Abstract

In patients with severe upper extremity weakness that may result from peripheral nerve injuries, stroke, and spinal cord injuries, standard therapy in the earliest stages of recovery consists primarily of passive rather than active exercises. Adherence to prescribed therapy may be poor, which may contribute to suboptimal functional outcomes. The authors have developed and integrated a custom surface electromyography (sEMG) device with a video game to create an interactive, biofeedback-based therapeutic gaming platform. Sensitivity of our custom sEMG device was evaluated with simultaneous needle EMG recordings. Testing of our therapeutic gaming platform was conducted with a single, 30-minute gameplay session in 19 patients with a history of peripheral nerve injury, stroke, spinal cord injury, and direct upper extremity trauma, including 11 patients who had undergone nerve and/or tendon transfers. Our sEMG device was highly sensitive in detecting low levels of voluntary muscle activation and was used with 10 distinct muscles of the arm, forearm, and hand. Nerve and tendon transfer patients successfully activated the donor nerve/muscle and elicited the desired movement to engage in gameplay. On surveys of acceptability and usability, patients felt the system was enjoyable, motivating, fun, and easy to use, and their hand therapists expressed similar enthusiasm. Surface EMG-based therapeutic gaming is a promising approach to rehabilitation that warrants further development and investigation to examine its potential efficacy not only for building muscle strength and endurance, but also for facilitating motor relearning after nerve and tendon transfer surgeries.

INTRODUCTION

Severe upper extremity weakness from central and peripheral nervous system etiologies, including stroke, spinal cord injuries, brachial plexus injuries, nerve compression syndromes, and direct penetrating trauma, may have devastating impacts on independence and quality of life.1–4 Rehabilitation presents several common challenges, including loss of motivation, lack of access to specialized therapy, and delayed initiation of active exercises in patients without clinically visible limb movement.5–10 To address these, we developed an innovative approach through integration of a surface electromyography (sEMG) device with a video game. Using noninvasive electrodes placed on the skin, sEMG detects electrical signals generated by underlying muscle and may better represent neural efferent activity than direct nerve recordings.11,12 To accommodate patients in early recovery with significant weakness, we use sEMG signals as input for a video game, providing an engaging way of visually confirming muscle activity.13–21 We hypothesize that this interactive, biofeedback-based therapeutic gaming platform will facilitate engagement with active rehabilitation by being motivating, enjoyable, and easy to use for patients.

METHODS

Technical Development

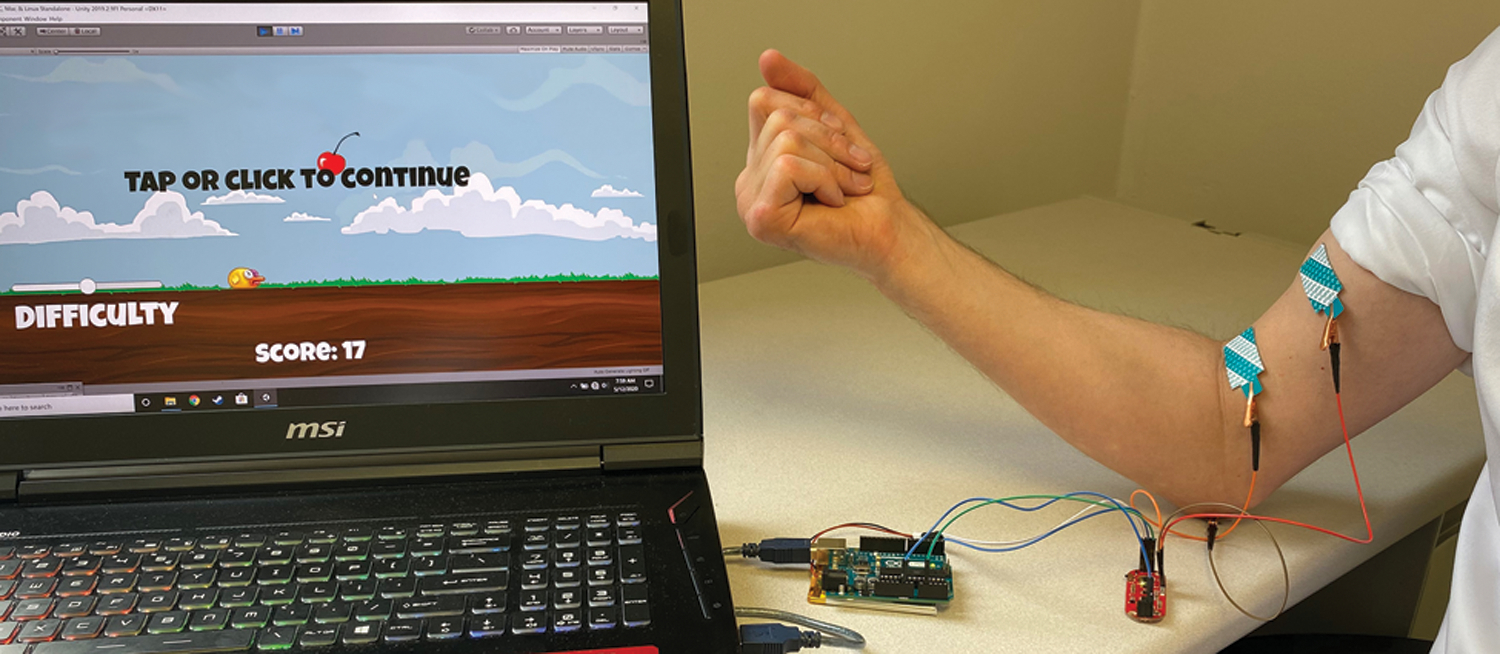

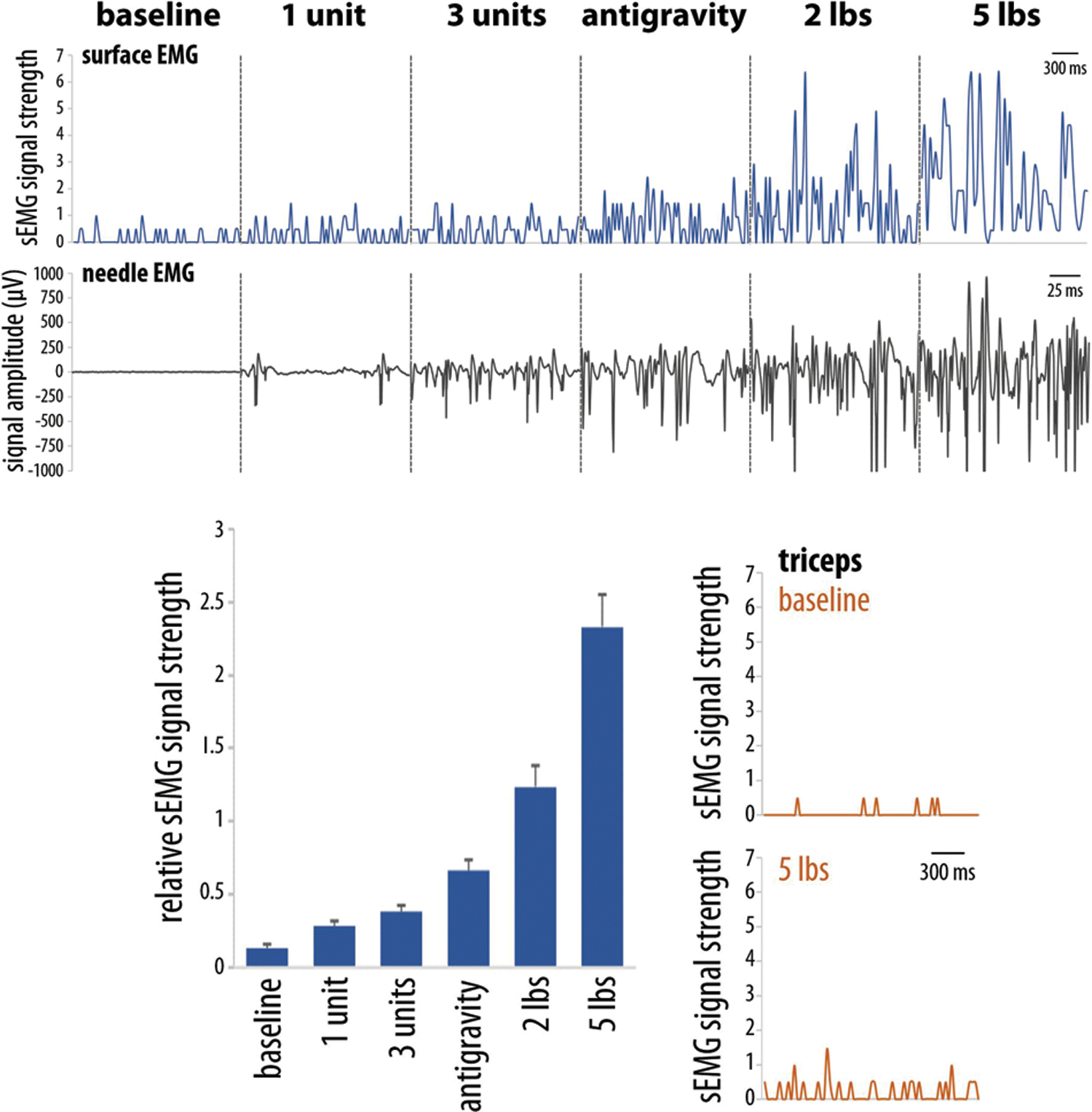

We built a custom sEMG system (Figure 1), combined with a side-scrolling game inspired by Flappy Bird; the objective is to collect cherries located at different heights to earn points. To test device sensitivity, we targeted the biceps brachii muscle and performed simultaneous surface and needle EMG recordings during isometric elbow flexion at 90°. Even with single motor unit recruitment, our sEMG device successfully detected changes in signal amplitude (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Initial surface EMG-based gaming setup.

We built a custom sEMG system consisting of: 1) disposable adhesive tab electrodes placed on the skin surface over the muscle of interest (Natus), 2) sEMG circuit board (MyoWare Muscle Sensor, Advancer Technologies), 3) microcontroller (Arduino UNO), and 4) computer for signal processing. Adhesive electrodes are positioned over the biceps brachii muscle, and sEMG signals are transmitted through the Arduino microcontroller via USB to a computer, which translates the raw signals into input for gameplay. In our side-scrolling game, the bird moves horizontally across the screen at a set speed, and sEMG signals surpassing a specific threshold trigger the bird to flap its wings once to move vertically upward. Players must coordinate muscle contractions to reach cherries, while periods of rest during muscle relaxation cause the bird to descend. The goal is to maneuver the flying bird to collect cherries located at different heights. The game ends when the bird crashes to the ground.

Figure 2. Custom surface EMG device sensitivity testing.

Adhesive electrodes were positioned over the upper arm of a healthy individual. Data recorded simultaneously from the biceps brachii muscle with our custom sEMG device (blue) and monopolar needle EMG (black) during isometric elbow flexion shows increased signal amplitudes with increased resistance. Average sEMG amplitude significantly increases with increased muscle activation (p<0.0001, one-way ANOVA). The sEMG signal from the triceps muscle (orange) does not significantly increase during elbow flexion.

Pilot Testing

In this prospective observational study, adult patients were referred to include upper extremity traumatic or peripheral nerve injuries, spinal cord injuries, and stroke, and tested between November 2019 and February 2020. Exclusion criteria included inability to follow instructions/complete questionnaires in English, inability to detect sEMG signals over muscle(s) of interest, and illness or medical instability that would otherwise prevent participation in standard physical/occupational therapy. After providing informed consent, patients meeting study criteria were recruited to participate in a single, supervised 30-minute testing session. Adhesive sEMG electrodes were positioned over the muscle(s) of interest based on individuals’ specific injuries, and brief verbal instructions were given on how to engage in gameplay. Following gameplay, participants completed surveys that explored acceptability, usability as assessed by the system usability scale (SUS), and open-ended feedback about their experience (see Appendix, Supplementary Digital Content 1, which shows a survey that was completed by participants after completing the test session playing the sEMG video game).22–24 Open-ended feedback surveys were also administered to participants’ occupational therapists who observed their testing sessions. All study procedures received Institutional Review Board approval.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of all referred patients, one was excluded due to severe pain with movement. In the 19 participants who underwent testing, all except one were able to engage in gameplay, even those lacking antigravity muscle strength (Table 1). Nerve/tendon transfer patients were instructed to perform the voluntary movement that fires the donor nerve/tendon, while sEMG electrodes were placed over the recipient muscle; voluntary activation of the appropriate donor nerve/tendon is required to generate an sEMG signal from the corresponding recipient muscle, which in turn serves as the input for the video game. All nerve/tendon transfer participants were successful in understanding this concept and playing the video game. Our single unsuccessful patient was tested three days after a stroke; global cognitive impairments with delayed reaction times prevented her from properly timing her muscle contractions to play the game.

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

A total of 19 patients were tested with a variety of etiologies of upper extremity weakness. Of these, 11 patients underwent reconstructive surgeries that attempted to improve upper extremity function. Duration of time between date of injury or date of most recent reconstructive surgery (if applicable) and date of testing session is listed.

| # | Age | Sex | Injury | Time since surgery, or injury if no surgery | Type of surgical reconstruction | Reconstructive procedure(s) performed | Muscle(s) tested |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| 1 | 21 | M | Right brachial plexus injury | 9.0 months | Nerve transfer | triceps branch to axillary nerve; SAN to SSN | Deltoid |

| 2 | 53 | M | Right brachial plexus injury | 12.1 months | Nerve transfer | triceps branch to axillary nerve; SAN to SSN | deltoid |

| 3 | 71 | M | Left brachial plexus injury | 12 days | Nerve transfer | triceps branch to axillary nerve; FCU fascicle to brachialis branch; SSN neurolysis | deltoid, brachialis |

| 4 | 49 | M | Left brachial plexus injury with near amputation of left forearm | 15.1 months | Nerve transfer | triceps branch to axillary nerve; FCU fascicle to biceps branch | deltoid, biceps |

| 5 | 55 | M | Left brachial plexus injury | 2.8 years | Nerve transfer | FCU fascicle to biceps branch | biceps |

| 6 | 20 | F | Left upper extremity compartment syndrome with median and ulnar nerve compression | 8.7 months | Nerve transfer | AIN to ulnar motor nerve | FDI, APB |

| 7 | 74 | F | Right carpal and cubital tunnel syndromes | 1.7 months | Nerve decompression with nerve transfer | Open carpal and cubital tunnel releases; AIN to ulnar motor nerve | FDI, APB |

| 8 | 43 | M | Right brachial plexus injury | 2.4 years | Nerve graft; nerve transfer; FFMT | intercostal nerves (x3) to musculocutaneous nerve; sural cable graft to SAN; free functional gracilis | biceps |

| 9 | 40 | M | Left brachial plexus injury | 3.5 months | Remote history of multiple nerve transfers and FFMT; tendon transfer | PT to ECRB tendon; FDS of ring finger to EDC tendon | PT, free functional gracilis |

| 10 | 23 | M | Right transhumeral gunshot injury with radial nerve transection | 1.1 months | Nerve transfer; tendon transfer | PT to ECRB tendon; FCR fascicle to PIN nerve | PT |

| 11 | 26 | M | Right brachial plexus birth injury | 2.0 months | Tendon transfer | PT to ECRB tendon; FCR to EDC tendon | PT, FCR |

| 12 | 27 | M | Left elbow gunshot injury with median and ulnar nerve transection | 1.3 months | None | None | biceps |

| 13 | 25 | M | Right transhumeral near amputation without nerve transection | 5.0 months | None | None | biceps, ECRL, EDC, FDI |

| 14 | 82 | F | Left frontal intraparenchymal hemorrhage | 3 days | None | None | ECRL, EDC, FDI |

| 15 | 84 | F | Left middle cerebral artery stroke | 6 days | None | None | biceps |

| 16 | 58 | M | Left basal ganglia intraparenchymal hemorrhage | 33 days | None | None | biceps |

| 17 | 21 | M | Right vertebral artery stroke | 3.9 months | None | None | FDS |

| 18 | 64 | M | C2 AIS D spinal cord injury | 7.2 months | None | None | biceps |

| 19 | 19 | M | C4 AIS A spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury | 8.0 months | None | None | ECRL |

Abbreviations: abductor pollicis brevis (APB), anterior interosseous nerve (AIN), extensor carpi radialis brevis (ECRB), extensor carpi radialis longus (ECRL), extensor digitorum communis (EDC), flexor carpi radialis (FCR), flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU), first dorsal interosseous (FDI), flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS), free functional muscle transfer (FFMT), posterior interosseous nerve (PIN), pronator teres (PT), spinal accessory nerve (SAN), suprascapular nerve (SSN)

Acceptability and Usability

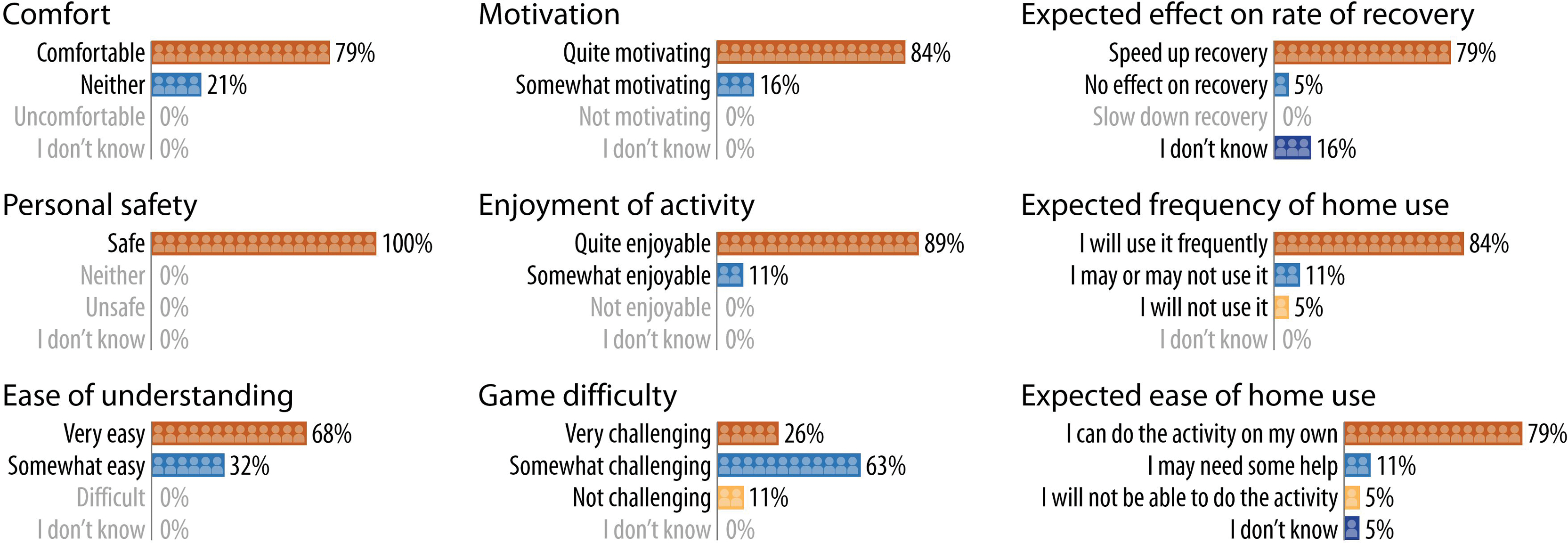

Participants endorsed multiple benefits of sEMG-based therapeutic gaming (Figure 3; see Table, Supplementary Digital Content 2, which shows open-ended feedback on the sEMG-based therapeutic gaming experience from participants who had undergone nerve and tendon reconstruction and from their occupational/hand therapists who observed their patients during testing sessions). Ratings for fun averaged 7.3 out of 10. Two patients reported a dramatic reduction in pain during gameplay; others denied discomfort relative to their baseline. Eight participants (42%) shared that their muscles felt “tired” or “sore” after testing. Usability was assessed with the SUS (scale 0–100; good for scores 68–81; excellent for scores above 81).24 Patients’ SUS score averaged 85 (± 2.5 SEM).

Figure 3. Acceptability of our surface EMG-based therapeutic gaming prototype.

Patients responded to a multiple-choice survey with the above items. Even with our initial prototype, participants expressed enthusiasm and overall positive feedback on all facets measured.

DISCUSSION

This pilot study of our sEMG-driven therapeutic gaming prototype was successful. EMG signals from nascent muscle activity are present long before significant movement is observed clinically. Because our highly sensitive device can detect activation of even a single motor unit, our system has the potential for use in patients with severe muscle weakness, allowing active therapy to begin earlier. In contrast, currently available exergaming platforms rely on handheld controllers or motion capture cameras for game input, which requires significant strength and range of motion to use.21

We were encouraged to find that participants quickly learned to activate specific muscles to control the game, regardless of injury etiology. This is especially significant for nerve/tendon transfer patients, who often have difficulty regaining voluntary neuromuscular control of nonanatomic nerve or musculotendinous reconstructions.25–30 To promote motor relearning, our sEMG-based method allows individual muscles of interest to be targeted and provides direct visual biofeedback of appropriate donor activation.

By integrating our sEMG device with a video game, we are taking advantage of the benefits of gamification. Exergaming is well-tolerated with few adverse effects and is associated with improved adherence and motivation; however, most existing exergames are serious games emphasizing a specific physical movement or activity.17–19,31,32 In contrast, our game is more fun and entertainment-focused, allowing patients to strengthen their muscles by using sEMG signals as game input without having to mentally focus on exercising. Furthermore, our therapeutic gaming platform may enhance patient engagement and motivation compared to simple visual biofeedback of muscle activation. These factors may protect against frustration and foster adherence to therapy, especially when the limb is too weak to produce significant movement in the earliest stages of recovery. Based on survey responses, both patients and their occupational therapists expressed enthusiasm for our approach.

We recognize several limitations of this small study. First, although our system is excellent even for weak muscles, patients with significant cognitive deficits or pain with voluntary movement cannot partake. Second, our pilot testing involved a single session, which does not capture changes in patient perspectives with repeated use. Finally, one technical challenge was appropriate device placement, requiring smaller electrodes for hand muscles and occasionally electrode repositioning to detect signals from desired target muscles.

Our study included a heterogeneous population of participants, implicating a role for sEMG-based therapeutic gaming in a wide variety of patients despite different etiologies of weakness. As we demonstrated, one innovative application is as an active form of therapy after nerve and tendon transfers. Contraindications for use include patients with cognitive impairments or debilitating pain precluding engagement with active therapy or with unresolved wound healing issues such that the sEMG sensors are unable to adhere to the skin surface. The insights we gained through building and testing our prototype are critical in understanding the essential elements necessary for creating a viable platform, and this knowledge is guiding our current work in optimizing the system for independent use by patients at home.

CONCLUSION

Surface EMG-based therapeutic gaming is a promising approach for rehabilitation. It may enable earlier initiation of active therapy to build muscle strength, facilitate motor relearning after nerve/tendon transfers, and promote patient engagement and motivation throughout the recovery process. We are currently developing a portable, wireless sEMG-driven therapeutic gaming system, and future studies are planned to evaluate its efficacy for enhancing functional recovery.

Supplementary Material

Appendix, Supplementary Digital Content 1. A survey that was completed by participants after completing the test session playing the sEMG video game.

Table, Supplementary Digital Content 2. Open-ended feedback on the sEMG-based therapeutic gaming experience from participants who had undergone nerve and tendon reconstruction and from their occupational/hand therapists who observed their patients during testing sessions.

Financial Disclosure Statement:

This work was supported by the University of Washington Clinical Learning, Evidence and Research (CLEAR) Center’s Pilot and Feasibility Award (NIH/NIAMS P30 AR072572), University of Washington Walter C. and Anita C. Stolov Research Fund, the School of STEM on the University of Washington Bothell campus, and University of Washington Housestaff Association Research Award. The authors declare that they have no other financial conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Footnotes

This work was accepted for presentation at the following virtual meetings: Plastic Surgery Research Council (PSRC) 2020, NIH “Rehabilitation Research 2020: Envisioning a Functional Future”, American Society for Peripheral Nerve (ASPN) 2021

REFERENCES

- 1.Gray B. Quality of life following traumatic brachial plexus injury: A questionnaire study. Int J Orthop Trauma Nurs. 2016;22:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mayo NE, Wood-Dauphinee S, Ahmed S, et al. Disablement following stroke. Disabil Rehabil. 1999;21(5–6):258–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson KD. Targeting recovery: priorities of the spinal cord-injured population. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21(10):1371–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Snoek GJ, MJ IJ, Hermens HJ, Maxwell D, Biering-Sorensen F. Survey of the needs of patients with spinal cord injury: impact and priority for improvement in hand function in tetraplegics. Spinal Cord. 2004;42(9):526–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ada L, Dorsch S, Canning CG. Strengthening interventions increase strength and improve activity after stroke: a systematic review. Aust J Physiother. 2006;52(4):241–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaughnessy M, Resnick BM, Macko RF. Testing a model of post-stroke exercise behavior. Rehabil Nurs. 2006;31(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang CE, MacDonald JR, Gnip C. Counting repetitions: an observational study of outpatient therapy for people with hemiparesis post-stroke. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2007;31(1):3–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maclean N, Pound P, Wolfe C, Rudd A. Qualitative analysis of stroke patients’ motivation for rehabilitation. BMJ. 2000;321(7268):1051–1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack K, McLean SM, Moffett JK, Gardiner E. Barriers to treatment adherence in physiotherapy outpatient clinics: a systematic review. Man Ther. 2010;15(3):220–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krishnan J, Chung KC. Access to Hand Therapy Following Surgery in the United States: Barriers and Facilitators. Hand Clin. 2020;36(2):205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hemmerling TM, Schmidt J, Wolf T, Wolf SR, Jacobi KE. Surface vs intramuscular laryngeal electromyography. Can J Anaesth. 2000;47(9):860–865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hemmerling TM, Schmidt J, Wolf T, Hanusa C, Siebzehnruebl E, Schmitt H. Intramuscular versus surface electromyography of the diaphragm for determining neuromuscular blockade. Anesth Analg. 2001;92(1):106–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feldner HA, Howell D, Kelly VE, McCoy SW, Steele KM. “Look, Your Muscles Are Firing!”: A Qualitative Study of Clinician Perspectives on the Use of Surface Electromyography in Neurorehabilitation. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(4):663–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson K, Pollock A, Bugge C, Brady M. Commercial gaming devices for stroke upper limb rehabilitation: a systematic review. Int J Stroke. 2014;9(4):479–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Celinder D, Peoples H. Stroke patients’ experiences with Wii Sports(R) during inpatient rehabilitation. Scand J Occup Ther. 2012;19(5):457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Neil O, Fernandez MM, Herzog J, et al. Virtual Reality for Neurorehabilitation: Insights From 3 European Clinics. PM R. 2018;10(9 Suppl 2):S198–S206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Beek JJW, van Wegen EEH, Bohlhalter S, Vanbellingen T. Exergaming-Based Dexterity Training in Persons With Parkinson Disease: A Pilot Feasibility Study. J Neurol Phys Ther. 2019;43(3):168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lauze M, Martel DD, Agnoux A, et al. Feasibility, Acceptability and Effects of a Home-Based Exercise Program Using a Gerontechnology on Physical Capacities after a Minor Injury in Community-Living Older Adults: A Pilot Study. J Nutr Health Aging. 2018;22(1):16–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rebsamen S, Knols RH, Pfister PB, de Bruin ED. Exergame-Driven High-Intensity Interval Training in Untrained Community Dwelling Older Adults: A Formative One Group Quasi- Experimental Feasibility Trial. Front Physiol. 2019;10:1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donoso Brown EV, Dudgeon BJ, Gutman K, Moritz CT, McCoy SW. Understanding upper extremity home programs and the use of gaming technology for persons after stroke. Disabil Health J. 2015;8(4):507–513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson KR, Woodbury ML, Phillips K, Gauthier LV. Virtual reality video games to promote movement recovery in stroke rehabilitation: a guide for clinicians. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2015;96(5):973–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pham TN, Wong JN, Terken T, Gibran NS, Carrougher GJ, Bunnell A. Feasibility of a Kinect((R))-based rehabilitation strategy after burn injury. Burns. 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.LaPiana N, Duong A, Lee A, et al. Acceptability of a Mobile Phone-Based Augmented Reality Game for Rehabilitation of Patients With Upper Limb Deficits from Stroke: Case Study. JMIR Rehabil Assist Technol. 2020;7(2):e17822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brooke J. SUS: A quick and dirty usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, McClelland IL, eds. Usability Evaluation In Industry. 1st ed: Taylor & Francis; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novak CB. Rehabilitation following motor nerve transfers. Hand Clin. 2008;24(4):417–423, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novak CB, von der Heyde RL. Rehabilitation of the upper extremity following nerve and tendon reconstruction: when and how. Semin Plast Surg. 2015;29(1):73–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kahn LC, Moore AM. Donor Activation Focused Rehabilitation Approach: Maximizing Outcomes After Nerve Transfers. Hand Clin. 2016;32(2):263–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sturma A, Hruby LA, Prahm C, Mayer JA, Aszmann OC. Rehabilitation of Upper Extremity Nerve Injuries Using Surface EMG Biofeedback: Protocols for Clinical Application. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturma A, Hruby LA, Farina D, Aszmann OC. Structured Motor Rehabilitation After Selective Nerve Transfers. J Vis Exp. 2019(150). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hruby LA, Sturma A, Aszmann OC. Surface Electromyographic Biofeedback as a Rehabilitation Tool for Patients with Global Brachial Plexus Injury Receiving Bionic Reconstruction. J Vis Exp. 2019(151). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Clausen JD, Nahen N, Horstmann H, et al. Improving Maximal Strength in the Initial Postoperative Phase After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Surgery: Randomized Controlled Trial of an App-Based Serious Gaming Approach. JMIR Serious Games. 2020;8(1):e14282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martens A, Diener H, Malo S. Game-Based Learning with Computers – Learning, Simulations, and Games. In: Pan Z, Cheok A, Müller W, El Rhalibi A, eds. Transactions on Edutainment. Vol 5080. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2008:172–190. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix, Supplementary Digital Content 1. A survey that was completed by participants after completing the test session playing the sEMG video game.

Table, Supplementary Digital Content 2. Open-ended feedback on the sEMG-based therapeutic gaming experience from participants who had undergone nerve and tendon reconstruction and from their occupational/hand therapists who observed their patients during testing sessions.