Abstract

Ticks are an important group of arthropod vectors. Ticks pose a profound risk to public health by transmitting many types of microorganisms that are human and animal pathogens. With the development of next-generation sequencing (NGS) technology and viral metagenomics, numerous novel viruses have been discovered in ticks and tick-related hosts. To fully understand the virus spectrum in ticks in the Zhoushan Archipelago of Zhejiang province in China, ticks were collected from Qushan Island, Zhoushan Island, and Daishan Island in the Zhoushan Archipelago in June 2016. NGS performed to investigate the diversity of tick-associated viruses identified 21 viral sequences. Twelve were pathogenic to humans and animals. Trough verification by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) revealed the existence of three tick-associated viruses with extensive homology with Dabieshan, MG22, and Odaw virus. Other NGS-detected sequences that could not be amplified by PCR were highly homologous (92–100%) with known pathogenic viruses that included hepatitis B virus, papillomavirus, and human mastadenovirus C. This is the first study to systematically apply high throughput sequencing technology to explore the spectrum of viruses carried by ticks in the Zhoushan Archipelago. The findings are fundamental knowledge of the diversity of tick-associated viruses in this region and will inform strategies to monitor and prevent the spread of tick-borne diseases.

Keywords: next-generation sequencing, tick, tick-associated viruses, virome analysis

Ticks are the second largest group of arthropods after mosquitoes [3]. They have a long life cycle, are widely distributed, and have multiple hosts [19]. Ticks can carry various pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, protozoans, and parasites [4, 7]. By feeding on vertebrate hosts, ticks can transmit zoonotic microorganisms. Tick-borne viruses are the most prominent pathogens and can pose serious health threats to people and animals [3]. In addition to well-known viruses, such as Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus (CCHFV) [9, 12] and tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) [10, 21], several novel tick-borne viruses have been discovered and identified in recent years. In 2010, a novel tick-borne virus, severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus (SFTSV), was discovered in Henan province, China [23]. SFTSV belongs to the family Phenuiviridae and genus Bandavirus. From 2010 to 2016, more than 10,000 SFTSV-infected cases were reported in 23 provinces in China, with an average mortality rate of 5.3% [24]. Another pathogenic bandavirus, Heartland virus (HRTV), which shares a genome sequence similar to that of SFTSV, was identified in the United States [16]. The increasing number of cases of tick-borne viruses indicate their fundamental adverse impact on public health.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is a high throughput and highly efficient method. NGS was first used in ticks to investigate the diversity of bacterial composition in 2011 [1]. In the last five years, the NGS technology has been increasingly applied to the discovery of tick-borne viruses. Several novel viruses have been identified worldwide, including America, Africa, Asia, and Australia [2, 17, 18]. In particular, Zhang et al. collected 70 species of arthropods from various locations in China and used NGS to detect an enormous number of negative-sense RNA viruses, including 112 novel viruses [13]. NGS has accelerated the discovery of pathogenic viruses and has enhanced the understanding of the composition and evolution of tick-borne viruses.

The Zhoushan Archipelago is located on the southeast coast of China. The warm and humid climate is suitable for diverse tick-borne species, which makes Zhoushan a natural epidemic focus. Tick-borne SFTSV [8] and spotted fever group rickettsia [20] have been previously reported in this area using traditional enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and PCR methods. The application of NGS in combination with viral metagenomics will facilitate our understanding of the diversity and distribution of tick-associated viruses in this area. In addition, the findings will inform monitoring and prevention strategies for pathogenic viruses.

In this study, we collected ticks from the Zhoushan Archipelago for NGS and analyzed their evolutionary relationships. Based on these results, three tick-associated viruses were characterized and verified. Numerous suspected virus reads will require further verification.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sample collection and virus identification

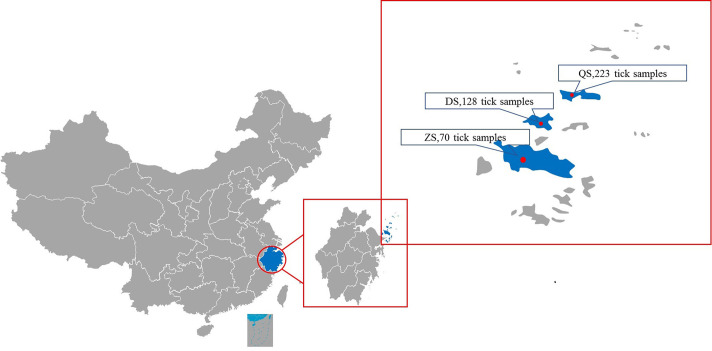

All ticks were collected in June 2016 from the Zhoushan (ZS), Daishan (DS), and Qushan (QS) islands the Zhoushan Archipelago. The detailed collection sites were Xianggangshan (ZS), Changaogangdun (DS), and Dashangangdun (QS) (Fig. 1). Questing ticks were collected using the dragging method. Infesting ticks were collected directly from domestic animals, mainly cattle and sheep. When collecting the latter, whole blood was also collected from these animals for testing. Ticks and whole blood were placed into 1.5 ml tubes, labeled according to their collection location, and then shipped to the laboratory at 4°C. All the samples were stored at −80°C in the laboratory until nucleic acid extraction. The tick types were identified by morphological observation [14] and nested PCR assays of tick 16S ribosomal RNA [5].

Fig. 1.

Geographic location and sampling number of the sampling sites. ZS denotes Xianggangshan in Zhoushan island, DS denotes Changaogangdun in Daishan, and QS denotes Dashangangdun in Qushan.

Nucleic acid extraction

Nucleic acid extraction methods have been previously reported [16]. For NGS, 20 ticks from each location were pooled. The remaining 184 ticks were ground separately for further virus identification and isolation. All ticks were flushed with phosphate buffered solution (PBS) before extraction to remove pathogens on their surface. One ml of PBS was added to the pooled ticks, which were ground using a glass pestle. The resulting homogenate was centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. The sediment was used to identify the tick type, while the supernatant was filtered through 0.22 μm Pellicon II filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) to remove cell debris and bacteria. Two hundred microliters of the filtered supernatant was used to extract nucleic acids using the MiniBEST viral RNA/DNA extraction kit (TaKaRa Bio, Dalian, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. The remaining filtered supernatant was stored at −80°C. The sediment of ticks and whole blood of host animals were lysed and nucleic acids were extracted using a MiniBEST viral RNA/DNA extraction kit (TaKaRa Bio, Dalian, China). Finally, 30 μl of the extracted RNA mixture was obtained for cDNA library preparation or reverse transcription and 30 μl of the extracted DNA was obtained for identification of tick species.

cDNA library for NGS

For NGS, total RNA was mixed with 2 μl of hexametric random primer (50 μM) with different tag sequences at the 5′ end. The mixture was denatured at 65°C for 5 min and placed in an ice-bath for 1 min. The mixture was incubated with the pre-mix cDNA synthesis solution containing 3 μl dNTP (10 μM), 1 μl RNase inhibitor, 10 μl 5× RT buffer, and 1 μl reverse transcriptase at 42°C for 60 min to obtain first-strand cDNA. The cDNA was heated at 85°C for 10 min after reverse transcription to inactivate the reverse transcriptase. For double-strand (ds) cDNA synthesis, the first-strand cDNA was incubated with 1 μl dNTP (10 μM), 2 μl of 10× Klenow buffer, and 1 μl Klenow fragment (TaKaRa Bio, Kusatsu, Japan) at 37°C for 60 min, followed by inactivation at 75°C for 10 min. To meet the NGS requirements, the TaKaRa Bio Extaq amplification system was used to produce sufficient viral cDNA. A total of 25 μl amplification system including 1 μl of template (ds cDNA mixture), 1 μl of 20 mM tag primers (without hexamers), 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 4 μl of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 1 μl of Ex Taq Polymerase (1 U), and distilled deionized water (ddH2O) was denatured at 94°C for 3 min; 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 54°C for 30 sec, and 54°C for 30 sec; followed by incubation at 72°C for 5 min. The final amplified products were purified according to the manufacturer’s protocol using the TaKaRa Bio MiniBEST DNA fragment purification kit (TaKaRa Bio).

cDNA preparation for virus screening

Fifteen microliters of RNA template obtained as described in section 2.2 was mixed with 1 μl Oligo dT primer, 3 μl Random 6 mers, and 35 μl Rnase free H2O. The mixture was heated at 65°C for 5 min to denature the RNA. The total 50 μl volume of the reverse transcription system included 25 μl denaturation solution, 10 μl of 5× primerscript buffer, 2 μl Primerscript Reverse Transcriptase, 1 μl RNase Inhibitor Buffer, and 25 μl RNase free dH2O. The mixture was heated at 30°C for 10 min, 42°C for 60 min, and 72°C for 5 min (PrimeScript™ 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit; TaKaRa Bio). Finally, the acquired cDNA template was stored at −20°C for further PCR.

NGS and data analysis

The cDNA library was sequenced in a single lane (paired-end, 151 bp read length) on a NextSeq 500 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Raw sequencing data were processed to delete reads with low quality scores (<20) and remove adapters, and then was filtered to short reads. The clean data were assembled de novo using MEGAHIT v1.1.2 to obtain the scaffold sequence. The scaffold data were aligned against the non-redundant and viral reference GenBank databases using BLASTx and BLASTn. An E value ≤10e−5 was used to determine homologous sequences.

PCR for virus screening

To identify the tick species and validate the accuracy of metagenomic sequencing results, Primer 5.0 and DNASTAR Lasergene software were used to design primers based on the sequence assembly. All primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1. The PCR for DNA or cDNA system containing 1 μl of cDNA/DNA, 2 μl of 20 mM designed primers, 2.5 μl of 10× PCR buffer, 4 μl of 2.5 mM dNTPs, 0.5 μl of ExTaq Polymerase (1 U), and 15 μl of ddH2O was denatured at 94°C for 3 min, 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 54°C for 30 sec, and 54°C for 30 sec, followed by 72°C for 5 min. The PCR products were visualized using 1.2% agarose gel electrophoresis. Positive PCR products, which presented a single bright band, were sequenced using an ABI 3730 DNA analyzer (Invitrogen, Beijing, China).

Phylogenetic analysis

Sequences that shared high similarities with viral sequences obtained by NGS were searched using a basic local alignment search tool (BLASTn) and downloaded. Multiple sequence alignment was performed using Clustal W. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using the neighbor-joining method with 1,000 bootstrap replications based on the software Mega7.

RESULTS

Sampling and identification

A total of 421 ticks were collected in 2016. These included 70 ticks from Zhoushan, 128 ticks from Daishan, and 223 ticks from Qushan (Fig. 1). Among the 421 ticks collected, 244 tick species were identified by morphological and molecular identification. Two species of ticks were distributed in the Zhoushan Archipelago. Haemaphysalis longicornis was the dominant species, accounting for 71.7% (175/244), and was distributed across all three sampling areas. Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides was another species that was only found in the Daishan and Zhoushan areas (Table 1).

Table 1. Summary details of tick species in the three sites.

| Site | Ticks for NGS | Ticks for virus screening | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. longicornis | R. haemaphysaloides | H. longicornis | R. haemaphysaloides | H. longicornis | R. haemaphysaloides | |

| Zhoushan | 11/20 | 9/20 | 29/48 | 19/48 | 40/68 | 28/68 |

| Daishan | 12/20 | 8/20 | 41/74 | 33/74 | 53/94 | 41/94 |

| Qushan | 20/20 | 0/20 | 62/62 | 0/62 | 82/82 | 0/82 |

H. longicornis, Haemaphysalis longicornis; R. haemaphysaloides, Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides.

NGS metagenomic analysis

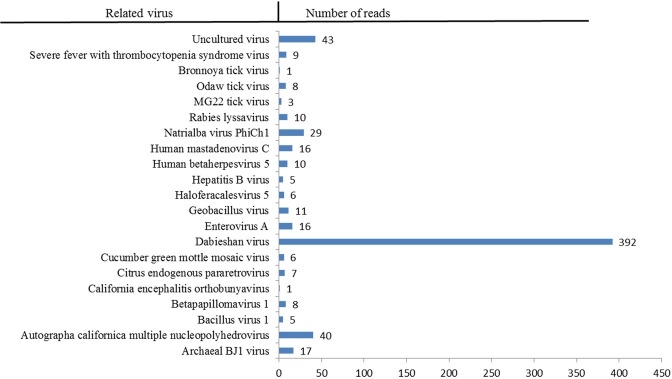

Using NGS, a total of 7.22 GB raw data were obtained from the Illumina Nextseq 500 platform. After quality control and tick sequence removal, the remaining 31,572,902 reads were used for further study. Among these, the percentage of reads with a quality score ≥20Q ranged from 95.93% to 98.26%, whereas the quality score ≥30Q ranged from 89.84% to 95.19%. The average read length was 151 bp. The majority of these reads (up to 539,056 reads) were classified as bacteria, 3,415 reads belonged to fungi, and the remaining 723 reads were classified as virus sequences. Based on BLASTn (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov), the reads were classified into 21 virus types. The number of related reads assigned to each virus is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Overview of viral reads obtained by Next-generation sequencing.

Screening for virus

A total of 723 virus-related reads were obtained. They were sorted into bacteriophages, plant viruses, arthropod viruses, and vertebrate viruses based on the host species. Among them, three species of bacteriophages belonged to the families Myoviridae and Siphoviridae, only one arthropod virus was related to the family Baculoviridae, and two types of plant viruses belonged to the families Virgaviridae and Retroviridae. Remarkably, most reads were assigned to vertebrate-associated viruses in nine different families: Papillomaviridae, Peribunyaviridae, Nairoviridae, Phenuiviridae, Picornaviridae, Hepadnaviridae, Herpesviridae, Adenoviridae, and Rhabdoviridae (Table 2). Vertebrate-related viruses, especially zoonotic viruses, which can cause severe disease and substantial economic loss, are the focus of intensive research. Most of the reads were from the Dabieshan virus, which accounted for 54.2% of the sequencing reads (392/723). Notably, some reads shared some identity with MG22 and Odaw viruses belonging to the family Phenuiviridae, which are important tick-borne viruses. In addition, we identified some reads with up to 99% identify with human pathogenic viruses. These included hepatitis B virus, human mastadenovirus C, and SFTSV. Although we obtained reads potentially derived from these pathogenic viruses from ticks, we could not verify the existence of these pathogens by PCR. The PCR primers used are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

Table 2. Potential pathogenic viruses detected by Next-generation sequencing.

| NGS-detected viral sequence (Accession number) | Family | Contig No. | Length (bp) | Identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Papillomavirus (FM955837.2) | Papillomaviridae | 8 | 300 | 100% |

| California Encephalitis Orthobunyavirus (HQ541823.1) | Peribunyaviridae | 1 | 100 | 92% |

| Dabieshan Virus (KM817666.1) | Phenuiviridae | 392 | 1,421 | 100% |

| SFTS virus (KY511129.1) | Phenuiviridae | 9 | 100 | 100% |

| MG22 Tick virus (KY979165.1) | Phenuiviridae | 3 | 100 | 79% |

| Odaw virus (LC193452.1) | Phenuiviridae | 8 | 465 | 77% |

| Bronnoya virus (MF141062.1) | Nairoviridae | 1 | 131 | 72% |

| Enterovirus A (KJ632498.1) | Picornaviridae | 16 | 305 | 100% |

| Hepatitis B virus (KF166441.1) | Hepadnaviridae | 5 | 100 | 99% |

| Human Betaherpesvirus (MF783093.1) | Herpesviridae | 10 | 100 | 100% |

| Human Mastadenovirus C (KM190941.1) | Adenoviridae | 16 | 100 | 100% |

| Rabies Lyssavirus (JN234411.1) | Rhabdoviridae | 10 | 400 | 100% |

NGS-detected viral sequence indicates the GenBank-existing virus species closest to the viruses detected.

Dabieshan virus

According to NGS, there were 392 reads related to Dabieshan virus in the pooled samples. These were 97% homologous with the Dabieshan virus sequences in GenBank. Zhang et al. first identified this virus using NGS in Zhejiang in 2015 [13]. We designed specific primers (Supplementary Table 1) targeting the sequence obtained by NGS to verify and identify Dabieshan virus in ticks. We amplified the genome fragment of the Dabieshan virus in tick samples, but it was not detected in the whole blood of local animals. As shown in Table 3, this virus was distributed on Daishan Island (61/74) and Zhoushan Island (20/48) but was not detected in ticks on Qushan Island (0/62). The overall positivity rate of Dabieshan virus was 44.0% (81/184). R. haemaphysaloides and H. longicornis are hosts of the Dabieshan virus.

Table 3. Location and species distribution of detected viruses.

| Viruses | Daishan Island | Zhoushan Island | Qushan Island | Positive rate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H. longicornis | R. haemaphysaloides | H. longicornis | R. haemaphysaloides | H. longicornis | R. haemaphysaloides | ||

| Dabieshan | 49 | 12 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 44.0% (81/184) |

| DSP4 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.6% (3/184) |

| ZSP7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.5% (1/184) |

H. longicornis, Haemaphysalis longicornis; R. haemaphysaloides, Rhipicephalus haemaphysaloides.

DSP4 virus

The DSP4 virus was a novel virus discovered in this study, with eight annotated reads in the pool. A BLAST search of the NCBI nucleic acid database showed that this sequence derived from the eight reads with 77% homology with the Odaw virus reported in 2017. According to the International Virus Classification Committee (ICTV) criteria for new viruses, <80% homology indicates a new virus. We tentatively named this virus DSP4. The genome fragment of this virus sequence was only detected in ticks in the Daishan area but not in the whole blood of local animals. The overall positivity rate was 1.6% (3/184), and three positive samples were R. haemaphysaloides (Table 3).

ZSP7 virus

ZSP7 is another novel virus discovered in this study. It harbors three reads annotated in the pooled samples. The nucleotide sequence derived from the three reads showed 79% homology with the MG22 virus found in Turkey in 2017. The virus genome was detected in one tick sample, R. haemaphysaloides in the Zhoushan area, with an overall positivity rate of 0.54% (1/184) (Table 3).

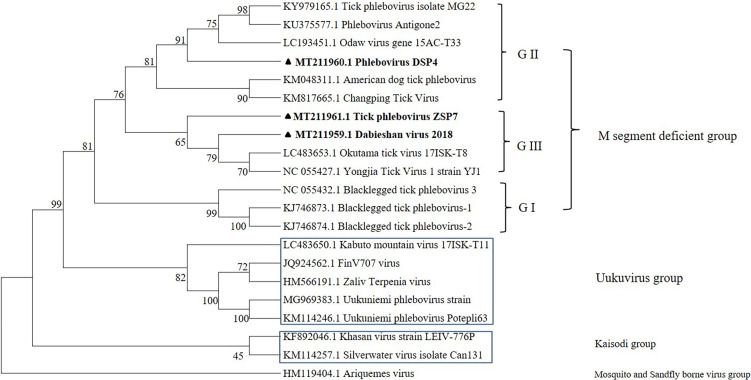

Phylogenetic analysis

By amplifying the Dabieshan virus genome sequence, a total L segment sequence of 949 bp was obtained. We also obtained the whole coding sequence of the ZSP7 virus RdRp gene on the L segment. The total length was 6,515 bp, and the nucleotide homology with the RdRp gene of the MG22 virus was 79%. The obtained DSP4 virus gene sequence displayed a 465 bp L segment and shared 77% homology with the Odaw virus. To understand their genetic relationships with other typical phleboviruses, we constructed phylogenetic trees based on the L segment encoding the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene. Phylogenetic analysis (Fig. 3) indicated that the above three viruses were in the same branch as M segment-deficient viruses. All have been detected by NGS [11, 13, 22], are phylogenetically distinct from any mosquito- and sandfly borne viruses (pathogenic virus group), and have the characteristic three traditional segments [25]. A previous study reported that M segment-deficient viruses can continue to be divided into three groups (GI-GIII) that appear to correspond almost entirely with their host tick genera. More specifically, these include GI from Ixodes ticks, GII from Dermacentor, Hyalomma, and Rhipicephalus ticks, and GIII from Haemaphysalis [11]. In our study, Dabieshan virus (GIII) was discovered in both Rhipicephalus and Haemaphysalis ticks, and ZSP7 (GIII) was discovered in R. haemaphysaloides, which is incompatible with the above classification.

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of the partial cds of RdRp (465 bp). The filled triangles represent ZSP7, Dabieshan, and DSP4 strains. The trees were generated using the maximum likelihood method with 1,000 bootstrap replications based on Mega7 software. Numbers above the branches indicate bootstrap values. Sequences in the trees are indicated as GenBank accession number and strain name.

Nucleotide sequence information

All genome sequences of DSP4, ZSP7, and the Dabieshan virus have been submitted to GenBank (accession numbers MT211960, MT211961, DSP4 and MT211959, respectively). Other NGS-detected viral sequences were not uploaded because they were not amplified using PCR.

DISCUSSION

With the rapid development of metagenomics based on NGS technology, viral metagenomics has become a major method for detecting viruses, especially the discovery of novel viruses. In 2015, Zhang et al. profiled the transcriptomes of over 220 invertebrate species sampled across nine animal phyla and reported the discovery of 1,445 types of RNA viruses [13]. This information has been fundamentally important in understanding the diversity of tick-associated viruses. The greatest benefit of viral metagenomics is that it provides more solid evidence for research on viral ecology and evolution. PCR is a traditional and economical method that can help confirm genetically identified viruses in samples. However, PCR is less lacks comprehensive compared to NGS. NGS combined with PCR will make viral genomics more reliable and convenient.

In this study, we conducted NGS on a pool of 60 ticks to systematically analyze tick-associated viruses, and used another 184 ticks for virus screening. Prevalence analysis indicated that H. longicornis and R. haemaphysaloides were the dominant species, consistent with a previous study [15]. NGS revealed 723 reads related to viruses, which was less than that in a previous report [2]. Although several viral sequences were detected by NGS, only Dabieshan, DSP4, and ZSP7 viruses were confirmed by PCR. ZSP7 and DSP4 share 77–79% nucleotide sequence homology with MG22 and Odaw viruses, respectively, based on partial L segment analysis. All three viruses belong to the Phenuiviridae family and were grouped into the M segment-deficient group. The latter group has been reported in other studies [11, 13, 22]. The detailed structure and pathogenicity of these viruses are still unknown. We also unsuccessfully attempted to isolate these PCR-detected viruses through Vero-E6 cell culture and newborn mouse inoculation [6]. It is possible that the titer of the targeted viruses was too low to infect cells and animals. Another possibility is that these viruses do not be capable of interspecies transmission. In addition, NGS detected some viral reads potentially derived from human pathogenic viruses, which can cause severe diseases, such as SFSTV, HBV, and human mastadenovirus. These viral sequences detected only in NGS, but not in PCR, may be false-positives or are due to contamination of host blood. These possibilities must be examined in future studies.

In summary, using a powerful NGS approach, we identified two novel tick-associated viruses and one known virus in tick samples from the Zhoushan Archipelago. A wide range of severe epidemic viruses harbored in ticks could not be detected due to the limitations of this study, which included the limited number of ticks sampled, sampling season, and sequencing platform. In future studies, we will expand the research area of tick sampling to facilitate a more precise elucidation of the distribution of tick-borne viruses and their evolutionary relationships.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Project of Disease Prevention and Control (15WQ006), Background Investigation of Disease (15WQ006), and the Jiangsu Province Science and Technology Support Program Project (BE2017620).

REFERENCES

- 1.Andreotti R., Pérez de León A. A., Dowd S. E., Guerrero F. D., Bendele K. G., Scoles G. A.2011. Assessment of bacterial diversity in the cattle tick Rhipicephalus (Boophilus) microplus through tag-encoded pyrosequencing. BMC Microbiol. 11: 6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouquet J., Melgar M., Swei A., Delwart E., Lane R. S., Chiu C. Y.2017. Metagenomic-based surveillance of pacific coast tick dermacentor occidentalis identifies two novel bunyaviruses and an emerging human ricksettsial pathogen. Sci. Rep. 7: 12234. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-12047-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowman A. S., Nuttall P. A.2008. Ticks: biology, disease and control. Parasitology 129: S1–S1. doi: 10.1017/S0031182004006560 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Z., Liu Q., Liu J. Q., Xu B. L., Lv S., Xia S., Zhou X. N.2014. Tick-borne pathogens and associated co-infections in ticks collected from domestic animals in central China. Parasit. Vectors 7: 237. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chitimia L., Lin R. Q., Cosoroaba I., Braila P., Song H. Q., Zhu X. Q.2009. Molecular characterization of hard ticks from Romania by sequences of the internal transcribed spacers of ribosomal DNA. Parasitol. Res. 105: 1479–1482. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1581-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fang X. U., Yao P. P., Zhu H. P., Xie R. H.2009. Molecular cloning and nucleotide sequence analysis of the s-segment in hantavirus isolated in zhejiang province. Chin. J. Zoonoses 25: 665–668. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Firth C., Bhat M., Firth M. A., Williams S. H., Frye M. J., Simmonds P., Conte J. M., Ng J., Garcia J., Bhuva N. P., Lee B., Che X., Quan P. L., Lipkin W. I.2014. Detection of zoonotic pathogens and characterization of novel viruses carried by commensal Rattus norvegicus in New York City. MBio 5: e01933–e14. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01933-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu Y., Li S., Zhang Z., Man S., Li X., Zhang W., Zhang C., Cheng X.2016. Phylogeographic analysis of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus from Zhoushan Islands, China: implication for transmission across the ocean. Sci. Rep. 6: 19563. doi: 10.1038/srep19563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gargili A., Estrada-Peña A., Spengler J. R., Lukashev A., Nuttall P. A., Bente D. A.2017. The role of ticks in the maintenance and transmission of Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus: a review of published field and laboratory studies. Antiviral Res. 144: 93–119. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaiser R.2016. Tick-borne encephalitis. Nervenarzt 87: 667–680 (in German). doi: 10.1007/s00115-016-0134-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi D., Murota K., Itokawa K., Ejiri H., Amoa-Bosompem M., Faizah A. N., Watanabe M., Maekawa Y., Hayashi T., Noda S., Yamauchi T., Komagata O., Sawabe K., Isawa H.2020. RNA virome analysis of questing ticks from Hokuriku District, Japan, and the evolutionary dynamics of tick-borne phleboviruses. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 11: 101364. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2019.101364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Leblebicioglu H., Ozaras R., Irmak H., Sencan I.2016. Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever in Turkey: current status and future challenges. Antiviral Res. 126: 21–34. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2015.12.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li C. X., Shi M., Tian J. H., Lin X. D., Kang Y. J., Chen L. J., Qin X. C., Xu J., Holmes E. C., Zhang Y. Z.2015. Unprecedented genomic diversity of RNA viruses in arthropods reveals the ancestry of negative-sense RNA viruses. eLife 4: e05378. doi: 10.7554/eLife.05378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu J. Z., Yang X. J.2013.Ticks [M]. China Forestry Publishing House. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luo L. M., Zhao L., Wen H. L., Zhang Z. T., Liu J. W., Fang L. Z., Xue Z. F., Ma D. Q., Zhang X. S., Ding S. J., Lei X. Y., Yu X. J.2015. Haemaphysalis longicornis ticks as reservoir and vector of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome virus in China. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 21: 1770–1776. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.150126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McMullan L. K., Folk S. M., Kelly A. J., MacNeil A., Goldsmith C. S., Metcalfe M. G., Batten B. C., Albariño C. G., Zaki S. R., Rollin P. E., Nicholson W. L., Nichol S. T.2012. A new phlebovirus associated with severe febrile illness in Missouri. N. Engl. J. Med. 367: 834–841. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meng F., Ding M., Tan Z., Zhao Z., Xu L., Wu J., He B., Tu C.2019. Virome analysis of tick-borne viruses in Heilongjiang Province, China. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 10: 412–420. doi: 10.1016/j.ttbdis.2018.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pettersson J. H., Shi M., Bohlin J., Eldholm V., Brynildsrud O. B., Paulsen K. M., Andreassen Å., Holmes E. C.2017. Characterizing the virome of Ixodes ricinus ticks from northern Europe. Sci. Rep. 7: 10870. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11439-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roe R. M., Donohue K. V., Khalil S. M., Sonenshine D. E.2008. Hormonal regulation of metamorphosis and reproduction in ticks. Front. Biosci. 13: 7250–7268. doi: 10.2741/3226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun J., Lin J., Gong Z., Chang Y., Ye X., Gu S., Pang W., Wang C., Zheng X., Hou J., Ling F., Shi X., Jiang J., Chen Z., Lv H., Chai C.2015. Detection of spotted fever group Rickettsiae in ticks from Zhejiang Province, China. Exp. Appl. Acarol. 65: 403–411. doi: 10.1007/s10493-015-9880-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Solomon T., Hart I. J., Beeching N. J.2007. Viral encephalitis: a clinician’s guide. Pract. Neurol. 7: 288–305. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.129098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tokarz R., Williams S. H., Sameroff S., Sanchez Leon M., Jain K., Lipkin W. I.2014. Virome analysis of Amblyomma americanum, Dermacentor variabilis, and Ixodes scapularis ticks reveals novel highly divergent vertebrate and invertebrate viruses. J. Virol. 88: 11480–11492. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01858-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu X. J., Liang M. F., Zhang S. Y., Liu Y., Li J. D., Sun Y. L., Zhang L., Zhang Q. F., Popov V. L., Li C., Qu J., Li Q., Zhang Y. P., Hai R., Wu W., Wang Q., Zhan F. X., Wang X. J., Kan B., Wang S. W., Wan K. L., Jing H. Q., Lu J. X., Yin W. W., Zhou H., Guan X. H., Liu J. F., Bi Z. Q., Liu G. H., Ren J., Wang H., Zhao Z., Song J. D., He J. R., Wan T., Zhang J. S., Fu X. P., Sun L. N., Dong X. P., Feng Z. J., Yang W. Z., Hong T., Zhang Y., Walker D. H., Wang Y., Li D. X.2011. Fever with thrombocytopenia associated with a novel bunyavirus in China. N. Engl. J. Med. 364: 1523–1532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhan J., Wang Q., Cheng J., Hu B., Li J., Zhan F., Song Y., Guo D.2017. Current status of severe fever with thrombocytopenia syndrome in China. Virol. Sin. 32: 51–62. doi: 10.1007/s12250-016-3931-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zivcec M., Safronetz D., Scott D. P., Robertson S., Feldmann H.2018. Nucleocapsid protein-based vaccine provides protection in mice against lethal Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever virus challenge. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 12: e0006628. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.