Abstract

Background: Skeletally immature patients with coronal plane angular deformity (CPAD) may be at increased risk for intra-articular pathology and patellofemoral instability (PFI). These patients may be candidates for implant-mediated guided growth (IMGG) procedures with tension band plates to address CPAD in addition to procedures for concomitant knee pathology. However, there are limited data on performing these procedures simultaneously. Questions/Purpose: We sought to demonstrate the feasibility of combined procedures to address both knee pathology and concomitant CPAD using IMGG in skeletally immature patients. Methods: We conducted a retrospective review of skeletally immature patients who underwent IMGG and concomitant surgery for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction, osteochondritis dissecans repair, meniscus pathology, or PFI at a single institution by 2 surgeons between 2008 and 2019. Data on demographics, surgical details, follow-up, and complications were recorded. Deformity correction was assessed in a subset of eligible patients. Results: Of 29 patients meeting inclusion criteria, deformity correction was assessed in a subset of 17 patients (15 valgus, 2 varus). At final follow-up, 16 of 17 patients had mechanical tibiofemoral (mTFA) angles of <5° of varus or valgus. One patient developed “rebound” valgus >5° after plate removal. Conclusions: The IMGG performed in the setting of treating intra-articular knee pathology is feasible and should be considered for skeletally immature patients with CPAD undergoing surgery for concomitant knee pathology.

Keywords: growth disturbances/limb length inequalities, medical conditions, arthroscopy, operative treatments, pediatrics, practice specialty, sports, knee, body sites

Introduction

Skeletally immature patients with coronal plane angular deformity (CPAD) may be at increased risk for anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injury, osteochondritis dissecans (OCD), meniscus pathology, and patellar instability in the short term, as well as degenerative disease in the long term [3,6,8,10,16,19,24,27]. Because of this, in skeletally immature patients presenting with the above conditions it is important to obtain standing mechanical alignment radiographs so that a coronal plane deformity is not missed. Although CPAD is an important modifiable risk factor, little published has been on surgical outcomes in this population addressing both the intra-articular knee pathology and concurrent placement of guided growth implants.

Excess valgus stress across the knee may predispose patients to ACL injury [16]. While genu valgum itself has not been statistically identified as a risk factor for ACL injury, it increases dynamic valgus with activities and valgus moment with jumping, both of which are associated with ACL injury [19]. Osteochondritis dissecans affects children, adolescents, and young adults and the etiology remains unknown [12]. However, multiple studies have demonstrated an association between OCD location (medial or lateral femoral condyle) and lower limb mechanical axis deviation (MAD) [6,12,14]. Similarly, varus malalignment has been associated with medial meniscus pathology, and valgus malalignment has been associated with lateral meniscus pathology [8,10]. Patellar instability is also associated with genu valgum [3]. Hemiepiphysiodesis with tension band plating of the distal femur and/or proximal tibia to correct CPAD in skeletally immature patients is a well-described and accepted technique [2,4,25,28]. The age at which treatment should be initiated, rate of expected correction, and estimates of growth remaining have also been described [2,5,7].

There are a lack of published outcomes on concomitant surgery for intra-articular knee pathology and implant-mediated guided growth (IMGG). Given the importance of CPAD as a risk factor for the above knee pathologies and the fact that CPAD can be effectively corrected with IMGG, we sought to measure outcomes in skeletally immature patients after concomitant surgery. Our hypothesis was that concomitant surgery for intra-articular knee pathology and IMGG would be safe and effective.

Methods

A total of 482 IMGG procedures performed between 2008 and 2019 at a single urban tertiary care musculoskeletal institution were retrospectively reviewed. Patients who underwent a concomitant procedure to address patellofemoral instability (PFI), OCD lesions, meniscus pathology, or reconstruction of the ACL and had an available preoperative standing hip-to-ankle radiograph were eligible. Patients with previously attempted IMGG were excluded. In total, 29 patients who underwent concomitant femoral and/or tibial hemiepiphysiodesis and a procedure to address ACL, OCD, meniscus, or patellofemoral pathology were included (Table 1). Demographic data including age and sex, surgical details, date of latest radiographic follow-up, complications, and dates and details of subsequent surgical procedures were collected. In addition, radiographic measurements were performed on a subset of 17 patients with appropriate follow-up to assess deformity correction.

Table 1.

Demographics of included patients.

| Patellar instability surgery | OCD drilling/fixation | Meniscus repair/meniscectomy | ACL reconstruction | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 12.2 | 12.7 | 14.2 | 13.1 | 12.8 ± 1.8 |

| Sex | |||||

| Male | 6 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 17 |

| Female | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 12 |

| Deformity | |||||

| Valgus | 12 | 4 | 4 | 6 | 26 |

| Varus | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Implant location | |||||

| Distal Femur | 11 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 24 |

| Distal Femur + Proximal Tibia | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Laterality | |||||

| Right | 8 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 18 |

| Left | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 11 |

| Fixation | |||||

| Hinge Plate | 9 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 21 |

| Orthopediatrics Plate | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Peanut Plate | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

OCD osteochondritis dissecans, ACL anterior cruciate ligament.

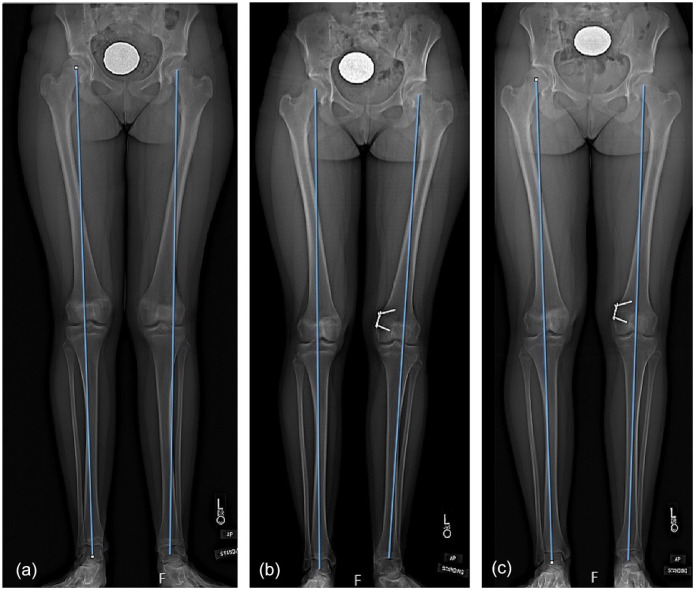

Hemiepiphysiodesis was performed using a tension band plate. Assessment of deformity correction was performed in 17 patients (15 valgus and 2 varus). Twenty-six patients had medial guided growth procedures for valgus deformity, and 3 patients had lateral guided growth procedures for varus deformity. Concomitant surgery included patellar instability surgery (Fig. 1), OCD drilling or fixation, ACL reconstruction, and meniscal surgery. The 4 valgus patients undergoing OCD procedures had lateral femoral condyle OCD lesions. Similarly, the 4 valgus patients undergoing a meniscus procedure had lateral meniscus pathology. The 3 varus patients undergoing OCD procedures had medial femoral condyle OCD lesions. The average age at the time of surgery was 12.8 ± 1.8 years. There were 17 male and 12 female patients. Of the 12 patients who did not have postoperative measurements, all had follow-up of at least 6 months. Of the 17 patients with postoperative measurements, 13 had guided growth plates removed at an average of 13.1 ± 6.2 months after the initial procedure. Four patients retained implants at their most recent follow-up; of these 2 had radiographic follow-up at least 1 year after surgery, 1 was scheduled to have the plate removed, and 1 had reached skeletal maturity but chose not to have removal of hardware. Relevant medical history included melorheostosis in 1 patient in the ACL group, fixed patellar dislocation in 1 patient in the PFI group, Down syndrome in 1 patient in the PFI group, and chronic recurrent multifocal osteomyelitis in 1 patient in the OCD group.

Figure 1.

Patient treated for valgus alignment and patellofemoral instability. (a) Preoperative radiographs showing valgus alignment of left knee, (b) 9-month postoperative radiograph showing tension band plate implant across the lateral distal femoral physis of the left knee, (c) radiographs performed 18 months postoperatively showing full correction of initial valgus deformity. Patient reached skeletal maturity and opted to retain the implant.

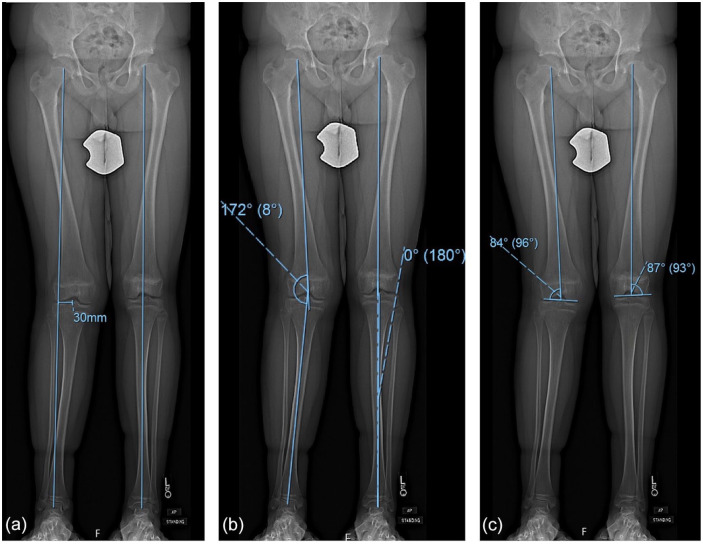

Radiographic measurements were performed using the institutional picture archiving and communication system (PACS, Sectra Imtec AB, Sweden). Three measurements were performed as previously described by Paley et al: (1) mechanical tibiofemoral angle (mTFA) was calculated as the angle between the mechanical axis of the femur and the mechanical axis of the tibia, (2) MAD was calculated as the perpendicular distance between the limb mechanical axis and the center of the tibial eminence, and (3) mechanical lateral distal femoral angle (mLDFA) was calculated as the angle between the mechanical axis of the femur and line parallel to the lateral femoral condyles (Fig. 2) [21]. Measurements were performed on preoperative standing hip-to-ankle radiographs in all patients (N = 29). Follow-up measurements were only made for patients who had an available standing hip-to-ankle radiograph at least 1 year from surgery, had guided growth hardware removed or scheduled to be removed at latest follow-up, or had reached skeletal maturity and chose not to have hardware removed (N = 17). Two raters, a senior resident and a pediatric orthopedics research assistant (B.K.E. and A.H.A.), performed measurements on a set of 40 radiographs to establish interrater reliability. Substantial agreement was obtained, and a single rater assessed all remaining images. The mean of measurements performed by both raters was used for the purpose of subsequent statistical analysis.

Figure 2.

(a) Example of measuring mechanical axis deviation (MAD). Mechanical axis line is drawn from the center of the femoral head to the center of the tibial plafond. The distance between the center of the knee (here center of tibial spines) and the mechanical axis line is the mechanical axis deviation, which in this case is 30 mm lateral. (b) mTFA is defined as the angle that forms between mechanical axis line of femur (line between center of femoral head and center of trochlea) and mechanical axis line of tibia (line between center of tibial spines and center of plafond). (c) mLDFA is defined as the lateral angle that forms between mechanical axis line of femur (center of femoral head to center of trochlea) and a line drawn parallel to the condyles. Numbers in parentheses are the complements to mLDFA. mTFA mechanical tibiofemoral, mLDFA mechanical lateral distal femoral angle.

Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York). A 2-way random single-measures intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) with absolute agreement and a 95% confidence interval (CI) was used to determine interrater reliability. Continuous demographic variables were reported as means and standard deviations based on a normal distribution, whereas categorical variables were reported as frequencies and percentages. An unpaired Student t test was used to compare preoperative and postoperative measurements. A P value of ≤ .05 was used as the threshold of statistical significance, and all tests were 2-tailed.

Results

The ICC was 0.975 (95% CI: 0.914-0.990) for MAD, 0.991 (95% CI: 0.756-0.998) for mTFA, and 0.980 (95% CI: 0.963-0.995) for mLDFA measurements, indicating almost perfect interrater reliability of these measurements [17]. For the 15 valgus patients, average mTFA was 6.2° valgus preoperatively, and average postoperative mTFA was 0.3° valgus (P < .0001), indicating successful correction of mechanical axis to neutral (Table 2). There was 1 valgus patient who had initial correction to neutral but, following plate removal, had significant rebound back into valgus. For the 2 varus patients, average mTFA was 4.8° varus preoperatively, and average postoperative mTFA was 3.7° varus (P = .370) (Table 3). Both of these patients had initial correction to neutral but rebounded into mild varus after removal of the plate.

Table 2.

Preoperative and postoperative deformity measurements on hip-to-ankle radiographs of valgus patients with appropriate follow-up.

| Preoperative | Postoperative | P value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAD, mm | mTFA, degrees | mLDFA, degrees | MAD, mm | mTFA, degrees | mLDFA, degrees | MAD, mm | mTFA, degrees | mLDFA, degrees | |

| Patellar Instability (N = 5) | 18.8 ± 6.2 | 6.3 ± 1.5 | 85.7 ± 2.9 | 2.7 ± 8.4 | 0.2 ± 2.7 | 89.6 ± 0.9 | .009 | 0.002 | 0.040 |

| ACL Reconstruction (N = 5) | 21.8 ± 5.2 | 6.5 ± 0.7 | 83.2 ± 1.8 | 0.3 ± 5.3 | 0.6 ± 1.9 | 88.1 ± 3.3 | <.000 | <0.000 | 0.020 |

| OCD Drilling/Fixation (N = 4) | 20.8 ± 5.9 | 5.8 ± 1.9 | 86.1 ± 1.2 | 4.2 ± 13.0 | 1.3 ± 4.7 | 90.3 ± 1.8 | .059 | 0.123 | 0.007 |

| Meniscus Repair (N = 1) | 17.4 | 5.8 | 87.7 | −9.8 a | −3.9 a | 92.0 | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Total/Average (N = 15) | 20.3 ± 5.3 | 6.1 ± 1.3 | 85.1 ± 2.4 | 1.5 ± 8.7 | 0.3 ± 3.0 | 89.4 ± 2.5 | <.000 | <0.000 | <0.000 |

MAD mechanical axis deviation, mTFA mechanical tibiofemoral, mLDFA mechanical lateral distal femoral angle, ACL anterior cruciate ligament, OCD osteochondritis dissecans.

Negative numbers denote overcorrection of the original deformity.

Table 3.

Preoperative and postoperative deformity measurements on hip-to-ankle radiographs of varus patients with appropriate follow-up.

| Preoperative | Postoperative | P value | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAD, mm | mTFA, degrees | mLDFA, degrees | MAD, mm | mTFA, degrees | mLDFA, degrees | MAD, mm | mTFA, degrees | mLDFA, degrees | |

| OCD Drilling/Fixation (N = 2) | 16.6 ± 6.6 | 4.8 ± 1.4 | 89.1 ± 1.5 | 13.6 ± 2.9 | 3.7 ± 0.1 | 88.2 ± 1.9 | 0.615 | 0.370 | 0.656 |

MAD mechanical axis deviation, mTFA mechanical tibiofemoral, mLDFA mechanical lateral distal femoral angle, OCD osteochondritis dissecans.

Outcomes from surgeries included 3 complications: 1 patient with ACL graft rupture required revision, 1 patient with recurrent instability after medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction required revision, and 1 patient with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) that resolved with therapy. There were no postoperative infections or arthrofibrosis.

Discussion

This small study of skeletally immature patients who underwent concomitant surgery for intra-articular knee pathology and IMGG with tension band plating sought to demonstrate whether concomitant surgery is feasible. Of the 17 patients who were assessed for deformity correction, 16 had mTFA of <5° of varus or valgus at final follow-up, indicating successful correction of deformity; complications included 1 ACL graft rupture, 1 MPFL reconstruction failure, and 1 case of CRPS, and there were no postoperative infections or arthrofibrosis requiring manipulation under anesthesia.

There are many limitations in this small, retrospective study. First, as this was a study of a relatively uncommon combination of procedures performed at a single institution, there were only a small number of patients eligible for inclusion. In addition, not all patients had their plates removed or had more than 1 year of follow-up. If plates were removed prior to skeletal maturity and patients did not follow-up, they may have experienced rebound that was not recognized in this study. However, as all patients had at least 6 months of follow-up, this study was able to determine the incidence of iatrogenic or perioperative complications associated with concomitant IMGG. Procedures performed for ACL reconstruction, OCD, meniscus repair/meniscectomy, and patellar instability were not uniform, even when looking at procedures performed by the same surgeon. For example, ACL reconstructions were performed using all-epiphyseal, transphyseal, and modified McIntosh techniques, depending on the age of the patient and surgeon preference. Some OCDs were fixed and some were drilled, depending on the stability of the lesion. Meniscus lesions were repaired using different techniques and others were deemed irreparable and a partial meniscectomy was performed. Patellar stabilizing procedures included MPFL reconstructions in 10 patients and medial patellar plication in 2 patients. The MPFL reconstructions varied in graft type and fixation. However, the lack of uniformity of each procedure as noted above and multiple surgeons included may increase the generalizability of the study. Notably, this study was not intended to be a technique study comparing different techniques for each pathology.

Excess valgus stress may predispose patients to ACL rupture [16]. O’Brien et al published a retrospective review of 8 skeletally immature patients with genu valgum and ACL rupture who underwent transphyseal ACL reconstruction and concomitant hemiepiphysiodesis [20]. Their results were comparable with each procedure in isolation—1 patient had a rupture of ACL graft (13%) and all treated limbs corrected to near-neutral alignment. Our results were comparable—1 out of 7 (14%) patients treated with concomitant ACL reconstruction and guided growth suffered ACL graft rupture.

Multiple studies have demonstrated an association between OCD location (medial or lateral femoral condyle) and lower limb MAD [6,12,14]. While not all patients with OCD lesions have CPAD, when they do occur OCD lesions are more likely on the medial femoral condyle in varus malalignment and on the lateral femoral condyle in valgus malalignment. In our study, all 4 patients with valgus malalignment had lateral femoral condyle OCD lesions, and all 3 patients with varus malalignment had medial femoral condyle OCD lesions. In addition, Gonzalez-Herranz et al found that convergence of OCD location and CPAD was more common in knees with unstable OCD lesions Thus, while there are certainly other etiologies at play, CPAD seems to be a contributing factor in the development or severity of OCD lesions. It is therefore reasonable to address a CPAD surgically with IMGG concurrently with drilling or fixation of an OCD lesion.

Rebound is a common phenomenon in IMGG after implant removal. Significant rebound was defined in this study as mTFA of greater than 5° varus or valgus at final follow-up after initial correction to neutral. This occurred in 1 valgus patient from the OCD group. Rebound is thought to occur due to the ipsilateral hemiphysis temporarily growing at a faster rate than the contralateral side of the physis after implant removal, resulting in some loss of alignment correction [15]. The reported incidence of rebound is variable. Four patients (12%) in Stevens’ [26] preliminary series with bilateral idiopathic genu valgum experienced rebound requiring repeat IMGG [26]. Recently, Park et al found that a faster rate of correction, body mass index, age, and initial valgus angle were significantly associated with a rebound phenomenon after removal of hemiepiphyseal staples [23]. The age at IMGG is strongly associated with rate of correction, and young patients with significant growth remaining are at higher risk for rebound. Patients and parents should be counseled about the possibility of rebound and patients should be followed until skeletal maturity to ensure that significant rebound does not occur. It can be addressed with either observation or repeat IMGG if it is significant and there is growth remaining. An osteotomy may be required if the patient is close to skeletal maturity.

In adults, varus malalignment has been associated with medial meniscus pathology and valgus malalignment has been associated with lateral meniscus pathology [8,10]. While these studies do not include pediatric patients, correcting CPAD in a child who has both malalignment and a meniscus tear may decrease risk for recurrence as an adult, based on these findings.

Patellar instability is often associated with genu valgum [3]. Kearney and Mosca reported on 26 skeletally immature knees with patellar instability and genu valgum that underwent hemiepiphysiodesis alone for CPAD correction [15]. They found that patellar instability symptoms completely resolved in 69% of patients and 31% had a significant reduction in symptoms. Wilson et al [29] reported on 11 skeletally mature patients below 19 years of age who underwent isolated distal femoral osteotomy for recurrent traumatic patellar instability [29]. Of these patients 70% reported good to excellent function and 80% had no further episodes of instability. These studies demonstrate that mechanical alignment clearly plays a role in patellofemoral stability, although it is unclear exactly how much of a role relative to other stabilizers such as the MPFL. Parikh et al reported on 7 patients (8 knees) with concurrent MPFL reconstruction and IMGG with medial transphyseal screw insertion [22]. The researchers found the results were satisfactory with improvement of anatomic valgus from 13.1° preoperatively to 3.7° and only 1 patient with recurrent dislocations requiring revision.

Based on this small study, concomitant MPFL reconstruction and medial femoral hemiepiphysiodesis with tension band plating appear to be feasible and effective. Only 1 patient in our study had recurrent PFI requiring revision surgery, and this patient initially presented with a fixed dislocation. In our patients, the fixation for the femoral limb of the MPFL was typically distal and posterior to the epiphyseal-guided growth screw. Given the close proximity, we recommend noting the exact relationship between the femoral limb fixation and the distal guided growth screw in the operative report. This improves the surgeon’s ability to locate and remove the hardware at a later time without disturbing the graft.

Arthrofibrosis has been associated with ACL reconstruction and soft tissue procedures of the knee (meniscus) in pediatric patients [9]. In adult patients, concomitant extra-articular procedures with ACL reconstruction may be a risk factor for the development of arthrofibrosis due to increased trauma around the knee [18]. It is notable that no patients in our study developed athrofibrosis, required manipulation under anesthesia, or had wound complications after concomitant IMGG.

In general, pathologic CPAD is an indication for IMGG of the lower extremities [30]. The degree of coronal plane malalignment leading to degenerative changes is unknown, and thus there is no absolute cut-off value for consideration of IMGG. We begin considering IMGG in patients with greater than 5° varus or valgus deformity with sufficient growth remaining to allow for correction. Guided growth is contraindicated in patients with a physeal bone bar [11] or closed physes or in patients who are within 12 to 24 months of physeal closure [1]. In addition, adequate hip-to-ankle radiographs need to be obtained to diagnose CPAD. Adequate radiographs require the patient to stand with bilateral knees in full extension with the patellae facing forward. If the patient is unable to fully extend the knee in the radiograph due to concomitant injury or effusion, the measurements will be inaccurate and a neutrally aligned extremity may appear to have an angular deformity or leg length discrepancy [13]. As always, a good clinical examination is important to ensure the patient is able to fully extend the knee and does so in the standing radiograph. Without adequate radiographs in a patient who has significant growth remaining, the guided growth procedure should be delayed until after the concomitant knee pathology has been addressed and adequate standing films can be obtained.

In conclusion, CPAD is a known modifiable risk factor for several common intra-articular pediatric knee conditions and should be recognized at the time of presentation. The CPAD can be treated using IMGG in skeletally immature patients concurrently with intra-articular knee pathology. Future research should focus on exact thresholds and indications for IMGG, when to address bilateral deformity in the setting of unilateral pathology, and patient-reported outcomes after concomitant surgery.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-hss-10.1177_15563316211010720 for Use of Implant-Mediated Guided Growth With Tension Band Plate in Skeletally Immature Patients With Knee Pathology: A Retrospective Review by Bridget K. Ellsworth, Alexandra H. Aitchison, Peter D. Fabricant and Daniel W. Green in HSS Journal®: The Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Bridget K. Ellsworth, MD; Alexandra H. Aitchison, BS; Peter D. Fabricant MD, MPH; declare they have no conflicts of interests. Daniel W. Green, MD, MS, FACS, reports relationships with Arthrex and PegaMedical, outside the submitted work.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Human/Animal Rights: All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was waived from all patients included in this study.

Level of Evidence: Level IV: Retrospective Therapeutic Study

Required Author Forms: Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the online version of this article as supplemental material.

References

- 1. Anderson M, Green WT, Messner MB. The classic. Growth and predictions of growth in the lower extremities by Margaret Anderson, M.S., William T. Green, M.D. and Marie Blail Messner, A.B. from the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery, 45A:1, 1963. Clin Orthop. 1978;136:7–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ballal MS, Bruce CE, Nayagam S. Correcting genu varum and genu valgum in children by guided growth: temporary hemiepiphysiodesis using tension band plates. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(2):273–276. 10.1302/0301-620X.92B2.22937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Boden B, Pearsall A, Garrett W, Feagin J. Patellofemoral instability: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1997;5(1):47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boero S, Michelis MB, Riganti S. Use of the eight-plate for angular correction of knee deformities due to idiopathic and pathologic physis: initiating treatment according to etiology. J Child Orthop. 2011;5(3):209–216. 10.1007/s11832-011-0344-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bowen JR, Leahey JL, Zhang ZH, MacEwen GD. Partial epiphysiodesis at the knee to correct angular deformity. Clin Orthop. 1985;198:184–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brown ML, McCauley JC, Gracitelli GC, Bugbee WD. Osteochondritis dissecans lesion location is highly concordant with mechanical axis deviation. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(4):871–875. 10.1177/0363546520905567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Castañeda P, Urquhart B, Sullivan E, Haynes RJ. Hemiepiphysiodesis for the correction of angular deformity about the knee. J Pediatr Orthop. 2008;28(2):188–191. 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181653ade. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Englund M, Felson DT, Guermazi A, et al. Risk factors for medial meniscal pathology on knee MRI in older US adults: a multicentre prospective cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70(10):1733–1739. 10.1136/ard.2011.150052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fabricant PD, Tepolt FA, Kocher MS. Range of motion improvement following surgical management of knee arthrofibrosis in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(9):e495–e500. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Felson DT, Niu J, Gross KD, et al. Valgus malalignment is a risk factor for lateral knee osteoarthritis incidence and progression: findings from MOST and the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65(2):355–362. 10.1002/art.37726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Goldman V, Green DW. Advances in growth plate modulation for lower extremity malalignment (knock knees and bow legs). Curr Opin Pediatr. 2010;22(1):47–53. 10.1097/MOP.0b013e328334a600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Gonzalez-Herranz P, Rodriguez ML, de la Fuente C. Femoral osteochondritis of the knee: prognostic value of the mechanical axis. J Child Orthop. 2017;11(1):1–5. 10.1302/1863-2548-11-160173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Heath MR, Aitchison AH, Schlichte LM, et al. Use caution when assessing preoperative leg-length discrepancy in pediatric patients with anterior cruciate ligament injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2020;48(12):2948–2953. 10.1177/0363546520952757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jacobi M, Wahl P, Bouaicha S, Jakob RP, Gautier E. Association between mechanical axis of the leg and osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: radiographic study on 103 knees. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(7):1425–1428. 10.1177/0363546509359070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kearney SP, Mosca VS. Selective hemiepiphyseodesis for patellar instability with associated genu valgum. J Orthop. 2015;12(1):17–22. 10.1016/j.jor.2015.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kimura Y, Ishibashi Y, Tsuda E, Yamamoto Y, Hayashi Y, Sato S. Increased knee valgus alignment and moment during single-leg landing after overhead stroke as a potential risk factor of anterior cruciate ligament injury in badminton. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46(3):207–213. 10.1136/bjsm.2010.080861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Magit D, Wolff A, Sutton K, Medvecky MJ. Arthrofibrosis of the knee. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(11):682–694. 10.5435/00124635-200711000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Nyland JA, Caborn DNM. Physiological coxa varus–genu valgus influences internal knee and ankle joint moments in females during crossover cutting. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12(4):285–293. 10.1007/s00167-003-0430-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. O’Brien AO, Stokes J, Bompadre V, Schmale GA. Concomitant anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and temporary hemiepiphysiodesis in the skeletally immature: a combined technique. J Pediatr Orthop. 2019;39(7):e500–e505. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Paley D, Herzenberg JE, Tetsworth K, McKie J, Bhave A. Deformity planning for frontal and sagittal plane corrective osteotomies. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25(3):425–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parikh SN, Redman C, Gopinathan NR. Simultaneous treatment for patellar instability and genu valgum in skeletally immature patients: a preliminary study. J Pediatr Orthop Part B. 2019;28(2):132–138. 10.1097/BPB.0000000000000546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Park SS, Kang S, Kim JY. Prediction of rebound phenomenon after removal of hemiepiphyseal staples in patients with idiopathic genu valgum deformity. Bone Jt J. 2016;98-B(9):1270–1275. 10.1302/0301-620X.98B9.37260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Price MJ, Tuca M, Cordasco FA, Green DW. Nonmodifiable risk factors for anterior cruciate ligament injury. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2017;29(1):55–64. 10.1097/MOP.0000000000000444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shin YW, Trehan SK, Uppstrom TJ, Widmann RF, Green DW. Radiographic results and complications of 3 guided growth implants. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(7):360–364. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000000825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stevens PM. Guided growth for angular correction: a preliminary series using a tension band plate. J Pediatr Orthop. 2007;27(3):253–259. 10.1097/BPO.0b013e31803433a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tanamas S, Hanna FS, Cicuttini FM, Wluka AE, Berry P, Urquhart DM. Does knee malalignment increase the risk of development and progression of knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61(4):459–467. 10.1002/art.24336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Wiemann JM, Tryon C, Szalay EA. Physeal stapling versus 8-plate hemiepiphysiodesis for guided correction of angular deformity about the knee. J Pediatr Orthop. 2009;29(5):481–485. 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181aa24a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson PL, Black SR, Ellis HB, Podeszwa DA. Distal femoral valgus and recurrent traumatic patellar instability: is an isolated varus producing distal femoral osteotomy a treatment option? J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(3):e162–e167. 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yang I, Gottliebsen M, Martinkevich P, Schindeler A, Little DG. Guided growth: current perspectives and future challenges. JBJS Rev. 2017;5(11):e1. 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.16.00115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-hss-10.1177_15563316211010720 for Use of Implant-Mediated Guided Growth With Tension Band Plate in Skeletally Immature Patients With Knee Pathology: A Retrospective Review by Bridget K. Ellsworth, Alexandra H. Aitchison, Peter D. Fabricant and Daniel W. Green in HSS Journal®: The Musculoskeletal Journal of Hospital for Special Surgery