Abstract

A new bicyclic diterpenoid, benditerpenoic acid, was isolated from soil-dwelling Streptomyces sp. (CL12-4). We sequenced the bacterial genome, identified the responsible biosynthetic gene cluster, verified the function of the terpene synthase, and heterologously produced the core diterpene. Comparative bioinformatics indicated this Streptomyces strain is phylogenetically unique and possesses nine terpene synthases. The absolute configurations of the new trans-fused bicyclo[8.4.0]tetradecanes were achieved by extensive spectroscopic analyses, including Mosher’s analysis, J-based coupling analysis, and computations based on sparse NMR-derived experimental restraints. Interestingly, benditerpenoic acid exists in two distinct ring-flipped bicyclic conformations with a rotational barrier of ~16 kcal mol−1 in solution. The diterpenes exhibit moderate antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria including methicillin and multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. This is the first isolation of an eunicellane-type diterpenoid from bacteria and the first identification of a diterpene synthase and biosynthetic gene cluster responsible for the construction of the eunicellane scaffold.

Keywords: Natural Products, Diterpenoid, Terpene Synthase, Antibiotics, Absolute Configuration, DFT

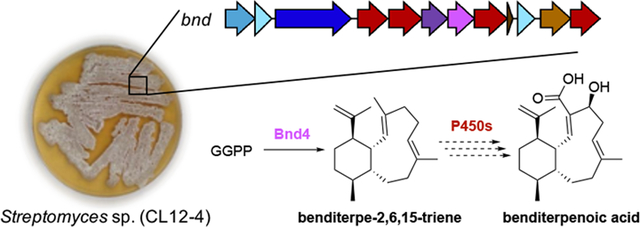

Graphical Abstract

We report the first isolation of an eunicellane-type diterpenoid from bacteria and the first identification of a diterpene synthase and biosynthetic gene cluster responsible for the construction of the eunicellane scaffold. The absolute configurations and antibacterial activities of benditerpenoic acid and the benditerpe-2,6,15-triene core were established.

Introduction

Terpenoids, found in all branches of the tree of life, are the largest and most structurally diverse class of natural products with more than 80,000 known compounds.[1] Terpenoids exhibit a wide range of biological activities including, but not limited to, antibacterial, antifungal, antiparasitic, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties.[2] Although these natural products were first, and are still most commonly, isolated from plants and fungi, bacteria are emerging as talented producers of unique and biologically active terpenoids.[2b, 3] This fact coincides with the genomic knowledge supporting that bacteria possess an abundance of uncharacterized terpene synthases (TSs), the enzymes responsible for formation of the terpenoid core, and TS-encoding biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs).[4]

The first described terpenes from actinomycetes were the odoriferous geosmin and the camphor-like 2-methylisoborneol, both reported in the late 1960s and associated with the smell of wet soil.[5] The advent of genome sequencing revealed that TSs are widely distributed in bacteria, particularly in actinomycetes, the workhorses of bacterial natural products.[4, 6] In some cases (e.g., geosmin), the products of bacterial TSs are legitimate natural products and not simply biosynthetic intermediates on a pathway to more complex and functional terpenoids. Most terpenoid natural products, however, are highly functionalized scaffolds. Significant progress has been made in bacterial terpene chemistry by identifying unique TSs and characterizing their enzymatic products using heterologous expression or in vitro methods.[4, 7] Yet, the biosynthetic products of TS-encoding BGCs continue to be exceedingly rare to find with one plausible reason being that many of these BGCs may be silent under laboratory conditions.[4] Therefore, there is a clear need to bridge the gap between the products of TSs and their genuine natural products. Continued discovery of novel bacterial terpenoids and unique terpene scaffolds will facilitate future genome mining opportunities.

Herein, we report the isolation and characterization of a newly discovered diterpenoid scaffold produced by a Streptomyces sp., isolated from arid, high desert soil near Bend, Oregon. Due to the slow chemical exchange from two ring-flipped conformers for benditerpenoic acid (1) and four conformers for the unfunctionalized core benditerpe-2,6,15-triene (2) in solution, structure elucidation by NMR spectroscopy was a significant challenge. The natural occurring trans-fused bicyclo[8.4.0]tetradecane contains five stereogenic centers, the heterologously expressed core exhibits four stereocenters, and both exhibit two double bond geometries within the bicycle. The absolute configurations of the new diterpenoids were assigned independently as 1S, 2Z, 4S, 6E, 10R, 11S, 14R for benditerpenoic acid and 1S, 2E, 6E, 10R, 11S, 14R for the benditerpe-2,6,15-triene core using a combination of Mosher ester analysis[8], 2D NMR experiments including J-based analysis (JBCA)[9], and computational modeling. Subsequent genome sequencing and bioinformatic analysis revealed the BGC responsible for the production of 1. Finally, biochemical characterization of benditerpe-2,6,15-triene synthase, the type I TS encoded within the bnd BGC, confirmed it constructs the trans-fused bicyclo[8.4.0]tetradecane scaffold from GGPP and provided insight into the biosynthesis of 1.

Results and Discussion

Isolation and structural elucidation of benditerpenoic acid

Bioactivity-guided fractionation (Figure S1) led to the isolation of benditerpenoic acid (1) as a white powder with a chemical formula of C20H30O3 based on HRESIMS m/z 319.2269 (Δppm = 0.3; calcd for C20H31O3+ 319.2268; Figure S2). The UV spectrum exhibited absorbance maxima at 210 and 228 nm (Figure S3) and its IR bands were supportive of hydroxyl groups (3446 cm−1) and carbonyl (1697 cm−1), and a terminal alkene (2922 cm−1). The structure and relative configuration of the new terpenoid was derived from 1H-, 13C- and 2D NMR experiments, including COSY, NOESY, ROESY, TOCSY, HSQC and HMBC (Table S1, Figure 1A and 1B, Figures S4–S20); detailed analysis of the NMR data resulting in the structural elucidation of 1 can be found in the Supporting Information. Observation of doubled resonances from both proton and carbon spectra as well as chemical exchange crosspeaks in NOESY spectra suggested that 1 undergoes slow chemical exchange.

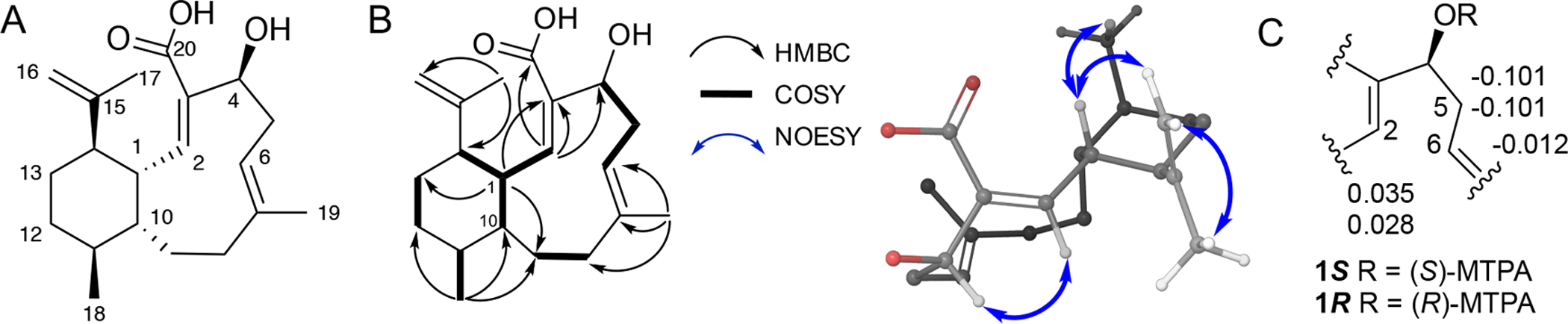

Figure 1.

(A) Structure of benditerpenoic acid (1). (B) Key COSY, HMBC, NOESY correlations. (C) Modified Mosher’s analysis of C-4 hydroxyl. Values given at C-2, C-5, and C-6 are Δδ(S)–(R).

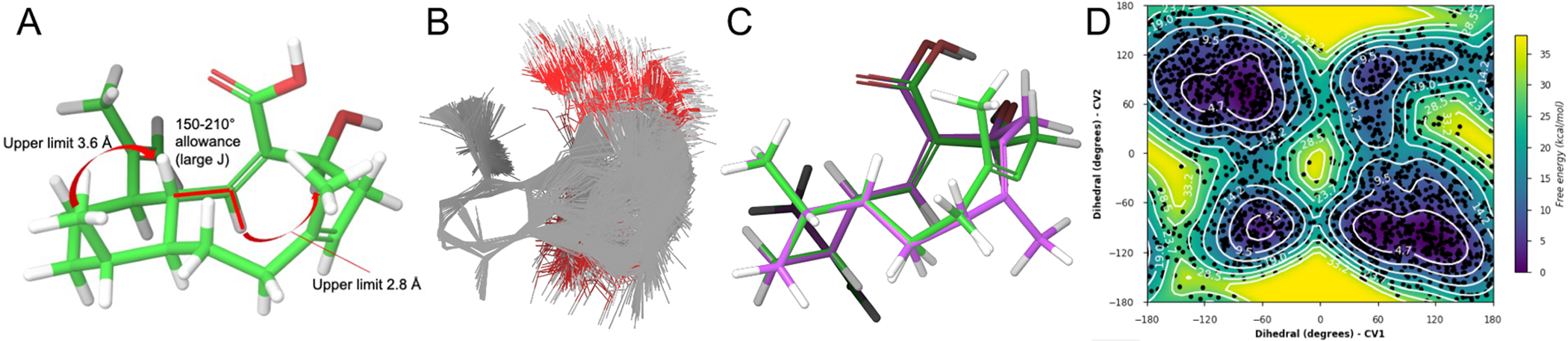

To determine the relative and absolute configuration of benditerpenoic acid (1), which possesses five asymmetric carbon centers and a flexible, bicyclic ring system, modified Mosher ester analysis,[8] analysis of NOESY and J-based couplings supported by density functional theory (DFT) computations were used.[9] Mosher ester analysis unequivocally determined C-4 to be S configured (Figure 1C, Figure S21). With the absolute configuration of the secondary alcohol defined, NOESY and J-based conformational analysis were used to determine the remaining four stereocenters. H-1 exhibits a doublet of doublets of doublets (ddd) pattern with two large coupling constants (11.0 and 10.3 Hz) and one small one (4.3 Hz), indicating two trans and one cis relationship between this and the adjacent stereocenters of the decalin ring system. Based on the DQF-COSY data extraction, the 3J(H-2,H-1) coupling constant is 10.0 Hz in both conformers supporting the orientation to be trans and accounting for one of the two large coupling constants within the ddd multiplet of H-1 (Figure S16–18). The NOESY spectrum showed a strong NOE correlation from H-1 to CH3-17, placing them cis to one another and accounting for the second large coupling constant (3JH-1,H-14 = 11.0 Hz). This was further corroborated by a very weak NOE correlation from H-1 to H-14 suggesting a trans orientation (Figure S9). Thus, H-1 and H-10, supported by the small coupling constant (3JH-1,H-10 = 4.3 Hz) have a cis configuration. Additionally, a strong NOE between H-1 and H-18 indicates a cis configuration. A strong NOE correlation between H-2 and H-4 was found in both conformers in the NOESY spectrum, setting the geometry of the C-2/C-3 double bond as Z. IPAP-HMBC NMR data displayed the 3J(H-6,C-19) coupling to be approximately 7 Hz in both ring conformers indicating that the C-6/C-7 double bond is E configured (Figure S19).[10] A very small coupling constant 4J(H-1,C-18), approximately 1 Hz, suggests a cis configuration between H-1 to C-18 (Figure S20). These values were corroborated by DFT calculations of coupling constants (see SI for more detail). Combined, the Mosher ester analysis, NOESY data, and JBCA provide an absolute configuration of 1S,2Z,4S,6E,10R,11S,14R for 1. Next, we employed 3D structural computation of conformers to support the assignment of the absolute configuration. Here, the conformational space of 1 was calculated using ForceGen (BioPharmics LLC, v4.4) by applying minimal distance and torsion restraints derived from NOE and J values, namely the observed NOE between H-1 and H-4 and between H-1 and 18-CH3, and the 3JHH between H-1 and H-2, to guide accurate conformational sampling (Figure 2A).[11] From this conformational ensemble, the Boltzmann population was computed by DFT at the MPW1PW91/cc-PVTZ level and the two lowest energy conformers were found to exhibit an up/down flip of the bicyclic ring (Figure 2C). The bicycle has two distinct low energy forms (i.e., methyl up in green and methyl down in purple) with nearly identical energies. Metadynamics simulations indicated a rotational barrier from a low energy conformation, through a local minimum, to the other low energy minimum, with an ~16 kcal mol−1 maximum barrier pathway between the two minima (Figure 2D). This observation explains the chemical exchange shown in the NOESY/ROESY spectra of 1. The Boltzmann populations are approximately 3:2, which matches the integration ratios observed in the 1H NMR (Table S1). Computationally derived UV and ECD data at the ωB97XD/def2TZVP//MPW1PW91/cc-PVTZ level compared with experimental spectra further support the stereochemical assignment of benditerpenoic acid (1) (Figure S22).

Figure 2.

(A) Three NMR-derived ForceGen restraints were utilized to generate an experimentally guided conformational search for 1. (B) 693 conformations were found which exhibited no restraint violations. (C) DFT analysis of the conformer ensemble above produced a Boltzmann distribution in which the two lowest energy conformers (ΔG 0.06 kcal mol−1) exhibit a flip of the bicycle from ‘methyl up’ (green) to ‘methyl down’ (purple). (D) Metadynamics simulations indicate the barrier to flip is approximately 16 kcal mol−1.

Structurally related compounds

Compared with other families of diterpenoids, bacterial diterpenoids are rare.[2b] The closest structural relatives are the 6,8,4- and 6,7,5-tricyclic odyverdienes and 6,10-bicyclic pre-hydropyrene, which were isolated from the heterologous expression of di-TSs (i.e., not as genuine natural products; Figure S23).[7b, 12] Interestingly, pre-hydropyrene is reported as a neutral, but unstable, intermediate on the pathway to hydropyrene and hydropyrenol, which feature unique 6,6,6,6-tetracyclic scaffolds.[7b, 12] The 6,10-bicyclic eunicellane scaffold has been found in corals[13] with examples including the solenopodins,[14] klysimplexins,[15] and excavatolides (Figure S23).[16] Some references allude to their dynamic behavior in solution and the challenges encountered when assigning their respective structures.[16b] Recently, vibrational circular dichroism experiments and computational approaches were used to elucidate the absolute configuration of Gorgonian-derived briaranes.[17] Of these structurally related diterpenoids, there are no known bacterial natural products with the eunicellane-type skeleton nor known di-TSs responsible for constructing the 6,10-bicyclic eunicellane core. Although the 6,10-bicyclic skeletons of 1 and the coral eunicellanes are the same, the differences in their stereocenters and double bond placement and configurations suggest that the di-TSs that construct these 6,10-bicyclic skeletons are different.

Identification of the bnd BGC by genome mining for unique TSs

Given the novelty of the eunicellane-type skeleton of 1 from bacteria, we sought to identify the TS and BGC responsible for constructing and functionalizing the 6,10-bicyclic core. We sequenced the genome of Streptomyces sp. (CL12-4) using Oxford Nanopore and Illumina sequencing technologies. The draft genome is ~9.01 Mb in total length, 71.92% GC content, and currently assembled into 16 contigs with the largest contig ~2.05 Mb; two contigs were assembled into circular plasmids of 0.13 and 0.08 Mb. A multi-gene phylogenetic analysis of Streptomyces sp. (CL12-4) positioned it in its own clade near Streptomyces ambofaciens (five-gene concatenation 97.6% sequence identity) and Streptomyces rochei (96.8%) (Figure S24).

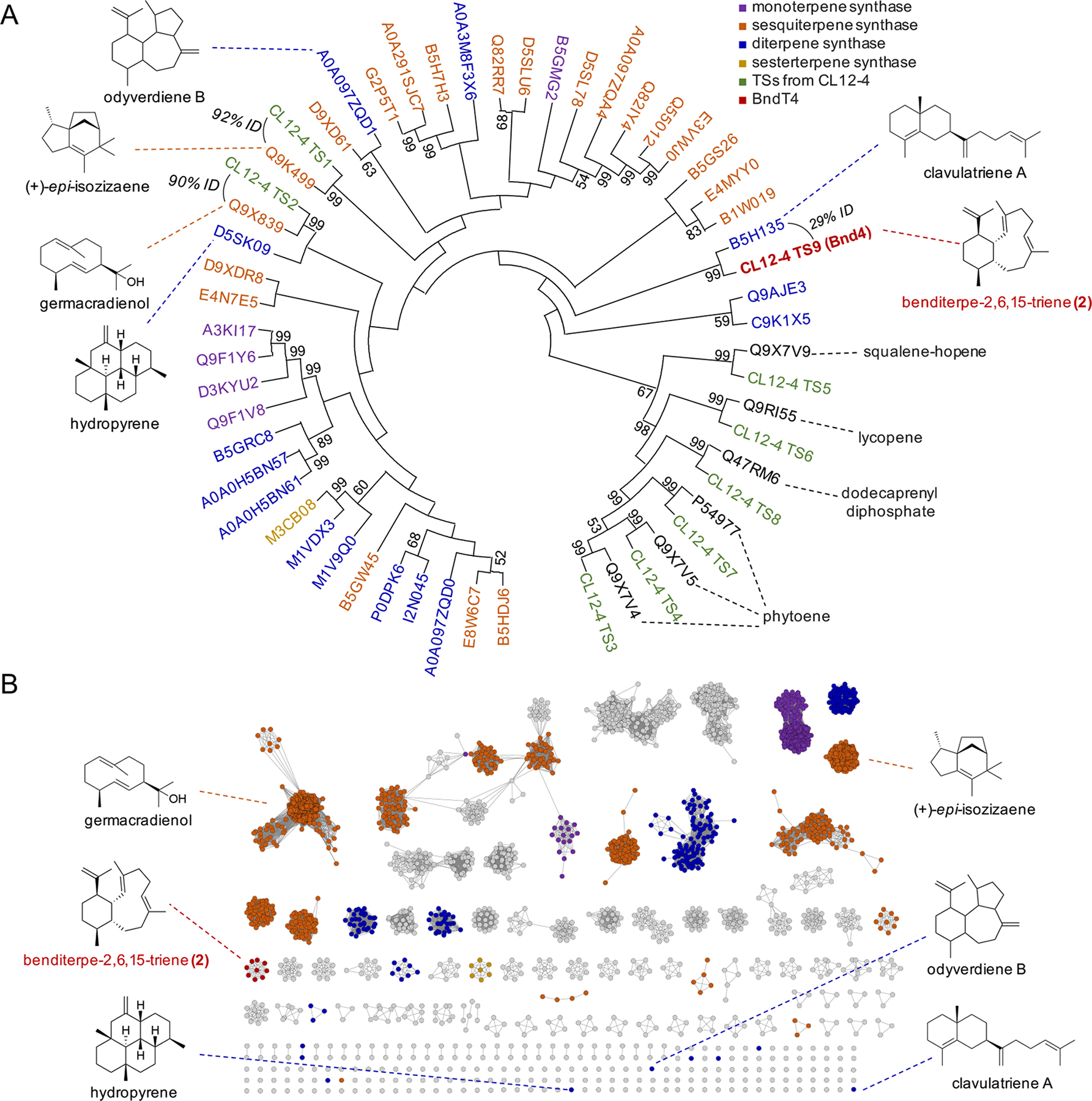

Using a combination of antiSMASH[18] and BLAST[19], we detected a total of nine putative TSs encoded within the genome. Sequence comparisons and phylogenetic analysis of these nine TSs with characterized TSs from Streptomyces revealed two sesqui-TSs (germacradienol/geosmin and (+)-epi-isozizaene synthases), one putative di-TS, and six additional proteins that are highly similar to ubiquitous TSs such as phytoene synthase (Figure 3A). The candidate di-TS, later named Bnd4, claded with the di-TS SCLAV_p1169, a clavulatriene synthase from Streptomyces clavuligerus,[4, 7b] with pairwise alignment between Bnd4 and SCLAV_p1169 showing only 29% sequence identity. As phylogenetic clading of bacterial TSs can be misleading due to high sequence disparities between TSs, we next constructed a sequence similarity network (SSN) of all known and putative TSs from the Streptomycetaceae family (Figure 3B).[20] At an e-value threshold of 10−60, many families of TSs segregate into individual subfamily clusters. Bnd4 was found in an uncharacterized subcluster with eight other TSs. SCLAV_p1169, odyverdiene synthase, and hydropyrene synthase were all found as singletons, highlighting their diverse sequences.

Figure 3.

Sequence analysis of the TSs found in Streptomyces sp. (CL12-4). (A) Phylogenetic analysis of the nine TSs found in the genome of CL12-4. Characterized TSs from Streptomyces are labeled with their UniProt accession numbers. Colored labels (shown in legend) indicate the type of terpene synthase. Structures discussed in the text are shown with their associated TSs. Bootstrap values >50% (based on 1000 resampled trials) are given at nodes. (B) Sequence similarity network of TSs from Streptomyceae at an e-value threshold of 10−60. Clusters of TSs are colored corresponding to the legend in (A) and based on the characterized TSs found within. The eight homologous TSs from actinobacteria were included to highlight their similarity to Bnd4.

Sequence analysis of Bnd4 and eight highly homologous (>40% identity) TSs revealed canonical DDxxD and NSE metal-binding motifs as well as the C-terminal WxxxxxRY motif that is responsible for guiding product formation (W) and sensing the diphosphate moiety (RY) (Figure S25).[21] The NSE and WxxxxxRY motifs are strictly conserved in these TSs, but four Bnd4 homologues do not have a complete DDxxD motif (e.g., Amycolatopsis arida has a DDxxV motif; Amycolatopsis taiwanensis has a GNNAA motif).

Characterization of a novel diterpene synthase and structural elucidation of the core diterpene scaffold

To confirm whether Bnd4 and the BGC that encodes it is responsible for the biosynthesis of benditerpenoic acid (1), we cloned bnd4 into E. coli and produced and purified Bnd4 for in vitro biochemical characterization (Figure S26). Incubation of Bnd4 with geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) resulted in the formation of a single non-polar product named benditerpe-2,6,15-triene (2) (Figure 4A). We also individually incubated Bnd4 with geranyl diphosphate (GPP) and farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) but only saw minor amounts of geraniol, farnesol, and a few additional unknown products (Figure S27).

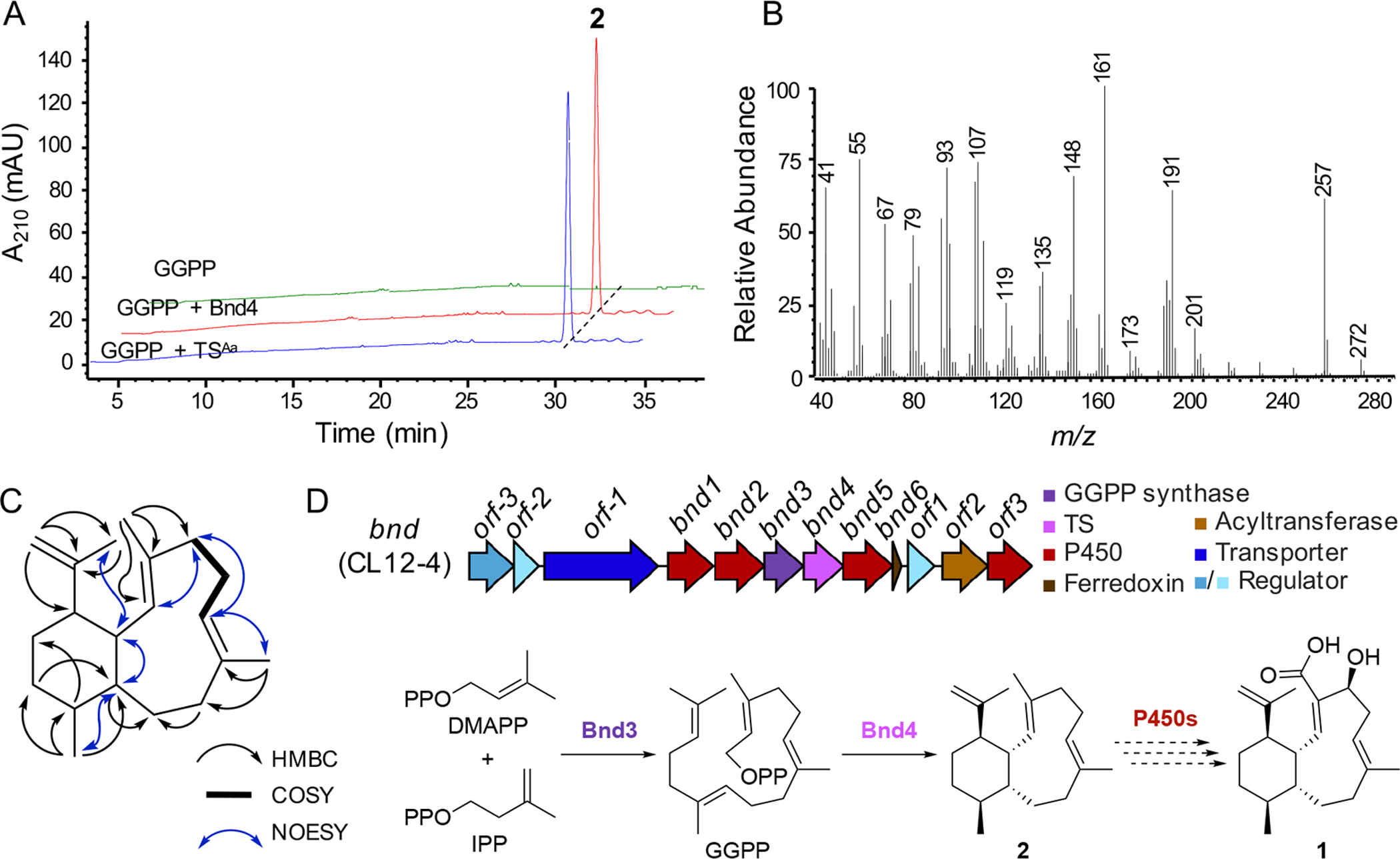

Figure 4.

Biochemical characterization of Bnd4, structural elucidation of 2, and biosynthesis of 1. (A) Bnd4 and TSAa catalyze the cyclization of GGPP into 2. Enzyme reactions, including a no enzyme control (GGPP), were analyzed by HPLC by monitoring at 210 nm. (B) GCMS spectrum of pure 2. (C) Structure of 2 and key 2D NMR correlations supporting its structural assignment. (D) Biosynthetic gene cluster (bnd) and proposed biosynthetic pathway for 2. The formation of 2, a novel 6,10-bicyclic scaffold, by a unique TS, precedes oxidative tailoring affording 1.

Inspired by previously successful diterpene production in E. coli,[22] we constructed a three-plasmid system for diterpene production. We subcloned bnd4 into pET21a yielding pJR1017 and transformed E. coli BL21 Star (DE3) harboring pJR1015 and pJBEI-2999,[23] which encode a GGPP synthase and an FPP overproduction system, respectively, with pJR1017. We also created a two-plasmid system harboring only pJR1017 and pJR1015 to test whether pJBEI-2999 enhanced the yield of benditerpe-2,6,15-triene (2). While both constructs produced 2, the three-plasmid system had a significantly higher titer (Figure S28).

A large scale (12 L) culture of the three-plasmid system in E. coli resulted in the isolation of 10.7 mg of 2. GC-MS analysis of 2 afforded an M+ peak with an m/z of 272, consistent with that of a diterpene skeleton, but the MS spectrum was unique when compared with the NIST reference database (Figure 4B, Figure S29). NMR elucidation was based on 1D and 2D NMR experiments (Figures S30–S35). Full assignment was achieved using CDCl3 as solvent at room temperature (Table S1) and supported by higher temperature experiments at 70 °C in C6D6, which reduced peak broadening due to conformational flexibility (Figure S36). Briefly, the planar structure was established by spin systems found in the six- and ten-membered rings via COSY and HMBC correlations (Figure 4C). Similar to 1, key NOESY correlations were found between CH3-18 and H-10 and CH3-18 and H-1, placing them both syn in regard to the bicyclic system; H-1 and H-10 also showed a NOESY crosspeak. No correlation between H-14 and H-1 was interpreted as anti configuration. Analogous to 1, NMR and DFT-based computations were used to assign the relative and absolute configuration of 2. JBCA and subsequent modeling of the proposed multiplet (ddd, J = 12.4, 9.0, 4.2 Hz) indicates 2 has the same 1S*,10R*,14R* relative configuration as 1. NOE correlations from H-1 to CH3-17 and CH3-18 indicate these groups are cis to H-1. The double bond geometry was derived from J-based analysis using IPAP-HMBC NMR experiments which yielded 3J(H-2,C-20) and 3J(CH3–20,C-2) coupling constants of 8.9 Hz (calculated 8.0 Hz) and 5.6 Hz (calculated for 4.8 Hz), respectively, supporting assignment of the C-2/C-3 double as E configured (Figure S37). C-6/C-7 was also assigned as E configured based on the 3J(H-6,C-19) and 2J(H-6,C-5) coupling constants of 6.4 Hz (calculated 4.5 Hz) and 4.9 Hz (calculated for 4.9 Hz), respectively. Considering the biosynthetic logic and the relative configuration of 2 is identical to that of 1, we concluded that the absolute configuration of 2 is 1S,2E,6E,10R,11S,14R. In solution, four conformers account for 98.7% of the conformational space of 2 (Figure S38). Recently, a 6,10-bicyclic intermediate with the same absolute configuration of 2 was proposed in the cyclization mechanism of catenul-14-en-6-ol synthase (CaCS), using comprehensive isotopic labeling experiments, benditerpetriene, however, is not formed by CaCS.[24] Bnd4 and CaCS only share 23% sequence identity with 52% coverage. These data, taken together, support the functional assignment of Bnd4 as a product-specific benditerpe-2,6,15-triene synthase.

Proposed biosynthesis of benditerpenoic acid (1) via benditerpe-2,6,15-triene (2)

After confirming that Bnd4 generates the same 6,10-bicyclic scaffold seen in 1, we next analyzed the genetic neighborhood of bnd4 to identify the BGC responsible for the biosynthesis of 1. bnd4 is located within a promising BGC that encodes a GGPP synthase (bnd3), three cytochromes P450 (bnd1, bnd2, and bnd5), a ferredoxin (bnd6), and a complement of regulatory proteins and a transporter (Figure 4D). In fact, bnd1–bnd6 are predicted to be encoded within a single operon. A fourth P450 (orf3) and an acyltransferase (orf2) are found downstream of the bnd cluster; however, it is unclear whether these are involved in the biosynthesis of 1. There are only two oxidative transformations, a six-electron oxidation of CH3-20 and a stereoselective hydroxylation at C-4, required to process 2 into 1. Therefore, we propose that after Bnd4 forms 2 from GGPP, which is synthesized by Bnd3, the 6,10-bicyclic carbon skeleton is sequentially oxidized by the encoded P450s. It is tempting to speculate why these neighboring genes are present, based on the fact that only one natural product was detected and isolated in our culture conditions. For example, three or four P450s are present but unlikely to be required for the two oxidative transformations, particularly given that a single P450 is capable of catalyzing the six-electron oxidation of a methyl group into a carboxylic acid.[25] Sequence analysis of the four P450s revealed that each P450 possesses the axial Cys and other commonly conserved motifs and residues found in functional P450s from Streptomyces.[26] Overall, the genes might be involved in the extended biosynthesis of a more complex natural product which we did not detect or may confer resistance to 1. Future studies are planned to elucidate the roles, if any, of these genes in the biosynthesis of 1.

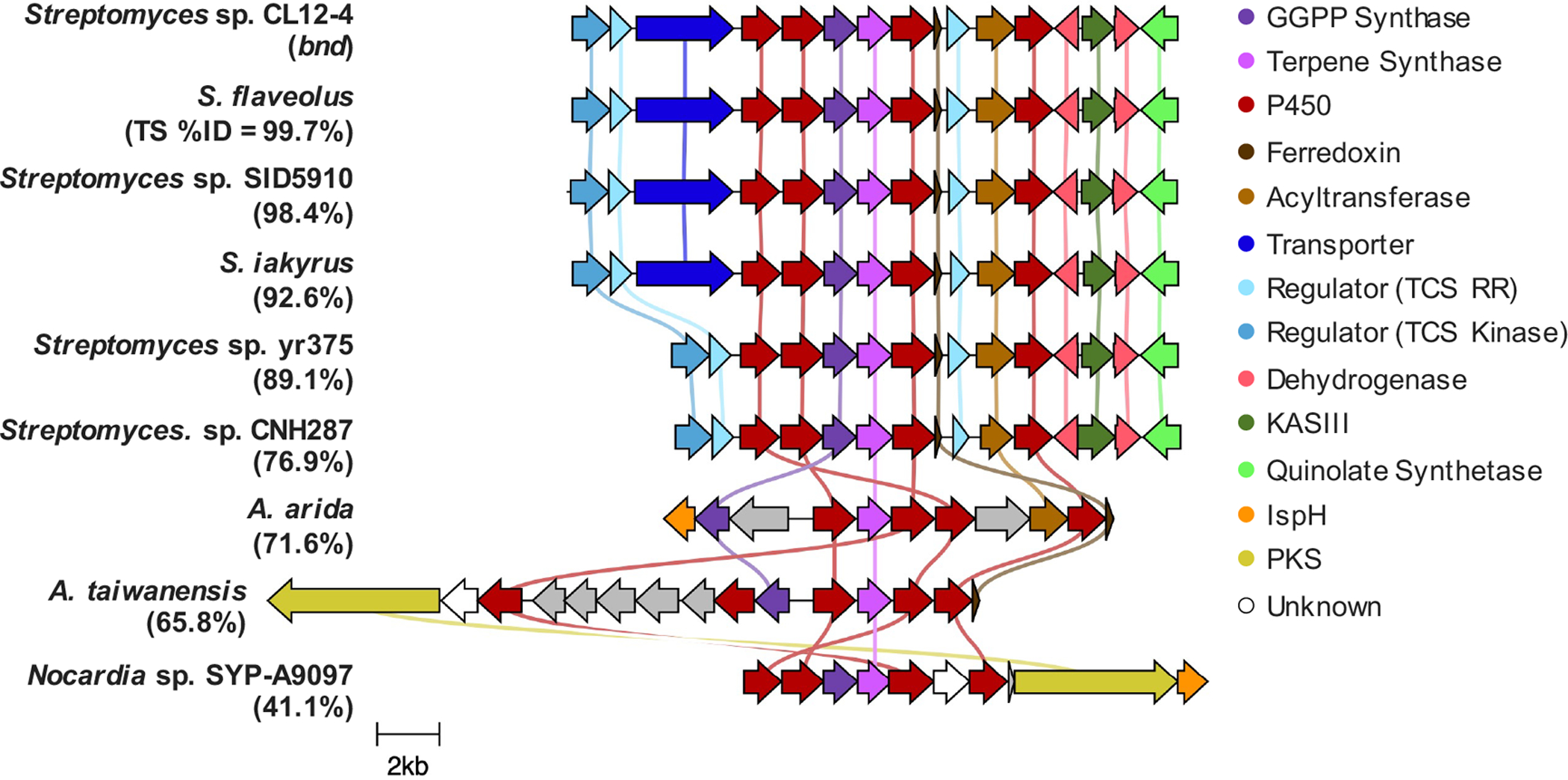

In order to evaluate whether the eight highly homologous TSs of Bnd4 are predicted to biosynthesize 1, we first annotated their genetic neighborhoods and aligned the BGCs with Clinker (Figure 5).[27] In fact, each of the BGCs encodes the core biosynthetic genes with each of the BGCs from Streptomyces identical in genetic organization, with the exception of the lack of the transporter in Streptomyces sp. CNH287 and Streptomyces sp. yr375. While the BGC from A. arida possesses the five core genes, the organization is different, includes an isoprenoid precursor gene and the downstream acyltransferase (orf2 in CL12-4) and additional P450 (orf3 in CL12-4), suggesting they may in fact be biosynthetically related, perhaps in the biosynthesis of a natural derivative of 1. Two additional BGCs from A. taiwanensis and Nocardia sp. SYP-A9097 encode similar cohorts of genes as well as type I polyketide synthases (Figure 5). Having access to A. arida, we sought to determine whether its homologous TS (71.6% identity to Bnd4), TSAa, produces 2. As with Bnd4, we heterologously produced TSAa in E. coli and confirmed that it converts GGPP into 2 in vitro (Figure 4A and S26). Therefore, while its BGC is different to that in Streptomyces sp. (CL12-4), the terpene core is identical. This may support that the 6,10-bicyclic scaffold of 2 is used to biosynthesize additional unique natural products in bacteria.

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of the bnd biosynthetic gene clusters. Genes are color-coded based upon their annotated Pfam or InterPro designations. The BGCs from the various Streptomyces spp. are almost all identical and are predicted to biosynthesize 1. The BGCs from the two Amycolatopsis spp. and Nocardia sp. SYP-A9097 encode the core genes but possess different genes and genetic organization suggesting they produce the 6,10-bicyclic eunicellane-like core but biosynthesize different natural products.

Activity

Both new terpenoids were screened for cytotoxicity in mammalian cancer cells[28] and antimicrobial activity in a panel of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria and the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans.[29] Against Gram-positive bacteria, 1 exhibits moderate activity against the spore-forming bacterium Bacillus subtilis, a laboratory surrogate for Bacillus anthracis, and the human pathogen Enterococcus faecium with MIC values of 32 and 128 μg mL−1. Moderate anti-staphylococcal activity was observed against S. aureus, methicillin-resistant S. aureus, and multi-drug resistant S. aureus with MIC values of 64, 64, and 128 μg mL−1, respectively. The unoxidized benditerpe-2,6,15-triene (2) is less active than 1 (Table 1). No cytotoxicity was observed in single dose assays for 1 or 2 against five mammalian cell lines (at 10 μM), C. albicans, and the tested Gram-negative bacteria (at 100 μM).

Table 1.

Single dose testing of 1 and 2 against selected microorganisms (100 μM), given in percent cell survival, antibiotic controls were tested at 100 μg mL−1. MIC assessment for 1 against Gram-positive pathogens (μg mL−1).

| E. faecium | S. aureus | methicillin resistant S. aureus | multidrug resistant S. aureus | B. subtilis | E. coli | P. aeruginosa | C. albicans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benditerpenoic acid (1) | 102.1 ± 1.1 | 49.7 ± 3.6 | 59.5 ± 2.5 | 50.2 ± 3.5 | 1.1 ± 0.9 | 125.4 ± 1.9 | 95.3 ± 0.4 | 125.0 ± 6.9 |

| Benditerpe-2,6,15-triene (2) | 112.5 ± 1.1 | 86.9 ± 6.0 | 95.2 ± 1.0 | 103.3 ± 1.4 | 48.4 ± 12.3 | 133.1 ± 3.5 | 97.7 ± 0.7 | 224.6 ± 3.0 |

| Kanamycin | - | 0.0 ± 0.5 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Vancomycin | 0.0 ± 0.0 | - | 0.4 ± 0.4 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 0.0 ± 0.3 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | - |

| Chloramphenicol | - | - | - | - | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 11.9 ± 4.2 | 0.0 ± 0.1 | - |

| Amphotericin B | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 0.0 ± 13.7 |

| Benditerpenoic acid (1) MIC | 128 | 64 | 64 | 128 | 32 | - | - | - |

Conclusion

In summary, we discovered the first bacterial eunicellane-type diterpenoid antibiotic from a soil-dwelling Streptomyces sp. (CL12-4). Using genome sequencing and genome mining, we identified the responsible BGC and characterized the unique TS that generates the trans-fused bicyclo[8.4.0]tetradecane scaffold of benditerpenoic acid. Both, the natural product and heterologously expressed benditerpe-2,6,15-triene core, are structurally complex with five and four stereocenters, respectively, and two double bond geometries in a fused bicyclo[8.4.0]tetradecane scaffold. Extensive spectroscopic analyses, including Mosher’s analysis, J-based coupling analysis, and computations based on sparse NMR-derived experimental restraints, independently established the absolute configurations. It is noteworthy that these novel diterpenoids are dynamic, existing in distinct ring-flipped conformers in solution, and begs the question if this ring flexibility impacts its downstream biosynthetic steps and therefore can modulate the biological activity. Benditerpenoic acid was moderately active against a panel of Gram-positive bacteria while the benditerpe-2,6,15-triene core was less active. This study, and the prevailing literature,[2b] supports that bacteria are a reservoir for novel terpene scaffolds, terpenoid natural products, and terpene synthases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by OSU (SL) and UF start-up funds (SL and JDR) and by NIH Grant R00 GM124461 (JDR) and NSF Grant 1808717 (SL). We wish to thank Elizabeth N. Kaweesa, Dr. Birte Plitzko for assisting with cell viability assays, Paige E. Mandelare for antifungal assays, Cassandra Lew for support in culture processing, and Eugene Kwan in metadynamics calculations. We wish to thank Steve Huhn (OSU) and James Rocca (UF) for excellent NMR support and Jodie Johnson for GC-MS support. We acknowledge the support of the Oregon State University’s NMR Facility funded in part by the National Institutes of Health, HEI Grant 1S10OD018518, and by the M. J. Murdock Charitable Trust grant #2014162. We acknowledge the University of Florida’s McKnight Brain Institute at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory’s Advanced Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Spectroscopy (AMRIS) Facility, which is supported by the US NSF Cooperative Agreement No. DMR-1644779 and the State of Florida. Some NMR spectra were acquired using a unique 1.5 mm High Temperature Superconducting Cryogenic Probe developed with support from the NIH (R01 EB009772). We also thank the University of Florida’s Mass Spectrometry Research and Education Center (MSREC), which is supported by the NIH S10 OD021758-01A1.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This manuscript has been accepted after peer review and appears as an Accepted Article online prior to editing, proofing, and formal publication of the final Version of Record (VoR). This work is currently citable by using the Digital Object Identifier (DOI) given below. The VoR will be published online in Early View as soon as possible and may be different to this Accepted Article as a result of editing. Readers should obtain the VoR from the journal website shown below when it is published to ensure accuracy of information. The authors are responsible for the content of this Accepted Article.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].a) Dickschat JS, Nat. Prod. Rep 2016, 33, 87–110; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lange BM, Annu. Rev. Plant Biol 2015, 66, 139–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Huang M, Lu J-J, Huang M-Q, Bao J-L, Chen X-P, Wang Y-T, Exp. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2012, 21, 1801–1818; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rudolf JD, Alsup TA, Xu B, Li Z, Nat. Prod. Rep 2021, DOI 10.1039.D0NP00066C; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Thoppil RJ, Bishayee A, World J Hepatol. 2011, 3, 228–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Walsh CT, Tang Y, Natural Product Biosynthesis (1st Ed.), The Royal Society of Chemistry, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yamada Y, Kuzuyama T, Komatsu M, Shin-Ya K, Omura S, Cane DE, Ikeda H, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2015, 112, 857–862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Gerber NN, Biotechnol. Bioeng 1967, 9, 321–327; [Google Scholar]; b) Medsker LL, Jenkins D, Thomas JF, Koch C, Environ. Sci. Technol 1969, 3, 476–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Citron CA, Gleitzmann J, Laurenzano G, Pukall R, Dickschat JS, Chembiochem 2012, 13, 202–214; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hanson JR, Nat. Prod. Rep 2017, 34, 1233–1243; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yamada Y, Cane DE, Ikeda H, in Meth. Enzymol, Vol. 515 (Ed.: Hopwood DA), Academic Press, 2012, pp. 123–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].a) Helfrich EJN, Lin G-M, Voigt CA, Clardy J, Beilstein J Org. Chem 2019, 15, 2889–2906; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yamada Y, Arima S, Nagamitsu T, Johmoto K, Uekusa H, Eguchi T, Shin-ya K, Cane DE, Ikeda H, J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2015, 68, 385–394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Hoye TR, Jeffrey CS, Shao F, Nat. Protoc 2007, 2, 2451–2458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Matsumori N, Kaneno D, Murata M, Nakamura H, Tachibana K, J. Org. Chem 1999, 64, 866–876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sauri J, Parella T, Magn. Reson. Chem 2013, 51, 509–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].a) Cleves AE, Jain AN, Comput J. Aided Mol. Des 2017, 31, 419–439; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jain AN, Cleves AE, Gao Q, Wang X, Liu Y, Sherer EC, Reibarkh MY, Comput J. Aided Mol. Des 2019, 33, 531–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rinkel J, Rabe P, Chen X, Köllner TG, Chen F, Dickschat JS, Chem. – Eur. J 2017, 23, 10501–10505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Li G, Dickschat JS, Guo YW, Nat. Prod. Rep 2020, 37, 1367–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Biradi M, Hullatti K, Pharm. Biol 2017, 55, 1375–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Chen B-W, Chao C-H, Su J-H, Tsai C-W, Wang W-H, Wen Z-H, Huang C-Y, Sung P-J, Wu Y-C, Sheu J-H, Org. Biomol. Chem 2011, 9, 834–844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].a) Sheu JH, Sung PJ, Su JH, Wang GH, Duh CY, Shen YC, Chiang MY, Chen IT, J. Nat. Prod 1999, 62, 1415–1420; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sheu J-H, Sung P-J, Cheng M-C, Liu H-Y, Fang L-S, Duh C-Y, Chiang MY, J. Nat. Prod 1998, 61, 602–608; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Sung P-J, Su J-H, Wang G-H, Lin S-F, Duh C-Y, Sheu J-H, J. Nat. Prod 1999, 62, 457–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pech-Puch D, Joseph-Nathan P, Burgueño-Tapia E, González-Salas C, Martínez-Matamoros D, Pereira DM, Pereira RB, Jiménez C, Rodríguez J, Sci. Rep 2021, 11, 496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Blin K, Shaw S, Steinke K, Villebro R, Ziemert N, Lee SY, Medema MH, Weber T, Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W81–W87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Johnson M, Zaretskaya I, Raytselis Y, Merezhuk Y, McGinnis S, Madden TL, Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W5–W9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Zallot R, Oberg N, Gerlt JA, Biochemistry 2019, 58, 4169–4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Christianson DW, Chem. Rev 2017, 117, 11570–11648; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Driller R, Janke S, Fuchs M, Warner E, Mhashal AR, Major DT, Christmann M, Brück T, Loll B, Nat. Commun 2018, 9, 3971; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Driller R, Garbe D, Mehlmer N, Fuchs M, Raz K, Major DT, Bruck T, Loll B, Beilstein J Org. Chem 2019, 15, 2355–2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].a) Cyr A, Wilderman PR, Determan M, Peters RJ, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2007, 129, 6684–6685; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Rudolf JD, Dong L-B, Manoogian K, Shen B, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 16711–16721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Peralta-Yahya PP, Ouellet M, Chan R, Mukhopadhyay A, Keasling JD, Lee TS, Nat. Commun 2011, 2, 483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Li G, Guo Y-W, Dickschat JS, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2021, 60, 1488–1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].a) Nett RS, Montanares M, Marcassa A, Lu X, Nagel R, Charles TC, Hedden P, Rojas MC, Peters RJ, Nat. Chem. Biol 2017, 13, 69–74; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang Q, Li H, Li S, Zhu Y, Zhang G, Zhang H, Zhang W, Shi R, Zhang C, Org. Lett 2012, 14, 6142–6145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Rudolf JD, Chang C-Y, Ma M, Shen B, Nat. Prod. Rep 2017, 34, 1141–1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Gilchrist CLM, Chooi Y-H, Bioinformatics 2021, DOI 10.1093/bioinformatics/btab007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].a) Kmail A, Lyoussi B, Zaid H, Saad B, Pharmacogn. Commun 2015, 5, 165–172; [Google Scholar]; b) Mosmann T, J. Immunol. Meth 1983, 65, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].a) CLSI, Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically. 11th Ed., Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: 950 West Valley Road, Suite 2500, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087 USA, 2018; [Google Scholar]; b) CLSI, Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing M100. 30th Ed., Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: 950 West Valley Road, Suite 2500, Wayne, Pennsylvania 19087 USA, 2020; [Google Scholar]; c) Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock RE, Nat. Protoc 2008, 3, 163–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.