon based on the proforma. Clinical aspiration was defined as presence of vomitus inhalation from reflux or regurgitation.

Considering the scintigraphic result (RASP) to be the reference, patients were categorised as described in Table 2.

Table 2 .

Clinical versus RASP aspiration

| RASP aspiration | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Total | |

| Clinical positive | 13 (true positive) | 5 (false positive) | 18 (total of positive symptoms) |

| Clinical negative | 25 (false negative) | 27 (true negative) | 52 (total of negative symptoms) |

| Total | 38 (total of RASP positive) | 32 (total of negative RASP) | |

RASP = reflux aspiration scintigraphy

Reflux pulmonary aspiration study

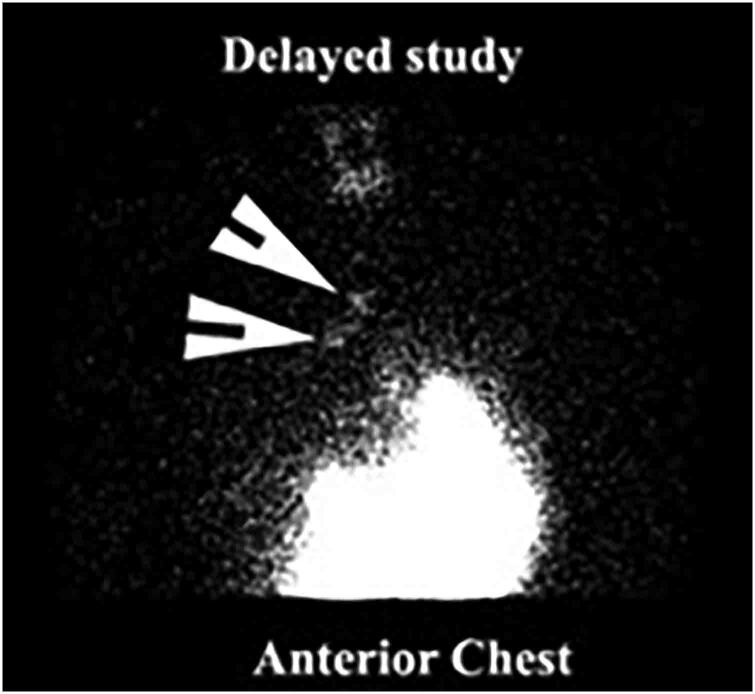

All patients underwent pulmonary scintigraphy testing at a single institution (CNI – Meadowbank, Sydney, Australia). A modern standardised scintigraphy test was performed using 100–150ml of water with 60–100MBq of 99mTc phytate, an agent approved for such studies in Australia. Dynamic images of the pharynx, oesophagus and stomach were obtained in the upright and supine positions. Delayed images were obtained 2h later to assess the presence of aspiration of tracer activity into the lungs. The technique has been described previously; studies were reported by a computer algorithm that assessed activity in the main airways relative to background activity with a cut-off of at least twice the background (Figure 2).15 This was possible because there is little systemic absorption of the orally administered isotope and therefore little activity in the lungs, other than scatter from the residual stomach activity. Most importantly, the technique of reflux aspiration scintigraphy was validated against a control group who did not develop abnormal counts in the lung.16

Figure 2 .

Pulmonary aspiration on reflux aspiration scintigraphy showing aspiration of tracer into the lungs (white arrow)

Echocardiographic assessment of cardiac compression by the PEH

Transthoracic echocardiography was performed at 1h after a meal as described by Naoum et al.17 Briefly, the left ventricular ejection fraction was calculated using Simpson’s biplane method. Right ventricular systolic pressure was derived from the peak velocity of the tricuspid regurgitant envelope obtained from continuous Doppler imaging. Left atrial compression was determined qualitatively and graded visually as none, mild, moderate and severe in standard projections. Quantification was done by measuring the anteroposterior left atrial diameter at the midpoint in the parasternal long-axis view just before opening of the mitral valve. Peak systolic and diastolic pulse–Doppler velocities at the left atrial inflow were recorded.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS v.24 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The Shapiro–Wilk’s test was used to test for normality of data. Chi-square test and Fisher’s exact test were used to analyse data. All data were presented with standard deviation (sd) or mean with range and confidence interval (CI). Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated to assess the best predictors of aspiration as shown by the RASP studies. Correlation between variables and the reference standard of RASP aspiration was expressed with the Spearman correlation coefficient for nonparametric variables. Statistical significance was based on a p-value of <0.05 for rejection of the null hypothesis. The sensitivity and specificity of clinical symptoms of aspiration in diagnosing an aspiration event were calculated using a conventional two-by-two table with results being recorded as dichotomous outcomes, with the reference standard being a positive finding on RASP.

Results

Large PEH was diagnosed in 96 consecutive patients between January 2012 and March 2017; 70 patients had a complete set of data. There were 54 females and the mean age was 68 (range 49–85; sd 9.16).

The most frequent symptoms reported by patients were dyspnoea (54 patients) followed by dysphagia and regurgitation (53 patients). Clinical symptoms of aspiration were present in 18/70 patients (25.7%) and RASP was positive for aspiration in 38/70 patients (54.3%) (Tables 3 and 4).

Table 3 .

Demographics of study group (N=70)

| Demographic | |

|---|---|

| Age±sd, years | 68±9.16 |

| Male, n (%) | 16 (22.9) |

| Female, n (%) | 54 (77.1) |

Table 4 .

RASP versus clinical aspirators (N=70)

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| RASP | Positive | 38 (54.3) |

| Negative | 32 (45.7) | |

| Clinical aspiration | Present | 18 (25.7) |

| Not present | 52 (74.3) |

RASP = reflux aspiration scintigraphy

The RASP aspiration study in 18 patients with clinically diagnosed aspiration confirmed clinical and historical pulmonary aspiration in 13 patients and did not demonstrate aspiration in 5 (Table 5). Of 38 patients with pulmonary aspiration confirmed on RASP, 25 did not have a clinical diagnosis of aspiration or silent aspiration. Neither clinical aspiration nor a RASP diagnosis of aspiration was present in 27 patients.

Table 5 .

Clinical symptomatology in predicting pulmonary aspiration (values in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals)

| Clinical symptoms | Frequency (N=70) | Sensitivity | Specificity | Positive predictor value | Negative predictor value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syncope | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Odynophagia | 1 | 0 (0–9.25) | 96.88 (83.78–99.92) | 0 | 44.93 (43.49–46.47) |

| Nausea | 7 | 7.89 (1.66–21.38) | 87.50 (71.01–96.49) | 42.86 (15.33–75.65) | 44.44 (40.52–48.44) |

| Bronchitis | 15 | 21.05 (9.55–37.32) | 78.12 (60.03–90.72) | 53.33 (31.75–73.74) | 45.45 (39.45–51.59) |

| Laryngospasm | 18 | 28.95 (15.42–45.90) | 78.12 (60.03–90.72) | 61.11 (40.84–78.15) | 48.08 (41.33–54.90) |

| Asthma | 18 | 28.95 (15.42–45.90) | 78.12 (60.03–90.72) | 61.11 (40.84–78.15) | 48.08 (41.33–54.90) |

| Aspiration | 18 | 34.21 (19.63–51.35) | 84.38 (67.21–94.72) | 72.22 (50.94–86.69) | 51.92 (44.75–68.91) |

| Anaemia | 23 | 34.21 (19.63–51.35) | 68.75 (49.99–83.88) | 56.52 (39.78–71.90) | 46.81 (38.81–54.97) |

| Sore throat | 25 | 34.21 (19.63–51.35) | 62.50 (43.69–78.90) | 52.00 (36.63–67.00) | 44.44 (35.98–53.24) |

| Mucous in throat | 25 | 39.39 (22.91–57.86) | 67.57 (50.21–81.99) | 52.00 (36.62–67.01) | 55.56 (46.73–64.05) |

| Dysphonia | 33 | 44.74 (28.62–61.70) | 50.00 (31.89–68.11) | 51.52 (39.31–63.54) | 43.24 (32.71–54.42) |

| Cough | 38 | 47.37 (30.98–64.18) | 37.50 (21.10–56.31) | 47.37 (36.94–58.03) | 37.50 (25.92–50.72) |

| Throat clearing | 40 | 55.26 (38.30–71.38) | 40.62 (23.70–59.36) | 52.50 (42.44–62.36) | 43.33 (30.66–56.95) |

| Chest pain | 45 | 71.05 (54.10–84.58) | 43.75 (26.36–62.34) | 60.00 (50.97–68.40) | 56.00 (40.29–70.59) |

| Early satiety | 46 | 65.79 (48.65–80.37) | 34.38 (18.57–53.19) | 54.35 (45.87–62.58) | 45.83 (30.62–61.86) |

| Heartburn | 51 | 71.05 (54.1–84.58) | 25 (11.46–43.4) | 52.94 (45.83–59.93) | 42.11 (25–61.34) |

| Dysphagia | 53 | 60.53 (43.39–75.96) | 6.25 (0.77–20.81) | 43.40 (36.87–50.16) | 11.76 (3.19–35.06) |

| Regurgitation | 53 | 71.05 (54.1–84.58) | 18.75 (7.21–36.44) | 50.94 (44.41–57.45) | 35.29 (18.5–56.72) |

| Dyspnoea | 54 | 76.32 (59.76–88.56) | 21.88 (9.28–39.97) | 53.70 (47.34–59.95) | 43.75 (24.60–64.96) |

The sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictor values of clinical symptomatology (Table 5) in predicting the presence of pulmonary aspiration were calculated. The most sensitive clinical predictor of pulmonary aspiration was dyspnoea (76.32%) with heartburn, regurgitation and chest pain being equally sensitive (71.05%). However, the subjective description of clinical aspiration was quite specific for pulmonary aspiration (84.38%).

Clinically silent aspiration apparent only on RASP occurred in 28% of patients. Clinical aspiration had a positive predictive value of 72.2% for pulmonary aspiration on RASP, followed by ‘asthma’ (61.11%). Clinical aspiration was not an accurate predictor of pulmonary aspiration frequency owing to its high ‘silent’ rate.

The ROC curves showed that the best combination for the detection of aspiration versus false positives was clinical aspiration and chest pain with a moderate value of area under the curve (>0.5) with all other variables being low (<0.5).

In the multivariate analysis of patients with aspiration on RASP, with or without consideration of cardiac compression, the only significant variable was the clinical symptom of aspiration (p=0.000). No other variable including dyspnoea, regurgitation or heartburn was a statistically significant predictor.

The presence of dysphagia was inversely related to the likelihood of RASP-identified aspiration events (Spearman’s correlation coefficient −0.39, p=0.001). No other clinical symptoms showed a statistically significant association. There was no statistically significant association between all other 18 clinical symptoms and pulmonary aspiration on RASP (Table 6).

Table 6 .

Clinical symptomatology and pulmonary aspiration on RASP (N=70)

| Pulmonary aspiration on RASP | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom present | Present (%) | Absent (%) | p-value |

| Syncope* | – | – | – |

| Odynophagia (n=1) | 0.00 | 100.00 | 0.457 |

| Nausea (n=7) | 42.86 | 57.14 | 0.403 |

| Bronchitis (n=15) | 53.33 | 46.67 | 0.581 |

| Aspiration (n=18) | 72.22 | 27.78 | 0.066 |

| Asthma (n=18) | 61.11 | 38.89 | 0.346 |

| Laryngospasm (n=18) | 61.11 | 38.89 | 0.346 |

| Anaemia (n=23) | 56.52 | 43.48 | 0.498 |

| Mucous in throat (n=25) | 52.00 | 48.00 | 0.485 |

| Sore throat (n=25) | 52.00 | 48.00 | 0.485 |

| Dysphonia (n=33) | 51.52 | 48.48 | 0.421 |

| Cough (n=38) | 47.37 | 52.63 | 0.153 |

| Throat clearing (n=40) | 52.50 | 47.50 | 0.459 |

| Chest pain (n=45) | 60.00 | 40.00 | 0.15 |

| Early satiety (n=46) | 54.35 | 45.65 | 0.593 |

| Heartburn (n=51) | 52.94 | 47.06 | 0.462 |

| Dysphagia (n=53) | 43.40 | 56.60 | 0.001 |

| Regurgitation (n=53) | 50.94 | 49.06 | 0.239 |

| Dyspnoea (n=54) | 53.70 | 46.30 | 0.544 |

*No patients had syncope

RASP = reflux aspiration scintigraphy

Cardiac inflow obstruction (compression) and dyspnoea

The results of echocardiography using the techniques of Naoum and Yannikas17 were available for 52 patients. Cardiac inflow abnormality due to PEH was present in 35/52 patients (67.3%); cardiac compression was severe in 27 patients and mild in 8. RASP was positive for aspiration in 11/17 patients without cardiac compression and in 19/35 patients with cardiac compression. Pulmonary aspiration was not associated with the presence of cardiac compression (p=0.558). There was no statistically significant association between any of the clinical symptoms and the presence of cardiac compression (Table 7).

Table 7 .

Clinical symptomatology and presence of cardiac compression (N=52)

| Cardiac compression | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Symptom present | Present (%) | Absent (%) | p-value |

| Syncope* | – | – | – |

| Odynophagia* | – | – | – |

| Nausea (n=2) | 100.00 | 0.00 | 0.449 |

| Bronchitis (n=12) | 66.67 | 33.33 | 0.608 |

| Aspiration (n=12) | 58.33 | 41.67 | 0.337 |

| Asthma (n=14) | 50.00 | 50.00 | 0.101 |

| Laryngospasm (n=12) | 58.33 | 41.67 | 0.337 |

| Anaemia (n=18) | 72.22 | 27.78 | 0.41 |

| Mucous in throat (n=16) | 62.50 | 37.50 | 0.426 |

| Sore throat (n=15) | 66.67 | 33.33 | 0.597 |

| Dysphonia (n=23) | 52.17 | 47.83 | 0.07 |

| Cough (n=26) | 65.38 | 34.62 | 0.5 |

| Throat clearing (n=27) | 62.96 | 37.04 | 0.346 |

| Chest pain (n=38) | 68.42 | 31.58 | 0.513 |

| Early satiety (n=41) | 70.73 | 29.27 | 0.253 |

| Heartburn (n=38) | 65.79 | 34.21 | 0.487 |

| Dysphagia (n=39) | 66.67 | 33.33 | 0.575 |

| Regurgitation (n=36) | 63.89 | 36.11 | 0.325 |

| Dyspnoea (n=44) | 65.91 | 34.09 | 0.477 |

*No patients had syncope or odynophagia

Cardiac compression was present in 29/44 (65%) patients with dyspnoea. Dyspnoea was not evident in six patients despite their having cardiac compression. Dyspnoea and cardiac compression were not related statistically (p=0.477). Severity of cardiac compression did not predict dyspnoea (p=0.542).

Dyspnoea without cardiac compression occurred in 15 of 44 patients, 9 of whom had pulmonary aspiration on RASP.

Dyspnoea among the pulmonary aspiration patients

Patients who have clinical and/or RASP aspiration were considered to be ‘aspirators’ (N=43); true-negative patients who had neither clinical aspiration nor RASP aspiration were considered ‘non-aspirators’ (N=27). Dyspnoea was present in both aspirators and non-aspirators (77% and 78%, respectively).

The 52 patients with echocardiogram results were grouped into those with aspiration (N=33, 63%) and those without aspiration (N=19, 37%), as classified previously. Among those with aspiration, 26/33 had dyspnoea; no statistically significant correlation between dyspnoea and cardiac compression was found (p=0.629). Eighteen patients without aspiration had dyspnoea in (18/19, 95%); 13 of these 18 patients had cardiac compression (72.2%) and 5 did not (27.8%). There was no statistically significant relationship between dyspnoea and absence of clinical or scintigraphic aspiration (p=0.125) or the presence of dyspnoea and cardiac compression (p=0.539). Aspiration and/or cardiac compression would appear to be related to dyspnoea in 44/52 patients (84.6%).

Possible causes of dyspnoea: cardiac compression or aspiration?

There were 21 patients (78%) who complained of dyspnoea among the non-aspirating patients (N=27) and 18 (72.2%) had cardiac compression, the likely cause of dyspnoea. In patients without cardiac compression (17/52), 15 complained of dyspnoea. Of these 15, 10 patients (67%) had aspiration as a likely cause of dyspnoea. There were two patients without dyspnoea who had silent aspiration.

Discussion

RASP was assessed in an enhanced modified scintigraphic reflux study that has been validated against the current standards of impedance/pH and manometry at a single centre.14,15 Research in a series of normal participants using this new technology did not identify any cases of pulmonary aspiration.18 Subjective reporting of ‘aspiration’ was the only statistically significant variable in the multivariate analysis of RASP-positive aspiration patients, and this was the most useful clinical symptom in predicting pulmonary aspiration. It was the most specific subjective symptom for pulmonary aspiration on RASP (72.2%), as confirmed on the ROC curve analysis.

Dyspnoea was the most sensitive symptom in predicting pulmonary aspiration, but may also be caused by anaemia, cardiac compression or pulmonary disease and was so prevalent in this study that it was non-discriminatory. We have previously shown multiple mechanisms for dyspnoea in PEH including cardiac compression and pulmonary gas trapping19 in association with PEH so to find one predominant cause in an individual patient seems unlikely. Approximately one-third of patients in this study did not report symptomatic aspiration despite having a positive RASP study, hence appeared clinically ‘silent’. This is an important observation for the clinical management of this patient group because they are at risk of pulmonary symptoms and complications.

Five patients had clinical symptoms of aspiration without evidence of aspiration on RASP. Common symptoms present in all five of ‘false positives’ were regurgitation and dysphagia. Whether these patients truly had no pulmonary aspiration remains questionable, as reflux may be intermittent in nature and therefore the RASP test may underestimate aspiration events due to the small period tested (2h) and the relatively small volume challenge (100–150ml). The daily situation of a substantial meal was not investigated for aspiration in this study. It has also been reported that aspiration is significantly worse when supine and at night,20 although the supine time evaluated was not for a prolonged period.

Subjectively reported aspiration had the highest positive predictor value of 72.22%, followed by asthma and laryngospasm at 61.11% for pulmonary aspiration on RASP. These symptoms were accurate for clinical use, and potentially provide a clinical basis for patients being treated for aspiration based on symptoms alone.

Dyspnoea is one of the most common symptoms in patients with PEH,17 and was the most sensitive clinical symptom for pulmonary aspiration in this study. As the PEH became increasingly intrathoracic and large, symptoms begin to mimic respiratory or cardiac disease due to compression of the left atrium or the onset of gas trapping.19 It is tempting to conclude that dyspnoea is caused by the volume effect of the HH; however, Naoum et al showed minimal improvement (within normal range) in respiratory function in patients with PEH after surgical repair;19 similarly Zhu et al found no respiratory function improvement following hernia repair.21 Cardiac compression effects are recognised but the proportional contribution of pulmonary aspiration of refluxate to the pathophysiology of dyspnoea in PEH patients remains unknown. Perplexingly, unlike the study by Naoum et al,17 there was no statistically significant association between dyspnoea and cardiac compression in this cohort.

Although cardiac inflow obstruction is a recognised cause of dyspnoea, it appears that there is a group of patients without evidence of cardiac compression as a cause of dyspnoea. However, aspiration may be the alternate explanation for dyspnoea in this group. More than two-thirds of patients with pulmonary aspiration but without cardiac compression experienced dyspnoea. This supports the hypothesis that pulmonary aspiration is likely to be instrumental in producing dyspnoeic symptoms in patients with PEH. It may also explain the poor correlation between cardiac compression and dyspnoea, but this series lack data to show a group in whom pulmonary change may have contributed to dyspnoea.

Symptoms that should alert the clinician to the likelihood of pulmonary aspiration include dyspnoea, late onset of ‘asthma’ and laryngospasm. Our group have previously shown dysphonia to be a strong clinical indicator of pulmonary aspiration.15 Lung aspiration as a cause of these symptoms has not previously been well recognised in this group of patients.22,23

The negative relationship between dysphagia and pulmonary aspiration has not been reported previously. The ‘kinking’ or compression effect of the intrathoracic stomach on the lower oesophagus (autofundoplication) causing dysphagia may reduce typical ‘reflux’ in unoperated patients (Figure 1). It is a common clinical phenomenon that patients report the reduction of heartburn and regurgitation symptoms with the emergence of early satiety, postprandial chest discomfort and dysphagia in the later course of the disease. Onset of dysphagia would seem to signal the anti-reflux effect of the distorted anatomy.

Reflux aspiration is likely implicated in the symptomatology of pulmonary disease. The relationship between GORD, HH and respiratory disease such as recurrent pneumonia, late-onset asthma, bronchiectasis and IPF has been described.24 Oesophageal dysmotility in patients with GORD has a strong correlation with pulmonary aspiration.25 Non-specific dysmotility is common among patients with PEH, HH and GORD in clinical practice, further putting this group at risk of aspiration.26 Sweet et al27 concluded that although exact mechanisms remained uncertain, continued aspiration stemming from GORD seemed to exacerbate pre-existing pulmonary disease as well as causing direct damage. There is a recognised risk of death from aspiration and pneumonia in the group of patients with PEH.1 This supports the contention that lesser degrees of aspiration and even symptomatically silent aspiration may occur, because it is more likely that a spectrum of disease exists varying from mild to severe.

The effect of anti-reflux surgery on symptoms and respiratory protection has been examined. Falk et al have shown surgical intervention for GORD partially resolved laryngoesophageal symptoms such as chronic cough and reflux;15 Fernando et al found that anti-reflux surgery resulted in symptomatic relief of respiratory symptoms and decreased the requirement for pulmonary medications.28 Khoma et al showed the effectiveness of fundoplication in objective reflux pulmonary aspiration.25 A small study that examined the effect of anti-reflux surgery on the outcomes of lung transplantation has shown that surgery prevented reflux contamination to graft.10 Adaba et al showed that laparoscopic fundoplication improved symptoms of reflux as well as respiratory manifestations of GORD.29 Müller-Stich et al showed quality of life symptomatic benefit of fundoplication in PEH in a randomised controlled trial,16 possibly reflecting an improvement in pulmonary function. Pulmonary reflux aspiration can occur in multiple scenarios, and large PEH appears to be a previously unrecognised situation.

Although pulmonary aspiration with PEH was clinically silent in nearly one-third of our patients, many had dyspnoea possibly originating from pulmonary contamination and clinical therapy would need to take account of this frequent situation. This also has implications for anaesthesia with a high aspiration risk being especially of concern for sedation in colonoscopy.30

Conclusions

GORD, dyspnoea and silent pulmonary aspiration were frequent occurrences in the presence of giant PEH. Subjective aspiration was the most specific and positive predictor of pulmonary aspiration. Dyspnoea in PEH patients may be caused by pulmonary aspiration, cardiac compression in this study and gas trapping as described elsewhere. High rates of pulmonary aspiration in PEH patients may support anti-reflux repair.

References

- 1.Sihvo EI, Salo JA, Rasanen JV, Rantanen TK. Fatal complications of adult paraesophageal hernia: a population-based study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009; 137: 419–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim C, Ouyang W, Dass Cet al. Hiatal hernia on chest high-resolution computed tomography and exacerbation rates in COPD individuals. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis: J COPD Found 2016; 3: 570–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee JS. The role of gastroesophageal reflux and microaspiration in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Clin Pulm Med 2014; 21: 81–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morice AH. Airway reflux as a cause of respiratory disease. Breathe 2013; 9: 256–266. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rantanen TK, Sihvo EIT, Räsänen JV, Salo JA. Gastroesophageal reflux disease as a cause of death is increasing: analysis of fatal cases after medical and surgical treatment. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 246–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noth I, Zangan SM, Soares RVet al. Prevalence of hiatal hernia by blinded multidetector CT in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J 2012; 39: 344–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraser A, Delaney B, Moayyedi P. Symptom-based outcome measures for dyspepsia and GERD trials: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2005; 100: 442–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sobieraj DM, Coleman SM, Coleman CI. US prevalence of upper gastrointestinal symptoms: a systematic literature review. Am J Manag Care 2011; 17: e449–e458. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vakil N, van Zanten SV, Kahrilas Pet al. The Montreal definition and classification of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a global, evidence-based consensus paper. Z Gastroenterol 2007; 45: 1125–1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yates RP, Pellegrini CA, Oelschlager KB. Assessment, evaluation, and management: evolving knowledge and New horizons. gastroesophageal reflux and esophageal dysmotility in patients undergoing evaluation for lung transplantation. Lung Transplant: Evolving Knowledge and New Horizons. Berlin: Springer; 2018: pp 279–299. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittal RK, Holloway R, Penagini Ret al. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Gastroenterology 1995; 109: 601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ayazi S, Lipham JC, Hagen JAet al. A new technique for measurement of pharyngeal pH: normal values and discriminating pH threshold. J Gastrointest Surg 2009; 13: 1422–1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ravelli AM, Panarotto MB, Verdoni Let al. Pulmonary aspiration shown by scintigraphy in gastroesophageal reflux-related respiratory disease. Chest 2006; 130: 1520–1526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Falk M, Van der Wall H, Falk GL. Differences between scintigraphic reflux studies in gastrointestinal reflux disease and laryngopharyngeal reflux disease and correlation with symptoms. Nucl Med Commun 2015; 36: 625–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falk GL, Beattie J, Ing Aet al. Scintigraphy in laryngopharyngeal and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a definitive diagnostic test? World J Gastroenterol 2015; 21: 3619–3627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Müller-Stich BP, Achtstätter V, Diener MKet al. Repair of paraesophageal hiatal hernias–Is a fundoplication needed? A randomized controlled pilot trial. J Am Coll Surg 2015; 221: 602–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naoum C, Falk GL, Ng ACet al. Left atrial compression and the mechanism of exercise impairment in patients with a large hiatal hernia. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 58: 1624–1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burton L, Joffe D, Mackey DWet al. A transformational change in scintigraphic gastroesophageal reflux studies: A comparison with historic techniques. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging 2020; 41: 136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naoum C, Kritharides L, Ing Aet al. Changes in lung volumes and gas trapping in patients with large hiatal hernia. Clin Respir J 2017; 11: 139–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barish CF, Wu WC, Castell DO. Respiratory complications of gastroesophageal reflux. Arch Intern Med 1985; 145: 1882–1888. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhu JC, Becerril G, Marasovic Ket al. Laparoscopic repair of large hiatal hernia: impact on dyspnoea. Surg Endosc 2011; 25: 3620–3626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dai AG, Liang YK, Liu QL. Application of radionuclide gastroesophageal reflux imaging in patients with chronic bronchitis and asthma. Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi 1994; 17: 227–229, 55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ducolone A, Vandevenne A, Jouin Het al. Gastroesophageal reflux in patients with asthma and chronic bronchitis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1987; 135: 327–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Allaix ME, Fisichella PM, Noth Iet al. The pulmonary side of reflux disease: from heartburn to lung fibrosis. J Gastrointest Surg 2013; 17: 1526–1535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoma O, Falk SE, Burton Let al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and aspiration: does laparoscopic fundoplication significantly decrease pulmonary aspiration? Lung 2018; 196: 491–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swanstrom LL, Jobe BA, Kinzie LR, Horvath KD. Esophageal motility and outcomes following laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair and fundoplication. Am J Surg 1999; 177: 359–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sweet MP, Patti MG, Hoopes Cet al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and aspiration in patients with advanced lung disease. Thorax 2009; 64: 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fernando HC, El-Sherif A, Landreneau RJet al. Efficacy of laparoscopic fundoplication in controlling pulmonary symptoms associated with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Surgery 2005; 138: 612–616; discussion 6-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Adaba F, Ang CW, Perry Aet al. Outcome of gastro-oesophageal reflux-related respiratory manifestations after laparoscopic fundoplication. Int J Surg 2014; 12: 241–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berg PW KD, Schindler A, Doehn M. Hiatal hernia and risk of aspiration in anesthesia induction. Anesth Reanim 2001; 26: 21–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]