Abstract

We identified trace metabolites produced during the anaerobic biodegradation of H26- and D26-n-dodecane by an enrichment culture that mineralizes these compounds in a sulfate-dependent fashion. The metabolites are dodecylsuccinic acids that, in the case of the perdeuterated substrate, retain all of the deuterium atoms. The deuterium retention and the gas chromatography-mass spectrometry fragmentation patterns of the derivatized metabolites suggest that they are formed by C—H or C—D addition across the double bond of fumarate. As trimethylsilyl esters, two nearly coeluting metabolites of equal abundance with nearly identical mass spectra were detected from each of H26- and D26-dodecane, but as methyl esters, only a single metabolite peak was detected for each parent substrate. An authentic standard of protonated n-dodecylsuccinic acid that was synthesized and derivatized by the two methods had the same fragmentation patterns as the metabolites of H26-dodecane. However, the standard gave only a single peak for each ester type and gas chromatographic retention times different from those of the derivatized metabolites. This suggests that the succinyl moiety in the dodecylsuccinic acid metabolites is attached not at the terminal methyl group of the alkane but at a subterminal position. The detection of two equally abundant trimethylsilyl-esterified metabolites in culture extracts suggests that the analysis is resolving diastereomers which have the succinyl moiety located at the same subterminal carbon in two different absolute configurations. Alternatively, there may be more than one methylene group in the alkane that undergoes the proposed fumarate addition reaction, giving at least two structural isomers in equal amounts.

The anaerobic biodegradation of n-alkanes has recently been demonstrated under nitrate-reducing (6, 11, 19), sulfate-reducing (1, 2, 7, 9, 20–22), and methanogenic (3, 25) conditions. Pure bacterial cultures that couple the reduction of the first two electron acceptors to the oxidation of alkanes have been isolated (1, 2, 11, 20–22), but little is known about the initial mechanism(s) of anaerobic activation and subsequent metabolism of these hydrocarbons. Previous studies of the total cellular fatty acid composition of pure sulfate-reducing cultures grown on alkanes have suggested that activation does not occur via dehydrogenation to the corresponding 1-alkene (2) but does occur by addition of an unknown organic carbon fragment to the C-2 position of the original molecule (22).

Recent research has shown that the anaerobic bacterial metabolism of toluene and xylenes is initiated by addition of the methyl group to the double bond of fumarate, forming optically pure (R)-(+)-benzylsuccinic acid and methylbenzylsuccinic acids, respectively (4, 5, 12–14). These addition reactions occur with retention of the proton abstracted from the methyl group in the succinyl moiety of the metabolite (4, 5). The detection of 3-phenyl-1,2-butanedicarboxylic acid from ethylbenzene (L. M. Gieg and J. M. Suflita, Abstr. 99th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol., abstr. Q-109, p. 554, 1999) may result from an analogous fumarate addition reaction of the methylene group. Alternatively, and as was suggested for toluene, this metabolite may be formed by successive additions of two carbon units from acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), a mechanism that would result in the loss of two H atoms (8). Partially purified benzylsuccinate synthase from the denitrifying Azoarcus sp. strain T was shown to catalyze addition to fumarate by the methyl groups of toluene and all three isomers of xylene, as well as of 1-methyl-1-cyclohexene but not of 4-methyl-1-cyclohexene or methylcyclohexane (5). The nonreactivity of the latter two substrates led the researchers to conclude that the resonance stabilization offered to the radical transition state in the form of a conjugated π system by the adjacent aromatic ring or conjugated double bond was necessary for this bioconversion (5). The dodecylsuccinic acid metabolites observed in the present study are formed with retention of the deuterium from D26-dodecane on the succinyl moiety, suggesting that the bond between the dodecane and succinate was formed by addition across the double bond of fumarate. This is a novel bioconversion for alkanes; the nature of the enzymes that catalyze this conversion, as well as how it occurs without resonance stabilization offered by a conjugated π system, remains to be clarified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth of enrichment cultures.

Enrichment cultures were grown in a sulfate-containing brackish mineral medium (24) that was amended with resazurin (1 mg/liter) as a redox indicator and cysteine hydrochloride and Na2S · 9H2O (50 mg/liter each) as reductants. All culture bottles were sealed with Teflon-lined serum stoppers and incubated at 32°C in an inverted position. Uninoculated sterile controls remained reduced throughout the incubation period. Initially, 50 ml of this medium was inoculated with 10 ml of an oily sludge collected from a naval wastewater storage facility as previously described (15). This was incubated under an N2:CO2 (4:1) atmosphere with 1 ml of an alkane mixture containing decane, dodecane, hexadecane, and octadecane (1:1:1:1.5, vol/vol). The alkane mixture, and later pure liquid alkane feedstocks, was flushed with N2, sealed under Teflon-lined stoppers, and autoclaved before use. In the enrichment cultures, sulfide production was monitored colorimetrically (23) and sulfate reduction was measured by ion chromatography (7). Due to the abundance of labile substrates in the inoculum, it was not until the third 25% transfer that an enhancement of sulfide production and sulfate reduction were measured in triplicate alkane-amended cultures relative to the substrate-unamended controls (data not shown). After the fifth transfer, individual alkanes were provided to the culture. The dodecane-amended incubation grew best and therefore was selected for further study. The culture has since been repeatedly transferred for over 2 years (bimonthly; 25%, vol/vol) in 35 ml of medium given 50 μl of dodecane (>99%; Aldrich, Milwaukee, Wis.) as the sole carbon source. This is well above the aqueous solubility of dodecane (3.4 μg/liter) (10), so throughout this report the amount of dodecane given to the cultures is presented as an absolute value rather than as an aqueous concentration.

[1-14C]dodecane mineralization.

Cultures were incubated with 25 μl of unlabeled dodecane and 0.82 μCi of [1-14C]dodecane (≥98%; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). After 9 weeks of incubation, the cultures were acidified with 2 ml of H2SO4 (9 M) and 14CO2 was recovered and quantified in a trapping train designed for this purpose (17). After flushing of the cultures, 10 ml of pentane was used to extract the remaining dodecane and [1-14C]dodecane, and the residual radioactivity was determined by analyzing a 0.5-ml portion of the extract in a liquid scintillation counter.

Dodecane loss measurements.

The loss of dodecane (25 μl) in cultures relative to sterile controls was quantified by acidifying the medium with 0.2 ml of HCl (6 M), giving 10 μl of n-tetradecane as the internal standard and extracting three times with dichloromethane (15 ml). The extracts were pooled, dried over Na2SO4, concentrated on a rotary evaporator to 2-ml volumes, and analyzed with a Hewlett-Packard 6890 GC by using an HP-5 column (length, 30 m; inside diameter, 0.32 mm; film thickness, 0.25 μm) and a flame ionization detector. The injector and detector temperatures were 200 and 250°C, respectively, and the oven was held at 90°C for 2 min before its temperature was increased by 4°C/min to 200°C. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 2 ml/min.

Metabolites of H26- and D26-dodecane.

Cultures were inoculated with a H26-dodecane-grown culture and incubated with 25 μl of either H26- or D26-dodecane (>98%; Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Andover, Mass.) or a mixture of 12 μl of each, for periods ranging from 4 to 8 weeks. Cultures were then acidified with 2 ml of HCl (6 M) and extracted twice with 20-ml volumes of ethyl acetate. During earlier extractions, cultures were given 0.75 ml of NaOH (6 M) before acidification and left for 30 min to hydrolyze prospective CoA thioesters. However, this base treatment was not necessary to recover the metabolites. The pooled extracts were dried over Na2SO4 before concentration on a rotary evaporator and subsequently under a flow of N2, to 0.1 ml. The extracts were then given 0.1 ml of N,O-bis(trimethylsilyl)trifluoroacetimide (BSTFA; Pierce, Rockford, Ill.) and heated at 65°C for 10 min before analysis by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS). To help clarify the nature of the metabolites, extracts were also derivatized with 1 ml of an ethereal solution of diazomethane. GC-MS analyses used a DB-5 column (length, 30 m; inside diameter, 0.25 mm; film thickness, 0.1 μm), in a Hewlett-Packard 5890 GC with a 5970 mass-selective detector. The injector and detector temperatures were both 250°C, and the temperature program for the oven was the same as that given above, except that the final temperature was 240°C. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 0.8 ml/min. Chemical ionization GC-MS with ammonia as the reagent gas was conducted at the University of Alberta (Mass Spectrometry Laboratory, Department of Chemistry). Tandem GC-MS (GC-MS-MS) analyses were conducted at the University of Oklahoma (Analytical Services Laboratory, Department of Chemistry). An authentic standard of n-dodecylsuccinic acid was prepared by base hydrolysis of n-dodecylsuccinic anhydride (TCI America, Portland, Oreg.). The anhydride (50 mg) was suspended in 100 ml of NaOH (3 M) and 10 ml of methanol and heated at 65°C. After 2 h, the remaining crystals of undissolved anhydride were removed by filtration, and the filtrate was acidified to a pH of <2 with HCl and extracted twice with 20-ml portions of ethyl acetate. The pooled extracts were dried over sodium sulfate, concentrated, and derivatized.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

[1-14C]dodecane mineralization.

In enrichment cultures, 54% of the added radioactivity was recovered as 14CO2 and 25% as unoxidized dodecane in a pentane extract (79% total recovery) (Table 1). When sulfate was excluded from the medium, except for a small amount transferred with the inoculum, only 6% mineralization was observed and 78% of the added [1-14C]dodecane was recovered unaltered in the pentane extract (84% total recovery) (Table 1). According to equation 1, this 6% mineralization would theoretically require 1.75 mM sulfate. The sulfate transferred with the inoculum resulted in an initial concentration of 2.5 mM sulfate in the sulfate-free medium, and during the 9-week incubation this was reduced to 0.5 mM. Thus, the low amount of sulfate transferred with the inoculum accounts for the 6% mineralization observed in the sulfate-free medium. With incubations that contained sulfate and equimolar amounts of sodium molybdate (30 mM), an inhibitor of sulfate reduction, there was no 14CO2 produced (Table 1). Thus, dodecane mineralization was dependent on sulfate reduction. In uninoculated sterile controls, the total recovery of [1-14C]dodecane was 88% and there was no 14CO2 produced (Table 1). The remaining 12 to 21% radioactivity that was not accounted for in the sterile control and cultures, respectively, was likely lost due to sorption to the incubation flask closures. In nonsterile incubations, the unrecovered radioactivity may also be partly due to the presence of 14C-labeled metabolites or 14C incorporation into cell material, which did not partition to the pentane extract. Collectively, these experiments argue that anaerobic mineralization of dodecane by the enrichment was coupled to the reduction of sulfate.

TABLE 1.

Sulfate-dependent, molybdate-inhibited mineralization of [1-14C]dodecane (0.8 μCi) by the enrichment culture in the presence of 25 μl of dodecane

| Condition | % Recovery as:

|

Total recovery (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 14CO2 | [1-14C]dodecane | ||

| Active culture | 54 | 25 | 79 |

| Sulfate-free medium | 6 | 78 | 84 |

| Molybdate amendment | 0 | NDa | ND |

| Sterile control | 0 | 88 | 88 |

ND, not determined.

Stoichiometry of dodecane oxidation coupled to sulfate reduction.

The depletion of dodecane in the cultures relative to sterile controls extracted both at the start of the experiment and at the end was determined by the decrease in the ratio of the peak area of the dodecane to the tetradecane internal standard. In these experiments, 8% abiotic loss of dodecane was observed in the sterile controls over an 11-week incubation. An additional 70 to 73% degradation of dodecane was observed in triplicate nonsterile incubations. The amount of sulfate reduction theoretically expected, assuming complete dodecane mineralization, was determined according to equation 1:

|

1 |

|

After correction for sulfate reduction in controls lacking dodecane, the amount of sulfate reduction measured in the cultures was 94% ± 5% of the theoretically expected amount.

Dodecane degradation in bicarbonate-free medium.

In another experiment, cells of the dodecane-degrading enrichment were washed and incubated in bicarbonate-free medium under an N2 headspace. The medium was buffered with HEPES (25 mM, pH 7.5). Four replicate cell suspensions were incubated with dodecane, two of which were amended with bicarbonate (2 g/liter). After 7 weeks of incubation, analyses indicated that the extent of dodecane degradation and sulfate reduction was equal in all the cultures (data not shown). Thus, anaerobic alkane biodegradation by these cells was not bicarbonate dependent. This suggests that the mechanism for alkane metabolism was unlikely to involve carboxylation and is consistent with previous observations for strain AK-01 (22).

TMS-esterified metabolites of H26- and D26-dodecane.

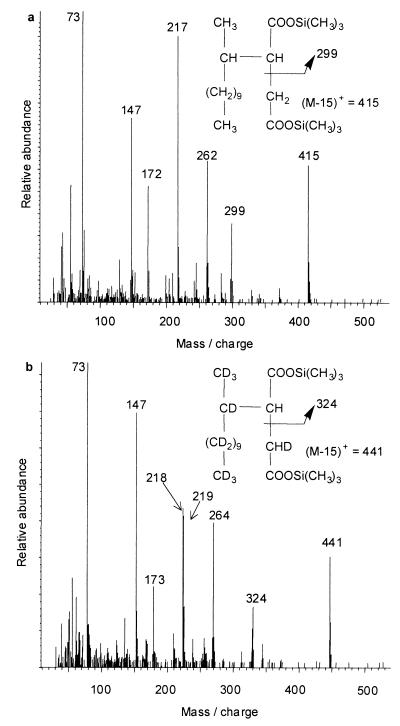

When ethyl acetate extracts of acidified cultures grown on H26-dodecane were derivatized to form trimethylsilyl (TMS) esters and analyzed by GC-MS, two equally abundant trace metabolites eluted at 30.0 and 30.2 min. They gave nearly identical mass spectra, so only one is shown in Fig. 1a. Similarly, when cultures were grown on D26-dodecane, two metabolites with nearly identical mass spectra eluted at 29.6 and 29.8 min, so a single example is shown in Fig. 1b. All four metabolites were detected in cultures amended with a mixture of H26- and D26-dodecane, while none were detected in sterile controls. All four metabolites showed abundant ions at m/z 73, which is due to the TMS group in these BSTFA-derivatized metabolites, and m/z 147, which is the (CH3)2Si⩵OSi(CH3)3 ion (Fig. 1). This latter ion indicates that the metabolites are di-TMS-derivatized compounds containing two BSTFA-reactive functional groups (18). These two ions are also the most abundant ions in the mass spectrum of an authentic standard of BSTFA-derivatized succinic acid (data not shown).

FIG. 1.

The mass spectra of both dodecylsuccinic acid metabolites of H26-dodecane (a) and D26-dodecane (b) analyzed as TMS esters.

The prominent ion with the largest mass in the spectra of these metabolites occurs at m/z 415 with H26-dodecane (Fig. 1a) and m/z 441 with D26-dodecane (Fig. 1b). The latter ion is 26 atomic mass units (AMU) larger than the former, accounting for all 26 of the deuterium atoms present in the labeled parent substrate. However, these masses are not the molecular ions (M+) of the four metabolites but rather the (M-15)+ ions resulting from loss of a CH3 group from one of the TMS substituents. This (M-15)+ ion is typical of TMS esters (18) and is also observed in the mass spectrum of an authentic standard of BSTFA-derivatized succinic acid (data not shown). The M+ ion of the authentic standard of the di-TMS ester of succinic acid was just barely detectable, consistent with the instability of the M+ ion of the metabolites from H26- and D26-dodecane. The molecular weights of the derivatized metabolites were verified as 430 and 456, respectively, by chemical ionization GC-MS with ammonia as the reagent gas. This method gave quasimolecular ions of (M+1)+ and (M+18)+, corresponding to (M+H)+ and (M+NH4)+, respectively, at m/z 431 and 448 for the protonated metabolites and m/z 457 and 474 for the deuterated metabolites (data not shown). These molecular weights are consistent with the proposed dodecylsuccinic acid structures shown in Fig. 1 as the fumarate addition products of H26- and D26-dodecane. This assumes that in both cases the fumarate molecules involved in the proposed alkane addition reaction were protonated and not deuterated. This would be expected even during growth on D26-dodecane, since any deuterium atoms entering the tricarboxylic acid cycle in the form of partially deuterated acetyl-CoA from D26-dodecane would be exchanged, giving protonated fumarate as a central metabolic intermediate. Only 1 out of 3 protons on the methyl group of acetyl-CoA would likely be a deuterium, presuming a classical β-oxidation of a fully deuterated fatty acid. Upon entry into the tricarboxylic acid cycle, there is only a 1-in-6 chance that this single deuterium would be retained in a molecule of fumarate. Thus, it is highly likely that any deuterium atoms present in fumarate would be present in such low amounts that they would not be detected above the natural abundance of 13C (1.1% per carbon atom in each metabolite fragment ion). Furthermore, the GC-MS uses a high scan rate, so it does not give reliable isotope abundance measurements for the relatively weak natural isotope ions, effectively obscuring any small contribution from deuterated fumarate.

The abundant ion with the next largest mass in the spectra of the metabolites from H26-dodecane (m/z 299) (Fig. 1a) was only 25 AMU less than the corresponding fragment in the D26-dodecane metabolite spectra (m/z 324) (Fig. 1b). These ions result from simple cleavage between the methylene and methine carbons in the middle of the succinic acid moiety of the dodecylsuccinic acid metabolites (Fig. 1). The 25-AMU difference occurs because one of the deuterium atoms from the deuterated parent substrate was transferred to the methylene carbon of the succinic acid moiety of the metabolites and hence is not included in the fragments that give these ions.

The metabolites from H26-dodecane underwent a McLafferty rearrangement (16) during GC-MS analysis to give the ion at m/z 262 (Fig. 1a). This rearrangement basically involves cleavage of the bond between the dodecyl and succinic acid portions of the metabolites, with transfer of a single proton from the dodecyl portion onto the nearest carbonyl group in the succinic acid portion. The resulting ion at m/z 262 has the same chemical composition as the di-TMS ester of succinic acid. The corresponding ion at m/z 264 from the D26-dodecane metabolites (Fig. 1b) is larger by 2 AMU because it contains one deuterium on the methylene group from the proposed bacterial addition across the double bond of fumarate and one deuterium on the nearest carbonyl group from the McLafferty rearrangement, which occurs during the GC-MS analysis. These McLafferty rearrangement ions lose HOSi(CH3)3 (90 AMU) or DOSi(CH3)3 (91 AMU) to give the resulting ions at m/z 172 and 173, respectively (Fig. 1). Analysis by GC-MS-MS confirmed that these ions result from further fragmentation of the McLafferty rearrangement ions. The ion at m/z 217 in the mass spectra of the metabolites from H26-dodecane (Fig. 1a) is 45 AMU (CO2H) smaller than the McLafferty rearrangement ion. Likewise, the equally abundant ions at m/z 218 and 219 in the spectra of the deuterated metabolites (Fig. 1b) are 45 AMU (CO2H) and 46 AMU (CO2D) smaller than the deuterated McLafferty rearrangement ion at m/z 264. Analysis by GC-MS-MS did not confirm that these ions actually resulted from further fragmentations of the McLafferty rearrangement ions and hence, the mechanism of their formation cannot be confirmed. The mechanism likely involves a long-range migration of a TMS group as has been observed previously (16). Even though the mechanism of formation of these ions is not known, the ion at m/z 217 was also observed in the mass spectrum of an authentic standard of TMS-derivatized protonated n-dodecylsuccinic acid (below).

Methyl-esterified metabolites of H26- and D26-dodecane.

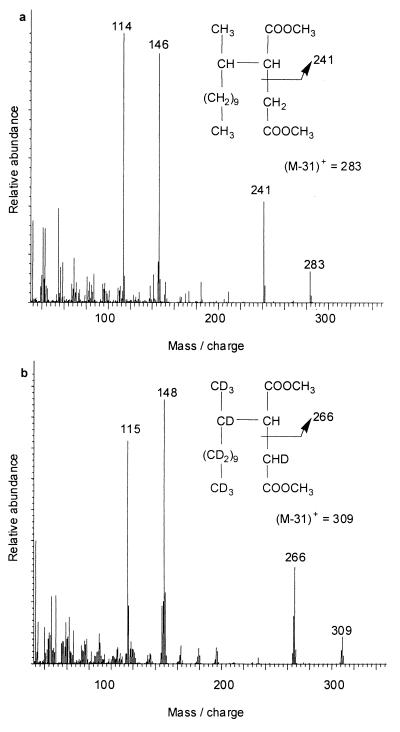

When extracts of cultures grown on H26-dodecane were methyl esterified by treatment with diazomethane and analyzed by GC-MS, a single metabolite peak eluted at a retention time of 26.2 min that gave the mass spectrum shown in Fig. 2a. Similarly, cultures grown on D26-dodecane gave one metabolite peak at a retention time of 25.8 min with the mass spectrum shown in Fig. 2b. Neither of these metabolites were detected in the corresponding sterile controls. The ion with the largest mass in the spectra of these metabolites occurs at m/z 283 with H26-dodecane (Fig. 2a) and m/z 309 with D26-dodecane (Fig. 2b). The latter ion is larger by 26 AMU than the former, accounting for all 26 of the deuterium atoms in the labeled parent substrate. However, these ions are not the M+ ions of the metabolites but rather the (M-31)+ ions that result from the loss of a methoxy group from the methyl-esterified succinyl moiety. This fragmentation pattern is typical of methyl esters (16) and gives the base peak in the mass spectrum of an authentic standard of methyl-esterified succinic acid for which the M+ ion was also not detected (data not shown). The molecular weights of these metabolites were verified as 314 and 340, respectively, by chemical ionization GC-MS with ammonia as the reagent gas. These analyses gave quasimolecular ions of (M+1)+ and (M+18)+, corresponding to (M+H)+ and (M+NH4)+, respectively, at m/z 315 and 332 for the protonated metabolite and m/z 341 and 358 for the deuterated metabolite (data not shown). These molecular weights are consistent with the proposed dodecylsuccinic acid structures shown in Fig. 2 as the fumarate addition products of H26- and D26-dodecane. As discussed above, this assumes that the fumarate molecules were not significantly deuterated, even in cultures grown on D26-dodecane.

FIG. 2.

The mass spectra of dodecylsuccinic acid metabolites of H26-dodecane (a) and D26-dodecane (b) analyzed as methyl esters.

The abundant ion with the next largest mass in the spectrum of the metabolite from H26-dodecane (m/z 241) (Fig. 2a) was smaller by only 25 AMU than the corresponding fragment in the spectrum of the deuterated metabolite (m/z 266) (Fig. 2b). These ions result from simple cleavage between the methylene and methine carbons in the middle of the succinic acid moiety of the metabolites; hence, the deuterium on the methylene carbon which we propose was retained in the succinyl moiety during addition across the double bond of fumarate is excluded from the fragment that gives these ions.

The metabolites from H26- and D26-dodecane both underwent a McLafferty rearrangement (16) during GC-MS analysis to give the ions at m/z 146 (Fig. 2a) and m/z 148 (Fig. 2b). The mechanism of this rearrangement and the reason why the ion from the deuterated metabolite is larger by 2 AMU are the same as described above for the McLafferty rearrangement of the TMS esters. However, the ions now have different m/z values because the molecules now bear two methyl groups instead of two TMS substituents. Analysis by GC-MS-MS confirmed that these McLafferty rearrangement ions at m/z 146 and 148 undergo further fragmentation, namely, loss of HOCH3 (32 AMU) and DOCH3 (33 AMU), to give the ions at m/z 114 (Fig. 2a) and m/z 115 (Fig. 2b), respectively.

Authentic standard of n-dodecylsuccinic acid.

A synthesized authentic standard of protonated n-dodecylsuccinic acid eluted from the GC-MS as a single sharp peak at a retention time of 31.5 min when it was analyzed as a TMS ester. The mass spectrum of the derivatized standard (data not shown) showed the same fragmentation pattern as the metabolites from H26-dodecane (Fig. 1a). However, the retention time of the standard was just over 1 min longer than that for the TMS-derivatized metabolites and only gave a single chromatographic peak, whereas the culture extract had two equally abundant, nearly coeluting metabolites. This confirms that the succinyl moiety in the metabolites cannot be attached to the terminal carbon atom in the dodecyl moiety. The structures depicted in Fig. 1 assume a subterminal attachment point at position 2 of the alkane, based on results of previous research (22). The detection of two equally abundant TMS-esterified metabolites suggests that the GC analysis is resolving two diastereomers which have the succinyl moiety located at the same subterminal carbon atom in at least two different absolute configurations. Any subterminal location of the succinyl moiety would give a metabolite that has two chiral carbon atoms. The two methine carbons, which form the bond between the dodecyl and succinyl moieties, would each be chiral and could each exist in either the R or the S configuration. Thus, there exist two possible pairs of enantiomers which have a diasteromeric relationship to each other. While enantiomers differ only in the ability to rotate the plane of polarized light, diastereomers can have different physical properties, which might allow their resolution by GC-MS analysis. Previous studies with benzylsuccinate synthase using toluene and xylenes have yielded the metabolites benzylsuccinic and methylbenzylsuccinic acids, respectively, which have only one chiral carbon atom each—the methine carbon in the succinyl moiety (5). Thus, there is no possibility for these metabolites to exist as diastereomers. Benzylsuccinate synthase has been shown to form exclusively the (R)-(+)-enantiomer from toluene (14). If a similar enzyme specificity exists for the chiral methine carbon in the succinyl moiety of the dodecylsuccinic acid metabolites observed in this study, the other chiral methine carbon in the dodecyl moiety could conceivably still exist in either the R or the S configuration, giving two possible diasteromers (R,R- and R,S- referring to the methine carbons in the succinyl and dodecyl moieties, respectively). The authentic standard of n-dodecylsuccinic acid bears the succinic acid moiety on the terminal methylene group of the dodecyl moiety. Thus, because of symmetry in the dodecyl moiety, there is only one chiral carbon atom in the standard—the methine group in the succinyl moiety. With only one chiral carbon atom, there is not a possibility for diastereomers to exist and hence the standard gives only a single peak. Our results do not allow us to conclusively rule out the possibility that duplicate metabolite peaks exist as TMS esters, because there may be more than one methylene group in the alkane that undergoes the proposed fumarate addition reaction, giving at least two structural isomers. However, the fact that the two TMS-derivatized metabolites were always observed in equal abundance from each of H26- and D26-dodecane lends support to the stereochemistry argument.

When analyzed as a methyl ester, the authentic standard of n-dodecylsuccinic acid eluted from the GC-MS as a single sharp peak at a retention time of 27.4 min, which is more than a minute later than the time for the methyl-esterified metabolite from H26-dodecane. However, the mass spectrum (data not shown) showed the same fragmentation patterns seen in the derivatized metabolite (Fig. 2a). This supports the identification of the metabolite as an isomer of dodecylsuccinic acid that bears the succinyl moiety at a subterminal location. The structures shown in Fig. 2 also indicate that this is position 2 of the alkane, based on previous work (22). The fact that only a single metabolite peak was detected when culture extracts were methyl esterified is likely the result of the inability of the GC-MS analysis to resolve the resulting diastereomers when derivatized in this fashion.

The fragmentation patterns observed in the mass spectra of the derivatized metabolites detected from H26- and D26-dodecane support the conclusion that these compounds are dodecylsuccinic acids which may result from C—H or C—D addition across the double bond of fumarate. The presence of all 26 deuterium atoms in the metabolites from D26-dodecane suggests that this is the initial step in anaerobic activation of these alkanes. Other suggested mechanisms of anaerobic alkane metabolism, such as prior desaturation or hydroxylation of the alkane, would result in the loss of at least one of these atoms. Furthermore, it shows that the dodecylsuccinic acid metabolites are not the result of successive additions of C2 units from acetyl-CoA. This mechanism, previously proposed for toluene metabolism (8), is an alternative to fumarate addition. Such stepwise addition reactions to form metabolites identified herein would be expected to result in the loss of two deuteriums from the labeled alkane. Our results suggest that the addition of dodecane to the double bond of fumarate is at least one mechanism of alkane activation under anaerobic conditions.

Our findings are also consistent with a previous report that early steps in the pathway for alkane metabolism involve carbon addition from a source other than inorganic bicarbonate at the C-2 position of the original molecule, ultimately yielding 2-carboxy-substituted alkanes (22). We hypothesize that the dodecylsuccinic acid metabolites observed in the current study may be further metabolized to 2-carboxy-substituted cellular fatty acids, as observed previously with [1,2-13C2]hexadecane and perdeuterated pentadecane (22). We have not yet conducted analyses of the total cellular fatty acids of our enrichment culture to see if this is indeed the case. The proposed mechanism of initial anaerobic bacterial attack of alkanes is analogous to that reported previously for alkylbenzenes, and preliminary observations in our laboratory have suggested that it also likely occurs with alkylated cycloalkanes (data not shown). As such, fumarate addition reactions may represent a common theme for the anaerobic oxidation of a broad range of hydrocarbon contaminants. Using GC-MS to screen for ions unique to the succinic acid portion of the derivatized metabolites may be a useful technique to garner evidence for the intrinsic anaerobic bioremediation of a broad range of hydrocarbon contaminants.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Office of Naval Research and the Environmental Protection Agency through grants to J.M.S. K.G.K. was partially supported by a Post-Doctoral Fellowship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aeckersberg F, Bak F, Widdel F. Anaerobic oxidation of saturated hydrocarbons to CO2 by a new type of sulfate-reducing bacterium. Arch Microbiol. 1991;156:5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aeckersberg F, Rainey F A, Widdel F. Growth, natural relationships, cellular fatty acids and metabolic adaptation of sulfate-reducing bacteria that utilize long-chain alkanes under anoxic conditions. Arch Microbiol. 1998;170:361–369. doi: 10.1007/s002030050654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anderson R T, Lovley D R. Hexadecane decay by methanogenesis. Nature. 2000;404:722–723. doi: 10.1038/35008145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beller H R, Spormann A M. Anaerobic activation of toluene and o-xylene by addition to fumarate in denitrifying strain T. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:670–676. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.3.670-676.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beller H R, Spormann A M. Substrate range of benzylsuccinate synthase from Azoarcus sp. strain T. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;178:147–153. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13771.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bregnard T P-A, Höhener P, Häner A, Zeyer J. Degradation of weathered diesel fuel by microorganisms from a contaminated aquifer in aerobic and anaerobic microcosms. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1996;15:299–307. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caldwell M E, Garrett R M, Prince R C, Suflita J M. Anaerobic biodegradation of long-chain n-alkanes under sulfate-reducing conditions. Environ Sci Technol. 1998;32:2191–2195. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chee-Sanford J C, Frost J W, Fries M R, Zhou J, Tiedje J M. Evidence for acetyl coenzyme A and cinnamoyl coenzyme A in the anaerobic toluene mineralization pathway in Azoarcus tolulyticus Tol-4. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1996;62:964–973. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.3.964-973.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates J D, Woodward J, Allen J, Philp P, Lovley D R. Anaerobic degradation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and alkanes in petroleum-contaminated marine harbor sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:3589–3593. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.9.3589-3593.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eastcott L, Shiu W Y, Mackay D. Environmentally relevant physical-chemical properties of hydrocarbons: a review of data and development of simple correlations. Oil Chem Pollut. 1988;4:191–216. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehrenreich P, Behrends A, Harder J, Widdel F. Anaerobic oxidation of alkanes by newly isolated denitrifying bacteria. Arch Microbiol. 2000;173:58–64. doi: 10.1007/s002030050008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heider J, Spormann A M, Beller H R, Widdel F. Anaerobic bacterial metabolism of hydrocarbons. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1999;22:459–473. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger C J, Beller H R, Reinhard M, Spormann A M. Initial reactions in anaerobic oxidation of m-xylene by the denitrifying bacterium Azoarcus sp. strain T. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:6403–6410. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.20.6403-6410.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leutwein C, Heider J. Anaerobic toluene-catabolic pathway in denitrifying Thauera aromatica: activation and β-oxidation of the first intermediate, (R)-(+)-benzylsuccinate. Microbiology. 1999;145:3265–3271. doi: 10.1099/00221287-145-11-3265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Londry K L, Suflita J M. Use of nitrate to control sulfide generation by sulfate-reducing bacteria associated with oily waste. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;22:582–589. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLafferty F W. Interpretation of mass spectra. 3rd ed. Mill Valley, Calif: University Science Books; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nuck B A, Federle T W. Batch test for assessing the mineralization of 14C-radiolabeled compounds under realistic anaerobic conditions. Environ Sci Technol. 1996;30:3597–3603. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pierce A E. Silylation of organic compounds. Rockford, Ill: Pierce Chemical Co.; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rabus R, Wilkes H, Schramm A, Harms G, Behrends A, Amann R, Widdel F. Anaerobic utilization of alkylbenzenes and n-alkanes from crude oil in an enrichment culture of denitrifying bacteria affiliating with the β-subclass of Proteobacteria. Environ Microbiol. 1999;1:145–157. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rueter P, Rabus R, Wilkes H, Aeckersberg F, Rainey F A, Jannasch H W, Widdel F. Anaerobic oxidation of hydrocarbons in crude oil by new types of sulphate-reducing bacteria. Nature. 1994;372:455–458. doi: 10.1038/372455a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.So C M, Young L Y. Isolation and characterization of a sulfate-reducing bacterium that anaerobically degrades alkanes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:2969–2976. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.7.2969-2976.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.So C M, Young L Y. Initial reactions in anaerobic alkane degradation by a sulfate reducer, strain AK-01. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1999;65:5532–5540. doi: 10.1128/aem.65.12.5532-5540.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trüper H G, Schlegel H G. Sulphur metabolism in Thiorhodacea. I. Quantitative measurements on growing cells of Chromatium okenii. Antonie Leeuwenhoek. 1964;30:225–238. doi: 10.1007/BF02046728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Widdel F, Bak F. Gram-negative mesophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria. In: Balows A, Trüper H G, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H, editors. The prokaryotes. 2nd ed. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1992. pp. 3352–3378. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zengler K, Richnow H H, Rosselló-Mora R, Michaelis W, Widdel F. Methane formation from long-chain alkanes by anaerobic microorganisms. Nature. 1999;401:266–269. doi: 10.1038/45777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]