Abstract

Introduction

During the COVID-19 pandemic various degrees of lockdown were applied by countries around the world. It is considered that such measures have an adverse effect on mental health but the relationship of measure intensity with the mental health effect has not been thoroughly studied. Here we report data from the larger COMET-G study pertaining to this question.

Material and Methods

During the COVID-19 pandemic, data were gathered with an online questionnaire from 55,589 participants from 40 countries (64.85% females aged 35.80 ± 13.61; 34.05% males aged 34.90±13.29 and 1.10% other aged 31.64±13.15). Anxiety was measured with the STAI, depression with the CES-D and suicidality with the RASS. Distress and probable depression were identified with the use of a previously developed cut-off and algorithm respectively.

Statistical Analysis

It included the calculation of Relative Risk (RR), Factorial ANOVA and Multiple backwards stepwise linear regression analysis

Results

Approximately two-thirds were currently living under significant restrictions due to lockdown. For both males and females the risk to develop clinical depression correlated significantly with each and every level of increasing lockdown degree (RR 1.72 and 1.90 respectively). The combined lockdown and psychiatric history increased RR to 6.88 The overall relationship of lockdown with severity of depression, though significant was small.

Conclusions

The current study is the first which reports an almost linear relationship between lockdown degree and effect in mental health. Our findings, support previous suggestions concerning the need for a proactive targeted intervention to protect mental health more specifically in vulnerable groups

Keywords: COVID-19; Depression; Suicidality; Mental health, lockdown, anxiety, mental health history

1. Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic started spreading as an epidemic of an infectious agent, governments around the world were soon obliged to adopt strict measures of social distancing and isolation in order to contain the pandemic. The strictest of these measures was the lockdown which took a variety of forms and was applied with different intensity on different countries and different groups of the population. It was soon evident that although it was probably the most efficacious of all measures in the controlling of the pandemic (Fountoulakis et al., 2022a, 2020), it might had an adverse effect on population mental health at a large scale. This effect should be considered in combination with the overwhelming burst of information of questionable reliability and validity (‘infodemic’) (Asmundson and Taylor, 2021) and the abuse of the term ‘trauma’ and ‘PTSD’. In general, during the pandemic but particularly because of the repeated lockdowns, mental health has gained a central position as an area which is expected to be affected by the pandemic because of its threatening nature as well as because of the profound impact on everyday life of people. Especially concerning the later, it has been suggested that lockdowns triggered feelings of loneliness, irritableness, restlessness, and nervousness in the general population (Saladino et al., 2020),

There are many reports in the literature suggesting that the COVID‐19 outbreak triggered feelings of fear, worry, and stress, as responses to an extreme threat for the community and the individual with the general picture suggesting that more than 40% of the general population might experience high levels of anxiety or distress (Fountoulakis et al., 2021a, 2022b, 2021b; Fullana et al., 2020; Fullana and Littarelli, 2021; Gonda and Tarazi, 2021; Kaparounaki et al., 2020; Kopishinskaia et al., 2021; Kulig et al., 2020; Patsali et al., 2020; Ren et al., 2020; Salari et al., 2020; Smirnova et al., 2021; Vinkers et al., 2020; Vrublevska et al., 2021a), especially during lockdowns (Czeisler et al., 2021; Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Mary-Krause et al., 2021; Pieh et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2021), and including health care professionals (Karlafti et al., 2022). The issue of increased suicidality as a consequence of extreme stress and depression has been raised again (Courtet and Olie, 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; Efstathiou et al., 2021; Pompili, 2021). In addition, changes to social behavior, as well as working conditions, daily habits and routine have imposed secondary stress. Especially the expectation of an upcoming economic crisis and possible unemployment were stressful factors. The vast majority of studies reported a ‘tsunami’-scale impact on mental health. It is highly possible that this reporting could be an exaggeration (Shevlin et al., 2021). Higher levels of anxiety, stress and depressive feelings have been reported, but it seems that this depends on the temporal situation and the specific events; response is by no means homogenous (Fancourt et al., 2021; Mortier et al., 2021; Racine et al., 2021; Shevlin et al., 2021; Taquet et al., 2021; Wong et al., 2020). It is important to note that negative reports do exist, and they come from the study of carefully selected representative samples (van der Velden et al., 2020). Another important observation is that the population as a whole seemed to adjust rather well to the new situation and successfully cope with challenges at least in the middle term (Fancourt et al., 2021). Conspiracy theories and maladaptive behaviors were also prevalent, compromising the public defense against the outbreak.

Currently there is a great number of empirical data papers on the possible effect of lockdown on mental health, but no reliable assessments of clinical cases of depression exist. Reports suggest that up to half of the population might experience significant elevations in anxiety and depressive feelings (Al-Ajlouni et al., 2020; Antiporta et al., 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; De Pietri and Chiorri, 2021; Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Jacques-Avino et al., 2020; Kakaje et al., 2021; Khubchandani et al., 2021; Killgore et al., 2021; Kopilas et al., 2021; Mary-Krause et al., 2021; Msherghi et al., 2021; Pandey et al., 2020; Pieh et al., 2020; Ramiz et al., 2021; Simon et al., 2021; Smirnova et al., 2021; Surina et al., 2021; Vrublevska et al., 2021b) with the symptomatology being mixed and complex (Ben-Ezra et al., 2021; Di Blasi et al., 2021; Mary-Krause et al., 2021) and many individuals experiencing a severe form of psychopathology (Al-Ajlouni et al., 2020; Pieh et al., 2020) and high levels of suicidal ideation (Bell et al., 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; Efstathiou et al., 2021; Every-Palmer et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2021). Females seems to be at a higher risk (Andersen et al., 2021a; Cruyt et al., 2021; De Pietri and Chiorri, 2021; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020; Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Hamama-Raz et al., 2021; Jacques-Avino et al., 2020; Kakaje et al., 2021; Msherghi et al., 2021; Pieh et al., 2020; Pinedo et al., 2021; Ramiz et al., 2021; Rossi et al., 2020), and younger age (Alleaume et al., 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2021; Msherghi et al., 2021; Pieh et al., 2020; Pinedo et al., 2021; Ramiz et al., 2021; Rossi et al., 2020) and prior mental health history seems to be additional risk factors (Alleaume et al., 2021; Antiporta et al., 2021; Bell et al., 2021; Castellini et al., 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; De Pietri and Chiorri, 2021; Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Hamama-Raz et al., 2021; Kopishinskaia et al., 2021; Kulig et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2021). However, the literature manifests a number of problems and drawbacks and the current study will try to fill the gaps. First of all, the research methodology varies greatly among studies, it is very difficult to make comparisons among countries and it is also difficult to arrive at universally valid conclusions. A second additional problem is that they deal with symptomatology as a continuum and fail to identify probable clinical cases. The current paper will apply a reliable and already tested algorithm to detect rates of clinical depression. Finally, the literature is full of opinion papers, viewpoints, perspectives, guidelines and narrations of activities to cope with the pandemic. These articles borrow from previous experience with different pandemics and utilize common sense, but, as a result, they often obscure rather than clarify the landscape.

The aim of the current study was to investigate the rates of dysphoria, probable clinical depression and suicidality and their changes in the adult population aged 18–69, during the COVID-19 pandemic in relationship with perceived lockdown degree. Secondary aims were to investigate the contributing effect of various factors specifically in combination with lockdown. The data came from the large international COMET-G study (Fountoulakis et al., 2021b).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Method

The protocol used, is available in the webappendix of a previously published study (Fountoulakis et al., 2021b).; each question was given an ID code; these ID codes were used throughout the results for increased accuracy.

According to a previously developed method, (Fountoulakis et al., 2001, 2021a, 2012) the cut-off score 23/24 for the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale and a derived algorithm were used to identify cases of probable depression. This algorithm utilized the weighted scores of selected CES-D items in order to arrive at the diagnosis of depression, and has already been validated. Cases identified by only either method, were considered cases of dysphoria (false positive cases in terms of depression), while cases identified by both the cut-off and the algorithm were considered as probable depression. The State-Trait Anxiety Inventory S version (STAI-S) (Spielberger, 2005) and the Risk Assessment for Suicidality Scale (RASS) (Fountoulakis et al., 2012) were used to assess anxiety and suicidality respectively.

The degree of lockdown was assessed with a simple question: ‘Are you currently locked up in the house?’ (Completely-To a high degree-Partially-Not at all). Seven questions pertaining to beliefs in conspiracy theories (1. vaccine was ready even before the virus broke out 2. the virus was created in a laboratory as a biochemical weapon and 3. to create a global economic crisis, 4. it did not appeared accidentally from human contact with animals, 5. relationship to 5 G, 6. mortality is lower than announced and 7. the pandemic is a sign of divine power to destroy our planet) were rated on a five point scale from ‘I don't believe it at all’ to ‘I believe it very much’. They were utilized in the analysis separately, not as a single combined score. Information concerning family and working, general health status and other topics were obtained by single direct questions and the information was based on the self-reporting by the subject.

The study research protocol can be found in full in the appendix of a previous publication (Fountoulakis et al., 2021b).The data were collected online and anonymously from April 2020 through March 2021, covering periods of full implementation of lockdowns as well as of relaxations of measures in countries around the world. Announcements and advertisements were done in the social media and through news sites, but no other organized effort had been undertaken. The first page included a declaration of consent which everybody accepted by continuing with the participation.

Approval was initially given by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece and locally concerning each participating country.

2.2. Material

The study sample included data from 40 countries (Fig. 1 ) concerning 55,589 responses to the online questionnaire. The contribution of each country and the gender and age composition as well as details concerning various sociodemographic variables (marital status, education, work etc.) have been included in the original publication (Fountoulakis et al., 2021b).

Fig. 1.

Map of the 40 participating countries.

The study population was self-selected. The study was advertised through the social media so that the population was informed and encouraged to participate. It was not possible to apply post-stratification on the sample as it was done in a previous study (Fountoulakis et al., 2021a), because this would mean that we would utilize a similar methodology across much different countries and the population data needed were not available for all.

2.3. Statistical analysis

-

•

The Relative Risk (RR) was calculated at each level of lockdown degree and its confidence intervals have been calculated also

-

•

Factorial ANOVA was performed to test for differences among groups and the interaction between grouping variables. The Scheffe test was used for post-hoc comparisons.

-

•

Multiple backwards stepwise linear regression analysis (MBSLRA) was performed to investigate whether the psychometric scores and self-reported changes in depression, anxiety and suicidality could be predicted by lockdown degree. The analysis included a number of other variables as well, in order to rule out confounding effects. Concerning gender, only females (0) and males (1) were used in this analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics

The study sample included data from 40 countries. In total responses were gathered from 55,589 participants, aged 35.45±13.51 years old; 36,047 females (64.84%; aged 35.80±13.61) and 18,927 males (34.05%; aged 34.90±13.29), while 615 declared ‘non-binary gender’ (1.11%; aged 31.64±13.15). One third of the study sample was living in the country's capital and an additional almost one fifth in a city of more than one million inhabitants. Half were married or living with someone while 10.41% were living alone. Half had no children at all and approximately 75% had bachelor's degree or higher. In terms of employment, 23.54% were civil servants, 37.06% were working in the private sector, 18.35% were college or university students while the rest were retired or were not working for a variety of reasons; of these 33.86% did not work during lockdowns. The detailed composition of the study sample in terms of country by gender by age as well as in terms or residency, marital status, household size, children, education and occupation and their mental history and present mental status in terms of the presence of current clinical depression have been reported previously (Fountoulakis et al., 2021b).

The proportion of participants by gender and level of lockdown they were experiencing during the survey and at the time they were filling the questionnaire is shown in table 1 , in table 2 the respected percentages are shown by country. Approximately two-thirds were currently living under significant restrictions due to lockdown.

Table 1.

Numbers and percentages of participants by gender and level of lockdown they were experiencing during the survey and at the time they were filling the questionnaire.

| Gender | Lockdown status | N | % of Gender |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Not at all | 4428 | 12.28 |

| Partially | 7658 | 21.25 | |

| To a high degree | 15,436 | 42.82 | |

| Completely | 8523 | 23.65 | |

| Total | 36,045 | 100.00 | |

| Male | Not at all | 3640 | 19.23 |

| Partially | 4758 | 25.14 | |

| To a high degree | 6794 | 35.90 | |

| Completely | 3733 | 19.73 | |

| Total | 18,925 | 100.00 | |

| Non-binary gender | Not at all | 66 | 10.73 |

| Partially | 110 | 17.89 | |

| To a high degree | 262 | 42.60 | |

| Completely | 177 | 28.78 | |

| Total | 615 | 100.00 | |

| All genders | Not at all | 8134 | 14.63 |

| Partially | 12,526 | 22.53 | |

| To a high degree | 22,492 | 40.46 | |

| Completely | 12,433 | 22.37 | |

| Total | 55,585 | 100.00 |

Table 2.

Percentages of participants by country and level of lockdown they were experiencing during the survey and at the time they were filling the questionnaire.

| Country | not at all (%) | Partially (%) | To a high degree(%) | Completely (%) | Total N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Argentina | 3.72 | 18.58 | 51.79 | 25.92 | 2180 |

| Australia | 8.70 | 31.88 | 44.93 | 14.49 | 69 |

| Azerbaijan | 7.67 | 23.86 | 45.74 | 22.73 | 352 |

| Bangladesh | 3.13 | 11.70 | 49.19 | 35.97 | 3033 |

| Belarus | 10.80 | 25.98 | 50.96 | 12.26 | 1093 |

| Brazil | 2.34 | 11.21 | 46.73 | 39.72 | 214 |

| Bulgaria | 16.12 | 31.85 | 39.84 | 12.19 | 763 |

| Canada | 16.80 | 31.05 | 42.19 | 9.96 | 512 |

| Chile | 3.42 | 17.70 | 46.89 | 31.99 | 322 |

| Croatia | 12.49 | 29.70 | 44.60 | 13.21 | 2899 |

| Egypt | 5.45 | 16.36 | 40.61 | 37.58 | 165 |

| France | 14.83 | 22.81 | 38.40 | 23.95 | 263 |

| Georgia | 1.69 | 12.80 | 42.27 | 43.24 | 414 |

| Germany | 1.67 | 43.33 | 50.00 | 5.00 | 60 |

| Greece | 4.56 | 12.76 | 52.37 | 30.31 | 3418 |

| Honduras | 10.86 | 26.24 | 40.27 | 22.62 | 221 |

| Hungary | 12.06 | 29.36 | 46.92 | 11.66 | 763 |

| India | 20.85 | 25.62 | 20.79 | 32.75 | 4989 |

| Indonesia | 3.38 | 27.04 | 52.77 | 16.81 | 3284 |

| Israel | 41.67 | 12.50 | 31.94 | 13.89 | 144 |

| Italy | 2.86 | 27.04 | 39.18 | 30.92 | 980 |

| Japan | 3.85 | 35.00 | 55.00 | 6.15 | 260 |

| Kyrgyz Republic | 9.49 | 20.84 | 34.99 | 34.67 | 2212 |

| Latvia | 72.35 | 14.84 | 9.43 | 3.37 | 2608 |

| Lithuania | 91.26 | 4.69 | 1.59 | 2.46 | 1258 |

| Malaysia | 5.61 | 20.25 | 52.23 | 21.91 | 963 |

| Mexico | 4.54 | 25.08 | 53.86 | 16.52 | 1786 |

| Nigeria | 17.17 | 42.06 | 21.42 | 19.34 | 1153 |

| Pakistan | 5.84 | 17.68 | 45.38 | 31.09 | 2036 |

| Peru | 5.16 | 28.39 | 52.26 | 14.19 | 155 |

| Poland | 19.62 | 30.93 | 40.55 | 8.90 | 1539 |

| Portugal | 3.53 | 34.12 | 43.53 | 18.82 | 85 |

| Romania | 13.46 | 36.16 | 44.44 | 5.94 | 1449 |

| Russia | 7.84 | 21.84 | 45.98 | 24.34 | 9936 |

| Serbia | 50.83 | 23.93 | 21.29 | 3.96 | 606 |

| Spain | 3.76 | 14.37 | 30.76 | 51.11 | 1037 |

| Turkey | 5.19 | 7.20 | 49.28 | 38.33 | 347 |

| Ukraine | 9.92 | 30.10 | 46.83 | 13.15 | 1452 |

| UK | 28.75 | 36.25 | 28.13 | 6.88 | 160 |

| USA | 25.92 | 38.63 | 31.78 | 3.67 | 409 |

| All Countries | 14.64 | 22.54 | 40.46 | 22.37 | 55,589 |

3.2. Psychometric results

The responses to the questions whether their anxiety, mood or suicidal thoughts changed as well as their scores in the psychometric scales by gender and degree of lockdown are shown in table 3 . Factorial ANOVA with gender and lockdown degree as grouping variables and the scale scores for anxiety, depression and suicidality as independent variables, suggested that there was a significant effect of both gender (Wilks: 0.971; F = 276.1; effect df=6, error df=70,115; p<0.001) and lockdown degree (Wilks: 0.999; F = 7.0; effect df=9, error df=79,331; p<0.001) as well as for their interaction (Wilks: 0.999; F = 3.6; effect df=18, error df=88,035; p<0.001)). The scheffe post hoc tests revealed significant differences among all comparisons except those concerning ‘non-binary gender’ under ‘no lockdown at all’, which did not differ from any other group in terms of CES-D and STAI and non-binary gender under partial lockdown which did not differ from the rest groups in terms of STAI.

Table 3.

Mean responses to the questions whether anxiety, mood or suicidal thoughts changed as well as mean scores in the psychometric scales by gender and degree of lockdown. Factorial ANOVAs with gender (only males/females) and lockdown degree as grouping factors and each of the 8 columns as dependent variables returned significant effects for both gender and lockdown degree as well as for their interaction.

| Lockdownstatus | Gender |

Change in |

STAI |

CES-D |

RASS standardized |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Anxiety |

Depression |

Suicidality |

Intention scale |

Life scale |

History scale |

||||||||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| Not at all | Female | −0.42 | 0.84 | −0.25 | 0.82 | 0.01 | 0.66 | 43.51 | 12.38 | 19.00 | 8.91 | 63.88 | 125.35 | 175.77 | 93.53 | 54.79 | 66.67 |

| Male | −0.23 | 0.84 | −0.17 | 0.88 | −0.01 | 0.80 | 39.54 | 11.28 | 16.88 | 7.82 | 70.06 | 133.73 | 162.16 | 95.78 | 46.46 | 69.97 | |

| NBG | −0.11 | 1.29 | −0.17 | 1.22 | 0.14 | 1.18 | 39.88 | 12.60 | 21.52 | 9.78 | 186.44 | 202.42 | 182.35 | 101.80 | 104.02 | 106.59 | |

| Partially | Female | −0.45 | 0.85 | −0.32 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.76 | 44.45 | 12.76 | 20.34 | 8.86 | 81.52 | 144.92 | 164.65 | 102.26 | 67.15 | 73.81 |

| Male | −0.30 | 0.86 | −0.28 | 0.89 | 0.02 | 0.85 | 41.18 | 11.68 | 18.47 | 7.93 | 84.50 | 147.22 | 160.91 | 97.49 | 58.74 | 72.34 | |

| NBG | −0.25 | 1.24 | −0.46 | 1.06 | 0.15 | 0.95 | 40.52 | 12.75 | 24.95 | 10.46 | 215.18 | 202.32 | 226.00 | 96.60 | 109.73 | 96.95 | |

| To a high degree | Female | −0.56 | 0.87 | −0.42 | 0.88 | 0.04 | 0.76 | 44.94 | 13.55 | 21.77 | 9.40 | 96.58 | 154.72 | 168.69 | 105.01 | 74.10 | 73.19 |

| Male | −0.43 | 0.88 | −0.34 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.85 | 42.04 | 12.42 | 19.75 | 8.50 | 105.86 | 160.89 | 173.52 | 100.12 | 68.71 | 73.74 | |

| NBG | −0.26 | 1.25 | −0.20 | 1.23 | −0.16 | 1.16 | 41.98 | 13.45 | 23.60 | 9.74 | 190.59 | 201.97 | 204.43 | 99.83 | 112.39 | 84.38 | |

| Completely | Female | −0.58 | 0.96 | −0.46 | 0.97 | 0.07 | 0.88 | 45.77 | 14.03 | 22.81 | 10.09 | 104.40 | 159.59 | 169.76 | 106.95 | 81.39 | 76.98 |

| Male | −0.48 | 1.04 | −0.45 | 1.06 | 0.15 | 1.00 | 41.49 | 12.77 | 19.95 | 8.80 | 106.62 | 159.69 | 171.97 | 98.60 | 71.46 | 80.55 | |

| NBG | −0.58 | 1.08 | −0.57 | 1.12 | 0.29 | 1.11 | 38.73 | 14.06 | 23.22 | 11.12 | 204.66 | 199.86 | 215.93 | 93.68 | 106.16 | 92.68 | |

| Not at all | All genders | −0.33 | 0.85 | −0.21 | 0.85 | 0.00 | 0.73 | 41.70 | 12.06 | 18.07 | 8.52 | 67.64 | 130.41 | 169.73 | 94.85 | 51.46 | 68.85 |

| Partially | −0.39 | 0.86 | −0.31 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.80 | 43.17 | 12.46 | 19.67 | 8.60 | 100.48 | 157.59 | 170.56 | 103.58 | 72.92 | 73.66 | |

| To a high degree | −0.52 | 0.88 | −0.39 | 0.89 | 0.04 | 0.79 | 44.03 | 13.29 | 21.18 | 9.19 | 106.49 | 160.68 | 171.08 | 104.47 | 78.76 | 78.51 | |

| Completely | −0.55 | 0.99 | −0.46 | 1.00 | 0.09 | 0.92 | 44.38 | 13.82 | 21.96 | 9.83 | 83.82 | 146.91 | 163.77 | 100.60 | 64.33 | 73.72 | |

| All intensities | Female | −0.52 | 0.89 | −0.39 | 0.89 | 0.03 | 0.78 | 44.86 | 13.38 | 21.37 | 9.48 | 91.21 | 151.09 | 168.95 | 103.60 | 71.97 | 73.91 |

| Male | −0.37 | 0.91 | −0.31 | 0.93 | 0.04 | 0.87 | 41.23 | 12.13 | 18.92 | 8.37 | 93.75 | 153.04 | 167.86 | 98.50 | 62.47 | 74.64 | |

| NBG | −0.33 | 1.21 | −0.35 | 1.18 | 0.06 | 1.13 | 40.56 | 13.46 | 23.51 | 10.30 | 198.59 | 201.24 | 209.23 | 98.27 | 109.22 | 91.49 | |

| All Grps | −0.47 | 0.90 | −0.36 | 0.91 | 0.04 | 0.82 | 43.58 | 13.08 | 20.56 | 9.21 | 93.27 | 152.81 | 169.03 | 101.92 | 69.15 | 74.63 | |

Note: NBG stands for Non-Binary gender.

Scoring for change in anxiety, depression or suicidality:.

−2 = Much worse; −1 = Worse; 0 = It has not changed; 1 = A little better; 2 = Much better.

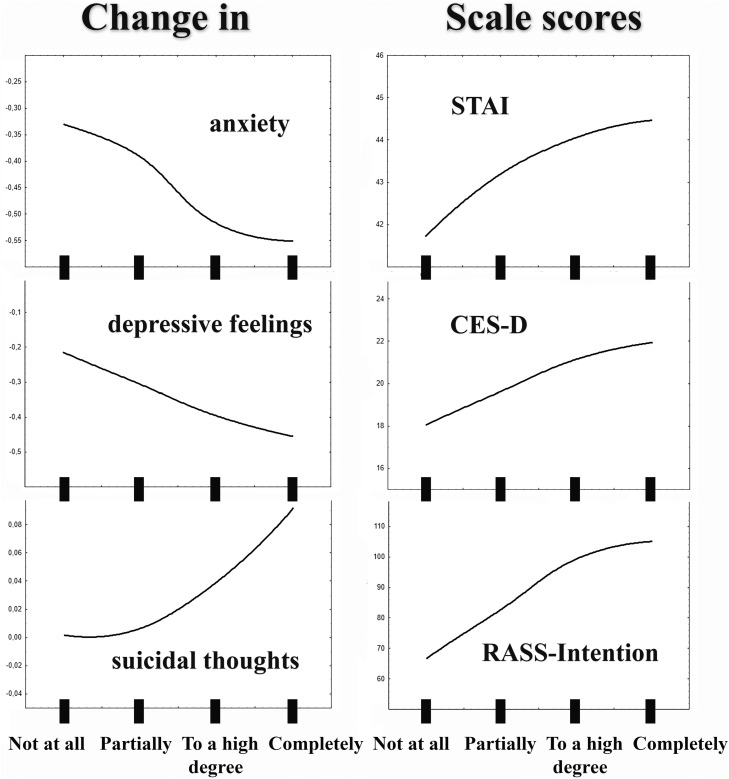

These results suggest that with the intensifying of lockdown, changes in anxiety, depression and suicidality increase, especially in females concerning anxiety and depression and in males concerning suicidality. In Fig. 2 the charts of changes in anxiety, depressive feelings and suicidal thoughts and scale scores for anxiety, depression and suicidality are shown, plotted vs. the degree of lockdown. The curves were plotted on the basis of distance-weighted least squares method

Fig. 2.

Charts of changes in anxiety, depressive feelings and suicidal thoughts (left) and scale scores (right) for anxiety (STAI), depression (CES-D) and suicidality (RASS-Intention) plotted vs. the degree of lockdown (x-axis). The curves were plotted on the basis of distance-weighted least squares method.

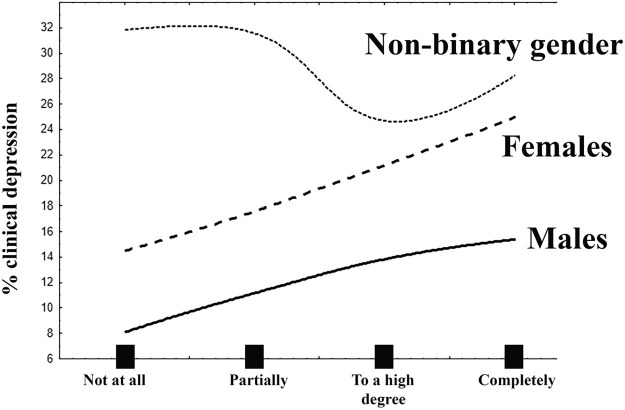

3.3. Rates of dysphoria and probable depression and RR

In table 4 the rates of clinical depression and dysphoria are shown again by gender and lockdown degree. In Fig. 3 the plot of probable depression rates in the three gender groups are shown vs. the degree of lockdown. The curves were plotted on the basis of distance-weighted least squares method. Males and females manifested a similar RR which was significant and significantly different from that of persons with ‘non-binary gender’ whose depressions did not seem to be affected by lockdown degree, but it should be noted that their rates under ‘not at all’ lockdown are already higher than those of males or females under ‘complete’ lockdown. For both males and females the risk to develop clinical depression increases significantly with each and every level of increasing lockdown degree (table 4), and the RR is 1.72 and 1.90 respectively. In table 5 the rates of probable depression and dysphoria are shown by history of any mental disorder or suicidality. The lower rate of probable depression is for subjects without any mental health history and not under any lockdown (7.40%) and it is escalating to 50.79% for subjects with both mental health history and both history of self-harm and suicidal attempts under complete lockdown (RR for the combined total effect equal to 6.88 with 95% CI 6.08–7.78 (table 5)

Table 4.

Percentages of dysphoria and clinical depression and Risk Ratio at each level of increasing lockdown degree for the development of clinical depression. For males and females the risk is significant at every level while for non-binary gender is not at any level.

| Gender | Lockdown status | No depression or dysphoria (%) | Dysphoria (%) | Clinical Depression (%) | Either Depression or Dysphoria (%) | RR (95% CI)concerning depression | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Not at all | 71.75 | 13.78 | 14.48 | 28.25 | 1.72 (1.59–1.87)1 | |||||

| Partially | 66.94 | 15.47 | 17.59 | 33.06 | 1.22 (1.11–1.32)2 | ||||||

| To a high degree | 60.50 | 18.31 | 21.19 | 39.50 | 1.20 (1.14–1.28)3 | ||||||

| Completely | 55.64 | 19.42 | 24.94 | 44.36 | 1.18 (1.12–1.23)4 | ||||||

| Total | 62.10 | 17.41 | 20.49 | 37.90 | |||||||

| Male | Not at all | 80.85 | 11.07 | 8.08 | 19.15 | 1.90 (1.66–2.17)1 | |||||

| Partially | 74.19 | 14.65 | 11.16 | 25.81 | 1.38 (1.21–1.58)2 | ||||||

| To a high degree | 69.19 | 16.96 | 13.85 | 30.81 | 1.24 (1.12–1.37)3 | ||||||

| Completely | 68.04 | 16.58 | 15.38 | 31.96 | 1.11(1.01–1.22)4 | ||||||

| Total | 72.46 | 15.17 | 12.36 | 27.54 | |||||||

| Non-Binary gender | Not at all | 60.61 | 7.58 | 31.82 | 39.39 | 0.89 (0.58–1.36)1 | |||||

| Partially | 42.73 | 25.45 | 31.82 | 57.27 | 1.00 (0.64–1.56)2 | ||||||

| To a high degree | 49.24 | 26.34 | 24.43 | 50.76 | 0.77 (0.54–1.09)3 | ||||||

| Completely | 49.15 | 22.60 | 28.25 | 50.85 | 1.16 (0.84–1.59)4 | ||||||

| Total | 49.27 | 23.09 | 27.64 | 50.73 | |||||||

| Total | 65.49 | 16.71 | 17.80 | 34.51 | |||||||

Significant RR values are in bold underlined italics.

RR between ‘not at all’ vs. ‘complete’ lockdown.

RR between ‘not at all’ vs. ‘partially’ lockdown.

RR between ‘partially’ vs. ‘to a high degree’ lockdown.

RR between ‘to a high degree’ vs. ‘complete’ lockdown.

Fig. 3.

Plot of probable depression rates in the three gender groups vs. the degree of lockdown (x-axis). The curves were plotted on the basis of distance-weighted least squares method.

Table 5.

Rates of dysphoria and probable depression by lockdown degree and history of mental disorder.

| Lockdown degree | History of mental disorder, self-harm and suicidality | Dysphoria | Probable depression | Either dysphoria or probable depression |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at all | No history at all | 9.73 | 7.40 | 17,13 |

| His-or SH or SA (1/3) | 16.40 | 18.32 | 34,72 | |

| His-or SH or SA (2/3) | 22.83 | 21.17 | 44,00 | |

| His-and SH and SA (3/3) | 24.51 | 43.08 | 67,59 | |

| Total | 12.52 | 11.75 | 24,27 | |

| Partially | No history at all | 11.41 | 8.75 | 20,16 |

| His-or SH or SA (1/3) | 20.23 | 20.03 | 40,27 | |

| His-or SH or SA (2/3) | 23.53 | 32.70 | 56,23 | |

| His-and SH and SA (3/3) | 26.18 | 48.03 | 74,21 | |

| Total | 15.25 | 15.27 | 30,52 | |

| To a high degree | No history at all | 13.87 | 11.81 | 25,69 |

| His-or SH or SA (1/3) | 22.19 | 24.39 | 46,58 | |

| His-or SH or SA (2/3) | 28.09 | 34.59 | 62,68 | |

| His-and SH and SA (3/3) | 26.25 | 49.16 | 75,42 | |

| Total | 17.99 | 19.01 | 37,00 | |

| Completely | No history at all | 15.41 | 13.55 | 28,95 |

| His-or SH or SA (1/3) | 21.84 | 28.10 | 49,94 | |

| His-or SH or SA (2/3) | 24.20 | 38.06 | 62,26 | |

| His-and SH and SA (3/3) | 24.60 | 50.79 | 75,40 | |

| Total | 18.61 | 22.12 | 40,73 | |

| Column Total | 16.71 | 17.80 | 34.51 | |

•His-or SH or SA (1/3): one of the following: history of any mental disorder, history of self-harm or history of suicidal attempt.

•His-or SH or SA (2/3): two of the following: history of any mental disorder, history of self-harm or history of suicidal attempt.

•His-and SH and SA (3/3): all of the following: history of any mental disorder, history of self-harm or history of suicidal attempt.

The two extreme rates of probable depression (no lockdown and no history at all; 7.40% vs. complete lockdown and 3/3 history; 50.79%) are marked in bold underlined italics.

3.4. Factors interacting with lockdown to affect mental health

The coefficients b in parentheses stand for standardized coefficients (also called beta).

MBSLRA with the CES-D score as dependent variable (R = 0.453, F = 987,7340, R²=0.205, df = 12,45,838; p<0.001) returned significant results for the degree of the lockdown (b = 0.06) and additionally for gender (male b=−0.08), age (b=−0.13), any history of mental disorder (b = 0.22), general condition of health (b=−0.25), continue working during lockdown (b=−0.02), believing in conspiracy theories (b ranging from −0.02–0.06) and number of children (b=−0.03). The number of persons in the household was not significant.

MBSLRA with the STAI score as dependent variable (R = 0.348, F = 528,9351, R²=0.121, df = 12,45,839; p<0.001) returned significant results for the degree of the lockdown (b = 0.03), and additionally for gender (male b=−0.9), age (b = 0.4), any history of mental disorder (b = 0.14), general condition of health (b=−0.22), number of children (b=−0.07), number of persons in the household (b = 0.09) and believing in some conspiracy theories (b ranging from −0.02–0.07). There was no effect of continuing to work during lockdown.

MBSLRA with the RASS Intention score as dependent variable (R = 0.394, F = 767,9869, R²=0.155, df = 11,458; p<0.001) returned significant results for degree of lockdown (b = 0.21), gender (male b = 0.02), age (b=−0.26), any history of mental disorder (b = 0.18), number of children (b=−0.02), number of persons in the household (b=−0.05) and believing in some conspiracy theories (b ranging from −0.04–0.08). There was no significant contribution by the general condition of health or of continuing to work during lockdown.

MBSLRA with the presence of probable depression (yes/no) as dependent variable (R = 0.333, F = 575,2150, R²=0.111, df = 10,45,837; p<0.001) returned significant results for the degree of the lockdown (b = 0.04), as well as for gender (male b=−0.7), age (b=−0.08), any history of mental disorder (b = 0.17), general condition of health (b=−0.19), and believing in some conspiracy theories (b ranging from −0.02–0.03). There was no significant contribution of the number of persons in the household, number of children or of continuing to work during lockdown.

MBSLRA with changes in depression (−2 to +2) as dependent variable (R = 0.239, F = 349,5308, R²=0.057, df = 8,45,843; p<0.001) returned significant results for the degree of the lockdown (b=−0.06), as well as age (b = 0.05), any history of mental disorder (b=−0.06), general condition of health (b = 0.19), number of persons in the household (b = 0.02), number of children (b = 0.02), continuing to work during lockdown (b = 0.02) and believing in some conspiracy theories (b equal to 0.02). There was no significant contribution of gender.

MBSLRA with changes in anxiety (−2 to +2) as dependent variable (R = 0.274, F = 340,0370, R²=0.075, df = 11,45,840; p<0.001) returned significant results for the degree of the lockdown (b=−0.06), as well as sex (b = 0.04), age (b = 0.02), any history of mental disorder (b=−0.06), general condition of health (b = 0.22), number of persons in the household (b = 0.02), continuing to work during lockdown (b = 0.02) and believing in some conspiracy theories (b ranging from −0.03 to 0.04). There was no significant contribution of number of children.

MBSLRA with changes in suicidality (−2 to +2) as dependent variable (R = 0.136, F = 87,20,290, R²=0.018, df = 10,45,841; p<0.001) returned significant results for the degree of the lockdown (b=−0.02), as well as sex (b = 0.02), age (b=−0.06), any history of mental disorder (b = 0.04), general condition of health (b=−0.08), number of persons in the household (b=−0.03), (and believing in some conspiracy theories (b ranging from −0.04 to 0.02). There was no significant contribution of continuing to work during lockdown and number of children.

The results of all the above MBSLRA analyses are shown in table 6 . Taken together, these results suggest that the lockdown has a clear although very weak adverse effect on the mental state of the general population, which also depends on the intensity of lockdown. Females are at a higher risk as are younger individuals who live alone and families without children. The presence of past mental health history is a significant risk factor while adherence to conspiracism has a variable effect. However, overall the combined contribution of all these variables is rather small.

Table 6.

The effect of lockdown degree/intensity on mental health.

| Factor | Probable depression | Depressive symptomatology | Anxiety | Suicidal thoughts | Change indepression | Change inanxiety | Change insuicidality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lockdown degree/intensity | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Stopped working during lockdown | + | + | + | ||||

| Female gender | + | – | + | + | + | – | |

| Age | – | – | + | – | – | – | – |

| Number of children | – | – | – | – | |||

| Number of persons in household | + | – | – | – | – | ||

| Bad condition of general health | + | + | + | + | + | + | |

| Presence of any history of mental disorder | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Conspiracism | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- | +/- |

| Variance explained by Lockdown degree* | 0.8% | 1.9% | 0.4% | 0.7% | 0.7% | 0.8% | 0.1% |

| Total variance explained | 11.1% | 20.5% | 12.1% | 15.5% | 5.7% | 7.5% | 1.8% |

| Contribution of lockdown degree to explained variable | 7.2% | 9.2% | 3.3% | 4.5% | 12,3% | 10,6% | 5,5% |

+ increased by factor/positive correlation.

- decreased by factor/negative correlation.

+/- variable relationship.

* with univariate regression.

4. Discussion

This large international study in convenience sample of 55,589 participants from 40 countries reports that lockdown significantly increases depression at every degree of lockdown intensity for males and females but not for those with non-binary gender. It is probably the first to specifically show that the lockdown degree is positively related with an increase in anxiety, depressive symptoms and suicidality thoughts as well as in the rates of probable depression after correcting for other effects (via the MbSLRA analysis). The interaction of strict lockdown with history of mental illness and suicidal attempts increases the risk to depression almost seven times. However, the overall effect of lockdown, though significant is small and explains for 0.4% of anxiety, 1.9% of depressive symptoms, 0.8% of probable depression and 0.7% of suicidal thoughts variability.

The literature so far suggests that during lockdowns there is a deterioration of mental health in general. Although there are no reliable assessments of clinical cases of depression, anxious and depressive symptomatology are reported to increase with 30–50% of subjects experiencing significant elevations (Al-Ajlouni et al., 2020; Antiporta et al., 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; De Pietri and Chiorri, 2021; Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Jacques-Avino et al., 2020; Kakaje et al., 2021; Khubchandani et al., 2021; Killgore et al., 2021; Kopilas et al., 2021; Mary-Krause et al., 2021; Msherghi et al., 2021; Pandey et al., 2020; Pieh et al., 2020; Ramiz et al., 2021; Simon et al., 2021; Smirnova et al., 2021; Surina et al., 2021; Vrublevska et al., 2021b). Somatoform symptoms are also prevalent (Ben-Ezra et al., 2021; Mary-Krause et al., 2021). The increase concerned more the internalizing and to a much less extend the interpersonal symptoms (Castellini et al., 2021). The most common pattern seemed to be an admixture of all the above symptoms (Di Blasi et al., 2021).

At least moderate depression is reported in almost 20% (Al-Ajlouni et al., 2020; Pieh et al., 2020) and more that 10% have seek professional help for mental health issues during the lockdown and particularly because of the lockdown (Alleaume et al., 2021). These results are in accord with the findings of the current study. The increase in risk is reported to be 6.73 for depression (Andersen et al., 2021a), but our results suggest a much lower effect of lockdown alone (risk below 2). The risk rises above 6 only in the presence of severe history of mental disorders and suicidality.

Suicidality was also reported to increase with 4–20% reporting suicidal ideation, and 2–10% reporting having seriously considered suicide (Bell et al., 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; Efstathiou et al., 2021; Every-Palmer et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2021). The results of the current study do confirm this; high suicidality scores were detected, and this rise in suicidality was found to be the result of the interaction of lockdown with other factors, including gender and the presence of psychiatric and medical history.

Early meta-analyses found a small effect of lockdown on mental health (g = 0.17) and substantial heterogeneity among studies, thus concluding that most people are psychologically resilient to their effects (Prati and Mancini, 2021). Interestingly, some authors reported that negative affect decreased during lockdowns, which is suggestive of a differential effect of lockdowns on different population groups especially with respect to prior mental health (Foa et al. (2022); Recchi et al., 2020). These reports are in accord with the findings of the current study, which suggest a significant but weak effect of lockdown on mental health as the explained variance is very low (below 2% for depressive symptoms).

With the end of lockdowns, it seems that at least for half of those persons who previously were free of mental health history, the anxious and depressive symptomatology recovered quickly but in a significant proportion they persisted (Ahrens et al., 2021; Di Blasi et al., 2021). A habituation effect was also reported (Fancourt et al., 2021). The development and course as well as the outcome after the resolution of the lockdown are reported to be influenced by a number of factors. Gender is the most frequently reported such factor with females being at a higher risk, and this is in accord with our findings (Andersen et al., 2021a; Cruyt et al., 2021; De Pietri and Chiorri, 2021; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020; Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Hamama-Raz et al., 2021; Jacques-Avino et al., 2020; Kakaje et al., 2021; Msherghi et al., 2021; Pieh et al., 2020; Pinedo et al., 2021; Ramiz et al., 2021; Rossi et al., 2020). However, in contrast to our report, at least one study reported higher depression rates in males and anxiety in females (Khubchandani et al., 2021). Additionally, people who do not identify with the man/woman binomial (non-binary gender) presented high proportions of anxiety (41.7%) and depression (30.6%) (Jacques-Avino et al., 2021). Our results do not permit conclusions on the long-term course after the resolution of lockdown. However. they support an interaction of gender with lockdown degree, with females being more susceptible to the development of depression and males to the development of anxiety. Interestingly, non-binary gender was unaffected by lockdown, although the baseline mental health indices were substantially worse in comparison to males and females.

The presence of a family with kids, as well as the presence of interpersonal and social relationships were mostly a protective factor (Andersen et al., 2021b; Cruyt et al., 2021; Di Blasi et al., 2021; Domenech-Abella et al., 2021; Killgore et al., 2021; Pinedo et al., 2021); however one study reported the opposite (Khubchandani et al., 2021) and the relationship seems rather complex (Msherghi et al., 2021; Ramiz et al., 2021). Our results (table 6) suggest that the presence of children protects from the development of anxiety, dysphoria and suicidality but not from the development of clinical depression while having a family increases baseline anxiety but protects from increases in anxiety, depression and suicidality.

Prior history of mental disorder is identified as an important risk factor for the development of depression and other mental disorders during lockdown (Alleaume et al., 2021; Antiporta et al., 2021; Bell et al., 2021; Castellini et al., 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; De Pietri and Chiorri, 2021; Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Hamama-Raz et al., 2021; Kopishinskaia et al., 2021; Kulig et al., 2020; Simon et al., 2021) and this is strongly supported by our results. Essentially the presence of mental history is what skyrockets the adverse effects of lockdown. Other risk factors inlcude specific personality traits (Di Blasi et al., 2021; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020; Domenech-Abella et al., 2021; Landi et al., 2020; Rossi et al., 2021; Veer et al., 2021), economic and professional problems and unemployment (Alleaume et al., 2021; Antiporta et al., 2021; Castellini et al., 2021; De Pietri and Chiorri, 2021; Jacques-Avino et al., 2021; Kakaje et al., 2021; Khubchandani et al., 2021; Killgore et al., 2021; Msherghi et al., 2021; Pieh et al., 2020) as well as the low socioeconomic status (Antiporta et al., 2021; De Pietri and Chiorri, 2021; Khubchandani et al., 2021; Pieh et al., 2020).

Younger age is reported to act as another risk factor (Alleaume et al., 2021; Czeisler et al., 2021; Di Giuseppe et al., 2020; Killgore et al., 2021; Msherghi et al., 2021; Pieh et al., 2020; Pinedo et al., 2021; Ramiz et al., 2021; Rossi et al., 2020) as well as the presence of a chronic medical condition (Antiporta et al., 2021; Cruyt et al., 2021; Jacques-Avino et al., 2021; Ramiz et al., 2021) especially when accompanied by significant disability (Czeisler et al., 2021). The effect of both these factors was confirmed by our results. Younger age acts as a risk factor for depression and suicidality but advanced age as a risk factor for the development of anxiety. This age effect is in accord with one study, which suggested that also advanced age constitutes a risk factor (Ramiz et al., 2021). Often these risk factors tend to accumulate on the same person and lead to ultra-high risk population groups (Bell et al., 2021).

Apart from intensity, also the duration of the lockdown was reported to be an additional risk factor (Di Giuseppe et al., 2020; Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Killgore et al., 2020), although a negative report exists also (Pinedo et al., 2021), Repeated or intermittent lockdowns did not seem to worsen mental health as the same people seemed to be affected (Efstathiou et al., 2021). There was one report suggesting that the degree of the lockdown was related to deteriorating mental health (Benke et al., 2020), and this is clearly in accord with our findings.

At pandemic onset we might not had imagined the important role and the impact of conspiracy theories, which are largely social media driven. They are currently widely accepted as being important since the literature strongly supports their relationship with anxiety and depression (Chen et al., 2020; De Coninck et al., 2021; Elek et al., 2022; Fountoulakis et al., 2021a, 2021b). The current study utilized seven questions pertaining to conspirasism. What is interesting is that the results suggest that the COVID-19 related conspiracy theories exert a complex effect as it has been already mentioned in the publication of the basic COMET-G study results (Fountoulakis et al., 2021b). According to them, conspiracy theories could be classified as being either ‘threatening’ or ‘reassuring’ and these two groups exert different effects at different phases and periods. However they do not seem to interact with the lockdown degree.

A difficult to answer question is how many of the cases detected by questionnaires and sophisticated algorithms correspond to real probable depression. The underlying neurobiology is opaque and maybe much diagnosed depression might simply be an extreme form of a normal adjustment reaction (He et al., 2021). However there is no better way to psychometrically achieve higher validity and the algorithm we utilized is the best available method. However, a large part of depressions emerged from a previous mental health history and this adds validity to our results.

Concerning those without a previous history of mental disorder, it is expected that much of the adverse effects on mental health will rapidly attenuate with the lifting of lockdown restrictions and the end of the pandemic (Daly and Robinson, 2021) but enduring effects will impact some vulnerable populations. So far studies investigating the long-term outcome and the long-term impact of the pandemic on mental health display equivocal findings (Bendau et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2020). Especially sociability and the sense of belonging could be important factors determining mental health and health-related behaviors (Biddlestone et al., 2020), and these factors seem to correspond to specific vulnerabilities seen especially in western cultures.

5. Strengths and limitations

The strengths of the current paper include the large number of persons who filled the questionnaire and the large bulk of information obtained, as well as the detailed way of post-stratification of the study sample.

The major limitation was that the data were obtained anonymously online through self-selection of the responders. The nature and intensity of the lockdown was assessed on the basis of a single simple question. Additionally, the assessment included only the cross-sectional application of self-report scales, although the advanced algorithm used for the diagnosis of probable depression corrected the problem to a certain degree. However, what is included under the umbrella of ‘probable depression’ in the stressful times of the pandemic remains a matter of debate. Also, the lack of baseline data concerning the mental health of a similar study sample before the pandemic is also a problem. Unfortunately the combined contribution of all variables in the models derived were rather small and it seems that other unknown factors play a stronger role.

Other sources of bias include response bias, recall bias and desirability bias.

6. Conclusion

The current paper is probably the first to report that lockdown significantly increases anxiety and depression but not suicidality at every degree of lockdown intensity for males and females but not for those with non-binary gender, especially in combination with the presence of mental health history. However, the overall effect of lockdown, though significant is small. These findings, although they should be closely monitored in a longitudinal way, support previous suggestions by other authors concerning the need for a proactive intervention to protect mental health of the general population but more specifically of vulnerable groups (Fiorillo and Gorwood, 2020; Sani et al., 2020).

Funding

None.

Author contributions

All authors contributed equally to the paper.

KNF and DS conceived and designed the study. The other authors participated formulating the final protocol, designing and supervising the data collection and creating the final dataset. KNF and DS did the data analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors participated in interpreting the data and developing further stages and the final version of the paper.

Prof. Konstantinos N. Fountoulakis and Dr. Daria Smirnova had the original idea, developed the protocol, and coordinated the work groups. All the authors participated in the translation of the protocol into mother languages and in the collection of data. Prof. Konstantinos N. Fountoulakis, Dr. Grigorios N. Karakatsoulis and Dr. Daria Smirnova wrote the first draft. All authors participated in the revision of the first draft. The final manuscript was developed by Prof. Konstantinos N. Fountoulakis, Dr. Grigorios N. Karakatsoulis and Dr. Daria Smirnova and was approved by all authors.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None pertaining to the current paper.

References

- Ahrens K.F., Neumann R.J., Kollmann B., Brokelmann J., von Werthern N.M., Malyshau A., Weichert D., Lutz B., Fiebach C.J., Wessa M., Kalisch R., Plichta M.M., Lieb K., Tuscher O., Reif A. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on mental health in Germany: longitudinal observation of different mental health trajectories and protective factors. Transl. Psych. 2021;11:392. doi: 10.1038/s41398-021-01508-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Ajlouni Y.A., Park S.H., Alawa J., Shamaileh G., Bawab A., El-Sadr W.M., Duncan D.T. Anxiety and depressive symptoms are associated with poor sleep health during a period of COVID-19-induced nationwide lockdown: a cross-sectional analysis of adults in Jordan. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alleaume C., Verger P., Peretti-Watel P., Group C. Psychological support in general population during the COVID-19 lockdown in France: needs and access. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0251707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen A.J., Mary-Krause M., Bustamante J.J.H., Heron M., El Aarbaoui T., Melchior M. Symptoms of anxiety/depression during the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown in the community: longitudinal data from the TEMPO cohort in France. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:381. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03383-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen L.H., Fallesen P., Bruckner T.A. Risk of stress/depression and functional impairment in Denmark immediately following a COVID-19 shutdown. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:984. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-11020-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antiporta D.A., Cutipe Y.L., Mendoza M., Celentano D.D., Stuart E.A., Bruni A. Depressive symptoms among Peruvian adult residents amidst a National Lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21:111. doi: 10.1186/s12888-021-03107-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asmundson G.J.G., Taylor S. Garbage in, garbage out: the tenuous state of research on PTSD in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and infodemic. J. Anxiety Disord. 2021;78 doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell C., Williman J., Beaglehole B., Stanley J., Jenkins M., Gendall P., Rapsey C., Every-Palmer S. Psychological distress, loneliness, alcohol use and suicidality in New Zealanders with mental illness during a strict COVID-19 lockdown. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2021 doi: 10.1177/00048674211034317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ezra M., Hamama-Raz Y., Goodwin R., Leshem E., Levin Y. Association between mental health trajectories and somatic symptoms following a second lockdown in Israel: a longitudinal study. BMJ Open. 2021;11 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendau A., Plag J., Kunas S., Wyka S., Strohle A., Petzold M.B. Longitudinal changes in anxiety and psychological distress, and associated risk and protective factors during the first three months of the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany. Brain Behav. 2021;11:e01964. doi: 10.1002/brb3.1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benke C., Autenrieth L.K., Asselmann E., Pane-Farre C.A. Lockdown, quarantine measures, and social distancing: associations with depression, anxiety and distress at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults from Germany. Psych. Res. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biddlestone M., Green R., Douglas K.M. Cultural orientation, power, belief in conspiracy theories, and intentions to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2020;59:663–673. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castellini G., Rossi E., Cassioli E., Sanfilippo G., Innocenti M., Gironi V., Silvestri C., Voller F., Ricca V. A longitudinal observation of general psychopathology before the COVID-19 outbreak and during lockdown in Italy. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021;141 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhang S.X., Jahanshahi A.A., Alvarez-Risco A., Dai H., Li J., Ibarra V.G. Belief in a COVID-19 conspiracy theory as a predictor of mental health and well-being of health care workers in ecuador: cross-sectional survey study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6:e20737. doi: 10.2196/20737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtet P., Olie E. Suicide in the COVID-19 pandemic: what we learnt and great expectations. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;50:118–120. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruyt E., De Vriendt P., De Letter M., Vlerick P., Calders P., De Pauw R., Oostra K., Rodriguez-Bailon M., Szmalec A., Merchan-Baeza J.A., Fernandez-Solano A.J., Vidana-Moya L., Van de Velde D. Meaningful activities during COVID-19 lockdown and association with mental health in Belgian adults. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:622. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10673-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czeisler M.E., Wiley J.F., Facer-Childs E.R., Robbins R., Weaver M.D., Barger L.K., Czeisler C.A., Howard M.E., Rajaratnam S.M.W. Mental health, substance use, and suicidal ideation during a prolonged COVID-19-related lockdown in a region with low SARS-CoV-2 prevalence. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2021;140:533–544. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2021.05.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M., Robinson E. Anxiety reported by US adults in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic: population-based evidence from two nationally representative samples. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;286:296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Coninck D., Frissen T., Matthijs K., d'Haenens L., Lits G., Champagne-Poirier O., Carignan M.E., David M.D., Pignard-Cheynel N., Salerno S., Genereux M. Beliefs in conspiracy theories and misinformation about COVID-19: comparative perspectives on the role of anxiety, depression and exposure to and trust in information sources. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.646394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Pietri S., Chiorri C. Early impact of COVID-19 quarantine on the perceived change of anxiety symptoms in a non-clinical, non-infected Italian sample: effect of COVID-19 quarantine on anxiety. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2021;4 doi: 10.1016/j.jadr.2021.100078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Blasi M., Gullo S., Mancinelli E., Freda M.F., Esposito G., Gelo O.C.G., Lagetto G., Giordano C., Mazzeschi C., Pazzagli C., Salcuni S., Lo Coco G. Psychological distress associated with the COVID-19 lockdown: a two-wave network analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;284:18–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Zilcha-Mano S., Prout T.A., Perry J.C., Orru G., Conversano C. Psychological impact of coronavirus disease 2019 among italians during the first week of lockdown. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.576597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domenech-Abella J., Gabarrell-Pascuet A., Faris L.H., Cristobal-Narvaez P., Felez-Nobrega M., Mortier P., Vilagut G., Olaya B., Alonso J., Haro J.M. The association of detachment with affective disorder symptoms during the COVID-19 lockdown: the role of living situation and social support. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;292:464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.05.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efstathiou V., Michopoulos I., Yotsidi V., Smyrnis N., Zompola C., Papadopoulou A., Pomini V., Papadopoulou M., Tsigkaropoulou E., Tsivgoulis G., Douzenis A., Gournellis R. Does suicidal ideation increase during the second COVID-19 lockdown? Psychiatry Res. 2021;301 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elek L.P., Szigeti M., Erdelyi-Hamza B., Smirnova D., Fountoulakis K.N., Gonda X. What you see is what you get? Association of belief in conspiracy theories and mental health during COVID-19. Neuropsychopharmacol. Hung. 2022;24:42–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Every-Palmer S., Jenkins M., Gendall P., Hoek J., Beaglehole B., Bell C., Williman J., Rapsey C., Stanley J. Psychological distress, anxiety, family violence, suicidality, and wellbeing in New Zealand during the COVID-19 lockdown: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Steptoe A., Bu F. Trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms during enforced isolation due to COVID-19 in England: a longitudinal observational study. Lancet Psych. 2021;8:141–149. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30482-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorillo A., Gorwood P. The consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and implications for clinical practice. Eur. Psych. 2020;63:e32. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, R., Gilbert, S., Fabian, M.O., (in press). COVID-19 and Subjective Well-Being: Separating the Effects of Lockdowns from the Pandemic. Lancet.

- Fountoulakis K., Iacovides A., Kleanthous S., Samolis S., Kaprinis S.G., Sitzoglou K., St Kaprinis G., Bech P. Reliability, validity and psychometric properties of the Greek translation of the center for epidemiological studies-depression (CES-D) scale. BMC Psych. 2001;1:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-1-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K.N., Apostolidou M.K., Atsiova M.B., Filippidou A.K., Florou A.K., Gousiou D.S., Katsara A.R., Mantzari S.N., Padouva-Markoulaki M., Papatriantafyllou E.I., Sacharidi P.I., Tonia A.I., Tsagalidou E.G., Zymara V.P., Prezerakos P.E., Koupidis S.A., Fountoulakis N.K., Chrousos G.P. Self-reported changes in anxiety, depression and suicidality during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;279:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K.N., Breda J., Arletou M.P., Charalampakis A.I., Karypidou M.G., Kotorli K.S., Koutsoudi C.G., Ladia E.S., Mitkani C.A., Mpouri V.N., Samara A.C., Stravoravdi A.S., Tsiamis I.G., Tzortzi A., Vamvaka M.A., Zacharopoulou C.N., Prezerakos P.E., Koupidis S.A., N K.F., Tsapakis E.M., Konsta A., Theodorakis P.N. Adherence to facemask use in public places during the autumn-winter 2020 COVID-19 lockdown in Greece: observational data. Ann. Gen. Psych. 2022;21:9. doi: 10.1186/s12991-022-00386-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K.N., Fountoulakis N.K., Koupidis S.A., Prezerakos P.E. Factors determining different death rates because of the COVID-19 outbreak among countries. J. Public Health (Oxf) 2020;42:681–687. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K.N., Karakatsoulis G., Abraham S., Adorjan K., Ahmed H.U., Alarcon R.D., Arai K., Auwal S.S., Berk M., Bjedov S., Bobes J., Bobes-Bascaran T., Bourgin-Duchesnay J., Bredicean C.A., Bukelskis L., Burkadze A., Abud I.I.C., Castilla-Puentes R., Cetkovich M., Colon-Rivera H., Corral R., Cortez-Vergara C., Crepin P., De Berardis D., Zamora Delgado S., De Lucena D., De Sousa A., Stefano R.D., Dodd S., Elek L.P., Elissa A., Erdelyi-Hamza B., Erzin G., Etchevers M.J., Falkai P., Farcas A., Fedotov I., Filatova V., Fountoulakis N.K., Frankova I., Franza F., Frias P., Galako T., Garay C.J., Garcia-Alvarez L., Garcia-Portilla M.P., Gonda X., Gondek T.M., Gonzalez D.M., Gould H., Grandinetti P., Grau A., Groudeva V., Hagin M., Harada T., Hasan M.T., Hashim N.A., Hilbig J., Hossain S., Iakimova R., Ibrahim M., Iftene F., Ignatenko Y., Irarrazaval M., Ismail Z., Ismayilova J., Jacobs A., Jakovljevic M., Jaksic N., Javed A., Kafali H.Y., Karia S., Kazakova O., Khalifa D., Khaustova O., Koh S., Kopishinskaia S., Kosenko K., Koupidis S.A., Kovacs I., Kulig B., Lalljee A., Liewig J., Majid A., Malashonkova E., Malik K., Malik N.I., Mammadzada G., Mandalia B., Marazziti D., Marcinko D., Martinez S., Matiekus E., Mejia G., Memon R.S., Martinez X.E.M., Mickeviciute D., Milev R., Mohammed M., Molina-Lopez A., Morozov P., Muhammad N.S., Mustac F., Naor M.S., Nassieb A., Navickas A., Okasha T., Pandova M., Panfil A.L., Panteleeva L., Papava I., Patsali M.E., Pavlichenko A., Pejuskovic B., Pinto Da Costa M., Popkov M., Popovic D., Raduan N.J.N., Ramirez F.V., Rancans E., Razali S., Rebok F., Rewekant A., Flores E.N.R., Rivera-Encinas M.T., Saiz P., de Carmona M.S., Martinez D.S., Saw J.A., Saygili G., Schneidereit P., Shah B., Shirasaka T., Silagadze K., Sitanggang S., Skugarevsky O., Spikina A., Mahalingappa S.S., Stoyanova M., Szczegielniak A., Tamasan S.C., Tavormina G., Tavormina M.G.M., Theodorakis P.N., Tohen M., Tsapakis E.M., Tukhvatullina D., Ullah I., Vaidya R., Vega-Dienstmaier J.M., Vrublevska J., Vukovic O., Vysotska O., Widiasih N., Yashikhina A., Prezerakos P.E., Smirnova D. Results of the COVID-19 mental health international for the general population (COMET-G) study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;54:21–40. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K.N., Karakatsoulis G., Abraham S., Adorjan K., Ahmed H.U., Alarcon R.D., Arai K., Auwal S.S., Berk M., Bjedov S., Bobes J., Bobes-Bascaran T., Bourgin-Duchesnay J., Bredicean C.A., Bukelskis L., Burkadze A., Abud I.I.C., Castilla-Puentes R., Cetkovich M., Colon-Rivera H., Corral R., Cortez-Vergara C., Crepin P., De Berardis D., Zamora Delgado S., De Lucena D., De Sousa A., Stefano R.D., Dodd S., Elek L.P., Elissa A., Erdelyi-Hamza B., Erzin G., Etchevers M.J., Falkai P., Farcas A., Fedotov I., Filatova V., Fountoulakis N.K., Frankova I., Franza F., Frias P., Galako T., Garay C.J., Garcia-Alvarez L., Garcia-Portilla M.P., Gonda X., Gondek T.M., Gonzalez D.M., Gould H., Grandinetti P., Grau A., Groudeva V., Hagin M., Harada T., Hasan T.M., Hashim N.A., Hilbig J., Hossain S., Iakimova R., Ibrahim M., Iftene F., Ignatenko Y., Irarrazaval M., Ismail Z., Ismayilova J., Jacobs A., Jakovljevic M., Jaksic N., Javed A., Kafali H.Y., Karia S., Kazakova O., Khalifa D., Khaustova O., Koh S., Kopishinskaia S., Kosenko K., Koupidis S.A., Kovacs I., Kulig B., Lalljee A., Liewig J., Majid A., Malashonkova E., Malik K., Malik N.I., Mammadzada G., Mandalia B., Marazziti D., Marcinko D., Martinez S., Matiekus E., Mejia G., Memon R.S., Martinez X.E.M., Mickeviciute D., Milev R., Mohammed M., Molina-Lopez A., Morozov P., Muhammad N.S., Mustac F., Naor M.S., Nassieb A., Navickas A., Okasha T., Pandova M., Panfil A.L., Panteleeva L., Papava I., Patsali M.E., Pavlichenko A., Pejuskovic B., Pinto Da Costa M., Popkov M., Popovic D., Raduan N.J.N., Ramirez F.V., Rancans E., Razali S., Rebok F., Rewekant A., Flores E.N.R., Rivera-Encinas M.T., Saiz P., de Carmona M.S., Martinez D.S., Saw J.A., Saygili G., Schneidereit P., Shah B., Shirasaka T., Silagadze K., Sitanggang S., Skugarevsky O., Spikina A., Mahalingappa S.S., Stoyanova M., Szczegielniak A., Tamasan S.C., Tavormina G., Tavormina M.G.M., Theodorakis P.N., Tohen M., Tsapakis E.M., Tukhvatullina D., Ullah I., Vaidya R., Vega-Dienstmaier J.M., Vrublevska J., Vukovic O., Vysotska O., Widiasih N., Yashikhina A., Prezerakos P.E., Smirnova D. Results of the COVID-19 mental health international for the general population (COMET-G) study. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;54:21–40. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis K.N., Pantoula E., Siamouli M., Moutou K., Gonda X., Rihmer Z., Iacovides A., Akiskal H. Development of the risk assessment suicidality scale (RASS): a population-based study. J. Affect. Disord. 2012;138:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullana M.A., Hidalgo-Mazzei D., Vieta E., Radua J. Coping behaviors associated with decreased anxiety and depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown. J. Affect. Disord. 2020;275:80–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fullana M.A., Littarelli S.A. Covid-19, anxiety, and anxiety-related disorders. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;51:87–89. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonda X., Tarazi F.I. Well-being, resilience and post-traumatic growth in the era of Covid-19 pandemic. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.08.266. S0924-0977X(0921)00742-00742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamama-Raz Y., Goodwin R., Leshem E., Ben-Ezra M. The toll of a second lockdown: a longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021;294:60–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.06.080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L., Wei D., Yang F., Zhang J., Cheng W., Feng J., Yang W., Zhuang K., Chen Q., Ren Z., Li Y., Wang X., Mao Y., Chen Z., Liao M., Cui H., Li C., He Q., Lei X., Feng T., Chen H., Xie P., Rolls E.T., Su L., Li L., Qiu J. Functional connectome prediction of anxiety related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2021;178:530–540. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20070979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques-Avino C., Lopez-Jimenez T., Medina-Perucha L., de Bont J., Berenguera A. Social conditions and mental health during COVID-19 lockdown among people who do not identify with the man/woman binomial in Spain. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacques-Avino C., Lopez-Jimenez T., Medina-Perucha L., de Bont J., Goncalves A.Q., Duarte-Salles T., Berenguera A. Gender-based approach on the social impact and mental health in Spain during COVID-19 lockdown: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-044617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakaje A., Fadel A., Makki L., Ghareeb A., Al Zohbi R. Mental distress and psychological disorders related to COVID-19 mandatory lockdown. Front Public Health. 2021;9 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.585235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaparounaki C.K., Patsali M.E., Mousa D.V., Papadopoulou E.V.K., Papadopoulou K.K.K., Fountoulakis K.N. University students' mental health amidst the COVID-19 quarantine in Greece. Psych. Res. 2020;290 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlafti E., Benioudakis E.S., Barouxi E., Kaiafa G., Didangelos T., Fountoulakis K.N., Pagoni S., Savopoulos C. Exhaustion and burnout in the healthcare system in Greece: a cross-sectional study among internists during the COVID-19 lockdown. Psychiatriki. 2022;33:21–30. doi: 10.22365/jpsych.2022.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khubchandani J., Sharma S., Webb F.J., Wiblishauser M.J., Bowman S.L. Post-lockdown depression and anxiety in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Public Health (Oxf) 2021;43:246–253. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D.S., Cloonan S.A., Taylor E.C., Allbright M.C., Dailey N.S. Trends in suicidal ideation over the first three months of COVID-19 lockdowns. Psych. Res. 2020;293 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore W.D.S., Cloonan S.A., Taylor E.C., Dailey N.S. Mental health during the first weeks of the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Front Psych. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.561898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopilas V., Hasratian A.M., Martinelli L., Ivkic G., Brajkovic L., Gajovic S. Self-perceived mental health status, digital activity, and physical distancing in the context of lockdown versus not-in-lockdown measures in Italy and Croatia: cross-Sectional study in the early ascending phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in march 2020. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopishinskaia S., Cumming P., Karpukhina S., Velichko I., Raskulova G., Zheksembaeva N., Tlemisova D., Morozov P., Fountoulakis K.N., Smirnova D. Association between COVID-19 and catatonia manifestation in two adolescents in Central Asia: incidental findings or cause for alarm? Asian J. Psychiat. 2021;63 doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulig B., Erdelyi-Hamza B., Elek L.P., Kovacs I., Smirnova D., Fountoulakis K., Gonda X. [Effects of COVID-19 on psychological well-being, lifestyle and attitudes towards the origins of the pandemic in psychiatric patients and mentally healthy subjects: fi rst Hungarian descriptive results from a large international online study] Neuropsychopharmacol. Hung. 2020;22:154–165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landi G., Pakenham K.I., Boccolini G., Grandi S., Tossani E. Health anxiety and mental health outcome during COVID-19 lockdown in Italy: the mediating and moderating roles of psychological flexibility. Front Psychol. 2020;11:2195. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mary-Krause M., Herranz Bustamante J.J., Heron M., Andersen A.J., El Aarbaoui T., Melchior M. Impact of COVID-19-like symptoms on occurrence of anxiety/depression during lockdown among the French general population. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0255158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortier P., Vilagut G., Ferrer M., Serra C., Molina J.D., Lopez-Fresnena N., Puig T., Pelayo-Teran J.M., Pijoan J.I., Emparanza J.I., Espuga M., Plana N., Gonzalez-Pinto A., Orti-Lucas R.M., de Salazar A.M., Rius C., Aragones E., Del Cura-Gonzalez I., Aragon-Pena A., Campos M., Parellada M., Perez-Zapata A., Forjaz M.J., Sanz F., Haro J.M., Vieta E., Perez-Sola V., Kessler R.C., Bruffaerts R., Alonso J., Group M.W. Thirty-day suicidal thoughts and behaviors among hospital workers during the first wave of the Spain COVID-19 outbreak. Depress. Anxiety. 2021;38:528–544. doi: 10.1002/da.23129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Msherghi A., Alsuyihili A., Alsoufi A., Ashini A., Alkshik Z., Alshareea E., Idheiraj H., Nagib T., Abusriwel M., Mustafa N., Mohammed F., Eshbeel A., Elbarouni A., Elhadi M. Mental health consequences of lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.605279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey D., Bansal S., Goyal S., Garg A., Sethi N., Pothiyill D.I., Sreelakshmi E.S., Sayyad M.G., Sethi R. Psychological impact of mass quarantine on population during pandemics-The COVID-19 Lock-Down (COLD) study. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0240501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patsali M.E., Mousa D.V., Papadopoulou E.V.K., Papadopoulou K.K.K., Kaparounaki C.K., Diakogiannis I., Fountoulakis K.N. University students' changes in mental health status and determinants of behavior during the COVID-19 lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieh C., Budimir S., Probst T. The effect of age, gender, income, work, and physical activity on mental health during coronavirus disease (COVID-19) lockdown in Austria. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020;136 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinedo R., Vicario-Molina I., Gonzalez Ortega E., Palacios Picos A. Factors related to mental health during the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.715792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M. Can we expect a rise in suicide rates after the Covid-19 pandemic outbreak? Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;52:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prati G., Mancini A.D. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns: a review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies and natural experiments. Psychol. Med. 2021;51:201–211. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine N., Hetherington E., McArthur B.A., McDonald S., Edwards S., Tough S., Madigan S. Maternal depressive and anxiety symptoms before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: a longitudinal analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:405–415. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramiz L., Contrand B., Rojas Castro M.Y., Dupuy M., Lu L., Sztal-Kutas C., Lagarde E. A longitudinal study of mental health before and during COVID-19 lockdown in the French population. Global Health. 2021;17:29. doi: 10.1186/s12992-021-00682-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recchi E., Ferragina E., Helmeid E., Pauly S., Safi M., Sauger N., Schradie J. The "Eye of the Hurricane" Paradox: an unexpected and unequal rise of well-being during the Covid-19 lockdown in France. Res. Soc. Stratif Mobil. 2020;68 doi: 10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Huang W., Pan H., Huang T., Wang X., Ma Y. Mental health during the Covid-19 outbreak in China: a meta-analysis. Psychiatr. Q. 2020;91:1033–1045. doi: 10.1007/s11126-020-09796-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R., Jannini T.B., Socci V., Pacitti F., Lorenzo G.D. Stressful life events and resilience during the COVID-19 lockdown measures in Italy: association with mental health outcomes and age. Front Psych. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.635832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi R., Socci V., Talevi D., Mensi S., Niolu C., Pacitti F., Di Marco A., Rossi A., Siracusano A., Di Lorenzo G. COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown measures impact on mental health among the general population in Italy. Front Psych. 2020;11:790. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladino V., Algeri D., Auriemma V. The psychological and social impact of Covid-19: new perspectives of well-being. Front Psychol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salari N., Hosseinian-Far A., Jalali R., Vaisi-Raygani A., Rasoulpoor S., Mohammadi M., Rasoulpoor S., Khaledi-Paveh B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health. 2020;16:57. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sani G., Janiri D., Di Nicola M., Janiri L., Ferretti S., Chieffo D. Mental health during and after the COVID-19 emergency in Italy. Psych. Clin. Neurosci. 2020;74:372. doi: 10.1111/pcn.13004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shevlin M., Butter S., McBride O., Murphy J., Gibson-Miller J., Hartman T.K., Levita L., Mason L., Martinez A.P., McKay R., Stocks T.V.A., Bennett K., Hyland P., Bentall R.P. Refuting the myth of a 'tsunami' of mental ill-health in populations affected by COVID-19: evidence that response to the pandemic is heterogeneous, not homogeneous. Psychol. Med. 2021:1–9. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721001665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J., Helter T.M., White R.G., van der Boor C., Laszewska A. Impacts of the Covid-19 lockdown and relevant vulnerabilities on capability well-being, mental health and social support: an austrian survey study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:314. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10351-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smirnova D., Syunyakov T., Pavlichenko A., Bragin D., Fedotov I., Filatova V., Ignatenko Y., Kuvshinova N., Prokopenko E., Romanov D., Spikina A., Yashikhina A., Morozov P., Fountoulakis K.N. Interactions between anxiety levels and life habits changes in general population during the pandemic lockdown: decreased physical activity, falling asleep late and internet browsing about COVID-19 are risk factors for anxiety, whereas social media use is not. Psychiatr. Danub. 2021;33:119–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger C.D. Mind Garden; Redwood City California: 2005. State-Trait Anxiety Inventory For Adults. [Google Scholar]

- Surina S., Martinsone K., Perepjolkina V., Kolesnikova J., Vainik U., Ruza A., Vrublevska J., Smirnova D., Fountoulakis K.N., Rancans E. Factors related to COVID-19 preventive behaviors: a structural equation model. Front Psychol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.676521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taquet M., Geddes J.R., Husain M., Luciano S., Harrison P.J. 6-month neurological and psychiatric outcomes in 236 379 survivors of COVID-19: a retrospective cohort study using electronic health records. Lancet Psych. 2021;8:416–427. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00084-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]