Abstract

Background:

The use of pejorative or stigmatizing language surrounding individuals with alcohol and substance use disorders adversely affects treatment seeking, quality of care, and treatment outcomes. In 2015, the International Society of Addiction Journal Editors released terminology guidelines that recommended against the use of words that contribute to stigma against individuals with an addictive disorder. This study examined the use of stigmatizing language in NIH-funded research and reviews published by the journal, Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research (ACER) from 2010-2020, with the goal of sharing the results with the alcohol research community to enhance awareness.

Methods:

The search for stigmatizing language in ACER was limited to NIH-funded articles made publicly available on PubMed Central (PMC). Though ACER is not an open access journal, original research and reviews directly funded by NIH are published to PMC for open access to the public as required by the conditons of NIH funding. ACER articles published on PMC were searched from 2010-2020 with specific queries for individual terms of interest including those considered pejorative (“alcoholic,” “addict,” “abuser”) and outdated (“alcohol dependent,” “alcohol abuse,” “alcoholism”). The number of articles containing a term of interest for a given year were divided by the total number of articles published in that year to determine the percent use of each term per year.

Results:

Our search of research and reviews (n=1903) published in ACER on PMC determined that although the use of pejorative and outdated terminology has decreased over time, there is continued use of the term “alcoholic” over the last decade. Specifically, over 40% of articles searched for in PMC still included “alcoholic” in the year 2020. The results of a separate manual search (n=110) on Wiley Online Database suggested that approximately 30% of articles used the term “alcoholic” in a stigmatizing manner.

Conclusions:

Stigmatizing language can perpetuate negative biases against people with alcohol use disorder. We encourage researchers to shift away from language that maintains discriminatory conceptions of alcohol use disorder. Reducing stigma has the potential to increase rates of treatment seeking, and improve treatment outcomes for individuals managing alcohol use disorder.

INTRODUCTION

The use of pejorative language surrounding individuals with alcohol use disorder and substance use disorder adversely affects treatment seeking, quality of care, and treatment outcomes. Language shapes human understanding, and as such, the words used to describe addictive disorders can implicitly signal a larger set of social attitudes and values. For example, a person using prescribed narcotics is a “patient” receiving “medicine,” while a person using narcotics without a prescription is a “drug addict” or “junkie” “strung out” on “dope” (White, 2004). Consequently, appropriate language use in the scientific community is important in influencing the ways researchers, physicians, and the public perceive people who are managing substance use and recovery. Addictive disorders are often perceived as self-inflicted, and research has shown that patients affected by problems related to substance and alcohol use are viewed more negatively than patients with other medical or psychiatric disorders (Barry, McGinty, Pescosolido, & Goldman, 2014). These beliefs are formulated in part by inappropriate language that propagates social stigma that can deprive individuals of their respect, dignity, and personal identity (Broyles et al., 2014; Zwick, Appleseth, & Arndt, 2020). Terms such as “addicts” or “alcoholics” generalize people by their illness, erasing the physical, social, and environmental factors that contribute to a person’s substance use disorder. As a result, the inclusion of such terms in research publications propagates the idea that problematic substance use arises from an individual’s personal shortcomings or moral failings. In contrast, person first language, such as “a person with alcohol use disorder,” reclaims an individual’s personal identity by placing the person before their illness or behavior.

Starting in 2015, the International Society of Addiction Journal Editors (ISAJE) released terminology guidelines that recommended against the use of words that “stigmatize people who use alcohol, drugs, other addictive substances, or have an addictive behavior” (“Statements and Guidelines Addiction Terminology,”). In particular, the ISAJE recommended a shift to terms such as “substance use disorder” as opposed to “abuse” and “abuser,” and to use ‘person first’ language, i.e., “person with a substance use disorder.” Following these guidelines, the Research Society on Alcoholism (RSA) and the journal Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research (ACER) reaffirmed these recommendations in 2018 and specifically urged against the use of the terms such as “alcoholic,” “abuser,” and “addict,” which were shown to elicit negative bias (Ashford, Brown, & Curtis, 2018). These statements accompanied the change in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) from DSM-IV to DSM-5 in 2013, which diagnosed individuals with “alcohol use disorder” as opposed to “alcohol abuse” or “alcohol dependence” (“Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM–IV and DSM–5,”). This change in terminology recognizes problems related to alcohol use as a disorder and acknowledges that there is a spectrum of symptoms unique to each individual.

The choice of language used to describe people with substance use disorders is significant as stigmatizing terms can lead to explicit bias among behavioral health professionals and medical practitioners (Kelly, Dow, & Westerhoff, 2010) (van Boekel, Brouwers, van Weeghel, & Garretsen, 2013), which has been associated with decreased quality of care and treatment outcomes for people with substance use disorders (van Boekel et al., 2013). In addition, measurements of implicit bias, defined as an individual’s subconscious beliefs, have also revealed that individuals hold significantly more negative autonomic attitudes toward the term “addict” as opposed to the term “a person with a substance use disorder” (Ashford, Brown, & Curtis, 2019; Ashford, Brown, McDaniel, & Curtis, 2019). A combination of explicit and implicit bias, which is elicited at least in part by language choice, may partially account for the low rates of treatment seeking in people with a substance use disorder (Clement et al., 2015; Stone, 2015; Stringer & Baker, 2018). Out of the estimated 19.7 million people aged 12 or older who met the criteria for substance use disorder in 2017, only 4 million people received treatment, with only 2.5 million people receiving treatment in a facility specializing in substance use disorder (SAMHSA, 2018). Additionally, of the people who did not seek treatment, 20.5% believed that receiving treatment would result in work consequences and 17.2% believed that receiving treatment would result in social consequences (SAMHSA, 2018).

As such, the failure to exclude pejorative and outdated vocabulary in research can perpetuate negative beliefs around those struggling with substance use disorders, contributing to greater social stigma that discourages treatment seeking and adversely affects a person’s quality of care. Despite this, not all researchers have shifted to the updated terminology recommended by the ISAJE. This study conducted an analysis of NIH-funded papers published in ACER on Pub MedCentral (PMC) to track the use of pejorative and outdated terminology from 2010-2020, with the goal of sharing the results with the alcohol research community to enhance awareness. Research that is freely available to the public (on a database such as PMC) has a greater reach as more people can access it absent barriers such as subscriptions or fees. We believe such publicly available and federally supported work is comparatively more able to propagate stigma in the broader scientific and social community than work that is not publicly available. Thus, by concentrating our search to ACER papers available on PMC, we hoped to track the trends in the use of problematic language in the kinds of scientific work that may have the largest contribution to the broader stigma surrounding alcohol use disorder.

METHODS

Publicly available original research and reviews published in ACER were searched for stigmatizing and outdated language from 2010-2020. The search was limited to NIH-funded articles available on PMC. Though ACER is not an open access journal, full text articles directly funded by the NIH are published to PMC as required by the conditions of NIH funding. The decision to limit the search to those published on PMC was made primarily because research that receives federal support and is made widely available to the public has the greatest potential to influence public perception surrounding alcohol use disorder. Additionally, the advanced search builder in PMC was able to discriminate between the search results found in the body of the paper from the search results found in the references. With the “Body – All Words” search function, it was possible to search for a term within all words included in the body of the article while also excluding for results found only in the abstract and references. This distinction is crucial for the purposes of this study as a search of the full text would also return papers that reference previous work containing stigmatizing or outdated language, regardless if such language is present in the writing of the paper itself.

Furthermore, though conference materials are published on ACER, we chose to limit our search to original research and reviews using the “publication type” filter. The search of NIH-funded research and reviews represented 63% of total articles in ACER from 2010-2020. This was determined by comparing the total articles published in ACER on PMC, which contains the limited sample of full text papers funded by NIH, and PubMed, which contains the abstracts from all original research and reviews published. Using PMC’s search engine, we refined the search by selecting the journal, ACER, and the publication years, 2010-2020. From this result, we found that our search of NIH-funded articles published in ACER on PMC consisted of a total of 1,903 articles. This query was repeated on PubMed, which determined that a total of 3,020 abstracts from original research and reviews were published in ACER from 2010-2020. By dividing our sample of articles in ACER on PMC (1,903) with the total of articles in ACER on PubMed (3,020), we calculated that our sample of publicly available, NIH-funded research consisted of 63% of the total ACER articles published in the last decade.

To conduct the search of articles in ACER on PMC, we used the advanced search builder to select the journal, Alcoholism: Clinical Experimental Research, as well as the appropriate publication year (from 2010 to 2020) on PMC. From this initial result, we determined the total amount of articles published in ACER on PMC in a given year. To find the number of articles containing stigmatizing or outdated language, terms of interest (“alcohol abuse,” “alcoholic/alcoholics,” “alcohol dependent/alcohol dependence,” “abuser/abusers,” “addict/addicts,” and “alcohol use disorder/substance use disorder”) were searched within the body, abstract, and title of articles published in ACER on PMC each year. This ensured that the stigmatizing term was included in the writing of the paper itself. If an article included a term of interest, it was counted once regardless of how many times the term of interest was used. The number of articles containing a term of interest for a given year were divided by the total number of articles published in that year to determine the percent use of that term for that year.

The search for the word “alcoholism” was particularly difficult as all papers published in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research included the term of interest as it was in the title name of the journal. The “NOT” search function was unable to exclude the title name as the “Body - all words” and “Title” specification retrieved all papers published in ACER. Thus, the search of the word “alcoholism” was limited to the abstracts, which was the only field of interest that did not contain the journal title name. Though we cannot compare the use of “alcoholism” in the abstract with the use of other outdated terms searched for in the title, abstract, and body of a paper, it is still possible to draw general conclusions of the changes and continuity of inclusion of the word “alcoholism” in alcohol research by comparing the percent use of that term in abstracts throughout the years.

To verify that there was no considerable difference in the frequency of stigmatizing and outdated language appearing in papers published in ACER on PMC and the papers in ACER not on PMC, we conducted a manual search of the same terms of interest (“alcohol abuse,” “alcoholic,” “alcohol dependent,” “abuser,” “addict,” and “alcohol use disorder”) throughout the title, body, and abstract of 110 papers downloaded directly from the Wiley Online Library. We selected 10 papers at random for each year from 2010 to 2020, cross checking these papers with the PMC database to confirm that the papers selected were not publicly available on PMC. In addition, we also verified that the papers selected had external funding sources that were not directly linked to the NIH. Through this, we obtained a sample of Wiley Online Library specific papers and conducted a manual search to compare our findings with the larger sample of PMC papers.

In our search of papers in the Wiley Online Library, we also manually examined the context surrounding individual terms of interest. From this, we found instances in which pejorative or outdated words were used in non-stigmatizing ways. We determined the most common uses of the term “alcoholic” in non-stigmatizing manners (i.e., “alcoholic drink,” “alcoholic beverage,” and “Alcoholics Anonymous”) in the Wiley Online Library articles. We then determined the rates of use of those same terms with the larger PMC database. This was achieved by conducting a query to determine how many papers in the PMC subset included uses of such phrases. However, this search was unable to distinguish whether the papers that included “alcoholic drink,” “alcoholic beverage,” and “Alcoholics Anonymous” also included the word “alcoholic” in a stigmatizing manner.

RESULTS

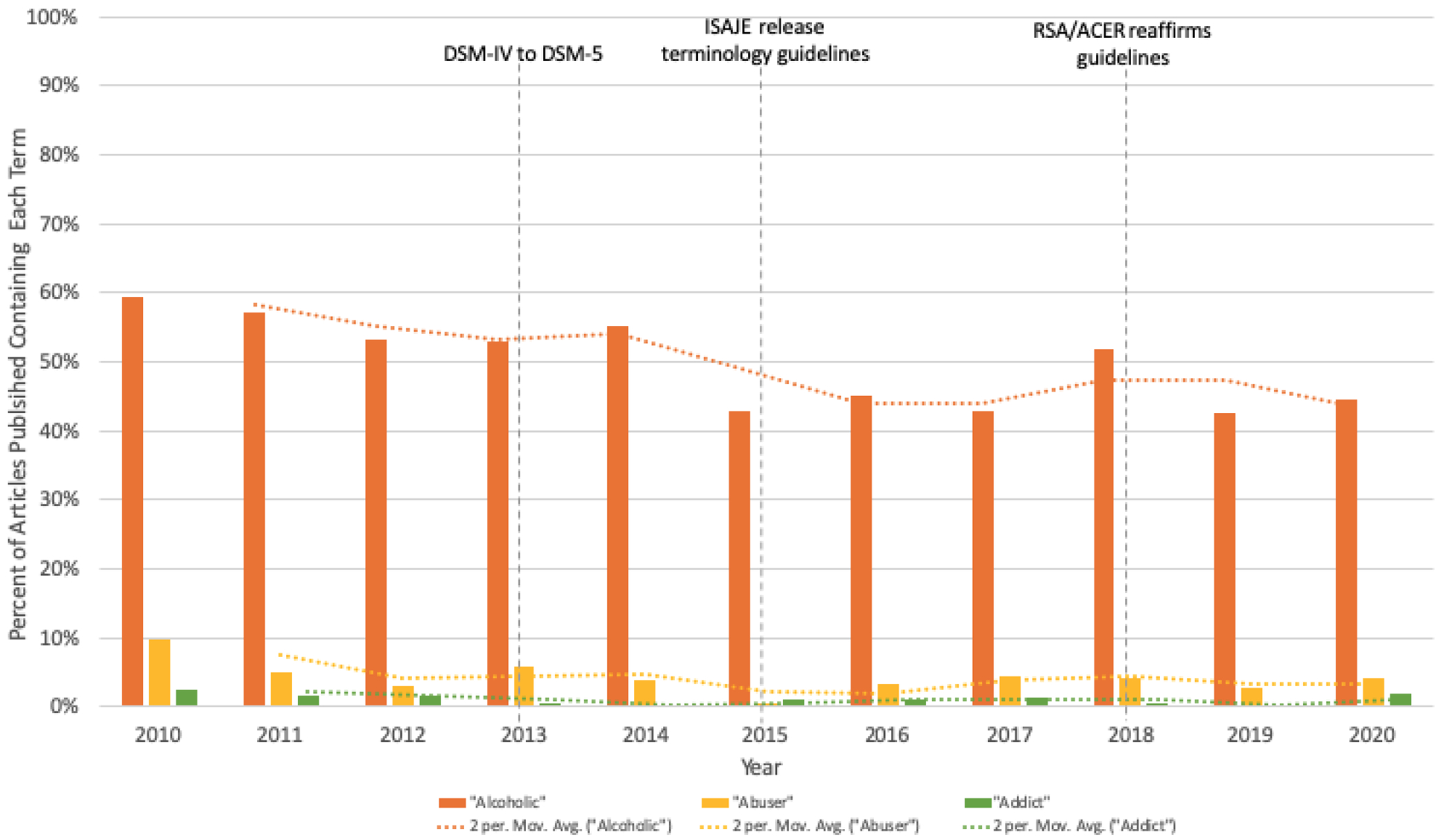

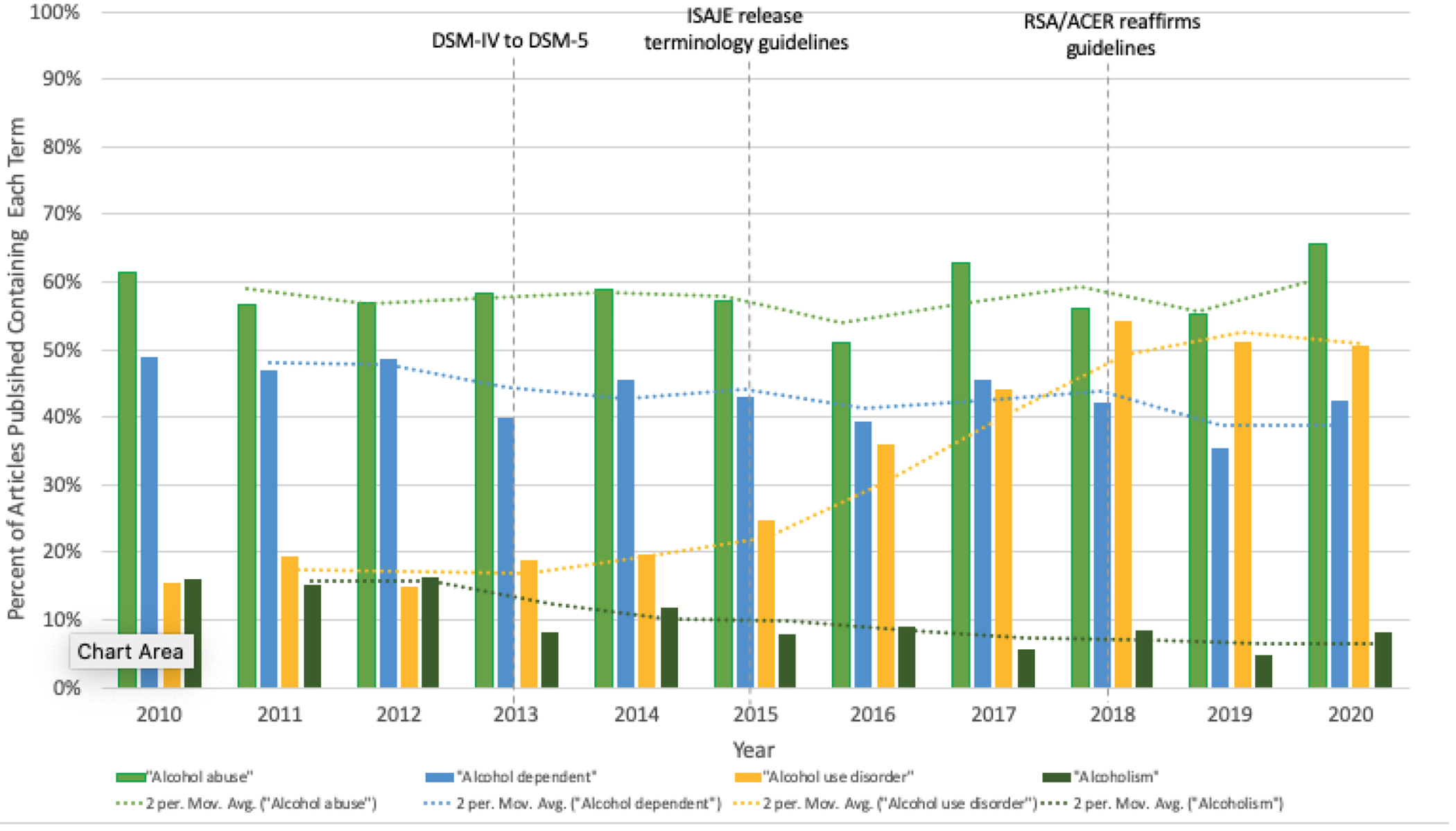

The search revealed that although the use of pejorative and outdated terminology has, for the most part, decreased over time, “alcoholic” was used in over 40% of original research and reviews (n=1903) published in ACER on PMC each year after the release of ISAJE terminology guidelines (Figure 1). The terms “abuser” and “addict” were included at low rates (≤10%) in ACER even before the release of terminology changes and recommendations. Additionally, following changes in diagnostic language in 2013, “alcohol dependent” and “alcoholism” declined in use, while “alcohol use disorder” has increased and “alcohol abuse” has remained relatively steady (Figure 2). In Figures 1 and 2, trendlines for each term of interest were displayed as two-year moving averages, which were calculated by taking the average of the percent use of a term between the previous and the current year.

Figure 1.

Stigmatizing language included in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research (ACER) articles on PubMed Central from 2010-2020. DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. ISAJE: International Society of Addiction Journal Editors. RSA: Research Society on Alcoholism.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic language included in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research (ACER) articles on PubMed Central from 2010-2020. DSM: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. ISAJE: International Society of Addiction Journal Editors. RSA: Research Society on Alcoholism.

A manual search of a randomly selected subset of papers (n=110) in ACER that were exclusively available on the Wiley Online Library confirmed that the trends in the use of stigmatizing and outdated language were similar to those found in the NIH-funded papers available on PMC. These results are included in supplemental materials. Pejorative words such as “abuser” and “addict” were included at low rates of use throughout the decade while outdated terminology such as “alcohol dependent,” “alcohol abuse,” and “alcoholism” decreased after the release of terminology changes and recommendations in 2013 and 2015. The percent use of each term was comparable to the percent use found in the PMC search, with the exception of the word “alcoholism.” The manual search through Wiley specific papers likely assessed higher rates of its use as we were able to assess the appearance of “alcoholism” in the title, abstract, and body while the PMC search was limited to the abstract. Similar to the PMC search, the use of “alcohol use disorder” increased following the DSM-5 change. Most notably, the search verified that the term “alcoholic” was included at high rates each year after the change to DSM-5 and the release of ISAJE terminology guidelines.

While assessing for context in the manual Wiley Online Library search of 110 papers, there were 11 papers that utilized the word “alcoholic drink” or “alcoholic beverage” but not “alcoholic” in reference to a person. The next most used term of interest in a non-stigmatizing manner was the inclusion of the phrase “Alcoholics Anonymous,” which appeared in 2 papers out of the 110 papers searched for. After correcting for context surrounding “alcoholic,” we found that approximately 30% of research and reviews published in ACER each year included the word “alcoholic” in a stigmatizing manner. In the Wiley Online Library search, we noticed similar trends in terminology use. In particular, for the pejorative terms of interest, “abuser” and “addict” were included in less than 5% of papers published in ACER in 2020 on both PMC and Wiley databases, while “alcoholic” was included in 40% of papers published in ACER in 2020 on PMC and in 30% of papers published in ACER in 2020 on Wiley. This analysis indicates that NIH-funded research on PMC provides an approximate representation of the general trends in language use throughout all original research and reviews published by ACER, regardless of a paper’s funding source and/or open access status. In addition, even after correcting for the individual context surrounding each word in the manual search, there were high rates of use of the word “alcoholic” in original research and reviews published on ACER in recent years. Thus, in our manual search on papers downloaded from Wiley, we were able to determine that the number of articles that use “alcoholic” in non-stigmatizing contexts is approximately 12%. Finally, of the 1093 papers published in ACER on PMC that included the word “alcoholic” from 2010-2020, 180 included “alcoholic drink” or “alcoholic beverage” and 54 included “Alcoholics Anonymous.” Thus, 16% of papers on PMC included the phrase “alcoholic drink” or “alcoholic beverage” while 5% included “Alcoholics Anonymous.”

DISCUSSION

The use of stigmatizing language within the scientific community can increase social stigma around alcohol and substance use disorders. A search of NIH-funded ACER publications available on PMC revealed that though there has been a promising decline in stigmatizing and outdated language in the last decade, such language still exists at considerable rates. The publications included in this search (n=1903) represented approximately 63% of the total articles published in ACER. We limited our search to ACER articles published on PMC as PMC published papers are easily accessible by the scientific community and the general public, and thus more capable of propagating stigma against people with alcohol use disorder. Additionally, the PMC search engine was able to distinguish search results found in the body from results found in the references. In contrast, Wiley Online Library, which contains all of the publications in ACER, does not have the option to conduct an “in article only” search. To accurately track the rates of inclusion of stigmatizing and outdated language in original research and reviews, it was important not to count articles that contained such language only in the references. Moreover, an analysis of a subset of Wiley-specific publications not included on PMC (n=110) confirmed similar results to those found in our initial PMC search, suggesting that our primary sample of NIH-funded articles available on PMC is a good representation of all research and reviews published in ACER.

Terms such as “alcoholic,” “addict,” and “abuser” may well reinforce the belief that individuals with alcohol or substance use disorder are immoral, blameworthy, and undeserving. Even trained substance use disorder and mental health clinicians were quicker to assign blame and gravitate towards punitive punishments instead of medical therapies when an individual was described as a “substance abuser” instead of a “person with a substance use disorder” (Kelly & Westerhoff, 2010). The negative opinions held by some healthcare professionals toward individuals with substance use disorder may also cause patients to feel diminished levels of empowerment, negatively impacting the delivery of care (Zwick et al., 2020). As a result, stigma surrounding substance use disorder, which arises in part by inappropriate language use, can lead to low rates of treatment seeking (Agterberg, Schubert, Overington, & Corace, 2020), as well as decreased quality of care and treatment outcomes for those affected individuals (van Boekel et al., 2013).

The main purpose of this study was to track the use of pejorative terms (such as “alcoholic,” “abuser”, and “addict”), and to examine trends of use of outdated terms (such as “alcohol abuse,” “alcohol dependence,” and “alcoholism”). While studies have clearly indicated that pejorative terms like “addict,” “abuser,” and “alcoholic” contribute to negative biases against people with alcohol use disorder (Ashford et al., 2018), less research is available that quantifies the consequences of using outdated terminology. This study revealed a decline of outdated terms (such as “alcohol dependent” and “alcoholism”) while terms introduced by DSM-5 (such as “alcohol use disorder”) increased throughout the years. However, it was difficult to trace the use of “alcohol abuse” and “alcohol dependence” immediately after the transition from DSM-IV to DSM-5 in 2013. PubMed Central specifies the year in which the article was published on its database and not the year in which the data was collected. Researchers may have collected data during the DSM-IV classification that was published after the change to DSM-5. In such instances, terms like “alcohol abuse” and “alcohol dependence” are appropriate diagnoses under the previous DSM-IV.

In addition, the use of the term “alcoholism” was challenging to determine in research published in Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. This outdated term was flagged in all ACER papers published on PMC and could not be excluded from the title and body of each article. Thus, the search for “alcoholism” was limited to only the abstract, which provides a limited comparison between the percent use of “alcoholism” and other terms. While there is less literature detailing the consequences associated with using the word “alcoholism,” the term is outdated and shares the same origin with the stigmatizing term, “alcoholic.” Consequently, we suggest updating both the title of the journal ACER and the name of the related society (i.e., Research Society on Alcoholism). One suggestion is to simply change “alcoholism” to “alcohol” in both.

Finally, the primary search on PMC did not account for the context in which these papers utilized pejorative and outdated terminology. All articles that included a term of interest were included in our analysis, even though there may exist instances in which a paper includes a word of interest in a non-stigmatizing manner (such as “alcoholic beverage” or “Alcoholics Anonymous”). The manual search of Wiley-specific papers revealed that such instances were less common (~12%) than instances in which terms were used in a stigmatizing manner (~30%). In particular, even after corrections for context, “alcoholic” was used at considerable rates in over 30% of publications in ACER each year. As such, despite the limitations detailed above, we believe that though our findings highlight generally promising trends in declining use of stigmatizing and outdated language in recent years, particularly after the 2018 release of terminology guidelines by ACER and the RSA, the field has further progress to make in reducing the use of the word “alcoholic” in original research and reviews published in ACER.

CONCLUSION

Harmful vocabulary regarding alcohol use disorder can perpetuate social stigma that disincentivizes people from seeking treatment. In a search of research and reviews in ACER published on PMC, 40% of papers still include the term “alcoholic,” while a separate manual search on Wiley Online Library suggested that approximately 30% of these papers include “alcoholic” in a stigmatizing manner. Given the continued use of pejorative language in alcohol use disorder research, it is important for the scientific community to help implement a shift away from negative labels as descriptors for people with alcohol and substance use disorders. Published, publicly accessible papers have the capacity to influence the opinions of the larger population and society as a whole. The starting point to any research should begin with appropriate terminology which can ultimately impact scientific and social conclusions regarding people with alcohol use disorder. As such, we suggest that ACER explicitly include terminology recommendations that promote the use of person first language, such as “a person with an alcohol use disorder” in its author guidelines. In doing so, we can reinforce the idea that affected individuals are deserving of compassion and care, which can dismantle stigmatizing beliefs that may discourage people from seeking or receiving mental and physical health services (Volkow, Gordon, & Koob, 2021). Furthermore, we urge authors to carefully and intentionally consider the implications of the language they include in their work and we ask reviewers to be mindful of such language use when considering a paper for publication. Reducing the stigma around alcohol use disorder and treating and managing alcohol use disorder as a medical condition will likely increase rates of treatment seeking, as well as the quality of care provided.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

This work was supported by NIH grants P01AA027473 and U54AA027989. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- Agterberg S, Schubert N, Overington L, & Corace K (2020). Treatment barriers among individuals with co-occurring substance use and mental health problems: Examining gender differences. J Subst Abuse Treat, 112, 29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcohol Use Disorder: A Comparison Between DSM–IV and DSM–5. Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/alcohol-use-disorder-comparison-between-dsm

- Ashford RD, Brown AM, & Curtis B (2018). Substance use, recovery, and linguistics: The impact of word choice on explicit and implicit bias. Drug and alcohol dependence, 189, 131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford RD, Brown AM, & Curtis B (2019). The Language of Substance Use and Recovery: Novel Use of the Go/No-Go Association Task to Measure Implicit Bias. Health communication, 34(11), 1296–1302. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2018.1481709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashford RD, Brown AM, McDaniel J, & Curtis B (2019). Biased labels: An experimental study of language and stigma among individuals in recovery and health professionals. Substance use & misuse, 54(8), 1376–1384. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2019.1581221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry CL, McGinty EE, Pescosolido BA, & Goldman HH (2014). Stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy: public views about drug addiction and mental illness. Psychiatr Serv, 65(10), 1269–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyles LM, Binswanger IA, Jenkins JA, Finnell DS, Faseru B, Cavaiola A, Pugatch M, Gordon AJ (2014). Confronting inadvertent stigma and pejorative language in addiction scholarship: a recognition and response. Substance abuse, 35(3), 217–221. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.930372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clement S, Schauman O, Graham T, Maggioni F, Evans-Lacko S, Bezborodovs N, Morgan C, Rüsch N, Brown JS, Thornicroft G. (2015). What is the impact of mental health-related stigma on help-seeking? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies. Psychol Med, 45(1), 11–27. doi: 10.1017/s0033291714000129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, Dow SJ, & Westerhoff C (2010). Does our choice of substance-related terms influence perceptions of treatment need? An empirical investigation with two commonly used terms. Journal of Drug Issues, 40(4), 805–818. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JF, & Westerhoff CM (2010). Does it matter how we refer to individuals with substance-related conditions? A randomized study of two commonly used terms. Int J Drug Policy, 21(3), 202–207. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. (2018). 2017 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. In: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Statements and Guidelines Addiction Terminology. Retrieved from https://www.isaje.net/addiction-terminology.html

- Stone R (2015). Pregnant women and substance use: fear, stigma, and barriers to care. Health & Justice, 3(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer KL, & Baker EH (2018). Stigma as a Barrier to Substance Abuse Treatment Among Those With Unmet Need: An Analysis of Parenthood and Marital Status. J Fam Issues, 39(1), 3–27. doi: 10.1177/0192513x15581659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boekel LC, Brouwers EP, van Weeghel J, & Garretsen HF (2013). Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug and alcohol dependence, 131(1-2), 23-35. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Gordon JA, & Koob GF (2021). Choosing appropriate language to reduce the stigma around mental illness and substance use disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology, 46(13), 2230–2232. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-01069-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White W (2004). The lessons of language: Historical perspectives on the rhetoric of addiction. Altering American consciousness: Essays on the history of alcohol and drug use in the United States, 33–60.

- Zwick J, Appleseth H, & Arndt S (2020). Stigma: how it affects the substance use disorder patient. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy, 15(1), 50–50. doi: 10.1186/s13011-020-00288-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.