Abstract

Ischemic heart disease and stroke are the #1 and #2 causes of death worldwide, respectively. A lifelong commitment to exercise reduces the risk of these adverse events and is also associated with several cardiometabolic improvements, including reductions in blood pressure, cholesterol and inflammatory markers, as well as improved glucose control. Routine exercise also reduces the risk of developing comorbidities that increase the risk of cardiovascular and/or cerebrovascular disease. While the benefits of a lifelong commitment to exercise are well documented, there is a complex interaction between exercise and stroke risk, such that the risk of ischemic and/or hemorrhagic stroke may increase acutely during or immediately following exercise. In this article, we discuss the physiologic responses to different types of exercise, as well as the determinants of resting and exertional cerebrovascular perfusion, and explore the complex interaction between atrial fibrillation, exercise and stroke risk. Finally, we highlight the increased risk of stroke during different types of exercise as well as factors that may alleviate this risk.

INTRODUCTION

Globally, stroke ranks as the second most common cause of death, superseded only by ischemic heart disease.1 On average, every 40 seconds, someone in the United States suffers from a stroke, and every four minutes, someone dies from cerebrovascular disease. Because of statistics such as these, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services launched the Million Hearts Collaboration in 2015 with the overall goal of reducing the number of heart attacks and strokes by 1 million by the year 2022. This ambitious goal relies on collaborations between local, state, and national government entities to implement and promote a number of healthy lifestyle choices including: reduction of sodium intake and tobacco products; increase in physical activity for the American population as a whole; as well as participation in cardiac rehabilitation for eligible patients. Indeed, routine exercise is recognized by organizations such as the American Stroke Association, American Heart Association, Department of Health and Human Services, and the United States Preventive Services Task Force, as a mainstay of therapy for primary and secondary prevention of cerebrovascular and cardiovascular disease.

A lifelong commitment to exercise clearly reduces risk of these adverse events and is associated with a number of cardiometabolic improvements. Nevertheless, the hemodynamic response to exercise – and downstream effects on dependent organs such as the brain, are highly complex, and depend on the type of exercise performed. Historically, it was thought that cerebral perfusion was relatively stable and unaffected by exercise. However, it is now recognized that there are multiple determinants of cerebral blood flow (CBF) during exercise, including local and systemic metabolic byproducts of exercise, sympathetic tone, and to some extent, cardiac output and blood pressure. Further, there is a risk of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke during and shortly after any acute bout of exercise, the risk of which varies according to the type, duration, and intensity of exercise. Therefore, it is important to understand the metabolic and hemodynamic responses to exercise, and the downstream effects on end-organ function, including the brain.

CLASSIFICATION OF DIFFERENT TYPES OF EXERCISE

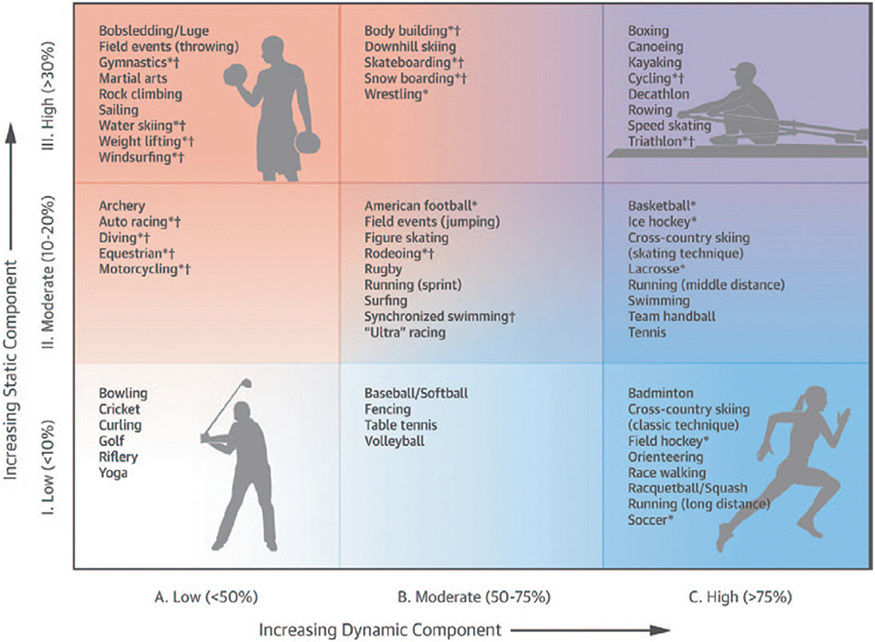

The hemodynamic response to exercise – including changes in blood pressure (BP), cardiac output (Qc) and hence, perfusion of dependent organs including the brain – varies according to the type of activity being performed (Figure 1).2, 3 Sports are generally stratified according to the intensity of endurance and strength that is necessary to sustain the activity. The endurance – or “dynamic” component of exercise, refers to the intensity of exercise as a proportion of an individual’s maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max).4 The strength – or “static” component of exercise, depends on the intensity of static muscle contractions undertaken, as a proportion of an individual’s maximal voluntary contraction. Different sports and exercise types are categorized based on these factors for two reasons: First, the acute hemodynamic responses to static and dynamic exercise are different; Second, cardiac remodeling – ie, chronic changes in heart structure and function that occur in response to long-term participation in sports, differs according to the type of sport and the hemodynamic demands placed on the cardiovascular system.4-6

Figure 1.

The classification of different sports/exercises is based on the relative contribution of static v. dynamic exercise intensity. Reprinted from Levine et al2 with permission. Copyright ©2015, the American Heart Association, Inc. and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Reprinted from Mitchell et al3 with permission. Copyright ©2005, the American College of Cardiology Foundation.

While mean arterial pressure (MAP), the product of cardiac output (Qc) and total peripheral resistance (TPR), increases during both dynamic and static exercise, the determinants of blood pressure – and the overall hemodynamic response – vary dramatically according to the type of exercise undertaken.7-9 Dynamic exercise such as running or cycling, is associated with a reduction in TPR due to peripheral vasodilatation at exercising muscle beds to accommodate increases in blood flow necessary to meet metabolic demand. Qc increases in proportion to the degree of increase in VO2, generally by 5-6 L/min for every 1L/min increase in VO2.10, 11 This Qc:VO2 relationship is generally an inviolate principle of exercise physiology across the spectrum of age, gender, health and disease, except perhaps for patients with severe heart failure, where the relationship is blunted due to reductions in contractile reserve of the failing left ventricle.7 This increase in Qc offsets the reduction in TPR such that MAP increases above resting values during dynamic exercise. During static exercise, systolic and diastolic blood pressure rise rapidly during muscle contraction as a result of mechanical compression of blood vessels, the exercise presser reflex and Valsalva response.9 The larger the muscle mass that is incorporated into exercise, the greater the increase in BP12-14, and in extreme cases, systolic blood pressure may increase to 300-400mmHg.9 These factors increase left ventricular afterload, which prevents any meaningful increase in stroke volume during static exercise.15 For that reason, increases in Qc during static exercise, are modest and are driven primarily by an increase in heart rate.15 Thus, static exercise imputes a large pressure load on the cardiovascular system, in stark contrast to dynamic exercise, which confers a large volume load, with very different hemodynamic responses.

FACTORS INFLUENCING CEREBROVASCULAR PERFUSION DURING EXERCISE

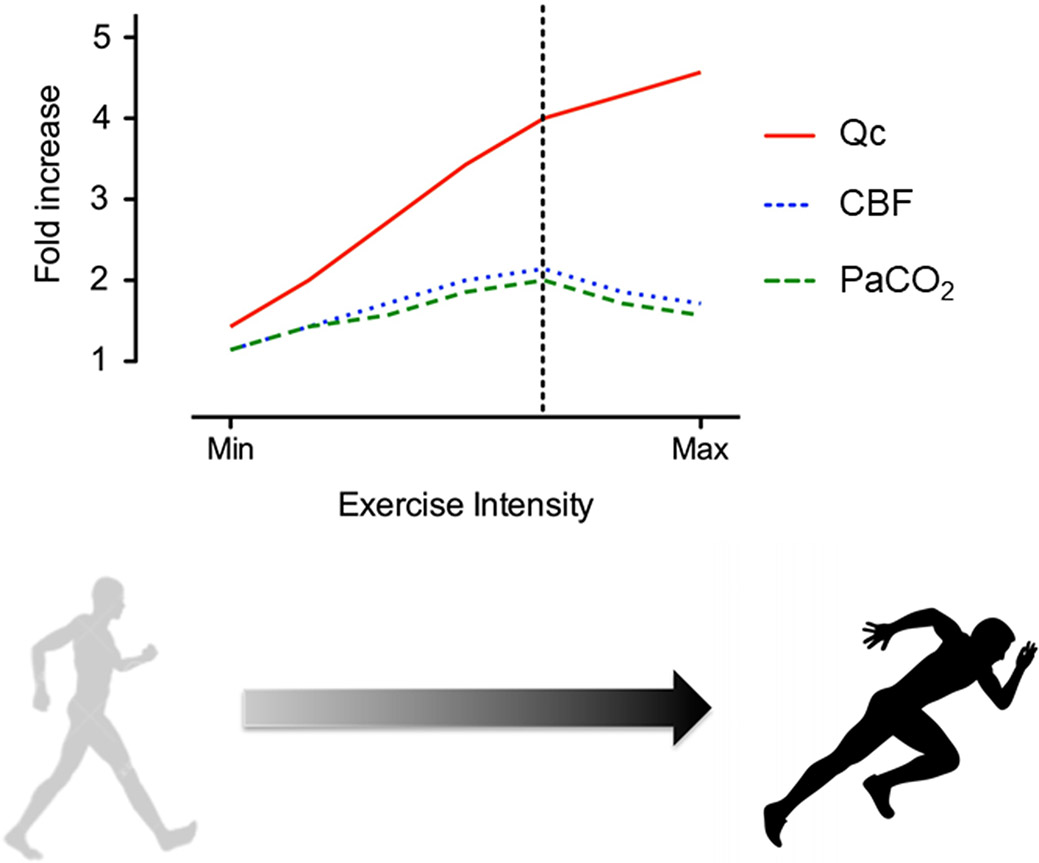

Traditionally, it was assumed that cerebral blood flow (CBF) is relatively unaffected by exercise and is maintained at a relatively constant rate of approximately 50-60ml per 100g/min.16 However, it is now recognized that there are a variety of factors that determine CBF at rest and during exercise (Figure 2).17 Under resting conditions, CBF is exquisitely sensitive to the partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2), typically increasing by 3-5% for each one mmHg rise in PaCO2, and decreasing by 1-3% for each one mmHg reduction in PaCO2.18 CBF is coupled to cerebral metabolism – as determined by the exchange of oxygen, glucose, and lactate across the cerebral vascular bed, and up- or downward changes in CBF occur in response to increases or decreases in neuronal activity, such as occurs during exercise. The change in CBF that occurs during exercise may involve biphasic components (Figure 2).17 Generally, CBF increases during submaximal exercise in concert with exercise intensity. However, as the ventilatory threshold is exceeded (typically around 60-70% of maximal oxygen uptake depending on an individual’s level of fitness), cerebral perfusion may plateau, or actually decline as a result of hyperventilation-induced hypocapnia (Figure 3).17, 19-21 Despite multiple variables that contribute to overall cerebral perfusion, PaCO2 is the primary determinant of CBF during incremental exercise. This finding has been nicely demonstrated through elegant physiology studies involving forced/artificial increases in PaCO2 – achieved by CO2 clamping, which led to increases in CBF during exercise above values obtained during exercise under .22, 23 For example, one study monitored middle cerebral arterial velocity (MCAV) among cyclists during two exercise tests – one as a control and another with end-tidal carbon dioxide levels (ETCO2) clamped and held constant by a rebreathing circuit.22 ETCO2 at peak workload above ventilatory threshold was significantly greater during clamped v. control exercise tests (39.7±5.2 v. 29.6±4.7mmHg, P<0.01), and MCAV was significantly greater in clamped v. control test (92.6±15.9 v. 73.6±12.5cm/sec, P<0.01).22

Figure 2.

Changes in cardiac output (CO), cerebral blood flow (CBF), and partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) in response to progressive increase in exercise intensity. Vertical dashed line indicates ventilatory threshold.

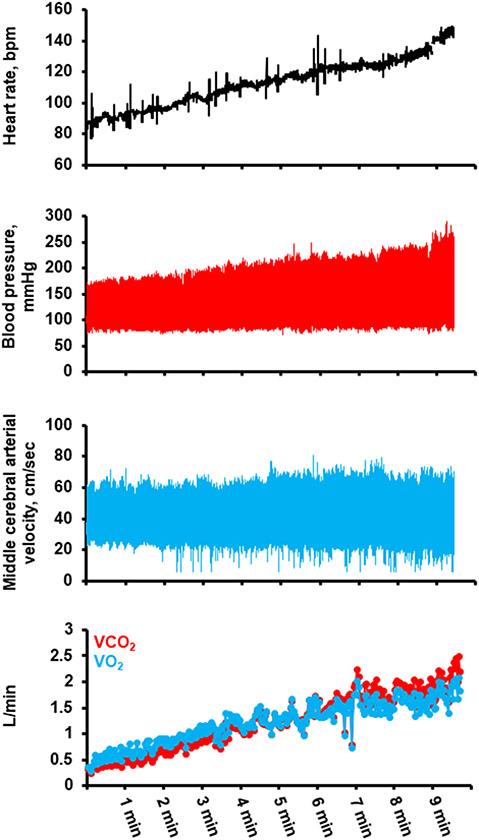

Figure 3.

Hemodynamic response to exercise in a 59yo healthy male during cardiopulmonary exercise test during stationary upright cycle ergometery, demonstrating initial increase in middle cerebral arterial velocity during exercise, followed by leveling off and eventual reduction in velocity during exercise above ventilatory threshold. Blood presure obtained from radial arterial catheterization. Middle cerebral arterial velocity obtained from transcranial Doppler during exercise. Gas exchange parameters obtained by breath-by-breath indirect calorimetry. Unpublished data from senior author (clinicaltrials.gov # NCT03232736).

The direct contribution of BP to CBF during exercise is difficult to discern.17 During dynamic exercise, BP may increase by 30% or more from rest to peak exercise, but the aforementioned leveling off and/or reduction of CBF above ventilatory threshold clearly indicates that BP in and of itself is not the primary driver of cerebral perfusion during dynamic exercise, particularly at workloads above ventilatory threshold.17 However, for static exercise, sudden contraction of large muscle groups may cause rapid increases in BP, leading to an acute and large increase in CBF.24 Cerebral autoregulatory processes operate over a period of several seconds, meaning that cerebrovascular resistance vessels cannot immediately buffer acute, large oscillations in BP that occur during static exercise.25, 26 Thus, exercise that incorporates large muscle groups may lead to transient but large increases in CBF. For example, when healthy individuals performed high-resistance exercise with lower extremity leg press, MCAV changed directly in response to fluctuations in MAP.24 This observation indicates that sudden large increases in MAP are directly transmitted to the cerebral vasculature, leading to large increases in CBF before autoregulatory processes are engaged.24 Similar findings were observed when healthy rowers performed repetitive ergometry rowing while MCAV and blood pressure were continuously monitored.27 Both MAP (86±6 to 97±6mmHg) and MCAV (57±3 to 67±5cm/sec) fluctuated in a sinusoidal pattern from rest to peak force applied to the oars with repetitive rowing motion.27 These observations indicate that large acute changes in BP occurring particularly during highly static exercises may lead to sudden increases in CBF, which raises concerns on the safety of these types of exercises for individuals in whom cerebral autoregulation is impaired, and/or have pre-existing hypertension and are at risk of unsafe increases in BP during activity.17

Qc in and of itself, does not appear to play a significant role in determining CBF during exercise. Observed increases in CBF during incremental exercise tests are modest compared to the three to five-fold increases in Qc from rest to peak effort during dynamic exercises, that are observed among healthy individuals.17 Further, the plateau, and in some cases, decline of CBF at workload above the ventilatory threshold – despite ongoing increases in Qc, suggest that during exercise, the majority of Qc is distributed to exercising muscle in a supply-demand fashion.17 Thus, changes in Qc do not appear to be the predominant factor that determines CBF during exercise. This observation is perhaps best illustrated by analysis of the cerebrovascular response to exercise among individuals who have received a heart transplantation.28 Because the heart is denervated in transplant recipients, the heart-rate response to exercise is blunted compared to controls.29 While stroke volume increases in the transplanted heart29, 30, the overall increase in Qc during exercise is blunted, with an approximate two-fold increase from rest to peak exercise29, compared to three- to five-fold increases that are typical of healthy individuals.7 Despite those differences, increases in MCAV among heart transplant recipients are similar to levels achieved among age-matched controls (MCAV at peak exercise: 45±11 v. 53±8cm/sec for transplant patients v. controls, respectively).28

CEREBROVASCULAR AND CARDIOMETABOLIC BENEFITS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY

A lifelong commitment to physical activity has been shown to reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke and all-cause mortality.1, 31, 32 Several cardiometabolic improvements occur as well, including reductions in BP in a dose-dependent fashion33, as well as improvements in lipid profile33, 34, a reduction in inflammatory markers35, and improved glucose control and insulin sensitivity.1 In a long-term follow-up study of veterans, for each 1-unit increase in fitness, as measured by peak metabolic equivalent (MET) achieved on exercise stress testing, the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality declined by 12%, and when compared to the least-fit individuals (defined as ≤4 METS), the mortality risk was 38% lower for individuals who achieved 5.1-6.0 METS and 61% lower for individuals who achieved > 9 METS.31 In the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study, low cardiorespiratory fitness was associated with a greater risk of cardiovascular-related death over 30-years of follow-up.32 Given the overwhelming evidence of the benefits associated with a commitment to lifelong exercise, the Department of Health and Human Services36, as well as the American Heart Association, recommend that adults engage in at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity, or 75-150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, as well as muscle-strengthening activities of moderate or greater intensity at least twice weekly.

In the Reasons for Geographic and Racial Differences in Stroke (REGARDS) study, regular exercise of at least four times per week, was associated with a significant reduction in risk of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) over an approximate six-year period of follow-up.37 This finding has been replicated in studies and meta-analyses which have shown that a commitment to moderate physical activity reduces the risk of total, ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke over time.38, 39 However, it should be noted that in the REGARDS study37, the association between incident stroke and physical activity was partially attenuated after adjustment for traditional stroke risk factors (e.g. hypertension, diabetes). This observation suggests that the reduction in stroke risk results – is at least in part, from an interaction between physical activity and an attenuation of typical risk factors for stroke.

ASSOCIATION BETWEEN EXERCISE, ATRIAL FIBRILLATION AND STROKE

The presence of atrial fibrillation obviously increases the risk of stroke.1, 40 However, routine physical activity has been shown in multiple studies to reduce both the risk of incident atrial fibrillation41, as well as the amount of time spent in atrial fibrillation.42 Interestingly, there appears to be a U-shaped dose-dependent relationship between routine physical activity and incident atrial fibrillation.41 This relationship is such that moderate levels of physical activity reduce the risk of atrial fibrillation compared to sedentary individuals. However, at the extremes of exercise – such as highly trained endurance athletes, the risk of atrial fibrillation begins to increase and approximates the same risk observed among sedentary individuals.41 The mechanism for this association between extreme exercise and risk of atrial fibrillation is unclear but has been attributed to atrial remodeling, inflammation and/or atrial fibrosis.43, 44 Interestingly, it does not appear that this increase in risk of incident atrial fibrillation among endurance athletes, translates into an increase in risk of stroke. In a large analysis of Swedish cross-country skiers, the incidence of stroke among athletes with atrial fibrillation was not higher than the incidence of stroke observed among non-athletes with atrial fibrillation.45 This observation suggests that exercise has beneficial effects on other stroke risk factors, which offset increases in stroke risk that might otherwise occur as a result of atrial fibrillation.

STROKE RISK DURING EXERCISE

Despite the well-documented reductions in risk of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events associated with a lifelong commitment to physical activity, there remains a risk of stroke for any acute bout of exercise. In this regard, the Stroke Onset Study 46 reported several informative pieces of information: first, there is a greater than twofold increase in risk of ischemic stroke within one hour of completion of moderate-vigorous physical activity. However, the stroke risk during/immediately following exercise was greater among sedentary individuals (defined as individuals who exercise less than three times per week) as compared to active individuals (those who routinely exercise three or more times per week).46 Specifically, the risk of stroke was 6.8-fold higher among sedentary individuals during/immediately following exercise v. only two-fold higher for active individuals. Finally, within one hour after lifting heavy objects (defined as 50 lbs [23kg]), the risk of ischemic stroke was 2.6 times higher than exercise without heavy lifting.46 In the Australasian Cooperative Research on Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Study (ACROSS), individuals who participated in moderate-extreme exercise (defined as ≥ 5 METS) had a threefold increase in risk of subarachnoid hemorrhage within two hours of completing the exercise bout.47 This risk in hemorrhagic stroke was not attenuated by habitual exercise. These findings mirror other analyses characterizing the increased risk of myocardial infarction and/or sudden cardiac death shortly following bouts of moderate-extreme exercise.48-51 Thus, it may be that a lifelong commitment to exercise reduces the risk of ischemic stroke but not subarachnoid hemorrhage, at least in the period during and/or immediately following a bout of exercise. It is plausible that the temporal relationship between moderate-extreme exertion and SAH risk is mediated by BP since exercises that are highly static in nature lead to large and sudden increases in blood pressure. This hypothesis is supported by previous observations documenting a circadian pattern to the onset of SAH, intracerebral hemorrhage and strokes in general, with the risk being the highest in the morning – around the time of the typical diurnal surge in blood pressure and heart rate.52-54

BLOOD BIOMARKERS OF STROKE

There has been great interest in identifying biomarkers suggestive of acute stroke.55-57 Potential biomarkers have included glial structure proteins such as glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAB)58 and S100B57, matrix metalloprieinases (MMP)59, 60 and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP)61, among others. GFAB has been shown to effectively differentiate hemorrhagic and ischemic strokes.58 S100B is a sensitive marker for acute stroke but is limited by low specificity, as this biomarker is also elevated in other pathologic states such as traumatic brain injury and malignancies.62, 63 MMP-9 concentration during stroke is correlated with infarct size, as well as post-stroke complications and poor outcomes.59, 60 BNP levels are elevated in response to ischemic and cardioembolic stroke61, as well as intracerebral hemorrhage64 and subarachnoid hemorrhage.65

Several of these biomarkers may be elevated following an acute bout of exercise. GFAP has been shown to increase acutely following exercise in rat models.66 S100B is increased following running but notably, S100B is present in skeletal muscle and the increased level may be a result of skeletal muscle damage.67 An acute bout of static types of exercise leads to an increase in MMP-9, however, obesity lowers baseline MMP-9 concentrations.68 Thus, body habitus may confound MMP concentrations during/after exercise. BNP increases may occur as a result of myocardial wall stress and are particularly elevated following long-duration exercise.69 Currently, there are little data available to describe whether these increases in biomarker concentration predict stroke risk during or following activity. Further research is needed in this area, particularly since other factors such as myocardial wall stress and skeletal muscle damage, as well as body habitus – as opposed to an acute stroke, may alter biomarker concentration during/immediately following exercise.

CONCLUSION

Cerebrovascular disease is one of the most common causes of morbidity and mortality throughout the world, and in the United States in particular, given the prevalence of stroke-related risk factors. During any acute bout of exercise, there is a finite risk of stroke during and immediately following activity, and the specific hemodynamic responses – along with downstream effects on dependent organs such as the brain, may vary according to the type of exercise undertaken. Further, CBF during exercise is highly dynamic, and fluctuates in response to multiple factors, most notably, changes in PaCO2 that occur with progressive increases in workload.

Despite the acute risks, however, a lifelong commitment to exercise and/or habitual physical activity is associated with reductions in major adverse cerebrovascular and cardiovascular events, along with a host of cardiometabolic improvements.

Sources of Funding/Disclosures:

Dr. Cornwell has received funding by an NIH/NHLBI Mentored Patient-Oriented Research Career Development Award (#1K23HLI32048), as well as the NIH/NCATS (#UL1TR002535), Medtronic Inc, Bioventrix Inc, and Riva Inc. Dr. Cornwell is also a consultant for Medtronic Inc and Bioventrix Inc.

NON-STANDARD ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- BNP

brain natriuretic peptide

- BP

blood pressure

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

- ETCO2

End-tidal carbon dioxide

- GFAB

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- MAP

mean arterial pressure

- MCAV

middle cerebral arterial velocity

- METS

metabolic equivalents

- MMP

matrix metalloproteinase

- PaCO2

Partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- Qc

cardiac output

- TPR

total peripheral resistance

- VO2max

Maximal oxygen uptake

CITATIONS

- 1.Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Das SR, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Floyd J, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jimenez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Mackey RH, Matsushita K, Mozaffarian D, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, Neumar RW, Palaniappan L, Pandey DK, Thiagarajan RR, Reeves MJ, Ritchey M, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sasson C, Towfighi A, Tsao CW, Turner MB, Virani SS, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Statistics C and Stroke Statistics S. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2017 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2017;135:e146–e603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine BD, Baggish AL, Kovacs RJ, Link MS, Maron MS, Mitchell JH, American Heart Association E, Arrhythmias Committee of Council on Clinical Cardiology CoCDiYCoC, Stroke Nursing CoFG, Translational B and American College of C. Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Task Force 1: Classification of Sports: Dynamic, Static, and Impact: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Circulation. 2015;132:e262–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell JH, Haskell W, Snell P and Van Camp SP. Task Force 8: Classification of sports. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2005;45:1364–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maron BJ, Zipes DP and Kovacs RJ. Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Preamble, Principles, and General Considerations: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2015;66:2343–2349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wasfy MM, Weiner RB, Wang F, Berkstresser B, Lewis GD, DeLuca JR, Hutter AM, Picard MH and Baggish AL. Endurance Exercise-Induced Cardiac Remodeling: Not All Sports Are Created Equal. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maron BJ and Pelliccia A. The heart of trained athletes: cardiac remodeling and the risks of sports, including sudden death. Circulation. 2006;114:1633–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sarma S and Levine B. Exercise Physiology for the Clinician. Exercise and Sports Cardiology 2016;Volume 1, Edition 2:McGraw-Hill. Editor: Thompson Paul. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clifford PS, Hanel B and Secher NH. Arterial blood pressure response to rowing. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1994;26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.MacDougall JD, Tuxen D, Sale DG, Moroz JR and Sutton JR. Arterial blood pressure response to heavy resistance exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology. 1985;58:785–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu Q and Levine BD. Cardiovascular Response to Exercise in Women. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 2005;37:1433–1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McGuire DK, Levine BD, Williamson JW, Snell PG, Blomqvist G, Saltin B and Mitchell JH. A 30-Year Follow-Up of the Dallas Bed Rest and Training Study: I. Effect of Age on the Cardiovascular Response to Exercise. Circulation. 2001;104:1350–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raven PB. Neural control of the circulation: exercise. Exp Physiol. 2012;97:10–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mitchell J Wolffe memorial lecture: neural control of the circulation during exercise. . Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 1990;22:141–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mitchell JH and Victor RG. Neural control of the cardiovascular system: insights from muscle sympathetic nerve recordings in humans. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 1996;28:60–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitchell JH, Haskell WL and Raven PB. Classification of sports. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1994;24:864–866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ogoh S and Ainslie PN. Cerebral blood flow during exercise: mechanisms of regulation. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2009;107:1370–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith KJ and Ainslie PN. Regulation of cerebral blood flow and metabolism during exercise. Exp Physiol. 2017;102:1356–1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willie CK, Macleod DB, Shaw AD, Smith KJ, Tzeng YC, Eves ND, Ikeda K, Graham J, Lewis NC, Day TA and Ainslie PN. Regional brain blood flow in man during acute changes in arterial blood gases. J Physiol. 2012;590:3261–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Subudhi AW, Lorenz MC, Fulco CS and Roach RC. Cerebrovascular responses to incremental exercise during hypobaric hypoxia: effect of oxygenation on maximal performance. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2008;294:H164–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hellstrom G and Wahlgren Ng. Physical Exercise Increases Middle Cerebral Artery Blood Flow Velocity. Neurosurgery Reviews. 1993;16:151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith KJ. Fuelling cortical excitability during exercise: what's the matter with delivery? J Physiol. 2016;594:5047–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Olin JT, Dimmen AC, Subudhi AW and Roach RC. Cerebral blood flow and oxygenation at maximal exercise: the effect of clamping carbon dioxide. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2011;175:176–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Subudhi AW, Olin JT, Dimmen AC, Polaner DM, Kayser B and Roach RC. Does cerebral oxygen delivery limit incremental exercise performance? J Appl Physiol (1985). 2011;111:1727–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Edwards MR, Martin DH and Hughson R. Cerebral hemodynamics and resistance exercise. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2002;34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Edvinsson L and Krause DN. Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2002;2nd Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Symon L, Held K and Dorsch NWC. A Study of Regional Autoregulation in the Cerebra Circulation to Increased Perfusion Pressure in Normocapnia and Hypercapnia. Stroke. 1973;4:139–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pott F, Knudsen L, Nowak M, Nielsen HB, Hanel B and Secher NH. Middle Cerebral Artery Blood Velocity During Rowing. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica. 1997. 160:251–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smirl JD, Haykowsky MJ, Nelson MD, Altamirano-Diaz LA and Ainslie PN. Resting and exercise cerebral blood flow in long-term heart transplant recipients. Journal of Heart and Lung Transplantation. 2012;31:906–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosenpud JD, Morton MJ, Wilson RA, Pantely GA, Norman DJ, Cobanoglu MA and Starr A. Abnormal Exercise Hemodynamics in Cardiac Allograft Recipients 1 Year After Cardiac Transplantation. Relation to Preload Reserve. Circulation. 1989;80:525–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braith RW, Plunkett MB and Mills RM. Cardiac Output Responses During Exercise in Volume-Expanded Heart Transplant Recipients. American Journal of Cardiology. 1998;81:1152–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kokkinos P, Myers J, Faselis C, Panagiotakos DB, Doumas M, Pittaras A, Manolis A, Kokkinos JP, Karasik P, Greenberg M, Papademetriou V and Fletcher R. Exercise capacity and mortality in older men: a 20-year follow-up study. Circulation. 2010;122:790–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wickramasinghe CD, Ayers CR, Das S, de Lemos JA, Willis BL and Berry JD. Prediction of 30-year risk for cardiovascular mortality by fitness and risk factor levels: the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2014;7:597–602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jennings G, Nelson L, Nestel P, Esler M, Korner P, Burton D and Bazelmans J. The effects of changes in physical activity on major cardiovascular risk factors, hemodynamics sympathetic function and glucose utilization in man: a controlled study of four levels of activity. Circulation. 1986;73:30–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pruchnic R, Katsiaras A, He J, Kelley DE, Winters C and Goodpaster BH. Exercise training increases intramyocellular lipid and oxidative capacity in older adults. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;287:E857–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ford ES. Does Exercise Reduce Inflammatio? Physical Activity and C-Reactive PRotein Among U.S. Adults. Epidemiology. 2002;13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Committee PAGA. 2018 Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Scientific Report. . Washington, DC. 2018;U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDonnell MN, Hillier SL, Hooker SP, Le A, Judd SE and Howard VJ. Physical activity frequency and risk of incident stroke in a national US study of blacks and whites. Stroke. 2013;44:2519–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee CD, Folsom AR and Blair SN. Physical activity and stroke risk: a meta-analysis. Stroke. 2003;34:2475–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willey JZ, Moon YP, Paik MC, Boden-Albala B, Sacco RL and Elkind MSV. Physical activity and risk of ischemic stroke in the northern Manhattan Study. Neurology. 2009;73:1774–1779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolf PA, Abbott RD and Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an Independent Risk Factor for Stroke - the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:983–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jin MN, Yang PS, Song C, Yu HT, Kim TH, Uhm JS, Sung JH, Pak HN, Lee MH and Joung B. Physical Activity and Risk of Atrial Fibrillation: A Nationwide Cohort Study in General Population. Sci Rep. 2019;9:13270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Malmo V, Nes BM, Amundsen BH, Tjonna AE, Stoylen A, Rossvoll O, Wisloff U and Loennechen JP. Aerobic Interval Training Reduces the Burden of Atrial Fibrillation in the Short Term: A Randomized Trial. Circulation. 2016;133:466–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guasch E, Mont L and Sitges M. Mechanisms of atrial fibrillation in athletes: what we know and what we do not know. Neth Heart J. 2018;26:133–145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Flannery MD, Kalman JM, Sanders P and La Gerche A. State of the Art Review: Atrial Fibrillation in Athletes. Heart Lung and Circulation. 2017;26:983–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Svedberg N, Sundstrom J, James S, Hallmarker U, Hambraeus K and Andersen K. Long-Term Incidence of Atrial Fibrillation and Stroke Among Cross-Country Skiers. Circulation. 2019;140:910–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mostofsky E, Laier E, Levitan EB, Rosamond WD, Schlaug G and Mittleman MA. Physical activity and onset of acute ischemic stroke: the stroke onset study. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173:330–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anderson C, Ni Mhurchu C, Scott D, Bennett D, Jamrozik K, Hankey G and Australasian Cooperative Research on Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Study G. Triggers of subarachnoid hemorrhage: role of physical exertion, smoking, and alcohol in the Australasian Cooperative Research on Subarachnoid Hemorrhage Study (ACROSS). Stroke. 2003;34:1771–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Tofler GH, Sherwood JB, Goldberg RJ and Muller JE. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329:1677–1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Willich SN, Lewis M, Lowel H, Arntz H-R, Schubert F and R. S. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine. 1993;329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muller JE, Mittleman MA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB and Tofler GH. Triggering myocardial infarction by sexual activity. Low absolutely risk and prevention by regular physical exertion. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1996;275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Albert CM, Mittleman MA, Chae CU, Lee I-M, Hennekens CH and Manson JE. Triggering of sudden death from cardiac causes by vigorous exertion. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feigin VL, Anderson CS, Anderson NE, Broad JB, PLedger MJ and R. B. Is There a Temporal Pattern in the Occurrence of Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in the Southern Hemisphere? Stroke. 2001;32:613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Passero S, Ciacci G and Reale F. Potential triggering factors of intracerebral hemorrhage. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2001;12:220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stergiou GS, Vemmos KN, Pliarchopoulou KM, Synetos AG, Roussias LG and Mountokalakis TD. Parallel morning and evening surge in stroke onset, blood pressure, and physical activity. Stroke. 2002;33:1480–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jickling GC and Sharp FR. Blood biomarkers of ischemic stroke. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:349–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kim SJ, Moon GJ and Bang OY. Biomarkers for stroke. J Stroke. 2013;15:27–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dagonnier M, Donnan GA, Davis SM, Dewey HM and Howells DW. Acute Stroke Biomarkers: Are We There Yet? Frontiers in Neurology. 2021;12:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dvorak F, Haberer I, Sitzer M and FOerch C. Characterisation of the diagnostic window of serum glial fibrillary acidic protein for the differentiation of intracerebral hemorrhage and ischaemic stroke. Cerebrovascular Diseases. 2009;27:37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Montaner J, ALvarez-Sabin J, Molina CA, Angles A, Abilleira S, Arenillas J and Monasterio J. Matrix Metallopriteinase Expression Is Related to Hemorrhagic Transformation After Cardioembolic Stroke. Stroke. 2001;32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rosell A, Alvarez-Sabin J, Arenillas JF, Rovira A, Delgado P, Fernandez-Cadenas I, Penalba A, Molina CA and Montaner J. A matrix metalloproteinase protein array reveals a strong relation between MMP-9 and MMP-13 with diffusion-weighted image lesion increase in human stroke. Stroke. 2005;36:1415–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Montaner J, Perea-Gainza M, Delgado P, Ribo M, Chacon P, Rosell A, Quintana M, Palacios ME, Molina CA and Alvarez-Sabin J. Etiologic diagnosis of ischemic stroke subtypes with plasma biomarkers. Stroke. 2008;39:2280–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ishiguro Y, Kato K, Ito T and Nagaya M. Determination of three enolase isozymes and S-100 protein in various tumors in children. Cancer Research. 1983;42:6080–6084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Raabe A, Grolms C, Keller M, Dohner J, SOrge O and Seifert V. Correlation of computed tomography findings and serum brain damage markers following severe head injury. Acta Neurochirurgica. 1998;140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shibazaki K, Kimura K, Sakai K, Aoki J and Sakamoto Y. Plasma brain natriuretic peptide is elevated in the acute phase of intracerebral hemorrhage. Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 2014;21:221–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sviri GE, FEinsod M and Soustiel JF. Brain Natriuretic Peptide and Cerebral Vasospasm in Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. 31. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Saur L, Baptista PP, de Senna PN, Paim MF, do Nascimento P, Ilha J, Bagatini PB, Achaval M and Xavier LL. Physical exercise increases GFAP expression and induces morphological changes in hippocampal astrocytes. Brain Struct Funct. 2014;219:293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stocchero CMA, Oses JP, Cunha GS, Martins JB, Brum LM, Zimmer ER, Souza DO, Portela LV and Reischak-Oliveira A. Serum S100B level increases after running but not cycling exercise. Applied Physiology, Nutrition and Metabolism. 2014;39:340–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jaoude J and Koh Y. Matrix metalloproteinases in exercise and obesity. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2016;12:287–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hamasaki H. The Effects of Exercise on Natriuretic Peptides in Individuals without Heart Failure. Sports (Basel). 2016;4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]