Abstract

Background:

Evidence implicates sleep/circadian factors in alcohol use, suggesting a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving and that this rhythm may vary by individual differences in sleep factors and alcohol use frequency. This study sought to (1) replicate prior findings of a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving, and (2) examine whether individual differences in sleep timing, sleep duration, or alcohol use frequency were related to differences in the timing of the peak of the craving rhythm (i.e., the acrophase) or magnitude of fluctuation of the rhythm (i.e., amplitude). Finally, whether such associations varied by sex or racial identity was explored.

Methods:

Two-hundred fifteen adult drinkers (21–35 years of age, 72% male, 66% self-identified as White) completed a baseline assessment of alcohol use frequency and then smartphone reports of alcohol craving intensity six times a day across 10 days. Sleep timing was also recorded each morning of the 10-day period. Multilevel cosinor analysis was used to test the presence of a 24-hour rhythm and to estimate acrophase and amplitude.

Results:

Multilevel cosinor analysis revealed a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving. Individual differences in sleep timing or sleep duration did not predict rhythm acrophase or amplitude. However, alcohol use frequency moderated this rhythm wherein individuals who used alcohol more frequently in the 30 days prior to the beginning of the study had higher mean levels of craving as well as greater rhythm amplitudes (i.e., greater rhythmic fluctuations). Associations did not vary by sex or racial identity.

Conclusions:

Results support that alcohol craving exhibits a systematic rhythm over the course of the 24-day and that frequency of alcohol use may be relevant to the shape of this rhythm. Findings suggest that consideration of daily rhythms in alcohol craving may further the understanding of mechanisms driving alcohol use.

Keywords: alcohol, diurnal rhythm, circadian rhythm, sleep, ecological momentary assessment

Introduction

Alcohol misuse and problematic drinking have been identified as a source of substantial economic and health costs and consequences (Rehm et al., 2009, Charlet and Heinz, 2017). Correspondingly, reducing alcohol consumption is one way to mitigate these costs and consequences (Charlet and Heinz, 2017). The craving to drink alcohol is a substantial factor in alcohol use as it predicts future consumption of alcohol and binge drinking, and in adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD), predicts relapse into resumption of alcohol use (Schneekloth et al., 2012, Serre et al., 2018, Padovano et al., 2019, Morgenstern et al., 2016). Thus, understanding craving is critical to understanding alcohol use patterns, particularly in adolescents and young adults, which may yield insights for alcohol reduction for these individuals. One understudied factor that may aid in the understanding of craving is the extent to which its daily fluctuations may be systematic, manifesting as daily rhythmicity (i.e., cyclical fluctuations over 24 hours), which can help identify when peaks and troughs in craving are most likely to occur, as well as revealing processes that may drive such rhythmicity (e.g., timing of social/contextual factors, circadian rhythms).

24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving

Several prior studies have reported daily rhythms (or time-of-day effects suggestive of a rhythm) in craving for various drugs of abuse, including nicotine, heroin, and other opioids (Teneggi et al., 2005, Teneggi et al., 2002, Ren et al., 2009, Cleveland et al., 2021). Furthermore, preclinical evidence has demonstrated a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol consumption in alcohol-preferring mice, suggesting that both cravings and consumption of alcohol may follow a rhythm (Matson and Grahame, 2013). A 24-hour rhythm in craving may emerge because of circadian modulation of reward motivation more broadly. A circadian rhythm in reward motivation has been suggested by strong preclinical evidence of circadian modulation of reward circuitry (e.g., reviewed in Logan, Hasler, et al, 2019) and growing evidence of 24-hour rhythms in reward-related processes in humans, such as positive affect, reward activation, and wanting (Byrne and Murray, 2017, Miller et al., 2015, Murray et al., 2009, Itzhacki et al., 2019). In addition to any circadian influences, a 24-hour rhythm in craving may emerge because of the timing of social and contextual factors, such as when work hours occur and when bars are open. For instance, alcohol use increases during daytime hours in which work and schools are typically closed and when bars are open (Arfken, 1988).

While the presence of 24-hour rhythms in reward-related processesleep duration may also be relevant to any rhythm in alcohol craving given that prior work indicating that people with poor or shorter sleep have a higher craving for alcohol and drugs (Chakravorty et al., 2010, He et al., 2019, Lydon-Staley et al., 2017). In terms of individual differences in alcohol involvement, greater alcohol use and AUD is associated with circadian disruption, such as the disruption of the timing and amplitude of the melatonin rhythm (Meyrel et al., 2020, Hasler et al., 2012b, Tamura et al., 2021). Thus, to the extent that the 24-hour rhythm in alcohol is driven by circadian rhythms, greater alcohol use should be associated with altered timing or blunted amplitude of the rhythm.

Consistent with a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving that is influenced by circadian timing, we recently reported preliminary evidence from a sample of 36 late adolescent drinkers that alcohol craving exhibits a sinusoidal 24-hour rhythm in which craving, on average, peaks during evening hours (e.g., 8 pm) and has a trough in the morning (e.g., 8 am) (Hisler et al., 2021). Furthermore, our prior study identified that (1) participants with later sleep/circadian timing also have later peak alcohol craving and that (2) participants who had more drinking days over a 14-day period had a greater amplitude (i.e., larger rhythmic fluctuation) in alcohol craving. These initial findings provide support that sleep timing and alcohol use frequency may each impact the alcohol craving rhythm, but require replication given study limitations (small sample composed predominantly of White female young college students). Given prior evidence of sex and racial differences in drinking characteristics (McKone et al., 2019) and in how sleep timing and sleep duration relate to responses in alcohol (Hasler et al., 2019), it remains unclear if the findings would generalize across sex or racial identity, or to a broader adult population who are not subject to the unique restrictions, demands, and social environment of college.

Study aims and hypotheses

Overall, evidence of a circadian contribution to daily patterns in alcohol craving would have both mechanistic implications (circadian system influencing craving and thus risk for alcohol problems) and prevention/intervention implications (predicting windows of vulnerability within the 24-hour day). Investigating these questions during young adulthood is particularly salient given that alcohol use peaks during this period (Chen et al., 2004), which comes at the tail end of the period of greatest change in sleep/circadian timing (Roenneberg et al., 2004).

Accordingly, this project used data from 215 young adult drinkers who completed an ecological momentary assessment (EMA) protocol that assessed alcohol craving six times a day for 10 days in order to (1) establish whether alcohol craving exhibited a 24-hour rhythm and (2) examine whether individual differences in sleep and alcohol use frequency were associated with alterations in the rhythm timing and/or amplitude. First, we hypothesized that alcohol craving would exhibit a 24-hour rhythm. Second, consistent with the prior findings (Hisler et al., 2021), we hypothesized that later sleep timing would be associated with a later acrophase in the craving rhythm. We also hypothesized that shorter sleep duration would be associated with higher overall alcohol craving but were agnostic about whether it would be related to rhythm characteristics (acrophase or amplitude). Third, we predicted that the craving rhythm would vary as a function of alcohol use frequency (operationalized here as frequency of drinking over the past 30 days), hypothesizing that more frequent alcohol use would be associated with both higher mean craving and, consistent with our prior study, a larger amplitude in the craving rhythm. Finally, because prior findings from the analytic sample have revealed sex and racial differences in drinking characteristics (McKone et al., 2019) and in how sleep timing and sleep duration relate to responses in alcohol (Hasler et al., 2019), we also explored whether the aforementioned associations differed across sex or racial identity.

Methods

Participants

Two hundred forty-two participants were initially recruited from the local community (n = 149; recruited via posted flyers or Craigslist ads) or from the Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal study (n = 93). Study inclusion criteria required participants to be between age 21–36, to be current drinkers (drank alcohol in last month), and to have consumed in the past 6 months at least the same amount of alcohol as what would be consumed during the in-lab alcohol administration task (target BrAC of .08%). (Note that alcohol administration task is not used in this study and is therefore not described further, see (Hasler et al., 2019) for details). Participants were excluded if they were currently or had ever abstained from using alcohol for fear of having an alcohol use problem, had ever received treatment for an AUD or SUD, had a significant medical or psychiatric illness (e.g., psychotic disorders, past head injury with loss of consciousness greater than 5 minutes), were pregnant or breastfeeding, weighed over 250 pounds, or were taking medication in which alcohol is contraindicated or could affect response to alcohol. Further information regarding overarching study procedures not relevant to the current study can be found in Pedersen et al., 2021 and in funding mechanism documentation (see Funding section).

Data from 947 EMA prompts were excluded because craving was reported during or after assessments in which participants reported consuming alcohol. These data were excluded because consuming alcohol may affect the level of alcohol craving. Next, data from participants who completed less than 10% of EMA prompts were excluded (N = 27) to ensure that there was enough data to estimate a craving rhythm for a given person. After these exclusions, the final sample consisted of 215 participants who completed a total of 7,013 EMA assessments (out of 9,781 possible usable EMA assessments; 71.7% completion rate) over the study period. The sample had a mean age of 28.06 years (SD = 4.06 years, range: 21 to 35 years) and predominately self-identified as male (156 male participants, 57 female participants, 2 identified as “other” sex) and European American/White (142 European American/White, 71 African American/Black, 2 Asian or “other” racial group). 107 participants met criteria for childhood ADHD (according to both DSM-IV criteria for the community sample and as diagnosed in childhood for participants from the Pittsburgh ADHD Longitudinal study, see (Pedersen et al., 2019) for more details).

Procedures

Study procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh’s Institutional Review Board and all participants provided informed consent. Participants who met eligibility criteria after completing an initial phone screen then completed an in-lab visit in which they completed baseline questionnaires (e.g., sociodemographics, drinking characteristics) and an alcohol administration protocol. On the following Friday, participants started the 10-day EMA protocol. All participants received instructions on how to complete EMA prompts on their personal or study smartphone. Prompts were sent by text through an automated computer program. The first prompt was sent 15 minutes after self-reported typical wake-up time and the last prompt was sent 15 minutes before self-reported typical bedtime. Participants’ typical sleep and wake times were self-reported during the EMA set-up and training. They were asked to select times that most closely matched the times at which they typically woke and fell asleep. The rest of the day was then split into four equal time segments that spanned from two hours after self-reported typical wake-up time and ending two hours before self-reported typical bedtime. A prompt was then sent at a random time each day within each of these four segments. After receiving each prompt, participants had 10 minutes to complete the prompt before the response window closed. Reminder notifications were sent five minutes after each prompt was sent if the participant had not completed the prompt. Participants were compensated $110 for completing at least 80% of the assessments. If participants completed less than 80% of assessments, they were compensated in proportion of completed assessments (e.g., 60% completion received $110*.60 = $66).

Measures

Alcohol craving

Alcohol craving was assessed with the 5-item modified Brief Questionnaire of Smoking Urges that was adjusted to query alcohol (Cox et al., 2001). Participants were asked to complete each item in relation to the last 15 minutes (“I have a desire for an alcoholic drink right now”, “If it were possible, I would probably have an alcoholic drink right now”, “I have an urge for an alcoholic beverage”, “An alcoholic drink would taste good now”, “I am going to have an alcoholic drink as soon as possible”) and each item was rating on a scale ranging from “Not at all” (0) to “Very much” (3). These five items were then averaged for each EMA prompt (within-person α = .94). The number of alcohol craving assessments for each hour of the 24-hour day is presented in Supplemental Figure 1; the majority of available data were captured between 9:00 and 23:00, with less frequent responses between 0:00 and 8:00.

Individual differences in sleep timing and sleep duration

During each morning assessment, participants reported what time they fell asleep the night before (sleep onset) and what time they woke up that morning (sleep offset). To assess sleep timing, the midpoint of sleep was calculated as the halfway point between sleep onset and sleep offset. These midpoints of sleep were then averaged together to best approximate circadian timing for sleep (Reiter et al., 2020). Individual differences in sleep duration were estimated by calculating the difference in hours between sleep onset and offset for each day and then taking the average across days.

Individual differences in past 30-day alcohol use frequency

Individual differences in alcohol use frequency were assessed with a single item during the in-lab visit before starting the EMA protocol. Specifically, participants were asked “During the past 30 days, what is your best estimate of the number of days you drank one or more drinks of an alcoholic beverage?” Participants indicated 0 drinking days (0), 1–2 drinking days (1), 3–5 drinking days (2), 6–9 drinking days (3), 10–19 drinking days (4), 20–29 drinking days (5), or 30 drinking days (6).

Note that while the focus of this study was on past 30-day alcohol use frequency, information on participant past 30-day average drinks per drinking day (quantity) and past 30-day frequency of consuming 5+ drinks/occasion (coded 0 days (0), 1–2 days (1), 3–5 days (2), 6–9 days (3), 10–19 days (4), 20–29 days (5), or 30 days (6) was also obtained.

Covariates

Participant age, self-reported sex (0=male, 1=female)1, racial identity (0=European American/White, 1 = Black/African American), childhood history of ADHD diagnosis (0=no, 1=yes), currently a student (0=no, 1=yes), and currently employed (0=no, 1=yes) were used as study covariates. Note that because of the low number of other racial identities, the racial identity variable was recoded to only include and compare White and Black racial identities.

Analytic strategy

SAS Enterprise Guide 6.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to estimate a three-level multilevel 24-hour cosinor model that tested whether there is a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving (Zhang et al., 2018, Itzhacki et al., 2019). Cosinor models seek to detect whether a sinusoidal curve describes observed time-series data. This equation is f(t) = c0 + c1sin(2πt ⁄ P) + c2cos(2πt ⁄ P), with time (t) and period (P). Given that this study seeks to model a rhythm which repeats every 24-hour, P = 24 and a significant fit of sine or cosine parameters indicates the presence of a 24-hour sinusoid pattern of alcohol craving.

A three-level multilevel model was used because alcohol craving assessments were nested within days, and days were in turn nested within people. In support of using a three-level approach, there was significant variability in random intercepts (i.e., mean levels of alcohol craving) both across person (ICC=.43, σ2=.19, p<.001) and across days (ICC=.22, σ2=.10, p<.001). In addition to these random intercepts, random slopes for sine and cosine terms were added because there was significant variability across days and across people in the slopes of the sine (person-level σ2=.04, p<.001; day-level σ2=.03, p<.001) and cosine terms (person-level σ2=.02, p < .001; day-level σ2 = .07, p < .001). In other words, mean levels of alcohol craving as well as the magnitude of the sine and cosine parameters were dependent on the individual person and on the individual day and multilevel modeling was necessary to account for this non-independence. To isolate a 24-hour pattern from a linear increase throughout the day, time-of-assessment was included as a fixed-effect covariate in the multilevel models. To test whether the 24-hour rhythm varied by key individual difference variables (i.e., sleep timing, sleep duration, alcohol use frequency, sex, racial identity) each individual difference level variable was entered as a cross-level moderator of the intercept, sine, and cosine terms in separate models. In other words, each individual difference level variable was examined as a predictor of a person’s mean level of alcohol craving and as a predictor of the magnitude of a person’s sine and cosine parameters. The multilevel equations for these analyses are presented in Supplement 1.

Finally, while these analyses can inform whether a particular individual difference is associated with the degree of sinusoidal patterning in alcohol craving, the sine and cosine elements of the model are not directly interpretable as typical circadian parameters (e.g., acrophase and amplitude). Thus, to provide a more direct statistical test of what characteristics of the 24-hour rhythm (i.e., amplitude and acrophase) were related to key individual differences variables, π1pd and π2pd estimates from the multilevel model were transformed to calculate each person’s specific estimates of the acrophase and amplitude in the craving rhythm (Hasler et al., 2012a, Miller et al., 2015). Participant’s acrophase and amplitude estimates were then correlated with individual difference variables to provide a statistical test of whether a person’s acrophase or amplitude of their craving rhythm were related to individual difference variables.

Results

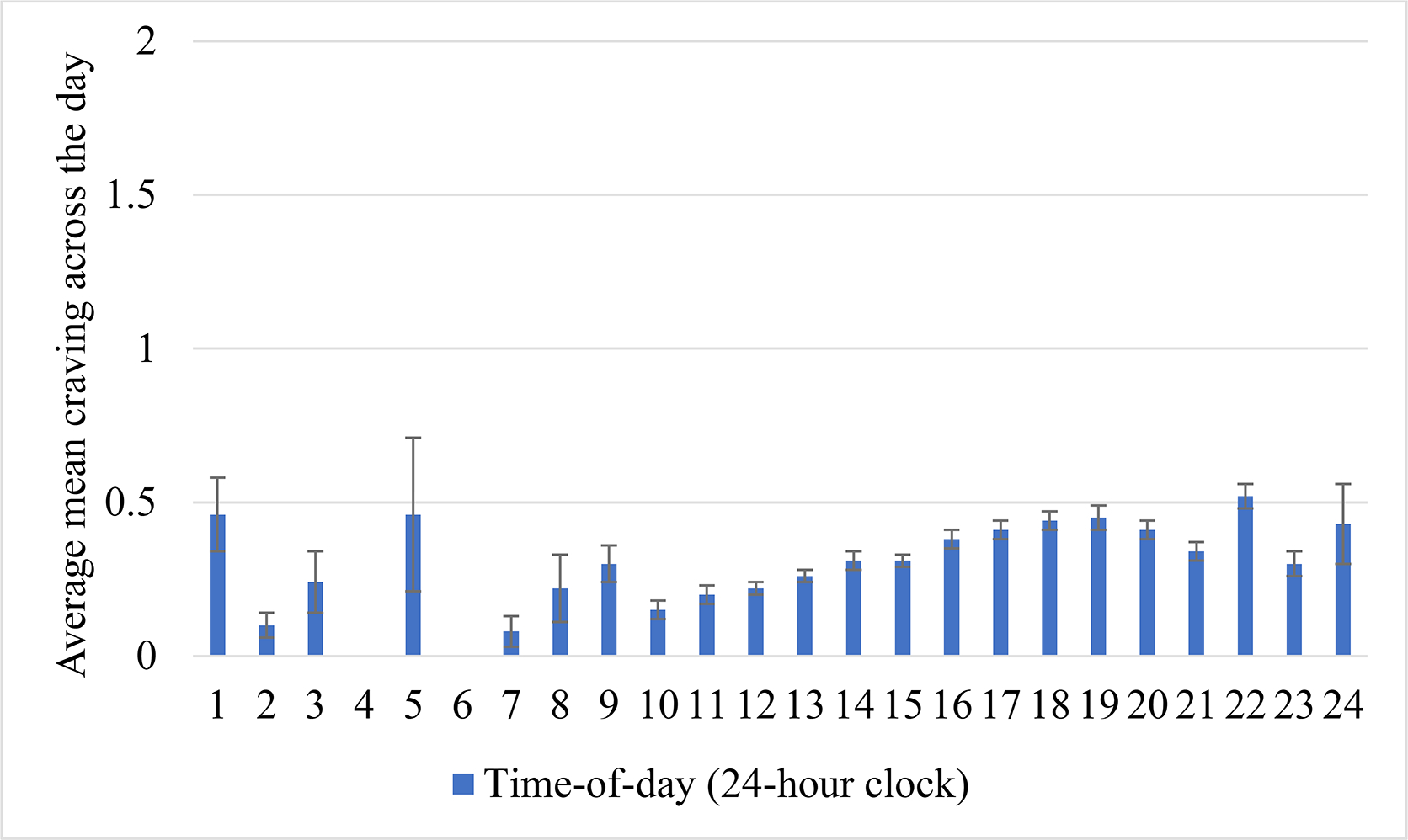

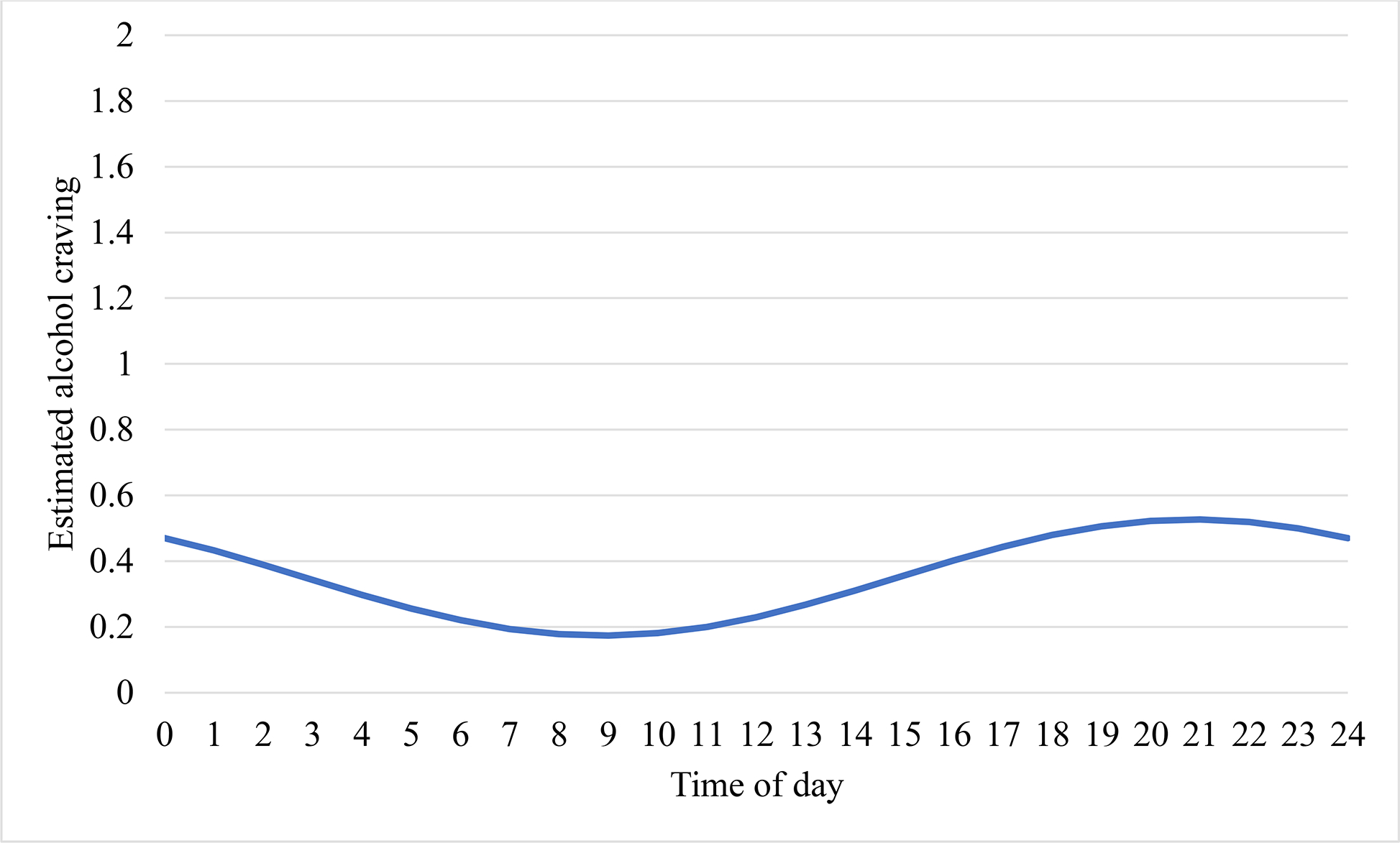

Descriptive statistics and raw correlations of key study variables are presented in Tables 1 and 2. Prior to examining the multilevel cosinor model, raw mean alcohol craving across the day was plotted in 1-hour bins across the day (see Figure 1). This raw data suggested a possible rhythm wherein alcohol craving was at its highest in the evening and its lowest in the morning. This possibility was statistically confirmed by results from the multilevel cosinor model wherein both sine and cosine terms were statistically significant (sine π=−0.13, p<0.001; cosine π=0.11, p<0.001). The estimated 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving from this model is presented in Figure 2. In this figure, alcohol craving is at its trough around 9:00 (0.17 units), and then steadily rises across the day until it reaches its peak around 21:00 (0.52 units), after which craving steadily declines to its trough at 9:00 (though note that EMA responses were the most infrequent during the hours from 0:00 to 8:00). An exploratory analysis revealed that this rhythm did not differ for weekdays vs. weekends (p=.47)

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| N | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| 1. Age | 213 | 28.06 | 4.06 |

| 2. Sex | 156 male, 57 female | ||

| 3. Racial identity | 71 Black, 142 White | ||

| 4. ADHD diagnosis | 107 diagnosed, 106 undiagnosed | ||

| 5. Occupational status | 148 employed, 46 student, 21 unemployed | ||

| 5. Person-average alcohol craving | 215 | 0.37 | 0.45 |

| 6. Midpoint of sleep (hh:mm) | 152 | 4:23 | 1:24 |

| 7. Sleep duration (hours) | 152 | 7.39 | 1.49 |

| 8. Past 30-day alcohol use frequency | 215 | 2.56 | 1.41 |

| 9. Past 30-day average drinks per drinking day | 215 | 3.53 | 2.54 |

| 10. Past 30-day number of days with 5+ drinks | 215 | 2.90 | 3.86 |

| 11. Alcohol craving amplitude | 188 | 0.32 | 0.27 |

| 12. Alcohol craving acrophase (hh:mm) | 188 | 21:00 | 4:34 |

Note. Craving scale ranges from “Not at all” (0) to “Very much” (3). Person-average alcohol craving is the person-level average calculated from all study days.

Table 2.

Correlations among person-level study variables (N = 136 – 213).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||

| 1. Age | -- | ||||||||||||

| 2. Sex | −.22* | -- | |||||||||||

| 3. Racial identity | −.04 | −.25* | -- | ||||||||||

| 4. ADHD diagnosis | .18* | −.10 | .07 | -- | |||||||||

| 5. Student status | −.49* | .11 | .14* | .19* | -- | ||||||||

| 6. Employment status | −.09 | −.09 | .30* | .05 | .18* | -- | |||||||

| 7. Person-average alcohol craving | .05 | .07 | −.11 | .08 | −.11 | −.21* | -- | ||||||

| 8. Midpoint of sleep (hh:mm) | −.11 | −.03 | −.02 | .10 | .28* | −.02 | .03 | -- | |||||

| 9. Sleep duration (hours) | −.11 | .23* | −.18* | −.03 | −.05 | −.09 | .03 | −.04 | -- | ||||

| 10. Past 30-day alcohol use frequency | −.14* | .04 | .14* | −.17* | .12 | .01 | .44* | .01 | −.06 | -- | |||

| 11. Past 30-day number of drinks per drinking day | .07 | −.09 | −.07 | .02 | .08 | −.12 | .12 | .10 | −.02 | .10 | -- | ||

| 12. Past 30-day number of days with 5+ drinks | −.14* | −.04 | −.02 | −.09 | .18* | −.02 | .44* | .17* | .06 | .53* | .45* | -- | |

| 13. Alcohol craving amplitude | .02 | −.03 | .04 | .08 | −.05 | −.06 | .56* | −.02 | .12 | .37* | −.02 | .26* | -- |

| 14. Alcohol craving acrophase (hh:mm) | −.05 | .02 | .02 | .04 | .07 | −.04 | .01 | .06 | −.07 | −.01 | .02 | .00 | −.16* |

Note. Sex (0 = male, 1 = female), racial identity (0 = White, 1 = Black), ADHD diagnosis (0 = no, 1 = yes), student status (0 = no, 1 = yes), and employment status (0 = no, 1 = yes) are binary variables. Person-average alcohol craving is the person-level average calculated from all study days.

p<.05

Figure 1.

Mean alcohol craving across 1-hour time blocks of the day. Error bars reflect standard error of the mean.

Figure 2.

Estimated 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving.

Does the rhythm in alcohol craving vary by sleep timing?

Next, the putative influence of sleep timing on the alcohol craving rhythm was examined by estimating a multilevel cosinor model in which sleep timing (i.e., average midpoint of sleep) was entered as a person-level predictor of the intercept, sine, and cosine terms of the modeled rhythm (see Supplemental Table 3). Contrary to expectations, sleep timing did not predict the intercept (B=.01, p=.81), sine (B=.00, p=.87), or cosine (B=.01, p=.62) terms. Furthermore, individual differences in sleep timing were also unrelated to individual differences in the amplitude (r=.00, p=.97) and acrophase (r=−.01, p=.88) parameters of the rhythm. These associations remained unchanged when covarying for age, sex, racial identity, and childhood ADHD diagnosis, employment status, and student status. The association of sleep timing with the alcohol craving rhythm did not vary by sex or racial identity.

Does the rhythm in alcohol craving vary by sleep duration?

Similar to sleep timing, individual differences in sleep duration did not predict the intercept (B=−.02, p=.56), sine (B=−.01, p=.47) or cosine terms (B=−.02, p=.32) when entered as a cross-level predictor in a multilevel cosinor model (see Supplemental Table 2) and was unrelated to individual differences in the amplitude (r=.11, p=.15) or acrophase (r=−.04, p=.62) of the rhythm. These associations remained unchanged when covarying for age, sex, racial identity, and childhood ADHD diagnosis, student status, and employment status. Moreover, the association of sleep duration with the alcohol craving rhythm did not vary by sex or racial identity.

Does the rhythm in alcohol craving vary by past 30-day alcohol use frequency?

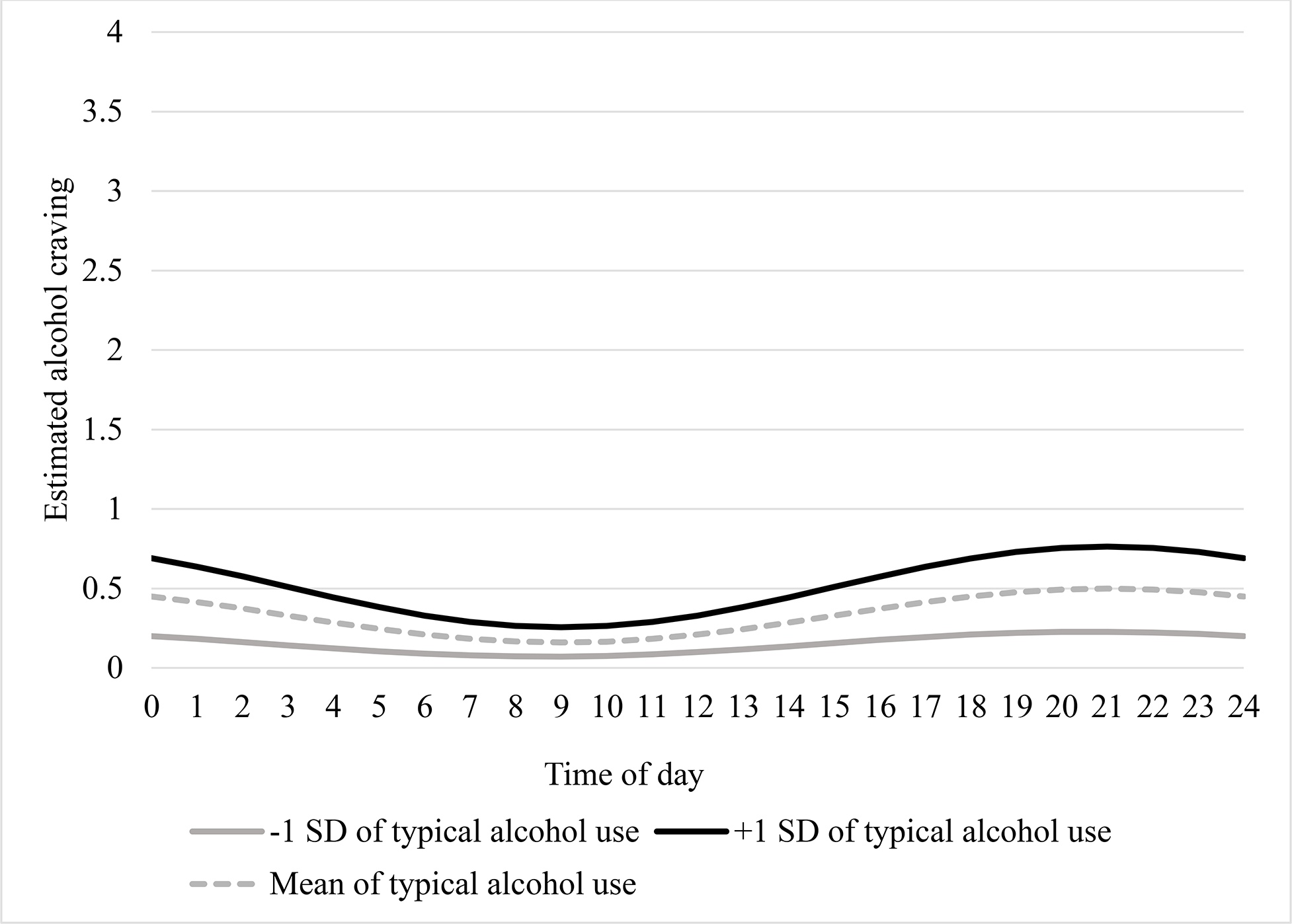

Last, whether alcohol use frequency was associated with the alcohol craving rhythm was examined by estimating a multilevel cosinor model in which alcohol use frequency was entered as a person-level predictor of the intercept, sine, and cosine terms of the modeled rhythm. Alcohol use frequency predicted the intercept (B=.18, p<.001), sine (B=−.06, p<.001), and cosine (B=.06, p<.001) terms (see Supplemental Table 3).2 Note that these associations remained statistically significant even after for accounting for age, sex, racial identity, childhood ADHD diagnosis, student status, and employment status. To interpret the influence of alcohol use frequency on the craving rhythm, the estimated alcohol craving rhythm for individuals one standard deviation above, at, and below the mean in alcohol use frequency was plotted (see Figure 3). As depicted in this figure and in support of our hypotheses, individuals with an alcohol use frequency that was 1 SD above the mean appeared to have greater craving across the entire day as well as a stronger rhythmic fluctuations in craving. Supporting this visual interpretation, individuals with greater alcohol use frequency had greater mean alcohol craving (r=.44, p<.001) and greater amplitudes in the craving rhythm (r=.37, p<.001), but did not have differing acrophases in the rhythm (r=−.01, p=.95). The association of alcohol use frequency with the alcohol craving rhythm did not vary by sex or racial identity.

Figure 3.

Estimated alcohol craving rhythm for individuals one standard deviation above, at, and below the mean of past 30-day alcohol use frequency.

Discussion

This study aimed to extend prior findings (Hisler et al., 2021) in a larger sample that is also more diverse in terms of age, sex, and racial identity. Consistent with the prior paper, we found evidence of a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving that varied in amplitude according to individual differences in alcohol use frequency. In contrast to the prior paper, individual differences in sleep characteristics (timing and duration) were not associated with differences in timing (acrophase) or amplitude of the rhythm in alcohol craving.

Our replication of a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving exhibiting roughly the same timing for the trough (average time: 8:00) and peak (average time: 20:00) as in the prior dataset (Hisler et al., 2021) supports the generalizability of a rhythm in alcohol craving. Notably, results were consistent despite sample and methodological differences (e.g., older and more diverse sample). These findings are consistent with reports of 24-hour rhythms in reward related processes (Byrne and Murray, 2017, Miller et al., 2015, Murray et al., 2009, Itzhacki et al., 2019). Taken together, the consistent evidence of a 24-hour alcohol craving rhythm with a trough ~8–9 am and a peak~8–9 pm suggests that the evening hours may be a particularly critical time window for interventions seeking to curb craving and reduce drinking. A logical next step to inform whether such a critical period is practically important will be to examine whether 24-hour rhythms in craving lead to corresponding patterns in the actual consumption of alcohol.

In contrast with our prior preliminary finding that behavioral and biological indices of sleep/circadian timing were associated with the timing of the rhythm alcohol craving rhythm (Hisler et al., 2021), we did not observe an association between individual differences in sleep timing and the alcohol craving rhythm timing in the present project. This was unexpected given prior evidence that self-reported preferences for sleep timing are associated with the timing of rhythms in positive affect (Porto et al., 2006, Miller et al., 2015, Hasler et al., 2012a, Hisler et al., 2021), consistent with the considerable evidence for circadian modulation of reward-related processes (Logan et al., 2018, Webb et al., 2015). Similarly, individual differences in sleep duration were not associated with characteristics of the craving rhythm in the present project, in contrast to evidence that sleep loss influences both craving, specifically, and reward-related and self-regulatory processes more broadly (He et al., 2019, Dorrian et al., 2019). It is possible that the natural variation in sleep duration in the present study did not include the magnitude of sleep restriction necessary to have measurable impact on craving. Our prior study employed wrist actigraphy and dim light melatonin onset to assess sleep timing, and it may be necessary to employ more objective or more proximal measures of the timing of the circadian clock to reliably detect associations between sleep timing and the craving rhythm. Further research employing such objective measures with a sufficiently large and diverse sample are needed to clarify the discrepant findings.

Consistent with predictions, and paralleling findings from the prior study (Hisler et al., 2021), individual differences in alcohol use frequency were associated with the amplitude of the rhythm in alcohol craving. An association between more frequent alcohol use and overall higher craving across the day might be expected given that craving plays a substantial role in the initiation of alcohol use and is reinforced by alcohol use (Flannery et al., 2001, Tiffany and Conklin, 2000). The novelty here is that more frequent alcohol use was associated with the rhythm of alcohol craving—a greater amplitude in the alcohol craving rhythm, or larger rhythmic fluctuation in craving. This implies that the 24-hour rhythm in craving may be a more substantial factor in alcohol craving for individuals who consume alcohol more frequently. Consideration of the craving rhythm may be important in studies and interventions targeting populations with higher alcohol consumption (e.g., populations with or at-risk for an AUD).

The replicated association between more frequent alcohol consumption and a greater amplitude in craving remains somewhat nonintuitive given evidence that both acute and chronic alcohol use is associated with circadian rhythm disturbances (e.g., in melatonin and/or core body temperature rhythms) in human studies (Tamura et al., 2021, Hasler et al., 2012b, Meyrel et al., 2020) and disturbs circadian function in animal models (Ruby et al., 2017). Disturbed circadian function would typically manifest as weaker rhythms (i.e., blunted amplitude; (Aschoff and Wever, 1981). One explanation for the unexpected finding of higher amplitude could be statistical—individuals with greater alcohol use typically experience greater craving and higher overall craving provides more variation in craving across the day, making it possible to model the sinusoidal curve (and accordingly, a higher amplitude), whereas lower craving provides less variation (from zero), making it harder to model the sinusoid (and accordingly, a lower amplitude) (Day et al., 2014, Schoenmakers and Wiers, 2010, Chakravorty et al., 2010). Additionally, prior evidence that alcohol use disrupts circadian rhythms mostly relies on markers (e.g., melatonin, core body temperature) of the central circadian clock (i.e., the suprachiasmatic nucleus) (Hasler et al., 2012b, Tamura et al., 2021), but such markers do not necessarily reflect the timing of circadian rhythms in cells throughout the rest of the brain and periphery (Mohawk et al., 2012), including in brain areas underlying reward function (Logan et al., 2018, Webb et al., 2015). Future studies will need to include measures of both the central and peripheral clocks to determine whether the 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving reflects the central clock and/or more localized rhythms in reward circuitry, and to what extent alcohol use may be impacting rhythmicity at either level.

Limitations

While this study offers several strengths, there are limitations that should be noted. First, all assessments in this study are self-reports and therefore findings are subject to the limitations of self-report methodology. Second, is the limited ability to assess alcohol craving during nighttime and early morning hours when people are typically sleeping. Most alcohol craving assessments occurred between 9:00 and 23:00 (see Supplemental Figure 1) and therefore the rhythm in craving is most accurately estimated during those hours. Furthermore, while restricting craving data to those collected prior to drinking reduced the confounds of alcohol consumption on craving, it also reduced available data later in the evening. Future studies with experimentally-imposed sleep schedules would be needed to better assess the rhythmicity in craving during hours people are typically asleep. Third, the alcohol craving assessment was adapted from a smoking craving questionnaire. While presumably its validity would extend to alcohol, this questionnaire has not been directly validated for the assessment of alcohol craving. However, note that prior EMA studies examining alcohol craving frequently use a single craving item (e.g., Ramirez & Miranda, 2014; Miranda et al., 2008; Ray et al., 2010), thus the 5-item smoking urges questionnaire was adapted to alcohol craving in this study to enhance coverage of the craving construct. Fourth, this study did not examine the influence of other time-varying processes that covary with craving, such as stress (Pedersen et al., 2021). Examining the daily patterns in stress in relation to rhythm in alcohol craving is an important next step that could elucidate pathways between daily life factors, alcohol craving, and alcohol consumption. Finally, the present methods cannot disentangle sociocultural from endogenous contributors to the rhythmicity, which would require costly and burdensome laboratory-based protocols such as constant routine or forced desynchrony. The present evidence of a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving suggests such protocols may be worth the investment.

Conclusion

These findings extend and replicate the presence of a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving with a peak in alcohol craving around 20:00. In contrast to predictions, individual differences in sleep timing and duration did not moderate the craving rhythm and further research with more robust sleep measures is needed the elucidate these potential associations. Consistent with prior findings, individuals with more frequent alcohol use had greater overall craving and greater rhythmic fluctuations in craving, suggesting that the consideration of the daily rhythms in alcohol craving may help further the understanding of mechanisms driving alcohol use, as well as yield potentially actionable insights for alcohol use interventions. Finally, although associations did not vary across sex or racial identity of participants in this study, additional research with a larger sample of female individuals and racial identities beyond Black and White individuals is needed.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA): K01AA021135, R01AA026249, R37AA011873, K21AA000202; the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) R01 DA012414, R01 DA044143 and the ABMRF/The Foundation for Alcohol Research.

Footnotes

The two participants who reported sex as “other” and racial identity as “Asian American” were excluded from analyses using covariates given the low frequency of participants who endorsed this category.

Exploratory analyses suggested by a reviewer using the past 30-day average number of drinks per drinking day and past 30-day number of days with 5+ drinks as predictors of the alcohol craving rhythm are reported in supplemental tables 4 & 5. These analyses revealed that the past 30-day average number of drinks per drinking day did not influence the alcohol craving rhythm but the past 30-day number of days with 5+ drinks did. The past 30-day number of days in which 5+ drinks were consumed produced the same influence on the alcohol craving rhythm as past 30-day alcohol use frequency (see Supplemental Figure 2).

References

- ARFKEN CL 1988. Temporal pattern of alcohol consumption in the United States. Alcohol Clin Exp Res, 12, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASCHOFF J & WEVER R 1981. The circadian system of man. Biological rhythms. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- BYRNE JEM & MURRAY G 2017. Diurnal rhythms in psychological reward functioning in healthy young men: ‘Wanting’, liking, and learning. Chronobiology International, 34, 287–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAKRAVORTY S, KUNA ST, ZAHARAKIS N, O’BRIEN CP, KAMPMAN KM & OSLIN D 2010. Covariates of craving in actively drinking alcoholics. The American journal on addictions, 19, 450–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHARLET K & HEINZ A 2017. Harm reduction-a systematic review on effects of alcohol reduction on physical and mental symptoms. Addict Biol, 22, 1119–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN CM, DUFOUR MC & YI H-Y 2004. Alcohol consumption among young adults ages 18–24 in the United States: Results from the 2001–2002 NESARC survey. Alcohol Research & Health, 28, 269. [Google Scholar]

- CLEVELAND HH, KNAPP KS, BRICK TR, RUSSELL MA, GAJOS JM & BUNCE SC 2021. Effectiveness and Utility of Mobile Device Assessment of Subjective Craving during Residential Opioid Dependence Treatment. Substance Use & Misuse, 1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COX LS, TIFFANY ST & CHRISTEN AG 2001. Evaluation of the brief questionnaire of smoking urges (QSU-brief) in laboratory and clinical settings. Nicotine & tobacco research, 3, 7–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAY AM, CELIO MA, LISMAN SA & SPEAR LP 2014. Gender, history of alcohol use and number of drinks consumed predict craving among drinkers in a field setting. Addictive Behaviors, 39, 354–357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DORRIAN J, CENTOFANTI S, SMITH A & MCDERMOTT KD 2019. Chapter 4 - Self-regulation and social behavior during sleep deprivation. In: VAN DONGEN HPA, WHITNEY P, HINSON JM, HONN KA & CHEE MWL (eds.) Progress in Brain Research. Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FLANNERY BA, ROBERTS AJ, COONEY N, SWIFT RM, ANTON RF & ROHSENOW DJ 2001. The role of craving in alcohol use, dependence, and treatment. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 25, 299–308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASLER BP, GERMAIN A, NOFZINGER EA, KUPFER DJ, KRAFTY RT, ROTHENBERGER SD, JAMES JA, BI W & BUYSSE DJ 2012a. Chronotype and diurnal patterns of positive affect and affective neural circuitry in primary insomnia. Journal of Sleep Research, 21, 515–526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASLER BP, SMITH LJ, COUSINS JC & BOOTZIN RR 2012b. Circadian rhythms, sleep, and substance abuse. Sleep Medicine Reviews, 16, 67–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASLER BP, WALLACE ML, WHITE SJ, MOLINA BS & PEDERSEN SL 2019. Preliminary Evidence That Real World Sleep Timing and Duration are Associated With Laboratory-Assessed Alcohol Response. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43, 1575–1584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HE S, BROOKS AT, KAMPMAN KM & CHAKRAVORTY S 2019. The Relationship between Alcohol Craving and Insomnia Symptoms in Alcohol-Dependent Individuals. Alcohol and Alcoholism, 54, 287–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HISLER GC, ROTHENBERGER SD, CLARK DB & HASLER BP 2021. Is there a 24-hour rhythm in alcohol craving and does it vary by sleep/circadian timing? Chronobiology International, 38, 109–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITZHACKI J, TE LINDERT BHW, VAN DER MEIJDEN WP, KRINGELBACH ML, MENDOZA J & VAN SOMEREN EJW 2019. Environmental light and time of day modulate subjective liking and wanting. Emotion, 19, 10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOGAN RW, HASLER BP, FORBES EE, FRANZEN PL, TORREGROSSA MM, HUANG YH, BUYSSE DJ, CLARK DB & MCCLUNG CA 2018. Impact of Sleep and Circadian Rhythms on Addiction Vulnerability in Adolescents. Biological Psychiatry, 83, 987–996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LYDON-STALEY DM, CLEVELAND HH, HUHN AS, CLEVELAND MJ, HARRIS J, STANKOSKI D, DENEKE E, MEYER RE & BUNCE SC 2017. Daily sleep quality affects drug craving, partially through indirect associations with positive affect, in patients in treatment for nonmedical use of prescription drugs. Addictive Behaviors, 65, 275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATSON LM & GRAHAME NJ 2013. Pharmacologically relevant intake during chronic, free-choice drinking rhythms in selectively bred high alcohol-preferring mice. Addiction biology, 18, 921–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKONE KM, KENNEDY TM, PIASECKI TM, MOLINA BS & PEDERSEN SL 2019. In-the-Moment Drinking Characteristics: An Examination Across Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder History and Race. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 43, 1273–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MEYREL M, ROLLAND B & GEOFFROY PA 2020. Alterations in circadian rhythms following alcohol use: A systematic review. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 99, 109831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MILLER MA, ROTHENBERGER SD, HASLER BP, DONOFRY SD, WONG PM, MANUCK SB, KAMARCK TW & ROECKLEIN KA 2015. Chronotype predicts positive affect rhythms measured by ecological momentary assessment. Chronobiology International, 32, 376–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda R Jr, MacKillop J, Monti PM, Rohsenow DJ, Tidey J, Gwaltney C, Swift R, Ray L, McGeary J (2008) Effects of topiramate on urge to drink and the subjective effects of alcohol: a preliminary lab study. Alcohol Clin Exp 32:489–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHAWK JA, GREEN CB & TAKAHASHI JS 2012. Central and peripheral circadian clocks in mammals. Annual review of neuroscience, 35, 445–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORGENSTERN M, DIFRANZA JR, WELLMAN RJ, SARGENT JD & HANEWINKEL R 2016. Relationship between early symptoms of alcohol craving and binge drinking 2.5 years later. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 160, 183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURRAY G, NICHOLAS CL, KLEIMAN J, DWYER R, CARRINGTON MJ, ALLEN NB & TRINDER J 2009. Nature’s clocks and human mood: The circadian system modulates reward motivation. Emotion, 9, 705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PADOVANO HT, JANSSEN T, EMERY NN, CARPENTER RW & MIRANDA R 2019. Risk-taking propensity, affect, and alcohol craving in adolescents’ daily lives. Substance Use & Misuse, 54, 2218–2228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEDERSEN SL, KENNEDY TM, HOLMES J & MOLINA BS 2021. Momentary associations between stress and alcohol craving in the naturalistic environment: differential associations for Black and White young adults. Addiction. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEDERSEN SL, KING KM, LOUIE KA, FOURNIER JC & MOLINA BS 2019. Momentary fluctuations in impulsivity domains: Associations with a history of childhood ADHD, heavy alcohol use, and alcohol problems. Drug and alcohol dependence, 205, 107683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PORTO R, DUARTE L & MENNA-BARRETO L 2006. Circadian variation of mood: comparison between different chronotypes. Biological Rhythm Research, 37, 425–431. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez J, Miranda R Alcohol craving in adolescents: bridging the laboratory and natural environment. Psychopharmacology 231, 1841–1851 (2014). 10.1007/s00213-013-3372-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray LA, Miranda R Jr, Tidey JW, McGeary JE, MacKillop J, Gwaltney CJ, Rohsenow DJ, Swift RM, Monti PM (2010) Polymorphisms of the mu-opioid receptor and dopamine D4 receptor genes and subjective responses to alcohol in the natural environment. J Abnorm Psychol 119:115–125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REHM J, MATHERS C, POPOVA S, THAVORNCHAROENSAP M, TEERAWATTANANON Y & PATRA J 2009. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. The Lancet, 373, 2223–2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REITER AM, SARGENT C & ROACH GD 2020. Finding DLMO: estimating dim light melatonin onset from sleep markers derived from questionnaires, diaries and actigraphy. Chronobiology International, 37, 1412–1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REN Z-Y, ZHANG X-L, LIU Y, ZHAO L-Y, SHI J, BAO Y, ZHANG XY, KOSTEN TR & LU L 2009. Diurnal variation in cue-induced responses among protracted abstinent heroin users. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 91, 468–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROENNEBERG T, KUEHNLE T, PRAMSTALLER PP, RICKEN J, HAVEL M, GUTH A & MERROW M 2004. A marker for the end of adolescence. Current biology, 14, R1038–R1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RUBY CL, PALMER KN, ZHANG J, RISINGER MO, BUTKOWSKI MA & SWARTZWELDER HS 2017. Differential sensitivity to ethanol-induced circadian rhythm disruption in adolescent and adult mice. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 41, 187–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHNEEKLOTH TD, BIERNACKA JM, HALL-FLAVIN DK, KARPYAK VM, FRYE MA, LOUKIANOVA LL, STEVENS SR, DREWS MS, GESKE JR & MRAZEK DA 2012. Alcohol Craving as a Predictor of Relapse. Am J Addict, 21, S20–S26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHOENMAKERS T & WIERS R 2010. Craving and attentional bias respond differently to alcohol priming: a field study in the pub. European Addiction Research, 16, 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SERRE F, FATSEAS M, DENIS C, SWENDSEN J & AURIACOMBE M 2018. Predictors of craving and substance use among patients with alcohol, tobacco, cannabis or opiate addictions: Commonalities and specificities across substances. Addictive Behaviors, 83, 123–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAMURA EK, OLIVEIRA-SILVA KS, FERREIRA-MORAES FA, MARINHO EA & GUERRERO-VARGAS NN 2021. Circadian rhythms and substance use disorders: a bidirectional relationship. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 173105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TENEGGI V, TIFFANY ST, SQUASSANTE L, MILLERI S, ZIVIANI L & BYE A 2002. Smokers deprived of cigarettes for 72 h: effect of nicotine patches on craving and withdrawal. Psychopharmacol, 164, 177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TENEGGI V, TIFFANY ST, SQUASSANTE L, MILLERI S, ZIVIANI L & BYE A 2005. Effect of sustained-release (SR) bupropion on craving and withdrawal in smokers deprived of cigarettes for 72 h. Psychopharmacol, 183, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TIFFANY ST & CONKLIN CA 2000. A cognitive processing model of alcohol craving and compulsive alcohol use. Addiction, 95, 145–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEBB IC, LEHMAN MN & COOLEN LM 2015. Diurnal and circadian regulation of reward-related neurophysiology and behavior. Physiology & Behavior, 143, 58–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHANG C, SMOLDERS KCHJ, LAKENS D & IJSSELSTEIJN WA 2018. Two experience sampling studies examining the variation of self-control capacity and its relationship with core affect in daily life. J Res Pers, 74, 102–113. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.