Abstract

3-Caffeoyl-4-dicaffeoylquinic acid (CDCQ) is a natural chlorogenic acid isolated from Salicornia herbacea that protects against oxidative stress, inflammation, and cancer. Nitric oxide (NO) plays a physiologically beneficial role in the cardiovascular system, including vasodilation, protection of endothelial cell function, and anti-inflammation. However, the effect of CDCQ on NO production and eNOS phosphorylation in endothelial cells is unclear. We investigated the effect of CDCQ on eNOS phosphorylation and NO production in human endothelial cells, and the underlying signaling pathway. CDCQ significantly increased NO production and the phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177. Additionally, CDCQ induced phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK. Interestingly, CDCQ increased the intracellular Ca2+ level, and L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC) blockade significantly attenuated CDCQ-induced eNOS activity and NO production by inhibiting PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK phosphorylation. These results suggest that CDCQ increased eNOS phosphorylation and NO production by Ca2+-dependent phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK. Our findings provide evidence that CDCQ plays a pivotal role in the activity of eNOS and NO production, which is involved in the protection of endothelial dysfunction.

Keywords: 3-Caffeoyl-4-dicaffeoylquinic acid, eNOS, Nitric oxide, Ca2+, L-type Ca2+ channel

Introduction

Endothelial cells regulate hemostasis and blood flow, platelet aggregation, and vascular tone, and are important for maintaining vascular health [1]. Nitric oxide (NO) protects the cardiovascular system by regulating endothelial function and vascular tone. NO is produced by endothelial NO synthase (eNOS) in vascular endothelial cells from L-arginine and regulates blood vessel tension by increasing smooth muscle cell relaxation [2]. Additionally, NO exerts a protective effect on vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis by inhibiting endothelial dysfunction, endothelial leukocyte adhesion and migration, platelet aggregation, and thrombosis [3].

Phosphorylation of eNOS at serine (Ser) 1177 is important for its activation and function, which is related to NO production [4, 5]. An increase in the intracellular Ca2+ level in the endothelium promotes NO production by activating calmodulin (CaM) and CaM-dependent kinase II (CaMKII), which increases eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 [6, 7]. In addition, CaM-dependent protein kinase kinase β (CaMKKβ) and AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), which is associated with the intracellular Ca2+ level, prevents endothelial dysfunction by increasing eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 [8, 9]. Activation of 3′,5′-cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP)-dependent protein kinase (PKA) exerts a vasorelaxant effect by increasing NO release via enhanced eNOS activity in endothelial cells [10]. The Ca2+ signaling pathway is associated with soluble adenylyl cyclase (sAC), which phosphorylates PKA [11]. The L-type Ca2+ channel (LTCC), which is commonly expressed in the cardiovascular system, is a major source of intracellular calcium influx [12]. The pharmacological and molecular biological aspects of the role of LTCC in endothelial cells have been investigated [13, 14].

Herbs extracted from plants have been used to treat and prevent disease, but the physiological mechanisms are unclear. Salicornia herbacea (S. herbacea), a halophyte that grows wild in salt marshes and muddy coasts, has been used as a seasonal food and as a folk remedy for preventing obesity, diabetes, and cancer in coastal areas of Korea [15–18]. In our previous study reported that 3-Caffeoyl-4-dicaffeoylquinic acid (CDCQ), a natural chlorogenic acid derivative extracted from S. herbacea, has anti-oxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-diabetes, and anti-cancer effects [19–22]. Recent study reported that chlorogenic acid exerts a protective effect on endothelial dysfunction and hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats [23]. In addition, 5-caffeoylquinic acid, structurally similar to CDCQ, attenuates TNF-α-induced oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction [24]. Despite various pharmacological effect of CDCQ and the cardiovascular protective effect of chlorogenic acid, the effect of CDCQ on eNOS phosphorylation and NO production in endothelial cells, and the molecular mechanism, is unclear. Thus, we investigated the effects of CDCQ on eNOS activation and NO production. Here we report the molecular mechanism underlying the effect of CDCQ on NO production and eNOS activity in EA.hy926 human endothelial cells. CDCQ increased NO production and the phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177. Furthermore, PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK are involved in eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 in response to CDCQ. In addition, CDCQ increased the intracellular Ca2+ level, and LTCC blockade attenuated CDCQ-induced eNOS activity and NO production by inhibiting PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK phosphorylation. To our knowledge, this is the first report of Ca2+-dependent eNOS activation by CDCQ.

Materials and methods

Materials

CDCQ was isolated from S. herbacea as described previously [16]. The purity of CDCQ was more than 92% by HPLC analysis. 4,5-diaminofluorescein diacetate (DAF-2 DA) and fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester (Fluo-4-AM) were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA, USA). l-NAME, compound C, and N-[6-aminohexyl]-5-chloro-1-naphthalenesulfonamide hydrochloride (W7) were purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA). Nifedipine, STO-609, H-89 and KN-62 were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against p-eNOS (Ser1177), p-AMPK (Thr172), p-CaMKII (Thr286), p-CaMKKβ (Ser511), and p-PKA (Thr198) as well as horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antimouse and anti-rabbit IgG antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, USA). Anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All other chemicals were of the highest grade commercially available.

Cell culture and treatment

Human endothelial EA.hy926 cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Bethesda, MD, USA). The cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin and streptomycin (Welgene, Gyeonwgsan, Korea). The cells were incubated in DMEM containing 10% FBS at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator. CDCQ was prepared by dissolving CDCQ in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) and adding to the medium; the final concentration of DMSO did not exceed 0.1%.

MTT and LDH assay

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) reduction and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assays were used to investigate the toxicity of CDCQ to endothelial cells. MTT was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), and LDH release kit from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Endothelial cells were seeded in 48-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) and incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. Cells were treated with 1–20 μM CDCQ and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h. The absorbance at 550 nm (MTT) and 490 nm (LDH) was determined using a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT, USA). Calculations of cell viability (%) and cytotoxicity (%) were based on the absorbance of treated cells relative to that of cells exposed to DMSO alone.

Western blot analysis

Endothelial cells were lysed in CETi lysis buffer (TransLab, Daejeon, Korea) on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min. Supernatants were collected, and protein concentrations were determined at 595 nm using a Protein Assay Kit (Pro-Measure, Intron Biotechnology). Equal amounts of total cellular proteins were boiled for 5 min and electrophoresed in 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gels. Next, the proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were incubated with primary antibodies, followed by a secondary anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibody. Band intensities were measured using an enhanced the Hisol ECL Plus Detection Kit (BioFact, Daejeon, Korea).

Measurement of NO production

NO was measured using the NO-specific fluorescent dye DAF-2DA [13]. The absorbance at 495/515 nm of culture medium was measured using a BioTek Synergy HT microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski). The cells were fixed in 5% paraformaldehyde for 5 min at 4 °C and visualized using an EVOS fluorescence microscope (Life Technologies).

Ca2+ measurement

Intracellular calcium levels were evaluated using Fluo-4AM as per the manufacturer’s instructions [13]. Fluo-4AM was excited at a wavelength of 488 nm and emission was monitored at 512 nm. Fluorescence images of selected cells were captured using an EVOS fluorescence microscope (Life Technologies).

Statistical analysis

The data are means ± standard deviation (SD) of at least three independent experiments. One-way analysis of variance was used to identify significant differences between groups. The Newman–Keuls test was used to compare multiple groups. P-values < 0.01 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Effect of CDCQ on viability of endothelial cells

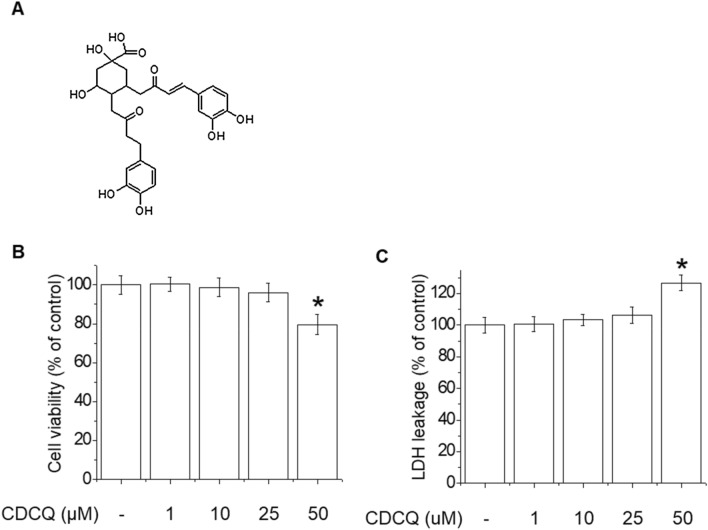

The chemical structure of CDCQ is shown in Fig. 1a. To investigate the effect of CDCQ on cytotoxicity, MTT and LDH assays were performed. CDCQ at 50 μM decreased endothelial cell viability and increased cytotoxicity (Fig. 1b, c). Therefore, in subsequent experiments we evaluated effects on eNOS phosphorylation and NO production using 5–20 μM CDCQ.

Fig. 1.

Chemical structure of CDCQ and effect on cell viability of endothelial cells. a Chemical structure of CDCQ. b Cell viability by MTT assay. c Cytotoxicity by LDH assay. *Significantly different from the control at p < 0.01

Effect of CDCQ on eNOS phosphorylation and NO production

NO production by eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 play a protective physiological role in the vasculature [2, 5]. In endothelial cells, we evaluated the effect of CDCQ on NO production and the phosphorylation of eNOS. As shown in Fig. 2a, CDCQ concentration-dependently increased NO production, and pretreatment with l-NAME (a NOS inhibitor) attenuated the NO production increased by CDCQ. In addition, treatment with 20 μM CDCQ for 30–120 min significantly induced phosphorylation of eNOS. Treatment with 5–20 μM CDCQ for 1 h induced concentration-dependent phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 (Fig. 2b, c).

Fig. 2.

Effect of CDCQ on eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 and NO production. a Cells were treated with 5–20 µM CDCQ for 90 min or pretreated with 100 µM l -NAME for 1 h and then 20 µM CDCQ for 90 min. NO was assayed using DAF-2 DA. Cells were treated with 20 µM CDCQ for 10–120 min (b) or 5–20 µM CDCQ for 60 min (c) and assessed by Western blotting. *Significantly different from the control at p < 0.01. #Significantly different from CDCQ-treated cells at p < 0.01

PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ and AMPK are required for phosphorylation of eNOS by CDCQ

Phosphorylation of eNOS at Ser1177 is related to various kinase activity, including CaMKII, CaMKKβ, AMPK, Akt and PKA [25]. We next investigated the upstream signaling pathways involved in CDCQ-mediated eNOS phosphorylation. CDCQ increased the phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK in a time- and concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 3a, b). Furthermore, pretreatment with H89 (a PKA inhibitor), KN62 (a CaMKII, inhibitor), compound C (CC, an AMPK inhibitor), and STO-609 (STO, a CaMKKβ inhibitor) attenuated CDCQ-induced eNOS phosphorylation in endothelial cells (Fig. 3c, d). These results suggest that the phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK are essential upstream kinases of eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 by CDCQ.

Fig. 3.

Effect of CDCQ on phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK. Cells were treated with 20 µM CDCQ for 5–60 min (a) or 5–20 µM CDCQ for 15 min (b) and assessed by Western blotting. c Cells were pretreated with 10 µM H89 (PKA inhibitor) and 10 µM KN62 (CaMKII inhibitor) for 1 h and 20 µM CDCQ for 60 min. d Cells were pretreated with 10 µM Compound C (CC, an AMPK inhibitor) and 10 µM STO-609 (STO, a CaMKKβ inhibitor) for 1 h and 20 µM CDCQ for 60 min. Western blotting was performed to assess phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKKβ, CaMKII, AMPK, and eNOS. *Significantly different from the control at p < 0.01. #Significantly different from CDCQ-treated cells at p < 0.01

Effect of CDCQ on the intracellular Ca2+ level in endothelial cells

Increased intracellular Ca2+ induces eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 through CaM activation, leading to NO generation [7]. We assessed the effects of CDCQ on the intracellular Ca2+ level, using Fluo-4-AM, a marker of intracellular Ca2+. As shown in Fig. 4a, CDCQ concentration-dependently increased the intracellular Ca2+ level in endothelial cells. Interestingly, pretreatment with EDTA (an extracellular calcium chelator), but not 2-APB (an IP3 receptor inhibitor) and tetracaine (Tetra, a RyR inhibitor), markedly attenuated CDCQ-induced eNOS phosphorylation in endothelial cells (Fig. 4b). These results suggest that extracellular calcium influx is closely related to the effect of CDCQ on eNOS phosphorylation.

Fig. 4.

An increased intracellular Ca2+ level is required for CDCQ-induced eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177. a Intracellular Ca2+ level was assayed using the fluorescent calcium indicator, Fluo-4-AM. Fluo-4-AM-treated cells were stimulated with 5–20 µM CDCQ for 5 min. b Cells were pretreated with 50 μM 2-ABP (IP3 receptor inhibitor), 50 μM tetracaine (Tetra, RyR inhibitor), or 0.5 mM EDTA for 30 min, and subsequently with 20 µM CDCQ for 60 min before being assessed by Western blotting. *Significantly different from the control at p < 0.01. #Significantly different from CDCQ-treated cells at p < 0.01

LTCC blockade suppressed the CDCQ-mediated increase in intracellular Ca2+ level and eNOS phosphorylation via the PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK pathways

The LTCC is the primary source of Ca2+ influx, which increases intracellular Ca2+ level and initiates the subsequent activation of RyR in the SR membrane [26]. To determine whether LTCC is involved in intracellular Ca2+ influx and eNOS phosphorylation by CDCQ, we treated cells with nifedipine (a LTCC blocker). As shown in Fig. 5a, pretreatment with nifiedifine inhibited the CDCQ-mediated increase in intracellular Ca2+ level. In addition, pretreatment with nifiedifine, BAPTA-AM (an intracellular calcium chelator), and W7 (a CaM inhibitor) reduced CDCQ-induced phosphorylation of eNOS as well as PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK (Fig. 5b, c). Furthermore, inhibition of LTCC, PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK significantly suppressed the CDCQ-mediated increased NO production in endothelial cells (Fig. 5d). These results implicate LTCC in CDCQ-mediated Ca2+-dependent eNOS phosphorylation and NO production.

Fig. 5.

LTCC is involved in CDCQ-induced eNOS activity and NO production via phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKKβ, CaMKII, and AMPK. a The effect of CDCQ on intracellular Ca2+ influx in endothelial cells is mediated by LTCC. Cells were pretreated with 50 μM nifedipine (NIF) and Fluo-4-AM was applied. Next, the cells were stimulated with 20 µM CDCQ for 5 min. b Effects of LTCC and calmodulin inhibition on eNOS phosphorylation by CDCQ. Cells were pretreated with 10 μM NIF, 10 μM BAPTA-AM (BAPTA), or 10 μM W7 for 30 min, and then with 20 μM CDCQ for 1 h. c Cells were pretreated with 50 μM NIF, 10 μM BAPTA, and 10 μM W7 for 30 min, and then with 20 μM CDCQ for 15 min. Western blotting was performed to assess phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKKβ, CaMKII, AMPK, and eNOS. d Cells were pretreated with 50 μM NIF, 10 μM H89, 10 μM CC, or 10 μM KN62 for 30 min prior to incubation with DAF-2DA for 30 min and treatment with 20 μM CDCQ for 90 min. NO production was assayed using the NO-specific fluorescent dye DAF-2 DA. *Significantly different from the control at p < 0.01. #Significantly different from CDCQ-treated cells at p < 0.01

Discussion

In the vascular endothelium, NO regulates the tone of blood vessels, endothelial cell function, and inhibits the immune cell adhesion [27, 28]. Chlorogenic acid, a polyphenol with important pharmacological activities extracted from plants such as coffee beans, protects against diseases such as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and atherosclerosis [29]. We isolated CDCQ, a novel chlorogenic acid derivative, from S. herbacea and demonstrated its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and anticancer effects [19, 20]. However, the effect of CDCQ on NO production and eNOS phosphorylation in endothelial cells was unclear. In this study, we investigated the influence and mechanism of CDCQ on NO production and eNOS activity in human endothelial cells. CDCQ induced eNOS phosphorylation by activating the intracellular Ca2+-dependent PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK signaling pathways in a manner involving LTCC.

The binding site of CaM is between the N-terminal oxygenase domain and the C-terminal reductase domain in the eNOS protein structure [30]. In addition, Ca2+/CaM-dependent kinases such as CaMKII and CaMKKβ protect endothelial dysfunction by enhancing NO production by promoting eNOS activity [31, 32]. Our results showed that CDCQ induced eNOS phosphorylation and NO production in endothelial cells. CDCQ also increased the phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK. Interestingly, inhibition of CaMKII and CaMKKβ suppressed CDCQ-induced eNOS phosphorylation and NO production. CaMKKβ triggers eNOS phosphorylation by inducing AMPK activation, which prevents endothelial cell dysfunction by increasing NO synthesis in endothelial cells [32, 33]. In this study, AMPK and PKA inhibition markedly attenuated CDCQ-induced eNOS phosphorylation and NO production in endothelial cells. Walther et al. reported that PKA induced eNOS phosphorylation, enhancing NO synthesis and activating cGMP signaling [34]. These data suggest that CDCQ induced eNOS phosphorylation and NO production by the phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK in endothelial cells.

LTCC is present in the membrane of endothelial cells and mediates signaling by increasing intracellular Ca2+ influx [24, 35]. In this study, LTCC blockade attenuated CDCQ-induced eNOS phosphorylation and intracellular Ca2+ influx. In addition, pretreatment with nifiedifine, BAPTA-AM, and W7 suppressed the CDCQ-mediated increase in the phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK. Similarly, BA, a physiological activator, increased the intracellular Ca2+ level and activated CaM, promoting eNOS activity and NO production via phosphorylation of CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK [13]. CaM activation by Ca2+ stimulates sAC to increase the cAMP level in mammalian cells. Parker et al. reported that Ca2+ influx activates sAC, which triggers vasodilation by increasing cAMP and PKA activity in vascular smooth muscle cells [36]. In this study, CDCQ increased eNOS activity via PKA phosphorylation, and inhibition of LTCC and CaM attenuated CDCQ-induced PKA phosphorylation and eNOS activity. Therefore, CDCQ stimulates Ca2+/CaM as an upstream regulator of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK phosphorylation in endothelial cells.

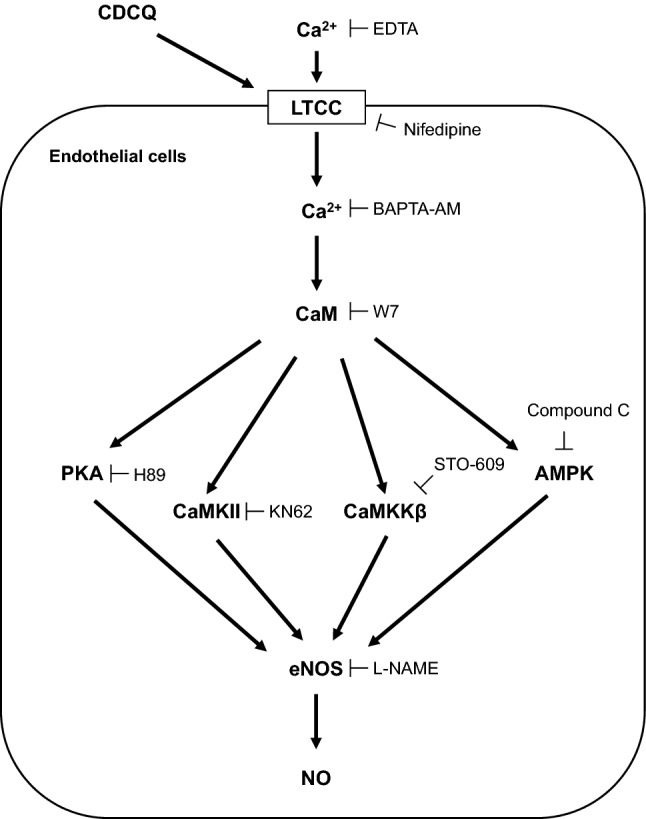

In conclusion, CDCQ stimulates LTCC to promote Ca2+ influx into endothelial cells. The resulting increased intracellular Ca2+ level induces phosphorylation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK via the CaM signaling pathway. Finally, activation of PKA, CaMKII, CaMKKβ, and AMPK by CDCQ induced NO production and eNOS phosphorylation at Ser1177 (Fig. 6). Therefore, CDCQ exerts a protective effect on endothelial cell function.

Fig. 6.

Summarized molecular mechanism of CDCQ on eNOS activation and NO production in endothelial cells. CDCQ increases intracellular Ca2+ level through the LTCC and then induces phosphorylation of CaMKII, CaMKKβ, AMPK, and PKA, thus leading to increase eNOS activation and NO production in endothelial cells

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by research fund of Chungnam National University.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: GHL and HGJ; Formal analysis and investigation: GHL, SYL, CZ, HTP, CYK, MYK, EHH, YPH, and HGJ; Writing—original draft preparation: GHL; Writing—review and editing: GHL and HGJ; Funding acquisition: HGJ; Supervision: HGJ; All authors read and approved the fnal manuscript.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Heo KS, Berk BC, Abe J. Disturbed flow-induced endothelial proatherogenic signaling via regulating post-translational modifications and epigenetic events. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2016;25:435–450. doi: 10.1089/ars.2015.6556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li H, Forstermann U. Nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of vascular disease. J Pathol. 2000;190:244–254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200002)190:3&lt;244::AID-PATH575&gt;3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forstermann U, Sessa WC (2012) Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur Heart J 33:829–837, 837a–837d. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Fulton D, Gratton JP, McCabe TJ, Fontana J, Fujio Y, Walsh K, Franke TF, Papapetropoulos A, Sessa WC. Regulation of endothelium-derived nitric oxide production by the protein kinase Akt. Nature. 1999;399:597–601. doi: 10.1038/21218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher AM. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature. 1999;399:601–605. doi: 10.1038/21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Busse R, Mulsch A. Calcium-dependent nitric oxide synthesis in endothelial cytosol is mediated by calmodulin. FEBS Lett. 1990;265:133–136. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80902-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider JC, El Kebir D, Chereau C, Lanone S, Huang XL, De Buys Roessingh AS, Mercier JC, Dall'Ava-Santucci J, Dinh-Xuan AT. Involvement of Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in endothelial NO production and endothelium-dependent relaxation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H2311–2319. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00932.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee GH, Kim CY, Zheng C, Jin SW, Kim JY, Lee SY, Kim MY, Han EH, Hwang YP, Jeong HG. Rutaecarpine increases nitric oxide synthesis via eNOS phosphorylation by TRPV1-dependent CaMKII and CaMKKbeta/AMPK signaling pathway in human endothelial cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9407. doi: 10.3390/ijms22179407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin SW, Pham HT, Choi JH, Lee GH, Han EH, Cho YH, Chung YC, Kim YH, Jeong HG. Impressic acid, a lupane-type triterpenoid from Acanthopanax koreanum, attenuates TNF-alpha-induced endothelial dysfunction via activation of eNOS/NO pathway. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20:5772. doi: 10.3390/ijms20225772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia-Morales V, Cuinas A, Elies J, Campos-Toimil M. PKA and Epac activation mediates cAMP-induced vasorelaxation by increasing endothelial NO production. Vascul Pharmacol. 2014;60:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Litvin TN, Kamenetsky M, Zarifyan A, Buck J, Levin LR. Kinetic properties of “soluble” adenylyl cyclase. Synergism between calcium and bicarbonate. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15922–15926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212475200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catterall WA. Voltage-gated calcium channels. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2011;3:a003947. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a003947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin SW, Choi CY, Hwang YP, Kim HG, Kim SJ, Chung YC, Lee KJ, Jeong TC, Jeong HG. Betulinic acid increases eNOS phosphorylation and NO synthesis via the calcium-signaling pathway. J Agric Food Chem. 2016;64:785–791. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b05416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mergler S, Pleyer U, Reinach P, Bednarz J, Dannowski H, Engelmann K, Hartmann C, Yousif T. EGF suppresses hydrogen peroxide induced Ca2+ influx by inhibiting L-type channel activity in cultured human corneal endothelial cells. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:285–293. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chinnusamy V, Zhu J, Zhu JK. Salt stress signaling and mechanisms of plant salt tolerance. Genet Eng (N Y) 2006;27:141–177. doi: 10.1007/0-387-25856-6_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung YC, Chun HK, Yang JY, Kim JY, Han EH, Kho YH, Jeong HG. Tungtungmadic acid, a novel antioxidant, from Salicornia herbacea. Arch Pharm Res. 2005;28:1122–1126. doi: 10.1007/BF02972972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Im SA, Kim K, Lee CK. Immunomodulatory activity of polysaccharides isolated from Salicornia herbacea. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryu DS, Kim SH, Lee DS. Anti-proliferative effect of polysaccharides from Salicornia herbacea on induction of G2/M arrest and apoptosis in human colon cancer cells. J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;19:1482–1489. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0902.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hwang YP, Yun HJ, Chun HK, Chung YC, Kim HK, Jeong MH, Yoon TR, Jeong HG. Protective mechanisms of 3-caffeoyl, 4-dihydrocaffeoyl quinic acid from Salicornia herbacea against tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced oxidative damage. Chem Biol Interact. 2009;181:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han EH, Kim JY, Kim HG, Chun HK, Chung YC, Jeong HG. Inhibitory effect of 3-caffeoyl-4-dicaffeoylquinic acid from Salicornia herbacea against phorbol ester-induced cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages. Chem Biol Interact. 2010;183:397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hwang YP, Kim HK, Choi JH, Do MT, Tran TP, Chun HK, Chung YC, Jeong TC, Jeong HG. 3-Caffeoyl, 4-dihydrocaffeoylquinic acid from Salicornia herbacea attenuates high glucose-induced hepatic lipogenesis in human HepG2 cells through activation of the liver kinase B1 and silent information regulator T1/AMPK-dependent pathway. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;57:471–482. doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201200529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hwang YP, Yun HJ, Choi JH, Chun HK, Chung YC, Kim SK, Kim BH, Kwon KI, Jeong TC, Lee KY, Jeong HG. 3-Caffeoyl, 4-dihydrocaffeoylquinic acid from Salicornia herbacea inhibits tumor cell invasion by regulating protein kinase C-delta-dependent matrix metalloproteinase-9 expression. Toxicol Lett. 2010;198:200–209. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2010.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S, Sarria B, Mateos R, Goya L, Bravo-Clemente L. TNF-alpha-induced oxidative stress and endothelial dysfunction in EA.hy926 cells is prevented by mate and green coffee extracts, 5-caffeoylquinic acid and its microbial metabolite, dihydrocaffeic acid. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2019;70:267–284. doi: 10.1080/09637486.2018.1505834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suzuki A, Yamamoto N, Jokura H, Yamamoto M, Fujii A, Tokimitsu I, Saito I. Chlorogenic acid attenuates hypertension and improves endothelial function in spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1065–1073. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226196.67052.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pham TH, Jin SW, Lee GH, Park JS, Kim JY, Thai TN, Han EH, Jeong HG. Sesamin induces endothelial nitric oxide synthase activation via transient receptor potential vanilloid type 1. J Agric Food Chem. 2020;68:3474–3484. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b07909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bito V, Heinzel FR, Biesmans L, Antoons G, Sipido KR. Crosstalk between L-type Ca2+ channels and the sarcoplasmic reticulum: alterations during cardiac remodelling. Cardiovasc Res. 2008;77:315–324. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvm063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeiher AM, Drexler H, Wollschlager H, Just H. Endothelial dysfunction of the coronary microvasculature is associated with coronary blood flow regulation in patients with early atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1991;84:1984–1992. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.84.5.1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Scioli MG, Storti G, D’Amico F, Rodriguez Guzman R, Centofanti F, Doldo E, Cespedes Miranda EM, Orlandi A. Oxidative stress and new pathogenetic mechanisms in endothelial dysfunction: potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1995. doi: 10.3390/jcm9061995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amato A, Caldara GF, Nuzzo D, Baldassano S, Picone P, Rizzo M, Mule F, Di Carlo M. NAFLD and atherosclerosis are prevented by a natural dietary supplement containing curcumin, silymarin, guggul, chlorogenic acid and inulin in mice fed a high-fat diet. Nutrients. 2017;9:492. doi: 10.3390/nu9050492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wu KK. Regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase activity and gene expression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;962:122–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koo BH, Hwang HM, Yi BG, Lim HK, Jeon BH, Hoe KL, Kwon YG, Won MH, Kim YM, Berkowitz DE, Ryoo S. Arginase II contributes to the Ca(2+)/CaMKII/eNOS axis by regulating Ca(2+) concentration between the cytosol and mitochondria in a p32-dependent manner. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e009579. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.009579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoshitomi H, Zhou J, Nishigaki T, Li W, Liu T, Wu L, Gao M. Morinda citrifolia (Noni) fruit juice promotes vascular endothelium function in hypertension via glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor-CaMKKbeta-AMPK-eNOS pathway. Phytother Res. 2020;34:2341–2350. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ying L, Li N, He Z, Zeng X, Nan Y, Chen J, Miao P, Ying Y, Lin W, Zhao X, Lu L, Chen M, Cen W, Guo T, Li X, Huang Z, Wang Y. Fibroblast growth factor 21 Ameliorates diabetes-induced endothelial dysfunction in mouse aorta via activation of the CaMKK2/AMPKalpha signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:665. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-1893-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walther S, Pluteanu F, Renz S, Nikonova Y, Maxwell JT, Yang LZ, Schmidt K, Edwards JN, Wakula P, Groschner K, Maier LS, Spiess J, Blatter LA, Pieske B, Kockskamper J. Urocortin 2 stimulates nitric oxide production in ventricular myocytes via Akt- and PKA-mediated phosphorylation of eNOS at serine 1177. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2014;307:H689–700. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00694.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nilius B, Droogmans G. Ion channels and their functional role in vascular endothelium. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:1415–1459. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.4.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker T, Wang KW, Manning D, Dart C. Soluble adenylyl cyclase links Ca(2+) entry to Ca(2+)/cAMP-response element binding protein (CREB) activation in vascular smooth muscle. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7317. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43821-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]