Abstract

Aims

Current troponin cut-offs suggested for the post-operative workup of patients following coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery are based on studies using non-high-sensitive troponin assays or are arbitrarily chosen. We aimed to identify an optimal cut-off and timing for a proprietary high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) assay to facilitate post-operative clinical decision-making.

Methods and results

We performed a retrospective analysis of all patients undergoing elective isolated CABG at our centre between January 2013 and May 2019. Of 4684 consecutive patients, 161 patients (3.48%) underwent invasive coronary angiography after surgery, of whom 86 patients (53.4%) underwent repeat revascularization. We found an optimal cut-off value for peak hs-cTnI of >13 000 ng/L [>500× the upper reference limit (URL)] to be significantly associated with repeat revascularization within 48 h after surgery, which was internally validated through random repeated sampling with 1000 iterations. The same cut-off also predicted 30-day major adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality after a median follow-up of 3.1 years, which was validated in an external cohort. A decision tree analysis of serial hs-cTnI measurements showed no added benefit of hs-cTnI measurements in patients with electrocardiographic or echocardiographic abnormalities or haemodynamic instability. Likewise, early post-operative hs-cTnI elevations had a low yield for clinical decision-making and only later elevations (at 12–16 h post-operatively) using a threshold of 8000 ng/L (307× URL) were significantly associated with repeat revascularization with an area under the curve of 0.92 (95% confidence interval 0.88–0.95).

Conclusion

Our data suggest that for hs-cTnI, higher cut-offs than currently recommended should be used in the post-operative management of patients following CABG.

Keywords: High-sensitivity cardiac troponin, Post-operative myocardial infarction, Invasive coronary angiography , Coronary artery bypass grafting

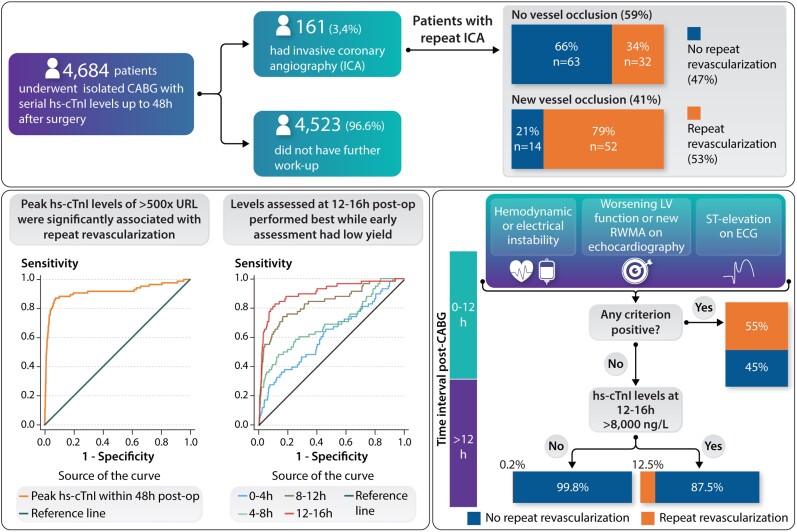

Structured Graphical Abstract

High-sensitivity cardiac troponin I after coronary artery bypass grafting for postoperative decision-making.

See the editorial comment for this article ‘Isolated early peak cardiac troponin for clinical decision-making after elective cardiac surgery: useless at best’, by Evangelos Giannitsis and Norbert Frey, https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehab786.

Background

Perioperative myocardial injury evidenced by cardiac biomarker elevation is common after cardiac surgery.1,2 The fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (UDMI)2 defines perioperative or Type 5 myocardial infarction as an elevation of cardiac troponin (cTn) of 10× the 99th percentile upper reference limit (URL) combined with (i) new pathological Q waves on electrocardiogram (ECG), (ii) flow-limiting angiographic complications, and/or (iii) new loss of viable myocardium on imaging.2 While valuable as a definition, these criteria are not to be used to indicate the need for invasive workup of post-operative patients.

For clinical decision-making, numerous algorithms by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) joint working group,1 the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions,3 and the Academic Research Consortium-24 have been proposed utilizing the best available evidence on the relationship between cTn levels and mortality or evidence of myocardial ischaemia by employing a combination of different cTn cut-off values with additional criteria similar to the above-mentioned definition of Type 5 myocardial infarction. These algorithms propose an isolated elevation in cTn levels within the first 48 h after surgery of ≥70× URL or elevations of cTn levels ranging from >10× URL to ≥35× URL combined with at least one of the above-mentioned additional abnormalities as criteria necessitating further workup, in most cases invasive coronary angiography (ICA). Several limitations exist for the cTn cut-off values used in these definitions: (i) they have either been arbitrarily chosen, as in the case of the UDMI,2 or (ii) are based solely on prognostic associations, which are not necessarily suitable to inform further clinical decision-making regarding revascularization.1,3,4

Herein, we describe the kinetics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I (hs-cTnI) following elective coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery, and we identify the optimal hs-cTnI cut-off values to correlate with the clinical decision for repeat revascularization, to indicate angiographic vessel occlusion, and to relate post-operative hs-cTnI levels to clinical outcome.

Methods

We performed a retrospective analysis of all patients who underwent CABG surgery between 1 January 2013 and 1 May 2019 at our centre. Exclusion criteria included urgent or emergent procedures (e.g. due to acute coronary syndromes), paediatric (<18 years) patients, as well as CABG combined with the valvular procedure or ablation for atrial fibrillation. Electrocardiogram changes [new Q waves, new left bundle branch block (LBBB), or ST-segment elevations], echocardiographic abnormalities (new regional wall motion abnormalities and/or worsening of left ventricular function), and cardiac biomarkers were analysed. We reviewed the medical records for all patients, and demographic data, echocardiographic, and laboratory parameters were collected.

Twenty-four hours before surgery, blood samples were obtained for hs-cTnI levels from venous puncture for the first time. Thereafter, blood samples were collected serially between the end of surgery (time zero) and predefined time-points at 4, 8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 40, and 48 h post-operatively. Samples were analysed in our hospital laboratory facility using standard techniques. Plasma levels of hs-cTnI were measured on Abbott ARCHITECT STAT High Sensitivity Troponin I blood test (Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL, USA). This high-sensitivity assay has been implemented at our institution since 1 January 2013 and we will refer to it as hs-cTnI in this manuscript. According to the manufacturer, this assay has a limit of detection of 1.2 ng/L and an interassay coefficient of variation of <10% at 4.7 ng/L. The URL (99th percentile) was determined by the manufacturer as 26 ng/L for both women and men in general. However, the manufacturer backed up by guideline recommendations promotes the use of gender-specific cut-offs with a URL of 16 ng/L for women and 34 ng/L for men. Multiples of URLs are reported to allow better comparability of hs-cTnI levels. All patients received an initial ICA within 30 days before surgery. In patients who underwent repeat ICA after surgery, comparisons of ICA post- and preoperatively were done by an experienced cardiologist to analyse new coronary or bypass graft lesions. Patients underwent ICA in accordance with a predefined standard operating procedure (SOP) of our hospital, which recommended performing further workup and ICA if patients developed otherwise unexplained haemodynamic or electrical instability or ischaemic ECG changes (ST-segment elevations or new LBBB or pathological Q waves) or if they developed new regional wall motion abnormalities or worsening of ventricular function on echocardiography or if they had large increases of cardiac biomarkers that were considered significant based on the assessment of the heart team. Electrocardiograms of patients who underwent repeat ICA were reviewed by an experienced cardiologist. The following ECG changes were reported: ST-segment deviations at the J-point in two or more contiguous leads with cut-off points ≥0.2 mV in leads V1, V2, or V3 and ≥0.1 mV in other leads, new pathological Q waves (Q wave ≥30 ms and ≥0.1 mV deep) in two or more contiguous leads, and new LBBB. All ECG definitions were in accordance with American Heart Association recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the ECG.5–7

The primary outcome was repeat revascularization, defined as ICA with consequent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) or redo surgery based on clinical decision of the local heart team. Sensitivity analyses were performed looking for gender-specific cut-off values that correlated with the primary outcome. Secondary analyses were performed to assess the association of hs-cTnI levels with the following events: new coronary vessel (native or bypass) occlusion, major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) within 30 days after surgery, and long-term mortality. Major adverse cardiovascular events was defined by at least one of the following events within 30 days after surgery: myocardial infarction (defined according to the UDMI),2 stroke, or in-hospital mortality. To test for internal validity, the study population was randomly divided into two groups stratified according to the primary outcome (repeat revascularization) and repeat ICA. The utility of hs-cTnI was tested in the first cohort of patients (Group 1, derivation cohort) and obtained cut-off values were then validated in the second cohort (Group 2, validation cohort). Furthermore, we performed a repeated random sampling stratified by the primary outcome and by use of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) using 1000 iterations (further details in the Supplementary material online, Methods). To check for external validity, we analysed data from The Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, Australia, where hs-cTn I assays (Abbott ARCHITECT and Abbott Alinity) were used which had similar dynamics and reference values to the assay used in our study cohort. The external validation cohort included patients who are part of the ongoing Dexamethasone for Cardiac Surgery-II Trial (DECS-II, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03002259). Patients in our study were followed up after discharge through routine phone calls and standardized questionnaires. Data on mortality were collected from local registry offices and by contacting patients’ general practitioners. Patients signed informed consent forms preoperatively that allowed collection of data and future contacts (phone calls and email) and participation in our local registry. The study was approved by the local ethics committee (Reg. Nr. 2019-501) and was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS V26 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and R version 4.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Data are expressed as percentages for categorical variables and as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median ± interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables. We compared continuous variables using Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U-test as appropriate. Differences between multiple groups with a normal distribution were compared by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Within-group differences were analysed using repeated-measures ANOVA or paired t-test. If no normal distribution was found, ANOVA on ranks (Kruskal–Wallis) was performed, and the Friedmann test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test were used for within-group comparisons. Comparisons of categorical variables between groups were performed by Pearson’s χ 2 test, for expected frequencies <5 by Fisher’s exact test. Receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed to identify optimal cut-off values for hs-cTnI, and sensitivity, specificity, negative predictive value (NPV), positive predictive value (PPV), and accuracy for each cut-off were calculated. Comparisons of cut-off values were done by the McNemar χ 2 test. The performance of cut-off values between study and validation groups was done utilizing the χ 2 test. We calculated overall net reclassification improvement (NRI)8 using the following category-based formula: NRI = event NRI + non-event NRI, whereby event NRI is [(number of events classified up − number of events classified down)/number of events] and non-event NRI is [(number of non-events classified down − number of non-events classified up)/number of non-events]. Events of interest included repeat revascularization, angiographic vessel occlusion, and Type 5 myocardial infarction according to the UDMI+2 while different thresholds for hs-cTnI were applied for classification.

All P-values were two-sided and statistical significance was assumed at a P-value of 0.05. Logistic regression analysis was implemented to assess the correlation between derived cut-off values and post-operative outcomes. The Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used for survival analyses. Univariate analyses were initially performed and all parameters with P < 0.1 were then included in multivariate analysis. A repeated random sampling of two-thirds of the total cohort was performed to assess the internal validity. A decision tree analysis was performed to aid clinical decision-making post-operatively. Further details on the statistical methods used are provided in the Supplementary material online, Methods, which also includes details of the process of choosing hs-cTnI thresholds.

Results

Baseline characteristics

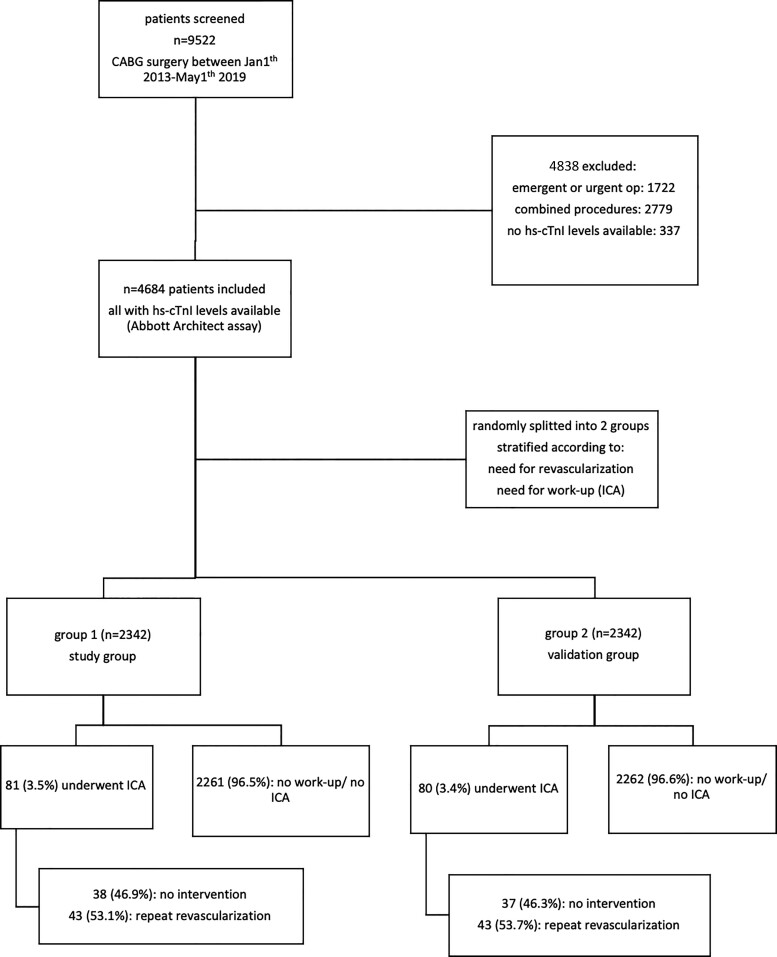

From 1 January 2013 until 1 May 2019, a total of 9522 patients underwent CABG surgery at our hospital. After the application of exclusion criteria, 4684 patients were finally included in the study [mean age 67.4 ± 9.7 years, 19.4% female, mean angina severity according to the Canadian Cardiovascular Society scale (CCS) 1.5 ± 1.1, mean EuroSCORE II 2.0 ± 2.5%]. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Procedures included 3992 (85.2%) off-pump procedures (without the use of CPB), while the remaining 692 procedures were on-pump procedures (14.8%) including 69 patients with an on-pump beating-heart technique. Figure 1 shows the study flowchart.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Variable | Baseline | Patients with peak hs-cTnI >500× URL | Patients with peak hs-cTnI <500×URL | P-value* (two-sided) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n (%) | 4684 (100) | 387 (8.3) | 4297 (91.7) | |

| Age (years), mean (±SD) | 67.39 (±9.71) | 68.76 (±10.03) | 67.26 (±9.67) | 0.005 |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (±SD) | 28.56 (±4.61) | 27.77 (±4.31) | 28.63 (±4.63) | <0.001 |

| Female sex, n (%) | 909 (19.4) | 94 (24.29) | 815 (19) | <0.001 |

| Angina Severity CCS Class, median (IQR) | 1.0 (2.0) | 1.0 (1.0) | 1.0 (2.0) | 0.196 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL), mean (±SD) | 1.12 (±0.70) | 1.19 (±0.77) | 1.11 (±0.69) | 0.055 |

| eGFR (mL/min/1.73 m2), median (IQR) | 75 (28) | 70 (31) | 76 (28) | <0.001 |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL), median (IQR) | 14.3 (2) | 14.1 (2.1) | 14.3 (2) | 0.061 |

| LDL (mg/dL), mean (±SD) | 111.08 (±42) | 115.28 (±43.59) | 110.70 (±41.86) | 0.12 |

| HbA1c (%), median (IQR) | 5.8 (1.2) | 5.8 (1.1) | 5.8 (1.2) | 0.55 |

| EuroSCORE II, median (IQR) | 1.26 (1.36) | 1.53 (2.19) | 1.25 (1.31) | <0.001 |

| LVEF baseline (%), median (IQR) | 58 (13) | 57 (12) | 58 (13) | 0.69 |

| COPD, n (%) | 228 (4.84) | 12 (3.1) | 216 (5.03) | <0.001 |

| History of AF, n (%) | 2 30 (4.91) | 28 (7.23) | 202 (4.71) | <0.001 |

| Prior cardiac surgery, n (%) | 177 (3.78) | 33 (8.53) | 144 (3.36) | <0.001 |

| Arterial hypertension, n (%) | 4160 (88.81) | 350 (90.44) | 3803 (88.65) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 1739 (37.13) | 142 (36.69) | 1593 (37.13) | <0.001 |

| PAD, n (%) | 581 (12.40) | 60 (15.50) | 520 (12.12) | <0.001 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 2012 (42.96) | 162 (41.86) | 1846 (43.04) | <0.001 |

| Prior stroke, n (%) | 161 (3.44) | 12 (3.1) | 149 (3.47) | <0.001 |

| Chronic dialysis, n (%) | 65 (1.39) | 8 (2.07) | 57 (1.33) | <0.001 |

| History of PCI, n (%) | 1448 (30.91) | 126 (32.56) | 1319 (30.75) | 0.01 |

| History of MI, n (%) | 1016 (21.69) | 88 (22.74) | 927 (21.61) | <0.001 |

| CPB use, n (%) | 692 (14.77) | 128 (33.07) | 564 (13.15) | <0.001 |

| Time on CBP (min), median (IQR) | 84.5 (38) | 91 (51) | 84 (36) | 0.33 |

| Aortic cross-clamp time (min), median (IQR) | 62 (28) | 70 (38.75) | 61 (28) | 0.03 |

| Duration of procedure (min), median (IQR) | 198 (64) | 226 (84.5) | 196 (64) | <0.001 |

| LIMA bypass, n (%) | 4418 (94.32) | 348 (89.92) | 4063 (94.71) | <0.001 |

| Total arterial bypasses, n (%) | 1199 (25.60) | 73 (18.86) | 1125 (26.22) | <0.001 |

| Length of ICU stay (h), median (IQR) | 23 (26) | 47 (89.75) | 22 (22) | <0.001 |

| Duration on ventilator (h), median (IQR) | 7.98 (4.66) | 10.36 (11.85) | 7.83 (4.34) | <0.001 |

| Length of hospitalization (days), median (IQR) | 12 (3) | 13 (5.5) | 12 (13) | <0.001 |

SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; CCS, Canadian Cardiovascular Society; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate, according to the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; AF, atrial fibrillation; PAD, peripheral arterial disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; MI, myocardial infarction; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; LIMA, left internal mammary artery; hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; URL, upper reference limit.

P-value for comparing those with peak hs-cTnI > 500×URL versus <500× URL.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Perioperative kinetics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I

Peak levels of hs-cTnI were available for all patients while serial levels were available in the majority of patients (further details are represented in the Supplementary material online, Section IX). The median peak preoperative hs-cTnI level was 0.35× URL, and the median peak post-operative hs-cTnI level was 93.0× URL with a median time to peak hs-cTnI of 8.1 h in the overall collective (Figure 2A). Patients who underwent on-pump CABG had significantly higher hs-cTnI levels when compared with off-pump CABG, throughout the whole time course (Supplementary material online, Figure A1). Peak hs-cTnI levels did not differ significantly between genders. Detailed data on gender-specific kinetics are presented in the Supplementary material online, Section II. About 4.7% of the overall study cohort had elevated baseline hs-cTnI levels of more than 10× URL. Those patients had significantly higher post-operative peak hs-cTnI levels compared with patients with low baseline levels (Supplementary material online, Section VIII, Figure A7).

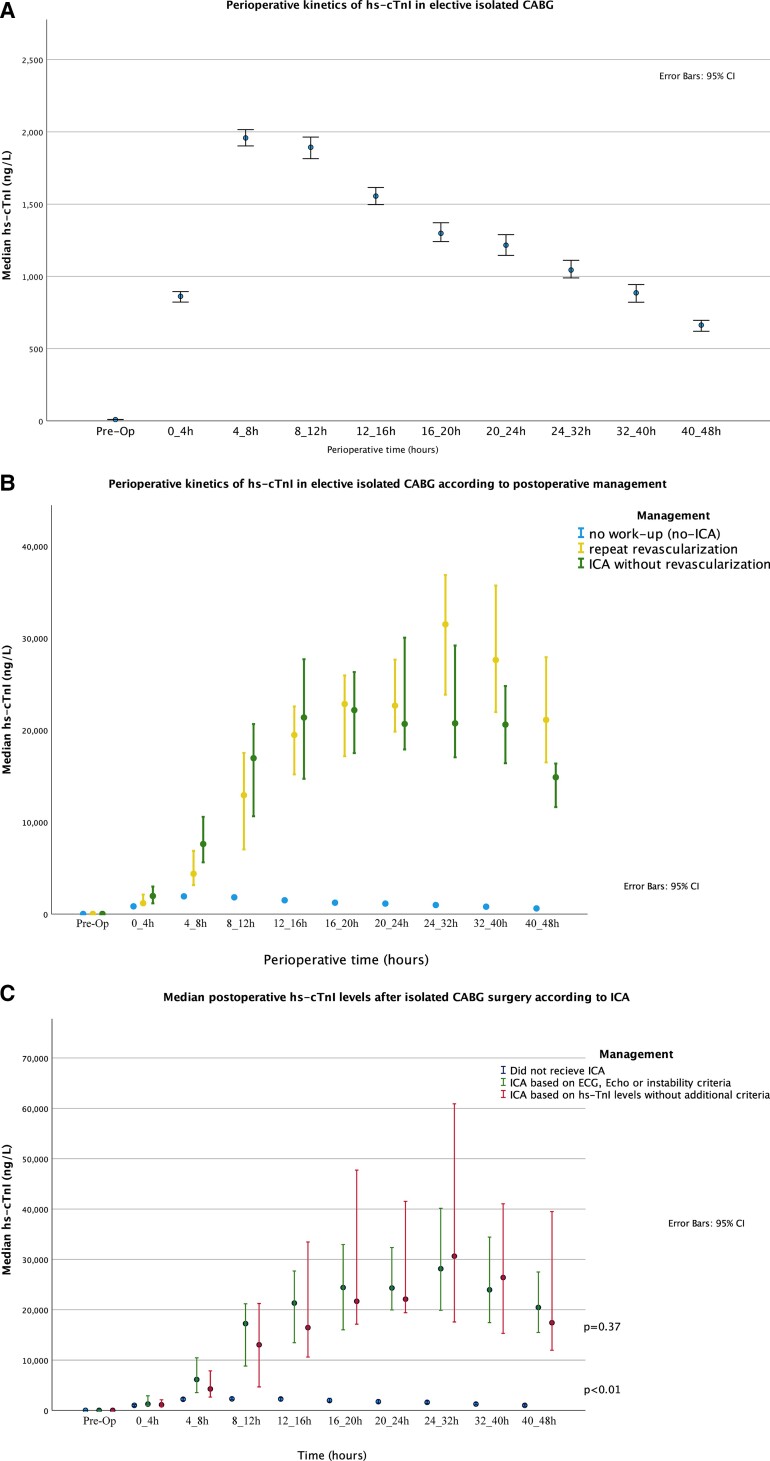

Figure 2.

Perioperative kinetics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I: (A) perioperative kinetics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I in the overall collective; (B) perioperative kinetics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I according to post-operative management; (C) perioperative kinetics of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I according to invasive coronary angiography indication.

Patients were subsequently separated into those with an uneventful course, those revascularized, and those undergoing ICA without revascularization (Figure 2B). Preoperative levels were principally within the normal range for all groups. In patients with an uneventful post-operative course, hs-cTnI levels reached their peak of 90×URL at a median of 8.0 h, after which they gradually decreased. In contrast, revascularized patients had a bimodal curve with a first peak of 992 × URL at a median of 18.5 h (before ICA, which was done at a median of 20.7 h after surgery) and a second peak of 1415×URL at a median of 25.3 h post-operatively, after which hs-cTnI levels rapidly decreased. Patients with ICA not undergoing revascularization also showed a rapid increase with a peak of 1096×URL at a median time of 17 h. Notably, hs-cTnI levels were similar across all groups during the first 4 h after surgery and the curves diverged not before 4–8 h with a clear difference occurring after 8 h (Table 2).

Table 2.

Post-operative high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels

| No ICA or no intervention (n = 4521) | Repeat revascularization (n = 86) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Median (IQR) | Median (IQR) | ||

| Baseline hs-cTnI (ng/L) | 9.0 (19) | 14.5 (34) | 0.06 |

| hs-cTnI peak within 24 h (ng/L) | 2407 (3231) | 25 800 (30 390) | <0.001 |

| hs-cTnI peak within 48 h (ng/L) | 2407 (3231) | 36 800 (43 006) | <0.001 |

| Time to peak hs-cTnI within 24 h (h) | 8.0 (7.0) | 18.5 (5.7) | <0.001 |

| Time to peak hs-cTnI within 48 h (h) | 8.0 (7.6) | 25.0 (13.4) | <0.001 |

Peak levels within 24 and 48 h post-surgery are represented. P-value represents two-sided non-parametric comparison, P-values were not adjusted for multiple comparisons, applying the Bonferroni correction for multiple tests did not change significant comparisons.

ICA, invasive coronary angiography; hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; IQR, interquartile range.

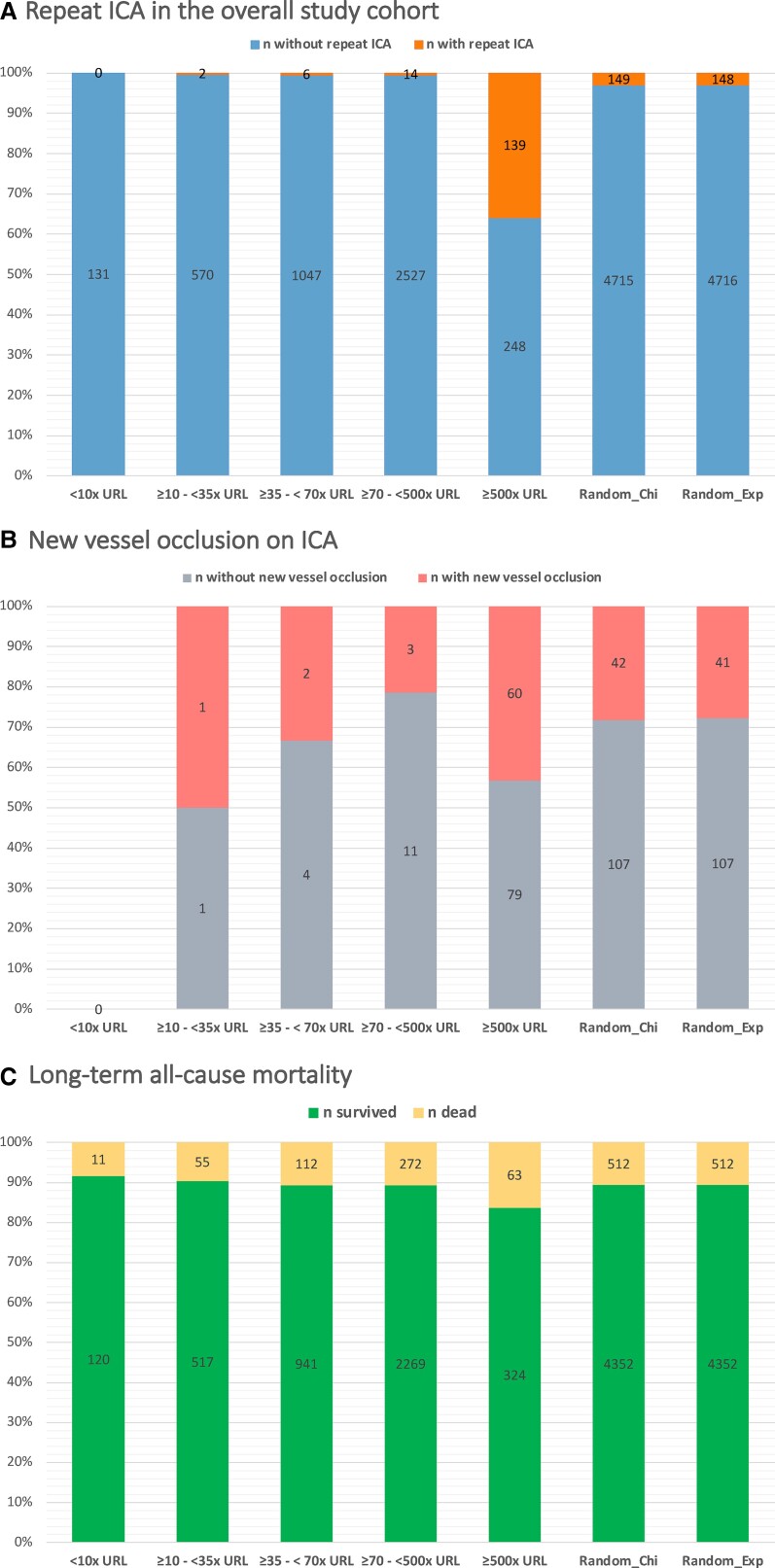

Of the 161 patients who received repeat ICA, 53 patients (33%) met the ECG criteria for ST-segment elevation, 35 patients (21.7%) met the echocardiographic criteria, and 34 patients (21.1%) met the haemodynamic instability criteria. However, 27 patients met more than one criterion simultaneously while the remaining 66 patients (41%) underwent repeat ICA based solely on hs-cTnI levels elevation. The relationship between hs-cTnI levels and ICA indication is represented in Figure 2C which shows that patients who met ECG, echocardiographic, or haemodynamic instability criteria had higher hs-cTnI levels than those who did not receive ICA. However, levels of hs-cTnI showed a similar extent of elevation in patients who underwent repeat ICA regardless of additional criteria (P = 0.37). The relationship between hs-cTnI levels and repeat ICA is represented in Figure 3A as a proportion analysis and in Supplementary material online, Section XV as a spline function, while Figure 3B shows the relationship between hs-cTnI levels and new vessel occlusion on ICA.

Figure 3.

Proportion analysis of the association between high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels and outcomes: (A) repeat invasive coronary angiography in the overall study cohort; (B) new vessel occlusion on invasive coronary angiography; (C) long-term all-cause mortality. URL, the 99th percentile upper reference limit (26 ng/L). Random_Exp and Random_Chi are randomly created cut-offs created following a Monte-Carlo-based approach utilizing an exponential and a χ 2 distributions, respectively. The proportion for >500×URL was significantly higher than other thresholds in all three categories (P < 0.001 for all comparisons). (Details on the methods are provided in the Supplementary material online, analysis of methods.)

Repeat revascularization after surgery (primary outcome)

The primary outcome of repeat revascularization based on clinical judgement of the heart team occurred in 1.8% of the total cohort (n = 86), while ICA without revascularization was performed in 1.6% of the total cohort (n = 77). Of the revascularized group, 45.3% (n = 39) underwent PCI and 54.7% (n = 47) required redo operation (of which PCI was not successful in 12.7% (n = 6) and not feasible in the remaining cases). Of the non-revascularized group, 18.2% (n = 14) had a new vessel occlusion, and 16.8% (n = 13) had a new significant stenotic lesion on angiography and yet no repeat revascularization was performed because of technical considerations or due to an untoward risk–benefit assessment. Only two patients underwent immediate redo operation within 1 h after the primary procedure due to haemodynamic and electrical instability without repeat ICA.

A repeat ICA was performed more often after on-pump CABG than after off-pump CABG (7.1 vs. 2.8%, P < 0.001). However, repeat revascularization was performed at equal rates in both on- and off-pump CABG (P = 0.38).

Logistic regression analysis was performed to assess predictors of the primary outcome. Only peak hs-cTnI levels within 48 h post-operatively (in quartiles), presence of new ECG or echocardiographic abnormalities, and electrical or haemodynamic instability were significantly associated with the primary outcome in our multivariate model (Supplementary material online, Section III, Table A1).

Association of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels with repeat revascularization

In our derivation cohort, an optimal cut-off value for peak hs-cTnI levels within the first 48 h post-operatively of >500× URL (corresponding absolute value 13 000 ng/L) was found to be significantly associated with repeat revascularization with a corresponding c-statistic of 0.92 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.87–0.96]. This cut-off had a sensitivity of 88.4%, a specificity of 93.4%, a PPV of 20.1%, and an NPV of 99.8% (accuracy 93.3%).

We re-performed the analyses separately for females and males and found that optimal cut-off values were 13 300 ng/L (>390× URL) in males and 9400 ng/L (588× URL) in females in the overall collective. Gender-specific cut-off values resulted in a similarly high performance (sensitivity 86%, specificity 93.4%, PPV 20.8%, NPV 99.7%, accuracy 93.7%). Further subgroup analyses are represented in the Supplementary material online (Section V, Tables A2a and A2b). Supplementary material, Section VII shows the association between hs-cTnI levels and angiographic vessel occlusion.

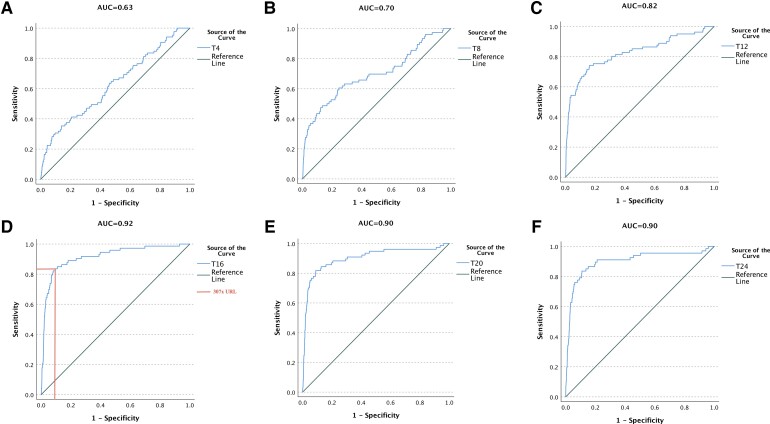

Utility of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I according to different time-points

We assessed the utility of hs-cTnI levels at predefined time-points (at 0–4, 4–8, 8–12, 12–16, 16–20, and 20–24 h post-operatively) and found that the area under the curve (AUC) for association with the primary outcome was very low at 4–8 h but increased gradually over time and reached its optimum at 12–16 h (Figure 4). Consequently, early elevations of hs-cTnI had limited yield while hs-cTnI level at 12–16 h was significantly associated with the primary outcome with an ROC suggested cut-off value of 8000 ng/L (AUC: 0.92, sensitivity 82.2%, specificity 92.0%, PPV 16.2%, NPV 99.6%, accuracy 91.7%). Using serial changes in hs-cTnI levels from baseline to predefined time-points (delta’s) did not result in an improved utility as the vast majority of baseline levels were within the normal range (details are represented in the Supplementary material online, Section XIV, Figure A10 and Table A8).

Figure 4.

Receiver-operating characteristics analysis of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I at predefined time-points post-operatively for the association with repeat revascularization after surgery. ROC, receiver-operating characteristics; AUC, area under the curve; T4, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels between 0 and 4 h post-operatively; T8, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels between 4 and 8 h post-operatively; T12, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels between 8 and 12 h post-operatively; T16, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels between 12 and 16 h post-operatively; T20, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels between 16 and 20 h post-operatively; T24, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels between 20 and 24 h post-operatively.

In contrast, combining the threshold of hs-cTnI >8000 ng/L at 12–16 h with ischaemic ECG changes (ST-segment elevations), echocardiographic abnormalities, or haemodynamic instability showed the best performance (sensitivity 90.4%, specificity 91.7%, NPV 99.8%, PPV 17.2%, accuracy 91.7%) with a corresponding increase in AUC of 4.0% (95% CI 0.8–7.2%; P = 0.014) when compared with the sole use of hs-cTnI levels at 12–16 h. While no significant AUC improvement was noticed when ECG, echocardiographic or haemodynamic abnormalities were combined with hs-cTnI elevations at earlier time-points (earlier than 12 h post-operatively) when compared with sole use of these criteria (ECG, echocardiographic, and haemodynamic instability) without troponin elevations.

Decision tree analysis

A decision tree analysis utilizing serial measurements of hs-cTnI in combination with additional criteria showed that hs-cTnI levels were not helpful for clinical decision-making in patients with ECG or echocardiographic abnormalities or haemodynamic instability. However, in stable patients without these abnormalities, early post-operative changes had a low yield while later elevations of hs-cTnI levels (at 12–16 h post-operatively) performed best. As represented in the Structured Graphical Abstract, our results indicate that either ECG or echocardiographic abnormalities or haemodynamic instability resulted in the largest association with the primary outcome in terms of the lowest permutation-based P-value. Patients with any of these indications will have an approximate likelihood for a repeated revascularization of ∼55% (Structured Graphical Abstract). If a patient does not show any of these indications, the maximum post-operative hs-cTnI value between 12 and 16 h might help to further separate patients that received an additional intervention.

Internal validity of the derived high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I thresholds

Estimated cut-off values in the derivation group were applied in the validation group; their performance measures (AUC, sensitivity, specificity, NPV, PPV, and accuracy) were calculated and compared between groups. No significant differences in these performance measures were found (AUC in the derivation group 0.91, 95% CI 0.84–0.98; AUC in the validation group 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.98; AUC difference 0.015, P = 0.74). Detailed comparisons are shown in the Supplementary material online, Appendix (Section VI, Table A3a and Figure A6).

To further test the internal validity of our thresholds, we performed a repeated random sampling stratified by the primary outcome and CPB use. Our analysis showed consistent results after 1000 iterations of random sampling and validation in the remaining ‘out-of-bag’ patients which confirms the internal validity of our results (Supplementary material online, Section VI, Table A3b).

Comparison with high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I thresholds in current recommendations

The criteria to perform an invasive workup suggested by the ESC position paper,1 the SCAI,3 and ARC24 for suspected post-operative myocardial infarction require ischaemic ECG or echocardiographic findings or haemodynamic or electrical instability or a cTn increase of >70× URL. When this threshold (70×URL) in addition to the above-mentioned non-troponin criteria was applied to our data on peak hs-cTnI within 48 h, it resulted in an NRI of 0.64 with an AUC of 0.67 (95% CI 0.64–0.69) when using angiographic vessel occlusion as the endpoint. In contrast, applying our ROC suggested cut-off of 500× URL (13 000 ng/L) besides other non-troponin criteria resulted in an NRI of 1.73 with an AUC improvement of 0.26 (P < 0.001). When the 70× URL threshold is applied to the hs-cTnI levels at 12–16 h post-operatively, then the NRI was 1.04 for new vessel occlusion and 1.23 for a Type 5 myocardial infarction (according to the UDMI) with AUC values of 0.76 and 0.77, respectively. Applying our suggested threshold of 307× URL to the hs-cTnI levels at 12–16 h resulted in an NRI of 1.56 for a new vessel occlusion and an NRI of 1.58 for a Type 5 myocardial infarction (according to the UDMI) with the corresponding AUC gain of 0.126 (95% CI 0.091–0.166) for new vessel occlusion and 0.128 (95% CI 0.092–0.160) for Type 5 myocardial infarction (P < 0.001 for both comparisons).

Major adverse cardiovascular events

A MACE was defined by myocardial infarction (according to the UDMI criteria), stroke, or in-hospital mortality. In the overall collective of 4684 patients, 30-day MACE occurred in 159 patients (3.4%). Logistic regression analysis showed that peak hs-cTnI level within 48h post-operatively of more than 13,000 ng/L was an independent predictor of 30-day MACE [odds ratio (OR) 21.9, 95% CI 15.5–30.8; P < 0.001, Table 3A and B). Post-operative hs-cTnI concentration elevations above the threshold of 13 000 ng/L resulted in an AUC of 0.78 (95% CI 0.74–0.83; P < 0.001) for predicting 30-day MACE. Applying gender-specific cut-off values resulted in similar findings, as shown in Table 3C. The relationship between peak post-operative hs-cTnI levels and 30-day MACE is represented in Table 3D and also in Supplementary material online, Figure A14 in Section XVII which shows that the higher the hs-cTnI levels got, the higher the MACE rates were.

Table 3.

Logistic regression analyses for predictors of 30-day major adverse cardiovascular event rate

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. Univariate logistic regression analysis | |||

| Post-operative hs-cTnI quartiles | <0.001 | ||

| 2nd quartile | 0.76 | 0.42–1.4 | 0.38 |

| 3rd quartile | 0.97 | 0.49–1.9 | 0.93 |

| 4th quartile | 17.7 | 11.9–26.4 | <0.001 |

| hs-cTnI >13 000 ng/L | 21.2 | 15.1–29.7 | <0.001 |

| Age | 1.03 | 1.01–1.05 | 0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.11 | 1.07–1.15 | <0.001 |

| Statin use | 0.57 | 0.41–0.81 | 0.001 |

| CPB use | 3.27 | 2.29–4.67 | <0.001 |

| Time on CPB | 1.01 | 1.009–1.02 | <0.001 |

| LVEF | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | 0.004 |

| History of AF | 2.0 | 1.1–3.7 | 0.02 |

| B. Multivariate logistic regression analysis for CV outcomes (females and males) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| hs-cTnI >13 000 ng/L | 21.9 | 15.5–30.8 | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.10 | 1.05–1.14 | 0.001 |

| Statin use | 0.65 | 0.46–0.93 | 0.02 |

| C. Multivariate analysis for 30-day MACE applying gender-specific cut-off values | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Females (>9400 ng/L) Males (>13 300 ng/L) |

20.1 | 14.3–28.2 | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II | 1.1 | 1.05–1.13 | <0.001 |

| Statin use | 0.66 | 0.46–0.93 | 0.007 |

| D. Logistic regression analysis of different hs-cTnI thresholds to predict 30-day MACE in the study cohort | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | Events/total | Adjusted odds ratioa | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

| <10×URL | 1/131 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| ≥10–<35× URL | 7/572 | 1.4 | 0.17–11.7 | 0.74 |

| ≥35–<70×URL | 17/1053 | 1.9 | 0.25–14.3 | 0.54 |

| ≥70–<500×URL | 40/2541 | 1.8 | 0.24–13.0 | 0.58 |

| ≥500×URL | 94/387 | 34.5 | 4.6–250.8 | <0.001 |

| E. Univariate logistic regression analysis of derived hs-cTnI thresholds to predict 30-day MACE in the external validation cohort from The Alfred Hospital | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

| hs-cTnI > 13 000 ng/L | 17.5 | 6.0–51.2 | <0.001 |

| Gender-specific cut-off values | 5.97 | 1.21–29.4 | 0.013 |

| F. Logistic regression analysis of different hs-cTnI thresholds to predict 30-day MACE in the external validation cohort from The Alfred Hospital | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Threshold | Events/total | Univariate OR (95% CI) | Univariate P-value | Adjusteda OR (95% CI) | P-value |

| <35×URLb | 3/184 (1.6) | 1.0 | — | 1.0 (reference) | — |

| ≥35–<70× URL | 3/186 (1.6) | 1.26 (0.30–5.35) | 0.75 | 1.35 (0.31–5.82) | 0.69 |

| ≥70–<500× URL | 10/240 (4.2) | 2.17 (0.61–7.80) | 0.22 | 2.43 (0.64–9.12) | 0.19 |

| ≥500× URL | 6/18 (33) | 26.2 (6.73–102) | <0.001 | 37.9 (8.85–163) | <0.001 |

hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; MACE, major adverse cardiovascular events; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; AF, atrial fibrillation; URL, upper reference limit.

Adjusted for EuroSCORE II and statin use.

Zero outcomes for the group of <10×URL (0/22), so group combined with 10–<35× URL as reference.

External validity

To assess external validity, we analysed data from The Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, Australia. Available data included 775 patients who underwent elective CABG surgery with serial measurements of hs-cTnI levels (utilizing a similar proprietary hs-cTnI assay, with a similar URL of 26 ng/L in general, 16 ng/L for females, and 34 ng/L for males). Of those 775 patients, only 10 patients had a Type 5 myocardial infarction, 22 patients had a post-operative stroke and 8 patients died within 30 days after surgery. The cut-off value of 13 000 ng/L was significantly associated with 30-day MACE in multivariate logistic regression analysis (OR 17.5, 95% CI 6.0–51.2; P < 0.001; Table 3E and F) with a similar AUC of 0.70 (95% CI 0.57–0.83). The same was applicable to gender-specific cut-off values (OR 5.97, 95% CI 1.21–29.4; P = 0.01; Table 3E).

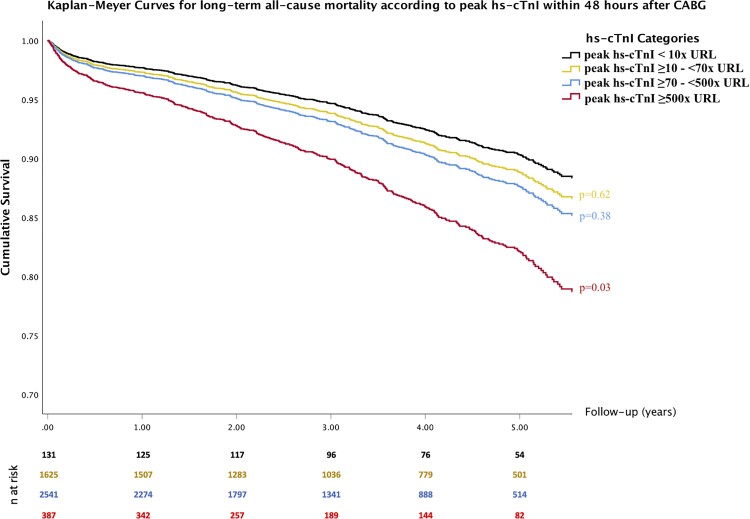

Long-term survival analyses

All-cause mortality occurred in 514 patients (11.0%) over a median follow-up of 3.1 (IQR 3.2) years. The Cox proportional hazards regression analysis showed post-operative hs-cTnI levels to be a significant predictor of all-cause mortality in the multivariate model (Table 4). Cardiac troponin I elevation above the threshold of 13 000 ng/L was also significantly associated with long-term all-cause mortality in the multivariate analysis [hazard ratio (HR) 1.54, 95% CI 1.16–2.03; P = 0.003], while lower elevations of hs-cTnI (10×to 70×URL) were not associated with long-term all-cause mortality (Figure 5 and Table 4C). Other significant predictors of long-term mortality included age, EuroSCORE II, left ventricular ejection fraction <40% at discharge, peripheral arterial disease, and diabetes (Table 4B). In a landmark analysis in patients who survived to discharge, similar findings were noticed (Supplementary material online, Section XI, Tables A6a and A6b). Survival analysis in patients who did not undergo repeat ICA is represented in Supplementary material online, Section XII in the appendix. Effects of post-operative management on long-term survival are shown in Supplementary material online, Section XIII in the Appendix (Table A7 and Figure A9). Further analyses regarding the completeness of revascularization and outcomes between on- versus off-pump CABG are represented in Supplementary material online, Section XVI.

Table 4.

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis for predicting long-term mortality:

| Variable | Control | At risk | Hazards ratio | 95% confidence interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. Univariate analysis | |||||

| Age | 1.08 | 1.06–1.09 | <0.001 | ||

| EuroSCORE II quartiles | <0.001 | ||||

| 2nd quartile | 32/1161 | 79/1167 | 2.5 | 1.7–3.8 | <0.001 |

| 3rd quartile | 134/1180 | 4.6 | 3.1–6.7 | <0.001 | |

| 4th quartile | 269/1176 | 10.2 | 7.1–14.8 | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 269/2945 | 245/1739 | 1.6 | 1.4–1.9 | <0.001 |

| PAD | 401/4103 | 113/581 | 2.2 | 1.8–2.7 | <0.001 |

| Baseline LVEF <40% | 416/4205 | 98/479 | 2.3 | 1.9–2.9 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 466/4454 | 48/230 | 2.9 | 2.2–3.9 | <0.001 |

| Use of CPB | 392/3992 | 122/692 | 1.86 | 1.52–2.28 | 0.001 |

| Post-operative hs-cTnI quartiles | <0.001 | ||||

| 2nd quartile | 118/1180 | 113/1167 | 1.10 | 0.85–1.43 | 0.46 |

| 3rd quartile | 133/1222 | 1.34 | 1.05–1.72 | 0.02 | |

| 4th quartile | 147/1115 | 1.64 | 1.29–2.09 | <0.001 | |

| B. Multivariate analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Hazards ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P-value |

| Age | 1.05 | 1.03–1.06 | <0.001 |

| EuroSCORE II quartiles | <0.001 | ||

| 2nd quartile | 1.70 | 1.11–2.58 | 0.01 |

| 3rd quartile | 2.34 | 1.54–3.55 | <0.001 |

| 4th quartile | 3.90 | 2.53–6.00 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 1.36 | 1.14–1.63 | 0.001 |

| PAD | 1.44 | 1.15–1.80 | 0.001 |

| LVEF <40% at discharge | 2.1 | 1.6–2.8 | <0.001 |

| Post-operative hs-cTnI quartiles | 0.045 | ||

| 2nd quartile | 1.09 | 0.84–1.40 | 0.53 |

| 3rd quartile | 1.21 | 0.94–1.56 | 0.13 |

| 4th quartile | 1.39 | 1.09–1.77 | 0.008 |

| C. Cox regression analysis considering different hs-cTnI thresholds | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate analysis including dichotomous thresholds | |||||

| Post-operative hs-cTnI thresholds | Control | hs-cTnI elevation | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| >10× URL | 12/131 | 502/4553 | 1.55 | 0.85–2.82 | 0.12 |

| >70×URL | 179/1756 | 335/2928 | 1.33 | 1.11–1.60 | 0.002 |

| >500× URL | 451/4297 | 63/387 | 1.72 | 1.30–2.30 | <0.001 |

| Multivariate analysis: adjusted for age, EuroSCORE II, CPB use, diabetes, PAD, and LVEF at discharge | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Post-operative hs-cTnI thresholds | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| >10× URL | 0.84 | 0.46–1.53 | 0.57 |

| >70× URL | 1.15 | 0.95–1.38 | 0.15 |

| >500× URL | 1.47 | 1.10–1.95 | 0.008 |

| Analysis of hs-cTnI corridors | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Post-operative hs-cTnI thresholds | Events/total | HR | 95% CI | P-value |

| <10×URL | 12/131 | 1.0 | Reference | |

| ≥10–35× URL | 55/572 | 1.15 | 0.60–2.19 | 0.68 |

| ≥35–70× URL | 112/1053 | 1.41 | 0.76–2.62 | 0.28 |

| ≥70–500× URL | 272/2541 | 1.60 | 0.88–2.92 | 0.13 |

| ≥500× URL | 63/387 | 2.46 | 1.26–4.66 | 0.006 |

PAD, peripheral arterial disease; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; hs-cTnI, high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I; URL, the 99th percentile upper reference limit.

Figure 5.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves according to peak high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I levels within 48 h after surgery. Kaplan–Meier curves from in multivariable Cox regression analysis (P-values were adjusted for: age, EuroSCORE II, diabetes, peripheral arterial disease, and left ventricular ejection fraction at discharge).

Discussion

In our study, we showed (i) the release kinetics of a contemporary hs-cTnI assay in patients following CABG surgery, (ii) an optimal cut-off value of > 500× URL (13 000 ng/L) for peak hs-cTnI levels to be significantly associated with repeat revascularization during the first 48h following CABG surgery with internal validation through random repeated sampling with 1000 iterations; (iii) a decision tree analysis incorporating clinical decision factors (ECG, echocardiographic, haemodynamic) and hs-cTnI levels at different time intervals demonstrating that hs-cTnI levels determined 12–16 h post-operatively with an elevation of >307×URL in the absence of prior echocardiographic, hemodynamic, or ECG changes yielded the best association with repeat revascularization, thus supporting the decision for ICA. Conversely, hs-cTnI levels in patients with positive clinical factors or hs-cTnI levels collected earlier than 12 h exhibited only a very limited yield; the suggested hs-cTnI cut-off at 12–16 h was confirmed by exhibiting the highest AUC when ROC curves at different time-points were compared.

Conceptually, it is of importance to differentiate between the employment of cTn to guide clinical decision-making or to define post-operative myocardial infarction. While the former is done prospectively and requires timely availability of relevant information, the latter is done retrospectively and uses criteria which are not available to the clinician. Thus, the UDMI2 uses peak cTn within 48 h after surgery as well as, among other criteria, angiographic coronary vessel occlusion, which are both not meant to be used for clinical decision-making. In order to aid the decision-making process, the ESC issued a position paper1 which suggests an algorithm integrating cTn elevation, ECG, echocardiographic, and haemodynamic criteria. The UDMI definition uses a threshold of 10×URL, while the threshold is 70×URL in the ESC position paper,1 which is in alignment with the Expert Consensus Document from SCAI3 and the ARC-2 document.4 Both of these thresholds were arbitrarily chosen but the decision was based on the best available evidence on the association between cTn levels and mortality or evidence of myocardial injury. In contrast, the aim of our study was to investigate how to best employ hs-cTnI for the decision whether or not to perform ICA as part of the workup. To this end, we used the clinical decision to repeat revascularization as the primary outcome, which does not address issues like Type 2 myocardial infarction or prognostic elevations of cTn.

In an attempt to further enhance the utility of post-operative hs-cTnI, we performed numerous analyses considering the time course of hs-cTnI determination as well as the integration of clinical factors currently recommended for decision-making. These analyses revealed that serial changes in hs-cTnI levels failed to enhance utility early after surgery, potentially because a certain extent of myocardial injury accompanied by dynamic hs-cTnI changes occurs in all patients as a consequence of post-operative non-graft-related myocardial injury. However, in line with these considerations, our analyses showed that hs-cTnI kinetics in patients with an uneventful post-operative course and in those requiring further workup were very similar early after CABG and curves began to separate after 8–12 h post-operatively. Consequently, hs-cTnI levels >307×URL determined 12–16 h after surgery in patients without prior clinical signs of ischaemia yielded the best performance compared with earlier hs-cTnI levels. Substituting the recommended thresholds of current guidelines with this threshold (307× URL) led to markedly higher AUCs and net reclassification indices. However, we acknowledge that thresholds recommended by current guidelines address different primary outcomes relying on the prognostic value of cTn elevations and are not developed to predict revascularization. Still, the idea that markedly higher cut-off values for hs-cTn assays are required to identify patients with post-operative myocardial ischaemia/infarction has been previously described in a small study by Jorgensen et al.9 This concept applies even to standard cTn assays as represented in earlier studies utilizing cardiac magnetic resonance imaging to identify patients with perioperative myocardial infarction.10,11

With regard to off-pump CABG, cTn thresholds were expectedly lower than those for on-pump CABG, since the use of CPB leads to more cTn release.12 Interestingly, absolute post-operative values of hs-cTnI did not significantly differ with regard to gender following off-pump CABG. In contrast, lower cut-off values were found for women compared with men after on-pump CABG. The fact that cardiac biomarker release differs according to gender after on-pump cardiac surgery has been previously reported for standard cTn assays.13,14 There is an accumulating body of evidence that gender-specific cut-off values have better performance in patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome.14,15 However, the effect of gender-specific thresholds on reducing subsequent cardiac events and mortality is still a matter of debate.16 We do not have a clear explanation for this finding, which to our knowledge so far has not been reported, but one could speculate that off-pump CABG might lead to a similar amount of myocardial injury and cTn release in both genders, and the degree of cTn release due to graft occlusion is comparable between genders. However, the neurohormonal and inflammatory response during CPB procedures with resulting activation of prothrombotic mechanisms might be essentially different between women and men.13 More data on off-pump CABG are required to shed more light on this issue.

Additionally, we found elevated hs-cTnI levels to be associated with increased cardiovascular events and in-hospital as well as long-term mortality. The prognostic relevance of cTn elevations after cardiac surgery has been described previously.17,18 Elevated hs-cTnI levels above the peak threshold of 13 000 ng/L (500× URL) predicted worse short-term cardiovascular outcomes, which was also validated in an external cohort from The Alfred Hospital in Melbourne, Australia. Moreover, elevated hs-cTnI levels >13 000 ng/L predicted increased all-cause mortality over long-term follow-up, especially in patients who did not receive ICA, emphasizing the clinical relevance of such cTn elevations.

Finally, it has again to be emphasized that our suggested cut-off values are primarily helpful for ruling out the need for ICA after surgery. However, due to low positive predictive values, it cannot be recommended to perform ICA solely based on cTn elevations. Instead, our data corroborate that an integrative assessment of additional clinical, ECG, and echocardiographic findings will still be crucial in clinical decision-making.

Limitations

We acknowledge the following limitations: due to the retrospective nature of this single-centre study, results might be biased even after adjustments in multivariate regression analyses. Furthermore, the relatively low event rates might have resulted in reduced power with increased risk for a Type II error, especially when data were split into a test and a validation cohort. The primary outcome of our study was a clinical decision to repeat revascularization, which is at risk to be influenced by physician preferences. Furthermore, the clinical nature of the primary outcome in our study ignored events like coronary spasm or supply–demand mismatch and focused on ICA findings to aid clinical decision-making post-operatively. Moreover, despite the fact that patients underwent repeat ICA according to a predefined internal SOP of our hospital, selection bias is still possible even after randomly splitting the collective in a derivation and validation cohort, as decisions to perform acute PCI, redo surgery, or for a conservative management were made on an individual basis by the heart team. That is why we performed a repeated random sampling with 1000 iterations that confirmed our results. Ideally, ICA should have been performed in all patients to diagnose even less obvious native or graft vessel occlusions. However, performing ICA in all patients after surgery is not practical and not justified in patients with completely uneventful post-operative course. Furthermore, 41% of patients underwent ICA based only on hs-cTnI elevations without any clinical indication (like ECG, echocardiographic, or haemodynamic instability). Levels of hs-cTnI in these patients were comparable to patients who underwent repeat ICA without these clinical criteria, which reflects the consistency of post-operative management and ICA indication in our study. Moreover, only 41.6% of patients with repeat ICA had a new vessel occlusion, supporting that undetected vessel occlusion occurred only in a minor fraction of patients. In fact, 31% of the 161 patients who received ICA did not have any culprit lesion, which reflects the somehow liberate indication for repeat ICA in our study. Furthermore, patients who did not receive repeat ICA had a preferable long-term outcome, which again corroborates that the risk of missing less obvious coronary occlusions was minimal. Another limitation is that our data are based on the hs-cTnI assay from one proprietary platform, and despite internal and external validation of derived cut-off values, dynamics and performance of derived cut-off values might probably differ when applied to other assays. Nonetheless, the principle that higher cut-off values than those suggested by current guidelines for diagnostic and prognostic significance would still be a concept that is substantiated. In spite of the similar performance of our derived thresholds in predicting short-term MACE events in an external cohort, number of events was relatively small and did not allow validation of our thresholds for revascularization so that our results are just hypothesis-generating and need further validation. Furthermore, we did not consider all factors that might have an effect on perioperative cTn release profile like warm vs. cold cardioplegia, type of anaesthesia, experience of operators, etc. However, a consistent profile was implemented for most of the patients at our hospital according to SOPs, which resulted in the minimization of the effects of these factors. In addition, we collected data on hs-cTnI only up to 48 h after surgery and our data thus do not inform management of myocardial ischaemia occurring at later stages after surgery. Combined procedures (like CABG with valvular or ablation procedures) were excluded from the present study in order to mitigate heterogeneity in the final study population. However, the diagnostic and prognostic value of hs-cTnI levels may differ significantly between isolated CABG and combined procedures. Importantly, because this was a retrospective study, it can give no definitive answer on whether the workup algorithm suggested herein provides superior clinical outcomes compared with algorithms utilizing lower hs-cTnI thresholds. This could only be addressed by a prospective randomized trial. Yet, our analyses along with the observed densely monitored hs-cTnI kinetics clearly demonstrate a large overlap of hs-cTnI levels between patient groups particularly in the first hours after surgery and thus support the hypothesis of a greater usefulness of hs-cTnI levels at later time-points with higher thresholds than previously found in the literature. These findings need further confirmation in prospective studies.

Conclusion

In aggregate, our study is the first to describe post-operative kinetics of hs-cTnI in a large population of patients undergoing isolated CABG surgery with internal and external validation of major findings. Our results suggest that optimal cut-off values to trigger repeat ICA and decision for repeat revascularization are considerably higher than those recommended by current algorithms, achieve better patient reclassification, and robustly predict short- and long-term cardiovascular outcomes. Analyses of hs-cTnI levels collected 12–16 h post-operatively achieved the best utility, whereas prior to this time decision-making should not be based upon hs-cTnI levels but on currently recommended ECG, echocardiographic, and hemodynamic criteria. Indeed, an approach incorporating hs-cTnI levels elevation at 12–16 h with these criteria conferred the best performance.

Author contributions

H.O.: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; the acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; drafting the work; final approval of the version to be published; agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. E.G.: substantial contributions to the acquisition of data for the work. M.A.D., A.R., J.T.N., D.W., W.S., K.H.-M., T.K.R.: substantial contributions to the analysis, and interpretation of data for the work; critically revising the work for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. P.M.: provided support with external validation of hs-cTnI thresholds. B.R., M.P., A.Z.: provided statistical support. J.G. and V.R.: substantial contributions to the conception and design of the work; critically revising the work for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published; agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Heart Journal online.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Hazem Omran, Clinic for General and Interventional Cardiology/Angiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Marcus A Deutsch, Clinic for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Elena Groezinger, Clinic for General and Interventional Cardiology/Angiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Armin Zittermann, Clinic for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

André Renner, Clinic for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Johannes T Neumann, Clinic for Cardiology, University Heart and Vascular Center Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany.

Dirk Westermann, Clinic for Cardiology, University Heart and Vascular Center Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany.

Paul Myles, Department of Anaesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Alfred Hospital and Monash University, Melbourne, Australia.

Burim Ramosaj, Faculty of Statistics, Technical University of Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany.

Markus Pauly, Faculty of Statistics, Technical University of Dortmund, Dortmund, Germany.

Werner Scholtz, Clinic for General and Interventional Cardiology/Angiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Kavous Hakim-Meibodi, Clinic for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Tanja K Rudolph, Clinic for General and Interventional Cardiology/Angiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Jan Gummert, Clinic for Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Volker Rudolph, Clinic for General and Interventional Cardiology/Angiology, Herz- und Diabeteszentrum NRW, Ruhr-Universität Bochum, Georgstr. 11, 32545 Bad Oeynhausen, Germany.

Funding

The study was supported by a research grant from Abbott Medical Deutschland GmbH.

Conflict of interest

H.O., M.A.D., E.G., A.Z., B.R., M.P., A.R., W.S., K.H.-M., J.G., V.R. have no conflicts of interest. J.T.N. is a recipient of a research fellowship by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (NE 2165/1-1); D.W. has received speaker honoraria for AstraZeneca, Bayer, Berlin-Chemie, Novartis, and Medtronic. P.M. is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Practitioner Fellowship (ID 1135937). T.K.R. has received speakers honoraria from Boston Scientific and Abbott.

References

- 1. Thielmann M, Sharma V, Al-Attar N, Bulluck H, Bisleri G, Bunge JJH, et al. ESC Joint Working Groups on Cardiovascular Surgery and the Cellular Biology of the Heart Position Paper: perioperative myocardial injury and infarction in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2392–2411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018). Eur Heart J 2019;40:237–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Moussa ID, Klein LW, Shah B, Mehran R, Mack MJ, Brilakis ES, et al. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: an expert consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI). J Am Coll Cardiol 2013;62:1563–1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Garcia-Garcia HM, McFadden EP, Farb A, Mehran R, Stone GW, Spertus J, et al. Standardized end point definitions for coronary intervention trials: the academic research consortium-2 consensus document. Circulation 2018;137:2635–2650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rautaharju PM, Surawicz B, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Childers R, Deal BJ, et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part V: electrocardiogram changes associated with cardiac chamber hypertrophy: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:982–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Surawicz B, Childers R, Deal BJ, Gettes LS, Bailey JJ, Gorgels A, et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part III: intraventricular conduction disturbances: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:976–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wagner GS, Macfarlane P, Wellens H, Josephson M, Gorgels A, Mirvis DM, et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram: part VI: acute ischemia/infarction: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society. Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:1003–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Leening MJ, Vedder MM, Witteman JC, Pencina MJ, Steyerberg EW. Net reclassification improvement: computation, interpretation, and controversies: a literature review and clinician’s guide. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:122–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jorgensen PH, Nybo M, Jensen MK, Mortensen PE, Poulsen TS, Diederichsen AC, et al. Optimal cut-off value for cardiac troponin I in ruling out Type 5 myocardial infarction. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2014;18:544–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pegg TJ, Maunsell Z, Karamitsos TD, Taylor RP, James T, Francis JM, et al. Utility of cardiac biomarkers for the diagnosis of type V myocardial infarction after coronary artery bypass grafting: insights from serial cardiac MRI. Heart 2011;97:810–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hueb W, Gersh BJ, Alves da Costa LM, Costa Oikawa FT, Vieira de Melo RM, Rezende PC, et al. Accuracy of myocardial biomarkers in the diagnosis of myocardial infarction after revascularization as assessed by cardiac resonance: the medicine, angioplasty, surgery study V (MASS-V) trial. Ann Thorac Surg 2016;101:2202–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Khan NE, De Souza A, Mister R, Flather M, Clague J, Davies S, et al. A randomized comparison of off-pump and on-pump multivessel coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med 2004;350:21–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwarzenberger JC, Sun LS, Pesce MA, Heyer EJ, Delphin E, Almeida GM, et al. Sex-based differences in serum cardiac troponin I, a specific marker for myocardial injury, after cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med 2003;31:689–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sbarouni E, Georgiadou P, Voudris V. Gender-specific differences in biomarkers responses to acute coronary syndromes and revascularization procedures. Biomarkers 2011;16:457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Romiti GF, Cangemi R, Toriello F, Ruscio E, Sciomer S, Moscucci F, et al. Sex-specific cut-offs for high-sensitivity cardiac troponin: is less more? Cardiovasc Ther 2019;2019:9546931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shah ASV, Anand A, Strachan FE, Ferry AV, Lee KK, Chapman AR, et al. High-sensitivity troponin in the evaluation of patients with suspected acute coronary syndrome: a stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018;392:919–928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gahl B, Gober V, Odutayo A, Tevaearai Stahel HT, da Costa BR, Jakob SM, et al. Prognostic value of early postoperative troponin T in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting. J Am Heart Assoc 2018;7:e007743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Domanski MJ, Mahaffey K, Hasselblad V, Brener SJ, Smith PK, Hillis G, et al. Association of myocardial enzyme elevation and survival following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. JAMA 2011;305:585–591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.